Abstract

Targeted disruption of the Runx1/ AML1 gene in mice has demonstrated that it is required for the emergence of definitive hematopoietic cells but that it is not essential for the formation of primitive erythrocytes. These findings led to the conclusion that Runx1 is a stage-specific transcription factor acting only during definitive hematopoiesis. However, the zebrafish and Xenopus homologs of Runx1 have been shown to play roles in primitive hematopoiesis, suggesting that mouse Runx1 might also be involved in the development of primitive lineages. In this study, we show that primitive erythrocytes in Runx1−/− mice display abnormal morphology and reduced expression of Ter119, Erythroid Kruppel-like factor (EKLF, KLF1), and GATA-1. These results suggest that mouse Runx1 plays a role in the development of both primitive and definitive hematopoietic cells.

Introduction

Recent studies have revealed that the process of hematopoiesis is largely conserved in vertebrates. During development, similar sequential waves of primitive and definitive hematopoiesis are observed in mammals, fish, and amphibians.1-3 In the mouse embryo, primitive erythrocytes first appear in the yolk sac blood island at embryonic day (E) 7 and lead to the production of nucleated erythrocytes.4,5 These erythrocytes (erythroblasts) start to circulate at 4 to 6 somite pairs (E8.25)6 and are necessary for the survival of the embryo before establishment of definitive erythropoiesis, which is initiated in the fetal liver around E12 and is characterized by the production of enucleated erythrocytes.4 The equivalent site of blood island in zebrafish embryo is known as the intermediate cell mass, which is located in the posterior part of embryo and provides the primitive erythrocytes.3

Runx1/AML1 encodes the DNA-binding subunit of the Runt domain transcription factor,7 which plays crucial roles in processes of organ and tumor development, such as hematopoiesis, neural development, and leukemogenesis.8,9 Runx1-deficient mice die around E12.5 because of severe hemorrhaging in the central nervous system and a complete lack of definitive hematopoietic cells, including the aortic hematopoietic clusters, which are thought to comprise hematopoietic stem cells.10-14 The specification of definitive hematopoietic stem cells by Runx1 has also been observed in the zebrafish embryo. Depletion of zebrafish Runx1 by antisense morpholino oligonucleotides leads to a severe defect in definitive hematopoietic development in the dorsal aorta.15,16

Although Runx1 has been implicated in primitive hematopoiesis in zebrafish and Xenopus embryos,15,17 its function during primitive erythropoiesis in the mouse has not been described despite its reported expression in this lineage.13,18 In this study, we examined primitive erythrocytes in Runx1−/− mice and observed aberrant morphology and reduced expression of Ter119, Erythroid Kruppel-like factor (EKLF, KLF1), and GATA-1 in these cells.

Methods

Mice

Runx1-deficient mice (C57BL/6) have been previously described.12 For visualizing GATA-1 expression in primitive erythrocytes, IE3.9-LacZ transgenic mice carrying a 3.9 kb GATA-1 promoter-LacZ reporter gene (C57BL/6 × DBA/2 mixed background)19 were crossed with Runx1-deficient mice. For the transgenic complementary rescue experiment, G1-HRD-Runx1 transgenic mice carrying a 8.0 kb GATA-1 hematopoietic regulatory domain -Runx1 transgene (C57BL/6 × DBA/2 mixed background)20 were crossed with Runx1-deficient mice.

Benzidine and LacZ staining

Embryos were fixed at 4°C for 2 hours in 1% formaldehyde, 0.2% glutaraldehyde, and 0.02% Nonidet P-40 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). For LacZ-staining, embryos were incubated at 37°C overnight in 2 mM MgCl2, 5 mM K3Fe(CN)6, 5 mM K4Fe(CN)6, and 1 mg/mL X-Gal in PBS. For benzidine staining, embryos were incubated for 15 minutes in 14% benzidine base (3% benzidine in 90% glacial acetic acid/10% H2O) and 14% H2O2 in H2O.

Scanning electron microscopy

Peripheral blood cells from E12.5 embryos were fixed with 1.6% glutaraldehyde, postfixed in 1% osmium tetroxide. After dehydration with a graded series of alcohol solutions, the samples were freeze-dried, coated with a layer of gold, and observed under a scanning electron microscope (JSM 6320F; JEOL, Tokyo, Japan).

In vitro hematopoietic progenitor assay

A colony assay for the development of primitive erythroid lineages was performed as described.21 Briefly, E8.5 whole embryos from each genotypes were treated with trypsin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for 5 minutes at 37°C and washed with PBS containing 5% fetal bovine serum. The cells were plated in 1% methylcellulose/Iscove modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% plasma-derived serum, 5% protein-free hybridoma medium (Invitrogen), 12.5 mg/mL ascorbic acid (Wako Bioproducts, Richmond, VA), 2 mM l-glutamine, 10 mg/mL transferrin (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany), 39 ng/mL MTG (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO), 5 ng/mL stem-cell factor (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), and 50 ng/mL erythropoietin. After 3 days of culture, primitive erythroid colonies were counted.

Cell preparation and staining

Embryos were treated with Dispase II (Roche Diagnostics) and cell dissociation buffer containing EDTA/EGTA (Invitrogen) to make single cell suspensions. Nonspecific binding was blocked by incubation in 5% mouse serum for 15 minutes, followed by incubation with Oregon Green-conjugated anti-Ter119 antibody (a generous gift from Dr S.-I. Nishikawa, Riken Center for Developmental Biology, Kobe, Japan) for 30 minutes. β-Galactosidase activity was detected using FluoReporter lacZ Flow Cytometry Kit (Invitrogen). Briefly, dissociated cells were resuspended in 20 μL PBS with 5% fetal calf serum before loading with 20 μL of 2 mM fluorescein di-β -D-galactopyranoside (FDG) and followed by incubation at 37°C for 75 seconds. The uptake was stopped by the addition of 500 μL ice-cold PBS with 5% fetal calf serum. Cells were analyzed with FACScan or FACS Vantage (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) values were calculated using CellQuest software (BD Biosciences).

Real-time reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction

RNA was purified from E11.5 peripheral blood cells using the RNeasy Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and reverse-transcribed by SuperScriptIII (Invitrogen). Real-time polymerase chain reactions (PCR) using Taqman probes for GATA-1 and GAPDH or with SYBR green for EKLF and SCL were performed in an ABI PRISM 7700 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The forward and reverse primers used for PCR were as follows: EKLF, 5′-AGACTGTCTTACCCTCCATCAG-3′ and 5′-GGTCCTCCGATTTCAGACTCAC-3′; SCL, 5′-CACTAGGCAGTGGGTTCTTTG-3′ and 5′-GGTGTGAGGACCATCAGAAATCT-3′. The primers and VIC-labeled probe for GATA-1 were as follows: 5′-CAGAACCGGCCTCTCATCC-3′, 5′-TAGTGCATTGGGTGCCTGC-3′, and VIC-labeled 5′-CCC AAG AAG CGA ATG ATT GTC AGC AAA-3′.22 cDNA quantities were normalized to the amount of GAPDH cDNA, which was quantified using Rodent GAPDH Control Reagents (VIC probe; Applied Biosystems).

Gene array analysis

Total RNA from E10.5 wild-type and Runx1−/− yolk sacs was extracted using RNeasy kit, and 3 same genotype samples were mixed equally. The quality and quantity of the isolated RNA were determined using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA). As previously described,23 Cy3- or Cy5-labeled cRNA was generated by the use of the Low RNA fluorescent Linear Amplification Kit (Agilent Technologies) and hybridized to a 20K Mouse Development Microarray (Agilent Technologies). The scanning was performed with an Agilent Technologies Microarray Scanner (Agilent Technologies), and the analysis was carried out using Excel software (Microsoft, Redmond, WA). Microarray data have been deposited at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/ under accession #GSE10348.24

Results

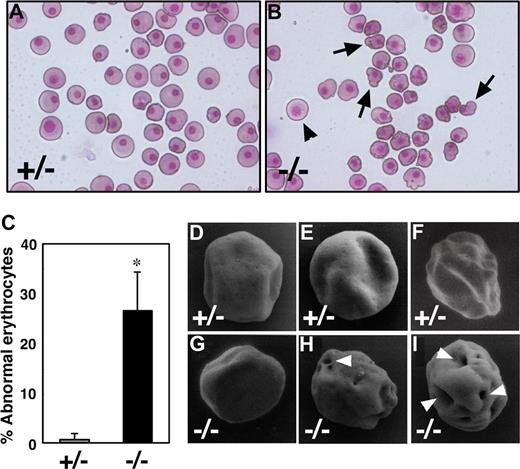

Abnormal morphology of Runx1−/− primitive erythrocytes

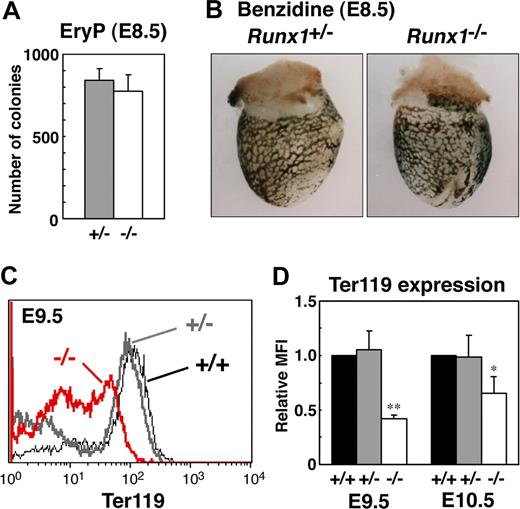

To study the role of Runx1 in primitive erythropoiesis, we used a loss-of-function strategy. As reported previously, E10.5 Runx1−/− embryos were not anemic and were indistinguishable from wild-type embryos.10-12 Runx1−/− embryos began to hemorrhage in the central nervous system around E11.5 and died around E12.5. First, to examine whether any morphologic defects exist in Runx1-deficient primitive erythrocytes, we isolated peripheral blood from live E12.5 Runx1−/− embryos. Cytospin preparation of Runx1−/− peripheral blood revealed that 27% of primitive erythrocytes displayed a deformed shape of the erythrocytes, in contrast to the smooth, round shape of erythrocytes from Runx1+/− mice (Figure 1A-C). Consistently, scanning electron microscopic analysis revealed a rough surface and characteristic hole-like structures on Runx1−/− primitive erythrocytes (9 of 20 erythrocytes, Figure 1G-I), not on Runx1+/− primitive erythrocytes (0 of 16 erythrocytes, Figure 1D-F). As reported previously,18 the number of primitive erythroid colonies derived from Runx1−/− embryos was similar to that derived from control Runx1+/− embryos, indicating that formation of primitive erythroid progenitors is normal in Runx1−/− embryos at E8.5 (Figure 2A). Benzidine staining of whole yolk sac revealed a normal number of hemoglobinized erythrocytes in Runx1−/− embryos at E8.5 (Figure 2B) and E10.5 (data not shown). Taken together, these results suggest that Runx1 is required for the terminal maturation and/or maintenance of primitive erythrocytes.

Runx1−/− primitive erythrocytes show defect in morphology. (A,B) May-Grunwald Giemsa stained cytospin preparation of peripheral blood cells at E12.5. Although normal erythrocytes ( ) can be seen in Runx1−/− embryo, 27% of them show apparent deformed shape (

) can be seen in Runx1−/− embryo, 27% of them show apparent deformed shape ( ). (C) Quantification of abnormal primitive erythrocytes in Runx1+/− (n = 3) and Runx1−/− (n = 4) embryos at E12.5. *Significance (P = .002, Student t test). (D-I) Scanning electron microscopy of primitive erythrocytes at E12.5. Shown are representative pictures of primitive erythrocytes from Runx1+/− (n = 3) and Runx1−/− (n = 3) embryos. Characteristic large holes (white arrowheads) were observed in Runx1−/− erythrocytes (9 of 20), not in Runx1+/− erythrocytes (0 of 16). This difference is statistically significant (P = .002 by Fisher exact probability test). Original magnifications: A,B, ×400; D-G, ×8000; H, ×8500; I, ×9000. A Leica (Wetzlar, Germany) DC500 CCD camera with IM50 Imaging Manager through Leica DMRXA microscope was used to capture the images using a 20×/0.50 NA objective (A,B).

). (C) Quantification of abnormal primitive erythrocytes in Runx1+/− (n = 3) and Runx1−/− (n = 4) embryos at E12.5. *Significance (P = .002, Student t test). (D-I) Scanning electron microscopy of primitive erythrocytes at E12.5. Shown are representative pictures of primitive erythrocytes from Runx1+/− (n = 3) and Runx1−/− (n = 3) embryos. Characteristic large holes (white arrowheads) were observed in Runx1−/− erythrocytes (9 of 20), not in Runx1+/− erythrocytes (0 of 16). This difference is statistically significant (P = .002 by Fisher exact probability test). Original magnifications: A,B, ×400; D-G, ×8000; H, ×8500; I, ×9000. A Leica (Wetzlar, Germany) DC500 CCD camera with IM50 Imaging Manager through Leica DMRXA microscope was used to capture the images using a 20×/0.50 NA objective (A,B).

Runx1−/− primitive erythrocytes show defect in morphology. (A,B) May-Grunwald Giemsa stained cytospin preparation of peripheral blood cells at E12.5. Although normal erythrocytes ( ) can be seen in Runx1−/− embryo, 27% of them show apparent deformed shape (

) can be seen in Runx1−/− embryo, 27% of them show apparent deformed shape ( ). (C) Quantification of abnormal primitive erythrocytes in Runx1+/− (n = 3) and Runx1−/− (n = 4) embryos at E12.5. *Significance (P = .002, Student t test). (D-I) Scanning electron microscopy of primitive erythrocytes at E12.5. Shown are representative pictures of primitive erythrocytes from Runx1+/− (n = 3) and Runx1−/− (n = 3) embryos. Characteristic large holes (white arrowheads) were observed in Runx1−/− erythrocytes (9 of 20), not in Runx1+/− erythrocytes (0 of 16). This difference is statistically significant (P = .002 by Fisher exact probability test). Original magnifications: A,B, ×400; D-G, ×8000; H, ×8500; I, ×9000. A Leica (Wetzlar, Germany) DC500 CCD camera with IM50 Imaging Manager through Leica DMRXA microscope was used to capture the images using a 20×/0.50 NA objective (A,B).

). (C) Quantification of abnormal primitive erythrocytes in Runx1+/− (n = 3) and Runx1−/− (n = 4) embryos at E12.5. *Significance (P = .002, Student t test). (D-I) Scanning electron microscopy of primitive erythrocytes at E12.5. Shown are representative pictures of primitive erythrocytes from Runx1+/− (n = 3) and Runx1−/− (n = 3) embryos. Characteristic large holes (white arrowheads) were observed in Runx1−/− erythrocytes (9 of 20), not in Runx1+/− erythrocytes (0 of 16). This difference is statistically significant (P = .002 by Fisher exact probability test). Original magnifications: A,B, ×400; D-G, ×8000; H, ×8500; I, ×9000. A Leica (Wetzlar, Germany) DC500 CCD camera with IM50 Imaging Manager through Leica DMRXA microscope was used to capture the images using a 20×/0.50 NA objective (A,B).

Analysis of primitive erythroid progenitors and differentiated cells in Runx1−/− embryo. (A) Primitive erythroid colonies from E8.5 Runx1+/− yolk sacs (n = 3) and Runx1−/− yolk sacs (n = 3). (B,C) Benzidine staining of E8.5 embryos. Hemoglobinized cells were observed inside blood vessels of yolk sac. Similar staining levels were obtained for wild-type and Runx1−/− embryos. (D) Flow cytometric analysis of E9.5 yolk sac using anti-Ter119 antibody. Black line, gray bold line, or red bold line represents Ter119 expression in Runx1+/+, Runx1+/−, or Runx1−/−, respectively. (E) Relative MFI values of Ter119 for Runx1+/+ (normalized to MFI = 1), Runx1+/−, and Runx1−/− embryos at E9.5 and E10.5. Bar graphs represents mean ratios plus or minus SD derived from Runx1+/− (n = 3 E9.5, n = 4 E10.5) and Runx1−/− (n = 2 E9.5, n = 4 E10.5) embryos. Significant differences in Runx1−/− mice from Runx1+/− mice were observed (**P = .017, *P = .039 by Student t test). Original magnifications ×16. Images in panel B were captured with a Leica MZ FLIII microscope and a Leica DC500 CCD camera with IM50 Imaging Manager, with a PLAN APO 1.0 lens (1.0×/0.125 NA).

Analysis of primitive erythroid progenitors and differentiated cells in Runx1−/− embryo. (A) Primitive erythroid colonies from E8.5 Runx1+/− yolk sacs (n = 3) and Runx1−/− yolk sacs (n = 3). (B,C) Benzidine staining of E8.5 embryos. Hemoglobinized cells were observed inside blood vessels of yolk sac. Similar staining levels were obtained for wild-type and Runx1−/− embryos. (D) Flow cytometric analysis of E9.5 yolk sac using anti-Ter119 antibody. Black line, gray bold line, or red bold line represents Ter119 expression in Runx1+/+, Runx1+/−, or Runx1−/−, respectively. (E) Relative MFI values of Ter119 for Runx1+/+ (normalized to MFI = 1), Runx1+/−, and Runx1−/− embryos at E9.5 and E10.5. Bar graphs represents mean ratios plus or minus SD derived from Runx1+/− (n = 3 E9.5, n = 4 E10.5) and Runx1−/− (n = 2 E9.5, n = 4 E10.5) embryos. Significant differences in Runx1−/− mice from Runx1+/− mice were observed (**P = .017, *P = .039 by Student t test). Original magnifications ×16. Images in panel B were captured with a Leica MZ FLIII microscope and a Leica DC500 CCD camera with IM50 Imaging Manager, with a PLAN APO 1.0 lens (1.0×/0.125 NA).

Reduced expression of Ter119 in Runx1−/− primitive erythrocytes

To further characterize Runx1−/− primitive erythrocytes, we analyzed the expression of the erythroid surface marker, Ter119, by fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS). Compared with Runx1+/− embryos, Runx1−/− embryos show a reduction of Ter119 expression at E9.5 and E10.5 (Figure 2C,D), indicating that impairment of Runx1−/− primitive erythrocytes already occurred at E9.5, at the molecular level.

Microarray analysis of RNA prepared from the Runx1−/− yolk sac

We next compared the gene expression profile of wild-type and Runx1−/− embryos using microarray analysis to identify potential genes that function downstream of Runx1 in primitive erythropoiesis. For this experiment, we used the E10.5 yolk sac because this organ at this stage is filled with primitive erythrocytes. We found that the expression of 43 genes was reduced in the Runx1−/− yolk sac (P < .01, Table 1). These included at least 2 genes encoding factors known to be involved in erythropoiesis, EKLF and α-hemoglobin stabilizing protein (AHSP).25-27

Genes down-regulated in Runx1−/− yolk sac

| Systematic name . | Gene . | Symbol . | Wild-type signal . | Runx1 KO signal . | Fold change . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H3044F08–3 | Mitogen inducible migct | MGC36836 | 3362.7 | 767.1 | 0.2281 |

| L0240C12–3 | Complement component 1, q subcomponent, alpha polypeptide | C1qa | 3672.5 | 1220.3 | 0.3323 |

| L0075B01–3 | Mus domesticus strain MilP mitocondrion genome, complete sequence | — | 30184.8 | 14344.7 | 0.4752 |

| H3054H09–3 | H3054H09–3 | — | 7727.4 | 4002.2 | 0.5179 |

| M97200.1 | Erythroid Kruppel-like factor | EKLF | 4482.6 | 2440.6 | 0.5445 |

| C0284A02–3 | Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase-1, delta<5>-3-beta | Hsd3b1 | 3796.8 | 2093.6 | 0.5514 |

| L0258G12–3 | Muscleblind-like | Mbnl | 5640.8 | 3188.8 | 0.5653 |

| H3126G01–5 | H3126G01–5 | — | 82880.5 | 47827.7 | 0.5771 |

| H3060E04–3 | Protein kinase C type EC2.7.1- | 6030436C20Rik | 3320.5 | 1954.3 | 0.5886 |

| H3114C08–3 | α-hemoglobin stabilizing protein | AHSP | 8460.8 | 5144.7 | 0.6081 |

| H3087E02–3 | riken cDNA 4933436C10 gene | 4933436C10Rik | 9907.1 | 6159.5 | 0.6217 |

| H3059D10–3 | Cornichon homolog | Cnih | 11741.2 | 7310.0 | 0.6226 |

| J0460E10–3 | J0460E10–3 | — | 5814.1 | 3646.0 | 0.6271 |

| H3048G11–3 | Biliverdin reductase B | Blvrb | 10690.0 | 6713.2 | 0.6280 |

| H3065D10–3 | RAS-related protein-1a | Rap1a | 19757.3 | 12435.3 | 0.6294 |

| L0222E01–3 | Rhesus blood group CE and D | Rhced | 10397.4 | 6590.9 | 0.6339 |

| H3056A02–3 | H3056A02–3 | — | 4661.2 | 2981.7 | 0.6397 |

| H3157F03–3 | riken cDNA 2810465O16 gene | 2810465O16Rik | 5012.1 | 3214.5 | 0.6414 |

| C0321H12–3 | Cell growth regulator | 1110038G02Rik | 8733.7 | 5608.6 | 0.6422 |

| H3076H08–3 | H3076H08–3 | — | 20849.6 | 13503.4 | 0.6477 |

| C0166A10–3 | Carbonic anhydrase 2 | Car2 | 27887.6 | 18109.0 | 0.6494 |

| Systematic name . | Gene . | Symbol . | Wild-type signal . | Runx1 KO signal . | Fold change . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H3044F08–3 | Mitogen inducible migct | MGC36836 | 3362.7 | 767.1 | 0.2281 |

| L0240C12–3 | Complement component 1, q subcomponent, alpha polypeptide | C1qa | 3672.5 | 1220.3 | 0.3323 |

| L0075B01–3 | Mus domesticus strain MilP mitocondrion genome, complete sequence | — | 30184.8 | 14344.7 | 0.4752 |

| H3054H09–3 | H3054H09–3 | — | 7727.4 | 4002.2 | 0.5179 |

| M97200.1 | Erythroid Kruppel-like factor | EKLF | 4482.6 | 2440.6 | 0.5445 |

| C0284A02–3 | Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase-1, delta<5>-3-beta | Hsd3b1 | 3796.8 | 2093.6 | 0.5514 |

| L0258G12–3 | Muscleblind-like | Mbnl | 5640.8 | 3188.8 | 0.5653 |

| H3126G01–5 | H3126G01–5 | — | 82880.5 | 47827.7 | 0.5771 |

| H3060E04–3 | Protein kinase C type EC2.7.1- | 6030436C20Rik | 3320.5 | 1954.3 | 0.5886 |

| H3114C08–3 | α-hemoglobin stabilizing protein | AHSP | 8460.8 | 5144.7 | 0.6081 |

| H3087E02–3 | riken cDNA 4933436C10 gene | 4933436C10Rik | 9907.1 | 6159.5 | 0.6217 |

| H3059D10–3 | Cornichon homolog | Cnih | 11741.2 | 7310.0 | 0.6226 |

| J0460E10–3 | J0460E10–3 | — | 5814.1 | 3646.0 | 0.6271 |

| H3048G11–3 | Biliverdin reductase B | Blvrb | 10690.0 | 6713.2 | 0.6280 |

| H3065D10–3 | RAS-related protein-1a | Rap1a | 19757.3 | 12435.3 | 0.6294 |

| L0222E01–3 | Rhesus blood group CE and D | Rhced | 10397.4 | 6590.9 | 0.6339 |

| H3056A02–3 | H3056A02–3 | — | 4661.2 | 2981.7 | 0.6397 |

| H3157F03–3 | riken cDNA 2810465O16 gene | 2810465O16Rik | 5012.1 | 3214.5 | 0.6414 |

| C0321H12–3 | Cell growth regulator | 1110038G02Rik | 8733.7 | 5608.6 | 0.6422 |

| H3076H08–3 | H3076H08–3 | — | 20849.6 | 13503.4 | 0.6477 |

| C0166A10–3 | Carbonic anhydrase 2 | Car2 | 27887.6 | 18109.0 | 0.6494 |

— indicates not applicable.

Genes down-regulated less than 0.65-fold in Runx1-deficient yolk sacs were listed. Probe informations and gene annotations of Agilent Mouse Development Microarrays are available at the NIA mouse cDNA project home page (http://lgsun.grc.nia.nih.gov/cDNA/cDNA.html).

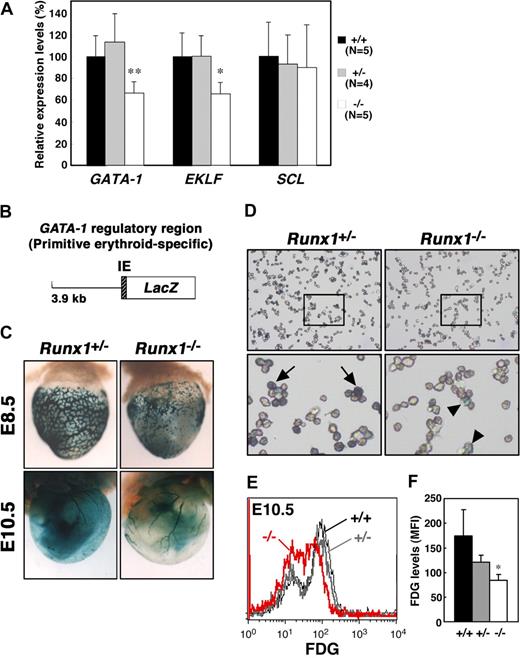

Reduced expression of EKLF and GATA-1 in Runx1−/− embryos

The expression of EKLF and AHSP is regulated by GATA-1,27,28 and knockdown of GATA-1 in embryonic stem cells leads to reduced expression of Ter119,29 leading us to speculate that GATA-1 expression might be affected by Runx1 depletion. GATA-1 is a critical regulator of both definitive and primitive erythrocyte differentiation.30 EKLF is also an important transcription factor involved in adult erythropoiesis and recently has been shown to be involved in the maintenance of both normal morphology and Ter119 expression in primitive erythrocytes.25,26 To quantify the expression of the erythroid transcription factors, GATA-1 and EKLF, in Runx1−/− embryos, we performed quantitative reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis. We also examined the expression of another erythroid transcription factor, SCL/Tal-1. Whereas the expression of SCL in E11.5 Runx1−/− peripheral blood cells was comparable with that observed in Runx1+/− and wild-type blood cells, the level of both GATA-1 and EKLF mRNAs was reduced by approximately 60% in Runx1−/− mice (Figure 3A).

Reduced expression of GATA-1 and EKLF in Runx1−/− primitive erythrocytes. (A) Relative intensity levels were measured by real-time PCR and normalized to GAPDH. The Student t test was applied for statistical analysis. Significant differences in Runx1−/− mice from wild-type were observed (**P = .009, *P = .013). (B) Structure of the GATA-1 promoter-LacZ (IE3.9-LacZ) transgene. IE indicates exon IE. (C) Representative pictures of Runx1+/−::IE3.9-LacZ (n = 7 E8.5, n = 12 E10.5) and Runx1−/−::IE3.9-LacZ (n = 8 E8.5, n = 4 E10.5) embryos. Expression of β-galactosidase was reduced in Runx1−/− embryo (C, right panels) compared with Runx1+/− embryo (C, left panels). (D) Cytospin preparation of blood cells from embryos shown in panel C (E10.5). Intensity of β-galactosidase staining was reduced in Runx1−/− cells ( ) compared with Runx1+/− cells (

) compared with Runx1+/− cells ( ). (E) FACS analysis of GATA-1 (β-galactosidase) expression in E10.5 embryos. FDG was used as a fluorescent substrate for β-galactosidase. Black line, gray bold line, or red bold line represents β-galactosidase expression in Runx1+/+, Runx1+/−, or Runx1−/−, respectively. (F) MFI values of FDG for Runx1+/+ (n = 2), Runx1+/− (n = 5), and Runx1−/− (n = 2) embryos. Significant difference in Runx1−/− mice from Runx1+/− mice was observed (*P = .032 by Student t test). Original magnifications: C (top panels), ×16.0; C (bottom panels), ×7.2; D, ×400. Images in panel C were captured with a Leica MZ FLIII microscope and a Leica DC500 CCD camera with IM50 Imaging Manager, with a PLAN APO 1.0 lens (1.0×/0.125 NA). A Leica DC500 CCD camera with IM50 Imaging Manager through Leica DMRXA microscope was used to capture the images using a 20×/0.50 NA objective for the bottom panel and 5×/0.15 NA objective for the top panels.

). (E) FACS analysis of GATA-1 (β-galactosidase) expression in E10.5 embryos. FDG was used as a fluorescent substrate for β-galactosidase. Black line, gray bold line, or red bold line represents β-galactosidase expression in Runx1+/+, Runx1+/−, or Runx1−/−, respectively. (F) MFI values of FDG for Runx1+/+ (n = 2), Runx1+/− (n = 5), and Runx1−/− (n = 2) embryos. Significant difference in Runx1−/− mice from Runx1+/− mice was observed (*P = .032 by Student t test). Original magnifications: C (top panels), ×16.0; C (bottom panels), ×7.2; D, ×400. Images in panel C were captured with a Leica MZ FLIII microscope and a Leica DC500 CCD camera with IM50 Imaging Manager, with a PLAN APO 1.0 lens (1.0×/0.125 NA). A Leica DC500 CCD camera with IM50 Imaging Manager through Leica DMRXA microscope was used to capture the images using a 20×/0.50 NA objective for the bottom panel and 5×/0.15 NA objective for the top panels.

Reduced expression of GATA-1 and EKLF in Runx1−/− primitive erythrocytes. (A) Relative intensity levels were measured by real-time PCR and normalized to GAPDH. The Student t test was applied for statistical analysis. Significant differences in Runx1−/− mice from wild-type were observed (**P = .009, *P = .013). (B) Structure of the GATA-1 promoter-LacZ (IE3.9-LacZ) transgene. IE indicates exon IE. (C) Representative pictures of Runx1+/−::IE3.9-LacZ (n = 7 E8.5, n = 12 E10.5) and Runx1−/−::IE3.9-LacZ (n = 8 E8.5, n = 4 E10.5) embryos. Expression of β-galactosidase was reduced in Runx1−/− embryo (C, right panels) compared with Runx1+/− embryo (C, left panels). (D) Cytospin preparation of blood cells from embryos shown in panel C (E10.5). Intensity of β-galactosidase staining was reduced in Runx1−/− cells ( ) compared with Runx1+/− cells (

) compared with Runx1+/− cells ( ). (E) FACS analysis of GATA-1 (β-galactosidase) expression in E10.5 embryos. FDG was used as a fluorescent substrate for β-galactosidase. Black line, gray bold line, or red bold line represents β-galactosidase expression in Runx1+/+, Runx1+/−, or Runx1−/−, respectively. (F) MFI values of FDG for Runx1+/+ (n = 2), Runx1+/− (n = 5), and Runx1−/− (n = 2) embryos. Significant difference in Runx1−/− mice from Runx1+/− mice was observed (*P = .032 by Student t test). Original magnifications: C (top panels), ×16.0; C (bottom panels), ×7.2; D, ×400. Images in panel C were captured with a Leica MZ FLIII microscope and a Leica DC500 CCD camera with IM50 Imaging Manager, with a PLAN APO 1.0 lens (1.0×/0.125 NA). A Leica DC500 CCD camera with IM50 Imaging Manager through Leica DMRXA microscope was used to capture the images using a 20×/0.50 NA objective for the bottom panel and 5×/0.15 NA objective for the top panels.

). (E) FACS analysis of GATA-1 (β-galactosidase) expression in E10.5 embryos. FDG was used as a fluorescent substrate for β-galactosidase. Black line, gray bold line, or red bold line represents β-galactosidase expression in Runx1+/+, Runx1+/−, or Runx1−/−, respectively. (F) MFI values of FDG for Runx1+/+ (n = 2), Runx1+/− (n = 5), and Runx1−/− (n = 2) embryos. Significant difference in Runx1−/− mice from Runx1+/− mice was observed (*P = .032 by Student t test). Original magnifications: C (top panels), ×16.0; C (bottom panels), ×7.2; D, ×400. Images in panel C were captured with a Leica MZ FLIII microscope and a Leica DC500 CCD camera with IM50 Imaging Manager, with a PLAN APO 1.0 lens (1.0×/0.125 NA). A Leica DC500 CCD camera with IM50 Imaging Manager through Leica DMRXA microscope was used to capture the images using a 20×/0.50 NA objective for the bottom panel and 5×/0.15 NA objective for the top panels.

To confirm and better visualize the reduced expression of GATA-1 in Runx1−/− primitive erythrocytes, we took advantage of mice transgenic for a GATA-1 promoter-LacZ hybrid gene construct (Figure 3B). We previously reported that a GATA-1 promoter element, 3.9 kb upstream from the GATA-1 proximal promoter (IE) exon is active in primitive but not definitive erythrocytes.19 Thus, we introduced the GATA-1 promoter-LacZ (IE3.9-LacZ) transgene into Runx1 mutant mice as a surrogate to measure GATA-1 expression in Runx1−/− primitive erythrocytes. Consistent with the RT-PCR analysis, expression of β-galactosidase from the transgene was reduced in E10.5 Runx1−/− mice compared with Runx1+/− mice (Figure 3C,D). Similar results were obtained in E8.5 (Figure 3C) and E11.5 embryos (data not shown). Reduced expression of β-galactosidase in Runx1−/− mice was confirmed by FACS analysis (Figure 3E,F), suggesting that GATA-1 expression is dependent on Runx1 in primitive erythrocytes.

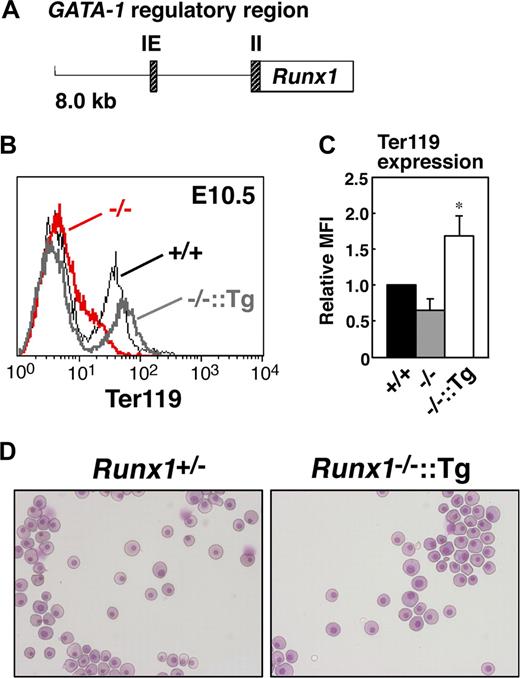

Transgenic rescue of Runx1−/− primitive erythrocytes

To determine whether erythroid-specific reintroduction of Runx1 rescues the abnormal phenotype of Runx1−/− primitive erythrocytes, transgenic mice expressing Runx1 under the control of the GATA-1 hematopoietic regulatory domain (G1-HRD, also called IE3.9int, Figure 4A)19,20 were crossed into the Runx1−/− genetic background. The expression of GATA-1 was observed in the early erythroid progenitors, and G1-HRD significantly recapitulates the endogenous expression profile of GATA-1 in the erythroid lineage.19 Therefore, although GATA-1 expression was reduced by approximately 60% in Runx1−/− genetic background (Figure 3A), we assumed that this regulatory domain is suitable for our erythroid-specific rescue experiment. As expected, normal erythrocyte morphology and Ter119 expression were restored in Runx1−/− mice carrying the G1-HRD-Runx1 transgene (Figure 4B-D). Thus, we conclude that the defect in primitive erythrocytes in Runx1−/− mice is cell autonomous.

Rescue of defects in Runx1−/− primitive erythrocytes by transgenic introduction of Runx1. (A) Structure of the G1-HRD-Runx1 (IE3.9int-Runx1) transgene. IE and II indicate exon IE and II, respectively. (B) Rescue of Ter119 expression on E10.5 Runx1−/− primitive erythrocytes by introducing G1-HRD-Runx1 transgene. Black line, gray bold line, or red bold line represents Ter119 expression in Runx1+/+, Runx1−/−::G1-HRD-Runx1, and Runx1−/−, respectively. Note that overexpression of Runx1 in Runx1−/− erythrocytes induced slightly higher Ter119 expression. (C) Relative MFI values of Ter119 for Runx1+/+ (normalized to MFI = 1), Runx1−/−, and Runx1−/−::G1-HRD-Runx1 embryos at E10.5. Bar graphs represents mean ratios plus or minus SD derived from Runx1−/− (n = 4) and Runx1−/−::G1-HRD-Runx1 (n = 4) embryos. Significant difference in Runx1−/−::G1-HRD-Runx1 mice from Runx1−/− mice was observed (*P < .001 by Student t test). (D) Rescue of abnormal morphology observed in Runx1−/− primitive erythrocytes. May-Grunwald Giemsa stained cytospin preparation of peripheral blood cells from E12.5 embryos. Deformed shape observed in Runx1−/− erythrocytes (Figure 1B) was rarely seen in Runx1−/−::G1-HRD-Runx1 erythrocytes. Images in panels D were captured by Leica DC500 CCD camera with IM50 Imaging manager and a Leica DMRXA microscope using a 20×/0.50 NA objective.

Rescue of defects in Runx1−/− primitive erythrocytes by transgenic introduction of Runx1. (A) Structure of the G1-HRD-Runx1 (IE3.9int-Runx1) transgene. IE and II indicate exon IE and II, respectively. (B) Rescue of Ter119 expression on E10.5 Runx1−/− primitive erythrocytes by introducing G1-HRD-Runx1 transgene. Black line, gray bold line, or red bold line represents Ter119 expression in Runx1+/+, Runx1−/−::G1-HRD-Runx1, and Runx1−/−, respectively. Note that overexpression of Runx1 in Runx1−/− erythrocytes induced slightly higher Ter119 expression. (C) Relative MFI values of Ter119 for Runx1+/+ (normalized to MFI = 1), Runx1−/−, and Runx1−/−::G1-HRD-Runx1 embryos at E10.5. Bar graphs represents mean ratios plus or minus SD derived from Runx1−/− (n = 4) and Runx1−/−::G1-HRD-Runx1 (n = 4) embryos. Significant difference in Runx1−/−::G1-HRD-Runx1 mice from Runx1−/− mice was observed (*P < .001 by Student t test). (D) Rescue of abnormal morphology observed in Runx1−/− primitive erythrocytes. May-Grunwald Giemsa stained cytospin preparation of peripheral blood cells from E12.5 embryos. Deformed shape observed in Runx1−/− erythrocytes (Figure 1B) was rarely seen in Runx1−/−::G1-HRD-Runx1 erythrocytes. Images in panels D were captured by Leica DC500 CCD camera with IM50 Imaging manager and a Leica DMRXA microscope using a 20×/0.50 NA objective.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that Runx1−/− primitive erythrocytes exhibit some abnormal features. Impairment of primitive erythrocytes has also been observed in mice carrying a knocked-in CBFβ-MYH11 gene.31 CBFβ is a heterodimeric binding partner of Runx, and the fusion protein generated from the CBFβ-MYH11 gene functions as a dominant negative inhibitor of Runx1 activity.32 In addition, although data were not shown, Wang et al had noticed subtle abnormalities in the morphology and staining intensity of primitive erythrocytes from Runx1−/− embryos.11 These results further support our contention that Runx1 plays a role in primitive erythropoiesis in the mouse embryo.

Although the morphology of Runx1−/− primitive erythrocytes is not normal, we think that these erythrocytes are nonetheless able to deliver oxygen to body tissues based on the following reasons. First, benzidine staining experiments demonstrated that erythrocytes in Runx1−/− embryos exhibit nearly normal levels of hemoglobinization (Figure 2B). Second, mutant mice lacking GATA-1 (Alas), which exhibit no functional primitive erythrocytes, die around E10.5,33,34 indicating that intact primitive erythrocytes are essential for the survival of the embryo after E11. Unlike these latter mice, Runx1-deficient mice die instead around E12.5.

We showed here that expression of GATA-1 is at least partially dependent on Runx1 expression in primitive erythrocytes (Figure 3). It is unknown, however, whether Runx1 directly regulates GATA-1 transcription. An interaction or association between Runx and GATA has been observed in other biologic systems. Human RUNX1 and GATA-1 physically interact and synergistically activate the megakaryocyte gene in vitro.35 In the Drosophila blood system, coexpression of the GATA factor, Serpent, and the Runt-related factor, Lozenge, enhances crystal cell overproduction.36 Interestingly, mutations in GATA-1 were found in the majority of Down syndrome (constitutional trisomy 21) patients with acute megakaryoblastic leukemia (DS-AMKL), and an extra copy of RUNX1 on chromosome 21 has been suspected to be responsible for the increased risk of DS-AMKL.37 These observations suggest that Runx and GATA factors work cooperatively and may modulate one another's activity in a gene regulatory network.

We have uncovered a previously unrecognized role for Runx1 in mouse primitive erythropoiesis. Runx1 is also expressed during immature stages of definitive erythrocytes.38 In addition, impairment of definitive erythroid differentiation has been observed in an AML patient with a t(8;21) translocation, which results in the production of an AML1-ETO fusion protein.39 These observations suggest that Runx1 may play a role in definitive erythropoiesis. Although there is a report that there is no apparent reduction of the hemoglobin level in Runx1-deficient peripheral blood cells,40 it is worth examining more extensively whether conditional loss of Runx1 in erythroid lineage influences adult erythropoiesis.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr S.-I. Nishikawa for reagents and Dr O. Nakajima for protocol.

This work was supported in part by Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Priority Areas (17013016) and Genome Network Project from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan.

Authorship

Contribution: T.Y. designed and performed research, and wrote the paper; K.H. performed research and analyzed data; H.I. performed cytospin analysis; M.O. and M.E. performed research; Y.I. and M.Y. analyzed data; S.T. designed research and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Satoru Takahashi, Institute of Basic Medical Sciences, University of Tsukuba, 1-1-1 Tennoudai, Tsukuba 305-8575, Japan; e-mail: satoruta@md.tsukuba.ac.jp.

References

Author notes

*T.Y. and K.H contributed equally to this study.