Abstract

Hypersensitivity reactions limit the use of the antileukemic enzyme asparaginase (ASE). We evaluated Ab levels against Escherichia coli ASE and ASE activity in 1221 serum samples from 329 patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia who had received ASE treatment according to the ALL-BFM 2000 or the ALL-REZ BFM 2002 protocol for primary or relapsed disease. ASE activity during first-line treatment with native E coli ASE and second-line treatment with pegylated E coli ASE was inversely related to anti–E coli ASE Ab levels (P < .0001; Spearman rank order correlation). An effect on ASE activity during second-line treatment with pegylated E coli ASE was, however, only observed when anti–E coli ASE Ab levels were high (> 200 AU/mL). In the presence of moderate or intermediate Ab levels (6.25-200 AU/mL) the switch from native to pegylated E coli ASE resulted in a significant increase of ASE activity above the threshold of 100 U/L (P < .05). Erwinia chrysanthemi ASE activity was not correlated with anti–E coli ASE Ab levels. Erwinia ASE was found to be the best ASE alternative if Ab levels against E coli ASE exceed 200 AU/mL. This retrospective analysis is the first to describe the relationship between the level of anti–E coli ASE Abs and serum activity of pegylated E coli ASE used second-line after native E coli ASE. These studies are registered at http://clinicaltrials.org as NTC00430118 and NCT00114348.

Introduction

For more than 3 decades, the antileukemic enzyme asparaginase (ASE) has been successfully used within the acute lymphoblastic leukemia Berlin-Frankfurt-Münster (ALL-BFM) trials for the treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). ASE hydrolyzes the amino acid asparagine to aspartic acid and ammonia. When applied intravenously or intramuscularly, it deprives extracellular fluids of asparagine, which starves asparagine-dependent leukemic blasts to death. Allergic reactions to the bacterial protein are among the most common side effects of ASE therapy and limit further ASE treatment. Clinical symptoms range from light local reactions such as urticaria to systemic reactions such as bronchospasm and anaphylactic shock. The investigators of some trials report an incidence of 35%.1-3 Allergic reactions are associated with the appearance of Abs, which were reported to increase ASE clearance and to reduce or even neutralize the catalytic activity of ASE.4,5 In consequence, even if clinical symptoms are mild or manageable by supportive care, continuing the ASE treatment with the same ASE preparation is not advisable.

Three different ASE preparations are currently in clinical use. Two preparations are derived from Escherichia coli strains; one is used in the native form and the other in the pegylated form. The third preparation is derived from Erwinia chrysanthemi. Polyethylene glycol, covalently bound to native E coli ASE, shields the bacterial protein and reduces its immunogenicity.6,7 Thus, good tolerability was reported for pegylated E coli ASE applied after allergic reactions to native E coli ASE.8-10 Because E chrysanthemi and E coli ASE share only 70% amino acid homology, cross-reactivity with native E coli–derived ASE is low.11 In the case of allergic reactions to ASE, the treatment can usually be continued by switching to another ASE preparation. This procedure was implemented in the ALL-BFM 2000 and ALL-REZ (ie, acute lymphoblastic leukemia relapse) BFM 2002 trials, in which investigators used native E coli ASE for first-line treatment; in case of allergic reactions, pegylated E coli ASE was used as a substitute second-line treatment and Erwinia ASE as a third-line treatment. When a patient had an allergic reaction to Erwinia ASE, the ASE treatment usually had to be stopped.

In addition to overt allergic reactions to ASE, immunologic reactions without clinical symptoms of hypersensitivity, so-called “silent inactivation” of ASE, have been reported.8,12 These were characterized by insufficient ASE activity because of inactivating Abs. Because silent inactivation can be detected by measuring the ASE activity in the serum, investigators in the ALL-BFM trials implemented monitoring of ASE activity more than a decade ago. The long history of ASE drug monitoring within the ALL-BFM trials notwithstanding, anti–E coli ASE Abs have not been monitored within these trials. We report on the Ab monitoring of 1221 samples from 329 patients; the samples had previously been analyzed for asparaginase activity as part of the ASE drug-monitoring program provided within the ALL-BFM 2000 and ALL-REZ BFM 2002 trials.

Methods

Patients

From January 1, 2002 to February 12, 2008, a total of 4338 samples from 965 patients were analyzed for ASE activity. The patients were treated according to the ALL-BFM 2000 and the ALL-REZ BFM 2002 protocols. The analysis of ASE activity was part of an optional trial-associated monitoring program provided by the Department of Pediatric Hematology and Oncology, University Children's Hospital of Muenster. Both of the trials are registered at the US National Institutes of Health website http://clinicaltrials.gov, which lists the ALL-BFM 2000 trial entitled “Combination chemotherapy based on risk of relapse in treating young patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia” under protocol identification number NCT00430118 and “ALL-REZ BFM 2002: multi-center study for children with relapsed acute lymphoblastic leukemia” under protocol identification number NCT00114348.

Ethical approval for these trials was obtained locally by each participating organization. The ALL-BFM 2000 study protocol already provided for the determination of ASE Ab levels along with the optional monitoring of ASE activity. Patients of the ALL-REZ BFM 2002 trial and/or their guardians provided their written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki to participate in the clinical trial and for the collection of material for diagnostic and further scientific investigations, in accordance with the regulations of the local ethics committee.

The majority of the samples (2251) were collected after the administration of native E coli ASE; 1552 samples were obtained after the administration of pegylated E coli and 535 samples after the administration of Erwinia ASE. Blood samples were taken within 3 days after the administration of native E coli ASE, within 2 days after Erwinia ASE, and within 14 days after pegylated E coli ASE. Of these samples, 1221 were selected for the analysis of anti–E coli ASE Ab. Because the monitoring of ASE activity was provided on an optional basis, not all patients of the ALL-BFM 2000 and the ALL-REZ BFM 2002 trials were invariably monitored for ASE activity. Moreover, not all ASE administrations were invariably monitored for ASE activity.

To evaluate the impact of anti–E coli ASE Ab levels on ASE activity, we selected comparable numbers of samples taken after the administration of native E coli (403 samples), pegylated E coli (453 samples), or Erwinia ASE (365 samples) for anti–E coli ASE Ab analysis. Of the serum samples analyzed, 776 originated from 236 patients (median age, 7.1 years; range, 1.3-17.4 years) treated according to the ALL-BFM 2000 protocol and 445 from 101 patients (age median, 10.4 years; range, 2.3-20.7 years) treated according to ALL-REZ BFM 2002.13,14 In 8 patients, the samples for this analysis were collected both under ALL-BFM 2000 and, after relapse, ALL-REZ BFM 2002 treatment. Because pegylated E coli ASE was used a second-line and E chrysanthemi as a third-line treatment, the respective samples were supposedly taken after an allergic reaction to native E coli ASE. The selection of samples collected after the administration of native E coli ASE included both those from patients who showed no signs of allergic reactions and tolerated native E coli ASE throughout treatment and those from patients who experienced allergic reactions to native E coli ASE. A detailed list of samples analyzed during first-, second-, and/or third-line ASE treatment is given in supplemental Table 1 (available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

ASE treatment

The ALL-BFM 2000 trial protocol started ASE treatment during induction with 8 infusions of native E coli ASE administered at a dose of 5000 U/m2 every third day (protocol I).13 The reinduction elements, that is, protocols II and III, contained 4 infusions each of 10 000 U/m2 native E coli ASE at 3-day intervals. The intensified consolidation elements for high-risk patients (ie, HR courses) contained 2 doses each of 25 000 U/m2 native E coli ASE administered at 5-day intervals.

The composition of the reinduction treatment was dependent on the risk group and, during the randomized phase of the trial, also on the randomization arm: Standard-risk patients received protocol III or protocol II, medium-risk patients had protocol II or 2 times protocol III, and high-risk patients were given 6 HR courses followed by protocol II or 3 HR courses followed by 3 times protocol III. In case of allergic reactions, 4 doses of native E coli ASE were replaced by one dose of 1000 U/m2 pegylated E coli ASE. When the allergic reaction was to pegylated E coli ASE, 6 doses of 10 000 U/m2Erwinia ASE, administered intravenously every second day, replaced 4 infusions of native E coli ASE.

In the ALL-REZ BFM 2002 protocol, native E coli ASE was administered at a dose of 10 000 U/m2. In case of allergic reactions to native E coli ASE, one dose of 1000 U/m2 pegylated E coli ASE replaced one infusion of 10 000 U/m2 native E coli ASE in those treatment elements where only one E coli ASE infusion was prescribed (F1, F2, R1, R2) or it replaced 2 infusions of 10 000 U/m2 native E coli ASE when the treatment plan provided for 4 infusions of 10 000 U/m2 native E coli ASE at 5-day intervals (protocol II-IDA). Three doses of 10 000 U/m2Erwinia ASE every second day replaced ASE in F1, F2, R1, and R2 and 10 doses of 10 000 U/m2Erwinia ASE every second day replaced 2 doses of pegylated E coli ASE in protocol II-IDA.14

Determination of ASE activity in human serum

ASE activity was analyzed with the indo-oxin method as described elsewhere.15 Depending on the incubation time, this method allows the quantification of ASE activity in undiluted human serum at concentrations from 5 U/L to 1000 U/L. Because of dilution linearity, it was possible to quantify ASE activity values up to 20 000 U/L. Because a serum ASE activity of 100 U/L is considered sufficient for asparagine depletion from serum and CSF, dosing schedules were designed to result in ASE activities > 100 U/L for definite time intervals.16 However, studies in which authors monitored ASE activity along with asparagine depletion indicated that even lower ASE activities might be sufficient to deplete serum and CSF of asparagine.17,18 In consequence, and considering that the bioanalytical method tolerated variation coefficients of 15% greater than the limit of quantification, we also examined serum samples with activity values < 50 U/L 3 days after the administration of native E coli ASE, 2 days after the administration of Erwinia ASE, and 14 days after the administration of pegylated E coli ASE, to describe more distinctly those samples where ASE activity values are too low.

Determination of anti–E coli ASE Abs

Abs against E coli ASE were measured by an indirect ELISA that was developed and validated at medac GmbH by the use of native E coli ASE immobilized to the solid phase. The serum samples and 6 calibrators, 1 negative and 2 positive controls, were diluted to 1:1000. Calibrators were prepared by pooling 3 highly positive anti–E coli ASE Ab patient sera and subsequent serial dilution of this pool. Positive controls were made of only one patient sample each, whereas the negative control consisted of one nonreactive blood donor serum.

The presence of specific IgG/Ms was revealed by horseradish peroxidase-labeled goat anti–human IgG/M antiserum by the use of a chromogen/substrate solution containing tetramethylbenzidine/peroxide. The chromogenic reaction was stopped with sulfuric acid before photometric reading at 450 nm.

A calibration curve was generated by plotting optical densities (ODs) of the calibrators against corresponding, arbitrarily defined concentration units (AU/mL) followed by appropriate curve fitting. The measuring range was defined by the lowest calibrator (6.25 AU/mL, OD specification < 0.2) and the greatest calibrator (200 AU/mL, OD specification > 1.6). Sample concentrations were calculated via this calibration curve. Samples above the measuring range were retested in greater dilutions.

Each reactive sample also was tested for unspecific binding to the plate by retesting on nonantigen-coated plates. We observed a moderate unspecific reaction in 12 serum samples, which were characterized by Ab levels > 200 AU/mL. These samples, ie, 7 samples taken after Erwinia ASE and 5 samples taken after pegylated E coli ASE, were excluded from further analysis because of unspecific binding.

The anti–E coli ASE Ab levels were classified into 4 groups according to arbitrary units. Serum samples with Ab levels < 6.25 AU/mL were classified as Ab negative (Ab−). Samples with Ab levels > 6.25 AU/mL were graded Ab positive and further classified according to their AU/mL, ie, moderately positive: 6.25-20 AU/mL (Ab+), intermediately positive: 20-200 AU/mL (Ab++), and highly positive: > 200 AU/mL (Ab+++).

Statistics

Between 1 and 17 samples per patient were analyzed (median, 2). The relationship between Ab results and ASE activity was analyzed descriptively with the use of contingency tables, pie charts, and the Spearman correlation coefficient.

Inductive statistical analyses were performed to evaluate the effect of the ASE preparation and the Ab level on ASE activity. A generalized linear model with a binary outcome variable was established, ie, ASE activity > 50 versus < 50 U/L. We included the independent factors ASE preparation (native E coli ASE, pegylated E coli ASE, Erwinia ASE) and E coli ASE Ab level (Ab−: < 6.25 AU/mL; moderately Ab positive (Ab+): 6.25-20 AU/mL; intermediately Ab positive (Ab++): 20-200 AU/mL; highly Ab positive (Ab+++): > 200 AU/mL) as well as an interaction term of both factors. To account for clusters of multiple, correlated observations of individual subjects, the model was fitted by generalized estimating equations with an exchangeable working correlation. Linear contrasts were evaluated by Wald type significance tests. All statistical analyses are intended to be exploratory and not confirmatory. P values of < .05 were considered to indicate significance. No adjustment for multiple testing was performed. Statistical analyses were performed by use of the SigmaPlot 9.0 software (Systat Software Inc) and SAS (Version 9.2 for Windows; SAS Institute Inc).

In addition, to determine the relationship between the Ab test results (Ab negative: < 6.25 AU/mL, Ab positive: > 6.25 U/mL) and findings in samples taken after clinical signs of allergy, we performed the Fisher exact test and exact χ2 test by using the SPSS software (Version PASW Statistics 18 for Windows).

Results

Within this study, a total of 1221 serum samples from 329 patients treated according to the ALL-BFM 2000 and/or the ALL-REZ BFM 2002 protocol were analyzed for ASE activity and Abs against E coli ASE. Except for 12 samples, which were not evaluable because of unspecific binding, Abs against E coli ASE were detected in 652 samples. Ab levels ranged from 6.29 AU/mL to 47 261 AU/mL.

Ab levels against E coli ASE

Abs against E coli ASE were detected in 8.7% of serum samples (35/403 samples) taken after the first-line administration of native E coli ASE (25.6% of patients; 30/117 patients). Ab levels ranged from 6.29 to 23 664 AU/mL. Of 164 samples from 48 patients who had no clinical signs of allergic reactions and no silent inactivation and who did not receive second-line treatment with pegylated ASE, only 1 tested positive for Abs against E coli ASE. The anti–E coli ASE Ab level in this sample was moderately high at 12.7 AU/mL. Such moderate reactivity (< 20 AU/mL) was also found in a few sera of blood donors during assay validation. When regarding patients with clinically overt allergic reactions to native E coli ASE, we found anti–E coli ASE Abs in 81 of 99 patients (82%). The detection of Abs against E coli ASE was significantly associated with clinically manifest allergic reactions to E coli ASE (P < .0001, the Fisher exact test).

Where treatment had been switched to second-line pegylated E coli ASE, an allergic reaction to native E coli ASE was confirmed or at least suspected. Here the proportion of Ab-positive samples increased to 73.0% (327/448 samples, ie, 87.4% of patients [188/215]). A total of 85.2% of samples (202/237) from patients treated according to the ALL-BFM 2000 protocol were Ab posi-tive (90.7% of patients [136/150]), whereas 59.2% of samples (125/211 samples) taken during relapse treatment were Ab positive (77.5% of patients; [55/71]).

After a treatment switch to third-line Erwinia ASE, the rate of Ab-positive samples further increased to 81.0% of samples (290/358 samples; 85.4% of patients [70/82]). A total of 86.7% of samples (117/135 samples) collected during ALL-BFM 2000 (94.9% of patients [37/39]) and 77.6% of samples (173/223 samples) taken during relapse treatment (77.3% of patients [34/44]) were Ab positive.

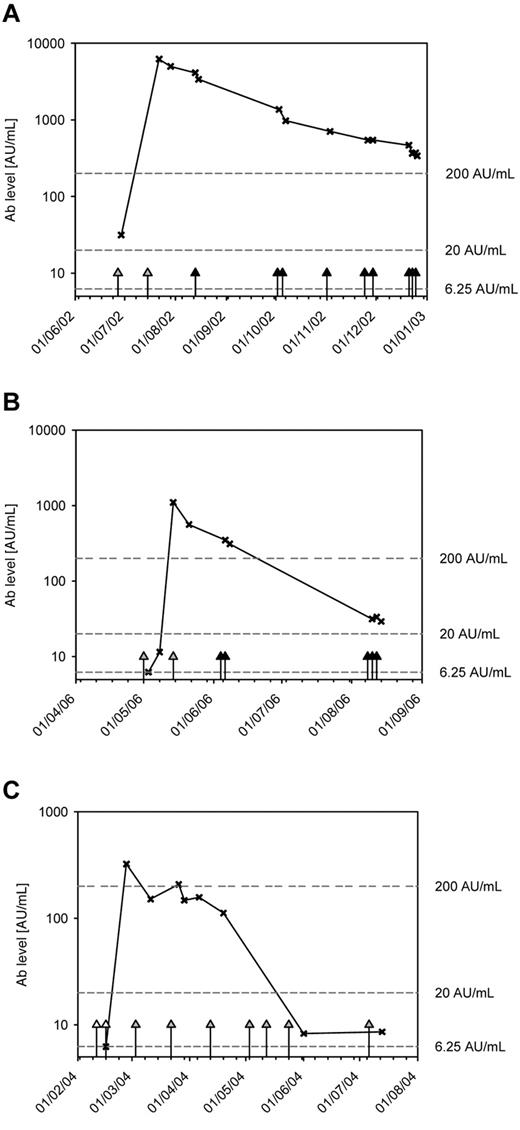

Under second-line treatment with pegylated E coli ASE, both increasing as well as decreasing counts of Abs against E coli ASE were observed, whereas third-line treatment with Erwinia ASE was associated with a gradual decrease of Abs against E coli ASE. Figure 1 shows, by way of example, the curves for 3 patients.

Time course of Ab (×) levels in 3 patients with relapsed ALL who received native and/or pegylated E coli ASE followed by Erwinia ASE because of allergic reactions to E coli ASE. White triangles represent the administrations of native E coli ASE; gray triangles, the administration of pegylated E coli; and black triangles, the administration of Erwinia ASE.

Time course of Ab (×) levels in 3 patients with relapsed ALL who received native and/or pegylated E coli ASE followed by Erwinia ASE because of allergic reactions to E coli ASE. White triangles represent the administrations of native E coli ASE; gray triangles, the administration of pegylated E coli; and black triangles, the administration of Erwinia ASE.

ASE activity

Sufficient ASE activity after native E coli ASE, that is, > 100 U/L within 3 days after administration, was determined in 85.1% of serum samples (343/403 samples). In samples taken after the administration of pegylated E coli ASE, sufficient ASE activity, that is, > 100 U/L within 14 days after administration, was apparent 65.1% of samples (295/453 samples); after Erwinia ASE, > 100 U/L ASE activity was reached in 55.1% of samples (201/365 samples) within 2 days after the administration. ASE activity was < 50 U/L in 7.94% of samples (32/403 samples) taken within 3 days after the administration of native E coli ASE, in 31.6% of samples (143/453 samples) collected within 14 days after administration of pegylated E coli ASE and in 19.7% of samples (72/365 samples) taken within 2 days after the administration of Erwinia ASE. Borderline ASE activity between 50 U/L and 100 U/L was determined in 6.95% of samples (28/403 samples) taken after the administration of native E coli ASE, 3.31% of samples (15/453 samples) taken after pegylated E coli ASE, and 25.2% of samples (92/365 samples) collected after Erwinia ASE.

Correlation between ASE activity and anti–E coli ASE Ab levels

After the administration of native E coli ASE, the proportion of samples with insufficient or borderline ASE activity gradually increased as Ab levels in the samples increased and correlated inversely with the Ab levels against E coli ASE (r2 = −0.457; P < .0001; n = 403; Spearman Rank order correlation analysis). After the administration of native E coli ASE, actually no anti–E coli ASE Ab reactivity was detectable in 96.2% of samples (357/371 samples) with an ASE activity > 50 U/L, which underlines the good specificity of the test; this finding also held true for ASE activity values > 100 U/L (330/343 samples). If samples were tested negative for anti–E coli ASE Abs, an enzyme activity > 50 U/L was assessed in 97.0% of cases (357/368 samples) and > 100 U/L in 89.7% of cases (330/368 samples = negative predictive value). If the Ab test was positive, the chance of having a low ASE activity < 50 U/L was already 11-fold increased in moderately Ab-positive samples (6.25-20 AU/mL) and increased 256-fold in samples with Ab levels > 200 AU/mL compared with Ab-negative samples < 6.25 AU/mL (Table 1).

Odds of ASE activity < 50 U/L under different ASE preparations at different Ab levels against E coli ASE. Results were generated applying a generalized linear model that was fitted by generalized estimating equations (GEE)

| ASE preparation . | Ab level* . | OR (activity < 50 U/L) . | Confidence limits . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Native E coli ASE | b+ vs Ab− | 11.03 | 2.26-53.76 | .0030 |

| Ab++ vs Ab− | 61.73 | 16.98-227.27 | < .0001 | |

| Ab+++ vs Ab− | 256.41 | 26.11-2500 | < .0001 | |

| Pegylated E coli ASE | Ab+ vs Ab− | 6.36 | 2.00-20.16 | .6511 |

| Ab++ vs Ab− | 72.99 | 23.31-227.27 | .0017 | |

| Ab+++ vs Ab− | < .0001 | |||

| Erwinia ASE | Ab+ vs Ab− | .2797 | ||

| Ab++ vs Ab− | .2209 | |||

| Ab+++ vs Ab− | .2123 |

| ASE preparation . | Ab level* . | OR (activity < 50 U/L) . | Confidence limits . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Native E coli ASE | b+ vs Ab− | 11.03 | 2.26-53.76 | .0030 |

| Ab++ vs Ab− | 61.73 | 16.98-227.27 | < .0001 | |

| Ab+++ vs Ab− | 256.41 | 26.11-2500 | < .0001 | |

| Pegylated E coli ASE | Ab+ vs Ab− | 6.36 | 2.00-20.16 | .6511 |

| Ab++ vs Ab− | 72.99 | 23.31-227.27 | .0017 | |

| Ab+++ vs Ab− | < .0001 | |||

| Erwinia ASE | Ab+ vs Ab− | .2797 | ||

| Ab++ vs Ab− | .2209 | |||

| Ab+++ vs Ab− | .2123 |

Results were generated applying a generalized linear model that was fitted by generalized estimating equations.

ASE indicates antileukemic enzyme asparaginase; and OR, odds ratio.

Ab−: < 6.25 AU/mL; Ab+: 6.25-20 AU/mL; Ab++: 20-200 AU/mL; Ab+++: > 200 U/mL.

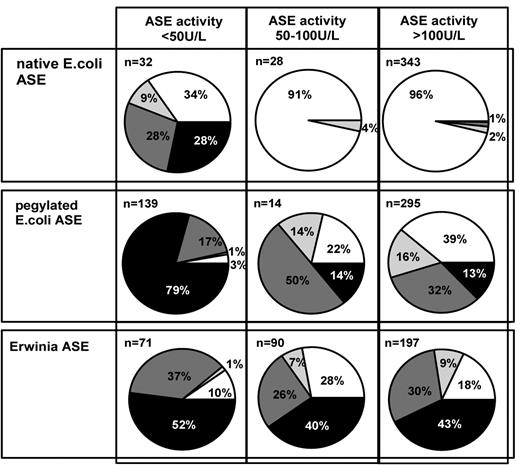

An inverse association of ASE activity with anti–E coli ASE Abs was also observed after the administration of pegylated E coli ASE (r2 = −0.612; P < .0001; n = 448, Spearman rank order correlation analysis), which indicated that Abs against native E coli ASE impaired the catalytic activity of pegylated E coli ASE as well. When pegylated E coli ASE was given, the rate of Ab-negative samples among all samples with insufficient ASE activity was low (Figure 2). With the chosen cut-off value of 6.25 AU/mL, the test picked up 97.1% of all samples (135/139 samples) with low pegylated E coli ASE activity values < 50 U/L (97.3% of patients [109/112]) with low activity (< 50 U/L of pegylated E coli ASE) proving good sensitivity of the test.

Pie charts representing the distribution of Ab levels. White pie, Ab− (< 6.25 AU/mL); grey pie, Ab+ (6.25-20 AU/mL); dark grey pie, Ab++ (20-200 AU/mL); black pie, Ab+++ (> 200 AU/mL) in serum samples with sufficient ASE activity (> 100 U/L), borderline ASE activity (50-100 U/L), and insufficient ASE activity (< 50 U/L) after the administration of native E coli, pegylated E coli, or Erwinia ASE.

Pie charts representing the distribution of Ab levels. White pie, Ab− (< 6.25 AU/mL); grey pie, Ab+ (6.25-20 AU/mL); dark grey pie, Ab++ (20-200 AU/mL); black pie, Ab+++ (> 200 AU/mL) in serum samples with sufficient ASE activity (> 100 U/L), borderline ASE activity (50-100 U/L), and insufficient ASE activity (< 50 U/L) after the administration of native E coli, pegylated E coli, or Erwinia ASE.

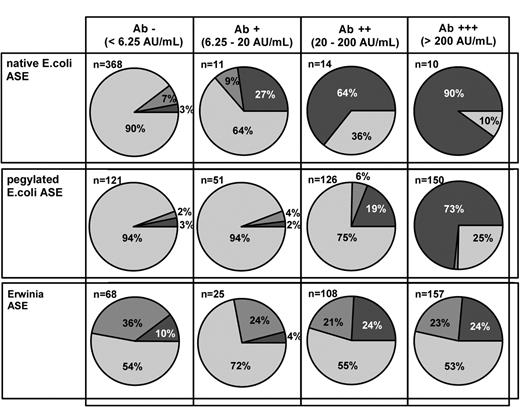

When samples tested Ab negative, the chance of the enzyme activity exceeding 50 U/L or 100 U/L after the administration of pegylated E coli ASE was 96.7% and 94.2%, respectively (= negative predictive value). An intermediately high Ab test result (20-200 AU/mL) was associated with a 6.4-fold increased probability of having an enzyme activity > 50 U/L compared with Ab-negative samples. If the Ab level exceeded 200 AU/mL, the risk of having ASE activity values < 50 U/L was even 73-fold increased (Table 1). Switching to pegylated E coli ASE significantly increased the rate of samples with sufficient and borderline ASE activity in moderately and intermediately Ab-positive serum samples (Ab level 6.25-20 AU/mL: P = .0122; Ab level 20-200 AU/mL: P = .0003) and only failed to increase the rate of samples with sufficient ASE activity in highly positive serum samples (Ab level > 200 AU/mL: P = .2950; Table 2; Figure 3). Because pegylated E coli ASE was applied less frequently for its longer elimination half-life, the level of ASE activity was assessed during a period of 14 days after administration. The rate of Ab-positive/negative samples sorted according to days after administration of pegylated E coli ASE was randomly distributed during this period of time (supplemental Figure 1).

ASE activity distributions (< 50 U/L and > 50 U/L) with different ASE preparations compared against E coli ASE, at different Ab levels. Results were generated applying a generalized linear model that was fitted by generalized estimating equations (GEE)

| ASE . | Ab level* . | OR (activity >50 U/L) . | Confidence limits . | P (χ2) . | Statistically significant difference in therapy? . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASE activity comparison between native and pegylated E coli ASE at different Ab levels | |||||

| Native E coli vs pegylated E coli | Ab− | 1.08 | 0.28-4.25 | .9074 | No, both therapies are comparably effective, native is insignificantly better than pegylated E coli ASE |

| Pegylated E coli vs native E coli | Ab+ | 15.62 | 1.82-134.07 | .0122 | Yes, pegylated is superior to native E coli ASE by OR |

| Pegylated E coli vs native E coli | Ab++ | 8.97 | 2.74-29.34 | .0003 | Yes, pegylated is superior to native E coli ASE by OR |

| Pegylated E coli vs native E coli | Ab+++ | 3.24 | 0.36-29.34 | .295 | No, both therapies are comparably ineffective, pegylated is insignificantly better than native E coli ASE |

| ASE activity comparison between native E coli and Erwinia ASE at different Ab levels | |||||

| Native E coli vs Erwinia | Ab− | 4.02 | 1.37-11.82 | .0114 | Yes, native E coli is superior to Erwinia ASE by OR |

| Erwinia vs native E coli | Ab+ | 5.17 | 0.84-31.78 | .0762 | Borderline yes, Erwinia is superior to native E coli ASE by OR |

| Erwinia vs native E coli | Ab++ | 8.15 | 2.37-28.03 | .0009 | Yes, Erwinia is superior to native E coli ASE by OR |

| Erwinia vs native E coli | Ab+++ | 34.90 | 3.76-323.75 | .0018 | Yes, Erwinia is superior to native E coli ASE by OR |

| ASE activity comparison between pegylated E coli and Erwinia ASE at different Ab levels | |||||

| Pegylated E coli vs Erwinia | Ab− | 3.71 | 0.95-14.49 | .0593 | Borderline yes, pegylated E coli ASE is superior to Erwinia ASE by OR |

| Pegylated E coli vs Erwinia | Ab+ | 3.02 | 0.42-21.87 | .2736 | No, both therapies are comparably effective, pegylated E coli ASE is insignificantly better than Erwinia ASE |

| Pegylated E coli vs Erwinia | Ab++ | 1.10 | 0.54-2.23 | .7884 | No, both therapies are comparably effective, pegylated E coli ASE is insignificantly better than Erwinia ASE |

| Erwinia vs pegylated E coli | Ab+++ | 10.76 | 5.94-19.49 | <.0001 | Yes, Erwinia ASE is superior to pegylated E coli ASE by OR |

| ASE . | Ab level* . | OR (activity >50 U/L) . | Confidence limits . | P (χ2) . | Statistically significant difference in therapy? . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASE activity comparison between native and pegylated E coli ASE at different Ab levels | |||||

| Native E coli vs pegylated E coli | Ab− | 1.08 | 0.28-4.25 | .9074 | No, both therapies are comparably effective, native is insignificantly better than pegylated E coli ASE |

| Pegylated E coli vs native E coli | Ab+ | 15.62 | 1.82-134.07 | .0122 | Yes, pegylated is superior to native E coli ASE by OR |

| Pegylated E coli vs native E coli | Ab++ | 8.97 | 2.74-29.34 | .0003 | Yes, pegylated is superior to native E coli ASE by OR |

| Pegylated E coli vs native E coli | Ab+++ | 3.24 | 0.36-29.34 | .295 | No, both therapies are comparably ineffective, pegylated is insignificantly better than native E coli ASE |

| ASE activity comparison between native E coli and Erwinia ASE at different Ab levels | |||||

| Native E coli vs Erwinia | Ab− | 4.02 | 1.37-11.82 | .0114 | Yes, native E coli is superior to Erwinia ASE by OR |

| Erwinia vs native E coli | Ab+ | 5.17 | 0.84-31.78 | .0762 | Borderline yes, Erwinia is superior to native E coli ASE by OR |

| Erwinia vs native E coli | Ab++ | 8.15 | 2.37-28.03 | .0009 | Yes, Erwinia is superior to native E coli ASE by OR |

| Erwinia vs native E coli | Ab+++ | 34.90 | 3.76-323.75 | .0018 | Yes, Erwinia is superior to native E coli ASE by OR |

| ASE activity comparison between pegylated E coli and Erwinia ASE at different Ab levels | |||||

| Pegylated E coli vs Erwinia | Ab− | 3.71 | 0.95-14.49 | .0593 | Borderline yes, pegylated E coli ASE is superior to Erwinia ASE by OR |

| Pegylated E coli vs Erwinia | Ab+ | 3.02 | 0.42-21.87 | .2736 | No, both therapies are comparably effective, pegylated E coli ASE is insignificantly better than Erwinia ASE |

| Pegylated E coli vs Erwinia | Ab++ | 1.10 | 0.54-2.23 | .7884 | No, both therapies are comparably effective, pegylated E coli ASE is insignificantly better than Erwinia ASE |

| Erwinia vs pegylated E coli | Ab+++ | 10.76 | 5.94-19.49 | <.0001 | Yes, Erwinia ASE is superior to pegylated E coli ASE by OR |

Results were generated applying a generalized linear model that was fitted by generalized estimating equations.

ASE indicates antileukemic enzyme asparaginase; and OR, odds ratio.

Ab−: < 6.25 AU/mL; Ab+: 6.25-20 AU/mL; Ab++: 20-200 AU/mL; Ab+++: > 200 AU/mL.

Pie charts representing the distribution of serum samples with sufficient (> 100 U/L; grey pie), borderline (50-100 U/L; dark grey pie), and insufficient (< 50 /L; black pie) ASE activity in samples with different Ab levels against E coli ASE after the administration of native E coli, pegylated E coli, or Erwinia ASE.

Pie charts representing the distribution of serum samples with sufficient (> 100 U/L; grey pie), borderline (50-100 U/L; dark grey pie), and insufficient (< 50 /L; black pie) ASE activity in samples with different Ab levels against E coli ASE after the administration of native E coli, pegylated E coli, or Erwinia ASE.

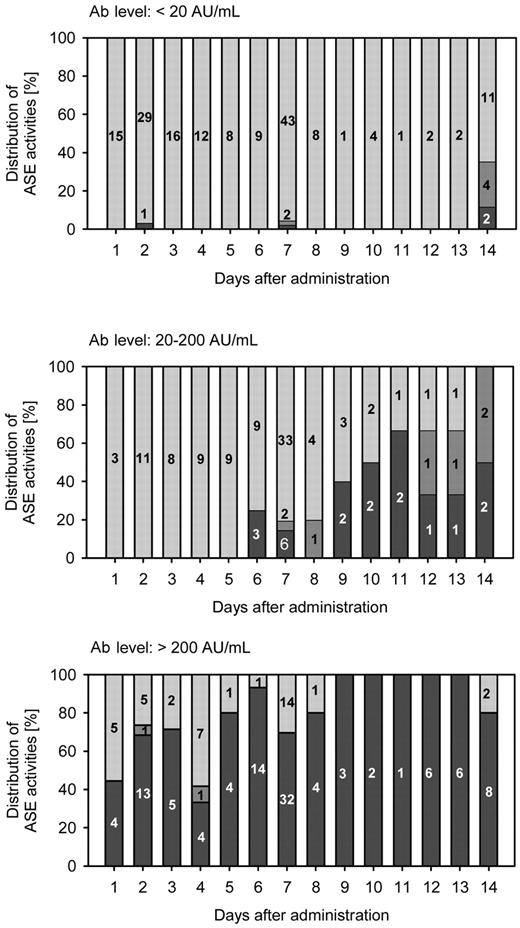

In samples that were negative or only moderately positive for Abs (< 20 AU/mL) the rate of insufficient ASE activity within 14 days after administration was only 2.9%, whereas 19% of intermediately Ab-positive samples (20-200 AU/mL) showed insufficient ASE activity. After the administration of pegylated E coli ASE activity in intermediately Ab-positive samples (20-200 AU/mL) was graded sufficient predominantly during the first week; the rate of samples with sufficient ASE activity decreased rapidly during the second week, indicating a faster clearance of the pegylated enzyme. ASE activity in highly Ab-positive serum samples (> 200 AU/mL) was found to be insufficient during the first and second week after the administration of pegylated E coli ASE (Figure 4).

Distribution of sufficient (> 100 U/L; grey bars), borderline (50-100 U/L; dark grey bars), and insufficient (< 50 U/L; black bars) ASE activity in serum samples with Ab levels < 20 AU/mL, 20-200 AU/mL, and > 200 AU/mL collected during a period of 14 days after the administration of 1000 U/m2 pegylated E coli ASE. The actual numbers of samples are given in the stacked bars.

Distribution of sufficient (> 100 U/L; grey bars), borderline (50-100 U/L; dark grey bars), and insufficient (< 50 U/L; black bars) ASE activity in serum samples with Ab levels < 20 AU/mL, 20-200 AU/mL, and > 200 AU/mL collected during a period of 14 days after the administration of 1000 U/m2 pegylated E coli ASE. The actual numbers of samples are given in the stacked bars.

No significant association between ASE activity and anti–E coli ASE Ab levels was found after the administration of Erwinia ASE (r2 = −0.0637; P = .229; n = 358; Spearman rank order correlation analysis). A switch to Erwinia ASE thus increased the rate of samples with sufficient ASE activity even if the anti–E coli ASE Ab level exceeded 200 AU/mL. In this case, Erwinia ASE was significantly superior to native and even pegylated E coli ASE (Table 2, Figure 5), although a considerable number of samples collected after the administration of Erwinia ASE demonstrated only borderline ASE activity.

Odds of ASE activity > 50 U/L under different ASE preparations (native E coli ASE, black circle; pegylated E coli ASE, grey circle; Erwinia ASE, grey inverted triangle) at different Ab levels against E coli ASE. Results were generated by the application of a generalized linear model that was fitted by generalized estimating equations.

Odds of ASE activity > 50 U/L under different ASE preparations (native E coli ASE, black circle; pegylated E coli ASE, grey circle; Erwinia ASE, grey inverted triangle) at different Ab levels against E coli ASE. Results were generated by the application of a generalized linear model that was fitted by generalized estimating equations.

Discussion

Therapeutic drug monitoring of ASE has been provided within the ALL-BFM trials for more than a decade.8-10,18 Direct monitoring of anti–E coli ASE Abs, to confirm immunologic reactions, has not been performed within the ALL-BFM trials so far. With ASE monitoring provided on an optional basis, the serum samples available for this study originated from a subset of all patients and all ASE administrations in the ALL-BFM 2000 and the ALL-REZ BFM 2002 trials. Because the monitoring of ASE activities allowed the clinician to identify patients with insufficient ASE activity, it was mainly requested to detect silent inactivation of ASE or in case of suspected allergic reactions. The focus in this retrospective analysis of anti–E coli ASE Ab in serum samples monitored for ASE activity is not on rates, incidence and risks of anti–E coli ASE Ab formation during ASE treatment within the ALL-BFM 2000 and ALL-REZ BFM 2002 protocols, but rather on correlating anti– E coli ASE Abs with ASE activity during first-, second-, and third-line ASE treatment in those same protocols. In consequence, the proportion of patients in this retrospective study who received pegylated E coli ASE as a second-line and E Chrysanthemi as a third-line treatment were not supposed to match studies that monitored all the ASE administrations of all patients.10

The detection of Abs against E coli ASE was significantly associated with clinically manifest allergic reactions to E coli ASE, although not all of the patients who demonstrated symptoms of allergic reactions to native E coli ASE tested positive for Abs against E coli ASE. In addition, several samples collected after patients were switched to pegylated E coli ASE, when allergic reactions to front-line native E coli ASE had occurred or were anticipated, were Ab negative. An unnecessary switch of the ASE preparation induced by ambiguous symptoms of allergy might partly explain this finding of Ab-negative samples.19 Moreover, if an allergic reaction to E coli ASE occurred after the last administration of E coli ASE in a treatment course, Ab degradation may have taken place before the subsequent pegylated E coli or Erwinia ASE dose was given. The high rate of anti–E coli ASE Ab-negative samples after the administration of pegylated E coli ASE, but also after Erwinia ASE, in relapsed patients was most likely attributable to the time interval between first-line and relapse treatment.

The association between Ab levels against native E coli ASE and ASE activity was stronger than that observed between anti–E coli Ab levels and clinical symptoms of allergy. However, despite the significant inverse correlation between ASE activity and Ab levels, approximately one-third of samples with insufficient ASE activity after the administration of native E coli ASE tested negative for Ab (Figure 2). This finding indicates that, apart from Abs, other factors, such as insufficient dosing or increased clearance because of degradation by proteases, might also have impacted on treatment efficacy.20 After the administration of pegylated E coli ASE, only 3% of samples with ASE activities < 50 U/L were negative for anti–E coli ASE Abs (Figure 3). In these samples, Abs against polyethylene glycol might have accelerated the clearance of pegylated ASE.21

The benefit of second-line treatment with pegylated E coli ASE after allergic reactions to native E coli ASE is a controversial issue. Less immunogenicity because of shielding of antigenic epitopes by the large covalently bound polyethylene glycol chains was the rationale for the use of pegylated ASE as a second-line treatment after allergic reactions to native E coli ASE. However, Hak et al22 reported that the administration of pegylated E coli ASE, compared with native E coli ASE or Erwinia ASE, after an allergic reaction to native E coli ASE or in case of detectable Abs against the native form did not increase the depletion of asparagine.22

In addition, Asselin et al23 determined an increased clearance of pegylated E coli ASE after allergic reactions to native E coli ASE. However, drug monitoring within the ALL-BFM trials provided evidence of sufficient ASE activity in numerous patients when pegylated E coli ASE was given as a second-line treatment after allergic reactions to E coli ASE. A review of the cases included in the drug monitoring program also revealed, however, a considerable number of patients with insufficient ASE activity who were subsequently switched to third-line treatment with Erwinia ASE.8,10 Also in this retrospective study sufficient ASE activity > 100 U/L was found in approximately 65.9% (295/448) of the samples taken within 14 days after the administration of 1000 U/m2 pegylated E coli ASE (69.0% with ASE activity > 50 U/L [309/448 samples]). By monitoring ASE activity and anti–E coli Ab levels, however, we were for the first time able to relate the efficacy of second-line treatment with pegylated E coli ASE to Ab levels against E coli ASE. Moderately high Ab levels (6.25-20 AU/mL) did not impair the efficacy of pegylated E coli ASE. Almost all patients with moderate or no Ab levels had sufficient ASE activity for 14 days (Figures 3 and 4).

Comparing the different ASE alternatives with native E coli ASE treatment, we found that the probability of ASE activity values > 50 U/L was 15.6-fold increased when switching to pegylated E coli ASE in case of moderately high anti–E coli ASE Ab levels (6.25-20 AU/mL; Table 2). In case of intermediately high Ab levels (20-200 AU/mL) insufficient activity was especially apparent during the second week after the administration of pegylated E coli ASE (Figure 4). This might explain the greater complete remission rates obtained with weekly, compared with biweekly, administration of pegylated E coli ASE observed in relapsed patients.24 The probability of ASE activity values > 50 U/L after 10 000 U/m2Erwinia ASE or 1000 U/m2 pegylated E coli ASE was comparable with Ab levels against native E coli ASE of 20-200 AU/mL (Table 2; Figure 5). On the condition that an ASE activity of > 50 U/L was the desired level to be achieved by the dosing regimens for Erwinia and pegylated ASE applied, the administration of both drugs was feasible in this study (Table 2). When aiming at ASE activities > 100 U/L, however, because of the high number of samples with borderline ASE activity after Erwinia ASE, pegylated E coli ASE was significantly better than Erwinia ASE at Ab levels between 20 and 200 AU/mL (Figure 3; P < .05).

At high Ab levels against E coli ASE (> 200 AU/mL), pegylated E coli ASE failed to produce sufficient ASE activity in the majority of patients, and Erwinia ASE was the superior drug (Figures 3 and 5, Table 2). The missing correlation between anti–E coli ASE Abs and Erwinia ASE activity was consistent with the already reported low cross-reactivity between E coli– and Erwinia-derived ASE.11 When regarding the fact that anti–E coli ASE Ab levels decrease during treatment with Erwinia ASE, one might envisage the use of Erwinia ASE as a second-line, followed by pegylated E coli ASE as a third-line treatment.

Vrooman et al25 reported sufficient ASE activity in 89% of patients who received 25 000 U/m2Erwinia ASE intramuscularly twice weekly after allergic reactions against native E coli ASE. In our study, only 55% of samples reached the target ASE activity of > 100 U/L whereas 80% of samples had ASE activity values > 50 U/L within 2 days after administering 10 000 U/m2Erwinia ASE intravenously. The analysis of samples in this study did not include anti–Erwinia ASE Abs, which might have affected the Erwinia ASE activity values. Albertsen et al26,27 reported the formation of Abs against Erwinia ASE in 8% of patients when Erwinia ASE was used as a front-line treatment and associated Abs against Erwinia ASE with low ASE activity in serum. This finding of a low rate of Ab formation against Erwinia ASE and our finding of approximately 80% of samples with an ASE activity > 50 U/L indicate that inappropriate dosing schedules were most likely responsible for the low activity values observed for Erwinia ASE in our studies.

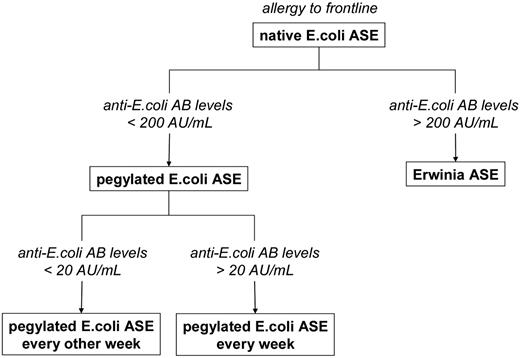

This retrospective analysis clearly related the ASE activity values under second-line treatment with pegylated E coli ASE after an allergic reaction to native E coli ASE to the level of anti–E coli ASE Ab. By monitoring Abs against E coli ASE we were able to identify patients with anti–E coli Ab levels > 200 AU/mL who were likely to have benefitted from an early switch to Erwinia ASE. In addition, one might, for further prospective trials, envisage the weekly use of pegylated E coli ASE in patients with anti–E coli Ab levels between 20 and 200 AU/mL, whereas patients with anti–E coli Ab counts between 6.25 and 20 AU/mL after an allergic reaction to front-line native E coli might continue ASE treatment with pegylated E coli ASE every 2 weeks (Figure 6). Moreover, when the symptoms of allergy are ambiguous, an unnecessary change of the ASE preparation might be avoided by taking Ab levels into account. Finally, because low ASE activity after the administration of native or pegylated E coli ASE was not necessarily associated with anti–E coli ASE Abs, continued monitoring of ASE activity is still required for documentation of sufficient treatment efficacy as well as improvement of dosing regimens.

Proposed treatment algorithm after allergic reactions to front-line native E coli ASE on the basis of antibody levels against E coli ASE.

Proposed treatment algorithm after allergic reactions to front-line native E coli ASE on the basis of antibody levels against E coli ASE.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The development and validation of the ELISA as well as the anti–E coli ASE Ab measurements were performed by medac GmbH. The authors thank G. Braun-Munzinger for editing the manuscript. Chemicals and CAS Registry numbers: asparaginase, 9015-68-3.

Authorship

Contribution: A.W. and C.L.-K. designed the research, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper; J.G. performed the statistical analysis; T.K., D.F., and H.-J.K. performed the measurement of antibodies against E coli ASE; G.H. and A.v.S. coordinated the ALL-REZ BFM 2002 study and recruited patients; A.M. and M.S coordinated the ALL-BFM 2000 study and recruited patients; J.B. initiated the ASE drug monitoring and designed and supervised the research; and all authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: J.B. was paid for contributions of scientific advice and regulatory consulting by medac GmbH, gave invited talks for medac and European Erwinase Providers (EUSAPharm), and provided scientific cooperation on an institutional level for both. M.S. and C.L.-K. gave invited talks for medac GmbH. H.-J.K., D.F., and T.K. are employees of medac GmbH. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Prof Dr Joachim Boos, Department of Pediatric Hematology and Oncology, University Children's Hospital of Muenster, Albert-Schweitzer-Campus 1, A1, 48149 Muenster, Germany; e-mail: boosj@uni-muenster.de.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal