Key Points

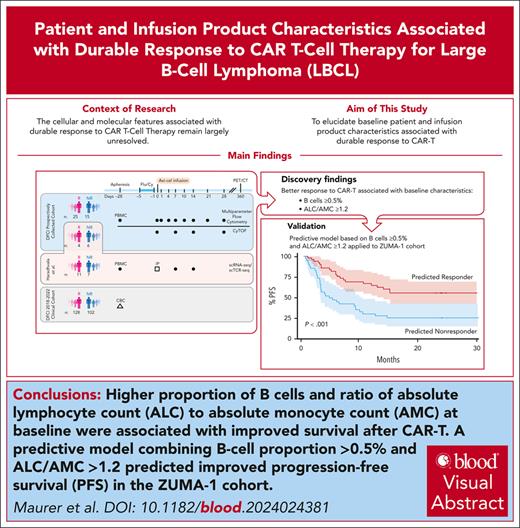

A lower circulating lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio and proportion of B cells at apheresis predict a reduced likelihood of response to CAR-T.

On exploratory analysis, axicabtagene ciloleucel products enriched for CD8 T effector memory cells were associated with durable response.

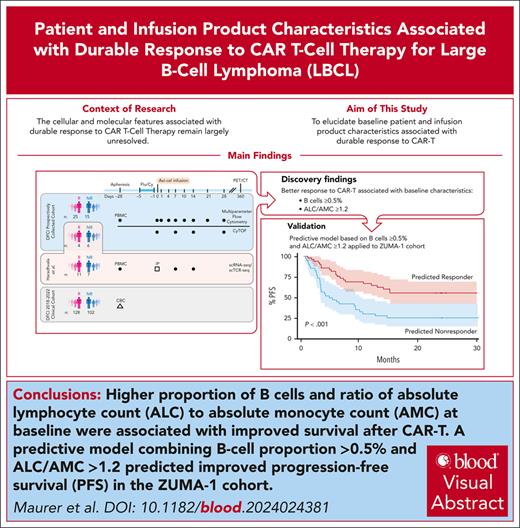

Visual Abstract

Engineered cellular therapy with CD19-targeting chimeric antigen receptor T cells (CAR-Ts) has revolutionized outcomes for patients with relapsed/refractory large B-cell lymphoma (LBCL), but the cellular and molecular features associated with response remain largely unresolved. We analyzed serial peripheral blood samples ranging from the day of apheresis (day –28/baseline) to 28 days after CAR-T infusion from 50 patients with LBCL treated with axicabtagene ciloleucel by integrating single-cell RNA and T-cell receptor sequencing, flow cytometry, and mass cytometry to characterize features associated with response to CAR-T. Pretreatment patient characteristics associated with response included the presence of B cells and increased absolute lymphocyte count to absolute monocyte count ratio (ALC/AMC). Infusion products from responders were enriched for clonally expanded, highly activated CD8+ T cells. We expanded these observations to 99 patients from the ZUMA-1 cohort and identified a subset of patients with elevated baseline B cells, 80% of whom were complete responders. We integrated B-cell proportion ≥0.5% and ALC/AMC ≥1.2 into a 2-factor predictive model and applied this model to the ZUMA-1 cohort. Estimated progression-free survival at 1 year in patients meeting 1 or both criteria was 65% vs 31% for patients meeting neither criterion. Our results suggest that patients’ immunologic state at baseline affects the likelihood of response to CAR-T through both modulation of the T-cell apheresis product composition and promoting a more favorable circulating immune compartment before therapy. These baseline immunologic features, measured readily in the clinical setting before CAR-T, can be applied to predict response to therapy.

Introduction

Chimeric antigen receptor T cells (CAR-Ts) targeting CD19 have transformed the treatment for relapsed/refractory large B-cell lymphoma (LBCL), with 43% 5-year overall survival for patients treated with axicabtagene ciloleucel (axi-cel) in the ZUMA-1 study.1 Despite these advances, treatment failure rates remain high,2-4 and improved molecular understanding of mechanisms of response are needed to understand the basis for sustained response, which could aid in patient selection and development of future therapies with greater activity.

Single-cell sequencing technologies have the potential to comprehensively evaluate heterogenous populations and provide unprecedented ability to track T-cell clonal kinetics, yet attempts using these approaches to identify patient- and CAR-T–intrinsic features linked to response have identified few clinically actionable biomarkers.5 We previously reported an analysis of 105 samples (infusion product [IP] and preinfusion and postinfusion peripheral blood mononuclear cells [PBMCs]) from 32 patients with LBCL treated with axi-cel (n = 19) or tisagenlecleucel (tisa-cel; n = 13) via single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) and single-cell T-cell receptor sequencing (scTCR-seq).6 We identified CD8+ memory T cells from IPs expanding in tisa-cel responders (Rs) but were not able to identify cell signatures in axi-cel Rs. Another study leveraged scRNA-seq of IPs from 24 patients with LBCL treated with axi-cel to identify transcriptional determinants of response.7 This study reported higher frequency of CD8+ central memory T cells in IPs of 3-month Rs vs nonresponders (NRs), but a follow-up study including additional patients did not confirm this finding.8 No studies have yet evaluated patient and IP characteristics associated with durable remission by scRNA-seq.

To ascertain the determinants of durable 1-year response in a large cohort of patients treated for relapsed/refractory LBCL with axi-cel, we prospectively collected serial PBMCs from 50 patients before and up to 28 days after axi-cel and IPs (available from a subset of patients; supplemental Table 1, available on the Blood website). Through multiparametric analyses consisting of scRNA-seq/scTCR-seq, prospectively collected real-time flow cytometry, and cytometry by time of flight (CyTOF) of circulating immune cell subpopulations and integration with large-scale internal and external data sets, we identified baseline B-cell number, lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio, and IP clonally expanded CD8 T effector memory (TEM) cells as potentially clinically actionable features predictive of CAR-T response.

Methods

Patient selection and sample preparation

Patients were treated with axi-cel as standard-of-care therapy for LBCL at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (DFCI) from 2019 to 2021. Patients provided informed consent for the collection and use of clinical data and samples on a research protocol approved by the institutional review board of Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center. “Rs” (n = 29) were defined as patients in complete response (CR; n = 28) or partial response (n = 1) at 1 year (Lugano9), whereas NRs (n = 21) had progressive disease by 1 year (supplemental Figure 1). IPs were collected by rinsing the infusion bag with phosphate-buffered saline to collect remaining cells, which were cryopreserved in a solution of 90% fetal bovine serum + 10% dimethyl sulfoxide until analysis. PBMCs were collected on the day of apheresis (approximately day –28) and posttreatment days 0, +4, +7, +10, +14, and +28 (supplemental Table 1). Fresh PBMCs were analyzed by multiparameter flow cytometry (LSRFortessa II) using 2 antibody panels to detect the following: (1) general range of immune markers (12 parameters); and (2) T-cell subsets (13 parameters; supplemental Table 2). CAR-Ts were identified by anti-Whitlow linker antibody (Kite, a Gilead company). Flow cytometry analysis was performed using FlowJo (BD Life Sciences). Cryopreserved PBMCs collected on days +7, +14, +21, and +28 were analyzed by CyTOF (supplemental Table 3).10 Clinical data from 230 patients receiving axi-cel at DFCI between 2018 and 2022 (Rs, n = 128; NRs, n = 102; excluding the 50 patients in the discovery cohort) were evaluated, including response (as defined above) and complete blood count with differential at day –28 (relative to CAR-T infusion), collected from an internal database of clinical patient information (research electronic data capture [REDCap]). We additionally evaluated clinical outcomes and baseline characteristics of patients from the ZUMA-1 cohort.1

Single-cell transcriptome library generation

Cryopreserved IPs and PBMCs were thawed, stained with cellular indexing of transcriptomes and epitopes by sequencing (CITE-seq) antibodies (supplemental Table 4),6 and resuspended in 0.04% bovine serum albumin (ThermoFisher) in phosphate-buffered saline at 1000 cells per μL before loading on a 10x Genomics Chromium instrument according to the manufacturer instructions. scRNA-seq libraries were processed using the Chromium single cell 5' library and Gel Bead kit v2 with coupled scTCR-seq library generation (Chromium single cell V(D)J enrichment kit [human T cell] [10x Genomics]) and sequenced (Illumina NovaSeq S4 platform). Amplified complementary DNA libraries and final sequencing libraries were assessed for quality control with a Bioanalyzer High Sensitivity DNA Kit (Agilent). CAR-T transcripts were detected by creating a custom reference and mapping to the CAR sequence.11 Details of data analysis are provided in supplemental Methods.

Results

Patient cohort characteristics

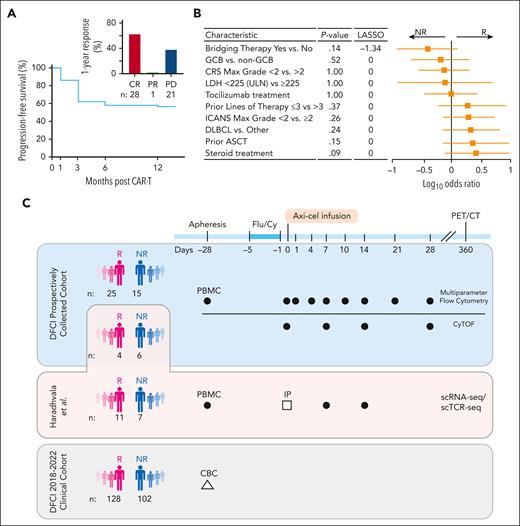

Of the 50 patients, 33 (66%) had a diagnosis of de novo diffuse LBCL, whereas 15 (30%) had transformed indolent disease (Table 1). One patient (2%) had unclassifiable high-grade BCL, and 1 had primary cutaneous LBCL, leg type. Forty percent (n = 20) were characterized as germinal center B-cell–like, whereas 36% (n = 18) had nongerminal center B-cell–like molecular subtype. Eight percent (n = 4) had “double hit” or “triple hit” lymphoma. Patients received a median of 3 lines of therapy before CAR-T (range, 2-9; not including bridging therapy). Thirty-one patients (62%) received bridging therapy between apheresis and CAR-T infusion.

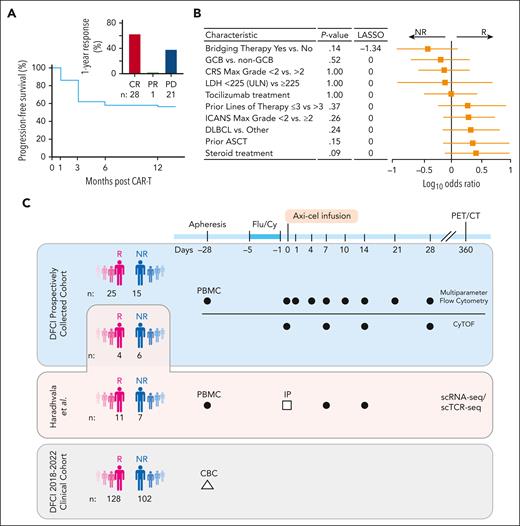

Progression-free survival (PFS) at 1 year was 58% (Figure 1A). Twenty-eight (56%) had a CR at 1 year, 1 (2%) had a partial response, and 21 (42%) had progressive disease (Figure 1A, inset; Table 1; supplemental Figure 1). Three patients included in the R group died of other causes before 1 year while in documented CR, and 4 others were lost to follow-up at our institution after their initial response assessment and were excluded in sensitivity analyses. R and NR groups had similar baseline and disease characteristics (Table 1; Figure 1B). Baseline tumor burden as estimated by median serum lactate dehydrogenase level at baseline (when available, fold-change = 1.30; P = .27; supplemental Figure 2A) and metabolic tumor volume (P = .57; supplemental Figure 2B) was not different between NRs and Rs.

Cohort description and study design. (A) PFS at 1 year of the prospectively collected 50-patient cohort. Bar graph of response at 12 months for this cohort (inset). (B) Forest plot of patient characteristics. P values (Fisher test) and LASSO coefficients shown comparing Rs vs NRs. (C) Schematic of the cohorts and sample collection of this study. Dark circles represent PBMCs; open square, infusion products (IPs); and open triangle, clinical complete blood count (CBC) with differential. ASCT, autologous stem cell transplant; CRS, cytokine release syndrome; DLBCL, diffuse LBCL; Flu/Cy, fludarabine and cyclophosphamide; GCB, germinal center B-cell–like; ICANS, immune effector cell–associated neurotoxicity syndrome; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; PET/CT, positron emission tomography–computed tomography; ULN, upper limit of normal.

Cohort description and study design. (A) PFS at 1 year of the prospectively collected 50-patient cohort. Bar graph of response at 12 months for this cohort (inset). (B) Forest plot of patient characteristics. P values (Fisher test) and LASSO coefficients shown comparing Rs vs NRs. (C) Schematic of the cohorts and sample collection of this study. Dark circles represent PBMCs; open square, infusion products (IPs); and open triangle, clinical complete blood count (CBC) with differential. ASCT, autologous stem cell transplant; CRS, cytokine release syndrome; DLBCL, diffuse LBCL; Flu/Cy, fludarabine and cyclophosphamide; GCB, germinal center B-cell–like; ICANS, immune effector cell–associated neurotoxicity syndrome; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; PET/CT, positron emission tomography–computed tomography; ULN, upper limit of normal.

Building a comprehensive single-cell atlas of immune cell states in relation to CD19+ CAR-T therapy

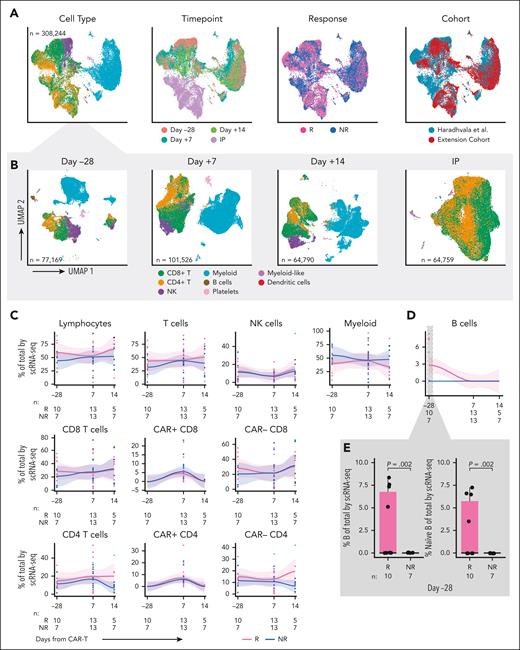

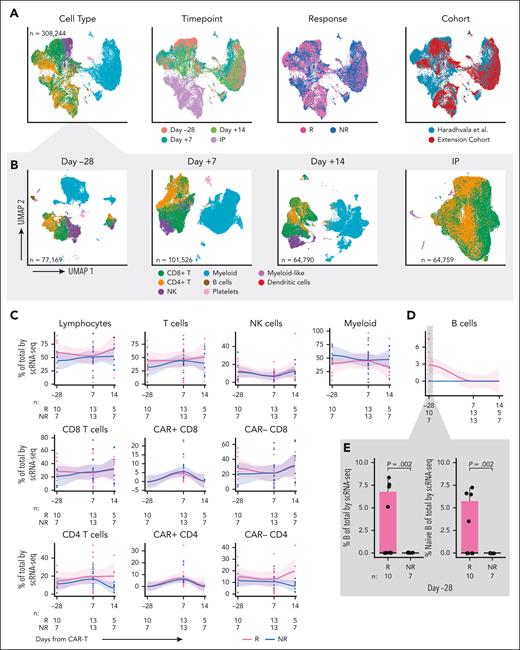

To increase the statistical power to detect cell populations associated with response, we generated scRNA-seq/scTCR-seq data from longitudinally collected PBMCs and IPs from 10 (4 Rs and 6 NRs) of the 50 patients in our prospectively collected cohort. Least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression demonstrated a lack of difference in baseline variables between the scRNA-seq patients and the remaining 40 patients, although power to detect differences may be limited (supplemental Table 5). A total of 87 432 high-quality single cells were merged with those from 18 axi-cel–treated patients (11 Rs and 7 NRs) previously reported from our institution11 that had been identically processed (ie, same center, same sequencing facility, and same time points; Figure 1C). For patients in that cohort, response was determined at 6 months after CAR-T. Updated 1-year outcomes were obtained when available (supplemental Table 6). Six patients classified as Rs at 6 months had incomplete follow-up at 1 year and were excluded in the sensitivity analysis. In total, we analyzed 308 244 single cells from 28 patients (15 Rs and 13 NRs), including 22 IPs and 17, 26, and 12 samples collected at days –28, +7, and +14, respectively.6 Major cell types were identified by clustering, and more granular labels were assigned by supervised annotation,12-14 then confirmed with manual annotation using a combination of gene expression profiles and scCITE-seq expression (eg, T central memory express more SELL/CD62L, CD27, and CD28 than TEM, whereas TEM was defined by expression of GZMB, IFNG, and other activation markers; Figure 2A). Although we observed some heterogeneity in composition across samples, overlap between the merged cohorts was excellent, with minimal evidence of batch effect by k-nearest neighbor batch effect test (kBET) silhouette15 and principal component regression (Figure 2A, right; supplemental Figure 2C; supplemental Table 7; supplemental Methods). As expected, the IPs consisted almost entirely of CD4 and CD8 T cells, whereas the composition of PBMCs varied across time points (Figure 2B).

Single cell RNA-sequencing of longitudinal patient samples. (A) Uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAPs) of the entire scRNA-seq data set (randomly subsampled for display due to the large number of cells) shaded by cell type (left), time point (second from left), response (second from right; Rs in pink vs NRs in blue), and cohort (right). (B) UMAPs showing cells by major cell type at day –28 (left), day +7 (second from left), day +14 (second from right), and IP (right). (C) scRNA-seq analysis of immune cell subset composition, including CAR+ and CAR– CD4 and CD8 cells, over time in Rs (pink) vs NRs (blue). Curves fit by loess smoother. Cells are denoted as CAR+ if at least 1 CAR transcript was detected. For a subset of samples from Haradhvala et al11 cohort at day +7, cells were sorted by flow cytometry for the CAR, in which case those designations are used. (D) scRNA-seq analysis of B-cell composition over time in Rs (pink) vs NRs (blue). (E) scRNA-seq analysis of B cells at day –28 (inset, left) and subsetted to naïve B cells (inset, right). NK cell, natural killer cell.

Single cell RNA-sequencing of longitudinal patient samples. (A) Uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAPs) of the entire scRNA-seq data set (randomly subsampled for display due to the large number of cells) shaded by cell type (left), time point (second from left), response (second from right; Rs in pink vs NRs in blue), and cohort (right). (B) UMAPs showing cells by major cell type at day –28 (left), day +7 (second from left), day +14 (second from right), and IP (right). (C) scRNA-seq analysis of immune cell subset composition, including CAR+ and CAR– CD4 and CD8 cells, over time in Rs (pink) vs NRs (blue). Curves fit by loess smoother. Cells are denoted as CAR+ if at least 1 CAR transcript was detected. For a subset of samples from Haradhvala et al11 cohort at day +7, cells were sorted by flow cytometry for the CAR, in which case those designations are used. (D) scRNA-seq analysis of B-cell composition over time in Rs (pink) vs NRs (blue). (E) scRNA-seq analysis of B cells at day –28 (inset, left) and subsetted to naïve B cells (inset, right). NK cell, natural killer cell.

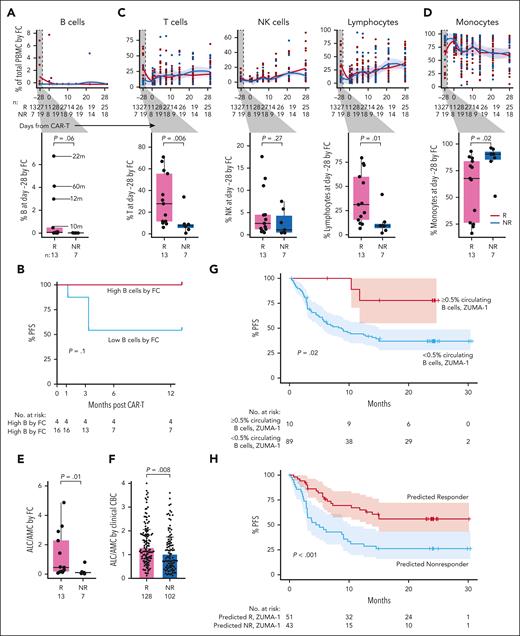

Baseline enrichment of circulating T and B cells and higher lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio mark CD19+ CAR-T Rs

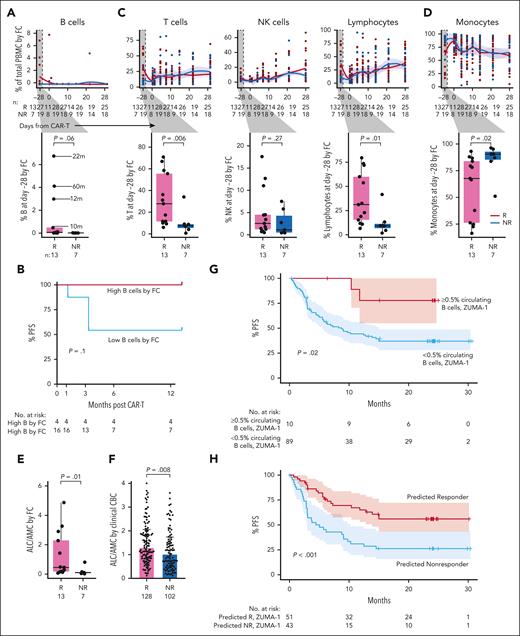

We observed no quantitative differences in postinfusion circulating immune subsets nor in CAR+ or CAR– CD4 or CD8 T-cell subsets over time between Rs and NRs (Figure 2C-D). Moreover, there were no differences between Rs and NRs regarding changes in CD4 and CD8 CAR+ and CAR– cell composition from baseline to day +7, baseline to day +14, or day +7 to day +14 (supplemental Figure 2D-E). However, we identified an increase at baseline (day –28) in the proportion of B cells in 10 Rs vs 7 NRs (P = .002; Figure 2E), characterized by a subset of Rs with a higher proportion of B cells. These comprised mostly naïve B cells (aligned to PBMCs reference).12 Sensitivity analysis excluding patients without full 1-year follow-up confirmed this finding (P = .001; supplemental Figure 3A). Consistent with these single-cell transcriptome–based findings, we detected a trend toward increased proportion (P = .06; Figure 3A, inset) and absolute number (P = .11; supplemental Figure 3B) of circulating B cells at baseline in Rs, based on surface protein expression of CD19 and immunoglobulin D (by flow cytometry on fresh PBMCs of 20 [13 Rs and 7 NRs] of our 50 patients for whom baseline data were available). We noted 4 patients had a higher proportion of circulating B cells than the rest of the cohort and noted that this subset trended toward improved PFS (P = .1; Figure 3B). The 4 patients with the highest baseline B cells had longer time since last therapy (22, 60, 12, and 10 months; Figure 3A; Table 2). Factor analysis indicated that longer time from therapy was the only variable detected in association with increased B-cell proportion (P = .005; supplemental Table 8). LASSO regression yielded an additional nonzero coefficient for diffuse LBCL diagnosis, but this was not significant under univariate testing (supplemental Table 8).

Flow cytometry analysis of longitudinal patient samples. (A) Flow cytometry (FC) analysis over time of total B cells in Rs (red) vs NRs (light blue). Time from last anti-CD20 directed therapy (in months) indicated by lines. P values by Wilcox. (B) Percent PFS for FC patients with higher baseline circulating B cells (red) compared with the remaining patients with lower baseline circulating B cells (blue). (C) FC analysis of T cells (left), NK cells (middle), and lymphocytes (right) before and after infusion; box plot of Rs vs NRs cell type proportions at day –28 (baseline; inset). (D) Percent of monocytes by FC in Rs vs NRs before and after infusion. (E) Ratio of ALC/AMC in Rs (red) vs NRs (blue) at day –28 measured by FC. (F) ALC/AMC at day –28 in all patients treated with commercial axi-cel at DFCI between 2018 and 2022, measured by clinical CBC with differential; Rs (pink; n = 128); NRs (turquoise; n = 102). (G) Percent PFS for ZUMA-1 patients with baseline circulating B cells ≥0.5% (pink) compared with patients with baseline circulating B cells <0.5% (light blue). (H) Percent PFS for ZUMA-1 patients predicted to respond based on baseline circulating B cells ≥0.5% or ALC/AMC ≥ 1.2 (pink) compared with patients predicted to not respond (ie, baseline circulating B cells <0.5% and ALC/AMC <1.2; light blue). NK cell, natural killer cell.

Flow cytometry analysis of longitudinal patient samples. (A) Flow cytometry (FC) analysis over time of total B cells in Rs (red) vs NRs (light blue). Time from last anti-CD20 directed therapy (in months) indicated by lines. P values by Wilcox. (B) Percent PFS for FC patients with higher baseline circulating B cells (red) compared with the remaining patients with lower baseline circulating B cells (blue). (C) FC analysis of T cells (left), NK cells (middle), and lymphocytes (right) before and after infusion; box plot of Rs vs NRs cell type proportions at day –28 (baseline; inset). (D) Percent of monocytes by FC in Rs vs NRs before and after infusion. (E) Ratio of ALC/AMC in Rs (red) vs NRs (blue) at day –28 measured by FC. (F) ALC/AMC at day –28 in all patients treated with commercial axi-cel at DFCI between 2018 and 2022, measured by clinical CBC with differential; Rs (pink; n = 128); NRs (turquoise; n = 102). (G) Percent PFS for ZUMA-1 patients with baseline circulating B cells ≥0.5% (pink) compared with patients with baseline circulating B cells <0.5% (light blue). (H) Percent PFS for ZUMA-1 patients predicted to respond based on baseline circulating B cells ≥0.5% or ALC/AMC ≥ 1.2 (pink) compared with patients predicted to not respond (ie, baseline circulating B cells <0.5% and ALC/AMC <1.2; light blue). NK cell, natural killer cell.

In line with our scRNA-seq findings, we did not detect any differences between Rs and NRs in any postinfusion immune cell populations, including CD4 or CD8 CAR+ or CAR– cells, by flow cytometry or CyTOF (Figure 3A,C,D; supplemental Figure 3C-E). However, baseline characterization by flow cytometry again revealed notable differences between response groups across immune cell subpopulations. First, percent of total lymphocytes (B, T, and natural killer cells) was increased in Rs vs NRs (median, 31% vs 9.4%; P = .01; Figure 3C, right inset). This was driven primarily by increased proportion and absolute number of T cells (Figure 3C; supplemental Figure 3B). The circulating immune milieu at baseline in Rs was enriched in CD4 and CD8 T cells, with several functional subsets increased in Rs vs NRs (supplemental Figure 4A). Second, and consistent with this finding, percent and absolute number of monocytes at baseline was decreased in Rs vs NRs (Figure 3D; supplemental Figure 3B). Sensitivity analysis redemonstrated enrichment of lymphocytes (P = .02) and a subset of patients trending toward enrichment of B cells (P = .07) in Rs and enrichment of monocytes among NRs (P = .02; supplemental Figure 4B). Third, because ratio of absolute lymphocyte count to absolute monocyte count (ALC/AMC) is associated with response in other lymphoma treatment settings,16-20 we calculated baseline ALC/AMC by flow cytometry and observed a higher ALC/AMC in Rs (n = 13) vs NRs (n = 7) (median, 0.46 vs 0.10; P = .01; Figure 3E), confirmed by sensitivity analysis (P = .02; supplemental Figure 4B). Factor analysis and LASSO regression did not identify other patient or treatment characteristics associated with increased ALC/AMC (supplemental Table 8). As further confirmation, we evaluated complete blood count/differential in our entire clinical cohort of patients treated with axi-cel at DFCI from 2018 to 2022 (Rs, n = 128; NRs, n = 102; excluding the 50-patient discovery cohort). Baseline ALC/AMC was again elevated in Rs vs NRs (median, 1.30 vs 1.02; P = .008; Figure 3F). We noted that ALC/AMC measured by complete blood count tended to be higher than that measured by flow cytometry for matched patients (supplemental Figure 4C-D).

To validate these features in association with response in an external cohort, we assessed baseline B-cell proportion among 99 patients from the ZUMA-1 cohort (Rs, n = 43; NRs, n = 56). A small but distinct subset of patients had ≥0.5% circulating B cells at baseline (n = 10), 80% of whom were in CR beyond 1 year after CAR-T, similar to our discovery cohort (P = .02, Fisher exact test; supplemental Figure 4E). The estimated PFS at 1 year for patients with ≥0.5% baseline circulating B cells was 77%, whereas the estimated 1-year PFS for patients with <0.5% B cells was 42% (P = .02; Figure 3G). We created and applied a 2-factor model to the ZUMA-1 cohort to determine the predictive ability for response of circulating B cells ≥0.5% or ALC/AMC ≥1.2. Five of 99 patients had incomplete data available and were excluded. Of the remaining 94 patients, the estimated PFS at 1 year for those meeting 1 or both criteria was 65%, whereas patients meeting neither criterion had an estimated PFS of 31% (P < .001; Figure 3H). Of the 94 patients, 10 met the B-cell criteria (3 of these also met the ALC/AMC criteria); 41 patients met only the ALC/AMC criteria; 43 patients met neither criterion (supplemental Figure 5A). Meeting the criteria of ALC/AMC ≥1.2 and B-cell proportion ≥0.5% were not directly associated with each other (supplemental Table 9; P = .33, Fisher exact test) and were thereby independent factors contributing to the model. To determine whether time from last therapy would predict response as well as B-cell proportion, we stratified the same set of patients by >6 months vs ≤6 months between last systemic therapy and CAR-T. Although patients with >6 months from last therapy trended toward improved PFS (P = .06; supplemental Figure 5B) in our small cohort, this was not observed in the larger ZUMA-1 cohort (P = .16; supplemental Figure 5C-D). Thus, the proportion of B cells and ALC/AMC at baseline appear to best predict durable response to CAR-T.

CAR-T response is associated with clonal expansion of highly activated CD8+ TEM cells from IPs

Because we detected evidence of immunologic differences at baseline between Rs and NRs and given that cells for the IPs were collected at this same time point, we asked whether differences in IPs contributed to therapy outcome. We interrogated CD4 and CD8 CAR+ and CAR– cell proportion from 22 IPs (14 Rs and 8 NRs), gene expression by scRNA-seq, and T-cell clonality using scTCR-seq. Very few differentially expressed genes were identified between Rs vs NRs in any IP T-cell subset (supplemental Table 10), and these genes were not suggestive of specific pathways related to T-cell activity that could explain response or resistance to therapy. Gene ontology (GO) term enrichment analysis did not identify any signatures of >3 genes for differentially expressed genes upregulated in CAR– CD8 T cells of Rs. For differential gene expressions upregulated in CAR– CD8 T cells of NRs, GO term enrichment analysis identified a few significantly upregulated pathways, but these did not clearly explain response (supplemental Table 11). Of note, nearly all these pathways included the gene CCL24, which was driven by very high expression in a single outlier patient.

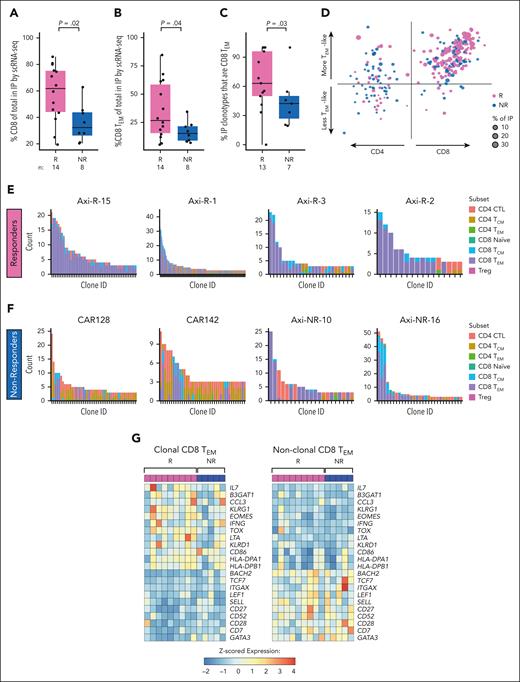

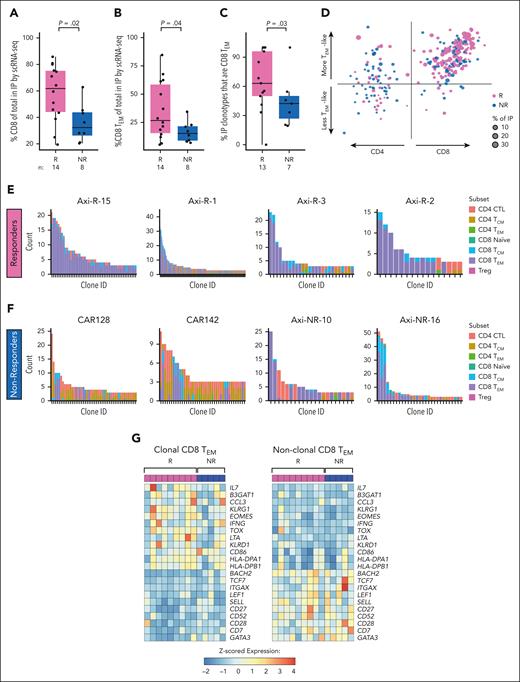

On the contrary, we found that IPs of Rs demonstrated increased CD8 T cells (median, 62% vs 32% in NRs; P = .02; Figure 4A). This difference was largely explained by greater CD8 T cells in which a CAR transcript was not detected (P = .03), with a slight increase in confirmed CD8+ CAR+ T cells (P = .26; supplemental Figure 7A-B). Accordingly, there was a trend toward enrichment of CAR+ CD4 cells in IPs of NRs (supplemental Figure 7C-D). No other differences in major cell subsets were observed in IPs (supplemental Figure 7E-F). When we assigned CD4 and CD8 T cells to functional subsets, based on gene expression profiling using a PBMC reference and compared with expression profiles of 4 recent scRNA-seq analyses of CAR-T data (supplemental Figure 6),7,21,22 we found increased CD8 TEM cells (expressing CCL5, GZMB, GZMK, and IFNG; median, 27% vs 15% of IPs; P = .04; Figure 4B).

Single cell T cell receptor clonality and functinonal state in infusion products. (A) Proportion of CD8 T cells in IPs of Rs (pink) vs NRs (blue) by scRNA-seq. (B) Proportion of CD8 TEM cells in IPs of Rs (pink) vs NRs (blue) by scRNA-seq. (C) Proportion of sets of clonally expanded cells (“clonotypes”) in IPs that have majority CD8 TEM phenotypes of R (pink) vs NR (blue) by scRNA-seq. Cells are considered clonally expanded if there are >2 cells sharing the same TCR CDR3 sequence. (D) Scatterplot of T-cell clonotypes of Rs (pink) and NRs (blue) by subset: CD4 (left) or CD8 (right) and more effector memory (upward arrow) vs less effector memory/more central memory (downward arrow). The CD4 vs CD8 score is computed as the difference between mean normalized CD8A gene expression and mean normalized CD4 gene expression among the cells in each clonotype. The effector memory score is computed as the mean normalized expression of the genes GZMA, GZMB, GZMH, GZMK, GZMM, PRF1, GNLY, IFNG, and TNF in each clonotype. Up to the largest 25 clones for each patient are shown. (E-F) Histograms of top expanded T-cell clones and their respective T-cell subsets for 4 representative Rs (E) and NRs (F). In the x-axis, each bar represents an individual clone; y-axis, number of members of each clone (“count”). CD8 TEM are shown in purple. (G) Differential gene expression analysis of clonally expanded (left) vs nonclonally expanded (right) CD8 TEM cells in the IP, pseudobulked, and normalized by patient and labeled subset. Patients with <30 cells of either clonally expanded or nonclonally expanded CD8 TEM cells were excluded. Treg, regulatory T-cell.

Single cell T cell receptor clonality and functinonal state in infusion products. (A) Proportion of CD8 T cells in IPs of Rs (pink) vs NRs (blue) by scRNA-seq. (B) Proportion of CD8 TEM cells in IPs of Rs (pink) vs NRs (blue) by scRNA-seq. (C) Proportion of sets of clonally expanded cells (“clonotypes”) in IPs that have majority CD8 TEM phenotypes of R (pink) vs NR (blue) by scRNA-seq. Cells are considered clonally expanded if there are >2 cells sharing the same TCR CDR3 sequence. (D) Scatterplot of T-cell clonotypes of Rs (pink) and NRs (blue) by subset: CD4 (left) or CD8 (right) and more effector memory (upward arrow) vs less effector memory/more central memory (downward arrow). The CD4 vs CD8 score is computed as the difference between mean normalized CD8A gene expression and mean normalized CD4 gene expression among the cells in each clonotype. The effector memory score is computed as the mean normalized expression of the genes GZMA, GZMB, GZMH, GZMK, GZMM, PRF1, GNLY, IFNG, and TNF in each clonotype. Up to the largest 25 clones for each patient are shown. (E-F) Histograms of top expanded T-cell clones and their respective T-cell subsets for 4 representative Rs (E) and NRs (F). In the x-axis, each bar represents an individual clone; y-axis, number of members of each clone (“count”). CD8 TEM are shown in purple. (G) Differential gene expression analysis of clonally expanded (left) vs nonclonally expanded (right) CD8 TEM cells in the IP, pseudobulked, and normalized by patient and labeled subset. Patients with <30 cells of either clonally expanded or nonclonally expanded CD8 TEM cells were excluded. Treg, regulatory T-cell.

We further interrogated the clonal distributions of T-cell subsets between Rs and NRs. By scTCR-seq, a greater proportion of expanded clonotypes in Rs consisted of predominantly CD8 TEM phenotypes than in NRs (Figure 4C-F; supplemental Figure 7G-H; Supplemental Methods). Sensitivity analysis demonstrated similar trends (supplemental Figure 7I-J). Clone tracking over time demonstrated that most expanding clones retained their original state (eg, a TEM remained a TEM) rather than differentiating (supplemental Figure 8A-B). Differential gene expression of clonally expanded vs nonexpanded CD8 TEM cells revealed an increased expression of genes associated with T-cell activation within the clonally expanded subset (IFNG, TOX, KLRG1, B3GAT1, and multiple HLA-class II genes; Figure 4G). scCITE-seq confirmed increased expression of CD57 (encoded by B3GAT1) in expanded compared with nonexpanded CD8 cells (supplemental Figure 8C). Sensitivity analysis excluding 1 patient with high KLRG1 expression across all cells redemonstrated higher KLRG1 expression among clonally expanded cells (supplemental Figure 8D-E). Nonclonal cells expressed genes associated with a stem cell memory–like (TSCM) signature (eg, TCF7, BACH2, SELL, CD27, and CD28; Figure 4G).23

Discussion

The search for predictive factors of CAR-T response is an active area of investigation. Our scRNA-seq/scTCR-seq cohort is, to our knowledge, the largest study to date of longitudinally collected samples from axi-cel–treated patients (n = 28). By merging the samples with those from our previously characterized cohort,6 we were able to perform more sensitive discovery analyses to uncover several novel associations, with protein-level confirmation on a larger prospective cohort with multiparameter flow cytometry and CyTOF. We further confirmed these findings in an independent large-scale clinical cohort from our center. Finally, we leveraged these baseline findings to validate a predictive model for durable CR after axi-cel using the ZUMA-1 cohort data. Our major findings, as described below, can be easily recapitulated in routine clinical practice using readily available clinical laboratory tools.

Our first key finding was the remarkable overall similarity in the circulating cell subset proportions reconstituting over time after CAR-T between durable Rs and NRs, which we observed consistently across our flow cytometry, CyTOF, and scRNA-seq data platforms. This lack of quantitative or qualitative differences in the postinfusion time period for circulating immune cells between response groups led us to consider whether baseline immunologic features could distinguish clinical response. We found significant differences in T- and B-cell proportions and absolute numbers between Rs and NRs. Patients with circulating B cells were further temporally removed from therapy, which may account for the difference in the circulating immune compartment before CAR-T. One hypothesis for this association is that the presence of circulating B cells promotes T-cell fitness, resulting in an improved CAR-T product, perhaps through costimulatory activity of healthy B cells on T cells during manufacture. Preclinical and early-stage studies suggesting vaccination to tumor-associated antigens before CAR-T may enhance efficacy, supporting a role for the host immune system in promoting CAR-T activity.24,25 Alternatively, the need for lymphoma-directed therapy leading up to apheresis and CAR-T infusion may indicate more aggressive disease biology. Intriguingly, a recent study of pretreatment tumor characteristics of patients treated on the phase 3 ZUMA-7 trial found a B-cell gene expression signature associated with improved event-free survival.26 Another potential hypothesis to explain this finding as well as our own is that increased B cells could lead to greater CD19 antigen burden, which has previously been implicated with durable response.27 We also found a strong association between elevated baseline ratio of ALC/AMC and durable response. Elevated ALC/AMC has previously been positively associated with response in other lymphoma treatment settings,16-20 and our findings are in agreement with a recent report of elevated monocytes at leukapheresis predicting poor outcome after CAR-T.28 One potential explanation is increased AMC due to elevated myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) with tumor-infiltrating potential, which may promote tumor growth and proliferation.29 Indeed, prior studies have linked higher abundance of circulating MDSCs before and after CAR-T infusion to treatment failure, possibly resulting from MDSC-mediated suppression of CAR-T expansion after infusion.30,31 More recently, increased monocytes at apheresis and a monocyte gene signature in IP T cells have been associated with early disease progression after CAR-T.32 Notably, we demonstrated that patients in ZUMA-1 with higher proportion of circulating B cells or ALC/AMC have greater likelihood of response. These features appear to independently predict good outcomes, although the mechanisms underlying these observations require further inquiry. In our current patient cohort, we did not have the ability to examine the tumor microenvironment, in which features distinguishing response may be clearer, which is an interesting area of future study.

Second, we observed that IPs from Rs were enriched for CD8+ T cells (notably CD8 TEM cells) compared with NRs, distinct from the responder-enriched CD8 population described previously in study by Deng et al.7 The same group recently reported an updated analysis of the original data set along with additional patients.8 This new analysis (Li et al8) did not find an association of specific cell clusters with response as reported by Deng et al. However, the Deng et al7/Li et al8 cohort differed from ours in focusing on short-term response (ie, 3 months) vs long-term durable response (our study). This difference in response definition limits direct comparison between the studies.

Using scTCR-seq, we identified increased expanded clonotypes of predominantly CD8 TEM phenotype in IPs of Rs compared with NRs. Our finding is supported by prior work using T-cell clone tracking that demonstrated that postinfusion clonally expanded T cells tended to originate from effector/cytotoxic clusters within the IP.33 Another recent study found that “successful” CAR-Ts (ie, those with better tumor-homing and proliferative/cytotoxic capacity) tended to have an effector phenotype in the IP.34 Other efforts to select specific T cells for CAR-T manufacture are currently in progress,35 and our data highlight the TEM cells as a potential candidate population for these efforts. A previous study demonstrated that enrichment of activated CD8 T cells in the pretreatment tumor microenvironment was associated with better durable response to axi-cel, in agreement with our findings.36 Other groups have evaluated axi-cel premanufacture apheresis products by multiparameter flow cytometry and found a higher proportion of naïve CD4 T cells among Rs; this association was strongest with objective response, whereas the proportion of naïve CD4+ T cells was similar between durable Rs and NRs at 24 months.30,37 Our analysis did not include the premanufacture apheresis product, limiting direct comparison with these prior studies. Other studies have implicated CAR-Ts generated from CD8 TSCM cell subsets as having greater proliferative and antitumor capacity than TEM subsets,38-40 including 1 notable study (Dickinson et al) with a CD19-directed CAR-T demonstrating enhanced stemness, which has shown promising safety data and response rates.41 Wilson et al describe differentiation trajectories for pre-IP T cells that distinguish the ability to become functional effectors in patients after infusion, in contrast to our findings suggesting stable functional profiles across time; however, this study was also in a pediatric population, which may differ substantially in baseline immune repertoire.21 However, a previous study found that enriching for T central memory cells in the IP did not influence outcome.42 We note that these prior studies of TSCM CAR-Ts used a CAR-T construct with a 4-1BB costimulatory domain (such as for tisa-cel), whereas the axi-cel construct contains CD28 as a costimulatory molecule. Indeed, our prior work and other studies have found marked differences in transcriptional profiles, differentiation trajectories, and drivers of dysfunction between CAR-Ts containing distinct costimulatory domains.6,11,21,43,44

Based on this study with external validation in ZUMA-1, both ALC/AMC and presence of B cells at baseline could be used to aid in prognostication of patients before CAR-T. These widely available measures may be even more useful if incorporated into prognostic scores that capture other patient- and disease-related characteristics. This observation highlights a subset of patients at higher risk of treatment failure, underscoring the need for further investigation into mechanisms of resistance for this population. Furthermore, our results support the ongoing use of single-cell sequencing techniques to refine our understanding of the key cellular populations that provide durable antitumor activity and their clonal evolution over the initial postinfusion period. Ultimately, this could facilitate the creation of more effective cellular therapy products for patients with LBCL.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank S. J. Rodig, E. M. Parry, and C. K. Hahn for providing critical comments on the manuscript. The authors thank the Ted and Eileen Pasquarello Tissue Bank and Doreen Hearsey for prospective collection and processing of serial blood samples and the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute/Harvard Cancer Center cellular therapies support staff for continued care of chimeric antigen receptor T-cell patients.

Funding for this study was provided by Kite, a Gilead company. K.M. received support from the American Society for Clinical Oncology Young Investigator Award, the Svenson Family Fellowship, and the Lubin Family Foundation. I.N.G. is supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship (grant DGE1745303). R.A.I. received research support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Institute of General Medical Sciences (grant R35GM131802) and the NIH, National Human Genome Research Institute (grant R01HG005220). S.L. is supported by the NIH, National Cancer Institute Research Specialist Award (R50CA251956). P.A. acknowledges the support of the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society as well as the Harold and Virginia Lash Foundation. C.J.W. is Lavine Family Chair for Preventative Cancer Therapies.

Authorship

Contribution: K.M., S.H.G., R.H., J.R., C.J.W., P.A., and C.J. conceived and designed the study; K.M. and S.H.G. identified, collected, and interpreted patient information; K.M., S.H.G., R.H., Y.A., and S.M. designed and performed experiments; H.J. performed metabolic tumor volume quantification; C.R. and M.A. performed flow cytometry data acquisition; K.J.L., S.L., W.L., and H.L. generated single-cell RNA sequencing data; R.R. performed statistical analysis; K.M. and I.N.G. designed, performed, and interpreted data analysis; and all authors participated in manuscript writing and review and provided final approval of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: C.J. reports consultancy fees from Kite/Gilead, Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS)/Celgene, Novartis, Instil Bio, ImmPACT Bio, Caribou Bio, Miltenyi, Ipsen, ADC Therapeutics, AbbVie, AstraZeneca, MorphoSys, Synthekine, and Sana; and research funding from Kite/Gilead and Pfizer. C.J.W. holds equity in BioNTech Inc and receives research funding from Pharmacyclics. S.H.G. holds patents related to adoptive cell therapies, held by University College London (UCL) and NovalGen Limited; has received honoraria, speakers’ fees, and travel support from and/or served on advisory boards for AbbVie, BeiGene, Gilead, EUSA/Recordati, Electra Pharma, and Janssen; and has undertaken consultancy and hold patents with Freeline Therapeutics, NovalGen, and UCL Business. R.H. reports honoraria from Kite/Gilead, Novartis, Incyte, Janssen, MSD, Takeda, and Roche; and consultancy fees from Kite/Gilead, Novartis, BMS/Celgene, ADC Therapeutics, Incyte, and Miltenyi. P.A. provides consultancy for Merck, BMS, Pfizer, Affimed, Adaptive, Infinity, ADC Therapeutics, Celgene, MorphoSys, Daiichi Sankyo, Miltenyi, Tessa, GenMab, C4, Enterome, Regeneron, Epizyme, AstraZeneca, Genentech/Roche, Xencor, Foresight, and ATB Therapeutics; and receives research funding from Kite, Merck, BMS, Adaptive, Genentech, IGM Biosciences, and AstraZeneca. J.R. received research funding from Kite/Gilead, Novartis, and Oncternal; and serves on scientific advisory boards for Garuda Therapeutics, LifeVault Bio, Smart Immune, and TriArm Therapeutics. H.J. receives research support (to institution) from Blue Earth Diagnostics Inc and Lantheus; provides consultancy for Advanced Accelerator Applications and Spectrum Dynamics; receives royalties from Cambridge Publishing; and receives honoraria from Blue Earth Diagnostics Inc and Monrol. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Caron Jacobson, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, 450 Brookline Ave, Boston, MA 02215; email: caron_jacobson@dfci.harvard.edu.

References

Author notes

K.M., I.N.G., R.H., and S.H.G. contributed equally to this study.

C.J.W. and C.J. contributed equally to this study.

The data reported in this article have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus database (accession number GSE273170). Single-cell transcriptome and T-cell receptor sequencing data will be deposited to the National Center for Biotechnology Information’s Database of Genotypes and Phenotypes and will be made publicly available by the date of publication (available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gap; accession number phs002922.v2).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.