Abstract

Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF ) and tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) have been implicated in the pathogenesis of the fatal childhood disease termed juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia (JMML). We used a severe combined immunodeficient/nonobese diabetic (SCID/NOD) mouse model of JMML and examined the effect of inhibiting these cytokines in vivo with the human GM-CSF antagonist and apoptotic agent E21R and the anti-TNFα monoclonal antibody (MoAb) cA2 on JMML cell growth and dissemination in vivo. We show here that JMML cells repopulated to high levels in the absence of exogeneous growth factors. Administration of E21R at the time of transplantation or 4 weeks after profoundly reduced JMML cell load in the mouse bone marrow. In contrast, MoAb cA2 had no effect on its own, but synergized with E21R in virtually eliminating JMML cells from the mouse bone marrow. In the spleen and peripheral blood, E21R eliminated JMML cells, while MoAb cA2 had no effect. Importantly, studies of mice engrafted simultaneously with cells from both normal donors and from JMML patients showed that E21R preferentially eliminated leukemic cells. This is the first time a specific GM-CSF inhibitor has been used in vivo, and the results suggest that GM-CSF plays a major role in the pathogenesis of JMML. E21R might offer a novel and specific approach for the treatment of this aggressive leukemia in man.

JUVENILE MYELOMONOCYTIC leukemia (JMML), also known as juvenile chronic myelogenous leukemia or chronic myelomonocytic leukemia, is a rare childhood malignancy with high mortality.1,2 This myelodysplastic disorder affects the bone marrow initially by suppressing normal hematopoiesis, and an excessive proliferation of immature myeloid cells is a frequent finding. A large number of leukemic progenitor cells exit the bone marrow and the malignant process disseminates to both the spleen and liver, with many patients dying ultimately of pulmonary infiltration. With regard to treatment, chemotherapy has given disappointing results,3,4 and durable remission may only be obtained following bone marrow transplantation, however, more than half of the transplanted patients relapse.5 6

There is strong evidence that the multifunctional cytokine granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF ) markedly promotes proliferation and survival of JMML cells, and thus contributes to the aggressive nature of this malignancy.7-12 Contrary to other leukemias that usually require exogeneous cytokines for their proliferation in vitro, the high spontaneous formation of JMML colonies probably stems from dysregulated autocrine production of and sensitivity to GM-CSF. This is supported by the ability of anti–GM-CSF antibodies to inhibit colony formation of JMML cells.7,9,13 It is also consistent with JMML patients exhibiting pathologic features similar to those in transgenic mice overexpressing GM-CSF.14

We have developed a GM-CSF analogue (E21R) that carries a single point mutation at position 21 in which glutamic acid has been substituted for arginine. This second generation GM-CSF molecule effectively antagonizes GM-CSF in binding experiments and in functional assays.15 Recently, we showed that E21R specifically abolishes growth of JMML cells by inducing apoptosis (programmed cell death) in vitro, suggesting that E21R may have a therapeutic potential in JMML.13

Emerging evidence suggests that tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) might also contribute to the leukemic process by enhancing JMML cell growth, as well as by suppressing normal hematopoiesis.7,13 Possibly the growth-promoting action of TNFα results from stimulation of GM-CSF production, and hence may be considered to act upstream of GM-CSF activation.7,13,16 Interestingly, anti-TNF antibodies also reduce JMML growth and restore colony formation of normal bone marrow cells in vitro.7,13 An effective inhibitor of TNFα is the chimeric mouse/human anti-TNFα MoAb cA2, which neutralizes TNFα-mediated functions both in vitro17 and in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.18

Interleukin-1 has been implicated as a pathogenic factor in JMML, but its role has been challenged.7 13

In vivo models of various leukemias including JMML have been established using irradiated mice carrying the SCID mutation.19 20 To examine the relative importance of GM-CSF and TNFα in vivo, we engrafted primary JMML cells into irradiated severe combined immunodeficient/nonobese diabetic (SCID/NOD) mice and tested the effect of blocking them with the specific antagonists E21R and MoAb cA2 on leukemic engraftment, proliferation, and dissemination in these mice. The results show that GM-CSF is a major factor responsible for the proliferation of JMML cells and that E21R very effectively reduces growth and dissemination of this aggressive childhood leukemia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Donor samples. The protocol was approved by ethics committees. We studied 10 children diagnosed with JMML according to the International Juvenile Myelomonocytic Leukemia Working Group (Table 1). Three healthy children (age, 3 to 5 years) were included as controls.

Parental consent was given to use bone marrow and extirpated spleens, and a suspension of mononuclear cells was prepared from the samples after dextran sedimentation of erythrocytes and using density centrifugation as previously described.13 Using MoAbs raised against both subunits of the GM-CSF receptor and the p55/p75 TNFα receptors and flow cytometry, we found that these receptors were present on >99% of the cells in each of the 10 JMML cases, and on about 50% of the bone marrow cells in each of the three controls.

Before transplantation, the JMML cells and the normal bone marrow cells were kept in liquid culture as described.13

Preparation of SCID/NOD mice for transplantation with human bone marrow cells. We used SCID/NOD mice aged 4 to 6 weeks that were bred and maintained in a specific pathogen-free environment. Under general anesthesia (25 mg/kg, pentobarbital intravenously) and with sterile procedures, a mini-osmotic pump (0.25 μL/hour, Alzet, Palo Alto, CA) was placed into the peritoneal cavity either on day 1 or 4 weeks after transplantation of cells. The pump was filled with either isotonic saline or the GM-CSF mutant E21R (0.5 mg/day; BresaGen, Adelaide, SA, Australia) and/or the neutralizing anti-TNFα MoAb cA2 in a F(ab)2 form21 (0.25 mg/day; Centocor, Malvern, PA). With this procedure, a continuous amount of both E21R and MoAb cA2 was delivered to the mice throughout the experimental period, the steady-state plasma concentrations of E21R and MoAb cA2 being approximately 20 μg/mL and 10 μg/mL, respectively. On day 1 and immediately before transplantation of cells, the mice were irradiated with 200 cGy. We then injected 2 to 3 × 107 JMML cells or normal bone marrow cells (intravenously) on days 1 and 3.

Production of E21R. Recombinant E21R was produced in E. coli as a fusion protein containing the amino acid sequence Met-Phe-Ala-Thr-Ser-Ser-Thr-Gly-Asn-Asp-Gly fused to the N-terminus of GM-CSF(E21R). Inclusion bodies containing E21R were dissolved and refolded in 3 mol/L urea (pH, 11.5). At the completion of refolding, the pH was adjusted to 9.1 and the correctly folded E21R was purified by ion-exchange chromatography on Q-Sepharose (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden). Purified E21R was desalted into 5 mmol/L Na2HPO4 (pH, 7.6; Sephadex G-25M, Pharmacia) and quantitated by its absorption at 280 nm using a 280A of 9.09. Following quantitation, 1 part of glycine and 5 parts mannitol were added. The formulated solution was filtered before lyophilization in sterile glass vials. Purified E21R was shown to be > 95% pure as judged by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE).

Drugs and treatment protocol. Groups of five transplanted mice were allocated to receive treatment for 4 weeks with either saline (untreated), or E21R, or MoAb cA2, or a combination of the E21R and MoAb cA2; and either from day 1 (early treatment) or from 4 weeks (late treatment) after transplantation.

Three separate mice were each transplanted with male JMML cells and female normal bone marrow cells simultaneously and received early treatment.

The mice were killed with an overdose of pentobarbital (intraperitoneally). We killed the untreated mice and mice receiving early treatment (from day 1) no later than 6 weeks after transplantation. Mice receiving late treatment (starting 4 weeks posttransplant) were killed no later than 4 weeks after the start of treatment (8 weeks posttransplant). For ethical reasons, long-term survival of the mice could not be examined.

Determination of engraftment of human cells into SCID/NOD mice. A quantitative assessment of human cell contents in the recipient mouse bone marrows was performed with Southern blotting as detailed elsewhere.22 Briefly, DNA was extracted with organic solutions and digested with EcoR1, blotted, and then labelled with a probe (p17H8) that specifically recognizes DNA sequences on human chromosome 17. The percentage of human DNA present in the marrow was estimated by comparing the intensity of a characteristic 2.7-kb band with standard human/mouse DNA mixtures using a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA).

In separate experiments, we used a fluorescent in-situ hybridization method to determine the fraction of human cells engrafted within bone marrow of transplanted mice.23 Human female and male cells were detected using probes specific for the alpha satellite regions of the X and Y chromosomes (Boehringer Mannheim, Castle Hill, New South Wales, Australia), respectively, and there was no cross hybridization with mouse cells. Cell nuclei were counterstained with propidium iodide (Sigma, Castle Hill, New South Wales, Australia). In each experiment, we counted 300 bone marrow cells.

Infiltration of human cells into mouse spleens was estimated in splenic cell-solutions with a human specific anti-CD45 MoAb (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA) and an EPICS-Profile II Flow Cytometer (Coulter Electronics, Hialeah, FL). An irrelevant isotype-matched IgG was used as a negative control.

We used a reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) to detect human cells in mouse peripheral blood. Briefly, RNA was extracted and cDNA was made using standard procedures. We then assessed the cDNA for base sequences corresponding to the human-specific βc subunit of the GM-CSF receptor. The following oligonucleotide primers were used: β1, 5′-AGC AAG ACC GAG ACC CTC CAG AAC GCA CA-3′; and β5, 5′-ACT CCC GCT AGT GAA GGC CGA CAT GC-3′.

cDNA (5 μg) was added to 45 μL of PCR mixture consisting of MgCl2 (2 mmol/L), PCR buffer (Perkin Elmer, Branchburg, NJ), β1/β5 primers (0.2 μmol/L), deoxyribonucleotides (0.0625 mmol/L each), and Taq DNA-polymerase (20 U/mL, Perkin Elmer). The samples were preheated for 3 minutes at 94°C before the amplification. The PCR was performed on a PE Cetus DNA thermal cycler for 35 cycles composed of 40 seconds denaturation at 94°C, 40 seconds annealing at 65°C, and 50 seconds extension at 72°C. The amplified product (363 bp) was electrophoresed on a 2% agarose gel and visualized with ethidium bromide under ultraviolet light. Mouse RNA was used as a negative control.

Phenotyping of engrafted human cells. Cells collected from the femoral bone marrow and the spleen of transplanted mice were stained with an anti-CD45 MoAb and sorted with flow cytometry. These human-specific CD45+ cells were then stained with MoAbs (Becton Dickinson) raised against the following antigens and analyzed with flow cytometry: CD33 and CD14 (myeloid markers), CD3 and CD19 (lymphoid markers), and CD34 (progenitor marker). An irrelevant isotype-matched IgG was used as a negative control.

Hematopoietic progenitor assay and cytokine determination. Femoral bone marrow cells (105 cells per plate) were grown for 14 days in methylcellulose under conditions that selectively promote colony formation by human, but not by mouse, progenitor cells.24

We collected plasma from untreated mice and measured the concentrations of human GM-CSF and human TNFα using specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (sensitivity >0.5 pg/mL; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) that do not cross-react with murine cytokines.

Statistics. Values are given as the means and standard error of the mean (SEM). Differences were evaluated with Kruskal-Wallis test including Bonferroni's test when appropriate. Two-tailed tests were used. Statistical significance was assumed for P < .05.

RESULTS

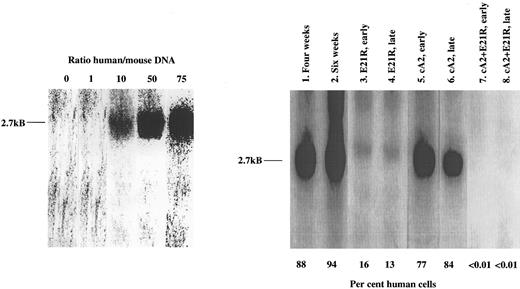

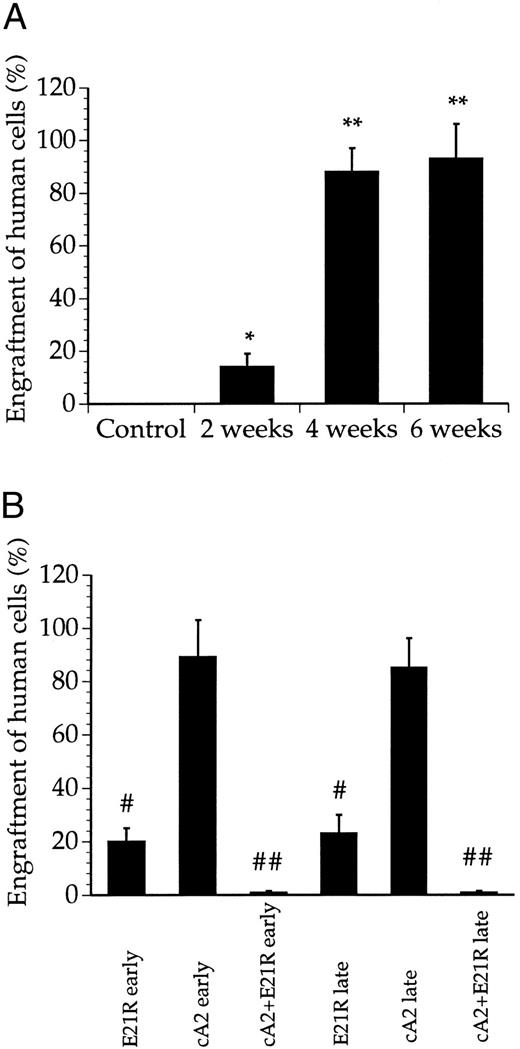

JMML cells engraft and proliferate within SCID/NOD mice. We first examined engraftment of cells collected from JMML patients (Table 1) into untreated SCID/NOD mice. While less than 20% of the bone marrow cells were human-derived 2 weeks posttransplant, we consistently found that 4 weeks after transplantation, the JMML cells repopulated to high levels and constituted a major fraction of the cells in the mouse bone marrow (Figs 1 and 2A). Microscopic examination of bone marrow smears from these mice showed a large number of undifferentiated blasts and a low number of murine bone marrow cells (data not shown). Only a marginal increase in engraftment was obtained after 6 compared with 4 weeks (Figs 1 and 2A).

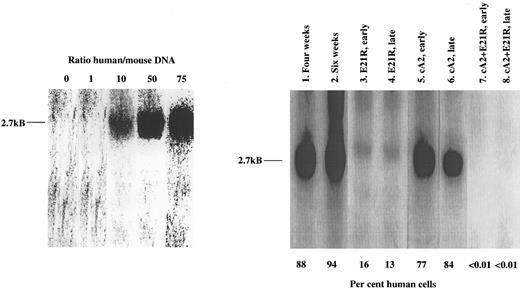

Determination of JMML cell engraftment in SCID/NOD mice using Southern blot analysis of bone marrow DNA. Lanes 1 and 2 refer to untreated mice 4 and 6 weeks posttransplant. The other data are from transplanted mice receiving early or late treatment with either E21R alone (lanes 3 and 4), or MoAb cA2 alone (lanes 5 and 6), or mice receiving 4 weeks treatment with E21R and MoAb cA2 starting at the time of transplantation (early treatment, lane 7), or 4 weeks posttransplant (late treatment, lane 8). Each lane shows blot of bone marrow DNA from one individual mouse and is representative of at least four other mice. The characteristic 2.7-kB band indicating a human specific DNA sequence, is shown to the left, and the percentages of human-derived DNA were estimated from the known human/mice mixtures as indicated.

Determination of JMML cell engraftment in SCID/NOD mice using Southern blot analysis of bone marrow DNA. Lanes 1 and 2 refer to untreated mice 4 and 6 weeks posttransplant. The other data are from transplanted mice receiving early or late treatment with either E21R alone (lanes 3 and 4), or MoAb cA2 alone (lanes 5 and 6), or mice receiving 4 weeks treatment with E21R and MoAb cA2 starting at the time of transplantation (early treatment, lane 7), or 4 weeks posttransplant (late treatment, lane 8). Each lane shows blot of bone marrow DNA from one individual mouse and is representative of at least four other mice. The characteristic 2.7-kB band indicating a human specific DNA sequence, is shown to the left, and the percentages of human-derived DNA were estimated from the known human/mice mixtures as indicated.

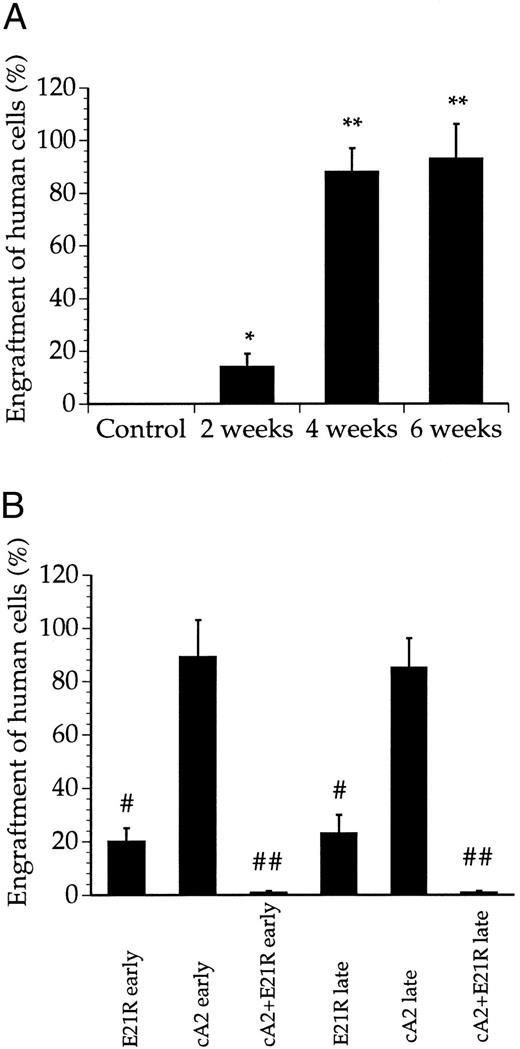

Quantitation of bone marrow engraftment of JMML cells in SCID/NOD mice based on Southern blotting. (A) Bone marrow engraftment of human-derived cells in nontransplanted mice (control) and untreated, transplanted mice 2, 4, and 6 weeks posttransplant. * P < .05, ** P < .01 compared with control mice. (B) Bone marrow engraftment of human-derived cells in mice treated for 4 weeks with E21R alone and/or MoAb cA2 starting from the time of transplant (early treatment) or starting 4 weeks posttransplant (late treatment). # P < .05, ## P < .01 compared with untreated mice 4 weeks posttransplant. Values are the means + SEM from five mice.

Quantitation of bone marrow engraftment of JMML cells in SCID/NOD mice based on Southern blotting. (A) Bone marrow engraftment of human-derived cells in nontransplanted mice (control) and untreated, transplanted mice 2, 4, and 6 weeks posttransplant. * P < .05, ** P < .01 compared with control mice. (B) Bone marrow engraftment of human-derived cells in mice treated for 4 weeks with E21R alone and/or MoAb cA2 starting from the time of transplant (early treatment) or starting 4 weeks posttransplant (late treatment). # P < .05, ## P < .01 compared with untreated mice 4 weeks posttransplant. Values are the means + SEM from five mice.

The degree of engraftment was tested functionally by plating cells from the bone marrow of transplanted mice in semisolid medium under conditions that selectively support growth of human progenitor cells. Figure 3 shows that bone marrow cells from mice 4 weeks posttransplant formed a significant number of colonies albeit to a lesser extent than nonengrafted, primary JMML cells collected directly from the patients. Histologic examination of the colonies showed that most of the cells had a monocytic morphology similar to that found in bone marrow smears from the respective patients (data not shown). As a negative control, we used bone marrow cells from untransplanted mice and these cells did not form any colonies.

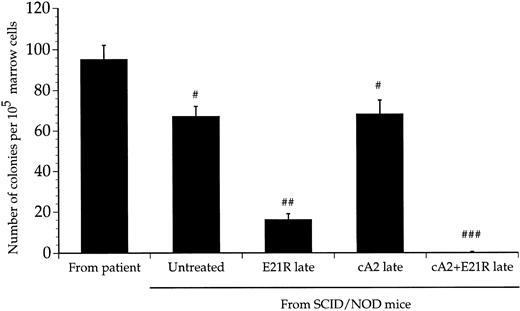

Colony formation by transplanted JMML cells. Colony formation by cells from patient bone marrow (nonengrafted), from untreated, transplanted mice, and mice receiving a 4-week treatment with E21R alone and/or MoAb cA2 starting 4 weeks posttransplant (late treatment). Values are the means ± SEM from five mice. # P < .05, ## P < .01, ### P < .001 compared with colony numbers obtained from nonengrafted patient bone marrow cells.

Colony formation by transplanted JMML cells. Colony formation by cells from patient bone marrow (nonengrafted), from untreated, transplanted mice, and mice receiving a 4-week treatment with E21R alone and/or MoAb cA2 starting 4 weeks posttransplant (late treatment). Values are the means ± SEM from five mice. # P < .05, ## P < .01, ### P < .001 compared with colony numbers obtained from nonengrafted patient bone marrow cells.

The degree of engraftment was also quantitated using an MoAb to the human-specific CD45 surface antigen. These experiments showed that approximately 90% of the bone marrow cells were CD45+ 4 weeks posttransplant. By sorting these cells and subsequently labeling them with MoAbs to various surface antigens, we also determined their phenotype. Table 2 shows that the engrafted human cells predominantly expressed myeloid surface markers, and a substantial fraction was also CD34+ indicating a highly proliferative cell.

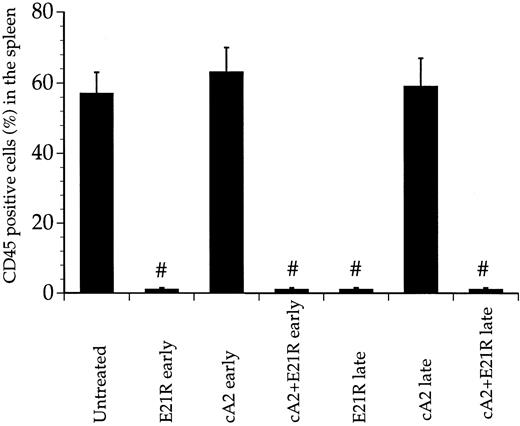

To determine whether the engrafted cells disseminated from the bone marrow, we analyzed splenic cell suspensions and peripheral blood from untreated, transplanted mice. Four weeks after transplantation, more than half the splenic cells were of human origin, as detected by the anti-CD45 MoAb and flow cytometry (Fig 4). Similar to the bone marrow of untreated, transplanted mice, the human-derived cells infiltrating the spleen mostly carried myeloid surface antigens, whereas only a minor portion of the cells expressed the CD34 marker.

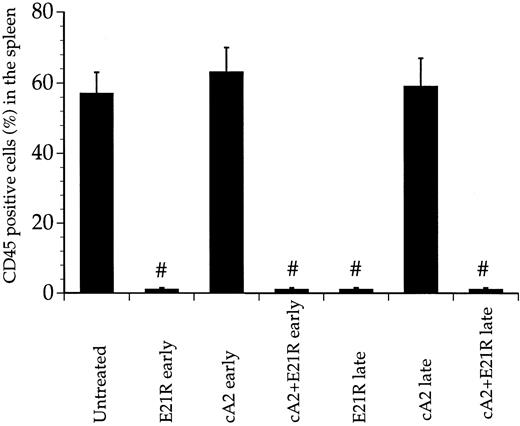

Enumeration of CD45+ cells infiltrating the spleens of transplanted mice. CD45 postive cells were isolated 4 weeks posttransplant from spleens of untreated mice, mice treated for 4 weeks with E21R alone and/or MoAb cA2 starting from the time of transplant (early treatment), or starting 4 weeks posttransplant (late treatment). Values are the means + SEM from five mice; # P < .05 compared with untreated mice.

Enumeration of CD45+ cells infiltrating the spleens of transplanted mice. CD45 postive cells were isolated 4 weeks posttransplant from spleens of untreated mice, mice treated for 4 weeks with E21R alone and/or MoAb cA2 starting from the time of transplant (early treatment), or starting 4 weeks posttransplant (late treatment). Values are the means + SEM from five mice; # P < .05 compared with untreated mice.

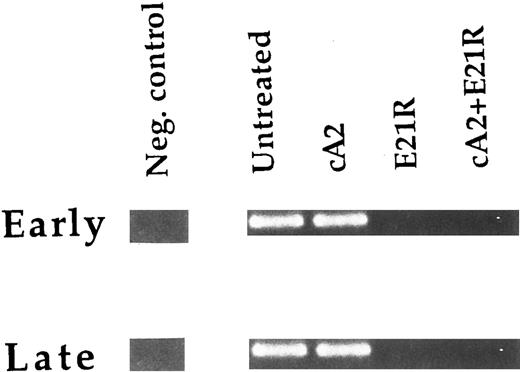

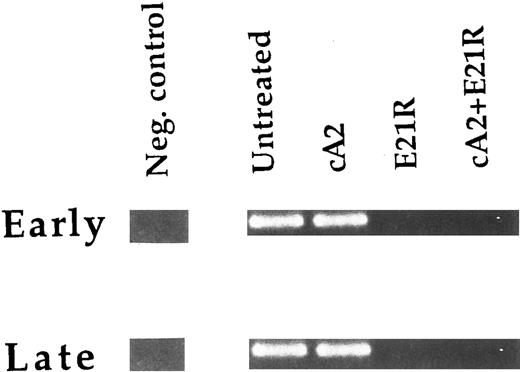

Consistent with the findings in the bone marrow and spleen, we could detect human-derived cells in mouse peripheral blood 4 weeks posttransplant using RT-PCR (Fig 5).

Detection of human-derived cells in peripheral blood of transplanted SCID/NOD mice. RNA was extracted from blood leukocytes and used as starting material for RT-PCR. The bands indicate the PCR product corresponding to the human specific β subunit of the GM-CSF receptor. Results are from one untreated mouse and mice treated for 4 weeks with E21R alone and/or MoAb cA2 starting from the time of transplant (early treatment) or starting 4 weeks posttransplant (late treatment). Mouse bone marrow RNA was used as a negative control. The data are representative of two other experiments.

Detection of human-derived cells in peripheral blood of transplanted SCID/NOD mice. RNA was extracted from blood leukocytes and used as starting material for RT-PCR. The bands indicate the PCR product corresponding to the human specific β subunit of the GM-CSF receptor. Results are from one untreated mouse and mice treated for 4 weeks with E21R alone and/or MoAb cA2 starting from the time of transplant (early treatment) or starting 4 weeks posttransplant (late treatment). Mouse bone marrow RNA was used as a negative control. The data are representative of two other experiments.

Four weeks posttransplant, the plasma concentrations of human GM-CSF and human TNFα ranged from 1.2 to 26 pg/mL (n = 5) and from 3.3 to 7.8 pg/mL (n = 5), respectively, in the untreated, transplanted mice, while neither cytokine was detectable in plasma from nontransplanted mice.

E21R prevents JMML engraftment in SCID/NOD mice. We then studied the engraftment of JMML cells in mice given the GM-CSF analogue E21R, the anti-TNFα MoAb cA2, or both for 4 weeks from the time of transplantation (early treatment). This early treatment of mice with E21R alone markedly decreased the content of human-derived cells in the mouse bone marrow (Figs 1 and 2B). Importantly, we could not demonstrate any human cells within the spleen or peripheral blood in mice receiving E21R (Figs 4 and 5).

Early treatment with MoAb cA2 did not detectably inhibit JMML cell engraftment (Figs 1 and 2B), and the engrafted JMML cells migrated both to the spleen and to peripheral blood to similar extents as that observed in untreated, transplanted mice (Figs 4 and 5).

Higher doses of either E21R or MoAb cA2 produced no additional effect (data not shown). However, Fig 1 and Fig 2B show that a combined blockade of GM-CSF and TNFα with E21R and the MoAb cA2 completely inhibited the engraftment of JMML cells in mice given early treatment. In accordance with these findings, no human-derived cells were detected in the spleen (Fig 4) or in peripheral blood (Fig 5) in transplanted mice receiving this combined treatment.

E21R induces remission in SCID/NOD mice engrafted with JMML cells. We next examined the effect of GM-CSF and TNFα inhibition in mice with an established engraftment of JMML. The mice were transplanted with JMML cells and after four weeks we inserted mini-osmotic pumps releasing either E21R, MoAb cA2, or both. Four weeks treatment with E21R (late treatment) subsequently led to a substantial decrease in JMML cell load in the mouse bone marrow (Figs 1 and 2B), and human-derived cells were not detected in either spleen or peripheral blood (Figs 4 and 5). This late treatment with E21R alone also led to a marked decline in colony formation by the bone marrow cells (Fig 3).

Similar to the findings in mice treated with MoAb cA2 alone from the time of transplantation, late treatment with MoAb cA2 alone failed to affect the marrow engraftment of JMML cells (Figs 1 and 2B). In agreement with this, the spleens and peripheral blood from these mice contained human-derived cells (Figs 4 and 5), and the bone marrow cells from these mice formed large numbers of colonies (Fig 3).

Late treatment with a combination of E21R and MoAb cA2 led to eradication of JMML cells that had homed to the mouse bone marrow 4 weeks posttransplant. Thus, we could not detect any human-derived cells in either the spleen (Fig 4) or peripheral blood (Fig 5) of these mice, and no colonies were formed from bone marrow cells of mice receiving this combined treatment (Fig 3). Concomitant with the reduced JMML cell load, the overall clinical condition of the mice improved.

Preferential effects of E21R and MoAb cA2 on JMML cells versus normal bone marrow cells. We investigated whether normal, human bone marrow cells could survive and proliferate in the marrow microenvironment of irradiated SCID/NOD mice as this could offer the opportunity of testing E21R and MoAb cA2 in animals containing a mixture of normal and malignant cells and thus be more comparable to the clinical situation. To distinguish normal from leukemic cells, we used normal, female bone marrow cells and male JMML cells and applied a fluorescent in situ hybridization method using probes specific for the alpha satellite of the X and Y chromosomes. Normal bone marrow cells homed to the mouse bone marrow both when transplanted alone and when cotransplanted with JMML cells (Table 3). Importantly, engraftment of normal bone marrow cells was not affected by early treatment for 4 weeks with E21R and MoAb cA2 from the time of transplantation, while the cotransplanted JMML cells were not detectable 4 weeks posttransplant in mice receiving this treatment. Significantly, the normal bone marrow cells engrafted in untreated mice to a similar degree irrespective of whether they were cotransplanted with JMML cells (Table 3). The two populations of human-derived cells (normal and JMML) apparently survive and proliferate independently within the bone marrow of these mice, and JMML cells are selectively susceptible to the combined effect of E21R and MoAb cA2.

DISCUSSION

We show here for the first time that antagonizing human GM-CSF in vivo prevents the engraftment and induces remission of human JMML in a mouse model. JMML is a rare and aggressive childhood malignancy with an almost invariably fatal outcome. Only short-lasting remissions have been obtained using chemotherapy.1,3,4 Complete cure has only been observed in patients receiving bone marrow transplantation, but the relapse frequency usually exceeds 50%, and most children suffer from severe side effects related to the transplantation regimens.5 6

The basic molecular defect underlying this disorder has not been identified. Pathogenic point mutations of the GM-CSF receptor complex are unlikely to explain the hypersensitivity of JMML cells to GM-CSF.25 Emerging evidence points to a crucial role of the GM-CSF/ras signaling pathway. There is an increased frequency of mutations in the ras genes in patients with myelodysplastic disorders including JMML,26,27 leading to a constitutive ras activation10,11 that might be further increased on stimulation with GM-CSF.28 This might explain the hypersensitivity of JMML cells to GM-CSF7-9,13 and provides a rationale for the potential usefulness of inhibiting GM-CSF in JMML patients.

Current knowledge of the GM-CSF–promoting effects on growth and survival of JMML cells mostly rely on in vitro studies. It was thus pertinent to use an animal model for this human leukemia to study the effects of GM-CSF inhibition of JMML cells in vivo. The irradiated SCID/NOD mice are defective in their cellular and humoral immunity, rendering them unable to reject xenografts such as human blood progenitor cells.19,29 Engraftment of these mice with human leukemias has thus become an important tool for examining the growth and dissemination patterns of transplanted leukemic cells,20,24,30,31 as well as the effects of antileukemic drugs.32

We found high levels of engraftment of JMML cells 4 to 6 weeks posttransplant as determined with three independent methods (Southern blotting, flow cytometry, and in situ hybridization). Thus, the bone marrow in SCID/NOD mice provides a suitable environment for growth of primary JMML cells. Although no pathognomonic feature of JMML cells have been identified, the morphologic appearance plus the marked spontaneous colony formation and the dissemination pattern together suggest that cells collected from the mouse bone marrow 4 to 6 weeks posttransplant most likely originated from the injected JMML cells.

Prompted by our recent finding that the selective GM-CSF analogue E21R could inhibit JMML colony formation by inducing apoptosis,13 we examined the effect of E21R on growth and dissemination of JMML cells transplanted into SCID/NOD mice. Systemic treatment with E21R significantly decreased proliferation of JMML cells in the mouse bone marrow and either abolished spill-over of leukemic cells into the circulation or exerted a specific inhibition of circulating leukemic cells. At the end of the treatment period, the number of murine bone marrow cells increased and a general improvement of the clinical condition of the mice was noted as well.

Interestingly, E21R exerted its antileukemic effects irrespective of whether it was administered at the time of transplantation or after overt leukemia had developed. This finding suggests that E21R inhibits leukemic cells of varying maturity. This is an important observation, as the more mature cells had disseminated and infiltrated, eg, the spleen, while the immature CD34 cells remained in the bone marrow (Table 2). It would be important to determine whether the leukemic initiating cell, as well as the committed leukemic progenitors, express receptors for GM-CSF and can thus be susceptible to the inhibitory effect of E21R.

The molecular mechanism underlying the antileukemic effect of E21R in JMML engrafted mice may be related to its antagonistic15 or to its apoptotic13 properties or to a combination of both. Typically the plasma concentration of E21R was one million times that of human GM-CSF, thus well above that required to antagonize GM-CSF–mediated functions.15 Furthermore, we have previously demonstrated that E21R can induce apoptosis in various myeloid leukemic cells by a direct action.13,33 In separate experiments, we examined mouse tissue for evidence of apoptosis, however, it was not possible to exactly determine the fraction of apoptotic leukemic cells within the mouse bone marrow due to the presence of necrotic cells, probably caused by the gradual cessation of bone marrow perfusion during leukemic development.34

We could not demonstrate any effect on JMML cell engraftment or dissemination in the mice during treatment with the neutralizing anti-TNFα MoAb cA2 alone. On the other hand, a synergistic inhibitory effect was observed in mice receiving a combined treatment with E21R and MoAb cA2, either starting at the time of transplantation or at a time when the mice had become sick. It is possible that TNFα has some effect on JMML cell growth by increasing GM-CSF production,7,13 16 thus explaining the maximal effect seen when inhibiting both cytokines in the transplanted mice.

An unexpected, yet important observation was that while E21R and MoAb cA2 added together markedly reduced the leukemic cell load, the normal bone marrow cells cotransplanted into the same mice were apparently unaffected by this treatment. Although the normal bone marrow cells did not engraft to similar high levels as the JMML cells, they clearly homed to the mouse bone marrow and to similar extents irrespective of whether they were transplanted alone or together with JMML cells. How the normal bone marrow cells escape the effect of E21R and MoAb cA2 is not clear. Bone marrow cells from a healthy male and female both engrafted well when they were simultaneously transplanted into mice (data not shown), and this most likely rules out any incompatibility of the major histocompatibility complexes as a cause of the selective eradication of JMML cells in treated mice. The requirement of normal bone marrow cells for engraftment in the murine bone marrow environment is probably different from that of the JMML cells. It is likely that JMML cells are exquisitely sensitive to GM-CSF, which they themselves produce, while normal bone marrow cells may be influenced by a variety of soluble and stroma-bound factors present in the bone marrow microenvironment, and thus bypass or overcome the effect of E21R.

The present study shows for the first time an antileukemic effect in vivo of a specific GM-CSF inhibitor. The profound decrease in JMML cell load and tissue infiltration by E21R and the preferential susceptibility of leukemic over normal bone marrow cells to the inhibitory effect of E21R and MoAb cA2 suggest that further studies to establish the safety and efficacy of these two specific cytokine inhibitors are warranted.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Dr J.E. Dick for supplying the DNA probe used for Southern blotting, for advice during this study, and for criticizing the manuscript. We would also like to thank Dr R. D'Andrea for supplying the PCR probes and A. Nitschke for excellent secretarial assistance. The MoAb cA2 was a gift from Centocor.

Supported in part by the Anti-Cancer Foundation of the Universities of South Australia. P.O.I. holds a fellowship with the Norwegian Cancer Society.

Address reprint requests to Angel F. Lopez, MD, PhD, Division of Human Immunology, IMVS, PO Box 14 Rundle Mall, Adelaide, 5000 S.A., Australia.