Abstract

Liposomes have been proposed as a vehicle to deliver proteins to antigen-presenting cells (APC), such as dendritic cells (DC), to stimulate strong T cell–mediated immune responses. Unfortunately, because of their instability in vivo and their rapid uptake by cells of the mononuclear phagocyte system on intravenous administration, most types of conventional liposomes lack clinical applicability. In contrast, sterically stabilized liposomes (SL) have increased in vivo stability. It is shown that both immature and mature DC take up SL into neutral or mildly acidic compartments distinct from endocytic vacuoles. These DC presented SL-encapsulated protein to both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in vitro. Although CD4+ T-cell responses were comparable to those induced by soluble protein, CD8+ T-cell proliferation was up to 300-fold stronger when DC had been pulsed with SL-encapsulated ovalbumin. DC processed SL-encapsulated antigen through a TAP-dependent mechanism. Immunization of mice with SL-encapsulated ovalbumin led to antigen presentation by DC in vivo and stimulated greater CD8+ T-cell responses than immunization with soluble protein or with conventional or positively charged liposomes carrying ovalbumin. Therefore, the application of SL-encapsulated antigens offers a novel effective, safe vaccine approach if a combination of CD8+and CD4+ T-cell responses is desired (ie, in anti-viral or anti-tumor immunity).

Introduction

One of the major obstacles in vaccine research is the fact that protein antigens are usually poorly presented on major histocompatibility class I molecules and therefore fail to induce strong CD8+ T-cell responses. To overcome this problem, liposomes have been proposed as antigen-delivery vehicles (reviewed in1,2). Unfortunately, the antigen delivery potential of conventional liposomes in vivo is limited because of their rapid elimination from the peripheral circulation by resident macrophages (MΦ) of the mononuclear phagocyte system (MPS), leading to their lysosomal localization in liver and spleen.3,4 The rate of liposome clearance strongly depends on several physical parameters, including the size and surface charge of the liposomes.5-8

A new type of liposome, sterically stabilized liposomes (SL), contains large molecules, such as polyethylene glycol (PEG), in its membrane and is, therefore, less efficiently taken up by myelomonocytic cells than conventional liposomes.9,10 PEG interferes with the binding of serum proteins to the liposome surface and the subsequent adhesion of SL to cells of the MPS, considerably reducing the clearance of SL, irrespective of their surface charge.8,11 As a result, SL exhibit a serum half-life up to approximately 48 hours in humans and animal models,12,13 compared to only a few hours for conventional liposomes. In addition to their prolonged circulation, they can extravasate to the skin or to sites of trauma (inflammation, tumors) that are characterized by capillary leakage.12 14

Based on their biologic stability and their unique distribution, SL may prove to be more effective than other forms of liposomes in delivering antigens to antigen-presenting cells (APC), such as immature dendritic cells (DC), residing in the periphery of the body. Once immature DC pick up antigens, they migrate to the regional lymph nodes (LN).15,16 On arrival in the LN, they display a mature phenotype and present antigens to lymphocytes, efficiently activating naive and memory T-cell and B-cell responses.16 Recent advances in cell culture technology have facilitated the generation of large numbers of immature and mature DC from precursor cells in the peripheral blood. Ex vivo–generated antigen-pulsed DC are being investigated for their possible immunostimulating or immunotherapeutic value.

Because of the potential advantages of SL in immunization strategies, we examined the impact of combining SL with potent antigen-presenting DC. We documented the uptake and intracellular processing of SL by immature and mature DC and the capacity of DC to present SL-encapsulated antigens in vitro and in vivo. We observed that SL are taken up and processed by both immature and mature DC into neutral intracellular sites, most likely the cytoplasm. Although CD4+ T cells are activated by DC presenting SL-encapsulated proteins, there is much more efficient presentation of SL-encapsulated protein antigen by DC to CD8+ T cells in vitro and in vivo. This far exceeded the CD8+ T cell–responses induced by soluble protein or antigen encapsulated in conventional or positively charged liposomes. In addition, in vivo antigen-presenting activity to CD8+ T cells after subcutaneous injection of SL-encapsulated antigen was exclusively confined to the CD11c+ DC subset. Therefore, these results encourage the development of immunization strategies using SL-encapsulated proteins.

Materials and methods

Culture media

DC were generated in RPMI 1640 (Cellgro; Fisher Scientific, Springfield, NJ), supplemented with 2 mmol/L L-glutamine (GIBCO-BRL Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY), 50 μmol/L 2-mercaptoethanol (2-ME; Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO), 10 mmol/L HEPES (GIBCO-BRL), penicillin (100 U/mL)–streptomycin (100 μg/mL) (GIBCO-BRL), and 1% human plasma (heparinized). To generate MΦ, RPMI 1640 was supplemented with 2 mmol/L L-glutamine, 50 μmol/L 2-ME, 10 mmol/L HEPES, penicillin (100 U/mL)–streptomycin (100 μg/mL), 10% fetal bovine serum (BioWhittaker, Walkersville, MD), and 2.5% autologous human serum.

Medium for mouse cells was RPMI 1640, supplemented with 2 mmol/L L-glutamine, 50 μmol/L 2-ME, penicillin (100 U/mL)–streptomycin (100 μg/mL), and 5% fetal calf serum (Atlanta Biologicals, Norcross, GA).

Cells

Human DC and T cells.

Peripheral human blood was collected in heparinized syringes. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were separated by centrifugation on Ficoll-Hypaque (Amersham Pharmacia AB, Uppsala, Sweden). T cells were removed by incubation with neuraminidase (Calbiochem-Behring, La Jolla, CA)-treated sheep red blood cells and subsequent centrifugation on Ficoll-Hypaque, or by adherence at 8 × 106 cells/well in a 6-well tray (Falcon, Lincoln Park, NY) for 1 hour at 37°C. T cell-depleted populations were then cultured for 7 days in the presence of 100 U/mL IL-4 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) and 1000 U/mL granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) (Immunex, Seattle, WA) to generate immature DC. To generate mature DC, 50% of the medium was substituted by monocyte-conditioned medium (MCM) on day 7, and cells were cultured for another 2 days.17 MCM was generated as previously described18 with minor modifications. Briefly, immunoglobulin-coated bacteriologic dishes (Falcon) were prepared by the addition of 4 mL of 100 μg/mL phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) human γ-globulin (Bayer, Elkhart, IN) and incubated for 10 minutes at room temperature. The dishes were washed 4 times with PBS, 9 × 107 PBMC were added in 10 mL medium, and the dishes were incubated for 1 hour at 37°C. All nonadherent cells were removed, fresh medium was added, and the medium was collected after incubation for 24 hours at 37°C, filtered, and frozen before use.

The phenotype of DC was routinely monitored by FACS using anti-HLA-DR-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry Systems [BDIS], San Jose, CA) versus anti-CD25-phycoerythrin (PE; BDIS), CD83-PE (Coulter, Miami, FL), CD86-PE (PharMingen, San Diego, CA), and CD14-PE (BDIS). Immature DC typically were HLA-DR++, CD86+++, CD14weak, and CD83−/weak, whereas mature DC were HLA-DR+++, CD86++++, CD25++, CD83++, and CD14−.

For some experiments DC were separated into immature CD83−and mature CD83+ cells by cell sorting using a FACStarPLUS (Becton Dickinson, Mountainview, CA) after incubation with unconjugated anti-CD83 (Coulter), followed by incubation with goat-antimouse FITC (Cappel Labs, Organon Teknika, Durham, NC). T cells were either used as bulk T cells or stained with anti-CD4-PE and anti-CD8-PE and sorted into CD4− and CD8− small cells.

Human MΦ.

MΦ were prepared by the plastic adherence method as previously described.19 Briefly, PBMC were cultured at 4 to 8 × 106 cells/mL in 1.5 mL/well in a 24-well flat-bottom tray. Supernatant containing nonadherent cells was aspirated at day 2, and 2 mL fresh medium was added. After another 3 days, remaining nonadherent cells were gently washed off, and the medium was replaced by fresh medium. MΦ was harvested and used after 7 to 9 days of culture. They were HLA-DR+, CD86++, CD14++, and CD83−.

Mouse DC.

Mouse bone marrow–derived DC (BmDC) were generated from C57/BL6 mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) or were transporter-associated with antigen-processing TAP1, knock-out (TAP1−/−) mice20 (kindly provided by Dr Jiri Trcka, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Institute, New York, NY) following a standard protocol.21 Briefly, bone marrow cells were cultured in the presence of GM-CSF (100 U/mL) for 6 days, with intermittent feeding. At day 6, immature DC were harvested and recultured in GM-CSF–containing medium in new 6-well trays in 3- to 4-mL medium at 1 × 106 cells/mL for another 48 hours to allow further maturation.

Mouse CD8+ T cells.

To obtain ovalbumin (OVA)-specific T cells, single-cell suspensions of LN and spleens were prepared from 6- to 8-week-old, OVA-specific T-cell receptor transgenic mice (OT-1) with a T-cell specificity for an octamer peptide from OVA (OVA257-264) in the context of H-2Kb.22 To remove non-T cells, the cells were incubated with antibodies directed against MHC class II (clone M5/114; ATCC), B220 (clone RA3-6B2; ATCC), and macrophages (clone F4/80; ATCC) on ice for 30 minutes. Cells were washed 3 times with medium and incubated with goat-antirat immunoglobulin Dynabeads (Dynal, Oslo, Norway) for an additional 30 minutes at 4°C. Non-T cells were removed by applying a magnetic field, and remaining T cells were collected. The population comprised 95% T cells (CD8α+, CD3+, MHC-II−) as confirmed by FACS (all antibodies were from PharMingen).

Preparation of liposomes

Cholesterol was obtained from Sigma, and PEG-PE, POPC, and DOTAP/DOPE (1:1) were obtained from Avanti (Avanti Polar Lipids, Alabaster, AL). The membrane lipid composition of SL was cholesterol:POPC:PEG-PE (2:3:0.3 mol ratio), that of conventional liposomes was cholesterol:POPC (2:3 mol ratio), and that of positively charged liposomes was DOTAP:DOPE (1:1 mol ratio). Liposomes of 100-nm diameter were prepared as previously described.23,24Briefly, thin films of lipid were prepared by rotor evaporation of the above lipid mixtures (50 μmol total phospholipid) in a round-bottom glass flask. The lipid films were hydrated with 1 mL solution containing tetanus toxoid (TT) (Statens Seruminstitut, Copenhagen, Denmark) or OVA (Sigma) at a concentration of 1 mg/mL or 2 mg/mL, respectively, and the flask was rotated slowly for 2 hours at 55°C. The formed liposomes were extruded 20 times through polycarbonate filters of decreasing diameters (0.6, 0.2, 0.1 μm) using a Mini Extruder (Avanti Polar Lipids). The liposomes were then separated from nonencapsulated antigen by size-exclusion chromatography (2 passages on a 15 × 1.5 cm column of Sepharose 4B [Sigma]). The concentration of encapsulated antigen was determined by subjecting liposomes (5, 10, 30 μL) to SDS-PAGE electrophoresis in parallel with known amounts of antigen (0.5, 1, 2.5, 5 μg) and visualizing the protein by Coomassie blue staining. The density of the bands was determined by gel scanning and densitometry analysis using the Alpha Imager 2000 (Alpha Innotech, San Leandro, CA). Encapsulation of the pH-sensitive, water-soluble fluorescent probe (HPTS; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR), was performed as previously described.25-27

Incubation of DC and MΦ with fluorescent liposomes

DC and MΦ were plated in 96-well and 24-well flat bottom trays, (Linbro; ICN Biomedicals, Aurora, OH) at 105cells/well. Various concentrations (100-500 μmol/L) of SL containing HPTS were added to triplicate wells for different lengths of time (up to 48 hours) at 37°C. No cell toxicity was observed for the highest SL concentration and the maximum incubation period. Cells were harvested and washed 3 times in DPBS containing 5 mmol/L glucose (Sigma). Cell numbers were determined, and cells were resuspended at 106 cells/mL in DPBS containing 5 mmol/L glucose and plated in 96-well round-bottom trays (Linbro) at 105 cells/well. Plates were centrifuged to concentrate the cells in the center of the wells, and the fluorescence intensity (counts per second) associated with the cell pellet was recorded at 405 and 450 nm using a Biolumin 960 (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA). The fluorescence associated with the same number of cells incubated with empty SL (autofluorescence) was subtracted from that associated with cells incubated with HPTS-containing SL (HPTS-SL). To obtain information on the pH of the site occupied by SL, indicating the intracellular fate of SL, the fluorescence emission ratio at excitation wavelengths of 450 and 405 nm was determined as previously described.25 26 At these 2 excitation wavelengths, the fluorescence emission spectrum from HPTS exhibits 2 peaks. The intensity of the former peak is highly susceptible to the pH and becomes 0 at pH values below 6.0. In contrast, the intensity of the latter peak at 405 nm slightly increases when the pH decreases below 6.0. When most of the SL associated with the cells are located in cellular compartments whose pH is greater than 6.0 on the cell surface or the cytoplasm or in early endosomes, the 450 nm/405 nm fluorescence ratio is greater than 1. In contrast, when most SL are located in intracellular vacuoles whose pH is less than 6.0, such as lysosomes, the 450 nm/405 nm fluorescence ratio is less than 1. Therefore, by monitoring the 450 nm/405 nm fluorescence ratio, the intracellular fate of SL can be estimated for each cell type used.

The uptake of HPTS-SL by DC was visualized as follows. Cells were incubated with HPTS-SL as described above. In some experiments acridine orange (Aldrich, Milwaukee, WI) was added at 2 μg/mL for the last 30 minutes of incubation.28 After they were washed extensively to eliminate free SL, cells were mounted on glass slides and covered with a coverslip. Slides were monitored using an Olympus BH2 series microscope (Olympus, Melville, NY) equipped with a reflective light fluorescence attachment. Two standard excitation filter cubes were used, one exciting in a violet band (350-410 nm) and the other at a narrower blue excitation (450-490 nm), and photographs were taken.25 26 Uptake of HPTS-SL by MΦ was visualized as for DC, except that during MΦ preparation, the cells were allowed to differentiate directly onto glass coverslips.

Confocal immunofluorescence microscopy

Immature and mature DC were incubated with HPTS-SL for 24 hours, SL were washed out, and cells were seeded in serum-free RPMI into poly L-lysine (Sigma)–coated Lab Tek (Nunc, Naperville, IL) tissue culture chambers.29 After the cells were attached to the slides (1-2–hour incubation at 37°C), the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde/PBS (wt/vol) for 20 minutes at room temperature and permeabilized for 15 minutes at room temperature by incubation with permeabilization buffer—RPMI containing 10% normal goat serum (Gibco), 0.05% saponin (Sigma), and 10 mmol/L glycine (Sigma). Thereafter, cells were incubated for 45 minutes at room temperature with antibodies against CD71 (transferrin receptor), CD107a (lysosomal-associated membrane protein 1 [LAMP-1]), HLA-DR, or isotype controls (all obtained from PharMingen), respectively. After 2 washes with permeabilization buffer, cells were incubated for 45 minutes with Texas red-labeled goat-antimouse secondary reagents (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA), mounted with aquamount (PolyScience, Niles, IL), and examined by confocal laser scanning microscopy (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany).

TT-specific proliferation assays

DC were cultured for 24 hours in the presence of SL-encapsulated TT (TT-SL) or soluble TT (sTT) at a concentration of 2 μg/mL or empty control liposomes (based on lipid concentration). The antigen was washed out, and 104 DC were cocultured with 105syngeneic T cells in a 96-well flat-bottom tray. Where indicated, DC at a range of doses were cultured with 105 syngeneic T cells in the presence of 0.2 to 2 μg/mL of sTT, TT-SL, or empty SL, respectively. Proliferation was measured on day 5 by measuring the incorporation of (3H)-thymidine (3H-TdR) at a concentration of 1 μCi/well during the last 8 hours of culture.

OVA-specific proliferation assays

Mouse BmDC at day 7 were cultured for 12 hours in the presence of SL-encapsulated OVA (OVA-SL; OVA concentration, 10 μg/mL), empty SL (based on lipid concentration), or 10 μg/mL soluble OVA (sOVA). Nonadherent, pulsed DC were then harvested, washed 3 times, and cocultured in graded doses with 3 × 105 CD8+T cells/well in 96-well flat-bottom trays overnight. T-cell proliferation was assayed by adding 3H-TdR (1 μCi/well) to the cultures after 36 hours, and incorporation of radioactivity during the final 12 hours of culture was determined by scintillation counting.

In vivo immunization with OVA

Two C57Bl/6 mice were injected subcutaneously with 8 μg OVA total into the hindfoot pads. They received OVA-SL, OVA in positively charged liposomes, OVA in nonstabilized (conventional) liposomes, OVA as soluble protein, or OVA as soluble protein mixed with empty SL (based on the lipid concentration of OVA-SL). In addition, 2 animals received empty SL only based on the lipid concentration. After 5 days, all animals were boosted with the same antigen preparation received initially. Five days later, popliteal and inguinal LN were removed. The LN cell suspensions of the 2 animals from each group were pooled, and the CD8+ T cells were purified by magnetic beading. Then 2.5 × 105 CD8+ T cells were incubated with 1.5 × 104 to 3 × 104 BmDC that had been incubated with OVA-SL (10 μg/mL) for 12 hours, and T-cell proliferation was measured in a standard proliferation assay (see above).

To elucidate which type of APC presents SL-encapsulated antigen in vivo, draining and nondraining LN from mice injected subcutaneously with 10 μg OVA-SL were removed 3 days after injection. T and B cells were removed from single-cell suspensions by magnetic beading using anti-murine CD5 and CD19 Dynabeads (Dynal), respectively, and resultant populations were separated into CD11c+ and CD11c− fractions using antimurine CD11c magnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA). These cells were applied in graded doses as APCs to 3 × 105 T cells from OT-1 mice without further addition of antigen, and T-cell proliferation was determined on day 3 (as above).

Results

Uptake and compartmentalization of fluorescently labeled SL by DC and MΦ

To appreciate the interactions of SL with DC, we first measured the uptake and intracellular localization of fluorescent SL using fluorometric techniques.25 26 DC (both immature and mature) were compared to MΦ because the latter are known to phagocytose very efficiently. Table 1demonstrates typical results after a 24-hour incubation of cells with HPTS-SL. Similar results were obtained at 3 hours and 48 hours (data not shown). DC took up considerable amounts of SL but less (lower fluorescence intensity) and more slowly than MΦ. In addition, determination of the 450 nm/405 nm fluorescence ratio indicated that both immature and mature DC processed SL to cellular sites with a neutral or mildly acidic pH, whereas MΦ processed them into compartments with acidic pH.

The potentials of mature and immature DC to take up SL-encapsulated antigens were more precisely compared. Immature DC were cultured for 18 hours in MCM, and cells were separated into CD83− immature and CD83+ mature DC. When these populations were incubated with HPTS-SL for 24 hours, SL were taken up equally well by both CD83− and CD83+ DC (Table2).

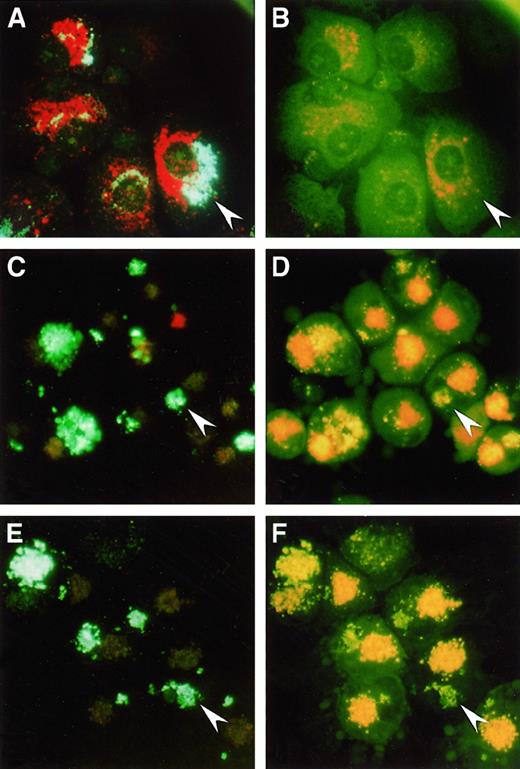

The fate of SL in DC versus MΦ could be visualized by incubation of the cells with HPTS-SL and staining with acridine orange, which accumulates in and stains acidic intracellular compartments.30 Analysis using fluorescent microscopy revealed that in MΦ, HPTS-SL, and acridine orange were colocalized (Figure 1A) and that most HPTS fluorescence was invisible at 490 nm (Figure 1B), indicating that most of the SL were in acidic lysosomal compartments. In contrast, in both mature (Figure 1C-D) and immature DC (Figure 1E-F), acridine orange and SL could be clearly distinguished in separate intracellular locations, and the HPTS fluorescence intensities at both 405 and 490 nm were comparable. Thus, the results confirmed our previous findings that DC process SL into sites with neutral or mildly acidic pH.

Uptake of HPTS-SL and acridine orange

by human Mφ (Α, Β), mature DC (C, D), and immature DC (E, F). Cells were incubated with HPTS-SL for 24 hours, and acridine orange was added for the last 30 minutes of culture. Cells were washed and mounted on a glass slide, and photographs were taken under a fluorescence microscope at an excitation of 350 nm to 410 nm (left) and 450 nm to 490 nm (right), respectively (magnification, 400×). Arrowheads highlight HPTS-SL in each panel; note that in Mφ most of the HPTS-SL are colocalized with acridine orange and not visible at 450 nm to 490 nm, whereas SL in DC are separated from acridine orange and visible at both wavelengths.

Uptake of HPTS-SL and acridine orange

by human Mφ (Α, Β), mature DC (C, D), and immature DC (E, F). Cells were incubated with HPTS-SL for 24 hours, and acridine orange was added for the last 30 minutes of culture. Cells were washed and mounted on a glass slide, and photographs were taken under a fluorescence microscope at an excitation of 350 nm to 410 nm (left) and 450 nm to 490 nm (right), respectively (magnification, 400×). Arrowheads highlight HPTS-SL in each panel; note that in Mφ most of the HPTS-SL are colocalized with acridine orange and not visible at 450 nm to 490 nm, whereas SL in DC are separated from acridine orange and visible at both wavelengths.

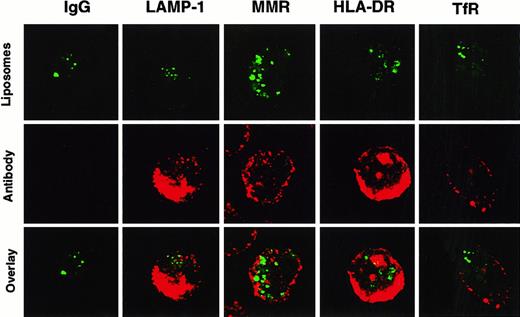

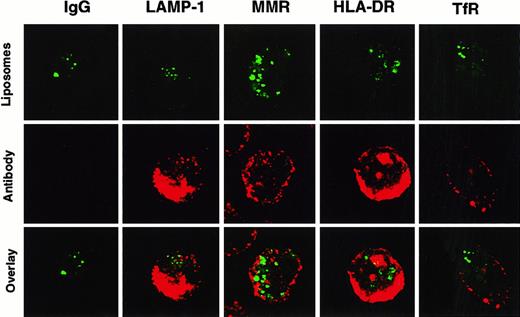

Confocal microscopy was performed to more accurately localize where SL were stored in DC. After incubation with HPTS-SL, cells were stained with monoclonal antibodies against different cellular antigens such as the transferrin receptor and the macrophage mannose receptor (used to visualize early endosomal compartments), LAMP-1 (to visualize late endosomal and early lysosomal compartments), and HLA-DR (to visualize MHC class II compartments) (Figure2). These studies showed that SL were not colocalized with any of these known cellular compartments. Hence, most of the liposome content was either located in the cytoplasm or in a previously unidentified neutral compartment, and only small amounts gained access to the lysosomal pathway.

Non-colocalization of HPTS-SL with various cellular compartments in DC.

Human DC were incubated with HPTS-SL for 24 hours. After incubation, SL were washed out, and cells were mounted on slides and stained intracellularly (for details, see “Materials and methods”) with control IgG or antibodies against LAMP-1, the macrophage mannose receptor (MMR), MHC class II (HLA-DR), and the transferrin receptor (TfR). Results are shown as HPTS-SL only (excitation for green, top), antibody staining (excitation for red, middle), and the computerized overlay of these pictures (bottom). Yellow in the bottom panels indicates colocalization of green and red (magnification, 1000×).

Non-colocalization of HPTS-SL with various cellular compartments in DC.

Human DC were incubated with HPTS-SL for 24 hours. After incubation, SL were washed out, and cells were mounted on slides and stained intracellularly (for details, see “Materials and methods”) with control IgG or antibodies against LAMP-1, the macrophage mannose receptor (MMR), MHC class II (HLA-DR), and the transferrin receptor (TfR). Results are shown as HPTS-SL only (excitation for green, top), antibody staining (excitation for red, middle), and the computerized overlay of these pictures (bottom). Yellow in the bottom panels indicates colocalization of green and red (magnification, 1000×).

Presentation of SL-encapsulated antigen by DC to CD4+T cells

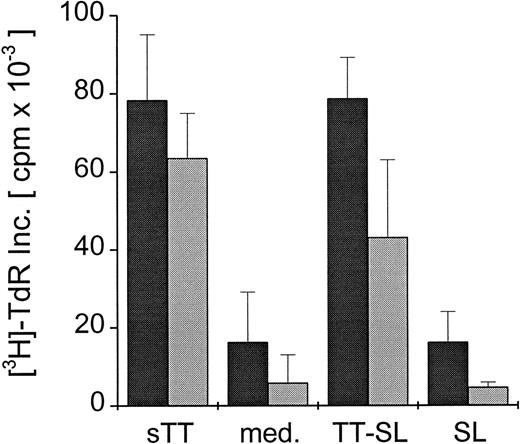

To test whether any SL-encapsulated antigen went into the lysosomal pathway of DC to be processed and presented to CD4+ T cells, DC were generated from PBMC from human donors known to be responsive to TT. Mature DC were pulsed for 24 hours with TT-SL or sTT (2 μg TT/mL) and cultured with syngeneic T cells, and the TT-specific proliferative responses were measured. As shown in Figure 3, mature DC were able to present both SL-encapsulated TT and soluble protein to T cells, mediating comparable T-cell proliferative responses. When similar assays were set up with bulk T cells, sorted CD4- or CD8-depleted cells, only CD8-depleted or bulk T cells proliferated (data not shown).

CD4+ T-cell proliferation induced by presentation of SL-encapsulated tetanus toxoid.

Mature human DC were pulsed with either soluble (sTT) or encapsulated tetanus toxoid (TT-SL) at 2.0 μg/mL for 24 hours. DC cultured in medium alone (med.) or pulsed with empty SL (SL, based on lipid concentration) were included as controls. Antigen was washed out, and DC were cocultured with 1 × 105 syngeneic T cells in a ratio of 1:10 (dark gray bars) or 1:30 (light gray bars). T-cell proliferation was monitored by measuring the uptake of thymidine, and mean cpm × 10−3 ± SEM of triplicate cultures from a representative experiment are shown.

CD4+ T-cell proliferation induced by presentation of SL-encapsulated tetanus toxoid.

Mature human DC were pulsed with either soluble (sTT) or encapsulated tetanus toxoid (TT-SL) at 2.0 μg/mL for 24 hours. DC cultured in medium alone (med.) or pulsed with empty SL (SL, based on lipid concentration) were included as controls. Antigen was washed out, and DC were cocultured with 1 × 105 syngeneic T cells in a ratio of 1:10 (dark gray bars) or 1:30 (light gray bars). T-cell proliferation was monitored by measuring the uptake of thymidine, and mean cpm × 10−3 ± SEM of triplicate cultures from a representative experiment are shown.

Because both immature and mature DC take up similar amounts of SL (Table 2), the capacities of immature and mature DC to present SL-encapsulated antigen to CD4+ T cells were compared. Immature DC were cultured for 18 hours in MCM, sorted into CD83+ and CD83− DC, and cultured with syngeneic T cells in the presence of TT-SL (2 μg TT/mL) or empty control liposomes. Both CD83+ and CD83− DC presented antigen to T cells without considerable differences (Table3).

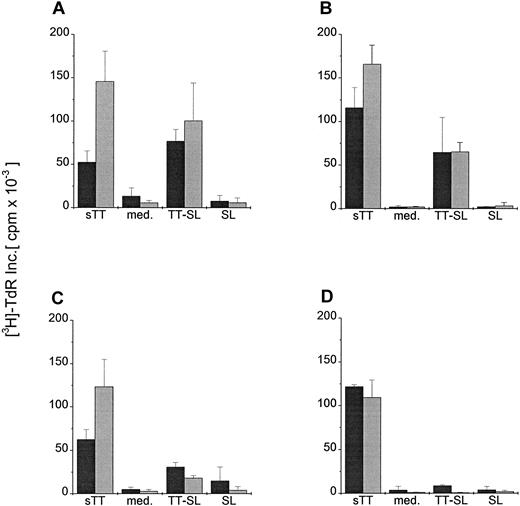

To further investigate whether lower antigen concentrations or DC:T cell ratios might reveal more subtle differences between DC pulsed with soluble antigen versus SL-encapsulated TT, mature and immature DC were cocultured in graded doses with T cells in the presence of 2 or 0.02 μg/mL soluble or encapsulated TT. Figure4 demonstrates that the capacity of immature and mature DC to process and present soluble protein to CD4+ T cells was greater than that obtained using TT-SL, particularly at low antigen concentrations and lower DC:T cell ratios. Therefore, even though only small amounts of SL-encapsulated protein reach the lysosomal pathway of DC, they can be presented to CD4+ T cells.

Presentation of graded doses of sTT or TT-SL by DC at different DC:T-cell ratios.

Mature (A, C) and immature (B, D) human DC were generated and added in a ratio of 1:10 (dark gray bars) or 1:30 (light gray bars) to 1 × 105 syngeneic T cells. Antigens (sTT or TT-SL) were directly added to the wells at 2.0 (A, B) or 0.02 (C, D) μg/mL. DC:T cell cocultures without antigen (med.) or pulsed with empty SL (SL, based on lipid concentration) were controls. T-cell proliferation was assessed by measuring the uptake of thymidine (as in Figure 3).

Presentation of graded doses of sTT or TT-SL by DC at different DC:T-cell ratios.

Mature (A, C) and immature (B, D) human DC were generated and added in a ratio of 1:10 (dark gray bars) or 1:30 (light gray bars) to 1 × 105 syngeneic T cells. Antigens (sTT or TT-SL) were directly added to the wells at 2.0 (A, B) or 0.02 (C, D) μg/mL. DC:T cell cocultures without antigen (med.) or pulsed with empty SL (SL, based on lipid concentration) were controls. T-cell proliferation was assessed by measuring the uptake of thymidine (as in Figure 3).

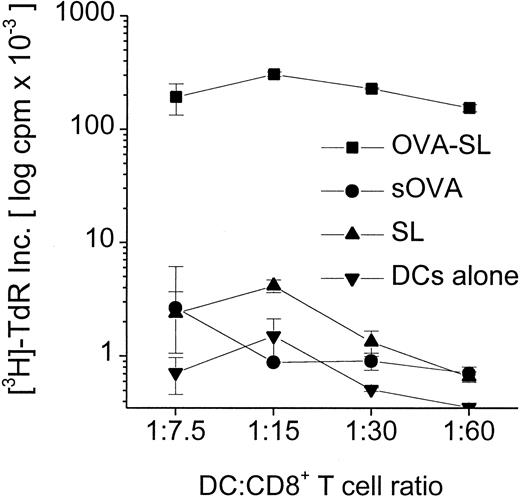

Preferential stimulation of CD8+ T-cell proliferation by SL-encapsulated antigen

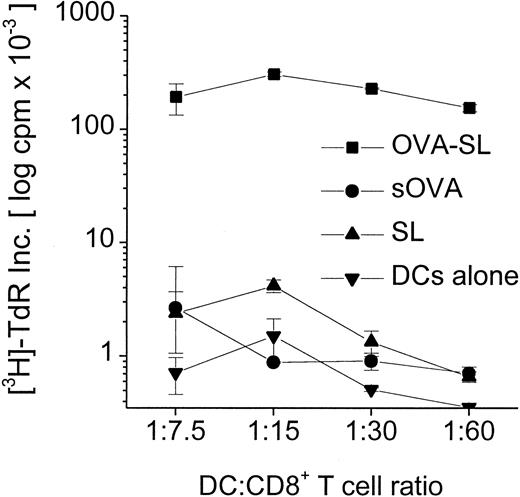

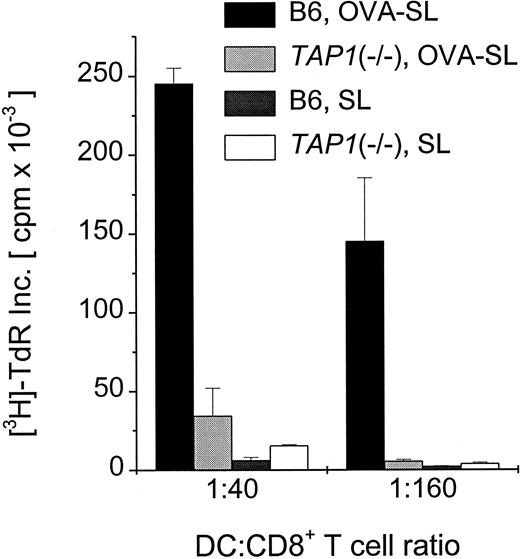

Although modest quantities of SL-encapsulated antigen reaching the lysosomes can be presented to CD4+ T cells (Figures 3, 4, Table 3), the predominance of SL in the cytoplasm of DC suggests that this might favor the activation of CD8+ T cells. We examined this in proliferation assays using CD8+T cells from OVA TCR-transgenic mice and antigen-pulsed BmDC. Mature DC were incubated with 10 μg OVA/mL as OVA-SL or as soluble OVA versus empty SL (based on lipid concentration) as a control. When these populations were incubated with 3 × 105 CD8+T cells, OVA-SL–pulsed DC stimulated T-cell proliferation to a much greater extent (up to 300-fold) than DC pulsed with comparable amounts of nonencapsulated, soluble protein (Figure5). To confirm that SL-encapsulated protein was presented on MHC class I molecules through a TAP-dependent pathway, BmDC from normal and TAP1(−/−) mice were pulsed with OVA-SL or empty SL and cultured in graded doses with 3 × 105 CD8+ T cells from OVA TCR-transgenic mice. TAP1(−/−) mice have been shown to lack antigen presentation on MHC class I.20 Figure6 demonstrates that mature BmDC fromTAP1(−/−) mice stimulated T-cell proliferation much less efficiently than wild-type DC, proving the importance of the presence of TAP molecules for delivering SL-encapsulated antigens to the MHC class I pathway.

Superior stimulation of CD8+ T cells by SL-encapsulated antigen.

Mouse BmDC were generated and transferred to new wells on day 6. On day 7, antigens (OVA-SL or sOVA) were added at 10 μg/mL, and DC pulsed with empty SL (based on lipid concentration) or cultured in medium alone were controls. On day 8, cells were harvested, washed, and added in graded doses to 3 × 105 CD8+ T cells from OT-1 mice (OVA TCR-transgenic mice). After 24 hours T-cell proliferation was assayed by thymidine incorporation, and mean log cpm × 10−3 ± SEM of triplicate cultures from a representative experiment are shown.

Superior stimulation of CD8+ T cells by SL-encapsulated antigen.

Mouse BmDC were generated and transferred to new wells on day 6. On day 7, antigens (OVA-SL or sOVA) were added at 10 μg/mL, and DC pulsed with empty SL (based on lipid concentration) or cultured in medium alone were controls. On day 8, cells were harvested, washed, and added in graded doses to 3 × 105 CD8+ T cells from OT-1 mice (OVA TCR-transgenic mice). After 24 hours T-cell proliferation was assayed by thymidine incorporation, and mean log cpm × 10−3 ± SEM of triplicate cultures from a representative experiment are shown.

Abrogation of presentation of SL-encapsulated OVA in

TAP1(−/−) mice. Mouse BmDC were generated from wild-type (B6) and TAP1(−/−) mice, and cells were transferred to new wells on day 6. OVA-SL at 10 μg/mL or empty SL were added on day 7. On day 8, cells were harvested, washed, and added in graded doses to 3 × 105 CD8+ T cells from OT-1 mice. After 24 hours, T-cell proliferation was assayed by thymidine uptake, and mean cpm × 10−3 ± SEM of triplicate cultures from a representative experiment are shown.

Abrogation of presentation of SL-encapsulated OVA in

TAP1(−/−) mice. Mouse BmDC were generated from wild-type (B6) and TAP1(−/−) mice, and cells were transferred to new wells on day 6. OVA-SL at 10 μg/mL or empty SL were added on day 7. On day 8, cells were harvested, washed, and added in graded doses to 3 × 105 CD8+ T cells from OT-1 mice. After 24 hours, T-cell proliferation was assayed by thymidine uptake, and mean cpm × 10−3 ± SEM of triplicate cultures from a representative experiment are shown.

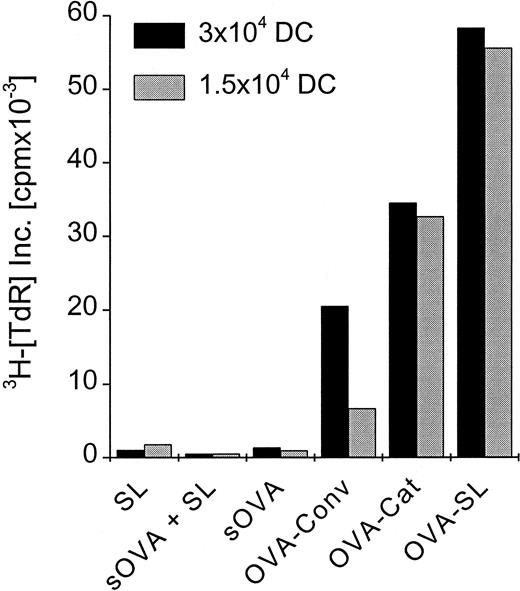

Superior induction of CD8+ T-cell responses in vivo with SL-encapsulated protein

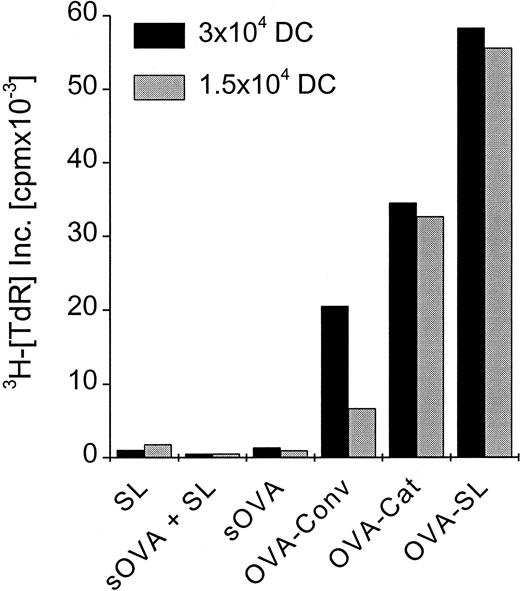

To elucidate how these in vitro findings would relate in vivo, we compared SL with soluble antigen and with other liposome formulations that have been used previously to induce CD8+ T-cell responses in naive animals.31-36Mice were immunized with OVA-SL, OVA encapsulated in positively charged liposomes, conventional liposomes, or soluble OVA. Each mouse received 2 subcutaneous doses of 8 μg OVA at 5-day intervals. On day 10, CD8+ T cells were prepared from the draining LN and cultured with OVA-SL–loaded BmDC, which induce CD8+ T-cell responses (Figures 5, 6). Although OVA in positively charged liposomes was more efficient than that in conventional liposomes (and both were better than soluble protein) at eliciting OVA-specific CD8+T-cell–mediated immune responses (Figure7), immunization with OVA-SL induced the strongest CD8+ T-cell proliferative response. Control animals, immunized with soluble OVA and empty SL, exhibited responses similar to those induced with soluble OVA alone (Figure 7). This demonstrates that the encapsulation of antigen is mandatory and excludes nonspecific adjuvant effects by SL. Hence, SL are more potent than other liposome formulations or soluble protein at directing antigen to the APCs for the induction of CD8+ T-cell responses in vivo.

Preferential induction of CD8+ T-cell responses by SL-encapsulated antigen in vivo.

Two mice were injected subcutaneously in the hindfoot pads with OVA-SL, OVA in positively charged liposomes (OVA-Cat), OVA in nonstabilized (conventional) liposomes (OVA-Conv), OVA as soluble protein (sOVA), OVA as soluble protein mixed with empty SL (based on the lipid concentration of OVA-SL) (sOVA + SL), or empty SL (SL). All animals immunized with OVA received a total of 8 μg OVA, and the amount of empty SL injected was based on the lipid concentration of OVA-SL. All animals were boosted on day 5 with the same antigen preparation received initially, and 5 days later draining LN were removed. The LN cell suspensions of the 2 animals from each group were pooled, and the CD8+ T cells were purified magnetically. Then 2.5 × 105 CD8+ T cells were incubated with 3 × 104 or 1.5 × 104 BmDC, respectively, that had been incubated with OVA-SL (10 μg/mL) for 12 hours. T-cell proliferation was measured after 4 days, and mean cpm × 10−3 from a representative experiment is shown.

Preferential induction of CD8+ T-cell responses by SL-encapsulated antigen in vivo.

Two mice were injected subcutaneously in the hindfoot pads with OVA-SL, OVA in positively charged liposomes (OVA-Cat), OVA in nonstabilized (conventional) liposomes (OVA-Conv), OVA as soluble protein (sOVA), OVA as soluble protein mixed with empty SL (based on the lipid concentration of OVA-SL) (sOVA + SL), or empty SL (SL). All animals immunized with OVA received a total of 8 μg OVA, and the amount of empty SL injected was based on the lipid concentration of OVA-SL. All animals were boosted on day 5 with the same antigen preparation received initially, and 5 days later draining LN were removed. The LN cell suspensions of the 2 animals from each group were pooled, and the CD8+ T cells were purified magnetically. Then 2.5 × 105 CD8+ T cells were incubated with 3 × 104 or 1.5 × 104 BmDC, respectively, that had been incubated with OVA-SL (10 μg/mL) for 12 hours. T-cell proliferation was measured after 4 days, and mean cpm × 10−3 from a representative experiment is shown.

Lymph node DC present SL-encapsulated antigen in vivo after subcutaneous immunization

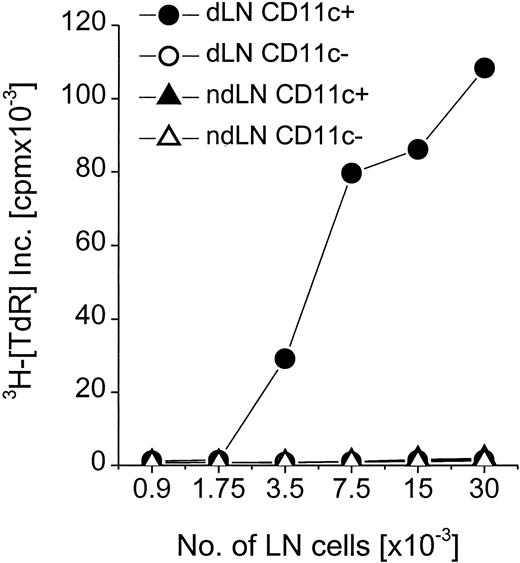

Mice were injected subcutaneously with OVA-SL, and cell suspensions were obtained after 3 days from the draining and the nondraining LN to investigate which APCs would present SL-encapsulated antigens in situ. Here, soluble protein was not included because at the applied doses (ie, 8-10 μg/mouse), it did not yield CD8+T-cell–mediated immune responses in the previous experiments (Figure7). Because DC are known to express high levels of CD11c, CD11c+, and CD11c−, cells were separated from the LN cells by magnetic sorting. CD11c+ versus CD11c− cells were used to stimulate CD8+ T cells from OT-1 mice. Only CD11c+ cells from draining LN of injected mice induced significant proliferative responses (Figure8). CD11c− cells stimulated negligible responses comparable to those induced by CD11c+or CD11c− cells isolated from the nondraining LN. Therefore, after subcutaneous injection of SL-encapsulated antigens, DC are efficiently targeted and can present the encapsulated protein to CD8+ T cells.

DC are the APCs involved in presentation of SL-encapsulated antigen in vivo.

Two mice were injected with 10 μg OVA-SL subcutaneously. Draining LN (dLN) and nondraining LN (ndLN) were removed 3 days later. Single-cell suspensions from LN were pooled, separated magnetically into CD11c+ and CD11c− fractions, and applied in graded doses to 3 × 105 CD8+ T cells from OT-1 mice. After 24 hours, T-cell proliferation was assayed by thymidine incorporation. Mean cpm × 10−3 from a representative experiment (1 of 2) are shown.

DC are the APCs involved in presentation of SL-encapsulated antigen in vivo.

Two mice were injected with 10 μg OVA-SL subcutaneously. Draining LN (dLN) and nondraining LN (ndLN) were removed 3 days later. Single-cell suspensions from LN were pooled, separated magnetically into CD11c+ and CD11c− fractions, and applied in graded doses to 3 × 105 CD8+ T cells from OT-1 mice. After 24 hours, T-cell proliferation was assayed by thymidine incorporation. Mean cpm × 10−3 from a representative experiment (1 of 2) are shown.

Discussion

Presentation of protein antigen on MHC class I molecules is known to be difficult to achieve unless the antigen is specifically targeted to the MHC class I processing machinery.37-39 As a consequence, we investigated whether the encapsulation of proteins in a new type of liposomes (SL) would lead to increased CD8+T-cell stimulation, and we studied the interaction of SL with potent antigen-presenting DC. Both immature and mature DC took up SL into intracellular sites with neutral or only mildly acidic pH. In contrast, MΦ captured more SL than DC and processed them to acidic cellular compartments, most likely lysosomes. Lysosomal location of conventional liposomes has been reported for the murine MΦ cell line J774.26 Interestingly, immature and mature DC did not differ considerably with respect to the uptake of SL, indicating that SL may enter both types of DC by similar means. This is of particular importance because the maturation of DC is generally accompanied by down-regulation of their phagocytic and antigen-processing capabilities and elevated T-cell stimulatory capacity.40 This implies that although an immature phenotype of DC is required for successful loading of DC with soluble antigen, immunization strategies based on SL-pulsed DC may be independent of the status of DC maturation. This may be critical in vitro because immature DC are known to revert to monocytes after the withdrawal of cytokines, whereas mature DC are more stable and exhibit much stronger T-cell stimulatory capacity.15 16

Confocal microscopy revealed that fluorescently labeled SL did not colocalize with any of the known endosomal, lysosomal, or MHC class II compartments. Therefore, SL were targeted to an otherwise unidentified cellular compartment with neutral pH, most likely the cytoplasm of the DC. A mildly acidic yet endocytic antigen-retention compartment in immature DC has been described.41 However, this compartment stained positive for LAMP-1 and MHC class II and is, therefore, distinct from the one in which SL localize in both immature and mature human DC (Figure 2). On the other hand, Rodriguez et al42 recently described a membrane transport pathway linking the lumen of endocytic compartments and the cytoplasm. This mechanism, which is restricted to DC and enables small proteins (3-20 kd) to escape into the cytoplasm, could more likely account for the observed differences between DC and MΦ in intracellular locations of SL.

Interestingly, our findings demonstrate that SL-encapsulated antigens ingested by DC can be readily presented to both CD4+(Figures 3, 4; Table 3) and CD8+ T cells (Figures 5-8). However, because our initial observations suggested that only small amounts of SL were retained in the lysosomal pathway, the comparable stimulation of CD4+ T cells by both sTT and TT-SL at a dose of 2 μg/mL TT by immature and mature DC was an unexpected finding (Figure 3). Of note, when the antigen concentration was decreased or lower DC:T cell ratios were used, the responses induced by TT-SL–bearing DC were considerably smaller, indicating that too little antigen had reached the MHC class II pathway to induce significant T-cell proliferation under these more limiting conditions.

In stark contrast, SL-encapsulated protein was efficiently targeted to the MHC class I processing/presenting pathway. As little as 10 μg/mL SL-encapsulated OVA induced strong stimulation of CD8+T-cell proliferation, whereas much higher concentrations (up to 10 mg/mL) of soluble protein are usually required for successful in vitro priming (unpublished observations and Watts37). The limited ability of mature murine DC to capture exogenous soluble protein antigen and present it to CD8+ T cells has been described.39 The lack of antigen presentation by DC generated from TAP1(−/−) mice confirmed that SL-encapsulated antigen gained access to the MHC class I pathway through the TAP transporter of mature DC. This is much like the TAP-dependent pathways identified for the presentation of exogenous antigen.37

Similarly, efficient TAP-dependent antigen presentation of liposome-encapsulated hen egg lysozyme by DC has been reported.43,44 However, here the liposomes were targeted to Fc receptors or MHC class I and II molecules, and immature DC were used. Recent studies by Regnault et al38 highlighted an alternative route of delivery of protein antigens into DC. Very low concentrations of immunocomplexed antigens were efficiently picked up and presented by DC to CD8+ T cells in a TAP-dependent fashion. Interestingly, the uptake of immunocomplexed antigen was very much reduced in mature DC. This most likely reflects the decreased expression or function of Fc receptors on mature DC (vs immature DC), which are required for binding and uptake of immunocomplexed antigen. This was not the case in the present study—both immature and mature DC took up and presented SL-encapsulated antigen equally well. Our experiments suggest that targeting either immature or mature DC with SL-encapsulated antigen may represent a reliable way to induce potent antigen-specific CD8+ and CD4+ T cell responses in vivo. In fact, in vivo studies described herein documented that subcutaneous injected SL-encapsulated protein targets and is efficiently presented by CD11c+ DC to activate antigen-specific CD8+ T cells (Figure 8).

The interaction of various forms of liposomes with DC has been described. Zheng et al33 recently reported that loading of human immature DC with HIV proteins by positively charged liposomes leads to an increased stimulation of HIV-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses than with cells pulsed with protein alone. Rouse et al45,46 have demonstrated the ability of murine DC loaded with protein antigen in conventional liposomes to induce primary cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses. In addition, the authors showed evidence that after intravenous injection, the liposomes primarily were taken up by MΦ, which then handed over the antigen to DC.47 To compare these different types of liposomes to SL for their potential to induce CD8+ T-cell responses in mice in vivo, we chose the subcutaneous route for its clinical relevance and injected OVA in the various liposome formulations at about 10- to 25-fold lower doses than used in previous studies. We observed that under these conditions, the greatest (up to 3-fold) CD8+T-cell stimulation was induced by SL-encapsulated antigen, whereas soluble protein at the chosen dose of OVA did not cause any CD8+ T-cell stimulation.

In conclusion, these studies demonstrate that SL represent a safe and effective means to deliver protein antigens to potent antigen-presenting DC for the induction of CD4+ and, most notably, CD8+ T-cell responses. In particular, SL-encapsulated antigen is efficiently presented to CD4+ T cells, which might be critical in helping to stimulate and maintain CD8+ T-cell responses.48 Therefore, SL are of great interest for future vaccine studies, and experiments elucidating the impact of various adjuvants and the induction of other T-cell functions such as cytokine secretion, cytotoxicity, and protection against microbial pathogens, are under way in our laboratories.

Acknowledgment

We thank Judy Adams for assistance with the figures.

Supported by the National Institutes of Health grants R21 A142670-01 (L.S.) and AI40874 (R.M.S.), the Dorothy Schiff Foundation (R.M.S., M.P.), and the Irma T. Hirschl Trust (M.P.).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Leonidas Stamatatos, Aaron Diamond AIDS Research Center, Rockefeller University, 455 First Ave, New York, NY 10016; e-mail: lstamatatos@adarc.org.