Abstract

Dasatinib is a novel, potent, ATP-competitive inhibitor of Bcr-Abl, cKIT, and Src family kinases that exhibits efficacy in patients with imatinib-resistant chronic myelogenous leukemia. Dasatinib treatment is associated with mild thrombocytopenia and an increased risk of bleeding, but its biological effect on megakaryocytopoiesis and platelet production is unknown. In this study, we show that dasatinib causes mild thrombocytopenia in mice without altering platelet half-life, suggesting that it inhibits platelet formation. Conversely, the number of megakaryocytes (MKs) in the bone marrow of dasatinib-treated mice was increased and the ploidy of MKs derived from bone marrow progenitor cells in vitro was elevated in the presence of dasatinib. Furthermore, a significant delay in platelet recovery after immune-induced thrombocytopenia was observed in dasatinib-treated mice even though the number of MKs in the bone marrow was increased relative to controls at all time points. Interestingly, the migration of MKs toward a gradient of stromal cell–derived factor 1α (SDF1α) and the formation of proplatelets in vitro were abolished by dasatinib. We propose that dasatinib causes thrombocytopenia as a consequence of ineffective thrombopoiesis, promoting MK differentiation but also impairing MK migration and proplatelet formation.

Introduction

Dasatinib is a novel, potent, ATP-competitive inhibitor of multiple tyrosine kinases including Bcr-Abl, Src family kinases (SFKs; eg, Fyn, Yes, Src, and Lyn), c-KIT, ephrin A receptor, and PDGF-β receptor kinases.1 It is widely used for the treatment of imatinib-resistant chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML).2-4 CML is a malignant proliferative disorder of hematopoietic stem cells,5 which is characterized by the presence of a constitutively activated form of the Abl tyrosine kinase that is a fusion product between Bcr and Abl resulting from the translocation between chromosome 9 and 22 and is the hallmark of this disease.6 Dasatinib is a second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitor, a more potent inhibitor of Bcr-Abl than imatinib and with activity against other kinases, including SFKs.4 Side effects such as myelosuppression, gastrointestinal symptoms, diarrhea, and fluid retention are commonly observed.7 The risk of bleeding and thrombocytopenia with dasatinib has been clearly established among patients with CML, with fatal brain hemorrhages and gastrointestinal bleeding reported. However, the biological effect of dasatinib on megakaryocytopoiesis and platelet production to explain this observation remains uncharacterized.

Megakaryocytopoiesis is a continuous developmental process of platelet production in which hematopoietic stem cells undergo proliferation and differentiation. Megakaryocytes (MKs) are terminally differentiated hematopoietic cells responsible for platelet production. They are formed in the proliferative osteoblastic niche of the bone marrow (BM) from hematopoietic progenitor cells. Mature MKs migrate to the vascular-rich niche, where they bind to BM endothelial cells and generate proplatelets that enter into the bloodstream,8,9 with the final stage of platelet formation occurring in the blood.10 Megakaryocytopoiesis and platelet production are regulated by a variety of cytokines and chemokines. The primary cytokine-regulating megakaryocytopoiesis is thrombopoietin (TPO), which binds to its cognate receptor c-Mpl to regulate the proliferation and differentiation of MK progenitors and their maturation into proplatelet-forming cells.11,12 The chemokine stromal cell–derived factor 1α (SDF1α) plays a vital role in the migration of MKs from the proliferative osteoblastic niche to the vascular niche through its receptor CXCR4.8,13,14

Six members of the SFKs have been shown to be expressed in MKs and platelets.15,16 SFKs play critical roles in platelet activation by a variety of glycoprotein receptors, including GPVI, CLEC-2, αIIbβ3, and GPIb-IX-V. This includes a key role in mediating changes in cytoskeletal organization, leading to cell spreading and motility.17 Recently, we demonstrated that SFKs also play a critical role in integrin-induced MK spreading, migration, and activation of phospholipase Cγ2 (PLCγ2) in primary BM-derived MKs.18 MKs treated with inhibitors of SFKs are unable to spread or migrate toward a gradient of SDF1α.18 If inhibition of SFKs has the same effect in vivo, then this might account for the mild thrombocytopenia associated with dasatinib treatment, whereas the increase in bleeding tendency would also be explained by the inhibition of platelet activation by glycoprotein receptors.19-21

In the present study, we investigated the effect of dasatinib on megakaryocytopoiesis and platelet production in a murine model. We show that dasatinib causes thrombocytopenia in mice to a level similar to that observed in humans, and confirm that this is due to a defect in platelet production rather than to a shortened platelet half-life. We also show that MK differentiation in vitro is increased in the presence of dasatinib, but that MK migration and proplatelet formation are abolished. We therefore conclude that the thrombocytopenia observed in dasatinib-treated patients is the result of an impairment of MK migration and proplatelet formation rather than a defect in MK growth or an increase in platelet consumption.

Methods

Chemicals

Recombinant murine stem cell factor, TPO, and SDF1α were purchased from PeproTech. Sheep anti–rat IgG Dynabeads, biotin-conjugated rat anti–mouse CD45R/B220, purified rat anti–mouse CD16/CD32, FITC-conjugated anti–mouse GPIIb, streptavidin-PE, and rat anti–mouse GPIIb antibodies were from BD Pharmingen. Anti-mouse Ly-6G and biotin anti–mouse CD11b antibodies were from eBioscience. FITC-conjugated anti–mouse CXCR4 and goat anti–rat IgG FITC antibodies were from R&D Systems. Goat anti–rat IgG Alexa Fluor 488, rhodamine-phalloidin, StemPro medium, and DMEM were from Invitrogen. Anti–mouse GPIbα antibody was from emfret Analytics. Anti-PLCγ2 (DN84) and anti-Syk (BR15) polyclonal antibodies were gifts from Dr Joseph Bolen (DNAX Research Institute, Palo Alto, CA). Dasatinib (Sprycel) was purchased from LC Laboratories. BSA (fatty acid free), ribonuclease A, and biotin-N-hydroxysuccinimide (biotin-NHS) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Bovine plasma fibronectin was purchased from Calbiochem. Anti-Src pan, anti-SFK activation loop phospho-Tyr-418, and anti–Src phospho-Tyr-529 antibodies were obtained from Invitrogen. The anti–phospho-myosin light chain (anti–phospho-MLC) (Thr18/Ser19) and anti-MLC antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology.

Mice

Wild-type mice were of C57Bl/6 background. All procedures were undertaken with United Kingdom Home Office approval in accordance with the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act of 1986 (project license no. 40/2721, 40/9038). CD41-YFPki/+ mice were generated as described previously.10,22 For in vivo imaging, the experimental procedures performed on animals were undertaken according to the requirements of the German legislation.

Platelet aggregation

Blood was collected from CO2-asphyxiated mice by cardiac puncture into heparin (10 U/mL), and platelet-rich plasma was prepared by centrifugation at 200g for 6 minutes. Platelet aggregation was measured using a lumi-aggregometer (Chrono-log).

Preparation and culture of mouse MKs

Mature MKs from mouse BM were defined as the population of cells generated using the methodology described previously.18,23,24 In brief, BM cells were obtained from femurs and tibias of mice by flushing, and cells expressing one or more of the lineage-specific markers on their surface (CD16/CD32+, Gr1+, B220+, or CD11b+) were depleted using immunomagnetic beads (sheep anti–rat IgG Dynabeads). The remaining population was cultured in 2.6% serum-supplemented StemPro medium with 2mM l-glutamine, penicillin/streptomycin, and 20 ng/mL of murine stem cell factor at 37°C under 5% CO2 for 2 days. Cells were then cultured for a further 4 days in the presence of 20 ng/mL of stem cell factor and 50 ng/mL of TPO. After 4 days of culture in the presence of TPO, the cell population was enriched in mature MKs using a 1.5%/3% BSA gradient under gravity (1g) for 45 minutes at room temperature, as described previously.18

MK ploidy and flow cytometry

Expression levels of GPIIb and CXCR4 were measured by flow cytometry using specific antibodies. Polyploidy of mature MKs isolated with a BSA gradient was analyzed after anti-GPIIb labeling and DNA staining with 0.01 mg/mL of propidium iodide. GPIIb-positive cells were gated to analyze DNA content. Samples were acquired using the FACSCalibur flow cytometer and CellQuest software (Becton Dickinson) and analyzed using Summit v4.3 software (DAKO).

Cell migration assay

Chemotaxis was assessed using the Dunn chemotaxis chamber (Weber Scientific International), as described previously.25 To investigate the effect of dasatinib in migration, the Dunn chamber outer well was filled with the medium containing SDF1α (300 ng/mL) and the SFK inhibitor dasatinib (10μM). Time-lapse images were digitally captured every minute for 3 hours using a Zeiss 20 × 1.40 numerical aperture plan-apochromat lens on a Zeiss Axiovert 200 inverted high-end microscope and a Hamamatsu Orca 285 cooled digital camera. SlideBook software Version 5 (3I; http://www.intelligent-imaging.com/) and ImageJ software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/) were used to acquire and process images.

Immune thrombocytopenia

Thrombocytopenia was induced in 8- to 12-week-old wild-type and dasatinib-treated mice (5 mg/kg/d) by intraperitoneal injection of anti-mouse GPIbα antibody (2 μg/g body weight), as described previously.18,26-28 Blood samples were collected before injection (time = 0) and then at 3, 48, 72, 96, 120, 144, and 172 hours after injection by tail bleeding. Platelet counts were measured using an ABX Pentra 60 Hematology Analyzer (Block Scientific).

Platelet half-life

Measurement of platelet lifespan was performed as described previously.29,30 Mice were injected intravenously with 150 μL of 4 mg/mL biotin-NHS. At various time points after injection, whole blood was collected into buffer containing 10% FBS and 5mM EDTA. Ten microliters of blood was washed, pelleted at 1200g for 10 minutes, and stained with anti–mouse GPIIb-FITC and streptavidin-PE for 1 hour on ice. Samples were washed again and the percentage of biotin-labeled platelets (GPIIb+biotin+) was determined by flow cytometry. Platelet survival was estimated from the decay curve of the percentage of biotinylated platelets over time.

MK spreading and proplatelet formation

Coverslips were coated with fibronectin (20 μg/mL), fibrinogen (100 μg/mL), or BSA (100 μg/mL) overnight at 4°C, blocked with denatured BSA (5 mg/mL) for 1 hour at room temperature, and washed with PBS before use. For spreading experiments, mature MKs were incubated for 15 minutes with dasatinib (10μM) and plated on a fibronectin-coated surface for 3 hours at 37°C. For proplatelet formation, mature MKs were incubated for 15 minutes with dasatinib (10μM) and plated on a fibrinogen-coated surface for 5 hours at 37°C. Adherent MKs and MKs forming proplatelets were fixed with 4% formalin permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100. Actin fibers were stained with rhodamine-phalloidin and MKs forming proplatelets with anti–mouse GPIIb-FITC antibody.

MK biochemistry

To study tyrosine phosphorylation events in response to adhesion to fibronectin matrix, Petri dishes were coated with fibronectin (20 μg/mL) or BSA (100 μg/mL) overnight at 4°C, and then blocked with denatured BSA (5 mg/mL) for 1 hour. After BSA gradient, mature MKs were harvested, incubated for 2 hours at 37°C, and then added to fibronectin- or BSA-coated dishes for 3 hours. MKs were either pretreated with DMSO (< 0.1%) or with dasatinib (10μM) for 15 minutes at 37°C before plating. MKs adherent to fibronectin or in suspension over BSA were lysed in ice-cold immunoprecipitation buffer and lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation assays. Samples were precleared for 30 minutes at 4°C with 20 μL of protein G-Sepharose (50% wt/vol). Precleared supernatants were incubated with 2 μL of anti-PLCγ2 Ab (DN84) or 2 μL of anti-Syk Ab (BR15) and 20 μL of protein A Sepharose, and samples were rotated overnight at 4°C. The Sepharose pellet was washed 3 times in lysis buffer before the addition of Laemmli standard sample buffer. Precleared whole cell lysates and immunoprecipitates were resolved by SDS-PAGE on 4%-12% gradient gels (Invitrogen) and immunoblotted with primary antibodies and horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibodies. Proteins were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (GE Healthcare).

Two-photon intravital imaging of BM

Preparation of mouse calvarial BM for intravital imaging was performed according to the protocol described previously.10,31 Mice were anesthetized with 5% isoflurane (Forene) with 0.35 L/min oxygen. During imaging, mice were maintained under anesthesia by intraperitoneal injection (10 mL/kg body weight) of physiological saline containing midazolam (5 mg/kg body weight; Ratiopharm), medetomidine (0.5 mg/kg body weight; Pfizer), and fentanyl (1.6 μg/kg body weight; CuraMED Pharma). Two-photon in vivo imaging was performed with a TriM Scope system (LaVision BioTec) based on a Ti:Sa laser (MaiTai; Spectra Physics) with a TriM Scope Scanhead (LaVision BioTec) to capture images through a 20× water-immersion objective lens (numerical aperture = 0.95; Olympus). BM vasculature was visualized by injection of tetramethylrhodamine isothiocyanate-dextran (TRITC-dextran, 2 MDa; Invitrogen) immediately before imaging. TRITC-dextran signal was detected at a laser wavelength of either 800 or 920 nm using a BrightLine Filter 593/40 (Semrock). Yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) signal was detected at a laser wavelength of 920 nm using a 525/50-nm filter (Semrock). Images were acquired with InspectorPro software Version 5.5 (LaVision BioTec). For 3D acquisition, stacks were acquired at a wavelength of 920 nm with a vertical spacing of 3 μm to cover an axial depth of 30-100 μm (for YFP). Subsequently, the same stacks were acquired at a wavelength of 800 nm (for TRITC). Three-dimensional volume structures were reconstructed using Volocity software Version 5.5 (Improvision) at wavelengths of 920 and 800 nm. Reconstructed 3D structures were used to measure the distance between MKs and vasculature. All mice were treated with murine TPO (ImmunoTools) at 8 μg/kg/d for 3 days before imaging. A previous study demonstrated the normal physiology of thrombopoiesis after TPO treatment.10

Immunohistochemistry

Femurs and spleens were obtained from control and dasatinib-treated mice. Samples were fixed in buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin. Sections (5 μm) were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and examined by light microscopy with a 40× objective. Cryosections (5 μm) of murine femurs were fixed in 4% formalin, blocked in 3% BSA-Tween 0.05%, and stained with anti-mouse GPIIb (1 μg/mL), and then GPIIb was detected with secondary goat anti–rat IgG Alexa Fluor 488 antibody. Three mice were used for each condition, with 8-10 fields of view per tissue sample through 5 marrow sections. Fluorescence images were obtained using a Zeiss Axiovert 200 inverted high-end microscope with a 20× objective.

Statistical analysis

Experiments were performed a minimum of 3 times and images shown are representative of 1 experiment. Data are shown as means ± SEM. Statistical analysis was conducted using 2-tailed Student t test or ANOVA test. P < .05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Dasatinib induces thrombocytopenia in mice

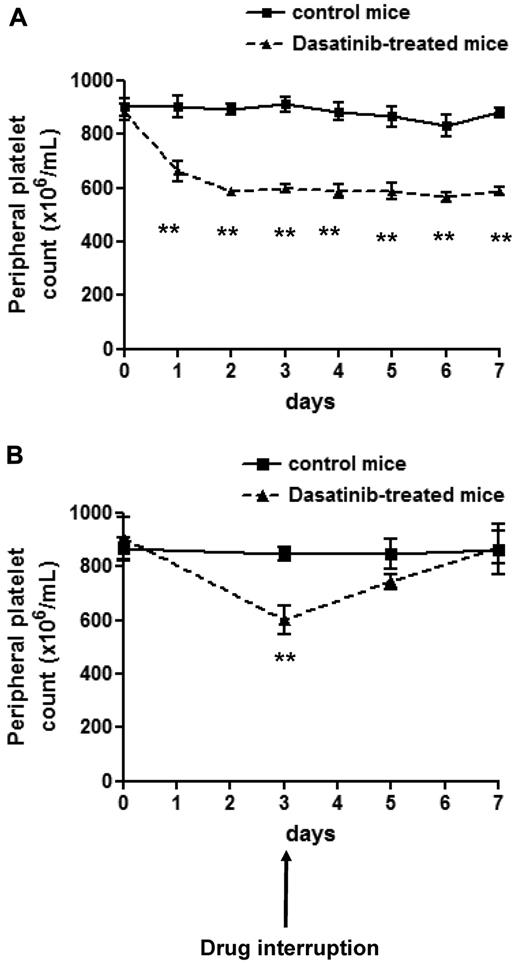

The effect of in vivo administration of dasatinib on the platelet count was investigated. The dose of dasatinib (5 mg/kg/d) caused an increase in tail bleeding times at 4 and 24 hours, with full recovery by 48 hours.20 Consistent with this, we showed previously that this dose completely blocks ex vivo collagen-induced platelet aggregation for up to 6 hours (supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). Treatment with dasatinib caused a reduction in the platelet number over the first 2 days, which reached a plateau at approximately 70% of the original count (Figure 1A). This is similar to the decrease in count in patients with CML treated with dasatinib.19,32 Thrombocytopenia was reversed within 4 days upon discontinuation of treatment (Figure 1B).

Dasatinib induces reversible thrombocytopenia in mice. (A) Whole-blood platelet count from control mice (solid line) and dasatinib-treated (5 mg/kg/d) mice (dashed line) were monitored every day for 7 days. Error bars represent SEM; **P < .01; n = 5 for each time point. (B) Whole-blood platelet count from control mice (solid line) and dasatinib-treated (5 mg/kg/d) mice (dashed line) were monitored 2 and 4 days after interruption of the drug. Error bars represent SEM; **P < .01; n = 3 for each time point.

Dasatinib induces reversible thrombocytopenia in mice. (A) Whole-blood platelet count from control mice (solid line) and dasatinib-treated (5 mg/kg/d) mice (dashed line) were monitored every day for 7 days. Error bars represent SEM; **P < .01; n = 5 for each time point. (B) Whole-blood platelet count from control mice (solid line) and dasatinib-treated (5 mg/kg/d) mice (dashed line) were monitored 2 and 4 days after interruption of the drug. Error bars represent SEM; **P < .01; n = 3 for each time point.

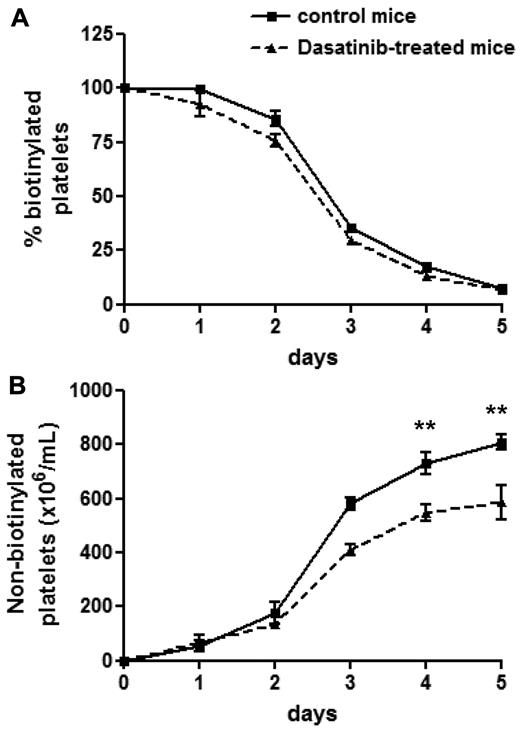

Dasatinib-induced thrombocytopenia is not due to an effect on platelet consumption

To determine whether an increase in platelet consumption could be responsible for the thrombocytopenia, the half-life of circulating platelets was measured after biotinylation, as described previously.29,30 Dasatinib had no significant effect on platelet consumption relative to control mice (Figure 2A). In contrast, the number of new, nonbiotinylated platelets was impaired by approximately 30% (Figure 2B), which is in agreement with the reduction in platelet count described in Figure 1A. These results demonstrate that the thrombocytopenia induced by dasatinib is mediated by defective platelet production but not by altered platelet consumption.

Dasatinib-treated mice exhibit a normal platelet life span. Control mice (solid line) and dasatinib-treated (5 mg/kg/d) mice (dashed line) were intravenously injected with biotin-NHS on day 0 and the percentage of biotinylated platelets was determined at the indicated times by flow cytometry (A). Relating this value to the determined platelet count yielded the number of nonbiotinylated platelets (B). Error bars represent SEM; **P < .01; n = 5 for each time point.

Dasatinib-treated mice exhibit a normal platelet life span. Control mice (solid line) and dasatinib-treated (5 mg/kg/d) mice (dashed line) were intravenously injected with biotin-NHS on day 0 and the percentage of biotinylated platelets was determined at the indicated times by flow cytometry (A). Relating this value to the determined platelet count yielded the number of nonbiotinylated platelets (B). Error bars represent SEM; **P < .01; n = 5 for each time point.

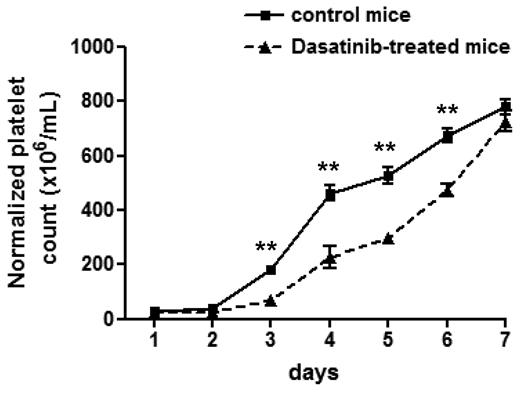

Dasatinib impairs platelet recovery after immune-induced thrombocytopenia

Further experiments were undertaken to investigate whether dasatinib also plays a role in platelet formation after an acute decrease in platelet count. To investigate this, the platelet count was reduced to less than 5% of control levels by injection of an anti-GPIbα antibody. A significant delay in platelet recovery was observed in dasatinib-treated mice after normalization of the data for the different steady-state level of platelets relative to the control group (Figure 3). Therefore, dasatinib not only impairs platelet production at steady state, but also under conditions that require an acute increase in thrombopoiesis.

Dasatinib-treated mice exhibit a delay in platelet recovery after immune-induced thrombocytopenia. Whole-blood platelet count from control mice (solid line) and dasatinib-treated (5 mg/kg/d) mice (dashed line) were obtained, and then thrombocytopenia was induced by an intraperitoneal injection of anti–mouse GPIbα antibody (2 μg/g body weight). Platelet counts were then measured at the indicated times after injection. Error bars represent SEM; **P < .01; n = 5 for each time point.

Dasatinib-treated mice exhibit a delay in platelet recovery after immune-induced thrombocytopenia. Whole-blood platelet count from control mice (solid line) and dasatinib-treated (5 mg/kg/d) mice (dashed line) were obtained, and then thrombocytopenia was induced by an intraperitoneal injection of anti–mouse GPIbα antibody (2 μg/g body weight). Platelet counts were then measured at the indicated times after injection. Error bars represent SEM; **P < .01; n = 5 for each time point.

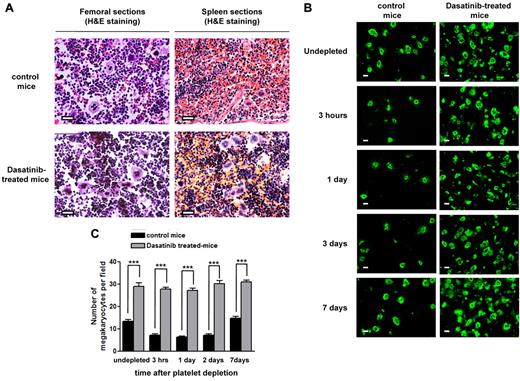

Dasatinib treatment increases the number of MKs in BM

The effect of dasatinib treatment on the number of MKs in murine BM was investigated. Analysis of MK sections using H&E staining (Figure 4A) or by immunofluorescence using an antibody to GPIIb (Figure 4B-C) revealed a 30% increase in MKs in the BM of dasatinib-treated mice. Similarly, there was a significant increase in the number of MKs in the spleen (Figure 4A). Therefore, the decrease in platelet count was not caused by a reduction in the number of MKs.

Dasatinib induces an increased number of mature MKs in BM and spleen. (A) Representative longitudinal sections of whole murine femurs and spleens stained with H&E from control mice and dasatinib-treated (5 mg/kg/d) mice for 7 days (scale bar = 50 μm). (B) Representative longitudinal sections of whole murine femurs from control mice compared with dasatinib-treated (5 mg/kg/d) mice that are undepleted versus platelet depleted after immune-induced thrombocytopenia by anti-GPIbα antibody (2 μg/g body weight) at various time points. MKs were identified by anti-mouse GPIIb-FITC antibody (scale bar = 20 μm). (C) Quantification of the number of MKs in the BM from control and dasatinib treated-mice that are undepleted versus platelet depleted. The average number of MKs per field was determined in GPIIb-stained BM sections throughout the length of 3 femurs; ***P < .005.

Dasatinib induces an increased number of mature MKs in BM and spleen. (A) Representative longitudinal sections of whole murine femurs and spleens stained with H&E from control mice and dasatinib-treated (5 mg/kg/d) mice for 7 days (scale bar = 50 μm). (B) Representative longitudinal sections of whole murine femurs from control mice compared with dasatinib-treated (5 mg/kg/d) mice that are undepleted versus platelet depleted after immune-induced thrombocytopenia by anti-GPIbα antibody (2 μg/g body weight) at various time points. MKs were identified by anti-mouse GPIIb-FITC antibody (scale bar = 20 μm). (C) Quantification of the number of MKs in the BM from control and dasatinib treated-mice that are undepleted versus platelet depleted. The average number of MKs per field was determined in GPIIb-stained BM sections throughout the length of 3 femurs; ***P < .005.

The number of MKs in the BM of mice treated with the anti-GPIbα antibody was also measured. In control animals, the number of MKs was reduced by more than 50% within 3 hours and returned to control levels by 7 days (Figure 4B-C). The decrease in MK number in immunodepleted control mice is believed to be mediated by increased formation of both proplatelets and platelets by a pool of existing mature MKs present in the BM.25 In marked contrast, in the present study, mice treated with dasatinib had a similar number of MKs in BM over the same time period, suggesting that the increase in formation of both proplatelets and platelets is a tyrosine kinase–regulated event (Figure 4B-C).

These results led us to hypothesize that dasatinib promotes MK differentiation but impairs the final stages of platelet production, possibly by impairing MK migration and/or proplatelet formation.

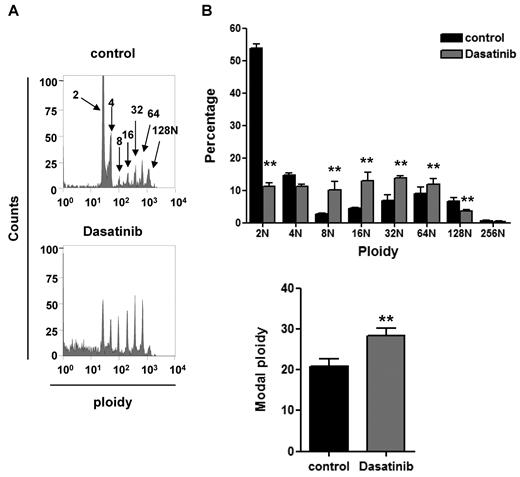

Effect of dasatinib on megakaryocytopoiesis, MK migration, and proplatelet formation in vitro

The molecular basis of the effects of dasatinib were further investigated using primary cultures of MKs grown from BM-derived progenitors cells, as described previously.18 Dasatinib was used at a concentration (10μM) known to be sufficient to inhibit collagen-induced platelet activation through a Src kinase–dependent pathway. In the presence of dasatinib, the percentage of GPIIb-positive MKs increased by 52% (41.0% ± 2.7% for the control versus 61.0% ± 3.4% for dasatinib). In addition, a significant increase in the number of cultured MKs with a ploidy of 8-64 N was observed, with a reduction in those of 2 N likely due to the effect of the drug on the survival of the early progenitors (Figure 5A-B). Therefore, there was a net increase in the overall ploidy, which is consistent with previous reports of increased megakaryocytopoiesis in mice deficient in the Src kinase Lyn33 and in in vitro primary cultures of BM progenitors treated with SFK inhibitors.34 The increase in MK ploidy is consistent with the increase in the number of MKs in the BM of dasatinib-treated mice.

Dasatinib increases MK ploidy in vitro. Progenitor cells isolated from murine BM were treated with 10μM dasatinib along with TPO at the beginning of the differentiation process and 24 hours later. Four days after the addition of TPO, DNA ploidy was analyzed using flow cytometry by staining purified BM-derived mature MKs with propidium iodide and anti–mouse GPIIb-FITC antibody. (A) Representative profiles and (B) quantification of the percentage of cells with differing levels of ploidy and the modal ploidy from 4 independent experiments are shown; **P < .01.

Dasatinib increases MK ploidy in vitro. Progenitor cells isolated from murine BM were treated with 10μM dasatinib along with TPO at the beginning of the differentiation process and 24 hours later. Four days after the addition of TPO, DNA ploidy was analyzed using flow cytometry by staining purified BM-derived mature MKs with propidium iodide and anti–mouse GPIIb-FITC antibody. (A) Representative profiles and (B) quantification of the percentage of cells with differing levels of ploidy and the modal ploidy from 4 independent experiments are shown; **P < .01.

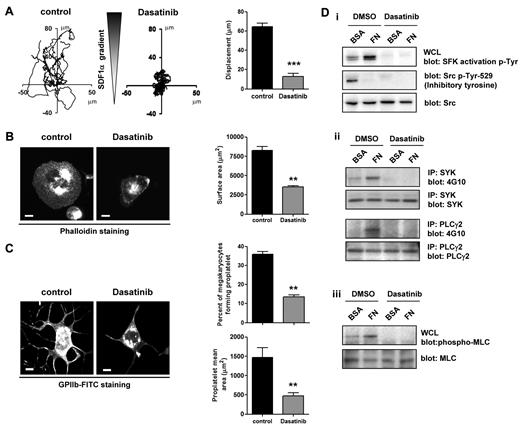

In vivo, MKs migrate from the proliferative osteoblastic niche to the capillary-rich vascular niche, where proplatelet formation takes place. We previously modeled this movement by monitoring the migration of MKs on a fibronectin matrix toward a gradient of SDF1α using a Dunn chamber.18,25 In this assay, migration of MKs was abolished in the presence of dasatinib (Figure 6A). Furthermore, MKs failed to spread on fibronectin and showed a diminished formation of proplatelets on fibrinogen in the presence of dasatinib (Figure 6B-C). These results are in agreement with the recent observation that the SFK inhibitor PP1 also blocks MK migration and spreading on fibronectin.18 The inhibitory action of SFKs is mediated by the loss of outside-in signaling from integrin αIIbβ3, resulting in the inhibition of phosphorylation of Src and Syk tyrosine kinases, PLCγ2, and MLC.18 In keeping with this mechanism, we observed a loss of phosphorylation of these proteins in the presence of dasatinib (Figure 6D i-iii).

Dasatinib impairs MK migration in response to a SDF1α gradient, spreading, proplatelet formation, and integrin-induced tyrosine phosphorylation. (A) Purified BM-derived mature MKs adherent on a fibronectin (20 μg/mL)–coated coverslip were allowed to migrate toward a SDF1α gradient over 3 hours within the Dunn chamber in which the outer well contained SDF1α (300 ng/mL) and dasatinib (10μM), as described in “Methods.” The migration paths over 3 hours were traced. The intersection of the x and y axes was taken to be the starting point of each cell path, whereas the source of SDF1α was at the top. The net translocation distance (displacement from the start to the end point) of each cell in the absence or presence of dasatinib is represented; ***P < .005. (B) Purified BM-derived mature MKs were incubated in the presence or absence of 10μM dasatinib for 15 minutes at 37°C. MKs were plated on a fibronectin-coated surface for 3 hours at 37°C. Adherent MKs were fixed and permeabilized and actin fibers were stained with rhodamine-phalloidin. Representative images and surface area quantification from 4 independent experiments are shown (scale bar = 20 μm); **P < .01. (C) Purified BM-derived mature MKs were incubated in the presence or absence of 10μM dasatinib for 15 minutes at 37°C. MKs were plated on a fibrinogen-coated surface for 5 hours at 37°C, fixed, and labeled with an anti–mouse GPIIb-FITC antibody. Representative images, percentage of MKs forming proplatelets, and proplatelet mean area were quantified and data are presented as means ± SEM of 4 independent experiments; **P < .01. (D) Purified BM-derived mature MKs were preincubated for 15 minutes with 10μM dasatinib and plated on a fibronectin (FN)- or BSA-coated dish for 3 hours. (i) MKs were lysed and whole-cell lysates (WCL) were western blotted with SFK activation loop p-Tyr-418, Src inhibitory site p-Tyr-529, and pan Src antibodies. (ii) Syk and PLCγ2 were immunoprecipitated from equal amounts of whole-cell lysates and blotted with an anti-phosphotyrosine antibody. Membranes were subsequently stripped and reblotted with anti-Syk and anti-PLCγ2 antibodies. (iii) MKs were lysed and whole cell lysates were western blotted with MLC-P and MLC antibodies. Western blots are representative of 3 independent experiments.

Dasatinib impairs MK migration in response to a SDF1α gradient, spreading, proplatelet formation, and integrin-induced tyrosine phosphorylation. (A) Purified BM-derived mature MKs adherent on a fibronectin (20 μg/mL)–coated coverslip were allowed to migrate toward a SDF1α gradient over 3 hours within the Dunn chamber in which the outer well contained SDF1α (300 ng/mL) and dasatinib (10μM), as described in “Methods.” The migration paths over 3 hours were traced. The intersection of the x and y axes was taken to be the starting point of each cell path, whereas the source of SDF1α was at the top. The net translocation distance (displacement from the start to the end point) of each cell in the absence or presence of dasatinib is represented; ***P < .005. (B) Purified BM-derived mature MKs were incubated in the presence or absence of 10μM dasatinib for 15 minutes at 37°C. MKs were plated on a fibronectin-coated surface for 3 hours at 37°C. Adherent MKs were fixed and permeabilized and actin fibers were stained with rhodamine-phalloidin. Representative images and surface area quantification from 4 independent experiments are shown (scale bar = 20 μm); **P < .01. (C) Purified BM-derived mature MKs were incubated in the presence or absence of 10μM dasatinib for 15 minutes at 37°C. MKs were plated on a fibrinogen-coated surface for 5 hours at 37°C, fixed, and labeled with an anti–mouse GPIIb-FITC antibody. Representative images, percentage of MKs forming proplatelets, and proplatelet mean area were quantified and data are presented as means ± SEM of 4 independent experiments; **P < .01. (D) Purified BM-derived mature MKs were preincubated for 15 minutes with 10μM dasatinib and plated on a fibronectin (FN)- or BSA-coated dish for 3 hours. (i) MKs were lysed and whole-cell lysates (WCL) were western blotted with SFK activation loop p-Tyr-418, Src inhibitory site p-Tyr-529, and pan Src antibodies. (ii) Syk and PLCγ2 were immunoprecipitated from equal amounts of whole-cell lysates and blotted with an anti-phosphotyrosine antibody. Membranes were subsequently stripped and reblotted with anti-Syk and anti-PLCγ2 antibodies. (iii) MKs were lysed and whole cell lysates were western blotted with MLC-P and MLC antibodies. Western blots are representative of 3 independent experiments.

We also considered the possibility that dasatinib could also affect the function or expression of the SDF1α chemokine receptor CXCR4 on MKs. Treatment with the Src kinases inhibitor had no effect on expression of CXCR4 (supplemental Figure 2A). Conversely, dasatinib inhibits SDF1α-induced aggregation of mouse platelets (supplemental Figure 2B). This is likely to reflect the role of Src kinases in supporting platelet aggregation by Gi-coupled receptors, as was recently reported for the activation of human platelets by adrenaline.35 That study demonstrated that dasatinib did not block inhibition of adenylyl cyclase by adrenaline, thereby indicating that Src kinases synergize with other Gi-regulated pathways to mediate platelet activation. In a similar way, Src kinases may contribute to the migration of MKs to SDF1α, and loss of this could contribute to the reduced aggregation.

We concluded that the inhibition of MK migration and/or proplatelet formation is the likely mechanisms through which dasatinib causes thrombocytopenia.

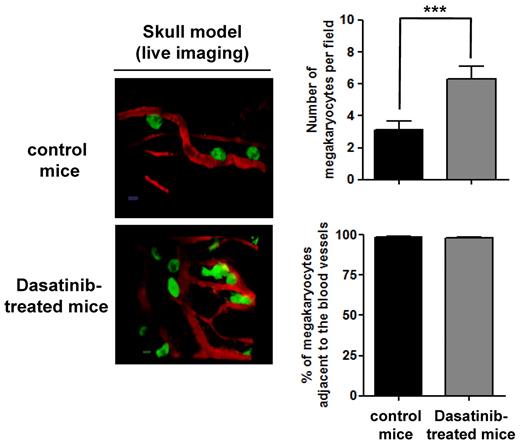

Localization of MKs in BM

To investigate the molecular basis of the thrombocytopenia in further detail, we investigated whether MKs from dasatinib-treated mice are localized to the osteoblastic niche. This was investigated using 2-photon intravital microscopy in BM in the mouse skull. MKs were identified using CD41-YFPki/+ mice in which enhanced YFP was expressed as a targeted transgene from the endogenous gene locus for the αIIb-integrin subunit.22 As shown in Figure 7, MKs are primarily localized to BM sinusoids, with no apparent difference between control and dasatinib-treated mice. Conversely, the number of MKs in the BM of dasatinib-treated mice was increased by approximately 30% in the in vivo skull model, which is in accordance with the results in femoral BM (Figure 4). The observation that the number of MKs in the BM was increased but that their distribution was seemingly unaltered supports a model in which a defect in proplatelet formation is the primary mechanism underlying the thrombocytopenia seen in the presence of dasatinib.

Localization of MKs in BM of dasatinib-treated mice. Localization of MKs in vivo was visualized by 2-photon intravital microscopy using mouse skull BM. The MKs (green) were identified using CD41-YFPki/+ mice in which enhanced YFP was expressed as a targeted transgene from the endogenous gene locus for CD41, a MK- and platelet-specific integrin. BM vasculature (red) was visualized by injection of TRITC-dextran (2 MDa) immediately before imaging. The average number of MKs per field and the percentage of MKs adjacent to the BM vasculature were determined in control CD41-YFPki/+ mice compared with dasatinib-treated mice (scale bar = 20 μm); ***P < .005.

Localization of MKs in BM of dasatinib-treated mice. Localization of MKs in vivo was visualized by 2-photon intravital microscopy using mouse skull BM. The MKs (green) were identified using CD41-YFPki/+ mice in which enhanced YFP was expressed as a targeted transgene from the endogenous gene locus for CD41, a MK- and platelet-specific integrin. BM vasculature (red) was visualized by injection of TRITC-dextran (2 MDa) immediately before imaging. The average number of MKs per field and the percentage of MKs adjacent to the BM vasculature were determined in control CD41-YFPki/+ mice compared with dasatinib-treated mice (scale bar = 20 μm); ***P < .005.

Discussion

The present study provides several new insights into the effects of dasatinib on megakaryocytopoiesis and platelet formation. We demonstrated that dasatinib causes a reversible thrombocytopenia in a murine model, which is in agreement with similar clinical observations reporting its thrombocytopenic effect after chronic administration to humans.19 This thrombocytopenia was not caused by an accelerated clearance of platelets, but was most likely due to a defect in platelet production. Supporting this observation, we demonstrated that platelet recovery after immune thrombocytopenia was delayed in dasatinib-treated mice. This thrombocytopenia, along with the loss of platelet activation by platelet glycoprotein receptors including the collagen receptor GPVI,20 is likely to underlie the increased bleeding that is seen in humans.

We examined the effect of dasatinib on the number of MKs within the BM of mice. Histological sections of BM from treated and untreated animals clearly showed that dasatinib induced a significant increase in the number of MKs within the BM. We further substantiated our findings in vivo using immunostaining of dasatinib-treated mouse BM and confirmed a significant increase in the number of MKs within the BM compared with control mice. In addition, we found that after platelet depletion, MKs were inappropriately retained in the BM of dasatinib-treated mice, whereas a significant decrease in the number of MKs was observed in the BM of control animals. We therefore postulate that dasatinib causes thrombocytopenia not by decreasing MK production and maturation, but rather by impairing the mechanism through which the MKs move to the vascular niche and/or by interfering with the terminal stage of platelet production through the process of proplatelet formation.

Evidence in support of this proposal was provided by a series of in vitro studies. First, dasatinib enhanced the differentiation of cultured MKs in vitro, which is in agreement with previous studies showing the negative role of SFKs in MK differentiation using both the SFK inhibitor PP1 and Lyn-deficient mice.33,34 Second, migration in response to SDF1α in the presence of dasatinib was abolished. This is consistent with previous studies showing a similar effect of the SFK inhibitor PP1 (although it is possible that the positive effect of dasatinib on MK differentiation contributed indirectly to the reduction in migration, because fully differentiated MKs have a reduced migratory capacity).10,36 Third, spreading and proplatelet formation were abolished by dasatinib. The likely molecular mechanism for this effect is inhibition of phosphorylation of the active site of SFKs and loss of signaling downstream of integrin αIIbβ3. These observations are consistent with previous reports showing that MK spreading and migration and the rate of platelet recovery after immune-induced thrombocytopenia are reduced in mice deficient in the protein tyrosine phosphatase CD148. This is believed to be due the role of CD148 in regulating global SFK activity in platelets.28

We sought to further establish whether it is the inhibition of migration and/or the decrease in proplatelet formation that mediates dasatinib-induced thrombocytopenia by investigating the spatial localization of MKs in BM. Using an in vivo model of skull imaging, we showed that MKs were primarily localized to BM sinusoids, with no apparent difference between control and dasatinib-treated mice. The number of MKs in the BM of dasatinib-treated mice was increased, which is consistent with the results observed in femoral BM sections. The increased number of MKs in the BM and unaltered distribution provide indirect evidence that the defect in proplatelet formation may be the primary mechanism underlying the thrombocytopenia that is seen in the presence of dasatinib. This phenomenon is particularly striking in the immune thrombocytopenia model, in which a pool of “reserve” mature MKs located in the vascular niche is called on to acutely replenish platelet numbers, presumably by proplatelet formation. This is reflected by the rapid and marked decrease in the number of MKs in the control animals, which was not seen in the presence of dasatinib.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated using complementary approaches that the inhibition of SFKs by dasatinib treatment strongly affects MK biology both in vitro and in vivo. We demonstrated that, in vivo, dasatinib rapidly and reversibly induced thrombocytopenia and increased the number of mature MKs in the BM. We further showed that, in vitro, MK migration in response to SDF1α, MK spreading and proplatelet formation were abolished by dasatinib. These effects, combined with the inhibitory effects of dasatinib on platelet activation,20,21 may explain the bleeding observed in patients treated with dasatinib for imatinib-resistant CML.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the British Heart Foundation (PG/07/041). A.M. is a postdoctoral research fellow (PG/07/041/22896), C.G. has a lectureship, and S.P.W. is a chair (CH/03/003) with the British Heart Foundation.

Authorship

Contribution: A.M. designed and performed research, collected, analyzed, and interpreted data, performed statistical analysis, and wrote the manuscript; C.G. designed the research and discussed the results; L.Z. performed part of the in vivo experiments and discussed the results; S.M. contributed to designing the study and discussed the results; and S.P.W. designed and supervised the research and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Alexandra Mazharian, Centre for Cardiovascular Sciences, Institute of Biomedical Research, School of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, College of Medical and Dental Sciences, University of Birmingham, Wolfson Dr, Edgbaston, Birmingham, B15 2TT, United Kingdom; e-mail: a.mazharian@bham.ac.uk.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal