Abstract

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is the most common leukemia in the Western hemisphere, but its pathogenesis is still poorly understood. Constitutive tyrosine phosphorylation (p) of signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) 3 occurs in several solid tumors and hematologic malignancies. In CLL, however, STAT3 is constitutively phosphorylated on serine 727, not tyrosine 705, residues. Because the biologic significance of serine pSTAT3 in CLL is not known, we studied peripheral blood cells of 106 patients with CLL and found that, although tyrosine pSTAT3 was inducible, serine pSTAT3 was constitutive in all patients studied, regardless of blood count, disease stage, or treatment status. In addition, we demonstrated that constitutive serine pSTAT3 translocates to the nucleus by the karyopherin-β nucleocytoplasmic system and binds DNA. Dephosphorylation of inducible tyrosine pSTAT3 did not affect STAT3-DNA binding, suggesting that constitutive serine pSTAT3 binds DNA. Furthermore, infection of CLL cells with lentiviral STAT3-small hairpin RNA reduced the expression of several STAT3-regulated survival and proliferation genes and induced apoptosis, suggesting that constitutive serine pSTAT3 initiates transcription in CLL cells. Taken together, our data suggest that constitutive phosphorylation of STAT3 on serine 727 residues is a hallmark of CLL and that STAT3 be considered a therapeutic target in this disease.

Introduction

B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is the most common adult leukemia in the Western hemisphere.1 CLL is characterized by a dynamic imbalance between the proliferation and apoptosis of leukemia cells and by the accumulation of neoplastic B lymphocytes coexpressing CD5 and CD19 antigens.2-4 Several chromosomal abnormalities, such as 11q−, 13q−, 17p−, and trisomy 12,1 and molecular aberrations, including loss or down-regulation of micro-RNA 15a and 16-15,6 and overexpression of antiapoptotic genes,7 have been identified in CLL in recent years. Nevertheless, the pathogenesis of CLL is still poorly understood.

Members of the signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) family play a pivotal role in organ development and cellular proliferation and survival. Under physiologic conditions, STATs are phosphorylated on tyrosine residues by receptor and nonreceptor tyrosine kinases. Phosphorylated (p) STATs form dimers, translocate to the nucleus using the karyopherin-β nucleocytoplasmic transport system, bind DNA, and activate transcription.8-10 STAT3 is the only STAT family member whose deletion results in embryonic lethality.11 Remarkably, STAT3 activation is required for the survival and proliferation of a number of tumor cells,12-15 and constitutive STAT3 phosphorylation on tyrosine residues has been found in several solid tumors and hematologic malignancies.16-19 In addition to tyrosine phosphorylation, STATs 1, 3, 4, 5A, and 5B are occasionally phosphorylated on serine residues, located on their carboxyl-terminal trans-activation domains.20 Although tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT3 is accompanied by serine phosphorylation in a variety of cells, the biologic role of serine pSTAT3 has been controversial. Some studies suggest that serine phosphorylation enhances transcriptional activity,21,22 whereas other reports demonstrate that serine phosphorylation induces inhibitory activity.23,24

A decade ago, Frank et al25 reported that, unlike in other hematologic malignancies, in CLL STAT3 is constitutively phosphorylated exclusively on serine residues. This observation prompted us to investigate the role of STAT3 in CLL. We verified that STAT3 is constitutively phosphorylated on serine 727, but not on tyrosine 705, residues in CLL cells and demonstrated that serine pSTAT3 translocates to the nucleus, binds to DNA, and activates the transcription of STAT3-regulated genes.

Methods

Cell lines

The human renal epithelial carcinoma 293T cells were grown in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM; Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS; HyClone), and the human alveolar basal epithelial cell carcinoma A549 cells were grown in tissue culture medium M-199 (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% FCS. The cells were harvested at the peak of their growth and used in the experiments described in “Western blot analysis.”

Cell fractionation

Peripheral blood (PB) cells were obtained from healthy donors and from patients with CLL who were treated at the University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center Leukemia Clinic during the years 2006 to 2008, after obtaining Institutional Review Board-approved informed consent. The clinical characteristics of the patients whose PB samples were studied in detail are presented in Table 1. To isolate low-density cells, PB cells were fractionated using Ficoll Hypaque 1077 (Sigma-Aldrich). Fractionated cells were used immediately or frozen for additional studies. More than 90% of the CLL PB cells were CD19+/CD5+ lymphocytes. To isolate CD19+ cells, CLL PB low-density cells were fractionated using micro-immunomagnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotec) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. Flow cytometry analysis confirmed that more than 95% of the fractionated cells were CD19+. Similarly, normal B cells (CD19+/CD20+) were isolated from healthy volunteers' PB low-density cells by positive selection. After incubation of PB low-density cells with mouse anti–human CD19 and mouse anti–human CD20 antibodies (Invitrogen), Biomag goat anti–mouse magnetic beads (QIAGEN) were added and CD19+/CD20+ cells were separated by attaching the tube with the suspended cells to a magnet and thoroughly washing the nonattached cells with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Invitrogen). Fractionated CLL cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS and incubated with either leptomycin B (Calbiochem) or recombinant human interleukin-6 (IL-6; BioSource International).

Western blot analysis

Western immunoblotting was performed as previously described.26 Briefly, cell pellets were lysed in ice-cold radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer containing 1mM sodium orthovanadate, 10mM sodium fluoride, 100μM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 5mM β-glycerol phosphate, 1 μg/mL aprotinin, 0.4mM benzamidine, 1 μg/mL antipain, 1mM phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride, 1 μg/mL leupeptin, and 1 μg/mL trypsin inhibitor soybean. The lysed cell pellets were incubated on ice for 5 minutes and vortexed for 1 minute. Then, cell debris was eliminated by centrifugation at 14 000 rpm for 15 minutes, supernatants were harvested, and the protein concentration was determined using the Micro BCA protein assay reagent kit (Thermo Scientific, Pierce Chemical). Supernatant proteins were denatured by boiling for 5 minutes in sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. After transfer, equal loading was verified by Ponceau staining. The membranes were blocked with 5% skim milk in Tris-buffered saline and incubated with the following antibodies: monoclonal mouse anti–human STAT3 (BD Biosciences); monoclonal mouse anti–human phosphotyrosine STAT3, polyclonal rabbit anti–human nucleus transporter chromosome region maintenance 1 (CRM1), and polyclonal rabbit anti–human Kpnβ1 (importin-β1; Calbiochem); polyclonal rabbit anti–human phosphoserine STAT3 (Cell Signaling Technology); monoclonal mouse anti–human β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich); and monoclonal mouse anti–human importin-α6 (Abcam), monoclonal rat anti–human importin-α1, monoclonal rat anti–human importin-α3, and monoclonal anti–human importin-α5 and 7 (Medical and Biological Laboratories). After binding with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies, blots were visualized with an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (GE Healthcare), and densitometry analysis was performed using Epson Expression 1680 scanner (Epson America). Densitometry values were normalized by dividing the numerical value of each sample signal by the numerical value of the signal from the corresponding loading control. In some experiments, the membranes were stripped by incubation with stripping buffer (62.5mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.7, 2% SDS, 100mM β-mercaptoethanol) for 30 minutes at 50°C, washed, and reprobed with an antibody.

Isolation of nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts

Nondenatured nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts were prepared using the NE-PER extraction kit (Thermo Scientific, Pierce Chemical). To confirm that pure extracts were obtained, nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions were separated by SDS-PAGE, and the presence of the nuclear protein lamin B or the cytoplasmic S6 ribosomal protein was demonstrated by Western blot analysis using monoclonal mouse anti–human lamin B and monoclonal mouse anti–human S6 ribosomal protein (Calbiochem).

Immunoprecipitation

Whole-cell lysates, cytoplasmic or nuclear fractions, were incubated with 4 μg of polyclonal rabbit anti–human STAT3 antibodies (Upstate Cell Signaling Solutions), polyclonal rabbit anti–human importin-β1, or polyclonal rabbit anti–human CRM1 (Calbiochem) for 16 hours at 4°C. Protein A agarose beads (Upstate Cell Signaling Solutions) were added for 2 hours at 4°C. As a negative control, whole-cell lysates, cytoplasmic or nuclear fractions, were incubated with either rabbit serum and protein A agarose beads or protein A agarose beads only. After 3 washes with radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer, the beads were resuspended with SDS sample buffer, boiled for 5 minutes, and removed by centrifugation, and the supernatant proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE as described in “Western blot analysis.”

Confocal microscopy

CLL low-density cells were cytospun on poly-L-lysine–coated slides and fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde for 15 minutes at room temperature on a shaker. The slides were then washed 3 times with PBS, incubated with 1% Triton X-100 for 5 minutes at room temperature, and washed 3 times with PBS again before blocking with goat serum for 1 hour. After blocking, the slides were washed in PBS and incubated overnight with Alexa Fluor 488 mouse anti–human phosphoserine (serine 727)-STAT3 antibodies (BD Biosciences). The slides were then extensively washed in PBS and incubated with nuclear stain TOPRO3 (Invitrogen). In other experiments, cells were incubated with mouse anti-S6 ribosomal protein (Calbiochem) overnight, extensively washed in PBS, and then incubated with phycoerythrin rabbit anti–mouse antibody (BD Biosciences) for 1 hour. The slides were then mounted with Vectashield hard set (Vector Laboratories). The slides were viewed using an Olympus FluoView 500 Laser Scanning Confocal Microscope (Olympus America), and images were analyzed using FluoView software (Olympus).

EMSA

A total of 2 μg of nuclear protein was incubated with biotin-labeled STAT3 binding-site DNA probe (Gel-Shift Kit; Panomics) in binding buffer for 30 minutes on ice. After incubation, the samples were separated on a 5% polyacrylamide gel in Tris-borate ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, transferred onto a nylon membrane, and fixed on the membrane by ultraviolet cross-linking. The biotin-labeled probe was detected with streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase (Gel-Shift Kit; Panomics). As a negative control, we used a probe lacking nuclear extracts. The competition control consisted of excess unlabeled cold probe added to the nuclear extract and the biotin-labeled probe. For supershift analysis, 1 μg monoclonal mouse anti–human STAT3 (BD Biosciences) was incubated with nuclear extracts for 30 minutes on ice before the addition of the biotin-labeled DNA probe. The isotypic control consisted of mouse immunoglobulin G1 (BD Biosciences).

Pull-down of STAT3 with biotin-labeled DNA probe

A modification of a previously described method was used.8 A total of 40 μg of nuclear protein was incubated with 15 pmol of the biotin-labeled STAT3-binding DNA probes 5′-TTCCGGGAA-3′ (ICAM-pIRE) and 5′-TTCCCGTAA-3′ (hSIE67; Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 minutes at 4°C in 200 μL of DNA binding buffer (20mM N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid, pH 7.9, 30mM KCl, 2mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 2mM ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid, 25% glycerol). A total of 30 μL of 50% suspension of agarose-conjugated streptavidin beads (Thermo Scientific) was added, and the tubes were incubated for 1 hour at 4°C. As negative controls, we used nuclear extracts incubated with 15 pmol of unlabeled STAT3 binding-site DNA probes (Sigma-Aldrich) and agarose-conjugated streptavidin beads and nuclear extracts incubated with agarose-conjugated streptavidin beads only. After 4 washes with DNA-binding buffer, the agarose beads were resuspended with SDS sample buffer and boiled for 5 minutes. After centrifugation, the supernatant was separated by SDS electrophoresis, and the membrane was developed by mouse anti–human STAT3 (BD Biosciences) or rabbit anti–human phosphoserine STAT3 (Cell Signaling Technology) antibodies, as described in “Western blot analysis.”

ChIP

The enzymatic ChIP Kit (Cell Signaling Technology) was used. Briefly, cells were cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde for 10 minutes at room temperature, a glycine solution was added to stop the reaction, and the cells were washed with ice-cold PBS. Then, the cells were pooled, pelleted, and incubated on ice for 10 minutes in lysis buffer supplemented with 100mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, dithiothreitol (DTT), and a protease cocktail inhibitor mix. Nuclei were pelleted and resuspended in buffer supplemented with DTT, digested by micrococcal nuclease, and homogenized on ice. After sonication (35 pulses, 20 seconds/pulse at 25%–30% power) and centrifugation, 12 mg of sheared chromatin was incubated with anti-STAT3 or rabbit serum (negative control) overnight at 4°C. Then, magnetic-coupled protein G beads were added and the chromatin was incubated for 2 hours in rotation. An aliquot of chromatin that was not incubated with an antibody was used as the input control sample. Antibody-bound protein/DNA complexes were washed, eluted, treated with proteinase digest proteins, and subjected to polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analyses. The primers to amplify the human STAT3 promoter were as follows: forward, 5-CCG AAC GAG CTG GCC TTT CAT-3; and reverse, 5-GGA TTG GCT GAA GGG GCT GTA-3, which generated a 86-bp product; to amplify the Waf/p21 promoter: forward, 5-TTG TGC CAC TGC TGA CTT TGT C-3; and reverse, 5-CCT CAC ATC CTC CTT CTT CAG GCT-3, which generated a 303-bp product; and to amplify the c-Myc promoter: forward, 5-TGA GTA TAA AAG CCG GTT TTC-3; and reverse, 5-AGT AAT TCC AGC GAG AGG CAG-3, which generated a 63-bp product. The human RPL30 gene primers were provided by Cell Signaling Technologies. PCR products were resolved on 1.8% agarose gels containing ethidium bromide.

Dephosphorylation of IL-6–induced tyrosine pSTAT3

To dephosphorylate tyrosine pSTAT3, we incubated nuclear extracts of IL-6–stimulated and –unstimulated cells with T-cell protein tyrosine phosphatase (TC-PTP), a known tyrosine phosphatase of STAT3.27 Briefly, 100 μg of nuclear protein, extracted from untreated or IL-6–treated CLL cells, was incubated, with or without 2.5 μg TC-PTP (synthesized by S.S. and X.C.), in buffer (250nM N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid, pH 7.2, 50mM NaCl, 5mM DTT, 2.5mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) for 30 minutes at 30°C in a final volume of 50 μL. After the enzymatic reaction was completed, Western blot analysis was performed to detect STAT3 phosphorylation, and electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) was used to determine STAT3-DNA binding, as described in “EMSA.”

Generation of GFP-lentivirus STAT3 shRNA and infection of CLL cells

The 293T cells were cotransfected with green fluorescence protein (GFP)–lentivirus STAT3 small hairpin RNA (shRNA) or GFP-lentivirus empty vector and the packaging vectors pCMVdeltaR8.2 and pMDG (generously provided by Dr G. Inghirami, Torino, Italy) using the superfect transfection reagent (QIAGEN). The 293T cell culture medium was changed after 16 hours and collected after 48 hours. The culture medium was filtered through a 45-μm syringe filter to remove floating cells, the lentivirus was then concentrated by filtration through an Amicon ultracentrifugal filter device (Millipore), and the concentrated supernatant was used to infect CLL cells. CLL cells (5 × 106/mL) were incubated in 6-well plates (BD Biosciences) in 2 mL DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS and transfected with 100 μL of viral supernatant. Polybrene (10 ng/mL) was added to the viral supernatant at a ratio of 1:1000 (vol/vol). Infection efficiency was measured after 48 to 72 hours and was found to range between 40% and 70% (calculated on the basis of the ratio of propidium iodide [PI]−/GFP+ cells). These experiments were conducted using the FACSCalibur flow cytometer. Data analysis was performed using its software programs (BD Biosciences). A shift from the control curve was calculated as percentage shift beyond control using the ModFit LT (Version 2.0; Verity Software House) program.

RNA purification and RT-PCR

RNA was isolated using the RNeasy purification procedure (QIAGEN). RNA quality and concentration were analyzed with a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (ND-1000; NanoDrop Technologies). A total of 10 μg of total RNA was used in 1-step real-time (RT)–PCR (Applied Biosystems) with the sequence detection system ABI Prism 7700 (Applied Biosystems) using TaqMan gene expression assay for STAT1, STAT3, STAT5A, Bcl2, Bcl-XL, c-Myc, Pim1, p21 (Waf1), and S18, according to the manufacturer's instructions. Samples were run in triplicate, and relative quantification was performed by comparing the values obtained at the fractional cycle number at which the amount of amplified target reaches a fixed threshold (threshold cycle).

Apoptosis assay

The rate of cellular apoptosis was analyzed using double staining with a Cy5-conjugated annexin V kit and PI (BD Biosciences), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, 1 × 106 cells were washed once with PBS and resuspended in 200 μL binding buffer with 0.5 μg/mL annexin V-Cy5 and 2 μg/mL PI. After incubation for 10 minutes in the dark at room temperature, the samples were analyzed on a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). Cell viability was calculated as the percentage of annexin V+ cells, and statistical analysis was performed using the ModFit program.

Results

STAT3 is constitutively phosphorylated on serine 727 residues in CLL cells

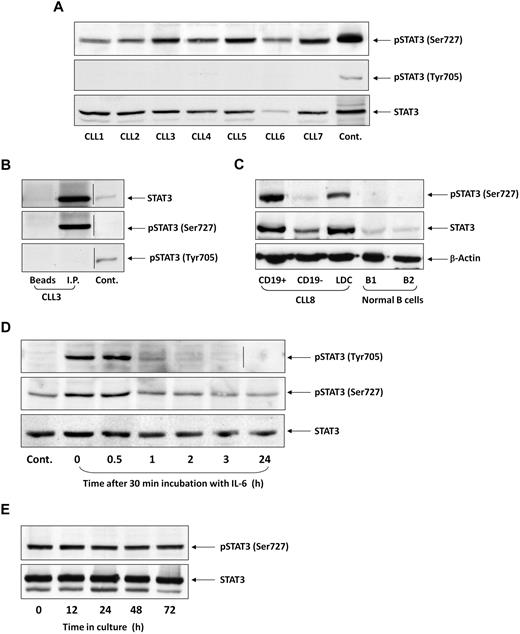

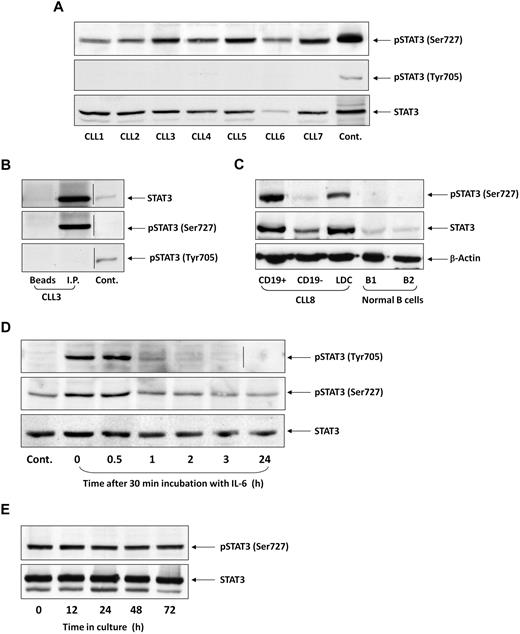

To test whether STAT3 is constitutively phosphorylated on serine residues in CLL cells, as previously reported,25 we performed Western immunoblotting of PB cells from 106 patients with CLL. We found that in all patients, regardless of PB count, disease stage, or treatment status, STAT3 was constitutively phosphorylated on serine 727, but not on tyrosine 705, residues. Figure 1A depicts a representative experiment performed using PB low-density cells from 7 patients with CLL. In all samples, serine, but not tyrosine, pSTAT3 was readily detected. Furthermore, as shown in Figure 1B, serine, but not tyrosine, pSTAT3 was detected in the immunoprecipitated STAT3 protein. Neither STAT3 nor serine pSTAT3 was detected when immunoprecipitation was performed with protein A-agarose beads only (Figure 1B, first lane, “Beads”) or with rabbit serum and protein A-agarose beads (data not shown). To confirm that serine pSTAT3 is phosphorylated in the leukemic (CLL) cellular population, we fractionated CLL blood low-density cells using immunomagnetic beads. As shown in Figure 1C, we detected serine pSTAT3 in CLL (CD19+) cells, but not in nonleukemic (CD19−) cells, and high levels of STAT3 in the CD19+ fraction. Furthermore, we did not detect serine pSTAT3 in normal PB B lymphocytes obtained from 2 healthy donors (Figure 1C). Taken together, these data suggest that STAT3 is constitutively phosphorylated on serine 727 residues in CLL cells.

STAT3 is constitutively phosphorylated on serine 727 residues in CLL cells. (A) Cell lysates of patients with CLL (CLL 1-7) and of A549 cells (control) were analyzed by Western immunoblotting using antiserine pSTAT3, antityrosine pSTAT3, or anti-STAT3 antibodies. (B) Cell lysates of CLL patient 3 were incubated with rabbit anti–human STAT3 antibodies for immunoprecipitation (I.P.) with protein A-agarose beads. Incubation of cell lysates with beads only was used as a negative control (beads). The immunoprecipitate was analyzed by Western immunoblotting using antiserine pSTAT3, antityrosine pSTAT3, or anti-pSTAT3 antibodies. 3T3 cells were used as a positive control (Cont.). (C) PB cells of CLL patient 8 were fractioned using immunomagnetic beads. CD19+ and CD19− cells were collected. Normal PB CD19+/CD20+ B cells were purified by immunomagnetic beads. Expression of serine pSTAT3 in CLL low-density cells (LDC), CD19+, and CD19− cells and normal donor B cells (B1 and B2) was analyzed by Western immunoblotting using antiserine pSTAT3, anti-STAT3, or anti–β-actin (loading control) antibodies. (D) CLL cells (CLL 9) were stimulated with IL-6 (50 ng/mL, 30 minutes) or left untreated. The cells were harvested at different time points after IL-6 stimulation. Cell lysates were analyzed by Western immunoblotting using antityrosine pSTAT3, antiserine pSTAT3, or anti-STAT3 antibodies. (E) CLL cells (CLL 10) were cultured in medium for 12 to 72 hours, the cells were harvested, and cell lysates were analyzed by Western immunoblotting using antiserine pSTAT3 or anti-STAT3 antibodies. Vertical lines indicate realignment of the same gel's image.

STAT3 is constitutively phosphorylated on serine 727 residues in CLL cells. (A) Cell lysates of patients with CLL (CLL 1-7) and of A549 cells (control) were analyzed by Western immunoblotting using antiserine pSTAT3, antityrosine pSTAT3, or anti-STAT3 antibodies. (B) Cell lysates of CLL patient 3 were incubated with rabbit anti–human STAT3 antibodies for immunoprecipitation (I.P.) with protein A-agarose beads. Incubation of cell lysates with beads only was used as a negative control (beads). The immunoprecipitate was analyzed by Western immunoblotting using antiserine pSTAT3, antityrosine pSTAT3, or anti-pSTAT3 antibodies. 3T3 cells were used as a positive control (Cont.). (C) PB cells of CLL patient 8 were fractioned using immunomagnetic beads. CD19+ and CD19− cells were collected. Normal PB CD19+/CD20+ B cells were purified by immunomagnetic beads. Expression of serine pSTAT3 in CLL low-density cells (LDC), CD19+, and CD19− cells and normal donor B cells (B1 and B2) was analyzed by Western immunoblotting using antiserine pSTAT3, anti-STAT3, or anti–β-actin (loading control) antibodies. (D) CLL cells (CLL 9) were stimulated with IL-6 (50 ng/mL, 30 minutes) or left untreated. The cells were harvested at different time points after IL-6 stimulation. Cell lysates were analyzed by Western immunoblotting using antityrosine pSTAT3, antiserine pSTAT3, or anti-STAT3 antibodies. (E) CLL cells (CLL 10) were cultured in medium for 12 to 72 hours, the cells were harvested, and cell lysates were analyzed by Western immunoblotting using antiserine pSTAT3 or anti-STAT3 antibodies. Vertical lines indicate realignment of the same gel's image.

Inducible tyrosine pSTAT3 is transient, whereas constitutive serine pSTAT3 is permanent in CLL cells

CLL cells are exposed in vivo to various endogenous factors capable of inducing tyrosine phosphorylation.28-30 However, serine, rather than tyrosine, pSTAT3 has been detected in untreated CLL cells. We hypothesized that, if tyrosine pSTAT3 is induced in CLL cells, it is short-lived. To test this hypothesis, we incubated CLL cells with 50 ng/mL IL-6 for 30 minutes, replaced the culture medium with DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS, harvested the cells at different time points, and performed Western blot analysis. As shown in Figure 1D, IL-6 induced transient tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT3. One hour after stimulation, the levels of tyrosine pSTAT3 spontaneously declined. In sharp contrast, serine pSTAT3 levels in untreated cells remained stable, slightly increased with IL-6 treatment, and did not change significantly for 24 hours after stimulation. To confirm that constitutive serine pSTAT3 levels do not decline, we cultured low-density CLL cells in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS for 12 to 72 hours and performed Western immunoblotting to detect serine pSTAT3. As shown in Figure 1E, the levels of serine pSTAT3 remained unchanged for 72 hours, despite the unfavorable tissue culture conditions. Thus, whereas inducible STAT3 tyrosine phosphorylation is transient, constitutive serine pSTAT3 is permanent and probably induced by an intrinsic mechanism in CLL cells.

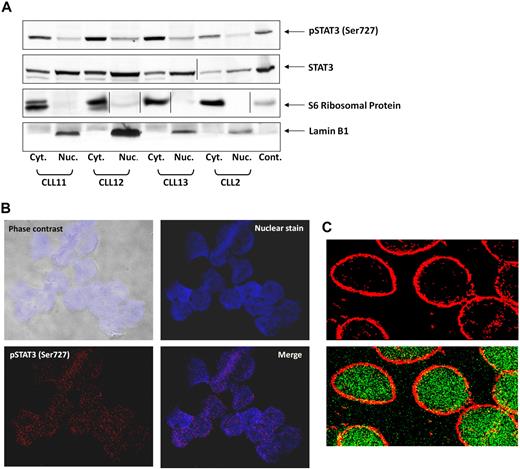

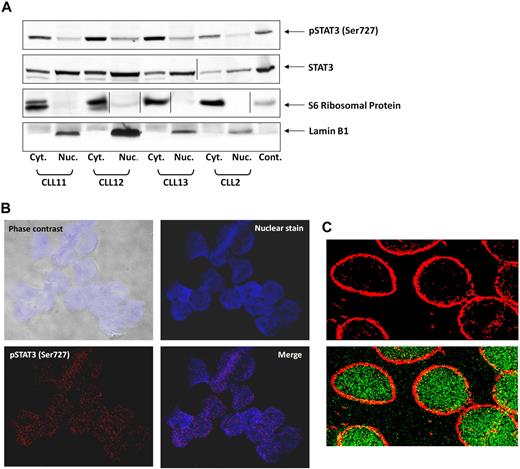

Serine pSTAT3 translocates to the nucleus

On phosphorylation on tyrosine residues, STAT3 translocates to the nucleus.31 To determine whether serine pSTAT3 also translocates to the nucleus, we extracted cytoplasmic and nuclear protein from CLL PB low-density cells and detected STAT3 and serine pSTAT3 with their corresponding antibodies. As shown in Figure 2A, we detected serine pSTAT3 in both the cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions of CLL cells. Lamin B1 served as a positive control for the nuclear fraction, and S6 ribosomal protein was a positive control for the cytoplasmic fraction. The ratio between serine pSTAT3 and total STAT3 appears to be higher in the cytoplasm than in the nucleus, suggesting that a higher level of serine pSTAT3 is present in the cytoplasm, and unphosphorylated and dephosphorylated STAT3 is present in the nucleus. To further verify that serine pSTAT3 is located in the nucleus of CLL cells, we used confocal microscopy. As shown in Figure 2B, serine pSTAT3 was detected in the nucleus of CLL cells. In another set of experiments, we stained the cytoplasm with antiribosomal protein S6 antibodies and serine pSTAT3 with antiphosphoserine-STAT3 Alexa Fluor 488 mouse anti–human antibodies. As shown Figure 2C, serine pSTAT3 was detected in both the nucleus (green) and the cytoplasm (yellow), and the nuclear-cytoplasmic distribution of serine pSTAT3 was different from that detected by Western immunoblotting (Figure 2A) in which all lanes were loaded with the same amount of protein because of the low cytoplasm/nucleus ratio of CLL cells.

Serine pSTAT3 translocates to the nucleus. (A) Cytoplasmic (Cyt.) and nuclear (Nuc.) fractions were extracted from CLL cells of patients 2, 11, 12, and 13, as described in “Isolation of nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts,” and analyzed by Western immunoblotting using antiserine pSTAT3 and anti-STAT3 antibodies. Adequate fractionation of cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts was confirmed using anti-S6 ribosomal protein and antilamin B1 antibodies. (B) Confocal microscopic images of freshly isolated CLL cells (CLL 14 and 15) that were cytospun and fixed on glass slides, as described in “Confocal microscopy.” As shown (original magnification × 400), the slides were stained with Alexa Fluor 488–mouse antiphosphoserine (serine 727)-STAT3 antibodies (red dots; bottom left corner) and the nuclear stain TOPRO3 (blue; top right corner). Serine pSTAT3 was detected in the nucleus of CLL cells (red dots overlapping blue; bottom right corner). (C) Using a different approach, the slides were stained with antiphosphoserine (serine 727)-STAT3 Alexa Fluor 488–mouse antibodies (green dots) and ribosomal protein S6, followed by phycoerythrin-conjugated rabbit anti–mouse antibodies (red dots). Serine pSTAT3 was detected in the nucleus (green dots) and the cytoplasm (yellow dots represent colocalization of ribosomal protein S6 and serine pSTAT3; X-1000). Vertical lines indicate realignment of the same gel's image. Images were acquired using an Olympus Flowview FV500/X81 system using Flowview software and a 60× oil immersion lens, and cropped and revised using Microsoft Office PowerPoint 2003.

Serine pSTAT3 translocates to the nucleus. (A) Cytoplasmic (Cyt.) and nuclear (Nuc.) fractions were extracted from CLL cells of patients 2, 11, 12, and 13, as described in “Isolation of nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts,” and analyzed by Western immunoblotting using antiserine pSTAT3 and anti-STAT3 antibodies. Adequate fractionation of cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts was confirmed using anti-S6 ribosomal protein and antilamin B1 antibodies. (B) Confocal microscopic images of freshly isolated CLL cells (CLL 14 and 15) that were cytospun and fixed on glass slides, as described in “Confocal microscopy.” As shown (original magnification × 400), the slides were stained with Alexa Fluor 488–mouse antiphosphoserine (serine 727)-STAT3 antibodies (red dots; bottom left corner) and the nuclear stain TOPRO3 (blue; top right corner). Serine pSTAT3 was detected in the nucleus of CLL cells (red dots overlapping blue; bottom right corner). (C) Using a different approach, the slides were stained with antiphosphoserine (serine 727)-STAT3 Alexa Fluor 488–mouse antibodies (green dots) and ribosomal protein S6, followed by phycoerythrin-conjugated rabbit anti–mouse antibodies (red dots). Serine pSTAT3 was detected in the nucleus (green dots) and the cytoplasm (yellow dots represent colocalization of ribosomal protein S6 and serine pSTAT3; X-1000). Vertical lines indicate realignment of the same gel's image. Images were acquired using an Olympus Flowview FV500/X81 system using Flowview software and a 60× oil immersion lens, and cropped and revised using Microsoft Office PowerPoint 2003.

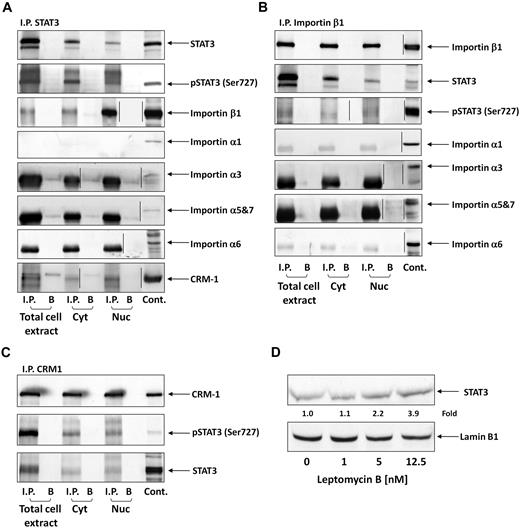

The nucleocytoplasmic trafficking of serine pSTAT3 is mediated by the karyopherin-β transport system and CRM1

STATs translocate to the nucleus using the karyopherin-β transport system. Importin-α3 or -α6 binds to the nuclear localization signal in STAT3, the N terminus of importin-α is directly recognized by importin-β1, and the complex (containing STAT3, importin-α, and importin-β1) travels through the nuclear pore complexes.32,33 Because serine pSTAT3 translocates to the nucleus in CLL cells, we wondered whether the nuclear-cytoplasmic transport system used by serine pSTAT3 is identical to the transport system used by tyrosine pSTAT3 in other cellular systems. As shown in Figure 3A, we found that STAT3 coimmunoprecipitated with importin-β1 in cytoplasmic, nuclear, and whole CLL cell extracts. However, we did not determine which α-importin binds both serine pSTAT3 and importin-β1 because none of the investigated α-importins (importin-α1, -α3, -α5, -α6, and -α7) coimmunoprecipitated with STAT3. Similar results were obtained when importin-β1 was immunoprecipitated (Figure 3B). STAT3 and serine pSTAT3 were coimmunoprecipitated; however, no coimmunoprecipitation was detected between STAT3 or serine pSTAT3 and importin-α1, -α3, -α5, -α6, or -α7. Next, we explored the nuclear export mechanism of STAT3. Again, we obtained whole-cell, nuclear, and cytoplasmic proteins and immunoprecipitated CRM1 with anti-CRM1 antibodies. As demonstrated in Figure 3C, both STAT3 and serine pSTAT3 coimmunoprecipitated with CRM1. A complementary experiment showing that CRM1 coimmunoprecipitated with STAT3 (Figure 3A) confirmed these results. To further delineate the role of CRM1 in the STAT3 nuclear export system, we incubated CLL cells with increasing concentrations of the CRM1 inhibitor leptomycin B and assessed STAT3 protein levels in nuclear extracts using Western immunoblotting. We found that leptomycin B increased the accumulation of STAT3 in the nucleus in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 3D), further confirming the role of CRM1 in exporting STAT3 from the nucleus to the cytoplasm. Taken together, these data suggest that the cytoplasmic-nuclear transport of STAT3 in CLL cells is mediated by importin-β1 and CRM1.

Serine pSTAT3 binds to the nucleocytoplasmic transport proteins importin-β1 and CRM1. Total cell, cytoplasmic (Cyt), and nuclear (Nuc) extracts were obtained from CLL cells (CLL 16 and 17), as described in “Isolation of nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts.” Whole-cell extracts, Cyt, and Nuc fractions were immunoprecipitated (I.P.) with anti-STAT3 (A), -importin-β1 (B), and -CRM1 (C) antibodies using protein A–agarose beads. Incubation with beads only (B) was used as a negative control. The immune complex was separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western immunoblotting using the indicated antibodies. Expression of STAT3, serine pSTAT3, importin-β1, importin-α1, -α3, -α6, -α5 and 7, and CRM1 in total cell extracts of CLL cells was used as a positive control. (D) Freshly isolated CLL 18 cells were incubated for 3 hours with increasing concentrations (2.5-12.5nM) of the CRM1 inhibitor leptomycin B. Nuclear extracts were fractionated and analyzed by Western immunoblotting using anti-STAT3 and antilamin B1 (nuclear protein control) antibodies. Vertical lines indicate realignment of the same gel's image.

Serine pSTAT3 binds to the nucleocytoplasmic transport proteins importin-β1 and CRM1. Total cell, cytoplasmic (Cyt), and nuclear (Nuc) extracts were obtained from CLL cells (CLL 16 and 17), as described in “Isolation of nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts.” Whole-cell extracts, Cyt, and Nuc fractions were immunoprecipitated (I.P.) with anti-STAT3 (A), -importin-β1 (B), and -CRM1 (C) antibodies using protein A–agarose beads. Incubation with beads only (B) was used as a negative control. The immune complex was separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western immunoblotting using the indicated antibodies. Expression of STAT3, serine pSTAT3, importin-β1, importin-α1, -α3, -α6, -α5 and 7, and CRM1 in total cell extracts of CLL cells was used as a positive control. (D) Freshly isolated CLL 18 cells were incubated for 3 hours with increasing concentrations (2.5-12.5nM) of the CRM1 inhibitor leptomycin B. Nuclear extracts were fractionated and analyzed by Western immunoblotting using anti-STAT3 and antilamin B1 (nuclear protein control) antibodies. Vertical lines indicate realignment of the same gel's image.

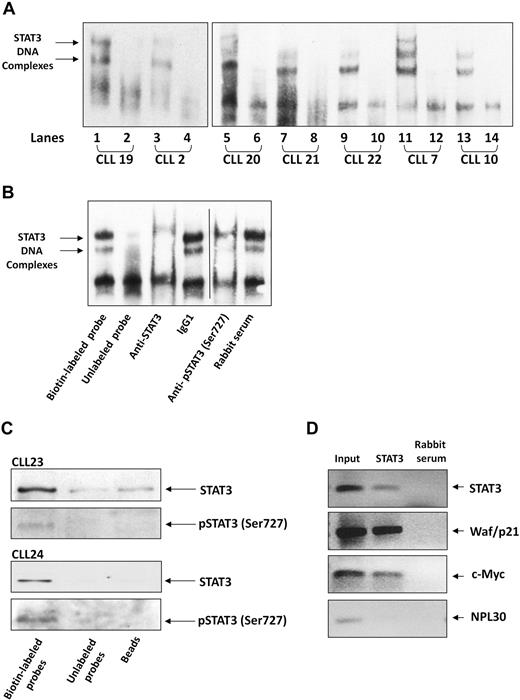

Serine pSTAT3 binds to DNA in CLL cells

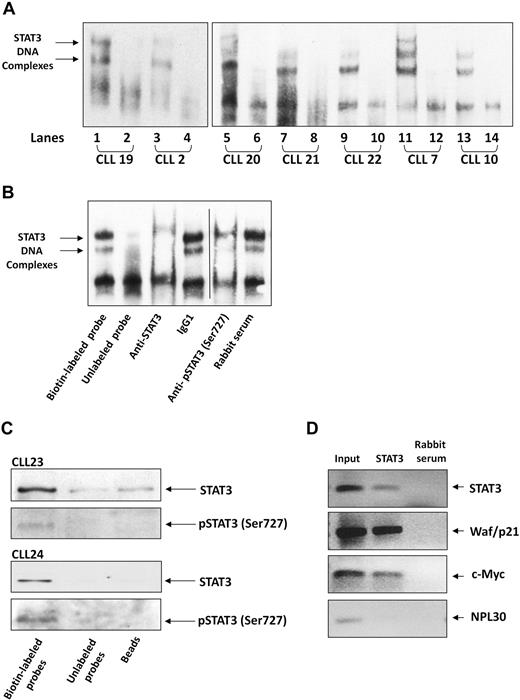

After establishing that serine pSTAT3 translocates to the nucleus of CLL cells, we sought to determine whether nuclear serine pSTAT3 binds to DNA. As shown in Figure 4A, we found that nuclear extracts from 7 different CLL patients bound STAT3 DNA-specific probes. Using EMSA, we identified 2 different complexes (marked by arrows) representing probable STAT3 dimers. To confirm the specificity of DNA binding, we performed a competition assay using a 100-fold excess of unlabeled STAT3 DNA-specific probe (cold probe). To further confirm that nuclear serine pSTAT3 binds DNA, we first exposed CLL cell nuclear extracts to anti-STAT3 or antiserine pSTAT3 antibodies, added the labeled DNA probe, and then conducted EMSA. As shown in Figure 4B, binding of STAT3 to DNA was eliminated by anti-STAT3 or antiserine pSTAT3 antibodies but unaffected by the isotypic control or rabbit serum. To further verify that serine pSTAT3 binds to DNA, we performed pull-down experiments using a biotin-labeled STAT3 DNA-specific probe. In these experiments, CLL cell nuclear extracts were incubated with the biotin-labeled DNA probe and streptavidin-agarose beads were added to pull down the interacting proteins. As a control, we used an unlabeled STAT3 DNA-specific probe, incubated it with nuclear extracts, and added streptavidin-agarose beads or, alternatively, incubated nuclear extracts with streptavidin-agarose beads only. The interacting proteins were separated by SDS-electrophoresis, and STAT3 or serine pSTAT3 was detected by Western immunoblotting. As shown in Figure 4C, nuclear serine pSTAT3 and STAT3 bound the DNA-specific probes. Pull-down either with unlabeled probe or beads showed significantly less, or a complete lack of, binding. To validate these data, we performed a chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay. As shown in Figure 4D, STAT3 coimmunoprecipitated DNA of STAT3-regulated genes (STAT3, waf1/p21, and c-Myc) from chromatin obtained from CLL cells, implying that STAT3 is constitutively activated and binds DNA in these cells. Taken together, these results suggest that nuclear serine pSTAT3 binds to STAT3-specific DNA binding sites in unstimulated CLL cells.

Serine pSTAT3 binds DNA. (A) Nuclear extracts from 7 CLL patients (CLL 2, 7, 10, and 19-22) were analyzed using EMSA, as described in “EMSA.” Binding of STAT3 to biotin-labeled DNA probes is shown (lanes 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, and 13). To compete with the binding, an unlabeled STAT3 binding-site DNA probe was added to the reaction in 100 times molar excess (lanes 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, and 14). The 2 STAT3-DNA complexes are marked by arrows. (B) Elimination of STAT3-DNA binding by antibodies to STAT3 or serine pSTAT3. Nuclear extract of CLL patient 9 was studied by EMSA. The assay was conducted with biotin-labeled STAT3 binding-site DNA probe (lane 1) or with unlabeled probe (lane 2), with the addition of mouse anti–human STAT3 antibodies (lane 3), mouse immunoglobulin G1 isotype control (lane 4), rabbit anti–human serine pSTAT3 (lane 5), or rabbit serum (lane 6). Vertical line indicates realignment of the gel's image. (C) Pull-down of STAT3 by biotin-labeled DNA probe. Nuclear extract from CLL 23 and 24 was incubated with biotin-labeled STAT3 binding-site DNA probe and agarose-conjugated streptavidin beads. The attached proteins were separated by SDS electrophoresis, and STAT3 and serine pSTAT3 were detected by Western blot analysis (Biotin-labeled probe). Incubation of nuclear extracts with unlabeled STAT3 binding-site DNA probes (Unlabeled probe) and agarose-conjugated streptavidin beads only (Beads) were used as negative controls. (D) ChIP assay of CLL cells. CLL cell-derived chromatin was immunoprecipitated with STAT3 or rabbit serum (control). The coimmunoprecipitated DNA was amplified by PCR using upstream promoter constructs of STAT3, waf1/p21, c-Myc, or the control gene RPL30. As shown, STAT3-regulated (STAT3, waf1/p21, and c-Myc), but not control (RPL30), genes were amplified. RPL30 as well as STAT3, waf1/p21, and c-Myc genes were detected in whole cell chromatin-extracted DNA (Input).

Serine pSTAT3 binds DNA. (A) Nuclear extracts from 7 CLL patients (CLL 2, 7, 10, and 19-22) were analyzed using EMSA, as described in “EMSA.” Binding of STAT3 to biotin-labeled DNA probes is shown (lanes 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, and 13). To compete with the binding, an unlabeled STAT3 binding-site DNA probe was added to the reaction in 100 times molar excess (lanes 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, and 14). The 2 STAT3-DNA complexes are marked by arrows. (B) Elimination of STAT3-DNA binding by antibodies to STAT3 or serine pSTAT3. Nuclear extract of CLL patient 9 was studied by EMSA. The assay was conducted with biotin-labeled STAT3 binding-site DNA probe (lane 1) or with unlabeled probe (lane 2), with the addition of mouse anti–human STAT3 antibodies (lane 3), mouse immunoglobulin G1 isotype control (lane 4), rabbit anti–human serine pSTAT3 (lane 5), or rabbit serum (lane 6). Vertical line indicates realignment of the gel's image. (C) Pull-down of STAT3 by biotin-labeled DNA probe. Nuclear extract from CLL 23 and 24 was incubated with biotin-labeled STAT3 binding-site DNA probe and agarose-conjugated streptavidin beads. The attached proteins were separated by SDS electrophoresis, and STAT3 and serine pSTAT3 were detected by Western blot analysis (Biotin-labeled probe). Incubation of nuclear extracts with unlabeled STAT3 binding-site DNA probes (Unlabeled probe) and agarose-conjugated streptavidin beads only (Beads) were used as negative controls. (D) ChIP assay of CLL cells. CLL cell-derived chromatin was immunoprecipitated with STAT3 or rabbit serum (control). The coimmunoprecipitated DNA was amplified by PCR using upstream promoter constructs of STAT3, waf1/p21, c-Myc, or the control gene RPL30. As shown, STAT3-regulated (STAT3, waf1/p21, and c-Myc), but not control (RPL30), genes were amplified. RPL30 as well as STAT3, waf1/p21, and c-Myc genes were detected in whole cell chromatin-extracted DNA (Input).

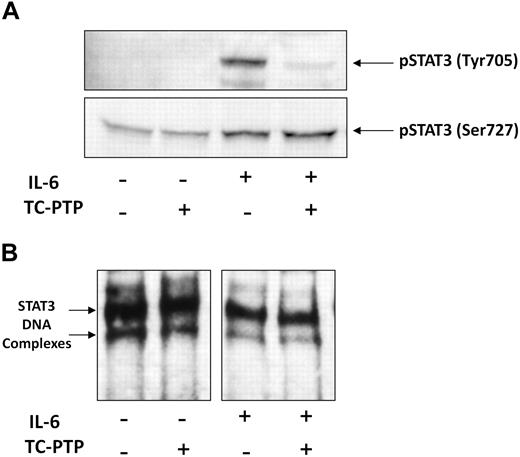

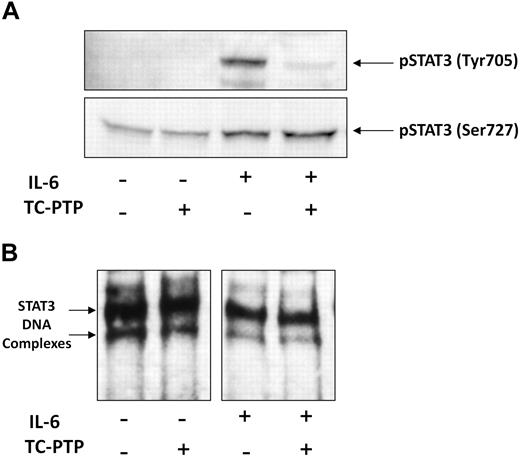

Dephosphorylation of tyrosine pSTAT3 does not affect the binding of STAT3 to DNA

It is thought that tyrosine phosphorylation is required for DNA binding,31,34,35 but in CLL, STAT3 is phosphorylated on serine, not tyrosine, residues. Therefore, we sought to examine how tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT3 affects DNA binding in CLL cells. To induce tyrosine pSTAT3, we incubated low-density CLL cells with 50 ng/mL IL-6. To dephosphorylate tyrosine pSTAT3, we incubated nuclear extract of the IL-6–stimulated CLL cells with the STAT3 T-cell TC-PTP. Then, we performed Western immunoblotting and EMSA. As shown in Figure 5A, IL-6 induced tyrosine phosphorylation and slightly increased serine phosphorylation of STAT3, whereas TC-PTP completely abolished the IL-6–induced tyrosine phosphorylation but did not affect serine pSTAT3 in untreated or IL-6–stimulated cells. Furthermore, although TC-PTP efficiently dephosphorylated tyrosine pSTAT3 in nuclear extracts of CLL cells, TC-PTP did not affect DNA binding of STAT3 to biotin-labeled DNA in either untreated or IL-6–stimulated cells (Figure 5B), suggesting that STAT3-DNA binding does not require tyrosine phosphorylation and that serine pSTAT3 binds DNA in CLL cells.

TC-PTP dephosphorylates IL-6–induced tyrosine pSTAT3 but does not affect STAT3-DNA binding. CLL cells (CLL 16 and 25) were incubated for 30 minutes, with or without 50 ng/mL IL-6. Nuclear fractions were extracted and treated with TC-PTP for 30 minutes, as described in “EMSA.” After TC-PTP treatment, nuclear extracts were analyzed by (A) Western blot analysis using antityrosine pSTAT3 and antiserine pSTAT3 to detect the corresponding proteins or (B) EMSA to detect binding of STAT3 to the biotin-labeled DNA probe, as described in “EMSA.”

TC-PTP dephosphorylates IL-6–induced tyrosine pSTAT3 but does not affect STAT3-DNA binding. CLL cells (CLL 16 and 25) were incubated for 30 minutes, with or without 50 ng/mL IL-6. Nuclear fractions were extracted and treated with TC-PTP for 30 minutes, as described in “EMSA.” After TC-PTP treatment, nuclear extracts were analyzed by (A) Western blot analysis using antityrosine pSTAT3 and antiserine pSTAT3 to detect the corresponding proteins or (B) EMSA to detect binding of STAT3 to the biotin-labeled DNA probe, as described in “EMSA.”

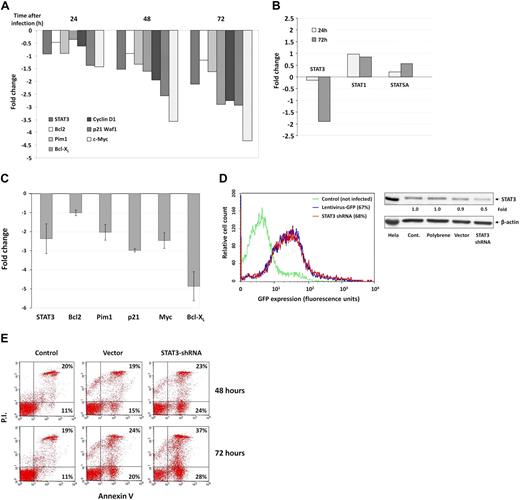

Serine pSTAT3 activates transcription of STAT3-regulated genes in CLL cells

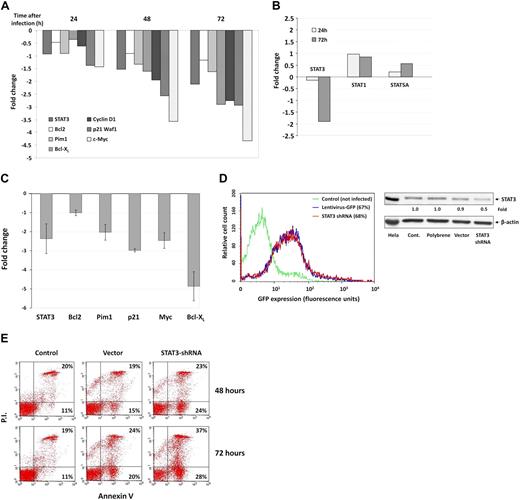

Because serine pSTAT3 binds to DNA, we sought to determine whether serine pSTAT3 affects the gene transcription of STAT3-regulated genes. We infected CLL cells with a lentivirus harboring GFP-STAT3-shRNA and, as a control, with lentivirus GFP-empty vector. Infection efficiency ranged from 40% to 70% as assessed by flow cytometry. STAT3-regulated gene transcription was analyzed after purification of RNA from infected CLL cells 24, 48, and 72 hours after infection, and RNA levels of various STAT3-regulated genes were determined by RT-PCR. As shown in Figure 6A, infection with GFP-STAT3-shRNA reduced mRNA levels of STAT3 and the STAT3-regulated genes Bcl2, Pim1, Bcl-XL, Cyclin D1, p21 (Waf1), and c-Myc in a dose-dependent fashion. Infection with GFP-STAT3-shRNA did not affect STAT1 and STAT5A mRNA levels 24 and 72 hours after infection (Figure 6B), confirming that the effect of STAT3-shRNA was specific. To confirm these findings cells from 4 patients with CLL were infected with STAT3-shRNA and analyzed 72 hours after infection. In all cases, we observed a reduction in mRNA levels of STAT3-regulated genes (Figure 6C). Remarkably, infection with GFP-STAT3-shRNA at a level similar to the infection level obtained with empty virus (Figure 6D left panel) down-regulated total (phosphorylated and unphosphorylated) STAT3 protein levels by 50% (Figure 6D right panel) and significantly increased the number of annexin V+ cells, by 13% (P < .001) after 48 hours and by 21% (P < .001) after 72 hours, suggesting that STAT3-shRNA induced apoptosis of CLL cells (Figure 6E). Because the infection efficiency of the empty virus was similar to that of the STAT3-shRNA, it is doubtful that infection by itself was responsible for the high apoptosis rate induced by STAT3-shRNA.

Serine pSTAT3 initiates transcription of STAT3-regulated genes in CLL cells. CLL cells were infected with a lentivirus harboring GFP-STAT3-shRNA or with lentivirus GFP-empty vector. (A) RT-PCR results of mRNA levels of STAT3 and the STAT3-regulated genes Bcl2, Pim1, Bcl-XL, Cyclin D1, p21 (Waf1), and c-Myc in CLL cells (CLL 26) that were infected by lentivirus harboring GFP-STAT3-shRNA for 24, 48, and 72 hours. (B) RT-PCR results of mRNA levels of STAT1, STAT3, and STAT5 in CLL cells (CLL 26) that were infected by lentivirus harboring GFP-STAT3-shRNA for 24 and 72 hours. The RT-PCR results are shown as fold change (decrease or increase) relative to the mRNA levels of the STAT3-regulated genes in CLL cells that were infected with lentiviral GFP-empty vector. (C) RT-PCR results of mRNA levels of the STAT3-regulated genes STAT3, Bcl2, Pim1, Bcl-XL, p21 (Waf1), and c-Myc in CLL cells (CLL 15, 19, 24, and 27). Changes in mRNA levels (mean ± SD) are shown. As in the previous experiment, infection with empty virus did not significantly affect STAT3-regulated gene levels. (D) Left panel: Infection efficiency analyzed by flow cytometry of control and GFP+ empty virus– and STAT3-shRNA–infected CLL cells (CLL 26). Right panel: Western blot of control, empty vector- and STAT3 shRNA-infected CLL cells. Forty-eight hours after infection with STAT3, shRNA down-regulated STAT3 protein levels by 50%. (E) Flow cytometric analysis of PI+/− and annexin V+ cells 48 and 72 hours after infection with GFP-STAT3-shRNA or empty vector. The percentages of early apoptotic cells are shown in the bottom right corners and of late apoptotic (PI− and annexin V+) cells in the top right corners.

Serine pSTAT3 initiates transcription of STAT3-regulated genes in CLL cells. CLL cells were infected with a lentivirus harboring GFP-STAT3-shRNA or with lentivirus GFP-empty vector. (A) RT-PCR results of mRNA levels of STAT3 and the STAT3-regulated genes Bcl2, Pim1, Bcl-XL, Cyclin D1, p21 (Waf1), and c-Myc in CLL cells (CLL 26) that were infected by lentivirus harboring GFP-STAT3-shRNA for 24, 48, and 72 hours. (B) RT-PCR results of mRNA levels of STAT1, STAT3, and STAT5 in CLL cells (CLL 26) that were infected by lentivirus harboring GFP-STAT3-shRNA for 24 and 72 hours. The RT-PCR results are shown as fold change (decrease or increase) relative to the mRNA levels of the STAT3-regulated genes in CLL cells that were infected with lentiviral GFP-empty vector. (C) RT-PCR results of mRNA levels of the STAT3-regulated genes STAT3, Bcl2, Pim1, Bcl-XL, p21 (Waf1), and c-Myc in CLL cells (CLL 15, 19, 24, and 27). Changes in mRNA levels (mean ± SD) are shown. As in the previous experiment, infection with empty virus did not significantly affect STAT3-regulated gene levels. (D) Left panel: Infection efficiency analyzed by flow cytometry of control and GFP+ empty virus– and STAT3-shRNA–infected CLL cells (CLL 26). Right panel: Western blot of control, empty vector- and STAT3 shRNA-infected CLL cells. Forty-eight hours after infection with STAT3, shRNA down-regulated STAT3 protein levels by 50%. (E) Flow cytometric analysis of PI+/− and annexin V+ cells 48 and 72 hours after infection with GFP-STAT3-shRNA or empty vector. The percentages of early apoptotic cells are shown in the bottom right corners and of late apoptotic (PI− and annexin V+) cells in the top right corners.

Discussion

Here, we demonstrate that, like tyrosine pSTAT3,13,34,36 serine pSTAT3 translocates to the nucleus, binds to DNA, and activates transcription. Constitutive phosphorylation of STAT3 on serine 727 residues in CLL cells is biologically significant25,37 and most probably plays a role in the pathogenesis of CLL, as it activates transcription of survival and proliferation genes.

Our data confirm that, unlike in normal B lymphocytes, in all CLL cells STAT3 is constitutively phosphorylated on serine 727, but not on tyrosine 705, residues. Whereas tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT3 is thought to be required for STAT3 activation,21,31 the biologic significance of serine phosphorylation is still unclear.21,22,38-40 Some reports suggest that serine-phosphorylated STAT proteins are required for maximum tyrosine phosphorylation, DNA binding, and transcriptional activity,21,35 whereas other studies showed that either serine phosphorylation inhibits tyrosine phosphorylation23,24,41 or serine phosphorylation of STATs has no effect on tyrosine phosphorylation or DNA binding.22 An animal model highlighted the importance of STAT3 serine phosphorylation. STAT3 mutant mice, harboring only 1 allele of STAT3 where serine 727 was mutated to alanine, were smaller and their thymocytes had a short life span.42 The net effect of serine pSTAT3 probably depends on the type of extracellular stimulus, the cell type, and the activation status of the cell in question. For example, constitutive activation of STAT3 in B1 lymphocytes induced intrinsic proliferative behavior.43 Because STAT3 is constitutively phosphorylated exclusively on serine 727 residues in CLL cells, this disease provides us with a model to establish the biologic role of serine pSTAT3.

CLL cells reside in the bone marrow, blood, and lymph nodes and are exposed to cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors capable of inducing tyrosine phosphorylation. Indeed, as previously reported,28-30 it is possible to induce tyrosine pSTAT3 in CLL cells. In the current study, we induced tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT3 by incubating CLL cells with IL-6. However, the IL-6–induced tyrosine phosphorylation was transient. Shortly after removal of IL-6, tyrosine pSTAT3 was no longer detected. In contrast, serine pSTAT3 did not require induction and its levels remained stable in vitro for up to 72 hours. Thus, although it is possible to induce phosphorylation of STAT3 on tyrosine 705 residues in CLL cells, only the phosphorylation on serine 727 residues is constitutive.

To determine whether serine pSTAT3 is biologically active, we first thought to determine whether serine pSTAT3 translocates to the nucleus. Using CLL cell cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts, we demonstrated that serine pSTAT3 is present in both the cytoplasm and the nucleus. We confirmed this observation using confocal microscopy. Our results agree with those of Lee et al,37 who demonstrated that serine pSTAT3 is present in the nucleus of CLL cells. The nucleocytoplasmic transport mechanism used to shuttle serine pSTAT3 into the nucleus has not been previously reported. Some STAT proteins constitutively shuttle between the nucleus and cytoplasm, whereas others require tyrosine phosphorylation for nuclear localization.33,44 Little is known about the STAT transport mechanism in fresh leukemia cells, and no data are available on serine pSTAT3. To identify which nucleocytoplasmic transport mechanism translocates serine pSTAT3 from the cytoplasm to the nucleus in CLL cells, we performed a series of immunoprecipitation experiments and found that importin-β1 coimmunoprecipitated with serine pSTAT3 in whole-cell, cytoplasmic, and nuclear extracts. However, whereas previous studies showed that importin-α3 and -α6 bind STAT3,33,45 we could not determine which member of the importin-α family binds serine pSTAT3 to form a complex with importin β1 because none of the α-importins (importin-α1, -α3, -α5, -α6, or -α7) coimmunoprecipitated with STAT3 or importin-β1. Thus, either one of those α-importins is operative, but failed to coimmunoprecipitate, or an unidentified adaptor binds serine pSTAT3. Using the same methodology, we found that STAT3 immunoprecipitates CRM1 and accumulates in the nucleus after exposure to the CRM1 inhibitor leptomycin B, suggesting that CRM1 exports STAT3 form the nucleus to the cytoplasm in CLL cells.

After verifying that serine pSTAT3 translocates to the nucleus of CLL cells, we asked whether serine pSTAT3 binds to DNA. Using methods previously used to establish that tyrosine pSTAT3 binds DNA,21,31 we demonstrated that serine pSTAT3 binds to a STAT3-specific DNA probe by showing that STAT3-DNA binding was eliminated by antiserine pSTAT3 antibodies. Furthermore, we showed that the biotin-labeled STAT3-specific DNA probe pulled down serine pSTAT3 and that STAT3-immunoprecipitated CLL cell chromatin fragments harbor STAT3-regulated genes, further implying that serine pSTAT3 is constitutively bound to DNA in CLL cells. Finally, we demonstrated that dephosphorylation of IL-6–induced tyrosine pSTAT3 did not affect STAT3-DNA binding, confirming that, unlike in other cellular systems,21,31 in CLL cells constitutive serine pSTAT3 binds to DNA.

Whether DNA-bound serine pSTAT3 initiates transcription in fresh human cells is controversial. To establish whether serine pSTAT3 activates transcription in CLL, we infected CLL cells with a lentiviral GFP-STAT3-shRNA and assessed the changes in mRNA levels using relative real-time PCR. Infection with GFP-STAT3-shRNA induced up to a 4-fold time-dependent reduction in the STAT3-regulated survival and proliferation genes STAT3, Bcl2, Pim1, Bcl-xL, p21 (Waf1), and c-Myc. Forty-eight hours after infection STAT3 protein levels were reduced by 50%. Taken together, these data suggest that serine pSTAT3 initiates transcription. The reduction in Bcl2 mRNA levels was the least prominent, probably because STAT3 is not the only factor that regulates Bcl2 gene expression. Several other factors, such as promoter methylation,46 loss of mir15a and mir16-1,7 and nucleolin expression,47 regulate Bcl2 gene expression in CLL cells. Nevertheless, infection with GFP-STAT3-shRNA induced apoptosis of CLL cells. As in other cell types,48 binding of activated STAT3 to DNA induces the production of STAT3; and, as a result, high levels of unphosphorylated STAT3 are produced by CLL cells (Figure 1C). Unphosphorylated STAT3 binds nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), and the STAT3-NF-κB complex binds to DNA and activates NF-κB-regulated genes, such as RANTES.49 Remarkably, NF-κB was found to be constitutively activated in CLL cells through an undetermined mechanism.50 Further study will determine whether the activation of NF-κB is induced by unphosphorylated STAT3.

Although STAT3 is constitutively phosphorylated on serine 727 residues in all patients with CLL regardless of clinical characteristics, disease stage, or treatment status, various known, or yet unknown, aberrations contribute to the pathobiology and clinical outcome of this disease. The known cytogenetic and molecular abnormalities in CLL do not point toward an abnormality that might induce serine phosphorylation of STAT3 in all patients with CLL. The mechanism(s) responsible for induction of serine pSTAT3 in CLL remain(s) to be determined.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Susan Lerner for retrieving the patients' clinical data and Dawn Chalaire for editing the manuscript.

This work was supported by the CLL Global Research Foundation (Z.E.), the National Institutes of Health (GM068566), and the Welch Foundation (G-1499; X.C.).

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: I.H.-H. planned, performed, and analyzed experiments and wrote the paper; D.H. performed confocal microscopy studies and FACS analysis; Z.L. performed immunoprecipitation experiments; J.L. performed retroviral infection studies; P.L. performed the ChIP experiments; X.C. contributed to the experimental design and data analysis; S.S. synthesized and studied TC-PTP; A.F. and M.J.K. treated the studied patients, provided clinical samples, and analyzed the data; and Z.E. initiated, designed, and supervised the research.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Zeev Estrov, Department of Leukemia, Unit 402, M. D. Anderson Cancer Center, 1515 Holcombe Blvd, Houston, TX 77030; e-mail: zestrov@mdanderson.org.