Abstract

When refrigerated platelets are rewarmed, they secrete active sialidases, including the lysosomal sialidase Neu1, and express surface Neu3 that remove sialic acid from platelet von Willebrand factor receptor (VWFR), specifically the GPIbα subunit. The recovery and circulation of refrigerated platelets is greatly improved by storage in the presence of inhibitors of sialidases. Desialylated VWFR is also a target for metalloproteinases (MPs), because GPIbα and GPV are cleaved from the surface of refrigerated platelets. Receptor shedding is inhibited by the MP inhibitor GM6001 and does not occur in Adam17ΔZn/ΔZn platelets expressing inactive ADAM17. Critically, desialylation in the absence of MP-mediated receptor shedding is sufficient to cause the rapid clearance of platelets from circulation. Desialylation of platelet VWFR therefore triggers platelet clearance and primes GPIbα and GPV for MP-dependent cleavage.

Introduction

Platelets have the shortest shelf life of all major blood components and are the most difficult to store. When platelets are stored at room temperature, their shelf life is limited to 5 days mainly because of bacterial growth and the risk of transfusion-associated sepsis.1 Methods of pathogen inactivation may extend platelet shelf life to 7 days2 but will unfortunately not prevent modifications associated with platelet storage that alter the functional integrity and structure of platelets, a process termed as platelet storage lesion.3 One characteristic of platelet storage lesion is metalloproteinase (MP)–dependent loss of surface GPIbα and GPV subunits of the VWF receptor (VWFR) complex.4,5 The membrane-bound MP ADAM17, also known as TACE (TNF-α–converting enzyme), is the MP most intimately involved in agonist-induced shedding of GPIbα6 and GPV,7 generating 130 and 80 kDa of soluble subfragments of these subunits, respectively. ADAM17 activity is downstream of p38 MAPK activation.8 Recent reports have shown that inhibiting ADAM17 activity during room temperature storage improves the recovery and survival of stored platelets.4,8

Platelet refrigeration would be expected to slow bacterial growth and possibly to retard the loss of platelet function after storage. However, in contrast to other blood components, platelets do not tolerate refrigeration and are rapidly cleared from the circulation on transfusion.9,10 We have demonstrated that 2 distinct pathways recognizing GPIbα remove refrigerated platelets in recipient's livers: (1) αMβ2 integrins (Mac-1) on hepatic resident macrophages (Kupffer cells) selectively recognize irreversibly clustered β-N-acetylglucosamine (β-GlcNAc)–terminated glycans on GPIbα9,11-13 ; and (2) hepatic asialoglycoprotein receptors recognize desialylated GPIbα.10

Mammalian sialidases are a family of 4 enzymes (Neu1-4) that hydrolyze the glycosidic linkages of neuraminic acids. Neu1 is a lysosomal sialidase with narrow substrate specificity and preferentially hydrolyzes sialic acid from glycoproteins. Neu2 is a cytosolic enzyme with wide substrate specificity. Neu3 is a plasma membrane-bound sialidase, which preferentially hydrolyses sialic acid from gangliosides. Neu4 is a novel human luminal lysosomal enzyme (for review see Monti et al14 ). Activation and stabilization of Neu1 in the lysosome requires its association with a lysosomal multienzyme complex containing the lysosomal carboxypeptidase A (cathepsin A/protective protein, CathA), β-galactosidase, and N-acetylgalactosamine-6-sulfate sulfatase (for review see Pshezhetsky and Ashmarina15 ). Recent studies have reported that surface-expressed Neu1 tightly regulates neurotrophin receptors TrkA and TrkB, which involve Neu1 and matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MP-9) cross talk in complex with these receptors.16 Toll-like receptor type 4 and macrophage Fc receptor functions are also regulated by Neu1-mediated desialylation.17,18

Because refrigeration causes desialylation of platelet glycoproteins,10 we hypothesized that sialidases, released during storage, hydrolyze sialic acid from GPIbα and GPV and initiate cross talk with ADAM17, leading to the enhanced cleavage of GPIbα and GPV.5,7,19 Here, we demonstrate that resting platelets contain an internal pool of sialidase activity, which is up-regulated after refrigeration and hydrolyzes terminal sialic acid moieties from platelet glycoproteins, including VWFR. Desialylation targets refrigerated platelets for removal, a process that can be circumvented by adding sialidase inhibitors during storage. Once desialylated, GPIbα and GPV become substrates for MPs, primarily ADAM17, and are cleaved from the platelet's surface. Even in the absence of ADAM17-mediated shedding, desialylation causes mouse platelets to be rapidly removed from circulation. We conclude that VWFR desialylation triggers platelet clearance and primes GPIbα and GPV for MP-dependent cleavage.

Methods

Animals

Age-, strain-, and sex matched (male) C57BL/6 wild-type (WT) mice (The Jackson Laboratory) were used in all experiments. Generation of Adam17ΔZn/ΔZn chimeric mice has been described.5 Mice were maintained and treated as approved by Harvard Medical Area Standing Committee on Animals according to standards of the National Institutes of Health as set forth in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Materials

Sources of reagents are as follows: GM6001, N-t-Butoxycarbonyl-L-leucyl-L-tryptophan Methylamide, Biotin-NHS from Calbiochem; protein G-Sepharose 4 fast flow beads from GE Healthcare Bio-sciences AB; Celltracker Green from Molecular Probes Inc; enhanced chemiluminescence system (ECLS) from Pierce; protease inhibitor cocktail, Complete from Roche Diagnostics GmbH; Amicon ultra centrifugal filter devices, Immobilon-P membrane from Millipore; polyacrylamide gels from Cambrex; and MagicMark XP Western standard from Invitrogen.

Antibodies

Anti–human PE or unconjugated anti–human GPIX mAb (ALMA.16), GPV mAb (NAM12-6B6), PE anti–human IgG, streptavidin-PE and anti–human β3 (RUU-PL7F12-FITC) were from BD Biosciences. Unlabeled, FITC or PE-labeled rat anti–mouse GPIbα (Xia.G7, Xia.B2, and Xia.G5), GPVI mAb (6.E10 and Jaq.1), GPIX mAb (Xia.B4), GPV mAb (Gon.C2), GPIbβ mAb (Xia.C3), FITC- or PE-labeled negative control rat or rabbit IgG, were from Emfret Analytics; PE-conjugated anti–mouse β3 (2C9.G2) from BD Biosciences, peroxidase-conjugated goat anti–mouse, rabbit, or rat IgG Abs from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc; Alexa Fluor 568 rabbit anti–goat and 488 goat anti–rabbit IgGs were from Molecular Probes; streptavidin-peroxidase (POD) from Roche; FITC-conjugated AN5119 from Dako Cytomation; FITC-conjugated and nonconjugated SZ2 from Immunotech; PE-Cy5–conjugated HIP120 from BD Biosciences; nonconjugated VM16d21 from Accurate Chemical and Scientific Corp; WM2322 was obtained from Dr M. Berndt (Monash University); 6D1 was obtained from Dr Barry Coller (The Rockefeller University); WM23, VM16d, 6D1, and NAM12-6B6 were conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 mAb labeling kit from Molecular probes. Anti–β-galactosidase IgG was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology.

Platelet preparation

Venous blood was obtained from volunteers by venipuncture into 0.1 volume of Aster Jandl citrate-based anticoagulant. Approval for blood drawing was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Brigham and Women's Hospital, and informed consent was approved according to the Declaration of Helsinki. Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) was prepared by centrifugation at 125g for 20 minutes, and platelets were separated from PRP by centrifugation for 5 minutes at 850g in buffers containing 1 μg/mL prostaglandin E1. The platelet pellet was washed with 140mM NaCl, 5mM KCl, 12mM trisodium citrate, 10mM glucose, 12.5mM sucrose, and 1 μg/mL prostaglandin E1, pH 6.0 (buffer A) and resuspended in 10mM HEPES, 140mM NaCl, 3mM KCl, 0.5mM MgCl2, 10mM glucose, and 0.5mM NaHCO3, pH 7.4 (buffer B). Blood was collected from mice by retro-orbital plexus bleeding into Aster Jandl anticoagulant. Mouse PRP was obtained by centrifugation of the murine blood at 300g for 8 minutes, followed by centrifugation of the supernatant buffy coat at 200g for 6 minutes. Mouse platelets were washed by 2 sequential centrifugations at 1200g for 5 minutes in buffer A and resuspended in buffer B. The final platelet concentration was determined with Sphero blank calibration particles (3.5-4.0 μm), from Spherotech Inc on a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences).

Platelet storage

Human or murine platelets in buffer B or PRP were stored at 4°C for 2-48 hours without agitation. Mouse platelets at 3 × 109/mL were maintained in 2.5 × 2.5-cm bags of gas-permeable plastic. Refrigerated platelets were rewarmed for 15 minutes at 37°C before in vitro analysis unless stated otherwise. We incubated isolated platelets in buffer B with 1mM N-acetylneuraminic acid, 2,3-dehydro-2-deoxy-sodium salt (DANA; Calbiochem) or PBS as control for 30 minutes at 37°C to inhibit sialidases. Before storage, platelets were pelleted by centrifugation and resuspended in plasma containing 1mM DANA or the equivalent volume of PBS as control.

Transfusion experiments

Platelets, 108 cells/10 g of body weight, CMFDA-labeled, fresh or refrigerated at 4°C for 48 hours, were injected into anesthetized WT mice of the same strain and age.10 The % of fluorescent WT platelets recovered at < 2 minutes was 3.5% ± 0.13% (mean ± SD). In experiments that used Adam17+/+ platelets at room temperature as control, the recovery was 3.82% ± 0.24% (mean ± SD).

Measurement of platelet glycan exposure

Fresh platelets at 22°C or platelets stored in plasma for 48 hours at 4°C were collected by centrifugation at 830g for 5 minutes and resuspended in buffer B at 107/mL. Surface β-galactose and βGlcNAc were analyzed with 10 μg/mL FITC-conjugated Erythrina cristagalli lectin (ECL) or 0.1 μg/mL FITC-conjugated s-WGA, respectively. Samples were incubated at room temperature for 20 minutes and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Flow cytometric analysis of the GPIb-V-IX receptor complex, αIIbβ3, and GPVI surface expression

Platelets were stored in the cold for up to 48 hours in plasma, or buffer B, with or without 100μM GM6001, 40μM SB203580, or the negative control compound and were rewarmed for 15 minutes 37°C. Ab labeling of platelets was performed for 20 minutes at room temperature (1 × 107 cells/mL) with fluorescently conjugated mAbs and appropriate IgG controls. Platelets were analyzed on a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). Data are presented as the percentage of receptor surface expression with 100% calculated from the mean fluorescence intensity on fresh platelets before storage.

Removal of sialic acid from platelets with the use of exogenous sialidase

Isolated platelets (108/mL) were incubated for 5 minutes. with 1-10mU of α2-3,6,8,9- sialidase from Arthrobacter ureafaciens (Calbiochem) at 37°C or not. Sialidase activity was inhibited with 5mM DANA (Calbiochem). In some experiments, 100μM GM6001 was added.

Sialidase activity

Platelets were assayed for sialidase activity with the use of 2′-(4-methylumbelliferyl)-α-D-N-acetylneuraminic acid (4-MU-NeuAc; BioSynth International). The 200-μL reactions were at 37°C and initiated by adding 125μM 4-MU-NeuAc. Platelets, 6 × 107, were used for each point permeabilized with 2 μL of 10× BD Perm/Wash Buffer (BD Biosciences). Aliquots of 60 μL of each reaction mixture were sampled, quenched with 180 μL of 1M Na2CO3, and diluted with 60 μL of reaction buffer. Background fluorescence was measured by incubating 60 μL of platelets and substrate in separate reactions and sequentially adding them to 180 μL of 1M Na2CO3.

Microscopy

Platelets were fixed in BD Cytofix or fixed and permeabilized in BD Cytofix/Cytoperm (22°C, 20 minutes.) and centrifuged onto poly-L-lysine–coated coverslips (500g for 2.5 minutes). Cells were blocked as previously described23,24 ; incubated overnight with rabbit anti-Neu1 IgG Ab, anti-Neu3 Ab, and/or a goat anti–β-galactosidase from Santa Cruz Biotechnology at 4°C; and then washed in triplicate with PBS. The washed platelets were incubated for 1.5 hours at room temperature with the appropriate antispecies secondary Ab Alexa Fluor 488 or 568 from Molecular Probes at a dilution of 1:500 followed by 3 washes in PBS. Samples were prepared for analysis, and fluorescent images of platelets were visualized by fluorescent microscopy as described.23,24 Images were taken by Nikon Eclipse TE-2000E fluorescent microscope with 60× NA 1.4 using differential interference contrast objectives with a 1.5 optimas (Nikon) and captured with an Orea-11 ER cooled CCD camera (Hamamatsu); shutter and image acquisition were controlled by MetaMorph software (MDS Analytical Technologies).

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting

Murine platelets (2 × 108 cells/mL) were biotinylated with 1 μg/mL biotin-NHS (1 hour at room temperature) and washed. They were immediately incubated with thrombin (1 U/mL) or refrigerated in plasma or buffer for 48 hours and rewarmed. The amount of cleaved glycoprotein in stored and rewarmed samples was compared with the amount remaining in the supernatant fluid after centrifugation at 2000g for 10 minutes. Platelets in the starting material (input, not centrifuged) or the supernatant fluids clarified of platelets (shed) were lysed with NP40 containing protease inhibitor cocktail (Complete), 3mM EGTA, and 3mM Na3VO4. Insoluble material was removed by centrifugation.12 GPIbα or GPV was immunoprecipitated from the samples with the use of 10 μg of anti-GPIbα mAb (Xia.G7) or anti-GPV mAb (Gon.C2), or an IgG-negative control combined with protein G–Sepharose 4 fast flow beads. Immune complexes were collected by centrifugation, and the pelleted material was dissolved in SDS-gel sample buffer and separated by 8% or 4%-20% SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions. Biotinylated proteins were visualized with streptavidin-POD and ECLS and quantified by densitometry (ImageJ and Adobe Photoshop).

Washed Adam17ΔZn/ΔZn and Adam17+/+ platelets (1 × 108 cells/mL) were refrigerated for 3, 24, and 48 hours in buffer B and rewarmed 15 minutes at 37°C. The resultant total platelet fractions were prepared for immunoblotting with anti–mouse GPIbα mAb (Xia.G7), followed by staining with secondary POD-conjugated Ab. Anti-Neu1 polyclonal rabbit IgG Ab was used to detect Neu1 in human and mouse platelets followed by secondary POD-conjugated Ab.

Release of GPIbα ectodomain from platelets

Suspensions of platelets, used immediately after isolation or refrigerated for 2, 24, and 48 hours and rewarmed for 15 minutes at 37°C, were centrifuged at 10 000g for 30 minutes at 4°C. The resultant supernatant fluids were concentrated, denatured with SDS-PAGE sample buffer containing β-mercaptoethanol, and boiled. Platelet proteins were displayed by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto Immobilon-P membrane. Membranes were probed with 0.5 μg/mL Xia.G7 mAb or 1 μg/mL SZ2 mAb, followed by POD goat anti–rat IgG or rabbit anti–mouse IgG. Detection was by ECLS.

Recombinant MP assays

Recombinant ADAM17 (rADAM17; 5μM) from Calbiochem was added to 108 mouse platelets in buffer B containing 5μM ZnCl2 and incubated for 1 hour at 37°C in the absence or presence of 5mM DANA. Surface expression of GPIbα, GPV, and GPIX and αIIbβ3 was determined by flow cytometry.

Statistical analysis

All data are mean ± SEM unless otherwise indicated because our experiments include imbalanced groups, whereby the precision of the mean effect depends directly on the sample size. We analyzed all numeric data for statistical significance with 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons with Prism software (GraphPad). We considered P values < .05 as statistically significant. Degrees of statistical significance are presented as ***P < .001, **P < .01, and *P < .05.

Results

Addition of the sialidase inhibitor DANA to refrigerated platelets enhances recoveries and circulation lifetimes after transfusion in mice

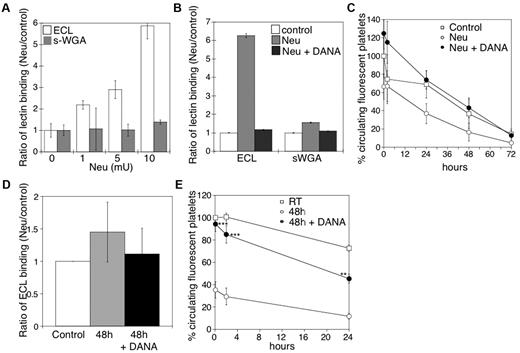

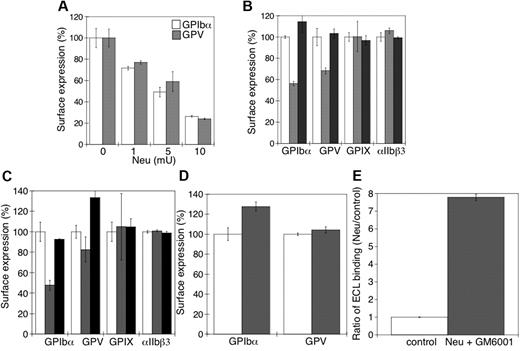

We have previously reported that platelets become desialylated after storage in the cold.10 Incubation of mouse platelets with increasing concentrations of sialidase increased surface β-galactose exposure, but not β-GlcNAc, as detected by lectin-binding assays in the flow cytometer (Figure 1A). We detected an ∼ 6-fold increase of terminal β-galactose by flow cytometry, but not β-GlcNAc, after treatment with 10 mU of sialidase. β-Galactose exposure was completely inhibited by the competitive sialidase inhibitor DANA (Figure 1B). Critically, incubation of mouse platelets with > 5 mU of sialidase caused their rapid removal on transfusion, a process completely prevented when the competitive inhibitor DANA was included (Figure 1C).

Effect of desialylation in vitro on platelet survivals and the effect of DANA on the survival of platelets in mice after refrigerated storage. (A) Flow cytometric analysis of β-galactose or β-GlcNAc exposure on platelet surfaces, as detected with ECL or s-WGA FITC-labeled lectins. Lectin binding to fresh mouse platelets in the presence and absence of α2-3,6,8,9-Sialidase from A ureafaciens (Neu) at the indicated concentrations (n = 5). (B) Flow cytometric analysis of β-galactose or β-GlcNAc exposure on mouse platelet glycoproteins, as detected above in the presence (Neu) and absence (Control) of 10 mU of α2-3,6,8,9-Sialidase (Neu) and the competitive sialidase inhibitor DANA (Neu + DANA; n = 4). (C) Untreated CMFDA-labeled platelets (Control), platelets treated with sialidase (Neu), or sialidase and the competitive inhibitor DANA (Neu + DANA) were infused intravenously into WT mice (108 platelets/10 g of body weight). Blood was drawn at the indicated time points, and platelets were analyzed by flow cytometry. Results are presented relative to fresh room temperature platelets. Data are mean percentage CMFDA-labeled platelets ± SEM. Each point represents 8 mice. (D) Effect of 1mM DANA on the amount of galactose detected by the ECL assay in the stored and rewarmed platelets just before their injection into recipient mice. (E) Survival of mouse platelets stored for 48 hours by refrigeration in the absence or presence of 1mM DANA in the storage solution. The survival of freshly isolated platelets is shown for comparison (n = 7).

Effect of desialylation in vitro on platelet survivals and the effect of DANA on the survival of platelets in mice after refrigerated storage. (A) Flow cytometric analysis of β-galactose or β-GlcNAc exposure on platelet surfaces, as detected with ECL or s-WGA FITC-labeled lectins. Lectin binding to fresh mouse platelets in the presence and absence of α2-3,6,8,9-Sialidase from A ureafaciens (Neu) at the indicated concentrations (n = 5). (B) Flow cytometric analysis of β-galactose or β-GlcNAc exposure on mouse platelet glycoproteins, as detected above in the presence (Neu) and absence (Control) of 10 mU of α2-3,6,8,9-Sialidase (Neu) and the competitive sialidase inhibitor DANA (Neu + DANA; n = 4). (C) Untreated CMFDA-labeled platelets (Control), platelets treated with sialidase (Neu), or sialidase and the competitive inhibitor DANA (Neu + DANA) were infused intravenously into WT mice (108 platelets/10 g of body weight). Blood was drawn at the indicated time points, and platelets were analyzed by flow cytometry. Results are presented relative to fresh room temperature platelets. Data are mean percentage CMFDA-labeled platelets ± SEM. Each point represents 8 mice. (D) Effect of 1mM DANA on the amount of galactose detected by the ECL assay in the stored and rewarmed platelets just before their injection into recipient mice. (E) Survival of mouse platelets stored for 48 hours by refrigeration in the absence or presence of 1mM DANA in the storage solution. The survival of freshly isolated platelets is shown for comparison (n = 7).

On the basis of the results of these experiments, we determined whether DANA could protect platelets against desialylation induced by refrigeration and could prevent the refrigerated platelet clearance. The addition of 1mM DANA to the refrigerated storage bags for 48 hours inhibited the desialylation of the surface of mouse platelets in plasma by 75% (Figure 1D). After refrigeration and transfusion, platelets stored with DANA (Figure 1E) had higher initial recoveries (94.3% of control) and enhanced survival (T1/2 = 29 ± 1.3 hours) compared with platelets stored without DANA (35% recovery; T1/2 = 21.8 ± 2 hours).

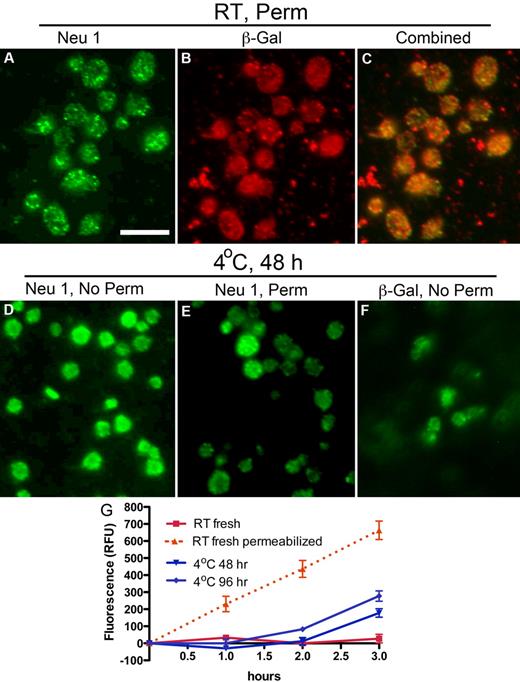

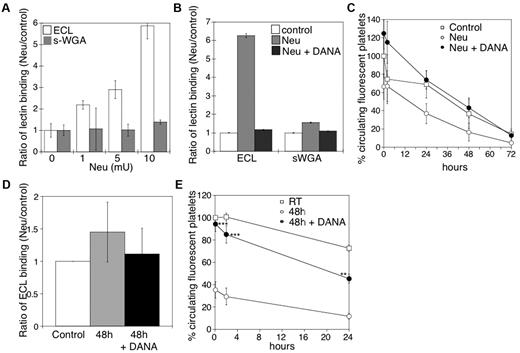

Refrigeration increases platelet surface expression of the Neu1 sialidase and β-galactosidase

The ability of DANA to preserve platelet circulation and to diminish ECL binding after rewarming from refrigeration suggests that platelets expose glycosidases during storage. Therefore, we determined whether platelets express Neu1, Neu3, or β-galactosidase and, if so, investigated the effect of refrigeration on their exposure. Neu1 and Neu3 expression were verified in platelets by immunoblotting (supplemental Figure 1D, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article) and immunofluorescence microscopy (Figure 2; supplemental Figure 1). Neu1 was not detectable on the surface of resting platelets (supplemental Figure 1B), although Neu3 was expressed (supplemental Figure 1E). Detection of Neu1 in resting platelets required detergent permeabilization, which showed Neu1 to reside in multiple small vesicles or granules within platelets (Figure 2A). The distribution of β-galactosidase in resting platelets was similar to that of Neu1 (Figure 2B). Costaining showed partial overlap of Neu1 and β-galactosidase immunofluorescence (Figure 2C). However, after refrigeration, Neu1 and β-galactosidase became detectable on the platelet surface (Figure 2D,F). Anti-Neu1 staining that remained after refrigeration in permeabilized platelets was reduced, although bright vesicular staining was found in a small number of platelets, suggesting that they failed to release their granules (Figure 2E). Hence, refrigeration up-regulates intracellular stores of Neu1 and β-galactosidase to the platelet surface, providing a mechanism for desialylation and degalactosylation of surface glycoproteins. Assays further showed that human platelets have little surface sialidase activity toward 4-MU-NeuAc but that sialidase activity is increased after refrigeration (Figure 2G). This suggests that Neu1 is responsible, at least in part, for the increased sialidase activity exposed by refrigeration. Measurements of total sialidase activity, after permeabilization, indicated that platelets up-regulated ∼ 27%-44% of their total after > 48 hours of refrigeration, (Figure 2G). Although some Neu1 is released into the medium of refrigerated platelets, as evidenced by immunoblotting, we did not detect sialidase activity in the medium of fresh or refrigerated platelets (not shown). These observations are consistent with the notion that Neu1 is active as a membrane complex with other glycan-processing enzymes, including β-galactosidase.25 In view of these findings, we assert that sialidase activity is platelet not plasma derived and up-regulates from an internal platelet store on refrigeration. We cannot exclude that a similar process occurs when platelets are stored at room temperature.

Refrigeration up-regulates glycosidases to the surface of platelets. (A-C) Glycosidase localization in platelets. Immunofluorescence micrographs of fixed and permeabilized resting platelets with the use of anti-sialidase 1 (Neu1) or anti–β-galactosidase (β-Gal) Abs and Alexa-conjugated secondary Abs (green or red). Note the granular pattern of Neu1 and β-Gal staining in the permeabilized platelets (panels A and B, respectively). (C) The combined fluorescence is shown, and some, but not all, of the vesicular structures costain. (D-F) Glycosidase localization in refrigerated platelets. Nonpermeabilized (No Perm) refrigerated (4°C, 48 hours) human platelets were labeled with the anti-Neu1 (D) anti–β-Gal Abs (F). (E) Residual staining for Neu1 in platelets shown by detergent permeabilization (Perm). Scale bar, 5 μm. (G) Sialidase activity associated with fresh (room temperature, RT) or refrigerated human platelets (4°C, 48 or 96 hours). Total sialidase activity in platelets was measured in permeabilized room temperature platelets (n = 3); *P < .05. The amount of 4-methylumbellyferone released in quenched reaction mixtures was measured in 96-well Microfluor-1 Black plates on a Spectra MAX GEMINI EM Microplate Spectrofluorometer (Molecular Devices) with excitation, emission, and cutoff wavelengths of 355, 460, and 455 nm, respectively. Background fluorescence was subtracted from each data point.

Refrigeration up-regulates glycosidases to the surface of platelets. (A-C) Glycosidase localization in platelets. Immunofluorescence micrographs of fixed and permeabilized resting platelets with the use of anti-sialidase 1 (Neu1) or anti–β-galactosidase (β-Gal) Abs and Alexa-conjugated secondary Abs (green or red). Note the granular pattern of Neu1 and β-Gal staining in the permeabilized platelets (panels A and B, respectively). (C) The combined fluorescence is shown, and some, but not all, of the vesicular structures costain. (D-F) Glycosidase localization in refrigerated platelets. Nonpermeabilized (No Perm) refrigerated (4°C, 48 hours) human platelets were labeled with the anti-Neu1 (D) anti–β-Gal Abs (F). (E) Residual staining for Neu1 in platelets shown by detergent permeabilization (Perm). Scale bar, 5 μm. (G) Sialidase activity associated with fresh (room temperature, RT) or refrigerated human platelets (4°C, 48 or 96 hours). Total sialidase activity in platelets was measured in permeabilized room temperature platelets (n = 3); *P < .05. The amount of 4-methylumbellyferone released in quenched reaction mixtures was measured in 96-well Microfluor-1 Black plates on a Spectra MAX GEMINI EM Microplate Spectrofluorometer (Molecular Devices) with excitation, emission, and cutoff wavelengths of 355, 460, and 455 nm, respectively. Background fluorescence was subtracted from each data point.

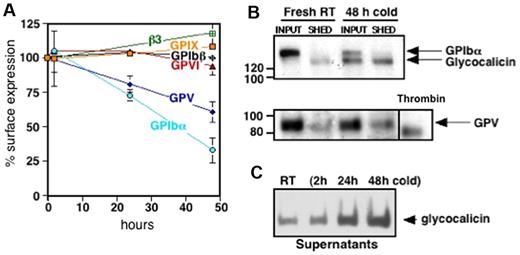

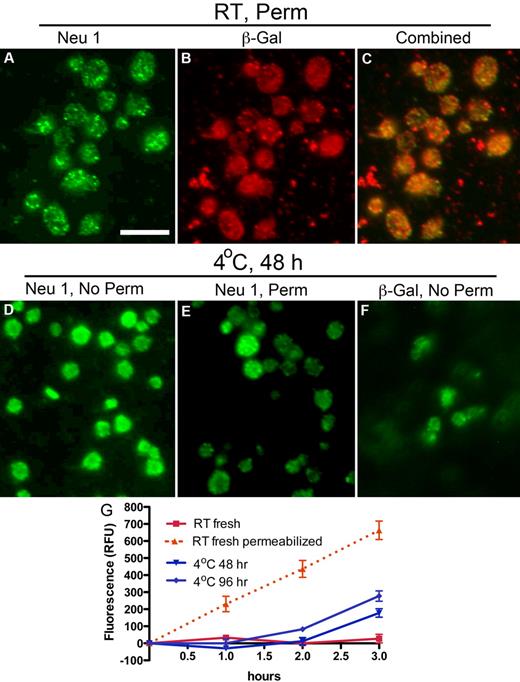

GPIbα and GPV are cleaved from platelets by MPs after refrigeration

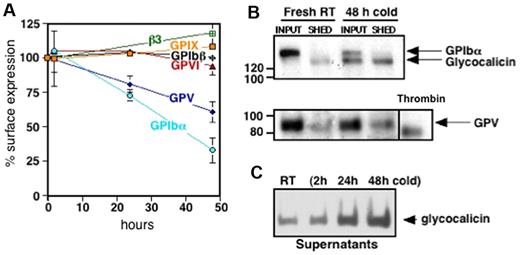

Platelet VWFR, specifically GPIbα, is cleaved after platelet storage. To decipher changes on the platelet surface that influence the removal of refrigerated platelets, we characterized alterations in GPIbα, GPIbβ, GPIX, and GPV. Figure 3A shows a decrease in surface expression of GPIbα after refrigerated storage for 24 and 48 hours and rewarming by 27% ± 4% and 67% ± 9%, respectively. GPV decreased by 19% ± 6% after 24 hours and 40% ± 8% after 48 hours of refrigeration and rewarming. Surface expression of GPIbβ and GPIX, the collagen receptor GPVI and the major platelet integrin, αIIbβ3, were not affected by cold storage.

Cold storage primes murine platelets to shed GPIbα and GPV on rewarming. (A) Expression of murine VWFR components (GPIbα, GPIbβ, GPIX, GPV), GPVI, and αIIbβ3 was measured by flow cytometry before and after platelet storage in the cold. Results are expressed as means ± SDs; n = 5. Glycoprotein expression on freshly isolated platelets was set as 100%. (B) Fresh mouse platelets (Fresh RT) were surface-biotinylated, refrigerated in plasma for 48 hours, and rewarmed (48 hours cold). The integrity and/or release of the GPIbα and GPV ectodomains were assessed by immunoprecipitation with the use of specific anti-GPV and anti-GPIbα Abs. Input, indicates platelets and corresponding plasma; SHED, material released into the supernatant fraction after removal of the platelets by centrifugation. Shedding of GPV induced by treating fresh platelets with thrombin (Thr) is also shown. Blots are representative of 3 independent experiments. (C) Immunoblot for GPIbα supernatant lysates from fresh room temperature (RT) or refrigerated mouse platelets (2, 24, and 48 hours cold). The immunoblot is representative of 3 independent experiments.

Cold storage primes murine platelets to shed GPIbα and GPV on rewarming. (A) Expression of murine VWFR components (GPIbα, GPIbβ, GPIX, GPV), GPVI, and αIIbβ3 was measured by flow cytometry before and after platelet storage in the cold. Results are expressed as means ± SDs; n = 5. Glycoprotein expression on freshly isolated platelets was set as 100%. (B) Fresh mouse platelets (Fresh RT) were surface-biotinylated, refrigerated in plasma for 48 hours, and rewarmed (48 hours cold). The integrity and/or release of the GPIbα and GPV ectodomains were assessed by immunoprecipitation with the use of specific anti-GPV and anti-GPIbα Abs. Input, indicates platelets and corresponding plasma; SHED, material released into the supernatant fraction after removal of the platelets by centrifugation. Shedding of GPV induced by treating fresh platelets with thrombin (Thr) is also shown. Blots are representative of 3 independent experiments. (C) Immunoblot for GPIbα supernatant lysates from fresh room temperature (RT) or refrigerated mouse platelets (2, 24, and 48 hours cold). The immunoblot is representative of 3 independent experiments.

Next, we investigated if decreased Ab binding to GPIbα and GPV on refrigerated platelets was because of ectodomain shedding. Figure 3B supports the assertion that 130-kDa and 80-kDa polypeptides from GPIbα and GPV, respectively, are shed from refrigerated and rewarmed platelets. The GPIbα subfragment is the size of glycocalicin, the proteolytic ectodomain of GPIbα, whereas the fragment of GPV is larger than that released by thrombin, indicating cleavage by nonthrombin proteases after platelet refrigeration.26 GPIbα shedding depends on the time of refrigeration, because the amount of glycocalicin released increased with storage time (Figure 3C).

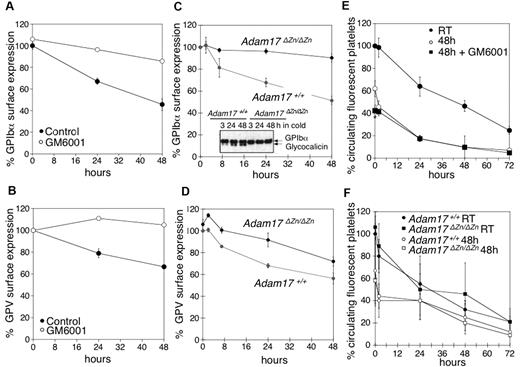

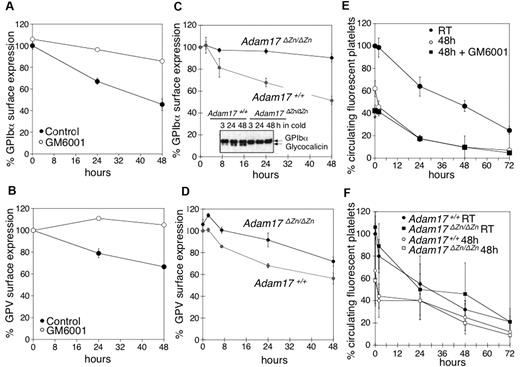

Our next investigation sought to elucidate if MPs mediate GPIbα and GPV shedding in refrigerated platelets. Mouse platelets were refrigerated in plasma for 48 hours in the presence or absence of the broad-spectrum matrix MP inhibitor GM6001, which has been reported to inhibit GPIbα and GPV shedding during room temperature storage.4,5,7,8 Treatment with GM6001 prevented shedding of both GPIbα and GPV from refrigerated mouse platelets (Figure 4A-B). Because GPIbα is primarily shed by ADAM17,5 we investigated the fate of GPIbα and GPV in platelets isolated from mice expressing an inactive form of ADAM17 (Adam17ΔZn/ΔZn) in their blood cells. Figure 4C shows that GPIbα surface expression was unchanged after refrigeration of Adam17ΔZn/ΔZn platelets. This finding was confirmed by anti-GPIbα immunoblots showing that no release of glycocalicin occurs in refrigerated Adam17ΔZn/ΔZn platelets (Figure 4C inset). Cleavage of GPV was also diminished in the Adam17ΔZn/ΔZn platelets (Figure 4D), although not as effectively as that of GPIbα. The results show that MPs, particularly ADAM17, mediate GPIbα and GPV shedding from refrigerated platelets.

Inhibition of MP-mediated GPIbα and GPV shedding after refrigeration does not improve the survival of transfused mouse platelets. (A) GPIbα and (B) GPV surface expression were assessed by flow cytometry. WT mouse PRP was stored for 0, 24, and 48 hours at 4°C in the presence of DMSO (Control) or 100μM of the MP inhibitor GM6001 (n = 6). Surface expression of GPIbα (C) and GPV (D) was determined by flow cytometry on freshly isolated or 24 and 48 hours refrigerated PRP from Adam17+/+ and Adam17ΔZn/ΔZn mice. Results are the mean ± SEM (n = 5). (C, inset) Immunoblot for GPIbα in lysates from Adam17+/+ and Adam17ΔZn/ΔZn platelets stored for 3, 24, and 48 hours in the cold. (E) Fluorescently labeled (CMFDA) fresh PRP (room temperature) or platelets from stored platelet rich plasma in the absence (48 hours) or presence of 100μM GM6001 (48 hours + GM6001) were infused into WT mice (108 platelets/10 g of body weight). Blood was drawn at the indicated time points, and platelets were immediately analyzed by flow cytometry. Results are mean percentage of CMFDA-labeled platelets ± SEM. The percentage of CMFDA-positive fresh platelets at 5 minutes after transfusion was set as 100% (n = 5); *P < .05. Cold-stored platelets are compared. (F) Fluorescently labeled (CMFDA) fresh platelets (Adam17+/+ RT and Adam17ΔZn/ΔZn RT) or platelets from cold stored PRP (Adam17+/+ 48 hours and Adam17ΔZn/ΔZn 48 hours) were infused intravenously into WT mice (108 platelets/10 g of body weight). Blood was drawn at the indicated time points, and platelets were immediately analyzed by flow cytometry. Results are mean percentage of CMFDA-labeled platelets ± SEM. The percentage of CMFDA-positive fresh Adam17+/+ platelets at 5 minutes after transfusion was set as 100% (n = 5).

Inhibition of MP-mediated GPIbα and GPV shedding after refrigeration does not improve the survival of transfused mouse platelets. (A) GPIbα and (B) GPV surface expression were assessed by flow cytometry. WT mouse PRP was stored for 0, 24, and 48 hours at 4°C in the presence of DMSO (Control) or 100μM of the MP inhibitor GM6001 (n = 6). Surface expression of GPIbα (C) and GPV (D) was determined by flow cytometry on freshly isolated or 24 and 48 hours refrigerated PRP from Adam17+/+ and Adam17ΔZn/ΔZn mice. Results are the mean ± SEM (n = 5). (C, inset) Immunoblot for GPIbα in lysates from Adam17+/+ and Adam17ΔZn/ΔZn platelets stored for 3, 24, and 48 hours in the cold. (E) Fluorescently labeled (CMFDA) fresh PRP (room temperature) or platelets from stored platelet rich plasma in the absence (48 hours) or presence of 100μM GM6001 (48 hours + GM6001) were infused into WT mice (108 platelets/10 g of body weight). Blood was drawn at the indicated time points, and platelets were immediately analyzed by flow cytometry. Results are mean percentage of CMFDA-labeled platelets ± SEM. The percentage of CMFDA-positive fresh platelets at 5 minutes after transfusion was set as 100% (n = 5); *P < .05. Cold-stored platelets are compared. (F) Fluorescently labeled (CMFDA) fresh platelets (Adam17+/+ RT and Adam17ΔZn/ΔZn RT) or platelets from cold stored PRP (Adam17+/+ 48 hours and Adam17ΔZn/ΔZn 48 hours) were infused intravenously into WT mice (108 platelets/10 g of body weight). Blood was drawn at the indicated time points, and platelets were immediately analyzed by flow cytometry. Results are mean percentage of CMFDA-labeled platelets ± SEM. The percentage of CMFDA-positive fresh Adam17+/+ platelets at 5 minutes after transfusion was set as 100% (n = 5).

Prevention of GPIbα and GPV shedding does not enhance refrigerated platelet survival

We tested if prevention of receptor loss improves the survival of refrigerated mouse platelets, as has been reported for platelets stored at room temperature.4,8 In WT mice, transfused fresh platelets had a half-life of 37.5 hours, whereas refrigerated platelets had a shorter half-life of 21.2 hours (Figure 4E). Surprisingly, treatment with the MP inhibitor GM6001 during refrigeration did not improve platelet survival after transfusion (Figure 4E), because both control- and GM6001-treated refrigerated platelets had significantly reduced initial recoveries and survival rates. GM6001 did not affect the survival of fresh WT platelets (not shown). To confirm this result, CMFDA-labeled fresh or refrigerated for 48 hours and rewarmed Adam17+/+ or Adam17ΔZn/ΔZn platelets were transfused into mice. Figure 4F shows that refrigerated Adam17ΔZn/ΔZn and Adam17+/+ platelets had both poor survivals. Similarly, the p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 that blocks ADAM17 activity4,8 protected the VWFR complex from cleavage but did not affect the recovery and survival of refrigerated platelets (data not shown). These results show that GPIbα and GPV shedding by MPs is not responsible for the poor circulation of refrigerated platelets.

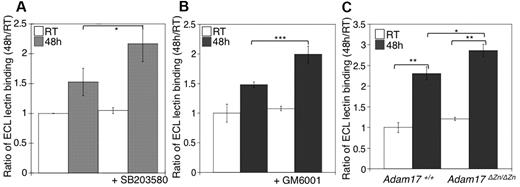

Increased levels of β-galactose exposure on platelets refrigerated in the presence of MP inhibitors

We next investigated the relation between MP activity and β-galactose exposure in stored platelets. As previously reported, we have found that refrigeration significantly increased the binding of the β-galactose–specific ECL to platelets (Figure 5A-B). The addition of GM6001, or the p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580, to stored platelets resulted in increased lectin binding relative to untreated platelets (Figure 5A-B). Interestingly, refrigerated Adam17ΔZn/ΔZn platelets had significantly greater levels of β-galactose exposure than did WT platelets, as judged by ECL binding (Figure 5C). These findings support the notion that GPIbα and GPV, and possibly other ADAM17 substrates, are major glycoproteins desialylated during refrigerated storage. Furthermore, the increased lectin binding to platelets stored with the MP inhibitor results from the maintenance of these desialylated VWFR complex components on the platelets.

Inhibition of receptor loss during refrigeration increases the amount of terminal β-galactose on the platelet surface. (A-B) Flow cytometric analysis of terminal β-galactose on platelets treated with the p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 or the MP inhibitor GM6001 as detected with ECL FITC-labeled lectin. Lectin binding to fresh (RT) or refrigerated (48 hours) platelets in the absence or presence of 40μM SB203580 (A) or 100μM GM6001 (B) is shown. The ratio of mean fluorescence intensity binding to fresh platelets (RT) is plotted. Histograms report the mean ± SEM for 3 separate experiments. *P < .05, **P < .01, and ***P < .001. (C) Flow cytometric analysis of β-galactose exposure on glycoproteins detected with ECL FITC-labeled lectin. Lectin binding to fresh (RT) or longterm-refrigerated (48 hours) Adam17+/+ and Adam17ΔZn/ΔZn platelets is shown (n = 5); *P < .05 and **P < .01.

Inhibition of receptor loss during refrigeration increases the amount of terminal β-galactose on the platelet surface. (A-B) Flow cytometric analysis of terminal β-galactose on platelets treated with the p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 or the MP inhibitor GM6001 as detected with ECL FITC-labeled lectin. Lectin binding to fresh (RT) or refrigerated (48 hours) platelets in the absence or presence of 40μM SB203580 (A) or 100μM GM6001 (B) is shown. The ratio of mean fluorescence intensity binding to fresh platelets (RT) is plotted. Histograms report the mean ± SEM for 3 separate experiments. *P < .05, **P < .01, and ***P < .001. (C) Flow cytometric analysis of β-galactose exposure on glycoproteins detected with ECL FITC-labeled lectin. Lectin binding to fresh (RT) or longterm-refrigerated (48 hours) Adam17+/+ and Adam17ΔZn/ΔZn platelets is shown (n = 5); *P < .05 and **P < .01.

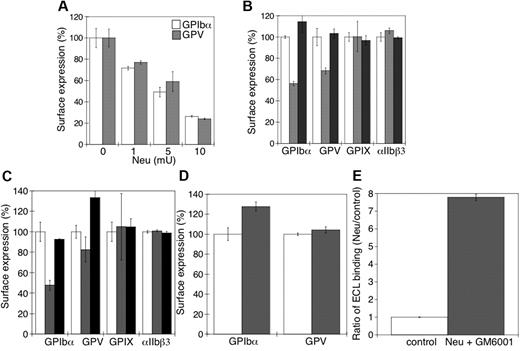

Removal of sialic acid from platelet VWFR stimulates GPIbα and GPV shedding

Next, we sought to determine the relation between the sialidase-dependent removal of sialic acid from the VWFR complex and its proteolytic cleavage by MPs. Figure 6A shows that there was a progressive loss of surface GPIbα and GPV as the sialic acid content was decreased by increasing the amount of sialidase used to treat platelets (P < .05). GPIbα receptor expression was followed with multiple anti-GPIbα Abs to exclude the possibility that desialylation altered Ab binding to GPIbα. Critically, addition of the competitive sialidase inhibitor DANA prevented all GPIbα and GPV shedding (Figure 6B), consistent with the hypothesis that sialic acid loss primes GPIbα and GPV for MP-mediated shedding. Sialidase treatment did not affect the expression of surface GPIX or integrin αIIbβ3 (P > .05).

Loss of surface sialic acid correlates with GPIbα and GPV shedding in mouse platelets. (A) Flow cytometric analysis of surface content of GPIbα or GPV. Ab binding in the presence and absence of α2-3,6,8,9-sialidase from A ureafaciens (Neu) at the indicated concentrations (n = 5). (B) Surface receptor expression (GPIbα, GPV, GPIX, and αIIbβ3) was measured by flow cytometry on mouse platelets in the presence (▩) and absence (□) of 5 mU of α2-3,6,8,9-sialidase. Sialidase activity was inhibited with DANA (■). The mean fluorescence of receptor expression on untreated platelets was set as 100% (n = 4). (C) Surface receptor expression (GPIbα, GPV, GPIX, and αIIbβ3) was measured by flow cytometry on mouse platelets treated with 5μM rADAM17 in the absence (▩) or presence of 5mM DANA (■). Receptor expression of untreated platelets is also shown (□). The mean fluorescence measured on control platelets for each receptor was set as 100%. The data are shown as the mean and SEM of 4 independent experiments. (D) Surface receptor expression (GPIbα and GPV) was measured by flow cytometry on mouse platelets in the presence (▩) and absence (□) of 5μM rADAM17, 5 mU of α2-3,6,8,9-sialidase, and 100μM GM6001. The data are shown as the mean and SEM of 4 experiments. The mean fluorescence measured for each receptor on control platelets was set as 100%. (E) Flow cytometric analysis of β-galactose exposure on glycoproteins is detected with FITC-labeled ECL in untreated platelets (control) or platelets treated with 5 mU of α2-3,6,8,9-sialidase and 100μM GM6001. Data are presented relative as the mean fluorescence of ECL binding to control platelets (n = 4).

Loss of surface sialic acid correlates with GPIbα and GPV shedding in mouse platelets. (A) Flow cytometric analysis of surface content of GPIbα or GPV. Ab binding in the presence and absence of α2-3,6,8,9-sialidase from A ureafaciens (Neu) at the indicated concentrations (n = 5). (B) Surface receptor expression (GPIbα, GPV, GPIX, and αIIbβ3) was measured by flow cytometry on mouse platelets in the presence (▩) and absence (□) of 5 mU of α2-3,6,8,9-sialidase. Sialidase activity was inhibited with DANA (■). The mean fluorescence of receptor expression on untreated platelets was set as 100% (n = 4). (C) Surface receptor expression (GPIbα, GPV, GPIX, and αIIbβ3) was measured by flow cytometry on mouse platelets treated with 5μM rADAM17 in the absence (▩) or presence of 5mM DANA (■). Receptor expression of untreated platelets is also shown (□). The mean fluorescence measured on control platelets for each receptor was set as 100%. The data are shown as the mean and SEM of 4 independent experiments. (D) Surface receptor expression (GPIbα and GPV) was measured by flow cytometry on mouse platelets in the presence (▩) and absence (□) of 5μM rADAM17, 5 mU of α2-3,6,8,9-sialidase, and 100μM GM6001. The data are shown as the mean and SEM of 4 experiments. The mean fluorescence measured for each receptor on control platelets was set as 100%. (E) Flow cytometric analysis of β-galactose exposure on glycoproteins is detected with FITC-labeled ECL in untreated platelets (control) or platelets treated with 5 mU of α2-3,6,8,9-sialidase and 100μM GM6001. Data are presented relative as the mean fluorescence of ECL binding to control platelets (n = 4).

Desialylation is required for ADAM17-mediated GPIbα and GPV shedding

To confirm that desialylated GPIbα and GPV are better ADAM17 substrates than the sialylated forms, platelets were treated with rADAM17 in the presence or absence of DANA. Platelets treated with rADAM17 released 47% ± 6% and 18% ± 12% of their GPIbα and GPV (P < .05), respectively, but negligible amounts of their GPIX and αIIbβ3 (P > .05; Figure 6C). Receptor shedding by rADAM17 was completely prevented by DANA (Figure 6C). DANA did not inhibit rADAM17 activity (not shown). Addition of the MP inhibitor GM6001 to sialidase-treated platelets did not prevent β-galactose exposure (eg, loss of sialic acid; Figure 6E), but inhibited receptor shedding by rADAM17 (Figure 6D; P < .05). β-Galactose exposure induced by sialidase increased 7-fold in the presence of GM6001 and rADAM17 (Figure 6E), showing that GM6001 has no effect on sialidase activity but completely inhibits rADAM17 and endogenous MP function. Hence, the data show that desialylation of GPIbα and GPV is a probable prerequisite for ADAM17-mediated receptor shedding in the cold and supports the concept that ADAM17 cleavage of GPIbα depends on prior sialidase activation.

Desialylation of fresh Adam17ΔZn/ΔZn platelets results in rapid clearance

To show that desialylation alone is sufficient to cause platelet clearance, we treated Adam17ΔZn/ΔZn and Adam17+/+ platelets with sialidase and determined their survival times after transfusion. Importantly, after sialidase treatment, both Adam17ΔZn/ΔZn and Adam17+/+ platelets were rapidly cleared from the circulation of mice (Figure 7A). The slight increase in the rate of Adam17ΔZn/ΔZn platelet removal was consistent with their enhanced levels of desialylated VWFR on their surface compared with normal platelets (Figure 7A). β-Galactose exposure increased by ∼ 4.5-fold and 7-fold after sialidase treatment of Adam17+/+ and Adam17ΔZn/ΔZn platelets, respectively (Figure 7B). Enhanced lectin binding for Adam17ΔZn/ΔZn platelets after sialidase treatment (Figure 7B) is indicative of the prevention of GPIbα or GPV shedding (Figure 7C). Addition of DANA to sialidase-treated Adam17ΔZn/ΔZn and Adam17+/+ platelets completely prevented platelet clearance (not shown).

Sialidase-treated Adam17ΔZn/ΔZn platelets are rapidly cleared from the circulation. (A) CMFDA-labeled fresh room temperature Adam17+/+ and Adam17ΔZn/ΔZn platelets were treated with sialidase (5 mU/mL; filled symbols) or left untreated (open symbols) were infused intravenously into Adam17+/+ mice (108 platelets/10 g of body weight). Blood was drawn at the indicated time points, and the platelets were immediately analyzed by flow cytometry. Results are expressed as the mean percentage of CMFDA-labeled platelets ± SEM. The percentage of CMFDA-positive untreated Adam17+/+ platelets at 5 minutes after transfusion was set as 100%. Each point represents 4 mice; ***P < .001. Sialidase-treated Adam17+/+ and Adam17ΔZn/ΔZn were compared. (B) Flow cytometric analysis of terminal β-galactose on glycoproteins, as detected with ECL FITC-labeled lectin. Lectin binding to Adam17+/+ or Adam17ΔZn/ΔZn platelets treated or not with α2-3,6,8,9-sialidase. The ratio of mean fluorescence intensity binding to untreated Adam17+/+ platelets is shown. Histograms report the mean ± SEM of 3 separate experiments. *P < .05, **P < .01, and ***P < .001. (C) GPIbα, GPV, and αIIbβ3 surface expression was assessed by flow cytometry. Adam17+/+ (not shown) and Adam17ΔZn/ΔZn platelets were treated with sialidase (5 mU/mL; ■) or not (□). Results are expressed relative to the amount of GPIbα on Adam17ΔZn/ΔZn platelets (mean percentage of relative to control ± SEM; n = 3).

Sialidase-treated Adam17ΔZn/ΔZn platelets are rapidly cleared from the circulation. (A) CMFDA-labeled fresh room temperature Adam17+/+ and Adam17ΔZn/ΔZn platelets were treated with sialidase (5 mU/mL; filled symbols) or left untreated (open symbols) were infused intravenously into Adam17+/+ mice (108 platelets/10 g of body weight). Blood was drawn at the indicated time points, and the platelets were immediately analyzed by flow cytometry. Results are expressed as the mean percentage of CMFDA-labeled platelets ± SEM. The percentage of CMFDA-positive untreated Adam17+/+ platelets at 5 minutes after transfusion was set as 100%. Each point represents 4 mice; ***P < .001. Sialidase-treated Adam17+/+ and Adam17ΔZn/ΔZn were compared. (B) Flow cytometric analysis of terminal β-galactose on glycoproteins, as detected with ECL FITC-labeled lectin. Lectin binding to Adam17+/+ or Adam17ΔZn/ΔZn platelets treated or not with α2-3,6,8,9-sialidase. The ratio of mean fluorescence intensity binding to untreated Adam17+/+ platelets is shown. Histograms report the mean ± SEM of 3 separate experiments. *P < .05, **P < .01, and ***P < .001. (C) GPIbα, GPV, and αIIbβ3 surface expression was assessed by flow cytometry. Adam17+/+ (not shown) and Adam17ΔZn/ΔZn platelets were treated with sialidase (5 mU/mL; ■) or not (□). Results are expressed relative to the amount of GPIbα on Adam17ΔZn/ΔZn platelets (mean percentage of relative to control ± SEM; n = 3).

Discussion

We have now established that (1) desialylation initiates platelet clearance; (2) storage of platelets by refrigeration up-regulates Neu1, causing VWFR desialylation; and (3) sialidase inhibitors that prevent desialylation during refrigeration improve the survival of transfused refrigerated platelets. We have also clarified the relation between desialylation and MP-mediated shedding of GPIbα and GPV from refrigerated platelets. GPIbα and GPV desialylation promotes ADAM17-mediated hydrolysis to increase receptor shedding, despite the finding that platelet clearance is mediated by desialylation and does not require VWFR shedding. Our findings highlight the critical role of desialylation of platelet glycoproteins in regulating platelet circulation and the importance of preventing sialidase activity during platelet storage.

Refrigeration up-regulates Neu1 to the platelet surface

We traced the enhanced exposure of β-galactose moieties on refrigerated platelets to the up-regulation of sialidase activity. Neu1 activity is undetectable on resting platelets, but it is found after refrigeration (Figure 2; supplemental Figure 1) although it is not detectable in plasma. On the basis of immunostaining, Neu1 is stored with β-galactosidase inside platelets in a specialized compartment that has granule-like staining and both up-regulate together. Surface up-regulation of the Neu1-complex, which includes β-galactosidase, could explain the exposure of β-GlcNAc along with β-galactose residues after refrigeration.11 In other cells, Neu1 forms a high molecular weight complex with α-neuraminidase (sialidase), N-acetylaminogalacto-6-sulfate sulfatase, and serine carboxypepidase cathepsin A in lysosomes.25 Whether platelet Neu1 is present as a complete high molecular weight complex in secretory lysosomes, which could be exposed at the surface after refrigeration, remains to be determined. The finding that it shares its intracellular compartment with β-galactosidase and both enzymes are found on surface after refrigeration supports the idea that it is part of a glycosidase complex.

Inhibition of platelet-sialidase in the refrigerator preserves survivability

We reasoned that if desialylation causes platelet removal, efforts to diminish sialidase activity could facilitate platelet survival after being refrigerated. Hence, we added DANA to the storage solution and found that it significantly enhanced both platelet survival and recovery after refrigeration. As judged by lectin-binding assays, DANA reduced but did not completely prevent galactose exposure. Our inability to prevent all surface desialylation is expected for a competitive substrate inhibitor. The development of noncompetitive sialidase inhibitors is therefore the next step in our efforts to store platelets long term by refrigeration.

Platelet refrigeration induces MP-mediated GPIbα and GPV shedding

We show here that refrigerated platelet storage leads to ADAM17-mediated GPIbα and GPV shedding (Figure 4). Although we cannot exclude the activation of other sheddases, it appears that ADAM17 is the primary sheddase activated in refrigerated platelets. ADAM17 activity is downstream of p38 MAPK activation,8 and inhibition of both ADAM17 and p38 MAPK activities enhances the recovery of platelets stored at room temperature.4,8 GPIbα shedding is completely dependent on ADAM17, whereas GPV shedding involves other proteases. ADAM17 cleaves a GPV 82-kDa fragment from the platelet surface,7 different from the smaller 69-kDa fragment generated by thrombin,27 and refrigerated Adam17ΔZn/ΔZn platelets retained higher GPV surface expression than Adam17+/+ platelets, supporting the notion that ADAM17 participates in GPV proteolysis after refrigeration. GPV is released from refrigerated murine and human platelets as a 82-kDa subfragment in a process inhibited by GM6001, but only partially prevented in Adam17ΔZn/ΔZn platelets (Figures 3–4). GPV shedding is regulated by both ADAM10 and ADAM17, as well as by thrombin-dependent mechanisms.6,28 ADAM10 cleaves GPVI after incubation with agonists.6,28,29 However, GPVI was not shed from platelets after refrigeration and rewarming (Figure 3), suggesting that ADAM10 was not activated.

What is the purpose of sialidase-dependent VWFR shedding and how is the fate of desialylated glycoproteins, and hence, the platelet determined? We speculate that shedding of desialylated VWFR components helps maintain aging platelets in the circulation longer, at least for times when some platelet functionality remains. Many factors could affect the balance between platelet clearance and VWFR cleavage in blood or during storage. One of the most important is whether ADAM17 and the VWFR are spatially distinct on the platelet surface or near neighbors and whether clustering of VWFR, which occurs after refrigeration, alters the distribution. In vitro aging (storage) may be quite different from the process that occurs in flowing blood. Platelets are more concentrated in bags and subjected to different conditions and solutions. How the cleavage rate of desialylated GPIbα by ADAM17 in flowing blood affects the recognition and clearance of platelets in liver remains to be addressed. Further, it remains to be determined whether additional platelet receptors other than GPIbα become desialylated as platelets age. Other proteolytic events that occur to desialylated or nondesialylated receptors may also play a role in defining platelet senescence and clearance.

Clearly, the clearance system that detects desialylated glycoproteins is highly sensitive, removing platelets that have lost < 10% of their sialic acid. Because platelet survival is enhanced by intravenous DANA injections into WT mice (K.M.H., unpublished observations, August 25, 2007), it is probable that sialic acid is removed by sialidase activity as normal platelets circulate. We also demonstrated that isolated fresh platelets have receptors bearing terminal β-galactose, supporting the notion that sialic acid is removed from the platelet surface during circulation.30 Preferential cleavage of desialylated platelet VWFR, therefore, might preserve some hemostatic function in the platelets. Rapid removal, in this case, would also place a higher burden on the replenishment system.

Inhibition of MP-dependent VWFR complex shedding does not improve the survival of refrigerated platelets

Stored, refrigerated platelets are rapidly removed from the circulation of mice, even in the absence of receptor shedding (Figure 4). In fact, platelet recoveries after refrigeration were worse in the presence of ADAM17 inhibitors than those of untreated platelets. This correlates with increased terminal β-galactose in refrigerated platelets with chemically or genetically inactive ADAM17 (Figure 5). We and others have reported that platelet β-galactose residues serve as endogenous ligands for the hepatic Ashwell Morell receptor.10,31 Refrigerated platelets retaining more desialylated glycoproteins, including VWFR receptor, because of ADAM17 inhibition are probably rapidly cleared because they have greater β-galactose exposure density than refrigerated platelets alone. In support, Adam17ΔZn/ΔZn platelets treated with sialidase were cleared at a faster rate than control platelets when infused into WT mice (Figure 7). In this model, receptor shedding would diminish the in vivo clearance rate of platelets by removing those having exposed β-galactose moieties before their detection by clearing cells.

Platelet sialidase and MP cross talk

Our data show that a cross talk between sialidases, probably Neu1, and MPs, specifically ADAM17, regulates VWFR complex abundance on the platelet surface. Desialylation converts GPIbα and GPV into more-efficient substrates for ADAM17, because inhibition of sialidase activity diminished receptor shedding by rADAM17 on fresh platelets (Figure 6). The data show that GPIbα isolated from fresh platelets contains glycans lacking sialic acid,10 providing a probable desialylated substrate for recombinant and endogenous ADAM17, once the receptor is sufficiently desialylated. Importantly, inhibition of desialylation of fresh platelets with the use of the competitive sialidase inhibitor DANA completely preserved platelet clearance (Figure 1). The concept of a cross talk between sialidase and MP activities is not new, because a cross talk between Neu1 and matrix MP9 is essential for neurotrophin-induced Trk tyrosine kinase receptor activation and cellular signaling.16 ADAM17 cleaves human GPIbα between residues G464-V465, as determined with synthetic peptides spanning the region between the extracellular mucin domain and the tandem Cys residues involved in disulfide-bonding to GPIbβ.6 Thus, the ADAM17 cleavage site resides beneath the predicted GPIbα O-glycosylation sites within the “sialomucin region.” Whether desialylation of this particular region enhances GPIbα cleavage by ADAM17 needs to be investigated.

Refrigeration enhances GPIbα clustering on the platelet surface and leads to increased β-galactose exposure.10 Clustering may be important in the recognition of GPIbα by ADAM17 on previously refrigerated platelets. Not surprisingly, preservation of GPIbα and GPV on the platelet surface increases the density of β-galactose–terminated glycans and accelerates platelet clearance. Hydrolysis of the terminal sialic acid moieties from GPIbα glycans by sialidases is probable to initiate platelet recognition by asialoglycoprotein receptors on macrophages and hepatocytes. Therefore, it is not surprising that in vivo loss of sialic acid would influence platelet lifespan by the same mechanism.32 Platelets lose sialic acid during storage at room temperature,33 and sialic acid loss has been correlated with reduced platelet recovery and survival.10,31,34 It is tempting to speculate that platelets lose sialic acid from membrane glycoproteins during aging in the circulation by up-regulating surface sialidase activity. Enhanced exposure of β-galactose–terminated glycans by sialidases such as Neu1 may represent a physiologic trigger that initiates the clearance of senile blood cells.35,36

In conclusion, our findings support the idea that platelet sialidases are up-regulated during long-term storage after refrigeration and that it is the loss of these sialic acid caps on glycoproteins that target the platelets for removal. Sialidase activity, specifically Neu1, further regulates MP activity, although the exact mechanism of this stimulation remains to be determined. Inhibition of sialidase activity during refrigeration, and possibly during room temperature storage, therefore, may provide a simple and feasible method to improve platelet quality during storage.

An Inside Blood analysis of this article appears at the front of this issue.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Max Adelman, Sara Nayeb-Hashemi, and Robert William Abdu for excellent technical assistance. They also thank Dr Claes Dahlgren (University of Gothenburg, Sweden) for constructive discussions and helpful comments throughout this paper.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant PO1 HL056949, J.H.H. and K.M.H.; grants HL089224 and PO1 HL107146, K.M.H.; and grant HL094596, W.B.); The Pew Scholars Award (K.M.H.); Stichting Vrieden van de Bloedtransfusie and Stichting De Drie Lichten (A.J.G.J.); and Gothenburg University's Jubileumsfond Stipend (E.C.J.).

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: A.J.G.J. and E.C.J. designed and performed research, collected and analyzed data, interpreted results, and assisted in writing the paper; V.R., Q.P.L., and W.B. designed and performed research, collected and analyzed data, and interpreted results; W.B., S.M.C., D.D.W., U.H.v.A., and R.S. provided reagents, participated in discussions, and interpreted results; H.F. and J.H.H. designed research, interpreted results, and assisted in manuscript preparation; and. K.M.H. designed research, collected and analyzed data, interpreted results, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests. Some of the information in this study is part of patent applications filed by Brigham & Women's Hospital, and the intellectual property covered by those applications has been licensed to Velico Inc, of Beverly, MA.

The current affiliation for W.B. is Department of Biochemistry and Biochemistry and McAllister Heart Institute, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC. The current affiliation for E.C.J is Cancer and Hematology Division, The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute, Parkville, Australia.

Correspondence: Karin M. Hoffmeister, Translational Medicine Division, Brigham & Women's Hospital, 1 Blackfan Cir, Karp 6th Fl, Boston, MA 02115; e-mail: khoffmeister@rics.bwh.harvard.edu.

References

Author notes

A.J.G.J. and E.C.J. contributed equally to this study.