Abstract

Leptin, the product of obese gene, was originally identified as a factor regulating body-weight homeostasis and energy balance. The present study has shown that leptin acts on murine hematopoiesis in vitro. In the culture of bone marrow cells (BMC) of normal mice, leptin induced only granulocyte-macrophage (GM) colony formation in a dose-dependent manner, and no other types of colonies were detected even in the presence of erythropoietin (Epo). Leptin also induced GM colony formation from BMC of db/db mutant mice whose leptin receptors were incomplete, but the responsiveness was significantly reduced. The effect of leptin on GM colony formation from BMC of normal mice was also observed in serum-free culture, and comparable with that of GM-colony–stimulating factor (CSF ). Although leptin alone supported few colonies from BMC of 5-fluorouracil (5-FU)–treated mice in serum-free culture, remarkable synergism between leptin and stem cell factor (SCF ) was obtained in the colony formation. The addition of leptin to SCF enhanced the SCF-dependent GM colony formation and induced the generation of a number of multilineage colonies in the presence of Epo. When lineage (Lin)−Sca-1+ cells sorted from BMC of 5-FU–treated mice were incubated in serum-free culture, leptin synergized with SCF in the formation of blast cell colonies, which efficiently produced secondary colonies including a large proportion of multilineage colonies in the replating experiment. In serum-free cultures of clone-sorted Lin−c-Kit+Sca-1+ and Lin−c-Kit+Sca-1− cells, although synergism of leptin and SCF was observed in the colony formation from both cells, leptin alone induced the colony formation from Lin−c-Kit+Sca-1−, but not Lin−c-Kit+Sca-1+ cells. These results have shown that leptin stimulates the proliferation of murine myelocytic progenitor cells and synergizes with SCF in the proliferation of primitive hematopoietic progenitors in vitro.

THE DEVELOPMENT of hematopoietic cells is regulated by various hematopoietic cytokines, each directed at different developmental stages.1 Hematopoietic cytokines exert their biologic functions through specific receptors on the surface of target cells.2 The majority of cytokine receptors fall into a hematopoietic cytokine receptor family, which is characterized by a 200-amino acid conserved domain that has four positionally conserved cysteine residues and a WSXWS motif.3 This large family includes receptors for erythropoietin (Epo), thrombopoietin (Tpo), granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF ), and interleukin-12 (IL-12), α-chains of receptors for IL-6, leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF ), and ciliary neurotrophic factor, and their common β-chain gp130, α-chains of IL-3, IL-5, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF ), and their common β-chain, β- and γ-chains of IL-2 receptor (IL-2R), and receptors for IL-4, IL-7, and IL-9, which form their specific receptor complexes commonly using γ-chain of IL-2R.2

Leptin, the product of obese (ob ) gene, is a 16-kD protein primarily produced by adipocytes, regulating nutrient intake and metabolism.4 Mice that are homozygous for mutations in ob gene exhibit profound obesity resulting from defects in energy expenditure, food intake, and nutrient partitioning.5 Mice homozygous for well-characterized diabetes (db ) gene mutation exhibit an obesity phenotype nearly identical to the phenotype of ob/ob mice.6 Parabiosis study has indicated that ob/ob mice are defective in the production of a humoral factor encoded by ob gene, whereas db/db mice have the impaired responsiveness to the factor.7 Recently, the leptin receptor, obese receptor (OBR), was cloned and the OBR gene was shown to be mapped to the same 5-centimorgan interval on mouse chromosome 4 to which db had been localized.8 The OBR is a member of hematopoietic cytokine receptor family, and shows sequence similarity to gp130, G-CSFR, and LIFR. Splice variants of OBR mRNA encode proteins, which differ in the length of their cytoplasmic domains.9-12 A long isoform of OBR is preferentially expressed in the hypothalamus of wild-type mice and can activate signal transducers and activators of transcription (STAT)-3, -5, and -6.11 A point mutation within the OBR gene of db/db mice generates a shorter isoform of OBR by abnormal splicing, and the expression of the long isoform of OBR is dramatically suppressed in db/db mice. The isoform with a shorter cytoplasmic domain is unable to activate the STAT pathway, causing the db/db phenotype.

More recently, the long form of OBR has been shown to be expressed in enriched hematopoietic stem cells and a variety of hematopoietic cell lines.12 We next examined the effect of leptin on murine hematopoiesis using methylcellulose clonal culture. The results have indicated that leptin stimulates the proliferation of murine myelocytic and primitive hematopoietic progenitor cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell preparation. Female C57BL/6J and C57BLKS/J db/db mice and (C57BL/6 × DBA/2)F1 (BDF1) mice, 8 to 10 weeks old, were obtained from Clea Japan, Inc (Tokyo, Japan) and Japan SLC, Inc (Shizuoka, Japan), respectively. Bone marrow cells (BMC) of the mice were prepared in α-medium (Flow Laboratories, Rockville, MD). Some mice were injected with 150 mg/kg 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) (Kyowa Hakko Kogyo Co, Tokyo, Japan) through the tail vains 2 days before marrow harvest.

Cytokines. Recombinant mouse (m) leptin was purchased from Pepro Tech EC Ltd (London, UK). Recombinant mIL-3, human (h) GM-CSF, hEpo, and hG-CSF were kindly provided by Kirin Brewery (Tokyo, Japan). Recombinant rat stem cell factor (SCF ) was supplied by Amgen (Thousand Oaks, CA). Recombinant hIL-6 was a gift from Tosoh Corporation (Kanagawa, Japan). Recombinant mIL-4, hIL-11, mIL-12, and mLIF were purchased from Genzyme (Cambridge, MA).

C l o n a l a s s a y o f m u r i n e h e m a t o p o i e t i c p r o g e n i t o r c e l l s. Methylcellulose clonal culture was done using a modification of the technique described previously.13 A total of 1 mL of culture mixture containing 2.5 to 5 × 104 BMC or 250 Lin−Sca-1+ cells, α-medium, 1.2% methylcellulose (Shinetsu Chemical, Tokyo, Japan), 30% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Hyclone Laboratories, Logan, UT), 1% deionized fraction V bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma, St Louis, MO), 1 × 10−4 mol/L mercaptoethanol (Eastman Organic Chemicals, Rochester, NY), and cytokines was plated in 35-mm suspension culture dishes (#171099; Nunc, Naperville, IL). Serum-free culture contained 300 μg/mL of fully iron-saturated human transferrin (Sigma), 160 μg/mL of soybean lecitin (Sigma), 96 μg/mL of cholesterol (Sigma), and 1% deionized crystallized BSA (Sigma) instead of 30% FBS and 1% fraction V BSA. Dishes were incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere flushed with 5% CO2 in air. Unless otherwise specified, concentrations of cytokines used in the present study were: 10 ng/mL for mIL-3, mGM-CSF, hG-CSF, mIL-4, mIL-12, and mLIF; 100 ng/mL for hIL-6, hIL-11, and mSCF; and 2 U/mL for hEpo, which are in the range of optimal concentrations for colony formation as reported previously.14,15 Colony types were determined at days 7 to 14 of culture by in situ observation using an inverted microscope and according to the criteria described by Nakahata et al.16 Except for magakaryocyte colonies, cell aggregates consisting of more than 50 cells were scored as colonies. Megakaryocyte colonies were scored as such when they had four or more megakaryocytes.17 To assess the accuracy of in situ identification of the colonies, individual colonies were lifted with an Eppendorf micropipette under direct microscopic visualization, spread on glass slides using a cytocentrifuge (Cytospin 2; Shandon Southern Instruments, Sewickly, PA), and then stained with May-Grünwald-Giemsa. The abbreviations used for the colony types are as follows: E, erythroid bursts; GM, granulocyte-macrophage; Mk, megakaryocyte; EM, erythrocyte-megakaryocyte; GEM, granulocyte-erythrocyte–megakaryocyte; GMM, granulocyte-macrophage–megakaryocyte; GEMM, granulocyte-erythrocyte–macrophage-megakaryocyte; and blast, blast cell colonies.

Cell sorting and single cell culture. Sorting of lineage (Lin)Sca-1+ cells was performed with a modification of the technique described previously.18 Briefly, day 2 post-5–FU marrow cells were first enriched by density gradient separation and negative selection with immunomagnetic beads (Dynabeads M-450, coated with sheep antirat IgG; Dynal A.S., Oslo, Norway) using a cocktail of monoclonal antibodies specific for CD45R/B220 (RA3-6B2), CD4 (RM4-5), CD8 (53-6.72), Gr-1 (RB6-8C5), TR119 (TER119) (each purchased from Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) and Mac-1 (M1/70.15.1) (Serotec, Oxford, UK). The lineage markers-negative cells were then stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated antimouse Ly6A/E (E13-161.7, Sca-1) (Pharmingen), and the positive population was sorted based on cells stained with FITC-conjugated rat IgG2a (Cedarlane Laboratories, Ltd, Ontario, Canada) as isotype-matched control with a FACSVantage (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA). Clone-sorting of Lin−c-Kit+ Sca-1+ and Lin−c-Kit+ Sca-1− cells was performed with a modification of the method described previously.19 BMC enriched by density gradient separation were incubated with phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated Sca-1 (Pharmingen), allophycocyanin (APC)-conjugated anti–c-Kit antibody (ACK-2, kindly provided by Dr Shin-Ichi Nishikawa, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan) and biotinylated lineage markers. After 20 minutes of incubation on ice, the cells were washed twice and incubated with texas red (TR)-conjugated streptavidin (Life Technologies, Inc, Gaithersburg, MD) for 20 minutes on ice. The negative controls were cells stained with PE-conjugated rat IgG2a (Cedarlane), APC-conjugated rat IgG2b (Pharmingen) or only TR-conjugated streptavidin. Based on these controls, Lin−c-Kit+ Sca-1+ and Lin−c-Kit+ Sca-1− cells were sorted singly into 96-well flat-bottomed plates (Nunc) with a FACSVantage equipped with an automated cell deposition unit (ACDU, Becton Dickinson). The clone-sorted cells were cultured in each well containing serum-free culture medium supplemented with 103 ng/mL of leptin and/or 100 ng/mL of SCF at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere flushed with 5% CO2 in air. After 7 days of incubation, colony formation in each well was examined by in situ observation using an inverted microscope and cytospin preparation of the cultured cells.

Replating experiment. The replating experiment was performed with blast cell colonies supported in serum-free culture of Lin−Sca-1+ cells sorted from BMC of 5-FU–treated mice as described previously with a minor modification.20 Blast cell colonies consisting of 50 to 150 cells were individually lifted from the methylcellulose at days 8 to 10 of culture, washed twice, and resuspended in 200 μL of α-medium. These samples were divided into two aliquots: 100 μL was replated in secondary cultures supplemented with SCF, IL-3, IL-6, G-CSF, Epo, and Tpo for hematopoietic progenitor assay, and the remaining 100 μL was used for cytospin preparations stained with May-Grünwald-Giemsa to confirm their blastic characters.

Statistical analysis. For the statistical comparison in scoring the numbers of colonies, Student's t-test was applied. The significant level was set at .05.

RESULTS

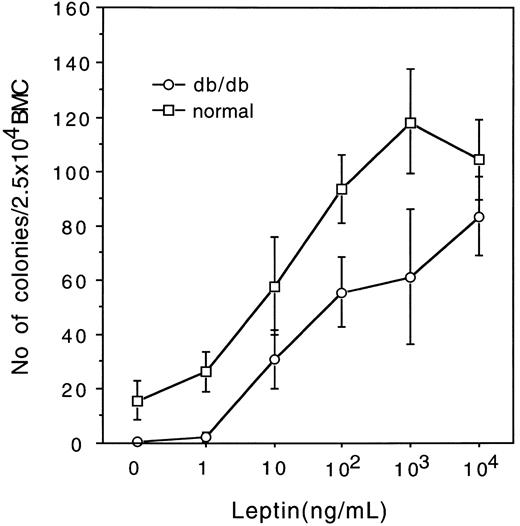

Effect of leptin on murine myelocytic progenitors. We first tested the effect of varying concentrations of leptin on the colony formation from 2.5 × 104 BMC of normal mice (C57BL/6J) and db/db mutant mice (C57BLKS/J) in methylcellulose clonal culture. As shown in Fig 1, leptin dose-dependently supported the formation of GM colonies from BMC of normal mice. The number of GM colonies reached a plateau at 103 ng/mL of leptin, and no other types of colonies were detected at concentrations up to 104 ng/mL. Leptin also induced GM colony formation from BMC of db/db mice, but the responsiveness was significantly reduced. Although 104 ng/mL of leptin induced almost the same number of GM colonies in normal and db/db mice, in db/db mice more than 10 times of leptin was required for the comparable effect with that in normal mice at concentrations of less than 103 ng/mL.

Effects of varying concentrations of leptin on GM colony formation from 2.5 × 104 BMC of normal (□) and db/db mutant mice (○).

Effects of varying concentrations of leptin on GM colony formation from 2.5 × 104 BMC of normal (□) and db/db mutant mice (○).

When BMC of BDF1 mice were cultured with varying concentrations of leptin, GM colonies were produced in a dose-dependent manner with a plateau level at 103 ng/mL of leptin, similar to that in C57BL/6J mice (data not shown). We then performed serum-free culture of 2.5 × 104 BMC of BDF1 mice with 103 ng/mL of leptin and/or Epo to examine the effects of leptin in more detail, comparing with those of IL-3 or IL-6 (Table 1). While the growth of various types of colonies, including erythroid bursts, GM, megakaryocyte, and multilineage colonies were induced by a combination of IL-3 and Epo, leptin supported only GM colony formation even in the presence of Epo. The number of GM colonies induced by leptin was approximately one third of that by IL-3 and Epo. IL-6 induced no colony formation. This result indicates that leptin alone specifically stimulates the development of myelocytic progenitors.

Comparison of leptin with other cytokines in the effects on murine myelocytic progenitors. We next compared the activity of leptin on murine myelopoiesis with those of G-CSF, IL-3, GM-CSF, and SCF using serum-free culture of BMC of BDF1 mice with Epo (Table 2). G-CSF induced no colony formation in the serum-free culture, and the addition of G-CSF to leptin had no effect on the GM colony formation by leptin. IL-3 induced twice the number of GM colonies by leptin, and the addition of leptin had no effect on the GM colony formation by IL-3. GM-CSF and SCF induced almost the same number of GM colonies to leptin. However, the addition of leptin to GM-CSF did not affect the GM colony formation, whereas that to SCF induced a twofold increase in the number of GM colonies. This observation indicates that the target cells of leptin are overlapped with those of GM-CSF. The morphologic analysis on the cytospin preparations of individual colonies in the serum-free culture showed no difference in the proportion of granulocytic cells and macrophages and their maturity between the colonies supported by leptin and GM-CSF, indicating that leptin supports not only the proliferation of myelocytic progenitors, but also their differentiation into mature myelocytic cells. In this experiment, it was of interest that the combination of leptin and SCF induced the generation of a significant number of multilineage colonies, suggesting a possibility that leptin synergizes with SCF to stimulate murine primitive hematopoietic progenitor cells.

Effect of leptin on primitive hematopoietic progenitor cells. To examine the effect of leptin on primitive hematopoietic progenitor cells, we performed serum-free culture of 5 × 104 BMC of 5-FU–treated BDF1 mice (Table 3). When cultured with 103 ng/mL of leptin, BMC generated only a small number of GM colonies whether in the presence or absence of Epo. A combination of SCF and Epo supported more GM colonies and a few erythroid bursts, GEM, and blast cell colonies. The addition of leptin to the combination induced an increase of GM colonies, but the most significant effect was achieved with the generation of multilineage colonies. While SCF supported only 2 ± 1 GEM colonies, the combination of leptin and SCF induced 20 ± 9 multilineage colonies including EM, GMM, GEM, and GEMM colonies in the presence of Epo (P < .05). This result indicates that leptin synergizes with SCF to stimulate murine primitive hematopoietic progenitors. We have previously reported that IL-6 also synergizes with SCF in the proliferation of murine primitive progenitors.14 The synergistic effect of leptin with SCF was comparable to that of IL-6, although only little synergism was observed between leptin and IL-6.

To confirm the synergism of leptin with SCF in the proliferation of murine hematopoietic progenitors, we further performed serum-free culture of Lin−Sca-1+ cells sorted from BMC of 5-FU–treated mice, which were shown to be an enriched murine primitive hematopoietic cell population.21 When 250 sorted Lin−Sca-1+ cells were cultured, leptin or SCF alone supported no colony formation. However, a combination of leptin and SCF induced the formation of 12 ± 1 blast cell colonies. In the replating experiment of eight blast cell colonies consisting of 50 to 150 cells whose blastic characters were confirmed by the morphologic examination of the cytospin preparations, all of the colonies yielded a number of secondary colonies including a large proportion of multilineage colonies (Table 4). These results clearly indicate that leptin synergizes with SCF to stimulate the proliferation of murine primitive hematopoietic progenitor cells.

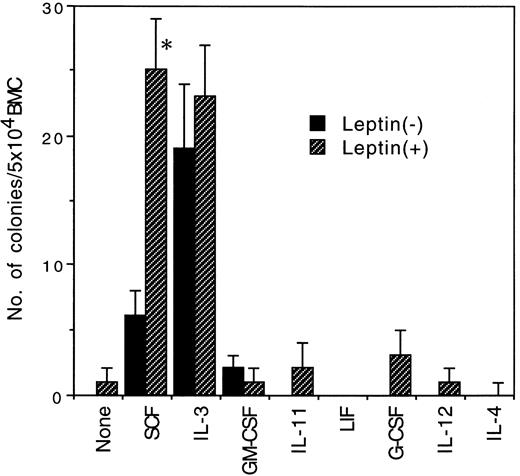

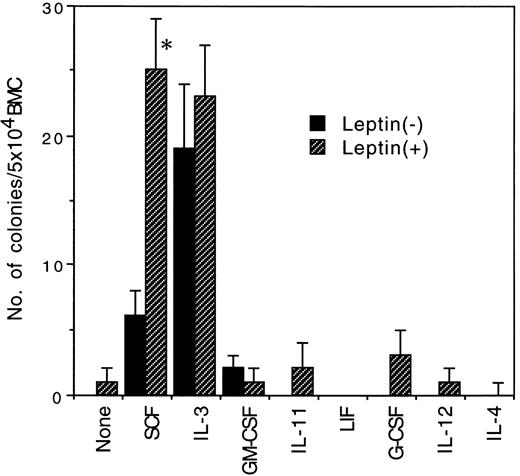

Effect of leptin in combinations with various early-acting cytokines on murine primitive hematopoietic progenitors. To examine whether leptin synergizes with other cytokines to stimulate murine primitive hematopoietic progenitors, we performed serum-free culture of BMC of 5-FU–treated BDF1 mice with 103 ng/mL of leptin in combinations with various cytokines, which had been reported to act on murine primitive hematopoietic progenitors (Fig 2). Leptin showed no synergistic activity with all of the cytokines examined such as IL-3, GM-CSF, IL-11, LIF, G-CSF, IL-12, and IL-4. Thus, leptin specifically synergized with SCF in the stimulation of murine primitive hematopoietic progenitor cells.

Effects of leptin in combinations with various early-acting cytokines on the colony formation from 5 × 104 BMC of 5-FU–treated mice. A total of 100 ng/mL of SCF and IL-11 and 10 ng/mL of IL-3, IL-4, IL-12, GM-CSF, LIF, and G-CSF were added in the presence (▨) or absence (▪) of 103 ng/mL of leptin. Significantly different from their counterparts without leptin (*P < .05).

Effects of leptin in combinations with various early-acting cytokines on the colony formation from 5 × 104 BMC of 5-FU–treated mice. A total of 100 ng/mL of SCF and IL-11 and 10 ng/mL of IL-3, IL-4, IL-12, GM-CSF, LIF, and G-CSF were added in the presence (▨) or absence (▪) of 103 ng/mL of leptin. Significantly different from their counterparts without leptin (*P < .05).

Colony formation from clone-sorted Lin−c-Kit+Sca-1+ and Lin−c-Kit+Sca-1− cells. Finally, to eliminate influences of accessory cells completely, we performed serum-free culture of Lin−c-Kit+Sca-1+ and Lin−c-Kit+Sca-1− cells clone-sorted from BMC of BDF1 mice (Table 5). When 183 Lin−c-Kit+Sca-1− cells were cultured, leptin alone induced five colonies, all of which were GM colonies. SCF alone induced two colonies from 180 Lin−c-Kit+Sca-1− cells, and the addition of leptin to SCF induced 16 colonies from 182 Lin−c-Kit+Sca-1− cells. By contrast, leptin or SCF alone could not support the proliferation of single Lin−c-Kit+Sca-1+ cells, but the combination of leptin and SCF induced four colonies from 92 Lin−c-Kit+Sca-1+ cells. Because Lin−c-Kit+Sca-1+ hematopoietic progenitors were shown to be more primitive than Lin−c-Kit+Sca-1− cells,22 this result indicates that leptin alone acts on relatively mature progenitors and synergizes with SCF to stimulate the proliferation of primitive hematopoietic progenitors in accordance with the results described above. It also shows that the action of leptin on these progenitors is not mediated by accessory cells.

DISCUSSION

Although leptin was originally identified as a factor regulating body-weight homeostasis and energy balance, the present study has clearly shown that this cytokine has the capacity to stimulate murine hematopoiesis in vitro. Because the effect of leptin on murine hematopoietic progenitors was confirmed by serum-free culture of Lin−Sca-1+ cells sorted from BMC of 5-FU–treated mice and clone-sorted Lin−c-Kit+Sca-1+ and Lin−c-Kit+Sca-1− cells in the present study, it is not mediated by accessory cells. However, there remains a possibility that leptin might induce the production of cytokines by hematopoietic progenitors that stimulate their own proliferation.

The clonal culture of BMC of normal mice has shown that leptin stimulates murine myelopoiesis. Leptin alone induced GM colony formation in the culture, and no other types of colonies were detected even in the presence of Epo. This effect of leptin on GM colony formation was significantly reduced in db/db mutant mice, in which the expression of the long form of OBR capable of activating the signal was suppressed, suggesting that leptin activates OBR signaling to stimulate the proliferation of myelocytic progenitors. Because leptin alone supported only a small number of GM colonies from BMC of 5-FU–treated mice, leptin as a single factor may predominantly act on relatively mature myelocytic progenitors, which were overlapped with the target cells of GM-CSF. The observation that leptin alone induced the colony formation from clone-sorted Lin−c-Kit+Sca-1−, but not Lin−c-Kit+Sca-1+ cells, also indicated the predominant effect of leptin as a single factor on mature progenitors, as Lin−c-Kit+Sca-1− progenitors were shown to be more mature. However, the addition of leptin to SCF induced the increase of GM colonies in the culture of BMC of 5-FU–treated mice, suggesting that the proliferation of more immature myelocytic progenitors requires the synergistic action of leptin and SCF. In addition, morphologic analysis showed that leptin also supported the differentiation of myelocytic progenitors into mature melocytic cells.

The culture of BMC of 5-FU–treated mice has indicated that leptin also acts on murine primitive hematopoietic progenitors, whose multipotentiality was confirmed in the replating experiments. Leptin stimulated the proliferation of primitive hematopoietic progenitors synergistically with SCF, although leptin alone did not. Previous studies have shown that IL-6, IL-11, IL-12, and G-CSF also synergize with SCF to stimulate the proliferation of murine primitive progenitor cells.14,23 Recently, it has been shown that receptors for IL-6 and IL-11 share a common signal transducing component, gp130.24 Furthermore, receptors for G-CSF and IL-12 were shown to reveal a high homology with gp13025,26 and categorized into the gp130 receptor family.27 We have shown synergism between gp130 signal mediated by a complex of IL-6 and soluble IL-6 receptor and c-kit signal by SCF in the proliferation of human primitive hematopoietic progenitor cells.19,28 Thus, synergistic action of signals through the gp130 receptor family and c-kit may play a role in the proliferation of murine and human primitive hematopoietic progenitors, although it is not determined whether they share a common signaling pathway. In this study, leptin showed the synergistic action with SCF, similar to that of IL-6, in the proliferation of murine primitive hematopoietic progenitors, although the effects on myelocytic progenitors were different between leptin and IL-6. Because OBR has been shown to belong to the gp130 receptor family,8 the present result further supports the model that signals through the gp130 receptor family and c-kit synergistically act on primitive hematopoietic progenitor cells.

Although we have documented hematopoietic effects of leptin in vitro, its physiologic role in hematopoiesis is unknown at this time. Nevertheless, this cytokine may be important to manipulate primitive hematopoietic progenitor cells. There has been great interest in ex vivo expansion of hematopoietic stem cells for clinical application including gene therapy. Leptin may prove to be useful in future manipulation of hematopoietic stem cells.

Address reprints requests to Tatsutoshi Nakahata, MD, Department of Clinical Oncology, The Institute of Medical Science, The University of Tokyo, 4-6-1 Shirokanedai, Minato-ku, Tokyo 108, Japan.