Abstract

The clinical phenotype of primary and post–polycythemia vera and postessential thrombocythemia myelofibrosis (MF) is dominated by splenomegaly, symptomatology, a variety of blood cell alterations, and a tendency to develop vascular complications and blast phase. Diagnosis requires assessing complete cell blood counts, bone marrow morphology, deep genetic evaluations, and disease history. Driver molecular events consist of JAK2V617F, CALR, and MPL mutations, whereas about 8% to 10% of MF are “triple-negative.” Additional myeloid-gene variants are described in roughly 80% of patients. Currently available clinical-based and integrated clinical/molecular-based scoring systems predict the survival of patients with MF and are applied for conventional treatment decision-making, indication to stem cell transplant (SCT) and allocation in clinical trials. Standard treatment consists of anemia-oriented therapies, hydroxyurea, and JAK inhibitors such as ruxolitinib, fedratinib, and pacritinib. Overall, spleen volume reduction of 35% or greater at week 24 can be achieved by 42% of ruxolitinib-, 47% of fedratinib-, 19% of pacritinib-, and 27% of momelotinib-treated patients. Now, it is time to move towards new paradigms for evaluating efficacy like disease modification, that we intend as a robust and unequivocal effect on disease biology and/or on patient survival. The growing number of clinical trials potentially pave the way for new strategies in patients with MF. Translational studies of some molecules showed an early effect on bone marrow fibrosis and on variant allele frequencies of myeloid genes. SCT is still the only curative option, however, it is associated with relevant challenges. This review focuses on the diagnosis, prognostication, and treatment of MF.

Introduction

Myelofibrosis (MF) consists of 2 entities: primary MF (PMF) and post–polycythemia vera (PPV) and post–essential thrombocythemia (PET) MF, also known as secondary MF (SMF).1 MF is a myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN) with a clinical phenotype dominated by splenomegaly, constitutional symptoms, a variety of blood cell alterations, and a tendency to develop vascular complications and blast phase (BP).2

Perturbation of the JAK/STAT signaling pathway is the hallmark of MF. This finally leads to hematopoietic stem defects with abnormal proliferation of megakaryocytes, which fail the hematopoietic transcription factor GATA1 expression and of granulocytes. Consequently, secretion of inflammatory cytokines results in myeloproliferation, increased bone marrow fibrosis (BMF), and extramedullary hematopoiesis.3 Besides this pathway, others are involved in MF, some of whom are druggable. Two-thirds of patients with PMF harbor the JAK2V617F mutation, one-quarter have CALR mutations, and 10% have each MPL mutation or “triple-negative” (TN) status.3 In addition, roughly 80% carry additional myeloid-gene variants.3 Although all patients with PPV-MF carry JAK2 mutations, nearly half of patients with PET-MF displayed JAK2V617F, 30% CALR, and around 5% to 10% MPL mutations or TN status.4

The current treatment landscape of MF consists of anemia-oriented therapies, hydroxyurea (HU), JAK inhibitors (JAKis), such as ruxolitinib (RUX), fedratinib (FEDR), pacritinib (PAC), and momelotinib (MMB), and allogenic stem cell transplantation (SCT) with a growing number of clinical trials. This review focuses on the diagnosis, prognostication, and treatments of PMF and PPV/PET-MF.

Diagnostic criteria

The International Consensus Classification (ICC) of hematological malignancies and the fifth edition of the World Health Organization classification, recently published, kept MF within the “classic” BCR::ABL1-negative MPNs.1,5

The 2022 World Health Organization classification remains mostly unchanged compared with the fourth edition.5 It recognizes JAK2, CALR, and MPL gene variants as driver events, TET2, ASXL1, and DNMT3A genes as involved in over half of the patients with MF, and mutations affecting splicing regulators and regulators of chromatin structure, epigenetic functions, and cellular signaling as less common.5

The ICC reports tables of diagnostic criteria for PMF and PPV/PET-MF (Table 1) and strengthens the role of morphology by looking at megakaryocytic atypia as well as the typical MF-pattern of age-related cellularity, erythropoiesis and granulopoiesis modifications, and BMF.1 Finding dense clustering of megakaryocytes was stated not elusive of ET.1 Notably, the ICC indicates to assess driver mutations with assays having a minimal variant allele frequency (VAF) sensitivity of 1% and to search for noncanonical JAK2/MPL mutations in TN cases and for coexisting canonical CALR/MPL mutations in low–JAK2-VAF cases.1,6

Overall, morphological bone marrow (BM) assessment in MF remains constrained by a reliance on subjective and qualitative criteria. Recently, convolutional neural networks applied to a large data set of microscopic cytological images taken from BM smears of hematological diseases outperformed previous feature-based approaches.7 MF morphological features in the slide analysis could be captured by applying computational methods, such as deep learning.8

Outcome

The median survival of the prefibrotic PMF, overt PMF, and SMF populations is about 14 years, 6 to 7 years, and 9 years, respectively.2,9,10 Major increased risk of mortality stemmed from myeloid malignancies, with a high rate of infection- and cardiovascular-related deaths,11 driven by disease morbidity.12,13

In the last decades, improvements in survival have been registered, starting with the pivotal report of the International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS) investigators14 and continuing with a recent analysis of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End User Results database.15 Earlier diagnosis, deeper knowledge of pathogenesis, shared criteria for SCT-candidate selection, wide use of JAKis, and better supportive care are the main contributors to this improvement.

Prediction of survival

The IPSS model was introduced in 2009 and applied in clinical practice and clinical trials.2 The updated National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines (version 3.2022) indicate to use the risk models reported in Table 2,16 namely, the mutation-enhanced IPSS (MIPSS-70)17 or MIPSS-70+ version 2.0,18 the dynamic IPSS (DIPSS+)19 if absent molecular testing or the DIPSS if absent karyotyping20 in PMF, and the MF secondary to polycythemia vera and essential thrombocythemia prognostic model (MYSEC-PM, www.mysec-pm.eu) in SMF.10 This multitude of models reflects the magnitude of knowledge accumulated over the last few years.

DIPSS assessment is easy to apply and timely available,20 whereas others require technology and an execution time of 2 to 4 weeks because they include molecular testing and/or karyotyping.10,17-19 Although the DIPSS/DIPSS+/MYSEC-PM models evaluated patients of all ages,10,19,20 the MIPSS-70 was designed for SCT decision-making with a training cohort of ≤70 years.17 Clinical parameters such as advanced age, degree of anemia or leukocytosis, circulating blasts, and constitutional symptoms keep their importance in all models, whereas thrombocytopenia enriched the DIPSS+, MIPSS-70, and MYSEC-PM.10,17-20 BMF grade was introduced in the MIPSS-70 with a known valuable role in survival prediction.9,17 Despite testing cytogenetic is not common in PMF (only half of the MIPSS-70 learning cohort),17 60% to 70% and 11% to 22% of patients have a normal and unfavorable karyotype, respectively.17 Karyotyping has been included in the DIPSS+,19 genetically inspired PSS (GIPSS),21 and MIPSS-70+/versions.18 Once the association between some gene variants and MF outcome was established, those composing the high molecular risk (HMR) profile (ASXL1, SRSF2, EZH2, IDH1, and IDH2),22 the U2AF1Q157 variant or CALR type 1/type 1–like entered the MIPSS-70/versions,17,18 and the absence of CALR the MYSEC-PM.10 In the original MIPSS-70 cohort, 80% of individuals did not disclose CALR type 1 mutations, becoming a very common risk factor, 31% to 41% carried the HMR genotype, and 8% to 9% had 2 or more HMR mutations.17

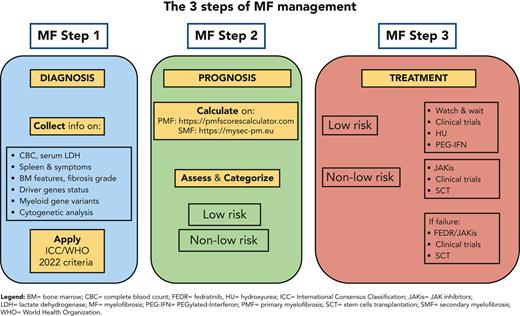

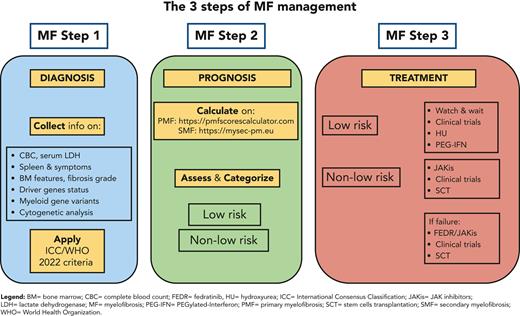

Stratification of patients is relevant for treatment decision-making (Figure 1), especially for SCT-candidate selection. In our opinion, PMF models should be simultaneously assessed and reported in the patients’ clinical chart. To facilitate this, we developed a PMF-specific web calculator available at https://pmfscorescalculator.com, including the National Comprehensive Cancer Network-suggested models. In daily clinical practice, although survival prediction concordance among models is reassuring for decision-making (especially for SCT), the discordance is challenging. As an example, a 52-year-old patient with JAK2-mutated PMF at DIPSS intermediate-1 (quasi-normal blood cells and symptoms) has an expected median survival of 14 years. The presence of BMF grade 2, a normal karyotype, and the ASXL1 mutation sets the patient within intermediate-risk MIPSS-70 (median survival, 6-7 years) and high-risk MIPSS-70+V2 (median survival, 4 years). In such cases, we monthly follow the patient, start donor search delaying SCT indication at first signs of clinical progression.

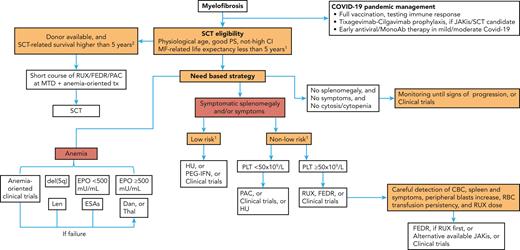

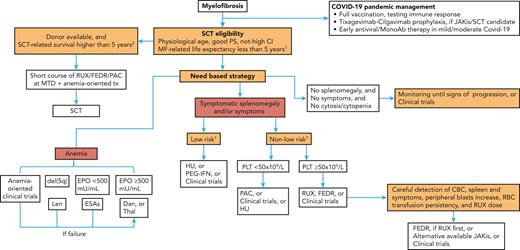

Current management of MF. This algorithm represents our approach to the management of MF with some considerations on COVID-19, SCT selection, anemia-oriented treatments, and risk-based strategy to control clinical needs of patients. CBC, complete blood count; CI, cormorbidity index; Dan, danazol; del, deletion; EPO, erythropoietin; ESAs, erythropoiesis stimulating agents; FEDR, fedratinib; HU, hydroxyurea; JAKis, JAK inhibitors; Len, lenalidomide; MF, myelofibrosis; MonoAb, monoclonal antibody; MTD, maximum tolerated dose; PAC, pacritinib; PEG-IFN, PEGylated-interferon; PLT, platelets; PS, performance status; RBC, red blood cells; RUX, ruxolitinib; SCT, stem cells transplant; Thal, thalidomide; tx, treatment. 1As for DIPSS/apex (Dynamic International Prognostic Scoring System) or MIPSS-70/apexV2 (Mutation-Enhanced International Prognostic Scoring System) or MYSEC-PM (Myelofibrosis Secondary to polycythemia vera and essential thrombocythemia-Prognostic Model. 2Low, intermediate and selected high-risk MTSS (Myelofibrosis Transplant Scoring System) cases.

Current management of MF. This algorithm represents our approach to the management of MF with some considerations on COVID-19, SCT selection, anemia-oriented treatments, and risk-based strategy to control clinical needs of patients. CBC, complete blood count; CI, cormorbidity index; Dan, danazol; del, deletion; EPO, erythropoietin; ESAs, erythropoiesis stimulating agents; FEDR, fedratinib; HU, hydroxyurea; JAKis, JAK inhibitors; Len, lenalidomide; MF, myelofibrosis; MonoAb, monoclonal antibody; MTD, maximum tolerated dose; PAC, pacritinib; PEG-IFN, PEGylated-interferon; PLT, platelets; PS, performance status; RBC, red blood cells; RUX, ruxolitinib; SCT, stem cells transplant; Thal, thalidomide; tx, treatment. 1As for DIPSS/apex (Dynamic International Prognostic Scoring System) or MIPSS-70/apexV2 (Mutation-Enhanced International Prognostic Scoring System) or MYSEC-PM (Myelofibrosis Secondary to polycythemia vera and essential thrombocythemia-Prognostic Model. 2Low, intermediate and selected high-risk MTSS (Myelofibrosis Transplant Scoring System) cases.

Besides these well-structured models, other factors were demonstrated to have an association with outcome: increased BM or circulating blasts, by morphology23,24; increased circulating CD34+ cells and decreased side scatter of neutrophils by flow cytometry, possibly to be integrated with conventional risk factors in PMF25; TP53, CBL, or N/KRAS mutations26; myelodepletive phenotype in PMF27; frailty status28; quality of life score29; and some individual comorbidities.30

Prediction of myeloid evolution and cardiovascular events

Myeloid evolution into BP occurs in 10% to 15% of MF with a very short survival afterward.4,17,31 Whenever it is requested, the DIPSS or MIPSS-70/70+ models are useful to predict BP in PMF.17,31 Additional factors were associated with inferior BP-free survival as transfusion-requiring anemia, increased levels of serum interleukin-8 and C-reactive protein, monosomal karyotype, TN status, alterations in RAS/MAPK pathway genes, RUNX1, CEBPA, and SH2B3 variants.32

Information on cardiovascular events in MF is scant; however, its incidence is not negligible: 1.6% to 2.2% patients per year in PMF and 2.3% in SMF.13,33,34 Age over 60 years, JAK2-signature, and IPSS score resulted in predictors in PMF,13,33 whereas cytoreductive treatments were protective in SMF.34 This points out the need to evaluate the use of antiplatelet therapy in MF while balancing the risk of bleeding. This latter has been recently estimated at 1.5% patients per year, with higher IPSS categories and anticoagulants increasing the risk.33 Pulmonary hypertension is a nonrare event in MPNs,35 requiring a careful monitoring of symptoms with transthoracic echocardiography in the case of early signals.

Treatment overview

We propose a treatment strategy for patients with MF without distinguishing PMF and SMF (Figure 1), first positioning SCT, then planning treatment for anemia control and for splenomegaly/symptomatology improvement based on risk stratification. Excessive myeloproliferation, that is, leukocytosis and/or thrombocytosis, is commonly associated with symptomatology or splenomegaly and managed accordingly; otherwise, HU can be considered for controlling cytosis. The MOST study showed that HU has been used in 46% of treated patients at lower risk.36 However, in a study on 40 HU-treated MF, a clinical improvement was reached in 40% of patients with a short duration of response (DOR) of 13 months.37Tables 3-6 will present treatment options beyond HU.

Considerations during COVID-19

Patients with MF have worse outcomes after COVID-19,38 with a potential deleterious effect of unjustified RUX discontinuation after severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) exposure. Patients receiving RUX have an impaired immune response to the COVID-19 vaccination.39 Patients with MF on RUX or around SCT are candidates for antivirals (advised a reduction of RUX dose with nirmatrelvir/ritonavir) in case of SARS-CoV-2 exposure and for pre-exposure prophylaxis with tixagevimab/cilgavimab (if available),40 according to local variant of concern.

Anemia-oriented treatments

Anemia represents a challenge in MF management, either when dominating the clinical phenotype or when accompanying symptoms and splenomegaly, and either because of disease progression or because of the on-target effect of JAKi. The aim of improving anemia is, besides quality of life, the control of the boundary of transfusions with a reduction of iron overload and its relative consequences, such as infections, endocrine, liver, and cardiac complications in long-term survivors. Iron chelation safety and efficacy have not been extensively investigated in MF. A retrospective study showed that 48% of 69 patients with MF treated with RUX and deferasirox achieved an iron chelation response sustained for 3 months.41

Anemia response is usually defined according to the International Working Group on Myeloproliferative Neoplasms Research and treatment (IWGMRT) criteria42: transfusion cessation if previous RBC transfusion dependency (TD), or hemoglobin increase ≥2 g/dL (modifiable in 1.5 g/dL)43 in case of RBC transfusion independency (TI).

Erythropoiesis-stimulating agents allowed anemia responses in 53% of 163 patients (29% in patients with TD, 57% in patients with TI), with a median DOR of 19 months regardless of concomitant JAKi.44 Anemia response with danazol was reported in 30% of 50 patients (18% in patients with TD, 43% in patients with TI).45 Thalidomide or lenalidomide have limited activity (TI rates of 11% and 16%, respectively).46 Lenalidomide is effective in patients carrying del(5q).47 Pomalidomide failed to reach the end point of RBC-TI vs placebo in the RESUME study.48 Combining pomalidomide with RUX, a phase 2 trial on 89 patients with anemia showed a 1-year IWGMRT-response rate of 10% to 21%.49

To improve anemia in MF, modification of the cytokines within the BM microenvironment by targeting TGFβ superfamily was explored. Luspatercept, a Smad2/3-pathway ligand trap, is under evaluation vs placebo in the phase 3 INDEPENDENCE trial (Table 5), after the promising results of the phase 2 study.50 Among 34 patients with TI, 10% and 21% receiving luspatercept as a single-agent or RUX-combined achieved anemia response.50 Last data on 43 patients with TD showed that 10% and 27% of patients receiving luspatercept alone or RUX-combined met anemia response, lasting 49 and 42 weeks, respectively.51 In these cohorts, 37% and 46% of patients attained a ≥50% reduction in RBC-transfusion burden.51 Sotatercept, another TGFβ superfamily signaling inhibitor, allowed anemia response in 30% (single-agent) and 32% (RUX-combined) of 56 patients.52

KER050, a modified ActRIIA ligand trap, elicits effects on late and early erythroid progenitors and is on-study (Table 6).53 Knockdown, or loss of ALK2 that leads to decreased hepcidin production, is the mechanism of action of the oral small molecule ALK-2 inhibitor INCB000928 (Table 6).54 An alternative approach to reduce hepcidin overexpression is explored with DISC-0974, a humanized monoclonal antihemojuvelin (Table 6). Among JAKis, a recent report from the MOMENTUM study (Table 3) comparing MMB vs danazol in symptomatic patients with anemia showed that MMB attained a TI rate of 31%.55 This effect, already disclosed in the SYMPLIFY trials,56,57 is predictable as MMB inhibits JAK1/2 and ACVR1, the latter of which interfering with inflammatory-related hepcidin hyperproduction.

Clinical results of JAKis

The JAKis entered clinical practice: RUX and FEDR are approved by the Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency; PAC is Food and Drug Administration-approved, and this agency accepted the New Drug Application for MMB. Phase 3 trial results of JAKis in terms of efficacy and safety are listed in Table 3, mostly including intermediate-2/high-risk patients. Spleen volume reduction equal to or greater than 35% (SVR35) and total symptom score reduction equal to or higher than 50% (TSS50) from baseline to week 24 were mostly the main end points. No direct comparisons among JAKis exist, except for RUX vs MMB in the SYMPLIFY-1 trial.56 A meta-analysis showed that MMB and FEDR had comparable efficacy to RUX.58

To summarize the results in JAKi-naïve patients, SVR35 and TSS50, respectively, were met in 42% and 46% of RUX-treated,59 in 47% (36% with 4-week later confirmation) and 40% of FEDR-treated,60,61 in 19% each of PAC-treated (intermediate-1, 56%),62 and in 27% and 28% of MMB-treated patients (intermediate-1, 22%),56 and in 31% to 54% and in 57% to 70% of jaktinib-treated patients (intermediate-1, 33%).63

Survival effect of JAKis

When looking at data on JAKis and survival, doctors should consider that registration trials were not designed for studying this outcome as a primary end point and that matched-controlled studies have some known limitations (selection bias), as well as population-based registry studies (completeness and precision of the variables, unmeasured reasons for starting a treatment, interpretation of sequential treatments, ie, standard or investigative, post-JAKi discontinuation).

Long-term data from the COMFORT-I/II studies showed a 30% reduction of mortality in intermediate-2/high-risk patients vs controls.64 Progression-free survival was significantly prolonged with FEDR vs placebo in the JAKARTA trial.65 Long-term analysis of MMB in the SYMPLIFY-1 trial showed a robust 6-year survival of 56% and, of interest, an association between TI response and improved 3-year survival.66 When compared with danazol, MMB showed a trend toward improved survival up to week 24 in the MOMENTUM trial.55 In contrast, PAC- and BAT (best available therapy)–treated patients had similar survival in the very low–platelets setting.67

Management of splenomegaly in patients with pretreatment thrombocytopenia

Of note, no specific treatment for improving platelet count is available. Some patients experienced a platelet response with danazol (23%),45 and with pomalidomide (22%).48 Fostamatinib, a Syk inhibitor, is under evaluation to merely increase platelets (Table 6).

All JAKis are available for patients with platelets between 50 × 109/L and 100 × 109/L. Assessing SVR35, 17% of 66 RUX-treated patients met the outcome in a dose-escalation study (intermediate-1, 22%),68 36% of 14 FEDR-treated patients in a JAKARTA subanalysis,69 17% of 72 PAC-treated patients in a PERSIST-1 subanalysis,62 and 22% of MMB-treated patients in a MOMENTUM subanalysis (platelets below 150 × 109/L).70 Patients with platelets below 50 × 109/L are at high risk of bleeding and should not be considered for standard doses of RUX or FEDR, especially if PAC is available. The PACIFICA trial with PAC vs BAT is recruiting in this setting (Table 3). In the PAC203 study, a SVR35 has been achieved in 17% of 24 PAC-treated patients.71 Grade 3 to 4 thrombocytopenia occurred in 33% of patients, rarely leading to dose reduction or discontinuation (about 4% each).71 Of note, the platelet limit for enrollment in the MOMENTUM trial was 25 × 109/L, making MMB an alternative, if approved.55

Management of splenomegaly in patients with pretreatment anemia

All anemia-oriented treatments can be added to RUX to balance JAKi-related anemia with JAKi efficacy. The real challenge for today’s practice is the prevention of TD, which is not yet addressed in clinical trials. The REALISE study (intermediate-1, 17%) explored RUX in patients with anemia starting at 10 mg twice daily with up-titrations, achieving a 56% rate of ≥50% reduction in spleen length by week 24.72

New combinations in JAKi-naïve patients

Limited results with single-agent JAKi prompted a move toward new combinations in JAKi-naïve patients combining RUX with non–JAK-target inhibitors. Despite most of these studies have SVR35 as primary end point, the scientific community nowadays claims to look at modification in MF biology leading to survival benefit (disease-modification potential)73 or at least at a robust and sustained clinical response.

Small molecule pelabresib, navitoclax, and parsaclisib combined to RUX are under investigation vs RUX single-agent in the phase 3 MANIFEST-2, TRANSFORM-1, and LIMBER-313 trials, respectively (Table 4). All these trials have a 24-week SVR35 as their main end point. Results from phase 2 studies are available for the first 2 agents in this setting.74,75

Pelabresib, an oral BET inhibitor (BETi), was combined with RUX in the MANIFEST trial (arm 3).74 Within 84 patients (HMR, 55%; intermediate-1, 24%), SVR35 was attained in 68% (80% anytime) and maintained in 86%.74 In addition, hemoglobin improved, and TSS50 was reached in 56%.74 Grade 3 to 4 anemia and thrombocytopenia were reported in 34% and 12%, respectively.74 Besides the effect on several proinflammatory cytokines, the combination induced early modifications of BM morphology, such as ≥1 grade BMF improvement (28%), reduction of megakaryocytes (74%), increase of megakaryocyte distance (59%), and erythroid lineage (47%), all of which correlated with SVR.74

Navitoclax, an oral BCL-XL/BCL-2 inhibitor, was combined with RUX in the REFINE trial (arm 3).75 Within 32 patients (intermediate-1, 31%), SVR35 was met in 63% (78% anytime), 93% of whom maintained response at 1 year.75 TSS50 was reached in 41% of patients, and 40% of patients experienced anemia response anytime.75 Grade 3 to 4 anemia and thrombocytopenia were reported in 34% and 47% of patients, the latter being predictable and manageable (only 1 discontinued navitoclax).75 A ≥1 grade improvement in BMF was obtained in 27% (35% anytime).75

Switching RUX to second-line therapies

The best time to switch therapy has not been established because of the heterogeneous response to RUX and to the overall patient benefit despite signs of progression. In our practice, we switch therapy before RUX activity exhaustion despite dose adjustment, that is, if worsening of peripheral blood and blast cells, of spleen size, of symptoms or if persistence of a huge splenomegaly below 10 cm from left costal margin even having achieved spleen length reduction exceeding 50%.

Roughly half of patients discontinued RUX at 3 years, mostly for disease progression or side effects, with a subsequent survival of 13 months.77 Definition of progression or suboptimal response can include the IWGMRT criteria (worsening splenomegaly, BP)42 and/or worsening anemia, thrombocytopenia, leukocytosis, and the presence of some mutations.78 To identify predictors of worse survival after 6 months of RUX, a new model, named response to RUX after 6 months (RR6), was developed in the context of no additional JAKis.79 Calculating palpable spleen length, RBC transfusion need, and RUX dose at baseline, and after 3 and 6 months of treatment, the RR6 allows early stratification of survival thereafter.79

Clinical results of JAKis in JAKi-pretreated patients

Table 3 illustrates clinical trials with available results in this setting. FEDR was developed after RUX failure in the JAKARTA-2 study.80 A recent update with stringent criteria of RUX failure showed a 30% rate of SVR35 with a median DOR not reached, a TSS50 rate of 27%, and 1-year survival of 84%.65,81 This result represents a standard reference for the second-line setting. In addition, SVR35 was not significantly different between patients with platelets below or over 100 × 109/L.69 Thiamine testing and a mitigation plan for gastrointestinal toxicity are recommended to maintain safety. The FREEDOM 2 trial is exploring FEDR vs BAT (Table 3).

MMB was found to be nonsuperior to BAT for SVR35, whereas it was better for TSS50 (26%) in the SIMPLIFY-2 trial.57 However, secondary transfusion end points were improved, and to exploit this advantage, the MOMENTUM trial was developed, reaching SVR35 in 23% of patients.55 Grade 3 to 4 anemia and thrombocytopenia occurred in 61% and 28% of patients, respectively, and peripheral neuropathy occurred in 4% of patients after exclusion of subjects with peripheral neuropathy grade ≥2.55

Clinical results of non–JAKis as single agent or combined with RUX in JAKi-pretreated patients

Table 6 shows ongoing clinical trials. Navitoclax and parsaclisib each RUX-combined and imetelstat and navtemadlin as single agents are being assessed vs controls in phase 3 TRANSFORM-2, LIMBER-304, IMpactMF/MYF3001, and BOREAS trials, respectively, with different recruitment criteria (Table 5). IMpactMF has survival as primary end point, however randomizing imetelstat vs BAT (excluding JAKis).

In the REFINE study (arm 1a), 34 patients (58% HMR, 44% intermediate-1) received navitoclax added on to RUX.82 At week 24, SVR35 was achieved by 26% of patients (41% anytime), with a median DOR of 14 months, whereas TSS50 was achieved by 30%.82 Anemia response was achieved in 64%, ≥1 BMF grade improvement in 33%, and VAF reductions of 20% or greater in 28% of HMR and in 17% of non-HMR patients.82,83 Intriguingly, BMF- and VAF-responders live longer compared with nonresponders (median survival not reached vs 28 months), qualifying for a potential disease-modifying combination.83 As expected, thrombocytopenia was common, however reversible, without association to relevant bleedings.82 Navitoclax as monotherapy (arm 2) showed inferior results compared with the combination.84 Other antiapoptosis agents, such as the antagonist of inhibitor of apoptosis proteins (IAPs), SMAC-mimetic LCL-161, was studied in MF.85 Objective response was yielded in 30% of 50 patients, with reductions of IAPs in responders.85 Selinexor is under investigation, and among 12 patients (67% at HMR), 40% achieved SVR35.86

The next-generation PI3Kδ inhibitor parsaclisib was developed in an add-on phase 2 study in patients with RUX suboptimal response.87 The combination achieved at least SVR10 in half of the patients, whereas SVR35 was achieved in 9%, with new-onset grade 3 to 4 thrombocytopenia in 28%.87 In a subanalysis, 12% of patients with platelets 50 × 109/L to 100 × 109/L achieved SVR35.88

Imetelstat, an intravenous telomerase inhibitor, generated interest because, despite having a low efficacy in terms of SVR35 (10%) and TSS50 (32%), it disclosed promising biological effects in the IMbark trial.89 Higher dose imetelstat attained a ≥1 BMF grade improvement (41%), a ≥25% VAF reduction of driver mutations (42%), and a cytogenetic response (21%).89 Biological responders had a trend toward longer survival compared with nonresponders.89 Grade 3 to 4 thrombocytopenia, anemia, and neutropenia were reported in 41%, 39%, and 32% of patients, leading to infections in 37% and bleeding in 17%.89

Once-daily navtemadlin, an oral MDM2 inhibitor, yielded 24-week SVR35 and TSS50 in 16% and 30% of 25 patients, respectively, in the KRT-232-101 trial.90,91 The most common treatment-emergent events were diarrhea (62%), nausea (38%), thrombocytopenia (45%), and anemia (29%).90 Intriguingly, navtemadlin showed biological effects such as reduction of circulating CD34+ cells (87%), ≥20% VAF reduction of driver genes (34%), undetectable VAFs of driver/HMR genes (29%), and ≥1 BMF grade improvement (27%).91 Although these achievements correlated with SVR, no association were reported with survival yet.91

In the phase 2 MANIFEST trial, pelabresib was developed as a single agent (arm 1) or RUX-combined (arm 2).74,92,93 At week 24, the combination (86 patients, 8% intermediate-1) reached SVR35 and TSS50 in 20% and 37% of patients, respectively,74 conversion from TD to TI in 16%, and ≥1 BMF grade improvement in 26% (anytime in 39%).74,92 At week 24, monotherapy (86 patients, 8% intermediate-1) reached a 11% rate of SVR35, a 28% rate of TSS50, and a conversion from TD to TI in 16% of patients.93 Of interest, 71% of 7 patients with BMF improvement was found hemoglobin-responder.93 BET inhibition is considered a promising target in MF, with several molecules under investigation: ABBV-744, BMS-986158, and mivebresib (Table 6). The latter 2 are selective BETi designed to reduce off-target toxicity of pan-BETi.

The epigenetic modifier LSD1 is druggable by bomedemstat (IMG-7289-CTP-102 trial).94 Results in 89 patients (HMR, 42%) showed SVR20 in 28% and TSS50 in 24%, keeping hemoglobin stable in nearly 90% of patients.94 A rate of 31% and 48% of patients achieved ≥1 BMF grade improvement and a general VAF fall of 39%, mainly affecting JAK2 and ASXL1.94 Among epigenetic modifiers, panobinostat combined with RUX achieved a ≥50% spleen length reduction in 61% of patients without any biological effect.95

Microenvironment, as a target

BM microenvironment was targeted by PRM-151, a recombinant form of human pentraxin-2, achieving BMF decrease in one-quarter of patients with marginal effect on splenomegaly,96 and by alisertib, AURKA inhibitor, that failed clinical activity, despite restoring normal morphology and GATA1 expression of megakaryocytes.97 Targeting the biogenesis of connective tissue, LOXL2 inhibitors are under investigation as it is 9-ING-41, exploiting its selective GSK-3β inhibition properties to reverse pathological fibrosis (Table 6).

By neutralizing interleukin-1β-signaling, canakinumab, a human anti-IL-1β monoclonal antibody, is under investigation (Table 6). The beta-3 sympathomimetic agonist mirabegron, whereas failing JAK2-VAF reduction, showed signals of microenvironment modifications.98 Targeting BMF could be more effective for prevention in the early phases of MF than for intervention in the late phases.

Signaling pathways, as a target

Immunotherapies

Interferon (IFN) was extensively studied in MPNs. IFN-α achieved some degree of response in 15 of 30 patients with lower-risk MF and a spleen size reduction >50% in 4 out of 12 patients with splenomegaly exceeding 4 cm from the left costal margin.101 A study on 62 patients (53% at lower DIPSS risk) exposed to PEGylated IFN-α2a for a median time of 3.2 years reported a median survival from diagnosis of 7.2 years with 73% discontinuing treatment, approximately half for resistance and half for intolerance.102 More recently, the COMBI trial investigated PEGylated IFN-α2a plus RUX in 18 MF with a dropout rate of 32% at the end of 2 years.103 Although the clinical effect was marginal, reductions in JAK2-VAF were confirmed.103 The positioning of IFNs seems more plausible in the early phases of MF. To release the inhibition of immune responses, the PD-1/PD-L1 axis was investigated without interesting results for nivolumab (PD-1 inhibitor) and suspension for durvalumab (PD-L1 inhibitor, NCT02871323) and sabatolimab (TIM-3 inhibitor, NCT04097821). Among monoclonal antibodies, tagraxofusp, a CD123-targeted therapy,104 showed modest activity and elotuzumab, with SLAMF7-target, is under investigation.105 Finally, given the high immunogenicity of the CALR mutated–derived tumor-specific antigens, a phase I clinical vaccination trial with a CALR mutated-derived peptide was developed in 6 CALR-mutated MF.106 Despite a marked T-cell response, this vaccine was clinically not effective.106 A study on a mutant CALR-peptide–based vaccine is active (NCT05025488), and 1 with VAC85135, an off-the-shelf, viral vector–based cancer vaccine concurrently administered with ipilimumab, is recruiting (NCT05444530).

Stem cell transplantation

SCT is the only curative option for patients with MF: 1 out of 2 can be cured at 5 years.107 A recent study from the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research comparing retrospectively SCT vs non-SCT cohorts found a survival advantage with SCT beyond 1 year of treatment for patients with intermediate-1 or higher risk MF, but at the cost of early nonrelapse mortality.108

An international effort led by the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation and the European LeukemiaNet is currently revising the guidelines on SCT in MF.109

Some items on SCT are core questions in the daily practice: (1) Patients’ selection. Patients’ age is no longer considered a limit per se. To note, in a highly selected MF population (Karnofsky performance status <90% in 42%; hematopoietic cell transplantation–specific comorbidity index [HCT-CI] ≥3 in 30%) of 556 patients aged ≥65 years, the 5-year survival and nonrelapse mortality were 40% and 37%, respectively.110 An assessment of MF-related and post-SCT outcome is mandatory and should be properly communicated to potential candidates. It is acceptable to select patients with an expected survival lower than 5 years (ie, intermediate-2 and high-risk DIPSS or MYSEC-PM/ high-risk MIPSS-70; Figure 1).109,111 It is questionable whether to select those with an expected post-SCT survival lower than 5 years (ie, very high-risk Myelofibrosis Transplant Scoring System [MTSS],112Table 2; https://pmfscorescalculator.com); (2) Splenectomypre-SCT. A position paper from the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation was recently published.113 (3) Bridge therapy to SCT. Patients on RUX who achieved clinical improvement at SCT had a lower risk of relapse (8% vs 19%) and better 2-year event-free survival (69% vs 54%) compared with those who did not.114 Hence, we expect that improving clinical results with new combinations pre-SCT will be of value; and (4) Donor selection. Five-year probability of survival post-SCT was 56% with matched sibling donor, 48% with well-matched, and 34% with partially matched/mismatched unrelated in 233 patients with MF.107 Preliminary data on haploidentical transplant demonstrated its feasibility in patients without suitable HLA-matched donors.115

Conclusions

JAKis represent the first new option for MF management. As a limit, JAKis do not selectively target the mutated JAK2, and the on-target inhibition of wild-type JAK2 induces dose-limiting cytopenias. Most patients fail treatment for disease progression, and evolution to BP is not abrogated.

New molecules with alternative targets are under study. The scientific community is asked to design innovative trials, and we suggest some considerations. First, the study population should also include patients with early MF to test the possibility of preventing disease evolution: this requires many patients followed for a long time. Second, the control population of clinical trials must reflect the real world, including all currently available drugs: this can help doctors to better positioning approved new drugs. Third, to finally translate into benefit for patients, the primary outcome of clinical trials could evaluate survival or surrogate markers of survival. In the last 2 years, some agents or combinations have emerged with signals of disease modification. However, a word of caution in the interpretation of these results is needed as these are phase 2 studies enrolling limited patient numbers, no data from randomized clinical trials are yet available, and information on the maintenance of biological results over time and on long-term safety is lacking.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Alessandro Romano for developing the WEB calculator.

F.P. has been supported by grants from the Ministero della Salute, Rome, Italy (Finalizzata 2018, NET-2018-12365935, Personalized medicine program on myeloid neoplasms: characterization of the patient’s genome for clinical decision making and systematic collection of real-world data to improve quality of health care); by grants from the Ministero dell’Istruzione, dell’Università e della Ricerca, Rome, Italy (PRIN 2017, 2017WXR7ZT; Myeloid Neoplasms: an integrated clinical, molecular, and therapeutic approach); and by grants from Fondazione Matarelli, Milan, Italy.

Authorship

Contribution: F.P. and B.M. contributed to the conception and design of the review and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: F.P. received honoraria for lectures and advisory boards from Novartis, Bristol-Myers Squibb/Celgene, Sierra Oncology, AbbVie, Janssen, Roche, AOP Orphan, Karyopharm, Kyowa Kirin, and MEI. B.M. received honoraria for lectures from Novartis.

Correspondence: Francesco Passamonti, Department of Medicine and Surgery, University of Insubria, ASST Sette Laghi, Viale L. Borri 57, 21100 Varese, Italy; e-mail: francesco.passamonti@uninsubria.it.