Abstract

This study assessed the cumulative incidence of clinically significant cardiac disease in 1279 Hodgkin lymphoma patients treated with mediastinal irradiation and quantified the standard incidence ratios (SIRs) and absolute excess risks of cardiac procedures compared with a normal matched population. Cox regression analysis was used to explore factors associated with cardiac complications. Poisson regression analysis of SIRs was used to estimate the excess risk of cardiac interventions from mediastinal irradiation. After a median follow-up of 14.7 years, 187 patients experienced 636 cardiac events and 89 patients required a cardiac procedure. 5-, 10-, 15-, and 20-year cumulative incidence rates of cardiac events were 2.2%, 4.5%, 9.6%, and 16%. SIRs for cardiac procedures were increased for coronary artery bypass graft (3.19), percutaneous intervention (1.55), implantable cardioverter defibrillator or pacemaker placement (1.9), valve surgery (9.19), and pericardial surgery (12.91). Absolute excess risks were 18.2, 19.3, 9.4, 14.1, and 4.7 per 10 000 person-years, respectively. Older age at diagnosis and male sex were predictors for cardiac events. However, younger age at diagnosis was associated with excess risk specifically from radiation therapy compared with the general population. These results may help guideline development for both the types and timing of cardiac surveillance in survivors of Hodgkin lymphoma.

Introduction

In the United States, approximately 8490 people were diagnosed with Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) in 2010.1 With advances in therapy, HL has become highly curable, with survival rates approaching 95% for patients with early-stage disease2 and 75% for those with advanced disease.3 The challenge presently is to treat HL with minimal toxicity to normal tissue. Approximately 50% of patients have mediastinal disease and may require radiation therapy (RT) to the chest, with potential exposure of cardiac structures to radiation. As survivors age, their risk of dying from cardiac causes significantly increases.4-12 Data on nonfatal cardiac morbidity in these patients, including coronary artery disease, conduction abnormalities, valvular disease, and pericardial disease also exists.13-21 However, few reports compare clinically significant morbidity rates in HL patients with those in the general population.22-24

In this study, we assessed the incidence of clinically significant cardiac disease in a single-institution population of HL patients treated with mediastinal irradiation. Specifically, we determined whether the incidence of clinically significant cardiac disease requiring an intervention was greater in our HL population than in the general population. In addition, the time to development of each cardiac diagnosis and intervention and associated patient- and treatment-related factors were evaluated.

Methods

Patient population

Between 1969 and 1998, 1279 patients with clinical Stage IA-IVB HL were treated with mediastinal RT at these Harvard-affiliated hospitals: Brigham and Women's Hospital, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Children's Hospital or Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. These constitute the study population for this Institutional Review Board–approved retrospective review.

Definition of events

Four categories of clinically significant cardiac events were defined: coronary artery disease (CAD), arrhythmias, valvular disease, and pericardial disease. CAD was defined as a history of documented myocardial infarction (MI), coronary bypass graft surgery (CABG), percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA) with or without stenting, or stenosis of > 75% of the diameter of the vessel on coronary angiography. Arrhythmias were defined as documented pacemaker or automatic implantable cardioverter defibrillator (AICD) placement, ablation procedure or disturbance on electrocardiogram or Holter monitoring. These included atrial fibrillation, ventricular tachycardia or supraventricular tachycardia, heart block or conduction delays, and premature beats associated with symptoms. Valvular disease was defined as a history of valve repair or moderate or severe stenosis or insufficiency documented on echocardiogram or angiogram. Pericardial disease was defined as pericarditis requiring pericardiectomy or pericardial effusion requiring pericardiocentesis.

Treatment information

Earlier patients were treated predominantly with RT alone and more recent patients with combined modality therapy. The radiation fields included total nodal irradiation in 9.5%, mantle and para-aortic in 55.7%, mantle alone in 30.7%, and mediastinal involved-field in 4% of patients. Treatments were delivered through an anteroposterior-posteroanterior approach, with delivery of both equally weighted fields daily. Before 1995, 2-dimensional radiation planning was used with dose prescription to the isocenter; after 1995, 3-dimensional planning with computed tomography (CT) guidance became available and the dose was generally prescribed to the isodose line encompassing the clinical target volume. As the majority of patients included in the study were planned in the preCT planning era, the dose to cardiac structures was not available. As was done in other studies,12,22,24 the midmediastinal dose was used to estimate the dose to the heart. The median midmediastinal dose was 40 Gy (range, 15-53 Gy) at a daily fraction of 1.8-2.0 Gy and 89.4% of patients received > 36 Gy.

Data collection

Information was obtained retrospectively through RT, hospital, and physician records. Patient-related factors recorded included age at treatment, stage, and sex. Treatment-related factors included time from treatment, decade of treatment, RT field, radiation dose, and chemotherapy (specifically, use of doxorubicin).

Statistical analysis

For all analyses, STATA/SE 9.2 and Microsoft Excel 2003 software was used. Diagnosis and procedure incidence data from the National Hospital Discharge Survey from 1979-2003 were accessed to estimate a baseline age- and sex-stratified national utilization rate for percutaneous intervention (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM] codes 36.01-36.09); CABG (ICD-9-CM 36.10-36.19); pacemaker implantation (ICD-9-CM 00.50, 00.53, 37.80-37.89); AICD placement (ICD-9-CM 00.51, 37.94, V45.00-V45.02); valve surgery (ICD-9-CM 35.0-35.28); pericardial surgery (ICD-9-CM 37.31, 37.12, or 37.49); and pericardiocentesis (ICD-9-CM 37.0). The stratified national diagnosis and procedure utilization rates were applied to the year 2000 United States population standard from census data to establish expected age- and sex-stratified incidence rates per person-year for these procedures. Procedure incidences in our database were then compared with this estimated expected national incidence. Standard incidence ratios (SIRs) were calculated as the ratio of the observed to the expected number of cases. Standard error (SE) approximations in the estimation of baseline incidence rates were calculated using the standard method outlined in National Hospital Discharge Survey documentation.25 The absolute excess risk (AER) of an event was calculated by subtracting the number of expected events from the observed events, dividing by the person-years of follow-up and multiplying by 10 000 to estimate the excess number of cases per 10 000 person-years.

Actuarial risk assessments were measured from the date RT ended to the date of first cardiac event or death. For those without a cardiac event, risk was censored at the date the patient was last known to be free of cardiac events. Cumulative incidence estimates were calculated using death as a competing variable.26,27

Multivariable Cox regression analysis was used to evaluate patient- and treatment-related variables as potential predictors for clinically significant cardiac events and for cardiac procedures adjusting for confounders. The variables explored included: age at diagnosis (< 20, 20-29, 30-39, 40-49, ≥ 50 years), mediastinal dose (< 36 Gy vs ≥ 36 Gy), sex, use of chemotherapy and, specifically, doxorubicin use. Hazard ratios (HRs) were calculated as a measure of relative risk. To estimate the specific contribution of radiation therapy to the excess risk of developing cardiac disease requiring surgical intervention, Poisson regression analysis of SIRs was performed, controlling for all other variables.28 Incident rate ratios (IRRs) of SIRs, using patients treated at the youngest age group as reference, were also calculated. Likelihood ratio tests were conducted using 2-sided P values and 95% likelihood–based confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. P values less than .05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics are detailed in Tables 1 and 2. Median age at diagnosis was 25 years (range, 3-93 years). Most patients (85.6%) had stage I-II disease. A total of 780 patients (61%) received RT alone and 499 (39%) received RT and chemotherapy. Median follow-up time for the entire cohort was 14.7 years (interquartile range, 8.1-21 years). Median follow-up times for those treated with radiation alone and those treated with chemotherapy and radiation were 19.3 years (interquartile range, 13.8-25.8 years) and 15 years (interquartile range, 8.8-21.4 years), respectively. Of all patients, 87% had > 5 years of follow-up, 67% had > 10 years, and 48% had > 15 years. The total number of person-years of follow-up was 19 184.

Patient and treatment characteristics

| Characteristic . | HL patients . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without cardiac events (n = 1092) . | With cardiac events (n = 187) . | Total (N = 1279) . | ||||

| n . | % . | n . | % . | n . | % . | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 524 | 48.0 | 70 | 37.4 | 594 | 46.4 |

| Male | 568 | 52.0 | 117 | 62.6 | 685 | 53.6 |

| Age at diagnosis, y | ||||||

| Median (range) | 25 (3-93) | 29 (5-75) | 25 (3-93) | |||

| < 20 | 325 | 29.8 | 36 | 19.3 | 361 | 28.2 |

| 20-29 | 400 | 36.6 | 60 | 32.1 | 460 | 36 |

| 30-39 | 216 | 19.8 | 35 | 18.7 | 251 | 19.6 |

| 40-49 | 79 | 7.2 | 26 | 13.9 | 105 | 8.2 |

| ≥ 50 | 72 | 6.6 | 30 | 16 | 102 | 8 |

| Median age at cardiac events, y (range) | N/A | 47 (14-87) | N/A | |||

| Clinical stage | ||||||

| I | 240 | 22.0 | 45 | 24.1 | 285 | 22.3 |

| II | 694 | 63.6 | 115 | 61.5 | 809 | 63.3 |

| III | 110 | 10.1 | 25 | 13.4 | 135 | 10.6 |

| IV | 48 | 4.4 | 2 | 1.1 | 50 | 3.9 |

| Follow-up, y | ||||||

| Median (interquartile range) | 13.5 (17.5-19.7) | 21.4 (15-27.7) | 14.7 (8.1-21) | |||

| > 5 | 938 | 85.9 | 180 | 96.3 | 1118 | 87.4 |

| > 10 | 696 | 63.7 | 164 | 87.7 | 860 | 67.2 |

| > 15 | 476 | 43.6 | 140 | 74.9 | 616 | 48.2 |

| Treatment | ||||||

| RT alone | 646 | 59.2 | 134 | 71.7 | 780 | 61.0 |

| RT + chemotherapy | 446 | 40.8 | 53 | 28.3 | 499 | 39.0 |

| Median mediastinal dose, Gy (range) | 40 (15-53) | 40 (15-46) | 40 (15-53) | |||

| RT field | ||||||

| Mantle alone | 357 | 32.7 | 36 | 19.3 | 393 | 30.7 |

| MPA | 594 | 54.4 | 119 | 63.6 | 713 | 55.7 |

| TNI | 93 | 8.5 | 29 | 15.5 | 122 | 9.5 |

| Involved field | 48 | 4.4 | 3 | 1.6 | 51 | 4.0 |

| Doxorubicin | ||||||

| No | 872 | 79.8 | 174 | 93.1 | 1046 | 81.8 |

| Yes | 220 | 20.1 | 13 | 6.9 | 233 | 18.2 |

| Characteristic . | HL patients . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without cardiac events (n = 1092) . | With cardiac events (n = 187) . | Total (N = 1279) . | ||||

| n . | % . | n . | % . | n . | % . | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 524 | 48.0 | 70 | 37.4 | 594 | 46.4 |

| Male | 568 | 52.0 | 117 | 62.6 | 685 | 53.6 |

| Age at diagnosis, y | ||||||

| Median (range) | 25 (3-93) | 29 (5-75) | 25 (3-93) | |||

| < 20 | 325 | 29.8 | 36 | 19.3 | 361 | 28.2 |

| 20-29 | 400 | 36.6 | 60 | 32.1 | 460 | 36 |

| 30-39 | 216 | 19.8 | 35 | 18.7 | 251 | 19.6 |

| 40-49 | 79 | 7.2 | 26 | 13.9 | 105 | 8.2 |

| ≥ 50 | 72 | 6.6 | 30 | 16 | 102 | 8 |

| Median age at cardiac events, y (range) | N/A | 47 (14-87) | N/A | |||

| Clinical stage | ||||||

| I | 240 | 22.0 | 45 | 24.1 | 285 | 22.3 |

| II | 694 | 63.6 | 115 | 61.5 | 809 | 63.3 |

| III | 110 | 10.1 | 25 | 13.4 | 135 | 10.6 |

| IV | 48 | 4.4 | 2 | 1.1 | 50 | 3.9 |

| Follow-up, y | ||||||

| Median (interquartile range) | 13.5 (17.5-19.7) | 21.4 (15-27.7) | 14.7 (8.1-21) | |||

| > 5 | 938 | 85.9 | 180 | 96.3 | 1118 | 87.4 |

| > 10 | 696 | 63.7 | 164 | 87.7 | 860 | 67.2 |

| > 15 | 476 | 43.6 | 140 | 74.9 | 616 | 48.2 |

| Treatment | ||||||

| RT alone | 646 | 59.2 | 134 | 71.7 | 780 | 61.0 |

| RT + chemotherapy | 446 | 40.8 | 53 | 28.3 | 499 | 39.0 |

| Median mediastinal dose, Gy (range) | 40 (15-53) | 40 (15-46) | 40 (15-53) | |||

| RT field | ||||||

| Mantle alone | 357 | 32.7 | 36 | 19.3 | 393 | 30.7 |

| MPA | 594 | 54.4 | 119 | 63.6 | 713 | 55.7 |

| TNI | 93 | 8.5 | 29 | 15.5 | 122 | 9.5 |

| Involved field | 48 | 4.4 | 3 | 1.6 | 51 | 4.0 |

| Doxorubicin | ||||||

| No | 872 | 79.8 | 174 | 93.1 | 1046 | 81.8 |

| Yes | 220 | 20.1 | 13 | 6.9 | 233 | 18.2 |

Gy indicates gray; MPA, mantle para-aortic; and TNI, total nodal irradiation.

Patient and treatment characteristics by cardiac complications

| . | CAD (n = 107) . | Arrhythmia (n = 85) . | Valve disease (n = 78) . | Pericardial disease (n = 9) . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n . | % . | n . | % . | n . | % . | n . | % . | |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Female | 27 | 25.2 | 38 | 44.7 | 44 | 56.4 | 4 | 44.4 |

| Male | 80 | 74.8 | 47 | 55.3 | 34 | 43.6 | 5 | 55.6 |

| Age at diagnosis, y | ||||||||

| < 20 | 16 | 14.9 | 12 | 14.1 | 16 | 20.5 | 4 | 44.4 |

| 20-29 | 32 | 29.9 | 27 | 31.8 | 26 | 33.3 | 3 | 33.3 |

| 30-39 | 24 | 22.4 | 14 | 16.5 | 13 | 16.7 | 1 | 11.1 |

| 40-49 | 15 | 14 | 13 | 15.3 | 9 | 11.5 | 1 | 11.1 |

| ≥ 50 | 20 | 18.7 | 19 | 22.3 | 14 | 17.9 | 0 | 0 |

| Median age at cardiac events, y (range) | 48 (20-75) | 50 (14-87) | 49 (23-76) | 44 (18-62) | ||||

| Clinical stage | ||||||||

| I | 28 | 26.2 | 24 | 28.2 | 25 | 32.1 | 0 | 0 |

| II | 59 | 55.1 | 54 | 63.5 | 47 | 60.3 | 8 | 88.9 |

| III | 19 | 17.8 | 5 | 5.9 | 5 | 6.4 | 1 | 11.1 |

| IV | 1 | 0.9 | 2 | 2.4 | 1 | 1.3 | 0 | 0 |

| Follow-up time, y | ||||||||

| > 5 | 102 | 95.3 | 83 | 97.6 | 77 | 98.7 | 9 | 100.0 |

| > 10 | 95 | 88.8 | 75 | 88.2 | 73 | 93.6 | 9 | 100.0 |

| > 15 | 80 | 74.8 | 62 | 72.9 | 64 | 82.1 | 8 | 88.9 |

| Treatment | ||||||||

| RT alone | 82 | 76.6 | 58 | 68.2 | 58 | 74.4 | 7 | 77.8 |

| RT + chemotherapy | 25 | 23.4 | 27 | 31.8 | 20 | 25.6 | 2 | 22.2 |

| Median dose, Gy | 40.00 | 40.00 | 39.90 | 40.00 | ||||

| RT field | ||||||||

| Mantle alone | 15 | 14.0 | 21 | 24.7 | 19 | 24.4 | 1 | 11.1 |

| MPA | 65 | 60.7 | 57 | 67.1 | 50 | 64.1 | 7 | 77.8 |

| TNI | 25 | 23.4 | 6 | 7.1 | 9 | 11.5 | 1 | 11.1 |

| Involved field | 2 | 1.9 | 1 | 1.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Doxorubicin | ||||||||

| No | 104 | 97.2 | 78 | 91.8 | 72 | 92.3 | 9 | 100.0 |

| Yes | 3 | 2.8 | 7 | 8.2 | 6 | 7.7 | 0 | 0 |

| . | CAD (n = 107) . | Arrhythmia (n = 85) . | Valve disease (n = 78) . | Pericardial disease (n = 9) . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n . | % . | n . | % . | n . | % . | n . | % . | |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Female | 27 | 25.2 | 38 | 44.7 | 44 | 56.4 | 4 | 44.4 |

| Male | 80 | 74.8 | 47 | 55.3 | 34 | 43.6 | 5 | 55.6 |

| Age at diagnosis, y | ||||||||

| < 20 | 16 | 14.9 | 12 | 14.1 | 16 | 20.5 | 4 | 44.4 |

| 20-29 | 32 | 29.9 | 27 | 31.8 | 26 | 33.3 | 3 | 33.3 |

| 30-39 | 24 | 22.4 | 14 | 16.5 | 13 | 16.7 | 1 | 11.1 |

| 40-49 | 15 | 14 | 13 | 15.3 | 9 | 11.5 | 1 | 11.1 |

| ≥ 50 | 20 | 18.7 | 19 | 22.3 | 14 | 17.9 | 0 | 0 |

| Median age at cardiac events, y (range) | 48 (20-75) | 50 (14-87) | 49 (23-76) | 44 (18-62) | ||||

| Clinical stage | ||||||||

| I | 28 | 26.2 | 24 | 28.2 | 25 | 32.1 | 0 | 0 |

| II | 59 | 55.1 | 54 | 63.5 | 47 | 60.3 | 8 | 88.9 |

| III | 19 | 17.8 | 5 | 5.9 | 5 | 6.4 | 1 | 11.1 |

| IV | 1 | 0.9 | 2 | 2.4 | 1 | 1.3 | 0 | 0 |

| Follow-up time, y | ||||||||

| > 5 | 102 | 95.3 | 83 | 97.6 | 77 | 98.7 | 9 | 100.0 |

| > 10 | 95 | 88.8 | 75 | 88.2 | 73 | 93.6 | 9 | 100.0 |

| > 15 | 80 | 74.8 | 62 | 72.9 | 64 | 82.1 | 8 | 88.9 |

| Treatment | ||||||||

| RT alone | 82 | 76.6 | 58 | 68.2 | 58 | 74.4 | 7 | 77.8 |

| RT + chemotherapy | 25 | 23.4 | 27 | 31.8 | 20 | 25.6 | 2 | 22.2 |

| Median dose, Gy | 40.00 | 40.00 | 39.90 | 40.00 | ||||

| RT field | ||||||||

| Mantle alone | 15 | 14.0 | 21 | 24.7 | 19 | 24.4 | 1 | 11.1 |

| MPA | 65 | 60.7 | 57 | 67.1 | 50 | 64.1 | 7 | 77.8 |

| TNI | 25 | 23.4 | 6 | 7.1 | 9 | 11.5 | 1 | 11.1 |

| Involved field | 2 | 1.9 | 1 | 1.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Doxorubicin | ||||||||

| No | 104 | 97.2 | 78 | 91.8 | 72 | 92.3 | 9 | 100.0 |

| Yes | 3 | 2.8 | 7 | 8.2 | 6 | 7.7 | 0 | 0 |

Any cardiac events

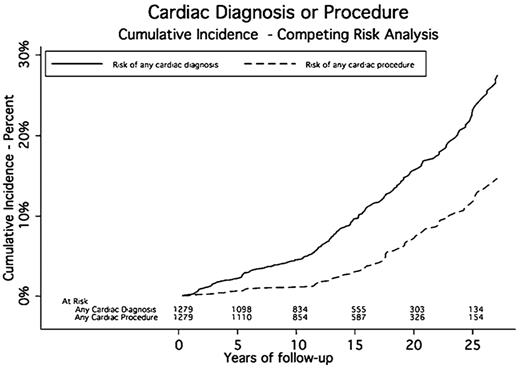

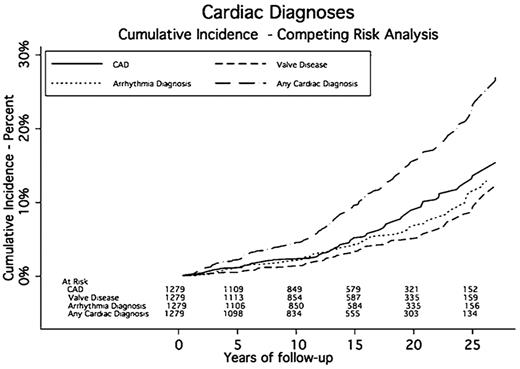

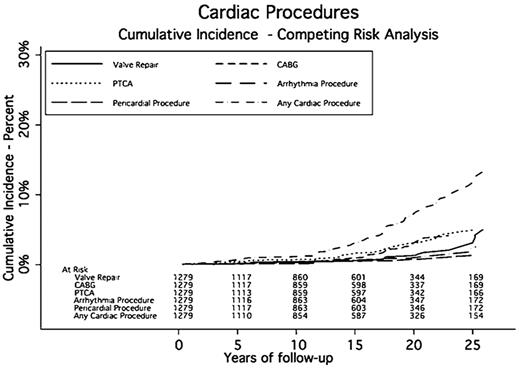

A total of 187 patients experienced 636 cardiac events a median of 14.6 years after RT. The cumulative incidence rates of cardiac events at 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 years were 2.2%, 4.5%, 9.6%, 16%, and 23.2%, respectively. The median midmediastinal dose for patients with a cardiac event was 40 Gy. Eighty-nine patients had one or more cardiac procedures a median of 17.6 years after RT. The cumulative incidence rates for any cardiac procedure at 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 years were 0.7%, 1.2%, 3%, 7.1%, and 11.8%, respectively (Table 3 and Figures 1,Figure 2–3).

CI of cardiac diagnoses and procedures adjusted for competing risk of death

| Event . | Cumulative incidence . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5-year . | 10-year . | 15-year . | 20-year . | 25-year . | |

| Any cardiac diagnosis | 2.2% | 4.5% | 9.6% | 16% | 23.2% |

| CAD | 1.1% | 2.4% | 5.2% | 9.4% | 13.6% |

| Arrythmia | 1.1% | 2.1% | 4.2% | 6.7% | 11.3% |

| Valve disease | 0.5% | 1.4% | 3.3% | 5.0% | 8.7% |

| Any cardiac procedure | 0.7% | 1.2% | 3.0% | 7.1% | 11.8% |

| CABG | 0.1% | 0.4% | 0.9% | 3.0% | 4.1% |

| PTCA | 0.4% | 0.7% | 1.6% | 3% | 5.0% |

| Arrhythmia procedure | 0.2% | 0.3% | 0.6% | 0.9% | 2.2% |

| Valve repair | 0.1% | 0.3% | 0.5% | 1.1% | 2.1% |

| Pericardial surgery | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.4% | 0.6% | 1.3% |

| Event . | Cumulative incidence . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5-year . | 10-year . | 15-year . | 20-year . | 25-year . | |

| Any cardiac diagnosis | 2.2% | 4.5% | 9.6% | 16% | 23.2% |

| CAD | 1.1% | 2.4% | 5.2% | 9.4% | 13.6% |

| Arrythmia | 1.1% | 2.1% | 4.2% | 6.7% | 11.3% |

| Valve disease | 0.5% | 1.4% | 3.3% | 5.0% | 8.7% |

| Any cardiac procedure | 0.7% | 1.2% | 3.0% | 7.1% | 11.8% |

| CABG | 0.1% | 0.4% | 0.9% | 3.0% | 4.1% |

| PTCA | 0.4% | 0.7% | 1.6% | 3% | 5.0% |

| Arrhythmia procedure | 0.2% | 0.3% | 0.6% | 0.9% | 2.2% |

| Valve repair | 0.1% | 0.3% | 0.5% | 1.1% | 2.1% |

| Pericardial surgery | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.4% | 0.6% | 1.3% |

CAD

CAD was diagnosed in 107 patients. The median time to CAD was 15.8 years after RT. The cumulative incidence rates of CAD at 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 years were 1.1%, 2.4%, 5.2%, 9.4%, and 13.6%, respectively. Seventy-six patients had a MI, and 7 of these had 2 MIs, for a total of 83 MIs, 19 of which were fatal.

Sixty-three patients had a revascularization process (CABG or PTCA). Thirty-five patients had CABG, 37 had PTCA, and 9 had both. Three patients had more than 1 CABG and 9 had more than one PTCA; 4 patients had more than 2 procedures. The SIR for CABG was 3.19 (95% CI, 2.83-3.55) compared with the general population. The AER of undergoing CABG was 18.24 per 10 000 person-years of follow-up, or an average of 0.18% per year. The SIR for PTCA was 1.55 (95% CI, 1.39-1.71). The AER for PTCA was 19.29 per 10 000 person-years, or an average of 0.19% per year (Table 4).

Standard incidence ratios and absolute excess risk for cardiac procedures

| Procedure . | Observed (n) . | Expected (n) . | SIR . | 95% CI . | AER* . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CABG | 35 | 10.99 | 3.19 | 2.83-3.55 | 18.24 |

| PTCA | 37 | 23.85 | 1.55 | 1.39-1.71 | 19.29 |

| Valve surgery | 27 | 2.94 | 9.19 | 8.07-10.31 | 14.07 |

| Arrhythmia surgery | 18 | 9.48 | 1.90 | 1.70-2.21 | 9.38 |

| Pericardial surgery | 9 | 0.70 | 12.91 | 10.61-15.21 | 4.69 |

| Procedure . | Observed (n) . | Expected (n) . | SIR . | 95% CI . | AER* . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CABG | 35 | 10.99 | 3.19 | 2.83-3.55 | 18.24 |

| PTCA | 37 | 23.85 | 1.55 | 1.39-1.71 | 19.29 |

| Valve surgery | 27 | 2.94 | 9.19 | 8.07-10.31 | 14.07 |

| Arrhythmia surgery | 18 | 9.48 | 1.90 | 1.70-2.21 | 9.38 |

| Pericardial surgery | 9 | 0.70 | 12.91 | 10.61-15.21 | 4.69 |

Per 10 000 person-years.

Arrhythmia

Arrhythmias were diagnosed in 85 patients. Twenty-nine patients (34.1%) experienced more than one type of rhythm disturbance. Twenty-four patients (28.2%) experienced atrial fibrillation, 26 (30.6%) had supraventricular tachycardia, and 5 (5%) experienced ventricular tachycardia. The median time to an arrhythmia was 14.2 years after RT. The cumulative incidence rates of developing an arrhythmia at 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 years were 1.1%, 2.1%, 4.2%, 6.7%, and 11.3%, respectively. Eighteen patients had a surgical procedure including AICD or pacemaker placement to correct their conduction abnormality. Three patients had AICD placement, and 16 had a pacemaker implanted. The SIR for requiring a pacemaker or AICD was 1.90 (95% CI, 1.70-2.21) compared with the general population. The AER for a pacemaker or AICD was 9.38 per 10 000 person-years, or 0.09% per year.

Valve disease

Seventy-eight patients were diagnosed with clinically significant valvular disease a median of 16.1 years after RT. Of these, 26 had more than one diseased valve resulting in 105 valve abnormalities: 30 aortic (14 stenosis, 16 insufficiency), 51 mitral (1 stenosis and 50 insufficiency), and 24 tricuspid (24 insufficiency). The cumulative incidence rates of developing moderate or severe valve disease at 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 years were 0.5%, 1.4%, 3.3%, 5%, and 8.7%, respectively. One patient had a known history of rheumatic heart disease and one had endocarditis. Of these 78 patients, 27 required valve surgery and 2 required more than 1 valve repair a median of 23.2 years after RT. Aortic valve abnormalities required the most surgical interventions (13 compared with 9 mitral). The SIR for valve surgery was 9.19 (95% CI, 8.07-10.31) compared with the general population. The AER of requiring valve surgery was 14.07 per 10 000 person-years, or 0.14% per year.

Pericardial disease

Pericardial disease was identified in 9 patients a median of 18.3 years after RT. Five patients had pericarditis, 6 had pericardial effusions, and 2 had both. These diagnoses led to 4 pericardial surgeries and 5 pericardiocenteses. The cumulative incidence rates for pericardial disease requiring surgery at 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 years were 0.1%, 0.1%, 0.4%, 0.6%, and 1.3%, respectively. The SIR for pericardial surgery was 12.91 (95% CI, 10.61-15.21) compared with the general population. The AER for a pericardial procedure was 4.69 per 10 000 person-years of follow-up, or 0.05% per year.

Predictive factors

On multivariable Cox regression analysis, after adjusting for confounders including treatment variables, only older age and male sex were predictive factors for undergoing a cardiac procedure. Compared with age < 20 years at diagnosis, age 30-39, 40-49, and ≥ 50 years at diagnosis were significant predictors of cardiac procedures (HR 3.12, HR 6.37, and HR 12.51; P < .01). Males were significantly more likely than females to have a cardiac event (HR 1.84; P = .007). A second multivariable Cox regression analysis assessed predictive factors for developing any cardiac event and the associative factors were the same as those for cardiac procedures (Table 5).

Cox multivariable regression analysis for all cardiac diagnoses and procedures

| . | Cardiac diagnoses . | Cardiac procedures . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR . | 95% CI . | P . | HR . | 95% CI . | P . | |

| Age, y | ||||||

| (20-29 vs < 20) | 1.48 | 0.98-2.24 | .065 | 1.29 | 0.71-2.35 | .398 |

| (30-39 vs < 20) | 2.63 | 1.64-4.21 | < .001 | 3.12 | 1.64-5.94 | .001 |

| (40-49 vs < 20) | 7.70 | 4.57-12.97 | < .001 | 6.37 | 2.89-14.08 | < .001 |

| (> 50 vs < 20) | 13.12 | 7.87-21.89 | < .001 | 12.51 | 5.99-26.11 | < .001 |

| Sex (male vs female) | 1.56 | 1.16-2.11 | .003 | 1.84 | 1.18-2.86 | .007 |

| Mediastinal dose (≥ 36 Gy vs < 36 Gy) | 0.93 | 0.50-1.73 | .812 | 1.40 | 0.44-4.49 | .568 |

| Any chemotherapy (yes vs no) | 1.07 | 0.77-1.48 | .7 | 1.00 | 0.61-1.66 | .988 |

| . | Cardiac diagnoses . | Cardiac procedures . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR . | 95% CI . | P . | HR . | 95% CI . | P . | |

| Age, y | ||||||

| (20-29 vs < 20) | 1.48 | 0.98-2.24 | .065 | 1.29 | 0.71-2.35 | .398 |

| (30-39 vs < 20) | 2.63 | 1.64-4.21 | < .001 | 3.12 | 1.64-5.94 | .001 |

| (40-49 vs < 20) | 7.70 | 4.57-12.97 | < .001 | 6.37 | 2.89-14.08 | < .001 |

| (> 50 vs < 20) | 13.12 | 7.87-21.89 | < .001 | 12.51 | 5.99-26.11 | < .001 |

| Sex (male vs female) | 1.56 | 1.16-2.11 | .003 | 1.84 | 1.18-2.86 | .007 |

| Mediastinal dose (≥ 36 Gy vs < 36 Gy) | 0.93 | 0.50-1.73 | .812 | 1.40 | 0.44-4.49 | .568 |

| Any chemotherapy (yes vs no) | 1.07 | 0.77-1.48 | .7 | 1.00 | 0.61-1.66 | .988 |

On Poisson regression of SIRs (Table 6), there were statistically significant trends for increasing excess risk for having cardiac disease requiring surgical intervention for those in the younger age groups at treatment (P < .001) compared with age-matched patients in the general population who did not receive radiotherapy. The greatest excess risk was seen in those irradiated before the age of 20 with an SIR of 7.21 (95% CI 4.54-11.44). With each decade increase in age at presentation (20-29, 30-39, and 40-49 compared with age < 20), radiation continued to contribute excess risk but to a lesser degree, with SIRs ranging from 2.61-1.22. Irradiation at ages > 50 years did not contribute excessively to cardiac procedure rates. There was no clear difference between men and women in the risk radiation posed for requiring a cardiac intervention (P = .423).

Poisson multivariate regression of SIRs for cardiac procedures

| . | SIR . | SIR 95% CI . | IRR . | IRR 95% CI . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | |||||

| < 2 | 7.21 | 4.54-11.44 | 1 | ||

| 20-29 | 2.61 | 1.79-3.80 | 0.35 | 0.19-0.64 | .001 |

| 30-39 | 2.07 | 1.34-3.22 | 0.28 | 0.15-0.53 | < .001 |

| 40-49 | 1.22 | 0.66-2.27 | 0.17 | 0.08-0.36 | < .001 |

| ≥ 50 | 0.87 | 0.51-1.46 | 0.11 | 0.05-0.23 | < .001 |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 2.12 | 1.48-3.03 | 1 | ||

| Male | 1.80 | 1.37-2.33 | 0.83 | 0.53-1.30 | .42 |

| Mediastinal dose | |||||

| < 36 Gy | 0.91 | 0.29-2.83 | 1 | ||

| ≥ 36 Gy | 2.06 | 1.66-2.56 | 1.48 | 0.46-4.81 | .51 |

| Chemotherapy | |||||

| No | 1.98 | 1.56-2.51 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 1.67 | 1.10-2.57 | 0.86 | 0.52-1.41 | .55 |

| . | SIR . | SIR 95% CI . | IRR . | IRR 95% CI . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | |||||

| < 2 | 7.21 | 4.54-11.44 | 1 | ||

| 20-29 | 2.61 | 1.79-3.80 | 0.35 | 0.19-0.64 | .001 |

| 30-39 | 2.07 | 1.34-3.22 | 0.28 | 0.15-0.53 | < .001 |

| 40-49 | 1.22 | 0.66-2.27 | 0.17 | 0.08-0.36 | < .001 |

| ≥ 50 | 0.87 | 0.51-1.46 | 0.11 | 0.05-0.23 | < .001 |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 2.12 | 1.48-3.03 | 1 | ||

| Male | 1.80 | 1.37-2.33 | 0.83 | 0.53-1.30 | .42 |

| Mediastinal dose | |||||

| < 36 Gy | 0.91 | 0.29-2.83 | 1 | ||

| ≥ 36 Gy | 2.06 | 1.66-2.56 | 1.48 | 0.46-4.81 | .51 |

| Chemotherapy | |||||

| No | 1.98 | 1.56-2.51 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 1.67 | 1.10-2.57 | 0.86 | 0.52-1.41 | .55 |

Discussion

In this study, the long-term risk of cardiac disease after mediastinal RT for HL was analyzed for 1279 patients treated over almost 30 years at a single institution with 19 184 person-years of follow-up. One hundred eighty-seven patients experienced 636 cardiac events leading to 129 surgical interventions. Compared with the general population, there was a 3.2-fold increased risk of requiring a CABG, a 1.6-fold risk of needing PTCA, and a 9.2-fold risk of requiring valve surgery. This translates to 18, 19, and 14 excess CABG, PTCA, and valve surgeries per 10 000 person-years of follow-up, respectively. There was a 1.9-fold risk of surgery to correct a conduction abnormality, or 9 excess surgeries per 10 000 person-years. Although the SIR of requiring pericardial surgery was the highest at 12.9, this only represented 5 excess cases per 10 000 person-years of follow-up.

Several studies have reported increased cardiac mortality relative to the general population,5,7-12 although few compared clinically significant cardiac morbidity.22-24 Aleman et al23 followed 1474 patients for a median of 18.7 years and found an increased risk of congestive heart failure (CHF), MI, and angina pectoris (SIRs = 4.9, 3.6, and 4.1, respectively). Myrehaug et al24 found a 1.9-fold risk of hospitalization for cardiac diagnoses including MI/ischemic heart disease and coronary revascularization among HL survivors. Hull et al22 restricted their relative-risk analysis for 415 HL patients to procedures including CABG, PTCA, and valve repair (relative risk [RR] = 2.42, 0.86, and 8.42, respectively). In our study, we report the frequency of cardiac diagnoses and limit our excess-risk analysis (SIR and AER) to cardiac procedures. The rationale was that cardiac procedures represent a more objective measure of clinically significant cardiac disease than do specific cardiac diagnoses, whose subjective nature cannot be controlled for when analyzing general population rates. In addition to contributing to the reports of increased rates of CABG, PTCA, and valve repair, we provide what we believe to be the first excess-risk analysis for conduction abnormalities and pericardial interventions.

Previous studies found that compared with the normal population, patients treated for HL at a younger age are at higher risk of cardiac disease. Hancock et al29 found that patients younger than 20 at HL treatment had a significantly higher RR of death from both acute MI and other cardiac disease, and Aleman et al23 found that the SIRs of myocardial infarction, angina pectoris, and CHF were higher in patients treated before age 25. However, other studies, when using actuarial risk as an end point, have shown older age to be significantly associated with increased risk of cardiac morbidity.15,24 This apparent discrepancy in the relationship between age at treatment and cardiac risk is likely related to the increasing background risk of cardiac disease and the greater likelihood of having other cardiac risk factors with increasing age, as highlighted by our results. Within the same cohort, we found a significantly increasing risk of cardiac disease with increasing age at treatment while also showing a significant association between young age at treatment and cardiac risk compared with the normal population. Interestingly, those treated at age > 50 had a slightly decreased risk of cardiac disease requiring intervention, compared with the normal population. This finding may potentially be explained by closer cardiac surveillance and risk-factor modification, altering their subsequent need for cardiac intervention in the HL survivor population.

Similar to other studies,15,22 on Cox regression multivariable analysis we found male sex to be an independent risk factor for cardiac events. Glanzmann et al15 reported a significantly elevated RR of fatal MI and sudden death among males (RR, 5.3 [95% CI, 2.1-10.9]) but not among female survivors (RR, 1.7 [95% CI, 0.04-9.6]), and further noted that a higher proportion of males had known cardiovascular risk factors, which may explain the observed differences in risk by sex. While men in our study experienced increased rates of cardiac disease and cardiac procedures following radiation relative to women, Poisson regression analysis indicated that radiation itself did not contribute significantly excess risk in men compared with women.

Recent data highlight the relationship between chemotherapy (in particular, doxorubicin) and cardiac toxicity in HL patients.5,30,31 Other studies have shown that the doxorubicin cumulative dose is associated with cardiotoxicity risk.30,32 The contribution of doxorubicin to the risk of cardiac disease when administered with mediastinal RT has been evaluated by several investigators. Aleman et al23 showed that on multivariable analysis, the addition of anthracycline-based chemotherapy to RT was associated with a significantly increased risk of CHF (HR, 2.81 [95% CI, 1.44-5.49]) and valvular disease (HR = 2.10 [95% CI, 1.27-3.48]). Myrehaug et al24 reported that the RR of all cardiac events was highest among patients who received both doxorubicin and mediastinal irradiation (RR, 2.8; [95% CI, 1.3-4.2]. The RR was lower but remained significantly increased for patients given mediastinal irradiation alone (RR, 1.9 [95% CI 1.0-4.2]. Swerdlow et al5 found that the RR of cardiac mortality was 12.1 (95% CI, 2.5-35.3) in patients treated with ABVD and mediastinal irradiation. Remarkably, the RR of cardiac mortality among patients who received ABVD without mediastinal irradiation was lower but remained significantly elevated at 7.8 (95% CI, 1.6-22.7). In our study, after adjusting for radiation dose and other factors, chemotherapy did not significantly influence the risk of cardiac disease. However, only 20% of patients who received chemotherapy had doxorubicin. Furthermore, patients who received doxorubicin were treated in the more recent era, and therefore have shorter follow-up and likely received modern conformal radiation treatments, with lower radiation exposure to the heart. We are therefore limited in our ability to meaningfully assess the contribution of chemotherapy, specifically doxorubicin, to the risk of cardiac complications.

This study is subject to several limitations due to its retrospective nature. Most patients were treated before the advent of computed-tomography planning and received radiation doses higher than the current standard for HL (89.4% received ≥ 36 Gy). Two-thirds were treated with extended-field RT, and it has previously been shown that the field-matching technique is associated with a significantly increased risk of CAD.22 Most of the remaining patients received mantle irradiation, which has a lower inferior border than a typical involved field to the mediastinum and thus includes more heart in the field. Our findings are therefore likely not applicable to patients treated more recently. Nevertheless, the data are important given the large number of long-term survivors who are now in need of risk counseling and appropriate follow-up. The relatively narrow dose prescription range and the lack of dose information to specific cardiac structures also limited our ability to meaningfully assess the effect of radiation dose on cardiac risks, although prior studies have demonstrated that the risk is dose-related.4,22,29 In addition, we could not obtain complete data on cardiac risk factors including hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes, and smoking for the entire cohort. Therefore, the contribution of such factors to cardiac risk could not be assessed. Finally, in this study, the median time to any cardiac event was 14.6 years and the median time to any cardiac procedure was 17.6 years. However, the median follow-up for all patients was only 14.7 years with one-third of the cohort having < 10 years of follow-up. Although the length of follow-up in this study is comparable with that of other studies assessing radiation-associated cardiac morbidity,22,23 additional follow-up time is clearly needed to fully evaluate the impact of mediastinal irradiation on the long-term risk of cardiac disease.

In this study, we present data on the cumulative incidence and relative risk of cardiac disease after curative treatment for HL. From these incidence curves, we have shown that the diagnosis of cardiac disease and the use of cardiac procedures occurs 10 years or greater after treatment. This suggests that these effects are slow to develop and may be partially preventable with the control of other cardiac risk factors in the time before the development of overt cardiac disease. It also suggests that routine cardiac surveillance and screening may be of limited value before 10 years after initial treatment. The type of screening, the need to repeat it and at what interval, and whether all irradiated patients should be screened needs to be determined.

This work was presented in part at the 49th annual meeting of the American Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology (ASTRO), October 30, 2007, Los Angeles, CA.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: S.L.G. designed research, performed research, collected data, analyzed and interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript; J.B.Y. performed statistical analysis; J.F.S., A.L., K.J.M., and M.A.S. collected data; B.S. analyzed and interpreted data; M.H.C. designed research; and P.M.M. and A.K.N. designed research and analyzed and interpreted data.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

The current affiliation for S.G. is Department of Therapeutic Radiology, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT. The current affiliation for J.F.S. is Department of Radiation Oncology, Helen F. Graham Cancer Center, Newark, DE.

Correspondence: Andrea K. Ng, Department of Radiation Oncology, Brigham and Women's Hospital, 75 Francis St, Boston, MA 02115; e-mail: ang@lroc.harvard.edu.