Key Points

Pediatric t(8;16)(p11;p13) AML is a rare entity defined by a unique gene expression signature and distinct clinical features.

Spontaneous remissions occur in a subset of neonatal t(8;16)(p11;p13) AML cases.

Abstract

In pediatric acute myeloid leukemia (AML), cytogenetic abnormalities are strong indicators of prognosis. Some recurrent cytogenetic abnormalities, such as t(8;16)(p11;p13), are so rare that collaborative studies are required to define their prognostic impact. We collected the clinical characteristics, morphology, and immunophenotypes of 62 pediatric AML patients with t(8;16)(p11;p13) from 18 countries participating in the International Berlin-Frankfurt-Münster (I-BFM) AML study group. We used the AML-BFM cohort diagnosed from 1995-2005 (n = 543) as a reference cohort. Median age of the pediatric t(8;16)(p11;p13) AML patients was significantly lower (1.2 years). The majority (97%) had M4-M5 French-American-British type, significantly different from the reference cohort. Erythrophagocytosis (70%), leukemia cutis (58%), and disseminated intravascular coagulation (39%) occurred frequently. Strikingly, spontaneous remissions occurred in 7 neonates with t(8;16)(p11;p13), of whom 3 remain in continuous remission. The 5-year overall survival of patients diagnosed after 1993 was 59%, similar to the reference cohort (P = .14). Gene expression profiles of t(8;16)(p11;p13) pediatric AML cases clustered close to, but distinct from, MLL-rearranged AML. Highly expressed genes included HOXA11, HOXA10, RET, PERP, and GGA2. In conclusion, pediatric t(8;16)(p11;p13) AML is a rare entity defined by a unique gene expression signature and distinct clinical features in whom spontaneous remissions occur in a subset of neonatal cases.

Introduction

In pediatric acute myeloid leukemia (AML), cytogenetic classification is important for risk-group stratification for treatment. Because the incidence of some molecular or cytogenetic aberrations is very low, international collaboration is necessary to provide insight into their clinical and biological characteristics and associated outcome.1,2 Pediatric AML with t(8;16)(p11;p13) is an example of such a rare subgroup. A recent study among adult AML patients by Haferlach et al also defined t(8;16)(p11;p13) as a rare (n = 13/6124; 0.2%), distinct subgroup with a poor outcome (median overall survival [OS] of 4.7 months) and unique immunophenotype.3 They showed that these adult t(8;16)(p11;p13) patients shared clinical and biological characteristics with MLL-rearranged AML cases, such as a high frequency of French-American-British (FAB) M4/5 subtypes, a higher frequency in therapy-related AML, and similarities in their gene expression profiles, such as HOXA overexpression.3 In addition to HOXA, also RET oncogene overexpression was reported by Camós et al to be specific for t(8;16)(p11;p13).4

The translocation, t(8;16)(p11;p13), results in fusion of MYST3 (also known as MOZ or KAT6A, located to chromosome 8p11), and CREB-binding protein (CREBBP) (located to chromosome 16p13). Both proteins have histone acetyltransferase activity, and in addition they are involved in transcriptional regulation and cell cycle control.4,5 Several different fusion transcripts have been described to fuse exon 15 or 16 of MYST3 to exon 3-8 of CREBBP.

So far, only isolated case reports and small patient series have been described for pediatric AML cases with t(8;16)(p11;p13). Some case reports suggested that spontaneous remissions occur, whereas others showed that outcome was poor.5-28 To verify these observations, we performed a large international retrospective study, which was conducted within the framework of the International Berlin-Frankfurt-Münster (I-BFM) AML study group, to examine the clinical characteristics and outcome of pediatric AML cases characterized by t(8;16)(p11;p13). We further aimed to identify biological and molecular characteristics using morphology, immunophenotyping, and gene expression profiling (GEP).

Patients and methods

Patients

To describe the largest possible cohort, detailed data on 39 patients with pediatric t(8;16)(p11;p13) AML, aged 0-18 years, were collected from collaborators in 18 countries participating in the I-BFM AML Study Group (Table 1). Three of these cases were previously published.17,18,27 The series was supplemented with cases previously reported in the literature.5-19,21-23,25-28 Where possible, we contacted the authors to provide missing data and material. Archive cases from the literature were only included when a well-documented cytogenetic report and clinical data were available. The combined series of pediatric t(8;16)(p11;p13) patients thereby consisted of 62 unique cases (Table 1).

All newly reported patients were identified by the respective study groups after reviewing their karyotypic records for t(8;16)(p11;p13) pediatric AML cases, as determined by G-, Q-, or R-banded karyotyping, FISH and/or reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction18,29 (RT-PCR). A predefined set of data were collected for each case and checked for consistency, including gender, age, WBC, hemoglobin, platelet count, extramedullary involvement (central nervous system [CNS] involvement, cutaneous leukemia, other extramedullary involvement), FAB morphology, presence of erythrophagocytosis, and immunophenotype. Survival analysis was performed on patients diagnosed after January 1, 1993, who were treated with chemotherapy at initial diagnosis. Data were collected on therapy regimens, including hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), and events (including nonresponse, relapse, occurrence of second malignancy, or death). Exclusion criteria included secondary AML after congenital bone marrow failure disorders, aplastic anemia, and previous myelodysplastic syndrome. Patients were treated on national/international AML protocols, approved according to local law and regulations, by the Institutional Review Boards of each participating center with informed consent obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Cytogenetic review

All karyotypes from new patients were centrally reviewed by two independent expert cytogeneticists (O.A.H., C.J.H.), following the International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature (ISCN 2005). Patients with inconclusive karyotypes were screened by RT-PCR, using primers and PCR conditions as previously described.18,29 From the literature reports only well-documented cytogenetic data as presented in the original manuscript were included.

Morphology review

Bone marrow smears were centrally reviewed, performed (V.d.H.) according to FAB morphology classification. Erythrophagocytosis was scored as “present” or “absent.”

Complete remission was defined by less than 5% blasts in a bone marrow with regeneration of trilineage hematopoiesis.

Immunophenotype

Immunophenotypic data, including expression of CD4, CD11b, CD13, CD14, CD15, CD33, CD34, CD133, CD56, CD64, CD65, CD117, MPO, and HLA-DR, were collected from the national or local registries. Collaborators were asked to score each antibody as “positive,” “dim,” or “negative.” If percentages of cells scoring positive were provided, the values were centrally reviewed (V.H.J.v.d.V.) and subsequently coded as positive (≥20%) or negative (<20%) expression.

GEP

Viably frozen cells were available on 15 pediatric t(8;16)(p11;p13) AML cases. Leukemic cells were isolated and enriched as previously described.32 All samples included for GEP (n = 8) contained 80% or more leukemic cells, as determined morphologically by May-Grünwald-Giemsa (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany)–stained cytospins. A minimum of 5 × 106 leukemic cells were lysed in Trizol reagent (Gibco BRL/Life Technologies, Breda, The Netherlands) and stored at −80°C. Isolation of total cellular RNA was performed as described earlier.32

GEP for an additional 289 pediatric AML patients samples had been previously performed.33,34 Original data are available in the Gene Expression Omnibus repository (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo; accession GSE17855).

Quantitative real-time PCR (RT-qPCR)

For validation of differentially expressed genes, quantitative real-time PCR (RT-qPCR) was performed on cDNA of 30 pediatric AML patient samples, of which 14 had t(8;16)(p11;p13), and on cDNA of 13 cell lines. Primers used are described in supplemental Table 1. SYBRgreen was used for expression analysis of target genes. The expression of the genes was compared with GAPDH, using primers and probe as previously described (sequences are shown in supplemental Table 1).35 Detection methods and analysis were described previously.35

Targeted shRNA knockdown of identified genes

To validate the function of selected differentially expressed genes, we performed lentiviral shRNA mediated knockdown for each gene in 2 of 3 AML cell lines with high expression of these genes (THP1 [t(9;11)], OCI-AML3 [NPM1 mutated, miscellaneous cytogenetics], and NOMO1 [t(9;11)]) as previously described using shRNA constructs, as listed in supplemental Table 1.36 Cell counts, annexin/PI apoptosis assay, and drug cytotoxicity assay, using 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide as a cell viability read-out, were performed as previously described and according to the manufacturer’s guidelines.36

Statistical analyses

Statistical analysis of GEP was performed using the statistical data analysis environment R, version 2.14. An empirical Bayes linear regression model was used to compare the signatures of the t(8;16)(p11;p13) cases with the other AML cases.37 Unsupervised clustering was performed as previously described.38

For comparison of gene expression in different groups, the Mann-Whitney test and Kruskal-Wallis test were used. The Spearman’s Correlation coefficient was used to correlate the results from GEP and RT-qPCR. As SYBRgreen was used in the RT-qPCR reaction, only Ct values <32 were used for calculating correlation coefficients with GEP. For comparison of clinical variables between groups, the χ-square test and Fisher’s exact test were used. Probabilities of OS and event-free survival were estimated by the method of Kaplan and Meier and compared by the Log-rank Test. The Gray’s test for competing risks was used for analysis of cumulative incidence of relapse. Event definitions were as previously described.2 All analyses were performed with SPSS Statistics version 17.0 (SPSS Inc. Chicago, IL). All tests were two-tailed, and a P value of less than .05 was considered significant.

Results

Clinical features

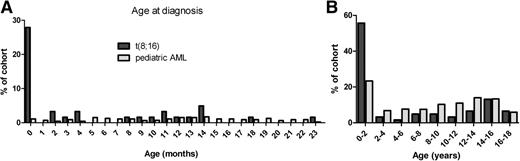

A total of 62 patients with t(8;16)(p11;p13) were identified, and the clinical characteristics were compared with the BFM-AML reference cohort (Table 1). Median age at diagnosis was 1.2 years (range 0.0-17), and, apart from the high frequency shortly after birth (17 cases of t(8;16)(p11;p13) were diagnosed within the first month of life), occurrence was stable throughout childhood. Compared to the pediatric AML reference cohort, the frequency of congenital cases was significantly higher (Figure 1, P ≤ .01). Two cases with treatment-related AML (one after dysgerminoma and one after acute lymphocytic leukemia) were included.5,18

Age at diagnosis of pediatric cases with t(8;16)(p11;p13) as compared with a pediatric AML reference cohort. Shown are two histograms depicting the age at diagnosis for two cohorts: t(8;16)(p11;p13) in dark gray, and a reference cohort of unselected pediatric AML patients treated by AML-BFM study group between 1995-2005 in light gray. (A) Age at diagnosis is shown in categories of months for the first 2 years after birth. (B) Age at diagnosis is shown in categories of 2 years until the age of 18. In t(8;16)(p11;p13) AML, after an initial peak in the occurrence shortly after birth, occurrence is stable through childhood. In the reference cohort, the frequency of congenital cases is significantly lower.

Age at diagnosis of pediatric cases with t(8;16)(p11;p13) as compared with a pediatric AML reference cohort. Shown are two histograms depicting the age at diagnosis for two cohorts: t(8;16)(p11;p13) in dark gray, and a reference cohort of unselected pediatric AML patients treated by AML-BFM study group between 1995-2005 in light gray. (A) Age at diagnosis is shown in categories of months for the first 2 years after birth. (B) Age at diagnosis is shown in categories of 2 years until the age of 18. In t(8;16)(p11;p13) AML, after an initial peak in the occurrence shortly after birth, occurrence is stable through childhood. In the reference cohort, the frequency of congenital cases is significantly lower.

Extramedullary disease (CNS involvement or leukemia cutis or other extramedullary disease, such as granulocytic sarcoma involving the bone) was present in 25/38 patients (66%) with sufficient data available compared with 122/543 (22%) in the reference cohort (P < .01). CNS involvement was reported in 6/40 patients (15%) compared with 61/511 (12%) in the reference cohort (P = .61). Leukemia cutis was clinically identified in 21/36 patients (58%) and was reported significantly more frequently in patients under 1 year old (18/22 patients, 82%) than in patients more than 1 year (3/14 patients, 21%) (P ≤ .01). The reference cohort reported leukemia cutis in 8% of cases (P < .01). DIC was reported in 15/38 patients (39%) at diagnosis (Table 1) with none recorded in the reference cohort.

Morphology

Almost all (97%) of the patients presented with a myelomonocytic (M4) or monocytic (M5) FAB type of AML (Table 1), compared with 41% in the reference cohort (P < .01). Erythrophagocytosis was present in 23/33 (70%) patients for whom sufficient morphology data were available (Table 1). Data on erythrophagocytosis were not available in the reference cohort.

Immunophenotype

The most relevant immunophenotypic markers are summarized in Table 1. Almost all t(8;16)(p11;p13) cases were positive for the myeloid markers MPO (n = 24/27), CD13 (n = 20/31), and/or CD33 (n = 29/31) (Table 1). The stem cell markers CD117 and CD34 were positive in 2/14 and 4/24 cases with available data, respectively (Table 1). Virtually all patients were positive for CD15 (n = 23/23) and HLA-DR (n = 21/22), and 21/33 patients displayed expression of the monocytic antigen CD14, indicative of monocytic differentiation (Table 1).

Cytogenetics

Karyotypes are provided in Table 2. At initial diagnosis, 35 of 57 (61%) cases with complete karyotypes showed t(8;16)(p11;p13) as the sole aberration (Table 2). One infant had a normal karyotype at initial diagnosis but developed t(8;16)(p11;p13) at relapse, following spontaneous complete remission. In total, 22/57 patients exhibited additional cytogenetic aberrations, but none were recurrent (Table 2). All patients from whom a karyotype was available at initial diagnosis, as well as at relapse, showed signs of clonal evolution at the relapse time point (Table 2).

Treatment and outcome

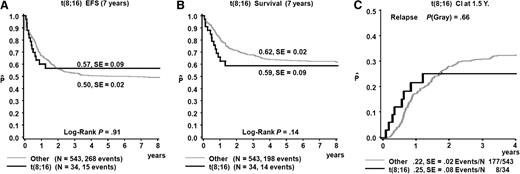

Treatment with curative intent was administered to 49/57 (86%) patients (median age 1.6 years, range 0.0-17.0 years). Survival was analyzed only for the 34 patients diagnosed after January 1, 1993, to whom intensive chemotherapy at initial diagnosis was administered with curative intent (median age 5.0 years, range 0.0-17.0 years). A total of 6 patients received allogeneic HSCT in first complete remission, and in 3 patients treatment included autologous HSCT. OS estimate of the cohort was 59% (±9%) at 5 years, event-free survival 57% (±9%), and cumulative incidence of relapse 28% (±8%), showing no difference from the reference cohort (Figure 2). Most events occurred soon after diagnosis, with 7/8 relapses occurring within the first year after diagnosis.

Survival t(8;16)(p11;p13) patients as compared with a pediatric AML reference cohort. Survival curves of t(8;16)(p11;p13) patients diagnosed after January 1, 1993, and treated up front with chemotherapy compared with 543 unselected pediatric AML patients treated by the AML-BFM study group between 1995 and 2005.

Survival t(8;16)(p11;p13) patients as compared with a pediatric AML reference cohort. Survival curves of t(8;16)(p11;p13) patients diagnosed after January 1, 1993, and treated up front with chemotherapy compared with 543 unselected pediatric AML patients treated by the AML-BFM study group between 1995 and 2005.

The 8 patients who were not treated included 7 very young infants (case Nos. 28, 34, 35, 37, 40-41, 62) who were closely monitored without administering therapy. All 8 patients achieved spontaneous complete remission. The clinical courses of the 7 congenital cases (diagnosed within the first month of life) are summarized in Table 3. Three remain in complete continuous remission, whereas 4 patients suffered disease recurrence (median time to recurrence 17 months, range 8-48 months), for which treatment was successful in 2 patients (Table 3). For case 35, the second AML was proven to be unrelated, and this patient was suspected to carry a condition predisposing her for the development of AML (personal communication with Kiminori Terui). In one 2-year-old patient (case No. 39), AML was suggested to have been induced by valproic acid.22 This child remained in remission at follow-up after discontinuation of valproic acid for a period of 1 year (Table 1).

GEP

Unsupervised clustering of 297 pediatric AML patient samples showed tight clustering of t(8;16)(p11;p13) cases (n = 8) (Figure 3). Moreover, t(8;16)(p11;p13) cases clustered strongly together with, but separate from, MLL-rearranged AML in the unsupervised analysis (Figure 3). Overexpression of HOXA genes was found, and together with MLL-rearranged patients, the t(8;16)(p11;p13) patients represented the only other group of pediatric AML patients that selectively activate HOXA genes without HOXB gene activation. In fact, t(8;16)(p11;p13) samples could not be distinguished from MLL-rearranged cases based on clustering on HOXA and HOXB probes only, as described by Hollink et al34 (supplemental Figure 1).

Unsupervised clustering of the gene expression profiles of 297 pediatric AML patients. Pairwise correlations between 297 samples of pediatric patients with acute myeloid leukemia. The cells in the visualization are colored by Pearson's correlation coefficient values with deeper colors indicating higher positive (red) or negative (blue) correlations. Cytogenetic data are depicted in the columns along the original diagonal of the heatmap. Cytogenetic group classification is depicted in the first column (MLL-rearranged-green, inv(16)-red, t(8;21)-yellow, t(15;17)-purple, t(7;12)-brown, cytogenetically normal-blue, other-orange, unknown-aqua). Presence of t(8;16)(p11;p13) is depicted in the second column (t(8;16)-blue, no t(8;16)-yellow).

Unsupervised clustering of the gene expression profiles of 297 pediatric AML patients. Pairwise correlations between 297 samples of pediatric patients with acute myeloid leukemia. The cells in the visualization are colored by Pearson's correlation coefficient values with deeper colors indicating higher positive (red) or negative (blue) correlations. Cytogenetic data are depicted in the columns along the original diagonal of the heatmap. Cytogenetic group classification is depicted in the first column (MLL-rearranged-green, inv(16)-red, t(8;21)-yellow, t(15;17)-purple, t(7;12)-brown, cytogenetically normal-blue, other-orange, unknown-aqua). Presence of t(8;16)(p11;p13) is depicted in the second column (t(8;16)-blue, no t(8;16)-yellow).

The t(8;16)(p11;p13) patients were compared with other AML patients in a supervised fashion, using an empirical Bayes linear regression model. This comparison resulted in a strong signature containing 5594 probes with an FDR adjusted P value <.05, among which 2984 had a P value <.01 and 1615 had a P value <.001. The top 50 most differentially expressed probe sets are shown in supplemental Table 2.

Subsequently, we compared this gene list with FDR adjusted P value <.001 (n = 1615), to the discriminative probe sets reported by Haferlach et al3 (n = 55), and found a concordance of 48/55 probes.

From the top-list (supplemental Table 2), we selected 2 genes for validation with RT-qPCR based on P value, fold-change and the identification by more than 1 probe-set in the top-list; GGA2 (golgi-associated, γ adaptin ear containing, ARF binding protein 2)(represented by 5 probe-sets in the top-50) and PERP (TP53 apoptosis effector Related to PMP22) (represented by 2 probe-sets in the top-50) (Figure 4). The median relative expression of GGA2 by RT-qPCR in patients with t(8;16)(p11;p13) was 10.7-fold higher than other pediatric AML patients (84% vs 7.9%, P < .001), which correlated with mRNA expression as determined by GEP (208913_at, Spearman R = .88 [P < .001]) (Figure 4). The median relative expression of PERP by RT-qPCR in patients with t(8;16)(p11;p13) was 70.7-fold higher than other pediatric AML patients (1.4% vs .02%, P < .001; Figure 4) and correlated with mRNA expression as determined by GEP (217744_s_at, Spearman R = .79 [P < .001]) (Figure 4).

GGA2 and PERP mRNA expression. RET indicates relative expression measured by RT-qPCR. Shown is GGA2 and PERP mRNA expression levels of pediatric AML patient samples and AML cell lines. (A,B) Levels from GEP for GGA2 and PERP, respectively. (C,D) Levels as determined by RT-qPCR. (E,F) show the correlation between both RT-qPCR and GEP.

GGA2 and PERP mRNA expression. RET indicates relative expression measured by RT-qPCR. Shown is GGA2 and PERP mRNA expression levels of pediatric AML patient samples and AML cell lines. (A,B) Levels from GEP for GGA2 and PERP, respectively. (C,D) Levels as determined by RT-qPCR. (E,F) show the correlation between both RT-qPCR and GEP.

shRNA mediated knockdown

shRNA mediated knockdown of PERP was effective in the AML cell lines THP1 and OCI-AML3 with 80% to 95% mRNA knockdown for 9 to 14 days (supplemental Figure 2). Cell counts, annexin/PI apoptosis, and drug cytotoxicity assays were performed, but no significant changes were detected in proliferation, apoptosis, and drug sensitivity with PERP-knockdown compared with nonsilencing control shRNA (supplemental Figure 2). For GGA2, knockdown percentages of only 40% to 60% were achieved (data not shown). With this level of knockdown, no significant changes in cell proliferation or apoptosis were observed (data not shown).

Discussion

In this international collaboration involving study groups from 18 different countries, we studied the clinical and biological features of childhood AML with the rare translocation t(8;16)(p11;p13). We showed that almost half of the cases were younger than 2 years at diagnosis, and in 28% the leukemia was diagnosed within the first month of life. Pediatric t(8;16)(p11;p13) AML was characterized by a considerable frequency of leukemia cutis and erythrophagocytosis.39 The association between t(8;16)(p11;p13) AML and erythrophagocytosis has been reported in adults.3 Interestingly, CD56 expression has been associated with both hemophagocytosis rate and leukemia cutis.40-42 This cell surface marker was present in 71% of adult AML patients with t(8;16)(p11;p13).3 Because of the small number of pediatric cases with data on CD56 expression, we were unable to associate CD56 expression with leukemia cutis or erythrophagocytosis.

In this study, pediatric t(8;16)(p11;p13) AML had an outcome comparable to other pediatric AML cases, in contrast to the previous report in adults, where t(8;16)(p11;p13) AML had a dismal outcome.3 This difference might be a result of the rather large proportion of therapy-related secondary AML cases in the adult cohort, whereas only 2 patients were included in our cohort.3

All 7 cases with congenital t(8;16)(p11;p13) AML, in whom a “watch-and-wait” policy was applied, showed spontaneous remission. In addition, a very recent publication also reported a 2-month-old patient with t(8;16)(p11;p13) positive myeloid sarcoma that regressed spontaneously.43 However, four patients from our cohort suffered from disease recurrence. This suggests that a “watch-and-wait” policy could be considered in congenital t(8;16)(p11;p13) patients with mild clinical symptoms, provided that close long-term monitoring is applied. Besides transient myeloproliferative disorder (TMD) of Down syndrome, t(8;16)(p11;p13) is the only other known acute leukemia in neonates that shows recurrent self-limiting cases. In general, they have higher bone marrow blast counts (median blast percentage of 57%) than TMD patients, but share the increased risk of AML recurrence. In comparison, in the reference cohort of pediatric AML, 10 patients under the age of 2 months were included, none of whom showed spontaneous remission.

We showed that the gene expression profile of pediatric t(8;16)(p11;p13) AML is highly distinct from other pediatric AML patients. In one outlier that was found by unsupervised clustering, we could not yet detect involvement of MYST3 and CREBBP by RT-PCR. This cytogenetically normal AML patient, however, has a highly similar gene expression profile (Figures 3 and 4). Two samples from infants (aged 1 and 3 months) were included in the GEP cohort, and 3 others in the validation cohort. Interestingly, the GEP signature of infants was similar to the signature of older patients with t(8;16)(p11;p13) AML. Clustering showed differences but also similarities to MLL-rearranged AML, underscoring the unique biological nature of the disease. Overexpression of HOXA genes was found, which is consistent with the data reported in adult AML with t(8;16)(p11;p13).3,4,44 MLL-rearranged and t(8;16)(p11;p13) AML patients represent the only groups of pediatric AML patients who selectively activate HOXA genes without HOXB gene activation.34 This suggests that for these leukemia types, HOXA upregulation is the common pathway to leukemogenesis, as specific HOXA overexpression in hematopoietic stem cells increases the numbers of hematopoietic stem cells.45 The similarity may be caused by the fact that MYST3-CREBBP- and MLL-translocations are characterized by fusion genes that have important roles in histone modification. The mechanism of HOXA gene upregulation remains unexplained for the t(8;16)(p11;p13) AML cases however, as HOXA genes are not described as direct targets of MYST3. Both MYST3 and CREBBP are also involved in other rare translocations in AML, such as t(10;16)(q22;p13) (MYST4-CREBBP), t(8;22)(p11;q13) (MYST3-EP300), and t(11;16)(q23;p13.3) (MLL-CREBBP). Expression of both MYST3 and CREBBP, however, is not specific to t(8;16)(p11;p13) cases compared with other AML subtypes (data not shown).

The frequent occurrence of congenital and infant t(8;16)(p11;p13) cases in this cohort, and the fact that in adults t(8;16)(p11;p13) is associated with treatment related AML,3,5,29 could point to sensitivity of the genome (especially at the loci of MYST3 and CREBBP) in utero or during genotoxic stress. These findings resemble MLL-rearranged AML, where topoisomerase II inhibitors are considered to be a trigger. Firm biological data in t(8;16)(p11;p13) AML, however, are unfortunately lacking because of the rarity of the disease.

Camós et al previously highlighted RET proto-oncogene overexpression in adult t(8;16)(p11;p13) AML and postulated that differential expression of miRNA miR-15b, −195, and −218 might influence the expression of RET.4,46 In our pediatric t(8;16)(p11;p13) AML series, RET proto-oncogene was also overexpressed (supplemental Table 2). This observation illustrates that both adult and pediatric t(8;16)(p11;p13) patients have similarities in their profiles, underscored by the concordance of 87% of our highly significant probe sets with the discriminative probe sets as published by Haferlach et al.3

From the differentially expressed genes in pediatric t(8;16)(p11;p13), we confirmed specific overexpression of PERP and GGA2. PERP is a direct target gene of p53 that acts as an effector of p53, and high expression induces caspase dependent apoptosis.47,48 In zebrafish, however, perp expression seems to play an antiapoptotic role in skin and notochord cells by regulating survival.49 Because of the unknown function of PERP in leukemic cells, we performed shRNA mediated PERP knockdown in AML cells, but no effects on cell proliferation, apoptosis, and drug sensitivity were found.

GGA2 regulates the trafficking of proteins between the trans-Golgi network and the lysosome.50,51 It cooperates with mannose 6-phosphate receptors and the adaptor protein AP-1 to regulate protein sorting.50,51 GGA2 overexpression was found in this study and also in adults with t(8;16)(p11;p13) AML. With shRNA, we achieved knockdown percentages of GGA2 of only 40% to 60% with no significant changes in cell proliferation or apoptosis. Thus we were unable to postulate a leukemogenic function. Therefore, although PERP and GGA2 are highly specifically overexpressed in t(8;16)(p11;p13) AML, we conclude based on our experiments that there are currently no data to support a driving role for PERP and GGA2 in leukemogenesis.

A limitation of our strategy to include retrospectively both historical reports and cases from large registries is that datasets may be incomplete and reviews of data were sometimes limited. Furthermore, from historical reports, there was a higher frequency of infant and congenital cases than reported by the study group registries. This could result in an underestimation of the average age of t(8;16)(p11;p13) patients.

In conclusion, this international collaborative study describes the rare entity of pediatric t(8;16)(p11;p13) AML, indicating intermediate survival of this very distinct subgroup. Pediatric t(8;16)(p11;p13) AML is characterized by M4/M5 morphology, a high frequency of leukemia cutis, erythrophagocytosis, and DIC. The gene expression signature of t(8;16)(p11;p13) is unique, although resembling the signature of MLL-rearranged AML. Most striking is the fact that spontaneous remissions often occur in neonates with t(8;16)(p11;p13), of which almost half of the cases remain in continuous remission without recurrence of disease. The risk of recurrence, however, warrants close follow-up.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is an Inside Blood commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The work of E.A.C. was supported by the Pediatric Oncology Foundation Rotterdam (KOCR) and by the Children Cancer Free Foundation (KiKa), Amstelveen, The Netherlands. The work of D.T. and K.T was supported in part by a grant-in-aid for Cancer Research from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan.

Authorship

Contribution: E.A.C., M.M.v.d.H.-E., C.M.Z., and R.P. designed the study; C.J.H., V.d.H., V.M., B.D.M., M.J., J.E.R., D.T., D.J., T.A.A., H.H., D.R., A.A., M.D., A.P., J.S., K.-f.W., K.T., S.S., M.W., and G.V. contributed materials and clinical data; E.A.C., C.J.H., O.A.H., V.d.H., V.H.J.v.d.V., C.M.Z., R.P., and M.M.v.d.H.-E. analyzed data; E.A.C. and M.Z. performed statistical analysis; E.A.C., C.M.Z., R.P., and M.M.v.d.H.-E. wrote the paper; R.P., C.M.Z., and M.M.v.d.H.-E. supervised the study; and all coauthors performed critical review of the manuscript and gave their final approval.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Marry M. van den Heuvel-Eibrink, Associate Professor in Pediatric Oncology/Hematology, Erasmus MC/Sophia Children’s Hospital, Department of Pediatric Oncology/Hematology, Room Sp2568, Dr Molewaterplein 60, Post Office Box 2060, 3000 CB Rotterdam, The Netherlands; e-mail: m.vandenheuvel@erasmusmc.nl.