Key Points

PTENα promotes neutrophil chemotaxis.

PTENα regulates neutrophil deformability through dephosphorylation of moesin.

Abstract

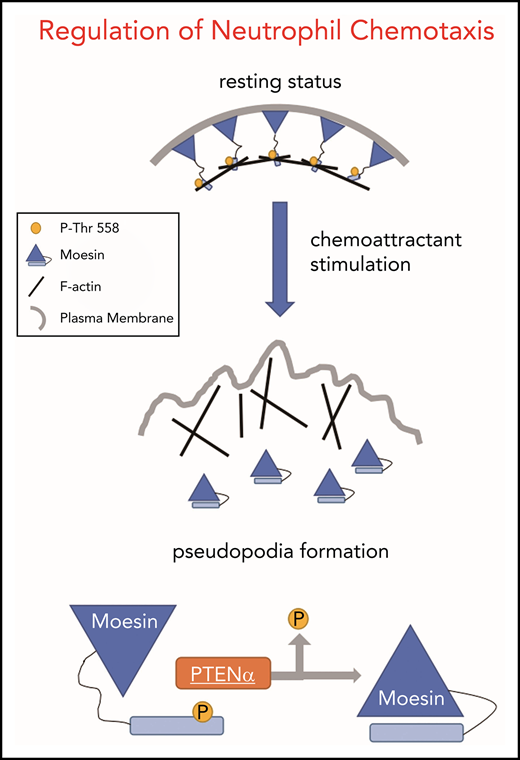

Neutrophils are a major component of immune defense and are recruited through neutrophil chemotaxis in response to invading pathogens. However, the molecular mechanism that controls neutrophil chemotaxis remains unclear. Here, we report that PTENα, the first isoform identified in the PTEN family, regulates neutrophil deformability and promotes chemotaxis of neutrophils. A high level of PTENα is detected in neutrophils and lymphoreticular tissues. Homozygous deletion of PTENα impairs chemoattractant-induced migration of neutrophils. We show that PTENα physically interacts with cell membrane cross-linker moesin through its FERM domain and dephosphorylates moesin at Thr558, which disrupts the association of filamentous actin with the plasma membrane and subsequently induces morphologic changes in neutrophil pseudopodia. These results demonstrate that PTENα acts as a phosphatase of moesin and modulates neutrophil-mediated host immune defense. We propose that PTENα signaling is a potential target for the treatment of infections and immune diseases.

Introduction

Neutrophils are the most abundant leukocytes in the circulation, and recruitment and activation of these cells are crucial for defense against invading pathogens. Neutrophils augment the inflammatory response, but they may also be involved in autoimmune disease and in promoting tumor metastasis.1-3 Inappropriate recruitment and activation of neutrophils may lead to tissue damage in the course of an autoimmune reaction or exaggerated inflammatory response. Hence, precise control of neutrophil movement is of particular importance.

The proteins ezrin, radixin, and moesin (ERM) are major components of the cytoskeleton and link filamentous actin (F-actin) to the plasma membrane. ERM proteins are highly conserved and contain an N-terminal FERM domain, a long α-helix linker region, and a C-terminal actin-binding domain.4 The FERM domain can also bind to the C-terminal domain, which suppresses cross-linking activity and forms an inactive conformation. Moesin is the predominant isoform of ERM protein in leukocytes, such as neutrophils.4,5 Altered phosphorylation at the C-terminal Thr558 residue of moesin weakens the FERM/C-terminal interaction6 and becomes an active conformation that tethers F-actin to the plasma membrane. In stationary neutrophils, RhoA-dependent phosphorylation of moesin stably links F-actin to the neutrophil plasma membrane by its C terminus, and this maintains the neutrophil in resting status,7 whereas the N-terminal FERM domain binds to integral membrane proteins, such as CD43, CD44, ICAM-1, ICAM-3, l-selectin, and PSGL-1.8-12 In response to chemoattractants, such as N-formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine (fMLP), which is a chemoattractant peptide released by bacteria, moesin is dephosphorylated on stimulated neutrophils, bringing about alterations in cell shape and chemotaxis. In addition to RhoA, several kinases can phosphorylate moesin on Thr558 in the course of cell motility, including PKC-θ13 and LOK.14 However, the identity of the protein that dephosphorylates moesin is unknown. One candidate is myosin phosphatase, which has been reported to interact with moesin in vivo,15 and another candidate is protein phosphatase 2C (PP2C), which shows phosphatase activity on highly purified phosphorylated T558 (p-T558) moesin.16

The tumor suppressor PTEN phosphatase has been described as a factor that is critical in directing neutrophils toward their end target chemoattractants by negatively regulating phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) activity.17,18 Previous studies have shown that PTEN localizes to the neutrophil uropod in response to CXCL8 or fMLP stimulation and converts PIP3 to PIP2. This promotes migration directed by a gradient of PIP3 at the leading edge of the uropod, which requires p38 and its effector kinase MK2.19-21 However, PTEN-deficient neutrophils show more pseudopodia with random movement, and migration of these cells is only weakly directional after stimulation.17 On the other hand, PTEN-deficient neutrophils show more Akt activation and stronger fMLP-induced chemotaxis, which support the idea that PTEN disruption will not lead to a chemotaxis defect.22 Work with PI3K-inhibited cells has identified a PI3K-independent pathway in mediating long-term migration to fMLP, indicating that PI3K accelerates, but is not required for, neutrophil chemotaxis to fMLP.23 The function of PTEN and PTEN family proteins in neutrophil chemotaxis remains unclear. Thus, it is increasingly clear that PTEN gives neutrophils direction24 ; however, several new isoforms of PTEN have recently been identified,25-27 raising the question of whether canonical PTEN or an isoform functions in neutrophil biology and casting doubt on previous characterizations of PTEN function in neutrophils.

PTENα is the first identified PTEN family isoform, and its translation is initiated at a CUG codon in the 5′-untranslated region of PTEN messenger RNA (mRNA).25 To evaluate functional differences in PTEN and PTENα, we have established a PTENα-specific knockout mouse model by replacing the mouse PTENα start codon with GGA in the mouse genome.26 We observed that PTENα-deficient neutrophils show diminished polarity and motility after chemoattractant stimulation, which are dependent on regulation of F-actin dynamics through dephosphorylation of the cross-linker moesin at T558.

Materials and methods

Mice

The experimental PTENα-specific knockout mice were established by gene targeting, using a replacement strategy based on homologous recombination.26 Male and female mice were kept in a special pathogen-free facility at Peking University Care Industrial Park and were used for experiments at 6 to 8 weeks of age. All procedures were approved and monitored by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Peking University.

Isolation of murine neutrophils

Bone marrow–derived neutrophils were isolated by Percoll gradients, as described by Phillipson et al28 and Kjeldsen et al.29 Mice were euthanized, and bone marrow was removed from the femurs by perfusion of 6 mL of cold phosphate buffered saline (PBS). Bone marrow cells were pelleted by centrifugation and resuspended in 2 mL of PBS. Percoll solutions were prepared by mixing Percoll solution (Pharmacia) and 10× PBS at a 1:9 ratio to obtain a 100% Percoll stock, which was diluted with PBS for gradients of 72%, 60%, and 52%. Prior to centrifugation (1100g, 30 minutes), marrow cell suspensions were loaded in the uppermost layer. The neutrophils were collected in the band between the 72% and 60% layers.

Transwell chemotaxis assay

For improved stimulation of isolated murine neutrophils in subsequent experiments, WKYMVm (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) was used as a substitute for fMLP, and MIP-2 (BioLegend, San Diego, CA) was used as a substitute for interleukin-8. The purified neutrophils were plated into the upper compartment of the Transwell, and RPMI 1640 medium, with or without chemoattractants, was added to the lower wells beneath the polycarbonate membrane. The number of cells in the lower well was counted using a hemocytometer after 1 hour of stimulation. In addition, we evaluated cell invasion with the same chemotaxis assay following fMLP stimulation for 20 minutes. The fixed membrane and the cells were stained with crystal violet. The number of stained cells was counted in 5 random fields after cells attached to the surface of the membrane were scraped, and the percentage of migrating cells was calculated by dividing the number of invading cells by the number of seeded cells per insert.

F-actin confocal microscopy

Bone marrow–derived murine neutrophils (6 × 105) were plated on glass-bottomed dishes and allowed to adhere for 20 minutes in a 37°C, 5% CO2 (volume-to-volume ratio) incubator. After stimulation with 100 nM fMLP or 25 ng/mL MIP-2 for 10 minutes, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100. After incubation with phalloidin (F-actin stain) for 1 hour at room temperature, cover glasses were mounted with mounting medium containing 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; nuclear stain). A TCS A1 microscope (Nikon, Melville, NY) was used for confocal microscopy.

Results

PTENα physically interacts with moesin

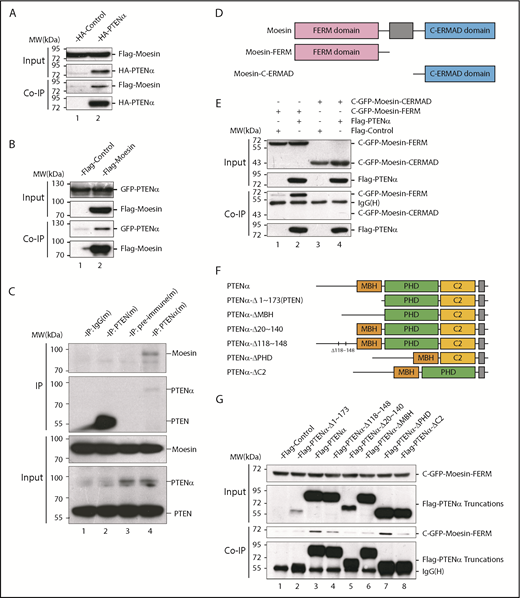

Following the discovery of new PTEN isoforms, there has been intensive investigation into the diversity of functions specific to these isoforms. At the outset, to investigate functions unique to PTENα, various mouse tissues were evaluated for PTENα protein expression with an anti-PTEN antibody. PTENα is highly expressed in a variety of lymphoreticular tissues, particularly in bone marrow (supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood Web site). S-tagged PTEN and PTENα were subsequently purified with S-protein beads from HEK293T transiently transfected cells. Upon incubation of the beads with lysates from mouse bone marrow, followed by mass spectrometry, we found that all of the ERM family members, including ezrin, radixin and moesin, have high binding scores in PTENα-specific precipitates (supplemental Table 1). To confirm these high-avidity interactions, hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged PTENα was transfected together with Flag-tagged ERM family members 1 by 1 into HEK293T cells. According to the coimmunoprecipitation results, PTENα associated directly with moesin rather than radixin or ezrin (Figure 1A; supplemental Figure 2A). To eliminate the possibility that these results were influenced by the fusional tag, interaction of PTENα and moesin was also confirmed by reverse coprecipitation with different tags (Figure 1B). In addition, PTENα and moesin showed identical interactions, using immunoprecipitation, in mouse bone marrow and thioglycollate-elicited peritoneal cells (Figure 1C; supplemental Figure 2C). In contrast, there was no evidence that canonical PTEN was associated with moesin in vitro (supplemental Figure 2B) or in vivo (Figure 1C; supplemental Figure 2C).

PTENα physically interacts with moesin. (A) In vitro binding of PTENα and moesin. HEK293T cells were cotransfected with S-tag–PTENα and Flag-moesin, and cell lysates were pulled down with S-protein beads and subjected to immunoblot with FLAG or HA antibody. (B) In vitro binding of moesin and PTENα. HEK293T cells were cotransfected with Flag-moesin and GFP-PTENα, and cell lysates were pulled down with Flag beads and subjected to immunoblot with GFP or Flag antibody. (C) In vivo immunoprecipitation. Lysates of mouse thioglycollate-elicited peritoneal cells were immunoprecipitated with an anti-PTENα or anti-PTEN antibody and immunoblotted with an anti-moesin antibody. PTENα, but not PTEN, physically associates with moesin (lane 4 vs. lane 2). (D-E) PTENα binds to the moesin FERM region. (D) Sketch map of truncated moesin. (E) HEK293T cells were cotransfected with Flag-PTENα and the GFP-tagged FERM domain or the C-terminal ERM-association domain of moesin (C-ERMAD), and cell lysates were pulled down with anti-Flag antibody and subjected to immunoblot with GFP or Flag antibody. PTENα physically associates with FERM domain of moesin (lane 2 vs. lane 4). (F-G) The interaction between PTENα and the moesin-FERM domain depends on its sequence at the N terminus, which is not found in PTEN. (F) Diagram of multiple truncations or deletions of PTENα. (G) Different truncation or deletion vectors of PTENα and the GFP-tagged moesin-FERM domain were cotransfected into HEK293T cells, and cell lysates were pulled down with anti-Flag antibody and subjected to immunoblot with GFP or Flag antibody. The moesin FERM domain was not immunoprecipitated by PTENαΔ1-173 (lane 2) or PTENαΔ20-140 (lane 5). MBH, membrane binding helix; PHD, plekstrin homology domain.

PTENα physically interacts with moesin. (A) In vitro binding of PTENα and moesin. HEK293T cells were cotransfected with S-tag–PTENα and Flag-moesin, and cell lysates were pulled down with S-protein beads and subjected to immunoblot with FLAG or HA antibody. (B) In vitro binding of moesin and PTENα. HEK293T cells were cotransfected with Flag-moesin and GFP-PTENα, and cell lysates were pulled down with Flag beads and subjected to immunoblot with GFP or Flag antibody. (C) In vivo immunoprecipitation. Lysates of mouse thioglycollate-elicited peritoneal cells were immunoprecipitated with an anti-PTENα or anti-PTEN antibody and immunoblotted with an anti-moesin antibody. PTENα, but not PTEN, physically associates with moesin (lane 4 vs. lane 2). (D-E) PTENα binds to the moesin FERM region. (D) Sketch map of truncated moesin. (E) HEK293T cells were cotransfected with Flag-PTENα and the GFP-tagged FERM domain or the C-terminal ERM-association domain of moesin (C-ERMAD), and cell lysates were pulled down with anti-Flag antibody and subjected to immunoblot with GFP or Flag antibody. PTENα physically associates with FERM domain of moesin (lane 2 vs. lane 4). (F-G) The interaction between PTENα and the moesin-FERM domain depends on its sequence at the N terminus, which is not found in PTEN. (F) Diagram of multiple truncations or deletions of PTENα. (G) Different truncation or deletion vectors of PTENα and the GFP-tagged moesin-FERM domain were cotransfected into HEK293T cells, and cell lysates were pulled down with anti-Flag antibody and subjected to immunoblot with GFP or Flag antibody. The moesin FERM domain was not immunoprecipitated by PTENαΔ1-173 (lane 2) or PTENαΔ20-140 (lane 5). MBH, membrane binding helix; PHD, plekstrin homology domain.

Moesin has a characteristic plasma membrane–associated FERM domain and a C-terminal ERM-association domain,5 and we showed that PTENα binds specifically to the moesin FERM domain (Figure 1D-E). PTENα differs from PTEN in its amino acid sequence 1-173, which PTEN lacks.25 A series of truncated or internally deleted PTENα mutants were generated to further characterize the interaction of PTENα and the moesin FERM domain (Figure 1F). As shown in Figure 1G, the GFP-tagged moesin FERM domain was immunoprecipitated by full-length PTENα and most of the PTENα mutants. However, the moesin FERM domain fails to interact with PTENαΔ1-173 (equivalent to canonical PTEN) or PTENαΔ20-140, arguing that the 20-140 aa fragment of PTENα is required for the interaction of moesin and PTENα.

Chemoattractant-induced pseudopodia formation and polarization are decreased in PTENα-deficient neutrophils

Moesin is an important component of the cytoskeleton and links F-actin to the plasma membrane, which is required for cell motility and migration of leukocytes. Neutrophils are recruited to sites of inflammation or infection; therefore, unobstructed movement is particularly important for their function. Demonstration of the specific interaction of PTENα and moesin raised the possibility that PTENα plays a role in neutrophil migration.

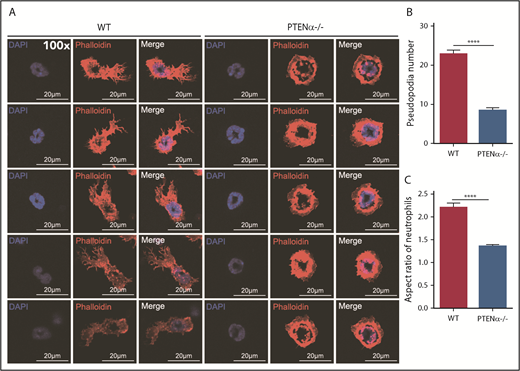

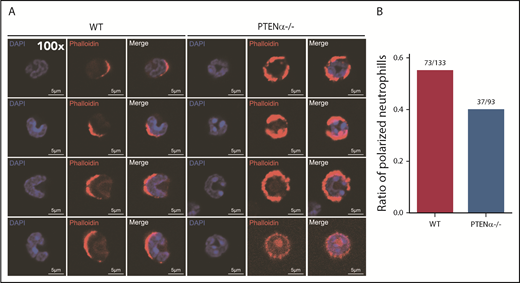

A PTENα-knockout mouse model was established by replacing PTENα CTG347 and CTG362 with GGA in the mouse genome.26 PTEN and PTENα translate from the same mRNA, but this knockout model allowed complete experimental ablation of PTENα while leaving PTEN expression intact. Knockout of PTENα was validated by showing complete abolition of PTENα protein, whereas, at the same time, PTEN maintained its original normal expression level in neutrophils isolated from bone marrow of PTENα-deficient mice (supplemental Figure 3A). Hereafter, this homozygous PTENα-knockout mouse is designated PTENα−/−. To visualize the morphologic change in PTENα−/− neutrophils, F-actin was stained with Alexa Fluor 555–labeled phalloidin after stimulation with fMLP or MIP-2. Wild-type (WT) and PTENα−/− neutrophils formed pseudopodia following identical fMLP stimulation (Figure 2A). However, the pseudopodia in WT neutrophils were much more distinct than those in PTENα−/− neutrophils (Figure 2A-B), and changes in cellular morphology were more pronounced, as evaluated by quantitation of the aspect ratio in WT neutrophils compared with PTENα−/− neutrophils (Figure 2A,C). The baseline number of unstimulated cells is shown in supplemental Figure 4A. Two videos of this experiment are included (supplemental Videos 1 and 2), in which WT neutrophils show much more aggressive behavior than PTENα−/− neutrophils under uniform stimulation of fMLP. Moreover, under identical stimulation with MIP-2, >50% of WT neutrophils showed visible polarization, and the fraction of polarized PTENα−/− neutrophils was <40% (Figure 3). All of these chemoattractant-elicited responses are mediated by heterotrimeric G protein–coupled receptors.30,31 To determine whether the more aggressive responses in WT neutrophils are mediated by differences in receptor concentration, we evaluated expression levels in a series of receptors in marrow cells using quantitative polymerase chain reaction; no significant differences were observed between WT and PTENα−/− neutrophils (supplemental Figure 3B).

Formation of chemoattractant-induced pseudopodia in WT and PTENα−/− neutrophils. (A) Visualization of formation of pseudopodia and changes in cellular morphology in isolated neutrophils after fMLP stimulation. Cells were stained with phalloidin (F-actin stain) and DAPI (nuclear stain). The images were acquired using a Nikon TCS A1 confocal microscope (100× lens objective). (B) The numbers of WT and PTENα−/− neutrophil pseudopodia (n = 50) were counted after fMLP stimulation. (C) Analysis of the aspect ratio (ratio of the longest axis to the shortest perpendicular axis) of WT and PTENα−/− neutrophils (n = 50) after fMLP stimulation. Data are mean ± standard error of the mean. ****P < .0001, 2-tailed unpaired Student t test.

Formation of chemoattractant-induced pseudopodia in WT and PTENα−/− neutrophils. (A) Visualization of formation of pseudopodia and changes in cellular morphology in isolated neutrophils after fMLP stimulation. Cells were stained with phalloidin (F-actin stain) and DAPI (nuclear stain). The images were acquired using a Nikon TCS A1 confocal microscope (100× lens objective). (B) The numbers of WT and PTENα−/− neutrophil pseudopodia (n = 50) were counted after fMLP stimulation. (C) Analysis of the aspect ratio (ratio of the longest axis to the shortest perpendicular axis) of WT and PTENα−/− neutrophils (n = 50) after fMLP stimulation. Data are mean ± standard error of the mean. ****P < .0001, 2-tailed unpaired Student t test.

Polarization is decreased in stimulated PTENα−/− neutrophils. (A) Increased numbers of WT neutrophils showed visible polarization after MIP-2 stimulation. Cells were stained with phalloidin (F-actin stain) and DAPI (nuclear stain). The images acquired using a Nikon TCS A1 confocal microscope (100× lens objective). (B) The percentages of polarized WT (n = 133) and PTENα−/− (n = 93) neutrophils (F-actin localizing at the leading edge of the cell) were recorded after MIP-2 stimulation.

Polarization is decreased in stimulated PTENα−/− neutrophils. (A) Increased numbers of WT neutrophils showed visible polarization after MIP-2 stimulation. Cells were stained with phalloidin (F-actin stain) and DAPI (nuclear stain). The images acquired using a Nikon TCS A1 confocal microscope (100× lens objective). (B) The percentages of polarized WT (n = 133) and PTENα−/− (n = 93) neutrophils (F-actin localizing at the leading edge of the cell) were recorded after MIP-2 stimulation.

PTENα is colocalized with moesin at the apical domain of pseudopodia and increases neutrophil deformability through dephosphorylation of moesin at T558

It has been shown that PTENα is specifically expressed in mitochondria in mouse embryonic fibroblasts.26 As a result of tissue specificity, PTENα protein is enriched in cytoplasm, instead of mitochondria, in bone marrow cells (supplemental Figure 3C). We also evaluated the impact of PTENα on mitochondrial functions via several assays. As shown in supplemental Figure 3D-G, there is no difference with regard to adenosine triphosphate production, COX content or activity, or mitochondrial membrane potential between WT and PTENα−/− bone marrow cells.

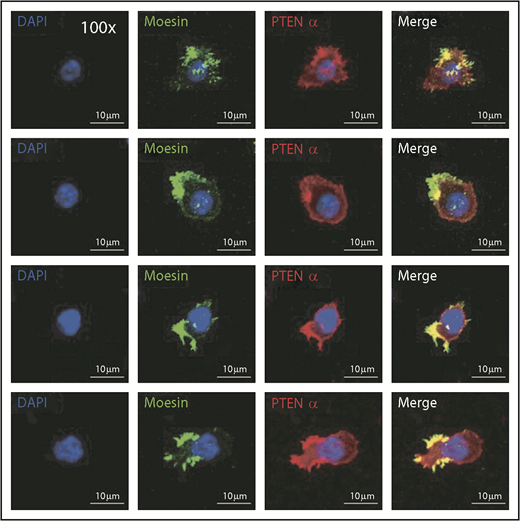

Immunofluorescence was used to evaluate the mechanism by which PTENα influences neutrophil mobility, and it showed that endogenous PTENα is colocalized with moesin at the apical domain of pseudopodia (Figure 4). We also stained the stimulated and unstimulated neutrophils with 4 different proteins including PTENα, moesin, F-actin, and MLC. As shown in supplemental Figure 4B, we found that PTENα interacts uniformly with moesin around the cell membrane in the resting neutrophil. When the neutrophil was activated by fMLP, PTENα localized to the uropod that was stained with MLC2 and phalloidin; meanwhile, PTENα colocalized with moesin and phalloidin.

PTENα colocalizes with moesin at the apical domain of pseudopodia in neutrophils. Harvested cells were stained with anti-PTENα antibody, anti-moesin antibody, and DAPI (nuclear stain). The images were acquired as 3-channel images using a Nikon TCS A1 confocal microscope (100× lens objective).

PTENα colocalizes with moesin at the apical domain of pseudopodia in neutrophils. Harvested cells were stained with anti-PTENα antibody, anti-moesin antibody, and DAPI (nuclear stain). The images were acquired as 3-channel images using a Nikon TCS A1 confocal microscope (100× lens objective).

A previous study showed that PIP3 signaling is elevated in PTEN−/− neutrophils.22 Chemokines or fMLP elicit a rapid increase in PIP3, which may be monitored by measuring Akt phosphorylation. Akt phosphorylation was identical in fMLP-stimulated WT and PTENα−/− neutrophils (supplemental Figure 5A-B). A previous study in Dictyostelium discoideum has shown that upregulated PIP3 signaling increases F-actin levels.32 As shown in supplemental Figure 5C, we found that chemoattractant-elicited actin polymerization was identical in fMLP-stimulated WT and PTENα−/− neutrophils. Thus, it appeared that PTENα is not involved in regulation of the dynamic distribution of PI3K at the front of the chemoattractant-stimulated neutrophils.

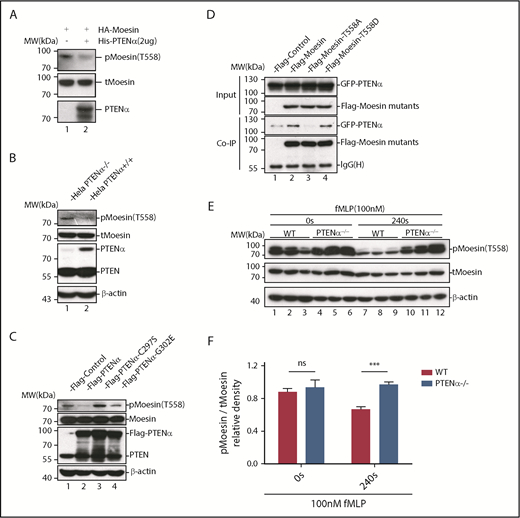

Upon chemoattractant stimulation, neutrophils polarize and migrate in concert with dephosphorylation of moesin at T558, and constitutively phosphorylated moesin (p-moesin) inhibits cell migration.5,33 This indicates that PTENα acts as a protein phosphatase and dephosphorylates active moesin in chemoattractant-stimulated neutrophils. p-moesin was precipitated from HEK293T cells that were transfected to express S-tagged moesin. After incubation with His-tagged PTENα protein purified from SF9 cells, moesin dephosphorylation was quantified by western blot with an anti-p-moesin (T558) antibody. As shown in Figure 5A, moesin was dephosphorylated after incubation with PTENα protein in vitro. In addition, staining with an anti-p-moesin (T558) antibody p-moesin (T558) was increased in PTENα−/− HeLa cells26 in comparison with WT HeLa cells (Figure 5B). To further determine whether PTENα phosphatase activity affects dephosphorylation of moesin at T558, p-moesin (T558) was evaluated in PTENα−/− HeLa cells after transient transfection with PTENα WT, PTENα-C297S (equivalent to PTEN-C124S, which shows inactivation of lipid and protein phosphatase activity), or PTENα-G302E (equivalent to PTEN-G129E, which shows inactivation of lipid phosphatase activity). As shown in Figure 5C, only PTENα-C297S mutant did not dephosphorylate moesin at T558, indicating that protein phosphatase activity is required for PTENα to function in moesin dephosphorylation. We also observed that GFP-tagged PTENα did not effectively coimmunoprecipitate Flag-tagged moesin-T558A (inactive conformation) compared with moesin-T558D (active conformation) (Figure 5D). To confirm this finding, the ability of PTENα to phosphorylate moesin in vivo was evaluated by determining the amount of p-moesin in isolated neutrophils before and after stimulation with fMLP. Upon stimulation, p-moesin was significantly reduced in neutrophils from WT mice but was not reduced in PTENα−/− neutrophils (Figure 5E-F).

PTENα increases neutrophil deformability through dephosphorylation of moesin at T558. (A) In vitro dephosphorylation assay. HA-tagged moesin was purified using S-protein agarose beads (Novagen) from transfected HEK293T cells. After incubation, with or without purified PTENα, in dephosphorylation buffer at room temperature for 40 minutes, beads were washed and boiled with sodium dodecyl sulfate loading buffer. Dephosphorylation of moesin (p-moesin) was evaluated with anti–p-moesin (T558) antibody (1:5000; Abcam), and total moesin (t-moesin) was evaluated with anti-moesin antibody (1:2000; Abcam). (B) p-Moesin and t-moesin were evaluated in HeLa WT and HeLa PTENα−/− cell lysates with anti–p-moesin (T558) and anti-moesin antibody, respectively. (C) p-Moesin and t-moesin were evaluated in HeLa PTENα−/− cells 72 hours after transfection with tag vector, tagged PTENα, and 2 inactivated mutants (C297S and G302E). Only the PTENα-C297S mutant did not dephosphorylate moesin at T558 (lane 3). (D) Different FLAG-tagged moesin mutants and GFP-tagged PTENα were cotransfected into HEK293T cells, and cell lysates were pulled down with anti-Flag antibody and subjected to immunoblot with GFP or Flag antibody. The inactive conformation of moesin (T558A) did not effectively coimmunoprecipitate with PTENα (lane 3 vs. lanes 2 and 4). (E-F) Immunoblot analysis of p-moesin and t-moesin in isolated neutrophils (1-2 × 106) Neutrophils were pelleted and lysed after stimulation with 100nM fMLP for 240 seconds or were left unstimulated. p-moesin and t-moesin were evaluated with western blot (E) and were analyzed by densitometric quantification (F) (n = 3 mice). Results are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean. ***P < .001, 2-way repeated-measures ANOVA, followed by the Bonferroni post test. ns, not significant (P > .05).

PTENα increases neutrophil deformability through dephosphorylation of moesin at T558. (A) In vitro dephosphorylation assay. HA-tagged moesin was purified using S-protein agarose beads (Novagen) from transfected HEK293T cells. After incubation, with or without purified PTENα, in dephosphorylation buffer at room temperature for 40 minutes, beads were washed and boiled with sodium dodecyl sulfate loading buffer. Dephosphorylation of moesin (p-moesin) was evaluated with anti–p-moesin (T558) antibody (1:5000; Abcam), and total moesin (t-moesin) was evaluated with anti-moesin antibody (1:2000; Abcam). (B) p-Moesin and t-moesin were evaluated in HeLa WT and HeLa PTENα−/− cell lysates with anti–p-moesin (T558) and anti-moesin antibody, respectively. (C) p-Moesin and t-moesin were evaluated in HeLa PTENα−/− cells 72 hours after transfection with tag vector, tagged PTENα, and 2 inactivated mutants (C297S and G302E). Only the PTENα-C297S mutant did not dephosphorylate moesin at T558 (lane 3). (D) Different FLAG-tagged moesin mutants and GFP-tagged PTENα were cotransfected into HEK293T cells, and cell lysates were pulled down with anti-Flag antibody and subjected to immunoblot with GFP or Flag antibody. The inactive conformation of moesin (T558A) did not effectively coimmunoprecipitate with PTENα (lane 3 vs. lanes 2 and 4). (E-F) Immunoblot analysis of p-moesin and t-moesin in isolated neutrophils (1-2 × 106) Neutrophils were pelleted and lysed after stimulation with 100nM fMLP for 240 seconds or were left unstimulated. p-moesin and t-moesin were evaluated with western blot (E) and were analyzed by densitometric quantification (F) (n = 3 mice). Results are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean. ***P < .001, 2-way repeated-measures ANOVA, followed by the Bonferroni post test. ns, not significant (P > .05).

On the other hand, myosin phosphatase is a key frontness molecule that is activated and recruited to dephosphorylate moesin at the prospective leading edge to establish polarity in activated neutrophils.33 We also assessed the localization and expression of myosin phosphatase 1 and 2 and found that PTENα deficiency did not have any effect (supplemental Figure 6A-B). As shown in supplemental Figure 6C, the activity of phosphatases is increased in PTENα−/− neutrophils, which is represented by the relative expression of phosphorylated MLC2 (S19).

These results demonstrate that PTENα physically interacts with the moesin FERM domain and regulates deformability of migrating neutrophils at the backness through dephosphorylation of p-moesin at T558. Although myosin phosphatases and PTENα deactivate moesin under chemoattractant stimulation in neutrophils, the opposite direction of recruitment within a cell leads those phosphatases to be indispensable.

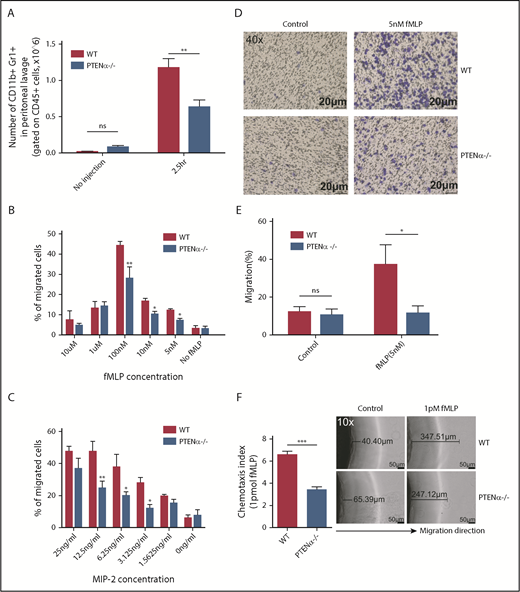

Disruption of PTENα attenuates chemoattractant-induced migration and chemotaxis in neutrophils in vivo and in vitro

We next sought to determine whether migration toward a chemoattractant was significantly impeded in PTENα−/− neutrophils. As shown in Figure 6A, in the thioglycollate-induced acute peritonitis model, the number of PTENα−/− neutrophils was significantly less than that of WT neutrophils on 2.5 hours recruitment. Elicited neutrophils are represented by the absolute number of CD11b+Gr1+ (gated on CD45+) cells. We also determined the number of macrophages (CD11b+F4/80+ cells) and dendritic cells (CD11c+Gr1− cells) before and after thioglycollate stimulation (supplemental Figure 7A-B). There was no significant difference in elicited and localized macrophages or dendritic cells in peritoneal lavage fluid from WT and PTENα−/− mice. In addition, there was no difference in the number of WT vs. PTENα−/− neutrophils in bone marrow (supplemental Figure 7C), which argues that PTENα does not influence the production of neutrophils. To further investigate the influence of PTENα deficiency on neutrophil recruitment and migration, Transwell chemotaxis and under-agarose cell-migration assays were used. Chemotaxis is a process in which circulating effector leukocytes, such as neutrophils, sense and move toward a chemoattractant. As shown in Figure 6B, WT and PTENα−/− neutrophils stimulated by a gradient of fMLP produced a dose-dependent and bell-shaped migration curve that peaked at 100 nM fMLP, and significantly more WT neutrophils migrated into the lower wells with fMLP concentrations of 100 nM, 10 nM, and 5nM. Consistent with findings under the MIP-2 stimulation, the proportion of PTENα−/− neutrophils that migrated into the lower wells was significantly smaller than that of WT neutrophils with varied concentrations of MIP-2 (Figure 6C). Chemokinesis control is shown in supplemental Figure 7D. In addition, a higher percentage of WT neutrophils than PTENα−/− neutrophils invaded the membrane (Figure 6D-E). To further characterize the consequence of PTENα deficiency in neutrophil chemotaxis, an in vitro under-agarose cell-migration assay that is a recognized method for the study of chemotactic responses was used; significantly, WT neutrophils moved longer distances toward fMLP within the prescribed time in comparison with PTENα−/− neutrophils (Figure 6F). These findings demonstrate that disruption of PTENα in neutrophils indeed leads to a reduction in their ability to migrate toward chemoattractants in vivo and in vitro.

Disruption of PTENα attenuates chemoattractant-induced migration and chemotaxis in vivo and in vitro. (A) Absolute number of neutrophils in elicited peritoneal cells without injection or after intraperitoneal injection with thioglycollate. BD Trucount Absolute count tubes were used to count absolute cell numbers. Data represent mean ± SEM (≥6 mice in each group). This result was successfully repeated in 3 independent experiments with 4 or 5 mice per group. **P < .01, 2-way repeated-measures ANOVA, followed by the Bonferroni post test. (B-C) In vitro Transwell chemotaxis. The percentage of neutrophils that migrated into lower wells in response to concentration gradients of fMLP (B) and MIP-2 (C). *P < .05, **P < .01, 2-way repeated-measures ANOVA, followed by the Bonferroni post test. (D-E) Number of neutrophils that invaded the membrane in response to 5 nM fMLP. (D) Invading neutrophils were stained with crystal violet; random invasion control (left panels) and fMLP-stimulated invasion (right panels) are shown. An IX53 Inverted Microscope and Olympus cellSens image-acquisition software (both from Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) were used for image capture (40× lens objective). (E) The percentage of migrating cells was calculated as the number of invading cells divided by the number of seeded cells. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments with a total of 3 or 4 mice per group (mean ± standard error of the mean). *P < .05, 2-way repeated-measures ANOVA, followed by the Bonferroni post test. ns, not significant (P > .05). (F) In vitro under-agarose cell-migration assay. The chemotaxis index is represented by the distance of directional migrated neutrophils. Images are shown in the right panel. WT neutrophils (upper right panels) and PTENα−/− neutrophils (lower right panels) were treated with 1 pM fMLP, and chemotaxis toward fMLP was determined. An IX53 Inverted Microscope and Olympus cellSens image-acquisition software were used for image capture (10× lens objective). Data are representative of 3 independent experiments with a total of 4 or 5 mice per group (mean ± standard error of the mean). ***P < .001, 2-tailed unpaired Student t test.

Disruption of PTENα attenuates chemoattractant-induced migration and chemotaxis in vivo and in vitro. (A) Absolute number of neutrophils in elicited peritoneal cells without injection or after intraperitoneal injection with thioglycollate. BD Trucount Absolute count tubes were used to count absolute cell numbers. Data represent mean ± SEM (≥6 mice in each group). This result was successfully repeated in 3 independent experiments with 4 or 5 mice per group. **P < .01, 2-way repeated-measures ANOVA, followed by the Bonferroni post test. (B-C) In vitro Transwell chemotaxis. The percentage of neutrophils that migrated into lower wells in response to concentration gradients of fMLP (B) and MIP-2 (C). *P < .05, **P < .01, 2-way repeated-measures ANOVA, followed by the Bonferroni post test. (D-E) Number of neutrophils that invaded the membrane in response to 5 nM fMLP. (D) Invading neutrophils were stained with crystal violet; random invasion control (left panels) and fMLP-stimulated invasion (right panels) are shown. An IX53 Inverted Microscope and Olympus cellSens image-acquisition software (both from Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) were used for image capture (40× lens objective). (E) The percentage of migrating cells was calculated as the number of invading cells divided by the number of seeded cells. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments with a total of 3 or 4 mice per group (mean ± standard error of the mean). *P < .05, 2-way repeated-measures ANOVA, followed by the Bonferroni post test. ns, not significant (P > .05). (F) In vitro under-agarose cell-migration assay. The chemotaxis index is represented by the distance of directional migrated neutrophils. Images are shown in the right panel. WT neutrophils (upper right panels) and PTENα−/− neutrophils (lower right panels) were treated with 1 pM fMLP, and chemotaxis toward fMLP was determined. An IX53 Inverted Microscope and Olympus cellSens image-acquisition software were used for image capture (10× lens objective). Data are representative of 3 independent experiments with a total of 4 or 5 mice per group (mean ± standard error of the mean). ***P < .001, 2-tailed unpaired Student t test.

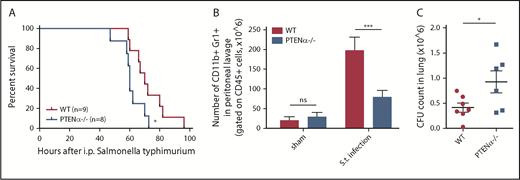

Disruption of PTENα impairs host immune defense against Salmonella typhimurium infection

Neutrophils are the first line of immune defense against invading bacteria. In consideration of the reduction in the chemotaxis ability of PTENα−/− neutrophils, we speculated that resistance to bacterial infection could be suppressed in PTENα-deficient mice. Salmonella infection can cause severe enteric diseases in humans and in animals.34 Murine infections with Salmonella typhimurium are a significant cause of mortality. To prepare the S typhimurium infection model, each mouse was injected intraperitoneally with a uniform concentration of motile bacteria. Significantly, PTENα-deficient mice experienced acute infection that led to death more quickly compared with WT mice (Figure 7A). We also found that the number of recruited neutrophils in the peritoneal lavage fluid of WT control mice was much greater than that in PTENα-deficient mice 6 hours postinfection (Figure 7B). Meanwhile, viable bacterial (CFU) recovered from the lung of infected mice were assessed; CFU counts were significantly higher in PTENα-deficient mice compared with WT mice (Figure 7C). These results indicate that disruption of PTENα gives rise to a deformability defect in neutrophils that reduces host immune defense.

Disruption of PTENα impairs host immune defense against S typhimurium infection. (A) Mouse survival curves post–S typhimurium infection. WT mice (n = 9) and PTENα−/− mice (n = 8) were inoculated intraperitoneally with uniform amounts of bacteria. *P < .05, Mantel-Cox test. (B) Absolute number of neutrophils in elicited peritoneal cells with sham treatment or after intraperitoneal injection of S typhimurium (S.t.). BD Trucount Absolute count tubes were used to count absolute cell numbers. Data represent ≥6 mice derived from 3 independent experiments in each group (mean ± standard error of the mean). ***P < .001, 2-way repeated-measures ANOVA, followed by the Bonferroni post test. (C) Viable bacterial CFU in lungs of mice postinfection. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments with a total of 6 or 7 mice per group (mean ± standard error of the mean). *P < .05, 2-tailed unpaired Student t test. ns, not significant (P > .05).

Disruption of PTENα impairs host immune defense against S typhimurium infection. (A) Mouse survival curves post–S typhimurium infection. WT mice (n = 9) and PTENα−/− mice (n = 8) were inoculated intraperitoneally with uniform amounts of bacteria. *P < .05, Mantel-Cox test. (B) Absolute number of neutrophils in elicited peritoneal cells with sham treatment or after intraperitoneal injection of S typhimurium (S.t.). BD Trucount Absolute count tubes were used to count absolute cell numbers. Data represent ≥6 mice derived from 3 independent experiments in each group (mean ± standard error of the mean). ***P < .001, 2-way repeated-measures ANOVA, followed by the Bonferroni post test. (C) Viable bacterial CFU in lungs of mice postinfection. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments with a total of 6 or 7 mice per group (mean ± standard error of the mean). *P < .05, 2-tailed unpaired Student t test. ns, not significant (P > .05).

Discussion

Neutrophil recruitment and activation are essential for defense against invading pathogens. However, inappropriate recruitment or hyperactivation may lead to damage to surrounding tissue. Therefore, precise control of neutrophil movement is of particular importance. Neutrophil chemotaxis is regulated by 2 signaling pathways. Chemokine-induced migration is dependent on the PI3K pathway, and migration induced by end-target chemoattractants (such as fMLP or C5a) is regulated by the p38 mitogen–activated protein kinase pathway, which is the more dominant of these 2 pathways.24 There is now much evidence indicating that PTEN plays a role in controlling the direction of neutrophil chemotaxis. PTEN redistribution in neutrophils during end-target stimulation is directly regulated by p38.17 It is reported that fMLP induces localization of PTEN to the uropod, inhibiting PIP3 production and mediating directional sensing.20,32 Mice with PTEN−/− neutrophils show defective clearance of bacteria and have a greater duration of infection.17 In contrast, a previous study22 showed that PTEN−/− neutrophils display more aggressive behavior during infection and enhance chemotaxis, consistent with other previous studies.35,36 fMLP-induced chemotaxis in PTEN−/− neutrophils shows much more extensive Akt activation and produces more pseudopodia after chemoattractant stimulation in comparison with WT neutrophils, which suggests that generation of PIP3 is not required for fMLP-induced migration.17,22 In this study, we identify a new PI3K-independent mechanism to explain how PTENα−/− neutrophils attenuate chemoattractant-induced formation of distinct pseudopodia, as well as the polarization, migration, and chemotaxis of these cells.

PTENα is alternatively translated from the same mRNA as canonical PTEN. In previous studies, neutrophils isolated from PTEN conditional-knockout mice with a loxP-Cre system, such as ElaCrePTENfl mice,17 were thought to be depleted of PTEN alone, when in fact these cells were depleted of PTEN and PTENα. Thus, the unique contribution of PTENα to neutrophil mobility was obscured by the experimental conditions. By replacing the PTENα start codon with GGA, we established a knock-in mouse model of conventional PTENα-specific depletion with retaining intact PTEN and without embryonic lethality.26 Using this model, we found that PTENα−/− neutrophils are much less responsive to chemoattractants and are characterized by a lack of polarization and pseudopodia formation. Impaired chemotaxis and decreased recruitment to sites of inflammation indicate that the motility of PTENα−/− neutrophils is severely disrupted. Moreover, because canonical PTEN expression remains intact, PTENα−/− neutrophils do not exhibit a significant difference in Akt phosphorylation after fMLP stimulation. This indicates that PTENα−/− neutrophils can still sense the direction of chemoattractant, and PIP3 accumulation at the leading edge of the neutrophil is not impeded. Investigation of the mechanism involved demonstrates that PTENα, but not PTEN, specifically binds to the moesin FERM domain and dephosphorylates moesin at T558. Dephosphorylation of neutrophil moesin brings about conversion of the cell from a stationary state to its active form.7 ,33 Unobstructed spatiotemporal regulation of moesin in migrating neutrophils allows a serial process of cell shape change at the backness, including uropod retraction.5 These findings enrich our understanding of F-actin dynamics in polarity and motility. Although PTENα−/− neutrophils show conspicuous impairment of deformability, chemotaxis in these cells can still be triggered by chemoattractants. The fact that PTENα−/− neutrophil movement is not completely restrained indicates the involvement of other phosphatases in the regulation of moesin dephosphorylation during neutrophil migration, and/or other kinases, phosphatases, or their regulators that are still unidentified.

Hierarchal activity is crucial for effective responses to chemoattractants in neutrophils. When chemotaxis is triggered in neutrophils by end-target chemoattractants, these cells will only rarely turn toward intermediary chemotactic agents, such as interleukin-8.17 With gradients of fMLP stimulation, the migration of WT and PTENα−/− neutrophils was dose dependent and bell shaped with the optimal chemotactic concentration of fMLP treatment. However, in contrast to WT neutrophils, PTENα−/− neutrophils did not exhibit dose-dependent migration curve with gradients of MIP-2 stimulation. On the other hand, when comparing the basal level of p-moesin in stationary WT and PTENα−/− marrow cells, PTENα−/− cells show a small increase in p-moesin (Figure 5E, lanes 1-3 vs. lanes 4-6). Neutrophils are not responsive to chemoattractants unless the “signal” is strong and sufficiently stable37 ; this seems to be due to the fact that PTENα−/− neutrophils have a higher threshold for activation and, therefore, are much less sensitive to intermediary chemoattractants.

PTEN is an antagonist of PI3K and binds to the cell membrane with its N-terminal lipid-binding motif and maintains low basal levels of PIP3.38,39 Lack of PTEN increases basal PIP3 levels, resulting in sustained growth of cells that leads to tumor development and enhanced cell migration.40,41 PTENα shares an entire functional domain with canonical PTEN. However, the extended N-terminal region found exclusively in PTENα may act to establish a favorable intracellular distribution for the protein or contribute to binding of particular proteins, such as moesin. The uniqueness of its cellular localization and the molecules with which PTENα associates are the bases for the distinctive functions observed in its cellular biology. Based on the findings in our study, we consider PTENα to be a positive regulator of neutrophil recruitment. If this model that we propose allows attenuation of tumor cell motility without interference with tumor growth, we could find a way to effectively inhibit tumor metastases, the major cause of cancer mortality. Previously reported conditional PTEN-knockout mice were generated through deletion of the fifth exon of the mouse PTEN gene, which, has, in fact, destroyed the whole PTEN family.17,42 Therefore, the phenotypes of PTEN−/− neutrophils reflect the combinational consequence of loss of the PTEN family members. Therefore, we propose that PTEN and PTENα are both important regulators of neutrophil chemotaxis in different mechanisms. PTEN determines the direction of migration, whereas PTENα determines the occurrence of movement.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank L. Liang and Y. Yu for protein purification, H. Liang for generating the PTENα-deficient HeLa cell line, X. Zhao for mass spectrometry analysis, and J. Feng, H. Qi, P. Wang, and J. Yang for technical assistance and critical suggestions.

This study was supported by grants from the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2016YFA0500302), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81430056, 31420103905, 81874235, and 81621063), the Beijing Natural Science Foundation (7161007), and the Lam Chung Nin Foundation for Systems Biomedicine (Y.Y.). The sterilizing equipment was supported by the Peking-Tsinghua Center for Life Sciences through public funds.

Authorship

Contribution: Y.L. designed and performed the experiments, analyzed data, and contributed to the writing of the manuscript; Yuan Jin performed some experiments and analyzed data; B.L. and D.L. performed some assays; M.Z. established the PTENα-knockout mouse model and Yan Jin helped with some experiments; M.A.M. revised the manuscript; and Y.Y. designed the study and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Yuxin Yin, Institute of Systems Biomedicine, School of Basic Medical Sciences, Peking University Health Science Center, 38 Xueyuan Rd, Haidian, Beijing 100191, China; e-mail: yinyuxin@bjmu.edu.cn.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Y.L. and Yuan Jin contributed equally to this work.