Abstract

The majority of long-term reconstituting hematopoietic stem cells (LT-HSCs) in the adult is in G0, whereas a large proportion of progenitors are more cycling. We show here that the SCL/TAL1 transcription factor is highly expressed in LT-HSCs compared with short-term reconstituting HSCs and progenitors and that SCL negatively regulates the G0-G1 transit of LT-HSCs. Furthermore, when SCL protein levels are decreased by gene targeting or by RNA interference, the reconstitution potential of HSCs is impaired in several transplantation assays. First, the mean stem cell activity of HSCs transplanted at approximately 1 competitive repopulating unit was 2-fold decreased when Scl gene dosage was decreased. Second, Scl+/− HSCs were at a marked competitive disadvantage with Scl+/+ cells when transplanted at 4 competitive repopulating units equivalent. Third, reconstitution of the stem cell pool by adult HSCs expressing Scl-directed shRNAs was decreased compared with controls. At the molecular level, we found that SCL occupies the Cdkn1a and Id1 loci in primary hematopoietic cells and that the expression levels of these 2 regulators of HSC cell cycle and long-term functions are sensitive to Scl gene dosage. Together, our observations suggest that SCL impedes G0-G1 transition in HSCs and regulates their long-term competence.

Introduction

The lifelong production of blood cells depends on the regenerative capacity of a small population of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) that reside normally in the bone marrow, in the adult. This property forms the basis of HSC assays in which grafted donor cells are tested for their capacities for long-term reconstitution in all blood lineages of a transplanted host. The long-term persistence of clones initiated by HSCs depends critically on their ability to sustain self-renewal over time and over multiple HSCs divisions, thus their capacity for lifelong blood cell production. HSCs with reconstituting potential that do not sustain self-renewal activity generate clones that eventually lose stem cell activity and are detectable as transient reconstitutions in transplantation assays.1 The mechanisms that sustain self-renewal remain to be further elucidated because only a few genes have been implicated in this process.2

In the adult, HSCs mostly reside in G03 and are triggered into cycling by chemotoxic injuries,4 by exposure to cytokines in vitro,5 or by transplantation in vivo.6 The state of quiescence in HSCs is reversible3 and differs from quiescence associated with senescence, differentiation, or growth factor deprivation.2,7 This suggests the existence of mechanisms that actively maintain HSCs in G0. Such regulation is critical for long-term stem cell function,2 as exemplified by several gene deletion models. HSCs from mice that are deficient for Cdkn1a or Id1 exhibit impaired long-term activity, associated with increased cycling.8,9 In addition, HSC quiescence is maintained by the opposing activities of Gfi110,11 and Mef,12 although the transcriptional circuitry that actively maintains HSCs quiescence remains to be documented.13

Cell cycle and quiescence are actively controlled at critical transition points in the hematopoietic hierarchy. Unlike HSCs, a significant proportion of hematopoietic progenitors are found in S phase. For example, erythroid progenitors are highly proliferative,14,15 whereas transition to terminal erythroid differentiation is coupled with growth arrest. We recently showed that the SCL transcription factor controls the transition between a proliferative state and commitment to differentiation and growth arrest in erythroid progenitors by up-regulating Gfi1b and Cdkn1a expression,16 together with erythroid gene expression.17,18 The critical role of Scl in generating HSCs during development is well documented,19 but there is controversy with regards to its function in adult HSCs. For example, conditional knockout experiments suggest that Scl may be dispensable20,21 and possibly redundant with other factors,22 whereas decreasing SCL function by delivery of a dominant negative SCL or Scl-directed shRNA in human cells impaired their SCID-repopulating ability.23,24 Nonetheless, gene profiling of HSCs (Sca1+Lin− side population) identified a quiescence signature characterized by increased Scl and Cdkn1a expression.25 In the present study, we address the role of SCL in HSC quiescence control and their long-term integrity.

Methods

Mice

Scl+/− mice26 were a generous gift from Dr Glenn C. Begley (Amgen Inc). These mice were maintained on a C57BL/6 background for more than 10 generations. B6.SJL-Ptprca Pep3b/BoyJ mice are from The Jackson Laboratory. All mice were kept under pathogen-free conditions according to institutional animal care and use guidelines. The protocols for the transgenic and knockout mice, as well as bone marrow transplantation in mice, were approved by the Committee of Ethics and Animal Deontology of the University of Montreal.

Flow cytometry and cell-cycle analysis

Bone marrow cells from 2-month-old mice were depleted of lineage-positive (Lin+) cells through immunomagnetic bead cell separation as detailed in supplemental data (available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). The remaining Lin+ cells were further excluded by flow cytometry using fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)– or biotin-conjugated antibodies against lineage markers CD3, B220, Gr1, CD11b, and TER119.

Kit+Sca1+Lin−CD150+CD48− (long-term reconstituting hematopoietic stem cells [LT-HSCs]) labeling and cell sorting were performed according to Kiel et al27 (supplemental data). Kit+Sca1+Lin− (KSL), common myeloid progenitor (CMP), granulocyte-monocyte progenitor (GMP), and megakaryocyte-erythroid progenitor (MEP) were purified as reported28 with further exclusion of FcαR+ and IL7-Rα+ cells. Common lymphoid progenitors (CLPs) were purified as described29 (supplemental data). Dead cells were excluded by propidium iodide staining. Analyses were performed on the LSRII (BD Biosciences) and cell sorting on the FACSAria.

For cell-cycle analysis, lineage-depleted bone marrow cells were stained with Hoechst and Pyronin Y with rotation. Cells were incubated at 37°C with Hoechst 33342 (10 μg/mL; Invitrogen) for 45 minutes in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium supplemented with 2% fetal calf serum, followed by Pyronin Y labeling (1 μg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 minutes. Cells were then washed and labeled for cell-surface markers (Kit, Sca1, CD150, CD48, and Lin). Where indicated, lineage-depleted cells were stimulated in culture for 24 hours with Steel Factor (100 ng/mL), interleukin-11 (IL-11; 100 ng/mL), and interleukin-6 (IL-6; 10 ng/mL). Cell-cycle analyses were performed on the LSRII at low flow rate.

For bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) labeling and staining, mice received an initial intraperitoneal injection of 3 mg of BrdU, followed by 3 days of BrdU in drinking water (1 mg/mL). BrdU incorporation in LT-HSCs was detected by flow cytometry with the FITC-BrdU flow kit (BD Biosciences).

Fluorescein-di-β-D-galactopyranoside staining

Gene expression analysis and Western blotting

For reverse-transcribed polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis, total RNA was extracted from 10 000 FACS-purified cells (FACSAria) for reverse transcription, as described.31 PCR primers and antibodies used for Western blotting are described in supplemental data.

Transplantation assays

Limiting dilution analysis was performed essentially as described.32 Briefly, Scl+/− test cells (CD45.2+) were transplanted into irradiated hosts (CD45.1+) at various cell doses ranging from 5000 to 106 per recipient mouse, together with a life-sparing dose (105) of bone marrow cells (CD45.1+; supplemental data).

The level of lympho-myeloid reconstitution was assessed by flow cytometric analysis of the peripheral blood with antibodies against Gr1 (granulocytes), CD11b (myeloid cells), B220 (B lineage), and CD3 (T cells) 6 months after transplantation. Mice were scored positive when multilineage reconstitution was more than 1%. Competitive repopulating unit (CRU) frequencies were calculated by applying Poisson statistics using the Limit Dilution Analysis software (StemCell Technologies).

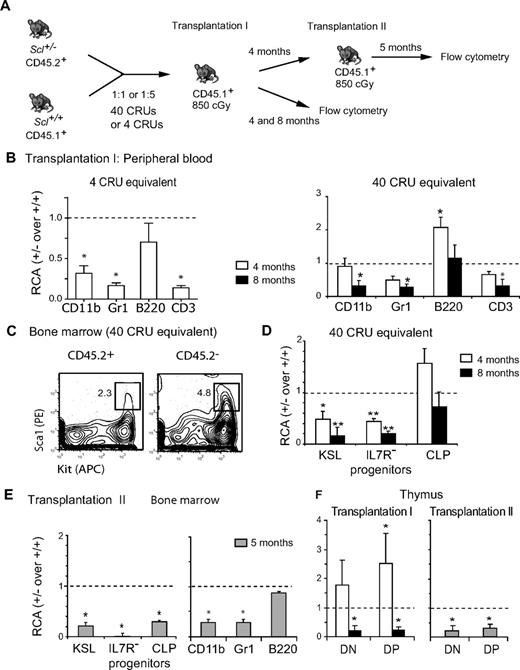

Competitive repopulating assays were performed using total bone marrow cells as follows. Scl+/− test cells (CD45.2+) were transplanted with Scl+/+ competitor cells from age-matched donors (CD45.1+) at 2 ratio of test (T) over competitor (C) cells (T/C of 1/1 or 1/5) into congenic lethally irradiated (850 cGy) hosts (CD45.1+), for a total of 2 × 106 donor cells per recipient. Five recipients were injected for each condition. The contribution of Scl+/− cells to hematopoiesis was evaluated 4 and 8 months after transplantation by flow cytometry and the relative competitive advantage (RCA) of Scl+/− cells was calculated as follows:

The input mixture was assessed by flow cytometry before transplantation to obtain the exact input T/C ratio. For secondary transplantation, bone marrow cells from primary recipients were harvested 4 months after transplantation and 2 × 107 cells were injected into irradiated recipient mice. Reconstitution of secondary recipients was analyzed 4 to 5 months after transplantation.

The mean activity of stem cells (MAS) is calculated according to the Harrison formula33,34 : MAS = [RU]/[CRU] where RU represents the repopulating activity of 105 bone marrow cells and CRU was derived by limiting dilution analysis32 as above. RU was calculated as previously described: RU = [T × number of competitors × 10−5]/C.

Because the number of competitors was 105, the formula was applied as follows: RU = [T/C]. In mice transplanted with a dose of test cells corresponding to 1 CRU, then MAS = RU; therefore, MAS = [T/C].

Chromatin immunoprecipitation, production of lentivirus, shRNA gene transfer, and transplantation of puromycin-selected cells

This information is described in supplemental data. Primer sequences are shown in supplemental Table 1.

Statistical analyses

Where indicated, groups were compared using the Student t test.

Results

Elevated Scl expression in dormant adult LT-HSCs

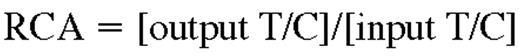

To monitor Scl expression in LT-HSCs, we purified the Kit+Sca1+Lin−CD150+CD48− population27 (Figure 1), which was independently confirmed by transplantation to be enriched in long-term HSCs in the proportion of one-half to one-fifth of cells35 and will be referred to as cells with an LT-HSC phenotype. The KSL population is more heterogeneous and includes both short-term reconstituting HSCs (ST-HSCs) and LT-HSCs, whereas Kit+Sca1−Lin− progenitors are devoid of stem cell activity and could be further fractionated into common myeloid progenitor, granulocyte-monocyte progenitor, and MEP28,29 (Figure 1A,C). We found that cells with an LT-HSC phenotype were mostly in G0; ie, these cells exhibit low labeling with the DNA dye, Hoechst 33342, and the RNA dye, Pyronin Y,36 whereas the KSL population was equally distributed in G0 and G1, and the Kit+Sca1− population was mostly in G1 (Figure 1B).37 Scl expression was first assessed by quantitative RT-PCR and was found to be present in all populations, including CLP. Nonetheless, we observed significant variations in Scl transcript levels, which were reproducibly highest in cells with an LT-HSC phenotype and lower in KSL cells (Figure 1C). In progenitors, Scl levels were higher in MEP compared with the others, consistent with previous reports.38 Interestingly, these differential Scl levels were also observed when the activity of the Scl gene was monitored using the Scl-LacZ mouse model (hereafter Scl+/− mice) in which the LacZ gene was inserted into the Scl locus.26 Indeed, β-galactosidase activities were 2.4- and 3.5-fold higher in cells with an LT-HSC phenotype than in KSL and progenitors, respectively (Figure 1D). Furthermore, this experiment indicated that the Scl locus is transcriptionally active in all HSCs/progenitors at the single-cell level.

Scl expression in HSCs correlates with quiescence. (A) Schematic diagram of hematopoietic populations and their cell-surface markers. HSCs are KSL, which include LT-HSCs (CD150+CD48−) and ST-HSCs. Progenitors that are devoid of stem cell activity are Kit+Sca1−Lin−, except for CLPs, which are KitloSca1loLin− and express IL7R. Progenitors can be further differentiated on the basis of CD34 and FcγR expression. (B) The cell-cycle status of HSCs and progenitors assessed by Hoechst 33342 (DNA) and Pyronin Y (RNA) staining. G0, G1, and S-G2-M are defined as shown (dot plots are representative of 5 independent experiments). (C) Scl mRNA levels in purified populations from adult mice were assessed by quantitative RT-PCR and normalized using Hprt. Expression levels in LT-HSCs were set as 1 (mean ± SD of 3 experiments). (D) Scl gene expression was monitored by β-galactosidase staining (FDG) and flow cytometric analysis in LT-HSCs, ST-HSCs, and progenitor populations from Scl+/− mice in which the LacZ gene was inserted into the Scl locus (shaded histograms) and wild-type (white histograms) mice. The mean fluorescence intensities (MFIs) are indicated for Scl+/− populations. Data shown are representative of 2 independent experiments with groups of 3 or 5 mice each. (E) LT-HSC–enriched populations were further purified into G0 or G1/S/G2/M fractions by flow cytometry with Hoechst and Pyronin Y, as in panel B. Scl and Cdkn1a expression levels were assessed by quantitative RT-PCR. mRNA levels were normalized using Hprt and compared with expression levels in the G0 population (mean ± SD of 4 replicates; 2 experiments).

Scl expression in HSCs correlates with quiescence. (A) Schematic diagram of hematopoietic populations and their cell-surface markers. HSCs are KSL, which include LT-HSCs (CD150+CD48−) and ST-HSCs. Progenitors that are devoid of stem cell activity are Kit+Sca1−Lin−, except for CLPs, which are KitloSca1loLin− and express IL7R. Progenitors can be further differentiated on the basis of CD34 and FcγR expression. (B) The cell-cycle status of HSCs and progenitors assessed by Hoechst 33342 (DNA) and Pyronin Y (RNA) staining. G0, G1, and S-G2-M are defined as shown (dot plots are representative of 5 independent experiments). (C) Scl mRNA levels in purified populations from adult mice were assessed by quantitative RT-PCR and normalized using Hprt. Expression levels in LT-HSCs were set as 1 (mean ± SD of 3 experiments). (D) Scl gene expression was monitored by β-galactosidase staining (FDG) and flow cytometric analysis in LT-HSCs, ST-HSCs, and progenitor populations from Scl+/− mice in which the LacZ gene was inserted into the Scl locus (shaded histograms) and wild-type (white histograms) mice. The mean fluorescence intensities (MFIs) are indicated for Scl+/− populations. Data shown are representative of 2 independent experiments with groups of 3 or 5 mice each. (E) LT-HSC–enriched populations were further purified into G0 or G1/S/G2/M fractions by flow cytometry with Hoechst and Pyronin Y, as in panel B. Scl and Cdkn1a expression levels were assessed by quantitative RT-PCR. mRNA levels were normalized using Hprt and compared with expression levels in the G0 population (mean ± SD of 4 replicates; 2 experiments).

To address the possibility that Scl expression correlates with quiescence (Figure 1A-D), we subdivided the LT-HSC population into G0 and non-G0 (G1/S/G2/M) fractions and found that Scl expression is higher in the G0 fraction and lower in the other fractions (Figure 1E). Interestingly, this expression pattern was also observed with Cdkn1a, an SCL target gene in erythroid progenitors,16 encoding a negative regulator of the cell cycle. Together, our observations indicate that Scl expression is highest in resting LT-HSCs, whereas its expression is lowered with cell-cycle entry.

Reducing SCL level impairs HSC functions

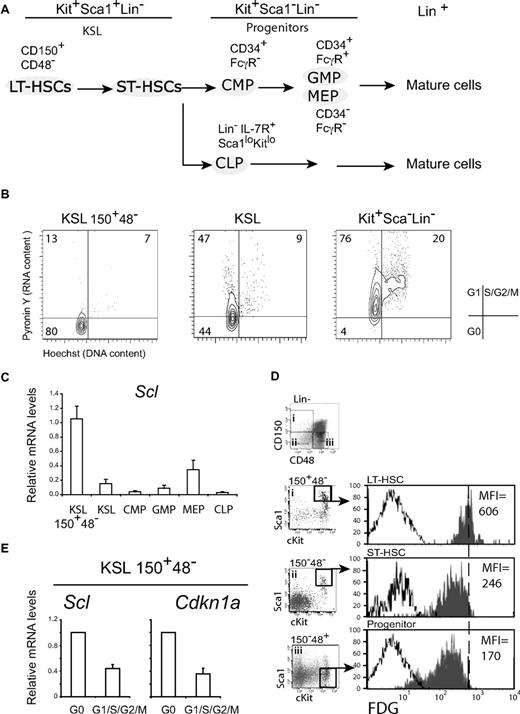

To assess the role of Scl in HSC activity, we took advantage of the Scl+/− mouse (Figure 2A) in which we observed a 2-fold decrease of both p42 and p22 SCL protein isoforms in lineage-depleted bone marrow cells compared with Scl+/+ cells, whereas E47 and PTP1D levels remained constant (Figure 2B). Decreased SCL protein levels did not affect the number of myeloid progenitors in Scl+/− mice at steady state or their proliferative potential compared with their Scl+/+ counterparts (colony assays shown in supplemental Figure 1A-B). To estimate the pool of LT-HSCs, we first assessed the numbers of Kit+Sca1+Lin− CD150+CD48− cells in the femurs of Scl+/− and Scl+/+ mice (Figure 2C) and found this number to be marginally lower in the Scl+/− group. These observations are consistent with a near-normal frequency of CRU estimated in transplantation assays (supplemental Figure 2A), in agreement with published results.21 We next examined stem cell potentials under limiting conditions and assessed their mean repopulating abilities (MAS) in mice grafted with approximately 1 CRU. We observed that the MAS of Scl+/− HSCs was significantly decreased compared with Scl+/+ HSCs (Figure 2D). Thus, despite a near-normal stem cell pool size, Scl+/− HSCs exhibit impaired repopulating potential under conditions of high proliferative demand.

Scl haplodeficiency decreases mean stem cell activity. (A) Experimental scheme. Bone marrow cells from adult Scl+/− mice and Scl+/+ littermates or age-matched controls were processed in parallel. (B) Western blot of total protein extracts were used to assess SCL and E2A protein levels in Scl+/+ and Scl+/− lineage-depleted bone marrow cells. Anti-PTP1D was used as a loading control. Ratio of chemiluminescent intensities from Scl+/− over Scl+/+ samples are shown on the right. (C) The frequency of LT-HSCs in Scl+/+ and Scl+/− mice was assessed by flow cytometric analysis of Kit+Sca1+Lin−CD150+CD48− cells. Shown are box plots with the median and extreme values of each distribution (n mice per group). The 2 distributions are not significantly different (P = .1). (D) The mean stem cell activity (MAS) was calculated in mice receiving approximately 1 CRU, as described in “Transplantation assays.” Box plots as above from n mice; P values as shown.

Scl haplodeficiency decreases mean stem cell activity. (A) Experimental scheme. Bone marrow cells from adult Scl+/− mice and Scl+/+ littermates or age-matched controls were processed in parallel. (B) Western blot of total protein extracts were used to assess SCL and E2A protein levels in Scl+/+ and Scl+/− lineage-depleted bone marrow cells. Anti-PTP1D was used as a loading control. Ratio of chemiluminescent intensities from Scl+/− over Scl+/+ samples are shown on the right. (C) The frequency of LT-HSCs in Scl+/+ and Scl+/− mice was assessed by flow cytometric analysis of Kit+Sca1+Lin−CD150+CD48− cells. Shown are box plots with the median and extreme values of each distribution (n mice per group). The 2 distributions are not significantly different (P = .1). (D) The mean stem cell activity (MAS) was calculated in mice receiving approximately 1 CRU, as described in “Transplantation assays.” Box plots as above from n mice; P values as shown.

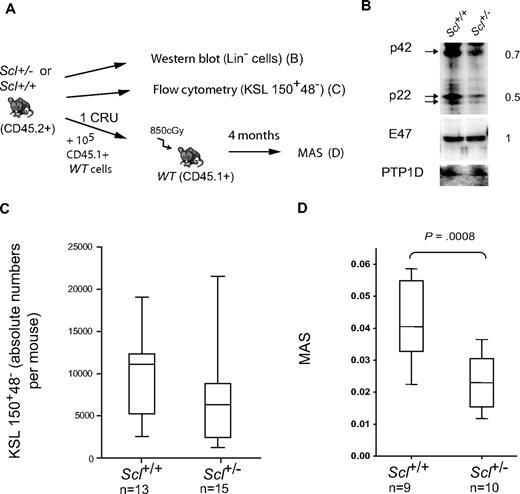

We therefore assessed their competitive advantage against HSCs from Scl+/+ littermates in competitive repopulation assays as well as serial transplantations. Scl+/− bone marrow cells (CD45.2+) were mixed with an equal number of wild-type competitor bone marrow cells (CD45.1+) and transplanted in congenic irradiated hosts (CD45.1+; Figure 3A). Because HSCs transplanted under limiting conditions undergo extensive proliferation, which in turn can lead to impaired stem cell function,2 we performed competitive repopulation assays at 2 doses of Scl+/− bone marrow cells: a limiting dose of 105 cells and a higher dose of 106 cells. Because HSC frequency derived by limiting dilution analysis was 1 of 22 000 for Scl+/− cells (supplemental Figure 2A) and the transplanted mixture was 45.7% CD45.2+, we estimated that mice were transplanted with Scl+/− cell equivalents of 4 CRU and 40 CRU, respectively. Reconstitution in the peripheral blood, bone marrow, and thymus was assessed 4 and 8 months after transplantation (Figure 3B-D), and the RCA of Scl+/− over Scl+/+ cells was calculated as described in “Transplantation assays.” At the limiting dose of 4 CRU, Scl+/− HSCs were severely impaired in their capacity to repopulate blood myeloid and lymphoid cells except B cells at 4 months (Figure 3B left panel), consistent with decreased MAS at approximately 1 CRU (Figure 2D). At the saturating dose of 40 CRU equivalent, this competitive disadvantage was manifest in mature blood (Figure 3B right panel) and bone marrow cells (not shown) at 8 months and was normal (RCA ∼ 1) at 4 months, as reported for a conditional Sclfl/− model.20 Thus, stem cell deficiency was readily detectable when transplanted at limiting dose, possibly because of extensive proliferation when the stem cell pool is limited.

Scl is required for HSC long-term competence. (A) Diagram of the serial competitive transplantation strategy. Scl+/− bone marrow cells (CD45.2+) were mixed with Scl+/+ competitor bone marrow cells (CD45.1+) at 1:1 or 1:5 ratio, and cells were transplanted in congenic irradiated hosts (CD45.1+) at 2 Scl+/− cell equivalents of 4 CRU or 40 CRU. (B-F) Data illustrate results for the 1:1 ratio at 4 CRU cell equivalents (B left panel) and 40 CRU cell equivalents (B-F). The RCA of Scl+/− cells was calculated and shown as the median ± SEM (*P ≤ .05). (B) Reconstitution by Scl+/− (CD45.2+) and Scl+/+ (CD45.2−) cells after the first transplantation at 4 or 40 CRU equivalents. Reconstitution at 4 and 8 months after transplantation was assessed by flow cytometric analysis of myeloid (CD11b, Gr1) and lymphoid (B220, CD3) cells in the peripheral blood. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments with groups of 5 or 7 mice each. Input Scl+/− cells before transplantation were 45.7% and 54.5%, respectively. (C-D) Analysis of populations enriched in stem cells and progenitors in the bone marrow. A representative analysis at 4 months of the KSL population is shown (C). The RCA of Scl+/− cells within the HSCs (Kit+Sca1+Lin−) population and myeloid (Kit+Sca1−Lin−IL7R−) as well as lymphoid (CLP) progenitor populations was assessed 4 and 8 months after transplantation (D) (**P ≤ .001). (E) Reconstitution by Scl+/− cells in the HSC population (KSL) and myeloid and as well as lymphoid progenitor populations (E left panel) or the mature myeloid and lymphoid populations (E right panel) 5 months after secondary transplantation. (F) Thymic reconstitution in primary and secondary transplantation within the CD4−CD8− (DN) and CD4+CD8+ (DP) populations is shown. Comparable results were observed with the CD4+ or CD8+ populations. All populations shown are Thy1+.

Scl is required for HSC long-term competence. (A) Diagram of the serial competitive transplantation strategy. Scl+/− bone marrow cells (CD45.2+) were mixed with Scl+/+ competitor bone marrow cells (CD45.1+) at 1:1 or 1:5 ratio, and cells were transplanted in congenic irradiated hosts (CD45.1+) at 2 Scl+/− cell equivalents of 4 CRU or 40 CRU. (B-F) Data illustrate results for the 1:1 ratio at 4 CRU cell equivalents (B left panel) and 40 CRU cell equivalents (B-F). The RCA of Scl+/− cells was calculated and shown as the median ± SEM (*P ≤ .05). (B) Reconstitution by Scl+/− (CD45.2+) and Scl+/+ (CD45.2−) cells after the first transplantation at 4 or 40 CRU equivalents. Reconstitution at 4 and 8 months after transplantation was assessed by flow cytometric analysis of myeloid (CD11b, Gr1) and lymphoid (B220, CD3) cells in the peripheral blood. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments with groups of 5 or 7 mice each. Input Scl+/− cells before transplantation were 45.7% and 54.5%, respectively. (C-D) Analysis of populations enriched in stem cells and progenitors in the bone marrow. A representative analysis at 4 months of the KSL population is shown (C). The RCA of Scl+/− cells within the HSCs (Kit+Sca1+Lin−) population and myeloid (Kit+Sca1−Lin−IL7R−) as well as lymphoid (CLP) progenitor populations was assessed 4 and 8 months after transplantation (D) (**P ≤ .001). (E) Reconstitution by Scl+/− cells in the HSC population (KSL) and myeloid and as well as lymphoid progenitor populations (E left panel) or the mature myeloid and lymphoid populations (E right panel) 5 months after secondary transplantation. (F) Thymic reconstitution in primary and secondary transplantation within the CD4−CD8− (DN) and CD4+CD8+ (DP) populations is shown. Comparable results were observed with the CD4+ or CD8+ populations. All populations shown are Thy1+.

Nonetheless, analysis of the KSL population in mice transplanted at high dose revealed that the contribution of Scl+/− cells was 2-fold decreased at 4 months (Figure 3C-D) and 10-fold decreased at 8 months (Figure 3D). These results indicate that Scl+/− cells are less competitive than Scl+/+ cells in reconstituting the stem cell pool. This competitive disadvantage was observed in IL7Rα− myeloid progenitors at both time points.

In contrast to the myeloid lineages, IL7Rα+ CLPs are slightly increased at 4 months and near-normal at 8 months (Figure 3D), consistent with a transient 2-fold increase in B cells in the peripheral blood followed by a normal contribution at 8 months when all other lineages are impaired (Figure 3B right panel). Because Scl is expressed at low levels in CLP (shown here)39 and in pro-B cells40 where SCL has been shown to inhibit E2A, Scl+/− cells might have a competitive advantage over Scl+/+ cells in the B lineage. Finally, thymic repopulation as illustrated here for the CD4−CD8− (double-negative [DN]) and CD4+CD8+ (double-positive [DP]) populations was transiently increased at 4 months and 5-fold impaired at 8 months (Figure 3F), consistent with decreased peripheral CD3+ T lymphocytes at this time point (Figure 3B).

In secondary transplantations assays, Scl+/− HSCs were severely impaired in their abilities to reconstitute secondary recipients in stem cell and progenitor populations (Figure 3E left panel) and in almost all mature lineages, except mature B cells (Figure 3E right panel).

Finally, we ruled out a possible non–cell-autonomous contribution to the phenotype of Scl+/− HSCs. Indeed, the capacity of HSCs to reconstitute hematopoiesis was similar when wild-type bone marrow cells were transplanted into Scl+/+ or Scl+/− irradiated mice (supplemental Figure 2B).

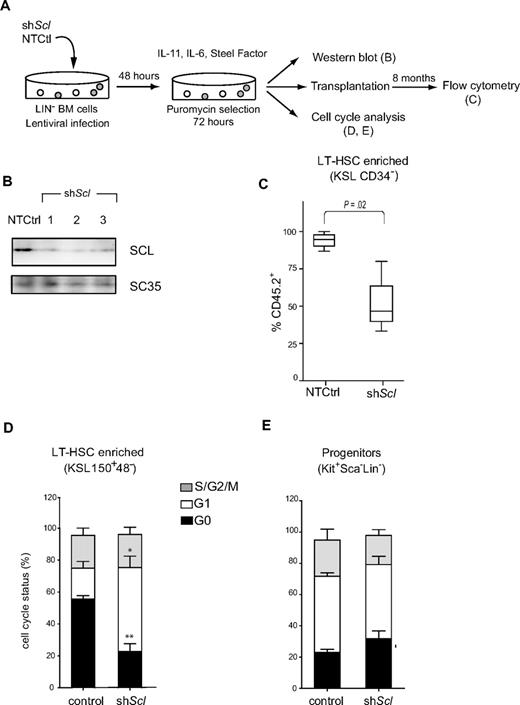

The above observations suggest that Scl levels regulate long-term HSC competence. Alternatively, it is possible that these stem cell defects arose during development. To address this question, we took an independent approach to decrease Scl levels in adult HSCs, based on the shRNA technology16 (Figure 4A). Three different Scl-directed shRNAs delivered by lentivirus efficiently knocked down protein levels in lineage-negative bone marrow cells as assessed by Western blotting, compared with control cells expressing a nontargeting control shRNA (Figure 4B). These cells were transplanted at 100 KSL 150+48− per mice. Long-term reconstitution in the bone marrow within the population of cells with an HSCs phenotype (KSL CD34−, Figure 4C; or KSL 150+48−, not shown) was on average 95% donor-derived in mice transplanted with control cells. This proportion was, however, 2-fold decreased by Scl shRNAs. We therefore conclude that Scl levels regulate the long-term maintenance of adult HSCs after transplantation.

Scl-directed shRNAs impair reconstitution in vivo and facilitate the G0-G1 transition of LT-HSCs in culture. (A) Schematic representation of shRNA lentiviral delivery in lineage-depleted bone marrow cells. Data shown are representative of 2 independent experiments. (B) Western blot of nuclear extracts from lineage-depleted bone marrow cells after the delivery of 3 different Scl-directed shRNAs or a nontargeting control. SC35 was used as loading control. (C) After gene delivery and puromycin selection, cells (CD45.2+) were transplanted into irradiated hosts (CD45.1+). The bone marrow was analyzed 8 months later for reconstitution (CD45.2+) within the HSC population (KSL CD34−). Box plots illustrate pooled data from control cells expressing the empty vector or a nontargeting shRNA (NTCtrl) or from cells expressing Scl-directed shRNAs illustrated in panel B (shScl). (D-E) Cell-cycle analyses of shRNA-infected cells were performed using Hoechst 33342 and Pyronin Y. Stacked columns represent the relative proportion of cells in G0, G1, and S/G2/M phases within the LT-HSCs (D) and progenitor populations (E). Data represent the mean ± SEM of pooled data for controls or shScl-expressing cells as in panel C (*P < .01, **P < .001).

Scl-directed shRNAs impair reconstitution in vivo and facilitate the G0-G1 transition of LT-HSCs in culture. (A) Schematic representation of shRNA lentiviral delivery in lineage-depleted bone marrow cells. Data shown are representative of 2 independent experiments. (B) Western blot of nuclear extracts from lineage-depleted bone marrow cells after the delivery of 3 different Scl-directed shRNAs or a nontargeting control. SC35 was used as loading control. (C) After gene delivery and puromycin selection, cells (CD45.2+) were transplanted into irradiated hosts (CD45.1+). The bone marrow was analyzed 8 months later for reconstitution (CD45.2+) within the HSC population (KSL CD34−). Box plots illustrate pooled data from control cells expressing the empty vector or a nontargeting shRNA (NTCtrl) or from cells expressing Scl-directed shRNAs illustrated in panel B (shScl). (D-E) Cell-cycle analyses of shRNA-infected cells were performed using Hoechst 33342 and Pyronin Y. Stacked columns represent the relative proportion of cells in G0, G1, and S/G2/M phases within the LT-HSCs (D) and progenitor populations (E). Data represent the mean ± SEM of pooled data for controls or shScl-expressing cells as in panel C (*P < .01, **P < .001).

SCL restrains the cell cycle in LT-HSCs

The long-term competence of stem cells has been linked to quiescence control.2,7 Furthermore, our observations indicate a correlation between Scl levels and quiescence (Figure 1). We therefore addressed the question of whether the cell-cycle status of LT-HSCs was affected by Scl RNA interference or reduced Scl gene dosage.

Analysis of cell-cycle parameters in the population enriched in LT-HSCs using Hoechst and Pyronin staining indicated that Scl shRNA infection resulted in a 3-fold increase in the G1 fraction (Figure 4D). The same effects were observed with 3 different shRNAs compared with a nontargeting control, suggesting that these were specifically the result of decreased SCL protein levels. Furthermore, populations that are enriched in hematopoietic progenitors (Kit+Sca−Lin−; Figure 4E) and mature cells (Lin+; supplemental Figure 3B) were not affected by shRNA exposure. Together, our observations indicate that SCL specifically hinders G0-G1 progression in LT-HSCs.

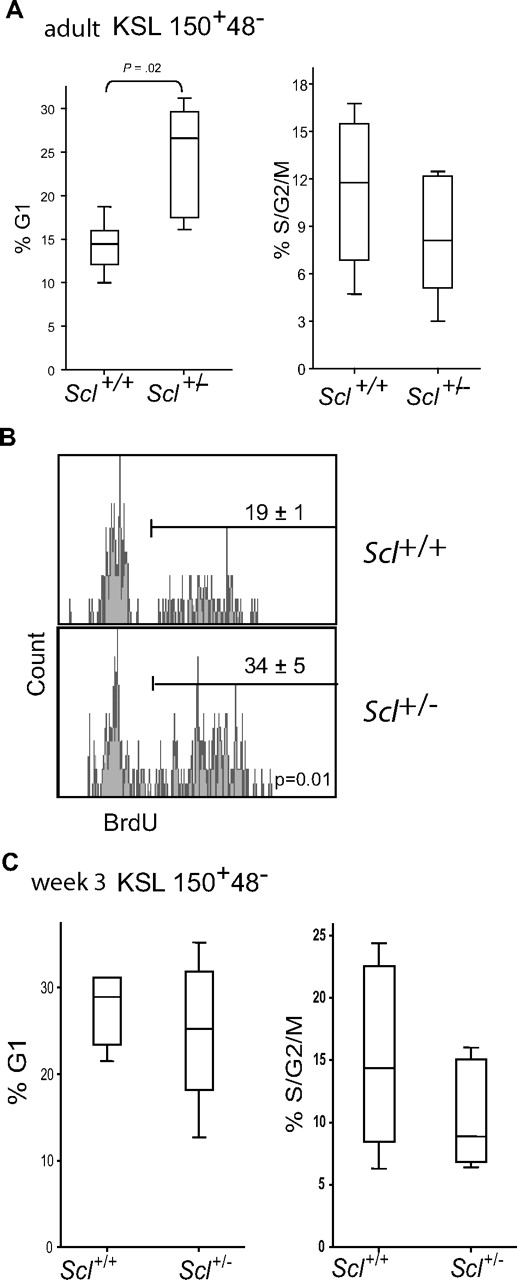

We next examined the cell-cycle status of LT-HSCs isolated from Scl+/− mice and found that reducing Scl gene dosage reproducibly increased by 2-fold the proportion of cells in G1 but not in S/G2/M (Figure 5A). To further evaluate the proportion of LT-HSCs that enter the cell cycle at steady state, we treated Scl+/+ and Scl+/− mice with BrdU for 3 days, a thymidine analog that incorporates into newly synthesized DNA. Whereas the estimated doubling time of individual HSCs is between 18 and 145 days, a 3-day treatment with BrdU appears to be sufficient to label LT-HSCs because BrdU is toxic for mature hematopoietic cells, causing an injury response that triggers dormant HSCs into proliferation.3 We found that the proportion of BrdU+ cells within the LT-HSC fraction was 19% in Scl+/+ mice, and this proportion was increased to 34% in Scl+/− mice (Figure 5B). Thus, Scl+/− LT-HSCs reproducibly exhibit a significant increase in the fraction of cells that undergo G0-G1 transition in vivo, either during steady state or in response to BrdU.

Scl gene dosage and the cell-cycle status of LT-HSCs. (A) The cell-cycle status of adult LT-HSCs was assessed within the Kit+Sca1+Lin−CD150+CD48− population by Hoechst 33342 and Pyronin Y staining. Box plots represent pooled data from 6 experiments with Scl+/+ and Scl+/− bone marrow cells at steady state, together with the medians and extreme values of the 2 distributions, illustrating the percentages of cells in G1 (left panel) and S-G2M (right panel). (B) BrdU incorporation in LT-HSCs was analyzed within the Kit+Sca1+Lin−CD150+CD48− population. Representative histograms are shown from Scl+/+ and Scl+/− bone marrows. Numbers shown are the mean ± SEM of 3 experiments. (C) The cell-cycle status of perinatal LT-HSCs (week 3) from Scl+/+ and Scl+/− bone marrows was assessed by flow cytometry, as in panel A. The 2 distributions do not differ significantly.

Scl gene dosage and the cell-cycle status of LT-HSCs. (A) The cell-cycle status of adult LT-HSCs was assessed within the Kit+Sca1+Lin−CD150+CD48− population by Hoechst 33342 and Pyronin Y staining. Box plots represent pooled data from 6 experiments with Scl+/+ and Scl+/− bone marrow cells at steady state, together with the medians and extreme values of the 2 distributions, illustrating the percentages of cells in G1 (left panel) and S-G2M (right panel). (B) BrdU incorporation in LT-HSCs was analyzed within the Kit+Sca1+Lin−CD150+CD48− population. Representative histograms are shown from Scl+/+ and Scl+/− bone marrows. Numbers shown are the mean ± SEM of 3 experiments. (C) The cell-cycle status of perinatal LT-HSCs (week 3) from Scl+/+ and Scl+/− bone marrows was assessed by flow cytometry, as in panel A. The 2 distributions do not differ significantly.

During development, HSCs are mostly nonquiescent and then at approximately week 4 after birth switch to a quiescent state, which persists throughout adult life.37 We therefore assessed the loss of one Scl allele on cell cycle in perinatal HSCs. Unlike adult HSCs, we found that half of perinatal HSCs are in G1/S/G2/M, and these are not significantly affected by Scl haploidy (Figure 5C). On week 4, however, these cells switch to the adult phenotype and their cycling state was affected by Scl gene dosage (not shown). Therefore, SCL does not control HSC cell cycle at the early postnatal stage. Consistent with this, Scl was shown to be more elevated in adult compared with fetal HSCs in 3 independent reports.25,37,41 Our observations indicate that SCL specifically controls LT-HSC quiescence in the adult.

In vitro cytokine stimulation triggers HSC proliferation and increases the proportion of cells in S/G2/M (Figure 6A-B). We therefore assessed the cell-cycle status of Scl+/− HSCs after 24 hours of cytokine stimulation and found a 2-fold increase in the G1 fraction compared with Scl+/+ HSCs, associated with a concomitant decrease in the G0 fraction. It is noteworthy that Scl+/− cells that were stimulated for 24 hours with cytokines (Figure 6B right panel) more closely resemble Scl knockdown cells (Figure 4D) that were exposed to cytokines for 5 days in culture because only 27% and 25% to 35% of KSL 150+48−, respectively, are in G0. Therefore, cell-cycle analysis at this early time point reveals that decreasing SCL levels facilitates the G0-G1 transition and cell-cycle progression when HSCs are stimulated by cytokine. In contrast, the cell-cycle state of adult progenitors (Kit+Sca1−Lin−) or mature cells (Lin+) was not significantly affected by Scl gene dosage (Figure 6C; supplemental Figure 3B), in good agreement with lower Scl expression level in these populations compared with HSCs (Figure 1C-D). Furthermore, we did not observe differences in cytokine-induced cell-cycle progression when Scl+/+ and Scl+/− LT-HSCs from 3-week-old mice were compared (Figure 6D). We therefore conclude that decreasing Scl gene dosage facilitates the G0-G1 transition in adult LT-HSCs in vivo and in vitro.

Scl gene dosage and LT-HSC cell cycle in response to cytokine stimulation. (A) Scl+/+ and Scl+/− lineage-depleted bone marrow cells harvested from adult mice were stimulated with Steel Factor, IL-11, and IL-6 for 24 hours before cell-cycle analysis. The percentages shown in each quadrant are the mean ± SEM of 3 experiments with representative contour plots. (B-C) Stacked columns represent the relative proportion of cells in G0, G1, and S-G2M within LT-HSCs (B) or progenitors (C) from Scl+/+ and Scl+/− mice (mean ± SEM of 3 experiments). The left panels represent cells at steady state before culture; the right panels represent growth factor (GF) stimulated cells after 24 hours in culture (*P = .02-.03; **P = .005). (D) Cell-cycle analysis of LT-HSCs from 3-week-old mice after 24 hours of cytokine stimulation. The percentages shown in each quadrant are the mean ± SEM of 3 experiments with representative contour plots.

Scl gene dosage and LT-HSC cell cycle in response to cytokine stimulation. (A) Scl+/+ and Scl+/− lineage-depleted bone marrow cells harvested from adult mice were stimulated with Steel Factor, IL-11, and IL-6 for 24 hours before cell-cycle analysis. The percentages shown in each quadrant are the mean ± SEM of 3 experiments with representative contour plots. (B-C) Stacked columns represent the relative proportion of cells in G0, G1, and S-G2M within LT-HSCs (B) or progenitors (C) from Scl+/+ and Scl+/− mice (mean ± SEM of 3 experiments). The left panels represent cells at steady state before culture; the right panels represent growth factor (GF) stimulated cells after 24 hours in culture (*P = .02-.03; **P = .005). (D) Cell-cycle analysis of LT-HSCs from 3-week-old mice after 24 hours of cytokine stimulation. The percentages shown in each quadrant are the mean ± SEM of 3 experiments with representative contour plots.

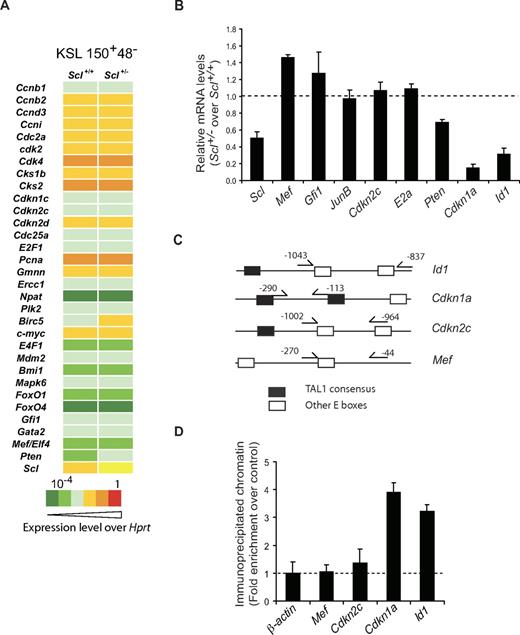

SCL controls Cdkn1a and Id1 gene expression in HSCs

We next assessed whether SCL levels affect the expression levels of known cell-cycle genes and stem cell regulators in purified KSL 150+48− populations. By PCR array (Figure 7A), we observed that most genes were not affected in Scl+/− cells compared with Scl+/+ cells, except for the Scl mRNAs, which were 2-fold decreased as expected. Pten mRNA levels were also decreased. We therefore measured by quantitative RT-PCR the expression levels of genes that are known to control HSCs quiescence: transcription factors encoding genes, ie, Mef, Gfi1, JunB, E2a, and Id1, as well as CDK inhibitor genes, ie, Cdkn2c (p18Ink4c) and Cdkn1a (p21waf1/cip), and Pten.8-10,12,13,43,44 In purified LT-HSCs (Figure 7B), Mef, Gfi1, E2a, and JunB as well as Cdkn2c expression levels were not significantly affected by decreased Scl gene dosage, suggesting that these genes are not downstream of Scl. In contrast, Cdkn1a and Id1 were reproducibly decreased by 10- and 3-fold, respectively, whereas Pten showed a more modest decrease. Sequence analysis of the Id1, Cdkn1a, and Cdkn2c proximal promoters reveals the presence of consensus E box binding sites for the E47-SCL heterodimer42 (supplemental Figure 4A), whereas Mef proximal promoter contains nonconsensus E boxes. We designed PCR primers in the vicinity of these E boxes (Figure 7C) for chromatin immunoprecipitation of purified Lin− cells. Cdkn1a and Id1 promoter sequences were specifically immunoprecipitated by the SCL antibody compared with control immunoglobulins, whereas Mef promoter sequences and β-actin control sequences were not (Figure 7D). Despite the presence of a potential TAL1 binding site in the Cdkn2c promoter, SCL binding was below the limit of detection of the assay, possibly because the sequence is of lower affinity (CAGTTG42 ) or because of an unfavorable context. These results indicate that the SCL protein specifically occupies the Cdkn1a and Id1 loci in immature hematopoietic cells. Finally, we show that the SCL complex up-regulates the Cdkn1a minimal promoter, whereas E2A has little activity on its own (supplemental Figure 4B). We therefore conclude that the Cdkn1a and Id1 genes are direct SCL targets and their expression is sensitive to Scl gene dosage.

Cdkn1a and Id1 are direct target genes of SCL in immature hematopoietic cells. (A) Cells with an LT-HSC phenotype were purified by flow cytometry from Scl+/+ and Scl+/− bone marrows. After reverse transcription, gene expression was assessed by quantitative PCR array for the indicated cell cycle–related genes and stem cell genes. Data shown are representative of 2 independent experiments. (B) Gene expression in LT-HSCs from Scl+/+ and Scl+/− bone marrows was determined by quantitative RT-PCR. mRNA levels of the indicated genes were first normalized using Hprt as an internal control and second compared with expression levels in the Scl+/+ LT-HSC population, which was set as 1 (illustrated here as the dotted line; mean ± SD of 4 replicates after normalization; 2 experiments). (C) Diagram illustrating the positions of primers used for ChIP in panel D for the indicated murine genes. Note the presence of E boxes in the vicinity of the primers. Black box represents TAL1 E boxes (supplemental Figure 4A)42 ; open box, other E boxes. (D) Chromatin extracts from lineage-depleted bone marrow cells were immunoprecipitated with an anti-murine SCL antibody or species-matched IgG (control, shown as dotted line). Immunoprecipitated promoter sequences were analyzed by quantitative PCR (mean ± SD of 4 replicates; 2 experiments). β-actin downstream sequences serve as negative controls for PCR amplification.

Cdkn1a and Id1 are direct target genes of SCL in immature hematopoietic cells. (A) Cells with an LT-HSC phenotype were purified by flow cytometry from Scl+/+ and Scl+/− bone marrows. After reverse transcription, gene expression was assessed by quantitative PCR array for the indicated cell cycle–related genes and stem cell genes. Data shown are representative of 2 independent experiments. (B) Gene expression in LT-HSCs from Scl+/+ and Scl+/− bone marrows was determined by quantitative RT-PCR. mRNA levels of the indicated genes were first normalized using Hprt as an internal control and second compared with expression levels in the Scl+/+ LT-HSC population, which was set as 1 (illustrated here as the dotted line; mean ± SD of 4 replicates after normalization; 2 experiments). (C) Diagram illustrating the positions of primers used for ChIP in panel D for the indicated murine genes. Note the presence of E boxes in the vicinity of the primers. Black box represents TAL1 E boxes (supplemental Figure 4A)42 ; open box, other E boxes. (D) Chromatin extracts from lineage-depleted bone marrow cells were immunoprecipitated with an anti-murine SCL antibody or species-matched IgG (control, shown as dotted line). Immunoprecipitated promoter sequences were analyzed by quantitative PCR (mean ± SD of 4 replicates; 2 experiments). β-actin downstream sequences serve as negative controls for PCR amplification.

Discussion

In the present study, we show that SCL controls HSC long-term competence and restrains the G0-G1 transition in these cells. Furthermore, SCL directly regulates the expression of 2 genes involved in HSCs quiescence, Id1 and the cell-cycle regulator Cdkn1a.

SCL regulates the G0-G1 progression of LT-HSCs

Using a highly purified population of LT-HSCs, we show that Scl expression is higher in cells with an LT-HSC phenotype compared with ST-HSCs and progenitors. This might appear to differ from data reported in human cells, in which SCL was shown to be lower in the most primitive CD34+CD38− cells compared with CD34+CD38+ cells.39 However, markers are not yet available to purify human HSCs to the same degree as the murine KSL 150+48− because the CD34+CD38− population in human contains SCID-repopulating cells at a frequency of 1 of 617 only.45

When cells with an LT-HSC phenotype were further purified into G0 and G1/S fractions, we found that Scl and Cdkn1a expression is higher in purified G0 cells. Furthermore, a 2-fold decrease in SCL protein levels, caused by either Scl haplodeficiency or RNA interference, is revealed by a facilitation of G0/G1 progression in vivo or in vitro in LT-HSCs without affecting non–stem cell populations. Together, these observations suggest that high Scl levels in murine LT-HSCs maintain these cells in quiescence during steady state. This activity of SCL was more prominent when LT-HSCs were stimulated with cytokines in vitro, or triggered into cycling by BrdU administration in vivo. Furthermore, reducing Scl gene dosage also impairs HSC long-term competitive potential as discussed in the next section.

SCL controls HSCs function under proliferative stress

In the adult, HSCs must achieve a balance between quiescence and rapid cell-cycle entry on conditions of high proliferative demand, to fulfill immediate requirements for mature hematopoietic cells without compromising the maintenance of the stem cell pool. HSCs that are normally quiescent are triggered into cycle after transplantation in vivo6 as these cells expand and occupy the bone marrow niche in irradiated hosts.46 Our studies uncover an important role for SCL when HSCs are subject to an intense proliferative demand, ie, when transplanted under limiting conditions (∼1-5 CRU per mouse) or in long-term transplantation assays.

Despite the proliferation imposed by transplantation, Scl+/− HSCs transplanted at saturating doses did not exhibit detectable functional deficits when reconstitution was assessed with lineage markers 4 months after transplantation, in good agreement with published results.20,21,47 However, when transplanted at limiting doses, Scl+/− HSCs show on average a 4-fold competitive disadvantage, possibly caused by extensive proliferation. Furthermore, when reconstitution was assessed at 4 months in the primitive Kit+Sca1+Lin− population or at 8 months in lineage-positive cells, Scl+/− cells were 2- to 5-fold less competitive than Scl+/+ HSCs. This stem cell deficit also carries through in secondary transplantations. Although HSC doubling time after transplantation has not been clearly established, our observations are consistent with the possibility that adult HSCs divide infrequently, perhaps every 145 days,3,48 unless forced into proliferation by transplantation at a limiting dose of CRU. We therefore propose that our assay conditions may reveal haploinsufficiency in other stem cell regulators.

Quiescence and self-renewal

An essential hallmark of LT-HSCs is their capacity for sustained self-renewal. Indeed, ST-HSCs are also capable of undergoing self-renewal divisions but are unable to maintain hematopoiesis in the long-term. Sustainability is therefore a true stem cell characteristic. Self-renewal divisions can lead to expansion, as observed during ontogeny when the stem pool increases in size, or to maintenance in the adult, preserving HSC numbers and functions throughout the entire life span of the organism. Very few transcriptional regulators are known to be involved in this long-term maintenance, and our observations indicate an important role for Scl gene dosage in this process.

During development, the dramatic expansion of HSCs in the fetal liver is associated with a high cycling state,37,49 controlled in part by Sox17.50 Between week 3 and 4 after birth, HSCs then switch from this proliferative state to a quiescence state, associated with an increase in Scl and Gata-2 expression.25,37,41 It remains to be determined whether these genes control the fetal-to-adult switch, although our analysis of perinatal HSCs indicates that Scl does not control their cell-cycle state. Contrary to the proliferative state of fetal HSCs, the increased cell cycle within the adult LT-HSC population in Scl+/− mice is not associated with expansion but with accelerated exhaustion of the stem cell pool as discussed underneath.

Stemness in many systems is associated with a low cycling state and long-term activity.2,51 For example, HSC defects caused by Id1 deficiency9,52 are reminiscent of those observed here with Scl deficiency. ID proteins heterodimerize with bHLH factors and prevent their DNA binding capacity. ID1, however, does not heterodimerize with SCL53 and therefore is unlikely to inhibit SCL activity. Rather, ID19,52 and SCL (the present study) have comparable functional impacts on HSC cell cycle and long-term competence. Furthermore, we show that the Id1 gene is a direct target of SCL in LT-HSCs. There are nonetheless some differences, as Scl+/− HSCs do not exhibit accelerated differentiation, as reported for Id1−/− HSCs. This difference is currently unresolved but could be the result of the 30% residual levels of Id1 in Scl+/− cells or to the contribution of other SCL target genes, such as Cdkn1a. Alternatively, SCL is part of a subfamily of bHLH transcription factors that includes LYL154 and TAL2,22 which may compensate for decreased Scl gene dosage in HSCs.

Cdkn1a deficiency is also associated with an early exhaustion of the stem cell pool,8 and we show here that Cdkn1a is a direct SCL target gene in Lin− cells. Transcription activation by SCL depends on its capacity to nucleate a multiprotein complex on DNA.17 Depending on the context, the same target gene can be activated or repressed by SCL.55 In the absence of appropriate partners as in the lymphoid lineages, ectopic SCL expression inhibits E-protein activity31,40,55 and the expression of E2A target genes, such as Cdkn1a.56 However, in the presence of appropriate SCL partners as in erythroid cells, ie, E2A, LMO2, LDB1, and GATA proteins, SCL activates transcription17,57 and enhances Cdkn1a expression.16 Our results indicate that, in LT-HSCs, SCL enhances Cdkn1a expression, suggesting the presence of appropriate SCL partners in these cells.

Similar to Scl and Id1 deficiency, HSCs from Egr1−/−,58 Pten−/−,43 Foxo1−/−, 3−/−, and 4−/−59,60 mice also exhibit increased cell cycle and defective maintenance of the HSC pool. Contrary to the above, Mef facilitates G1 progression and Mef deletion is associated with enhanced HSC function.12 Therefore, quiescence and long-term HSC function appear to be controlled by the same transcriptional network. In this circuitry, our observations are consistent with the view that Scl acts in parallel to or downstream of Gfi1, Foxo3 and 4, and Mef and upstream of Id1, Cdkn1a, and possibly Pten to actively maintain HSCs in G0, restrain G1 progression, and sustain long-term HSC competence. One possible mechanism linking quiescence control and long-term HSCs maintenance involves the regulation of early G1, a sensitive period of the cell cycle during which HSCs could potentially either be exposed to stimuli that cause an early exhaustion,2 or exhibit decreased marrow homing capacity.46,58 Together, these observations suggest that HSC quiescence preserves HSC activity3 and enhances HSC self-renewal.2

In conclusion, we show that Scl gene dosage restricts G1 entry in dormant HSCs and preserves HSC activity under conditions of proliferative demand.

An Inside Blood analysis of this article appears at the front of this issue.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Richard Martin for help with the colony replating experiment, Danièle Gagné for flow cytometry, Pierre Chagnon for the quantitative PCR array, and Véronique Mercille and Véronique Litalien for the mouse colony.

This work was supported in part by the Canadian Cancer Society Research Institute (T.H., G.S., N.N.I.), the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (T.H., G.S.), the Cancer Research Society Inc (T.H.), the Canadian Research Chair program (T.H., G.S.), and by Fonds de la Recherche en Santé du Québec (studentship) (J.L.) and the Cole foundation (studentship) (S.R.-S., S.B.). The infrastructure is supported in part by the Institute of Research in Immunology and Cancer (Fonds de la Recherche en Santé du Québec group grant).

Authorship

Contribution: J.L. and S.H. performed the research, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper; S.R.-S., S.B., and A.H. performed the research, analyzed the data, and revised the manuscript; N.N.I. and G.S. participated in designing the research and revised the manuscript; and T.H. designed the research, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Trang Hoang, University of Montreal, PO Box 6128, Downtown Station, Montreal, QC H3C 2J7, Canada; e-mail: trang.hoang@umontreal.ca.

References

Author notes

J.L. and S.H. contributed equally to this study.