Key Points

A functional demonstration of the oncogenic role of mutated EZH2 in a mouse model is presented.

The global effects of mutated EZH2 on expression and epigenome have been characterized.

Abstract

The histone methyltransferase EZH2 is frequently mutated in germinal center–derived diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and follicular lymphoma. To further characterize these EZH2 mutations in lymphomagenesis, we generated a mouse line where EZH2Y641F is expressed from a lymphocyte-specific promoter. Spleen cells isolated from the transgenic mice displayed a global increase in trimethylated H3K27, but the mice did not show an increased tendency to develop lymphoma. As EZH2 mutations often coincide with other mutations in lymphoma, we combined the expression of EZH2Y641F by crossing these transgenic mice with Eµ-Myc transgenic mice. We observed a dramatic acceleration of lymphoma development in this combination model of Myc and EZH2Y641F. The lymphomas show histologic features of high-grade disease with a shift toward a more mature B-cell phenotype, increased cycling and gene expression, and epigenetic changes involving important pathways in B-cell regulation and function. Furthermore, they initiate disease in secondary recipients. In summary, EZH2Y641F can collaborate with Myc to accelerate lymphomagenesis demonstrating a cooperative role of EZH2 mutations in oncogenesis. This murine lymphoma model provides a new tool to study global changes in the epigenome caused by this frequent mutation and a promising model system for testing novel treatments.

Introduction

EZH2 is a histone methyltransferase1 and part of the polycomb repressive complex 2, which is known to regulate the trimethylation of histone H3K27, a gene silencing mark (reviewed in Sauvageau and Sauvageau2 ). In mice, Ezh2 has been shown to be critical in multiple developmental processes. A knockout of Ezh2 is lethal at the early postimplantation stage,3 whereas Ezh2 expression was found to be associated with proliferation in different tissues in normal development.4 In addition, a conditional knockout showed that Ezh2 was necessary for proper B-cell development.5 EZH2 expression is also prominent in the germinal center (GC).6,7

EZH2 has become increasingly recognized in different types of cancers. Increased abundance of EZH2 messenger RNA correlates with cancer progression in tissues where EZH2 expression is normally low or undetectable, such as in the prostate.8 Moreover, Ezh2 appears to be an important regulator in hematopoietic stem cells.9,10 This role of EZH2 seems to extend to malignant stem cells.11 Alterations in EZH2 expression were also implicated in the development of different types of B-cell lymphomas.12-14

Using massively parallel sequencing approaches, our center has identified somatic mutations of EZH2Y641 in 22% of GC-derived diffuse large B-cell lymphomas (DLBCLs) as well as 7% of follicular lymphomas.15 The more recently characterized EZH2A677G mutations are estimated to occur at a frequency of 2% to 3%.16 These data indicate that EZH2 mutations are among the most frequent genetic events observed in GC-derived malignancies and, together with mutations identified in other histone-modifying enzymes (such as CREBBP/EP30017 and MLL218 ), point toward an important role of epigenetic deregulation in the pathogenesis of lymphoma.

Strikingly, the recurrent mutations of EZH2 in lymphomas are all located in the evolutionary conserved SET domain. The most common mutations change the Y641 codon to a restricted set of amino acids, mostly phenylalanine (F) (49% of all cases), but also serine (S) (21%), asparagine (N) (15%), histidine (H) (13%), and cysteine (C) (2%). In all the cases analyzed, only 1 allele was found mutated, suggesting that endogenous EZH2 plays an essential role. We and others have demonstrated that these EZH2Y641 mutations cause a gain of function of EZH2 by altering its substrate specificity. Although the mutations lead to a decrease in the activity of EZH2 toward unmethylated or monomethylated H3K27, they increase its activity toward the dimethylated substrate. In concert with an intact wild-type (WT) allele, this causes an increase in the formation of trimethylated H3K27 as observed both in cell lines and patient samples harboring the mutation.19,20 Recently, several small molecule inhibitors of EZH2 have been described. These also target mutated EZH2 making it an attractive drug target.21-24

To directly test the possible role of EZH2 mutations as driver mutations in lymphomagenesis, we have generated and characterized a transgenic mouse model where EZH2Y641F (the most commonly observed mutant form) is expressed from a lymphoid-specific promoter. Although not sufficient on its own to cause lymphoma, this transgene dramatically accelerated the development of lymphoma in combination with Eµ-Myc and also had an impact on B-cell development and lymphoma phenotype in these mice.

Materials and methods

Generation and workup of EZH2Y641F transgenic mice

EZH2Y641F transgenic mice were generated in the disease modeling core of the British Columbia Cancer Agency Research Centre using standard methods. EZH2Y641F transgenic mice were bred with C57BL/6 mice. Eµ-Myc mice (B6.Cg-Tg[IghMyc]22Bri/J) were obtained from Jackson Laboratories and were bred by crossing female mice transgenic for EZH2Y641F with male Eµ-Myc mice. All breeding, maintenance of mice, and experiments involving mice were performed in the Animal Resource Centre of the British Columbia Cancer Agency as approved by the University of British Columbia Animal Care Committee and at the Zentrale Forschungseinrichtung of the Goethe University Frankfurt as approved by the Regierungspräsidium Darmstadt. Details on the generation of the transgenic mice can be found in the supplemental Methods (see the Blood Web site).

Flow cytometry and sorting

Lineage distribution in cells from spleen, bone marrow, and lymph nodes was determined by fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis using a FACSCalibur or a FACSCanto instrument (Becton Dickinson [BD], Mississauga, ON, Canada). Staining was performed in phosphate-buffered saline with 2% fetal bovine serum. After 1 washing step, cells were resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline supplemented with 2% fetal bovine serum and 0.4 µg/mL propidium iodide or 7-aminoactinomycin D (BD). Analysis was performed using FlowJo analysis software. Sorting of B-cell populations was performed using an Influx II or FACSAria III cell sorter.

Western blot

Western blotting for histone modifications was done as previously described.20 Details can be found in the supplemental Methods.

Southern blot

Genomic DNA was extracted from cut mouse tail tips by proteinase K digestion followed by a phenol-chloroform extraction from isolated bone marrow, spleen, or lymph node cells using DNAzol reagent as recommended by the manufacturer (Invitrogen). Southern blot analyses were performed as previously described.25 For analysis of the integration of the transgenic construct, DNA was digested with BamHI (Invitrogen) and probed with the human growth hormone part of the transgenic construct. Southern blots for determination of clonality of the V(D)J rearrangement were performed by digesting the DNA with EcoRI (Invitrogen) and detected with a probe against the JH4 region of the IgH locus that was generated by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification from genomic DNA as described.26

Quantitative real-time reverse transcriptase PCR

RNA was extracted from sorted B-cell populations, and cDNA was synthesized using SuperScript VILO cDNA Synthesis Kit (Invitrogen). Quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR was performed as described in the supplemental Methods.

Global gene expression and histone methylation analysis

Spleen cells were isolated from 1 Eµ-Myc mouse and 1 Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F mouse before the onset of disease symptoms. The extracted spleen cells were stained for B220 and sorted using a BD Influx 2 cell sorter; 1 × 107 sorted cells were snap-frozen for chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP), and 1 × 107 sorted cells used for RNA extraction using the Trizol protocol. Processing for RNA sequencing and ChIP sequencing was performed using quality-controlled protocols at the Michael Smith Genome Sciences Centre.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism. Experimental details can be found in the supplemental Methods.

Results

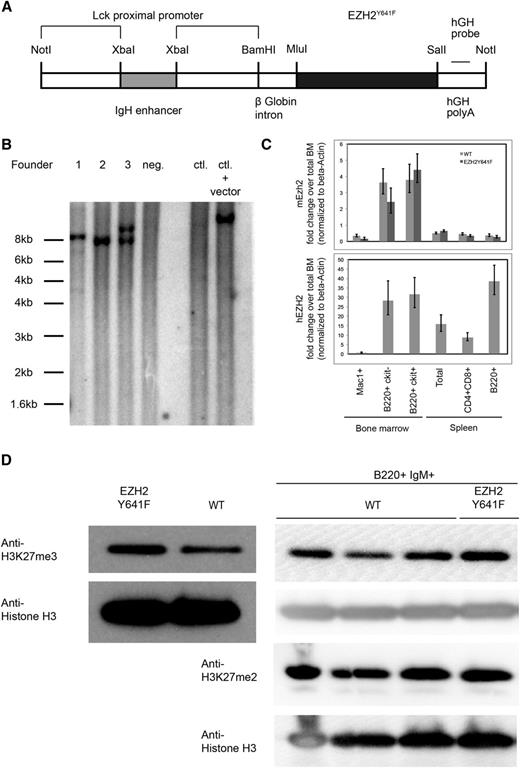

Generation of EZH2Y641F transgenic mice

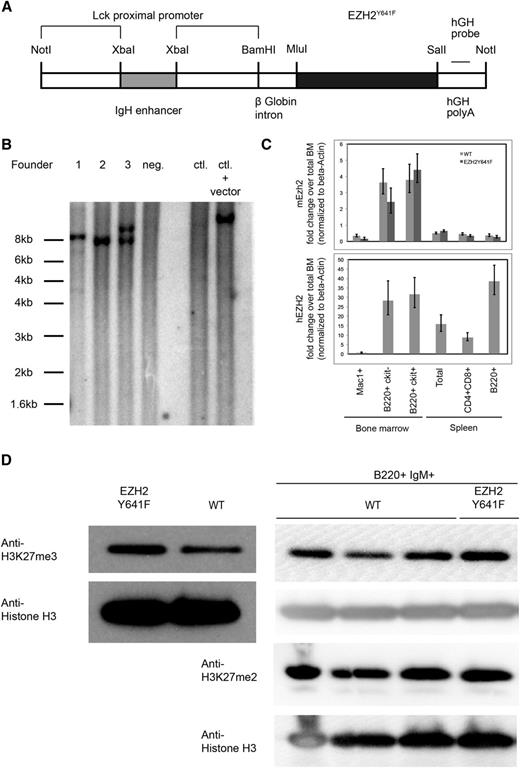

To examine how EZH2Y641 mutations might contribute to the development of GC-derived lymphoma and to determine if they have an oncogenic role, we generated mice transgenic for EZH2Y641F. In order to achieve expression of the transgene in the B-cell lineage while limiting expression outside the lymphoid system, we used a transgenic vector containing an XbaI fragment of an IgH enhancer upstream of an Lck promoter, which has been shown to allow pan-lymphocyte transgene expression27 (Figure 1A). One of the 3 identified founders passed the transgene to the next generation (founder 3) and was bred to establish a transgenic line (Figure 1B). Mice transgenic for EZH2Y641F were viable, fertile, and born at a normal Mendelian ratio. One other founder was lost early without signs of disease; 1 female founder did not give rise to viable offspring but was monitored for disease development.

Generation of EZH2Y641F transgenic mice. (A) Schematic representation of the construct used to generate the mice. (B) Southern blot using a probe specific for the human growth hormone (hGH) sequence in the transgene performed on 3 transgenic founder mice (1-3), 1 nontransgenic littermate (4), C57Bl6 control (WT) DNA, and C57Bl6 control DNA spiked with 10 pg of plasmid DNA containing the transgenic construct. Genomic DNA was digested using BamHI. Founder 1 carries multiple integrations of the transgenic construct at 2 integration sites; founder 2 contains 1 copy of the transgenic construct in 1 integration site; and founder 3 has 2 copies of the transgenic construct at 1 integration site. (C) Detection of expression of the transgenic construct by quantitative PCR. The lower panel shows a PCR specific for the transgenic construct, and the upper panel a PCR that detects endogenous Ezh2. (D) Steady-state H3K27me3 and H3K27me2 levels in splenic B cells and sorted B220+IgM+ cells. Nuclear lysates from spleen cells of a mouse transgenic for EZH2Y641F or a WT mouse were probed with an antibody against H3K27me3. Levels of H3 were used as a loading control for histones.

Generation of EZH2Y641F transgenic mice. (A) Schematic representation of the construct used to generate the mice. (B) Southern blot using a probe specific for the human growth hormone (hGH) sequence in the transgene performed on 3 transgenic founder mice (1-3), 1 nontransgenic littermate (4), C57Bl6 control (WT) DNA, and C57Bl6 control DNA spiked with 10 pg of plasmid DNA containing the transgenic construct. Genomic DNA was digested using BamHI. Founder 1 carries multiple integrations of the transgenic construct at 2 integration sites; founder 2 contains 1 copy of the transgenic construct in 1 integration site; and founder 3 has 2 copies of the transgenic construct at 1 integration site. (C) Detection of expression of the transgenic construct by quantitative PCR. The lower panel shows a PCR specific for the transgenic construct, and the upper panel a PCR that detects endogenous Ezh2. (D) Steady-state H3K27me3 and H3K27me2 levels in splenic B cells and sorted B220+IgM+ cells. Nuclear lysates from spleen cells of a mouse transgenic for EZH2Y641F or a WT mouse were probed with an antibody against H3K27me3. Levels of H3 were used as a loading control for histones.

In order to confirm the expression of the transgene, we analyzed transgenic mice by using a quantitative PCR-based approach that specifically detected the human EZH2 sequence. Using this approach, we showed that the transgene was expressed both in early (c-Kit+) and late (c-Kit−) developing B cells in the bone marrow of transgenic mice, with the highest expression in the mature B-cell compartment. We also confirmed the expression of the transgene in GC B cells (supplemental Figure 5A). Expression of the transgenic construct was also observed in T cells at a decreased level but was almost completely absent in myeloid cells or cells from control mice. For comparison, we also analyzed the expression of endogenous Ezh2, which was highest in developing B cells and was low in mature B cells. The expression of endogenous Ezh2 does not appear to be affected by the transgene (Figure 1C). Expression analysis of the transgene at the end of the observation period showed a lower expression of the transgene in founder 1 as compared with founder 3 (supplemental Figure 1A).

Transgenic expression of EZH2Y641F induces an increase in H3K27me3 and leads to an increase of the fraction of GC B cells in aged mice

As expected, nuclear extracts from transgenic mice showed higher levels of H3K27me3. This increase is also seen when sorted B220+IgM+ B cells are analyzed. H3K27me2 levels are unchanged (Figure 1D). A higher level of H3K27me3 was observed in founder 3, which also expressed higher levels of the transgene (supplemental Figure 1B). Despite the increase in H3K27me3, no gross histologic or cytological abnormalities in bone marrow, spleen, or peripheral blood were found in the transgenic mice at autopsy at different ages (Figure 2A; supplemental Figure 3A). There were also no major differences in spleen weights (Figure 2B) and in blood counts at different ages (supplemental Figure 2). Immunophenotyping showed no differences in cellular composition of the bone marrow (Figure 2C) or spleen (Figure 2D). Furthermore, a detailed immunophenotypic characterization of the developing B-cell compartment in the bone marrow (supplemental Figure 3) and of mature populations in the spleen (supplemental Figure 4) of 5- to 6-week-old mice revealed no abnormalities.

Basic characterization of transgenic mice. (A) H&E staining (left) and B220 immunohistochemistry of WT and EZH2Y641F mice. (B) Spleen weights of mice transgenic for EZH2Y641F and WT control mice analyzed at different ages. (C) Immunophenotypic analysis of bone marrow cells of EZH2Y641F mice (n = 16) or WT controls (n = 13). (D) Immunophenotypic analysis of spleen cells of EZH2Y641F mice (n = 7) or WT controls (n = 5). Means and standard deviation of the percentages of cells carrying the respective marker are shown. No significant differences were observed. (E) Immunophenotypic analysis of the GC B-cell compartment in the spleen of aged (60-62 weeks), nonimmunized EZH2Y641F mice (n = 5) or WT controls (n = 5) using GL7 and FAS (upper) and CD38 and FAS (lower) (P = .003). Representative flow cytometric plots are shown to the right. Statistical analysis was performed using an unpaired Student t test with Welch’s correction. H&E, hematoxylin and eosin.

Basic characterization of transgenic mice. (A) H&E staining (left) and B220 immunohistochemistry of WT and EZH2Y641F mice. (B) Spleen weights of mice transgenic for EZH2Y641F and WT control mice analyzed at different ages. (C) Immunophenotypic analysis of bone marrow cells of EZH2Y641F mice (n = 16) or WT controls (n = 13). (D) Immunophenotypic analysis of spleen cells of EZH2Y641F mice (n = 7) or WT controls (n = 5). Means and standard deviation of the percentages of cells carrying the respective marker are shown. No significant differences were observed. (E) Immunophenotypic analysis of the GC B-cell compartment in the spleen of aged (60-62 weeks), nonimmunized EZH2Y641F mice (n = 5) or WT controls (n = 5) using GL7 and FAS (upper) and CD38 and FAS (lower) (P = .003). Representative flow cytometric plots are shown to the right. Statistical analysis was performed using an unpaired Student t test with Welch’s correction. H&E, hematoxylin and eosin.

However, we observed a small, but significant increase in the fraction of GC B cells in aged EZH2Y641F transgenic mice. There was an increase from a mean of 0.792% in WT mice to a mean of 1.412% GL7+FAS+ cells in EZH2Y641F mice (P = .003, n = 5, age 60-62 weeks) (Figure 2E). This could also be observed when analyzing for CD38−FAS+ cells (Figure 2E) and when analyzing a set of younger, immunologically mature mice (supplemental Figure 5A). A trend for an increase in GC B cells was also seen when analyzing mice 8 days after immunization with 4-hydroxy-3-nitrophenyl acetyl-keyhole lympet hemocyanin (supplemental Figure 5B).

Neither of the 2 founder mice observed for almost 2 years developed signs of lymphoma. One transgenic mouse analyzed at 60 weeks showed an increase in a B220+CD5+ cell population in spleen and bone marrow (data not shown) potentially indicative of spontaneous lymphoma development. The median survival of EZH2Y641F mice was 716 days for EZH2Y641F mice and 703 days for WT mice (not statistically significant). Some cases of blood abnormalities indicative of hematopoietic malignancies were seen both in WT as well as in EZH2Y641F mice at these advanced ages (supplemental Figure 2).

EZH2Y641F accelerates lymphoma development in combination with Eµ-Myc and alters the immunophenotype of developing lymphomas

As mutations in EZH2 are usually not found in isolation, but often in combination with additional mutations, we next investigated if the transgenic expression of EZH2Y641F accelerated lymphoma development when combined with Myc overexpression. This combination is relevant in lymphoma development as it has previously been demonstrated that “double-hit” lymphomas can carry EZH2 mutations.28 In data sets from our institution, we have seen in a cohort of 92 DLBCLs that 2 of 6 cases with MYC translocations (33%) are also mutated for EZH2 (supplemental Figure 6A).

We therefore crossed our EZH2Y641F with the Eµ-Myc mouse line. All observed mice (n = 20) that were transgenic for both Myc and EZH2Y641F showed highly accelerated development of generalized lymphadenopathy. After a median of 51 days, the mice became moribund or had to be euthanized because of lymphadenopathy impairing movement or causing dyspnea. The disease development was much faster and more synchronous than in the observed Eµ-Myc mice (n = 26), which developed lymphoma after a median of 137.5 days (consistent with the literature for this mouse line). This acceleration in lymphoma development was highly statistically significant (P < .0001 log-rank [Mantel-Cox] test) (Figure 3A). At autopsy, mice showed generalized massive lymphadenopathy including abdominal and thoracic nodal masses, splenomegaly (spleen weight 0.416 ± 0.133 g), and lymphocytosis (white blood cell count 138.5 ± 77.1 × 1000/µL).

EZH2 Y641F accelerates lymphoma development in combination with Eµ-Myc. (A) Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of EZH2Y641F (n = 36), Eµ-Myc (n = 26), Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F (n = 20), and WT control mice (n = 38) (P < .0001 log-rank [Mantel-Cox] test). Mice used for experiments and analyses at defined time points were censored at the time of analysis. (B) H&E staining of a lymph node from an Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F at the time of death. (C) Wright-Giemsa stained blood smear at time of death. (D) H&E staining of liver from an Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F at the time of death showing lymphoma infiltration of the liver. (E) Immunophenotypic analysis of bone marrow (BM) and peripheral blood (PB) samples from an Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F lymphoma mouse at the time of death. (F) Southern blot analysis for clonality of IgH gene rearrangements for Eµ-Myc lymphomas (upper) and Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F lymphomas (lower) was performed by probing EcoRI-digested genomic DNA with a JH4 probe. DNA samples used were from BM, spleen (Sp), and where available lymph node (LN).

EZH2 Y641F accelerates lymphoma development in combination with Eµ-Myc. (A) Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of EZH2Y641F (n = 36), Eµ-Myc (n = 26), Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F (n = 20), and WT control mice (n = 38) (P < .0001 log-rank [Mantel-Cox] test). Mice used for experiments and analyses at defined time points were censored at the time of analysis. (B) H&E staining of a lymph node from an Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F at the time of death. (C) Wright-Giemsa stained blood smear at time of death. (D) H&E staining of liver from an Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F at the time of death showing lymphoma infiltration of the liver. (E) Immunophenotypic analysis of bone marrow (BM) and peripheral blood (PB) samples from an Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F lymphoma mouse at the time of death. (F) Southern blot analysis for clonality of IgH gene rearrangements for Eµ-Myc lymphomas (upper) and Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F lymphomas (lower) was performed by probing EcoRI-digested genomic DNA with a JH4 probe. DNA samples used were from BM, spleen (Sp), and where available lymph node (LN).

Histologically, the architecture of the enlarged lymph nodes appeared to be distorted and exhibited changes resembling Burkitt lymphoma with a diffuse infiltration of medium-sized cells and a starry-sky appearance (Figure 3B). Enlarged blastoid cells could also be observed in the peripheral blood (Figure 3C) and infiltrated other organs, in particular the liver (Figure 3D).

Immunophenotyping showed that all Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F lymphomas were of B-cell origin. All 9 lymphomas analyzed exhibited a B220+IgM+ phenotype (Figure 3E). This is in striking contrast to the Eµ-Myc lymphomas where 5 of the 9 analyzed lymphomas had a B220+IgM− phenotype.

To investigate the clonality of the developing lymphoma based on V(D)J rearrangements, we performed Southern blot analysis using a probe specific for JH4 on samples from the bone marrow, spleen, and, for selected samples, lymph nodes of 9 Eµ-Myc mice and 9 Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F mice (Figure 3F). Sixteen of the analyzed mice showed at least 1 dominant clonal rearrangement in this analysis. There were 2 Eµ-Myc mice that showed no rearrangement and had an immunophenotype indicative of a very early differentiation stage (B220+Sca1+CD4+). Of the other 7 Eµ-Myc mice, 3 had only 1 clonal rearrangement, 2 showed 2 clonal rearrangements, and there was 1 mouse each that had 3 and >3 clonal bands. Of the 9 Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F, only 2 showed 1 clone, 3 had 2 clones, and 2 mice each had 3 and >3 clones. The Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F mice analyzed appear to have a higher number of different detectable bands indicative of a greater clonal complexity in their lymphomas.

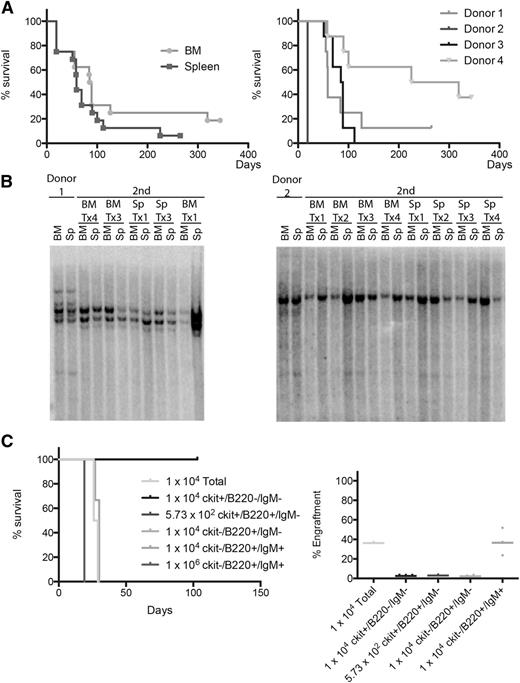

Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F lymphomas initiate disease in secondary recipients

To test if cells from the lymphomas could initiate disease in a secondary recipient, we transplanted 1 × 106 cells isolated from the bone marrow and spleen of 4 different diseased animals into sublethally irradiated recipient mice. Recipient mice developed lymphoma after a median of 87 days for bone marrow cells and 59 days for spleen cells (not statistically significant). The median latency varied with different donor mice between a median of 19 days and 272 days (Figure 4A). Southern blot analysis of 2 donor-recipient pairs showed that donor and recipient mice exhibited very similar patterns of V(D)J rearrangements with some minor shifts in clonal composition (Figure 4B). To determine the transplantable population, we then sorted different stages of B-cell development (ckit+B220+IgM−, ckit−B220+IgM−, and ckit−B220+IgM+) and progenitor cells (ckit+B220−IgM−) from the bone marrow of the secondary recipients and transplanted them into sublethally irradiated mice. In this setting, 1 × 104 B220+IgM+ were sufficient to induce rapid-onset lymphoma development, whereas none of the more immature populations showed engraftment in the recipient animals. Together with the conserved V(D)J rearrangement upon transplantation, these data suggest that the lymphoma-maintaining population is in the developed B-cell compartment (Figure 4C).

Transplantability of Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F lymphomas. (A) Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of mice transplanted with BM or spleen cells from 4 different Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F donor mice with lymphoma. Transplants were injected into sublethally irradiated mice. Different donor mice exhibited different kinetics of lymphoma development in the secondary recipients independent of the cell source. (B) Southern blot analysis of IgH gene rearrangements for 2 different primary Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F lymphoma mice and secondary recipients. The pattern of clonal rearrangements is maintained between primary and secondary lymphoma mice. (C) Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of mice transplanted with sorted BM cells from a secondary recipient mouse. Transplanted cell number and population are indicated. Only mice transplanted with unsorted BM cells and B220+IgM+ cells showed engraftment. Engraftment was measured by flow cytometry in the peripheral blood after staining for CD45.2.

Transplantability of Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F lymphomas. (A) Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of mice transplanted with BM or spleen cells from 4 different Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F donor mice with lymphoma. Transplants were injected into sublethally irradiated mice. Different donor mice exhibited different kinetics of lymphoma development in the secondary recipients independent of the cell source. (B) Southern blot analysis of IgH gene rearrangements for 2 different primary Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F lymphoma mice and secondary recipients. The pattern of clonal rearrangements is maintained between primary and secondary lymphoma mice. (C) Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of mice transplanted with sorted BM cells from a secondary recipient mouse. Transplanted cell number and population are indicated. Only mice transplanted with unsorted BM cells and B220+IgM+ cells showed engraftment. Engraftment was measured by flow cytometry in the peripheral blood after staining for CD45.2.

Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F mice show a shift in B-cell differentiation in the bone marrow and accumulate transitional B cells

We observed a remarkable shift regarding the differentiation state of the developing lymphomas between Eµ-Myc and Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F mice, prompting us to investigate if an alteration of B-cell development could also be observed at earlier time points in the course of lymphoma development. We therefore analyzed the composition of the developing B-cell compartment in the bone marrow and mature B-cell compartments in the spleen of WT, EZH2Y641F, Eµ-Myc, and Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F mice at 5 to 7 weeks of age (before the development of overt lymphoma). During this period, the analyzed Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F mice already exhibited a high level of lymphocytosis (supplemental Figure 7) and splenomegaly (supplemental Figure 8B) and enlarged lymph nodes.

Eµ-Myc mice had an increased fraction of B220+IgM− (large) cells in the bone marrow (Figure 5A), whereas the percentage of B220+IgM+ cells decreased, even when compared with WT mice (Figure 5C). In striking contrast, we observed an increase in the total B220+ (Figure 5B) and the B220+IgM+ compartment in Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F mice (Figure 5C). A similar accumulation of B220+IgM+ cells could also be found in the spleen (supplemental Figure 8C). The B220+IgM+ cells showed a low expression of IgD (Figure 5D), were negative for CD21 and CD23 (supplemental Figure 8D), and expressed AA4.1 (Figure 5E and supplemental Figure 8E). This marker combination is consistent with the transitional stage (T1) of B-cell development. There were no significant changes to the pro- and pre-B-cell compartment (Figure 5F).

Immunophenotypic characterization of the B-cell compartment in Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F mice. (A) Wright-Giemsa stained cytospins from bone marrow of Eµ-Myc and Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F mice. Images were taken at ×40. (B) Immunophenotypic analysis of bone marrow cells of Eµ-Myc (n = 14) or Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F (n = 13) mice. (C) Immunophenotypic analysis of the bone marrow of Eµ-Myc (n = 8) and Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F mice (n = 8) for B220 and IgM. Representative flow cytometric plots are shown and a quantification of the data with means and standard deviations. (D) Immunophenotypic analysis of B220+IgM+ cells in the bone marrow of Eµ-Myc (n = 8) and Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F mice (n = 8) for expression of IgD. (E) Immunophenotypic analysis of B220+IgM+ cells in the bone marrow of Eµ-Myc (n = 8) and Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F mice (n = 8) for expression of AA4.1. (F) Immunophenotypic analysis of the pro- (B220+IgM−CD43+) and pre-B-cell (B220+IgM−CD43−) compartment in the bone marrow of Eµ-Myc (n = 8) and Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F mice (n = 8).

Immunophenotypic characterization of the B-cell compartment in Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F mice. (A) Wright-Giemsa stained cytospins from bone marrow of Eµ-Myc and Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F mice. Images were taken at ×40. (B) Immunophenotypic analysis of bone marrow cells of Eµ-Myc (n = 14) or Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F (n = 13) mice. (C) Immunophenotypic analysis of the bone marrow of Eµ-Myc (n = 8) and Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F mice (n = 8) for B220 and IgM. Representative flow cytometric plots are shown and a quantification of the data with means and standard deviations. (D) Immunophenotypic analysis of B220+IgM+ cells in the bone marrow of Eµ-Myc (n = 8) and Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F mice (n = 8) for expression of IgD. (E) Immunophenotypic analysis of B220+IgM+ cells in the bone marrow of Eµ-Myc (n = 8) and Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F mice (n = 8) for expression of AA4.1. (F) Immunophenotypic analysis of the pro- (B220+IgM−CD43+) and pre-B-cell (B220+IgM−CD43−) compartment in the bone marrow of Eµ-Myc (n = 8) and Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F mice (n = 8).

EZH2Y641F changes the expression of multiple genes and thereby affects multiple important pathways in B-cell regulation by altering histone marks

To explore the mechanism for EZH2Y641F and Myc interaction, we investigated if Ezh2 and Myc expression were altered in the mouse model and if there was an impact on H3K27me3. We therefore sorted B220+IgM+ cells from WT, EZH2Y641F, Eµ-Myc, and Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F mice and saw elevated Ezh2 in the Eµ-Myc model and increased expression of both Myc and Ezh2 with the combination. However, there was no significant global increase in H3K27me3 with the combination (supplemental Figure 9). There is also a very slight positive correlation (Spearman correlation: 0.23, P < .05) between EZH2 and MYC expression in our cohort of DLBCL patients (n = 92) (supplemental Figure 6B). These results suggest that the combined effect of EZH2Y641 mutation and Myc may extend beyond modulation of H3K27Me3.

In an attempt to identify specific genes and pathways affected by the EZH2Y641F transgene, we then combined a global gene expression analysis by RNA sequencing with a global analysis of the histone marks H3K27me3 and H3K4me3. B220-positive cells (1 × 107) isolated from the spleens of Eµ-Myc and Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F mice were used for RNA sequencing, and 1 × 107 cells were used for ChIP for H3K27me3 and H3K4me3. In order to identify differentially expressed genes, we first focused on the RNA sequencing data. Of the 22 137 genes studied, we observed 1112 (412) downregulated and 788 (209) upregulated genes in Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F mice with P < .05 (false discovery rate <0.1) when only genes with reads per kilobase of gene model per million mapped reads >0.05 and a minimum number of reads of 30 were considered (supplemental Figure 10A). We performed pathway analysis of the differentially expressed genes in Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F using the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID), the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes and Model-based Gene Set Analysis (supplemental Tables 1 and 2). Interestingly, this analysis returned many important pathways in B-cell regulation and function. Significant pathways in the DAVID analysis included the B-cell receptor signaling pathway, the phosphatidylinositol signaling system, as well as antigen presentation (supplemental Figure 10B). Only 1 general pathway (hematopoietic cell lineage) and 1 pathway without a direct role in B-cell function (steroid biosynthesis) were returned when analyzing the upregulated genes.

We then analyzed how changes in H3K27me3 and H3K4me3 correlated with EZH2Y641F. Of all protein-coding genes (Ensembl v65) analyzed with stringent threshold, 692 genes lost H3K27me3, 133 genes gained H3K27me3, 387 genes lost H3K4me3, and 109 genes gained H3K4me3 in Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F (supplemental Table 3). The identified histone marks correlated with expression (supplemental Figure 10C). Genes downregulated in the Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F mouse showed increased H3K27me3 marks and decreased H3K4me3 marks at their transcription start site indicative of a fraction of these genes being regulated by these marks. In contrast, genes that were upregulated in the Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F mouse exhibit increased H3K4Me3 marks and decreased H3K27me3 marks at their transcription start site. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov P value for all pairwise comparisons between the 3 distributions was significant (supplemental Figures 10D and 11). On an individual gene basis, differentially expressed genes generally displayed histone marks that corresponded to their silenced or activated state (supplemental Table 4).

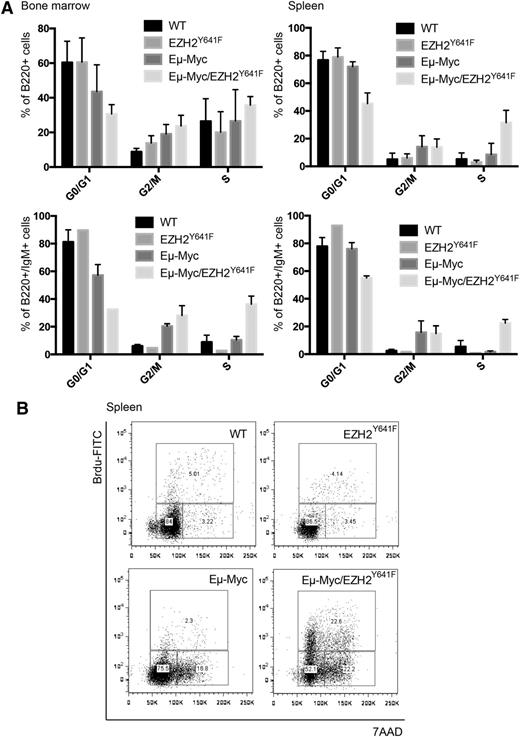

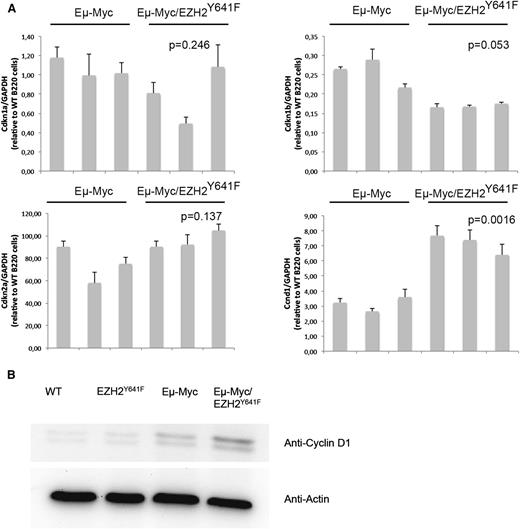

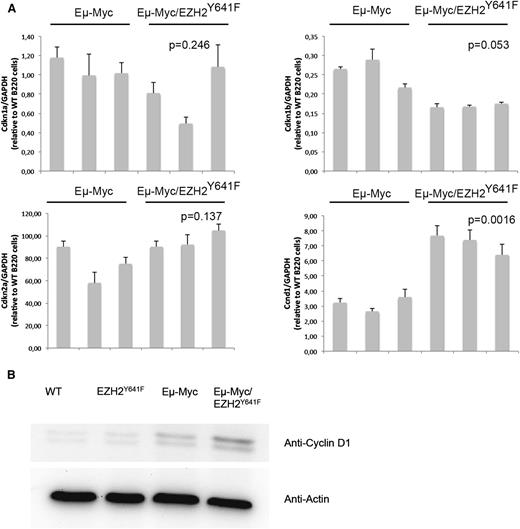

EZH2Y641F induces a marked increase in the proliferation rate of B220+IgM+ cells

Both Myc and Ezh2 are known to be critically involved in proliferation. WT, EZH2Y641F, Eµ-Myc, and Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F mice were injected with 5-bromo-2'-deoxyuridine (BrdU), and cell-cycle distribution in the B-cell compartment was assessed 16 hours later. This analysis showed a major increase in proliferation in double transgenic mice (Figure 6A). The difference was more pronounced and highly statistically significant when focusing on splenic B cells and cells that are B220+IgM+, which seem to be nearly quiescent in WT mice (Figure 6A-B). We therefore performed quantitative PCRs for cell-cycle regulators influenced by EZH2 in B cells (Cdkn1a, Cdkn1b, and Cdkn2a).29 We found a trend toward a decreased expression of Cdkn1b (Figure 7). We next investigated our global gene expression data for genes related to cell-cycle regulation by intersecting our lists of differentially expressed genes with genes related to cell-cycle in the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes and Gene Ontology (supplemental Table 5). Although there was no strong overlap, the identified genes appear to have a functional role in lymphomagenesis and include Cyclin D1, which was confirmed on the RNA and protein level (Figure 7).

EZH2Y641F enhances proliferation in combination with Eµ-Myc. (A) Quantitative analysis of the cell-cycle distribution in the bone marrow and spleen of WT, EZH2Y641F, Eµ-Myc, and Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F mice based on in vivo BrdU incorporation. Analysis was based on flow cytometry and gated on the respective subpopulation. (B) Representative flow cytometric plots analyzed for 7-aminoactinomycin D (7AAD) and BrdU gated on B220+ spleen cells in WT, EZH2Y641F, Eµ-Myc, and Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F mice.

EZH2Y641F enhances proliferation in combination with Eµ-Myc. (A) Quantitative analysis of the cell-cycle distribution in the bone marrow and spleen of WT, EZH2Y641F, Eµ-Myc, and Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F mice based on in vivo BrdU incorporation. Analysis was based on flow cytometry and gated on the respective subpopulation. (B) Representative flow cytometric plots analyzed for 7-aminoactinomycin D (7AAD) and BrdU gated on B220+ spleen cells in WT, EZH2Y641F, Eµ-Myc, and Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F mice.

Differential expression of the cell-cycle regulator Cyclin D1 in EZH2Y641F mice. (A) Quantitative PCR for different cell-cycle regulators (Cdkn1a, Cdkn1b, and Cdkn2a) known to be regulated by EZH2 and Cyclin D1 (Ccnd1) was performed on sorted B220+ cells from the spleen of Eµ-Myc (n = 3) and Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F (n = 3) mice. Expression results are normalized to expression of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and expressed relative to the expression in B220 cells from a WT mouse. The P value was calculated using a Student t test. (B) Western blot analysis for the expression of Cyclin D1 in the spleen of WT, EZH2Y641F, Eµ-Myc, and Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F mice. Actin is shown as loading control.

Differential expression of the cell-cycle regulator Cyclin D1 in EZH2Y641F mice. (A) Quantitative PCR for different cell-cycle regulators (Cdkn1a, Cdkn1b, and Cdkn2a) known to be regulated by EZH2 and Cyclin D1 (Ccnd1) was performed on sorted B220+ cells from the spleen of Eµ-Myc (n = 3) and Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F (n = 3) mice. Expression results are normalized to expression of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and expressed relative to the expression in B220 cells from a WT mouse. The P value was calculated using a Student t test. (B) Western blot analysis for the expression of Cyclin D1 in the spleen of WT, EZH2Y641F, Eµ-Myc, and Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F mice. Actin is shown as loading control.

Discussion

We have generated a transgenic mouse line carrying mutant EZH2. As expected, this mouse line exhibits increased levels of H3K27me3. EZH2 has recently been demonstrated to be essential for the GC reaction.30 Similar to these observations, we can confirm that the gain of function of EZH2 in our mouse model also causes an increase in the frequency of GC B cells in aged mice and a tendency toward an enhanced GC reaction upon immunization with 4-hydroxy-3-nitrophenyl acetyl-keyhole lympet hemocyanin.

When we combined the transgenic expression of EZH2Y641F with Myc, a clear acceleration in lymphoma development occurred. These data show that EZH2Y641F can collaborate with Myc for high-efficiency lymphoma induction. EZH2 mutations are usually not found in isolation but frequently occur with other mutations in both follicular lymphoma and DLBCL. Lymphomas carrying EZH2 mutations often show a simultaneous activation of BCL228 ; the latter is the result of translocation to the IGH enhancer region. Other lesions found to coincide with mutations in EZH2 include mutations in GNA13, MEF2B, TP53, and TNFRSF14.18 Although MYC translocations are mainly observed in Burkitt lymphomas, there is also a subgroup of DLBCL that shows activation of MYC.31 In our patient cohort, we have observed that some of these lymphomas simultaneously carry EZH2 mutations. We therefore believe that the observations made in our mouse model may represent novel, relevant mechanisms in development of aggressive lymphomas.

A collaborative action of EZH2 mutations has also recently been described when mutant EZH2 was combined with BCL2 overexpression and repetitive immunization,30 which may drive proliferation. Ezh2 has been shown to be mainly expressed in developing and proliferating normal tissues,4,32 and it has been implicated in cancer cell proliferation.8,33 An association of EZH2 expression with proliferating cell types has also been observed,12 and it has been shown to be critical in B-cell lymphoma proliferation. Interestingly, the cell line used in these experiments (SU-DHL-4) harbors an EZH2Y641S mutation.29 We observed an increase in the proliferation rate of developed B cells in the spleen when we compared Eµ-Myc and Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F mice. Among the differentially expressed genes was Ccnd1. It is involved in lymphoma development, and its expression appears to be promoted by EZH2.34 Our transgenic mouse model may thus represent a novel tool to identify target genes of EZH2 and pathways that mediate this role of EZH2 in B-cell proliferation.

We observed that in addition to the acceleration of lymphoma development, EZH2Y641F alters the differentiation stage of the developing lymphomas. In mice, a loss of function of Ezh2 has been shown to negatively affect the ability of developing B cells to rearrange their B-cell receptor. This leads to a block in differentiation at the pro- to pre-B-cell transition, which results in phenotypic changes that are contrary to the phenotypic changes observed in our mice.5 We therefore hypothesized that a gain of function may positively affect the ability of B cells to undergo differentiation. Although Eµ-Myc mice more frequently developed immature B-cell lymphomas not expressing IgM, all of the lymphomas observed in Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F mice showed a transitional B-cell phenotype expressing IgM. Other groups have found similar phenotypic changes when studying the combination of Eµ-Myc with other polycomb-group genes such as Bmi1 or Cbx7 that also accelerate lymphoma development on the Eµ-Myc background.35-37 Our model system may allow further characterization of how this change in differentiation is related to the acceleration of lymphoma development. Lee et al recently showed that depletion of polycomb repressive complex 2 function is also capable of enhancing the development of Eµ-Myc lymphomas.38 In contrast to our study with a gain of function of EZH2, their study showed no shift in differentiation and no increase in proliferation.

In summary, our transgenic model system provides the first functional evidence for a collaboration of Myc and EZH2 in the development of lymphoma. In addition to lymphoid malignancies, EZH2 mutations have also recently been identified in parathyroid tumors.39 Our data represent further evidence that targeting EZH2 may represent a specific treatment of EZH2-mutated lymphoma. The described gain-of-function mutations are in contrast to mutations of EZH2 that occur in myeloproliferative neoplasms and myelodysplastic syndromes.40,41 These are frequently frameshift, nonsense, and missense mutations, often involving both alleles and have been confirmed to cause a loss of function of EZH2. Interestingly, several groups have also recently documented inactivating EZH2 mutations in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia.42-44 Therefore, it seems that EZH2 is associated with lymphoid malignancies by gain-of-function mutations as well as by loss of expression. Our model may be helpful in investigating this paradox.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Marika Nimz, Johannes Wicht, and Justin Smrz for excellent help in performing the experiments.

This work was supported by grants from the Terry Fox Foundation, Canada and the Leukemia Lymphoma Society of Canada; the LOEWE programs “Onkogene Signaltransduktion Frankfurt” and “Center for Cell and Gene Therapy Frankfurt” funded by Hessisches Ministerium für Wissenschaft und Kunst; a Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft fellowship (BE 4198/1-1) (T.B.); a scholarship by the Hanns-Seidel-Stiftung e.V. (N.S.); and the National Cancer Institute of Canada, Terry Fox Foundation Program Project (grant # 019001) (R.D.G.).

Authorship

Contribution: T.B., R.D.M., M.H., H.S., M.A.M., G.B.M., R.D.G., S.A.A., and R.K.H. designed the research; T.B., S.T., D.Y., P.R., T.W., N.S., T.O., S.L., E.L., M.B., A.J.M., P.U., A.S., H.C., L.Y., D.L., C.K.L., and S.-W.G.C. performed the research; T.B. and R.K.H. analyzed the data; T.B. and R.K.H. wrote the paper; and all authors checked the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: R. Keith Humphries, Terry Fox Laboratory, BC Cancer Agency, 675 West 10th Ave, Vancouver, BC V5Z 1L3, Canada; e-mail: khumphri@bccrc.ca.

![Figure 3. EZH2 Y641F accelerates lymphoma development in combination with Eµ-Myc. (A) Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of EZH2Y641F (n = 36), Eµ-Myc (n = 26), Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F (n = 20), and WT control mice (n = 38) (P < .0001 log-rank [Mantel-Cox] test). Mice used for experiments and analyses at defined time points were censored at the time of analysis. (B) H&E staining of a lymph node from an Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F at the time of death. (C) Wright-Giemsa stained blood smear at time of death. (D) H&E staining of liver from an Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F at the time of death showing lymphoma infiltration of the liver. (E) Immunophenotypic analysis of bone marrow (BM) and peripheral blood (PB) samples from an Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F lymphoma mouse at the time of death. (F) Southern blot analysis for clonality of IgH gene rearrangements for Eµ-Myc lymphomas (upper) and Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F lymphomas (lower) was performed by probing EcoRI-digested genomic DNA with a JH4 probe. DNA samples used were from BM, spleen (Sp), and where available lymph node (LN).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/123/25/10.1182_blood-2012-12-473439/4/m_3914f3.jpeg?Expires=1765065638&Signature=bCqHUV3jPvgMEClAiEhoiUS77vuX0XRhX8~DbZkju34XHtDmUVYU6339mZZRVtetEGALCjjnYxZLFP53yytWO1-VcrzB7fr9n0ZLsbtPqCPIHBDMnCo~fzwYYmJB-zOq733NGcInojaotebygQDPg4X07Qd4CxoTx2FQVnPT9y82gQjH-A8AowrBSTAJYUpKPahcJVIUkxqFGrvV2H5FFRdddDsF~CRrreeLKqi2hj1GBvde43D0qkBPuD2d5RnhPYd1fKBYoSavEoefhROxcDYA3Q7rFfNc74CPfTN6eHBf9pQPhAtMiEaRmrF55TXBqf8z4uVLUHCpW1GF8HR4Ew__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 3. EZH2 Y641F accelerates lymphoma development in combination with Eµ-Myc. (A) Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of EZH2Y641F (n = 36), Eµ-Myc (n = 26), Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F (n = 20), and WT control mice (n = 38) (P < .0001 log-rank [Mantel-Cox] test). Mice used for experiments and analyses at defined time points were censored at the time of analysis. (B) H&E staining of a lymph node from an Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F at the time of death. (C) Wright-Giemsa stained blood smear at time of death. (D) H&E staining of liver from an Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F at the time of death showing lymphoma infiltration of the liver. (E) Immunophenotypic analysis of bone marrow (BM) and peripheral blood (PB) samples from an Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F lymphoma mouse at the time of death. (F) Southern blot analysis for clonality of IgH gene rearrangements for Eµ-Myc lymphomas (upper) and Eµ-Myc/EZH2Y641F lymphomas (lower) was performed by probing EcoRI-digested genomic DNA with a JH4 probe. DNA samples used were from BM, spleen (Sp), and where available lymph node (LN).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/123/25/10.1182_blood-2012-12-473439/4/m_3914f3.jpeg?Expires=1765178957&Signature=szIMiy4q4Thu-W4qEj0alkw8IAUpGz73Qyw4wBrfcfzlOIlz1IZDS2hqL-t03hZafTPzem5jEWE-sbUkDINnMr6tDR6dqvvQiiYBBGPEz6rwbf0Ee-gzQh6gvNGpGU76yWrBr93fJ6RKJcczxfIZNOkrK~RHPhg8vaQkFzkUHMXN~ULzo3xF-JPfCO4tTwB0fHF7J8uhlUQJsrEtcSMgvCeyhg5ibZiWivNnl~np9fipmNp2tVn2DX2BA092LeEsqoI4CNdQa5byZLif6Aq~LgN5q0t513kUp85L~jjHYJcvK7ibn6xF0unxpHCKydIXAgmwxkUbvtozA6-7O3nU~A__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)