Abstract

The BCR/ABL kinase has been targeted for the treatment of chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) by imatinib mesylate. While imatinib has been extremely effective for chronic phase CML, blast crisis CML and Ph+ acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) are often resistant. In particular, mutation of the T315 residue in the bcr/abl activation loop renders cells highly resistant to imatinib and to secondgeneration kinase inhibitors such as BMS-354825 or AMN107. Adaphostin is a tyrphostin that was originally intended to inhibit the BCR/ABL kinase by competing with its peptide substrates. Recent findings have in addition implicated reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the cytotoxic mechanism of adaphostin. In view of this unique mode of action, we examined the effects of adaphostin on numerous imatinib-resistant leukemia models, including imatinib-resistant CML and Ph+ ALL cell lines, cells harboring point mutations in BCR/ABL, and specimens from imatinib-resistant CML patients, using assays for intracellular ROS, apoptosis, and clonogenicity. Every model of imatinib resistance examined remained fully sensitive to adaphostin-induced cell death. Collectively, these data suggest that ROS generation by adaphostin overcomes even the most potent imatinib resistance in CML and Ph+ ALL. (Blood. 2006;107: 2501-2506)

Introduction

The success of imatinib mesylate in the treatment of chronic phase chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) has been a landmark event in experimental therapeutics.1 In addition to the clinical gains made with imatinib, the ability of this drug to halt BCR/ABL-initiated kinase signaling has afforded valuable insight into the biology of Ph+ leukemia cells. However, while imatinib mesylate is effective in treating chronic phase disease, its efficacy in blast crisis CML and Ph+ acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) has been less impressive.2 In these settings, resistance develops rapidly and treatment options are limited. Recently, several second-generation compounds that target ABL more potently or target ABL and SRC kinases dually have been tested in phase 1 trials. Although preliminary results indicate that the agents show promise in some resistant patients, the T315I mutation of bcr/abl remains resistant to the second-generation drugs, including BMS 3548253 and AMN107.4

Resistance to imatinib has been modeled in cell lines extensively with disparate findings. In K562, Mo7e, HL-60, and other Ph+ cell lines treated with increasing doses of imatinib over time, a number of changes that contribute to imatinib resistance have been identified, including increased Lyn activation,5 external binding by alpha-1 glycoprotein,6 increased BCR/ABL protein expression,7 BCR/ABL gene amplification,8 and BCR/ABL gene mutations.9 In patients demonstrating imatinib resistance in the clinic, BCR/ABL point mutations are a predominant mechanism of resistance.9 Seventeen mutations have been described in clinical isolates, and the degree of imatinib resistance is directly related to the site of the mutation.10 Sixty percent of BCR/ABL-positive leukemics who relapse after imatinib therapy possess mutations in amino acids 315, 253, 255, and 351.9 Mutations that interfere with drug binding appear to confer a more potent resistance that cannot be overcome by imatinib dose escalation, combinations of imatinib with decitabine or arsenic,11 or second-generation inhibitors such as BMS-3548253 or AMN107.4 The T315 residue on c-ABL is thought to act as a gatekeeper to drugs that bind the adenosine triphosphate (ATP) binding region of c-abl.12 Thus, to overcome this most potent form of resistance, it follows that an agent with a different binding site and/or mode of action will be required. To this end, Gumireddy et al have recently reported that a BCR/ABL substrate-specific inhibitor is effective in cell lines carrying the T315I mutation and in mice reconstituted with those cells.13 However, no imatinibresistant clinical specimens were tested in that study.

Adaphostin is a tyrphostin kinase inhibitor originally developed to compete with respect to substrate rather than with respect to ATP for BCR/ABL, thus fulfilling the criteria above.14,15 Colony formation assays performed using myeloid progenitors from healthy donors versus CML patients demonstrated selectivity of adaphostin for CML progenitors.16 A number of subsequent studies have revealed that this agent induces apoptosis in a variety of leukemic leukocytes,17 including primary chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) cells18,19 and AML cells, suggesting that the cytotoxicity of adaphostin does not result solely from BCR/ABL kinase inhibition. Instead, adaphostin induces a relatively rapid rise in intracellular ROS in both BCR/ABL-positive and -negative cells. Prevention of this oxidant production by N-acetylcysteine (NAC), Tiron, or Trolox17,18 abrogates the DNA damage-induced apoptosis that ensues. In addition, in BCR/ABL-containing cells, adaphostin induces down-regulation of BCR/ABL protein14,16 that is not prevented by antioxidants, indicating that the effect on BCR/ABL precedes or parallels the generation of ROS.18

While adaphostin, which is currently undergoing preclinical evaluation at the National Cancer Institute, is an attractive agent for possible development in imatinib-resistant CML, the effects of adaphostin on cells carrying mutant BCR/ABL have remained untested. In the current study, we show that adaphostin induces ROS-dependent apoptosis, inhibits colony growth, and degrades BCR/ABL protein levels in several models of imatinib resistance, including cells carrying the T315I mutation of BCR/ABL.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and antibodies

Adaphostin (formerly known as NSC680410) was kindly provided by Dr Robert Schultz, Developmental Therapeutics Program, National Cancer Institute (Bethesda, MD). Imatinib mesylate was kindly provided by Elizabeth Buchdunger, PhD, Novartis Pharmaceuticals (Basel, Switzerland). Cytosine-1-β-D-arabinofuranoside (Ara-C), NAC, propidium iodide (PI), Triton X-100, puromycin, and hydroxyurea were purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO). Murine interleukin-3 (IL-3) was purchased from PeproTech (Rocky Hill, NJ). Dyes for detection of intracellular peroxide (5-chloromethyl-2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate [CM-H2DCFDA]) and superoxide (dihydroethidium [H2E]) were purchased from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR).

Antibody recognizing c-ABL was purchased from Oncogene Research (Cambridge, MA), and an antiserum recognizing actin was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA).

Cell lines

K562 cells (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) were grown in RPMI 1640 containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 100 U/mL penicillin G, 100 mg/mL streptomycin, and 2 mM glutamine (medium A). BaF3 cells retrovirally transduced with the empty vector, wild-type p210 BCR/ABL, or indicated mutant constructs were generated as described.20 Since BCR/ABL confers growth factor independence, IL-3-supplemented medium A was required only for the empty vector BaF3 transductants. Z-33, Z-181, and Z-119 cells were originally derived from 3 Ph+ ALL patients.21,22 SUP-B15 cells were acquired from ATCC and cultured in Iscove modified Dulbecco medium with 20% fetal bovine serum, penicillin, streptomycin, and glutamine.

Imatinib-resistant Z-33 cells were generated by exposure to increasing concentrations of imatinib beginning with 1 μM. After cells were 90% viable (as measured by trypan blue and propidium iodide), the imatinib dose of coculture was escalated to 2 μM, then to 4 μM. This process took 3 months (approximately one month per dose level). Viable cells from this process were assessed for resistance to imatinib by measuring apoptosis induction after exposure to 5 μM, 10 μM, and 20 μM imatinib for 96 hours and indicated that Z-33R cells were roughly 3-fold resistant to imatinib as compared with parental Z-33 lines. Z-33R cells were then maintained in the presence of 4 μm imatinib for subsequent experiments.

Isolation of cellular fractions from clinical specimens

After informed consent was obtained under the aegis of protocols reviewed by the institutional review boards of M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, Mayo Clinic, Johns Hopkins, and Moffitt Cancer Center, mononuclear cells were isolated from peripheral blood or bone marrow of resistant CML (as determined by progression during imatinib treatment) using Ficoll-Hypaque gradients as described.18 Cells were washed with RPMI 1640 and subjected to various assays.

Quantitation of DNA fragmentation

Quantification of apoptosis by PI staining and fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis was performed as described previously.18 Following incubation with various agents in vitro, cells were pelleted by centrifugation and resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 50 μg/mL PI, 0.1% Triton X-100, and 0.1% sodium citrate. Samples were vortexed before FACS analysis (FL-3 channel) on a Becton Dickinson (Franklin Lakes, NJ) FACSCalibur. Data were analyzed using CellQuest Software.

Measurement of intracellular ROS

The cell-permeable dye CM-H2DCFDA (Molecular Probes) was used to assay intracellular ROS levels. This dye diffuses into cells and is trapped inside the cell by de-esterification. After reaction with peroxides, the fluorescent product 5-chloromethyl-2′-7′-dichlorofluorescein (DCF) is formed. Cells were collected by centrifugation after exposure to adaphostin, imatinib, or diluent for the indicated time and resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 10 μM CM-H2DCF-DA. Samples were incubated for 30 minutes in the dark at 37°C, washed with PBS to remove unreacted dye, read on the FL-1 channel of a Becton Dickinson FACSCalibur, and analyzed using CellQuest Software.

Clonogenic growth assays

After 24 hours of exposure to adaphostin or diluent, samples were washed, diluted with Methocult methylcellulose medium (StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada), plated in gridded 35-mm culture dishes, and incubated for 14 days at 37°C with 5% CO2. Colonies were identified and counted as previously described.18,23

Detection of BCR/ABL down-regulation

BCR/ABL down-regulation was detected by Western blotting using an anti-c-ABL antibody. After treatment with drug or diluent as indicated in the figure legends, cells were sedimented at 200g for 10 minutes, washed once with ice-cold RPMI 1640 medium containing 10 mM HEPES (N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N'-2-ethanesulfonic acid; pH 7.4 at 4°C), solubilized in buffered 6 M guanidine hydrochloride under reducing conditions, and prepared for electrophoresis as previously described.18 Aliquots containing 50 μg protein (determined by the bicinchoninic acid method) were separated on sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels containing 5% to 15% acrylamide gradients, electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose and probed with antibody.

Results

Adaphostin elevates intracellular peroxide and induces cytotoxicity in BaF3 cells transduced with imatinib-resistant bcr/abl

In addition to its effects on BCR/ABL kinase,14 adaphostin recently was shown to cause increased levels of ROS prior to induction of cell death in K562, ML-1, U937, and Jurkat leukemia cell lines17,18 and a variety of leukemia patient specimens, including CML and CLL.18,19 The present studies were performed to determine whether adaphostin also would produce oxidative stress and cytotoxicity in imatinib-tolerant Ph+ lines and imatinib-resistant Ph+ leukemia samples.

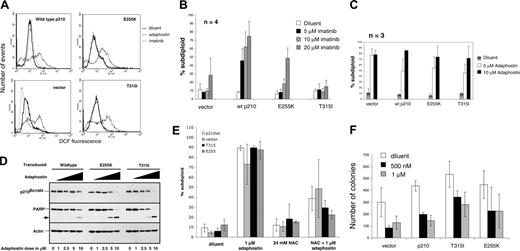

Murine cytokine-dependent BaF3 cells transduced with empty retroviral vector, wild-type BCR/ABL, BCR/ABL E255K, or BCR/ABL T315I previously have been used to evaluate the biological properties of various patient-derived BCR/ABL mutants.11,20 When these cells were treated with adaphostin and stained with CM-H2DCFDA, an agent that is trapped in cells by deesterification, and then oxidized to the fluorescent dye DCF by intracellular peroxides, elevated ROS levels were observed in all 4 samples (Figure 1A). In particular, both BCR/ABL mutants showed an increase in DCF fluorescence after exposure to adaphostin that was indistinguishable from the increase observed in cells transduced with wild-type BCR/ABL, indicating that adaphostininduced ROS elevation is not affected by BCR/ABL mutations.

To provide a basis for evaluating the cytotoxic effects of adaphostin, these BaF3 lines were cultured in the presence of imatinib for 24 hours and assayed for DNA fragmentation, one of the standard assays for apoptosis (Figure 1B).24,25 As established early on in the development of imatinib, BaF3 cells transduced with empty vector were relatively insensitive to doses of imatinib ranging from 1 to 20 μM. Transduction with wild-type p210BCR/ABL enhanced imatinib sensitivity, with more than 40% of the cells becoming apoptotic after exposure to imatinib doses of 5, 10, and 20 μM. In contrast, cells transduced with the BCR/ABL mutants were less sensitive to imatinib, with the T315I mutation conferring stronger resistance than the E255K mutation, as reported by others10,11 (Figure 1B).

Adaphostin elevates intracellular peroxide and induces cytotoxicity in BaF3 cells transduced with imatinib-resistant BCR/ABL. (A) BaF3 cells transduced with vector alone, wild-type p210 BCR/ABL, T315I BCR/ABL, or E255K BCR/ABL were exposed to diluent (dark solid line), 10 μM adaphostin (light solid line), or 10 μM imatinib (dotted line) for 1.5 hours. After cells were stained with CMH2DCF-DA, fluorescence was read on the FL-1 channel of a Becton Dickinson FACSCalibur. These results are representative of 3 independent experiments. (B,C) BaF3 cells transduced with vector, wild-type bcr/abl, T315I BCR/ABL, or E255K BCR/ABL were exposed to either diluent (□), 5 μM (▪), 10 μM (▨), or 20 μM (▦) imatinib (B) or to diluent, 5 μM, or 10 μM adaphostin (C). DNA fragmentation was assessed by PI staining. (D) The degradation of bcr/abl was assessed by Western blotting in BaF3 cells overexpressing wild-type p210BCR/ABL, T315I BCR/ABL, and E255K BCR/ABL after 8 hours of exposure to 0, 1, 2.5, 5, or 10 μM adaphostin. The same membrane was probed with antibody to the caspase substrate PARP31 as a marker of cell death and with antibody to actin as a loading control. (E) BaF3 cells overexpressing vector only (□), wild-type p210BCR/ABL (▦), T315I BCR/ABL (▪), or E255K BCR/ABL (▨) were exposed for 24 hours to diluent, 24 mM NAC, 1 μM adaphostin, or 24 mM NAC and 1 μM adaphostin together. DNA fragmentation was assessed by PI staining as described in “Materials and methods.” Decrease in adaphostin-induced cell death by NAC was statistically significant in wild-type p210BCR/ABL (P = .002), T315I BCR/ABL (P < .001), or E255K BCR/ABL (P < .001) as calculated by the Student 2-tailed paired t test. (F) BaF3 cells transduced with vector alone, wild-type p210, T315I bcr/abl, or E255K bcr/abl were exposed to either diluent, 500 nM, or 1 μM adaphostin for 24 hours. Cells were then resuspended in Methocult media and allowed to form colonies for 7 days. Error bars in panels B, C, E, and F indicate standard deviation (SD).

Adaphostin elevates intracellular peroxide and induces cytotoxicity in BaF3 cells transduced with imatinib-resistant BCR/ABL. (A) BaF3 cells transduced with vector alone, wild-type p210 BCR/ABL, T315I BCR/ABL, or E255K BCR/ABL were exposed to diluent (dark solid line), 10 μM adaphostin (light solid line), or 10 μM imatinib (dotted line) for 1.5 hours. After cells were stained with CMH2DCF-DA, fluorescence was read on the FL-1 channel of a Becton Dickinson FACSCalibur. These results are representative of 3 independent experiments. (B,C) BaF3 cells transduced with vector, wild-type bcr/abl, T315I BCR/ABL, or E255K BCR/ABL were exposed to either diluent (□), 5 μM (▪), 10 μM (▨), or 20 μM (▦) imatinib (B) or to diluent, 5 μM, or 10 μM adaphostin (C). DNA fragmentation was assessed by PI staining. (D) The degradation of bcr/abl was assessed by Western blotting in BaF3 cells overexpressing wild-type p210BCR/ABL, T315I BCR/ABL, and E255K BCR/ABL after 8 hours of exposure to 0, 1, 2.5, 5, or 10 μM adaphostin. The same membrane was probed with antibody to the caspase substrate PARP31 as a marker of cell death and with antibody to actin as a loading control. (E) BaF3 cells overexpressing vector only (□), wild-type p210BCR/ABL (▦), T315I BCR/ABL (▪), or E255K BCR/ABL (▨) were exposed for 24 hours to diluent, 24 mM NAC, 1 μM adaphostin, or 24 mM NAC and 1 μM adaphostin together. DNA fragmentation was assessed by PI staining as described in “Materials and methods.” Decrease in adaphostin-induced cell death by NAC was statistically significant in wild-type p210BCR/ABL (P = .002), T315I BCR/ABL (P < .001), or E255K BCR/ABL (P < .001) as calculated by the Student 2-tailed paired t test. (F) BaF3 cells transduced with vector alone, wild-type p210, T315I bcr/abl, or E255K bcr/abl were exposed to either diluent, 500 nM, or 1 μM adaphostin for 24 hours. Cells were then resuspended in Methocult media and allowed to form colonies for 7 days. Error bars in panels B, C, E, and F indicate standard deviation (SD).

In contrast to imatinib, adaphostin induced apoptosis in all of these cell lines equivalently (Figure 1C). Down-regulation of BCR/ABL and cleavage of the caspase substrate poly-ADP-ribose polymerase (PARP) also was seen in BaF3 cells overexpressing mutant bcr/abl after adaphostin exposure (Figure 1D), providing further evidence that these BCR/ABL mutations have little effect on adaphostin action. As was the case with K562 and Jurkat cells,17,18 a 15-minute pretreatment with the antioxidant NAC markedly diminished the cytotoxicity of adaphostin in all of the BaF cell lines (Figure 1E), suggesting that the elevated ROS levels detected in Figure 1A play a critical role in the cytotoxicity of adaphostin in these cells.

In view of recent studies criticizing the use of apoptosis as an end point in determining the potential effects of therapeutic agents,26,27 we also examined the effects of adaphostin on the ability of these cells to proliferate and form colonies in soft agar. Adaphostin inhibited the colony-forming ability of all of the BaF3 derivatives (Figure 1F), with the cells expressing mutant BCR/ABL being only slightly less sensitive than those expressing wild-type p210BCR/ABL.

Adaphostin induces intracellular peroxide production in imatinib-resistant human Ph+ cell lines

To further explore the action of adaphostin in imatinib-resistant cells, we examined the action of adaphostin in a variety of human Ph+ cell lines selected for imatinib resistance.

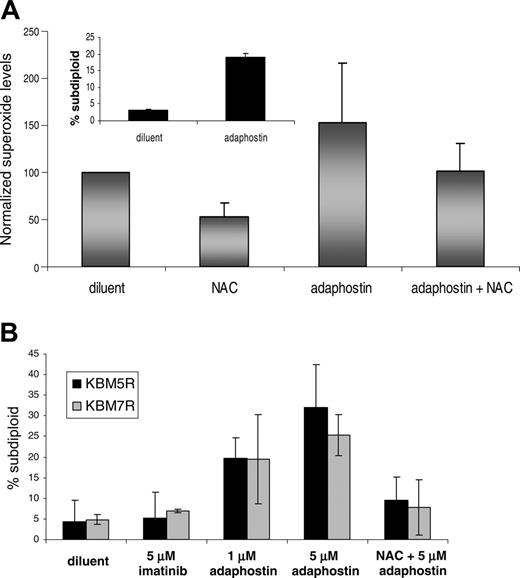

KBM5 and KBM7 cells, which are derived from CML patients,28 display elevated ROS and DNA fragmentation after exposure to adaphostin (Figure 2A and data not shown). For further studies, imatinib-resistant derivatives of these lines were developed by exposing parental cells to increasing doses of imatinib as previously described.29 KBM5R cells contain a point mutation in the BCR/ABL gene, whereas KBM7R cells have amplification of the BCR/ABL gene and increased expression of p210BCR/ABL protein. Despite their resistance to imatinib, these cells remained sensitive to adaphostin-induced apoptosis (Figure 2B). As was the case with the BaF3 lines, preincubation with NAC diminished apoptosis in these resistant cells (Figure 2B) in a statistically significant manner (P = .04 for KBM5R and P = .03 for KBM7R).

Effects of adaphostin on imatinib-resistant human Ph+ CML cell lines.(A) The CML-derived cell line KBM5 was treated for 30 minutes with diluent, 24 mM NAC, or 5 μM adaphostin in the absence or presence of a 15-minute pretreatment with NAC. Superoxide levels were assessed by staining cells with 10 μM dihydroethidium for 30 minutes and then analyzing FL3 fluorescence by flow cytometry on a Becton Dickinson FACSCalibur. DNA fragmentation by PI staining and subsequent FACS analysis on the FL-3 channel was also assessed in KBM5 cells after a 24-hour exposure to diluent or 2.5 μM adaphostin (inset). (B) Resistant versions of the KBM5 and KBM7 lines were developed as previously described.29 KBM5R (▪) and KBM7R (▦) cells were exposed for 24 hours to 5 μM imatinib mesylate, 1 μM adaphostin alone, or 1 μM adaphostin after a 15-minute pretreatment with 24 mM NAC. DNA fragmentation was assessed by PI staining and subsequent FACS analysis as described in panel A. Reduction in subdiploid cells by NAC in combination with adaphostin was statistically significant with P = .04 for KBM5R and P = .03 for KBM7R as calculated by the Student t test. Error bars indicate SD.

Effects of adaphostin on imatinib-resistant human Ph+ CML cell lines.(A) The CML-derived cell line KBM5 was treated for 30 minutes with diluent, 24 mM NAC, or 5 μM adaphostin in the absence or presence of a 15-minute pretreatment with NAC. Superoxide levels were assessed by staining cells with 10 μM dihydroethidium for 30 minutes and then analyzing FL3 fluorescence by flow cytometry on a Becton Dickinson FACSCalibur. DNA fragmentation by PI staining and subsequent FACS analysis on the FL-3 channel was also assessed in KBM5 cells after a 24-hour exposure to diluent or 2.5 μM adaphostin (inset). (B) Resistant versions of the KBM5 and KBM7 lines were developed as previously described.29 KBM5R (▪) and KBM7R (▦) cells were exposed for 24 hours to 5 μM imatinib mesylate, 1 μM adaphostin alone, or 1 μM adaphostin after a 15-minute pretreatment with 24 mM NAC. DNA fragmentation was assessed by PI staining and subsequent FACS analysis as described in panel A. Reduction in subdiploid cells by NAC in combination with adaphostin was statistically significant with P = .04 for KBM5R and P = .03 for KBM7R as calculated by the Student t test. Error bars indicate SD.

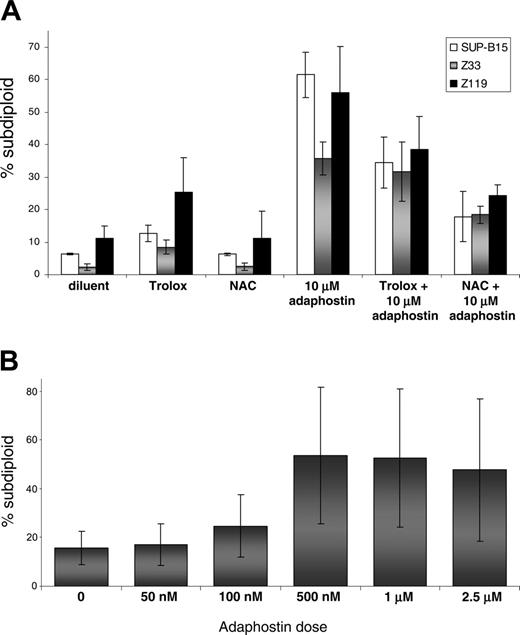

Because the effects of adaphostin had not been previously examined in Ph+ human ALL cells, we also examined the action of this agent in 2 cell lines derived from Ph+ adult ALL patients (Z33 and Z119) as well as one derived from a pediatric Ph+ ALL patient (SUP-B15). All 3 lines underwent apoptosis after exposure to 10 μM adaphostin (Figure 3A). Once again, preincubation with 24 mM NAC or 10 mM Trolox was partially protective (Figure 3A), highlighting the critical role of elevated ROS in the cytotoxicity of adaphostin. In further experiments, Z33 cells were selected for resistance to increasing concentrations of imatinib as described in “Materials and methods.” Despite resistance to imatinib, these cells displayed enhanced sensitivity to adaphostin: 500 nM adaphostin induced apoptosis in 40% of Z33R cells (Figure 3B), whereas 10 μM adaphostin was required to induce a similar degree of apoptosis in parental Z33 cells (Figure 3A and data not shown). These observations raise the possibility that some imatinibresistant cells might actually be hypersensitive to adaphostin.

Adaphostin effects on imatinib-resistant Ph+ human leukemia samples

In additional experiments, we examined the action of adaphostin on Ph+ leukemia specimens from patients who progressed while taking imatinib. These studies examined not only the ability of adaphostin to elevate ROS and induce DNA fragmentation, but also the long-term effects assessed by colony-forming assays.

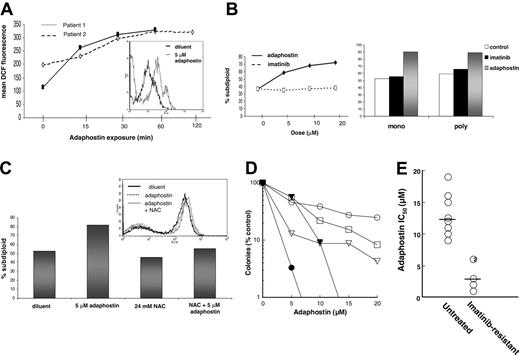

Consistent with our previous report that adaphostin causes elevated ROS in clinical CML specimens,18 cells isolated from imatinib-resistant CML patients also showed an increase in ROS levels after adaphostin exposure (Figure 4A). Time-course studies demonstrated that the increase in ROS was detectable within 15 minutes and was comparable to that seen in cell lines (Figure 4A, inset) after 1 hour of exposure.

In further experiments, the ability of adaphostin to induce apoptosis in Ph+ clinical isolates was examined (Figure 4B,C). Spontaneous apoptosis was high in both CML isolates examined in this way (Figure 4B) and may be attributed to ex vivo culture conditions or to clinical management of these patients with hydroxyurea at the time of blood draw. Nonetheless, when CML mononuclear or polymorphonuclear cells were exposed to either increasing or a fixed dose of adaphostin, an increase in DNA fragmentation was seen (Figure 4B). Adaphostin similarly induced DNA fragmentation in a sample of p190BCR/ABL-expressing ALL (Figure 4C). As was the case with the Ph+ ALL cell lines, the induction of apoptosis was inhibited by NAC, although the rate of spontaneous apoptosis in the clinical sample was again high.

Effects of adaphostin on imatinib-resistant human Ph+ ALL cell lines. (A) The Ph+ ALL cell lines SUP-B15 (□), Z33 (▦), or Z119 (▪) were pretreated with either 24 mM NAC or 10 mM Trolox for 15 minutes and then exposed to 10 μM adaphostin as indicated. DNA fragmentation was assessed by PI staining and flow cytometry. (B) Z33R cells were generated as described in “Materials and methods” and exposed to indicated doses of adaphostin for 24 hours before DNA fragmentation was assessed as described in the legend to Figure 2. The increases in DNA fragmentation were statistically significant at 100 nM, 500 nM, 1 μM, and 2.5 μM doses of adaphostin according to the Student t test, with P values of .017, .016, .016, and .053, respectively. Error bars indicate SD.

Effects of adaphostin on imatinib-resistant human Ph+ ALL cell lines. (A) The Ph+ ALL cell lines SUP-B15 (□), Z33 (▦), or Z119 (▪) were pretreated with either 24 mM NAC or 10 mM Trolox for 15 minutes and then exposed to 10 μM adaphostin as indicated. DNA fragmentation was assessed by PI staining and flow cytometry. (B) Z33R cells were generated as described in “Materials and methods” and exposed to indicated doses of adaphostin for 24 hours before DNA fragmentation was assessed as described in the legend to Figure 2. The increases in DNA fragmentation were statistically significant at 100 nM, 500 nM, 1 μM, and 2.5 μM doses of adaphostin according to the Student t test, with P values of .017, .016, .016, and .053, respectively. Error bars indicate SD.

To provide a more quantitative assessment of the effects of adaphostin on imatinib-resistant CML isolates, colony-forming assays were performed. After 24 hours of exposure to 5 to 20 μM adaphostin, cells were washed and plated in methylcellulose containing a mixture of human cytokines. All 5 specimens examined in this assay displayed adaphostin sensitivity, although there was some variability in response (Figure 4D). Comparison to a series of samples obtained from previously untreated CML patients (Figure 4E) suggested that the imatinib-resistant isolates were actually more sensitive to adaphostin than the imatinib-naive samples (mean IC50 3.6 ± 2.3 μM vs 13.1 ± 3.4, mean ± SD, P = .003 by Mann-Whitney U test).

Effects of adaphostin on imatinib-resistant Ph+ human leukemia samples. (A) Mononuclear cells from the peripheral blood of 2 CML patients were isolated, incubated with 5 μM adaphostin for the indicated times, stained with CMH2DCF-DA, and subjected to flow cytometry. Mean fluorescence over the time course is depicted graphically, whereas the inset histogram shows the increased DCF fluorescence after 1 hour of adaphostin exposure. BCR/ABL mutation status was not known for patient 1, but patient 2 was shown to have a previously unreported novel mutation. (B) After mononuclear cells from patient A (left panel) were incubated with increasing doses of imatinib mesylate or adaphostin for 24 hours, DNA fragmentation was assessed. Right panel depicts DNA fragmentation in mononuclear and polymorphonuclear cells from patient B exposed to either diluent (□), 10 μM imatinib (▪), or 10 μM adaphostin (▦) for 24 hours. (C) Isolated mononuclear cells from a pediatric Ph+ ALL patient were exposed to diluent (dark solid histogram), 5 μM adaphostin (dotted histogram), or 24 mM NAC and adaphostin (light solid histogram) for 1.5 hours, stained with CMH2DCF-DA, and read on a FACSCalibur to quantitate intracellular peroxide levels (inset histogram). DNA fragmentation was assessed by PI staining from the same experiment after a 24-hour exposure to indicated treatments and is shown graphically. (D) Mononuclear cells isolated from the peripheral blood of CML patients who progressed on imatinib were exposed for 24 hours to diluent or the indicated concentrations of adaphostin, plated in Methocult methylcellulose as previously described,23 and scored for myeloid colony formation (CFU-G and CFU-GM) 14 days later according to the instructions of the supplier. (E) The concentration that inhibits colony formation (IC50) was read from each curve in panel D and compared with IC50 values determined in samples from untreated CML patients examined using the same assay over the same time period. Horizontal bars indicate median values. Number in circle represents multiple samples with indistinguishable IC50 values.

Effects of adaphostin on imatinib-resistant Ph+ human leukemia samples. (A) Mononuclear cells from the peripheral blood of 2 CML patients were isolated, incubated with 5 μM adaphostin for the indicated times, stained with CMH2DCF-DA, and subjected to flow cytometry. Mean fluorescence over the time course is depicted graphically, whereas the inset histogram shows the increased DCF fluorescence after 1 hour of adaphostin exposure. BCR/ABL mutation status was not known for patient 1, but patient 2 was shown to have a previously unreported novel mutation. (B) After mononuclear cells from patient A (left panel) were incubated with increasing doses of imatinib mesylate or adaphostin for 24 hours, DNA fragmentation was assessed. Right panel depicts DNA fragmentation in mononuclear and polymorphonuclear cells from patient B exposed to either diluent (□), 10 μM imatinib (▪), or 10 μM adaphostin (▦) for 24 hours. (C) Isolated mononuclear cells from a pediatric Ph+ ALL patient were exposed to diluent (dark solid histogram), 5 μM adaphostin (dotted histogram), or 24 mM NAC and adaphostin (light solid histogram) for 1.5 hours, stained with CMH2DCF-DA, and read on a FACSCalibur to quantitate intracellular peroxide levels (inset histogram). DNA fragmentation was assessed by PI staining from the same experiment after a 24-hour exposure to indicated treatments and is shown graphically. (D) Mononuclear cells isolated from the peripheral blood of CML patients who progressed on imatinib were exposed for 24 hours to diluent or the indicated concentrations of adaphostin, plated in Methocult methylcellulose as previously described,23 and scored for myeloid colony formation (CFU-G and CFU-GM) 14 days later according to the instructions of the supplier. (E) The concentration that inhibits colony formation (IC50) was read from each curve in panel D and compared with IC50 values determined in samples from untreated CML patients examined using the same assay over the same time period. Horizontal bars indicate median values. Number in circle represents multiple samples with indistinguishable IC50 values.

Discussion

In the current study, we show that adaphostin causes increased ROS levels and cytotoxicity in a variety of imatinib-resistant leukemia cells. These effects of adaphostin are observed in cell lines transduced with mutant p210BCR/ABL (Figure 1), cell lines that became resistant to imatinib as a consequence of drug selection (Figures 2 and 3), and clinical samples from patients who progressed while receiving imatinib (Figure 4). Importantly, while these studies demonstrate that imatinib-resistant cells retain adaphostin sensitivity, our previous studies have demonstrated that normal bone marrow16 and normal lymphocytes19 are resistant to adaphostin.

These findings are potentially valuable in light of the clinical results observed with second-generation c-ABL inhibitors in imatinib-resistant Ph+ leukemias. While BMS354825 and AMN107 have been successful in the treatment of leukemias bearing the majority of imatinib resistant BCR/ABL mutations, the T315I mutation remains resistant to both of these second generation inhibitors.3,7 Given that the T315I mutation is the most common bcr/abl mutation seen to date, the ability of adaphostin to overcome T315I-mediated imatinib resistance provides additional impetus for the further preclinical and possible clinical study of this unique tyrphostin.

In addition to its ROS-dependent actions, adaphostin also induces down-regulation of wild-type and mutant BCR/ABL protein (Figure 1D). The mechanism by which BCR/ABL is down-regulated by adaphostin remains unclear but is unchanged by antioxidants, proteasome inhibition, and inhibition of translation.18

In all of the imatinib-resistant leukemia cells examined, treatment with antioxidants diminished the cytotoxicity of adaphostin (Figures 1E, 2B, 3A, 4C), providing further support for the view that oxidative stress contributes to the cytotoxicity of adaphostin. Consistent with this view, adaphostin-induced ROS increases were easily detectable in CML cell lines (Figures 1A, 2A) as well as CML clinical samples (Figure 4A). Previous work has demonstrated that p210BCR/ABL overexpression itself also generates increased oxidative stress in a number of cellular backgrounds,30 not only providing a potential explanation for sensitivity of CML cells to the added oxidative stress of adaphostin,18 but also raising the possibility that adaphostin-induced elevations in ROS levels might reflect an impaired ability of CML cells to detoxify ROS. Interestingly, however, ROS elevations were much smaller and more difficult to detect in Ph+ ALL cell lines (not shown) and Ph+ ALL samples (Figure 4C). While the ability of NAC to protect those ALL cell lines (Figure 3A) and clinical samples (Figure 4C) provides evidence for the importance of ROS in the action of adaphostin, further studies are required to determine whether the difference between ROS levels in p210BCR/ABL-versus p190BCR/ABL-positive cells is due to differential clearing of ROS by antioxidant enzymes or some other process.

Comparison of the results of clonogenic assays performed on samples from CML patients who progressed on imatinib (Figure 4D) and samples from untreated CML patients (Figure 4E) raises the possibility that imatinib-resistant cells might be hypersensitive to adaphostin. These results mirror the effects observed in Z33R cells, which were selected from Z33 cells by adaphostin treatment (Figure 3). In view of the small number of samples examined, however, we believe that further study of imatinib-resistant clinical isolates is required to validate this conclusion. Nonetheless, the present results argue persuasively that imatinib-resistant samples will not be cross-resistant to adaphostin.

In summary, results of the present study indicate that key features of adaphostin action, including the ability to induce antioxidant-suppressible cytotoxicity, are retained in Ph+ cells that have become resistant to imatinib mesylate. In view of studies showing that imatinib resistance is a looming problem,9 the unique action of adaphostin even in cells bearing the T315I mutation suggests that this agent might be worthy of further preclinical and possibly clinical study.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, November 15, 2005; DOI 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2966.

Supported in part by the Leukemia Specialized Program of Research Excellence (SPORE) Career Development Award to M.D. Anderson from the National Cancer Institute (J.C.) and by R01 CA85972 (S.H.K.).

An Inside Blood analysis of this article appears at the front of this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal