Abstract

c-Maf is one of the large Maf (musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma) transcription factors that belong to the activated protein-1 super family of basic leucine zipper proteins. Despite its overexpression in hematologic malignancies, the physiologic roles c-Maf plays in normal hematopoiesis have been largely unexplored. On a C57BL/6J background, c-Maf−/− embryos succumbed from severe erythropenia between embryonic day (E) 15 and E18. Flow cytometric analysis of fetal liver cells showed that the mature erythroid compartments were significantly reduced in c-Maf−/− embryos compared with c-Maf+/+ littermates. Interestingly, the CFU assay indicated there was no significant difference between c-Maf+/+ and c-Maf−/− fetal liver cells in erythroid colony counts. This result indicated that impaired definitive erythropoiesis in c-Maf−/− embryos is because of a non–cell-autonomous effect, suggesting a defective erythropoietic microenvironment in the fetal liver. As expected, the number of erythroblasts surrounding the macrophages in erythroblastic islands was significantly reduced in c-Maf−/− embryos. Moreover, decreased expression of VCAM-1 was observed in c-Maf−/− fetal liver macrophages. In conclusion, these results strongly suggest that c-Maf is crucial for definitive erythropoiesis in fetal liver, playing an important role in macrophages that constitute erythroblastic islands.

Introduction

In mouse embryogenesis, red blood cells are produced in the yolk sac in a process called primitive erythropoiesis. Erythropoiesis then takes place in the fetal liver around embryonic day (E) 10 onward and in BM and spleen after birth. This process, which is characterized by enucleated red blood cells, is called definitive erythropoiesis.1 During terminal erythroid differentiation, erythroblasts are associated with a central macrophage, which forms a specialized microenvironment, the so-called erythroblastic islands. In the erythroblastic islands, a central macrophage provides favorable proliferative and survival signals to the surrounding erythroblasts, and it eventually engulfs the extruded nuclei of maturing erythrocytes.2-5 Inhibition of the interaction between macrophage and erythroblasts usually leads to embryonic anemia accompanied by accelerated apoptosis of erythroid cells. Targeted disruption of the gene palld, which encodes actin cytoskeleton associated protein (palladin) prevented effective erythroblast-macrophage interactions because of differentiation defects in the macrophage. Therefore, mouse embryos homozygous for the mutant gene experience severe anemia and succumb in the embryonic period.6 Meanwhile, it has been reported that a series of adhesion molecules are also involved in the process of forming erythroblastic islands. Erythroblast macrophage protein (EMP) is a transmembrane protein expressed in both erythroblasts and macrophages, and it mediates the erythroblast-macrophage interaction. Indeed, the targeted deletion of EMP causes lethal anemia in mouse embryos because of the suppressed formation of erythroblastic islands.7 Furthermore, a previous report showed that the interaction between very late Ag-4 (α4β1 integrin) on erythroblasts and VCAM-1 on macrophages plays a key role in maintaining the islands.8 For example, administration of Abs raised against either α4β1 integrin or VCAM-1 caused disruption of the island structure.8 However, the molecular mechanism, in terms of transcriptional regulation of island-affiliated genes in macrophages, remains largely unknown.

The large Maf transcription factor c-Maf is a cellular homolog of v-maf, which was isolated from a chicken musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma induced by avian retrovirus AS42 infection.9 The large Maf transcription factors contain an acidic domain that promotes transcriptional regulation and a basic region/leucine zipper domain that mediates dimerization, as well as DNA binding to either Maf recognition elements (MAREs) or the 5′ AT-rich half-MARE.10-12 Each large Maf protein has been shown to play a distinct role in cellular proliferation and differentiation in both pathologic and physiologic situations.9,13-19 In B-lymphoid and T-lymphoid lineages, aberrant expression of c-Maf works as an oncogene, as shown in patients with multiple myeloma and angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma and in a transgenic mouse model.20-23 Physiologic c-Maf expression is indispensable for the proper regulation of IL-4 and IL-21 gene expression in T-helper cells.24,25 In macrophages, c-Maf has been reported to regulate IL-10 expression, which is essential for differentiation of regulatory T cells.26 In addition, combined deficiency of MafB and c-Maf enables long-term expansion of differentiated, mature macrophages.27 We recently reported that c-Maf is abundantly expressed in fetal liver macrophages and that it regulates expression of F4/80, which mediates immune tolerance.28 However, the physiologic consequences of c-Maf deletion on terminal erythroid differentiation in erythroblastic islands have been largely unexplored.

In the present study, we demonstrate that c-Maf–deficient mice exhibit embryonic anemia, which is associated with a failure to retain erythroblastic islands. Moreover, we found significantly reduced expression of VCAM-1 in c-Maf–deficient macrophages, which presumably accounts for the deficiency in island maintenance and subsequent embryonic anemia. Thus, these results suggest that c-Maf is indispensable for definitive erythropoiesis in fetal liver, because it activates VCAM-1 expression in macrophages, and this causes the maintenance of erythroblastic islands.

Methods

Mice

c-Maf–deficient mice were originally generated on a 129/Sv background14 and have been backcrossed onto a C57BL/6J background for > 7 generations. In staging the embryos, gestational day 0.5 (E0.5) was defined as noon of the day a vaginal plug was found after overnight mating. Mice were maintained in specific pathogen-free conditions in a Laboratory Animal Resource Center. All experiments were performed according to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals at the University of Tsukuba.

Hematologic analysis of fetal liver cells, embryonic blood, and adult blood

Single-cell suspensions prepared from fetal livers were washed and resuspended in 1 mL of 2% FBS/PBS. The cell number was counted with the use of a hemocytometer. Collection of embryonic peripheral blood was performed as described previously.29 Peripheral blood samples from adult mice were obtained from retro-orbital venous plexus with the use of heparin-coated microtubes. Blood counts were determined with an automated hemocytometer (Nihon Kohden). Blood smears were prepared with the wedge technique and were stained with May-Grünwald-Giemsa and then photographed with a Keyence Biorevo BZ-9000 microscope. Images were processed with Photoshop software (Adobe).

Flow cytometry

Freshly isolated fetal liver cells were immunostained at 4°C in PBS/2% FBS in the presence of 5% mouse serum to block Fc receptors. Cells were incubated with FITC-conjugated anti–TER-119 and allophycocyanin (APC)–conjugated anti-CD44 Abs, followed by a 5-minute incubation with phycoerythrin PE-conjugated Annexin V (BioVision) at room temperature. To quantify the presence of VCAM-1 and integrin αV on macrophages, FITC-conjugated anti–Mac-1, Alexa Fluor 647–conjugated anti–VCAM-1 and PE-conjugated anti-integrin αV Abs were used for analyses. All Abs except PE-conjugated annexin V were from eBioscience. Flow cytometry was performed on a Becton Dickinson FACS LSR with CellQuest software. The isolation of erythroblasts at different stages of maturation was performed as described previously.30 Data were analyzed with FlowJo (Tree Star Inc) analysis software.

Cell cycle analysis

Cell cycle analysis was performed with propidium iodide (PI). Further details are provided in supplemental Methods (available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

Histology and TUNEL assay

Whole E13.5 embryos were fixed in 10% formalin neutral buffer solution (Wako). Paraffin-embedded tissue was sectioned, mounted, and stained with H&E. TUNEL assays were performed with an in situ Apoptosis Detection Kit according to the manufacturer's protocol (TaKaRa). Images were captured by a digital camera system with the use of a Leica DM RXA2 microscope (Leica Microsystems).

CFU assay

CFU assays were performed in MethoCult GF M3434 (StemCell Technologies) for erythroid burst-forming unit (BFU-E) and granulocyte, erythroid, megakaryocyte, and macrophage CFU (CFU-GEMM), and M3334 for erythroid CFU (CFU-E), following the manufacturer's instructions. CFU-E was scored 2 days after plating. BFU-E and CFU-GEMM were scored 8 days after plating.

Preparation of “native” erythroblastic islands and “reconstituted” erythroblastic islands

Native erythroblastic islands were isolated from fetal livers with the use of a previously described protocol.31 Full details are provided in supplemental Methods.

Microarray analysis of fetal liver macrophages

Real-time RT-PCR analysis of fetal liver macrophages

Macrophages were prepared from fetal livers of c-Maf+/+ or c-Maf−/− mice. Separation of fetal liver macrophages with the use of Mac-1+ magnetic beads and the MACS system was performed as described previously.28 RNA extraction and quantitative RT-PCR were performed as described previously.28 Primers used for PCR and the PCR conditions are available in supplemental Table 1.

Luciferase reporter assay

The VCAM-1 0.7 kilobase (kb) promoter (VCAM-1 Luc) or VCAM-1 mut Luc ligated to a luciferase reporter33 was transiently cotransfected with c-Maf expression plasmids in macrophage cell line J774 with the use of FuGENE 6 (Roche). Twenty-four hours after the transfection, cells were collected, and reporter gene assays were performed with the Dual Luciferase Kit (Promega). Transfection efficiency was normalized to the expression of Renilla luciferase.

Reconstitution of hematopoietic system with fetal liver cells

The donor cells for hematopoietic reconstitution were prepared from E14.5 fetal livers of c-Maf+/+ or c-Maf−/− (C57BL/6J-Ly5.1) mice. Fetal liver cells (2 × 106 cells) were injected into the tail vein of 8- to 10-week-old C57BL/6J-Ly5.2 mice that were previously exposed to x-rays at a 10-Gy dose.

Phenylhydrazine stress test

Mice were injected subcutaneously on days 0, 1, and 3 with 50 mg/kg phenylhydrazine (PHZ) hydrochloride solution in PBS as previously described.34 Blood was obtained from the retro-orbital plexus on days 0, 3, 6, 8, and 10.

Statistical analysis

Data were represented as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance between any 2 groups was determined by the 2-tailed Student t test, in which P values < .05 were considered significant.

Results

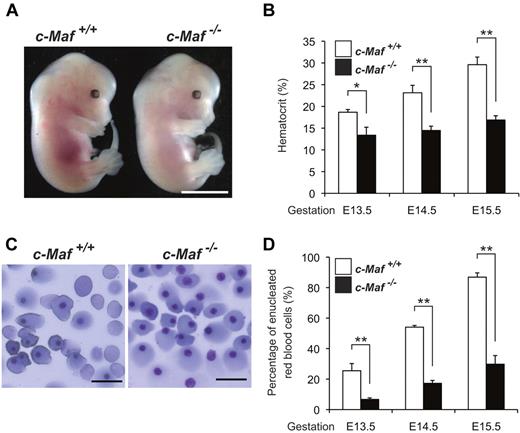

Lethal erythropoietic deficiency in c-Maf−/− embryos

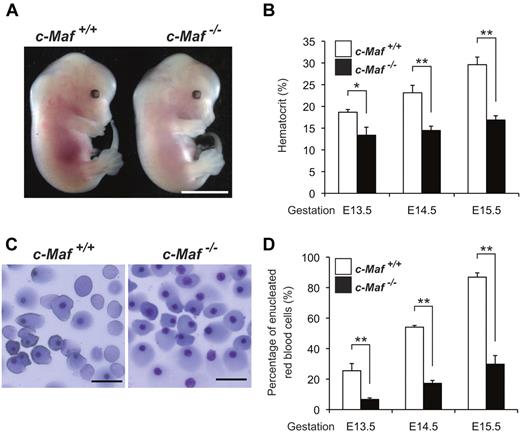

The c-Maf−/− mice, as originally generated, exhibited perinatal mortality within a few hours after birth on a 129/Sv background.14 However, unexpectedly, on a C57BL/6J genetic background, c-Maf deficiency resulted in embryonic lethality from E15.5 onward, and almost all c-Maf−/− embryos died before E18.5 (Table 1). The fetal livers from c-Maf−/− embryos at E13.5 appeared pale compared with those from healthy c-Maf+/+ control embryos (Figure 1A). As expected, the hematocrits of peripheral blood in the c-Maf−/− embryos (E13.5∼E15.5) were markedly reduced (E13.5. 13.4% ± 1.8%; E14.5, 14.5% ± 1.0%; E15.5, 16.9% ± 1.0%), compared with the c-Maf+/+ controls (E13.5, 18.7% ± 0.6%; E14.5, 23.1% ± 1.7%; E15.5, 29.6% ± 1.8%; Figure 1B). May-Grünwald-Giemsa staining of peripheral blood smears showed a significant reduction of enucleated red blood cells in c-Maf−/− embryos (E13.5, 6.68% ± 1.0%; E14.5, 17.2% ± 1.9%; E15.5, 29.8% ± 5.6%; Figure 1C-D), whereas c-Maf+/+ control embryos retained a normal population of enucleated red blood cells (E13.5, 25.5% ± 4.7%; E14.5, 54.1% ± 1.1%; E15.5, 86.9% ± 2.8%; Figure 1C-D). Considering that the enucleated red blood cells are mainly derived from definitive erythropoiesis, these data suggest that c-Maf–deficient embryos suffer from impaired definitive erythropoiesis on the C57BL/6J genetic background. A previous study showed that placental insufficiency causes embryonic lethality.35 To assess the effect of c-Maf on the placenta, immunofluorescence staining of placenta was performed with an anti–c-Maf Ab (supplemental Figure 1B). The expression of c-Maf was not detected in placenta. Compared with the head tissue as a positive control, c-Maf mRNA expression was 5-fold less in the placenta (supplemental Figure 1C). In addition, no obvious abnormalities in the c-Maf−/− placenta were observed after H&E staining (supplemental Figure 1D).

c-Maf−/− embryos are anemic. (A) Gross appearance of E13.5 embryos. The c-Maf−/− embryo is paler and smaller than its c-Maf+/+ littermate. Scale bar represents 5 mm. The picture was taken with a NIKON coolpix 5200 digital camera in macro mode and processed with the Adobe Photoshop CS4 software. (B) Hematocrit values for c-Maf+/+ (n = 6) and c-Maf−/− (n = 6) embryos at E13.5, c-Maf+/+ (n = 8) and c-Maf−/− (n = 7) embryos at E14.5, and c-Maf+/+ (n = 12) and c-Maf−/− (n = 9) embryos at E15.5. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. The mean hematocrit values for c-Maf−/− embryos were significantly lower than values for c-Maf+/+ at E13.5, E14.5, and E15.5. (C) Blood smears from E13.5 embryos stained with May-Grünwald-Giemsa stain. The blood smear from a c-Maf−/− embryo contains far fewer enucleated red blood cells. Images were acquired by a Biorevo BZ microscope (Plan Apo 20×0.75 DIC N2) at room temperature and processed with the Adobe Photoshop CS4 software. Scale bars represent 20 μm. (D) The percentage of enucleated red blood cells in peripheral blood for c-Maf+/+ (n = 5) and c-Maf−/− (n = 7) embryos at E13.5, c-Maf+/+ (n = 4) and c-Maf−/− (n = 4) embryos at E14.5, and c-Maf+/+ (n = 8) and c-Maf−/− (n = 8) embryos at E15.5. A minimum of 200 cells was counted for each sample. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. The percentage of enucleated red blood cells is significantly reduced in c-Maf−/− embryos than in c-Maf+/+ embryos at E13.5, E14.5, and E15.5. *P < .05 and **P < .01.

c-Maf−/− embryos are anemic. (A) Gross appearance of E13.5 embryos. The c-Maf−/− embryo is paler and smaller than its c-Maf+/+ littermate. Scale bar represents 5 mm. The picture was taken with a NIKON coolpix 5200 digital camera in macro mode and processed with the Adobe Photoshop CS4 software. (B) Hematocrit values for c-Maf+/+ (n = 6) and c-Maf−/− (n = 6) embryos at E13.5, c-Maf+/+ (n = 8) and c-Maf−/− (n = 7) embryos at E14.5, and c-Maf+/+ (n = 12) and c-Maf−/− (n = 9) embryos at E15.5. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. The mean hematocrit values for c-Maf−/− embryos were significantly lower than values for c-Maf+/+ at E13.5, E14.5, and E15.5. (C) Blood smears from E13.5 embryos stained with May-Grünwald-Giemsa stain. The blood smear from a c-Maf−/− embryo contains far fewer enucleated red blood cells. Images were acquired by a Biorevo BZ microscope (Plan Apo 20×0.75 DIC N2) at room temperature and processed with the Adobe Photoshop CS4 software. Scale bars represent 20 μm. (D) The percentage of enucleated red blood cells in peripheral blood for c-Maf+/+ (n = 5) and c-Maf−/− (n = 7) embryos at E13.5, c-Maf+/+ (n = 4) and c-Maf−/− (n = 4) embryos at E14.5, and c-Maf+/+ (n = 8) and c-Maf−/− (n = 8) embryos at E15.5. A minimum of 200 cells was counted for each sample. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. The percentage of enucleated red blood cells is significantly reduced in c-Maf−/− embryos than in c-Maf+/+ embryos at E13.5, E14.5, and E15.5. *P < .05 and **P < .01.

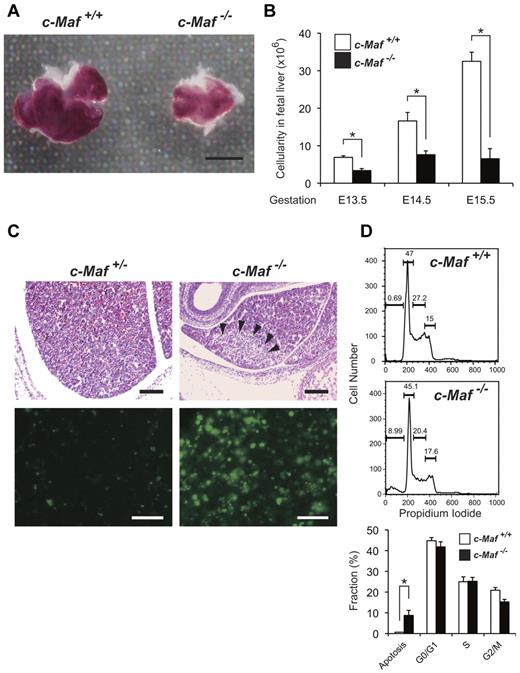

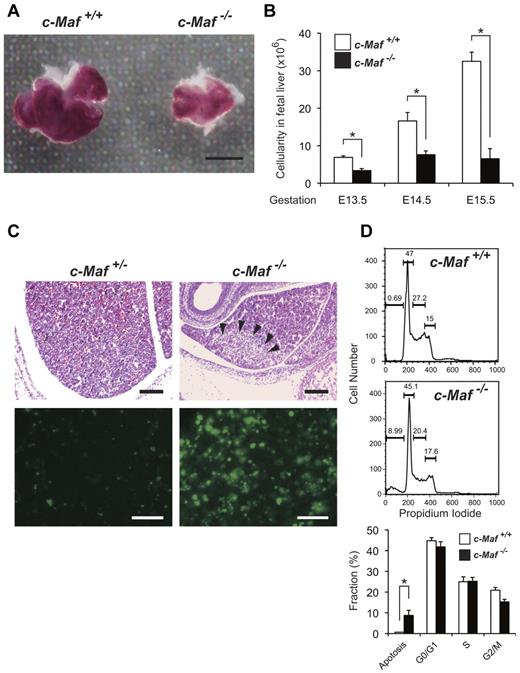

Increased apoptotic cell death in c-Maf−/− fetal liver

We next examined the cellular viability, as well as the cell cycle status, of c-Maf−/− fetal liver cells, in the hope of elucidating the molecular and cellular basis of their erythropoietic deficiency. The fetal liver size in c-Maf−/− embryos was smaller; thus, consistently fewer fetal liver cells were harvested from c-Maf−/− embryos between E13.5 and E15.5 (E13.5, 3.37 ± 0.5 × 106 cells; E14.5, 7.61 ± 1.0 × 106 cells; E15.5, 6.54 ± 2.7 × 106 cells) than from age-matched c-Maf+/+ control embryos (E13.5, 6.89 ± 0.4 × 106 cells; E14.5, 16.6 ± 2.3 × 106 cells; E15.5, 32.5 ± 2.4 × 106 cells; Figure 2A-B). Of note, H&E staining of E13.5 c-Maf−/− fetal liver sections showed an increased number of pyknotic nuclei, which are indicative of apoptosis, compared with the c-Maf+/− control embryo (Figure 2C). In addition, TUNEL-positive apoptotic cells were remarkably increased in E13.5 c-Maf−/− fetal liver sections (Figure 2C). Moreover, flow cytometric analysis of PI-stained fetal liver cells showed an increased abundance of a sub-G0/G1 population early apoptotic cell fraction in c-Maf−/− fetal liver (8.77% ± 2.5%) compared with c-Maf+/+ control cells (0.67% ± 0.01%; Figure 2D). However, the cellular population of each phase of the cell cycle, that is, G0/G1, S, and G2/M, was not significantly affected (Figure 2D). Overall, these observations suggest that the fetal liver hematopoietic cells from c-Maf−/− embryos are prone to undergo apoptotic cell death.

Increased number of apoptotic cells is observed in c-Maf−/− fetal liver. (A) Gross appearance of E13.5 fetal liver. The c-Maf−/− fetal liver is smaller than a c-Maf+/+ fetal liver. Scale bar represents 100 μm. The picture was taken with a NIKON coolpix 5200 digital camera in macro mode and processed with the Adobe Photoshop CS4 software.(B) The mean total number of fetal liver cells in c-Maf+/+ (n = 14) and c-Maf−/− (n = 10) embryos at E13.5, c-Maf+/+ (n = 6) and c-Maf−/− (n = 4) embryos at E14.5, and c-Maf+/+ (n = 8) and c-Maf−/− (n = 8) embryos at E15.5. The mean number of fetal liver cells is significantly reduced in c-Maf−/− embryos. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. (C) H&D staining of c-Maf+/− and c-Maf−/− fetal liver sections (top). Arrowheads indicate pyknotic nuclei, which indicate apoptotic cells. TUNEL assays showed increased apoptosis in the c-Maf−/− fetal liver (bottom panel). Images were acquired by a Leica DM RXA2 microscope (Lecia HC PL Fluotar 20×/0.50 PH2) at room temperature and processed with the Adobe Photoshop CS4 software. Scale bars in the top panel represent 200 μm. Scale bars in the bottom panel represent 50 μm. (D) The fraction of cells in different phases of the cell cycle was measured by PI staining followed by flow cytometric analyses. The percentage of cells in sub-G0/G1, G1, S phase, and G2/M are indicated. The sub-G0/G1 phase represents the apoptotic population. The apoptotic population was increased in c-Maf−/− fetal liver.

Increased number of apoptotic cells is observed in c-Maf−/− fetal liver. (A) Gross appearance of E13.5 fetal liver. The c-Maf−/− fetal liver is smaller than a c-Maf+/+ fetal liver. Scale bar represents 100 μm. The picture was taken with a NIKON coolpix 5200 digital camera in macro mode and processed with the Adobe Photoshop CS4 software.(B) The mean total number of fetal liver cells in c-Maf+/+ (n = 14) and c-Maf−/− (n = 10) embryos at E13.5, c-Maf+/+ (n = 6) and c-Maf−/− (n = 4) embryos at E14.5, and c-Maf+/+ (n = 8) and c-Maf−/− (n = 8) embryos at E15.5. The mean number of fetal liver cells is significantly reduced in c-Maf−/− embryos. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. (C) H&D staining of c-Maf+/− and c-Maf−/− fetal liver sections (top). Arrowheads indicate pyknotic nuclei, which indicate apoptotic cells. TUNEL assays showed increased apoptosis in the c-Maf−/− fetal liver (bottom panel). Images were acquired by a Leica DM RXA2 microscope (Lecia HC PL Fluotar 20×/0.50 PH2) at room temperature and processed with the Adobe Photoshop CS4 software. Scale bars in the top panel represent 200 μm. Scale bars in the bottom panel represent 50 μm. (D) The fraction of cells in different phases of the cell cycle was measured by PI staining followed by flow cytometric analyses. The percentage of cells in sub-G0/G1, G1, S phase, and G2/M are indicated. The sub-G0/G1 phase represents the apoptotic population. The apoptotic population was increased in c-Maf−/− fetal liver.

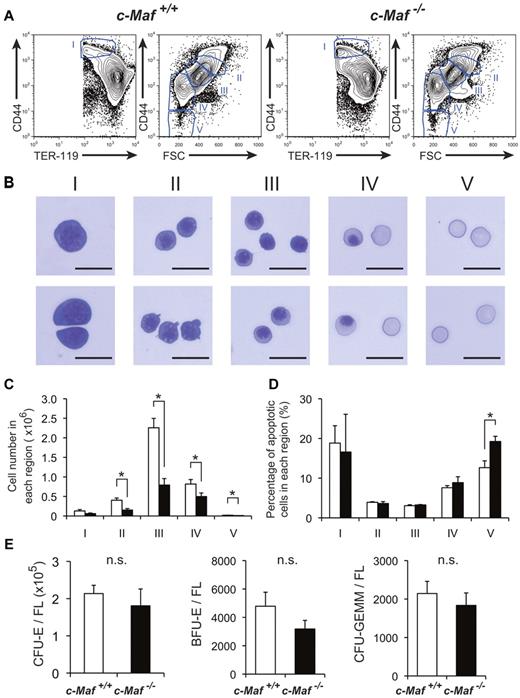

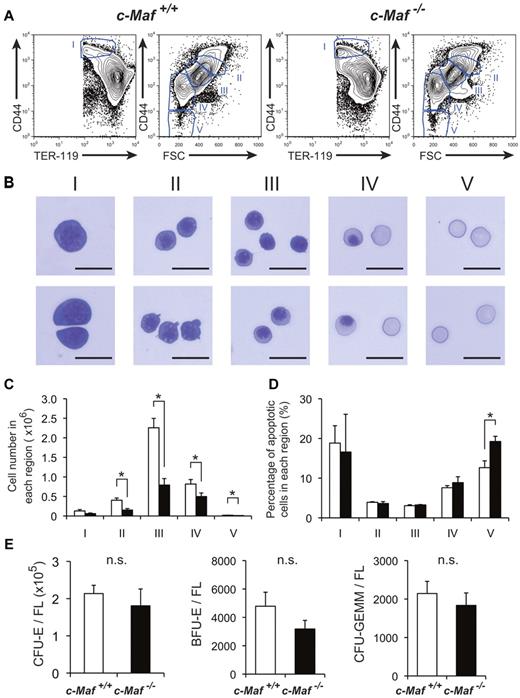

Impaired fetal liver erythropoiesis because of a non–cell-autonomous effect of c-Maf deficiency

Given the significant disturbance of erythropoiesis, we next attempted to delineate the maturation status of erythroid lineage cells in c-Maf−/− fetal liver. To this end, we examined fetal liver erythropoiesis by flow cytometry with the use of the erythroid markers CD44 and TER-119, which distinguish various stages of erythroid-cell differentiation (Figure 3A). By modifying a method reported by Chen et al30 to isolate erythroblasts at different maturation stages from adult BM, we isolated erythroblasts from fetal liver cells and analyzed their structure (Figure 3B). Decreased numbers of mature erythroid compartments (regions II, III, IV, and V in Figure 3C) were observed in c-Maf−/− fetal liver than in c-Maf+/+ fetal liver. These results showed a reduction of basophilic erythroblasts, polychromatic erythroblasts, orthochromatic erythroblasts, reticulocytes, and mature red cells in c-Maf−/− fetal liver. Previously, Zhang et al36 reported a method to study erythropoiesis with the use of an anti-CD71 Ab and an anti–TER-119 Ab. Similar results were obtained with their method. Decreased numbers of mature erythroid compartments (region 3 to region 5 in supplemental Figure 2A-B) were observed in c-Maf−/− fetal liver in combination with anti-CD71 Ab and anti–TER-119 Ab. These observations prompted us to quantify the apoptotic cell population at each stage of erythroid cells by annexin V staining.

Definitive erythropoiesis in fetal liver is impaired in c-Maf−/− embryos but c-Maf−/− fetal liver cells can form erythroid colonies. (A) Flow cytometric analysis of fetal liver cells isolated from E13.5 embryos labeled with a FITC-conjugated anti–TER-119 mAb and an APC-conjugated anti-CD44 mAb. Regions I to V are defined by a characteristic staining pattern and forward scatter (FSC) intensity of cells as indicated. (B) Representative images of erythroblast structure on stained cytospins from the 5 distinct regions shown in Figure 3A of wild-type fetal liver. Images were acquired by a Biorevo BZ microscope (Plan Apo 20×0.75 DIC N2) at room temperature and processed with the Adobe Photoshop CS4 software. Scale bar represents 20 μm. (C) Comparison of c-Maf+/+ and c-Maf−/− fetal livers in region I to region V. □ represents c-Maf+/+; ■, c-Maf−/−; n = 8∼10 per group; *P < .05. (D) The ratio of annexin V+ cells from region I to region V was compared in c-Maf+/+ and c-Maf−/− fetal livers. □ represents c-Maf+/+; ■, c-Maf−/−; n = 3 per group; *P < .05. (E) In vitro colony assay with the use of fetal liver cells from c-Maf+/+ (□) and c-Maf−/− (■) embryos at E13.5. A total of 20 000 fetal liver cells were plated and cultured with methylcellulose media. The numbers of CFU-E–, BFU-E–, and CFU-GEMM–derived colonies per fetal liver are shown. No significant difference (n.s.) was found in the number of CFU-E–, BFU-E–, or CFU-GEMM–derived colonies per fetal liver in c-Maf+/+ embryos and c-Maf−/− embryos; n = 6∼7 per group; data are presented as mean ± SEM. FL indicates fetal liver.

Definitive erythropoiesis in fetal liver is impaired in c-Maf−/− embryos but c-Maf−/− fetal liver cells can form erythroid colonies. (A) Flow cytometric analysis of fetal liver cells isolated from E13.5 embryos labeled with a FITC-conjugated anti–TER-119 mAb and an APC-conjugated anti-CD44 mAb. Regions I to V are defined by a characteristic staining pattern and forward scatter (FSC) intensity of cells as indicated. (B) Representative images of erythroblast structure on stained cytospins from the 5 distinct regions shown in Figure 3A of wild-type fetal liver. Images were acquired by a Biorevo BZ microscope (Plan Apo 20×0.75 DIC N2) at room temperature and processed with the Adobe Photoshop CS4 software. Scale bar represents 20 μm. (C) Comparison of c-Maf+/+ and c-Maf−/− fetal livers in region I to region V. □ represents c-Maf+/+; ■, c-Maf−/−; n = 8∼10 per group; *P < .05. (D) The ratio of annexin V+ cells from region I to region V was compared in c-Maf+/+ and c-Maf−/− fetal livers. □ represents c-Maf+/+; ■, c-Maf−/−; n = 3 per group; *P < .05. (E) In vitro colony assay with the use of fetal liver cells from c-Maf+/+ (□) and c-Maf−/− (■) embryos at E13.5. A total of 20 000 fetal liver cells were plated and cultured with methylcellulose media. The numbers of CFU-E–, BFU-E–, and CFU-GEMM–derived colonies per fetal liver are shown. No significant difference (n.s.) was found in the number of CFU-E–, BFU-E–, or CFU-GEMM–derived colonies per fetal liver in c-Maf+/+ embryos and c-Maf−/− embryos; n = 6∼7 per group; data are presented as mean ± SEM. FL indicates fetal liver.

In good agreement with the preferential decrease of the mature erythroid compartments (regions II-V), we observed a highly increased number of annexin V-positive cells in the most mature erythroid compartment (region V) of c-Maf−/− fetal liver compared with the c-Maf+/+ fetal liver. In contrast, the premature erythroid compartments (regions I-IV) of c-Maf−/− fetal liver cells exhibited a comparable number of annexin V-positive cells with the c-Maf+/+ control (Figure 3D; supplemental Figure 2C). To examine the state of globin regulation, the Mac-1− cells from E13.5 fetal liver were sorted and analyzed for mRNA of Hbb (hemoglobin beta chain) genes by real-time RT-PCR analysis. Expression profiles showing switching of Hbb genes indicated that the definitive Hbb gene Hbb-b1 (hemoglobin, beta adult major chain) was significantly down-regulated, whereas the primitive globin genes Hbb-bH1 (hemoglobin z, beta-like embryonic chain) and Hbb-y (hemoglobin y, beta-like embroyonic chain) were not significantly suppressed in the c-Maf−/− fetal liver erythroid fraction compared with the c-Maf+/+ control (supplemental Figure 3).

To examine the colony formation potential of hematopoietic progenitors in c-Maf−/− fetal liver, conventional set of CFU assays were performed. As a result of CFU assays, there were no significant differences between c-Maf+/+ and c-Maf−/− in the number of CFU-E–, BFU-E–, and CFU-GEMM–derived colonies per fetal liver (Figure 3E). In addition, CFU-E colonies were indistinguishable in structure and size (supplemental Figure 4A-B). Moreover, erythroid cells derived from c-Maf−/− CFU-Es exhibited a similar structure, and enucleated red blood cells were also similar to those from c-Maf+/+ control CFU-Es in cytospin slides stained with May-Grünwald-Giemsa (supplemental Figure 4C). Taken together, these results suggest that c-Maf−/− erythroid cells are still capable of developing into mature cells in vitro, in contrast to the result of flow cytometric analysis with the use of fetal liver cells (Figures 3A-C; supplemental Figure 2A-B), which reflects the in vivo condition. Therefore, the impaired definitive erythropoiesis in the c-Maf−/− embryos is more likely because of a non–cell-autonomous effect of c-Maf deficiency.

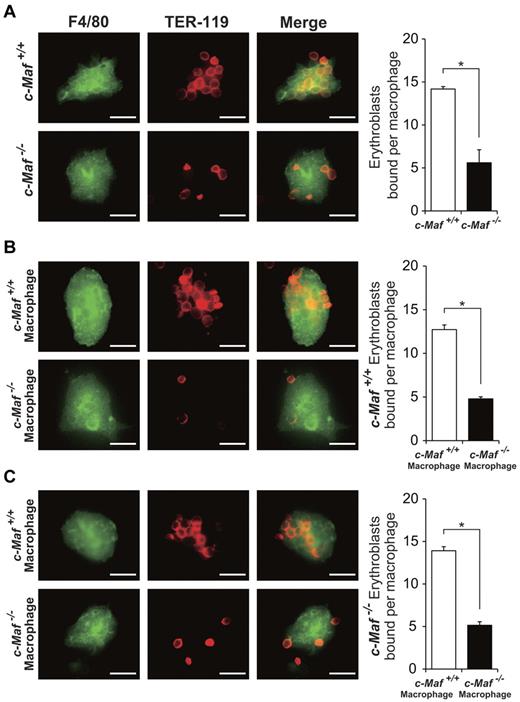

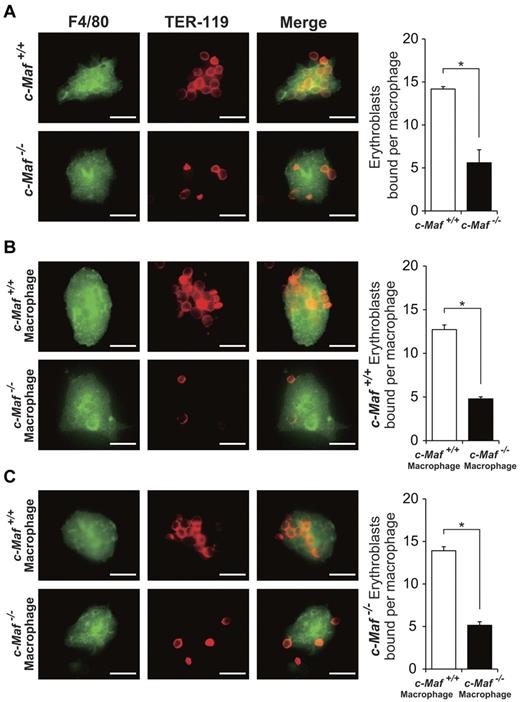

Absence of c-Maf causes impaired erythroblastic island formation in the fetal liver

c-Maf is abundantly expressed in fetal liver macrophages, although it is largely missing from the erythroid cells in fetal liver. Therefore, we initially surmised that c-Maf deficiency in fetal liver macrophages disturbed the erythroblastic islands.3 To address this hypothesis, we attempted to examine whether c-Maf−/− macrophages failed to maintain the erythroblastic islands. For this purpose, we isolated the erythroblastic island from c-Maf+/+ and c-Maf−/− fetal livers and counted the number of erythroblasts associated with each single central macrophage according to a previously described method.31

Interestingly, although > 10 TER-119+ erythroblasts were adhered to a F4/80+ macrophage in c-Maf+/+ fetal livers, c-Maf–deficient central macrophages seemed to harbor far fewer erythroblasts (Figure 4). As shown in Figure 4A, the number of erythroblasts attached to a single central macrophage was significantly reduced in c-Maf−/− erythroblastic islands (14.2 ± 0.3 and 5.6 ± 1.5 erythroblasts per macrophage for c-Maf+/+ and c-Maf−/−, respectively). This result clearly indicates that erythroblastic islands are impaired in the c-Maf−/− fetal livers.

Absence of c-Maf impairs the formation of erythroblastic islands in the fetal liver. (A) Native erythroblastic islands isolated from c-Maf+/+ and c-Maf−/− fetal liver were immunostained with F4/80 (green) and TER-119 (red) Abs as described in “Methods.” F4/80 is used as a macrophage-specific marker, and TER-119 is used as a marker for erythroblasts. The number of erythroblasts surrounding each macrophage was significantly reduced in c-Maf−/− fetal liver. (B) Erythroblastic islands reconstituted with c-Maf+/+ erythroblasts were immunostained. The number of c-Maf+/+ erythroblasts surrounding each c-Maf+/+ or c-Maf−/− macrophage is shown. c-Maf+/+ erythroblasts surrounding c-Maf−/− macrophages were significantly reduced compared with those seen for c-Maf+/+ macrophages. (C) Erythroblastic islands reconstituted with c-Maf−/− erythroblasts were immunostained. The number of c-Maf−/− erythroblasts surrounding each c-Maf+/+ or c-Maf−/− macrophage is shown. c-Maf−/− erythroblasts surrounding c-Maf−/− macrophage were significantly reduced compared with those seen for c-Maf+/+ macrophages. Although c-Maf−/− erythroblasts can form reconstituted erythroblastic islands with c-Maf+/+ macrophages, c-Maf−/− macrophages showed impaired formation of reconstituted erythroblastic islands with c-Maf+/+ erythroblasts. Images were acquired by a Biorevo BZ microscope (Plan Apo 20×0.75 DIC N2) at room temperature and processed with the Adobe Photoshop CS4 software. The scale bar represents 20 μm; n = 4∼6 embryos per group. For each combination, ≥ 20 macrophages per embryo were analyzed. *P < .05. Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

Absence of c-Maf impairs the formation of erythroblastic islands in the fetal liver. (A) Native erythroblastic islands isolated from c-Maf+/+ and c-Maf−/− fetal liver were immunostained with F4/80 (green) and TER-119 (red) Abs as described in “Methods.” F4/80 is used as a macrophage-specific marker, and TER-119 is used as a marker for erythroblasts. The number of erythroblasts surrounding each macrophage was significantly reduced in c-Maf−/− fetal liver. (B) Erythroblastic islands reconstituted with c-Maf+/+ erythroblasts were immunostained. The number of c-Maf+/+ erythroblasts surrounding each c-Maf+/+ or c-Maf−/− macrophage is shown. c-Maf+/+ erythroblasts surrounding c-Maf−/− macrophages were significantly reduced compared with those seen for c-Maf+/+ macrophages. (C) Erythroblastic islands reconstituted with c-Maf−/− erythroblasts were immunostained. The number of c-Maf−/− erythroblasts surrounding each c-Maf+/+ or c-Maf−/− macrophage is shown. c-Maf−/− erythroblasts surrounding c-Maf−/− macrophage were significantly reduced compared with those seen for c-Maf+/+ macrophages. Although c-Maf−/− erythroblasts can form reconstituted erythroblastic islands with c-Maf+/+ macrophages, c-Maf−/− macrophages showed impaired formation of reconstituted erythroblastic islands with c-Maf+/+ erythroblasts. Images were acquired by a Biorevo BZ microscope (Plan Apo 20×0.75 DIC N2) at room temperature and processed with the Adobe Photoshop CS4 software. The scale bar represents 20 μm; n = 4∼6 embryos per group. For each combination, ≥ 20 macrophages per embryo were analyzed. *P < .05. Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

Next, to address whether c-Maf deficiency in macrophages was specifically responsible for the impairment of erythroblastic islands, a series of reconstitution experiments was performed. After attaching native erythroblastic islands either from c-Maf+/+ or c-Maf−/− fetal livers on a glass coverslip, the adherent erythroblasts in the islands were stripped from the macrophages. Next, the freshly isolated erythroblasts from c-Maf+/+ or c-Maf−/− fetal livers were cocultured on the remaining adherent c-Maf+/+ or c-Maf−/− fetal liver macrophages, respectively, so that c-Maf+/+ erythroblasts were cocultured on c-Maf−/− central macrophages and vice versa. Surprisingly, c-Maf−/− macrophages failed to support erythroblastic islands with the inoculated wild-type erythroblasts (12.7 ± 0.5 erythroblasts per c-Maf+/+ macrophage and 4.8 ± 0.2 erythroblasts per c-Maf−/− macrophage; Figure 4B). In contrast, c-Maf−/− erythroblasts were still capable of attaching to c-Maf+/+ macrophages to the same extent as wild-type erythroblasts (13.9 ± 0.5 erythroblasts per c-Maf+/+ macrophage and 5.1 ± 0.4 erythroblasts per c-Maf−/− macrophage; Figure 4C). These results show that the erythropoietic defects in c-Maf−/− embryos could be induced by an impaired hematopoietic microenvironment. Most probably, the suppressed functions of c-Maf–deficient central macrophages were responsible for the damaged erythroblastic islands.

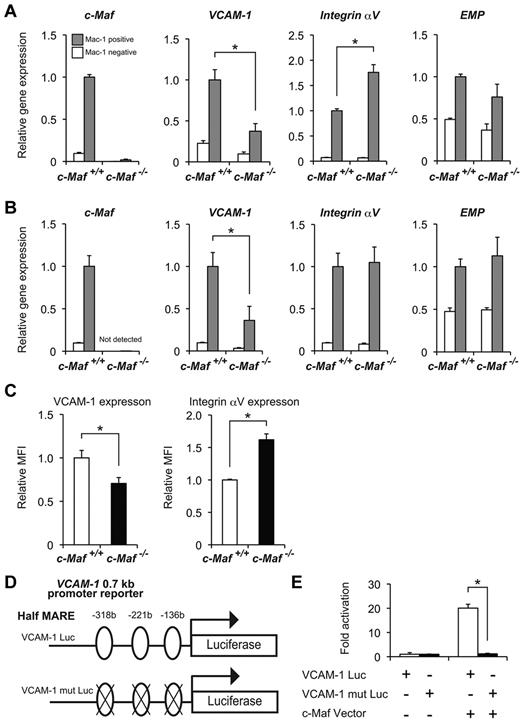

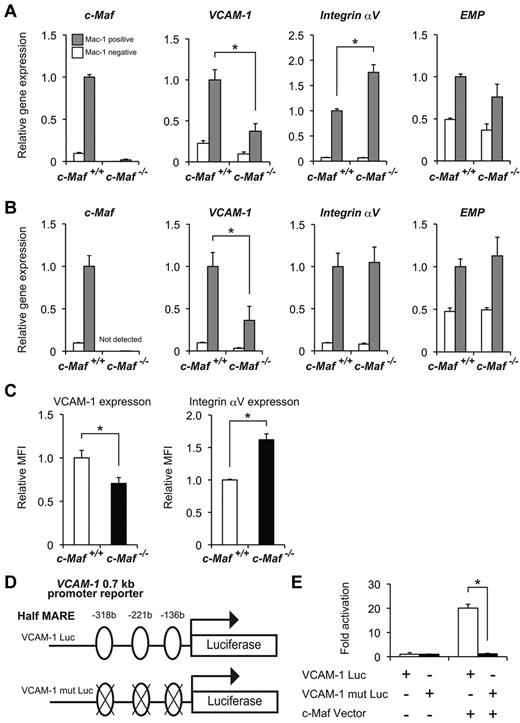

Identification of target genes of c-Maf in fetal liver macrophages

To identify the molecular targets by which c-Maf regulates formation of erythroblastic islands in macrophages, we monitored the expression of cell adhesion molecules by microarray analysis. The expression of several important adhesion molecules was decreased in c-Maf−/− macrophages (Table 2). Expression of VCAM-1 was suppressed the furthest in these molecules. To confirm the results from microarray analysis, we performed quantitative RT-PCR analyses, examining expression levels of VCAM-1, Integrin αV, and EMP. These are essential for erythroblastic island formation and maintenance and are thus designated as erythroblast-macrophage adhesive molecules.3 The Mac-1+ cells from either E13.5 or E14.5 fetal liver were sorted and analyzed to determine the mRNA abundance of these genes by real-time RT-PCR analysis. Of note, we observed an ∼ 2.5-fold reduction in the VCAM-1 mRNA expression level in the Mac-1+ fraction from c-Maf−/− fetal liver, compared with the c-Maf+/+ control at E13.5 and E14.5 (Figure 5A-B). However, EMP mRNA expression was not reduced in c-Maf−/− compared with c-Maf+/+ (Figure 5A-B). In addition, expression of Integrin αV at E13.5 in c-Maf−/− was significantly up-regulated. Consistent with this observation, flow cytometric analysis of the fetal liver cells at E13.5 also verified a significant reduction of VCAM-1 protein expression in the c-Maf−/− fetal liver Mac-1+ cells compared with the c-Maf+/+ fetal liver Mac-1+ cells, and protein expression of Integrin αV in the c-Maf−/− fetal liver Mac-1+ cells was higher than that in c-Maf+/+ (Figure 5C).

Decreased expression of VCAM-1 in c-Maf−/− fetal liver macrophage. mRNA expression profiles of erythroblast-macrophage adhesive interaction genes at E13.5 (A) and at E14.5 (B). Total RNA obtained from the Mac-1+ fraction (gray bar) and Mac-1− fraction (open bar) of fetal liver cells was used for analyses. VCAM-1 expression was decreased in c-Maf−/− macrophages at E13.5 and E14.5; n = 7 per group; *P < .05. The expression level of c-Maf+/+ fetal liver Mac-1 fraction was set to 1.0. All of the data are presented as mean ± SEM (C) Relative mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) values of VCAM-1 and Integrin αV for the c-Maf+/+ fetal liver Mac-1 fraction (normalized to MFI = 1) and the c-Maf−/− fetal liver Mac-1 fraction. E13.5 fetal liver cells were stained with FITC-conjugated anti–Mac-1 mAb, APC-conjugated anti–VCAM-1 mAb, and PE-conjugated anti-Integrin αV mAb. Bar graphs represent mean ratio ± SEM. Consistent with real-time RT-PCR analysis, significant differences in VCAM-1 and Integrin αV protein expression were observed; n = 8 per group; *P < .05. (D) Schematic diagram of a luciferase reporter construct with the use of a VCAM-1 0.7-kb promoter (VCAM-1 Luc, top) ligated to a firefly luciferase cassette. Three putative half-MARE sites (5′ −318 bp, −221 bp, and −136 bp) are indicated. A luciferase assay was performed with a VCAM-1 Luc and that with mutations in half-MARE (VCAM-1 mut Luc, bottom) as reporters. (E) The pEFX3-FLAG-cMaf expression vector (c-Maf Vector) was cotransfected with the reporter plasmid into the macrophage cell line J774. The relative luciferase activity shown is derived from averages of 2 independent experiments (shown as mean ± SEM). The luciferase activity seen in J774 cells transfected with the reporter plasmid and with an empty vector was normalized to a value of 1 as the standard (*P < .05).

Decreased expression of VCAM-1 in c-Maf−/− fetal liver macrophage. mRNA expression profiles of erythroblast-macrophage adhesive interaction genes at E13.5 (A) and at E14.5 (B). Total RNA obtained from the Mac-1+ fraction (gray bar) and Mac-1− fraction (open bar) of fetal liver cells was used for analyses. VCAM-1 expression was decreased in c-Maf−/− macrophages at E13.5 and E14.5; n = 7 per group; *P < .05. The expression level of c-Maf+/+ fetal liver Mac-1 fraction was set to 1.0. All of the data are presented as mean ± SEM (C) Relative mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) values of VCAM-1 and Integrin αV for the c-Maf+/+ fetal liver Mac-1 fraction (normalized to MFI = 1) and the c-Maf−/− fetal liver Mac-1 fraction. E13.5 fetal liver cells were stained with FITC-conjugated anti–Mac-1 mAb, APC-conjugated anti–VCAM-1 mAb, and PE-conjugated anti-Integrin αV mAb. Bar graphs represent mean ratio ± SEM. Consistent with real-time RT-PCR analysis, significant differences in VCAM-1 and Integrin αV protein expression were observed; n = 8 per group; *P < .05. (D) Schematic diagram of a luciferase reporter construct with the use of a VCAM-1 0.7-kb promoter (VCAM-1 Luc, top) ligated to a firefly luciferase cassette. Three putative half-MARE sites (5′ −318 bp, −221 bp, and −136 bp) are indicated. A luciferase assay was performed with a VCAM-1 Luc and that with mutations in half-MARE (VCAM-1 mut Luc, bottom) as reporters. (E) The pEFX3-FLAG-cMaf expression vector (c-Maf Vector) was cotransfected with the reporter plasmid into the macrophage cell line J774. The relative luciferase activity shown is derived from averages of 2 independent experiments (shown as mean ± SEM). The luciferase activity seen in J774 cells transfected with the reporter plasmid and with an empty vector was normalized to a value of 1 as the standard (*P < .05).

Given the significant suppression of VCAM-1 expression in c-Maf−/− fetal liver macrophages, we next addressed whether c-Maf could activate the VCAM-1 gene promoter. To this end, a luciferase reporter assay in the J774 macrophage cell line was performed with a plasmid containing the 0.7-kb VCAM-1 promoter region (VCAM-1 Luc) as a reporter (Figure 5D). The luciferase activity was significantly increased when the reporter plasmid was cotransfected with an expression plasmid for c-Maf. In contrast, when putative half-MARE sequences were mutated (VCAM-1 mut Luc), activation of the reporter was blunted (Figure 5E). These results indicate that c-Maf regulates the expression of VCAM-1 by binding the putative half-MARE sites in its promoter region.

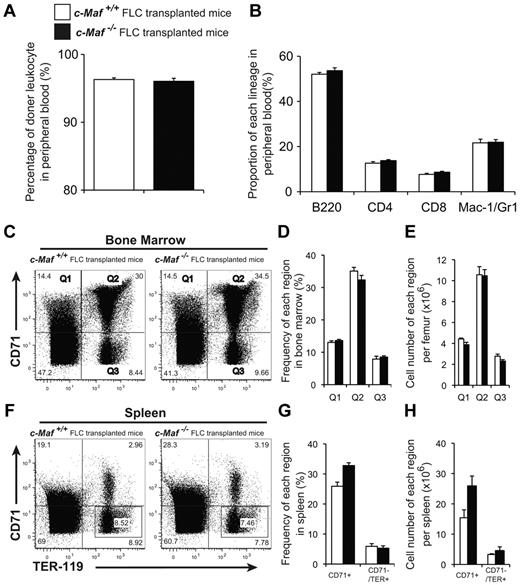

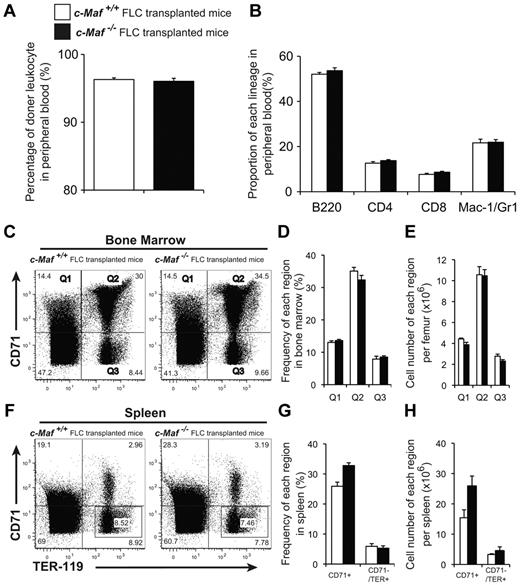

c-Maf–deficient fetal liver cells are capable of reconstituting the hematopoietic system of adult mice

To determine whether c-Maf−/− embryos still retain functional hematopoietic stem cells, we tested the ability of c-Maf–deficient fetal liver cells to reconstitute the hematopoietic system of lethally irradiated recipient mice. Fetal liver cells collected from E14.5 c-Maf+/+ or c-Maf−/− embryos were injected into lethally irradiated recipient mice. All recipients receiving both c-Maf+/+ and c-Maf−/− fetal liver cells survived and remained healthy for ≥ 6 months after transplantation. The donor-derived leukocyte chimerism in the mice reconstituted with c-Maf−/− fetal liver cells was comparable with that of the recipient mice with control fetal liver cells (Figure 6A). Moreover, there were no significant differences in hematocrit or proportion (%) of B220+, CD4+, CD8+, or Mac-1+/Gr1+ cells between the recipients receiving c-Maf+/+ or c-Maf−/− fetal liver cells (Table 3; Figure 6B).

c-Maf−/− fetal liver cells can reconstitute adult hematopoiesis in lethally irradiated mice. (A) Eight to 10 weeks after transplantation, the donor leukocyte chimerism of the mice reconstituted with c-Maf−/− fetal liver cells was comparable to that of the mice reconstituted with c-Maf+/+ fetal liver cells. The reconstitution efficiency was checked by flow cytometry with the use of the Ly5.1/Ly5.2 ratio of peripheral blood cells. Donor chimerism was determined to be as follows: (%Ly5.1+/%Ly5.1+ + %Ly5.2+) × 100. (B) No significant difference was found in the proportion of each lineage in peripheral blood between c-Maf+/+ fetal liver cells transplanted into mice and c-Maf−/− fetal liver cells transplanted into mice. (C) Flow cytometric analyses of the TER-119 and CD71 expression in total BM cells prepared from the femur of mice that received a transplant with c-Maf+/+ fetal liver cells (left) or c-Maf−/− fetal liver cells (right). The gates of CD71+/TER-119− (top left region: Q1), CD71+/TER-119+ (top right region: Q2), and CD71−/TER-119+ (bottom right region: Q3) in BM cells are defined as indicated. (D) Frequencies (%) of cells found in each region are shown. (E) Cell numbers of each region per femur are shown. (F) Flow cytometric analyses of the TER-119 and CD71 expression in total spleen cells prepared from mice that received a transplant with c-Maf+/+ fetal liver cells (left) and c-Maf−/− fetal liver cells (right). The frequencies (%) of CD71+ (top left and top right regions) and CD71−/TER-119+ (indicated squared gate in the bottom right region) cells in the spleen are indicated. (G) Frequencies (%) of each region are shown. (H) Cell numbers of each region per spleen are shown. Note that there are no significantly different frequencies or numbers of BM or spleen cells between mice that received a transplant with c-Maf+/+ fetal liver cells versus with c-Maf−/− fetal liver cells. □ represents mice that received a transplant with c-Maf+/+ fetal liver cells; ■, mice that received a transplant with c-Maf−/− fetal liver cells; n = 4 per group. FLC indicates, fetal liver cell.

c-Maf−/− fetal liver cells can reconstitute adult hematopoiesis in lethally irradiated mice. (A) Eight to 10 weeks after transplantation, the donor leukocyte chimerism of the mice reconstituted with c-Maf−/− fetal liver cells was comparable to that of the mice reconstituted with c-Maf+/+ fetal liver cells. The reconstitution efficiency was checked by flow cytometry with the use of the Ly5.1/Ly5.2 ratio of peripheral blood cells. Donor chimerism was determined to be as follows: (%Ly5.1+/%Ly5.1+ + %Ly5.2+) × 100. (B) No significant difference was found in the proportion of each lineage in peripheral blood between c-Maf+/+ fetal liver cells transplanted into mice and c-Maf−/− fetal liver cells transplanted into mice. (C) Flow cytometric analyses of the TER-119 and CD71 expression in total BM cells prepared from the femur of mice that received a transplant with c-Maf+/+ fetal liver cells (left) or c-Maf−/− fetal liver cells (right). The gates of CD71+/TER-119− (top left region: Q1), CD71+/TER-119+ (top right region: Q2), and CD71−/TER-119+ (bottom right region: Q3) in BM cells are defined as indicated. (D) Frequencies (%) of cells found in each region are shown. (E) Cell numbers of each region per femur are shown. (F) Flow cytometric analyses of the TER-119 and CD71 expression in total spleen cells prepared from mice that received a transplant with c-Maf+/+ fetal liver cells (left) and c-Maf−/− fetal liver cells (right). The frequencies (%) of CD71+ (top left and top right regions) and CD71−/TER-119+ (indicated squared gate in the bottom right region) cells in the spleen are indicated. (G) Frequencies (%) of each region are shown. (H) Cell numbers of each region per spleen are shown. Note that there are no significantly different frequencies or numbers of BM or spleen cells between mice that received a transplant with c-Maf+/+ fetal liver cells versus with c-Maf−/− fetal liver cells. □ represents mice that received a transplant with c-Maf+/+ fetal liver cells; ■, mice that received a transplant with c-Maf−/− fetal liver cells; n = 4 per group. FLC indicates, fetal liver cell.

Next, we attempted to examine whether erythroblast differentiation in the BM and spleen was perturbed. The absolute number of BM cells (19.9 ± 1.69 and 18.3 ± 1.56 × 106 cells/femur for c-Maf+/+ and c-Maf−/− fetal liver cells transplanted into mice, respectively) as well as the spleen weight (68.4 ± 3.28 and 73.8 ± 5.44 mg for c-Maf+/+ and c-Maf−/− fetal liver cells transplanted into mice, respectively) were comparable between mice that received a transplant with c-Maf+/+ and c-Maf−/− fetal liver cells. Each stage of the erythroblasts was prospectively separated by a flow cytometric protocol that used TER-119 and CD71 Abs. The frequencies and cell numbers of each region in the recipient BM receiving c-Maf−/− fetal liver cells were comparable to those in the recipient with c-Maf+/+ fetal liver cells (Figure 6C-E). Similar results were also observed with spleen cells (Figure 6F-H). Applying another method that TER-119 and CD44 Abs,30 we assessed erythropoiesis in the BM of the mice that received a transplant. The differentiation status was found to be comparable between the recipients with c-Maf+/+ and c-Maf−/− fetal liver cells (supplemental Figure 5A-C). Overall, these results indicate that c-Maf−/− hematopoietic cells are able to reconstitute the hematopoietic system in lethally irradiated mice and that they have the ability to produce adequate amounts of erythroid cells.

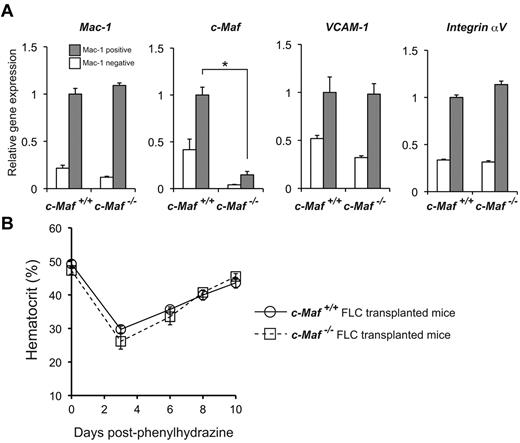

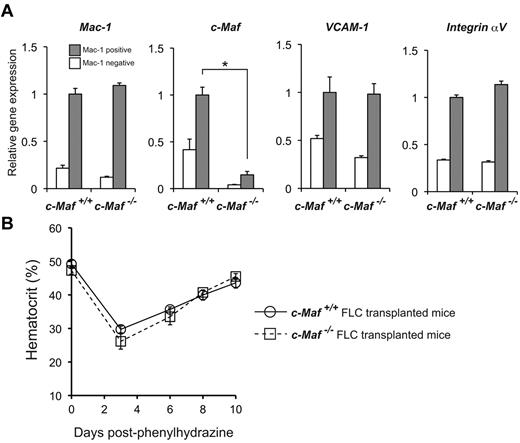

c-Maf deficiency does not impair erythropoiesis during PHZ-induced anemia

To assess the role of c-Maf in adult hematopoiesis further, we analyzed BM macrophages in a similar manner as that used to analyze fetal liver cells. The donor-derived BM leukocyte and BM macrophage chimerisms in the mice reconstituted with c-Maf−/− fetal liver cells were comparable with those of the recipient mice with control fetal liver cells (supplemental Figure 6). To determine whether VCAM-1 mRNA levels were decreased, Mac-1+ cells from the BM of mice that received a transplant were sorted and analyzed for mRNA abundance of Mac-1, c-Maf, VCAM-1, and Integrin αV by real-time RT-PCR analysis. These experiments showed no differences in expression levels in mice that received a transplant with c-Maf+/+ and c-Maf−/− fetal liver cells except for c-Maf (Figure 7A), in contrast to the results obtained with the use of fetal liver cells. To reconfirm these results with a functional assay, mice were challenged with PHZ, and their hematocrits were monitored for the next 10 days (Figure 7B). The hematocrits of mice from both groups were comparable during this period. These results indicate that c-Maf deficiency does not impair stress erythropoiesis during PHZ-induced anemia in adult mice.

Responses of mice that received a transplant with c-Maf−/− fetal liver cells to induce anemia. (A) Comparisons of mRNA expression of Mac-1, c-Maf, VCAM-1, and Integrin αV are shown. Total RNA obtained from the Mac-1+ positive fraction (gray bar) and the Mac-1− fraction (open bar) of BM cells was used for analyses. Note that VCAM-1 mRNA expression of the Mac-1+ fraction in mice that received a transplant with c-Maf−/− fetal liver cells is comparable with that of control mice that received a transplant with c-Maf+/+ fetal liver cells; n = 5 per group; FLC indicates fetal liver cell; Expression of the c-Maf+/+ BM Mac-1 fraction was set to 1.0. All of the data are presented as mean ± SEM. (B) Mice with a baseline hematocrit of ≥ 35% were used. Four mice that received a transplant with c-Maf+/+ fetal liver cells (open circle with solid line) and 4 mice that received a transplant with c-Maf−/− fetal liver cells (open square with dashed line) were injected with phenylhydrazine on days 0, 1, and 3. Hematocrit levels were assessed on days 0, 3, 6, 8, and 10. Data are mean ± SEM.

Responses of mice that received a transplant with c-Maf−/− fetal liver cells to induce anemia. (A) Comparisons of mRNA expression of Mac-1, c-Maf, VCAM-1, and Integrin αV are shown. Total RNA obtained from the Mac-1+ positive fraction (gray bar) and the Mac-1− fraction (open bar) of BM cells was used for analyses. Note that VCAM-1 mRNA expression of the Mac-1+ fraction in mice that received a transplant with c-Maf−/− fetal liver cells is comparable with that of control mice that received a transplant with c-Maf+/+ fetal liver cells; n = 5 per group; FLC indicates fetal liver cell; Expression of the c-Maf+/+ BM Mac-1 fraction was set to 1.0. All of the data are presented as mean ± SEM. (B) Mice with a baseline hematocrit of ≥ 35% were used. Four mice that received a transplant with c-Maf+/+ fetal liver cells (open circle with solid line) and 4 mice that received a transplant with c-Maf−/− fetal liver cells (open square with dashed line) were injected with phenylhydrazine on days 0, 1, and 3. Hematocrit levels were assessed on days 0, 3, 6, 8, and 10. Data are mean ± SEM.

Discussion

Macrophages are important for hematopoiesis because they engulf nuclei of erythroblasts in erythroblastic islands, where the macrophages are surrounded by erythroblasts in the fetal liver, BM, and spleen.3 In the present study, we demonstrated that c-Maf is crucial for the function of macrophages in erythropoiesis.

Our study clearly shows that disruption of c-Maf causes impaired erythroblastic island formation because of dysfunction of fetal liver macrophages. In a methylcellulose culture system, c-Maf−/− hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells in fetal liver have a normal potential to differentiate into different lineages, and they can reconstitute the hematopoietic system of lethally irradiated mice. Because c-Maf is specifically expressed in macrophages within the fetal liver, it has been thought that c-Maf does not regulate fetal liver erythropoiesis through a function of erythroblasts, but rather that it performs an adhesive function of macrophages. There are several reports of genes that are related to the formation and maintenance of erythroblastic islands, based on the knockout mice technique. Retinoblastoma-deficient mice were analyzed for macrophage differentiation, and erythroblastic island formation was reported to be impaired in these mice.31 The fetal livers of Dnase2a−/− mice contain many macrophages that carry undigested DNA, and IFN-β mRNA was expressed by the resident macrophages in the Dnase2a−/− fetal liver.37,38 In c-Maf−/− fetal livers, retinoblastoma was comparably expressed in c-Maf+/+ and c-Maf−/− macrophages; therefore, the existence of impaired erythroblastic islands in c-Maf−/− mice is not related to retinoblastoma (supplemental Figure 7). In addition, we could not detect the abnormal foci that are found in Dnase2a−/− fetal livers or the expression of IFN-β mRNA (data not shown). Thus, retinoblastoma or DNase II do not cause the impaired erythroblastic islands of c-Maf−/− embryos.

To identify the target genes of c-Maf in fetal liver macrophages, we performed microarray analysis and found that VCAM-1 was one of these target genes. VCAM-1 is an adhesion molecule expressed on macrophages of erythroblastic islands. Previous studies have shown that maintenance of erythroblastic islands was impaired by an anti–VCAM-1 Ab.8,39 As shown in Figure 5, mRNA and cell surface protein expression of VCAM-1 was decreased in c-Maf−/− fetal liver macrophages. This suggests that decreased expression of VCAM-1 may be at least in part responsible for impaired erythroblastic island maintenance in c-Maf−/− fetal liver. The large Maf proteins are known to bind MAREs or the 5′ AT-rich half-MARE. In the VCAM-1 promoter region, there are 3 half-MARE sites, so c-Maf may directly regulate VCAM-1 expression in fetal liver macrophages. Recently, Kohyama et al40 revealed that Spi-C controls the development of red pulp macrophages required for red blood cell recycling, and it regulates VCAM-1 expression in red pulp macrophages. These earlier results and ours suggest that the regulation of VCAM-1 expression by transcription factors strongly affects the function of tissue macrophages. In macrophages, c-Maf regulates the expression of cell surface molecules that are involved in macrophage function. In this analysis, expression of Integrin αV in c-Maf−/− macrophages was transiently up-regulated. It is difficult to identify the mechanism, but it seems probable there may be a compensation mechanism causing down-regulation of VCAM-1 in fetal macrophages.

We found that c-Maf is crucial for erythroblastic island maintenance in the embryonic stage. In a reconstitution assay that used fetal liver cells, c-Maf−/− hematopoietic cells reconstituted hematopoiesis in lethally irradiated mice, and the mice that received a transplant with c-Maf−/− fetal liver cells did not show anemia in the steady state (Table 3). To test the function of c-Maf in the adult stage further, we analyzed the mice that received a transplant by BM cell assay and by a PHZ stress test. Neither decreased expression level of VCAM-1 mRNA nor impaired erythroid differentiation were observed. In addition, the response to the PHZ stress test was also comparable between the 2 groups. These results indicate that c-Maf might activate the VCAM-1 gene and affect erythroblastic island maintenance in a context-dependent manner. Such observations were reported previously. In Palld−/− fetal liver, erythroblastic island formation or integrity was impaired, but Palld−/− fetal liver cells could reconstitute the blood of lethally irradiated mice.6 Thus, c-Maf and Palladin are important for erythroblastic islands in the embryonic stage, but their importance in the adult stage is still unconfirmed. However, a previous study found that ICAM-4 is critical for erythroblastic island formation in adult marrow,41 but the role of ICAM-4 in the embryonic stage has been left for future study. Overall, previous studies and our results indicate that there might be different mechanisms or regulation processes or both between fetal liver and adult marrow/spleen erythroblastic island formation and maintenance. This suggests that macrophages in fetal liver and in the adult marrow/spleen might have different developmental origins. Further studies are needed to investigate this possibility.

Recent reports have indicated that definitive as well as primitive erythropoiesis are related to erythroblastic islands.39 Kingsley et al42 revealed that yolk sac-derived primitive erythroblasts enucleate during gestation, and Isern et al39 and Fraser et al43 also have demonstrated, using transgenic mouse lines, that primitive erythroblasts enucleate within the fetal liver.39,43 Our quantitative RT-PCR results suggested that definitive erythropoiesis is more involved in erythroblastic islands than is primitive erythropoiesis in vivo (supplemental Figure 3). Therefore, this result indicates that definitive erythropoiesis in fetal liver is predominantly impaired in c-Maf−/− embryos, whereas primitive erythropoiesis is maintained in c-Maf−/− embryos.

Our study showed that c-Maf−/− mice were embryonic lethal on the C57BL/6 background and that c-Maf−/− macrophages might be responsible for this. Previous reports from our laboratory and from others indicated that c-Maf−/− mice were lethal around birth on the C57BL/6J × 129/SV background, but some mice on the BALB/c background live to adulthood.14,44,45 It is known that cytokine production in T-helper cells differs between C57BL/6 and BALB/c backgrounds. Recently Mills at al46 reported that cytokine production in macrophages differed according to the backgrounds of the mice. On a C57BL/6 background, inflammatory cytokine production is more dominant than on a BALB/c background. It is well known that apoptotic cells are recognized by macrophages and induce the production of proinflammatory cytokines.47 Increased amounts of apoptotic cells were observed in c-Maf−/− fetal liver, suggesting that inflammatory cytokine production might be triggered in c-Maf−/− fetal liver. Therefore, our c-Maf−/− mice were lethal at an earlier gestational date than indicated by previous reports. We found that c-Maf−/− fetal liver macrophages produced more cytokines than c-Maf+/+ fetal liver macrophages (supplemental Figure 7). Hence, it is tempting to speculate that increased numbers of apoptotic cells trigger the production of inflammatory cytokines that are reported to be responsible for anemia and embryonic lethality. This speculation supports the idea that the c-Maf−/− macrophages are responsible for anemia and lethality. This hypothesis may also explain the phenotype discrepancy between c-Maf−/− mice and F4/80−/− or VCAM-1−/− mice. Neither F4/80 knockout mice nor mice with a conditional ablation of VCAM-1 in blood cells are embryonic lethal.48-50 In addition, c-Maf is a transcription factor, and it might regulate sets of target genes in fetal macrophages that might in turn be responsible for the observed anemia and lethality.

In summary, we have shown that the transcription factor c-Maf gene affects the hematopoietic microenvironment by playing a crucial role in regulating fetal liver macrophages.

An Inside Blood analysis of this article appears at the front of this issue.

The online version of the article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Yamashita and Dr Ohneda for the VCAM-1 promoter containing luciferase plasmid.

This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI no. 21220009) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (MEXT). This work was also supported by Grants from the Astellas Foundation for Research on Metabolic Disorders and the Uehara Memorial Foundation. M.K. is a recipient of a Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Research Fellowship for Young Scientists (21384).

Authorship

Contribution: M.K., K.H., M.H., M.N., T.O., H.S., and M.T.N.T. performed experiments; M.K., K.H., and M.H. analyzed results and made figures; M.K., K.H., M.H., and S.T. designed the research; M.K., M.H., and S.T. wrote the paper; K.U. performed microarray analysis; and T.K., H.N., S.C., and S.T. supervised the project.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Satoru Takahashi, Departments of Anatomy and Embryology, Institute of Basic Medical Science, University of Tsukuba, 1-1-1 Tennodai, Tsukuba, Ibaraki 305-8575, Japan; e-mail: satoruta@md.tsukuba.ac.jp.