Key Points

In inflammation, migrating platelets become procoagulant to recruit the coagulation cascade and prevent pulmonary inflammatory bleeding.

Mechanosensitive GPIIBIIIA/Gα13 and GPVI signaling initiate CypD- and TMEM16F-dependent procoagulant activation of migrating platelets.

Abstract

Impairment of vascular integrity is a hallmark of inflammatory diseases. We recently reported that single immune-responsive platelets migrate and reposition themselves to sites of vascular injury to prevent bleeding. However, it remains unclear how single platelets preserve vascular integrity once encountering endothelial breaches. Here we demonstrate by intravital microscopy combined with genetic mouse models that procoagulant activation (PA) of single platelets and subsequent recruitment of the coagulation cascade are crucial for the prevention of inflammatory bleeding. Using a novel lactadherin-based compound, we detect phosphatidylserine (PS)-positive procoagulant platelets in the inflamed vasculature. We identify exposed collagen as the central trigger arresting platelets and initiating subsequent PA in a CypD- and TMEM16F-dependent manner both in vivo and in vitro. Platelet PA promotes binding of the prothrombinase complex to the platelet membrane, greatly enhancing thrombin activity and resulting in fibrin formation. PA of migrating platelets is initiated by costimulation via integrin αIIbβ3 (GPIIBIIIA)/Gα13-mediated outside-in signaling and glycoprotein VI signaling, leading to an above-threshold intracellular calcium release. This effectively targets the coagulation cascade to breaches of vascular integrity identified by patrolling platelets. Platelet-specific genetic loss of either CypD or TMEM16F as well as combined blockade of platelet GPIIBIIIA and glycoprotein VI reduce platelet PA in vivo and aggravate pulmonary inflammatory hemorrhage. Our findings illustrate a novel role of procoagulant platelets in the prevention of inflammatory bleeding and provide evidence that PA of patrolling platelet sentinels effectively targets and confines activation of coagulation to breaches of vascular integrity.

Introduction

Platelets, the second most abundant cell type in peripheral blood, preserve integrity of the injured vessel wall by forming hemostatic clots but also contribute to occlusive thrombus formation, causing ischemia and organ damage.1 Evidence has emerged that platelets are important beyond classical thrombosis and hemostasis and are uniquely positioned at the nexus of the vascular immune response.2-4 Platelets exert a plethora of important functions in inflammatory conditions, including the recruitment and activation of blood leukocytes into inflamed tissue,5-7 the scavenging and killing of microorganisms to prevent pathogen spreading,8-10 and antigen presentation to adaptive immune cells.11-13 Upon systemic dysregulation of the inflammatory response, platelet response and activating potential may, however, be detrimental to the host. Recent work has established platelets as prothrombotic and proinflammatory drivers of COVID-19, promoting disseminated clot formation through degranulation as well as neutrophil recruitment, hyperactivation, and neutrophil extracellular trap formation in severely affected patients.14-16 Interestingly, platelets recruited in inflammation use receptors, pathways, and effector functions that are at least in part distinct from those operating during classical thrombosis and hemostasis, underlining the importance of understanding these processes in greater detail.10

One hallmark of inflammation is increased vessel permeability and predisposition for microbleeds. Inflammatory bleeding occurs in tissues that possess a vast network of microcirculation, such as the skin, gastrointestinal mucosa, and lung,17 and most frequently affects critically ill patients who require intensive care treatment.18-20 Interestingly, inflammatory bleeding is mainly attributed to neutrophil transmigration through inflamed endothelium, subsequent generation of microvascular defects, and ensuing leakage of plasma contents and red blood cells (RBCs).17,21-24 Recently, we showed that immune-responsive platelets use cytoskeletal protrusions to sense and migrate along adhesive gradients.8 Platelets use their migratory capacity to reposition themselves to sites of vascular injury and leukocyte diapedesis, where they prevent neutrophil-induced microbleeds and bacterial dissemination alike.8 We provided evidence that loss of the ability to migrate aggravated both pulmonary and microvascular hemorrhage in models of lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced inflammation. However, the mechanisms by which single platelets plug the endothelial holes left behind by transmigrating neutrophils remain insufficiently understood.17 Studies have revealed considerable heterogeneity as well as redundancy in platelet receptors necessary to prevent inflammatory bleeding, with variety depending on both injury type and vascular bed.22,25-28 Under specific inflammatory conditions, platelet secretion and release of angiopoetin-1 can enhance local vascular integrity.27,29 However, the importance of plasmatic coagulation factors and the mechanisms that aid platelets in inflammatory hemostasis remain elusive.

Here, we show that blockade of plasmatic coagulation through factor II or X inhibition aggravates alveolar inflammatory bleeding. In the inflamed mesenteric vasculature, we detect fibrin(ogen)- and phosphatidylserine (PS)-positive platelets, a hallmark of platelet procoagulant activation (PA). These procoagulant platelets, which we visualize using a novel, highly sensitive PS-binding agent,30 bind clotting factors to locally build up microthrombi that prevent inflammatory bleeding. Genetic ablation of procoagulant platelet activation by targeting mitochondrial cyclophilin D (CypD) or membrane scramblase TMEM16F exacerbates inflammatory hemorrhage in the lung without affecting leukocyte transmigration and, specifically, neutrophil recruitment. We show that encounter of subendothelial collagen triggers arrest of migrating platelets and initiates a procoagulant response both in vitro and in vivo. This effect involves costimulation via integrin αIIbβ3 (GPIIBIIIA)/Gα13-mediated outside-in signaling and glycoprotein VI (GPVI) signaling, leading to an above-threshold intracellular calcium release. Targeting Gα13 and blocking GPVI or GPVI-associated downstream kinases in migrating platelets reduce platelet calcium peaks and PA. Finally, we confirm that combined pharmacological targeting of GPIIBIIIA and GPVI reduces platelet PA in vivo and exacerbates alveolar hemorrhage.

Methods

Detailed methodology is provided in the supplemental Data (available on the Blood Web site).

Generation of fibrin(ogen), albumin, and collagen surfaces

Custom-made chambers for coating with fibrin(ogen), albumin, and collagen were generated as previously described.8,9 In brief, coverslips (no. 1.5, D263T; Nexterion) were washed with 20% HNO3, rinsed with clean H2O for 1 hour each, subsequently air-dried and silanized with HMDS (Sigma) by spin coating for 30 seconds at 80 revolutions/sec. Ibidi sticky slide plastic channels (VI0.4, #80608) were subsequently attached to the silanized coverslip. Coverslips were then coated with 37.5 µg/mL AF-conjugated or unconjugated fibrinogen, 0.2% human serum albumin, and/or Horm collagen I (25 µg/mL) solved in modified Tyrode’s buffer (pH 7.2) for 15 minutes at room temperature. Fibrin surfaces were generated by addition of thrombin (1 U/mL), calcium (1 mM), and platelet-poor plasma. For some experiments, commercial flow chambers were coated with fibrinogen, collagen I, or a mixture without previous washing steps (Ibidi VI0.4 ibitreat slides, #80606).

Acute lung injury model

Subacute lung injury models were performed as described previously.8 In brief, mice were anesthetized, and 20 µg of Escherichia coli-derived LPS (O111:B4; Sigma) was applied intranasally. Anesthesia was antagonized immediately. In some experiments, mice received anticoagulants or platelet inhibitors by intravenous or subcutaneous injection: GPIIBIIIA inhibitor tirofiban (0.5 mg/kg body weight [BW]), factor Xa inhibitors rivaroxaban (3 mg/kg BW), and enoxaparin (10 mg/kg BW subcutaneously) or factor IIa inhibitor argatroban (5 mg/kg BW). For compounds with a short half-life, injections were repeated 4 and 8 hours after LPS application. Twenty-four hours after LPS treatment, mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation. Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid was collected by intratracheal flushing with 2 × 1 mL 1% BSA containing 2 mM EDTA. Subsequently, aliquots of BAL fluids (BALF) were stained with antibodies and analyzed by flow cytometry or sonicated to assess hemoglobin content by fluorescence absorption using a Tecan Infinite F200 plate reader (405 nm). Buffer-only containing wells were used to normalize samples against background absorbance. BALF was only included in the analysis if at least half of the applied volume was recovered (>1 mL). In some animals, instead collecting BALF, lungs and abdominal organs were surgically removed, fixated in 4% PFA for 1 hour, dehydrated in 30% sucrose overnight, and cryoembedded. Histopathological staining and analyses are described in the supplemental Data.

Mesentery live imaging

Animals were injected with 1 mg/kg BW of LPS intraperitoneally. After 2 hours, mice were anesthetized, and antibodies against Gp1b on platelets (X488 or X649, emfret, 20 µg) or Ly6G on neutrophils (Ly6G, clone 1A8, 4 µg; Biolegend) as well as Annexin V-AF649 or Annexin V-FITC (50-80 µL corresponding to approximately 10-15 µg [batch-dependent concentration], Biolegend) or C1 multimer-AF649 (15 µL corresponding to 7 µg; mC1 multimers are commercially available through Biolegend as Apotracker Tetra reagents) were injected via the tail vein. In some experiments, 80 µg of fibrinogen-AF546 conjugate was injected intravenously. After ensuring adequate analgesia, laparotomy was performed, and the bowel was exteriorized and placed on a prewarmed glass cover slip. Mesenteric vessels were subsequently exposed on the coverslip. Tissue paper prewet with 37°C warm phosphate-buffered saline was used to fixate the exposed bowel in place. Imaging was performed using a Zeiss LSM 880 confocal microscope in either AiryScan Fast mode or AiryScan Superresolution mode.

Results

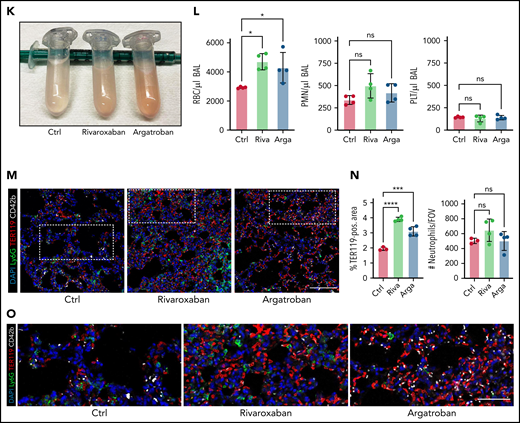

Both thrombocytopenia and anticoagulation aggravate inflammatory bleeding

Platelets are crucial for preventing leukocyte diapedesis-inflicted microbleeding in inflammation. Pulmonary LPS challenge induced alveolar neutrophil recruitment and subsequent hemorrhage, resulting in a proinflammatory cytokine signature in the lung (supplemental Figure 1A-D). Confirming previous findings,24 antibody-induced thrombocytopenia aggravated pulmonary bleeding in our model of LPS-induced lung injury (Figure 1A-B). Alveolar hemorrhage in thrombocytopenic animals was severe enough to cause anemia in some animals (Figure 1C) but did not cause alterations in pulmonary leukocyte recruitment (Figure 1C-E; supplemental Figure 1E).

Both thrombocytopenia and anticoagulation aggravate inflammatory bleeding. (A) Experimental scheme of subacute lung injury model with or without antibody-mediated platelet depletion. The red arrow indicates antibody administration; the blue arrow indicates intranasal LPS administration. (B) Representative macroscopic images of lungs from control (C301) and thrombocytopenic animals (R300 treatment) 24 hours after LPS challenge. (C) Flow cytometric analysis of peripheral blood (platelet and RBC count) and BALF (RBC and leukocyte count/µL BALF). Student’s t test, two-tailed, unpaired. (D) Representative micrographs of immunofluorescence stainings of alveolar hemorrhage in control (C301) and thrombocytopenic animals (R300). Bar represents 100 µm. (E) Magnified excerpts of representative micrographs, corresponding to white rectangles in Figure 1D. Bar represents 50 µm. (F) Representative images of immunofluorescence stainings of lungs from control (Ctrl) or septic animals (E. coli–derived LPS 1 mg/kg BW intraperitoneally). Bar represents 100 µm (left and mid panel) and 20 µm (right panel). White arrowheads indicate fibrin(ogen)-positive platelets. Red: anti-PS antibody (Merck). (G) Quantification of fibrinogen deposition and overlap of fibrinogen/platelet positive areas. n = 3 to 4 mice per group. Student’s t test, two-tailed, unpaired. (H) Quantification of fibrinogen deposition in lungs from septic control (C301) and platelet-depleted animals (R300) per field of view (FOV). n = 4 mice per group. Student’s t test, two-tailed, unpaired. (I) Representative micrographs of control (C301) and platelet-depleted mice (R300), referring to (H). Bar represents 200 µm (left and right panels). Magnified excerpt (middle; bar represents 20 µm) corresponds to the white rectangle of the left panel. Red: anti-PS antibody (Merck). (J) Experimental scheme of (sub)acute lung injury. Bl6 mice were treated with 20 µg of LPS intranasally (blue arrow) and intravenously injected with vehicle or rivaroxaban (3 mg/kg BW) right before and 8 hours after challenge or argatroban (5 mg/kg BW) right before and 4 and 8 hours after challenge; rivaroxaban-treated animals received vehicle injections at 4 hours after challenge (red arrows indicate timing of intravenous injections). (K) Representative macroscopic image of BALF derived from 1 simultaneously performed set of experimental groups, collected in 2 mL Eppendorf tubes. The right tube corresponds to the maximum bleeding observed in argatroban-treated animals. (L) Flow-cytometric assessment of BALF (RBC, polymorphonuclear, and PLT counts/µL BALF). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Holm-Šídák's multiple comparisons test compared with control groups. (M) Representative images of immunofluorescence stainings of lung slices from different experimental groups. Bar represents 100 µm. (N) Quantification of alveolar hemorrhage (TER119+ area) and neutrophil recruitment. n = 3 to 4 mice/group. One-way ANOVA with Holm-Šídák's multiple comparisons test compared with control groups. (O) Magnified excerpts of representative micrographs, corresponding to white rectangles in Figure 1M. Bar represents 50 µm.

Both thrombocytopenia and anticoagulation aggravate inflammatory bleeding. (A) Experimental scheme of subacute lung injury model with or without antibody-mediated platelet depletion. The red arrow indicates antibody administration; the blue arrow indicates intranasal LPS administration. (B) Representative macroscopic images of lungs from control (C301) and thrombocytopenic animals (R300 treatment) 24 hours after LPS challenge. (C) Flow cytometric analysis of peripheral blood (platelet and RBC count) and BALF (RBC and leukocyte count/µL BALF). Student’s t test, two-tailed, unpaired. (D) Representative micrographs of immunofluorescence stainings of alveolar hemorrhage in control (C301) and thrombocytopenic animals (R300). Bar represents 100 µm. (E) Magnified excerpts of representative micrographs, corresponding to white rectangles in Figure 1D. Bar represents 50 µm. (F) Representative images of immunofluorescence stainings of lungs from control (Ctrl) or septic animals (E. coli–derived LPS 1 mg/kg BW intraperitoneally). Bar represents 100 µm (left and mid panel) and 20 µm (right panel). White arrowheads indicate fibrin(ogen)-positive platelets. Red: anti-PS antibody (Merck). (G) Quantification of fibrinogen deposition and overlap of fibrinogen/platelet positive areas. n = 3 to 4 mice per group. Student’s t test, two-tailed, unpaired. (H) Quantification of fibrinogen deposition in lungs from septic control (C301) and platelet-depleted animals (R300) per field of view (FOV). n = 4 mice per group. Student’s t test, two-tailed, unpaired. (I) Representative micrographs of control (C301) and platelet-depleted mice (R300), referring to (H). Bar represents 200 µm (left and right panels). Magnified excerpt (middle; bar represents 20 µm) corresponds to the white rectangle of the left panel. Red: anti-PS antibody (Merck). (J) Experimental scheme of (sub)acute lung injury. Bl6 mice were treated with 20 µg of LPS intranasally (blue arrow) and intravenously injected with vehicle or rivaroxaban (3 mg/kg BW) right before and 8 hours after challenge or argatroban (5 mg/kg BW) right before and 4 and 8 hours after challenge; rivaroxaban-treated animals received vehicle injections at 4 hours after challenge (red arrows indicate timing of intravenous injections). (K) Representative macroscopic image of BALF derived from 1 simultaneously performed set of experimental groups, collected in 2 mL Eppendorf tubes. The right tube corresponds to the maximum bleeding observed in argatroban-treated animals. (L) Flow-cytometric assessment of BALF (RBC, polymorphonuclear, and PLT counts/µL BALF). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Holm-Šídák's multiple comparisons test compared with control groups. (M) Representative images of immunofluorescence stainings of lung slices from different experimental groups. Bar represents 100 µm. (N) Quantification of alveolar hemorrhage (TER119+ area) and neutrophil recruitment. n = 3 to 4 mice/group. One-way ANOVA with Holm-Šídák's multiple comparisons test compared with control groups. (O) Magnified excerpts of representative micrographs, corresponding to white rectangles in Figure 1M. Bar represents 50 µm.

We and others have shown that single platelets promote vascular homeostasis in the setting of inflammation, ensuring the effective sealing of transendothelial migration sites.8,17,21,22,31 Recently, we demonstrated that migration and haptotaxis are essential for vasculoprotective effects of single platelets in microvascular inflammation of both the lung and skeletal muscles.8 To understand how platelets prevent inflammatory bleeding once positioned at extravasation sites, we studied platelets in the inflamed lung using high-resolution immunofluorescence-based imaging of lung slices (Figure 1F). Recruited platelets stained positive for fibrin(ogen), with evidence of fibrin fibers associated with platelets (Figure 1F). Accordingly, platelet recruitment and platelet fibrin(ogen) association were enhanced under inflammatory conditions (Figure 1F-G). Fibrin(ogen) deposition in the inflamed lung was markedly reduced in platelet-depleted septic animals (Figure 1H-I), suggesting close interplay of platelets and coagulation.

To assess whether plasmatic coagulation cascades and downstream fibrin formation contribute to prevention of inflammatory bleeding, we treated Bl6 mice with the clinically approved factor IIa or factor Xa antagonists argatroban, enoxaparin, or rivaroxaban, respectively, and subsequently challenged them with LPS intranasally (Figure 1J; supplemental Figure 1F-J). Treatment with both factor IIa and Xa inhibitors aggravated alveolar hemorrhage, as assessed by flow cytometry of bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid (Figure 1K-L; supplemental Figure 1F-I). Notably, peripheral platelet and leukocyte counts as well as platelet-neutrophil aggregate (PNA) formation were not affected by treatment (supplemental Figure 1J). Histopathological analysis of LPS-challenged lungs confirmed a significant increase in alveolar hemorrhage in mice that had received argatroban, enoxaparin, or rivaroxaban (Figure 1M-O; supplemental Figure 1K-M). In contrast, alveolar leukocyte recruitment did not differ between treatment groups, suggesting that anticoagulation does not interfere with transendothelial migration and that the observed effect was not due to increased neutrophil diapedesis (Figure 1L-O; supplemental Figure 1K-M). Treatment of isolated platelets with either inhibitor did not affect their ability to migrate in vitro, emphasizing that the observed increase in bleeding was not due to loss of migratory capacity (supplemental Figure 1N-O). These findings suggest an essential, possibly platelet-dependent role for plasmatic coagulation in preventing inflammatory bleeding in the lung.

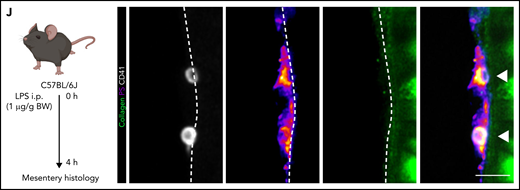

Inflammation induces single procoagulant platelets that form fibrin(ogen)-positive microthrombi in vivo

Platelets promote coagulation by turning procoagulant through exposure of PS and by binding of prothrombinase complex on their membranes, boosting local thrombin generation.32,33 Procoagulant platelet activation occurs upon dual stimulation with strong agonists and can be augmented by mechanical stress such as locally increased shear,32-36 but the impact of systemic factors and inflammation are unknown. We have recently described the generation of a novel, lactadherin-based compound for the detection of PS, the key marker for procoagulant platelets.30 Here, we used biotinylated murine lactadherin C1 domains multimerized using Streptavidin (C1) and found that this compound sensitively and accurately detected PS+ platelets at lower concentrations than annexin V (supplemental Figure 2A-E) in vitro.30 To investigate whether local procoagulant platelet activation occurs under inflammatory conditions in vivo, we performed 4-dimensional live imaging of mesenteric postcapillary venules after intraperitoneal LPS injection (Figure 2A). Intravenous injection of C1 or Annexin V revealed hardly any PS+ platelets in control mice, but readily detected PS+ platelet balloons bound to the inflamed vessel wall of mesenteric venules in septic animals (Figure 2B-C; supplemental Video 1; supplemental Figure 2F).

Procoagulant platelets are induced by inflammation in vivo. (A) Experimental scheme of peritoneal sepsis and mesenteric live imaging. (B) Representative images derived from 4-dimensional (4D) live microscopy of mesentery venules. Dotted lines indicate vessel walls. Bar represents 5 µm. PS staining agent: mC1. (C) Quantification of procoagulant platelets in mesenteric venules of sham- or LPS-treated Bl6 mice. Student’s t test, two-tailed, unpaired. (D) Analysis of motility patterns and quantification of procoagulant platelet content in different motility subgroups in sham- or LPS-treated animals. Student’s t test, two-tailed, unpaired. (E) Example image derived from 4D live microscopy of mesentery venules. Yellow signal indicates overlap between phosphatidylserine (PS, mC1) and fibrinogen. Dotted lines indicate vessel walls. Bar represents 10 µm. (F) Quantification of fibrinogen-binding behavior of non-procoagulant (PS-, blue) and procoagulant platelets (PS+, red) from live imaging data (n = 4 LPS-treated mice; n = 2-3 videos per mouse). Data are shown as % of all platelets of the respective subset. One-way ANOVA. (G-H) Example image derived from 4D live microscopy of mesentery venules revealing PS+, fibrinogen-binding adherent platelets. Dotted lines indicate vessel walls. The red line corresponds to the plot profiles for expression of fibrinogen, PS and CD42b (X488) as shown in (H). PS staining agent: mC1. Bar represents 20 µm. (I) Absolute quantification of the area of Fbg, Fbg/CD42b, and Fbg/CD42b/PS overlap in sham- or LPS-injected mice (n = 3-4 mice per condition; n = 2-3 videos per mouse). Student’s t test, two-tailed, unpaired. (J) Experimental scheme and representative immunofluorescence images of mesenteric venules after 4 hours of LPS intraperitoneal injection. White arrowheads indicate procoagulant platelets (CD41/GPIIBIIIA-positive, PS-positive) in close proximity to antibody-stained collagen fibers (green). Bar represents 5 µm. PS staining agent: anti-PS antibody. Refer to supplemental Figure 2N for overview images.

Procoagulant platelets are induced by inflammation in vivo. (A) Experimental scheme of peritoneal sepsis and mesenteric live imaging. (B) Representative images derived from 4-dimensional (4D) live microscopy of mesentery venules. Dotted lines indicate vessel walls. Bar represents 5 µm. PS staining agent: mC1. (C) Quantification of procoagulant platelets in mesenteric venules of sham- or LPS-treated Bl6 mice. Student’s t test, two-tailed, unpaired. (D) Analysis of motility patterns and quantification of procoagulant platelet content in different motility subgroups in sham- or LPS-treated animals. Student’s t test, two-tailed, unpaired. (E) Example image derived from 4D live microscopy of mesentery venules. Yellow signal indicates overlap between phosphatidylserine (PS, mC1) and fibrinogen. Dotted lines indicate vessel walls. Bar represents 10 µm. (F) Quantification of fibrinogen-binding behavior of non-procoagulant (PS-, blue) and procoagulant platelets (PS+, red) from live imaging data (n = 4 LPS-treated mice; n = 2-3 videos per mouse). Data are shown as % of all platelets of the respective subset. One-way ANOVA. (G-H) Example image derived from 4D live microscopy of mesentery venules revealing PS+, fibrinogen-binding adherent platelets. Dotted lines indicate vessel walls. The red line corresponds to the plot profiles for expression of fibrinogen, PS and CD42b (X488) as shown in (H). PS staining agent: mC1. Bar represents 20 µm. (I) Absolute quantification of the area of Fbg, Fbg/CD42b, and Fbg/CD42b/PS overlap in sham- or LPS-injected mice (n = 3-4 mice per condition; n = 2-3 videos per mouse). Student’s t test, two-tailed, unpaired. (J) Experimental scheme and representative immunofluorescence images of mesenteric venules after 4 hours of LPS intraperitoneal injection. White arrowheads indicate procoagulant platelets (CD41/GPIIBIIIA-positive, PS-positive) in close proximity to antibody-stained collagen fibers (green). Bar represents 5 µm. PS staining agent: anti-PS antibody. Refer to supplemental Figure 2N for overview images.

Analysis of motility patterns of platelets in sham- vs LPS-treated animals revealed significant increases in adhering, migrating, and, specifically, procoagulant platelets (Figure 2C-D). Migrating platelets remained stationary once they turned procoagulant (Figure 2D; supplemental Video 1; supplemental Figure 2F). Most adherent, stationary procoagulant platelets were found to be fibrin(ogen)-positive (Figure 2E-F). In line, inflammation-associated deposition of fibrin(ogen) along the endothelial lumen was pronounced in regions were procoagulant platelets were binding (Figure 2G-I). Confirming these observations, most fibrin(ogen)-positive platelets in the inflamed lung were found to be procoagulant (supplemental Figure 2G).

Previous studies have established that the peritoneum is not a major site of inflammatory bleeding, even though thrombocytopenia does increase vascular permeability in peritonitis.22,37 In thrombocytopenic animals, we found that LPS-induced peritonitis was associated with abdominal microbleeding (supplemental Figure 2H-M). Notably, thrombocytopenia also reduced intraperitoneal neutrophil recruitment, possibly explaining the relatively modest bleeding phenotype in platelet-depleted mice, which was not significantly affected by neutrophil depletion (supplemental Figure 2H-K).22

The factors that induce platelet PA in inflammation are unknown. When staining mesenteric vessels for procoagulant platelets, we frequently found single PS+ and fibrin(ogen)+ procoagulant platelets in close association with the collagen-positive subendothelial matrix in septic mice (Figure 2J; supplemental Figure 2N). This was in part dependent on immune cell recruitment because neutrophil-depleted LPS-treated animals exhibited reduced intravascular fibrin(ogen) depositions (supplemental Figure 2M). We therefore hypothesized that exposure of subendothelial matrix proteins upon transendothelial leukocyte migration and inflammation-mediated vascular injury would lead to procoagulant activation and arrest of migrating platelets.

Migrating platelets turn procoagulant upon sensing collagen

To reconstruct the inflammatory microenvironment in vitro, we designed a hybrid substrate consisting of albumin, fibrinogen, and collagen I fibers, mimicking exposure to extracellular matrix proteins observed in severe inflammatory endotheliopathy (Figure 3A).17 When encountering collagen fibers, the characteristic half moon–like shape of migrating platelets was rapidly replaced by a balloon-like morphology with extensive microvesicle formation and PS exposure (Figure 3B), known hallmarks of procoagulant platelets.32,33 PA of migrating platelets was specific to sensing collagen fibers because migrating platelets that did not encounter collagen fibers barely adopted a procoagulant phenotype (Figure 3C-E). In line, actin-related protein 2/3 complex subunit 2 (Arpc2)-deficient platelets, which are unable to migrate,8,9 showed significantly lower PA levels compared with platelets from Cre-negative littermates when adhering to the hybrid substrate. However, they retained their procoagulant potential when exposed to purified collagen fibers or soluble agonists (Figure 3F; supplemental Figure 3A-C). In addition to morphological changes, relative and absolute velocity as well as migration distance of human platelets that had become procoagulant decreased significantly, essentially arresting them at the site of collagen encounter (Figure 3G-H). Exposure of mouse platelets to collagen fibers in solution did not provoke procoagulant activity or fibrin(ogen) binding, underlining a role for mechanosensing (supplemental Figure 3D-F). In contrast to published assays using platelets in suspension, procoagulant function of migrating platelets was independent of the presence of soluble agonists in our assay.38,39 Clinically used antiplatelet drugs such as terutroban, cangrelor, and vorapaxar, which inhibit thromboxane, ADP receptor P2Y12, and protease-activated receptor 1 (PAR1), respectively, did not affect migratory capacity or platelet PA in vitro (supplemental Figure 3G). Likewise, inhibition of PAR4, previously shown to affect platelet PA during human thrombus formation,40 or simultaneous inhibition of PAR1 and PAR4 had no effect (supplemental Figure 3H). Given the proximity of procoagulant platelets and both intravascular and pulmonary fibrin(ogen) observed in vivo, we investigated the contribution of PA-associated secretion of fibrin(ogen)-containing α-granules. In vitro, we did not observe substantial endogenous fibrin(ogen) secretion around migrating or procoagulant platelets, suggesting that deposited fibrin(ogen) originates from other sources (supplemental Figure 3I-J).

Migrating platelets turn procoagulant upon sensing collagen. (A) Experimental setup of hybrid matrices mimicking the inflamed endothelium, with black lines corresponding to collagen fibers. (B) Representative confocal micrograph of human migrating platelets (CD41, white) with or without contact to collagen fibers. White arrowheads indicate procoagulant platelet formation with PS positivity (mC1) and secretion of microvesicles after sensing collagen; dashed white lines indicate collagen fibers. Bar represents 10 µm. (C-E) Representative micrographs of human platelets migrating on an albumin/fibrinogen matrix (upper panel) or a hybrid matrix containing albumin, fibrinogen, and collagen I (lower panel, dashed white lines). Quantification of procoagulant platelet activation on the respective matrix of freely migrating vs collagen-sensing platelets after 45 minutes (fixed time point) or over a period of 1 hour (time course experiment). PS staining agent: mC1. Bar represents 10 µm. Student’s t test, two-tailed, unpaired; one-way ANOVA with Holm-Šídák's multiple comparisons test compared with t = 0 minutes for time course experiment (right panel, E). (F) Quantification of procoagulant platelet activation and migrating platelets of PF4cre-Arpc2fl/fl Cre-positive mice and Cre-negative littermates. Student’s t test, two-tailed, unpaired. (G) Relative velocity plots of tracked human platelets from live-imaging data. Absolute velocities were normalized to peak velocity to allow for interplatelet comparisons. Blue lines indicate the onset of procoagulant platelet activation. (H) Quantification of absolute velocity and Euclidean distance of migrating human platelets from live-imaging data. Individual dots represent n = 3 individuals per experimental group, with n > 30 individual platelets analyzed per n. Student’s t test, two-tailed, unpaired.

Migrating platelets turn procoagulant upon sensing collagen. (A) Experimental setup of hybrid matrices mimicking the inflamed endothelium, with black lines corresponding to collagen fibers. (B) Representative confocal micrograph of human migrating platelets (CD41, white) with or without contact to collagen fibers. White arrowheads indicate procoagulant platelet formation with PS positivity (mC1) and secretion of microvesicles after sensing collagen; dashed white lines indicate collagen fibers. Bar represents 10 µm. (C-E) Representative micrographs of human platelets migrating on an albumin/fibrinogen matrix (upper panel) or a hybrid matrix containing albumin, fibrinogen, and collagen I (lower panel, dashed white lines). Quantification of procoagulant platelet activation on the respective matrix of freely migrating vs collagen-sensing platelets after 45 minutes (fixed time point) or over a period of 1 hour (time course experiment). PS staining agent: mC1. Bar represents 10 µm. Student’s t test, two-tailed, unpaired; one-way ANOVA with Holm-Šídák's multiple comparisons test compared with t = 0 minutes for time course experiment (right panel, E). (F) Quantification of procoagulant platelet activation and migrating platelets of PF4cre-Arpc2fl/fl Cre-positive mice and Cre-negative littermates. Student’s t test, two-tailed, unpaired. (G) Relative velocity plots of tracked human platelets from live-imaging data. Absolute velocities were normalized to peak velocity to allow for interplatelet comparisons. Blue lines indicate the onset of procoagulant platelet activation. (H) Quantification of absolute velocity and Euclidean distance of migrating human platelets from live-imaging data. Individual dots represent n = 3 individuals per experimental group, with n > 30 individual platelets analyzed per n. Student’s t test, two-tailed, unpaired.

Cyclophilin D (CypD) and transmembrane protein 16F (TMEM16F) are central drivers of platelet PA. While CypD promotes mitochondrial depolarization and supramaximal intracellular calcium bursts, TMEM16F mediates platelet PS exposure.33,35,38,41-46 To genetically ablate procoagulant platelet activation, we generated transgenic mice with platelet- and megakaryocyte-specific knockouts of CypD (PF4cre-CypDfl/fl) and TMEM16F (PF4cre-TMEM16Ffl/fl). Animal weight, peripheral platelet, RBCs, and leukocyte counts at baseline as well as expression of several key platelet receptors did not differ between Cre-positive and negative animals of either mouse line (supplemental Figure 4A-F). Tail bleeding experiments revealed no significant differences in bleeding time in either PF4cre-CypDfl/fl or -TMEM16Ffl/fl animals, with TMEM16F-deficient mice exhibiting a nonsignificant trend toward longer time to hemostasis (supplemental Figure 4G-H). Arterial thrombus formation was impaired in both mouse lines when we injured the carotid endothelium using ferric chloride, confirming previous observations (supplemental Figure 4I-L).39,47

Combined exposure of isolated CypD- or TMEM16F-knockout platelets to strong agonists such as PAR agonist thrombin and GPVI agonist convulxin yielded significantly lower PS expression levels, consistent with reduced procoagulant potential in suspension for both mouse lines (Figure 4A-B; supplemental Figure 4C,F). Despite reduced PA, both CypD- and TMEM16F-deficient platelets retained migratory capacity (Figure 4C-D). As reported earlier,47 CypD−/− and TMEM16F−/− platelets exerted intact degranulation and integrin activation, as measured by P-selectin and activated GPIIBIIIA expression, respectively (supplemental Figure 4B-C,E-F). When encountering collagen fibers, migrating TMEM16F knockout platelets exhibited a characteristic morphological phenotype with formation of string-like filopodia but were unable to form PS+ balloons (Figure 4D; supplemental Figure 4M-N). In line with previous findings,42 TMEM16F−/− platelets were incapable of releasing microvesicles (supplemental Figure 4M-N).

Genetic or pharmacological targeting of CypD and TMEM16F reduces procoagulant platelet activation without impairing migratory capacity. (A-B) Representative scatter plots and analyses derived from flow cytometric measurements of stimulated platelets from CypD- (A) or TMEM16F-knockout mice (B) (n = 3-4 mice per group). PS staining agent: mC1. Platelets were stimulated with thrombin (0.1 U/L) and convulxin (0.1 µg/mL) for 30 minutes at room temperature. Student’s t test, two-tailed, unpaired. (C-D) Representative micrographs of isolated murine platelets from platelet-specific CypD- (C) or TMEM16F- (D) knockout mice migrating on an albumin/fibrinogen/collagen I hybrid matrix. Quantification of platelet procoagulant activity and cleared area (as a surrogate for migration length) depicted as SuperPlots, with individual circles indicating individual images and the error bars corresponding to the mean data of 6 images of n = 3 to 4 mice per Cre-positive or -negative group. White dashed lines indicate collagen fibers. White arrowheads indicate migrating platelets with collagen contact but without procoagulant activity. White stars indicate procoagulant platelets. Bar represents 25 (left panel) and 15 µm (right panel). PS staining agent: mC1. Student’s t test, two-tailed, unpaired. (E) Experimental scheme of migration assay on hybrid matrix with targeting of platelet PA-promoting pathways. (F-G) Quantification of procoagulant platelets and cleared area by murine (F) and human platelets (G) treated with inhibitors of CypD (cyclosporine A, CicA, 2 µM) or TMEM16F (niflumic acid [NFA] 10 µM). One-way ANOVA with Holm-Šídák's multiple comparisons test compared with control groups. (H) Representative images of migrating human platelets stained for CD41 and PS (mC1) and incubated with an internally quenched 5-FAM/QXL 520 FRET substrate indicating thrombin activity. White arrowhead indicates a procoagulant, thrombin-positive platelet. Bar represents 10 µm. See supplemental Figure 4R for detailed images. (I) Cell-based quantification of thrombin-positive cells/FOV and the fraction of thrombin-positive cells as percentage of procoagulant platelets. Per condition, >100 cells from at least n = 2 animals were analyzed. One-way ANOVA with Holm-Šídák's multiple comparisons test compared with control groups.

Genetic or pharmacological targeting of CypD and TMEM16F reduces procoagulant platelet activation without impairing migratory capacity. (A-B) Representative scatter plots and analyses derived from flow cytometric measurements of stimulated platelets from CypD- (A) or TMEM16F-knockout mice (B) (n = 3-4 mice per group). PS staining agent: mC1. Platelets were stimulated with thrombin (0.1 U/L) and convulxin (0.1 µg/mL) for 30 minutes at room temperature. Student’s t test, two-tailed, unpaired. (C-D) Representative micrographs of isolated murine platelets from platelet-specific CypD- (C) or TMEM16F- (D) knockout mice migrating on an albumin/fibrinogen/collagen I hybrid matrix. Quantification of platelet procoagulant activity and cleared area (as a surrogate for migration length) depicted as SuperPlots, with individual circles indicating individual images and the error bars corresponding to the mean data of 6 images of n = 3 to 4 mice per Cre-positive or -negative group. White dashed lines indicate collagen fibers. White arrowheads indicate migrating platelets with collagen contact but without procoagulant activity. White stars indicate procoagulant platelets. Bar represents 25 (left panel) and 15 µm (right panel). PS staining agent: mC1. Student’s t test, two-tailed, unpaired. (E) Experimental scheme of migration assay on hybrid matrix with targeting of platelet PA-promoting pathways. (F-G) Quantification of procoagulant platelets and cleared area by murine (F) and human platelets (G) treated with inhibitors of CypD (cyclosporine A, CicA, 2 µM) or TMEM16F (niflumic acid [NFA] 10 µM). One-way ANOVA with Holm-Šídák's multiple comparisons test compared with control groups. (H) Representative images of migrating human platelets stained for CD41 and PS (mC1) and incubated with an internally quenched 5-FAM/QXL 520 FRET substrate indicating thrombin activity. White arrowhead indicates a procoagulant, thrombin-positive platelet. Bar represents 10 µm. See supplemental Figure 4R for detailed images. (I) Cell-based quantification of thrombin-positive cells/FOV and the fraction of thrombin-positive cells as percentage of procoagulant platelets. Per condition, >100 cells from at least n = 2 animals were analyzed. One-way ANOVA with Holm-Šídák's multiple comparisons test compared with control groups.

Pharmacological inhibition of CypD and TMEM16F using cyclosporin A and niflumic acid, respectively, significantly reduced PA of migrating mouse platelets without affecting migratory capacity (Figure 4E-F). We reproduced this observation when we inhibited CypD and TMEM16F in human platelets (Figure 4G). PS+ platelets predominantly stained caspase-negative, pointing toward a procoagulant, not apoptotic phenotype (supplemental Figure 4O-P). However, we also observed single platelets positive for phosphatidylserine with signs of caspase activation, and treatment of migrating platelets with the pan-caspase inhibitor Q-VD-OPh reduced PA to some extent (supplemental Figure 4Q).32,38,48

To confirm that genetic ablation of either CypD or TMEM16F led not only to a decrease in platelet PA and PS exposure but also to a functional decline in procoagulant function, we incubated wild-type and knockout platelets with a fluorescent probe indicating thrombin turnover (Figure 4H). Loss of either protein led to decreased platelet PA and a significant decrease in thrombin turnover (Figure 4H-I; supplemental Figure 4R). We observed a reduced fraction of thrombin-positive procoagulant platelets specifically in procoagulant platelets derived from PF4cre-TMEM16Ffl/fl mice, indicating that the inability to flip PS to the outer membrane layer also functionally reduces binding of coagulation factors (Figure 4I; supplemental Figure 4R). In summary, we show that immune-responsive platelets become procoagulant independent of soluble agonist stimulation upon encountering collagen in vitro and the subendothelial matrix of inflamed vessels in vivo.

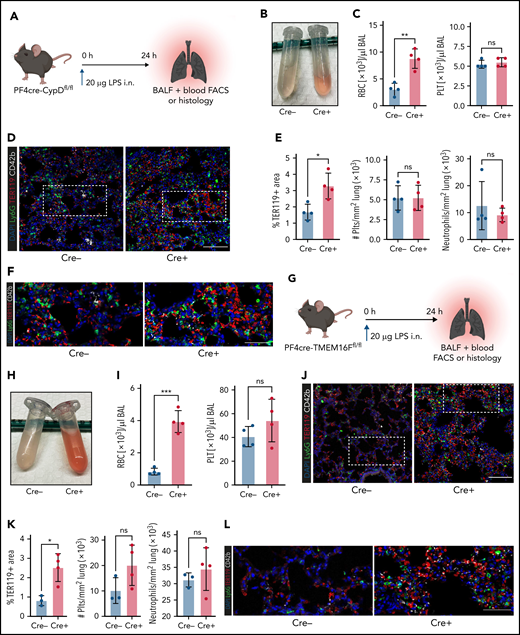

Genetic ablation of platelet PA aggravates inflammatory bleeding

Next, we hypothesized that platelets serve as motile sentinels targeting the coagulation cascade to sites of inflammatory injury, thereby preventing microbleeds. To study this, we performed acute lung injury experiments on both PF4cre-CypDfl/fl and PF4cre-TMEM16Ffl/fl mouse lines. Platelet-specific genetic ablation of CypD aggravated alveolar hemorrhage 24 hours after LPS exposure (Figure 5A-C). This increase in pulmonary bleeding was not due to blunt vascular trauma, as shown by the low counts of single, non–leukocyte-bound platelets in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (Figure 5C; supplemental Figure 5A-B). Neither peripheral platelet nor leukocyte counts were significantly altered after acute lung injury, excluding thrombocytopenia or leukocytosis as possible causes of increased pulmonary bleeding; the number of infiltrating neutrophils did not differ either (supplemental Figure 5A-B). Immunofluorescence stainings of LPS-challenged lungs confirmed a significant increase in alveolar hemorrhage in mice with CypD-deficient platelets, whereas neither pulmonary platelet nor neutrophil recruitment differed between genotypes (Figure 5D-F).

Genetic ablation of platelet PA aggravates inflammatory bleeding. (A) Experimental scheme for acute lung injury in platelet-specific CypD-knockout mice. (B) Representative image of BALF from platelet-specific CypD-knockout mice and Cre-negative littermates. (C) Flow cytometric analysis of RBC and platelet counts in BALF. Student’s t test, two-tailed, unpaired. (D) Representative micrograph of immunofluorescence-stained lung slices from CypD-knockout mice and Cre-negative control animals. Bar represents 100 µm. (E) Histological quantification of alveolar hemorrhage (TER119+ area) as well as pulmonary neutrophil and platelet recruitment. Student’s t test, two-tailed, unpaired. (F) Magnified excerpts of representative micrographs, corresponding to white rectangle in Figure 5D. Bar represents 50 µm. (G) Experimental scheme for acute lung injury in TMEM16F-knockout mice. (H) Representative image of BALF from platelet-specific TMEM16F-knockout mice and Cre-negative littermates. (I) Flow cytometric analysis of RBC and platelet counts in BALF. Student’s t test, two-tailed, unpaired. (J) Representative micrograph of immunofluorescence-stained lung slices from TMEM16F-knockout mice and Cre-negative littermates. Bar represents 100 µm. (K) Histopathological quantification of alveolar hemorrhage (TER119+ area) as well as pulmonary neutrophil and platelet recruitment. Student’s t test, two-tailed, unpaired. (L) Magnified excerpts of representative micrographs, corresponding to white rectangle in Figure 5J. Bar represents 50 µm.

Genetic ablation of platelet PA aggravates inflammatory bleeding. (A) Experimental scheme for acute lung injury in platelet-specific CypD-knockout mice. (B) Representative image of BALF from platelet-specific CypD-knockout mice and Cre-negative littermates. (C) Flow cytometric analysis of RBC and platelet counts in BALF. Student’s t test, two-tailed, unpaired. (D) Representative micrograph of immunofluorescence-stained lung slices from CypD-knockout mice and Cre-negative control animals. Bar represents 100 µm. (E) Histological quantification of alveolar hemorrhage (TER119+ area) as well as pulmonary neutrophil and platelet recruitment. Student’s t test, two-tailed, unpaired. (F) Magnified excerpts of representative micrographs, corresponding to white rectangle in Figure 5D. Bar represents 50 µm. (G) Experimental scheme for acute lung injury in TMEM16F-knockout mice. (H) Representative image of BALF from platelet-specific TMEM16F-knockout mice and Cre-negative littermates. (I) Flow cytometric analysis of RBC and platelet counts in BALF. Student’s t test, two-tailed, unpaired. (J) Representative micrograph of immunofluorescence-stained lung slices from TMEM16F-knockout mice and Cre-negative littermates. Bar represents 100 µm. (K) Histopathological quantification of alveolar hemorrhage (TER119+ area) as well as pulmonary neutrophil and platelet recruitment. Student’s t test, two-tailed, unpaired. (L) Magnified excerpts of representative micrographs, corresponding to white rectangle in Figure 5J. Bar represents 50 µm.

Pulmonary LPS exposure of PF4cre-TMEM16F−/− animals phenocopied the effects observed in CypD-deficient mice. Both flow cytometric and histological analysis of alveolar hemorrhage showed marked increases in pulmonary bleeding (Figure 5G-L). Free-floating platelets were hardly detected in BALF, whereas most infiltrating neutrophils were platelet-coated (Figure 5I; supplemental Figure 5C). In accordance with results derived from CypD-deficient mice, neither platelet and neutrophil recruitment to the lung nor peripheral platelet and leukocyte counts in platelet-specific TMEM16F-knockout animals revealed any differences 24 hours after LPS exposure (Figure 5I,K; supplemental Figure 5D). These data suggest that platelet PA is an important effector function of platelets in inflammation, aiding in the prevention of transmigration-associated pulmonary hemorrhage.

Impact of genetic targeting of PA pathways on platelet calcium oscillations

We next sought to elucidate cellular pathways triggering procoagulant function in inflammation. PA depends on the ability of the individual platelet to rapidly increase cytosolic calcium levels, with a recent study describing “supramaximal calcium bursts”44 within the range of 100 µM, exceeding normal intracellular levels by far. In migrating platelets, we observed rhythmic calcium oscillations throughout the course of migration on fibrinogen and albumin matrices (supplemental Figure 6A). When migrating platelets hit collagen fibers, instant intracellular calcium bursts occurred (Figure 6A-B; supplemental Video 2). These calcium bursts preceded both morphological changes (ballooning and microvesiculation) and the exposure of phosphatidylserine, which was exteriorized following maximum calcium bursts (Figure 6A-B; supplemental Video 2).

Impact of genetic and pharmacological targeting of PA pathways on platelet calcium oscillations. (A) Representative images of time-lapse microscopy of migrating human platelets and respective calcium oscillations (green) and PS exposure (annexin V, pink). PH, phase contrast. Bar represents 10 µm. White boxes indicate the area of measurement analyzed in (B). See supplemental Video 2 for corresponding live imaging. (B) Intensity projection for calcium (blue) and PS signal intensity (red) over time as % of maximum intensity for cells 1 to 3. (C) Representative calcium oscillation profiles of migrating platelets from CypD- or TMEM16F-deficient compared with platelets from PF4cre-negative animals. (D) Quantification of mean normalized calcium amplitudes and calcium peak frequency measured from mouse platelets across genotypes. n = 103 individual platelets. One-way ANOVA with Holm-Šídák's multiple comparison test. (E) Representative micrographs and calcium (blue) and PS intensity profiles (mC1, red) derived from live imaging of the 2 CypD-deficient mouse platelets indicated by white boxes. Bar represents 10 µm. Arrows indicate the beginning of contact to collagen fibers. (F) Relative quantification of percentage of supramaximal calcium peaks of all collagen-associated mouse platelets as well as relative quantification of supramaximal calcium peak-positive procoagulant platelets. Individual dots represent percentages derived from individual time-lapse microscopy videos. Platelets were isolated from n = 2 to 3 mice/group. PS staining agent: mC1. One-way ANOVA with Holm-Šídák's multiple comparisons test.

Impact of genetic and pharmacological targeting of PA pathways on platelet calcium oscillations. (A) Representative images of time-lapse microscopy of migrating human platelets and respective calcium oscillations (green) and PS exposure (annexin V, pink). PH, phase contrast. Bar represents 10 µm. White boxes indicate the area of measurement analyzed in (B). See supplemental Video 2 for corresponding live imaging. (B) Intensity projection for calcium (blue) and PS signal intensity (red) over time as % of maximum intensity for cells 1 to 3. (C) Representative calcium oscillation profiles of migrating platelets from CypD- or TMEM16F-deficient compared with platelets from PF4cre-negative animals. (D) Quantification of mean normalized calcium amplitudes and calcium peak frequency measured from mouse platelets across genotypes. n = 103 individual platelets. One-way ANOVA with Holm-Šídák's multiple comparison test. (E) Representative micrographs and calcium (blue) and PS intensity profiles (mC1, red) derived from live imaging of the 2 CypD-deficient mouse platelets indicated by white boxes. Bar represents 10 µm. Arrows indicate the beginning of contact to collagen fibers. (F) Relative quantification of percentage of supramaximal calcium peaks of all collagen-associated mouse platelets as well as relative quantification of supramaximal calcium peak-positive procoagulant platelets. Individual dots represent percentages derived from individual time-lapse microscopy videos. Platelets were isolated from n = 2 to 3 mice/group. PS staining agent: mC1. One-way ANOVA with Holm-Šídák's multiple comparisons test.

To investigate the impact of CypD- and TMEM16F-deficiency on calcium currents of migrating platelets, we performed additional live imaging experiments. Migrating platelets from both wild-type and CypD- or TMEM16F-deficient mice exhibited similar baseline calcium oscillation profiles (Figure 6C). Both calcium oscillation frequency and mean oscillation amplitudes did not differ between genotypes (Figure 6D). However, in contrast to both control and TMEM16F-deficient platelets, migrating CypD-deficient platelets continued to show rhythmic calcium oscillations despite ongoing physical interaction with collagen (Figure 6E-F; supplemental Figure 6B-E). Consequently, we hardly detected supramaximal calcium bursts in CypD-deficient platelets in contact with collagen fibers, confirming CypD-dependent mitochondrial depolarization to be crucial for PA of migrating platelets without affecting baseline oscillations necessary for migratory capacity (Figure 6F). The few CypD-deficient platelets mounting a procoagulant activation response took longer to achieve supramaximal calcium peaks (supplemental Figure 6C-E), suggesting compensatory calcium currents in the absence of the CypD-dependent mitochondrial permeability transition pore formation43 (supplemental Figure 6F-G). In contrast to CypD-deficient platelets, TMEM16F-deficient platelets turning procoagulant also exhibited supramaximal calcium currents, confirming that calcium peaks precede scramblase activity (Figure 6F; supplemental Figure 6D-E).46,49 Notably, single inhibition of calcium currents such as store-operated, mitochondrial, or extracellular calcium entry44 reduced PA without affecting migratory capacity, which was only attenuated when all 3 sources of calcium were blocked simultaneously. This suggests functional redundancy of the individual calcium currents in maintaining migratory capacity (supplemental Figure 6F-G).

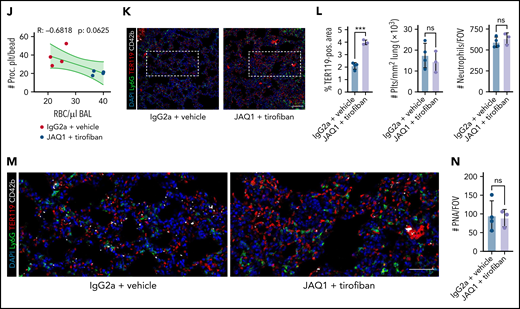

Pharmacological inhibition of platelet PA by combined GPIIBIIIA and GPVI blockade aggravates inflammatory bleeding in vivo

Next, we investigated which platelet activation pathways and receptors are crucially involved in platelet PA upon migration and collagen sensing. We have previously shown that platelet migration depends on GPIIBIIIA activation (supplemental Figure 7A-B) as well as actin-myosin networks.8,9 In line, downstream inhibition of Rho kinase, phospholipase Cγ, myosin light chain, and Rac1,1,50 inhibited platelet migration reduced the likelihood of encountering collagen fibers and, consequently, reduced platelet PA (supplemental Figure 7C-D). Because platelets in solution showed no procoagulant function in the presence of fibrinogen and collagen (compare supplemental Figure 3D-F), we hypothesized that GPIIBIIIA-dependent mechanosensing might influence PA.34,51 Indeed, when we partially inhibited mechanosensitive GPIIBIIIA outside-in signaling by targeting Gα13, platelet PA was effectively inhibited while platelet migration remained intact despite characteristic morphological changes51,52 (Figure 7A-B; supplemental Figure 7E-F). The significant increase in migration was likely due to reduced PA on collagen-coated matrices because mP6-treated platelets moving on fibrinogen/albumin matrices did not migrate farther than their respective controls (supplemental Figure 7G).

Pharmacological ablation of platelet PA through simultaneous GPIIBIIIA and GPVI inhibition aggravates inflammatory bleeding. (A) Experimental scheme of migration assay on hybrid matrix with targeting of platelet receptors and signaling cascades. (B-C) Quantification of procoagulant platelets and cleared area by murine (B) and human platelets (C) treated with inhibitors of GPVI signaling (BI-1002494 = Syk inhibitor, 5 µM; JAQ1 = GPVI-blocking antibody, 10 µg/mL) or GPIIBIIIA outside-in signaling (mP6 = Gα13 inhibitor, 20 µM). One-way ANOVA with Holm-Šídák's multiple comparisons test. (D) Representative images of time-lapse microscopy of migrating human platelets and respective calcium oscillations (blue) and PS exposure (red) recorded after 0, 2, and 8 minutes of migration. Bar represents 10 µm. White boxes indicate the area of measurement depicted next to micrographs. See supplemental Video 3 for corresponding live imaging. (E) Upper panel: Quantification of calcium peaks of migrating human platelets treated with vehicle, mP6 (20 µM) or BI-1002494 (2.5 µM). Lower panel: Relative quantification (%) of migrating, collagen-associated platelets treated with vehicle, mP6, or BI-1002494 that express supramaximal calcium peaks upon collagen contact (n = 5-6 videos from n = 2-3 mice per condition with a total of >100 platelets were analyzed). One-way ANOVA with Holm-Šídák's multiple comparisons test. (F) Experimental scheme for acute lung injury in Bl6 mice treated with JAQ1, a GPVI-blocking antibody, or isotype (red arrow) 72 hours prior to LPS challenge (blue arrow) and vehicle or tirofiban injections (red arrows) at 0, 4, and 8 hours after LPS challenge. (G) Representative image of BALF collected from different experimental groups. (H) Assessment of Hb absorption and flow cytometric analysis of RBC, polymorphonuclear, and platelet counts in BALF (n = 4 mice per group). One-way ANOVA with Holm-Šídák's multiple comparisons test compared with control groups. (I) Flow cytometric measurement of circulating procoagulant platelets in peripheral blood, normalized to counting beads. Student’s t test, two-tailed, unpaired. (J) Linear regression analysis of the correlation of circulating procoagulant platelets and inflammatory bleeding severity as assessed by RBC count/µL BALF. (K) Representative micrograph of immunofluorescence-stained lung slices from IgG2a and vehicle vs JAQ1 and tirofiban-treated animals. Bar represents 100 µm. (L) Quantification of alveolar hemorrhage (TER119+ area) as well as pulmonary platelet and neutrophil recruitment. PS staining agent for all experiments shown in Figure 7: mC1. n = 4 mice per group. Student’s t test, two-tailed, unpaired. (M) Magnified excerpts of representative immunofluorescence stainings, corresponding to white rectangles in Figure 7K. Bar represents 50 µm. (N) Histopathological quantification of pulmonary PNAs per FOV 24 hours after LPS challenge. Student’s t test, two-tailed, unpaired.

Pharmacological ablation of platelet PA through simultaneous GPIIBIIIA and GPVI inhibition aggravates inflammatory bleeding. (A) Experimental scheme of migration assay on hybrid matrix with targeting of platelet receptors and signaling cascades. (B-C) Quantification of procoagulant platelets and cleared area by murine (B) and human platelets (C) treated with inhibitors of GPVI signaling (BI-1002494 = Syk inhibitor, 5 µM; JAQ1 = GPVI-blocking antibody, 10 µg/mL) or GPIIBIIIA outside-in signaling (mP6 = Gα13 inhibitor, 20 µM). One-way ANOVA with Holm-Šídák's multiple comparisons test. (D) Representative images of time-lapse microscopy of migrating human platelets and respective calcium oscillations (blue) and PS exposure (red) recorded after 0, 2, and 8 minutes of migration. Bar represents 10 µm. White boxes indicate the area of measurement depicted next to micrographs. See supplemental Video 3 for corresponding live imaging. (E) Upper panel: Quantification of calcium peaks of migrating human platelets treated with vehicle, mP6 (20 µM) or BI-1002494 (2.5 µM). Lower panel: Relative quantification (%) of migrating, collagen-associated platelets treated with vehicle, mP6, or BI-1002494 that express supramaximal calcium peaks upon collagen contact (n = 5-6 videos from n = 2-3 mice per condition with a total of >100 platelets were analyzed). One-way ANOVA with Holm-Šídák's multiple comparisons test. (F) Experimental scheme for acute lung injury in Bl6 mice treated with JAQ1, a GPVI-blocking antibody, or isotype (red arrow) 72 hours prior to LPS challenge (blue arrow) and vehicle or tirofiban injections (red arrows) at 0, 4, and 8 hours after LPS challenge. (G) Representative image of BALF collected from different experimental groups. (H) Assessment of Hb absorption and flow cytometric analysis of RBC, polymorphonuclear, and platelet counts in BALF (n = 4 mice per group). One-way ANOVA with Holm-Šídák's multiple comparisons test compared with control groups. (I) Flow cytometric measurement of circulating procoagulant platelets in peripheral blood, normalized to counting beads. Student’s t test, two-tailed, unpaired. (J) Linear regression analysis of the correlation of circulating procoagulant platelets and inflammatory bleeding severity as assessed by RBC count/µL BALF. (K) Representative micrograph of immunofluorescence-stained lung slices from IgG2a and vehicle vs JAQ1 and tirofiban-treated animals. Bar represents 100 µm. (L) Quantification of alveolar hemorrhage (TER119+ area) as well as pulmonary platelet and neutrophil recruitment. PS staining agent for all experiments shown in Figure 7: mC1. n = 4 mice per group. Student’s t test, two-tailed, unpaired. (M) Magnified excerpts of representative immunofluorescence stainings, corresponding to white rectangles in Figure 7K. Bar represents 50 µm. (N) Histopathological quantification of pulmonary PNAs per FOV 24 hours after LPS challenge. Student’s t test, two-tailed, unpaired.

Seminal studies have established that fibrin(ogen) is also bound by collagen receptor GPVI and that platelet activation and subsequent thrombin turnover are increased upon GPVI-mediated fibrin(ogen) sensing.53-56 The impact of GPVI on PA of migrating platelets, however, remains elusive. Inhibition of GPVI signaling using either an anti-GPVI antibody or the novel Syk kinase inhibitor BI-1002494 diminished mouse platelet PA (Figure 7A-B). Interestingly, migratory capacity of murine platelets decreased only when using higher doses of BI-1002494, whereas increasing concentrations of GPVI-blocking JAQ1 had no such effect (supplemental Figure 7H-I). This indicates that GPVI-mediated fibrinogen binding is dispensable for platelet migration in vitro. Modulating GPIIBIIIA-Gα13 signaling or GPVI signaling in human platelets also attenuated PA without affecting migration (Figure 7C). In contrast, treatment of human platelets with the small molecule antagonist TC-I15, which inhibits the collagen receptor integrin α2β1, had no effect on PA, indicating that collagen sensing through this receptor is not required for PA of migrating platelets (supplemental Figure 7J).

Time-lapse microscopy of platelets treated with low-dose GPIIBIIIA outside-in signaling inhibitors or GPVI antagonists revealed no alterations in amplitude and frequency of calcium oscillations but showed that treated platelets that encountered collagen fibers did not mount supramaximal calcium bursts (Figure 7D-E; supplemental Figure 7K-L; supplemental Video 3). This finding highlights that co-engagement of GPVI and GPIIBIIIA outside-in signaling triggers supramaximal calcium release and, in turn, platelet PA. Strikingly, inhibition of both pathways resulted in additive suppression of procoagulant function, whereas migratory capacity was retained (supplemental Figure 8A-B).

Finally, we sought to confirm the identified pathways in vivo. We first evaluated the effective blockade of GPIIBIIIA and depletion of GPVI in mice by using the clinically available integrin antagonist tirofiban57 and a GPVI-depleting antibody (JAQ1), respectively58 (Figure 7F; supplemental Figure 8C-G). While intraperitoneal injection of JAQ1 reduced the surface expression of GPVI (supplemental Figure 8C-D), tirofiban treatment effectively blocked integrin activation in thrombin- and convulxin-activated mouse platelets (supplemental Figure 8E-F). Tirofiban did not affect murine or human platelet migration in vitro at the indicated concentrations but reduced procoagulant potential; this effect was further enhanced upon dual blockade with both tirofiban and JAQ1 (supplemental Figure 8A-B,G).

When we performed acute lung injury experiments on Bl6 mice treated with JAQ1, tirofiban, or both, only simultaneous blockade of GPIIBIIIA and GPVI aggravated alveolar hemorrhage 24 hours after LPS challenge (Figure 7F-H). Alveolar neutrophil recruitment did not differ (Figure 7H). Although most neutrophils were coated with platelets, we detected few free-floating platelets in BALF, excluding BAL contamination by traumatic vessel leakage (Figure 7H). Flow cytometry of blood samples revealed a significant decrease in circulating procoagulant platelets only in mice receiving dual treatment (Figure 7I). Circulating procoagulant platelet counts negatively correlated with excessive alveolar hemorrhage (Figure 7J). Apart from GPVI expression, we detected no differences in platelet receptor surface expression and PNA formation across treatment groups, and clinical status remained similar between treatment conditions (supplemental Figure 8H-K). Histologically, we confirmed increased alveolar hemorrhage upon dual inhibition but did not detect any differences in pulmonary neutrophil and platelet recruitment or PNA formation (Figure 7K-N). We also depleted GPIIBIIIA and GPVI and challenged mice with intraperitoneal LPS injections (supplemental Figure 8L-R). PA of both circulating and adherent platelets was effectively reduced, and we detected an increase in mesenteric microbleeding in our model, suggesting that platelet PA may be involved in maintaining vascular homeostasis in mesenteric inflammation (supplemental Figure 8M-R).

In summary, pharmacological inhibition of procoagulant platelet activation by dual targeting of GPIIBIIIA and GPVI reduced platelet PA in vivo and exacerbated inflammatory microbleeding in both lung and mesentery.

Discussion

Platelets are uniquely positioned to be vascular first responders due to their short reaction time and abundancy in peripheral blood. Recent work has revealed that platelets recruited to sites of inflammation behave differently using a distinct set of receptors and signaling pathways. In contrast to classical thrombus formation, single platelets are recruited to the vascular endothelium under inflammatory conditions.8,22 These platelets crucially maintain vascular integrity because severe thrombocytopenia exacerbates endothelial leakage and inflammatory hemorrhage.24,31,59,60 However, it remains insufficiently understood how platelets effectively seal endothelial defects in the absence of clot formation.17

Here, we describe a novel effector function of immune-responsive platelets (procoagulant activity) that recruits the coagulation cascade and has a critical role in maintaining local vascular integrity without triggering diffuse intravascular clotting. We show that platelets migrate at sites of vascular injury and fibrin(ogen) deposition, constantly scanning their microenvironment. Upon encountering vascular breaches with exposure of subendothelial collagen, migrating platelets engage GPVI, which triggers intracellular calcium release and PS exposure. This arrests platelets at the injury site and allows binding of the prothrombinase complex on the platelet membrane, greatly enhancing thrombin activity resulting in fibrin formation.32 Importantly, our study does not address the origin of fibrin(ogen) deposits, leaving the question of whether local fibrin(ogen) accumulation derives from plasma or platelet-intrinsic storage pools. Previous studies provide evidence that α-granule secretion is dispensable for inflammatory hemostasis,27,61 and we have found no evidence of substantial fibrinogen secretion by procoagulant platelets in vitro.

The identified mechanism effectively targets the coagulation cascade to breaches identified by patrolling platelets and might therefore circumvent widespread coagulation activation. In line with this, blocking GPVI and GPIIBIIIA reduced procoagulant platelets in vivo and enhanced hemorrhage in lung and mesentery alike following LPS exposure. These findings highlight glycoprotein redundancy in inflammatory platelet signaling in vivo as observed by other groups: GPVI was previously thought to be entirely dispensable for the prevention of bleeding in the lung, as shown using GPVI-knockout animals.17,22,28,62 In our hands, antibody-mediated blockade of GPVI alone confirmed this observation and resulted in no aggravation of inflammatory bleeding. Moreover, our study may reconcile previously dichotomous findings regarding the role of GPIIBIIIA in the inflammatory hemostasis in the lung: While some studies found no significant effect of pharmacological inhibition of GPIIBIIIA using direct inhibitors like integrillin or a GPIIBIIIA-targeted antibody on inflammatory bleeding, plasma leakage, and alveolar neutrophil recruitment,28,63 we have previously shown that genetic ablation of GPIIBIIIA using bone marrow chimeric mice aggravates LPS-induced pulmonary hemorrhage.8 The bleeding phenotype reported in our recent study may be attributable to the loss of migratory capacity that is observed in GPIIBIIIA-deficient platelets but not in pharmacological inhibition.9 In the current study, we only observed a significant increase in inflammatory hemorrhage upon dual inhibition of GPVI and GPIIBIIIA while providing evidence that neither single nor dual inhibition of either receptor impaired migratory capacity in vitro (supplemental Figure 8A). Additional factors such as extracellular vesicle formation, which is affected by GPIIBIIIA blockade through tirofiban64 and can itself impact on hemostasis,65 were not investigated in this study and may also contribute to the observed bleeding phenotype. Specific pharmacological inhibition of platelet PA and thus reduction of procoagulant PS expression, as mediated through maintaining flippase activity in procoagulant platelets,66 may specifically address these remaining aspects.

Preventing procoagulant activity by genetic ablation of either CypD-dependent mitochondrial permeability transition pore formation or TMEM16F scramblase-dependent phosphatidylserine exposure exacerbated inflammatory bleeding while having a negligible effect on classical hemostasis assessed by tail bleeding assay.42 Although we describe a protective local effect of procoagulant activity, circulating procoagulant platelets have been associated with both local and remote organ injury as well as disseminated intravascular coagulation.41,67 Denorme et al.41 highlighted a detrimental role for PS-positive PNAs in ischemic stroke, which aggravated brain damage and vascular obstruction. In COVID-19, the level of antibody-induced circulating procoagulant platelets correlated with d-dimer levels and an increased incidence of systemic thromboembolism.68 Considering these data, it is tempting to speculate that even though local induction of procoagulant platelets may be crucial to maintain vascular integrity in inflammation, systemic and dysregulated procoagulant platelet activation could be one of the drivers of systemic coagulation activation.32,67,69,70 Further studies are needed to define factors that trigger systemic platelet PS exposure and investigate the role of platelet procoagulant activity in other conditions with increased vascular permeability, as observed in cancer.10 In inflammatory bleeding, the involvement of specific platelet signaling pathways and receptors as well as degranulation has been shown to be highly dependent on the mode of injury and the respective vascular bed.17,21,23,24,27,61 Therefore, further studies need to define platelet-coagulation interplay in distinct inflammatory contexts. Finally, it remains unclear whether other platelet receptors such as CLEC-2, which is known to attenuate acute lung injury through podoplanin-mediated interplay with alveolar macrophages71 but does not affect inflammatory bleeding severity,28 and the GPIb-IX-V complex that play a role in the prevention of inflammatory bleeding can also trigger platelet procoagulant activity.27 In particular, combined inhibition of other platelet glycoproteins may yield additional insights into potential functional redundancies in the context of inflammatory bleeding.72

Limitations of this study include the lack of generalizability of platelet PA as a platelet-inherent protective function in other models of inflammatory hemorrhage, particularly neutrophil-driven ischemic-reperfusion injury of the brain, sterile injury of the skin microvasculature, and tumor-associated bleeding.17,22,26,27 We also note that compared with the severe bleeding phenotype observed in thrombocytopenic animals, the increase in pulmonary hemorrhage upon pharmacological or genetic interference with platelet PA was not as severe, suggesting compensatory mechanisms beyond PA that may mask its intrinsic contribution to inflammatory hemostasis (supplemental Table 2). Although we observed no effect on neutrophil and leukocyte recruitment to the lungs of CypD- and TMEM16F-deficient mice, the lack of platelet PA may influence the inflammatory microenvironment and promote endothelial dysfunction beyond aggravating inflammatory hemorrhage. Thus, future studies need to elucidate the functional role of procoagulant platelets in both local and systemic inflammatory responses.

In summary, we describe an essential function of procoagulant platelets in promoting vascular integrity in inflammation, adding to the pivotal role of platelets across the inflammatory spectrum and the complex pathophysiology of inflammatory hemorrhage.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all laboratory members for technical support.

This study was supported by the Deutsche Herzstiftung e.V., Frankfurt a.M. (R.K. and L.N.), Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) SFB 914 (S.M. [B02 and Z01] and K.S. [B02]), the DFG Project-ID 210592381 – SFB 1054 (T.B. [B03 and Z01]), the DFG SFB 1123 (S.M. [B06] and K.S. [A07]), the DFG FOR 2033 (S.M.), the German Center for Cardiovascular Research (DZHK) (Clinician Scientist Program [L.N.], Start-Up Grant [L.N.] 1.4VD [S.M.], the DFG Clinician Scientist Program PRIME (413635475, R.K. and K.P.) and the FP7 program (project 260309, PRESTIGE [S.M.]). This work was also supported by the European Research Council (ERC-2018-ADG “IMMUNOTHROMBOSIS” [S.M.] and ERC “T-MEMORE” [K.S.]).

Authorship

Contribution: L.N. initiated the study; R.K. and L.N. conceptualized the study; R.K., R.E., and L.N. created the methodology; R.K., R.E., J.K., M.-L.H., A.A., V.P., M.M., W.H., L.B., C.G., A.T., M.L., and L.N. conducted the investigation; R.K., K.P., S.K., F.G, K.S., T.B., S.M., and L.N. collected the resources; R.K., R.E., and L.N. conducted formal analysis; R.K. and L.N. wrote the original draft; all authors edited the draft; R.K., R.E., and L.N. handled data curation and software; R.K. visualized the study; R.K., J.K., K.P., K.S., T.B., S.M., and L.N. provided supervision and project administration; and R.K., K.S., S.M., and L.N. administered the funding.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: T.B. and J.K. have an exclusive licensing agreement with BioLegend, Inc. for the commercialization of mC1-multimer. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Rainer Kaiser, Medizinische Klinik und Poliklinik I, University Hospital, Ludwig-Maximilian University Munich, Marchioninistr 15, 81377 Munich, Germany; e-mail: rainer.kaiser@med.uni-muenchen.de; and Leo Nicolai, Medizinische Klinik und Poliklinik I, University Hospital, Ludwig-Maximilian University Munich, Marchioninistr 15, 81377 Munich, Germany; e-mail: leo.nicolai@med.uni-muenchen.de.

Data sharing is available upon request from the corresponding authors.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

![Genetic or pharmacological targeting of CypD and TMEM16F reduces procoagulant platelet activation without impairing migratory capacity. (A-B) Representative scatter plots and analyses derived from flow cytometric measurements of stimulated platelets from CypD- (A) or TMEM16F-knockout mice (B) (n = 3-4 mice per group). PS staining agent: mC1. Platelets were stimulated with thrombin (0.1 U/L) and convulxin (0.1 µg/mL) for 30 minutes at room temperature. Student’s t test, two-tailed, unpaired. (C-D) Representative micrographs of isolated murine platelets from platelet-specific CypD- (C) or TMEM16F- (D) knockout mice migrating on an albumin/fibrinogen/collagen I hybrid matrix. Quantification of platelet procoagulant activity and cleared area (as a surrogate for migration length) depicted as SuperPlots, with individual circles indicating individual images and the error bars corresponding to the mean data of 6 images of n = 3 to 4 mice per Cre-positive or -negative group. White dashed lines indicate collagen fibers. White arrowheads indicate migrating platelets with collagen contact but without procoagulant activity. White stars indicate procoagulant platelets. Bar represents 25 (left panel) and 15 µm (right panel). PS staining agent: mC1. Student’s t test, two-tailed, unpaired. (E) Experimental scheme of migration assay on hybrid matrix with targeting of platelet PA-promoting pathways. (F-G) Quantification of procoagulant platelets and cleared area by murine (F) and human platelets (G) treated with inhibitors of CypD (cyclosporine A, CicA, 2 µM) or TMEM16F (niflumic acid [NFA] 10 µM). One-way ANOVA with Holm-Šídák's multiple comparisons test compared with control groups. (H) Representative images of migrating human platelets stained for CD41 and PS (mC1) and incubated with an internally quenched 5-FAM/QXL 520 FRET substrate indicating thrombin activity. White arrowhead indicates a procoagulant, thrombin-positive platelet. Bar represents 10 µm. See supplemental Figure 4R for detailed images. (I) Cell-based quantification of thrombin-positive cells/FOV and the fraction of thrombin-positive cells as percentage of procoagulant platelets. Per condition, >100 cells from at least n = 2 animals were analyzed. One-way ANOVA with Holm-Šídák's multiple comparisons test compared with control groups.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/140/2/10.1182_blood.2021014914/4/m_bloodbld2021014914f4a.png?Expires=1769086340&Signature=u-Aj16FnR~Il-G-f5Wu4smVQt8Cb-y9CC94OQ9Uoax-CpVg9cFMsPAOE2y-iQxu1v72jIuLdt~OTxNsfiCzpvU7gq1l5HhoNFK8HmV7Lsa5XtyW4mg8oZJhmQnpw8dQmPb3bIbBuDk7tEeUm7R07HNHLS~Mbf8arzQv1gehM7Ln0-FJFDI5b0-Q-lVaMxmn4hfymO40Al~HHwkgFAK0uu8bLf0qbQUrtzutBfuFRmNhpxooUfOHSLPhLsq05SZL2glTm2WRRyw~l4tuJvaGr9uOSp9LZ8dLqL4gTdFrbNaJWfvunM9Ojs906e4kNrdj7SbppBZMOlFC9xWItSCdEdg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)