Abstract

To determine when patients with incomplete responses on second-line tyrosine kinase inhibitor (2TKI) therapy should consider alternative treatment, we analyzed the outcome of 113 patients receiving nilotinib (n = 43) or dasatinib (n = 70) after imatinib failure. After 12 months of 2TKI therapy, patients achieving a major cytogenetic response (12MMCyR) had a significant survival advantage over patients in minor cytogenetic response or complete hematologic response, with a projected one-year survival of 97% and 84% respectively (P = .02). Projected 1-year progression to hematologic failure, accelerated phase, or blast phase was also significantly different (3% vs 17%, P = .003). Early cytogenetic response was strongly predictive of achievement of 12MMCyR, with less than 10% of patients showing no cytogenetic response at 3 to 6 months eventually attaining the target of 12MMCyR. These results suggest that patients receiving 2TKI with no cytogenetic response at 3 to 6 months should be considered for alternative therapies.

Introduction

Approximately 30% of patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) receiving imatinib as first-line therapy will discontinue treatment after 5 years because of disease resistance or drug toxicity.1 The novel tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI) dasatinib and nilotinib are currently licensed for the treatment of such patients, inducing a complete hematologic response in 77% to 91% and a complete cytogenetic response (CCyR) in 41% to 53%.2-4 Around half of patients on second- or subsequent-line TKI (2TKI) therapy will therefore have incomplete suppression of the Philadelphia (Ph)-positive clone in the marrow, usually without evidence of overt disease progression. What defines inadequate response (or failure) in these patients, and at which point a recommendation should be made to consider alternative therapy including third-generation TKIs,5,6 homoharringtonine7 or stem cell transplantation,8 remain uncertain. It is also not known if the response kinetics may identify at an early time-point which patients are ultimately destined to fail therapy. To address these questions, we analyzed the pattern of response in 113 patients receiving 2TKI therapy at our institution.

Methods

Patients were treated on sequential phase 1 and 2 protocols of nilotinib (n = 43, 38%) or dasatinib (n = 70, 62%) between November 2003 and April 2007. Approval was obtained from the M. D. Anderson Cancer Center institutional review board for these studies. Informed consent was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Eighty-seven (77%) patients were in chronic phase, and 26 (23%) were in accelerated phase based on the presence of clonal evolution. Patients had marrow cytogenetics repeated every 3 months during the first year of 2TKI therapy, and every 6 months thereafter. Progression was defined as hematologic relapse or progression to accelerated or blastic phase. Cytogenetic relapse was not included in the definition of progression as 6 of 8 patients who lost a transient major cytogenetic response remained without clinical progression a median 11 months (range 5-24) later. Survival was estimated from time of start of therapy with 2TKI until death or last follow-up using the Kaplan-Meier method, and differences compared using the log-rank test. Categorical variables were compared using the Fisher exact or chi-square test, as appropriate. Logistic regression analysis was used to analyze the impact of multiple variables on a binary end point. All P values were 2-sided.

Results and discussion

Baseline patient characteristics for the 113 patients treated were as follows: median age 56 years (range 21-83); median time from diagnosis 65 months (range 4-227); white cell count at least 11 × 109/L, 62 (55%); platelets at least 450 × 109/L, 39 (35%); basophils at least 5%, 27 (24%); blasts at least 5%, 5 (4%); and splenomegaly, 7 (6%). The previous best response to imatinib was CCyR (0% Ph+) in 24 (21%), partial cytogenetic response (PCyR, 1%-35% Ph+) in 20 (18%), minor cytogenetic response (miCyR, 36%-95% Ph+) in 15 (13%), complete hematologic response (CHR) in 40 (35%), hematologic failure in 3 (3%),9 and not known in 11 (10%). Ninety-four (83%) patients failed imatinib due to disease resistance, and 19 (17%) patients ceased due to drug toxicity. Among patients receiving nilotinib (n = 43), the initial daily dose was 400 mg in 5% and at least 800 mg in 95%; 70% received at least 800 mg daily for 6 months or longer. Among patients receiving dasatinib (n = 70), the initial daily dose was less than 100 mg in 17%, 100 mg in 21%, and 140 mg or more in 61%; 72% received at least 100 mg daily for 6 months or longer.

Median survivor follow-up was 27 months (range 6-45), and the projected 2-year overall survival (OS) was 87%. The proportion of cumulative best response in study patients at 3, 6, and 12 months of 2TKI therapy were CCyR, 35%, 42%, and 48%; PCyR, 12%, 8%, and 12%; miCyR, 14%, 14%, and 12%; CHR, 24%, 24%, and 19%; and hematologic failure, 15%, 12%, and 10%, respectively. No individual response category was correlated with a significant long-term survival advantage or disadvantage at 3 and 6 months. At 12 months, a significant survival advantage emerged for the 67 (59%) patients achieving a best response of major cytogenetic response (MCyR: CCyR or PCyR), compared with the 35 (31%) patients in miCyR or CHR (2 year OS 94% vs 81%, P = .05). No survival difference was observed between patients in CCyR and PCyR, or between patients in miCyR or CHR.

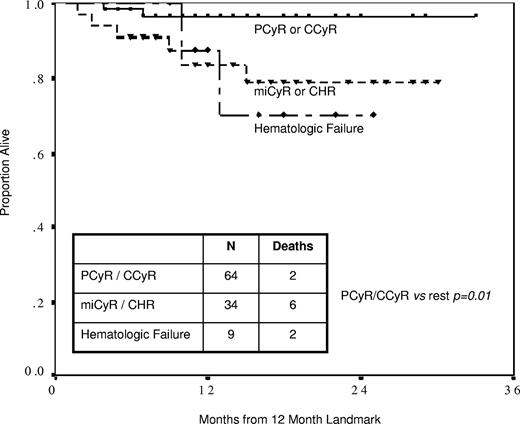

A landmark analysis at twelve months showed that the probability of surviving the next 12 months by best response was 97% for MCyR, 84% for miCyR or CHR, and 88% for hematologic failure (Figure 1). The survival difference was significant for patients in MCyR (P = .01 compared with remainder of patients) but not between miCyR, CHR, and hematologic failure. An identical landmark analysis performed for disease progression showed that the probability of progression over the next year was 3% for patients in MCyR, and 17% for patients in miCyR or CHR (P = .003). These observations confirmed that achieving a MCyR by 12 months (12MMCyR) was an important milestone in patients receiving 2TKI therapy, conferring both survival and progression-free advantage over lesser categories of response. Failure to achieve 12MMCyR is therefore an appropriate definition for inadequate response in patients receiving 2TKI therapy.

Projected survival from 12-month landmark. Patients achieving partial (PCyR) or complete cytogenetic response (CCyR) by 12 months had significantly superior projected survival than patients with minor cytogenetic response (miCyR) or complete hematologic response (CHR; 97% vs 84% at 1 year, P = .02), who in turn had similar projected survival as patients with hematologic failure (88% at 1 year, P = .89).

Projected survival from 12-month landmark. Patients achieving partial (PCyR) or complete cytogenetic response (CCyR) by 12 months had significantly superior projected survival than patients with minor cytogenetic response (miCyR) or complete hematologic response (CHR; 97% vs 84% at 1 year, P = .02), who in turn had similar projected survival as patients with hematologic failure (88% at 1 year, P = .89).

We then examined whether early cytogenetic response was predictive of the ultimate probability of reaching 12MMCyR (Table 1). At 3 months, patients reaching miCyR had a 67% probability of ultimately achieving 12MMCyR, compared with patients without any cytogenetic response, who had only a 7% probability of achieving 12MMCyR (P < .001). At 6 months, these probabilities were 50% and 3% respectively (P < .001). Univariate analysis of baseline factors identified the following to be predictive of 12MMCyR achievement: age less than 65 (P = .03), short time from diagnosis (P = .01), high hemoglobin (P = .001), low white cell count (P = .02), low peripheral blasts (P = .04), and previous cytogenetic response to imatinib (P < .001). Patients who failed imatinib due to intolerance were somewhat more likely to achieve 12MMCyR than those who failed due to disease resistance (79% vs 55%, P = .06). 12MMCyR was achieved with equal frequency among patients in chronic phase (57%) or accelerated phase based on clonal evolution (58%), and among patients receiving nilotinib (56%) or dasatinib (61%). Binary logistic regression analysis identified hemoglobin (P = .003, relative risk [RR] 1.6 per g/dL) and previous cytogenetic response to imatinib (P < .001, RR 7.6) to be independent predictors of 12MMCyR. When the 3-month cytogenetic response to 2TKI therapy was added into the model, all baseline factors lost statistical significance and early cytogenetic response was the only remaining factor in the model, confirming that early cytogenetic response was the most important predictor of 12MMCyR achievement.

Proportions of patients ultimately achieving major cytogenetic response by 12 months (12MMCyR)

| Time point, response . | n . | 12MMCyR, no. (%) . |

|---|---|---|

| Three months | ||

| Minor cytogenetic | 15 | 10 (67) |

| Complete hematologic response or hematologic failure | 42 | 3 (7) |

| Six months | ||

| Minor cytogenetic | 16 | 8 (50) |

| Complete hematologic response or hematologic failure | 39 | 1 (3) |

| Time point, response . | n . | 12MMCyR, no. (%) . |

|---|---|---|

| Three months | ||

| Minor cytogenetic | 15 | 10 (67) |

| Complete hematologic response or hematologic failure | 42 | 3 (7) |

| Six months | ||

| Minor cytogenetic | 16 | 8 (50) |

| Complete hematologic response or hematologic failure | 39 | 1 (3) |

Patients with no cytogenetic responses by 3 and 6 months were significantly less likely to reach 12MMCyR than patients with a minor cytogenetic response (P < .001 at both timepoints).

Achieving a cytogenetic response is a known major determinant of outcome in previous generations of therapy including interferon alpha10,11 and imatinib.12 Our report provides some insight into the significance of the timing of the response when using 2TKI therapy. Based on the current analysis, it is reasonable to recommend consideration of alternative therapy for patients not achieving MCyR by 12 months on 2TKI therapy, as not reaching this milestone is associated with a significant survival and progression disadvantage. The outcomes of lesser degrees of response were disappointing, with projected 1-year survival being not significantly better than that of patients in frank hematologic failure. Early cytogenetic response is strongly predictive of eventual outcome, with less than 10% of patients without cytogenetic response by 3 to 6 months eventually attaining the target of 12MMCyR. Thus, alternative treatment options for patients not achieving any cytogenetic response at these early time points could also be considered.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: C.S.T. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript; J.E.C. designed the study, provided supervision and advice in data analysis and manuscript preparation, and provided clinical care to patients; H.K., G.G.M., G.B., S.O., and F.R. contributed and verified the accuracy of patient data and provided advice and oversight on data analysis and manuscript preparation; and J.S. collected the patient data and coordinated the verification of data integrity.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: J.C. and H.K. receive research funding from Novartis (Basel, Switzerland) and Bristol-Myers Squibb (New York, NY). The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Jorge Cortes, MD, Leukemia Department, Unit 428, The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center, 1515 Holcombe Blvd, Houston, TX 77030; e-mail: jcortes@mdanderson.org.