Heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) play a crucial role in growth regulation by assembling signaling complexes and presenting growth factors to their cognate receptors. Within the immune system, expression of the HSPG syndecan-1 (CD138) is characteristic of terminally differentiated B cells, ie, plasma cells, and their malignant counterpart, multiple myeloma (MM). This study explored the hypothesis that syndecan-1 might promote growth factor signaling and tumor growth in MM. For this purpose, the interaction was studied between syndecan-1 and hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), a putative paracrine and autocrine regulator of MM growth. The study demonstrates that syndecan-1 is capable of binding HGF and that this growth factor is indeed a potent stimulator of MM survival and proliferation. Importantly, the interaction of HGF with heparan sulfate moieties on syndecan-1 strongly promotes HGF-mediated signaling, resulting in enhanced activation of Met, the receptor tyrosine kinase for HGF. Moreover, HGF binding to syndecan-1 promotes activation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase B and RAS/mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways, signaling routes that have been implicated in the regulation of cell survival and proliferation, respectively. These results identify syndecan-1 as a functional coreceptor for HGF that promotes HGF/Met signaling in MM cells, thus suggesting a novel function for syndecan-1 in MM tumorigenesis.

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a clonal B-cell neoplasm in which the malignant tumor cells are localized to the bone marrow. Within the bone marrow, the neoplastic cells lie in close proximity to stromal cells, which provide signals required for their progression through different disease stages.1 These signals include a variety of cytokines and growth factors, stimulating tumor growth and survival. Several of these soluble mediators have the potential to bind to heparin, a glycosaminoglycan (GAG) structurally related to heparan sulfate (HS), suggesting that heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs), expressed on the cell surface of MM cells or in the extracellular matrix of the bone marrow, might modulate their function.

HSPGs are proteins that are covalently linked to sulfated GAG chains composed of alternating glucuronic acid andn-acetylglucosamine units.2,3 These molecules, which are widespread throughout mammalian tissues as extracellular matrix components and membrane-bound molecules, have been implicated in several important biologic processes, including cell adhesion and migration, tissue morphogenesis, angiogenesis, and regulation of blood coagulation. In these processes, HSPGs are believed to function as scaffold structures, designed to accommodate proteins through noncovalent binding to their GAG chains. Their ligand-binding sites reside within discrete sulfated domains formed by complex, cell-specific, chemical modifications of the HS disaccharide repeat.2,4 Binding of proteins, including growth factors and cytokines, to HS may serve a variety of functions, ranging from immobilization and concentration to distinct modulation of biologic function. This functional importance is illustrated by fibroblast growth factor 2 in which binding to its signal-transducing receptors and consequent biologic effects are critically dependent on its interaction with cell surface HSPGs.5,6 Recently, genetic studies have provided compelling evidence for an in vivo role of cell surface HSPGs in growth control and morphogenesis inDrosophila, mice, and humans.7

Syndecan-1 is a member of a family of 4 mammalian HSPGs expressed in a cell- and tissue-specific pattern.3 It is highly expressed on many epithelia where it contributes to cell adhesion and epithelial morphogenesis.3 Moreover, by stimulating the activity of the oncoprotein Wnt-1, it can promote the development of mouse mammary gland tumors.8 Within the immune system, syndecan-1 is expressed on terminally differentiated B cells, ie, plasma cells, and on their malignant counterpart, MM.9,10 Furthermore, it is present on a subset of AIDS-related non-Hodgkin lymphomas, including primary effusion lymphoma (PEL).11 The biologic function of syndecan-1 in normal and neoplastic B cells is as yet incompletely understood. Syndecan-1 in lymphoblastoid B cells or MM cells was reported to promote cell adhesion and spreading on matrix molecules like type I collagen and to mediate homotypic cell aggregation.12,13 Recently, syndecan-1 has been shown to colocalize with growth factors in the uropods of MM cells,14 but so far there is no direct evidence that it regulates their biologic activity. Here, we have explored the role of syndecan-1 in growth factor signaling. We show that syndecan-1 on MM cells binds hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor (HGF), a multifunctional cytokine that regulates integrin-dependent adhesion and migration of B cells and is a putative regulator of tumor growth in both MM and PEL.15-17 Importantly, syndecan-1 strongly promotes HGF-induced signaling through Met, the receptor tyrosine kinase for HGF, resulting in enhanced activation of signaling pathways involved in the control of cell proliferation and survival.

Materials and methods

Antibodies

Mouse monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) used were anti–syndecan-1 (CD138, clone B-B4, immunoglobulin G1 [IgG1]; Coulter Immunotech, Marseille, France); anti–syndecan-2, 10H4 (IgG1); anti–syndecan-4, 8G3 (IgG1); anti–glypican-1, S1 (IgG1) (all kindly provided by Dr G. David, Center for Human Genetics, University of Leuven, Leuven, Belgium); anti-HGF, 24 612.111 (IgG1; R&D Systems, Abington, United Kingdom); anti–heparan sulfate, 10E4 (IgM; Seikagaku, Tokyo, Japan), anti–desaturated uronate from heparitinase-treated heparan sulfate (ΔHS stub), 3G10 (IgG2b; Seikagaku); and antiphosphotyrosine, PY-20 (IgG2b; Affiniti, Nottingham, United Kingdom). Polyclonal antibodies used were rabbit anti-Met, C-12 (IgG; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA); rabbit antiphospho protein kinase B (PKB)/Akt (Ser 473); rabbit antiphospho p44/42 mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase (Thr 202/Tyr 204) (both New England Biolabs, Hitcin, United Kingdom); R-phycoerythrin–conjugated goat antimouse (Southern Biotechnology, Birmingham, AL); horseradish peroxidase (HRP)–conjugated rabbit antimouse; (DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark); and HRP-conjugated goat antirabbit (DAKO).

Cell lines, primary myeloma cells, and transfectants

MM cell line XG-1 was described elsewhere.18 LME-1 was isolated from a patient with MM at the Department of Hematology, Academic Medical Center, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. MM cell lines were cultured in Iscoves medium (Gibco BRL/Life Technologies, Breda, The Netherlands) containing 10% fetal calf serum (Integro, Zaandam, The Netherlands), 100 IU/mL penicillin, and 100 IU/mL streptomycin (Life Technologies), 20 μg/mL human recombinant transferrin (Sigma, Bornem, Belgium), 50 μM β-mercapto ethanol, and 500 pg/mL interleukin 6 (IL-6) (R&D Systems). Primary myeloma (PM) cells were obtained from the pleural effusion of a patient with MM. Mononuclear cells were harvested by standard Ficoll-Paque density gradient centrifugation (Amersham Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) and kept on a stromal cell feeder-layer in Iscoves medium (Gibco BRL/Life Technologies) containing 10% fetal calf serum (Integro), 100 IU/mL penicillin, and 100 IU/mL streptomycin (Life Technologies). For signaling experiments, primary tumor cells (containing more than 97% plasma cells) were serum starved for 24 hours in the presence of 2% fetal calf serum, after which the cells were kept under serum-free conditions for 3 hours. The Burkitt lymphoma cell line Namalwa was purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Rockville, MD). The Met-transfected Namalwa (NamMET) was described previously.19 Syndecan-1– and glypican-1–transfected Namalwa cells (NamSYN and NamGLYP) were obtained by electroporation by using the eukaryotic expression vector pCDNA3 containing the full-length human syndecan-1 complementary DNA or glypican-1 complementary DNA (kindly provided by Dr G. David). Transfectants were selected in medium containing 1.6 mg/mL neomycin (Sigma). Syndecan-1– and glypican-1–positive cells were subcloned by using a FACStar flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA). Namalwa cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 (Life Technologies) supplemented with 10% Fetal Clone I serum (HyClone Laboratories, Logan, UT), 10% fetal calf serum (Integro), 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 IU/mL penicillin, and 100 IU/mL streptomycin (all Life Technologies).

Enzyme treatments

For enzymatic cleavage of HS, cells were treated with either 10 mU/mL heparitinase (Flavobacterium heparinum, EC 4.2.2.8; ICN Biomedicals, Aurora, OH) or, as control, 50 mU/mL chondroitinase ABC (Proteus vulgaris, EC 4.2.2.4; Boehringer Mannheim, Almere, The Netherlands). The cleavage of HS by heparitinase was determined by the loss of cell surface–expressed HS (mAb 10E4) and the simultaneous gain of HS-stub expression (mAb 3G10).

Flow-activated cell sorter analysis

Flow-activated cell sorter (FACS) analyses using a single staining technique were described previously.20 For binding of recombinant human HGF (R&D Systems) or mutant HP1,21 cells were incubated with saturating concentrations for 1 hour at 4°C before the antibody incubations. Washing with FACS buffer followed this step.

Immunoprecipitation and Western blot analysis

Immunoprecipitation and Western blotting were performed as described.20 For analysis of phosphorylation of PKB/Akt and the MAP kinases extracellular signal-related kinase (Erk)1 and Erk2, after the indicated treatments, 3 × 105 cells were directly lysed in sample buffer, separated by 10% sodium dodecylsulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and blotted. Equal loading was confirmed by Ponceau S staining of the blot. The part of the blot above 130 kd was stained with anti-Met (C12), the middle part (50 to 130 kd) was stained with antiphospho PKB/Akt, and the bottom part (below 50 kd) was stained with antiphospho MAP kinase antiserum (all from New England Biolabs). Primary antibodies were detected by HRP-conjugated goat antirabbit or HRP-conjugated rabbit antimouse.

Cell proliferation assay

Cells were plated in 96-well flat-bottom tissue culture plates (Costar, Cambridge, MA) at a density of approximately 100 000 cells/mL (200 μL per well) in the absence of IL-6 and serum, in supplemented Iscoves medium as described above. HGF was added, and cells were cultured for 7 days. Cell numbers and viability were determined by adding propidium iodide and analysis on a FACScalibur (Becton Dickinson). For proliferation, the cultures were pulsed with 0.0185 MBq (0.5 μCi) (methyl-3H) thymidine (321.9 × 1010 Bq/mmol [87 Ci/mmol]; Amersham Life Science, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom) during the last 4 hours. Results are expressed as counts per minute (cpm). Error bars represent the SD values of triplicate measurements.

Results

Expression of HS moieties and proteoglycan core proteins on MM cells

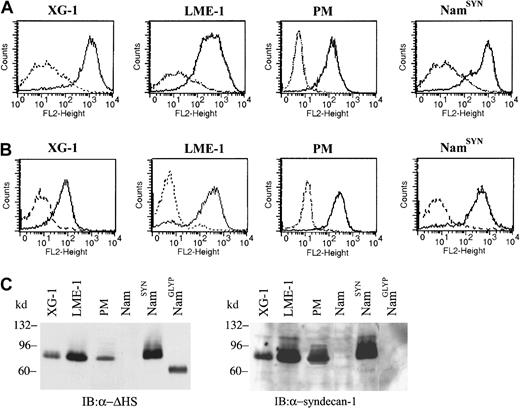

Expression of the HSPG syndecan-1 as well as Met, the receptor tyrosine kinase for HGF, is common on MM cells.10,22 This expression suggests that HGF might not only interact with Met but also with syndecan-1, resulting in a ternary interaction between Met, HGF, and syndecan-1 at the MM cell surface. This ménage a trois might promote tumorigenesis. To explore this hypothesis, we used 2 MM cell lines, ie, XG-118 and LME-1, as well as primary tumor cells from a patient with MM patient (PM). FACS analysis demonstrated that these cells express high levels of both HS and syndecan-1 (Figure1) but lack expression of other proteoglycan core proteins, including other syndecans, glypican-1, and CD44v3 (data not shown). In accordance with these FACS data, a single HSPG of approximately 90 kd was detected by immunoblotting in the cell lysates of XG-1, LME-1, and PM cells (Figure 1C, left panel). A HSPG of similar size was also present in the lysates of syndecan-1–transfected Namalwa Burkitt lymphoma cells (NamSYN), but not in that of untransfected (Nam) or glypican-1 (NamGLYP)–transfected cells (Figure 1C, left panel). Stripping and restaining the blot with an antisyndecan-1 mAb confirmed that this 90-kd HSPG represents syndecan-1 (Figure 1C, right panel), indicating that syndecan-1 is the major, and presumably only, HSPG expressed by XG-1, LME-1, and PM cells studied.

Expression of HSPGs and syndecan-1 on MM cells.

(A) Expression of HS on the MM cells. Cell lines XG-1 and LME-1 and primary myeloma (PM) cells were stained with a mouse anti-HS antibody (10E4; solid line), or isotype control (dashed line), followed by R-phycoerythrin–conjugated goat antimouse and analyzed by FACS. (B) Expression of the HSPG core protein syndecan-1 by XG-1 and LME-1 cell lines and by PM cells. Cells were stained with a mouse anti–syndecan-1 antibody (B-B4; solid line) or isotype control (dashed line), and expression was analyzed by FACS. The syndecan-1 stably transfected cell line Namalwa (NamSYN) was used as a positive control. (C) XG-1, LME-1, and PM cells express a single HSPG of approximately 90 kd that represents syndecan-1. (Left panel) HSPG expression was detected with mAb 3G10 against desaturated uronate (ΔHS stubs) of HS. To allow detection of the ΔHS stubs, the cells were treated with heparitinase before immunoblotting. Namalwa cell lines, either wild type (Nam) or stably transfected with syndecan-1 (NamSYN) or glypican-1 (NamGLYP), were used as negative and positive controls for HSPG and syndecan-1 expression. (Right panel) After stripping, the same blot was restained with mAb B-B4 against syndecan-1.

Expression of HSPGs and syndecan-1 on MM cells.

(A) Expression of HS on the MM cells. Cell lines XG-1 and LME-1 and primary myeloma (PM) cells were stained with a mouse anti-HS antibody (10E4; solid line), or isotype control (dashed line), followed by R-phycoerythrin–conjugated goat antimouse and analyzed by FACS. (B) Expression of the HSPG core protein syndecan-1 by XG-1 and LME-1 cell lines and by PM cells. Cells were stained with a mouse anti–syndecan-1 antibody (B-B4; solid line) or isotype control (dashed line), and expression was analyzed by FACS. The syndecan-1 stably transfected cell line Namalwa (NamSYN) was used as a positive control. (C) XG-1, LME-1, and PM cells express a single HSPG of approximately 90 kd that represents syndecan-1. (Left panel) HSPG expression was detected with mAb 3G10 against desaturated uronate (ΔHS stubs) of HS. To allow detection of the ΔHS stubs, the cells were treated with heparitinase before immunoblotting. Namalwa cell lines, either wild type (Nam) or stably transfected with syndecan-1 (NamSYN) or glypican-1 (NamGLYP), were used as negative and positive controls for HSPG and syndecan-1 expression. (Right panel) After stripping, the same blot was restained with mAb B-B4 against syndecan-1.

Stimulation of MM cells with HGF leads to activation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/PKB and RAS/MAP kinase pathways as well as cell proliferation

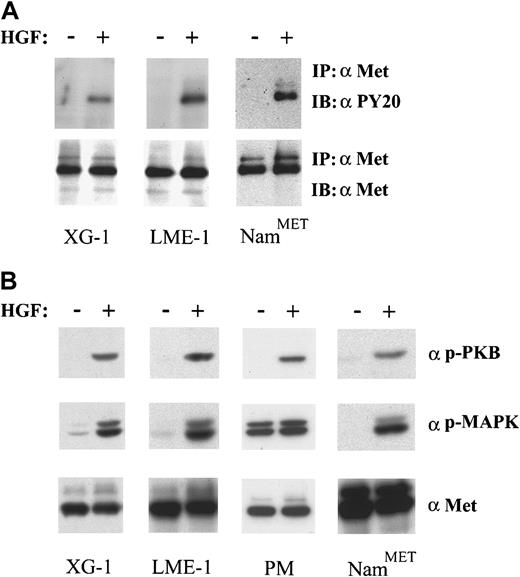

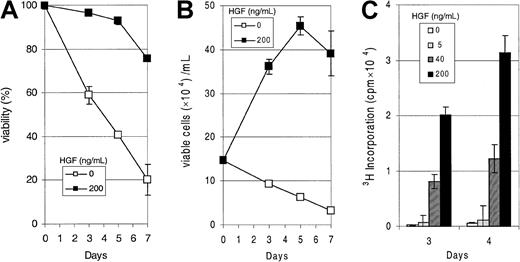

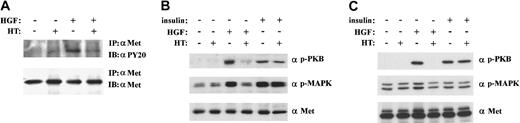

In addition to expressing syndecan-1, the XG-1, LME-1, and PM cells express Met and possess a functional Met signaling pathway (Figure 2). Stimulation of XG-1 and LME-1 with HGF resulted in a rapid tyrosine phosphorylation of Met (Figure2A) as well as phosphorylation of PKB/Akt and the MAP kinases Erk1 and Erk2 (Figure 2B). In the PM cells we also observed a strong HGF-induced serine phosphorylation of PKB/Akt, whereas the phosphorylation of MAP kinases Erk1 and Erk2 increased approximately 2-fold (Figure 2B). Hence, signaling by Met in these MM cells leads to activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3-K)/PKB as well as RAS/MAP kinase pathways, signaling routes that have been implicated in the regulation of cell survival and proliferation, respectively.23-25 Interestingly, we observed that XG-1 cells deprived of IL-6, a cytokine required for their propagation in vitro,18 survive and respond to HGF stimulation with a strong dose-dependent DNA synthesis (Figure3).

HGF/Met signaling in MM.

(A) HGF stimulation induces Met activation in XG-1 and LME-1. Cells were incubated for 2 minutes in the absence or presence of HGF. Met activation was assessed by immunoprecipitation and subsequent immunoblotting with antiphosphotyrosine antibodies. (B) HGF stimulation induces activation of both PKB/Akt and MAP kinases. Activation of PKB/Akt and MAP kinases was determined in total cell lysates of XG-1, LME-1, and MC cells and immunoblotted with antiphospho PKB/Akt (top) and antiphospho Erk1 and Erk2 (α p-MAPK) (middle), respectively. The Met-expressing Burkitt cell line NamMET was used as a positive control. Stainings with antihuman Met represent loading controls (A,B bottom panels).

HGF/Met signaling in MM.

(A) HGF stimulation induces Met activation in XG-1 and LME-1. Cells were incubated for 2 minutes in the absence or presence of HGF. Met activation was assessed by immunoprecipitation and subsequent immunoblotting with antiphosphotyrosine antibodies. (B) HGF stimulation induces activation of both PKB/Akt and MAP kinases. Activation of PKB/Akt and MAP kinases was determined in total cell lysates of XG-1, LME-1, and MC cells and immunoblotted with antiphospho PKB/Akt (top) and antiphospho Erk1 and Erk2 (α p-MAPK) (middle), respectively. The Met-expressing Burkitt cell line NamMET was used as a positive control. Stainings with antihuman Met represent loading controls (A,B bottom panels).

HGF-induced proliferation of MM cells.

(A) HGF mediates increased survival in XG-1. Cells were grown in the absence of IL-6 and serum, and HGF was added at a concentration of 200 ng/mL. Viability was measured by FACS analysis on days 0, 3, 5, and 7, using propidium iodide incorporation. On day 0, relative viability was set at 100%. (B) HGF is a potent growth factor for XG-1. Culture conditions were as in (A), HGF was added in the concentration shown, and the number of viable cells was quantified by using propidium iodide incorporation and FACS analysis at days 0, 3, 5, and 7. (C) HGF induces proliferation in XG-1. Cells were cultured as in (A), and HGF was added in the concentrations shown. 3H thymidine incorporation was measured on days 3 and 4. Error bars represent the SD of a triplicate measurement.

HGF-induced proliferation of MM cells.

(A) HGF mediates increased survival in XG-1. Cells were grown in the absence of IL-6 and serum, and HGF was added at a concentration of 200 ng/mL. Viability was measured by FACS analysis on days 0, 3, 5, and 7, using propidium iodide incorporation. On day 0, relative viability was set at 100%. (B) HGF is a potent growth factor for XG-1. Culture conditions were as in (A), HGF was added in the concentration shown, and the number of viable cells was quantified by using propidium iodide incorporation and FACS analysis at days 0, 3, 5, and 7. (C) HGF induces proliferation in XG-1. Cells were cultured as in (A), and HGF was added in the concentrations shown. 3H thymidine incorporation was measured on days 3 and 4. Error bars represent the SD of a triplicate measurement.

Syndecan-1 binds HGF by its HS moieties and promotes signaling through Met

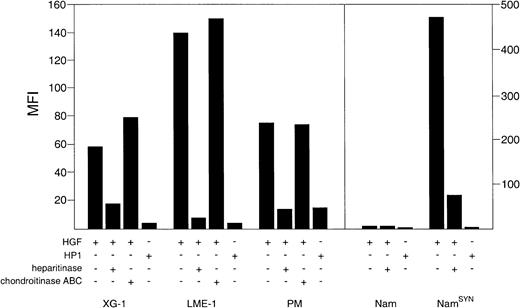

We subsequently investigated the ability of syndecan-1 to interact with HGF. The MM cell lines XG-1 and LME-1, the PM cells, as well as syndecan-1–transfected Namalwa (NamSYN) cells were found to bind high levels of HGF (Figure 4), whereas wild-type Namalwa cells bound virtually no HGF. Importantly, this HGF binding was largely dependent on HS moieties decorating syndecan-1 and heparitinase but not chondroitinase ABC; pretreatment of the cells resulted in a strongly reduced HGF binding (Figure 4). Moreover, HP-1, a mutant form of HGF with a more than 50-fold decreased affinity for HS,21 showed only a weak binding to the MM cells and NamSYN (Figure 4).

Syndecan-1 binds HGF by its heparan sulfate side chains.

MM cell lines XG-1 and LME-1 and PM cells, Nam and NamSYN, were analyzed by FACS for their capacity to bind HGF or the HGF mutant HP1. To determine the involvement of HS in HGF binding, cells were treated with either heparitinase or chondroitinase ABC before incubation with HGF. Binding of HGF or HP1 is shown as the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of cells incubated with HGF or HP1, washed, and stained with a HGF-specific mAb, minus the MFI of identical cells not incubated with HGF.

Syndecan-1 binds HGF by its heparan sulfate side chains.

MM cell lines XG-1 and LME-1 and PM cells, Nam and NamSYN, were analyzed by FACS for their capacity to bind HGF or the HGF mutant HP1. To determine the involvement of HS in HGF binding, cells were treated with either heparitinase or chondroitinase ABC before incubation with HGF. Binding of HGF or HP1 is shown as the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of cells incubated with HGF or HP1, washed, and stained with a HGF-specific mAb, minus the MFI of identical cells not incubated with HGF.

To explore the functional consequence of the HGF and syndecan-1 interaction, we studied HGF/Met signaling in XG-1 and PM cells from which the HS moieties had been removed by heparitinase treatment. As shown in Figure 5A, removal of HS from XG-1 resulted in a strongly reduced tyrosine phosphorylation of Met in response to HGF. Apart from the autophosphorylation of Met, the HGF-induced activation of downstream effector molecules of the HGF/Met signaling pathway, indicative for the antiapoptotic and proliferative effects of HGF, ie, the kinase PKB/Akt, as well as the MAP kinases Erk1 and Erk2, was greatly inhibited by the removal of HS from both XG-1 (Figure 5B). In PM cells, the HGF-induced activation of the kinase PKB/Akt was also completely inhibited as a result of the removal of HS (Figure 5C). Because of the high baseline HGF-independent activity of the MAP kinases Erk1 and Erk2 in PM cells, removal of the HS moieties hardly reduced the phosphorylation of the MAP kinases Erk1 and Erk2 (Figure 5C). Importantly, the reduction in PKB/Akt and/or MAP kinase activation in XG-1 and PM cells did not result from nonspecific effects of the heparitinase treatment, as their activation by insulin, which does not bind to HS, was unaffected (Figure 5B and C).

Syndecan-1 promotes HGF-induced activation of Met, PKB/Akt, and MAP kinase.

To assess the contribution of syndecan-1 to HGF-induced signaling, MM cell line XG-1 and PM cells were treated with heparitinase (HT) before stimulation with HGF. (A) Activation of Met. Met activation in XG-1 was assessed by immunoprecipitation and subsequent immunoblotting with antiphosphotyrosine antibodies. (B) Activation of PKB/Akt and MAP kinase. Activation of PKB/Akt and the MAP kinases Erk1 and Erk2 was determined in total cell lysates of XG-1 immunoblotted with antiphospho PKB/Akt (top) and antiphospho Erk1 and Erk2 (α p-MAPK) (middle), respectively. (C) Activation of PKB/Akt and MAP kinase. Activation of PKB/Akt and the MAP kinases Erk1 and Erk2 was determined in total cell lysates of PM cells, immunoblotted with antiphospho PKB/Akt (top) and antiphospho Erk1 and Erk2 (α p-MAPK) (middle), respectively. Staining with anti-Met was used to verify equal loading (A,B,C bottom panels). Activation of PKB/Akt and MAP kinase by insulin, which does not bind to HS, was not affected by HT treatment (B and C).

Syndecan-1 promotes HGF-induced activation of Met, PKB/Akt, and MAP kinase.

To assess the contribution of syndecan-1 to HGF-induced signaling, MM cell line XG-1 and PM cells were treated with heparitinase (HT) before stimulation with HGF. (A) Activation of Met. Met activation in XG-1 was assessed by immunoprecipitation and subsequent immunoblotting with antiphosphotyrosine antibodies. (B) Activation of PKB/Akt and MAP kinase. Activation of PKB/Akt and the MAP kinases Erk1 and Erk2 was determined in total cell lysates of XG-1 immunoblotted with antiphospho PKB/Akt (top) and antiphospho Erk1 and Erk2 (α p-MAPK) (middle), respectively. (C) Activation of PKB/Akt and MAP kinase. Activation of PKB/Akt and the MAP kinases Erk1 and Erk2 was determined in total cell lysates of PM cells, immunoblotted with antiphospho PKB/Akt (top) and antiphospho Erk1 and Erk2 (α p-MAPK) (middle), respectively. Staining with anti-Met was used to verify equal loading (A,B,C bottom panels). Activation of PKB/Akt and MAP kinase by insulin, which does not bind to HS, was not affected by HT treatment (B and C).

Discussion

Recently, biochemical, cell biologic, and genetic studies have converged to reveal that integral membrane HSPGs are critical regulators of growth and differentiation of epithelial and connective tissues. By immobilizing and oligomerizing cytokines and by presenting them to their high affinity receptors, HSPGs create niches in the microenvironment and regulate cytokine responses. Because a vast number of cytokines and growth factors involved in the growth and differentiation of normal and neoplastic lymphocytes contain potential HS binding sites, HSPGs presumably also play important roles in the immune response and in the development and progression of lymphoid tumors. However, the expression and function of HSPGs on the cell surface of normal and neoplastic lymphocytes has thus far remained largely unexplored. In the present study, we investigated the expression and function of HSPGs on MM cell lines and primary MM tumor cells. We demonstrate that the HSPG syndecan-1 on MM cells is capable of binding HGF. This interaction promotes signaling through Met, the receptor tyrosine kinase for HGF, and regulates the activity of signaling pathways that control cell proliferation and survival.

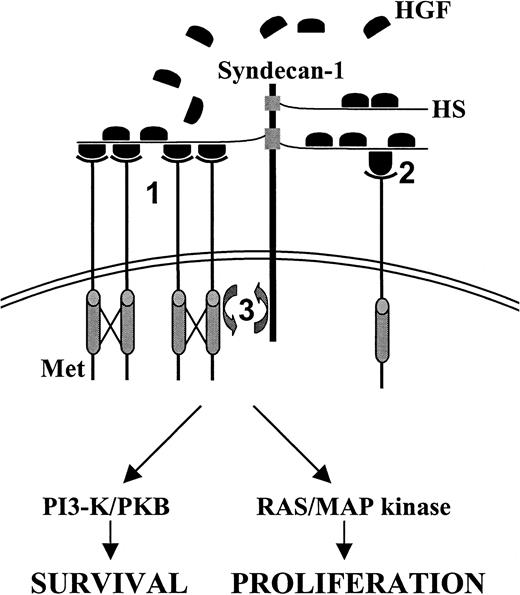

Our findings present the first direct evidence that syndecan-1 regulates growth factor signaling in MM. Cell surface–expressed syndecan-1 presumably acts by increasing the effective concentration of HGF on the plasma membrane, an effect that may be modulated by soluble syndecan-1 shed from the MM cell surface,26 whereas the binding of several HGF molecules to syndecan-1 may promote dimerization and oligomerization of Met, leading to enhanced receptor activation (Figure 6). Alternatively, by inducing a conformational change, syndecan-1 might influence the affinity of HGF for Met, as has been demonstrated for HSPG binding of the NK1 splice variant of HGF.27

Model for the

ménage a trois between syndecan-1, Met, and HGF in MM. Syndecan-1 may promote Met signaling by several mechanisms. First, binding of autocrine or paracrine (bone marrow stroma) produced HGF by the HS side chains of syndecan-1 may result in dimerization or oligomerization of HGF, thereby promoting Met cross-linking and tyrosine kinase activity (1). Second, HGF and syndecan-1 interaction might induce a conformational change of HGF, leading to enhanced signal transduction (2). Third, HGF may mediate colocalization of syndecan-1 and Met. Ternary complex formation between HGF, Met, and syndecan-1 may bring relevant intracellular signaling molecules together, which may facilitate their activation by Met (3). See “Discussion” for further detail.

Model for the

ménage a trois between syndecan-1, Met, and HGF in MM. Syndecan-1 may promote Met signaling by several mechanisms. First, binding of autocrine or paracrine (bone marrow stroma) produced HGF by the HS side chains of syndecan-1 may result in dimerization or oligomerization of HGF, thereby promoting Met cross-linking and tyrosine kinase activity (1). Second, HGF and syndecan-1 interaction might induce a conformational change of HGF, leading to enhanced signal transduction (2). Third, HGF may mediate colocalization of syndecan-1 and Met. Ternary complex formation between HGF, Met, and syndecan-1 may bring relevant intracellular signaling molecules together, which may facilitate their activation by Met (3). See “Discussion” for further detail.

Furthermore, the polarized distribution of syndecan-1, as observed on myeloma cells,14 may impose a constraint on the spatial distribution of HGF, resulting in the clustering of activated Met and Met-associated signaling molecules (Figure 6). In this scenario, the potentiation of Met signaling may be partially explained by HGF-mediated colocalization of syndecan-1 and Met, which may bring relevant intracellular signaling molecules in the proximity of each other. Indeed, several syndecan family members have been reported to associate with signaling molecules by means of their cytoplasmic tails. Syndecan-4, for example, can interact with (and activate) protein kinase C-α, PIP2, and Syndesmos, which are all implicated in syndecan-4–controlled integrin-mediated focal adhesion formation and cell spreading.28 Furthermore, all syndecans contain a motive through which they can interact with the guanylate kinase CASK/LIN-2,28 affecting its nuclear translocation and transcription regulatory activity.29

Interestingly, our data establish a functional link between syndecan-1 and the HGF/Met pathway, a signaling route that induces complex biologic responses in target cells, including motility, growth, and morphogenesis. In mice, met or hgf deficiency results in embryonic death with severe defects in the development of the placenta, liver, and limb muscles, whereas uncontrolled activation of Met, in both mice and humans, has been implicated in tumor growth, invasion, and metastasis (reviewed in van der Voort et al15). Of note, studies in hereditary papillary renal carcinoma established a causative role for Met mutations in human cancer.30 These mutations result in enhanced kinase activity on stimulation with HGF and were shown to mediate transformation, invasive growth, and protection from apoptosis.31 The HGF/Met pathway has also been implicated in B-cell development and neoplasia.15,16,19 During normal B-cell differentiation, Met is expressed at the GC and plasma cell stage, whereas HGF is produced by follicular dendritic cells19 and by bone marrow stromal cells.32HGF stimulation of B lymphocytes leads to enhanced integrin activity, promoting cell adhesion to VCAM-1, a major integrin ligand on follicular dendritic cells as well as B-cell migration.19,33 Interestingly, in GC cells, presentation of HGF by the HSPG CD44v3 promotes Met signaling.15 In B-cell malignancies, the HGF/Met pathway may promote tumorigenesis through both autocrine and paracrine mechanisms. In PEL,17as well as MM, Met and HGF are often coexpressed, suggesting autocrine stimulation.16 Because bone marrow stromal cells have been reported to produce HGF,32 paracrine stimulation of MM cells may also take place within the bone marrow microenvironment. Consistent with a role for the HGF/Met in MM progression, high serum levels of HGF were reported to be associated with unfavorable prognosis in patients with MM.34

The biologic processes controlled by the HGF/Met pathway in MM cells are as yet incompletely defined. Our current study demonstrates that HGF can promote tumor growth (Figure 3), a function presumably involving transcription regulatory signals delivered through the activated RAS/MAP kinase pathway (Figure 2B). In addition, HGF stimulation might also affect tumor dissemination and/or tumor cell survival. A role in MM dissemination is suggested by the fact that HGF has been shown to regulate integrin activity on GC B cells and promotes adhesion and migration of Burkitt lymphoma cell lines.19,33,35 Key regulatory molecules implicated in inside-out signaling to integrins are PI3-K and different RAS-like guanosine triphosphatases, the activity of which can be controlled by HGF/Met.36 In MM cell survival, the HGF/Met pathway may also play a critical part. Studies in several cell types, including liver cell precursors and carcinoma cells, have indicated that the HGF/Met pathway can generate potent survival signals.37Antiapoptotic signals in MM might be transduced through the PI3-K/PKB pathway, which was activated by HGF in our MM cell lines and primary tumor cells (Figure 2B). PKB/Akt is able to phosphorylate BAD, a BCL-2 antagonist expressed in B cells, and may thereby suppress the proapoptotic effects of BAD.23

In conclusion, our present findings demonstrate that syndecan-1 strongly promotes HGF/Met signaling, resulting in enhanced activation of signaling pathways involved in the control of cell proliferation and survival. Clearly, this regulatory role of syndecan-1 may not be limited to the HGF/Met pathway but may extend to other pathways driven by heparin-binding growth factors like heparin-binding epidermal growth factor and fibroblast growth factor 2, outlining an important role for syndecan-1 in the pathogenesis of MM.

We thank S. de Jong, J. Dobber, E. A. Beuling, and T. A. M. Wormhoudt for excellent technical assistance.

Supported by grants from the Dutch Cancer Society and the Association for International Cancer Research (AICR).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Steven T. Pals, Department of Pathology, Academic Medical Center, University of Amsterdam, PO Box 22700, 1100 DE Amsterdam, The Netherlands; e-mail: s.t.pals@amc.uva.nl.