Abstract

Because information on management and outcome of AML relapse after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) with reduced intensity conditioning (RIC) is scarce, a retrospective registry study was performed by the Acute Leukemia Working Party of EBMT. Among 2815 RIC transplants performed for AML in complete remission (CR) between 1999 and 2008, cumulative incidence of relapse was 32% ± 1%. Relapsed patients (263) were included into a detailed analysis of risk factors for overall survival (OS) and building of a prognostic score. CR was reinduced in 32%; remission duration after transplantation was the only prognostic factor for response (P = .003). Estimated 2-year OS from relapse was 14%, thereby resembling results of AML relapse after standard conditioning. Among variables available at the time of relapse, remission after HSCT > 5 months (hazard ratio [HR] = 0.50, 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.37-0.67, P < .001), bone marrow blasts less than 27% (HR = 0.53, 95% CI, 0.40-0.72, P < .001), and absence of acute GVHD after HSCT (HR = 0.67, 95% CI, 0.49-0.93, P = .017) were associated with better OS. Based on these factors, 3 prognostic groups could be discriminated, showing OS of 32% ± 7%, 19% ± 4%, and 4% ± 2% at 2 years (P < .0001). Long-term survival was achieved almost exclusively after successful induction of CR by cytoreductive therapy, followed either by donor lymphocyte infusion or second HSCT for consolidation.

Introduction

The introduction of reduced intensity conditioning (RIC) has opened a new era of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) because of a markedly reduced toxicity.1 Consequently, sibling and unrelated RIC HSCT was studied in patients of older age or with significant comorbidity.2-11 Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is among the most frequent indications for RIC HSCT. According to the latest survey by the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT), 1151 patients, representing 39% of all patients undergoing allogeneic HSCT for de novo AML in 2009, received an RIC.12 However, as in other highly proliferative diseases, results of RIC for AML are generally hampered by an increased risk of relapse. After RIC HSCT in complete remission (CR), relapse rates between 20% and 55% have been reported, being significantly higher than those observed after myeloablative conditioning (MAC).13-16 Consequently, relapse is regarded as the leading cause of treatment failure after RIC HSCT for AML.13,17-19 Once relapse has occurred, patients and physicians face the problem of making a choice between treatment options that range from palliation only to intensive, potentially curative treatments with a high risk of complications. However, information on the management and outcome of AML relapse after RIC HSCT is scarce, and available data are limited to small series.20,21 Studies describing the results to be expected after different therapies and identifying patients who may benefit from treatment are warranted. With this objective, the Acute Leukemia Working Party of EBMT performed a retrospective, registry-based analysis on adults with hematologic relapse after RIC HSCT for AML in CR.

Methods

Inclusion criteria and data collection

Patients with de novo AML were selected from the EBMT registry according to the following criteria: (1) age ≥ 18 years, (2) first allogeneic HSCT between 1999 and 2008, (3) CR at time of transplantation, and (4) RIC. Among these, patients who had experienced hematologic relapse ≥ day 30 after HSCT were included in the analysis. Demographic data, details on transplantation, and annual updates were extracted from the database. Further, transplant centers received a specifically designed questionnaire, asking for details on characteristics and management of relapse. Collected data included age, sex, relationship, and HLA compatibility between patients and donors, cytogenetics, conditioning regimen, reason for RIC, stem cell source, GVHD prophylaxis, response of leukemia and incidence of GVHD after transplantation, duration of posttransplantation remission, leukemia burden at relapse, details of treatment of relapse (chemotherapy, donor lymphocyte infusion [DLI], and second HSCT), and outcome variables as response, overall survival (OS), and cause of death. Physician review of submitted data and personal contact to centers ensured the data quality.

Definitions

According to the EBMT criteria,22 RIC was defined by (1) oral busulfan < 8 mg/kg or intravenous busulfan < 6.4 mg/kg with or without total body irradiation (TBI) ≤ 6 Gy (fractionated) with or without purine analog with or without anti–thymocyte globulin (ATG); (2) cyclophosphamide 60 mg/kg with or without TBI ≤ 6 Gy (fractionated) with or without purine analog with or without ATG; (3) melphalan 140 mg/m2 plus fludarabine with or without ATG; and (4) TBI ≤ 6 Gy (fractionated) with or without purine analog with or without ATG. Hematologic relapse was defined by recurrence of blasts in the peripheral blood (PB) or infiltration of the bone marrow (BM) by > 5% blasts. Patients showing decreasing donor chimerism or cytogenetic/molecular relapse only were excluded. Treatment regimen given for control of the leukemia after relapse were classified as “intensive” if either a standard induction or salvage protocol for AML, containing combinations of AraC plus an anthracycline with or without other drugs, high-dose AraC (≥ 1 g/m2 per day; HIDAC) alone, or a conventional dose anthracycline with or without other drugs were used. In contrast, therapy was considered as “mild” if intermediate or low-dose AraC, low-dose methotrexate, combination of fludarabine and another drug (except HIDAC and anthracyclines), a single cytotoxic drug (except HIDAC or an anthracycline), or targeted drugs, such as histone deacetylase inhibitors, tyrosine kinase inhibitors, arsenic trioxide (ATO), or hypomethylating agents (without addition of intensive chemotherapy as defined earlier in this paragraph) were used. DLI was defined as transfusion of unstimulated lymphocytes, collected from the original donor as buffy coat preparations. Further, as proposed by others, the transfusion of mobilized peripheral blood stem cell (PBSC) concentrates was defined as DLI if no prophylactic immunosuppression was given.23 In contrast, second HSCT was defined as infusion of donor PBSCs or BM, after MAC or RIC, with immunosuppression for GVHD prevention. DLI and second HSCT were summarized as donor cell-based interventions, as suggested.24,25 For disease status before HSCT, CR was defined as described.26 In contrast, for evaluation after relapse, complete hematologic reconstitution was not required for the diagnosis of CR because factors other than leukemia and radio-chemotherapy might contribute to cytopenia (eg, GVHD, or viral infection). Cytogenetic subgroups27 and GVHD28 were classified as described.

Statistical analysis

Cumulative incidence curves were used to estimate relapse incidence, considering death without relapse or progression as competing events. The Gray test was used for comparison.29 Variables considered for their potential prognostic value on outcome were: recipient age, cytogenetics, donor characteristics (type, age, sex, HLA compatibility), transplantation characteristics (year of transplantation, disease stage at transplantation [CR1 vs CR2/CR3], conditioning, stem cell source, use of ATG, aGVHD and/or chronic GVHD [cGVHD] before relapse), and relapse characteristics (interval from transplantation to relapse, percentage of blasts in BM or PB at relapse). Logistic regression was used to identify risk factors for response to treatment. Probabilities of OS from relapse were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier estimate.30 The log-rank test was used for univariate comparisons for all variables considered. Interventions for the treatment of relapse were studied as time-dependent variables. All factors found to influence outcomes in univariate analysis with a P value < .10 were included into a Cox proportional hazard model using time-dependent variables.31 Then, a stepwise backward procedure was used with a cut-off significance level of .05 for deleting factors in the final model. All tests were 2-sided. Finally, patients were classified into prognostic groups on the basis of a score derived from the proportional hazard model, after introduction of significant interactions between all remaining prognostic factors by the likelihood ratio test. SPSS Version 18.0 software and R package 2.7.1 were used.

Results

Patient characteristics and overall outcome

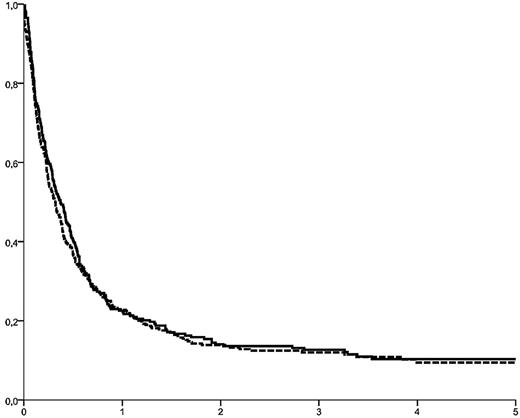

Between 1999 and 2008, 2815 adults had received an allogeneic HSCT after an RIC regimen for AML in CR. Among them, 776 were reported to have relapsed beyond day 30 after HSCT (Table 1). They had been transplanted in first (n = 568; 73%), second (n = 193, 25%), or third (n = 15, 2%) CR. Median age was 55.7 years (range, 18-76 years); the median interval from transplantation to relapse was 5.54 months (range, 1-83 months). The cumulative incidence of relapse after RIC HSCT in CR was 32% ± 1%, 34% ± 1%, and 38% ± 1% after 2, 3, and 5 years, respectively. Patients transplanted in CR2/CR3 showed a trend toward a higher relapse rate (35% ± 2% vs 32% ± 1% at 2 years, P = .08). OS from relapse was 13.9% ± 1%, 12.2% ± 1%, and 9.8% ± 1% at 2, 3, and 5 years (Figure 1).

Basic characteristic of 776 patients with relapsed AML after RIC HSCT in CR

| . | Total n = 776 . | Patients with basic data n = 513 . | Patients with detailed report n = 263 . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient sex, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 422 (54) | 291 (57) | 131 (50) | .07 |

| Female | 354 (46) | 222 (43) | 132 (50) | |

| Median age, y (range) | 55.7 (18-76) | 55.7 (18-76) | 55.7 (18-71) | .83 |

| Cytogenetics according to SWOG criteria26 , n (%) | ||||

| Good | 22 (3) | 9 (4) | 13 (6) | .07 |

| Intermediate | 326 (42) | 173 (77) | 153 (67) | |

| Poor | 103 (17) | 42 (19) | 61 (27) | |

| Missing | 325 | 289 | 36 | |

| Median date of transplantation | September 2005 | November 2005 | March 2005 | < .0001 |

| Stage at transplant, n (%) | ||||

| CR1 | 568 (73) | 370 (72) | 198 (75) | .6 |

| CR2 | 193 (25) | 132 (26) | 61 (23) | |

| CR3 | 15 (2) | 11 (2) | 4 (2) | |

| Donor relation, n (%) | ||||

| HLA ID | 476 (61) | 304 (59) | 172 (65) | .10 |

| Other | 300 (39) | 209 (41) | 913 (5) | |

| Sources of stem cells, n (%) | ||||

| BM | 89 (11) | 66 (13) | 23 (9) | .02 |

| PB | 665 (86) | 428 (83) | 237 (90) | |

| CB | 22 (3) | 19 (4) | 3 (1) | |

| ATG as part of GVHD prevention, n (%) | ||||

| No | 412 | 260 (70) | 152 (58) | .002 |

| Yes | 224 | 113 (30) | 111 (42) | |

| TBI as part of the conditioning, n (%) | ||||

| No | 541 | 363 (71) | 178 (68) | .3 |

| Yes | 232 | 147 (29) | 85 (32) | |

| Acute GVHD after first HSCT, n (%) | ||||

| Grade 0/I | 621 | 399 | 222 (85) | .62 |

| ≥ grade II | 115 | 78 (16) | 39 (15) | |

| Chronic GVHD after first HSCT, n (%) | ||||

| No | 429 (55) | 257 (50) | 172 (65) | .82 |

| Limited | 118 (15) | 68 (13) | 50 (19) | |

| Extensive | 97 (13) | 60 (12) | 37 (14) | |

| Missing | 132 (17) | 128 (25) | 4 (2) | |

| Median interval from first HSCT to relapse (mo, range) | 5.54 (1-83) | 5.7 (1-83) | 5.02 (1-60) | .42 |

| . | Total n = 776 . | Patients with basic data n = 513 . | Patients with detailed report n = 263 . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient sex, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 422 (54) | 291 (57) | 131 (50) | .07 |

| Female | 354 (46) | 222 (43) | 132 (50) | |

| Median age, y (range) | 55.7 (18-76) | 55.7 (18-76) | 55.7 (18-71) | .83 |

| Cytogenetics according to SWOG criteria26 , n (%) | ||||

| Good | 22 (3) | 9 (4) | 13 (6) | .07 |

| Intermediate | 326 (42) | 173 (77) | 153 (67) | |

| Poor | 103 (17) | 42 (19) | 61 (27) | |

| Missing | 325 | 289 | 36 | |

| Median date of transplantation | September 2005 | November 2005 | March 2005 | < .0001 |

| Stage at transplant, n (%) | ||||

| CR1 | 568 (73) | 370 (72) | 198 (75) | .6 |

| CR2 | 193 (25) | 132 (26) | 61 (23) | |

| CR3 | 15 (2) | 11 (2) | 4 (2) | |

| Donor relation, n (%) | ||||

| HLA ID | 476 (61) | 304 (59) | 172 (65) | .10 |

| Other | 300 (39) | 209 (41) | 913 (5) | |

| Sources of stem cells, n (%) | ||||

| BM | 89 (11) | 66 (13) | 23 (9) | .02 |

| PB | 665 (86) | 428 (83) | 237 (90) | |

| CB | 22 (3) | 19 (4) | 3 (1) | |

| ATG as part of GVHD prevention, n (%) | ||||

| No | 412 | 260 (70) | 152 (58) | .002 |

| Yes | 224 | 113 (30) | 111 (42) | |

| TBI as part of the conditioning, n (%) | ||||

| No | 541 | 363 (71) | 178 (68) | .3 |

| Yes | 232 | 147 (29) | 85 (32) | |

| Acute GVHD after first HSCT, n (%) | ||||

| Grade 0/I | 621 | 399 | 222 (85) | .62 |

| ≥ grade II | 115 | 78 (16) | 39 (15) | |

| Chronic GVHD after first HSCT, n (%) | ||||

| No | 429 (55) | 257 (50) | 172 (65) | .82 |

| Limited | 118 (15) | 68 (13) | 50 (19) | |

| Extensive | 97 (13) | 60 (12) | 37 (14) | |

| Missing | 132 (17) | 128 (25) | 4 (2) | |

| Median interval from first HSCT to relapse (mo, range) | 5.54 (1-83) | 5.7 (1-83) | 5.02 (1-60) | .42 |

RIC indicates reduced intensity conditioning; BM, bone marrow; PB, peripheral blood; CB, cord blood; HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; CR, complete remission; ATG, anti thymocyte globulin; TBI, total body irradiation; and GVHD, graft-versus-host disease.

OS from relapse in 776 patients (solid curve) with recurrent AML after RIC HSCT in CR. OS was 13.9% ± 2%, 12.2% ± 1%, and 9.8% ± 1% at 2, 3, and 5 years, respectively. Identical outcome was observed for the cohort of 263 patients with complete data available (dotted curve; P = .43).

OS from relapse in 776 patients (solid curve) with recurrent AML after RIC HSCT in CR. OS was 13.9% ± 2%, 12.2% ± 1%, and 9.8% ± 1% at 2, 3, and 5 years, respectively. Identical outcome was observed for the cohort of 263 patients with complete data available (dotted curve; P = .43).

In 263 patients (34% of the entire cohort), detailed information on the characteristics and management of relapse was provided by the respective transplant centers, allowing for an analysis of risk factors for OS from relapse, and for outcome of the different treatment strategies. Among other criteria, this group was well matched to the entire cohort of 776 relapsed patients with respect to cytogenetic subgroups, sex and age of patients and donors, type of donor (identical sibling vs unrelated donor), stage at transplantation (CR1 vs CR2/CR3), duration of remission after transplantation, and history of GVHD after HSCT. In contrast, the patients reported more in detail had been transplanted somewhat earlier (median, March 2005 vs November 2005, P < .0001), had received more PBSCs instead of BM (P = .02), and had been given more ATG for GVHD prophylaxis (P = .002, Table 1). Age had been the reason for choosing an RIC regimen in 49%. Other reasons included participation in an RIC protocol/study and comorbidities. Fludarabine/busulfan was the most frequently used conditioning regimen (43%); 32% of patients had received low-dose TBI. Details on RIC transplantation and relapse in these 263 patients are provided in Table 2.

Reduced intensity conditioning and post transplant relapse in 263 patients with detailed report

| . | n . | % . |

|---|---|---|

| Reason for reduced intensity conditioning | ||

| Age of the recipient | 128 | 49.4 |

| Protocol driven | 77 | 29.7 |

| Comorbidity | 46 | 17.5 |

| Intensive pretreatment | 4 | 1.5 |

| Physician decision | 1 | 0.4 |

| Missing | 7 | 2.3 |

| Conditioning regimen | ||

| TBI ± chemotherapy* | 85 | 32.3 |

| Fludarabin + busulfan | 114 | 43.3 |

| Fludarabin + melphalan | 41 | 15.6 |

| Cyclophosphamide + fludarabin ± other chemo | 21 | 8.0 |

| Fludarabin + AraC | 2 | 0.8 |

| Acute GVHD after transplantation | ||

| No | 191 | 72.6 |

| Grade I | 31 | 11.8 |

| ≥ grade II | 39 | 14.8 |

| Missing | 2 | 0.8 |

| Chronic GVHD after transplantation | ||

| No | 172 | 65 |

| Limited | 50 | 19 |

| Extensive | 37 | 14 |

| Missing | 4 | 2 |

| Interval from RIC HSCT to relapse, median (range) | 5.02 (1-60) | |

| % blast in BM at relapse, median, (range; n = 208) | 27 (0-100) | |

| % blast in PB at relapse, median (range; n = 221) | 5 (0-100) | |

| Extramedullary relapse | ||

| Yes | 34 | 12.9 |

| No | 224 | 85.2 |

| Missing | 5 | 1.9 |

| . | n . | % . |

|---|---|---|

| Reason for reduced intensity conditioning | ||

| Age of the recipient | 128 | 49.4 |

| Protocol driven | 77 | 29.7 |

| Comorbidity | 46 | 17.5 |

| Intensive pretreatment | 4 | 1.5 |

| Physician decision | 1 | 0.4 |

| Missing | 7 | 2.3 |

| Conditioning regimen | ||

| TBI ± chemotherapy* | 85 | 32.3 |

| Fludarabin + busulfan | 114 | 43.3 |

| Fludarabin + melphalan | 41 | 15.6 |

| Cyclophosphamide + fludarabin ± other chemo | 21 | 8.0 |

| Fludarabin + AraC | 2 | 0.8 |

| Acute GVHD after transplantation | ||

| No | 191 | 72.6 |

| Grade I | 31 | 11.8 |

| ≥ grade II | 39 | 14.8 |

| Missing | 2 | 0.8 |

| Chronic GVHD after transplantation | ||

| No | 172 | 65 |

| Limited | 50 | 19 |

| Extensive | 37 | 14 |

| Missing | 4 | 2 |

| Interval from RIC HSCT to relapse, median (range) | 5.02 (1-60) | |

| % blast in BM at relapse, median, (range; n = 208) | 27 (0-100) | |

| % blast in PB at relapse, median (range; n = 221) | 5 (0-100) | |

| Extramedullary relapse | ||

| Yes | 34 | 12.9 |

| No | 224 | 85.2 |

| Missing | 5 | 1.9 |

BM indicates bone marrow; TBI, total body irradiation; GVHD, graft-versus-host disease; PB, peripheral blood; Gy, gray; RIC, reduced intensity conditioning; HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; and GVHD, graft-versus-host disease.

A total of 2 Gy, n = 79; and 4 Gy, n = 6.

Initial management of relapse

Beyond supportive care and discontinuation of immunosuppression, some sort of anti–leukemic therapy was given to all 263 patients, either with palliative or curative intention. The choice of initial treatment was up to the treating physicians' and the patients' discretion. Treatment was composed of chemotherapy alone (mild, 33.5%, intensive, 17.9%), chemotherapy followed by DLI (18.3%) or second HSCT (7.6%), DLI alone (with or without chemotherapy and second HSCT on progression, 15.2%), and second transplantation alone (7.6%). The various treatment groups differed significantly with respect to year of transplantation (P = .002), duration of posttransplantation remission (P = .05), leukemia burden at relapse (P = .002), and donor type (P = .02). Therefore, a direct comparison of treatments could not be performed. Overall, 32% of patients achieved CR after their primary intervention. The only factor predicting for response was a longer interval between HSCT and relapse (P = .003, HR = 4.86, 95% CI, 1.70-13.90). Among patients receiving mild therapy as primary intervention (followed or not by DLI or a second transplantation), low-dose AraC with or without another mild drug, such as hydroxyurea or fludarabine, was the most frequently reported regimen and led to disease control in 7 of 16 informative patients. 5-Azacytidine alone was effective in 2 of 10 informative patients; other approaches were used in few patients without relevant effect. However, interpretation of these data are difficult because type of chemotherapy and response were not systematically evaluated in patients who received mild chemotherapy alone for palliation. In contrast, reliable information on the efficacy of intensive chemotherapy given for initial control of leukemic proliferation was available. Best results were achieved by combinations containing high- or intermediate-dose AraC plus an anthracycline with or without a third drug, such as fludarabine or etoposide, inducing CR in 32 of 71 evaluable patients (45%). The addition of gemtuzumab ozogamicin (Mylotarg) to chemotherapy was effective in 2 of 14 patients only. Other approaches, including the addition of new drugs (5-azacytidine, valproic acid, ATO), were used in individual patients but could not be evaluated systematically because of limited numbers. CR rates and OS obtained by the different treatments, as well as details on DLI and second SCT are provided in Table 3.

Initial management and outcome of different strategies for treatment of AML relapse after RIC HSCT in 263 patients

| . | n . | % . | Median interval from relapse to start of treatment, d (range) . | CR rate, % . | OS at 2 years from relapse, % . | Cause of death . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild chemotherapy alone | 24/88* | 33.5 | 12 (1-46) | 17 | 6.8 ± 3 | n = 82 (78 leukemia/4 NRM) |

| Intensive chemotherapy alone | 47 | 17.9 | 10 (1-97) | 27 | 4.4 ± 3 | n = 46 (42 leukemia/4 NRM) |

| Chemotherapy followed by DLI†‡ | 48 | 18.3 | 13 (2-109) | 30 | 12.6 ± 5 | n = 39 (33 leukemia/6 NRM) |

| Chemotherapy followed by 2nd HSCT§ | 20 | 7.6 | 13 (1-69) | 56 | 42.4 ± 11 | n = 13 (8 leukemia/5 NRM) |

| DLI without prior chemotherapy (with or without 2nd HSCT)‡§‖ | 40 | 15.2 | 16.5 (1-81) | 36 | 25 ± 7 | n = 32 (27 leukemia/5 NRM) |

| 2nd HSCT without prior chemotherapy§¶ | 20 | 7.6 | 16.5 (1-99) | 41 | 15 ± 8 | n = 19 (11 leukemia/8 NRM) |

| . | n . | % . | Median interval from relapse to start of treatment, d (range) . | CR rate, % . | OS at 2 years from relapse, % . | Cause of death . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild chemotherapy alone | 24/88* | 33.5 | 12 (1-46) | 17 | 6.8 ± 3 | n = 82 (78 leukemia/4 NRM) |

| Intensive chemotherapy alone | 47 | 17.9 | 10 (1-97) | 27 | 4.4 ± 3 | n = 46 (42 leukemia/4 NRM) |

| Chemotherapy followed by DLI†‡ | 48 | 18.3 | 13 (2-109) | 30 | 12.6 ± 5 | n = 39 (33 leukemia/6 NRM) |

| Chemotherapy followed by 2nd HSCT§ | 20 | 7.6 | 13 (1-69) | 56 | 42.4 ± 11 | n = 13 (8 leukemia/5 NRM) |

| DLI without prior chemotherapy (with or without 2nd HSCT)‡§‖ | 40 | 15.2 | 16.5 (1-81) | 36 | 25 ± 7 | n = 32 (27 leukemia/5 NRM) |

| 2nd HSCT without prior chemotherapy§¶ | 20 | 7.6 | 16.5 (1-99) | 41 | 15 ± 8 | n = 19 (11 leukemia/8 NRM) |

Results cannot be compared among the treatment groups due to significant imbalances with respect to important patient characteristics.

OS indicates overall survival; DLI, donor lymphocyte infusion; PBSC, peripheral blood stem cells, NRM, non-relapse mortality; and HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

Because of the palliative intention of the treatment in many cases, data on the interval from relapse to treatment as well as on response were not systematically collected in patients treated with mild chemotherapy alone; hence, the data presented here are based on 24 patients only of 88 who had received mild chemotherapy alone.

DLI consisted of lymphocytes alone in 26 and lymphocytes plus PBSCs in 20 patients; cell type was missing in 2 patients. Stage at DLI was active disease (n = 26), aplasia (n = 3), CR with minimal residual disease (n = 1), CR (n = 10), and unknown (n = 8). A total of 44% received 1, 31% received between 2 and 6, and 25% received an unknown number of infusions.

Among the 88 patients receiving DLI with or without prior chemotherapy, the median number of CD3+ cells transfused were 1 × 107/kg. In patients receiving additional PBSCs, the median number of CD34+ cells was 2.48 × 106/kg.

Among the 42 patients receiving a second HSCT with or without prior chemotherapy or DLI, the same donor as for first HSCT was used in 31, whereas in 11 patients, another donor was chosen. A total of 29 patients had an HLA ID sibling, 1 had a mismatched relative, and 12 had an unrelated donor. The conditioning was myeloablative and reduced in 21 patients each. All but 1 patient received PBSCs. The small numbers did not allow for a detailed analysis of risk factors after HSCT2 or an estimate of the role of a new donor.

DLI consisted of lymphocytes alone in 28 and lymphocytes plus PBSC in 5 patients; cell type was missing in 7 patients. At the time of DLI, median percentage of blasts was 0 (range, 0-85) in PB, and 14 (range, 1-60) in BM. A total of 35% received 1, 35% received > 1, and 30% received an unknown number of infusions. An escalating dose regimen was used in 1 of 3 of patients.

At start of conditioning, median percentage of blasts was 0 (range, 0-84) in PB and 30 (range 0-90) in BM.

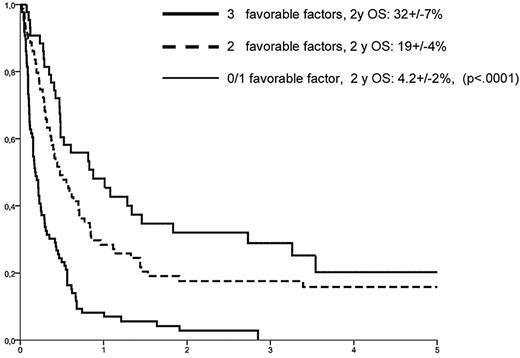

Outcome and risk factors for survival

Among the 263 patients with completed datasets, 32 were alive at last follow-up, 231 had died from leukemia (n = 199), treatment-related (n = 29), or other causes (n = 3). With a median follow-up of 41 months (range, 3.5-114 months), 2-year OS from relapse was 14.1% ± 2%, equalizing the outcome of the entire cohort of 776 relapsed patients (P = .43, Figure 1). A risk factor analysis for OS was based on variables available at the time of relapse (Table 4). In a multivariate model, an interval between HSCT and relapse more than 5 months (HR = 0.50, 95% CI, 0.37-0.67, P < .001), a BM infiltration at relapse below the median of 27% blasts (HR = 0.53, 95% CI, 0.40-0.72, P < .001), and absence of aGVHD after HSCT (HR = 0.67, 95% CI, 0.49-0.93, P = .017) were associated with longer OS. In contrast, age, donor type (HLA-id family vs other), stage at HSCT (CR1 vs CR2+), cytogenetic subgroups, year of transplantation, type of RIC, stem cell source, and use of ATG did not show a significant influence in the multivariate model. Because of a close correlation with remission duration, absence of cGVHD after HSCT was not significant in the multivariate model either. Based on the 3 predictive variables, a score could be developed, allowing for a prognostic estimate of outcome at time of relapse. Accordingly, patients with 0 or 1, 2, and 3 favorable factors had a 2-year OS probability of 4.2% ± 2%, 19% ± 4%, and 32% ± 7%, respectively (P < .0001, Figure 2).

Risk factor analysis for outcome in 263 patients

| Variable . | OS at 2 years from relapse (%) . | P . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate . | Multivariate . | ||

| Interval from first transplant to relapse | |||

| < 5 mo (median) | 7.5 ± 2 | < .0001 | < .001 |

| > 5 mo | 20.6 ± 4 | ||

| Stage at first transplant | |||

| CR1 | 15.7 ± 3 | .46 | ND |

| CR2/3 | 9.4 ± 4 | ||

| Donor type (1st transplant) | |||

| HlA identical sibling | 17.9 ± 3 | .006 | NS |

| other | 6.9 ± 3 | ||

| Year of transplant | |||

| Y ≤ 2005 | 19 ± 3 | .01 | NS |

| Y > 2005 | 4.2 ± 2 | ||

| Age > 56 y (median) | |||

| ≤ 56 y | 17 ± 3 | .18 | ND |

| > 56 y | 11.3 ± 3 | ||

| Cytogenetic subgroups27 | |||

| Good | 19 ± 11 | .71 | ND |

| Intermediate | 12 ± 3 | ||

| Poor | 14 ± 5 | ||

| Missing | 22 ± 7 | ||

| ATG for GvHD prophylaxis | |||

| No | 12 ± 3 | 0.19 | ND |

| Yes | 18 ± 4 | ||

| TBI for conditioning | |||

| No | 18 ± 3 | 0.16 | ND |

| Yes | 6 ± 3 | ||

| Blast in BM at relapse | |||

| < 27 (median) | 22.1 ± 4 | < .0001 | < .001 |

| > 27 | 7 ± 2 | ||

| Acute GVHD after RIC HSCT | |||

| No | 15.6 ± 3 | .02 | .017 |

| Yes | 10.3 ± 4 | ||

| Chronic GVHD after RIC HSCT | |||

| No | 10.9 ± 2 | .01 | NS |

| Yes | 25.3 ± 6 | ||

| Variable . | OS at 2 years from relapse (%) . | P . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate . | Multivariate . | ||

| Interval from first transplant to relapse | |||

| < 5 mo (median) | 7.5 ± 2 | < .0001 | < .001 |

| > 5 mo | 20.6 ± 4 | ||

| Stage at first transplant | |||

| CR1 | 15.7 ± 3 | .46 | ND |

| CR2/3 | 9.4 ± 4 | ||

| Donor type (1st transplant) | |||

| HlA identical sibling | 17.9 ± 3 | .006 | NS |

| other | 6.9 ± 3 | ||

| Year of transplant | |||

| Y ≤ 2005 | 19 ± 3 | .01 | NS |

| Y > 2005 | 4.2 ± 2 | ||

| Age > 56 y (median) | |||

| ≤ 56 y | 17 ± 3 | .18 | ND |

| > 56 y | 11.3 ± 3 | ||

| Cytogenetic subgroups27 | |||

| Good | 19 ± 11 | .71 | ND |

| Intermediate | 12 ± 3 | ||

| Poor | 14 ± 5 | ||

| Missing | 22 ± 7 | ||

| ATG for GvHD prophylaxis | |||

| No | 12 ± 3 | 0.19 | ND |

| Yes | 18 ± 4 | ||

| TBI for conditioning | |||

| No | 18 ± 3 | 0.16 | ND |

| Yes | 6 ± 3 | ||

| Blast in BM at relapse | |||

| < 27 (median) | 22.1 ± 4 | < .0001 | < .001 |

| > 27 | 7 ± 2 | ||

| Acute GVHD after RIC HSCT | |||

| No | 15.6 ± 3 | .02 | .017 |

| Yes | 10.3 ± 4 | ||

| Chronic GVHD after RIC HSCT | |||

| No | 10.9 ± 2 | .01 | NS |

| Yes | 25.3 ± 6 | ||

ND indicates not done; and NS, not significant.

Prognostic groups as defined by risk factors available at time of relapse. Longer interval between HSCT and relapse, a lower BM infiltration by leukemic blasts, and having no history of aGVHD after HSCT were associated with superior outcome.

Prognostic groups as defined by risk factors available at time of relapse. Longer interval between HSCT and relapse, a lower BM infiltration by leukemic blasts, and having no history of aGVHD after HSCT were associated with superior outcome.

The role of remission induction and GVL effects for outcome

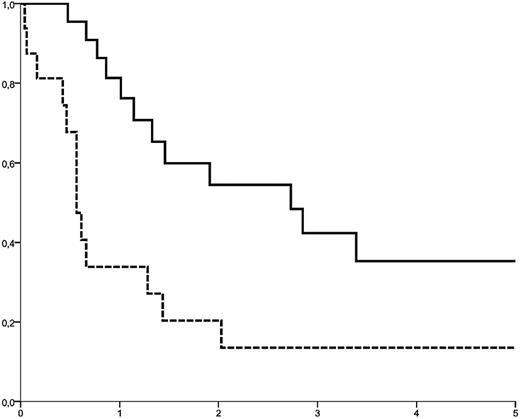

The importance of response to initial chemotherapy and the role of a donor cell-based intervention (DLI or second HSCT) were studied in 127 patients who had received cytoreductive therapy as first treatment for relapse and for whom information on response to the primary treatment was available (Table 5). Regardless of the intensity of cytoreduction, the induction of CR was strongly associated with survival (2-year OS from relapse: 40.7% ± 8% vs 4.4% ± 2% in patients not achieving CR, P < .0001). However, among patients achieving CR (n = 38), outcome was highly dependent on the use of donor cells for consolidation: 2-year OS was 55% ± 11% in patients who received either DLI (n = 12) or a second HSCT (n = 10), whereas, despite initial response to chemotherapy, only 20% plus or minus 10% were alive at 2 years without a further donor cell-based treatment (Figure 3). After failure of initial chemotherapy (n = 89), donor cell-based interventions were of limited value. CR was achieved by DLI in 4 of 26 patients, and by a second HSCT in 6 of 8 patients, but 2-year OS was only 6.3% ± 4% among patients who received donor cells without prior induction of CR. In particular, DLI was not able to prolong survival when given with active disease.

The role of remission induction and donor cells for outcome

| Response to initial chemotherapy (no. of patients) . | Secondary intervention . | Median OS after relapse, mo (95% CI) . | OS at 2 y after relapse, mo (SD) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| no CR (n = 89) | No donor cell no infusion, n = 53 | 2.6 (1.3-3.9) | 3.8 (± 3) |

| DLI, n = 28 (25 with active disease and 3 in aplasia) | 5.1 (3.5-6.64) | 3.8 (± 3) | |

| Second HSCT, n = 8 (all in refractory relapse) | 8.2 (6.7-9.5) | 18.8 (± 16) | |

| Any donor cell based therapy (DLI or second HSCT), n = 36 | 6.4 (4.5-8.3) | 6.3 (± 4) | |

| CR (n = 38) | No donor cell no infusion, n = 16 | 6.8 (5.1-8.4) | 20 (± 10) |

| DLI, n = 12 (1 with active disease; 1 MRD; 10 in CR) | 22.9 (0-49) | 50 (± 17) | |

| Second HSCT, n = 10 (9 in CR2; 1 in CR3) | 33 (4.5-61) | 60 (± 16) | |

| Any donor cell based therapy (DLI or second HSCT), n = 22 | 32.7 (11.8-53.5) | 55 (± 11) |

| Response to initial chemotherapy (no. of patients) . | Secondary intervention . | Median OS after relapse, mo (95% CI) . | OS at 2 y after relapse, mo (SD) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| no CR (n = 89) | No donor cell no infusion, n = 53 | 2.6 (1.3-3.9) | 3.8 (± 3) |

| DLI, n = 28 (25 with active disease and 3 in aplasia) | 5.1 (3.5-6.64) | 3.8 (± 3) | |

| Second HSCT, n = 8 (all in refractory relapse) | 8.2 (6.7-9.5) | 18.8 (± 16) | |

| Any donor cell based therapy (DLI or second HSCT), n = 36 | 6.4 (4.5-8.3) | 6.3 (± 4) | |

| CR (n = 38) | No donor cell no infusion, n = 16 | 6.8 (5.1-8.4) | 20 (± 10) |

| DLI, n = 12 (1 with active disease; 1 MRD; 10 in CR) | 22.9 (0-49) | 50 (± 17) | |

| Second HSCT, n = 10 (9 in CR2; 1 in CR3) | 33 (4.5-61) | 60 (± 16) | |

| Any donor cell based therapy (DLI or second HSCT), n = 22 | 32.7 (11.8-53.5) | 55 (± 11) |

SD indicates standard deviation.

Different outcome among patients achieving CR by cytoreductive treatment. Upper curve: Patients receiving a donor cell-based intervention (DLI or second transplant). Lower curve (dotted): Patients without a cellular therapy given for consolidation (P = .038, DLI and second HSCT were considered as time-dependent variables).

Different outcome among patients achieving CR by cytoreductive treatment. Upper curve: Patients receiving a donor cell-based intervention (DLI or second transplant). Lower curve (dotted): Patients without a cellular therapy given for consolidation (P = .038, DLI and second HSCT were considered as time-dependent variables).

Discussion

This study aimed to provide data on a large group of patients relapsing after RIC HSCT for AML and to identify patients who may or may not benefit from the currently used interventions. Analysis of relapse incidence after HSCT and OS from relapse was based on the registry data of 776 patients. The 2-year CI of relapse after RIC HSCT for AML in CR was 32%; later relapses were rare events. For a detailed analysis of risk factors, we focused on a subset of 263 patients, on whom additional information had been provided by the respective transplant centers, using a specific questionnaire. This subgroup was well matched with the entire cohort with respect to the majority of characteristics, showed nearly identical survival, and was therefore regarded as representative, although an unrecognized bias could not be completely excluded. Based on risk factors available at time of relapse, a scoring system allowed for an estimate of an individual patient's prognosis. Whereas 2-year OS from relapse was only 14%, a subset of patients with a longer remission, a lower tumor burden at relapse, and without previous aGVHD had a significantly better outcome. Induction of CR by cytoreductive therapy, followed by a donor cell-based consolidation (DLI or second transplant) was the strategy with the highest chance for long-term survival.

Strict inclusion criteria and an extensive survey among centers, including repeated questionnaires and personal contacts, were used to provide data on the largest cohort studied so far in the setting of AML relapse after RIC HSCT and ensure a high data quality. Nevertheless, the nature of a retrospective, registry-based analysis implicates several limitations. First, we were not able to determine the effect of discontinuation of immunosuppressive medication. This is a drawback, although withdrawal of immunosuppression is thought to be unlikely to result in clinical benefit in hematologic relapse.32 Second, the different strategies used for initial management and subsequent treatment of posttransplantation relapse could not be formally compared because the reason for the choice of treatment in a given patient could not be worked out retrospectively and because the characteristics of the cohorts receiving the various initial treatments differed significantly. Hence, our study does not allow to precisely define the optimal therapy neither with respect to the choice of drugs and the intensity of the regimen used for initial cytoreduction nor with respect to the choice between DLI and second HSCT. For initial disease control, classic chemotherapy regimen based on AraC and an anthracycline seemed to be the most effective approach, leading to freedom of blasts in 45% of patients. Among mild regimens, low-dose AraC was the most frequently used regimen, showing a limited efficacy on disease control. Concerning the efficacy of modern drugs, definitive conclusions were hampered by the limited numbers and the diversity of applied treatments, although results in informative patients were moderate at best. Despite these limitations, the provided data from each treatment group might give a reasonable idea of the results to be expected after using one of the described approaches.

Using a multivariate model, a scoring system for the estimate of an individual patient's prognosis at time of relapse was established. Whereas the better outcome of patients without aGVHD after transplantation remains to be fully explained, the 2 most important risk factors (ie, remission duration after HSCT and leukemia burden at relapse) both reflect the unfavorable influence of a highly proliferative disease, a finding that has also been described by earlier studies on AML relapse after HSCT.23,33,34 Therefore, and because better evidence from prospective studies might not be available within the near future, our data may help clinicians identify those patients who have a chance for long-term remission. This could influence the choice and intensity of treatment and might be of particular relevance in the elderly and less fit population usually considered for RIC HSCT. Obviously, despite the large number of patients included in this analysis, a prospective validation of our data is mandatory.

Patients relapsing after RIC differ from those who relapse after an MAC with respect to age and comorbidities and have been exposed to lower doses of (radio-) chemotherapy. It has therefore been hypothesized by several groups that characteristics, management, and outcome of relapse after an RIC should differ from that of relapse after MAC HSCT.35,36 This is not supported by our analysis because the observed results were similar to what had been reported after relapse from MAC transplantation, both with respect to response to initial treatment and to OS from relapse.34,37-39

The importance of remission induction by primary cytoreduction and the role for a donor cell-based strategy as part of the management of relapse were studied among those patients who had received cytoreductive therapy as a first step of their treatment (Table 5). Accordingly, OS after failure of initial chemotherapy was extremely poor. Few remissions could be achieved in these patients by DLI or second HSCT, but long-term survival was limited to a small minority, after second transplantation. This finding is in line with data from another report on relapse after RIC.21 In that study, not even one patient achieved disease control with second- or third-line therapy, indicating an important role of remission induction for the outcome posttransplantation relapse. However, in our analysis, induction of CR alone was not sufficient for long-term survival, as patients in CR after initial treatment showed a clear difference with respect to OS, depending on whether or not DLI or a second transplantation were given for consolidation. In patients without a donor cell infusion, median OS was 6.8 months only, despite response to the initial chemotherapy. In contrast, long-term survival was observed after DLI or a second HSCT given for consolidation (Figure 3). Because of the retrospective nature of the study, it cannot be excluded that patients who remained in remission long enough to get a donor cell-based consolidation might represent a selected group. Nevertheless, the strategy to give DLI and/or a second HSCT after successful induction of remission by other means seemed to be the only way to achieve durable disease control. Similar observations have also been reported after relapse from both standard HSCT24 and RIC.21 However, whereas in the study from Houston,21 long-term OS was limited to recipients of a second HSCT, a 2-year OS of 50% could also be achieved after DLI in our cohort, when given as consolidation for chemotherapy-induced CR. Hence, relapse after RIC HSCT does not necessarily indicate complete failure of the GVL effect in these patients, provided that the rapid proliferation of AML can be controlled before donor cell transfusion.

For the future, given the unsatisfying overall results after treatment for recurrent AML both after RIC and MAC HSCT, prevention of posttransplantation relapse will be an important step toward improving the results.40 This might include the use of standard or intermediate intensity conditioning regimen41 instead of RIC in those patients who can tolerate it, and supports the inclusion of innovative compounds into preparation protocols. Further approaches, both after RIC and MAC HSCT, include maintenance treatment using prophylactic DLI42 or novel drugs,43,44 or early intervention based on the detection of minimal residual disease.45,46 Besides, there is an urgent need for strategies to augment the anti–leukemic efficacy of donor cells, as summarized recently.17,32 Inclusion of relapsed patients in carefully designed prospective multicenter trials is mandatory for a long-term improvement.

Presented in part at the EBMT Annual Congress, Paris, France, April 4, 2011, and the Austrotransplant Meeting, Villach, Austria, October 28, 2010.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

Following EBMT publication rules, co-authorship was offered to centers contributing the highest number of patients. Nevertheless, the authors highly appreciate the contribution by many physicians and data managers throughout the EBMT, who made this analysis possible. A list of contributing centers is provided in the supplemental Appendix (available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

Authorship

Contribution: C.S., V.R., and M.M. designed the study, analyzed and interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript; M.L. designed the study, managed, analyzed, and interpreted data, and gave final approval of the manuscript; A.N. designed the study, analyzed and interpreted data, provided clinical data, and wrote the manuscript; D.N., L.C., R.T., M.S., J.K., J.C., J.V., G.S., M.F., L.V., P.L., G.J., and N.K. provided clinical data and critically reviewed and gave final approval of the manuscript; A.R. wrote the manuscript; and E.P. managed and analyzed data and gave final approval of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Christoph Schmid, Department of Hematology and Oncology, Klinikum Augsburg, Ludwig-Maximilians Universität München, Stenglinstr 2, D-86156 Augsburg, Germany; e-mail: christoph.schmid@klinikum-augsburg.de.

References

Author notes

V.R. and M.M. contributed equally to this study.