Abstract

Even though hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) dysfunction is presumed in myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), the exact nature of quantitative and qualitative alterations is unknown. We conducted a study of phenotypic and molecular alterations in highly fractionated stem and progenitor populations in a variety of MDS subtypes. We observed an expansion of the phenotypically primitive long-term HSCs (lineage−/CD34+/CD38−/CD90+) in MDS, which was most pronounced in higher-risk cases. These MDS HSCs demonstrated dysplastic clonogenic activity. Examination of progenitors revealed that lower-risk MDS is characterized by expansion of phenotypic common myeloid progenitors, whereas higher-risk cases revealed expansion of granulocyte-monocyte progenitors. Genome-wide analysis of sorted MDS HSCs revealed widespread methylomic and transcriptomic alterations. STAT3 was an aberrantly hypomethylated and overexpressed target that was validated in an independent cohort and found to be functionally relevant in MDS HSCs. FISH analysis demonstrated that a very high percentage of MDS HSC (92% ± 4%) carry cytogenetic abnormalities. Longitudinal analysis in a patient treated with 5-azacytidine revealed that karyotypically abnormal HSCs persist even during complete morphologic remission and that expansion of clonotypic HSCs precedes clinical relapse. This study demonstrates that stem and progenitor cells in MDS are characterized by stage-specific expansions and contain epigenetic and genetic alterations.

Introduction

Recent experimental evidence shows that cancer stem cells can exist as pools of relatively quiescent cells that do not respond well to common cell-toxic agents and thereby contribute to treatment failure.1 Myeloid malignancies can also arise from a small population of quiescent cancer-initiating cells that are not eliminated by conventional cytotoxic therapies.2 An improved understanding of the molecular pathways that regulate these disease-initiating stem cells is required for the development of future targeted therapies. Even though there is increasing evidence for the existence of leukemia-initiating stem cells from various murine models, there is less known about stem cell alterations in myelodysplastic syndromes (MDSs), particularly in humans. Although it is assumed that MDS is a “stem cell disease,” hard evidence for this claim is still lacking, and stem and progenitor alterations in MDS patients have not yet been defined.

Furthermore, even though chromosomal abnormalities, mutations, and epigenetic changes are seen in MDS progenitors, the earliest cellular stages at which pathogenic events occur have not been determined. Some studies in MDS have focused on the subset of patients with chromosomal 5q deletion (5q−) and have shown that stem cells in MDS harbor the deletion.3-5 A recent study also showed that these cells persist in the bone marrow (BM) of patients with 5q− during lenalidomide treatment and can be predictive of relapses.3 The 5q subset only involves 5%-10% of MDS cases, and an analysis of stem and progenitor populations is warranted in other subtypes of the disease.

In an attempt to answer these questions, we conducted a study of stem and progenitor populations in a variety of MDS subtypes. Our results reveal that primitive stem cell compartments (phenotypic long-term hematopoietic stem cells [LT-HSCs] and short-term hematopoietic stem cells [ST-HSCs]) have striking alterations in DNA methylation and harbor karyotypic abnormalities that persist even in the presence of a morphologic and cytogenetic remission. Furthermore, we observe an expansion of common myeloid progenitor (CMP) or granulocyte monocyte progenitor (GMP) populations that correlate with low- and high-risk subtypes of MDS, respectively, and illustrate the cellular level of the differentiation arrest seen in MDS. These findings demonstrate the existence of a pool of genetically and epigenetically abnormal stem cells in MDS that may lead to the development of multilineage cytopenias, which are the hallmark of this disease.

Methods

Patient samples

Specimens were obtained from 17 patients diagnosed with MDS and controls after signed informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approval by the Albert Einstein College of Medicine and Moffitt Cancer Center Institutional Review Boards. MDS subtypes included refractory cytopenias with multilineage dysplasia, refractory anemia, refractory anemia with excess blasts, and chronic myelomonocytic leukemia.6 Genomic DNA was extracted by a standard phenol-chloroform protocol followed by an ethanol precipitation and resuspension in 10mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0. Total RNA was extracted using an RNeasyMicro kit from QIAGEN and subjected to amplification using the MessageAmp II aRNAkit from Ambion.

Reagents

Signal transducer and activator of transcription (Stat)3 inhibitors, STAT3 inhibitor V (Stattic) and STAT3 inhibitor VI S3I-201, were purchased from Calbiochem (EMD Chemicals). Inhibitors were dissolved in DMSO at 40mM (inhibitor V) and 5mM (inhibitor VI) stored light-protected at 4°C (inhibitor V) and −20°C (inhibitor VI).

Cell culture

Primary human hematopoietic cells were cultured at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 24 to 48 hours in serum-free stem cell culture media (Cellgenix) supplemented with 50 ng/mL recombinant human stem cell factor, 5 ng/mL recombinant human IL-3, and 5 ng/mL recombinant human IL-6 (all cytokines were purchased from PeproTech).

High-speed multiparameter FACS

Mononuclear cells were isolated from BM aspirates by density gradient centrifugation and then subjected to immunomagnetic enrichment of CD34+ cells (Miltenyi Biotec). CD34+ cells were stained with PE-Cy5 (Tricolor)-conjugated monoclonal antibodies against lineage antigens (CD2, CD3, CD4, CD7, CD10, CD11b, CD14, CD15, CD19, CD20, CD56, glycophorin A; all purchased from BD Biosciences) as well as fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies against CD34 (eBioscience), CD38 (eBioscience), CD90 (eBioscience), CD45RA (eBioscience), and CD123 (eBioscience). Cells were analyzed and sorted on a Becton Dickinson FACSAriaII special order system equipped with 4 lasers (407-nm, 488-nm, 561/568-nm, 633/647-nm). Based on established surface marker characterization, we distinguished and sorted LT-HSCs (Lin−, CD34+, CD38−, CD90+), ST-HSCs (Lin−, CD34+, CD38−, CD90−), CMPs (Lin−, CD34+, CD38+, CD123+, CD45RA−), GMPs (Lin−, CD34+, CD38+, CD123+, CD45RA+), and megakaryocyte-erythrocyte progenitors (MEPs: Lin−, CD34+, CD38+, CD123−, CD45RA−).7,8 Relative percentages of LT-HSCs and ST-HSCs were calculated and expressed as ratios of cells in the individual stem cell gates divided by the number of all HSCs (Lin−CD34+CD38−). Relative percentages of CMPs, GMPs, and MEPs were calculated and expressed as ratios of the numbers in the individual progenitor gates divided by the number of all myeloid progenitor subtypes combined. Small aliquots of the cells were sorted into special serum-free stem cell culture media (Cellgenix) containing recombinant cytokines (IL-3, IL-6, stem cell factor, thrombopoietin, Fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 ligand) for subsequent functional confirmation of the sorted cells from healthy controls. A portion of the cells were sorted directly into DNA or RNA extraction buffers to isolate nucleic acids from the different subpopulations. To assess the phosphorylation status of STAT3, we performed flow cytometric phosphoprotein analysis as we have previously described.9 In brief, cells were grown in liquid culture and treated with STAT3 inhibitor V, or STAT3 inhibitor VI for 36 hours at 37°C. Cells were fixed and permeabilized using BD Cytofix Fixation Buffer and BD Phosphoflow Perm Buffer III (BD Biosciences) and then stained with Pacific Blue anti-pStat3 (pY705, BD Biosciences) at a 1:5 dilution. Cells were analyzed with a BD FACSAriaII Special Order system (BD Biosciences). pSTAT3 levels were quantified by calculating fold changes of the median fluorescence intensity of inhibitor-treated cells compared with DMSO-treated cells.

Methylcellulose assays

CMPs, GMPs, and MEPs were tested in methylcellulose assays to confirm their clonogenic potential, as performed before7,8,10,11 (supplemental Figure 2A-B, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). FACS-sorted HSCs (Lin−CD34+CD38−) were plated in a concentration of 5000 cells/mL into semisolid medium (H4434 GF+; StemCell Technologies) and cultured according to the manufacturer's recommendation. After 12 days of culture, formed colonies were scored, and cells were isolated from the plates and cytospun on microscopic slides. Cytospun cells were dried for at least 2 hours at room temperature and stained with DiffQuick solution according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Cell morphology was evaluated using an inverted microscope (Zeiss Axioplan; Zeiss Optics). To assess STAT3 inhibition, sorted Lin−CD34+CD38− HSCs were plated in concentrations ranging from 500-5000 cells/mL into cytokine-containing, semisolid medium (H4434 GF+; StemCell Technologies) supplemented with 40 μg/mL human low-density lipoproteins (Sigma-Aldrich) in technical duplicates. STAT3 inhibitor V and STAT3 inhibitor VI were added to the medium via 100× dilutions. After 12 days of culture in a humidified chamber at 37°C, 5% CO2, colonies were scored using an inverted microscope (Zeiss Axioplan; Zeiss Optics).

DNA methylation analysis by nano-HELP

The nano-HELP assay was carried out as previously published.12 Intact DNA of high molecular weight was corroborated by electrophoresis on 1% agarose gel in all cases. Genomic DNA was digested overnight with either HpaII or MspI (NEB). On the following day, the reactions were extracted once with phenol-chloroform and resuspended in 11 μL of 10mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, and the digested DNA was used to set up an overnight ligation of the HpaII adapter using T4 DNA ligase. The adapter-ligated DNA was used to carry out the PCR amplification of the HpaII and MspI-digested DNA as previously described.13 Both amplified fractions were submitted to Roche-NimbleGen for labeling and hybridization onto a human hg17 custom-designed oligonucleotide array (50-mers) covering 25 626 HpaII amplifiable fragments located at gene promoters. HpaII amplifiable fragments are defined as genomic sequences contained between 2 flanking HpaII sites found within 200-2000 bp from each other. Each fragment on the array is represented by 15 individual probes distributed randomly spatially across the microarray slide. Thus, the microarray covers 50 000 CpGs corresponding to 14 000 gene promoters.

HELP microarray quality control

All microarray hybridizations were subjected to extensive quality control using the following strategies. First, uniformity of hybridization was evaluated using a modified version of a previously published algorithm14 adapted for the NimbleGen platform, and any hybridization with strong regional artifacts was discarded and repeated. Second, normalized signal intensities from each array were compared against a 20% trimmed mean of signal intensities across all arrays in that experiment, and any arrays displaying a significant intensity bias that could not be explained by the biology of the sample were excluded.

HELP data processing and analysis

Signal intensities at each HpaII amplifiable fragment were calculated as a robust (25% trimmed) mean of their component probe-level signal intensities. Any fragments found within the level of background MspI signal intensity, measured as 2.5 mean-absolute-differences above the median of random probe signals, were categorized as “failed.” These “failed” loci therefore represent the population of fragments that did not amplify by PCR, whatever the biologic (eg, genomic deletions and other sequence errors) or experimental cause. On the other hand, “methylated” loci were so designated when the level of HpaII signal intensity was similarly indistinguishable from background. PCR-amplifying fragments (those not flagged as either “methylated” or “failed”) were normalized using an intra-array quantile approach wherein HpaII/MspI ratios are aligned across density-dependent sliding windows of fragment size-sorted data. The log2(HpaII/MspI) was used as a representative for methylation and analyzed as a continuous variable. For most loci, each fragment was categorized as either methylated if the centered log HpaII/MspI ratio was less than zero, or hypomethylated if on the other hand the log ratio was greater than zero.

Unsupervised clustering of HELP data by hierarchical clustering was performed using the statistical software R Version 2.6.2. A 2-sample t test was used for each gene to summarize methylation differences between groups. Genes were ranked on the basis of this test statistic, and a set of top differentially methylated genes with an observed log fold change of > 1 between group means was identified. Genes were further grouped according to the direction of the methylation change (hypomethylated vs hypermethylated in MDS HSCs), and the relative frequencies of these changes were computed among the top candidates to explore global methylation patterns. Functional pathway analysis was performed by Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) tool.

Gene expression profiling

RNA integrity was corroborated with the Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100. RNA (100 ng/μL; 3 μL) was submitted to the Genomics Facility, Albert Einstein College of Medicine for gene expression studies using Human GeneChip ST 1.0 (Affymetrix) arrays. All microarray data are available at the Gene Expression Omnibus database under accession no. GSE38955.

FISH of sorted hematopoietic stem and progenitor populations

Target slides were prepared by directly sorting stem and progenitor populations into a drop of 1× PBS on poly-lysine–coated slides. The cell suspensions on the slides were immediately air-dried; afterward the cells were fixed in Carnoy solution. The following dual-color probes (Abbott Molecular) were used to detect monosomy 7/7q deletions, 5q deletions, and 20q deletions: LSI D7S522 (7q31) SpectrumOrange/CEP7 SpectrumGreen, EGR-1 SpectrumOrange/D5S721/ D5S23 SpectrumGreen, D20S108 SpectrumOrange/TEL20p SpectrumGreen.

FISH has been performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole and examined on a Zeiss Axioplan 2 fluorescence microscope. The frequency of false-positive signal loss for the used FISH probes was established by hybridization to cytospin preparations of normal hematopoietic stem, progenitor populations, and myeloblasts and ranged from 5% to 10%. For the purpose of this study, the cut-off value for true signal loss, corresponding to monosomy 7/7q deletion, was set at > 20%, after scoring 100 nuclei per slide.

Results

MDS bone marrow shows disease stage-dependent expansion of distinct stem and progenitor cell compartments

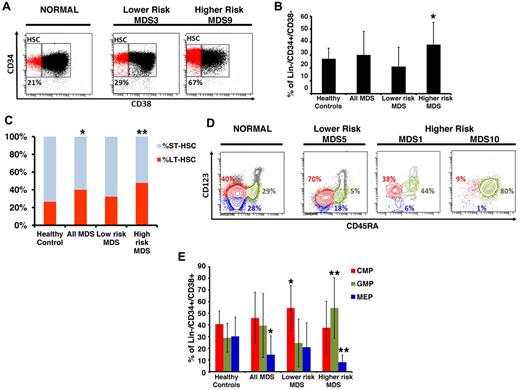

We and others have previously used protocols to isolate phenotypically defined LT-HSCs, ST-HSCs, CMPs, GMPs, and MEPs from primary BM aspirates of patients with myeloid malignancies.2,7,8,15,16 Our flow-based assays include stringent lineage depletion as a strategy to exclude blasts and other more differentiated cell types and has been shown to be successful in identifying cellular and transcriptional aberrations in the most immature stem and progenitor cells in mouse and human leukemias.7,8 Here, we used this sorting strategy in MDS and compared 17 primary BM samples from untreated MDS patients with 16 healthy controls (clinical characteristics in Table 1; see supplemental Figure 1 for sorting/gating strategy). MDS patients were divided into lower-risk (Low/Int-1 International Prognostic Scoring System [IPSS] scores, N = 8) and higher-risk disease (Int-2/High risk based on IPSS scoring, N = 9) based on their risk of leukemic transformation and overall patient survival.17 We observed an expansion of the stem cell compartment (Lin−CD34+CD38−) that was significant in higher-risk subtypes of MDS (Figure 1A-B). This increase was mainly the result of the significant expansion of the phenotypic primitive LT-HSCs (Lin−CD34+CD38−CD90+) in MDS BMs compared with healthy controls (Figure 1C).

Clinical characteristics of MDS patients

| ID . | MDS subtype . | Karyotype . | IPSS . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | RCMD | −7q | Int-1 |

| 2 | RCMD | +8 | Int-1 |

| 3 | RA | −5q | Low |

| 4 | RA | NML | Low |

| 5 | RCMD | −20q | Low |

| 6 | RCMD | NML | Int-1 |

| 7 | RA | NML | Low |

| 8 | CMML | NML | Int-1 |

| 9 | RAEB | −7 | Int-2 |

| 10 | RAEB | Complex | High |

| 11 | RAEB | NML | High |

| 12 | RAEB | Complex | High |

| 13 | RAEB | −7q | Int-2 |

| 14 | RAEB | −13q | High |

| 15 | RAEB | Complex | High |

| 16 | RAEB | NML | Int-2 |

| 17 | RAEB | Complex | High |

| 18 | RAEB | NML | Int-2 |

| ID . | MDS subtype . | Karyotype . | IPSS . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | RCMD | −7q | Int-1 |

| 2 | RCMD | +8 | Int-1 |

| 3 | RA | −5q | Low |

| 4 | RA | NML | Low |

| 5 | RCMD | −20q | Low |

| 6 | RCMD | NML | Int-1 |

| 7 | RA | NML | Low |

| 8 | CMML | NML | Int-1 |

| 9 | RAEB | −7 | Int-2 |

| 10 | RAEB | Complex | High |

| 11 | RAEB | NML | High |

| 12 | RAEB | Complex | High |

| 13 | RAEB | −7q | Int-2 |

| 14 | RAEB | −13q | High |

| 15 | RAEB | Complex | High |

| 16 | RAEB | NML | Int-2 |

| 17 | RAEB | Complex | High |

| 18 | RAEB | NML | Int-2 |

MDS BM shows expanded stem and progenitor populations. (A) Representative samples of lower- and higher-risk MDS and a healthy control. Shown are FACS analyses of anti-CD34/CD38 costainings within CD34-enriched, viable, lineage marker-negative BM mononuclear cells. (B) Quantification of phenotypic HSCs in healthy control patients (N = 16), lower-risk (n = 8), and higher-risk (n = 9) MDS patients showing a significant expansion of the HSC compartment in patients with higher-risk MDS compared with controls (P < .05, t test). (C) Quantification of phenotypic LT-HSCs and ST-HSCs in healthy control patients (N = 16), lower-risk (n = 8), and higher-risk (n = 9) MDS patients. *P < .05 (t test). **P < .005 (t test). (D) Representative samples of 1 lower-risk and 2 higher-risk MDS patients and a healthy control patient. Shown are FACS analyses of CD123 and CD45RA expression on viable, lineage marker-negative CD34+CD38+ BM mononuclear cells defining myeloid populations: red represents CMP; blue, MEP; and green, GMP. (E) Quantification of phenotypic myeloid progenitors in healthy control patients (N = 16), lower-risk (n = 8), and higher-risk (n = 9) MDS patients showing a significant expansion of the CMP compartment in patients with lower-risk MDS, and significant expansion of the GMP compartment, and significant reduction of the MEP compartment in higher-risk MDS. *P < .05 (t test). **P < .005 (t test).

MDS BM shows expanded stem and progenitor populations. (A) Representative samples of lower- and higher-risk MDS and a healthy control. Shown are FACS analyses of anti-CD34/CD38 costainings within CD34-enriched, viable, lineage marker-negative BM mononuclear cells. (B) Quantification of phenotypic HSCs in healthy control patients (N = 16), lower-risk (n = 8), and higher-risk (n = 9) MDS patients showing a significant expansion of the HSC compartment in patients with higher-risk MDS compared with controls (P < .05, t test). (C) Quantification of phenotypic LT-HSCs and ST-HSCs in healthy control patients (N = 16), lower-risk (n = 8), and higher-risk (n = 9) MDS patients. *P < .05 (t test). **P < .005 (t test). (D) Representative samples of 1 lower-risk and 2 higher-risk MDS patients and a healthy control patient. Shown are FACS analyses of CD123 and CD45RA expression on viable, lineage marker-negative CD34+CD38+ BM mononuclear cells defining myeloid populations: red represents CMP; blue, MEP; and green, GMP. (E) Quantification of phenotypic myeloid progenitors in healthy control patients (N = 16), lower-risk (n = 8), and higher-risk (n = 9) MDS patients showing a significant expansion of the CMP compartment in patients with lower-risk MDS, and significant expansion of the GMP compartment, and significant reduction of the MEP compartment in higher-risk MDS. *P < .05 (t test). **P < .005 (t test).

Examination of committed progenitor populations in these patients revealed that lower-risk MDS is characterized by specific expansion of the phenotypic CMP compartment, possibly pointing to a differentiation block at this cellular level (Figure 1D-E). Patients with higher-risk MDS, on the other hand, showed a significant expansion of the GMP compartment and a relative decrease of the MEP compartment (Figure 1D-E). The expansion of phenotypic GMP varied considerably between patients, ranging up to 90% in 2 patients, which is reflective of the heterogeneity of the disease. This skewed expansion of the GMP compartment in MDS samples with higher risk of leukemic transformation is consistent with recent reports that show that acute myeloid leukemia is characterized by an expansion of immature myeloid cells and can originate from GMP-like stem cells.2,18,19

Stem and progenitor compartments in MDS are enriched for cytogenetically and functionally abnormal cells

We next tested the functional ability of MDS HSCs in clonogenic assays. We have previously shown that BM-derived CD34+ MDS cells have reduced clonogenic capacity in vitro,10,11 and we now studied the clonogenic capacity of sorted Lin−CD34+CD38− MDS HSCs. We observed that these highly fractionated MDS HSCs derived from 4 patients with MDS (2 High and 2 Int-2 score by IPSS) have significantly reduced clonogenic potential compared with healthy control HSCs (Figure 2A) and that they give rise to bilobed, Pelger-Heut like myeloid progenitors that mimic the dysplastic cells seen in MDS patients in vivo (Figure 2B-C). Importantly, we found that the majority of the cells forming these dysplastic colonies harbor clonotypic cytogenetic alterations (98% and 88% of the cells in samples from 2 patients with 7q−), demonstrating that they were part of the abnormal clone (Figure 2D-E). This finding shows that the earliest phenotypically definable HSCs in MDS already carry clonotypic aberrations and that, although they can differentiate to a certain extent in vitro, the efficiency is greatly impaired and leads to formation of dysplastic cells.

Cytogenetic alterations are seen in MDS HSCs. (A) Colony formation assay using sorted Lin−CD34+CD38− cells from 4 MDS patients and 2 healthy controls. Data are mean ± SD for colonies arising from BFU-E and CFU-GM per 5000 plated cells. (B-C) Microscopic image of MDS patient-derived, sorted Lin−CD34+CD38− cells grown in the semisolid culture for 12 days. DiffQuick staining of cytospun cells. Scale bar represents 50 μm. (D-E) FISH analysis of day 12 colonies from 2 patients with MDS. (F) Sorted HSCs from 1 patient with MDS showing monosomy of chromosome 7 in the majority of cells and 1 cell (yellow arrow) with both copies of chromosome 7 (red probe for 7q31 and centromeric green probe). (G) Mean percentages and SEM of abnormal karyotypic clones in lower-risk MDS HSC and progenitor compartments. Gray bar represents the results obtained from whole BM from the clinical diagnostic laboratory. *P < .05 (2-tailed t test).

Cytogenetic alterations are seen in MDS HSCs. (A) Colony formation assay using sorted Lin−CD34+CD38− cells from 4 MDS patients and 2 healthy controls. Data are mean ± SD for colonies arising from BFU-E and CFU-GM per 5000 plated cells. (B-C) Microscopic image of MDS patient-derived, sorted Lin−CD34+CD38− cells grown in the semisolid culture for 12 days. DiffQuick staining of cytospun cells. Scale bar represents 50 μm. (D-E) FISH analysis of day 12 colonies from 2 patients with MDS. (F) Sorted HSCs from 1 patient with MDS showing monosomy of chromosome 7 in the majority of cells and 1 cell (yellow arrow) with both copies of chromosome 7 (red probe for 7q31 and centromeric green probe). (G) Mean percentages and SEM of abnormal karyotypic clones in lower-risk MDS HSC and progenitor compartments. Gray bar represents the results obtained from whole BM from the clinical diagnostic laboratory. *P < .05 (2-tailed t test).

To determine whether all stem and progenitor compartments included karyotypically abnormal cells and to quantify the clone size within each compartment compared with unfractionated BM, we performed FISH analysis on sorted cells using probes specific for the unique alterations in these patients. Interestingly, we observed that HSCs in MDS are enriched for abnormal cells (mean percentage of abnormal cells 92% ± 4%; mean ± SEM) and have a significantly higher percentage of clonotypic cells compared with whole BM aspirates, which are commonly used for FISH studies in a clinical setting (Figure 2F-G; Table 2). This enrichment was seen in cases of both higher- and lower-risk MDS (based on IPSS; Table 2), including cases with loss of chromosome 7 (example of MDS HSCs shown in Figure 2F) as well as deletion of the long arm of chromosome 20 (20q−), 2 abnormalities that have not been previously shown to be present and enriched in the earliest stem cells in MDS. Furthermore, FISH analysis showed that, compared with whole BM, chromosomal deletions are significantly enriched in all examined stem and progenitor compartments, including the expanded ones, demonstrating that these populations are part of the MDS clone (Figure 2G).

Cytogenetic alterations in sorted HSCs and whole bone marrow populations

| No. . | MDS IPSS risk group . | Chromosomal abnormality . | Abnormality in HSCs, % . | Abnormality in whole BM, % . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MDS9 | High | −7 | 99 | 48 |

| MDS10 | Int-2 | −7 | 76 | 60 |

| MDS17 | High | −7 | 100 | 70 |

| MDS15 | High | −7q | 100 | 69 |

| MDS3 | Int-1 | −5 | 100 | 80 |

| MDS5 | Low | −20 | 86 | 57 |

| MDS13 | Int-2 | −7q | 81 | 50 |

| No. . | MDS IPSS risk group . | Chromosomal abnormality . | Abnormality in HSCs, % . | Abnormality in whole BM, % . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MDS9 | High | −7 | 99 | 48 |

| MDS10 | Int-2 | −7 | 76 | 60 |

| MDS17 | High | −7 | 100 | 70 |

| MDS15 | High | −7q | 100 | 69 |

| MDS3 | Int-1 | −5 | 100 | 80 |

| MDS5 | Low | −20 | 86 | 57 |

| MDS13 | Int-2 | −7q | 81 | 50 |

Stem cells in MDS are characterized by widespread alterations in DNA cytosine methylation

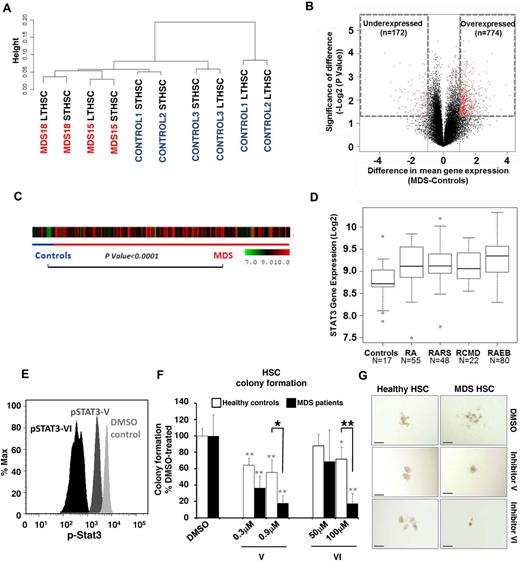

Alterations in DNA cytosine methylation have been shown to exist in CD34+ marrow cells20 as well as in whole marrow aspirates21 of patients with acute myeloid leukemia and MDS, but have not been examined in the earliest phenotypic stem cells. To determine the epigenetic makeup of earliest stem cells in MDS, we devised a modification of the HpaII tiny fragment enrichment by ligation-mediated PCR assay that allows us to conduct genome wide analysis from very limited amounts of cells and DNA (nano-HELP assay).12 The nano-HELP assay was performed on sorted stem cells from 2 MDS patients (higher and lower risk) and compared with the respective stem cell populations of 3 healthy controls. We observed that MDS HSCs clustered separately from healthy control HSCs, revealing striking epigenetic differences between these samples (Figure 3A; supplemental Figure 3). Qualitative analysis revealed both aberrant hypermethylation and hypomethylation in MDS Lin−CD34+CD38− stem cells (Figure 3B). The findings of the HELP assay were validated by MassArray bisulfite analysis of selected loci (supplemental Figure 4). Functional pathways associated with cancer, gene expression, and cell division were affected by aberrant methylation, and many genes not previously implicated in MDS pathobiology were found to be hypermethylated (eg, DLL3, RET, NOTCH4) or hypomethylated (eg, NOTCH1, NANOG, HDAC4) in MDS stem cells (Table 3). These data provide the first evidence of epigenetic alterations in early HSCs in MDS.

Genome-wide DNA methylation analysis of sorted cells reveals widespread changes in MDS HSCs. (A) Hierarchal clustering and heatmap based on methylation profiling reveals differences between MDS HSCs and control HSCs. (B) Volcano plot based on difference of mean methylation and significance of the difference shows both aberrant hypermethylated and hypomethylated loci in MDS HSCs (Lin−CD34+CD38−). Red dots indicate P < .05 and fold change > 1 log2.

Genome-wide DNA methylation analysis of sorted cells reveals widespread changes in MDS HSCs. (A) Hierarchal clustering and heatmap based on methylation profiling reveals differences between MDS HSCs and control HSCs. (B) Volcano plot based on difference of mean methylation and significance of the difference shows both aberrant hypermethylated and hypomethylated loci in MDS HSCs (Lin−CD34+CD38−). Red dots indicate P < .05 and fold change > 1 log2.

Gene pathways aberrantly methylated in MDS HSCs

| . | Biologic functions . | Genes . |

|---|---|---|

| Hypomethylated in MDS HSCs | ||

| 1 | Gene expression, cellular movement, embryonic development | AKT1S1, CDC16, CDC25B, CDK3, CHAF1B, DTX1, EIF4EBP1, ERBB3, FGFR1, FZR1, GALNT14, GATA4, GRLF1, GRWD1, ITM2C, MUC4, MUC5AC, NOTCH1, PARD3, RPS6KA4, TBX5, TFDP1, TFF1, TP53BP2, TRIM24, WDR5 |

| 2 | Carbohydrate metabolism, lipid metabolism, small-molecule biochemistry | AGRN, CAPN5, CASD1, COL6A2, DDX1, ENG, HIP1, HIP1R, LAMA1, LCAT, LIMS1, MAGEA1 (includes EG:4100), MGAT3, MIA, NANOG, NF2, P4HA3, PDLIM2, PXN, RPL22, SGSM3, SH3GLB2, SLC12A6, TGM2, TSPYL2 |

| 3 | Dermatologic diseases and conditions, genetic disorder, skeletal and muscular system Development and function | CSDC2, CTBP1, EDARADD, HDAC4, KCNC1, KHDRBS2, LTB, MAP3K14, MEOX1, MYOG, NLRC4, OTUB2, PGLYRP1, PKP1, SMYD2, SNRPD3, SRL, STAT5A, SYNCRIP, TARDBP, TNFRSF4, TNPO2, WIZ |

| 4 | Cardiovascular system Development and function, embryonic development, organismal development | CBLC, CYP17A1, CYTH2, DRD5, FZD5, GNG3, GPR35, GPR162, GPR179, IL25, LPAR1, LTB4R2, Mapk, MTNR1A, NCKAP1, NRP1, PLXNA1, PTGDR, PTGER3, RNASE2, SLC12A2, SLC18A3, SLC7A1, SLC9A1 |

| 5 | Cellular movement, respiratory disease, hematologic system development and Function | ANGPT2, CXADR, DNAH1, DUSP1, EPPK1, F7, GNAZ, IFITM1, LTA, MAP3K1, MBP, MFGE8, MICAL2, PIGR, PLA2G7, PON2, PRKCH, PTMA, SLC6A4, TACSTD2, TICAM1 |

| Hypermethylated in MDS HSCs | ||

| 1 | Cancer, reproductive system disease, cardiovascular disease | BAT2, CDK16, CITED1, CLASP1, ECEL1, EREG, GANAB, GOT1, GPAA1, KIDINS220, MAN2C1, MAPRE3, MARK4, MCAM, NMB, P4HA2, PFDN6, PHKA2, PIGK, PPAP2B, SIAH2, SPG20, SPRY2, SRD5A2, TP53I11, TRIP10, TUBA1A, TUBA1C, TUBB, TYROBP |

| 2 | Lipid metabolism, small-molecule biochemistry, gastrointestinal disease | B4GALNT1, CHRNE, CILP, CILP2, DLL3, DOK6, EWSR1, GLS, GP1BB, GSPT1, HIVEP1, LAD1, MEOX2, MSX2, MUC1, NDUFB1, NOTCH4, OLFM2, PGLS, PTCD3, RET, SIX3, ST13, STAG2, SYTL1, TNF, ZDHHC3 |

| 3 | Molecular transport, protein trafficking, behavior | ARL4A, CAMK2A, CCDC106, CDKN1B, CRX, DKK1, DLK1, EFEMP1, HOXA7, KAT2A, MBD1, MLL, MYO1C, NELF, NUTF2, PRKD2, PTCD2, RAN, RFC1, RPL12 (includes EG:6136), RPS5, SETDB1, SETMAR, TBL1X, TNPO2, UHRF1, WDR46 |

| 4 | Gene expression, tissue morphology, nervous system development and function | ALDH1B1, APOE, CBR3, CHSY1, FAM129B, FUCA1, GDPD5, GNAI2, HLTF, IGFBP6, LRRC8A, MTMR6, PHOX2A, PPM1B, PRDX1, RDH10, SP1, SP2, STAT6, STOM, UBE2Z, USP3, USP4, USP48, ZCCHC24 |

| 5 | Cell cycle, cellular growth and proliferation, genetic disorder | ADC, ADRM1, CDKN1A, E4F1, EIF6, EIF3J, EIF4B, HIST1H2AE (includes EG:3012), KIF20A, LYN, NMT1, NR2E1 (includes EG:7101), NUDT5, PHC1, PSMA8, PSMB3, PSMB4, PSMC5, SNCAIP, TGFB1I1, TMEM126B, TNNT1, TRIM41, UBE2I |

| . | Biologic functions . | Genes . |

|---|---|---|

| Hypomethylated in MDS HSCs | ||

| 1 | Gene expression, cellular movement, embryonic development | AKT1S1, CDC16, CDC25B, CDK3, CHAF1B, DTX1, EIF4EBP1, ERBB3, FGFR1, FZR1, GALNT14, GATA4, GRLF1, GRWD1, ITM2C, MUC4, MUC5AC, NOTCH1, PARD3, RPS6KA4, TBX5, TFDP1, TFF1, TP53BP2, TRIM24, WDR5 |

| 2 | Carbohydrate metabolism, lipid metabolism, small-molecule biochemistry | AGRN, CAPN5, CASD1, COL6A2, DDX1, ENG, HIP1, HIP1R, LAMA1, LCAT, LIMS1, MAGEA1 (includes EG:4100), MGAT3, MIA, NANOG, NF2, P4HA3, PDLIM2, PXN, RPL22, SGSM3, SH3GLB2, SLC12A6, TGM2, TSPYL2 |

| 3 | Dermatologic diseases and conditions, genetic disorder, skeletal and muscular system Development and function | CSDC2, CTBP1, EDARADD, HDAC4, KCNC1, KHDRBS2, LTB, MAP3K14, MEOX1, MYOG, NLRC4, OTUB2, PGLYRP1, PKP1, SMYD2, SNRPD3, SRL, STAT5A, SYNCRIP, TARDBP, TNFRSF4, TNPO2, WIZ |

| 4 | Cardiovascular system Development and function, embryonic development, organismal development | CBLC, CYP17A1, CYTH2, DRD5, FZD5, GNG3, GPR35, GPR162, GPR179, IL25, LPAR1, LTB4R2, Mapk, MTNR1A, NCKAP1, NRP1, PLXNA1, PTGDR, PTGER3, RNASE2, SLC12A2, SLC18A3, SLC7A1, SLC9A1 |

| 5 | Cellular movement, respiratory disease, hematologic system development and Function | ANGPT2, CXADR, DNAH1, DUSP1, EPPK1, F7, GNAZ, IFITM1, LTA, MAP3K1, MBP, MFGE8, MICAL2, PIGR, PLA2G7, PON2, PRKCH, PTMA, SLC6A4, TACSTD2, TICAM1 |

| Hypermethylated in MDS HSCs | ||

| 1 | Cancer, reproductive system disease, cardiovascular disease | BAT2, CDK16, CITED1, CLASP1, ECEL1, EREG, GANAB, GOT1, GPAA1, KIDINS220, MAN2C1, MAPRE3, MARK4, MCAM, NMB, P4HA2, PFDN6, PHKA2, PIGK, PPAP2B, SIAH2, SPG20, SPRY2, SRD5A2, TP53I11, TRIP10, TUBA1A, TUBA1C, TUBB, TYROBP |

| 2 | Lipid metabolism, small-molecule biochemistry, gastrointestinal disease | B4GALNT1, CHRNE, CILP, CILP2, DLL3, DOK6, EWSR1, GLS, GP1BB, GSPT1, HIVEP1, LAD1, MEOX2, MSX2, MUC1, NDUFB1, NOTCH4, OLFM2, PGLS, PTCD3, RET, SIX3, ST13, STAG2, SYTL1, TNF, ZDHHC3 |

| 3 | Molecular transport, protein trafficking, behavior | ARL4A, CAMK2A, CCDC106, CDKN1B, CRX, DKK1, DLK1, EFEMP1, HOXA7, KAT2A, MBD1, MLL, MYO1C, NELF, NUTF2, PRKD2, PTCD2, RAN, RFC1, RPL12 (includes EG:6136), RPS5, SETDB1, SETMAR, TBL1X, TNPO2, UHRF1, WDR46 |

| 4 | Gene expression, tissue morphology, nervous system development and function | ALDH1B1, APOE, CBR3, CHSY1, FAM129B, FUCA1, GDPD5, GNAI2, HLTF, IGFBP6, LRRC8A, MTMR6, PHOX2A, PPM1B, PRDX1, RDH10, SP1, SP2, STAT6, STOM, UBE2Z, USP3, USP4, USP48, ZCCHC24 |

| 5 | Cell cycle, cellular growth and proliferation, genetic disorder | ADC, ADRM1, CDKN1A, E4F1, EIF6, EIF3J, EIF4B, HIST1H2AE (includes EG:3012), KIF20A, LYN, NMT1, NR2E1 (includes EG:7101), NUDT5, PHC1, PSMA8, PSMB3, PSMB4, PSMC5, SNCAIP, TGFB1I1, TMEM126B, TNNT1, TRIM41, UBE2I |

Expression profiling reveals transcriptional alterations and functionally relevant overexpression of STAT3 in MDS HSCs

We also determined the transcriptional alterations in sorted MDS HSCs from 2 patients and compared them with 3 healthy controls. Gene expression analysis revealed differences between MDS and healthy HSCs using unsupervised clustering analysis. However, the differences were less striking than those in DNA cytosine methylation (Figure 4A-B; supplemental Figure 5). Interestingly, a higher proportion of genes were overexpressed in MDS stem cells, including “cell cycle” and “cancer” as the top 2 affected pathways as identified by Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (Table 4). Even though the MDS samples used for methylome and transcriptome studies were from different patients, we observed that there were 9 genes that were consistently hypomethylated and overexpressed (STAT3, WDR5, OBFC2B, SKA3, HEXA, CIAPIN1, VRK3, CHAF1B, and RANBP1) in MDS HSCs. Because STAT3 was significantly overexpressed and hypomethylated, we examined the expression of STAT3 in CD34+ cells of an independent large cohort of MDS patients (N = 183).22 We observed that STAT3 was significantly overexpressed in MDS CD34+ cells (Figure 4C), and subset analysis revealed that elevation of STAT3 was seen in all subsets of MDS (P < .0001, t test; Figure 4D), demonstrating the validity of our genomic analysis on sorted MDS HSCs. To test whether STAT3 overexpression in MDS HSCs is functionally relevant, we assessed the clonogenic capacity of MDS HSCs upon inhibition of STAT3. We used 2 cell-permeable SH2 domain-targeting STAT3 inhibitors, STAT3 inhibitor V (Stattic) and STAT3 inhibitor VI (S3I-201), which have previously been shown to specifically inhibit cellular STAT3 phosphorylation.23-25 Treatment of primary CD34+ BM-MNCs with these inhibitors resulted in reduced levels of phospho-STAT3 (pSTAT3; Figure 4E). Compared with DMSO-treated cells, pSTAT3 levels were reduced by 2.5-fold (59%) and by 16.4-fold (94%) on treatment with STAT3 inhibitor V and STAT3 inhibitor VI, respectively (Figure 4E). Next, we evaluated the clonogenic capacity of sorted Lin−CD34+CD38− HSCs from the BM of 3 patients with MDS and 2 healthy controls after STAT3 inhibition. Compared with colony formation of DMSO-treated HSCs, treatment with STAT3 inhibitors V or VI led to a dose-dependent reduction of MDS HSC-derived colonies by up to 82% ± 9% (P < .01, t test) for inhibitor V, and 83% ± 13% (P < .01, t test) for inhibitor VI (Figure 4F). Consistent with previous reports,26-28 colony formation of healthy HSCs was moderately inhibited after treatment with STAT inhibitor V (by 45% ± 15%; P < .01, t test) and VI (28% ± 15%; P < .05, t test; Figure 4F). However, MDS patient-derived HSCs were significantly more sensitive to STAT3 inhibition than healthy control HSCs (P < .05 for inhibitor V, and P < .01 for inhibitor VI, t test; Figure 4F). Sensitivity of MDS HSCs to STAT3 inhibition was also reflected by phenotypic changes seen in colony-forming assays (Figure 4G).

Gene expression analysis of sorted cells reveals differences between MDS and control HSCs. (A) Unsupervised hierarchal clustering based on gene expression reveals differences between MDS and control HSCs. (B) Volcano plot comparing the difference of mean expression (x-axis) and significance of the difference (y-axis), showing mainly overexpressed genes in MDS HSCs. Red dots indicate P < .05 and fold change > 1 log2. (C) STAT3 gene expression in 183 samples of MDS CD34+ cells and 17 healthy controls is shown as a heatmap. (D) Expression is higher in MDS compared with controls (t test with Benjamin-Hochberg correction). Boxplots show the expression of STAT3 in various FAB subtypes of MDS (RCMD is a subset of the FAB RA category). (E) Phosphoflow analysis showing a reduction of pSTAT3 in CD34+ BM-derived cells 36 hours after treatment with 0.9μM STAT3 inhibitor V and 100μM STAT3 inhibitor VI. (F) Colony formation of Lin−CD34+CD38− HSCs derived from patients with MDS (solid bars) and healthy controls (open bars) treated with 0.3 or 0.9μM inhibitor V, 50 or 100μM inhibitor VI, or DMSO showing a significant reduction of MDS colonies when treated with either inhibitor. Shown are averages of colony numbers expressed as percentage of DMSO-treated colony formation (NMDS = 3; and NHealthy = 2). Black asterisks represent P values from t tests comparing inhibition of colony formation of MDS with healthy control-derived cells; and gray asterisks, P values from t tests comparing inhibition of colony formation of STAT3 inhibitor-treated versus DMSO-treated cells. *P < .05. **P < .01. (G) Representative pictures of HSC-derived colonies in the presence of STAT3 inhibitor V, VI, or DMSO control. Bars represent 200 μm.

Gene expression analysis of sorted cells reveals differences between MDS and control HSCs. (A) Unsupervised hierarchal clustering based on gene expression reveals differences between MDS and control HSCs. (B) Volcano plot comparing the difference of mean expression (x-axis) and significance of the difference (y-axis), showing mainly overexpressed genes in MDS HSCs. Red dots indicate P < .05 and fold change > 1 log2. (C) STAT3 gene expression in 183 samples of MDS CD34+ cells and 17 healthy controls is shown as a heatmap. (D) Expression is higher in MDS compared with controls (t test with Benjamin-Hochberg correction). Boxplots show the expression of STAT3 in various FAB subtypes of MDS (RCMD is a subset of the FAB RA category). (E) Phosphoflow analysis showing a reduction of pSTAT3 in CD34+ BM-derived cells 36 hours after treatment with 0.9μM STAT3 inhibitor V and 100μM STAT3 inhibitor VI. (F) Colony formation of Lin−CD34+CD38− HSCs derived from patients with MDS (solid bars) and healthy controls (open bars) treated with 0.3 or 0.9μM inhibitor V, 50 or 100μM inhibitor VI, or DMSO showing a significant reduction of MDS colonies when treated with either inhibitor. Shown are averages of colony numbers expressed as percentage of DMSO-treated colony formation (NMDS = 3; and NHealthy = 2). Black asterisks represent P values from t tests comparing inhibition of colony formation of MDS with healthy control-derived cells; and gray asterisks, P values from t tests comparing inhibition of colony formation of STAT3 inhibitor-treated versus DMSO-treated cells. *P < .05. **P < .01. (G) Representative pictures of HSC-derived colonies in the presence of STAT3 inhibitor V, VI, or DMSO control. Bars represent 200 μm.

Gene pathways aberrantly expressed in MDS HSCs

| Category . | P . | Molecules . |

|---|---|---|

| Genes overexpressed in MDS HSCs | ||

| Cell cycle | .0000000 | ARL8A, BUB1, CCNA2, CCNB1, CCNB2, ECT2, HJURP, NCAPD3, NDC80, NEK2, NUSAP1, SGOL1, SKA2, SKA3 |

| Cancer | .0000031 | AHCY, BRAF, BUB1B, CCNA2, CCNB2, CDKN3, DDX39A, DHFR, EBP, GGH, GINS2, GINS3, GMNN, HDAC3, IL8, ILF2, KIAA0101, KPNA2, MAD2L1, MAPK8, MCM10, MCM4, MLF1IP, NEK2, NQO1, NUDT5, ORC1, PCNA, POLE3, PTTG1, RAE1, RPP40, TMEM97, TRAPPC2L, TUBB2C |

| Gastrointestinal disease | .0000031 | AHCY, BRAF, BUB1B, CCNA2, CCNB2, CDKN3, DDX39A, DHFR, EBP, GGH, GINS2, GINS3, GMNN, HDAC3, IL8, ILF2, KIAA0101, KPNA2, MAD2L1, MAPK8, MCM10, MCM4, MLF1IP, NEK2, NQO1, NUDT5, ORC1, PCNA, POLE3, PTTG1, RAE1, RPP40, TMEM97, TRAPPC2L, TUBB2C |

| Genetic disorder | .0000031 | AHCY, BRAF, BUB1B, CCNA2, CCNB2, CDKN3, DDX39A, DHFR, EBP, GGH, GINS2, GINS3, GMNN, HDAC3, IL8, ILF2, KIAA0101, KPNA2, MAD2L1, MAPK8, MCM10, MCM4, MLF1IP, NEK2, NQO1, NUDT5, ORC1, PCNA, POLE3, PTTG1, RAE1, RPP40, TMEM97, TRAPPC2L, TUBB2C |

| DNA replication, recombination, and repair | .0000330 | BUB1, BUB1B, CCNB1, CHEK2, FANCD2, MAD2L1, MCM7, NDC80, ZWILCH |

| Genes underexpressed in MDS HSCs | ||

| Inflammatory response | .000072 | CCL4, HLA-DRB3 (includes others), HLA-DRB4, IGHE, KLRC4-KLRK1 |

| Cell-to-cell signaling and interaction | .000305 | CCL4, IGHE, KLRC4-KLRK1 |

| Cell death | .00032 | CCL4, HLA-DRB4, IGHE |

| Genetic disorder | .000448 | HLA-DRB3 (includes others), HLA-DRB4 |

| Category . | P . | Molecules . |

|---|---|---|

| Genes overexpressed in MDS HSCs | ||

| Cell cycle | .0000000 | ARL8A, BUB1, CCNA2, CCNB1, CCNB2, ECT2, HJURP, NCAPD3, NDC80, NEK2, NUSAP1, SGOL1, SKA2, SKA3 |

| Cancer | .0000031 | AHCY, BRAF, BUB1B, CCNA2, CCNB2, CDKN3, DDX39A, DHFR, EBP, GGH, GINS2, GINS3, GMNN, HDAC3, IL8, ILF2, KIAA0101, KPNA2, MAD2L1, MAPK8, MCM10, MCM4, MLF1IP, NEK2, NQO1, NUDT5, ORC1, PCNA, POLE3, PTTG1, RAE1, RPP40, TMEM97, TRAPPC2L, TUBB2C |

| Gastrointestinal disease | .0000031 | AHCY, BRAF, BUB1B, CCNA2, CCNB2, CDKN3, DDX39A, DHFR, EBP, GGH, GINS2, GINS3, GMNN, HDAC3, IL8, ILF2, KIAA0101, KPNA2, MAD2L1, MAPK8, MCM10, MCM4, MLF1IP, NEK2, NQO1, NUDT5, ORC1, PCNA, POLE3, PTTG1, RAE1, RPP40, TMEM97, TRAPPC2L, TUBB2C |

| Genetic disorder | .0000031 | AHCY, BRAF, BUB1B, CCNA2, CCNB2, CDKN3, DDX39A, DHFR, EBP, GGH, GINS2, GINS3, GMNN, HDAC3, IL8, ILF2, KIAA0101, KPNA2, MAD2L1, MAPK8, MCM10, MCM4, MLF1IP, NEK2, NQO1, NUDT5, ORC1, PCNA, POLE3, PTTG1, RAE1, RPP40, TMEM97, TRAPPC2L, TUBB2C |

| DNA replication, recombination, and repair | .0000330 | BUB1, BUB1B, CCNB1, CHEK2, FANCD2, MAD2L1, MCM7, NDC80, ZWILCH |

| Genes underexpressed in MDS HSCs | ||

| Inflammatory response | .000072 | CCL4, HLA-DRB3 (includes others), HLA-DRB4, IGHE, KLRC4-KLRK1 |

| Cell-to-cell signaling and interaction | .000305 | CCL4, IGHE, KLRC4-KLRK1 |

| Cell death | .00032 | CCL4, HLA-DRB4, IGHE |

| Genetic disorder | .000448 | HLA-DRB3 (includes others), HLA-DRB4 |

Cytogenetically abnormal stem cells persist in azacytidine/ vorinostat treatment responders and can predict relapse

After having found that HSCs in MDS harbor cytogenetic and epigenetic alterations, we decided to examine their clinical significance and assess their dynamics in a patient treated with combination epigenetic therapy (DNMT inhibitor 5-azacytidine and HDAC inhibitor vorinostat) as part of the New York Cancer Consortium 6898 trial.29 The patient had refractory anemia with excess blasts with 10% marrow myeloblasts at diagnosis and had an expanded HSC compartment (60% vs mean of 25% seen in controls, percentages relative to total Lin−CD34+ cells) at baseline. Treatment led to a decrease of blasts and a striking decrease in cells with monosomy 7 as detected by FISH in whole BM cells (Figure 5 bottom panel, blue and green lines). Interestingly, even when the patient was in a morphologic marrow remission and had resolution of anemia, the expanded HSCs (Lin−CD34+CD38−) compartment only moderately declined (from 60% to 49%) and continued to harbor a very high percentage of cells with monosomy 7 (FISH showing 97% cells with −7). Strikingly, morphologic relapse in this patient was preceded by a re-expansion of the HSC compartment (from 49% to 87%) by 2 months (Figure 5 red arrow). These observations parallel the stem cell changes that have been recently observed in 5q− MDS treated with lenalidomide.3 These results show for the first time that DNMT inhibitors and HDAC inhibitors do not lead to eradication of clonally abnormal HSCs in MDS, even upon a very good morphologic remission and hematologic recovery.

Abnormal HSCs persist during remission, and their expansion occurs before clinical relapse. MDS9 patient has refractory anemia with excess blasts and attained remission with 5-azacytidine + vorinostat treatment (black arrows) with improvement of anemia (top blue line). Even when the patient was in remission, the HSC compartment was expanded (red line) and harbored cells with monosomy 7 (49% HSCs; FISH showed 97% of these had monosomy 7). Further expansion of HSCs (red arrow) occurred 2 months before relapse with increasing blasts and progressive anemia.

Abnormal HSCs persist during remission, and their expansion occurs before clinical relapse. MDS9 patient has refractory anemia with excess blasts and attained remission with 5-azacytidine + vorinostat treatment (black arrows) with improvement of anemia (top blue line). Even when the patient was in remission, the HSC compartment was expanded (red line) and harbored cells with monosomy 7 (49% HSCs; FISH showed 97% of these had monosomy 7). Further expansion of HSCs (red arrow) occurred 2 months before relapse with increasing blasts and progressive anemia.

Discussion

MDSs are clonal hematopoietic neoplasms that remain incurable with existing nontransplant therapies. Previous studies have hinted at a pathologic involvement of stem cells in MDS by showing that phenotypic HSCs carry the 5q deletion within this subset of patients.3-5 In the present study, we demonstrate that a high proportion of the phenotypically most immature HSCs harbor karyotypic abnormalities, including MDS patients with both favorable (chromosome 20q) and unfavorable (chromosome 7) deletions.30 Moreover, we demonstrate that these stem cells from patients with MDS are functionally deficient and give rise to dysplastic cells. Interestingly, we found that the relative clone size is greater in immature stem and progenitors compared with total BM. This is consistent with the idea that the clonotypic stem cells only produce limited and dysfunctional progeny in vivo. Furthermore, our observation suggests that detection of cytogenetically aberrant clones by FISH may have a higher sensitivity in sorted stem cells compared with whole BM samples routinely collected in the clinical setting. In addition, we show stage-specific alterations in stem and progenitor cell numbers in MDS. Specifically, we observe an expansion of the LT-HSC and GMP progenitor compartments in patients with higher-risk MDS. The expansion of the GMP compartment is consistent with recent reports that have shown that acute myeloid leukemia is characterized by GMP-like cancer-initiating stem cells.19 Thus, it is conceivable that these changes occur before the onset of frank leukemia and can thus be seen in higher-risk MDS. Furthermore, the demonstration of expansion of progenitors with CMP-like phenotype in lower-risk MDS is the first description of stem and progenitor alterations in lower-risk disease and suggest that this may reflect the level of the differentiation block present in these earlier stages of the disease.

In addition, we show that the clonally abnormal HSCs persist even when the patient is in a complete morphologic remission after epigenetic therapy with 5-azacytidine and vorinostat. Moreover, we show that the HSC compartment expands before an overt relapse. Analysis of the HSC compartment in MDS could therefore potentially be used as a strategy to monitor minimal residual disease and could also be used as a biomarker for the development of (stem cell–) targeted therapeutic approaches. Our observations are in line with a recent study that correlated the persistence of HSCs with the 5q− abnormality with relapse after lenalidomide treatment.3 Our findings represent the first demonstration of this phenomenon in a 5-azacytidine-treated patient. 5-Azacytidine is an effective agent that improves overall survival in MDS patients but is unable to cure these patients and is associated with a high rate of relapse.31 The inability of 5-azacytidine to eliminate clonally abnormal HSCs is a potential reason for relapses.

Lastly, we show that, in addition to karyotypic abnormalities, stem cells in MDS exhibit widespread alterations in DNA methylation and also in gene expression. Previous studies have shown an abundance of hypermethylation in CD34+ selected or whole BM cells in MDS. By optimizing the HELP assay, we were able to work with limited amounts of DNA and show that both aberrant hypomethylation and hypermethylation occur in the earliest phenotypic HSCs in MDS. Our results suggest that specific target genes are genetically and epigenetically deregulated in early stem and progenitor cells in MDS, which may make these cells therapeutically targetable. Recent studies have also revealed that DNA methylation does not correlate perfectly with gene expression and may serve as a potential mechanism for marking differentiation and pluripotency genes and poising them for expression regulation during later stages of hematopoietic differentiation.32-35 Our finding of differentially methylated loci in MDS HSCs reveals that epigenetic dysregulation in MDS can also be seen in the most primitive phenotypic cells. Of note, our data exemplarily demonstrate the functional relevance of increased STAT3 at the stem cell level and provide a list of candidate genes for further functional studies and may be used for the development of stem cell–directed therapies in MDS.

Taken together, our findings reveal widespread cytogenetic, epigenetic, and transcription alterations in MDS HSCs, demonstrate the functional and clinical significance of the aberrant immature cell compartments, and suggest that these abnormal stem and progenitor cells should be a focus of future curative therapeutic approaches in MDS.

There is an Inside Blood commentary on this article in this issue.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Guillermo Simkin and the Einstein Human Stem Cell FACS & Xenotransplantation Facility for expert technical assistance.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01HL082946, A.V.; R00CA131503, U.S.), New York Community Trust, Gabrielle's Angel Foundation (A.V. and U.S.), Hershaft Family Foundation, Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, American Cancer Society, Department of Defense, Partnership for Cures (NYSTEM grants CO24306 and C024350, U.S.), Immunology and Immuno-oncology Training Program (T32 CA009173), American Cancer Society (J. T. Tai. & Company Inc postdoctoral fellowship, B.W.), and Leukemia and Lymphoma Research United Kingdom (J.B. and A.P.). The Einstein Human Stem Cell FACS & Xenotransplantation Facility was supported through NYSTEM (grant NO8G-415/C024172).

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: B.W., L.Z., T.O.V., S.B.-N., C. Schinke, R.T., T.B., S.B., L.B., C.H., and Y.M. performed experiments; Y.Y., J.M.G., and C. Steidl analyzed data; S.P., C.M., A.P., J.B., C.M., L.S., J.M., A.F.L., and B.H.Y. contributed samples and gene expression data; and B.W., U.S., and A.V. designed the research, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Ulrich Steidl, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, 1300 Morris Park Ave, Bronx, NY 10461; e-mail: ulrich.steidl@einstein.yu.edu; and Amit Verma, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, 1300 Morris Park Ave, Bronx, NY 10461; e-mail: amit.verma@einstein.yu.edu.