TO THE EDITOR:

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a complicated disease characterized by the uncontrolled proliferation of hematopoietic precursors and the loss of differentiation ability caused by various genetic alterations. Recent advances in massively parallel sequencing technologies have identified several gene mutations associated with the pathogenesis of AML, including mutations in NPM1, DNMT3A, IDH1/2, and TET2.1-6 However, the rarity of some of mutations, such as DNMT3A, IDH1/2, and TET2, in pediatric AML7,8 necessitates exploring additional biomarkers to stratify pediatric patients with AML. Remarkably, the 2017 European LeukemiaNet recommendations incorporated RUNX1 mutations to the group of markers, suggesting adverse risks in adult AML.9 However, the low frequency of RUNX1 mutations renders the prognosis of pediatric patients with AML uncertain.10-12 Thus, this study aims to investigate RUNX1 mutations and their correlation with other gene aberrations to elucidate the prognostic impact in 503 pediatric patients with de novo AML.

In this retrospective cohort study, we recruited patients with de novo AML (age, <18 years) who participated in either the AML99 clinical trial of the Japanese Childhood AML Cooperative Study (January 2000 to December 2002) or the AML-05 clinical trial of the Japanese Pediatric Leukemia/Lymphoma Study Group (November 2006 to December 2010).13,14 Overall, we enrolled 503 patients with available leukemic samples in this study comprising 134 of 280 from the AML99 trial and 369 of 485 from the AML-05 trial (supplemental Table 1, available on the Blood Web site). We observed no significant differences in the overall survival (OS) between the available and unavailable samples in the AML99 or AML-05 trial (supplemental Tables 2 and 3). Patients with Down syndrome and acute promyelocytic leukemia were excluded. Details of these protocols are available elsewhere.13-15 This study was approved by the institutional review board of Gunma Children’s Medical Center and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki guidelines.

We extracted genomic DNA from leukemic samples using the ALLPrep DNA/RNA Mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). In addition, targeted deep sequencing of RUNX1 was performed in 503 pediatric patients with de novo AML using the next-generation sequencing (details of the study methodology, additional molecular and cytogenetic analyses, and statistical analyses are described in supplemental Methods).

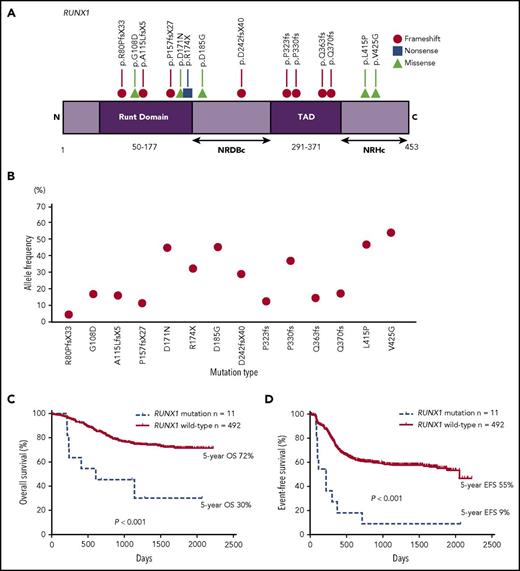

We identified RUNX1 mutations in 2.8% (14 of 503) of pediatric patients with de novo AML, 64% (9 of 14) of whom had frameshift/nonsense mutations, and 36% (5 of 14) of whom had heterozygous point mutations that resulted in translational changes (Figure 1A). Figure 1B shows variant allele frequencies (VAFs) of RUNX1 mutations. Notably, none of the 14 patients with RUNX1 mutations had thrombocytopenia, history of myelodysplastic syndrome, or family history of AML. Based on previous studies and The Cancer Genome Atlas database (TCGA), 3 point mutations (G108D, D171N, and R174X) in the Runt domain were confirmed as somatic mutations.16-18 Among 3 missense mutations (D185G, L415P, and V425G) that were not confirmed to be somatic, we detected 2 types (D185G and V425G) both at diagnosis and complete remission (CR). Despite not being able to assess the remaining 1 type (L415P) owing to a lack of samples at CR, it was anticipated as a germ line mutation because VAF was nearly 50% (46.6%).19 In addition, these 3 mutations were located in the C-terminal negative regulatory region for DNA binding (NRDBc) or the C-terminal negative regulatory region for heterodimerization (NRHc; Figure 1A).20 Although roles of these domains remain unclear, a study reported that missense mutations in the C-terminal region, including NRDBc and NRHc, are uncommon in pedigrees with familial platelet disorder/AML.21 As these 3 patients with RUNX1 mutations reported no episode suggestive of familial platelet disorder/AML, we excluded these 3 mutations from this study. Thus, we finally analyzed only 11 patients with RUNX1 mutations. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the study cohort.

A gene diagram and prognostic impact in pediatric AML patients with RUNX1 mutations. (A) A gene diagram depicting RUNX1 mutations in pediatric patients with AML (NCBI reference sequence; NM_001001890). (B) A VAF of 14 RUNX1 mutations. (C) A comparison of the OS and (D) EFS between patients with and without RUNX1 mutations. NRDBc, the C-terminal negative regulatory region for DNA binding; NRHc, the C-terminal negative regulatory region for heterodimerization; TAD, transcription activation domain.

A gene diagram and prognostic impact in pediatric AML patients with RUNX1 mutations. (A) A gene diagram depicting RUNX1 mutations in pediatric patients with AML (NCBI reference sequence; NM_001001890). (B) A VAF of 14 RUNX1 mutations. (C) A comparison of the OS and (D) EFS between patients with and without RUNX1 mutations. NRDBc, the C-terminal negative regulatory region for DNA binding; NRHc, the C-terminal negative regulatory region for heterodimerization; TAD, transcription activation domain.

In this study, we compared the clinical and molecular characteristics between patients with and without RUNX1 mutations (supplemental Table 4). No significant differences were observed in age, sex, and white blood cell counts at diagnosis between both groups. In addition, RUNX1 mutations were associated with the French-American-British M0 morphology (P = .026), which corroborates previous pediatric10,12 and adult17,22-25 studies. Although 6 of 11 RUNX1 mutations (55%) were determined in patients with a normal karyotype (P = .012), the remaining 5 mutations were detected in 2 patients with RUNX1-RUNX1T1 and 1 each with monosomy 7, trisomy 8, and complex karyotype (Table 1). Although exclusive correlations between RUNX1-RUNX1T1 and RUNX1 mutations have been reported,22 we observed similar RUNX1 mutations in patients with RUNX1-RUNX1T1 to those described in latest studies using next-generation sequencing in adult AML.17,25 Furthermore, RUNX1 mutations were associated with KMT2A–partial tandem duplication (P < .001) and were mutually exclusive with NPM1 and CEBPA mutations; these genetic features of patients with RUNX1 mutations are consistent with those previously described in adult AML cases.17,22-25

Remarkably, RUNX1 mutations exhibited a high prevalence of non-CR (6 of 11, 55% vs 49 of 492, 10%; P < .001). Seven of 11 patients with RUNX1 mutations died, and 3 of 4 survivors required stem cell transplantation (SCT). Remarkably, the OS and event-free survival (EFS) were significantly poorer in patients with RUNX1 mutations than in those without RUNX1 mutations (5-year OS, 30% vs 72%, P < .001; 5-year EFS, 9% vs 55%, P < .001; Figure 1C-D). Based on the location of mutations, we observed no difference in outcomes in this study, which is consistent with previous adult AML studies.23,24 We used Cox regression models for univariate and multivariate analyses (supplemental Table 5). Besides RUNX1 mutations, we used FLT3-ITD and some cytogenetic groups, such as t(8;21)(q22;q22)/RUNX1-RUNX1T1, inv(16)(p13q22)/CBFB-MYH11, 5q deletion, monosomy 7, and t(16;21)(p11;q22)/FUS-ERG, as expounding variables in the multivariate analysis; these cytogenetic aberrations were used for risk classification in the AML99 and AML-05 trials.13,14 In addition, RUNX1 mutations were significantly associated with inferior OS (univariate [hazard ratio (HR), 4.020; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.873-8.625; P < .001]; multivariate [HR, 2.572; 95% CI, 1.185-5.582; P = .017]) and EFS (univariate [HR, 4.351; 95% CI, 2.292-8.259; P < .001]; multivariate [HR, 3.678; 95% CI, 1.924-7.030; P < .001]).

Furthermore, this study presents clinical features and prognosis of 14 patients, including the 3 excluded ones (supplemental Figure 1; supplemental Tables 6 and 7) because the significance of these 3 variants remains uncertain. Accordingly, both multivariate and univariate analyses revealed that the presence of RUNX1 mutations correlated with the worse OS and EFS in this study.

In line with adult AML, RUNX1 mutations in our cohort were associated with adverse outcomes.17,22-25 Although previous research on pediatric AML could not establish the prognostic impact of RUNX1 mutations because of the limited number of patients and lack of integrated treatment regimens (supplemental Table 8),10-12 our study had a considerable sample size that confirmed the prognostic impact of RUNX1 mutations. Perhaps our research and other recent studies using next-generation sequencing could more precisely reveal the frequency and outcomes of RUNX1 mutations unlike previous studies using direct sequencing.10-12,17,22-25 Although this study did not completely confirm mutations as somatic mutations, the fact that patients with RUNX1 mutations demonstrated a significantly poor prognosis is crucial. Thus, this study suggests that RUNX1 mutations might be a poor prognostic factor in the risk classification for pediatric AML and clinicians should consider the adaptation of SCT after first CR for patients with RUNX1 mutations.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Yuki Hoshino for valuable assistance in performing the experiments. The authors thank Enago (www.enago.jp) for the English language review.

This work was supported by a research program of the Project for Development of Innovative Research on Cancer Therapeutics (P-Direct, 16cm0106501h0001), Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan, Practical Research for Innovative Cancer Control (15Ack0106014h0002, 16ck0106073h0003), Project for Cancer Research and Therapeutic Evolution (P-CREATE, 16cm0106501h0001) from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (S.O.), the Kawano Memorial Public Interest Incorporated Foundation for Promotion of Pediatrics, a Cancer Research grant, a grant for Research on Children and Families, and Research on Intractable Diseases, Health, and Labour Sciences Research Grants from the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare of Japan, a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B_24390268, C_25461611, 26461598, 26461599, and 17K10130) and Exploratory Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan, the Program for Promotion of Fundamental Studies in Health Sciences of the National Institute of Biomedical Innovation (NiBio) of Japan, and the Practical Research for Innovative Cancer Control from Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED_15ck0106066h0002).

Authorship

Contribution: G.Y., N.S., and Y. Hayashi designed the study and wrote the paper; G.Y., N.S., Y. Hara, K.O., and K.Y. performed the experiments; Y. Hayashi supervised the work; G.Y. and N.S. analyzed the results and constructed the figures; and all authors critically reviewed and revised the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Yasuhide Hayashi, Department of Hematology/Oncology, Gunma Children’s Medical Center, 779, Shimohakoda, Hokkitsu, Shibukawa, 377-8577 Gunma, Japan; e-mail: hayashiy-tky@umin.ac.jp.