Abstract

Mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal to regulated kinase (MEK) kinase 1 (MEKK1) is a c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) activating kinase known to be implicated in proinflammatory responses and cell motility. Using mice deficient for MEKK1 kinase activity (Mekk1ΔKD) we show a role for MEKK1 in definitive mouse erythropoiesis. Although Mekk1ΔKD mice are alive and fertile on a 129 × C57/BL6 background, the frequency of Mekk1ΔKD embryos that develop past embryonic day (E) 14.5 is dramatically reduced when backcrossed into the C57/BL6 background. At E13.5, Mekk1ΔKD embryos have normal morphology but are anemic due to failure of definitive erythropoiesis. When Mekk1ΔKD fetal liver cells were transferred to lethally irradiated wild-type hosts, mature red blood cells were generated from the mutant cells, suggesting that MEKK1 functions in a non–cell-autonomous manner. Based on immunohistochemical and hemoglobin chain transcription analysis, we propose that the failure of definitive erythropoiesis is due to a deficiency in enucleation activity caused by insufficient macrophage-mediated nuclear DNA destruction.

Introduction

Production of red blood cells (erythropoiesis) is an essential step in vertebrate embryogenesis making it possible to advance from diffusion-restricted to circulation-assisted growth. In the mouse embryo, primitive erythropoiesis is initiated in the yolk sac around embryonic day (E) 7.5. Yolk sac–derived erythrocytes are large, nucleated cells that do not complete the final stages of normal adult erythropoiesis.1 Around E9.5 erythropoiesis is initiated in the fetal liver2,3 ; concurrently, the yolk sac gradually becomes less important for erythropoiesis and around E14.5 90% of the erythrocytes present in circulation are of fetal liver origin.4,5 The generation of mature erythrocytes involves the commitment of pluripotent hematopoietic stem cells progressing through erythroid blast-forming unit (BFU-E) and erythroid colony-forming unit (CFU-E) progenitor-cell stages, proerythroblast and several erythroblast stages, ultimately terminating into mature enucleated erythrocytes. Moreover, the development of fetal liver erythropoiesis is considered to proceed through 2 distinct phases: the first phase (E11-13), in which erythroid maturation proceeds in the absence of macrophages, and the second phase, involving the establishment of erythroblastic islands consisting of a central macrophage surrounded by erythroblasts.6 The central macrophages of the erythroblastic islands have been suggested to induce several key biologic processes in the erythroid precursors including proliferation and differentiation, prevention of apoptosis, and promotion of erythroblast enucleation.7 Furthermore, recent studies suggest that failure of definitive erythropoiesis in deoxyribonuclease (DNase) II–deficient mice is due to impaired erythroblast enucleation, caused by inability of the central macrophages to digest nuclear DNA expelled from erythroblasts.8,9

The conserved mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) family members c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and p38 have been implicated in stress and proinflammatory signal transduction and recently in erythropoiesis.10-12 A number of cytokines are involved in the erythropoiesis, including erythropoietin and stem-cell factor (SCF),13,14 and it has been shown that erythropoietin induces sustained JNK activity and supports proliferation of erythropoietin-dependent cell lines12 ; additionally, p38 seems to be required for posttranscriptional regulation of erythropoietin expression.10 Homozygous deletion of either JNK1 or JNK2 in mice has no apparent effect on hematopoiesis,15,16 which might be explained by redundancy between the JNK isoforms. In contrast, the Jnk1–/–Jnk2–/– embryos die early in embryonic development (E11.5-12.5) due to dysregulation of apoptosis in brain development, making the contribution of the JNK kinases in definitive erythropoiesis in vivo difficult to study further. We have investigated the role of the JNK-activating kinase mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal to regulated kinase (MEK) kinase 1 (MEKK1) in development. Mice deficient in MEKK1 kinase activity (Mekk1ΔKD mice) were generated and are alive and fertile on a C57/BL6 × 129 background.17,18 Unexpectedly, when backcrossing the Mekk1ΔKD/+ heterozygotes into the C57/BL6 background, we observed a dramatic decrease in the frequency of live Mekk1ΔKD embryos that develop past E14.5. At E14.5 all mutant embryos studied, although morphologically normal, were anemic and showed defective definitive erythropoiesis with accumulation of nucleated late erythroblasts.

Materials and methods

Mice

Mekk1ΔKD, Jnk1–/–, and Jnk2–/– mice have been described previously.15,18,19 The Mekk1ΔKD, Jnk1–/–, and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– mice were obtained by crossing Mekk1ΔKD/+ (C57BL/6 × 129/F1) with Jnk1–/– (C57BL/6) or Jnk2–/– (C57BL/6) mice. Mekk1ΔKD/+ (C57BL/6 × 129/F1) were backcrossed to C57BL/6 for 8 generations. Mouse tail DNA was prepared from approximately 1-mm tail snips of embryos and 4-week-old progeny. Genotyping was performed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis of tail- and embryo-derived DNA.

Tissue staining

For endothelial stainings, E13.5 sections of acetone-fixed, paraffin-embedded mouse embryos were stained with MECA-32 Rat IgG2a (B&D Biosciences, San Jose, CA) against mouse panendothelial-cell antigen followed by biotin antirat antibody, and enhanced using the TSA system as described by the manufacturer (NEN, Boston, MA). For macrophage stainings, raw frozen sections of wild-type (wt) and Mekk1ΔKD embryos from E13.5 were stained with phycoerythrin (PE)–conjugated F4/80 (Caltag, Burlingame, CA) and afterward fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde.

Frozen sections of wt and Mekk1ΔKD mice from E13.5 were used for detection of apoptosis using the terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT)–mediated deoxyuridine triphosphate (dUTP) digoxigenin nick end-labeling (TUNEL) staining method. Briefly, sections were boiled in 0.1 M citrate buffer (pH 6.0) in a microwave oven for 2 minutes to permeabilize apoptotic cells. After cooling down, slides were incubated in 0.1 M Tris-HCl, 20% bovine serum albumin (BSA), 3% fetal porcine serum, for 30 minutes at room temperature and immersed in the TUNEL reaction mixture (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) for 1 hour at 37°C in a humidified chamber. Positive cells were visualized in a fluorescence microscope. Slides were viewed using an Axioskop 2 microscope equipped with Plan NEOFLUAR 10×/0.30 or 40×/0.75 objective lenses (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). Images were captured with a ColorSnap digital camera (Photometrics, Tucson, AZ), and were processed using Image Pro Plus software (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD) and Adobe Photoshop 7.0 software (Adobe, San Jose, CA).

Reconstitution of hematopoiesis in lethally irradiated mice

Fetal liver (FL) cells from wt, Mekk1ΔKD, Jnk2–/–,or MEKK Jnk2–/– E14.5 embryos were used to reconstitute lethally irradiated B6.SJL (CD45.1) female mice, exposed to 950 rad of γ irradiation. A total number of 1 × 106 FL cells were injected into the tail vein of the host. Reconstitution of hematopoiesis (red blood cell [RBC] quantity, hematocrit value, hemoglobin concentration, mean corpuscular volume of erythrocytes, white blood cell [WBC] quantity, neutrophil, lymphocyte, monocyte, macrophage, eosinophil, and basophil percentages of total WBCs as well as platelet quantity) was examined with an automatic cell analyzer (Sysmex SF-3000; Kobe, Japan) every 2 weeks after reconstitution, and flow cytometric analysis was performed 12 weeks after reconstitution.

Flow cytometry

Single-cell suspensions of wt, Mekk1ΔKD, Jnk2–/–, or Mekk1 Jnk2–/– fetal livers were obtained at E13. For analysis of reconstituted mice, peripheral blood was collected from retro-orbital veins, and lysis of erythrocytes was performed. Staining of cells for flow cytometry was performed in 0.5% BSA in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) using the following monoclonal antibodies: fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–conjugated anti-CD44 (IM7), anti-CD34 (RAM34) PE, anti–c-kit (CD117) FITC, anti-Ter119 PE, anti-CD45.2 FITC, anti-CD45.1 PE, anti–Gr-1 PE, anti-CD11b (Mac1) PerCP-Cy5.5, anti-CD24 (HSA) biotin, anti-CD4 PE, and anti-CD43 PE (all from B&D Biosciences). Streptavidin TriColor (TC), anti-CD8 TC, and anti-B220 TC were from Caltag. Cell-surface expression of the different markers was analyzed in a Becton Dickinson FACScan Calibur using CellQuest Pro (B&D Biosciences) software; a minimum of 20 000 cells were counted.

RNA analysis

Total RNA was isolated from livers of wt and Mekk1ΔKD, Jnk2–/–, or Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– E13.5 embryos using the TRI REAGENT (Molecular Research Center, Cincinnati, OH) purification method as recommended by the manufacturer. For cDNA synthesis, 1 μg total RNA was converted to cDNA using RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Fermentas) as recommended by the manufacturer. RNase protection assay was performed as previously described20 using an mCK-4 Multi-Probe Template Set from BD Pharmingen (San Jose, CA). Band volume analysis was performed using a Typhoon 9410 variable mode imager and ImageMaster Totallab 2.0 software (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ). The concentrations of stem-cell factor (SCF), interleukin-3 (IL-3), IL-11, IL-7, GM-CSF, M-CSF, G-CSF, LIF, or IL-6 were normalized relative to those of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GADPH) and L32.

Quantitative PCR

Quantitative PCR–based measurement of RNA abundance was carried out using gene-specific double fluorescent–labeled probes and the Brilliant QPCR Master Mix (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA), which uses ROX (Rhodamine-X) passive reference dye to normalize for non-PCR–related fluorescence signal variation. 6-FAM (5-carboxyfluorescein) or in the case of GADPH, HEX (4,7,2′,4′,5′,7′-hexachloro-6-carboxyfluorescein) was the 5′ fluorescent reporter, and Black Hole Quencher (BHQ-1) was added to the 3′ end as a quencher. The following primer and probe sequences were used: Mgadph-571 forward primer (F), 5′-CAATGTGTCCGTCGTGGA-3′; mGADPH-654 reverse primer (R), 5′-GATGCCTGCTTCACCACC-3′; mGADPH-599 probe, 5′-CGCCTGGAGAAACCTGCCAAGTAT-3′, mHgα-105F, 5′-TAGCTTCCCCACCACCAA-3′; mHgα-183R, 5′-CTTGCCGTGACCCTTGAC-3′; mHgα-133 probe, 5′-CTTCACATTTGATGTAAGCCACGGC-3′; mHgβ-327F, 5′-TGCGATCGTGATTGTGCT-3′; mHgβ-435R, 5′-CTTGTGAGCCAGGGCAGT-3′; mHgβ-390 probe, 5′-CTTCCAGAAGGTGGTGGCTGGAGT-3′; mHgζ-157F, 5′-TTCTTAACCCCCCAAGCCC-3′; mHgζ-233R, 5′-TTCTTAACCCCCAAGCCC-3′; mHgζ-182 probe, 5′-TTAGAGCCCATGGCAAGAAAGTGC-3′; mEPO-61F, 5′-GGCCTCCCAGTCCTCTGT-3′; mEPO-168R, 5′-TGCACAACCCATCGTGAC-3′; mEPO-95 probe; 5′-TCTGCGACAGTCGAGTTCTGGAGA-3′; mSCF-616F, 5′-AAGGCCCCTGAAGACTCG-3′; mSCF-701R, 5′-GCTCCAAAAGCAAAGCCA-3′; mSCF-636 probe, 5′-CCTACAATGGACAGCCATGGCATT-3′.

PCR was performed at 95°C for 10 minutes and then cycles at 95°C for 30 seconds, 55°C for 1 minute, and 72°C for 30 seconds, on an Mx3000P real-time PCR system machine (Stratagene).

Results were analyzed as: relative gene transcription = 2(efficiency gene of interest / ct gene of interest – efficiency GADPH / ct GADPH), where ct indicates cycle threshold.

Macrophage phagocytosis assay

FL cells were isolated from E13.5 Jnk2–/–, Mekk1ΔK/+Jnk2–/–, and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– embryos, and were resuspended in complete medium (RPMI plus 10% fetal bovine serum [FBS]) and allowed to attach to plastic (12-well dishes) for 90 minutes at 37°C in 5% CO2. Adherent macrophages (obtained by washing wells in RPMI to remove nonadherent cells) were offered an excess of latex beads (Sigma, St Louis, MO) and further incubated in complete medium for 3 hours. Macrophages were washed in RPMI and stained with hematoxylin. The number of phagocytosed beads per cell were determined by phase-contrast microscopy.

Reconstitution of FLM-erythroblast clusters

Clusters composed of fetal liver macrophages (FLMs) and erythroblasts were isolated as described.21 Briefly, FLs from wt or Mekk1ΔKD E13.5 embryos were placed in prewarmed 0.05% collagenase (Sigma) and 0.002% DNase (Sigma) in RPMI and digested for 1 hour at 37°C with gentle rotation. After tissue dissociation, cells were washed 3 times, suspended in 300 μL complete medium (RPMI plus 10% FBS) and allowed to attach to glass coverslips for 20 minutes at 37°C in 5% CO2. Cells were then flooded with medium and incubated for an additional 4 hours. Adherent macrophages with attached erythroid clusters were obtained by washing coverslips in RPMI to remove nonadherent cells (“native” clusters) before staining with F4/80-PE (Caltag) and biotin-labeled Ter119 antibody (Caltag) followed by visualization using the tyramide amplification system as recommended by the manufacturer, and streptavidine coupled to Alexa 488 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR).

Results

Mekk1ΔKD and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– embryos die in midgestation and are anemic

To identify at which developmental stage embryos deficient in MEKK1 kinase activity die, the phenotypes and genotypes of offspring from Mekk1ΔKD/+ intercrosses (backcrossed into C57/BL6 for 8 generations) were examined between E8.5 and E18.5. Live Mekk1ΔKD embryos at Mendelian frequencies were detected up to midgestation (Table 1). Thereafter, the frequency was considerably lower than expected. To confirm that the effect of MEKK1 in development is mediated through JNK, we crossed the Mekk1ΔKD to JNK1-deficient (Jnk1–/–) and JNK2-deficient (Jnk2–/–) mice.

Genotypes of live offspring from Mekk1ΔKD/+ intercrosses, Mekk1ΔKD/+ Jnk2-/- intercrosses, and Mekk1ΔKD/+ Jnk1-/- intercrosses

. | MEKK1 genotype . | . | . | . | JNK2 genotype . | . | . | . | JNK1 genotype . | . | . | . | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage . | Total (no. of litters) . | Wt (%) . | Mekk1ΔKD/+ (%) . | Mekk1ΔKD (%) . | Total (no. of litters) . | Jnk2-/- (%) . | Jnk2-/- Mekk1ΔKD/+ (%) . | Jnk2-/- Mekk1ΔKD (%) . | Total (no. of litters) . | Jnk1-/- (%) . | Jnk1-/- Mekk1ΔKD/+ (%) . | Jnk1-/- Mekk1ΔKD (%) . | |||||||||

| E8.5 | 9 (1) | 1 (11) | 7 (78) | 1 (11) | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |||||||||

| E10.5 | 9 (1) | 3 (33) | 4 (44) | 2 (22) | 6 (1) | 1 (17) | 3 (50) | 2 (33) | ND | ND | ND | ND | |||||||||

| E12.5 | ND | ND | ND | ND | 53 (6) | 13 (25) | 28 (53) | 12 (23) | ND | ND | ND | ND | |||||||||

| E13.5 | 68 (12) | 18 (26) | 29 (43) | 21 (31) | 78 (12) | 23 (29) | 40 (51) | 15 (19) | 11 (2) | 1 (9) | 7 (63) | 3 (27) | |||||||||

| E14.5 | 125 (19) | 38 (30) | 60 (48) | 27 (22) | 75 (12) | 31 (41) | 29 (39) | 15 (20) | 6 (2) | 0 (0) | 5 (83) | 1 (17) | |||||||||

| E15.5 | 70 (9) | 17 (24) | 47 (67) | 6 (9) | 41 (7) | 7 (17) | 28 (68) | 6 (15) | 8 (2) | 3 (37) | 5 (62) | 0 (0) | |||||||||

| E16.5 | 22 (3) | 8 (36) | 13 (59) | 1 (5) | 16 (3) | 4 (25) | 11 (69) | 1 (6) | ND | ND | ND | ND | |||||||||

| E17.5 | 18 (3) | 5 (28) | 12 (67) | 1 (5) | 36 (5) | 10 (28) | 26 (72) | 0 (0) | ND | ND | ND | ND | |||||||||

| E18.5 | 13 (2) | 4 (31) | 9 (69) | 0 (0) | ND | ND | ND | ND | 3 (1) | 1 (33) | 2 (66) | 0 (0) | |||||||||

| Postnatal | 217 (42) | 78 (36) | 135 (62) | 4 (2) | 291 (57) | 115 (40) | 176 (60) | 0 (0) | 30 (11) | 11 (37) | 19 (63) | 0 (0) | |||||||||

. | MEKK1 genotype . | . | . | . | JNK2 genotype . | . | . | . | JNK1 genotype . | . | . | . | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage . | Total (no. of litters) . | Wt (%) . | Mekk1ΔKD/+ (%) . | Mekk1ΔKD (%) . | Total (no. of litters) . | Jnk2-/- (%) . | Jnk2-/- Mekk1ΔKD/+ (%) . | Jnk2-/- Mekk1ΔKD (%) . | Total (no. of litters) . | Jnk1-/- (%) . | Jnk1-/- Mekk1ΔKD/+ (%) . | Jnk1-/- Mekk1ΔKD (%) . | |||||||||

| E8.5 | 9 (1) | 1 (11) | 7 (78) | 1 (11) | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |||||||||

| E10.5 | 9 (1) | 3 (33) | 4 (44) | 2 (22) | 6 (1) | 1 (17) | 3 (50) | 2 (33) | ND | ND | ND | ND | |||||||||

| E12.5 | ND | ND | ND | ND | 53 (6) | 13 (25) | 28 (53) | 12 (23) | ND | ND | ND | ND | |||||||||

| E13.5 | 68 (12) | 18 (26) | 29 (43) | 21 (31) | 78 (12) | 23 (29) | 40 (51) | 15 (19) | 11 (2) | 1 (9) | 7 (63) | 3 (27) | |||||||||

| E14.5 | 125 (19) | 38 (30) | 60 (48) | 27 (22) | 75 (12) | 31 (41) | 29 (39) | 15 (20) | 6 (2) | 0 (0) | 5 (83) | 1 (17) | |||||||||

| E15.5 | 70 (9) | 17 (24) | 47 (67) | 6 (9) | 41 (7) | 7 (17) | 28 (68) | 6 (15) | 8 (2) | 3 (37) | 5 (62) | 0 (0) | |||||||||

| E16.5 | 22 (3) | 8 (36) | 13 (59) | 1 (5) | 16 (3) | 4 (25) | 11 (69) | 1 (6) | ND | ND | ND | ND | |||||||||

| E17.5 | 18 (3) | 5 (28) | 12 (67) | 1 (5) | 36 (5) | 10 (28) | 26 (72) | 0 (0) | ND | ND | ND | ND | |||||||||

| E18.5 | 13 (2) | 4 (31) | 9 (69) | 0 (0) | ND | ND | ND | ND | 3 (1) | 1 (33) | 2 (66) | 0 (0) | |||||||||

| Postnatal | 217 (42) | 78 (36) | 135 (62) | 4 (2) | 291 (57) | 115 (40) | 176 (60) | 0 (0) | 30 (11) | 11 (37) | 19 (63) | 0 (0) | |||||||||

Surviving fetuses were defined as those with beating heart at the time of dissection. Unless noted otherwise, data are expressed as the number of embryos, with percentages within parenthesis.

ND indicates not determined.

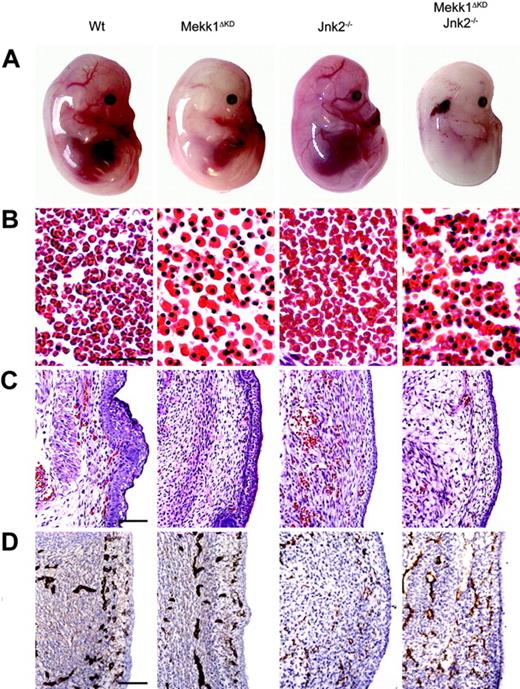

Although a small number of Mekk1ΔKD mice survived to adulthood, the double-deficient mice (Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– and Mekk1ΔKDJnk1–/–) all died during embryonic development (Table 1). The phenotype of Mekk1ΔKDJnk1–/– and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– was identical to that of the Mekk1ΔKD embryos (Figure 1, data not shown). However, as the breeding efficiency of the Mekk1ΔKD/+Jnk1–/– intercrosses was very low, only limited studies were performed on these mice. The majority of the work in this study was performed on Mekk1ΔKD and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– mice.

At E14.5, live Mekk1ΔKD and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– embryos, macroscopically, were paler than wt counterparts and their major blood vessels lacked color (Figure 1A). The FL was smaller, hypocellular, and liver necrosis as well as erythroplaki of the head and neck region was occasionally observed. In order to establish the cause of death, we performed various histologic and immunohistochemical analysis of E14.5 to E16.5 Mekk1ΔKD and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– embryos. Histologic examination of wt, Mekk1ΔKD, and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– fetuses revealed a marked increase in the number of nucleated erythrocytes in circulation. While blood vessels of wt and Jnk2–/– embryos contained mostly enucleated erythrocytes; the erythrocytes found in blood vessels of Mekk1ΔKD and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– embryos were mostly nucleated and very few mature red blood cells were detected (Figure 1B; Table 2). The altered blood picture correlated with a decrease in the total amount of circulating erythrocytes in Mekk1ΔKD and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– embryos (Figure 1C). These data show that Mekk1ΔKD and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– fetuses are severely anemic just prior to their death.

Increased amount of orthochromatic normoblasts in Mekk1ΔKD and Jnk2-/- MEKK1ΔKD fetuses

. | Genotype . | . | . | . | . | . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Wt* . | . | Mekk1ΔKD . | . | Jnk2-/- Mekk1ΔKD . | . | |||||

| Stage . | Orthochromatic normoblasts in circulation, % . | N . | Orthochromatic normoblasts in circulation, % . | N . | Orthochromatic normoblasts in circulation, % . | N . | |||||

| E11.5 | 100 ± 0 | 5 | ND | ND | ND | ND | |||||

| E12.5 | 83 ± 4 | 6 | ND | ND | ND | ND | |||||

| E13.5 | 44 ± 14 | 8 | 64 | 1 | ND | ND | |||||

| E14.5 | 23 ± 8 | 7 | 72 ± 15† | 6 | 83 ± 10† | 7 | |||||

| E15.5 | 2 ± 3 | 6 | 80 | 1 | 50 ± 15† | 6 | |||||

| E16.5 | 0 ± 0 | 7 | 74 | 1 | ND | ND | |||||

. | Genotype . | . | . | . | . | . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Wt* . | . | Mekk1ΔKD . | . | Jnk2-/- Mekk1ΔKD . | . | |||||

| Stage . | Orthochromatic normoblasts in circulation, % . | N . | Orthochromatic normoblasts in circulation, % . | N . | Orthochromatic normoblasts in circulation, % . | N . | |||||

| E11.5 | 100 ± 0 | 5 | ND | ND | ND | ND | |||||

| E12.5 | 83 ± 4 | 6 | ND | ND | ND | ND | |||||

| E13.5 | 44 ± 14 | 8 | 64 | 1 | ND | ND | |||||

| E14.5 | 23 ± 8 | 7 | 72 ± 15† | 6 | 83 ± 10† | 7 | |||||

| E15.5 | 2 ± 3 | 6 | 80 | 1 | 50 ± 15† | 6 | |||||

| E16.5 | 0 ± 0 | 7 | 74 | 1 | ND | ND | |||||

Plus/minus values represent standard deviation. Values that are given without standard deviation are for cases in which only one mouse was analyzed.

ND indicates not determined.

Jnk2-/- and Mekk1ΔKD/+ were identical to wt.

P < .05 compared with wt.

Mekk1ΔKD and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– embryos are anemic and exhibit a striking increase in the number of nucleated erythrocytes. (A) E14.5 wt, Mekk1ΔKD, Jnk2–/–, and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– mouse embryos (Theiler stages 1, 2). Note the absence of color in major blood vessels, the general paleness, and the smaller liver of the Mekk1ΔKD and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– embryos. Also note the erythroplaki of the Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– embryo. (B) Sections through major blood vessels of wt and Mekk1ΔKD (E15.5), and Jnk2–/– and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– (E14.5) embryos stained with H&E. Note the almost complete absence of enucleated erythrocytes in the Mekk1ΔKD and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– embryos. Bar = 75 μm. (C) Subcutaneous sections of wt, Mekk1ΔKD (E15.5), Jnk2–/–, and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– (E14.5) embryos stained with H&E. Note marked decrease in the number of circulating erythrocytes in the Mekk1ΔKD and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– samples. Bar = 100μm. (D) Subcutaneous panendothelium stained sections of E13.5 wt, Mekk1ΔKD, Jnk2–/–, and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– embryos. Bar = 100 μm.

Mekk1ΔKD and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– embryos are anemic and exhibit a striking increase in the number of nucleated erythrocytes. (A) E14.5 wt, Mekk1ΔKD, Jnk2–/–, and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– mouse embryos (Theiler stages 1, 2). Note the absence of color in major blood vessels, the general paleness, and the smaller liver of the Mekk1ΔKD and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– embryos. Also note the erythroplaki of the Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– embryo. (B) Sections through major blood vessels of wt and Mekk1ΔKD (E15.5), and Jnk2–/– and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– (E14.5) embryos stained with H&E. Note the almost complete absence of enucleated erythrocytes in the Mekk1ΔKD and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– embryos. Bar = 75 μm. (C) Subcutaneous sections of wt, Mekk1ΔKD (E15.5), Jnk2–/–, and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– (E14.5) embryos stained with H&E. Note marked decrease in the number of circulating erythrocytes in the Mekk1ΔKD and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– samples. Bar = 100μm. (D) Subcutaneous panendothelium stained sections of E13.5 wt, Mekk1ΔKD, Jnk2–/–, and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– embryos. Bar = 100 μm.

The early lethality of the Jnk1–/–Jnk2–/– double-knockout embryos makes the total contribution of JNK in hematopoiesis difficult to study in vivo. Additionally, redundancy between the JNK isoforms may compensate for the loss of one gene or the other. Nevertheless, in order to investigate whether the relative contribution of JNK1 or JNK2 became more apparent during conditions of anemia, we examined reconstitution of hematopoiesis in Jnk1–/– and Jnk2–/– mice 3 days after induction of severe anemia. However, Sysmex Counter Analysis revealed no differences compared with wt controls in any of the parameters investigated, including RBC quantity, hematocrit value, hemoglobin concentration, and mean corpuscular volume of erythrocytes (Supplemental Figure S1A-D, available at the Blood website; click on the Supplemental Figures link at the top of the online article). Similarly, the WBC quantity, percentages of neutrophils, basophils, eosinophils, monocytes, and lymphocytes were indistinguishable between Jnk1–/–, Jnk2–/–, and wt mice (data not shown). These data suggest that redundancy between the JNK isoforms may compensate for the loss of either JNK1 or JNK2 also during hematopoiesis.

p38-deficient mice are anemic and succumb in 2 separate waves of embryonic lethality.10,22-24 A fraction of the embryos develop past E16.5 where they die due to failed erythropoiesis.10 However, the first critical time point occurs around E12.5. Two independent studies22,23 have suggested that the early lethality is due to placental insufficiencies. Both studies noted an abnormal morphology with reduction in the labyrinthine layer and lack of intermingling embryonic and maternal blood vessels consistent with a lack of normal vascularization. We found no abnormalities in the morphology of placentas from Mekk1ΔKD or Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– fetuses on E13.5. Gross morphology as well as closer examination revealed normal layer organization with fetal blood vessels penetrating into the labyrinthine and spongiotrophoblast layers (Supplemental Figure S2A-B). Neither could we observe any differences in endothelial development between wt, Mekk1ΔKD, and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– fetuses as judged by immunohistochemical staining (Figure 1D).

Defective definitive erythropoiesis in Mekk1ΔKD embryos

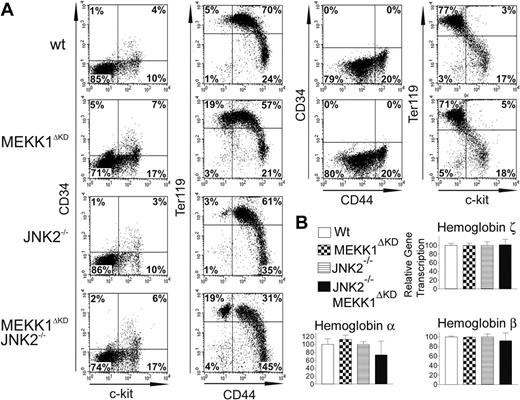

We examined FL hematopoiesis in E13.5 wt, Mekk1ΔKD, and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– embryos by flow cytometry using markers that are characteristic of different hematopoietic cell types and developmental stages, including CD34 (detecting hematopoietic progenitors), CD44 (detecting all hematopoietic cells), c-kit (hematopoietic stem cells), and Ter119 (erythroid cells).25-28

Analysis of FL single-cell suspensions revealed an increase in the relative fraction of CD34lowc-kitpos cells (representing a population of hematopoietic stem cells capable of long-term reconstitution)29 in Mekk1ΔKD as well as Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– fetal livers as compared with wt or Jnk2–/– FLs (Figure 2A). Fetal livers of Mekk1ΔKD and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– embryos also exhibited a modest increase in the relative abundance of CD34posc-kitneg cells (Figure 2A).

The relative overproduction of hematopoietic stem cells and progenitors in Mekk1ΔKD and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– fetal livers could be a compensatory response to anemia. Indeed, Mekk1ΔKD and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– fetal livers showed a substantial increase in Ter119pos CD44neg cells (Figure 2A). Ter119pos cells are committed erythropoietic precursors beyond the CFU-E stage25,27 and CD44 expression is down-regulated during the final steps of erythroid-cell differentiation.26 These data support our histologic observations (Figure 1B) and suggest that the larger population of Ter119pos CD44neg cells observed in Mekk1ΔKD and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– as compared with control FLs represent an increase of cells very late in erythropoietic development. These results were confirmed using a recently developed flow cytometric assay30 that distinguishes various stages of erythroid-cell differentiation based on double-staining FL cells with anti-CD71 and anti-Ter119. Double staining of E13.5 FL cells from Mekk1ΔKD embryos revealed a substantial increase in the percentage of chromatophilic/orthocromatophilic erythroblasts as compared with wt littermate embryos (Supplemental Figure S3).

Further support for a defect in erythropoiesis at a stage beyond hemoglobin synthesis in Mekk1ΔKD and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– embryos was provided by quantitative (Q) PCR analysis of globin mRNA expression. The levels of ζ-globin mRNA, which is expressed exclusively during primitive erythropoiesis,31 were equal in wt, Mekk1ΔKD, and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– fetal livers (Figure 2B), showing that the nucleated erythroblasts found in the circulation of Mekk1ΔKD and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– embryos are not yolk sac derived. The levels of α-globin, expressed both during primitive and definitive erythropoiesis and the expression of βmajor-globin transcripts, which first appear in the FL during definitive erythropoiesis, were also similar in wt, Mekk1ΔKD, and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– FLs (Figure 2B). As the βmajor-globin expression maximum is not reached until the polychromatic erythroblast stage,32-34 the defect in the erythropoietic development must occur beyond this stage. We also analyzed hemoglobin chain expression at the protein level by tricine gel analysis8 and no abnormalities were observed (data not shown).

Definitive erythropoiesis is defective in Mekk1ΔKD and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– embryos. Flow cytometry of FL hematopoietic cells from E13.5 wt, Mekk1ΔKD, Jnk2–/–, and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– embryos and relative expression of globin genes in E13.5 FL of wt, Mekk1ΔKD, Jnk2–/–, and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– embryos. (A) Expression of different cell-surface markers is depicted. Cell suspensions from E13.5 FLs were labeled with anti–c-kit, which marks hematopoietic stem cells; anti-CD44, which marks all hematopoietic cells; anti-Ter119, to identify differentiated erythroid cells; or anti-CD34 to mark hematopoietic progenitors. The dot plots represent the log fluorescence intensities of live cells. (B) Relative expression of globin chains was measured by real-time PCR. The ζ globin chain is found only in yolk sac–derived erythroblasts. The α globin chain is found in both yolk sac–derived and FL-derived erythroblasts. The βmajor globin chain is found only in FL-derived erythroblasts and is continuously expressed until just prior to enucleation. GADPH mRNA levels were used for normalization in all cases. Percentage of cells in each quadrant is indicated. Data represent the average ± standard deviation (SD) from 3 to 5 animals per group.

Definitive erythropoiesis is defective in Mekk1ΔKD and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– embryos. Flow cytometry of FL hematopoietic cells from E13.5 wt, Mekk1ΔKD, Jnk2–/–, and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– embryos and relative expression of globin genes in E13.5 FL of wt, Mekk1ΔKD, Jnk2–/–, and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– embryos. (A) Expression of different cell-surface markers is depicted. Cell suspensions from E13.5 FLs were labeled with anti–c-kit, which marks hematopoietic stem cells; anti-CD44, which marks all hematopoietic cells; anti-Ter119, to identify differentiated erythroid cells; or anti-CD34 to mark hematopoietic progenitors. The dot plots represent the log fluorescence intensities of live cells. (B) Relative expression of globin chains was measured by real-time PCR. The ζ globin chain is found only in yolk sac–derived erythroblasts. The α globin chain is found in both yolk sac–derived and FL-derived erythroblasts. The βmajor globin chain is found only in FL-derived erythroblasts and is continuously expressed until just prior to enucleation. GADPH mRNA levels were used for normalization in all cases. Percentage of cells in each quadrant is indicated. Data represent the average ± standard deviation (SD) from 3 to 5 animals per group.

These results were further confirmed by measuring the ability of cells, derived from E14.5 wt and Mekk1ΔKD FLs, to form immature BFU-Es as well as the more mature CFU-Es. These colony types reflect the presence of committed erythroid progenitors.35 As expected, we observed no significant difference in the frequency of immature BFU-Es, mature BFU-Es, and CFU-Es formed from wt and Mekk1ΔKD fetal liver cells (Supplemental Figure S4A-C). We also examined the ability of Mekk1ΔKD FLs in leukocyte development and found no defects in granulocyte macrophage–CFU (CFU-GM) or granulocyte-erythrocyte-macrophage-megakaryocyte–CFU (CFU-GEMM) development (Supplemental Figure S4D-E). Collectively, these results show that primitive blood-cell development proceeds normally in Mekk1ΔKD and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– embryos but definitive erythropoiesis is severely defective at the orthochromatic erythroblast stage.

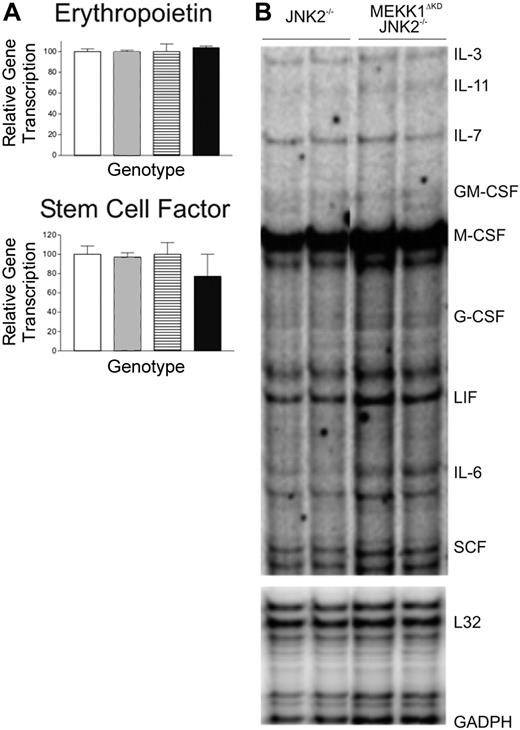

Hematopoietic growth factors and cytokines are produced in normal amounts in Mekk1ΔKD embryos

Numerous studies have implicated the MAP kinases in the production of various cytokines as well as in the cellular response to these cytokines. We therefore explored the possibility that MEKK1 may be required for optimal expression of erythropoietin, SCF, or other hematopoietic growth factors. RNA was extracted from FLs of morphologically normal and viable E13.5 wt, Mekk1ΔKD, Jnk2–/–, and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– embryos. The RNA levels of erythropoietin and SCF were first examined by Q-PCR analysis and the relative amount of IL-3, IL-11, IL-7, GM-CFS, M-CSF, G-CSF, LIF, IL-6, and SCF RNA transcripts was further examined by RPA analysis. However, no difference in the relative amounts of RNA was detected between wt, Mekk1ΔKD, and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– samples (Figure 3A-B). To confirm that the RNA expression levels were reflected at the protein level, we performed Western blot analysis of FL protein extractions for SCF and erythropoietin, as well as immunohistochemistry for SCF. No differences were found (data not shown).

Mekk1ΔKD hematopoietic stem cells reconstitute lethally irradiated hosts

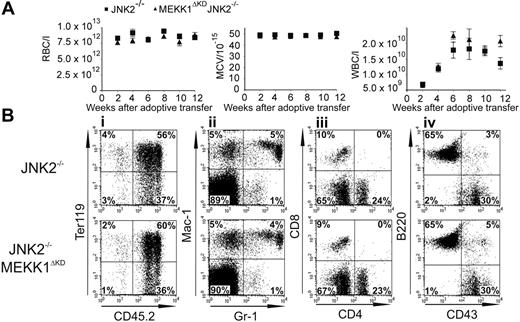

Our data suggest that the major aberration in Mekk1ΔKD and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– embryos, which lead to a defect in definitive erythropoiesis, is insufficient enucleation. To examine whether the enucleation deficiency was intrinsic to the Mekk1ΔKD and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– maturing blood cells or extrinsic, we tested the ability of Mekk1ΔKD and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– fetal liver hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) to reconstitute hematopoiesis in lethally irradiated hosts. Adult B6.SJL mice, which express the CD45.1 antigen, were lethally irradiated and injected with single-cell suspensions of E14.5 Jnk2–/– or Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– FL cells, which express the CD45.2 antigen. While mock-injected lethally irradiated mice did not survive beyond 2 weeks, mice reconstituted with either Jnk2–/– or Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– FL cells survived until the end of the study (4 months). Every 2 weeks after reconstitution, peripheral blood was analyzed for RBC quantity, hematocrit value, hemoglobin concentration, mean corpuscular volume of erythrocytes, WBC quantity, and percentages of neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, macrophages, eosinophils, and basophils as well as platelet quantity by Sysmex Counter Analysis (Figure 4A and Supplemental Figure S5). The mean corpuscular volume of erythrocytes correlates with their maturation state; orthochromatic erythroblasts are much larger than mature erythrocytes and can therefore be envisioned by this analysis. Furthermore, blood smears were made from the peripheral blood and analyzed for the presence of nucleated erythrocytes; all samples from Jnk2–/– and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– reconstituted animals contained exclusively mature erythrocytes (data not shown).

Cytokine production in Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– fetal livers are unaltered. (A) Quantitative (Q) PCR analysis of erythropoetin and SCF cDNA from E13.5 wt, Mekk1ΔKD, Jnk2–/–, and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– FLs (n = 5). □ indicates wt; ▦, MEKK1ΔKD; ▤, JNK2–/–; ▪, MEKK1ΔKDJNK2–/–. Data represent average ± SD. (B) Representative samples from RNase protection analysis of SCF, EPO, IL-3, IL-11, IL-7, GM-CSF, M-CSF, G-CSF, LIF, and IL-6 mRNA expression in E13.5 Jnk2–/– and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– FLs. GADPH and L32 were measured as controls. GM-CSF indicates granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor; GADPH, glyceraldehyde-3 phosphate dehydrogenase; and LIF, leukemia inhibitory factor.

Cytokine production in Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– fetal livers are unaltered. (A) Quantitative (Q) PCR analysis of erythropoetin and SCF cDNA from E13.5 wt, Mekk1ΔKD, Jnk2–/–, and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– FLs (n = 5). □ indicates wt; ▦, MEKK1ΔKD; ▤, JNK2–/–; ▪, MEKK1ΔKDJNK2–/–. Data represent average ± SD. (B) Representative samples from RNase protection analysis of SCF, EPO, IL-3, IL-11, IL-7, GM-CSF, M-CSF, G-CSF, LIF, and IL-6 mRNA expression in E13.5 Jnk2–/– and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– FLs. GADPH and L32 were measured as controls. GM-CSF indicates granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor; GADPH, glyceraldehyde-3 phosphate dehydrogenase; and LIF, leukemia inhibitory factor.

Additionally, cell-surface markers characteristic of donor-derived erythroid, myeloid, and lymphoid cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. The reconstitution capacity of Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– FL cells was identical to that of Jnk2–/– cells, and in all cases remaining host-derived cells accounted for less than 5% of total CD45+ cells. In all cases, complete reconstitution of erythroid, myeloid (granulocytes, monocytes), and lymphoid (B and T) cells was observed (Figure 4B). Additionally, fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis of bone marrow cells from the reconstituted animals revealed no difference in percentages of donor-derived bone marrow macrophages (Jnk2–/–, 13.3% ± 1.2%; Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/–, 14.2% ± 1.6%; n = 4). Nor did hematoxylin and eosin (H & E) stains on sections from the bone marrow of the reconstituted animals show any abnormalities (Supplemental Figure S6). Thus, the erythropoietic deficiency of Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– mice is not cell autonomous and can be rescued by host-derived factor(s). We also tested the ability of Mekk1ΔKD FL cells to reconstitute lethally irradiated hosts with identical results (data not shown).

Reconstitution of hematopoiesis by adoptive transfer of Jnk2–/– and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– fetal liver cells. Peripheral blood was drawn every 2 weeks after adoptive transfer of FL cells from Jnk2–/– or Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/–m E14.5 embryos into lethally irradiated hosts. (A) Samples were analyzed for red blood cell (RBC) quantity, mean corpuscular volume (MCV) of the red blood cells, and white blood cell (WBC) quantity. (B) Peripheral blood cells were drawn 12 weeks after adoptive transfer. Samples were analyzed for cell-surface expression of different lineage markers. The dot plots represent the log fluorescence intensities of live cells (i), or live cells falling into the CD45.2 gate (ii-iv). Monoclonal antibodies used were against Ter119 (erythroid cells), Gr-1 (granulocytes), Mac1 (monocytes), CD4 and CD8 (T lymphocytes), B220 (B lymphocytes), and CD43 (leukocytes). The percentages of cells in each quadrant are indicated.

Reconstitution of hematopoiesis by adoptive transfer of Jnk2–/– and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– fetal liver cells. Peripheral blood was drawn every 2 weeks after adoptive transfer of FL cells from Jnk2–/– or Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/–m E14.5 embryos into lethally irradiated hosts. (A) Samples were analyzed for red blood cell (RBC) quantity, mean corpuscular volume (MCV) of the red blood cells, and white blood cell (WBC) quantity. (B) Peripheral blood cells were drawn 12 weeks after adoptive transfer. Samples were analyzed for cell-surface expression of different lineage markers. The dot plots represent the log fluorescence intensities of live cells (i), or live cells falling into the CD45.2 gate (ii-iv). Monoclonal antibodies used were against Ter119 (erythroid cells), Gr-1 (granulocytes), Mac1 (monocytes), CD4 and CD8 (T lymphocytes), B220 (B lymphocytes), and CD43 (leukocytes). The percentages of cells in each quadrant are indicated.

Reduced number of FL macrophages in Mekk1ΔKD embryos

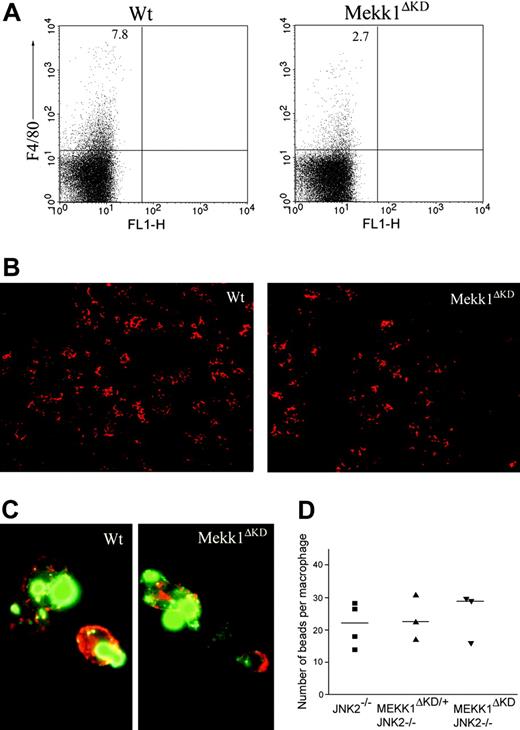

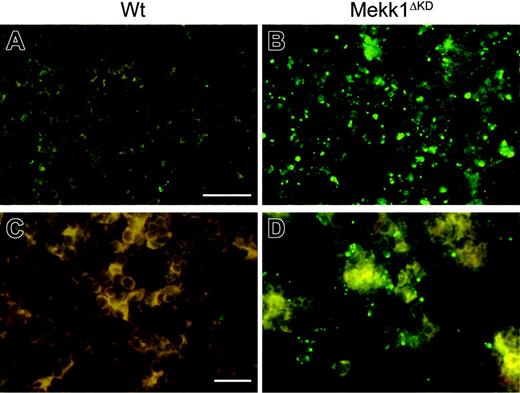

To examine the cause for the impaired enucleation activity in Mekk1ΔKD and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– embryos, we analyzed FLs for the presence and function of macrophages. Immunohistochemical staining, using the macrophage-specific marker F4/80, indicated reduced numbers of FLMs in Mekk1ΔKD and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– embryos compared with wt or Jnk2–/– mice (Figure 5B). We therefore analyzed E13.5 FL-cell suspensions by FACS for the presence of F4/80-positive cells. The percentage of FLMs in Mekk1ΔKD and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– embryos was significantly reduced (3% compared with 8%; n = 5) in wt or Jnk2–/– mice (Figure 5A). To examine whether MEKK1 is required for the ability of FLMs to bind erythroblasts, we used a recently described macrophage-erythroblast coculture assay.21 E13.5 FLs were partially digested with collagenase and FLMs were selectively allowed to bind to a substrate for a short-term incubation. The cultures were subsequently stained and analyzed by fluorescence microscopy for the presence of clusters composed of F4/80-positive FLMs and Ter119-positive erythroblasts. Although substantially lower numbers of macrophages were present in the Mekk1ΔKD FL cultures, the macrophages present were able to bind Ter119-positive cells (Figure 5C). Next, we analyzed whether the phagocytic ability of the FLMs was impaired, using an in vitro phagocytosis assay. The ability of Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– FLMs to engulf latex beads was not inferior to FLMs from wt embryos (Figure 5D). Moreover, transmission electron microscopy of E13.5 FL sections revealed the presence of erythoroblastic islands in Mekk1ΔKD FLs (Supplemental Figure S7). We next examined whether the clearance of apoptotic cells was impaired in Mekk1ΔKD and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– FLs. Indeed, a substantial increase of TUNEL-positive cells was detected in Mekk1ΔKD FLs (Figure 6B, and in higher magnification D). These apoptotic foci did not colocalize with Ter119-positive cells (Supplemental Figure S8), suggesting that expelled nuclei from erythroblasts accumulate in Mekk1ΔKD and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– FLs. The accumulation of partly degraded DNA appeared specific to the liver, since we observed no increase of apoptotic foci in any other tissue (including brain, lung, heart, kidney, intestine, and extremities; data not shown).

Decreased number of fetal liver macrophages in Mekk1ΔKD embryos. (A) Fetal liver cell suspensions from wt and Mekk1ΔKD E13.5 embryos were stained with macrophage-specific anti-F4/80 antibodies and analyzed by flow cytometry. The dot plots represent the log fluorescence intensities of live cells. Numbers indicate the percentage of F4/80-positive cells. (B) Immunohistochemical staining of E13.5 fetal liver sections from wt and Mekk1ΔKD embryos with PE-conjugated anti-F4/80. (C) Immunohistochemistry of “native” erythroblast-FLM clusters from wt and Mekk1ΔKD E13.5 embryos. Cell clusters were stained for F4/80 (red) and Ter119 (green). (D) E13.5 FLMs were isolated from Jnk2–/–, Mekk1ΔKD/+Jnk2–/–, and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– embryos and offered an excess of latex beads in an in vitro phagocytosis assay. Macrophages were counterstained with hematoxylin and the number of phagocytosed beads per cell was counted by phase-contrast microscopy. A minimum of 3 FLs was examined per genotype.

Decreased number of fetal liver macrophages in Mekk1ΔKD embryos. (A) Fetal liver cell suspensions from wt and Mekk1ΔKD E13.5 embryos were stained with macrophage-specific anti-F4/80 antibodies and analyzed by flow cytometry. The dot plots represent the log fluorescence intensities of live cells. Numbers indicate the percentage of F4/80-positive cells. (B) Immunohistochemical staining of E13.5 fetal liver sections from wt and Mekk1ΔKD embryos with PE-conjugated anti-F4/80. (C) Immunohistochemistry of “native” erythroblast-FLM clusters from wt and Mekk1ΔKD E13.5 embryos. Cell clusters were stained for F4/80 (red) and Ter119 (green). (D) E13.5 FLMs were isolated from Jnk2–/–, Mekk1ΔKD/+Jnk2–/–, and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– embryos and offered an excess of latex beads in an in vitro phagocytosis assay. Macrophages were counterstained with hematoxylin and the number of phagocytosed beads per cell was counted by phase-contrast microscopy. A minimum of 3 FLs was examined per genotype.

A previous study has reported accumulation of phagolysosomes containing undigested nucleic material in FLMs from embryos lacking DNAse II.8 However, transmission electron microscopy of FLMs from Mekk1ΔKD embryos revealed no abnormal structures (Supplemental Figure S7).

Discussion

We have discovered a new physiologic function for the MAPK pathway in embryonic development. In the present study we provide evidence strongly suggesting that MEKK1-JNK signaling is required for degradation of nuclear DNA extruded from erythroid precursors during the late stages of definitive erythropoiesis in the fetal liver.

Several targeted gene approaches have been used to evaluate the biologic function of the JNK signaling pathway in mice. The first studies in which the JNK genes were individually disrupted produced mice that appeared morphologically normal, suggesting that the JNK genes were able to complement each other in most tissues. Animals deficient in both JNK1 and JNK3 or JNK2 and JNK3 survive normally, whereas Jnk1–/–Jnk2–/– mice die during embryonic development due to severe dysregulation of apoptosis in the brain.36 The early lethality of the Jnk1–/–Jnk2–/– double-knockout embryos makes the total contribution of JNK in hematopoiesis difficult to estimate. However, the relative contribution of JNK1 or JNK2 may become more apparent during conditions of anemia in the Jnk1–/– or Jnk2–/– mice. We therefore examined reconstitution of hematopoiesis in Jnk1–/– and Jnk2–/– mice 3 days after challenging them with severe anemia. However, we observed no differences compared to wt controls in any of the parameters investigated, suggesting that redundancy between the JNK isoforms may compensate for the loss of either JNK1 or JNK2 also during hematopoiesis.

Mice deficient for the upstream JNK regulators MKK4 and MKK7 are also embryonic lethal. MKK4-deficient embryos, similarly to c-Jun–deficient animals,37,38 suffer from severe anemia and die at E10.5 to E12.5 from abnormal liver development,39,40 suggesting that MKK4 is required for c-Jun activation during embryonic development. The cause of death in MKK7–/– embryos remains inconclusive.41 Disruption of activators further upstream of MKK4 and MKK7 within the MEKK family includes (in addition to MEKK1) MEKK2 and MEKK3. MEKK2-deficient mice develop normally and are fertile.42 In contrast, mice lacking MEKK3 die at E11 due to failure of cardiovascular development.43 Previous studies on MEKK1-deficient (Mekk1–/–) and MEKK1 kinase–deficient (Mekk1ΔKD) mice have suggested that these mice develop normally with the exception of a defect in eyelid closure, a phenotype that is associated with control of cell migration.18,44 However, the Mekk1–/– or Mekk1ΔKD mice used in previous studies have, to the best of our knowledge, all been C57/BL6 × 129 hybrids. We observed a skewing of the Mendelian frequencies of live pups born after intercrossing the Mekk1ΔKD/+ C57/BL/6 × 129 hybrids (Mekk1+/+ = 29.2%, Mekk1ΔKD/+ = 52.8%, Mekk1ΔKD = 19.9%; n = 232). This skewing was influenced by the genetic background, since fewer than 2% Mekk1ΔKD pups were born after backcrossing into the C57/BL6 background. Nevertheless, crossing the Mekk1ΔKD/+ C57/BL/6 × 129 hybrids with Jnk1–/– or Jnk2–/– mice resulted in embryonic lethality of all Mekk1ΔKDJnk1–/– and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– embryos (regardless of background), suggesting that an intact MEKK1-JNK signaling pathway is required for normal embryonic development. Mekk1ΔKD, Mekk1ΔKDJnk1–/–, and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– embryos have identical phenotypes, survive up to midgestation, and display normal morphology but are highly anemic. Interestingly, a similar phenotype has been observed in p38α-deficient mice.10 However, while the anemia in p38α–/– mice is attributed to defective erythropoietin gene expression, normal levels of erythropoietin at both mRNA and protein level were observed in FLs from Mekk1ΔKD and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– embryos. In addition to erythropoietin, we also investigated the expression levels of other growth factors and cytokines suggested to be involved in hematopoietic development, including SCF, IL-3, IL-6, IL-7, IL-11, GM-CFS, M-CFS, G-CFS, and LIF. However, we observed no differences when compared with FLs from wt controls. The FLs of Mekk1ΔKD and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– also contain BFU-Es and CFU-Es formed at normal frequencies, and can reconstitute erythropoiesis in lethally irradiated hosts. It is therefore clear that MEKK1 is not required for the production of, or the response to, cytokines and/or growth factors required for the expansion and differentiation of erythroid progenitors up to the stage where the orthochromatic erythroblasts lose their nuclei and become reticulocytes.

Defective degradation and accumulation of TUNEL-positive nucleic material in Mekk1ΔKD fetal livers. Histochemical analysis of FLs. Nucleic material in wt and Mekk1ΔKD FLs, as shown by TUNEL stain (green). Note the large amount of abnormal apoptotic foci in the Mekk1ΔKD fetal liver B, and in higher magnification D. A, B: bar = 75 μm; C, D: bar = 100 μm.

Defective degradation and accumulation of TUNEL-positive nucleic material in Mekk1ΔKD fetal livers. Histochemical analysis of FLs. Nucleic material in wt and Mekk1ΔKD FLs, as shown by TUNEL stain (green). Note the large amount of abnormal apoptotic foci in the Mekk1ΔKD fetal liver B, and in higher magnification D. A, B: bar = 75 μm; C, D: bar = 100 μm.

Interestingly, the phenotype of mice lacking DNaseII (a lysosomal DNase in macrophages) is almost identical to Mekk1ΔKD and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– embryos. DNaseII–/– mice die before birth, suffer from severe anemia, and exhibit accumulation of erythroblasts that fail to undergo enucleation.8,9 This anemic phenotype is a consequence of macrophages failing to aid in digestion of nuclear DNA expelled from erythroblasts during definitive erythropoiesis.8 In our study, FLs from Mekk1ΔKD and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– embryos contain reduced levels of macrophages and TUNEL stains showed extensive accumulation of apoptotic bodies in the FLs of Mekk1ΔKD and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– mice. These apoptotic bodies did not colocalize with Ter119-positive erythroblasts but rather appeared free in the extra cellular space, suggesting that they represent nuclear DNA extruded from erythroid precursor cells. Since the phagocytic capacity of FLMs from Mekk1ΔKD and Mekk1ΔKDJnk2–/– was found to be similar to wt fetal liver macrophages, our data indicate that the observed accumulation of nucleated erythroblasts is dependent quantitatively rather than qualitatively on FLMs. In conclusion, we have shown that a functional MEKK1-JNK signaling pathway is critically required for macrophage-assisted, erythroblast nuclear enucleation during FL erythropoiesis. The role for macrophages in phagocytosis and degradation of erythroblast nuclei during erythropoiesis has been established.8,21 Morover, FLMs are part of a delicate microenvironment where communication through soluble mediators (ie, cytokines), direct cell-to-cell contacts between stromal cells (including fibroblasts, endothelial cells, epithelial cells, and FLMs), and cell-matrix interactions are in crucial balance, ultimately supporting erythropoiesis. Whether or how the MEKK1-JNK signaling pathway is required for factors extrinsic to FLMs during development, differentiation, proliferation, and/or maturation remains to be investigated.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, August 4, 2005; DOI 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1739.

Supported in part by The Danish Medical Research Councils (SSVF), The Alfred Benzon Foundation, The Johann Weiman F. Seedorff and Wife Foundation (Købmand i Odense Johann og Hanne Weimann f. Seedorff's Legat), The Leo Foundation, The Willumsen Foundation (Fabrikant Einar Willumsens Mindelegat), The Danielsen Foundation (Aase og Ejnar Danielsens Fond), The Magnus Bergvall Foundation (Magnus Bergvalls Stiftelse), the Else and Mogens Wedell-Wedellborgs Foundation, The Fraenkel Foundation (Eva og Henry Fraenkels Mindefond), and the University of Copenhagen.

The online version of the article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

We thank Michael Karin for providing the Mekk1ΔKD, Jnk1–/– and Jnk2–/– animals and for helpful review of the manuscript.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal