Abstract

Macrophages are key target cells for HIV-1. HIV-1BaL induced a subset of interferon-stimulated genes in monocyte-derived macrophages (MDMs), which differed from that in monocyte-derived dendritic cells and CD4 T cells, without inducing any interferons. Inhibition of type I interferon induction was mediated by HIV-1 inhibition of interferon-regulated factor (IRF3) nuclear translocation. In MDMs, viperin was the most up-regulated interferon-stimulated genes, and it significantly inhibited HIV-1 production. HIV-1 infection disrupted lipid rafts via viperin induction and redistributed viperin to CD81 compartments, the site of HIV-1 egress by budding in MDMs. Exogenous farnesol, which enhances membrane protein prenylation, reversed viperin-mediated inhibition of HIV-1 production. Mutagenesis analysis in transfected cell lines showed that the internal S-adenosyl methionine domains of viperin were essential for its antiviral activity. Thus viperin may contribute to persistent noncytopathic HIV-1 infection of macrophages and possibly to biologic differences with HIV-1–infected T cells.

Introduction

Macrophages act as a reservoir and source for dissemination of virus throughout the course of HIV-1 infection.1,2 They support persistent replication of HIV-1 and, in contrast to infected T cells, demonstrate lower viral productivity or “burst sizes.”3,4 Only some of the factors responsible for these biologic differences have been identified.5,6 The most recently discovered constitutive host factor is S-adenosyl methionine (SAM) HD1, antagonized by vpx, but this is expressed much more strongly in dendritic cells (DCs) than macrophages.7

The early detection of viral infection by the host innate immune defense that initiates the production of type I interferon, such as IFN-α and IFN-β, and the subsequent induction of interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) are important for a successful antiviral response.8 Hundreds to thousands of ISGs may be expressed in cells in response to IFN, and some of these ISGs are known to have direct antiviral action.9 The best characterized ISGs with antiviral action include myxoma resistance protein 1 (MX1), dsRNA-activated protein kinase R (PKR), 2′-5′oligoadenylate synthetase (OAS)/RNaseL, and interferon-induced 15-kDa protein (ISG15).10 However, the precise function of many ISGs and their full spectrum of action remain to be identified. Recently, an increasing number of viruses have been reported to directly induce ISGs independent of interferon stimulation via membrane Toll-like receptors or cytosolic retinoic acid-inducible gene 1 (RIGI)–like receptors.11,12 The importance of the innate host response to viral infection is highlighted by the fact that many viruses have developed mechanisms to evade the IFN system. Previously, lack of IFN secretion from HIV-1–infected monocyte-derived macrophages (MDMs) was observed,13–17 and recently HIV-1 infection was also shown to inhibit type 1 IFN expression in CD4 T cells18,19 and monocyte-derived DCs (MDDCs).20

In this study, we initially investigated the alteration in host gene expression after infection of MDMs with HIV-1BaL (HIV-1) compared with mock infection and chemically inactivated HIV (AT2-HIV-1). Significant induction of ISG mRNA expression by HIV-1 was detected in MDMs, MDDCs, and CD4 T cells, without detectable types I, II, (or III) IFN mRNA or proteins in cell-type specific patterns: there were major differences between CD4 T cells and MDMs but greater similarities between MDMs and MDDCs. Inhibition of IFN was mediated through inhibition of IRF3 nuclear translocation in MDMs.

The ISG viperin was the most significantly up-regulated gene to be directly induced by HIV-1 infection of MDMs but not in CD4 T cells and MDDCs. Viperin (virus inhibitory protein, endoplasmic reticulum–associated, IFN-inducible), also known as radical S-adenosyl methionine domain 2 (RSAD2), is an evolutionarily conserved type I ISG with documented antiviral activity against hepatitis C virus (HCV) and human cytomegalovirus.21–23 Here we demonstrate that viperin is directly induced by infectious, but not inactivated, HIV-1 and negatively regulates HIV-1 production by MDMs. In addition, coexpression of viperin with HIV-1 in HEK293T cells directly led to negative regulation of HIV-1 production and allowed determination of the molecular domains responsible for its antiviral activity. Thus, we propose that viperin, in combination with other ISGs expressed at lower levels, contributes to the relative resistance of macrophages to HIV-1-induced cell death and to the restricted replication of HIV-1 in MDMs compared with T cells.

Methods

Generation of MDMs, MDDCs, and T cells

Preparation of HIV-1BaL virus

Titres of 6 × 107 TCID50/mL of purified HIV-1 and AT2-HIV-1 were generated as described previously.24–26 Endotoxin levels were below detection (Limulus amebocyte lysate assay; Sigma-Aldrich) and were negative for TNF-α, IFN-α, and IFN-β by ELISA.

HIV-1, farnesol, geranylgeraniol, and IFN treatment of MDMs

MDMs were exposed to 0.3 to 3 μg/106 cells (corresponding to MOIs of 0.1-2) of HIV-1 or AT2-HIV-1 or to 500 U/mL IFN-α2β (PBL Biomedical Laboratories). Mock infections were performed using media only. Farnesol or geranylgeraniol (Sigma-Aldrich) added on day 3 postinfection (pi) at concentrations of 10μM were replenished every 3 days. Infection was assessed using ELISA, flow cytometry, and HIV LTR-gag quantification by quantitative PCR as described previously.24,26,27

Microarray hybridization

Measurement of gene expression by quantitative PCR

Total unamplified RNA was DNase I treated (Promega) and reverse transcribed using oligod(T) and superscript III (Invitrogen). The cDNA was subject to quantitative PCR using defined primers (Sigma-Aldrich) and SYBR Green (Invitrogen) as described previously.24

Immunostaining and immunofluorescence microscopy

Mock, HIV-1, or IFN-α–treated MDMs were labeled with mouse monoclonal antibody to viperin (provided by Dr Peter Cresswell, Yale University School of Medicine), anti–HIV-1 p24 antigen (KC57-FITC, Beckman Coulter), mouse monoclonal anti-CD81 (clone TAPA-1/JS-81, BD Biosciences PharMingen), rabbit polyclonal antidisulfide isomerase (Sigma-Aldrich) to stain for endoplasmic reticulum, rabbit polyclonal anti-trans golgi netwok (TGN38, Sigma-Aldrich), and mouse polyclonal anti-IRF3 (provided by Dr Michael Gale, Univerity of Washington). Lipid rafts were detected with the cholera toxin subunit B (CTB–Alexa Fluor-488, Invitrogen). Appropriate Ig controls were included to rule out nonspecific binding.

siRNA knockdown of viperin expression in HIV-1–infected MDMs

On day 3 pi, MDMs were washed twice with PBS before siRNA was added in serum free media at a concentration of 50nM, which is optimal for knockdown of viperin expression as assessed by quantitative PCR. MDMs were then incubated at 37°C, and after 5 hours 10% human AB serum was added to the cultures. Sequences for the human viperin siRNAs were as follows: 5′-GAGAAUACCUGGGCAAGUU-3′, 5′-UAGAGUCGCUUU-CAAGAUA-3′, 5′-GGAGUAAGGCUGAUCUGAA-3′, and 5′-GAAUUAUGGUGAGUAUUUG-3′. Sequences supplied for siRNA GAPDH (positive control) were as follows: 5′CAACGGAUUUGGUCGUAUU-3′, 5′-GACCUCAACUACAUGGUUU-3′, 5′-UGGUUUACAUGUUCCAAUA-3′, and 5′-GUCAACGGAUUUGGUCGUA-3′. Sequences supplied for the nontargeting siRNA (negative control) were as follows: 5′-UGGUUUACAUGUCGACUAA-3′, 5′-UGGUUUACAUGUUUUCUGA-3′, 5′-UGGUUUACAUGUUUUCCUA-3′, and 5′-UGGUUUACAUGUUGUGUGA-3′. All siRNAs were commercially acquired from Dharmacon.

Site-directed mutagenesis for the generation of S1 + S2 + S3 domain mutant

Wild-type (WT) viperin, deletion mutants, and SAM domain mutant plasmids (provided by Karla Helbig and Michael Beard) were constructed in pLNCX2 vector by PCR cloning using the HindIII and NotI sites, as described previously.23 Deletion mutants consisted of deleting 17, 33, 50, or 100 amino acids from the N- and C-termini of WT viperin. For the SAM (S) mutations, each S mutant was composed of several point mutations within the identical conserved S regions (see Figure 4A). To create the S1 + S2 + S3 domain mutant, mutagenesis PCR using the Quickchange Mutagenesis Kit (Strategene) was performed. S1 was used as a template with the S2 mutant forward and reverse primers (GGAAGCTGGTATGGAGAAGAACAACCAATCACAACAAAAGCCATTTCTTCAAGACCGGGGAG and CTCCCCGGTCTTGAAGAAATGGCTTTTGTTGTGATTGGTTGTTCTTCTCCATACCAGCTTCC, respectively) for the generation of the S1 + S2 mutant according to the manufacturer's instructions. After cloning and plasmid isolation, the S1 + S2 mutant was then sequenced to confirm that mutagenesis was successful. For the generation of the S1 + S2 + S3 mutant, newly generated S1 + S2 mutant was used as a template with the S3 mutant forward and reverse primers (GCCCAGCGTGAGCATCGTGGCCCTTGCAAGCCTGATCCGGGAG and CTCCCGGATCAGGCTTGCAAGGGCCACGATGCTCACGCTGGGC, respectively) as for the generation of S1 + S2.

Cotransfection of full-length HIV-1 and viperin cDNA into HEK293T

The full-length infectious pWT/BaL proviral HIV-1 DNA (National Institutes of Health [NIH] AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, contributed by Dr Bryan R. Cullen) and either viperin-pLNCX2 or the control parental pLNCX2 plasmid were cotransfected into human embryonic kidney 293T (HEK293T) cells using polyethylenimine in a 6-well plate, as described previously.28 For transfection, 3.3 μg of pBaL was added to each well and viperin was diluted 1:2, 1:3, 1:9, and 1:27. To control for the effects of pLNCX2 expression, pLNCX2 was included in parallel with matched HIV-1/viperin molar ratios. For subsequent cotransfection experiments of pBaL and WT viperin, deletion mutants, SAM domain mutant plasmids, or PLNCX2 vector, an equal molar ratio of HIV and viperin was used. After 48 hours after transfection, supernatants were harvested. To measure infectious virus release from HEK293T in the presence or absence of viperin expression, supernatants were used to inoculate TZM-bl cells (NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, contributed by John Kappes and Xiaoyun Wu), which have a Tat-dependent reporter gene β-galactosidase, which can be activated after HIV infection. At 48 to 72 hours pi (hpi), addition of 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-Gal) stains infected cells blue. Blue spots were then counted using an Elispot reader (Elispot 6.0 iSpot).

Results

Effects of HIV-1 on differential gene expression in MDMs

Hybridizations to microarrays were performed for comparison of the effects of HIV-1, AT2–HIV-1, and mock treatments on the transcriptome of MDMs as follows: HIV-1 and mock, AT2–HIV-1 and mock, HIV-1 and AT2–HIV-1, each at 2, 3, and 5 days after treatment. Differentially expressed genes were identified using Bayesian linear modeling29 and ranked using B values (the probability of a gene being differentially expressed). Almost all significant differences in differential gene expressions (B value > 0) were observed in the HIV-1 versus mock comparison, and over time the majority of changes were seen at 5 days after treatment (126 genes at day 5 vs 52 genes at day 3; Table 1).

Genes from the HIV-1 and AT2–HIV-1–treated MDMs on day 5 were functionally clustered using the DAVID annotation database, as described previously.30 At 5 days after treatment, clusters of genes with the highest proportion of altered expression for HIV-1 and AT2–HIV-1 hybridizations were classified as “IFN response” and “response to virus” (data not shown). By examining the gene lists for these 2 sets of comparative hybridizations, we identified a subset of ISGs that were up-regulated by HIV-1 compared with mock infection of MDMs (Table 2) and by HIV-1 compared AT2–HIV-1. AT2–HIV-1 did not induce any ISGs compared with mock (data not shown).

Comparison of MDMs, MDDCs, and T-cell gene expression stimulated by HIV-1 infection

Up-regulated genes involved in the IFN (and/or antiviral) response to infectious HIV at day 5 and other closely related genes were subjected to further downstream testing by quantitative PCR (Table 3). To compare the expression of these genes between T cells, MDMs, and MDDCs, gene expression was also assessed by quantitative PCR in HIV-1–infected CD4+ T cells, MDMs, and MDDCs with MOIs of 0.5, 1, and 2, respectively. The proportion of HIV-1–positive cells was 4.5% ± 0.4%, 9.2% ± 0.8%, and 14% ± 1.8% on days 1, 2, and 4 pi, respectively, for CD4 T cells, 13% ± 6%, 35% ± 9.2%, and 60% ± 13.2% on days 1, 2, and 4 pi, respectively for MDMs, and 10% ± 3% on day 2 pi for MDDCs. The MOI used to infect CD4 T cells was kept at 0.5 to avoid apoptosis induced at higher MOIs.31 All cell types were assessed for ISGs at 6, 24, and 48 hpi and additionally at 96 hpi for MDMs and T cells (Table 3). Because of differences in the proportion of infected cells, the pattern and ranking of gene expression in the individual cell type was considered more important than fold change. In general, the quantitative PCR results showed induction of ISG subsets in all cell types. ISG expression in CD4 T cells usually showed one of 2 kinetic patterns: (1) a peak at 6 to 24 hpi and then plateauing or declining; or (2) biphasic, peaking 48 and at 96 hpi (representing a second round of infection). However, in MDMs, ISG expression generally continued to rise to 96 hpi, consistent with the persistent noncytopathic pattern of HIV-1 infection in this cell type.

In MDMs, viperin was by far the most up-regulated gene by HIV-1, to a much greater degree than in CD4 T cells or MDDCs. Thus, viperin ranked first in MDMs, but ninth in MDDCs and seventh in CD4 T cells. The well-characterized antiviral ISGs (ISG15, MX1, and OAS1–3 ) and PKR10 were also up-regulated in all cell types by HIV-1 but not to the same degree as viperin. Comparing MDMs and MDDCs, the pattern of expression of other ISGs with potential antiviral activity32,33 was similar: IFIT3 and IFITM1 were the most highly expressed of these genes followed by MX1 and ISG15. Comparing MDMs and CD4 T cells, IFIT1, IFIT2, and IFIT3 expression was markedly increased in both, but IFITM1 was more markedly increased in MDMs (ranked 3 at 96 hpi) than in CD4 T cells (ranked 7 at 6 hpi but declining thereafter; Table 3).

HIV-1 inhibited type I IFN induction in MDMs

Because IFNs can induce viperin expression,22 we next examined whether HIV-1 infection of MDMs induced viperin directly or secondary to IFN induction. The mRNA levels of IFN-α, IFN-β, IFN-γ, and the type III IFNs (IFN-ω, IL-28a, IL28b, and IL-29) were assessed by quantitative PCR in mock, AT2-HIV-1, and HIV-1–treated MDMs. There was no enhancement of IFN-α, IFN-β, IFN-γ, IFN-ω, IL-28, or IL-29 gene expression. In addition, IFN-α and IFN-β proteins were not detected in supernatants (Figure 1A).

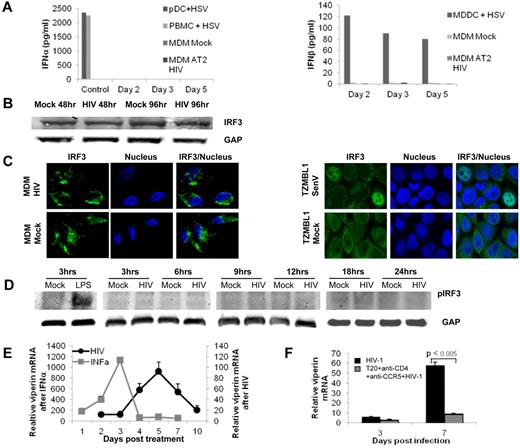

HIV-1 infection specifically induces viperin in MDMs without IFN induction. (A) HIV-1 infection of MDMs does not induce type 1 IFN. MDMs were treated with HIV-1 or AT2–HIV-1. IFN-α and IFN-β levels in the supernatants were determined by ELISA (R&D Systems). As a positive control for IFN induction, PBMCs and plasmacytoid DCs (IFN-α) or MDDCs (IFN-β) were treated with HSV-2186. Data are representative of 3 experiments. (B) HIV-1 infection does not degrade IRF3. A representative Western blot of IRF-3 expression in MDMs on days 2 and 4 after treatment with HIV-1 at an MOI of 1 compared with mock treatment using an anti-IRF3 and GAPDH antibodies. (C) HIV-1 inhibits IRF3 translocation from cytoplasm to nucleus. IRF3 cellular localization was examined in mock- and HIV-1–treated MDMs at 48 hours. TZM-bl cells infected with Sendai virus were used as a positive control for the nuclear IRF3 translocation. Fluorescently labeled cells were visualized with an inverted Olympus IX-70 microscope (DeltaVision Image Restoration Microscope; Applied Precision/Olympus) using a numerical aperture oil immersion lens (1.4 or 1.43) and a photo-metrics CoolSnap QE camera. The representative z-series were deconvoluted, the pictures overlaid; colocalization and significance were performed using SoftWoRx software (Version 3.4.5; Universal Imaging Corporation) as described previously.28 Images shown are representative of n = 20 cells. (D) HIV-1 does not lead to phosphorylation of IRF3. A representative Western blot of phospho-IRF-3 expression in MDMs after 3, 6, 9, 12, 18, and 24 hours after treatment with HIV-1 at an MOI of 1 compared with lipopolysaccharide stimulated (1 μg/mL) MDMs using antiphospho-IRF3 and GAPDH antibodies. (E) Kinetics of mRNA viperin induction by HIV-1 compared with IFN-α. MDMs were treated with either HIV-1 at an MOI of 0.25 or IFN-α/2β (500 U/mL). RNA was extracted at different time points, reverse transcribed, and viperin mRNA expression was assessed by quantitative PCR relative to GAPDH. The mean data from 3 experiments are shown with SE bars. (F) Inhibitors of HIV-1 binding, fusion, and entry inhibit viperin expression in MDMs. MDMs were either infected with HIV-1 only or treated with a combination of the fusion inhibitor T20 (1 mg/mL), soluble recombinant CD4 (NIH), and the anti-CCR5 (CD195, BD Biosciences PharMingen) antibodies at 20 μg/mL each, then infected. Total RNA was harvested, and viperin expression was measured by quantitative PCR relative to GAPDH. The mean data from 3 experiments are shown with SE bars.

HIV-1 infection specifically induces viperin in MDMs without IFN induction. (A) HIV-1 infection of MDMs does not induce type 1 IFN. MDMs were treated with HIV-1 or AT2–HIV-1. IFN-α and IFN-β levels in the supernatants were determined by ELISA (R&D Systems). As a positive control for IFN induction, PBMCs and plasmacytoid DCs (IFN-α) or MDDCs (IFN-β) were treated with HSV-2186. Data are representative of 3 experiments. (B) HIV-1 infection does not degrade IRF3. A representative Western blot of IRF-3 expression in MDMs on days 2 and 4 after treatment with HIV-1 at an MOI of 1 compared with mock treatment using an anti-IRF3 and GAPDH antibodies. (C) HIV-1 inhibits IRF3 translocation from cytoplasm to nucleus. IRF3 cellular localization was examined in mock- and HIV-1–treated MDMs at 48 hours. TZM-bl cells infected with Sendai virus were used as a positive control for the nuclear IRF3 translocation. Fluorescently labeled cells were visualized with an inverted Olympus IX-70 microscope (DeltaVision Image Restoration Microscope; Applied Precision/Olympus) using a numerical aperture oil immersion lens (1.4 or 1.43) and a photo-metrics CoolSnap QE camera. The representative z-series were deconvoluted, the pictures overlaid; colocalization and significance were performed using SoftWoRx software (Version 3.4.5; Universal Imaging Corporation) as described previously.28 Images shown are representative of n = 20 cells. (D) HIV-1 does not lead to phosphorylation of IRF3. A representative Western blot of phospho-IRF-3 expression in MDMs after 3, 6, 9, 12, 18, and 24 hours after treatment with HIV-1 at an MOI of 1 compared with lipopolysaccharide stimulated (1 μg/mL) MDMs using antiphospho-IRF3 and GAPDH antibodies. (E) Kinetics of mRNA viperin induction by HIV-1 compared with IFN-α. MDMs were treated with either HIV-1 at an MOI of 0.25 or IFN-α/2β (500 U/mL). RNA was extracted at different time points, reverse transcribed, and viperin mRNA expression was assessed by quantitative PCR relative to GAPDH. The mean data from 3 experiments are shown with SE bars. (F) Inhibitors of HIV-1 binding, fusion, and entry inhibit viperin expression in MDMs. MDMs were either infected with HIV-1 only or treated with a combination of the fusion inhibitor T20 (1 mg/mL), soluble recombinant CD4 (NIH), and the anti-CCR5 (CD195, BD Biosciences PharMingen) antibodies at 20 μg/mL each, then infected. Total RNA was harvested, and viperin expression was measured by quantitative PCR relative to GAPDH. The mean data from 3 experiments are shown with SE bars.

IRF3 is potent inducer of IFNs. To determine whether HIV-1 inhibits IFN induction by interfering with IRF3 function, either via its degradation as observed in T cells18,19 or by its failure to translocate to the nucleus as in MDDCs,20 IRF3 expression at the protein level was examined by Western blot in HIV-1– and mock-infected MDMs at 48 and 96 hpi. Because no reduction in IRF3 levels was observed after infection (Figure 1B), nuclear translocation of IRF3 was subsequently examined at 6, 24, 48, and 96 hpi. No colocalization of IRF3 with the nucleus was observed (Figure 1C) at any time points. However, when TZM-bl cells were infected with control Sendai virus, which induces interferon production, IRF3 was shown to translocate to the nucleus (Figure 1C). Because IRF3 translocation to the nucleus is dependent on its prior phosphorylation, we have also examined whether IRF-3 is phosphorylated in HIV- or lipopolysaccharide-treated MDMs. IRF3 was phosphorylated in lipopolysaccharide-treated MDMs after 3 hours; however, no phosphorylation was observed in MDMs treated with HIV at multiple time points between 3 and 24 hours (Figure 1D). Therefore, failure of IRF3 to translocate to the nucleus, where it binds to the IFN promoter region to produce IFN, rather than its degradation, is responsible for HIV-1 inhibition of IFN induction in MDMs.

Effect of HIV-1 on expression of genes involved in regulating viperin and IFN

Because no type I or type II IFNs were induced by HIV-infected MDMs, the viral effect on other pathways of ISG induction via key IRFs and the RNA helicases MDA-5 and RIGI12 was examined.

There was a marked increased in the expression of RIGI and MDA5 in all 3 cell types, but the patterns differed over time in MDMs and MDDCs compared with CD4 T cells. mRNA levels for both genes in MDMs and MDDCs increased over time. However, in CD4 T cells, MDA5 expression plateaued and RIGI expression declined after 6 hpi (Table 3). IRF3, which is constitutively expressed, showed little change in all cell types. IRF7 (known to stimulate IFN production) and IRF1 (known to induce ISGs in the absence of IFN) were also increased at 24 to 48 hpi in all cell types. The potentially inhibitory IRFs (2, 4, and 8) differed in their pattern of expression between cell types, with IRF2 and IRF8 increasing in MDMs and MDDCs but not in T cells. However, IRF4 was markedly increased in CD4 T cells (Table 3).

Induction of viperin in MDMs treated with HIV-1 and IFN-α

To assess the level and the kinetics of viperin mRNA induction by quantitative PCR, MDMs were infected with HIV-1 at different MOIs or mock infected over 10 days. Uninfected MDMs showed undetectable viperin RNA expression. Viperin was detected at 6 to 24 hpi with an HIV MOI of 2, at 2 to 3 days pi with an MOI of 0.25 and at 4 days pi with MOI 0.1, with peak levels at 5 days pi for MOIs of 2 and 0.25 and 7 days pi for an MOI of 0.1. There was a 60-fold difference in peak viperin mRNA levels induced by MOIs of 0.25 and 2 (Figures 1E and 2D). The levels of viperin induction corresponded with the proportion of infected MDMs as measured by intracellular p24 staining by flow cytometry. This indicates that the kinetics and levels of viperin induction were dependent on the size of the HIV-1 inoculum, with the most concentrated preparations of HIV-1 inducing viperin at earlier time points and peaking at higher levels. In addition, IFN-α treatment of MDMs used as a positive control for assessing viperin up-regulation occurred both earlier (8 hours) and at a higher magnitude compared with that of HIV-1 infection with an MOI of 0.25 (Figure 1E).

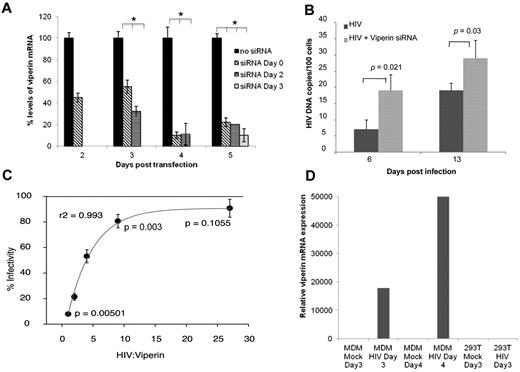

Viperin has direct antiviral activity against HIV-1 in MDMs and other cells. (A) Time of siRNA addition for optimal knockdown of viperin in MDMs. MDMs infected with HIV-1 were transfected using lipofectamine RNAiMAX with siRNA specific to viperin on days 0, 2, and 3 pi. Viperin mRNA expression was then measured on days 2, 3, 4, and 5 after transfection. Data are percentage levels of viperin mRNA after siRNA-treated and nontreated HIV-1–infected MDMs (the no siRNA result was standardized to 100%). (B) Knockdown of viperin in MDMs enhances HIV-1 DNA expression. DNA was extracted on days 6 and 13 from infected MDMs (MOI = 0.25) treated with specific siRNA to viperin (HIV + viperin siRNA) or not (HIV) on day 3 pi. HIV LTR-gag was quantified by quantitative PCR. The mean data from 3 experiments are shown with SE bars. (C) Viperin exerts dose-dependent inhibition of viral production. HEK293T cells were cotransfected with 3.3 μg of the pWT/BaL proviral HIV-1 DNA and either plasmids encoding WT viperin or the control parental vector pLNCX2 at the same molar ratio of HIV or with decreasing ratio of 1:2, 1:3, 1:9, and 1:27. After 48 hours, supernatants were harvested and assayed for virus release by serial dilutions on TZM-bl indicator cells. Infected TZM-bls were stained blue after the addition of X-Gal and were counted using an Elispot reader. The mean data from 3 experiments are shown with SE bars. (D) Viperin is not induced by HIV-1 in HEK293T cells. HEK293T were transfected with pHEF-VsV-g (NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, contributed by Dr Lung-Ji Chang) and pWT/BaL proviral HIV-1 DNA plasmid using polyethylenimine to generate VsV-g pseudotyped pBaL to induce a very high level of infectivity within the cell sheet or mock transfected for 3 days. As a positive control, MDMs were exposed to high levels of HIV-1 (MOI 2) or mock infected for 3 and 4 days. Viperin mRNA expression was determined by quantitative PCR relative to GAPDH.

Viperin has direct antiviral activity against HIV-1 in MDMs and other cells. (A) Time of siRNA addition for optimal knockdown of viperin in MDMs. MDMs infected with HIV-1 were transfected using lipofectamine RNAiMAX with siRNA specific to viperin on days 0, 2, and 3 pi. Viperin mRNA expression was then measured on days 2, 3, 4, and 5 after transfection. Data are percentage levels of viperin mRNA after siRNA-treated and nontreated HIV-1–infected MDMs (the no siRNA result was standardized to 100%). (B) Knockdown of viperin in MDMs enhances HIV-1 DNA expression. DNA was extracted on days 6 and 13 from infected MDMs (MOI = 0.25) treated with specific siRNA to viperin (HIV + viperin siRNA) or not (HIV) on day 3 pi. HIV LTR-gag was quantified by quantitative PCR. The mean data from 3 experiments are shown with SE bars. (C) Viperin exerts dose-dependent inhibition of viral production. HEK293T cells were cotransfected with 3.3 μg of the pWT/BaL proviral HIV-1 DNA and either plasmids encoding WT viperin or the control parental vector pLNCX2 at the same molar ratio of HIV or with decreasing ratio of 1:2, 1:3, 1:9, and 1:27. After 48 hours, supernatants were harvested and assayed for virus release by serial dilutions on TZM-bl indicator cells. Infected TZM-bls were stained blue after the addition of X-Gal and were counted using an Elispot reader. The mean data from 3 experiments are shown with SE bars. (D) Viperin is not induced by HIV-1 in HEK293T cells. HEK293T were transfected with pHEF-VsV-g (NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, contributed by Dr Lung-Ji Chang) and pWT/BaL proviral HIV-1 DNA plasmid using polyethylenimine to generate VsV-g pseudotyped pBaL to induce a very high level of infectivity within the cell sheet or mock transfected for 3 days. As a positive control, MDMs were exposed to high levels of HIV-1 (MOI 2) or mock infected for 3 and 4 days. Viperin mRNA expression was determined by quantitative PCR relative to GAPDH.

Effects of T20 and soluble CD4 and CCR5 antibodies on viperin expression

To confirm the specificity of viperin induction by HIV in the inoculums, we investigated the effect of inhibiting HIV-1 binding, entry, and replication on viperin expression through the use of a combination of HIV-1 entry inhibitors, including the fusion inhibitor T20 and soluble CD4 and CCR5 antibodies. Both HIV-1 (data not shown) and viperin cDNA levels (Figure 1F) were significantly inhibited by the combination of entry blockers, confirming that viperin is specifically induced by HIV-1 after binding to CD4/CCR5, entry, and viral replication.

SiRNA knockout of viperin leads to increased HIV-1 replication

To investigate the potential role that viperin plays in HIV-1 replication, we tested the effect of siRNA knockdown of viperin on HIV-1 production. Because viperin expression was maximal on day 5 pi, we first investigated the optimal time points for maximal knockdown of viperin by day 5 pi by adding siRNA to viperin at 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4 days pi. Maximal reduction in the level of viperin mRNA (at 95%) was achieved on day 5 pi when the siRNA was added on day 3 pi (Figure 2A).

After siRNA treatment of MDMs on day 3 pi, HIV-1 DNA levels were measured by quantitative PCR. By 6 days pi, there was a significant 40% increase (P = .021) in HIV-1 cDNA levels in siRNA-transfected MDMs (HIV+viperin siRNA) compared with nontransfected MDMs (HIV), and this significant difference persisted to 13 days pi (∼ 30% increase P = .03; Figure 2B). Thus, viperin acts as an endogenous antiviral factor, and its specific knockdown leads to an increase in HIV-1 cDNA within the infected MDM culture.

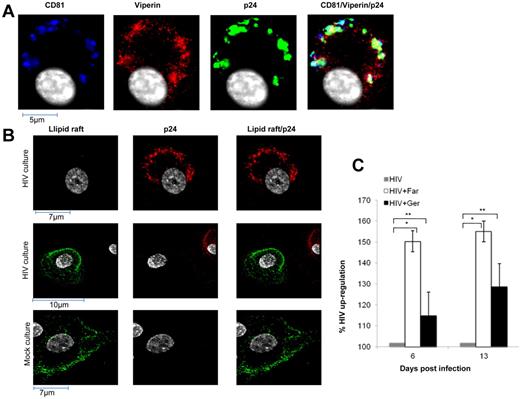

Distribution of viperin after IFN and HIV-1 treatment of MDMs

To determine the site of anti–HIV-1 action of viperin, the intracellular distribution of viperin was examined in HIV-1– and IFN-α–treated MDMs separately. After IFN-α stimulation for 5 days, viperin was expressed diffusely in the cytoplasm, colocalizing with the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), consistent with previous data in other cell types,21 (supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). However, infection of MDMs with HIV-1 for 5 days redistributed viperin away from the ER into foci, which significantly colocalized with p24 antigen (r = 0.59), a marker for de novo replication of HIV-1, and with CD81 (r = 0.64), a marker for the site of HIV-1 assembly/accumulation within tetraspanin-rich domains in MDMs34 (Figure 3A), but not with markers for ER or the trans Golgi network (data not shown).

Mechanism of viperin action in MDMs. (A) HIV-1 alters viperin distribution in infected MDMs. Five days pi, mock- and HIV-1–treated MDMs were fixed in 3% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.05% Triton-X, and labeled for viperin (red), p24 (green), CD81 (blue), and nucleus (white). Images shown are representative of n = 10 cells and were acquired as described in Figure 1C. (B) HIV-1 infection of MDMs disperses lipid rafts. Five days pi, mock- and HIV-1–treated MDMs were immunostained with the lipid raft marker CTB–Alexa Fluor-488 (lipid raft, green), fixed in 3% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.05% Triton-X, and then labeled with anti-p24 antibody (red). Top and middle panels: HIV-1-treated culture. Top panels: Infected cell. Middle panels: In addition to the infected cell (red), a noninfected cell (no red staining; as only a small proportion of cells are infected). Therefore, in the right middle panel, which shows merged images, it is clear that the infected cell (p24 antigen-positive) has lost its lipid raft staining. Bottom panel: Noninfected cell in a mock-treated culture. Images shown are representative of n = 10 cells and were acquired as described in Figure 1C. (C) Farnesol stimulates HIV-1 production by HIV-1–infected MDMs to a greater degree than geranylgeraniol. MDMs were infected with HIV-1 (MOI = 0.5) for 3 days and were then either treated with farnesol or geranylgeraniol (10μM) or mock treated. At the indicated times point after infection, HIV-1 DNA was quantified by quantitative PCR. Levels of HIV-1 DNA are presented as percentage of up-regulation after farnesol or geranylgeraniol treatment, compared with mock-treated HIV-1–infected cultures (set at 100%). The mean data from 3 experiments are shown with SE bars. *P < .05 (paired t test). **P > .3 (paired t test).

Mechanism of viperin action in MDMs. (A) HIV-1 alters viperin distribution in infected MDMs. Five days pi, mock- and HIV-1–treated MDMs were fixed in 3% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.05% Triton-X, and labeled for viperin (red), p24 (green), CD81 (blue), and nucleus (white). Images shown are representative of n = 10 cells and were acquired as described in Figure 1C. (B) HIV-1 infection of MDMs disperses lipid rafts. Five days pi, mock- and HIV-1–treated MDMs were immunostained with the lipid raft marker CTB–Alexa Fluor-488 (lipid raft, green), fixed in 3% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.05% Triton-X, and then labeled with anti-p24 antibody (red). Top and middle panels: HIV-1-treated culture. Top panels: Infected cell. Middle panels: In addition to the infected cell (red), a noninfected cell (no red staining; as only a small proportion of cells are infected). Therefore, in the right middle panel, which shows merged images, it is clear that the infected cell (p24 antigen-positive) has lost its lipid raft staining. Bottom panel: Noninfected cell in a mock-treated culture. Images shown are representative of n = 10 cells and were acquired as described in Figure 1C. (C) Farnesol stimulates HIV-1 production by HIV-1–infected MDMs to a greater degree than geranylgeraniol. MDMs were infected with HIV-1 (MOI = 0.5) for 3 days and were then either treated with farnesol or geranylgeraniol (10μM) or mock treated. At the indicated times point after infection, HIV-1 DNA was quantified by quantitative PCR. Levels of HIV-1 DNA are presented as percentage of up-regulation after farnesol or geranylgeraniol treatment, compared with mock-treated HIV-1–infected cultures (set at 100%). The mean data from 3 experiments are shown with SE bars. *P < .05 (paired t test). **P > .3 (paired t test).

HIV-1 treatment of MDMs disperses lipid rafts

Lipid rafts are important in HIV-1 entry35 and also in budding from the tetraspanin-rich compartments of MDMs. Immunolabeling of lipid rafts with the cholera toxin B in HIV-1–infected MDMs on day 5 pi showed a complete loss of lipid rafts but not in uninfected cells, suggesting that they were dispersed by HIV-induced viperin (Figure 3B), similar to the effect of viperin on influenza.36

Farnesol reverses viperin-mediated inhibition of HIV-1 replication in MDMs

Farnesyl diphosphate synthase (FPPS) is a key enzyme in the synthesis of FPP, which is a precursor of cholesterol, farnesylated and geranylated proteins.37 Cholesterol is an important component of lipid rafts. In influenza virus infection of murine macrophages, viperin prevented prenylation of cell membrane proteins by interacting with the enzyme FPPS and thus inhibited influenza budding from the plasma membrane.36 As exogenous farnesol inhibited this interaction and restored influenza viral egress, the effect of farnesol on HIV-1–infected MDMs was examined. When farnesol was added on day 3 pi, significant enhancement of HIV-1 cDNA levels by 50% was observed at days 6 to 13 pi (P = .0049 and .023, respectively), indicating reversal of viperin-mediated inhibition via FPPS (Figure 3C). In contrast, inhibition by geranylgeraniol, which can reverse viperin-mediated inhibition of HCV replication,38 was insignificant.

Viperin-specific inhibition of HIV-1 production in HEK293T cells

HEK293T cells were used for transfection studies to evaluate the effect of viperin on HIV-1 production from an infectious molecular clone cotransfected in trans. Neither mock nor HIV-1–transfected HEK293T cells expressed viperin (Figure 2D) or other ISGs (data not shown). Using a pLNCX2 based viperin expression vector, WT viperin was coexpressed in trans with pWT/BaL proviral HIV-1 DNA in HEK293T, with expression confirmed by flow cytometry. The proportion of viperin and HIV-1–cotransfected cells exceeded 50%, with viperin transfection alone exceeding 70%. Expression of viperin in trans with HIV-1 resulted in release of significantly lower levels of infectious viral progeny relative to the pLNCX2 parental vector control, as measured using the TZM-bl indicator cell line (Figure 2C). Furthermore, viperin expression levels inversely correlated with HIV-1 production, when decreasing molar ratios of viperin plasmid to HIV-1 were used (Figure 2C; r2 = 0.993). HIV-1 to viperin ratios of less than 10 resulted in a significant decrease in viral output (Figure 2C; P = .003). These results demonstrate that isolated viperin expression in HEK293T cells inhibits HIV-1 production.

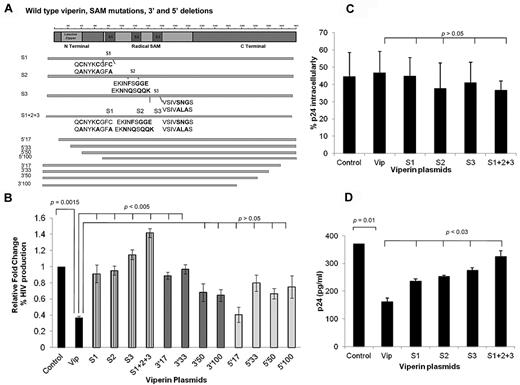

Mutation of the SAM domains reversed viperin-mediated inhibition of HIV-1 production from HEK293T cells

Plasmids encoding pLNCX2 vector (control), WT viperin, and viperin mutants carrying serial 5′ or 3′ truncations or SAM (S) functional mutations (Figure 4A) were cotransfected into HEK293T cells together with the pWT/BaL proviral HIV-1 DNA. As shown earlier, WT viperin significantly inhibited infectious HIV-1 production (P = .0015), but this inhibition was significantly reversed with all SAM mutants, with the most marked effect observed with the S1 + S2 + S3 mutant as measured in the TZM-bl indicator cell line (P < .005; Figure 4B). There was also a significant loss of inhibition with the short 3′Δ17 and 3′Δ33 mutants but not with the longer truncations 3′Δ50 and 3′Δ100. The panel of 5′ truncation mutants showed no significant reversal, suggesting that the N-terminal domains are not essential for viperin activity. The effects of the SAM mutants were not the result of poor expression, as WT viperin and its mutants in transfected HEK293T were expressed similarly by Western blot using GAPDH as a standard (data not shown).

SAM mutants increased HIV-1 production in HEK293T. (A) Schematic structure of the viperin protein showing N- and C-terminal truncations and SAM domain mutants. (B-D) HEK293T were cotransfected with pWT/BaL proviral HIV-1 DNA and a panel of either WT viperin or SAM mutants (S1, S2, S3, S1 + S2 + S3; individually) or 5′ or 3′ truncation mutants (5′17, 5′33, 5′50, 5′100, 3′17, 3′33, 3′50, 3′100; individually) or plasmid control (pLNCX2 vector). (B) SAM domain mutations significantly reverse viperin inhibition of HIV-1. Viral production was quantified on TZM-bl as in Figure 2C. Histograms show relative fold changes in the percentage of HIV-1 infection, which is indicative of HIV production from the HEK293T cells. The mean data from 3 experiments are shown with SE bars. (C) WT viperin and SAM mutants do not diminish the proportion of HIV-1–infected cells. After 48 to 72 hours after transfection, staining for intracellular p24 was performed. The percentage of intracellular p24 cells was determined by gating against non-pBaL–transfected cultures by flow cytometry. The mean data from 4 experiments are shown with SE bars. (D) SAM domain mutants up-regulate total extracellular p24 released in the culture supernatants compared with WT viperin. Supernatants from HEK293T cell cotransfectants were collected at 72 hours after transfection, and levels of extracellular virus were quantified by p24 ELISA (XpressBio) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The mean data from 4 experiments are shown with SE bars.

SAM mutants increased HIV-1 production in HEK293T. (A) Schematic structure of the viperin protein showing N- and C-terminal truncations and SAM domain mutants. (B-D) HEK293T were cotransfected with pWT/BaL proviral HIV-1 DNA and a panel of either WT viperin or SAM mutants (S1, S2, S3, S1 + S2 + S3; individually) or 5′ or 3′ truncation mutants (5′17, 5′33, 5′50, 5′100, 3′17, 3′33, 3′50, 3′100; individually) or plasmid control (pLNCX2 vector). (B) SAM domain mutations significantly reverse viperin inhibition of HIV-1. Viral production was quantified on TZM-bl as in Figure 2C. Histograms show relative fold changes in the percentage of HIV-1 infection, which is indicative of HIV production from the HEK293T cells. The mean data from 3 experiments are shown with SE bars. (C) WT viperin and SAM mutants do not diminish the proportion of HIV-1–infected cells. After 48 to 72 hours after transfection, staining for intracellular p24 was performed. The percentage of intracellular p24 cells was determined by gating against non-pBaL–transfected cultures by flow cytometry. The mean data from 4 experiments are shown with SE bars. (D) SAM domain mutants up-regulate total extracellular p24 released in the culture supernatants compared with WT viperin. Supernatants from HEK293T cell cotransfectants were collected at 72 hours after transfection, and levels of extracellular virus were quantified by p24 ELISA (XpressBio) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The mean data from 4 experiments are shown with SE bars.

Mechanism of viperin suppression of HIV-1 production

Next, the mechanism of reversal of viperin-mediated inhibition of HIV-1 production by mutations within the SAM domains was investigated. Transfected HEK293T cells were harvested 48 to 72 hours after transfection and analyzed for intracellular p24 expression by flow cytometry to determine the proportion of p24-positive cells. The results showed that the proportion of p24-expressing cells was not significantly inhibited in cells that were transfected with WT viperin, the SAM domain mutants (P > .05), or the control vector pLNCX2. This indicates that viperin and the SAM domain mutants do not affect the expression of intracellular p24 (Figure 4C). However, when extracellular p24 levels were measured in viral supernatants by HIV-1 p24 ELISA, p24 levels were markedly reduced in cells transfected with WT viperin but not with the SAM domain mutants (Figure 4D), indicating that SAM mutations are responsible for the prevention of HIV-1 particle egress from HEK293T cells.

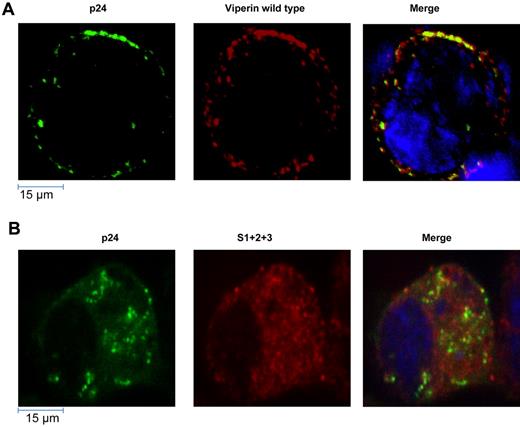

Loss of colocalization of HIV-1 and viperin with the S1 + S2 + S3 mutant

As mutations in all 3 SAM domains contributed to viperin inhibition, the localization of the S1 + S2 + S3 mutant protein in relation to HIV-1 was examined. HEK293T cells were cotransfected with HIV-1 proviral DNA and either WT viperin (Figure 5A) or the S1 + S2 + S3 mutant (Figure 5B) for 48 to 72 hours, and then immunostained for p24 and viperin. There was a strong colocalization (r = 0.71) of HIV-1 p24 antigen and WT viperin at the cell surface and in subjacent domains. However, this colocalization was lost when the S1 + S2 + S3 mutant was cotransfected with HIV-1 (Figure 5B). Thus, mutation of the SAM domains eliminates the inhibitory effect of viperin by failure to associate with HIV-1 at its site of egress rather than just a local enzymatic effect.

Intracellular distribution of HIV-1 and WT viperin or mutants in HEK293T cells. HEK293T cell were cotransfected with pWT/BaL proviral HIV-1 DNA and either WT viperin (A) or S1 + S2 + S3 domain mutants (B) for 72 hours. They were then fixed in 3% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.05% Triton-X, and labeled for viperin (red), p24 (green), and nucleus (blue). Images shown are representative of n = 10 cells and were acquired as described in Figure 1C.

Intracellular distribution of HIV-1 and WT viperin or mutants in HEK293T cells. HEK293T cell were cotransfected with pWT/BaL proviral HIV-1 DNA and either WT viperin (A) or S1 + S2 + S3 domain mutants (B) for 72 hours. They were then fixed in 3% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.05% Triton-X, and labeled for viperin (red), p24 (green), and nucleus (blue). Images shown are representative of n = 10 cells and were acquired as described in Figure 1C.

Discussion

The experiments described here reveal that infection of human MDMs with HIV led to the induction of a subset of ISGs, with maximal expression at 5 days pi. in the absence of IFN induction. No type I, II, or III IFN mRNA or type I IFN proteins were detected in cells or supernatants, respectively. HIV was also previously reported to inhibit IFN production via effects on IRF3 in DCs and T cells, but the mechanism of inhibition was different between the 2 cell types. In MDDCs, HIV-1 infection inhibited IRF3 translocation to the nucleus, whereas in T cells IRF3 was degraded.18–20 Our results suggest that the mechanism in MDMs is similar to that in DCs because cytoplasmic IRF3 did not translocate into the nucleus of HIV infected MDDMs. Furthermore, IFN-independent expression of ISGs in MDMs was only observed in HIV-infected cells and not in AT2-HIV–treated cells. Because AT2-HIV binds and enters cells but does not undergo reverse transcription, this suggests that HIV genomic RNA or reverse-transcribed cDNA in the cytoplasm of infected cells may be the cause of ISG induction rather than viral binding to cell surface receptors or entry.

The most significantly up-regulated ISG by HIV was as viperin. Viperin expression was inhibited with a combination of inhibitors that blocked CD4/CCR5-mediated binding and fusion (T20) of the virus, ruling out the possibility that potential contaminants, such as microvesicles or cytokines in the viral inocula, were causing this effect. HIV-1 induction of ISGs, including viperin, has been previously identified by microarray studies in MDMs,17,39 but the role that these genes play in modulating infection of MDMs was not investigated. Here we have shown that, although viperin was induced early at significant levels in MDMs in response to IFN-α stimulation, the magnitude and rapidity of viperin expression after infection correlated with the MOI of HIV used, which determines the rate of viral spread through the MDM culture. Viperin remained the most up-regulated ISG at all MOIs. Viperin is also induced in direct response to several other RNA and DNA viruses38,40,41 in the absence of IFN-α or β. Inhibition of viperin expression through siRNA knockdown led to a significant increase in HIV production, suggesting that viperin plays an important role in restricting HIV.

In this study, viperin also restricted HIV production from the HEK293T cell line in a dose-dependent manner when expressed in trans with infectious HIV. Although previous studies on viperin have focused on its induction or antiviral activity, few have addressed its mechanism of action and the domains responsible for its antiviral activity.42 Mutations in the SAM domains were able to significantly prevent viperin-mediated inhibition of HIV production and release from HEK293T cells, indicating that they are responsible for the antiviral activity of viperin. In addition, although these SAM domain mutations did not have any effect on intracellular p24 production, they increased extracellular p24 levels in the cell supernatant. This suggests that viperin prevents the assembly and/or release of de novo synthesized HIV particles rather than virus replication before these stages, probably occurring both at the cell membrane and within CD81+ invaginations of the cell membrane or “caves” as previously described for egress of HIV transfectants from these HEK293T cells43 and for MDMs.34 Surprisingly, mutation of the SAM domains also prevented colocalization of HIV and viperin, suggesting that the SAM domains may be involved in localizing viperin to the site of egress in HEK293T cells, a similar site to that observed in MDMs. How this occurs needs to be further elucidated. The significant inhibition of viperin activity with the short C terminal domain truncations (< 33 amino acids) was consistent but was not observed with the longer truncations, perhaps suggesting that short truncations may alter the tertiary structure of viperin and destabilize the molecule. For HCV, viperin was initially shown to inhibit at the level of RNA replication using the HCV subgenomic replicon system, in which the SAM domains played a role.44 However, using a more relevant infectious HCV replication model, viperin was recently shown to inhibit HCV RNA replication through interaction with the HCV NS5A protein and the proviral host factor VAP-A. The C-terminus rather than the SAM domains of viperin were essential for its antiviral effect.23,45

Viperin appears to inhibit replication of other viruses by at least 2 different mechanisms. First, in influenza virus-infected murine macrophages, viperin interacts with and inhibits FPPS, an enzyme involved in the synthesis of multiple isoprenoid-derived lipids. Inhibition of FPPS resulted in the disruption of lipid rafts and prevented viral budding from the plasma membrane. This effect was reversed with exogenous farnesol.36 Second, geranylgeraniol, but not farnesol, enhanced HCV replication through lipid droplets.38

Cholesterol is a major component of lipid raft microdomains and is important at multiple stages of the HIV life cycle. Lipid rafts are important in the entry45 and budding of HIV from the tetraspanin-rich compartments of MDMs and the plasma membrane of T cells.46 Here we showed that HIV infection of MDMs induces viperin, which disperses lipid rafts36 and subsequently inhibits budding from CD81+ caves in MDMs. In addition, we showed that viperin is exerting its inhibitory effect in MDMs via FPPS. Exogenous farnesol, which prevented lipid raft disruption and permitted viral budding, significantly enhances HIV production to a much greater extent than geranylgeraniol, suggesting that the mechanism of viperin inhibition of HIV replication in human MDMs is more similar to that of influenza than HCV. Furthermore, such infection induced a redistribution of viperin protein from the ER to CD81 compartments, with marked colocalization with p24 antigen. This distribution of viperin was quite different from that induced by IFN where viperin colocalized with the ER. The effects of viperin on cholesterol, lipid rafts, and prenylated proteins may be additive, especially as prenylation of proteins excludes them from lipid rafts.

The hierarchy of ISGs induced in infected MDMs was very different from those in infected T cells but more similar to MDDCs20 and independent of HIV inoculum size. In particular, viperin expression was much less marked in T cells and DCs compared with MDMs (Table 3). The enhanced induction of unconventional antiviral ISGs, especially viperin (but also others, such as IFIT1-3 and IFITM1) combined with conventional antiviral ISGs like ISG1547 in MDMs compared with T cells, may contribute to the lower productivity of HIV and relative resistance of MDMs to cell death, and the ability of macrophages to harbor long-term HIV despite ongoing viral replication. Although there was no change in the constitutively produced IRF3 in our study, there was a marked induction of IRF7 RNA, similar to that in DCs.20 Viral infection usually activates the IRF3/3, IRF7/7, or IRF7/IRF3 dimers, which then bind to the IFN promoter region to induce IFN. Thus, there must be a mechanism for inhibiting IRF7, similar to that for IRF3, to inhibit IFN production in MDMs. This requires future investigation.

One possible mechanism of HIV-mediated IFN-independent ISG induction could be the recognition of viral RNA via the cytoplasmic RNA sensors RIGI or MDA5,12 both of which demonstrated enhanced expression in HIV-infected MDMs. However, this proposed viperin induction pathway must differ from that previously reported by Rivieccio et al.48 AT-2–inactivated HIV had no effect on viperin induction compared with the live virus. As both AT-2–inactivated and live HIV are endocytosed by MDMs, this suggests that viperin induction occurred during HIV replication in the cytoplasm of MDMs rather than after uptake into the endosome where Toll-like receptor 3 is expressed.

IFNs and the genes they induce play a vital role in the host immune response to most viral infections. Our results emphasize marked viral and cell type-specific variation in the spectrum of ISGs induced, shown by more marked differences between HIV-infected macrophages and T cells and lesser differences between MDMs and DCs. Understanding the individual and combined effects of specific ISGs on HIV in different cell types may help to understand the biologic differences in HIV effects and could lead to new and more specific therapeutic strategies than those offered by IFNs.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Peter Cresswell (Yale University School of Medicine) for providing the monoclonal antibody to viperin; Dr Michael Gale Jr and Dr Arjun Rustagi (Departments of Global Health and Immunology, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, WA) for providing the polyclonal antibody to IRF3; Ms Ivy Shih, Ms Tina Iemma, and Dr Anupriya Aggarwal for preparing some of the MDM cultures and some of the viperin plasmids; Ms Valerie Marsden for immunolabeling of TZM-bl; and Dr Joey Lai for editing the manuscript.

This work was supported by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (project grant 632638 and program grant 358399).

Authorship

Contribution: N.N. performed the siRNA knockdown of viperin after HIV replication in macrophages, cotransfection experiments in HEK293T cells, immunolabeling, the mechanism of action of viperin in infected macrophages and HEK293T, quantitative PCR experiments, Western blot, prepared pure high titer HIV stocks, and wrote much of the manuscript; S.M. conducted all microarray experiments, some of the quantitative PCR experiments, some of the siRNA knockdown of viperin after HIV infection of macrophages, immunolabeling, and helped in writing the manuscript; S.G.T. planned the study design for transfection experiments of viperin and HIV into HEK293T cells, assisted with immunofluorescent staining of macrophages, and developed the protocols for high titer viral production used in this study; A.N.H. optimized the cDNA microarray system, performed some of the quantitative PCR analysis, and helped with manuscript preparation; N.W performed some of the cotransfection experiments, p24 ELISA, Western blot, and immunostaining; K.J.H. constructed the viperin plasmids and provided intellectual input; J.W. grew up some of the purified high titer virus stock used for the microarray experiments; C.R.B. performed microarray analysis; T.K.W. and D.R. performed the phosphoIRF3 Western blot; H.D. performed the interferon ELISAs; M.R.B. provided intellectual input and reagents in determining the mechanism of viperin action; and A.L.C. conceived and supervised the study, analyzed the results and prepared the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Anthony L. Cunningham, Westmead Millennium Institute, Darcy Road, Westmead NSW, 2145, Australia; e-mail: tony.cunningham@sydney.edu.au.

References

Author notes

N.N. and S.M. contributed equally to this study as first authors.