In this issue of Blood, Arad and colleagues demonstrate that infusion of affinity-purified anti-β2–glycoprotein I (β2GPI) antibodies from 3 patients with antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) into mice enhances the development of arterial thrombosis after laser-induced vascular injury.1 This interesting observation directly demonstrates that human anti-β2GPI antibodies are thrombogenic.

Numerous targets of autoantibodies in patients with APS have been reported, although for most, their utility as predictors of thrombosis has not been rigorously validated. Antibodies against β2GPI were first identified more than 20 years ago,2 and have been the subject of several reports linking them to thrombosis. In the Leiden thrombophilia study, anti-β2GPI antibodies were associated with an odds ratio (OR) for thrombosis of 2.4, in comparison to an OR of 3.6 for the lupus anticoagulant and 1.4 for anti-prothrombin antibodies.3 A lupus anticoagulant in the absence of anti-β2GPI or anti-prothrombin antibodies was not associated with an increased risk of thrombosis, while in the presence of either of these antibodies the OR increased to 10.1. These findings are consistent with results of other studies demonstrating that prolongation of phospholipid-dependent coagulation assays in vitro by lupus anticoagulants is often dependent on the presence of β2GPI, and that assays that detect these “β2GPI-dependent” lupus anticoagulants correlate more specifically with thrombosis.4 In addition, a recent report demonstrated that antibodies with specificity for domain I of β2GPI, which comprise approximately half of all anti-β2GPI antibodies, are associated with an OR for thrombosis of 3.5 compared with that for non-domain I–reactive anti-β2GPI antibodies, which were not associated with thrombosis.5 Taken together, these observations suggest that among the multiple autoantibodies of varying specificity and uncertain significance that exist in patients with APS, anti-β2GPI antibodies are likely to be pathogenic.

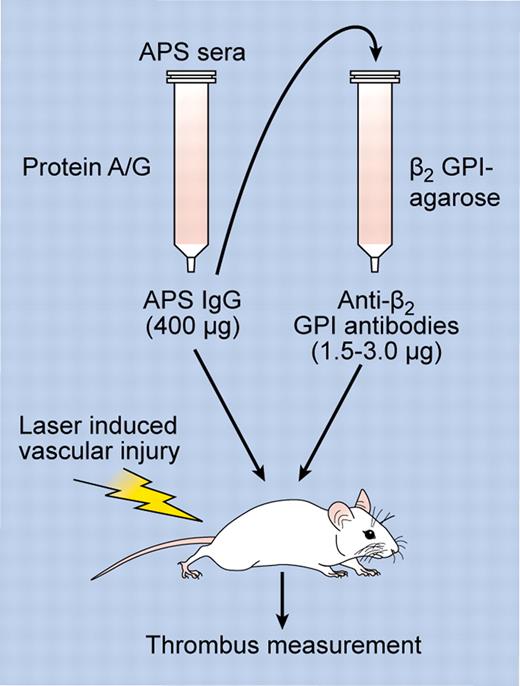

Although several studies have demonstrated that monoclonal antibodies with specificity for β2GPI or phospholipid-β2GPI complexes enhance the development of thrombosis in mice,6 the work of Arad et al is the first to directly demonstrate that this property could be conferred by affinity-purified human anti-β2GPI antibodies.1 Moreover, compared with whole immunoglobulin G (IgG) fractions from patients with APS, affinity purification of the anti-β2GPI antibodies reduced the amount of IgG required to enhance thrombosis by more than 100-fold (eg, 1.5-3.0 μg vs 400 μg per mouse, respectively), demonstrating significant concentration of prothrombotic activity in the affinity-purified preparation (see figure). The 400-μg dose of APS IgG is consistent with that used in other studies examining the ability of IgG fractions from APS patients to enhance the development of thrombosis in vivo; for example, a recent study by Romay-Penebad et al employed 500 μg of APS IgG administered on 2 occasions 48 hours apart.6 It is possible that the apparent difference in activity between anti-β2GPI antibodies and APS IgG may have been amplified by the sensitivity of the fluorescent antibody approach used by Arad et al for thrombus detection, although a more likely explanation is that anti-β2GPI antibodies comprise a small but highly active subset (0.5%-1.5%) of the whole IgG fraction from patients with APS.

Experimental approach. APS sera was used as a source of APS IgG, which was purified using protein A/G beads. APS IgG was then either tested directly for its effects on thrombosis after laser-induced vascular injury (in which case a minimum of 400 μg was required to induce thrombosis), or used as a source for affinity purification of anti-β2GPI antibodies using immobilized β2GPI. The ability of anti-β2GPI antibodies to enhance thrombosis was then assessed after infusion of anti-β2GPI antibodies into mice (only 1.5-3.0 μg of IgG was required to enhance thrombosis). Professional illustration by Kenneth X. Probst.

Experimental approach. APS sera was used as a source of APS IgG, which was purified using protein A/G beads. APS IgG was then either tested directly for its effects on thrombosis after laser-induced vascular injury (in which case a minimum of 400 μg was required to induce thrombosis), or used as a source for affinity purification of anti-β2GPI antibodies using immobilized β2GPI. The ability of anti-β2GPI antibodies to enhance thrombosis was then assessed after infusion of anti-β2GPI antibodies into mice (only 1.5-3.0 μg of IgG was required to enhance thrombosis). Professional illustration by Kenneth X. Probst.

Another interesting aspect of this study, which differs from previous work, is that thrombosis was measured immediately, rather than hours to days, after the administration of anti-β2GPI antibodies. The implications of this methodologic difference on underlying pathogenic mechanisms, if any, are uncertain. Data from other studies in which APS IgG has circulated in mice for 1-2 days have suggested that APS IgG may induce activation of endothelial cells, with increased expression of cell-adhesion molecules7 and tissue factor.6 Whether such effects are relevant to the mechanisms of anti-β2GPI antibodies in the Arad study, or whether the acute enhancement of thrombosis by anti-β2GPI antibodies may reflect other mechanisms such as inhibition of natural anticoagulant activity,8 will require additional study.

A limitation of the Arad study is that anti-β2GPI antibodies from only 3 patients were assessed. Moreover, all patients had secondary APS associated with systemic lupus erythematosus, and an extremely high level of anti-β2GPI antibodies. APS is a disorder with many clinical manifestations,9 and whether in individual patients these reflect differences in antibody specificities, host responses, or both, is uncertain. Thus, whether the molecular characteristics (eg, reactivity against β2GPI domain I) and prothrombotic activity of anti-β2GPI antibodies from, for example, a patient with primary APS and moderate levels of anti-β2GPI antibodies would be identical to that of the antibodies from the patients in the Arad report will require further study. Finally, whether the anti-β2GPI-depleted IgG fraction will be (predictably) devoid of prothrombotic activity in all patients requires assessment.

Willie Sutton was a famous bank robber who stole approximately $2 million between the late 1920s until the time of his final arrest in 1952. Allegedly, when asked why he robbed banks, Sutton responded, “Because that's where the money is.” (In his autobiography Sutton denied this statement, attributing it instead to an enterprising reporter.) This quote, referred to as Sutton's law, is often used to teach medical students to consider the most obvious diagnoses first. With the caveats noted above, the report of Arad et al suggests that when considering the pathogenesis of APS, the “money” lies with anti-β2GPI antibodies. Focused studies on the in vivo and in vitro mechanisms of these antibodies may provide new insight into APS pathogenesis that might ultimately suggest targeted approaches to therapy.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests. ■

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal