Key Points

We characterize active vs inactive analog compounds suitable for inhibition of both PRC2-EZH2 and PRC2-EZH1 ex vivo and in vivo.

This study is the first to show oral delivery of an EZH2 and EZH1 dual inhibitor as promising therapeutics for MLL-rearranged leukemia.

Abstract

Enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) and related EZH1 control gene expression and promote tumorigenesis via methylating histone H3 at lysine 27 (H3K27). These methyltransferases are ideal therapeutic targets due to their frequent hyperactive mutations and overexpression found in cancer, including hematopoietic malignancies. Here, we characterized a set of small molecules that allow pharmacologic manipulation of EZH2 and EZH1, which include UNC1999, a selective inhibitor of both enzymes, and UNC2400, an inactive analog compound useful for assessment of off-target effect. UNC1999 suppresses global H3K27 trimethylation/dimethylation (H3K27me3/2) and inhibits growth of mixed lineage leukemia (MLL)–rearranged leukemia cells. UNC1999-induced transcriptome alterations overlap those following knockdown of embryonic ectoderm development, a common cofactor of EZH2 and EZH1, demonstrating UNC1999's on-target inhibition. Mechanistically, UNC1999 preferentially affects distal regulatory elements such as enhancers, leading to derepression of polycomb targets including Cdkn2a. Gene derepression correlates with a decrease in H3K27me3 and concurrent gain in H3K27 acetylation. UNC2400 does not induce such effects. Oral administration of UNC1999 prolongs survival of a well-defined murine leukemia model bearing MLL-AF9. Collectively, our study provides the detailed profiling for a set of chemicals to manipulate EZH2 and EZH1 and establishes specific enzymatic inhibition of polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2)–EZH2 and PRC2-EZH1 by small-molecule compounds as a novel therapeutics for MLL-rearranged leukemia.

Introduction

Covalent histone modification provides a fundamental means to control gene expression and define cellular identities.1-3 Dysregulation of histone modification represents a central oncogenic pathway in human cancers.1,3,4 As the regulatory factors involved in the installation, removal, or recognition of histone modification (often termed as epigenetic “writers,” “erasers,” and “readers”1 ) are increasingly considered to be “druggable,”5-7 development of epigenetic modulators holds promise for novel therapeutic interventions.7,8

Polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2), the sole enzymatic machinery that uses either enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) or related EZH1 as a catalytic subunit to induce trimethylation of histone H3 at lysine 27 (H3K27me3), has been shown to play critical roles in gene silencing9 and in hematopoietic lineage specification at various developmental stages.10-13 Extensive evidence has linked PRC2 deregulation to malignant hematopoiesis. Recurrent EZH2 gain-of-function mutations were found in germinal center B-cell lymphoma patients,14,15 and constitutive expression of wild-type or lymphoma-associated mutant EZH2 in hematopoietic lineages induced myeloproliferative diseases16 and lymphomagenesis,13,17 respectively, in murine models. Furthermore, EZH1 compensates the function of EZH29,18 and emerges as regulator of myeloid neoplasms.19,20 Inhibitors selective to EZH2 have recently been developed and shown to be effective in killing lymphoma cells with EZH2 mutation,21-23 however, these inhibitors demonstrated minimal effects on proliferation or gene transcription among lymphomas carrying the wild-type EZH221,22,24 and are expected to be ineffective for tumors that rely on both wild-type EZH2 and EZH1.

Recently, we have discovered a series of small-molecule compounds for specific targeting of both EZH2 and EZH1, including UNC1999, an EZH2 and EZH1 dual inhibitor, and UNC2400, an inactive analog compound useful for assessment of off-target effect.25 Here, we characterized molecular and cellular effects by these translational tools and aim to establish novel therapeutics for cancer types that rely on PRC2-EZH2 and PRC2-EZH1 both. We choose to focus on leukemia bearing chromosomal rearrangement of mixed lineage leukemia (MLL), a gene encoding histone H3 lysine 4 (H3K4)–specific methyltransferase.1,26 MLL rearrangements are responsible for ∼70% of infant acute myeloid or lymphoid leukemia and ∼7% to 10% of adult cases,26 and leukemia with MLL rearrangement displays poor prognosis with low survival rates, highlighting a special need for new interventions.27,28 Oncoproteins produced by MLL rearrangements inappropriately recruit epigenetic factors and/or transcriptional elongation machineries to enforce abnormal gene expression.1,26-28 Recent studies show that PRC2 acts in parallel with MLL rearrangements by controlling a distinctive gene program to sustain leukemogenicity.19,20,29 Specifically, EZH2 and EZH1 compensate one another to promote acute leukemogenesis, and genetic disruption of both enzymes was required to inhibit growth of leukemia carrying MLL-AF9, a common form of MLL rearrangements.19,20 Therefore, chemical agents that can target both PRC2-EZH2 and PRC2-EZH1 shall represent a new way for treating MLL-rearranged leukemia.

In this study, we use a series of proteomics, genomics, and tumorigenic assays to profile the effects of our unique EZH2 and EZH1 dual inhibitor, UNC1999, and its inactive analog, UNC2400, among MLL-rearranged leukemia. UNC1999, and not UNC2400, specifically suppressed H3K27me3/2 and induced a range of anti-leukemia effects including anti-proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis. The UNC1999-responsive gene signatures include Cdkn2a and developmental genes, and significantly overlapped those induced by knockdown of EED, an essential subunit of PRC2-EZH2 and PRC2-EZH1. Mechanistically, we unveiled preferential “erasure” of H3K27me3 associated with distal regulatory elements such as enhancers following UNC1999 treatment, whereas H3K27me3 peaks at proximal promoters are largely retained, despite a shrinking in their average peak size. Gene derepression correlates with decrease in H3K27me3 and concurrent gain in H3K27 acetylation (H3K27ac). None of these effects were seen following UNC2400 treatment, further verifying on-target effect by UNC1999. Cdkn2a is a crucial mediator for UNC1999-induced growth inhibition. Importantly, oral dosing of UNC1999 prolongs survival of MLL-AF9–induced murine leukemia models. Thus, our study provides a detailed characterization of a pair of small-molecule compounds available to the community for studying EZH2 and EZH1 in health and disease. This study also represents the first one to establish chemical inhibition of both EZH2 and EZH1 as a promising therapeutics for MLL-rearranged leukemia.

Methods

Compound synthesis and usage

UNC1999 and UNC2400 were synthesized as previously described.25 Synthesis of UNC1756 and UNC3142 is described in supplemental Materials (available on the Blood Web site). UNC1999 and derivatives were dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) as 5 mM stocks before use.

Mass spectrometry–based quantification

Total histones were prepared and subject to mass spectrometry analysis as previously described.30

Purification, culture, and leukemia transformation of primary hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells

Wild-type Balb/C mice and p16Ink4a−/−;p19Arf−/− knockout mice (strain number 01XB2) were purchased from the NCI at Frederick Mouse Repository. Bone marrow isolated from femur and tibia of mice was subject to lineage-negative enrichment, followed by cytokine stimulation and retroviral transduction of oncogenes (MLL-AF9) as described.31,32 Freshly immortalized leukemia progenitor cell lines were generated, characterized, and maintained with the previously described procedures.31-33 The detailed procedures for flow cytometry, antibody and immunoblot, and various assays of cell proliferation, Wright-Giemsa staining, colony-forming units by serial replating, cell-cycle profiling, and apoptosis are described in supplemental Materials.

Microarray analysis

Total RNA was isolated followed by quantification of the transcript expression levels with Affymetrix GeneChip MOGene_2.1_ST. After RNA hybridization, scanning, and signal quantification (UNC Genomics Core), hybridization signals were retrieved, followed by normalization, differential expression analysis, gene ontology (GO) analysis, gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA), and statistical analysis using GeneSpring Analysis Platform GX12.6 (Agilent Technologies) as described.34 GSEA was also carried out with the downloaded GSEA software (www.broadinstitute.org/gsea) by exploring the Molecular Signatures Database (www.broadinstitute.org/gsea/msigdb/annotate.jsp).

ChIP followed by deep sequencing

Chromatin samples used for chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) followed by deep sequencing (ChIP-Seq) were prepared using a previously described protocol,35 followed by antibody enrichment, library generation, and parallel sequencing using an Illumina HiSeq-2000 Sequencer (UNC High-throughput Sequencing Facility) as described before.36 The detailed procedures of ChIP-Seq data alignment, filtration, peak calling and assignment, and cross-sample comparison and analysis are described in supplemental Materials.

Real-time PCR

The quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) following reverse transcription (RT-qPCR) or ChIP (ChIP-qPCR) was carried out as previously described.34 Information on primers used is described in supplemental Table 6.

In vivo leukemogenic assay and compound treatment

MLL-AF9–induced murine leukemia was generated as previously described,31,32 followed by compound treatment. The powder of UNC1999 (verified by high-performance liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry) was slowly dissolved and incorporated in vehicle (0.5% of sodium carboxymethylcellulose and 0.1% of Tween 80 in sterile water) with continuous trituration by a pestle in a mortar. UNC1999 or vehicle was administered by oral gavage twice daily at a dose of 50 mg/kg. The detailed descriptions of murine leukemia generation, compound usage and delivery, animal care and dissection, and pathological analysis are described in supplemental Materials.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) for 3 independent experiments unless otherwise noted. Statistical analysis was performed with the Student t test, except for nonparametric analysis that used the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test.

Results

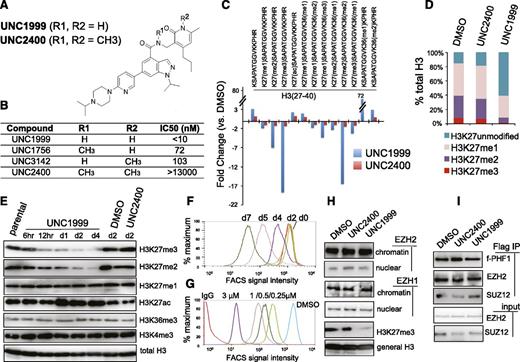

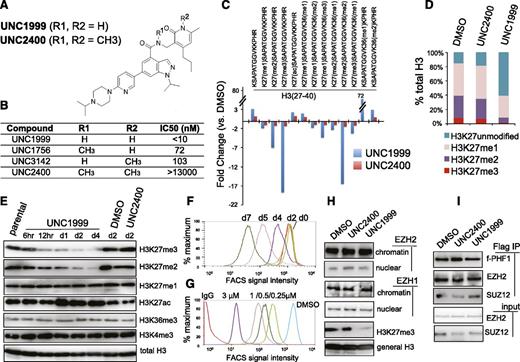

A small-molecule UNC1999, and not its inactive analog UNC2400, selectively and potently suppresses H3K27me3/2

Previously, using an in vitro methyltransferase assay, we have shown that UNC1999 (Figure 1A) exhibits highly selective and potent inhibition of EZH2 and EZH1 over other unrelated methyltransferases with half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) for EZH2 and EZH1 measured at <10 nM (Figure 1B) and 45 nM, respectively.25 UNC2400, an inactive analog compound (with IC50 of >13 000 nM), was generated by modifying UNC1999 with 2 N-methyl groups (Figure 1A-B). Via docking studies with the recently solved apo structure of the EZH2 SET domain,37,38 we found that the 2 N-methyl modifications presumably disrupt the critical hydrogen bonds formed by UNC1999 with the side-chain carbonyl of Asn688 and the N-terminal nitrogen of His689 of EZH2 (supplemental Figure 1A). Modifying UNC1999 with both N-methyl groups is required to abrogate its potency because UNC3142 and UNC1756 (supplemental Figure 1B), 2 compounds with a single N-methyl modification at either position, merely modestly interfered with EZH2-mediated methylation (Figure 1B).

A small-molecule UNC1999, and not its inactive analog UNC2400, selectively and potently suppresses H3K27 methylation. (A) Chemical structure of UNC1999 and UNC2400, with the positions R1 and R2 modified with 2 N-methyl groups (CH3) in UNC2400. (B) Summary of modification at R1 and R2 in UNC1999 and derivatives, and their IC50 measured by in vitro methyltransferase assay. (C) Quantitative mass spectrometry analysis detects the change in relative abundance of various peptide species covering histone H3 amino acids 27-40 after treatment with 3 μM UNC1999 (blue) or UNC2400 (red) for 4 days. Y-axis represents fold-change in relative abundances normalized to DMSO-treated samples; the sequence and modification of H3 peptide are shown on top. (D) Overall percentages of histone H3 with the lysine 27 either unmodified, monomethylated, dimethylated, or trimethylated (H3K27me1/2/3) following compound treatments. (E) Immunoblot of the indicated histone modifications in MLL-AF9–transformed leukemia progenitor cells after treatment with DMSO, or 3 μM UNC1999 or UNC2400. (F-G) Flow cytometry with H3K27me3-specific antibodies revealing time-dependent (F, 2 μM UNC1999) and dose-dependent suppression of H3K27me3 by UNC1999 (G, 7-day treatment) in MLL-AF9–transformed murine leukemia cells and EOL-1 human leukemia cells, respectively. DMSO and nonspecific IgG are used as control. (H) Immunoblots detecting the chromatin-bound and nucleoplasmic fraction of EZH2 or EZH1 after treatment with 2 μM of the indicated compounds for 5 days. (I) Co-IP of PRC2 complex components following Flag IP with extracts of a Flag-PHF1 stable expression cell line34 in the presence of 2 μM of the indicated compounds. ac, acetylation; Co-IP, coimmunoprecipitation; FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorter; Ig, immunoglobulin; IP, immunoprecipitation; me1/2/3, mono/di/trimethylation.

A small-molecule UNC1999, and not its inactive analog UNC2400, selectively and potently suppresses H3K27 methylation. (A) Chemical structure of UNC1999 and UNC2400, with the positions R1 and R2 modified with 2 N-methyl groups (CH3) in UNC2400. (B) Summary of modification at R1 and R2 in UNC1999 and derivatives, and their IC50 measured by in vitro methyltransferase assay. (C) Quantitative mass spectrometry analysis detects the change in relative abundance of various peptide species covering histone H3 amino acids 27-40 after treatment with 3 μM UNC1999 (blue) or UNC2400 (red) for 4 days. Y-axis represents fold-change in relative abundances normalized to DMSO-treated samples; the sequence and modification of H3 peptide are shown on top. (D) Overall percentages of histone H3 with the lysine 27 either unmodified, monomethylated, dimethylated, or trimethylated (H3K27me1/2/3) following compound treatments. (E) Immunoblot of the indicated histone modifications in MLL-AF9–transformed leukemia progenitor cells after treatment with DMSO, or 3 μM UNC1999 or UNC2400. (F-G) Flow cytometry with H3K27me3-specific antibodies revealing time-dependent (F, 2 μM UNC1999) and dose-dependent suppression of H3K27me3 by UNC1999 (G, 7-day treatment) in MLL-AF9–transformed murine leukemia cells and EOL-1 human leukemia cells, respectively. DMSO and nonspecific IgG are used as control. (H) Immunoblots detecting the chromatin-bound and nucleoplasmic fraction of EZH2 or EZH1 after treatment with 2 μM of the indicated compounds for 5 days. (I) Co-IP of PRC2 complex components following Flag IP with extracts of a Flag-PHF1 stable expression cell line34 in the presence of 2 μM of the indicated compounds. ac, acetylation; Co-IP, coimmunoprecipitation; FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorter; Ig, immunoglobulin; IP, immunoprecipitation; me1/2/3, mono/di/trimethylation.

To assess the effect of our active vs inactive compounds on the landscape of histone modifications, we used mass spectrometry proteomic techniques30 to quantify histone modification levels following compound treatment of a murine leukemia line established by MLL-ENL,32 a common form of MLL rearrangements.26,27 Of 55 detected histone peptides carrying the single or combinatorial modification, only peptides covering the H3 residues 27-40 were found altered in relative abundance with fold-change of >2 following UNC1999 vs DMSO treatment (Figure 1C, blue; supplemental Table 1). Peptides with a single H3K27me3 or H3K27me2 modification showed the greatest decreases. H3(27-40) peptide can also be modified by H3K36 methylation and, indeed, following UNC1999 treatment, several peptides with dual methylations of H3K27 and H3K36 were either undetectable (H3K27me3-K36me2) or found decreased (H3K27me3-K36me1 and H3K27me2-K36me2/1) (Figure 1C, blue; supplemental Table 1). Due to H3K27 “demethylation” by UNC1999 on these dually methylated peptides, the relative abundance of certain peptide species bearing H3K36me1/2 (supplemental Figure 1C-D, see increases in blue in bar graph, UNC1999 vs mock) was found increased accordingly (Figure 1C; supplemental Table 1), a phenomenon also seen in cells deficient in Suz12, an essential subunit of PRC2 (supplemental Figure 1E, blue in bar graph).39 Overall, global H3K36me1/2 does not show significant change as examined by mass spectrometry (supplemental Figure 1F) and immunoblot (supplemental Figure 1G); indeed, at the concentrations applied to cells (<3 μM), UNC1999 had no effect on all 4 known H3K36-specific methyltransferases (supplemental Figure 1H-K). These findings collectively demonstrated specific targeting of PRC2 by UNC1999. As a result, the overall percentage of H3K27me3 and H3K27me2 was reduced from 8.5% and 30.9% of total H3 in mock-treated cells, respectively, to 1.3% and 7.1% in UNC1999-treated cells, H3K27me1 slightly altered from 45.6% to 30.7%, whereas the nonmethylated H3K27 increased accordingly from 14.8% to 60.4% (Figure 1D). Consistent with antagonism between PRC2 and H3K27 acetylation (H3K27ac),40 we detected significantly increased H3K27ac after UNC1999 treatment (Figure 1C; supplemental Table 1).

None of these alterations were seen following UNC2400 treatment (Figure 1C, red; supplemental Table 1). By immunoblot (Figure 1E) and flow cytometry (Figure 1F-G; supplemental Figure 1L-N), we verified “erasure” of H3K27me3/2 and concurrent elevation of H3K27ac by UNC1999, its negligible effects on other histone methylations, and undetectable effects by UNC2400. UNC1999-mediated suppression of H3K27me3 was time- and concentration-dependent (Figure 1F-G; supplemental Figure 1L-N). UNC1999 did not alter total levels of PRC2 (supplemental Figure 1O-P) or chromatin-bound EZH2 and EZH1 (Figure 1H), and did not affect the stability or assembly of PRC2 (Figure 1I), indicating that UNC1999 acts primarily via enzymatic inhibition of EZH2 and EZH1 on chromatin.

Taken together, UNC1999 induces potent and selective suppression of H3K27me3/2, whereas UNC2400 does not, highlighting them as a pair of compounds useful to manipulate both PRC2-EZH2 and PRC2-EZH1.

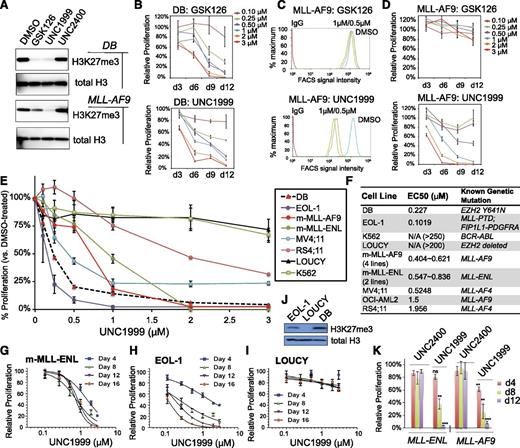

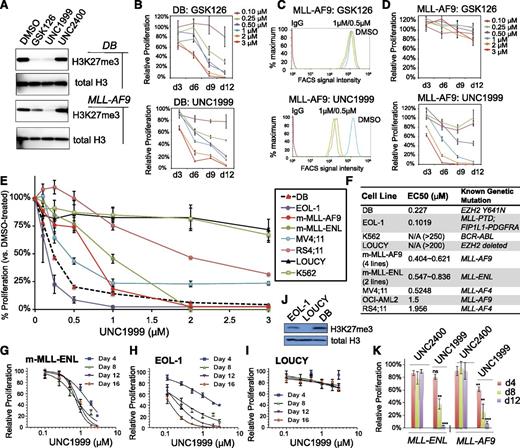

An EZH2 and EZH1 dual inhibitor UNC1999, but not an EZH2-selective inhibitor GSK126, effectively inhibits growth of MLL-rearranged leukemia

Recent studies have shown that genetic disruption of both EZH2 and EZH1 is required to inhibit growth of MLL-rearranged leukemia,19,20 which prompted us to ask whether UNC1999 provides a unique way for treating MLL-rearranged leukemia. First, we compared the effect of UNC1999 to GSK126, a recently disclosed EZH2-selective inhibitor (with ∼150-fold selectivity of EZH2 over EZH1).22 As expected, both GSK126 and UNC1999 efficiently inhibited the global H3K27me3 in DB cells, a lymphoma line bearing the EZH2Y641N mutation,22,25 as measured by both immunoblot (Figure 2A, top) and quantitative flow cytometry (supplemental Figure 2A), and efficiently suppressed DB cell proliferation (Figure 2B). However, using 3 independent MLL-AF9–transformed murine leukemia lines, we found that only UNC1999, and not GSK126, efficiently inhibited their H3K27me3 (Figure 2A, bottom and 2C) and suppressed cell proliferation (Figure 2D; supplemental Figure 2B-E). MLL-AF9–transformed murine leukemia cells coexpress EZH2 and EZH1 (supplemental Figure 2F). These data indicate uniqueness of UNC1999 in treating cancers that rely on PRC2-EZH2 and PRC2-EZH1 both.

UNC1999, but not GSK126, efficiently suppresses H3K27me3 in MLL-rearranged leukemia cells and inhibits their growth. (A) Immunoblots of the global H3K27me3 level after treatment of DB lymphoma cells (top) or MLL-AF9–transformed murine leukemia progenitors (bottom) with 2 μM of the indicated compounds for 5 days. General H3 serves as control. (B) Relative proliferation of DB cells treated with a range of concentrations of GSK126 (top) or UNC1999 (bottom) for the indicated duration. Y-axis represents the relative percentage of accumulative cell numbers normalized to DMSO treatment, and is presented as the mean of triplicates ± SD. (C) Flow cytometry analysis of H3K27me3 in MLL-AF9–transformed murine leukemia progenitors following treatment with various concentrations of GSK126 (top) or UNC1999 (bottom) for 4 days. DMSO serves as control. (D) Relative proliferation of MLL-AF9–transformed leukemia progenitors treated with a range of concentrations of GSK126 (top) or UNC1999 (bottom) for the indicated duration. Y-axis represents the relative percentage of cell numbers after normalization to DMSO treatment, and is presented as the mean of triplicates ± SD. (E) Relative proliferation of a panel of leukemia or lymphoma cell lines treated with various concentrations of UNC1999 for 16 days. Y-axis, presented as the mean of triplicates ± SD, represents the relative percentage of accumulative cell numbers after normalization to DMSO treatment. Shown as a dashed line is DB, an EZH2-mutated (Y641N) lymphoma line known to be sensitive to EZH2 inhibition.22 (F) Summary of EC50 of a panel of cell lines in response to UNC1999. m-MLL-AF9 and m-MLL-ENL represent murine leukemia lines established by MLL-AF9 and MLL-ENL, respectively. (G-I) Relative proliferation of murine MLL-ENL–bearing leukemia cells (G) and EOL-1 (H) and LOUCY (I) human leukemia cells treated with a range of UNC1999 concentrations for the indicated duration. Y-axis represents relative percentage of accumulative cell numbers after normalization to DMSO treatment, and is presented as the mean of triplicates ± SD. (J) Immunoblot of H3K27me3 and general H3 in EOL-1, LOUCY, and DB cells. (K) Relative proliferation of murine leukemia cells bearing MLL-AF9 or MLL-ENL after treatment with UNC1999 or UNC2400 and normalization to DMSO treatment. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001; ns, not significant.

UNC1999, but not GSK126, efficiently suppresses H3K27me3 in MLL-rearranged leukemia cells and inhibits their growth. (A) Immunoblots of the global H3K27me3 level after treatment of DB lymphoma cells (top) or MLL-AF9–transformed murine leukemia progenitors (bottom) with 2 μM of the indicated compounds for 5 days. General H3 serves as control. (B) Relative proliferation of DB cells treated with a range of concentrations of GSK126 (top) or UNC1999 (bottom) for the indicated duration. Y-axis represents the relative percentage of accumulative cell numbers normalized to DMSO treatment, and is presented as the mean of triplicates ± SD. (C) Flow cytometry analysis of H3K27me3 in MLL-AF9–transformed murine leukemia progenitors following treatment with various concentrations of GSK126 (top) or UNC1999 (bottom) for 4 days. DMSO serves as control. (D) Relative proliferation of MLL-AF9–transformed leukemia progenitors treated with a range of concentrations of GSK126 (top) or UNC1999 (bottom) for the indicated duration. Y-axis represents the relative percentage of cell numbers after normalization to DMSO treatment, and is presented as the mean of triplicates ± SD. (E) Relative proliferation of a panel of leukemia or lymphoma cell lines treated with various concentrations of UNC1999 for 16 days. Y-axis, presented as the mean of triplicates ± SD, represents the relative percentage of accumulative cell numbers after normalization to DMSO treatment. Shown as a dashed line is DB, an EZH2-mutated (Y641N) lymphoma line known to be sensitive to EZH2 inhibition.22 (F) Summary of EC50 of a panel of cell lines in response to UNC1999. m-MLL-AF9 and m-MLL-ENL represent murine leukemia lines established by MLL-AF9 and MLL-ENL, respectively. (G-I) Relative proliferation of murine MLL-ENL–bearing leukemia cells (G) and EOL-1 (H) and LOUCY (I) human leukemia cells treated with a range of UNC1999 concentrations for the indicated duration. Y-axis represents relative percentage of accumulative cell numbers after normalization to DMSO treatment, and is presented as the mean of triplicates ± SD. (J) Immunoblot of H3K27me3 and general H3 in EOL-1, LOUCY, and DB cells. (K) Relative proliferation of murine leukemia cells bearing MLL-AF9 or MLL-ENL after treatment with UNC1999 or UNC2400 and normalization to DMSO treatment. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001; ns, not significant.

Next, we applied UNC1999 to a larger panel of leukemia cell lines. All of the 10 lines bearing MLL rearrangements including MLL-AF9, MLL-ENL, MLL-PTD, or MLL-AF4 showed sensitivity to UNC1999 (Figure 2E-H; supplemental Figure 2G-I) with half-maximal effective concentration (EC50) ranging from 102 nM to 1.96 μM (Figure 2F). Notably, multiple MLL-rearranged lines demonstrated a comparable UNC1999 sensitivity to DB (Figure 2E-F). UNC1999 did not induce nonspecific toxicity, for it did not affect proliferation of LOUCY (Figure 2I), a T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia line without detectable H3K27me3 due to EZH2 genomic deletion41 (Figure 2J). Moreover, K562, a BCR-ABL–bearing myeloid leukemia line, also did not respond to UNC1999 (Figure 2E-F). UNC1999-mediated growth suppression was time-dependent and dose-dependent (Figure 2D-H). UNC2400 had no detectable effect on cell growth (Figure 2K).

Collectively, UNC1999, an EZH2 and EZH1 dual inhibitor, efficiently suppresses proliferation of MLL-rearranged leukemia cells that coexpress EZH2 and EZH1.

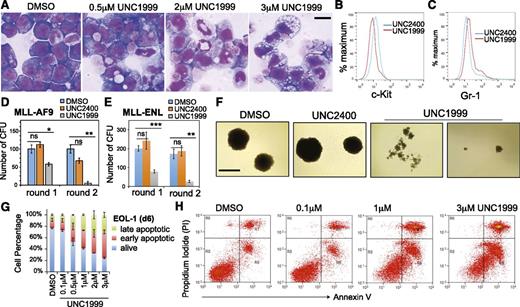

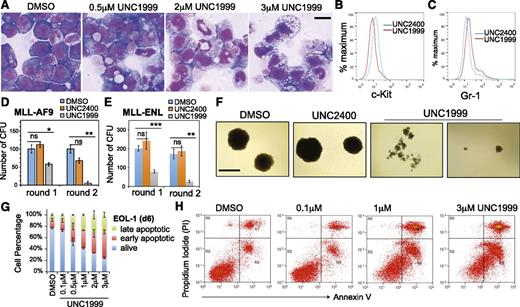

UNC1999, and not UNC2400, suppresses colony-forming abilities of MLL-rearranged leukemia cells and promotes their differentiation and apoptosis

Wright-Giemsa staining revealed dose-dependent alterations by UNC1999 in cell morphology from leukemic myeloblasts to differentiated cells (Figure 3A; supplemental Figure 3A), which was concurrent with the increased differentiation markers and decreased c-Kit, a hematopoietic stem/progenitor marker (Figure 3B-C; supplemental Figure 3B). We used serial replating assays to assess the repopulating ability of clonogenic cells, an ex vivo indicator of leukemia stem cells.42 Following treatment with UNC1999, and not DMSO or UNC2400, MLL-AF9– or MLL-ENL–transformed leukemia cells exhibited a dramatic reduction in the number of outgrowing colonies (Figure 3D-E) and morphologic alterations from the primarily large and compact colonies to the small and diffuse ones characteristic of differentiated cell clusters (Figure 3F). We also examined cell viability and found time- and concentration-dependent induction of apoptosis in several tested lines after treatment with UNC1999, and not UNC2400 (Figure 3G-H; supplemental Figure 3C). Taken together, UNC1999, but not UNC2400, suppresses growth of MLL-rearranged leukemia by inhibiting repopulating ability and promoting cell differentiation and apoptosis.

UNC1999, and not UNC2400, promotes differentiation, suppresses colony formation, and induces apoptosis of MLL-rearranged leukemia cells. (A) Representative light micrographs show Wright-Giemsa staining of MLL-AF9–transformed leukemic progenitors after treatment with the indicated concentration of UNC1999 for 8 days. Black bar, 10 µm. (B-C) Flow cytometry analysis of c-Kit and Gr-1 after treatment with 3 μM of the indicated compounds for 8 days. (D-E) Quantification of colony-forming units from MLL-AF9– (D) or MLL-ENL–transformed leukemia progenitors (E) after serial replating into the cytokine-rich, methylcellulose medium containing DMSO or 3 μM UNC2400 or UNC1999. Data are shown as the mean ± SD of experiments in duplicate. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001. (F) Light micrographs show typical morphology of the single-cell colonies derived from MLL-AF9–transformed leukemia progenitors following serial replating in the presence of DMSO or 3 μM UNC2400 or UNC1999. Black bar, 1 mm. (G) Percentage of live and apoptotic subpopulations of EOL-1 leukemia cells after the indicated compound treatments for 6 days. (H) Typical profiles of staining with PI and annexin V after treatment of EOL-1 cells with DMSO or the indicated concentration of UNC1999 for 6 days. PI, propidium iodide.

UNC1999, and not UNC2400, promotes differentiation, suppresses colony formation, and induces apoptosis of MLL-rearranged leukemia cells. (A) Representative light micrographs show Wright-Giemsa staining of MLL-AF9–transformed leukemic progenitors after treatment with the indicated concentration of UNC1999 for 8 days. Black bar, 10 µm. (B-C) Flow cytometry analysis of c-Kit and Gr-1 after treatment with 3 μM of the indicated compounds for 8 days. (D-E) Quantification of colony-forming units from MLL-AF9– (D) or MLL-ENL–transformed leukemia progenitors (E) after serial replating into the cytokine-rich, methylcellulose medium containing DMSO or 3 μM UNC2400 or UNC1999. Data are shown as the mean ± SD of experiments in duplicate. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001. (F) Light micrographs show typical morphology of the single-cell colonies derived from MLL-AF9–transformed leukemia progenitors following serial replating in the presence of DMSO or 3 μM UNC2400 or UNC1999. Black bar, 1 mm. (G) Percentage of live and apoptotic subpopulations of EOL-1 leukemia cells after the indicated compound treatments for 6 days. (H) Typical profiles of staining with PI and annexin V after treatment of EOL-1 cells with DMSO or the indicated concentration of UNC1999 for 6 days. PI, propidium iodide.

Identification of UNC1999-responsive gene signatures in MLL-rearranged leukemia

To dissect the underlying mechanisms for the UNC1999-induced anti-leukemia effect, we performed microarray analysis with 2 independent MLL-AF9–transformed murine leukemia lines following compound treatments. UNC1999 altered the expression of a few hundred transcripts (Figure 4A-B; supplemental Figure 4A, supplemental Table 2), and consistent with the silencing role of PRC2,43 significantly more genes showed upregulation than downregulation after UNC1999 treatment (Figure 4A-B; supplemental Figure 4A). In contrast, UNC2400 induced little changes (Figure 4A,C; supplemental Table 2), demonstrating its overall inactivity in transcriptional modulation. Importantly, the transcripts upregulated by UNC1999 largely overlapped those after knockdown of EED, a common cofactor of EZH2 and EZH1, demonstrating on-target effects of UNC1999 (Figure 4D; supplemental Figure 4A-C, supplemental Table 2-3). GSEA revealed significant enrichment of PRC2-repressed genes (Figure 4E-G) and those associated with H3K27me3 (supplemental Figure 4D-E) or myeloid differentiation (Figure 4E,H) in UNC1999- vs DMSO-treated cells. GO analysis showed UNC1999-derepressed genes enriched with pathways related to development, myeloid differentiation, and proliferation (supplemental Figure 4F), which are the hallmark of polycomb targets.43 For example, similar to EED knockdown (supplemental Table 3), UNC1999 treatment derepressed the differentiation-associated (Epx), proliferation-associated (Cdkn2a), and development-associated genes (Bcl11a, Ikzf2, Gata1, Tet1, Kdm5b, Smo, Fzd3), whereas expression of all PRC2-encoding genes were unaltered (Figure 4B). By RT-qPCR, we verified the gene expression changes following UNC1999 vs UNC2400 treatments or after EED knockdown (Figure 4I).

UNC1999, and not UNC2400, derepresses the PRC2 gene targets. (A) Summary of the upregulated (blue) and downregulated (red) transcripts in 2 independent MLL-AF9–transformed leukemia lines after a 5-day treatment with 3 μM of compounds or after knockdown of EED vs Renilla, as identified by microarray analysis with a cutoff of FC of >1.5 and a P value of <.01. (B) Scatter plot to compare the global gene expression pattern in MLL-AF9–transformed leukemia cells following DMSO (x-axis) vs UNC1999 treatment (y-axis). Plotted are Log10 values of the signal intensities of all transcripts on gene microarrays after normalization. The flanking lines in green indicate 1.5-fold change in gene expression. (C) Boxplots showing the expression levels of upregulated transcripts in the compound- vs DMSO-treated samples. Y-axis represents the Log10 value of signal intensities detected by microarray. (D) Venn diagram of the upregulated transcripts shown in panel A. (E) Summary of GSEA using the MSIgDB. Green and red indicate the positive and negative correlation to UNC1999-treated cells, respectively. (F-H) GSEA revealing significant enrichment of the EZH2-repressed (F) or EED-repressed gene signatures (G) and those negatively associated with hematopoietic stem cells (H) in the UNC1999- vs DMSO-treated cells. (I) RT-qPCR detects relative expression levels of the indicated genes in MLL-AF9–transformed leukemia cells following treatment with 3 μM of compounds or EED knockdown (shEED) for 5 days. Y-axis represents fold-change after normalization to GAPDH and to control (DMSO treatment or Renilla knockdown [shRen]), and error bars represent SD of triplicates. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001. FC, fold-change; FDR, false discovery rate; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; MSIgDB, Molecular Signatures Database; NES, normalized enrichment score; Ren, Renilla; shEED, shRNA against EED; shREN, shRNA against Renilla.

UNC1999, and not UNC2400, derepresses the PRC2 gene targets. (A) Summary of the upregulated (blue) and downregulated (red) transcripts in 2 independent MLL-AF9–transformed leukemia lines after a 5-day treatment with 3 μM of compounds or after knockdown of EED vs Renilla, as identified by microarray analysis with a cutoff of FC of >1.5 and a P value of <.01. (B) Scatter plot to compare the global gene expression pattern in MLL-AF9–transformed leukemia cells following DMSO (x-axis) vs UNC1999 treatment (y-axis). Plotted are Log10 values of the signal intensities of all transcripts on gene microarrays after normalization. The flanking lines in green indicate 1.5-fold change in gene expression. (C) Boxplots showing the expression levels of upregulated transcripts in the compound- vs DMSO-treated samples. Y-axis represents the Log10 value of signal intensities detected by microarray. (D) Venn diagram of the upregulated transcripts shown in panel A. (E) Summary of GSEA using the MSIgDB. Green and red indicate the positive and negative correlation to UNC1999-treated cells, respectively. (F-H) GSEA revealing significant enrichment of the EZH2-repressed (F) or EED-repressed gene signatures (G) and those negatively associated with hematopoietic stem cells (H) in the UNC1999- vs DMSO-treated cells. (I) RT-qPCR detects relative expression levels of the indicated genes in MLL-AF9–transformed leukemia cells following treatment with 3 μM of compounds or EED knockdown (shEED) for 5 days. Y-axis represents fold-change after normalization to GAPDH and to control (DMSO treatment or Renilla knockdown [shRen]), and error bars represent SD of triplicates. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001. FC, fold-change; FDR, false discovery rate; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; MSIgDB, Molecular Signatures Database; NES, normalized enrichment score; Ren, Renilla; shEED, shRNA against EED; shREN, shRNA against Renilla.

Taken together, treatment of MLL-rearranged leukemias with UNC1999, an EZH2 and EZH1 dual inhibitor, derepresses their PRC2 gene targets.

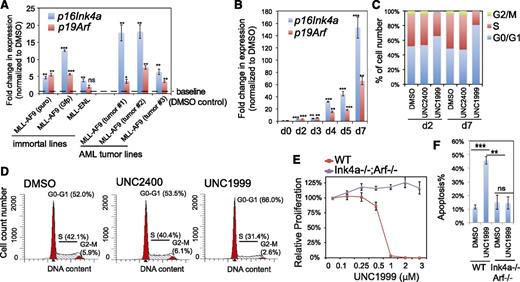

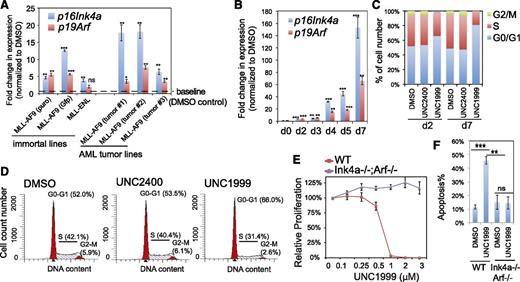

Cdkn2a reactivation is crucial for UNC1999-induced growth suppression

We performed similar gene array analysis either with milder compound treatment or with MLL-ENL–transformed leukemia cells and identified a common UNC1999-responsive signature, which included Cdkn2a (supplemental Table 4). We closely examined Cdkn2a because this polycomb target encodes 2 crucial cell-cycle regulators, p16Ink4a and p19Arf. UNC1999 consistently induced reactivation of p16Ink4a and p19Arf in multiple lines bearing MLL-AF9 or MLL-ENL, and such derepression was concentration- and time-dependent (Figure 5A-B; supplemental Figure 5A). Cdkn2a reactivation was modest after 2-day treatment and dramatic 7 days posttreatment, with >150-fold and >60-fold upregulation of p16Ink4a and p19Arf observed in sensitive lines, respectively (Figure 5A-B). UNC1999 induced cell-cycle arrest at the G1-to-S transition (Figure 5C-D; supplemental Figure 5B). In contrast, UNC2400 did not alter the expression of Cdkn2a (Figure 4C,I) or cell-cycle progression (Figure 5C-D; supplemental Figure 5B). To examine whether UNC1999-induced phenotypes depend on Cdkn2a, we derived several MLL-AF9–transformed leukemia lines with bone marrow from mice deficient in p16Ink4a and p19Arf (supplemental Figure 5C). Compared with their wild-type counterparts, these p16Ink4a−/−/p19Arf−/− leukemia cells no longer responded to UNC1999 with no detectable change in their proliferation (Figure 5E) or apoptosis (Figure 5F) following treatment. Collectively, Cdkn2a is a critical downstream mediator of UNC1999-induced growth inhibition.

Cdkn2a reactivation plays a critical role in UNC1999-mediated growth inhibition. (A) Change in p16Ink4a and p19Arf gene expression following a 3-day treatment with 3 μM UNC1999 among 6 independent murine leukemia lines, either freshly immortalized by MLL-AF9 or MLL-ENL (left) or derived from MLL-AF9–induced primary murine leukemia (right). Y-axis represents fold-change in gene expression after normalization to GAPDH and DMSO treatment, and error bars represent SD of triplicates. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001. (B) RT-qPCR shows time-dependent derepression of p16Ink4a and p19Arf by UNC1999 in a leukemia line derived from MLL-AF9–induced primary tumors. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001. (C) Summary of cell-cycle status of MLL-AF9–transformed murine leukemia progenitors following 2-day or 7-day treatment with DMSO, or 3 μM UNC2400 or UNC1999. (D) Representative histograms showing DNA contents measured by PI staining of MLL-AF9–transformed leukemia cells after treatment with 3 μM of compounds for 2 days. (E) Relative proliferation of MLL-AF9–transformed murine leukemia cells, either wild-type (red) or p16Ink4a−/−/p19Arf−/− (purple), after treatment with various concentrations of UNC1999 for 12 days. Y-axis, presented as the mean of triplicates ± SD, represents the relative percentage of cell numbers after normalization to DMSO treatment. (F) Summary of apoptotic induction in MLL-AF9–transformed murine leukemia progenitors, either wild-type (WT) or p16Ink4a/p19Arf-deficient, following a 6-day treatment with 3 μM of compounds as assayed by PI staining. **P < .01; ***P < .005. WT, wild type.

Cdkn2a reactivation plays a critical role in UNC1999-mediated growth inhibition. (A) Change in p16Ink4a and p19Arf gene expression following a 3-day treatment with 3 μM UNC1999 among 6 independent murine leukemia lines, either freshly immortalized by MLL-AF9 or MLL-ENL (left) or derived from MLL-AF9–induced primary murine leukemia (right). Y-axis represents fold-change in gene expression after normalization to GAPDH and DMSO treatment, and error bars represent SD of triplicates. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001. (B) RT-qPCR shows time-dependent derepression of p16Ink4a and p19Arf by UNC1999 in a leukemia line derived from MLL-AF9–induced primary tumors. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001. (C) Summary of cell-cycle status of MLL-AF9–transformed murine leukemia progenitors following 2-day or 7-day treatment with DMSO, or 3 μM UNC2400 or UNC1999. (D) Representative histograms showing DNA contents measured by PI staining of MLL-AF9–transformed leukemia cells after treatment with 3 μM of compounds for 2 days. (E) Relative proliferation of MLL-AF9–transformed murine leukemia cells, either wild-type (red) or p16Ink4a−/−/p19Arf−/− (purple), after treatment with various concentrations of UNC1999 for 12 days. Y-axis, presented as the mean of triplicates ± SD, represents the relative percentage of cell numbers after normalization to DMSO treatment. (F) Summary of apoptotic induction in MLL-AF9–transformed murine leukemia progenitors, either wild-type (WT) or p16Ink4a/p19Arf-deficient, following a 6-day treatment with 3 μM of compounds as assayed by PI staining. **P < .01; ***P < .005. WT, wild type.

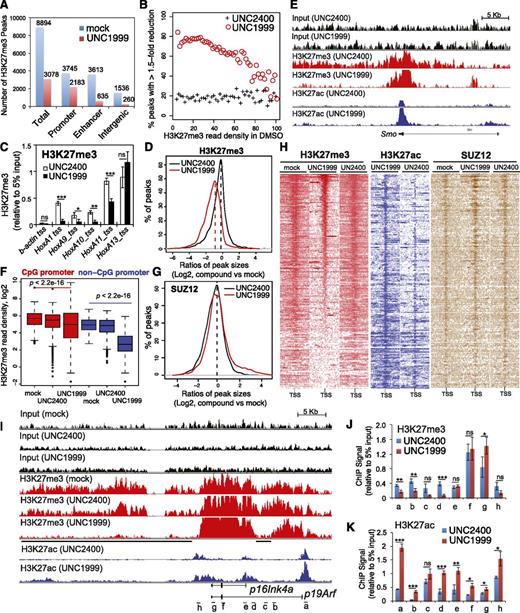

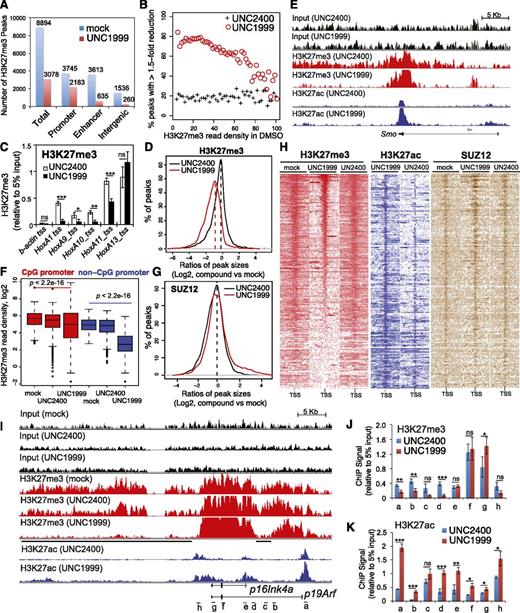

ChIP-Seq reveals UNC1999-induced local suppression of H3K27me3 and concurrent gain of H3K27ac in MLL-rearranged leukemia

To further dissect how UNC1999 alters the chromatin landscape of MLL-AF9–transformed leukemia progenitors, we used ChIP-Seq to profile distribution of H3K27me3 and its antagonizing H3K27ac. We found a global reduction of H3K27me3 following UNC1999 treatment: ∼66% of a total of 8894 H3K27me3 peaks showed complete loss (Figure 6A) whereas 8% showed increases (>1.5-fold, data not shown). ChIP-Seq also unveiled preferential removal of H3K27me3 by UNC1999 at loci containing a relatively lower level of H3K27me3 whereas those harboring the highest H3K27me3 remained generally intact (Figure 6B). For example, UNC1999 completely “erased” a domain with lower H3K27me3 upstream of HoxA1 whereas a domain with higher H3K27me3 covering HoxA11-A13 was unaltered (supplemental Figure 6A red); using ChIP followed by qPCR, we verified such site-specific “demethylation” by UNC1999 at Hox-A genes (Figure 6C). Furthermore, H3K27me3 peaks associated with distal nonpromoter regulatory elements, including enhancers and intergenic regions, often demonstrate complete loss, whereas H3K27me3 peaks associated with proximal promoters are largely retained (Figure 6A; supplemental Figure 6D), despite a shrinking in their average peak size (Figure 6D) or signal reduction at peak shoulders, as exemplified by developmental genes Smo (Figure 6E, red), Evx1, Bcl11a, and Fzd3 (supplemental Figure 6A-C, red). In addition, we found UNC1999 preferentially affected non-CpG promoters compared with CpG promoters (Figure 6F). We also performed ChIP-Seq of SUZ12, an essential cofactor of EZH2 and EZH1, and did not observe significant decreases in SUZ12 binding following compound treatments (Figure 6G; supplemental Figure 6E), which is consistent with our finding that UNC1999 does not affect PRC2 complex stability (Figure 1I). To correlate the transcriptome alteration with ChIP-Seq, we examined UNC1999-derepressed genes. Indeed, following UNC1999 vs mock or UNC2400 treatment, these genes displayed either loss or shrinking of H3K27me3 centered on transcriptional start sites (TSSs) (Figure 6H, red) and concurrent gain in H3K27ac (Figure 6H, blue), whereas the associated SUZ12 was not decreased (Figure 6H, brown). We then closely examined Cdkn2a, a crucial UNC1999-responsive gene. Again, ChIP-Seq revealed preferential “erasure” of H3K27me3 by UNC1999 at multiple regulatory elements (Figure 6I, black lines under the track of “H3K27me3-UNC1999”) of p16Ink4a or p19Arf without altering Cdkn2a-associated SUZ12 (supplemental Figure 6F); TSS-associated H3K27ac was significantly increased (Figure 6I, blue). By ChIP-qPCR, we verified site-specific decreases in H3K27me3 (Figure 6J) and increases in H3K27ac (Figure 6K) across Cdkn2a after UNC1999 vs UNC2400 treatment.

ChIP-Seq reveals UNC1999-induced loss of H3K27me3 and concurrent gain of H3K27ac in MLL-AF9–transformed leukemia progenitors. (A) Summary of H3K27me3 peaks showing loss in the UNC1999- (red) vs mock-treated (blue) samples. X-axis indicates all H3K27me3 peaks (left) or those associated with promoters, enhancers, or intergenic regions. (B) The fractions of H3K27me3 peaks showing reduction in ChIP-Seq signals by 1.5-fold or more in UNC1999-treated (red circle) or UNC2400-treated (cross) samples in comparison with mock treatment. The H3K27me3 peaks and their densities shown on x-axis were first defined and then grouped by the number of ChIP-Seq reads identified in the mock-treated sample; y-axis represents the fraction in each group of H3K27me3 peaks that show reduction by >1.5-fold in the compound- vs mock-treated samples, after normalization of ChIP-Seq reads to the sequencing depths and peak sizes. (C) ChIP-qPCR detects H3K27me3 at the TSS of several Hox-A genes in MLL-AF9–transformed leukemia progenitors after treatment with 3 μM UNC2400 or UNC1999 for 4 days. ChIP signals (y-axis) were normalized to 5% of input and presented as mean ± SD. TSS of β-actin was used as negative control. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001. (D) Plot showing a global reduction in the H3K27me3 peak sizes following UNC1999 treatment (red). X-axis shows the ratios (in their Log2 values) of peak sizes following UNC1999 (red) or UNC2400 (black) treatment in comparison with mock; y-axis shows the relative fraction of peaks at each individual ratio. The dashed vertical lines mark the mean value of peak size ratios. (E) IGB view showing the distribution of input (black), H3K27me3 (red) and H3K27ac (blue) ChIP-Seq read densities (normalized by the ChIP-seq read depths) at the Smoothened (Smo) gene in MLL-AF9 leukemia progenitors after treatment with 3 μM UNC2400 or UNC1999 for 4 days. (F) Boxplots showing a significantly greater reduction of ChIP-Seq enrichment at the non-CpG- than the CpG-contained promoter associated H3K27me3 peaks after UNC1999 treatment in comparison with mock treatment. (G) Plot showing the relative size of SUZ12 peaks after compound treatments. X-axis shows the ratios (in their Log2 values) of peak sizes following UNC1999 (red) or UNC2400 (black) treatment in comparison with mock; y-axis shows the relative fraction of peaks at each individual ratio. The dashed vertical lines mark the mean value of peak size ratios. (H) Heatmap showing the ChIP-Seq read densities of H3K27me3 (red), H3K27ac (blue), and SUZ12 (brown) across the TSS (±20 kb) of upregulated genes following UNC1999 vs mock treatment (Figure 4A). Color represents the degree of ChIP-Seq signal enrichment, with the lowest set to white. The data indicate that a large majority (top of the heatmaps) of the UNC1999-derepressed genes contains H3K27me3 across TSS prior to compound treatment, and following UNC1999 treatment, H3K27me3 peaks become narrower and sharper. (I) IGB profiles showing the distribution of ChIP-Seq read densities (normalized by the ChIP-seq read depths) for input (black), H3K27me3 (red), and H3K27ac (blue) at p16Ink4a and p19Arf. Black bars under the track of H3K27me3 (UNC1999) mark the regulatory regions showing loss or reduction of H3K27me3 after UNC1999 treatment in comparison with mock or UNC2400. (J-K) ChIP-qPCR of H3K27me3 (J) and H3K27ac (K) across the Cdkn2a locus in MLL-AF9–transformed leukemia progenitors after treatment with 3 μM UNC2400 (blue) or UNC1999 (red) for 4 days. The genomic organization of p16Ink4a and p19Arf and positions of each ChIP PCR amplicon (labeled alphabetically, not drawn to scale) are depicted at the bottom of panel I. ChIP signals (y-axis) from independent experiments were normalized to input and presented as mean ± SD. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001. IGB, Integrated Genome Browser.

ChIP-Seq reveals UNC1999-induced loss of H3K27me3 and concurrent gain of H3K27ac in MLL-AF9–transformed leukemia progenitors. (A) Summary of H3K27me3 peaks showing loss in the UNC1999- (red) vs mock-treated (blue) samples. X-axis indicates all H3K27me3 peaks (left) or those associated with promoters, enhancers, or intergenic regions. (B) The fractions of H3K27me3 peaks showing reduction in ChIP-Seq signals by 1.5-fold or more in UNC1999-treated (red circle) or UNC2400-treated (cross) samples in comparison with mock treatment. The H3K27me3 peaks and their densities shown on x-axis were first defined and then grouped by the number of ChIP-Seq reads identified in the mock-treated sample; y-axis represents the fraction in each group of H3K27me3 peaks that show reduction by >1.5-fold in the compound- vs mock-treated samples, after normalization of ChIP-Seq reads to the sequencing depths and peak sizes. (C) ChIP-qPCR detects H3K27me3 at the TSS of several Hox-A genes in MLL-AF9–transformed leukemia progenitors after treatment with 3 μM UNC2400 or UNC1999 for 4 days. ChIP signals (y-axis) were normalized to 5% of input and presented as mean ± SD. TSS of β-actin was used as negative control. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001. (D) Plot showing a global reduction in the H3K27me3 peak sizes following UNC1999 treatment (red). X-axis shows the ratios (in their Log2 values) of peak sizes following UNC1999 (red) or UNC2400 (black) treatment in comparison with mock; y-axis shows the relative fraction of peaks at each individual ratio. The dashed vertical lines mark the mean value of peak size ratios. (E) IGB view showing the distribution of input (black), H3K27me3 (red) and H3K27ac (blue) ChIP-Seq read densities (normalized by the ChIP-seq read depths) at the Smoothened (Smo) gene in MLL-AF9 leukemia progenitors after treatment with 3 μM UNC2400 or UNC1999 for 4 days. (F) Boxplots showing a significantly greater reduction of ChIP-Seq enrichment at the non-CpG- than the CpG-contained promoter associated H3K27me3 peaks after UNC1999 treatment in comparison with mock treatment. (G) Plot showing the relative size of SUZ12 peaks after compound treatments. X-axis shows the ratios (in their Log2 values) of peak sizes following UNC1999 (red) or UNC2400 (black) treatment in comparison with mock; y-axis shows the relative fraction of peaks at each individual ratio. The dashed vertical lines mark the mean value of peak size ratios. (H) Heatmap showing the ChIP-Seq read densities of H3K27me3 (red), H3K27ac (blue), and SUZ12 (brown) across the TSS (±20 kb) of upregulated genes following UNC1999 vs mock treatment (Figure 4A). Color represents the degree of ChIP-Seq signal enrichment, with the lowest set to white. The data indicate that a large majority (top of the heatmaps) of the UNC1999-derepressed genes contains H3K27me3 across TSS prior to compound treatment, and following UNC1999 treatment, H3K27me3 peaks become narrower and sharper. (I) IGB profiles showing the distribution of ChIP-Seq read densities (normalized by the ChIP-seq read depths) for input (black), H3K27me3 (red), and H3K27ac (blue) at p16Ink4a and p19Arf. Black bars under the track of H3K27me3 (UNC1999) mark the regulatory regions showing loss or reduction of H3K27me3 after UNC1999 treatment in comparison with mock or UNC2400. (J-K) ChIP-qPCR of H3K27me3 (J) and H3K27ac (K) across the Cdkn2a locus in MLL-AF9–transformed leukemia progenitors after treatment with 3 μM UNC2400 (blue) or UNC1999 (red) for 4 days. The genomic organization of p16Ink4a and p19Arf and positions of each ChIP PCR amplicon (labeled alphabetically, not drawn to scale) are depicted at the bottom of panel I. ChIP signals (y-axis) from independent experiments were normalized to input and presented as mean ± SD. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001. IGB, Integrated Genome Browser.

Collectively, UNC1999, but not UNC2400, preferentially “erases” H3K27me3 associated with distal regulatory regions such as enhancers and reshapes the landscape of H3K27me3 vs H3K27ac at proximal promoters in MLL-AF9–transformed leukemia cells, leading to gene derepression.

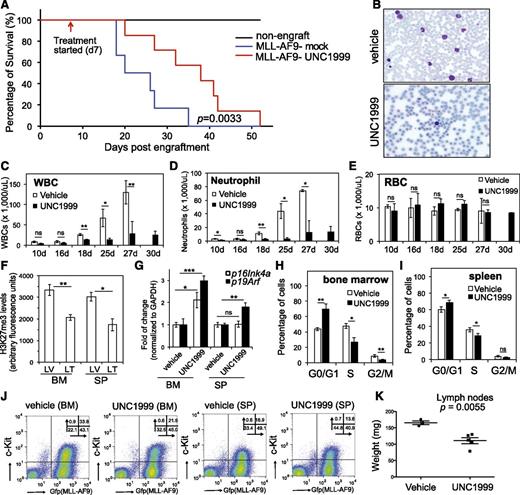

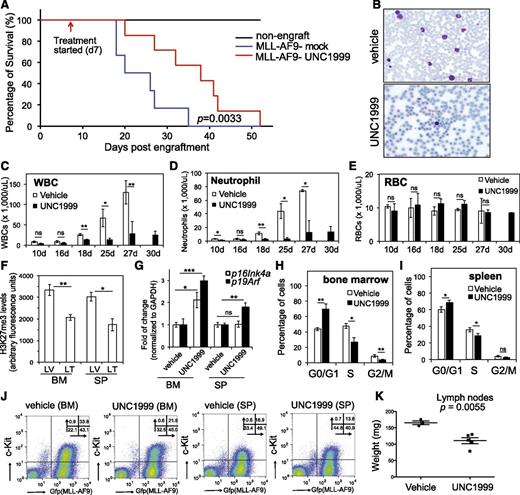

UNC1999 prolongs survival of an MLL-AF9–induced murine leukemia model in vivo

We generated murine leukemia with MLL-AF9 followed by bone marrow transplantation of primary tumors to syngeneic recipients, which developed aggressive leukemia with a consistent latency of 20 to 35 days (Figure 7A, blue). To examine the effect of UNC1999 on in vivo leukemogenesis, we administered either vehicle or 50 mg/kg UNC1999 by oral gavage to mice twice per day and starting from 7 days posttransplantation when the white blood cell (WBC) counts in peripheral blood started to accumulate when compared with nonengrafted controls. We then monitored leukemia progression by periodic assessment of peripheral blood samples and found that, despite steady accumulation of WBCs in both vehicle- and UNC1999-treated cohorts, UNC1999-treated animals displayed significant reduction in WBC counts (Figure 7B-D), indicating a delayed leukemic progression. Indeed, UNC1999-treated leukemic mice exhibited a significantly prolonged survival, with a latency of 36.6 ± 11.7 days in contrast to 24 ± 6.7 days for vehicle-treated mice (Figure 7A, P = .0033). UNC1999 treatment did not affect the counts of red blood cells (Figure 7E) or platelets (supplemental Figure 7A). We closely examined leukemia cells collected from moribund mice. Compared with vehicle, UNC1999 treatment significantly decreased H3K27me3 in cells isolated from bone marrow and spleen (Figure 7F), significantly elevated their p16Ink4a or p19Arf expression (Figure 7G), and caused the G1-to-S cell-cycle arrest (Figure 7H-I; supplemental Figure 7B). UNC1999 treatment also significantly reduced the total number of leukemia cells (labeled by bicistronic GFP expression) or c-Kit–positive leukemia progenitors (c-Kit+/GFP+) in bone marrow and spleen (Figure 7J; supplemental Figure 7C-D). Furthermore, the size of lymph nodes was significantly smaller in UNC1999- vs vehicle-treated mice (Figure 7K); both cohorts showed similar severity of splenomegaly.

UNC1999 prolongs survival of MLL-AF9–induced murine leukemia models in vivo. (A) Kaplan-Meier curve showing leukemia kinetics after transplantation of MLL-AF9–induced primary murine leukemia into syngeneic mice. Starting from day 7 posttransplantation, mice received oral administration of either vehicle (blue) or 50 mg/kg UNC1999 (red) twice per day. Black lines (top) represent nontransplanted normal mice treated with vehicle or UNC1999. Cohort size, 6 to 7 mice. (B) Typical Wright-Giemsa staining images of the peripheral blood smears prepared from the vehicle- (top) and UNC1999-treated (bottom) leukemia mice 25 days posttransplantation. (C-E) Summary of counts of the WBCs (C), neutrophils (D), and RBCs (E) in the peripheral blood of vehicle- (white) or UNC1999-treated (black) leukemia mice at the indicated date posttransplantation. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001. (F) Summary of H3K27me3 levels in cells isolated from bone marrow or spleen of vehicle- (LV) and UNC1999-treated (LT) leukemia mice as quantified by flow cytometry. *P < .05; **P < .01. (G) Fold-change in p16Ink4a and p19Arf gene expression in cells isolated from bone marrow or spleen of the UNC1999-treated (black) leukemia mice in comparison with vehicle-treated (white). *P < .05; **P < .01. (H-I) Summary of cell-cycle status of cells isolated from bone marrow (H) or spleen (I) of vehicle- (white) and UNC1999-treated (black) leukemia mice 25 days posttransplantation. *P < .05; **P < .01. (J) Flow cytometry (performed 25 days posttransplantation) detects leukemia cells (labeled by bicistronic GFP expression in x-axis) and their c-Kit expression (y-axis) in the bone marrow or spleen after treating mice with either vehicle or 50 mg/kg UNC1999. (K) Comparison of sizes of lymph nodes isolated from the MLL-AF9–induced leukemia mice after treatment with either vehicle or 50 mg/kg UNC1999. BM, bone marrow; GFP, green fluorescent protein; LT, UNC1999-treated leukemia mice; LV, vehicle-treated leukemia mice; RBC, red blood cell; SP, spleen.

UNC1999 prolongs survival of MLL-AF9–induced murine leukemia models in vivo. (A) Kaplan-Meier curve showing leukemia kinetics after transplantation of MLL-AF9–induced primary murine leukemia into syngeneic mice. Starting from day 7 posttransplantation, mice received oral administration of either vehicle (blue) or 50 mg/kg UNC1999 (red) twice per day. Black lines (top) represent nontransplanted normal mice treated with vehicle or UNC1999. Cohort size, 6 to 7 mice. (B) Typical Wright-Giemsa staining images of the peripheral blood smears prepared from the vehicle- (top) and UNC1999-treated (bottom) leukemia mice 25 days posttransplantation. (C-E) Summary of counts of the WBCs (C), neutrophils (D), and RBCs (E) in the peripheral blood of vehicle- (white) or UNC1999-treated (black) leukemia mice at the indicated date posttransplantation. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001. (F) Summary of H3K27me3 levels in cells isolated from bone marrow or spleen of vehicle- (LV) and UNC1999-treated (LT) leukemia mice as quantified by flow cytometry. *P < .05; **P < .01. (G) Fold-change in p16Ink4a and p19Arf gene expression in cells isolated from bone marrow or spleen of the UNC1999-treated (black) leukemia mice in comparison with vehicle-treated (white). *P < .05; **P < .01. (H-I) Summary of cell-cycle status of cells isolated from bone marrow (H) or spleen (I) of vehicle- (white) and UNC1999-treated (black) leukemia mice 25 days posttransplantation. *P < .05; **P < .01. (J) Flow cytometry (performed 25 days posttransplantation) detects leukemia cells (labeled by bicistronic GFP expression in x-axis) and their c-Kit expression (y-axis) in the bone marrow or spleen after treating mice with either vehicle or 50 mg/kg UNC1999. (K) Comparison of sizes of lymph nodes isolated from the MLL-AF9–induced leukemia mice after treatment with either vehicle or 50 mg/kg UNC1999. BM, bone marrow; GFP, green fluorescent protein; LT, UNC1999-treated leukemia mice; LV, vehicle-treated leukemia mice; RBC, red blood cell; SP, spleen.

Collectively, oral administration of UNC1999 delays MLL-AF9–induced leukemogenicity in vivo and our EZH2 and EZH1 dual inhibitor provides a new therapeutics for MLL-rearranged leukemia.

Discussion

Our study represents the first to show specific enzymatic inhibition of EZH2 and EZH1 by oral delivery of a small-molecule compound as a promising therapeutic intervention for MLL-rearranged leukemia, a genetically defined malignancy with poor prognosis. Previously, several methods were reported to disrupt PRC2 function in cancer. 3-Deazaneplanocin A (DZNep), an inhibitor of S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase that depletes PRC2 via an unclear mechanism,44 demonstrated a tumor-suppressive effect in cancers including MLL-rearranged leukemia45 ; however, increasing evidence has indicated that DZNep lacks specificity.46,47 Inhibitors highly selective to EZH221-23 or to EZH2 and EZH125,48 have been discovered, some of which demonstrated early success in treating EZH2-mutated lymphoma22 and SNF5-inactivated malignant rhabdoid tumors.49 Furthermore, a hydrocarbon-stapled peptide (SAH-EZH2) has recently been developed to disrupt interaction of EED with EZH2 and EZH1, leading to degradation of PRC2.50 Prior to our study, an orally bioavailable inhibitor of PRC2 remains to be established in both in vitro and in vivo settings to treat cancer that relies on PRC2-EZH2 and PRC2-EZH1 both. Here, we used a series of proteomics, genomics, and leukemogenic approaches to show that UNC1999, an EZH2 and EZH1 dual inhibitor, suppresses growth of MLL-rearranged leukemia ex vivo and in vivo, whereas an EZH2-selective inhibitor GSK126 failed to efficiently inhibit H3K27me3 or proliferation of MLL-rearranged leukemia cells. Our translational tool may represent novel therapeutics for cancer types that coexpress EZH2 and EZH1.

UNC1999-responsive genes largely overlapped the defined PRC2 targets. Derepression of PRC2 target genes associates with suppression of H3K27me3 and concurrent gain in H3K27ac. Unlike DZNep44 or SAH-EZH2,50 UNC1999 does not degrade PRC2 and, thus, the UNC1999-derepressed genes are likely to be silenced by PRC2 via its methyltransferase activity per se, and not via silencing factors recruited by PRC2. This difference may partly explain why a subset of genes were upregulated by EED knockdown and not by UNC1999 (Figure 4D). We also show that deletion of Cdkn2a largely reversed the UNC1999-induced antiproliferation effect in vitro, suggesting that the status of CDKN2A might be a useful predictor for drug resistance vs efficacy of PRC2 inhibitors. It would be also interesting to investigate into the status of CDKN2A among certain non-MLL-rearranged myeloid malignancies and T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia where PRC2 inactivation occurs due to the damaging mutation of EZH2, EED, or SUZ12.51,52 Furthermore, we demonstrated overall inactivity of an analog compound UNC2400 in modulation of H3K27me3 or gene expression, making it an ideal chemical control for UNC1999. Thus, this study provides the first detailed molecular characterization of a pair of active vs inactive small-molecule compounds suitable for studying EZH2 and EZH1 in the in vitro and in vivo settings.

Mechanistically, UNC1999 preferentially “erases” H3K27me3 peaks associated with distal regulatory elements such as enhancers and remodels the landscape of H3K27me3 vs H3K27ac at proximal promoters and TSSs. We speculate that the local concentration and/or composition of PRC2 and associated factors may influence the efficacy of UNC1999, as we observed a higher level of SUZ12 at TSS where H3K27me3 tends to be retained following UNC1999 treatment (Figure 6H). However, the causal relationship remains to be defined. Furthermore, we noticed that UNC1999 had a weaker effect in vivo and only modestly delayed MLL-AF9–induced leukemogenesis. Partial in vivo efficacy has previously been seen for specific inhibitors of BRD453,54 and DOT1L.55 Further optimization of potency, selectivity, and drug metabolism and pharmacokinetics are needed to enhance their in vivo antitumor effect. With accumulating evidence demonstrating a general “druggability” of many cancer-associated epigenetic “writers,” “erasers,” and “readers,”1 development of epigenetic modulators shall provide novel therapeutic interventions in the near future.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs Chris Vakoc, Robert Slany, and Vittorio Sartorelli for providing plasmids used in this study. The authors thank Mike Vernon and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC) Genomics Core for microarray analysis, Charlene Satos and the UNC Animal Studies Core for in vivo studies, and Piotr Mieczkowski and the UNC High-Throughput Sequencing Facility (HTSF) Core for deep-sequencing studies.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Cancer Institute K99/R00 “Pathway to Independence” Award CA151683 (G.G.W.), an NIH Institute of General Medical Sciences grant R01GM103893 (J.J.), a US Department of Defense Congressionally Directed Medical Research Programs grant CA130247 (G.G.W.), and the University Cancer Research Fund of North Carolina State. The Structural Genomics Consortium is a registered charity (no. 1097737) that receives funds from the Canada Foundation for Innovation, Eli Lilly Canada, GlaxoSmithKline, the Ontario Ministry of Economic Development and Innovation, the Novartis Research Foundation, Pfizer, AbbVie, Takeda, Janssen, Boehringer Ingelheim, and the Wellcome Trust. G.G.W. is an American Society of Hematology Scholar in Basic Science, a Kimmel Scholar of the Sidney Kimmel Foundation for Cancer Research, and is also supported by grants from the Gabrielle’s Angel Foundation and the Concern Foundation of Cancer Research. D.F.A. and L.C. are supported by postdoctoral fellowships from the American Association for Cancer Research–Debbie’s Dream Foundation and Department of Defense, respectively, and K.D.K. is supported by a predoctoral fellowship from the American Chemical Society Medicinal Chemistry Division.

Authorship

Contribution: G.G.W. and J.J. designed the research; B.X., D.M.O., A.M., T.P., K.D.K., S.G.P., D.F.A., L.C., S.L., D.F.A., F.L., S.V.F., M.V., B.A.G., J.J., and G.G.W. performed the research; S.R., Y.L., G.G.W., and D.Z. analyzed ChIP-Seq data; B.X., D.M.O., and G.G.W. performed overall analysis and data interpretation; G.G.W. wrote the paper; and all authors checked the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Greg G. Wang, Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics, UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 450 West Dr, CB 7295, Chapel Hill, NC 27599; e-mail: greg_wang@med.unc.edu.

References

Author notes

B.X., D.M.O., and A.M. contributed equally to this study.

![Figure 4. UNC1999, and not UNC2400, derepresses the PRC2 gene targets. (A) Summary of the upregulated (blue) and downregulated (red) transcripts in 2 independent MLL-AF9–transformed leukemia lines after a 5-day treatment with 3 μM of compounds or after knockdown of EED vs Renilla, as identified by microarray analysis with a cutoff of FC of >1.5 and a P value of <.01. (B) Scatter plot to compare the global gene expression pattern in MLL-AF9–transformed leukemia cells following DMSO (x-axis) vs UNC1999 treatment (y-axis). Plotted are Log10 values of the signal intensities of all transcripts on gene microarrays after normalization. The flanking lines in green indicate 1.5-fold change in gene expression. (C) Boxplots showing the expression levels of upregulated transcripts in the compound- vs DMSO-treated samples. Y-axis represents the Log10 value of signal intensities detected by microarray. (D) Venn diagram of the upregulated transcripts shown in panel A. (E) Summary of GSEA using the MSIgDB. Green and red indicate the positive and negative correlation to UNC1999-treated cells, respectively. (F-H) GSEA revealing significant enrichment of the EZH2-repressed (F) or EED-repressed gene signatures (G) and those negatively associated with hematopoietic stem cells (H) in the UNC1999- vs DMSO-treated cells. (I) RT-qPCR detects relative expression levels of the indicated genes in MLL-AF9–transformed leukemia cells following treatment with 3 μM of compounds or EED knockdown (shEED) for 5 days. Y-axis represents fold-change after normalization to GAPDH and to control (DMSO treatment or Renilla knockdown [shRen]), and error bars represent SD of triplicates. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001. FC, fold-change; FDR, false discovery rate; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; MSIgDB, Molecular Signatures Database; NES, normalized enrichment score; Ren, Renilla; shEED, shRNA against EED; shREN, shRNA against Renilla.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/125/2/10.1182_blood-2014-06-581082/4/m_346f4.jpeg?Expires=1770358154&Signature=INpCYjCOEy966Duc1sly0oGmh16MbZD56CbX3iWRoMY6JyNfF8Vu9i5yU4b6nJSBkAuipn7QEFfrDUkERL2WSWuVADW8cf1otnJQj32MNVz4hgVJKij1UWLPkY2j-BzJX3f3u9K7jb0BZaNA0-NJKo~RX4KfIg6UM8YGrx1DXVtl6ix2Er7ScguJHbYByenNQyzs80dAgIk0mBDdd6hEPg0H5uJDTxaxrT7YfrYdKspXM6RInQ9pra4jY6DYttjF0z4qV23AlMUK3JpNIQVRevMRpz8709cWwsmK~5p0ZWtIGro0ApzFGDZN6GB1VZwjgmitCh3NpbLHzRg0s4NH1w__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 4. UNC1999, and not UNC2400, derepresses the PRC2 gene targets. (A) Summary of the upregulated (blue) and downregulated (red) transcripts in 2 independent MLL-AF9–transformed leukemia lines after a 5-day treatment with 3 μM of compounds or after knockdown of EED vs Renilla, as identified by microarray analysis with a cutoff of FC of >1.5 and a P value of <.01. (B) Scatter plot to compare the global gene expression pattern in MLL-AF9–transformed leukemia cells following DMSO (x-axis) vs UNC1999 treatment (y-axis). Plotted are Log10 values of the signal intensities of all transcripts on gene microarrays after normalization. The flanking lines in green indicate 1.5-fold change in gene expression. (C) Boxplots showing the expression levels of upregulated transcripts in the compound- vs DMSO-treated samples. Y-axis represents the Log10 value of signal intensities detected by microarray. (D) Venn diagram of the upregulated transcripts shown in panel A. (E) Summary of GSEA using the MSIgDB. Green and red indicate the positive and negative correlation to UNC1999-treated cells, respectively. (F-H) GSEA revealing significant enrichment of the EZH2-repressed (F) or EED-repressed gene signatures (G) and those negatively associated with hematopoietic stem cells (H) in the UNC1999- vs DMSO-treated cells. (I) RT-qPCR detects relative expression levels of the indicated genes in MLL-AF9–transformed leukemia cells following treatment with 3 μM of compounds or EED knockdown (shEED) for 5 days. Y-axis represents fold-change after normalization to GAPDH and to control (DMSO treatment or Renilla knockdown [shRen]), and error bars represent SD of triplicates. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001. FC, fold-change; FDR, false discovery rate; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; MSIgDB, Molecular Signatures Database; NES, normalized enrichment score; Ren, Renilla; shEED, shRNA against EED; shREN, shRNA against Renilla.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/125/2/10.1182_blood-2014-06-581082/4/m_346f4.jpeg?Expires=1770358155&Signature=fB7hm8rbRjNJQnDgiSV5dYXlU1hLuNtykEyzpoEZs701Q6VbxEWnKU65GC22bHIttyG~YDXuOxSgYo5YVZJ1qq~xn9sDbcZmVVlBFuAX~oD0PEinRBb2RuLm5B7TLu0rjvwXmfauHfMl4x2MgOBWRlBOn8zUi5UcrMUTw6IFisaCTLmaXcltQDk3duEkJjEK-OQQnfQC35O3ghDyxnF5KksxS7prADLhNxd7R8H4WbvxzPEMNb99WhVSpSMJPsJYhzSxh~ZV6uBwcvcYHrlJW0WJHDA4bXRx9lD9NUbefMYLsq1TcEWW5A7rmBJt890l51joSxNrZQAkEiaA28qjYg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)