Abstract

The influence of interferon- (IFN) pretreatment on the outcome after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation (BMT) in chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) is controversial. One goal of the German randomized CML Studies I and II, which compare IFN ± chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone, was the analysis of whether treatment with IFN as compared to chemotherapy had an influence on the outcome after BMT. One hundred ninety-seven (23%) of 856 Ph/bcr-abl–positive CML patients were transplanted. One hundred fifty-two patients transplanted in first chronic phase were analyzed: 86 had received IFN, 46 hydroxyurea, and 20 busulfan. Forty-eight patients (32%) had received transplants from unrelated donors. Median observation time after BMT was 4.7 (0.7 to 13.5) years. IFN and chemotherapy cohorts were compared with regard to transplantation risks, duration of treatments, interval from discontinuation of pretransplant treatment to BMT, conditioning therapy, graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis and risk profiles at diagnosis and transplantation, and IFN cohorts also with regard to performance and resistance to IFN. Outcome of patients receiving related or unrelated transplants pretreated with IFN, hydroxyurea, or busulfan was not significantly different. Five-year survival after transplantation was 58% for all patients (57% for IFN, 60% for hydroxyurea and busulfan patients). The outcome within the IFN group was not different by duration of prior IFN therapy more or less than 5 months, 1 year, or 2 years. In contrast, a different impact was observed in IFN-pretreated patients depending on the time of discontinuation of IFN before transplantation. Five-year survival was 46% for the 50 patients who received IFN within the last 90 days before BMT and 71% for the 36 patients who did not (P = .0057). Total IFN dosage had no impact on survival after BMT. We conclude that outcome after BMT is not compromised by pretreatment with IFN if it is discontinued at least 3 months before transplantation. Clear candidates for early transplantation should not be pretreated with IFN.

INTERFERON-α (IFN) and bone marrow transplantation (BMT) are current complementary and competing treatments of choice for patients with Ph/bcr-abl–positive chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) in chronic phase.1 The early BMT-associated mortality would favor a trial with IFN first in most patients and transplantation only, if the response to IFN is unsatisfactory. Delay of transplantation, however, might lower probability of cure because the success rate of transplantation decreases as time elapsed after the diagnosis of CML increases.2 Still, a limited trial with IFN of 6 to 12 months’ duration could be discussed. Three reports challenge this concept and suggest that IFN per se, in addition to the time aspect, may be harmful for a subsequent transplantation because of increased transplantation-related early death rates due to graft rejection3 or graft-versus-host disease.4Preliminary observations of a third group5 suggest an increased transplant-related mortality for patients receiving IFN within the last 3 months preceding BMT. Other publications involving more than 300 patients could not confirm adverse effects of pretransplant IFN.6-10 These conflicting reports require critical consideration. The reports with adverse outcome were not derived from controlled studies or predefined cohorts of patients and, therefore, are subject to referral bias. The referral aspect is critical because IFN-treated patients who respond well to IFN are less likely referred to transplantation than patients who respond to IFN poorly or not at all. In addition, assignment of primary treatment was nonrandom, introducing another possible source of bias. Also, the reasons for increased transplant-related mortality after IFN pretreatment differed between reports.

Since the issue of a possible impact of IFN pretreatment on the outcome of BMT was considered in the protocols of the German CML Study Group from the very beginning and was a goal of CML Studies I and II, we performed the present analysis to resolve this issue. In particular, we wanted to test the hypothesis generated by Holler et al5 of an increased transplant-related mortality for patients receiving IFN within the last 90 days preceeding BMT. The results suggest that IFN can be given safely to BMT candidates, if it is terminated 3 months before transplantation, but should not be given in clear candidates for early transplantation (BMT mortality <20%).

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study design.

This study is based on 2 consecutive randomized trials of the German CML-Study Group comprising 856 Ph– and/or bcr-abl–positive patients with CML (CML study I: IFN v hydroxyurea v busulfan, recruitment July 1983 [IFN: June 1986]-January 1991, 701 patients recruited, 605 randomized, 516 Ph/bcr-abl–positive,11 and CML study II: combination of IFN and hydroxyurea v hydroxyurea monotherapy, recruitment February 1991-December 1994, 426 patients recruited, 366 randomized, 340 Ph/bcr-abl–positive12), representing 10% of the estimated number of CML cases in Western Germany over an 11.5-year period. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for randomization and treatment were identical in both studies. One goal of the studies was the analysis of whether treatment with IFN as compared to chemotherapy had an influence on outcome or prognosis after subsequent BMT. BMT was recommended to all patients who could tolerate the procedure and had a compatible donor. The protocol provided that all newly diagnosed CML patients in chronic phase of the participating centers were randomized, including those qualifying for early BMT, and that BMT patients were counted as lost to follow up at the time of BMT and evaluated separately. The studies were discussed with the German working party for BMT (Deutsche Arbeitsgemeinschaft für KMT) up-front for maximal cooperation by all transplantation centers. There were no treatment-related decisions for BMT.

Patients.

All patients with CML who received a BMT within their treatment course on the German randomized multicenter Studies I and II were included in this analysis. The characteristics of chronic phase patients are summarized in Table 1. Median observation time of living patients after BMT was 4.7 years. For the determination of the duration of pretransplant IFN treatment, the time when IFN was actually administered was counted. In most instances the duration of pretreatment was identical to the interval from diagnosis to BMT (median time from diagnosis to start of any treatment: 6 days, to the start of IFN treatment 18 days). The long intervals between diagnosis and BMT in some cases are mainly due to the lack of related donors and indicate unrelated donor transplantations. Very rarely, patients decided to postpone transplantation for personal reasons.

Transplant procedure.

Transplantations were performed at 13 centers in Germany (180 patients) and 3 centers in Switzerland (14 patients) according to standard procedures. Six patients were transplanted elsewhere, in the United States (4), Croatia (1), and Belgium (1). Most patients (72%) received conditioning regimens that included total body irradiation (TBI), and 28% received busulfan-based regimens without TBI. Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) prophylaxis mainly consisted of cyclosporin A in combination with methotrexate and/or anti-thymocyte globuline and prednisone (92%). Eight percent received T-cell–depleted marrows. One patient had GVHD prophylaxis with methotrexate alone.

Definitions.

Disease status was defined according to the following criteria11 13: Chronic phase ≤10% blasts in the peripheral blood or ≤15% blasts in the bone marrow, no extramedullary manifestations, no additional major cytogenetic aberrations (second Ph chromosome, trisomies 8 or 19, isochromosome 17). Blastic phase was diagnosed, if blasts and promyelocytes were more than 30% of peripheral white blood cells or more than 50% of nucleated cells in the bone marrow or if extramedullary blastic manifestations were present. Accelerated phase was diagnosed if the criteria of chronic phase were not any more and of blastic phase not yet fulfilled.

Prognostic scores.

Sokal’s score14 used age, peripheral blasts, platelet count, and spleen size at diagnosis as prognostic variables and is calculated by the formula: Sokal Index = exp[0.0116 (age −43,4) + 0.0345 (spleen size −7,51) +0.188 (Platelets/700)2 − 0.563) +0.0887 (% peripheral blasts −2.10)].

The new score15 uses peripheral eosinophils and basophils in addition to the features used by Sokal’s score, though differently weighted, and is calculated by the formula: New Prognostic Score = (0.6666 × age [0 when age <50 years; 1, otherwise] + 0.0420 × spleen size [cm below costal margin] + 0.0584 × blasts [%] + 0.0413 × eosinophils [%] + 0.2039 × basophils [0 when basophils <3%; 1, otherwise] + 1.0956 × platelet count [0 when platelets <1,500 × 109L; 1, otherwise]) ×1,000.

Data recruitment and documentation.

All pretransplant, transplantation, and follow-up data were drawn from the databases of the German CML Study Group. Donor information and additional transplant-relevant data (cytomegalovirus [CMV] status) were obtained by a separate questionnaire.

Statistical analysis.

All analyses were restricted to the 152 patients in chronic phase where survival was analyzed according to type of transplant, therapy as randomized, and therapy as actually allocated. To assess the transplantation risks of both actual treatment groups, IFN (±chemotherapy) and chemotherapy only, the risk score according to Gratwohl et al16 was applied. The score uses the major pretransplant risk factors histocompatibility, stage of disease at time of transplant, age and sex of donor and recipient, time from diagnosis to transplant, and year of transplant. The score categorizes patients into 8 risk levels, level zero representing the lowest and level 7 the highest risk. In addition, the following possible risk factors were assessed: HLA I and II compatibilities according to the methods available at transplantation, ie, including HLA-A, B, C, DR, DQ and DP, CMV status of recipient and donor, conditioning therapy, GVHD prophylaxis, drug dosage, duration of treatment, interval from discontinuation of pretransplant treatment to BMT, risk profiles according to Sokal et al14 and Hasford et al,15and features of prognostic scores before transplantation. In IFN patients, the reasons for discontinuation of IFN, the causes of death, and the hematologic response status and performance at transplantation were analyzed.

Both actual treatment groups were subdivided into 3 cohorts according to duration of pretransplant therapy: pretreatment (interval from diagnosis to transplantation) less than 1 year, 1 to 2 years, and more than 2 years. In all cohorts, the comparability of the 2 treatment groups was examined with respect to the risk factors mentioned above. The comparisons were performed by the appropriate application of the chi-square test, Fisher’s exact test, Student’s t-test, or the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test. Survival after BMT (overall) was calculated according to Kaplan-Meier. The correlation between a risk factor and survival was assessed by log-rank test and the Kaplan-Meier survival estimation or by multivariate Cox regression analysis. For the time between discontinuation of IFN and BMT the minimal P value approach provided the division of patients into 2 statistically most significant different subgroups with regard to survival time. The statistical significance was judged by log-rank test; P values were corrected due to multiple testing.15,17 18Significance level for all analyses was α = .05.

RESULTS

Patients.

Two hundred patients (197 Ph/bcr-abl–positive, 23% of a total of 856) received an allogeneic transplantation, 32% of patients with unrelated donors. At the time of transplantation, 152 Ph/bcr-abl–positive patients (77%; 78 from study I, 74 from study II) were in first chronic, 30 (15%) in accelerated, and 15 (8%) in blastic phase. Only the Ph/bcr-abl–positive patients in chronic phase were included for the detailed analysis. The transplantation rate for Ph/bcr-abl–positive patients in chronic phase was 17.8% (152 of 856), 15.1% in study I (78 of 516; 29 of 134 [21.6%] IFN, 24 of 194 [12.4%] hydroxyurea-, 25 of 188 [13.3%] busulfan-treated patients), and 21.8% in study II (74 of 340; 52 of 226 [23%] IFN ± hydroxyurea-, 22 of 114 [19.3%] hydroxyurea-treated patients). By May 31, 1998, 64 (42%) of the 152 chronic phase patients had died. Relatively more IFN-pretreated patients were transplanted in study I because, due to the later start (2.9 years) of the IFN arm and a randomization pattern of 2:1 in favor of IFN, relatively more IFN-patients were recruited in the later phase of the study. Patients recruited later had a higher chance of BMT because of the better availability of the procedure.

Pretreatment.

Randomized and allocated pretransplant therapies are summarized in Table 2. Table3 lists 16 possible transplantation risks that were analyzed to assure comparability of IFN and chemotherapy pretreated cohorts. Column 1 shows the analysis of all patients; columns 2, 3, and 4 show the analyses of patients who were treated less than 1 year, 1 to 2 years, or more than 2 years, respectively. The last column shows the analysis of IFN-pretreated patients to assure comparability of patients who did or did not receive IFN during the last 90 days before BMT. The table comprises 4 additional IFN-related parameters addressing hematologic response status, patients’ performance at the time of, or within 6 weeks, of BMT, and IFN dosage. Most possible transplantation risks (and IFN-related parameters) were distributed evenly. For 4 features in column 1, significant differences were observed (gender, Sokal index, new prognostic score, hematologic response status at BMT). Each feature was subsequently analyzed for impact on survival by log-rank test and Kaplan-Meier survival estimation or by multivariate Cox regression analysis, which showed that the uneven distribution of the 4 features had no influence on survival. In column 2 (pretreatment <1 year), a significant difference was found for 1 feature (CMV status) and a borderline value for 1 other. Also, these features as well as 2 borderline and 2 significant differences in the last column (IFN within 90 days before BMT or not) had no influence on survival. Thirteen percent of patients showed transplantation risk scores16 0 or 1, which indicate the lowest risk, 85% scores 2 to 4, and 2% scores 5 or higher. For 74% of patients, complete information was available on age, spleen size, platelet count, percentages of peripheral blasts, eosinophils, and basophils (features used for the calculation of Sokal index and new score) at the time of, or within 6 months before, transplantation. Also, these features were distributed evenly between therapy groups and between patients who did or did not receive IFN during the last 90 days before BMT.

Survival.

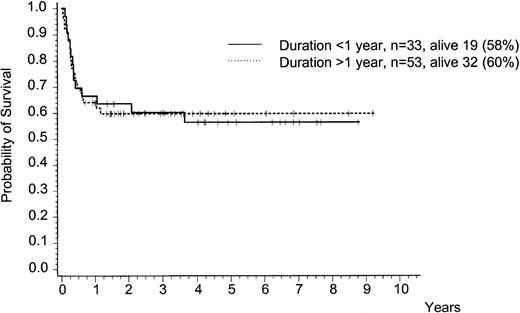

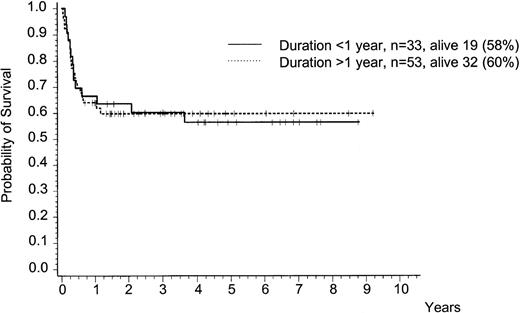

Median survival time after BMT has not been reached in chronic phase patients (7-year survival plateau at 53%). There was no significant difference between the three treatment groups. Five-year survival is 60% after hydroxyurea, 57% after IFN, and 60% after busulfan pretreatment (Fig 1A) on an intention-to-treat analysis. An additional analysis according to the treatment actually given showed similar results (5-year survival 58% after IFN and 59% after conventional chemotherapy [hydroxyurea or busulfan]). Because the survival curves after hydroxyurea and after busulfan pretreatment were not significantly different, they were combined in all further analyses. Survival outcome was similar for recipients of related (5-year survival 57%) and unrelated (5-year survival 61%) transplants (Fig 1B). 22.4% received their transplants within the first year after diagnosis. Transplant outcomes were not different between Studies I and II.

Survival of Ph/bcr-abl–positive patients after BMT in chronic phase (n = 152): (A) According to pretransplant therapy as randomized (46 hydroxyurea, 25 busulfan and 81 IFN [±chemotherapy] patients; alive by May 31, 1998: 28 [61%] hydroxyurea, 12 [48%] busulfan, and 48 [59%] IFN patients); 5-year survival after IFN pretreatment is 57% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 46 to 69), after hydroxyurea 60% (CI: 46 to 75) and after busulfan 60% (CI: 40 to 79). These differences are not significant. (B) According to type of transplant in chronic phase patients only (n = 152; 104 related, 48 unrelated transplants). Five-year survival after related transplants 57% (95% CI: 47 to 66), after unrelated transplants 61% (CI: 46 to 77).

Survival of Ph/bcr-abl–positive patients after BMT in chronic phase (n = 152): (A) According to pretransplant therapy as randomized (46 hydroxyurea, 25 busulfan and 81 IFN [±chemotherapy] patients; alive by May 31, 1998: 28 [61%] hydroxyurea, 12 [48%] busulfan, and 48 [59%] IFN patients); 5-year survival after IFN pretreatment is 57% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 46 to 69), after hydroxyurea 60% (CI: 46 to 75) and after busulfan 60% (CI: 40 to 79). These differences are not significant. (B) According to type of transplant in chronic phase patients only (n = 152; 104 related, 48 unrelated transplants). Five-year survival after related transplants 57% (95% CI: 47 to 66), after unrelated transplants 61% (CI: 46 to 77).

Survival was not different whether IFN (±chemotherapy) or chemotherapy only were administered for less or more than 1 year after diagnosis (data not shown). Duration of IFN therapy had no impact on posttransplant survival (Fig 2). There was no significant difference in transplantation outcome, if the duration of IFN pretreatment was more or less than 5 months, both after related or unrelated transplants, more or less than 1 year, or more or less than 2 years. Total IFN dosage (more or less than the median dose of 2,246 million IU) had no impact on survival after BMT either.

Survival after BMT in chronic phase (n = 86) according to duration of pretransplant IFN (±chemotherapy) treatment of more or less than 1 year. Five-year survival is 60% (95% CI: 47 to 73) and 57% (CI: 39 to 74), respectively. This difference is not significant.

Survival after BMT in chronic phase (n = 86) according to duration of pretransplant IFN (±chemotherapy) treatment of more or less than 1 year. Five-year survival is 60% (95% CI: 47 to 73) and 57% (CI: 39 to 74), respectively. This difference is not significant.

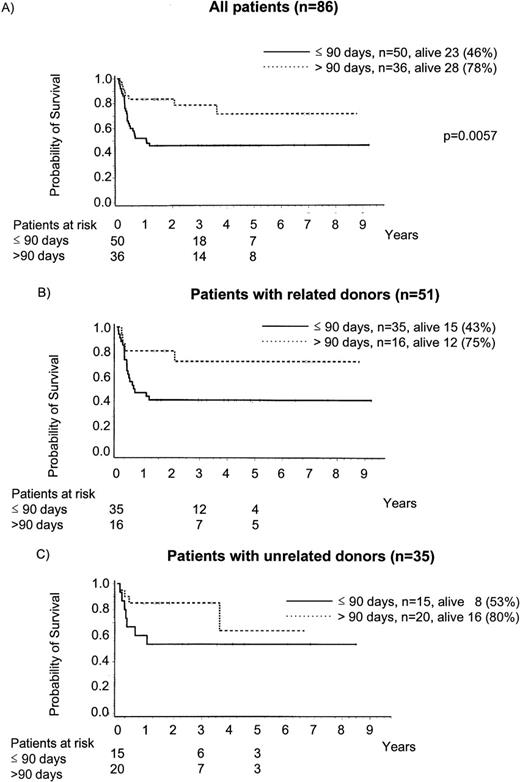

A significant negative impact of IFN on transplantation outcome was observed if IFN was administered during the last 90 days before BMT (Fig 3A). Five-year survival was 46% for the 50 patients who received IFN within 90 days before BMT and 71% for the 36 patients who did not. This difference was significant atP = .0057. Virtually identical results were obtained in recipients of related and of unrelated transplants (Fig 3B and C). Statistically significant, appropriately corrected P values could be discovered for splits between 43 and 122 days with no IFN before BMT. Of the 45 patients who discontinued IFN treatment at least 43 days before BMT, 11 died. The corresponding figures for >90 days and >122 days were 8 of 36 and 5 of 30 patients, respectively. It is evident from the survival curves that the difference is due to early mortality within the first 9 to 12 months after transplantation. Risk factors for transplantation or survival were distributed evenly between the 2 groups (Table 3, last column) or had no influence on survival. The reasons for early discontinuation of IFN were resistance to IFN in 5 patients (in 1 patient due to IFN antibodies), adverse effects in 15 patients, preparation for BMT in 15 patients, and bone marrow fibrosis in 1 patient. There was no significant difference, or no influence on survival in the case of a difference, in performance status (Karnofsky index), body mass index (weight loss), or hematological response (resistance to IFN therapy) at the time of IFN discontinuation between the two groups (Table 3, last column).

Survival after BMT in chronic phase according to interval between discontinuation of pretransplant IFN and BMT of less and more than 90 days before BMT. (A) All patients (n = 86). Five-year survival is 46% (95% CI: 32 to 60) and 71% (CI: 52 to 90), respectively. This difference is significant at P = .0057. (B) Patients with related transplants (n = 51). Five-year survival is 43% (95% CI: 26 to 59) and 73% (95% CI: 50 to 96), respectively. (C) Patients with unrelated transplants (n = 35). Three-year survival is 53% (CI: 28 to 79) and 85% (CI: 69 to 100), respectively.

Survival after BMT in chronic phase according to interval between discontinuation of pretransplant IFN and BMT of less and more than 90 days before BMT. (A) All patients (n = 86). Five-year survival is 46% (95% CI: 32 to 60) and 71% (CI: 52 to 90), respectively. This difference is significant at P = .0057. (B) Patients with related transplants (n = 51). Five-year survival is 43% (95% CI: 26 to 59) and 73% (95% CI: 50 to 96), respectively. (C) Patients with unrelated transplants (n = 35). Three-year survival is 53% (CI: 28 to 79) and 85% (CI: 69 to 100), respectively.

There was no significant difference in causes of death between patients receiving or not receiving IFN during the last 90 days before BMT. Among the 27 patients (54% of 50) with IFN discontinued ≤90 days before BMT who died, causes of death were the following: predominantly infections (10 patients), predominantly complications of GVHD (9 patients), graft failure or venoocclusive disease (VOD, 2 patients each), pulmonary insufficiency, thrombotic thrombopenic purpura, pulmonary embolism, or hemolytic uremic syndrome (1 patient each). Among the 8 patients (22% of 36) with IFN discontinued >90 days before BMT, causes of death were the following: predominantly infections (3 patients), predominantly GVHD (3 patients), VOD, and kidney failure (1 patient each).

DISCUSSION

Our data might provide an answer to the conflicting results concerning IFN pretreatment before allogeneic BMT. IFN admin- istered within 90 days before BMT adversely affects outcome. If it is withheld at least 3 months before BMT, it has no impact.

The topic addressed by our study, ie, the compatibility of the 2 current treatments of choice, is of increasing importance for the management of the majority of CML patients,19 because the treatment decision in a patient with chronic phase CML who qualifies for a potentially curative marrow transplantation is frequently difficult in view of the transplantation-related early mortality and the accumulating evidence that also IFN alters the natural course of CML and prolongs life in most patients. A trial with IFN first and a decision for transplantation only after treatment with IFN has proved unsatisfactory would be an attractive alternative for the majority of CML patients, provided IFN treatment is not harmful for subsequent BMT. At least 8 studies addressed this topic during the last 5 years: Five reports do not find any harmful effect of pretransplant IFN on transplantation outcome,6-10 but 3 reports suggest negative impacts under certain circumstances3-5: (1) IFN pretreatment longer than 1 year (n = 27) was associated with graft failure (7 patients) and other fatal transplant-related complications (≈11 patients) among patients with donors other than HLA-identical family members.3 (2) IFN pretreatment longer than 5 months (n = 48) was associated with an increased risk of severe GVHD and mortality (P = .05). Only patients who received unrelated donor transplants were reported.4 (3) IFN treatment within the last 3 months preceding BMT (n = 31) was associated with a 20% increase in transplant-related mortality.5

Because 1 goal of our randomized studies was the analysis of whether treatment with IFN had an influence on the outcome after BMT, we tested all 3 hypotheses. To minimize the potential pitfall of subgroup analyses, no new hypotheses were generated, but only published hypotheses were tested. We could not find an influence of the duration of pretransplant IFN treatment on transplantation outcome either for durations of more than 5 months, of more than 1 year, or for longer durations (more or less than 2 years). Also, we did not find a difference between related or unrelated transplants. We confirmed, however, hypothesis no. 3, which suggested that IFN treatment within 3 months preceding BMT has an adverse impact. Taking the median interval from IFN discontinuation to BMT (50 days), the results were almost identical (P = .0052). Statistically significant results were obtained for an interval of 43 to 122 days from discontinuation of IFN to BMT.

Regarding the comparison of overall outcome after BMT between the IFN and chemotherapy groups, the results confirm the 5 reports with no adverse outcome.

As most others, the 3 reports with adverse outcome were referral based and without controlled assignment of pretreatment, in contrast to our study that was conducted prospectively within randomized trials with predefined patient populations and randomly allocated pretreatments. According to the study protocols, response to drug treatment, in particular cytogenetic response to IFN, did not preclude BMT. BMT as the only potentially curative treatment option was recommended to all suitable patients who had a donor, resulting in the high transplantation rates of 19.4% and 28.5% for patients diagnosed during the periods 1983-1991 and 1991-1994, respectively.

Particular care was taken to assure that patient cohorts pretreated with IFN or with chemotherapy, or cohorts who did or did not receive IFN within 90 days before BMT, respectively, were comparable with regard to transplantation risks, both overall and according to pretreatment duration of less than 1 year, 1 to 2 years, and more than 2 years (Table 3). It is important to note that transplantation risks did not differ significantly between IFN and chemotherapy cohorts with regard to most parameters and that survival was not influenced by the few differences observed (Table 3) as assessed by multivariate Cox regression analysis. Comparisons assessing related and matched unrelated transplants did not show significant differences, which reflects the progress with unrelated transplantations also observed by others.20 The proportion of 32% unrelated transplants has to be seen in the context that transplantations with unrelated donors became generally feasible only during the later phase of this study (compare Fig 1B). The overall transplantation outcome in our chronic phase patients with 5-year survival rates of 57% to 60% compares well with other multicenter analyses covering the same period.16,21 The lack in our study of a difference in BMT outcome reported after hydroxyurea and busulfan pretreatments2 might be due to patient numbers.

Although an adverse impact of pretransplant IFN given during the last 90 days before BMT on survival outcome was suggested before,5 the magnitude of the impact that was equally observed in recipients of related and unrelated transplants came as a surprise. In chemotherapy patients an influence of the time between drug discontinuation and transplantation on survival was not observed. Considering the physiological effects of IFN on cell proliferation and immunomodulation, an effect on bone marrow and, thereby, transplantation appears reasonable.22-24 We did not observe differences of IFN resistance between IFN patients treated within 90 days of BMT or not or an influence on survival of performance status as measured by Karnofsky index or body mass index. One other study7 also analyzed the interval from IFN discontinuation to BMT, but did not find an impact on survival. Explanations might be the small sample size (n = 30) or nonrandom assignment of pretreatment. A second study4 mentions that survival of their patients was independent of the interval from IFN discontinuation to the transplant, but no details were given on length of the interval, on number of patients for whom this information was available, or on modality of pretreatment assignment.

Looking at the 5-year survival of patients who discontinued IFN >90 days before BMT (Fig 3), one could argue that IFN pretreatment per se might have a beneficial effect on the outcome after BMT, an observation supported by the results of others.3 This possibility, however, could not be substantiated by a significant difference in comparisons with the chemotherapy-pretreated cohorts.

The strong points of this study are the prospective analysis, the use of patients with randomized pretreatments, and the minimization of selection bias due to treatment according to protocol. On the basis of this study we conclude that IFN before BMT in CML does not affect outcome adversely, provided it is discontinued at least 90 days before the procedure. Clear candidates for early transplantation should not be pretreated with IFN.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The assistence of S. Röder, M. Dumke, B. Galuschek, and G. Lalla is gratefully acknowledged.

Transplantation Centers:

Basel: Kantonsspital Basel, Abteilung für Hämatologie (A. Gratwohl); Berlin: Medizinische Klinik und Poliklinik, Universitätsklinikum Charlottenburg (W. Siegert);Düsseldorf: Heinrich-Heine-Universität, KMT-Zentrum (A. Heyll); Essen: Universitätsklinik für Knochenmarktransplantation (U.W. Schaefer); Freiburg:Medizinische Universitätsklinik, KMT-Zentrum (J. Finke, W. Lange); Genf: Departement de Medicine Interne, Division d’Hematologie, (B. Chappuis); Hamburg:Universitätsklinikum, Zentrum für Knochenmarktransplantation (A. Zander); Homburg/Saar:Medizinische Universitätsklinik I (M. Pfreundschuh);Idar-Oberstein: Klinik für Hämatologie/Onkologie und Knochenmarktransplantation (A.A. Fauser); Kiel: Med. Universitätsklinik II, Kinderklinik, Knochenmarktransplantation (N. Schmitz, B. Glaß); Leipzig: Universität Leipzig, Klinik für Innere Medizin, (W. Helbig); Leuven:University Hospital, Department Hematology, (M.A. Boogaerts);München: III. Med. Klinik, Klinikum Großhadern (H.J. Kolb); Nürnberg: V. Med. Klinik, Klinikum Nürnberg, KMT-Station (H. Wandt); Seattle: Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center (R. Storb); Tübingen: Medizinische Universitätsklinik II (C. Faul); Ulm: Medizinische Klinik und Poliklinik III (D. Bunjes); Zagreb: Croatia, Department of Medicine, University Hospital Center (M. Mrsic); Zürich:Departement Innere Medizin, Universitätsspital (J. Gmür).

Participating Institutions:

Aachen: Hämatologisch-onkologische Praxis (U. Essers, H. Knechten, L. Habers); Medizinische Klinik II der RWTH (S. Handt);Aalen: Innere Abteilung, Kreiskrankenhaus (J.D. Faulhaber);Aarau: Kantonsspital, Medizinische Klinik (K. Giger, M. Wernli); Aschaffenburg: Medizinische Klinik, Klinikum (Kestel, W. Fischbach, J. Brücher); Augsburg: Zentralklinikum, II. Medizinische Klinik, (D. Hempel); Bad Saarow: Humaine Klinikum, Klinik für Innere Medizin, (M. Schultze, G. Werner);Bayreuth: Krankenhaus Hohe Warte, Medizinische Klinik (D. Seybold, A. Nippe); Basel: Abteilung für Onkologie/Abteilung für Hämatologie, Kantonsspital (A. Gratwohl, A. Tichelli, R. Herrmann); Onkologische Praxis (W. Weber);Berlin: Universitätsklinikum Rudolf Virchow, Medizinische Klinik (D. Huhn, W. Siegert, A. Neubauer, C. Busemann); Kinderklinik und Poliklinik (R. Fengler); II. Kinderklinik Berlin-Buch (W. Dörffel); Krankenhaus Moabit (K.P. Hellriegel); II. Innere Abteilung, Krankenhaus Berlin-Neukölln (A.C. Mayr, G. Middelhoff, A. Grüneisen); Onkologisch-hämatologische Schwerpunktpraxis (I. Weißenfels, R. Junkers); Hämatologisch-onkologische Schwerpunktpraxis (I. Blau, H. Ihle); Hämatologische Praxis (B.R. Suchy); Charité (K. Possinger, H.G. Mergenthaler); Bern:Inselspital (B. Lämmle, U. Bucher, G. Brun del Re, A. Tobler);Böblingen: Kreiskrankenhaus (G. Rettenmaier);Bonn: Medizinische Universitätspoliklinik (H. Vetter, Y.D. Ko); Bremen: Zentralkrankenhaus St.-Jürgen-Str. (H. Rasche, C.R. Meier, E. Brusilowski); Bremerhaven: Medizinische Klinik, St Joseph-Hospital (J. Schubert, C. Medgyesy); Cottbus:Gemeinschaftspraxis (U. von Grünhagen); Dresden:Technische Universität, Klinik für Innere Medizin (G. Ehninger, J. Mohm); Duisburg: Med. Klinik II, St Johannes-Hospital (M. Westerhausen, W. Fett, J. Eggert); Emden:Medizinische Klinik, Hans-Susemihl-Krankenhaus (F. Lindemann); Erfurt: Klinikum, Medizinische Klinik (D. Küstner); Hämatologische Praxis (J. Weniger); Internistische Praxis (U. Hauch); Erlangen: Medizinische Klinik III (J.R. Kalden, Altstidl); Eschweiler: St-Antonius-Hospital (R. Fuchs); Frankfurt: Zentrum der Inneren Medizin, Abt. f. Hämatologie u. Onkologie (D. Hoelzer, H. Martin); Onkologische Gemeinschaftspraxis (M. Fischer, F. Walther, T. Klippstein);Freiburg: Abt. Hämatologie/Onkologie, Med. Universitätsklinik (R. Mertelsmann, R. Engelhardt, F. Bross);Fürth: II. Medizinische Klinik (M. Fink);Füssen: Kreiskrankenhaus (H. Kremer); Gießen:Med. Klinik IV mit Hämatologie und Onkologie (H. Pralle, A. Käbisch); Göppingen: Klinik am Eichert, Medizinische Klinik II (E. Kurrle, T. Schmeiser); Hagen:Marien-Hospital (H. Eimermacher); Hamburg: Medizinische Univ.-Klinik, Hamburg-Eppendorf (D.K. Hossfeld); Hämatologisch-onkologische Praxis Altona (U.R. Kleeberg); Allgemeines Krankenhaus Barmbek (U. Müllerleile); Allgemeines Krankenhaus Altona (K. Mainzer, D. Braumann); Allgemeines Krankenhaus St Georg (R. Kuse, C. zur Verth); Internistische Gemeinschaftspraxis (A. Mohr); Hannover: Pathologisches Institut und Institut f. Klinische Immunologie der MHH (A. Georgii, T. Buhr); Institut für Klinische Immunologie der MHH (H. Deicher, P. von Wussow);Heidelberg: Institut für Humangenetik (C.R. Bartram); Med. Univ. Klinik V (W. Hunstein, U. Räth, M. Bentz);Herford: Kreiskrankenhaus, Medizinische Klinik II (U. Schmitz-Huebner, U. Horstmeier); Kaiserslautern:Städtisches Krankenhaus, Medizinische Klinik (H. Kreiter);Karlsruhe: II. Med. Klinik, Klinikum (J.T. Fischer);Kempten: Innere Abteilung, Stadtkrankenhaus (V. Hiemeyer, Schläfer); Kiel: Med. Klinik I und II, Universität Kiel (H.D. Bruhn, H. Löffler, W. Gassmann); Köln:Universitätsklinikum, I. Medizinische Klinik (V. Diehl, P.D. Wickramanayake); Pathologisches Institut, Universität Köln (J. Thiele); Praxisgemeinschaft (R. Zankovich); Lebach:Caritas-Krankenhaus (D. Hufnagl, T. Seel); Lemgo: Klinikum Lippe (H.-P. Lohrmann); Lindenfels/Odenwald: Luisenkrankenhaus (J. Hesselmann); Ludwigshafen: St Marienkrankenhaus, Medizinische Klinik (H. Weiss, A. Seifert); Lüneburg:Gemeinschaftspraxis (B. Goldmann); Lugano: Medicina interna ed ematologia FMH (E. Beck); Mannheim: III. Medizinische Klinik, Klinikum Mannheim, Universität Heidelberg (R. Hehlmann, W. Queißer, A. Hochhaus, U. Berger, A. Reiter); Mülheim a.d. Ruhr: Evangelisches Krankenhaus, Medizinische Klinik (J. Freise, G. Linnemann); München: III. Med. Klinik, Klinikum Großhadern (W. Wilmanns, H.-J. Kolb, A. Muth); Med. Klinik Innenstadt (P.G. Scriba, B. Emmerich, J. Hohnloser); Med. Poliklinik (N. Zöllner, M. Jahn-Eder, B. Heinrich); Städtisches Krankenhaus Schwabing (W. Kaboth, C. Nerl); Städtisches Krankenhaus München-Harlaching (R. Hartenstein, N. Brack); Krankenhaus München-Neuperlach (M. Garbrecht); Klinikum rechts der Isar (J. Rastetter, W.E. Berdel, M. Perker); Institut für Med. Informationsverarbeitung, Statistik und Biomathematik der LMU und Biometrisches Zentrum für Therapiesstudien (K.Überla, J. Hasford, H. Ansari, M. Pfirrmann); Münchner Onkologische Praxis (L. Böning, F.-J. Tigges, W. Abenhardt); Hämatologische Praxis (A. Wohlrab); Hämatologische Praxis (R. Zettl); Münster:Kinderklinik, Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität (J. Wolff, B. Rath); Neuruppin: Medizinische Klinik B, Klinikum (D. Nürnberg, H. Eggebrecht); Nürnberg: Zentrum Innere Medizin (W. Brockhaus); V. Medizinische Klinik, Klinikum (W.M. Gallmeier, C. Falge); Oberhausen: Gemeinschaftspraxis (A. Brunöhler); Oldenburg: Städtische Kliniken, Innere Medizin (H.J. Illiger, F. del Valle); Penzberg:Städtisches Krankenhaus (K. Ranft); Ravensburg: Med. Klinik, St Elisabethen Krankenhaus (G. Meuret, A. Egger);Regensburg: Krankenhaus der Barmherzigen Brüder (E.-D. Kreuser, W. Wellens); Rheine: Jakobi-Krankenhaus (D. Bauer);Schwäbisch-Hall: Diakonie-Krankenhaus (H.H. Heißmeyer, T. Geer); St Gallen: Onkologische Abteilung, Kantonsspital (T. Cerny, L. Schmid); Traunstein:Stadtkrankenhaus, Onkologische Abteilung (A. Diestelrath); Ulm:Medizinische Universitätsklinik III (H. Heimpel, M. Grießhammer); Institut f. Humangenetik (T.M. Fliedner, B. Heinze); Immunhämatologisches Labor der Medizinischen Klinik und Poliklinik (O. Prümmer); Waldbröl:Kreiskrankenhaus, Medizinische Klinik (L. Labedzki); Wiesbaden:Klinikum der Landeshauptstadt (N. Frickhofen, H.-G. Fuhr);Wilhelmshaven: St Willehad-Hospital (W. Augener);Würzburg: Med. Poliklinik der Universität (K. Wilms, M. Wilhelm, H. Rückle-Lanz).

Supported by grants from the German Bundesminister für Forschung und Technologie, Förderkennzeichen Nr. 01ZW044, 01ZP9001, and 01ZW8503, from the Süddeutsche Hämoblastosegruppe (SHG) through a grant from Hoffmann-La Roche to the SHG, and from the Forschungsfonds der Fakultät für Klinische Medizin, Mannheim.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Address reprint requests to Rüdiger Hehlmann, MD, III. Medizinische Universitätsklinik, Klinikum Mannheim, Universität Heidelberg, Wiesbadenerstr. 7-11, 68305 Mannheim, Germany; e-mail: R.Hehlmann@urz.uni-heidelberg.de.

![Fig. 1. Survival of Ph/bcr-abl–positive patients after BMT in chronic phase (n = 152): (A) According to pretransplant therapy as randomized (46 hydroxyurea, 25 busulfan and 81 IFN [±chemotherapy] patients; alive by May 31, 1998: 28 [61%] hydroxyurea, 12 [48%] busulfan, and 48 [59%] IFN patients); 5-year survival after IFN pretreatment is 57% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 46 to 69), after hydroxyurea 60% (CI: 46 to 75) and after busulfan 60% (CI: 40 to 79). These differences are not significant. (B) According to type of transplant in chronic phase patients only (n = 152; 104 related, 48 unrelated transplants). Five-year survival after related transplants 57% (95% CI: 47 to 66), after unrelated transplants 61% (CI: 46 to 77).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/94/11/10.1182_blood.v94.11.3668/4/m_blod42331001x.jpeg?Expires=1769432603&Signature=Ibbh13W7-JoTAqH8G3WzgUxYtUD45eGTdaw9wDZ6x9HXN9PBIIaCIHluEmb6qnuBE4OV~M6-JDi-NjoMYQpDNHFzru1U~9yFcmLl9qHSrZSHyaHDOuEoMtZuNWIPOHHxGipymTyhR8VvQxLyfHslzw-SdydeyYeZN-xBCfGnqsSoNISv9Um1R1mnIDTyYLrch3l0HrP7geVHVFnXbomweKtBkiSxc0DdRCZU0dNxXYZhYrtjrVQ3ST6esrModVKTydn4K93inA~hodW9UND215SSyJltBsytYXXGvdc4HpZ2SzwDSz7c~tJ0r0w31h9q6XG~L-Mlkba84Rr0efTnpA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Fig. 1. Survival of Ph/bcr-abl–positive patients after BMT in chronic phase (n = 152): (A) According to pretransplant therapy as randomized (46 hydroxyurea, 25 busulfan and 81 IFN [±chemotherapy] patients; alive by May 31, 1998: 28 [61%] hydroxyurea, 12 [48%] busulfan, and 48 [59%] IFN patients); 5-year survival after IFN pretreatment is 57% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 46 to 69), after hydroxyurea 60% (CI: 46 to 75) and after busulfan 60% (CI: 40 to 79). These differences are not significant. (B) According to type of transplant in chronic phase patients only (n = 152; 104 related, 48 unrelated transplants). Five-year survival after related transplants 57% (95% CI: 47 to 66), after unrelated transplants 61% (CI: 46 to 77).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/94/11/10.1182_blood.v94.11.3668/4/m_blod42331001x.jpeg?Expires=1769432604&Signature=pVBfxVz9hRwP~on~np-qCVrh8vwZeIz7gOVip4dKOJ5J0qL-8pDi6JAWz5IWprjke2hMuQy5TqNrikaiwlkzE1k2ig1m01l59PfZ1YjaNejWK1NifaRTgmMOwGxEtC3EqRupa9nZhpx~0rypirXra3DU2RKKIZdIg4sLIuQi3hXtaAIRGhB7x9~9GQ~FWjCfG0aqGTjaErrMIBMmoviGPx7e1ukPgehrrO4MZvAzt70ncYc36BpUbT2dfD8GrO6DuS5aLeJoOSdhgPdhmi8OqPuyV8e5h~aClWc8bhhbLRFtSl80~KP3rn1ZazyEcPYWfoqQEsdQdppI13OAYGVpgA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)