Key Points

DNA damage induced by telomere shortening resides in most quiescent HSCs.

Senescence and apoptosis compromise the activation of HSCs with dysfunctional telomeres.

Abstract

Telomere shortening limits the proliferative capacity of human cells, and age-dependent shortening of telomeres occurs in somatic tissues including hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs). It is currently unknown whether genomic and molecular damage that occurs in HSCs induced by telomere shortening is transmitted to the progenitor cells. Here we show that telomere shortening results in DNA damage accumulation and gene expression changes in quiescent HSCs of aged mice. Upon activation, a subset of HSCs with elevated levels of DNA damage and p16 expression are blocked from cell cycle entry, and apoptosis is induced in HSCs entering the cell cycle. Activation of both checkpoints associates with normalization of DNA damage and gene expression profiles at early progenitor stages. These findings indicate that quiescent HSCs have an elevated tolerance to accumulate genomic alterations in response to telomere shortening, but the transmission of these aberrations to the progenitor cell level is prevented by senescence and apoptosis.

Introduction

Telomere shortening limits the proliferative capacity of human cells and may contribute to aging-associated decline in hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) function.1-5 Studies on DNA repair–deficient mice and telomerase knockout mice revealed that DNA damage accumulates in the HSC compartment and limits the functionality of HSCs by induction of DNA damage checkpoints.6,7 Recent studies indicated that DNA damage is repaired when HSCs enter the cell cycle.8 However, telomere-free chromosome ends cannot easily be repaired because telomerase recruitment requires telomere repeats.9,10 Moreover, the formation of chromosomal fusion represents an aberrant repair pathway that interferes with maintenance of chromosomal integrity in dividing cells.11 Whether telomere shortening–induced DNA damage leads to accumulation of DNA damage and gene expression changes in HSCs, and whether these alterations are transmitted to hematopoietic progenitor cells, is currently unknown.

Study design

Animals

All mice used are C57BL/6 background. mTerc+/− were crossed to generate G1 mTerc−/−. mTerc−/− mice were crossed until the third generation (G3mTerc−/−). Mice were maintained and experiments were conducted according to protocols approved by the state government of Thuringia, Germany (Reg. No. 03-006/13).

Isolation of cells

Bone marrow cells were isolated by crushing bones from donor mice. Cells were stained and sorted by using the following surface markers combination: HSCs (CD34loFlt3−ScaI+cKit+Lineage−), multipotent progenitor cells (MPPs; CD34+Flt3+ScaI+cKit+Lineage−), and myeloid cells (CD11b+). Quiescent HSCs and cycling HSCs were purified by using Pyronin Y (P9172; Sigma-Aldrich) and Hoechst33342 (B2261; Sigma-Aldrich). Bone marrow cells were stained with antibodies for HSCs first, then incubated with Hoechst33342 (DNA dye, 1 mg/mL) at 37°C for 30 minutes and Pyronin Y (RNA dye, 100 μg/mL) for a further 15 minutes under light-free conditions. Samples were analyzed by ARIA (BD Biosciences).

Comet assays

Comet assays were conducted by using the OxiSelect Comet Assay Kit according the manufacturer’s protocol. HSCs were sorted into ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with the concentration 1 × 105 cells per mL and fixed onto the OxiSelect Comet together with Comet Agarose. Then, electrophoresis was applied, and Vista Green DNA Dye was used to develop tails.

Result and discussion

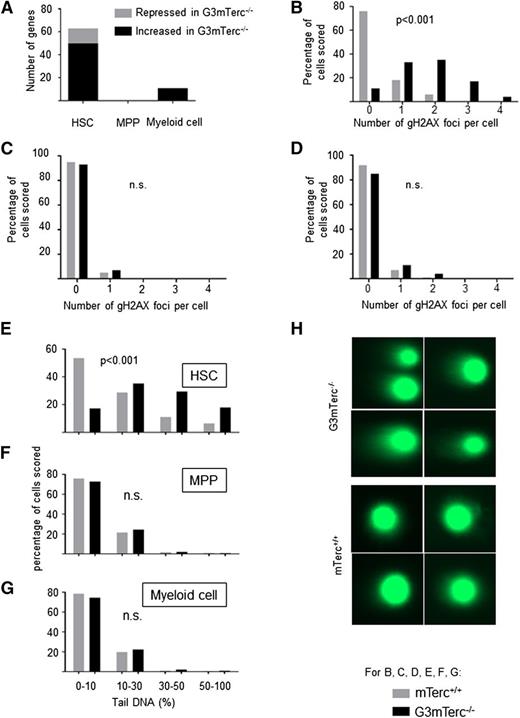

Telomere dysfunction induces DNA damage accumulation and gene expression changes in quiescent HSCs but not at the progenitor cell level

To analyze gene expression changes in response to telomere shortening, HSCs (CD34−Flt3−Sca1+c-kit+Lineage−), MPPs (CD34+Flt3+Sca1+c-kit+Lineage−), and myeloid cells (CD11b+) were freshly isolated from 12-month-old G3mTerc−/− mice and age-matched mTerc+/+ mice (supplemental Table 1; see the Blood Web site). Gene expression profiling (original profiles were uploaded to Gene Expression Omnibus: GSE60164) revealed that 63 genes (fold change >2, P < .05) were differentially regulated in telomere dysfunctional HSCs compared with mTerc+/+ HSCs (Figure 1A). In contrast, the comparison of gene expression from mTerc+/+ vs G3mTerc−/− revealed no differentially expressed genes at the level of MPPs and only 11 genes at the level of myeloid cells (supplemental Table 2; Figure 1A). Among the 63 genes differentially expressed in HSCs from G3mTerc−/− compared with mTerc+/+ mice, several DNA damage–related or apoptosis-related genes were present (highlighted in Figure 1A).

DNA damage and gene expression changes in response to telomere shortening accumulate in quiescent HSCs but not in hematopoietic progenitors and myeloid cells. (A) The histogram shows the number of genes that are differentially expressed in HSCs, MPPs, and myeloid cells isolated from 12-month-old G3mTerc−/− compared with age-matched mTerc+/+ mice. Fifty to 200 freshly isolated cells were used for the analysis of gene expression profiles (n = 6-7 mice per group). Several DNA damage–related or apoptosis-related genes were differentially expressed in HSCs between G3mTerc−/− compared with age-matched mTerc+/+ mice, including Polq (polymerase, θ), Fancc (Fanconi anemia, complementation group C), Rb1 (Retinoblastoma 1), Ccdc14 (coiled-coil domain containing 14), Bmf (Bcl2 modifying factor), Aatf (apoptosis antagonizing transcription factor), Hspa12b (heat shock protein A12B), Anxa9 (Annexin 9), Ddx10 (Dead box 10), Dact2 (Dapper homolog 2), Rbm10 (RNA binding motif protein 10), Map3k12 (mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 12), and Socs6 (suppressor of cytokine signaling 6). (B-G) To analyze DNA damage, HSCs, MPPs, and myeloid cells from 12-month-old G3mTerc−/− mice and mTerc+/+ mice were freshly isolated for DNA damage quantification assay including γH2AX staining and alkaline comet assay. (B-D) The histograms show the percentage of cell nuclei staining positive for the indicated numbers of γH2AX foci in HSCs (B), MPPs (C), and myeloid cells (D) (100 nuclei were counted per cell type and group). (E-G) DNA fragmentation was analyzed using the alkaline comet assay. Fragmented DNA is visualized as a tail moving out of the gel-embedded nuclei. More than 500 HSCs, MPPs, and myeloid cells from G3mTerc−/− and mTerc+/+ mice were scored by alkaline comet assay. The histogram shows the distribution of tail DNA percentage of HSCs (E), MPPs (F), and myeloid cells (G) from 12-month-old G3mTerc−/− and age-matched mTerc+/+ mice (n > 500 nuclei per group). (H) Representative images of HSCs from 12-month-old G3mTerc−/− and age-matched mTerc+/+ mice analyzed by the alkaline comet assay.

DNA damage and gene expression changes in response to telomere shortening accumulate in quiescent HSCs but not in hematopoietic progenitors and myeloid cells. (A) The histogram shows the number of genes that are differentially expressed in HSCs, MPPs, and myeloid cells isolated from 12-month-old G3mTerc−/− compared with age-matched mTerc+/+ mice. Fifty to 200 freshly isolated cells were used for the analysis of gene expression profiles (n = 6-7 mice per group). Several DNA damage–related or apoptosis-related genes were differentially expressed in HSCs between G3mTerc−/− compared with age-matched mTerc+/+ mice, including Polq (polymerase, θ), Fancc (Fanconi anemia, complementation group C), Rb1 (Retinoblastoma 1), Ccdc14 (coiled-coil domain containing 14), Bmf (Bcl2 modifying factor), Aatf (apoptosis antagonizing transcription factor), Hspa12b (heat shock protein A12B), Anxa9 (Annexin 9), Ddx10 (Dead box 10), Dact2 (Dapper homolog 2), Rbm10 (RNA binding motif protein 10), Map3k12 (mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 12), and Socs6 (suppressor of cytokine signaling 6). (B-G) To analyze DNA damage, HSCs, MPPs, and myeloid cells from 12-month-old G3mTerc−/− mice and mTerc+/+ mice were freshly isolated for DNA damage quantification assay including γH2AX staining and alkaline comet assay. (B-D) The histograms show the percentage of cell nuclei staining positive for the indicated numbers of γH2AX foci in HSCs (B), MPPs (C), and myeloid cells (D) (100 nuclei were counted per cell type and group). (E-G) DNA fragmentation was analyzed using the alkaline comet assay. Fragmented DNA is visualized as a tail moving out of the gel-embedded nuclei. More than 500 HSCs, MPPs, and myeloid cells from G3mTerc−/− and mTerc+/+ mice were scored by alkaline comet assay. The histogram shows the distribution of tail DNA percentage of HSCs (E), MPPs (F), and myeloid cells (G) from 12-month-old G3mTerc−/− and age-matched mTerc+/+ mice (n > 500 nuclei per group). (H) Representative images of HSCs from 12-month-old G3mTerc−/− and age-matched mTerc+/+ mice analyzed by the alkaline comet assay.

γH2AX staining (a marker of DNA breaks) revealed a significant increase of DNA damage in freshly isolated HSCs (Figure 1B), but not in MPPs and myeloid cells between G3mTerc−/− and mTerc+/+ mice (Figure 1C-D). Similar results were obtained for 53BP1 staining (data not shown). Furthermore, analysis of DNA breakage by the comet assay revealed that 47% of the HSCs from G3mTerc−/− mice carried more than 30% DNA in comet tails compared with only 18% of HSCs from mTerc+/+ mice (Figure 1E, P < .001), but no significant difference in MPPs and myeloid cells from G3mTerc−/− compared with mTerc+/+ mice (Figure 1F-G).

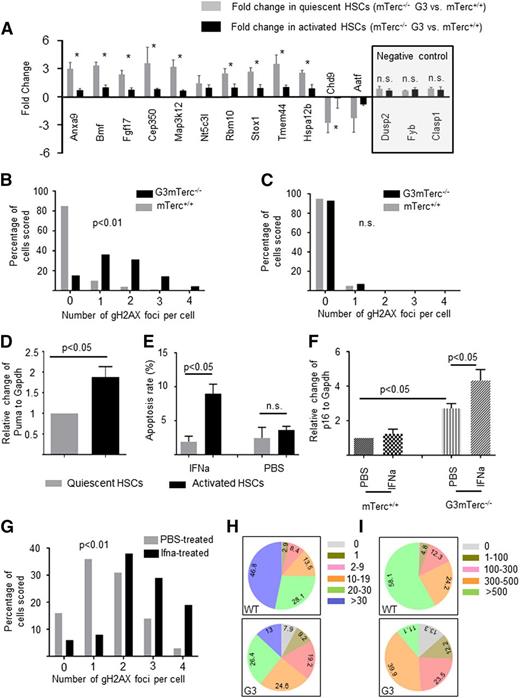

Apoptosis and senescence limit survival and cell cycle entry of quiescent telomere dysfunctional HSCs

The previous results indicated that HSCs accumulate DNA damage and gene expression changes in response to telomere dysfunction, but these alterations are not transmitted to the progenitor cell level. To determine at what stage HSCs amass the alterations, 12 genes that are differentially expressed in HSCs between G3mTerc−/− and mTerc+/+ mice were selected (based on a reported high expression level in the HSC compartment12 ) to be investigated in quiescent and cycling HSCs from G3mTerc−/− compared with mTerc+/+ mice (n = 11-13 mice per group pooled into 2 pools per group). The results revealed that most of the gene expression changes were present in quiescent HSCs but not in cycling HSCs (Figure 2A; n = 3 technical repeats, n = 2 pools per group). The higher magnitude of gene expression changes in quiescent compared with cycling HSCs correlated with a significantly elevated rate of DNA damage foci in quiescent vs cycling HSCs from G3mTerc−/− compared with mTerc+/+ mice (Figure 2B-C). Together, these results indicated that only the nondamaged HSCs contributed to the pool of cycling HSCs in aged telomere dysfunctional mice.

DNA damage and gene expression changes are reverted in stimulated, telomere dysfunctional HSCs that enter the cell cycle. (A-C) To analyze gene expression and DNA damage in quiescent and cycling HSCs under homeostatic conditions, HSCs were freshly isolated from 12-month-old, nonstimulated G3mTerc−/− mice and mTerc+/+ mice: quantitative polymerase chain reaction analysis of differentially expressed genes in G0-HSCs (gray bars) and G1/S/G2/M HSCs (black bars) (A). Note that gene expression differences between HSCs of G3mTerc−/− mice and mTerc+/+ mice were more pronounced in quiescent HSCs. Three genes (Dusp2, Fyb, and Clasp1), which were not differentially regulated in gene array analysis of HSCs from G3mTerc−/− compared with mTerc+/+ mice, were chosen as negative control (A, right). Values are shown as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). *P < .05. (B-C) The histograms show the percentage of cell nuclei staining positive for the indicated numbers of γH2AX foci in quiescent HSCs (B) and cycling HSCs (C) (100 nuclei were counted per cell type and group) of G3mTerc−/− and mTerc+/+ mice. (D-E) Twelve-month-old G3mTerc−/− mice were treated with interferon-α to stimulate cell cycle activity (supplemental Figure 1A-B). Interferon-α (10 000 U per mouse) or PBS was injected into 12-month-old G3mTerc−/− mice intraperitoneally. Freshly isolated bone marrow cells were analyzed 16 hours after stimulation. (D) Messenger RNA expression of Puma in cycling HSCs (black bars) compared with quiescent HSCs (gray bars). Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 3 for each group). (E) Rate of apoptosis (annexin V–positive cells) in quiescent HSCs and activated HSCs of G3mTerc−/− mice treated with either PBS or interferon-α. Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 3 mice per group). (F) This histogram shows the relative expression of p16 in quiescent HSCs from 12-month-old G3mTerc−/− and age-matched mTerc+/+ mice treated with PBS or interferon-α. Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 3 mice per group). (G) The histogram shows the percentage of cell nuclei staining of γH2AX foci for quiescent HSCs from G3mTerc−/− mice treated with either PBS (gray bar) or interferon-α (black bar) (100 nuclei were counted per group). (H-I) The pie charts depict the composite of clones generated from freshly isolated single HSCs from 12-month-old G3mTerc−/− (332) and age-matched mTerc+/+ (310) mice. Cell numbers were counted on day 6 (H) and day 12 (I) after plating. HSCs were cultured individually in stem cell medium (Stem Cell Technology) with stem cell factor (30 ng/mL) and thrombopoietin (20 ng/mL).

DNA damage and gene expression changes are reverted in stimulated, telomere dysfunctional HSCs that enter the cell cycle. (A-C) To analyze gene expression and DNA damage in quiescent and cycling HSCs under homeostatic conditions, HSCs were freshly isolated from 12-month-old, nonstimulated G3mTerc−/− mice and mTerc+/+ mice: quantitative polymerase chain reaction analysis of differentially expressed genes in G0-HSCs (gray bars) and G1/S/G2/M HSCs (black bars) (A). Note that gene expression differences between HSCs of G3mTerc−/− mice and mTerc+/+ mice were more pronounced in quiescent HSCs. Three genes (Dusp2, Fyb, and Clasp1), which were not differentially regulated in gene array analysis of HSCs from G3mTerc−/− compared with mTerc+/+ mice, were chosen as negative control (A, right). Values are shown as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). *P < .05. (B-C) The histograms show the percentage of cell nuclei staining positive for the indicated numbers of γH2AX foci in quiescent HSCs (B) and cycling HSCs (C) (100 nuclei were counted per cell type and group) of G3mTerc−/− and mTerc+/+ mice. (D-E) Twelve-month-old G3mTerc−/− mice were treated with interferon-α to stimulate cell cycle activity (supplemental Figure 1A-B). Interferon-α (10 000 U per mouse) or PBS was injected into 12-month-old G3mTerc−/− mice intraperitoneally. Freshly isolated bone marrow cells were analyzed 16 hours after stimulation. (D) Messenger RNA expression of Puma in cycling HSCs (black bars) compared with quiescent HSCs (gray bars). Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 3 for each group). (E) Rate of apoptosis (annexin V–positive cells) in quiescent HSCs and activated HSCs of G3mTerc−/− mice treated with either PBS or interferon-α. Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 3 mice per group). (F) This histogram shows the relative expression of p16 in quiescent HSCs from 12-month-old G3mTerc−/− and age-matched mTerc+/+ mice treated with PBS or interferon-α. Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 3 mice per group). (G) The histogram shows the percentage of cell nuclei staining of γH2AX foci for quiescent HSCs from G3mTerc−/− mice treated with either PBS (gray bar) or interferon-α (black bar) (100 nuclei were counted per group). (H-I) The pie charts depict the composite of clones generated from freshly isolated single HSCs from 12-month-old G3mTerc−/− (332) and age-matched mTerc+/+ (310) mice. Cell numbers were counted on day 6 (H) and day 12 (I) after plating. HSCs were cultured individually in stem cell medium (Stem Cell Technology) with stem cell factor (30 ng/mL) and thrombopoietin (20 ng/mL).

One possible explanation for the results obtained is that DNA damage checkpoints were less active in quiescent HSCs compared with activated HSCs; thus, damaged HSCs were eliminated or arrested at the transition from the quiescent to the activated stage. To test this interpretation, quiescent and activated HSCs were purified by Pyronin Y and Hoechst3334213 from 12-month-old G3mTerc−/− mice that were treated with interferon-α to activate quiescent HSCs to enter the cell cycle.14 Cell cycle analysis showed significant cell cycle entry of HSCs in response to interferon-α treatment (supplemental Figure 1A-B). To monitor the activation of DNA damage checkpoints, the expression levels of p21,7 p16,15 BATF,16 and PUMA17 were analyzed by quantitative polymerase chain reaction in freshly isolated quiescent and activated HSCs. The experiments revealed that Puma was significantly increased in cycling compared with quiescent HSCs of G3mTerc−/− mice (Figure 2D), but there was no difference for p21 and Batf expression (supplemental Figure 1G-H). Several other apoptosis-regulating genes were also upregulated in cycling HSCs compared with quiescent HSCs from G3mTerc−/− mice (supplemental Figure 1C), but not in cycling HSCs from mTerc+/+ stimulated with interferon-α (supplemental Figure 1D), indicating that apoptosis was induced in damaged HSCs of aged G3mTerc−/− mice upon activation. Furthermore, annexin-V staining revealed a significant increase in apoptosis in activated HSCs compared with quiescent HSCs of G3mTerc−/− mice (Figure 2E; supplemental Figure 1E), but not in mTerc+/+ mice (supplemental Figure 1F).

The expression of p16 (a cell cycle inhibitor associated with senescence) was significantly elevated in quiescent HSCs from G3mTerc−/− compared with mTerc+/+ mice, and this increase was even higher in quiescent HSCs from interferon-α stimulated G3mTerc−/− mice (Figure 2F). These data suggested that a subset of quiescent HSCs of telomere dysfunctional mice was arrested in senescence and could not exit quiescence to enter the cell cycle upon stimulation. In agreement with this interpretation, γH2AX staining revealed a significantly elevated amount of DNA damage in HSCs from G3mTerc−/− mice that remained in the G0 gate after interferon-α stimulation compared with G0 HSCs from the control group (Figure 2G). To further test this hypothesis, a number of HSCs (CD34loSca1+c-kit+Lineage−) from 12-month-old G3mTerc−/− (332) and age-matched mTerc+/+ (310) mice were purified and cultured individually. At 6 and 12 days after seeding, the cell numbers of each colony were assessed (Figure 2H-I). On day 6, 7.6% of HSCs from G3mTerc−/− mice died compared with 0.32% of the HSCs from mTerc+/+ mice (Figure 2H, P = .0083). Moreover, the percentage of HSCs that stayed alive as single cells and could not enter the cell cycle to form colonies was higher in HSCs purified from G3mTerc−/− compared with mTerc+/+ mice by day 6 (Figure 2H; 9.2% vs 2.9%, P = .043). Together with the in vivo data, these experiments indicate that both senescence cell cycle arrest and apoptosis represent checkpoint responses that block damaged HSCs from G3mTerc−/− mice from entering the cell cycle upon stimulation and generating committed progenitor cells.

This study reveals that DNA damage and gene expression changes accumulate specifically in quiescent HSCs in the context of telomere shortening. Activation of senescence locks a subset of damaged HSCs in the G0 stage, which is consistent with a recent report showing a similar phenotype in muscle stem cells from geriatric mice.15 Some damaged HSCs from G3mTerc−/− mice entered the cell cycle upon stimulation, which led to apoptosis induction. Taken together, both senescence and apoptosis checkpoints may cooperate to prevent damaged HSCs from generating hematopoietic progenitor cells. A similar mechanism has been disclosed in the intestinal stem cell system.17 In addition to the activation of checkpoints, it is also possible that DNA repair contributes to the decline of DNA damage and gene expression changes at the transition from quiescent HSCs to progenitor cells. Along these lines, a recent study showed that DNA repair signaling is compromised in quiescent HSCs but is activated when HSCs enter the cycle.8 Of note, many of the differentially expressed genes play a role in DNA damage repair and apoptosis, which may be a response and/or contributing factor to the accumulation of DNA damage. It is conceivable that some gene expression changes are induced by chromosomal, genetic, and epigenetic alterations that occur in response to telomere dysfunction.17-19 Together, these findings improve our understanding of the evolution and dynamics of gene expression changes and DNA damage accumulation in aging hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells in the context of telomere dysfunction. The findings may influence the selection of aberrant HSC clones that are characteristic of human aging and leukemia development.20,21

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is an Inside Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Isabell Blochberger for her excellent technical assistance.

This work was supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Ru745-10 and RU-745-12), the European Union (ERC-2012-AdG 323136) (K.L.R.) (ERC-2013-AdG 322602) (C.A.K.), the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (GerontoSys – SyStaR 315894) (K.L.R.), and the German Cancer Aid (108246) (K.L.R. and C.A.K.).

Authorship

Contribution: J.W. performed experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript; X.L. and C.A.K. performed the gene array experiment and analyzed the data; K.L.R. designed research, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript; and V.S. conducted and analyzed mouse experiments.

Conflict-of-interest: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Karl Lenhard Rudolph, Beutenbergstraße 11, 07745 Jena, Germany; e-mail: klrudolph@fli-leibniz.de.