Key Points

These data establish FcγRIIa as a physiologically important functional conduit for αIIbβ3-mediated outside-in signaling.

Abstract

The integrin family is composed of a series of 24 αβ heterodimer transmembrane adhesion receptors that mediate cell-cell and cell-extracellular matrix interactions. Adaptor molecules bearing immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs (ITAMs) have recently been shown to cooperate with specific integrins to increase the efficiency of transmitting ligand-binding–induced signals into cells. In human platelets, Fc receptor γ-chain IIa (FcγRIIa) has been identified as an ITAM-bearing transmembrane receptor responsible for mediating “outside-in” signaling through αIIbβ3, the major adhesion receptor on the platelet surface. To explore the importance of FcγRIIa in thrombosis and hemostasis, we subjected FcγRIIa-negative and FcγRIIa-positive murine platelets to a number of well-accepted models of platelet function. Compared with their FcγRIIa-negative counterparts, FcγRIIa-positive platelets exhibited increased tyrosine phosphorylation of Syk and phospholipase Cγ2 and increased spreading upon interaction with immobilized fibrinogen, retracted a fibrin clot faster, and showed markedly enhanced thrombus formation when perfused over a collagen-coated flow chamber under conditions of arterial and venous shear. They also displayed increased thrombus formation and fibrin deposition in in vivo models of vascular injury. Taken together, these data establish FcγRIIa as a physiologically important functional conduit for αIIbβ3-mediated outside-in signaling, and suggest that modulating the activity of this novel integrin/ITAM pair might be effective in controlling thrombosis.

Introduction

Among the extracellular cues that cells continuously sample and respond to, adhesion is among the most potent, eliciting a wide range of cell biological processes, including but not limited to changes in cytosolic calcium, protein and lipid phosphorylation, cytoskeletal architecture, gene transcription, and cell migration.1 Members of the integrin family, composed of 24 αβ heterodimer transmembrane receptors,2 are particularly adept at transmitting adhesion-initiated signals into the cell in a process sometimes referred to as outside-in signaling.1 The platelet-specific integrin αIIbβ3 (CD41/CD61, glycoprotein [GP] IIb-IIIa in the platelet literature) is among the best-studied members of the integrin family, and is thought to be particularly responsive to intracellular and extracellular stimuli. Thus, binding of adhesive ligands to αIIbβ3 has been shown to result in dramatic conformational changes within the αIIbβ3 extracellular domain3 that, in a process likely involving ligand-binding–induced swing out of the β3 subunit hybrid domain and separation of integrin α and β subunit stalk domains,4 become propagated across the plasma membrane to the cytoplasmic face of the integrin. Binding of multivalent ligands like fibrinogen, fibronectin, and von Willebrand factor additionally results in clustering of integrin receptors.5 These events converge to initiate a series of biochemical and cell biological events at the cytosolic face of the integrin that ultimately lead to changes in cytoskeletal architecture, granule secretion, and further integrin activation that together serve to stabilize the platelet-platelet interactions that occur at sites of a growing thrombus. Outside-in signaling, therefore, contributes importantly to both thrombosis and hemostasis.

An extensive number of adaptor proteins, kinases, and phosphatases have been found to participate in αIIbβ3-mediated, adhesion-initiated signaling. In some cases, ligand binding induces association of the heterotrimeric guanine nucleotide-binding protein (G protein), Gα13, with the β3 cytoplasmic domain,6 where it activates integrin-associated Src-family kinases (SFKs) that go on to phosphorylate and activate a plethora of molecular targets.7 Of these, 2 tyrosine residues that reside within the immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM) of the cytoplasmic domain of Fc receptor γ-chain IIa (FcγRIIa) have been identified as SFK targets8 that, once phosphorylated, create a docking site for the tandem Src homology 2 (SH2) domains of the tyrosine kinase Syk.9 Activated Syk, in turn, goes on to amplify multiple pathways involved in integrin and platelet activation.10

The precise relationship between αIIbβ3 and Syk has been a subject of much interest in recent years. Early studies using overexpression systems and cultured cells found that the N-terminal SH2 domains of Syk could associate with the integrin β3 cytoplasmic domain in a phosphotyrosine-independent manner.11 More recent studies using mutant forms of Syk expressed in reconstituted murine hematopoietic cells, however, showed that the SH2 domains of Syk are indispensable for integrin-mediated outside-in signaling,12 implying that an ITAM-bearing protein might be involved in targeting Syk to the inner face of the plasma membrane, where it could both receive and send adhesion-initiated signals into the cell.

The observation13 that a monoclonal antibody (mAb) specific for FcγRIIa is able to inhibit adhesion-initiated tyrosine phosphorylation of FcγRIIa, Syk, and phospholipase Cγ2 (PLCγ2), as well as platelet spreading on immobilized fibrinogen, strongly suggested that a functional interplay between αIIbβ3 and FcγRIIa is required for optimal platelet function during thrombosis and hemostasis. The physiological significance of coupling between this integrin/ITAM pair, however, remains unknown. To explore the importance of FcγRIIa in platelet function, we compared the relative abilities of wild-type (WT) FcγRIIa-negative (FcγRIIaneg) and transgenic FcγRIIa-positive (FcγRIIaTGN = FcγRIIapos) murine platelets to support thrombosis and hemostasis in a number of well-accepted models of platelet function. The findings described herein establish FcγRIIa as a physiologically important functional conduit for αIIbβ3-mediated outside-in signaling, and suggest that modulating the activity of this novel integrin/ITAM pair might be effective in controlling thrombosis.

Materials and methods

Antibodies and reagents

The hybridoma cell line for the anti-FcγRIIa mAb, IV.3, was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Antibodies specific for Syk were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Antibodies specific for tyrosine-phosphorylated Syk tyrosine residues 525 to 526 and tyrosine-phosphorylated PLCγ2 tyrosine residue 759 were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). The antiphosphotyrosine mAb 4G10 was purchased from Millipore (Billerica, MA). Protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails were purchased from EMD Chemicals (San Diego, CA). Monovalent Fab fragments were prepared from mAb IV.3 and anti–platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule 1 (anti–PECAM-1) mAb 235.1 using a Fab preparation kit from Pierce Biotechnology (Rockford, IL). The synthetic peptide collagen-related peptide (CRP) was synthesized by the Protein Chemistry Core Laboratory at the Blood Research Institute, BloodCenter of Wisconsin.

Mouse strains

Mice were maintained in a facility free of known pathogens under the supervision of the Biomedical Resource Center at the Medical College of Wisconsin. Animal protocols were approved by the Medical College of Wisconsin Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. FcγRIIa transgene mice were generated in the laboratory of S.E.M.14 All of the FcγRIIa mice studied were littermates on a C57BL/6J background, and were compared with WT C57BL/6J littermates. Mouse genotypes were determined by polymerase chain reaction amplification of genomic tail DNA, and presence of FcγRIIa expression was confirmed by flow cytometry and western blot analysis of platelet lysates.

Blood collection

All human blood samples were donated as approved by the institutional review board of the BloodCenter of Wisconsin, and informed consent was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Blood from healthy volunteers free from medication for 2 weeks was collected into 90µM PPACK (D-phenylalanyl-L-prolyl-L-arginine chloromethyl ketone; EMD Chemicals, Philadelphia, PA). Mouse blood was drawn from the inferior vena cava of anesthetized mice into a syringe containing 3.8% sodium citrate (1/10 volume) or PPACK and heparin as anticoagulants.

Preparation of washed platelets

Whole blood drawn into 3.8% sodium citrate (1/10 volume) was diluted 1:1 with modified Tyrode-HEPES (Tyrode–N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N-2-ethanesulfonic acid) buffer (10mM HEPES [pH 7.4], 12mM NaHCO3, 137mM NaCl, 2.7mM KCl, 5mM glucose, 0.25% bovine serum albumin [BSA]). Diluted whole blood was supplemented with 50 ng/mL prostaglandin E1 (PGE1) and spun at 200g for 10 minutes. Platelet-rich plasma was collected, and after the addition of 50 ng/mL PGE1, platelets were pelleted at 750g for 10 minutes. Platelets were washed once in Tyrode-HEPES buffer containing 50 ng/mL PGE1 and 1mM EDTA, pH 7.4, and finally resuspended in Tyrode-HEPES to a final concentration of 3 × 108/mL.

Platelet spreading on immobilized fibrinogen

Eight-chamber glass tissue-culture slides (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) were coated overnight at 4°C with human fibrinogen (25 μg/mL), rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline, and blocked with 1% BSA (precleared using protein G beads) for 1 hour at room temperature. Washed platelets (200 µL) at a concentration of 2.5 × 107/mL in Tyrode buffer supplemented with 1mM CaCl2, 0.25 U/mL apyrase, and 10μM indomethacin were allowed to adhere to the immobilized fibrinogen for the indicated period of time. Nonadherent platelets were removed by gently rinsing 3 times. The remaining adherent platelets were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde for 20 minutes, permeabilized for 5 minutes at room temperature with 0.1% Triton X-100 in 100mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.4), 150mM NaCl, 10mM EGTA, 5mM MgCl2, containing 1× protease inhibitor cocktail, and stained with phalloidin tetramethylrhodamine isothiocyanate (1 µg/mL) for 60 minutes at room temperature in the dark. Samples were mounted in Vectashield mounting medium (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Images were acquired with a SenSys camera (Photometrics, Tucson, AZ) using an Axioscop microscope (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) with a 100× oil-immersion lens (1.3 numeric aperture; Carl Zeiss) and analyzed using Metamorph software (Universal Imaging, Downingtown, PA). Statistical analysis of the area occupied by spread platelets was performed using a 2-tailed Student t test for unpaired samples. For biochemical analysis, platelets were incubated at 37°C for 15, 30, and 45 minutes on 10-cm tissue-culture dishes and lysed directly with 2× lysis buffer (30mM HEPES [pH 7.4], 300mM NaCl, 20mM EGTA, 0.2mM MgCl2, 2% Triton X-100) containing 2× protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails, and subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis immunoblot analysis.

Platelet aggregation and clot retraction

Platelet aggregation was carried out using a whole-blood lumi-aggregometer (Chrono-Log). Washed platelets (300 µL) in Tyrode-HEPES containing 1mM CaCl2 were placed in a siliconized glass cuvette at 37°C with constant stirring at 1000 rpm. Platelet activation and secretion was initiated by addition of CRP, and platelets were allowed to aggregate for 10 minutes. For thrombin-induced clot retraction, washed platelets from WT or FcγRIIa transgenic mice were resuspended in plasma at a final concentration of 3 × 108/mL. Thrombin (0.2 U/mL) and CaCl2 (1mM) were added to initiate clot retraction.

In vitro thrombus formation under flow conditions

Thrombus formation was evaluated by a whole-blood perfusion assay over fibrillar collagen (Chrono-Log Corp, Havertown, PA) or collagen/fibrinogen (Enzyme Research Laboratories, South Bend, IN) coated microchannels under both arterial and venous shear conditions (shear rates of 2888 s−1 and 444 s−1, respectively). Briefly, Vena8 FLUORO+ Biochips (Cellix Ltd, Dublin, Ireland) were coated overnight at 4°C with either fibrillar collagen (50 μg/mL) or fibrinogen (25 μg/mL) and blocked with Hank balancing salt solution containing 0.1% BSA. Whole blood from WT and FcγRIIa transgenic mice was anticoagulated with heparin and PPACK, labeled with mepacrine (CalBiochem, La Jolla, CA), and perfused over protein-coated microchannels. For function-blocking studies, blood was preincubated with mAb IV.3 or isotype control Fabs before perfusing through the microchannels. Images of platelet adhesion and thrombus formation were acquired by epifluorescence microscopy in real time at a frame rate of one frame per second. Thrombus formation was determined as the mean percentage of total area covered by thrombi and as the mean integrated fluorescence intensity per micrometer squared. Image analysis was performed using Metamorph software (Universal Imaging).

Cremaster laser injury model

The studies on laser-induced thrombosis in the cremaster were performed as previously described.15 Briefly, FcγRIIa transgenic mice and WT mice were intraperitoneally injected with sodium pentobarbital (11 mg/kg; Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL), and maintained under anesthesia with the same anesthetic delivered via catheterized jugular vein. Platelet adhesion was studied in arterioles of the cremaster muscle using an Olympus BX61WI microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan or Center Valley, PA) with a 40×/0.8 numeric aperture water-immersion objective lens. Labeled antibodies specific for platelets and fibrin were introduced 5 minutes before injury, and laser injury was induced using an SRS NL100 Nitrogen Laser system (Photonic Instruments, St Charles, IL) as previously described.15 Data were collected for 2.5 minutes at 5 frames per second and then averaged at each time point. No more than 5 arteriole and 5 vein injuries were performed per mouse. Data were analyzed using Slidebook 5.0.0.17 software (Intelligent Imaging Innovations, Denver, CO).

Electrolytic injury thrombus studies

Electrolytic-induced vascular venous injury was performed as previously described16 using 10- to 12-week-old mice. Platelets labeled with rhodamine 6G and fibrin, identified with a fibrin-specific labeled antibody, were co-injected 5 minutes before injury. Electrolytic injury was created in femoral veins using a steel microsurgical needle applied to the outer surface of each vessel, with a 1.5-V positive direct current delivered for 30 seconds. Vessels were illuminated uniformly with beam-expanded green (532 nm) and red (650 nm) laser lights. Fluorescent images were captured over a 60-minute interval with a low-light video camera attached to an operating microscope at ×100 magnification; video images were quantitatively evaluated every 2 minutes for analysis of relative fluorophore intensity (Image J software, Research Services Branch, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) within the thrombus zone and normalized for interanimal comparisons.16 Venous thrombosis data were evaluated for statistical significance at the 60-minute time point using the Student t test.

Results

FcγRIIa enhances αIIbβ3-mediated outside-in integrin signaling in murine platelets

A growing number of blood and vascular cells have been shown to use ITAM-bearing adaptor proteins to transmit adhesion-initiated, integrin-mediated signals into cells.12,17 In human platelets, integrins α2β1 and α6β1, which mediate adhesion to the extracellular matrix proteins collagen and laminin, respectively, use the GPVI/Fc receptor γ-chain (FcRγ) complex for this purpose.18-20 The observation that a number of αIIbβ3-mediated outside-in signaling reactions can be inhibited by the anti-FcγRIIa function-blocking antibody, mAb IV.3,13 suggests that FcγRIIa might similarly function as an ITAM-bearing protein that transmits fibrinogen binding-induced activation signals into platelets.

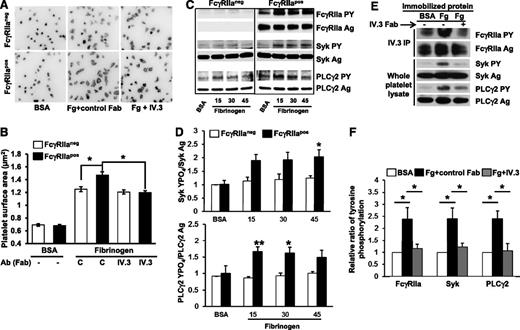

To examine the importance of FcγRIIa/αIIbβ3 stimulus-response coupling in platelet function, we took advantage of the fact that, unlike their human counterparts, WT mouse platelets are FcγRIIaneg,14 while transgenic mice harboring a human FcγRIIa transgene express this transmembrane receptor on the platelet surface at roughly the same density as exists on human platelets.14 We then subjected FcγRIIapos and FcγRIIaneg mice to a number of in vitro and in vivo models of thrombosis and hemostasis. As shown in Figure 1A-B, expression of FcγRIIa conferred a small, but significant, improvement in the ability of murine platelets to spread on immobilized fibrinogen–an increase that was abolished by prior addition of monovalent Fab fragments of mAb IV.3. Compared with FcγRIIaneg platelets, platelet expression of FcγRIIa significantly enhanced ligand binding-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of Syk and PLCγ2, 2 key players in integrin-mediated outside-in signal transduction (Figure 1C-D). As with human platelets,13 fibrinogen binding-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of FcγRIIa, Syk, and PLCγ2 in FcγRIIapos platelets could be inhibited by mAb IV.3 (Figure 1E-F). These data support the notion of FcγRIIa as an amplifier of adhesion-initiated signaling in platelets.

Ectopic expression of FcγRIIa in murine platelet enhances outside-in signaling initiated by platelet adhesion to immobilized fibrinogen. (A) Washed platelets from WT (FcγRIIaneg) and FcγRIIa transgenic (FcγRIIapos) mice were plated on BSA or fibrinogen-coated coverslips in the presence of apyrase (0.25 U/mL) and indomethacin (10μM) and allowed to spread for 45 minutes in the presence or absence of 10 μg/mL IV.3 Fab. After spreading, platelets were fixed, permeabilized, and stained with rhodamine-phalloidin to visualize F-actin. Images are representative of 3 independent experiments. (B) Platelet spreading was quantified using Metamorph software, with each bar representing the mean micrometers-squared ± SEM of at least 300 platelets. Note that FcγRIIapos platelets exhibit enhanced αIIbβ3-dependent spreading on fibrinogen, and preincubation of platelets with IV.3 Fab significantly inhibits FcγRIIapos platelet spreading on immobilized fibrinogen. (C-D) Washed platelets from WT and FcγRIIa transgenic mice were plated on BSA or fibrinogen-coated dishes and allowed to spread for 15, 30, or 45 minutes in the presence of apyrase (0.25 U/mL) and indomethacin (10μM). (C) After spreading, platelets were lysed and analyzed by western blotting with antibodies directed against either the antigen or phosphorylated forms of FcγRIIa, Syk, and PLCγ2. (D) Quantitation of the ratio of phosphorylated of Syk and PLCγ2 relative to total expression level. Results represent the mean ± SEM (n = 3 per group). Note that FcγRIIapos platelets show enhanced activation of Syk and PLCγ2 compared with FcγRIIaneg platelets. (E-F) Washed platelets from FcγRIIapos mice were plated on BSA- or fibrinogen-coated coverslips and allowed to spread for 45 minutes in the presence or absence of 10 μg/mL IV.3 Fab fragments. (E) FcγRIIa (top 2 panels) was analyzed after immunoprecipitation with mAb IV.3, while Syk and PLCγ2 (bottom 4 panels) were detected by western blot analysis of whole platelet detergent lysates. (F) Ratio of phosphorylated of Syk and PLCγ2 to total protein expression. Results represent the mean ± SEM (n = 3 per group). Note strong activation of FcγRIIa, Syk, and PLCγ2 after platelet binding to immobilized fibrinogen, and inhibition of this outside-in signaling circuit by IV.3 Fab. **P < .01, *P < .05.

Ectopic expression of FcγRIIa in murine platelet enhances outside-in signaling initiated by platelet adhesion to immobilized fibrinogen. (A) Washed platelets from WT (FcγRIIaneg) and FcγRIIa transgenic (FcγRIIapos) mice were plated on BSA or fibrinogen-coated coverslips in the presence of apyrase (0.25 U/mL) and indomethacin (10μM) and allowed to spread for 45 minutes in the presence or absence of 10 μg/mL IV.3 Fab. After spreading, platelets were fixed, permeabilized, and stained with rhodamine-phalloidin to visualize F-actin. Images are representative of 3 independent experiments. (B) Platelet spreading was quantified using Metamorph software, with each bar representing the mean micrometers-squared ± SEM of at least 300 platelets. Note that FcγRIIapos platelets exhibit enhanced αIIbβ3-dependent spreading on fibrinogen, and preincubation of platelets with IV.3 Fab significantly inhibits FcγRIIapos platelet spreading on immobilized fibrinogen. (C-D) Washed platelets from WT and FcγRIIa transgenic mice were plated on BSA or fibrinogen-coated dishes and allowed to spread for 15, 30, or 45 minutes in the presence of apyrase (0.25 U/mL) and indomethacin (10μM). (C) After spreading, platelets were lysed and analyzed by western blotting with antibodies directed against either the antigen or phosphorylated forms of FcγRIIa, Syk, and PLCγ2. (D) Quantitation of the ratio of phosphorylated of Syk and PLCγ2 relative to total expression level. Results represent the mean ± SEM (n = 3 per group). Note that FcγRIIapos platelets show enhanced activation of Syk and PLCγ2 compared with FcγRIIaneg platelets. (E-F) Washed platelets from FcγRIIapos mice were plated on BSA- or fibrinogen-coated coverslips and allowed to spread for 45 minutes in the presence or absence of 10 μg/mL IV.3 Fab fragments. (E) FcγRIIa (top 2 panels) was analyzed after immunoprecipitation with mAb IV.3, while Syk and PLCγ2 (bottom 4 panels) were detected by western blot analysis of whole platelet detergent lysates. (F) Ratio of phosphorylated of Syk and PLCγ2 to total protein expression. Results represent the mean ± SEM (n = 3 per group). Note strong activation of FcγRIIa, Syk, and PLCγ2 after platelet binding to immobilized fibrinogen, and inhibition of this outside-in signaling circuit by IV.3 Fab. **P < .01, *P < .05.

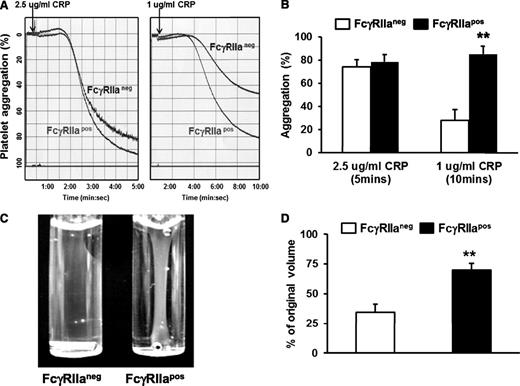

Previous loss-of-function studies have shown that blocking FcγRIIa with mAb IV.3 inhibits both aggregation of human platelets induced by low-dose platelet agonists21 as well as platelet-mediated retraction of a fibrin clot.13 To examine the hypothesis that addition of FcγRIIa to the platelet surface might conversely potentiate these reactions, we examined the relative ability of WT FcγRIIaneg vs littermate transgenic FcγRIIapos murine platelets to aggregate in response to low-dose agonists. As shown in Figure 2A-B, expression of FcγRIIa enhanced platelet aggregation in response to low-dose CRP. Similar results were obtained using low-dose thrombin as the agonist (not shown). FcγRIIapos murine platelets exhibited markedly enhanced ability to mediate clot retraction (Figure 2C-D). These gain-of-function studies demonstrate that FcγRIIa functions to amplify αIIbβ3-mediated outside-in signals into cells.

Ectopic expression of FcγRIIa potentiates platelet activation. (A) Representative aggregation tracings for WT FcγRIIaneg vs FcγRIIapos platelets in response to low- and medium-dose CRP. (B) Quantitation of platelet aggregation (mean percent aggregation ± SEM, n = 4 per group). (C) Representative photograph of thrombin-induced clot retraction. Washed platelets from WT or FcγRIIa transgenic mice were resuspended in plasma at a final concentration of 3 × 108/mL. Thrombin (0.2 U/mL) and CaCl2 (1mM) were added to initiate clot retraction. Images were taken 30 minutes later. (D) Quantification of plasma volume remaining following removal of the fibrin clot 30 minutes after initiation of the reaction. Results represent the mean ± SEM (n = 4 per group, **P < .01). Note that the presence of the FcγRIIa transgene enhances fibrin clot retraction at this early time point.

Ectopic expression of FcγRIIa potentiates platelet activation. (A) Representative aggregation tracings for WT FcγRIIaneg vs FcγRIIapos platelets in response to low- and medium-dose CRP. (B) Quantitation of platelet aggregation (mean percent aggregation ± SEM, n = 4 per group). (C) Representative photograph of thrombin-induced clot retraction. Washed platelets from WT or FcγRIIa transgenic mice were resuspended in plasma at a final concentration of 3 × 108/mL. Thrombin (0.2 U/mL) and CaCl2 (1mM) were added to initiate clot retraction. Images were taken 30 minutes later. (D) Quantification of plasma volume remaining following removal of the fibrin clot 30 minutes after initiation of the reaction. Results represent the mean ± SEM (n = 4 per group, **P < .01). Note that the presence of the FcγRIIa transgene enhances fibrin clot retraction at this early time point.

FcγRIIa amplifies thrombus formation in vitro

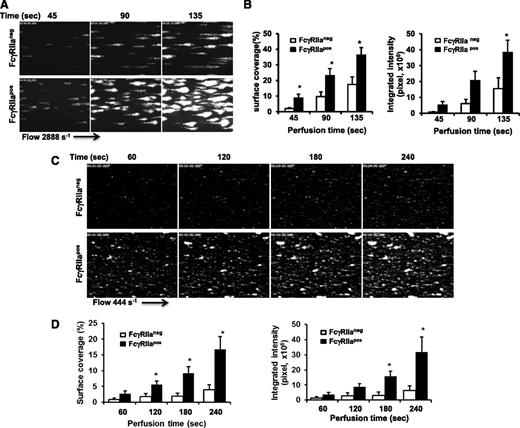

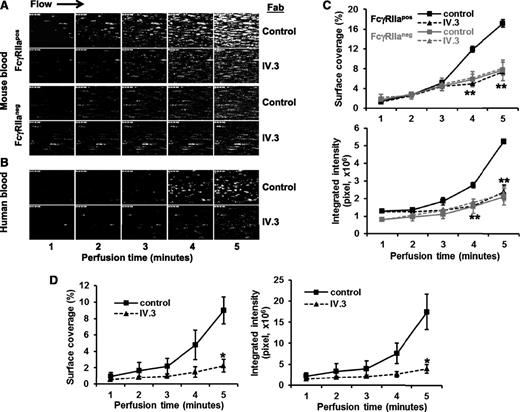

To examine the contribution of FcγRIIa to platelet function under conditions of flow, we analyzed platelet adhesion and thrombus formation on a fibrillar collagen-coated surface under conditions of both arterial and venous shear using a whole-blood microfluidic perfusion system. Platelets in whole blood were labeled with mepacrine, and accumulation of fluorescent platelets on collagen-coated (Figure 3) or collagen/fibrinogen-coated (Figure 4) surfaces was used to quantify adhesion and thrombus generation. As shown in Figure 3, thrombus formation was significantly enhanced in blood obtained from FcγRIIapos transgenic, compared with WT FcγRIIaneg, mice at both high (Figure 3A-B) and low (Figure 3C-D) shear (2888 s−1 and 444 s−1, respectively). That the enhanced thrombus formation was due solely to the presence of FcγRIIa was demonstrated by addition of the FcγRIIa-specific blocking antibody, mAb IV.3, which reduced the level of thrombus formation by FcγRIIapos platelets to that observed for FcγRIIaneg platelets (Figure 4A,C). IV.3 also reduced thrombus formation of human platelets (Figure 4B,D), which are also FcγRIIapos. Taken together with the results shown in Figure 1 obtained under static conditions, these data demonstrate that cooperative FcγRIIa/αIIbβ3 signaling plays a positive role in multiple in vitro models of platelet function.

FcγRIIa amplifies thrombus formation. Laminar flow chambers were coated with 50 µg/mL type I fibrillar collagen and blocked with Hank balancing salt solution containing 0.1% BSA. Whole blood from WT (FcγRIIaneg) and transgenic (FcγRIIapos) mice was anticoagulated with heparin and PPACK, labeled with mepacrine, and perfused under conditions of either arterial (2888 s−1) or venous (444 s−1) shear. Images of platelet adhesion and accumulation were acquired using epifluorescence microscopy in real time at a rate of 1 frame per second. (A,C) Representative time-course images of platelet adhesion and accumulation on collagen at a shear rate of 2888 s−1 (A) or 444 s−1 (C). (B,D) Quantification of platelet thrombi formed at 2888 s−1 (B) or 444 s−1 (D) was performed using Metamorph software. Results are expressed as the mean percentage of surface coverage (left panels) or total integrated fluorescence intensity (right panels) ± SEM (n ≥ 7 per group). Statistically significant differences between the means were determined using the Student t test. Note that thrombus formation was significantly increased (*P < .05) for FcγRIIapos platelets compared with their WT murine counterparts under conditions of both arterial and venous flow.

FcγRIIa amplifies thrombus formation. Laminar flow chambers were coated with 50 µg/mL type I fibrillar collagen and blocked with Hank balancing salt solution containing 0.1% BSA. Whole blood from WT (FcγRIIaneg) and transgenic (FcγRIIapos) mice was anticoagulated with heparin and PPACK, labeled with mepacrine, and perfused under conditions of either arterial (2888 s−1) or venous (444 s−1) shear. Images of platelet adhesion and accumulation were acquired using epifluorescence microscopy in real time at a rate of 1 frame per second. (A,C) Representative time-course images of platelet adhesion and accumulation on collagen at a shear rate of 2888 s−1 (A) or 444 s−1 (C). (B,D) Quantification of platelet thrombi formed at 2888 s−1 (B) or 444 s−1 (D) was performed using Metamorph software. Results are expressed as the mean percentage of surface coverage (left panels) or total integrated fluorescence intensity (right panels) ± SEM (n ≥ 7 per group). Statistically significant differences between the means were determined using the Student t test. Note that thrombus formation was significantly increased (*P < .05) for FcγRIIapos platelets compared with their WT murine counterparts under conditions of both arterial and venous flow.

Inhibition of thrombus formation by the anti-FcγRIIa mAb, IV.3. Whole blood drawn from healthy human volunteers or mice was incubated with mepacrine to label the platelets and then perfused over microchannels that had been coated with a mixed matrix composed of 50 μg/mL type I collagen and 25 μg/mL fibrinogen. Blood samples contained either 10 ug/mL mAb IV.3 Fabs or an isotype-matched control Fab, as indicated. Blood was initially perfused at a high shear rate 2888 s−1 for 3 minutes, and then adjusted down to 880 s−1 for an additional 3 minutes to emulate partial wound closure. Epifluorescent microscopic images of platelet adhesion and thrombus formation were acquired in rea time at a frame rate of 1 frame per second. (A) Shown is 1 of 3 time-course experiments of thrombi formed from whole blood derived from WT FcγRIIaneg and FcγRIIapos mice. (B) Time-course images of thrombi formed using human blood. The experiment shown is representative of 3 such experiments performed using blood from 3 different donors. (C-D) Quantification of platelet thrombi formed was performed using Metamorph software. Results are expressed as the mean percentage of surface coverage or total integrated fluorescence intensity ± SEM (n ≥ 3 per group). Statistically significant differences between the means were determined using the Student t test. *P < .05, **P < .01. Note that thrombus formation of both human platelets (which are FcγRIIa-positive) and FcγRIIa-positive (but not FcγRIIaneg) murine platelets is markedly reduced in the presence of mAb IV.3 Fabs.

Inhibition of thrombus formation by the anti-FcγRIIa mAb, IV.3. Whole blood drawn from healthy human volunteers or mice was incubated with mepacrine to label the platelets and then perfused over microchannels that had been coated with a mixed matrix composed of 50 μg/mL type I collagen and 25 μg/mL fibrinogen. Blood samples contained either 10 ug/mL mAb IV.3 Fabs or an isotype-matched control Fab, as indicated. Blood was initially perfused at a high shear rate 2888 s−1 for 3 minutes, and then adjusted down to 880 s−1 for an additional 3 minutes to emulate partial wound closure. Epifluorescent microscopic images of platelet adhesion and thrombus formation were acquired in rea time at a frame rate of 1 frame per second. (A) Shown is 1 of 3 time-course experiments of thrombi formed from whole blood derived from WT FcγRIIaneg and FcγRIIapos mice. (B) Time-course images of thrombi formed using human blood. The experiment shown is representative of 3 such experiments performed using blood from 3 different donors. (C-D) Quantification of platelet thrombi formed was performed using Metamorph software. Results are expressed as the mean percentage of surface coverage or total integrated fluorescence intensity ± SEM (n ≥ 3 per group). Statistically significant differences between the means were determined using the Student t test. *P < .05, **P < .01. Note that thrombus formation of both human platelets (which are FcγRIIa-positive) and FcγRIIa-positive (but not FcγRIIaneg) murine platelets is markedly reduced in the presence of mAb IV.3 Fabs.

Expression of FcγRIIa in platelets enhances thrombus formation in arterioles and fibrin generation in veins

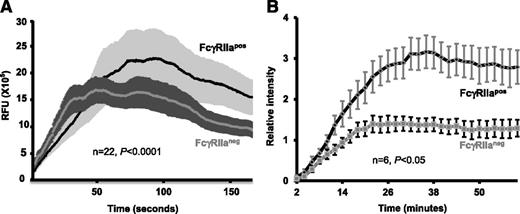

While platelets are a well-known component of arterial thrombi, evidence exists that activated platelets also participate importantly in the initiation of fibrin generation in large veins.16,22,23 To investigate whether the enhanced platelet activation conferred by FcγRIIa might be relevant under either arteriolar or venous conditions in vivo, we compared the extent to which FcγRIIaneg and FcγRIIapos platelets contribute to these processes using 2 distinct murine models of thrombus formation. In the first, FcγRIIapos transgenic mice and their WT FcγRIIaneg littermates were subjected to laser injury of their cremaster arterioles, and the rate and extent of platelet accumulation captured by video microscopy using previously described methods.15 As shown in Figure 5A, although the initial rate of platelet accumulation was similar in FcγRIIaneg and FcγRIIapos mice, the overall extent of thrombus growth was significantly enhanced in FcγRIIapos mice. To examine the contribution of integrin→ITAM signaling in platelets to fibrin generation under low-shear, venous conditions, we subjected these 2 mouse strains to electrolytic injury of the femoral vein.16 While platelet accumulation was comparable between FcγRIIaneg and FcγRIIapos platelets (not shown) fibrin accumulation was significantly enhanced in FcγRIIapos mice (Figure 5B), perhaps due to a greater degree of platelet activation in the FcγRIIapos mice leading to increased granule release, phosphatidylserine exposure, etc, in the fibrin-dominated venous thrombosis model. Taken together, these data support a role for FcγRIIa as a physiologically important amplifier of both arterial and venous thrombosis.

Expression of FcγRIIa enhances thrombus formation in arterioles and fibrin formation in veins. (A) Arteriolar laser injury: platelet accumulation. Kinetics of platelet accumulation in laser-injured arterioles. Cremaster muscle arteriole injury was induced using an SRS NL100 Nitrogen laser system. Average platelet accumulation was measured using an Alexa 488–labeled anti-CD41 Fab. Data were collected for 2.5 minutes at 5 frames per second and analyzed using Slidebook software. SE are shown as shaded areas. Note that platelet thrombus formation was markedly enhanced in FcγRIIapos, compared with FcγRIIaneg, mice, consistent with a dominant role for platelets in arterial injury. (B) Femoral vein electrolytic injury: fibrin accumulation. Kinetics of fibrin accumulation in electrolytically injured femoral veins. Electrolytic injury was induced by a positive direct current (1.5 V for 30 seconds) applied to the outer surface of the femoral vein using a steel microsurgical needle. Mice were preinjected with rhodamine 6G to label platelets, and fibrin was detected as described in “Materials and methods”. Fluorescent images were captured every 2 minutes for 60 minutes. Fluorophore intensity was measured within the thrombus zone and normalized for interanimal comparisons. The numbers of animals per group, and the P value calculated by the Student t test are indicated in each panel. Note that fibrin accumulation was markedly enhanced in FcγRIIapos, compared with FcγRIIaneg, mice, consistent with a dominant role for fibrin in venous injury.

Expression of FcγRIIa enhances thrombus formation in arterioles and fibrin formation in veins. (A) Arteriolar laser injury: platelet accumulation. Kinetics of platelet accumulation in laser-injured arterioles. Cremaster muscle arteriole injury was induced using an SRS NL100 Nitrogen laser system. Average platelet accumulation was measured using an Alexa 488–labeled anti-CD41 Fab. Data were collected for 2.5 minutes at 5 frames per second and analyzed using Slidebook software. SE are shown as shaded areas. Note that platelet thrombus formation was markedly enhanced in FcγRIIapos, compared with FcγRIIaneg, mice, consistent with a dominant role for platelets in arterial injury. (B) Femoral vein electrolytic injury: fibrin accumulation. Kinetics of fibrin accumulation in electrolytically injured femoral veins. Electrolytic injury was induced by a positive direct current (1.5 V for 30 seconds) applied to the outer surface of the femoral vein using a steel microsurgical needle. Mice were preinjected with rhodamine 6G to label platelets, and fibrin was detected as described in “Materials and methods”. Fluorescent images were captured every 2 minutes for 60 minutes. Fluorophore intensity was measured within the thrombus zone and normalized for interanimal comparisons. The numbers of animals per group, and the P value calculated by the Student t test are indicated in each panel. Note that fibrin accumulation was markedly enhanced in FcγRIIapos, compared with FcγRIIaneg, mice, consistent with a dominant role for fibrin in venous injury.

Although FcγRIIa binds with high affinity to the Fc region of aggregated immunoglobulin G (IgG), or to the Fc region of antigen-bound IgG immune complexes, it does not interact at all with monomeric IgG,24 the species that is present at 10 mg/mL in normal plasma. Platelets contain an additional pool of IgG in their α-granules,25 however, it is neither antigen-bound nor aggregated (H.Z. and P.J.N., unpublished observations, July 2012). Nevertheless, to eliminate the possibility that IgG/FcγRIIa interactions are contributing to, or responsible for, the amplification effects that we ascribe to integrin/ITAM connections, we crossed generated FcγRIIaTGN mice with μMT mice that lack B cells and all forms of immunoglobulin.26 As shown in supplemental Figure 1, platelets from these mice continue to both spread on immobilized fibrinogen and form thrombi under conditions of flow significantly better than their FcγRIIaneg counterparts and comparable with platelets from FcγRIIaTGN, IgG-containing mice. These data demonstrate that IgG does not contribute to the enhancement conferred by FcγRIIa on αIIbβ3-mediated outside-in signaling.

Discussion

Thrombus formation is a multistep process that involves GPIb-mediated tethering to von Willebrand factor presented on exposed collagen fibrils, integrin α2β1- and α6β1-mediated adhesion of platelets to collagen and laminin, activation, release, and generation of secondary platelet agonists that activate cell-surface G-protein–coupled receptors, conformational changes in the major platelet integrin αIIbβ3, and finally binding of the platelet-platelet bridging molecule, fibrinogen, to the platelet surface.27 Once the exposed extracellular matrix is coated with the primary layer of platelets, however, continued accumulation of platelets to form a stable thrombus requires sustained agonist-induced stimulation. Although the roles of soluble agonists like adenosine 5′-diphosphate, thromboxane A2, and thrombin in this process are well-appreciated and understood, the relative importance/contribution to the growth of a platelet thrombus of αIIbβ3-mediated outside-in signal transduction has been a matter of debate.

Although binding of soluble fibrinogen to αIIbβ3 requires that the integrin be transformed into an active, ligand-binding competent conformation,28 adhesion of resting platelets to immobilized fibrinogen, first described in the late 1960s,29 is unique in that it does not require activation of platelets30,31 and involves distinct adhesive sequences on the fibrinogen molecule.31 Fibrinogen, immobilized on the surface of already adherent platelets, likely represents one of the more abundant proteins that circulating platelets encounter as they approach a growing thrombus, and the adhesion-initiated signaling processes that ensue are composed of a series of downstream biochemical reactions that can be broken down into a series of temporally and spatially regulated events. Activation of integrin-associated SFKs,7,32 triggered either by microclustering of integrin receptors following the binding of a multivalent ligand,5 or if thrombin is present, catalyzed by β3-associated Gi13,6 is among the earliest detectable events. Soon afterwards SFK-mediated phosphorylation of multiple cellular targets, promotes the assembly of a nascent signaling complex at the inner face of the platelet plasma membrane that relays signals to the actin cytoskeleton, thereby driving the dynamic reorganizational events that lead to platelet spreading.33 The nonreceptor tyrosine kinase Syk is among the earliest targets of integrin-associated SFKs,10,34,35 and is recruited to the nascent αIIbβ3 signaling complex shortly after ligand binding.34 The molecular nature of the physical and functional linkage to αIIbβ3, however, has only been clarified in the last decade. Thus, although Syk has been shown to associate directly with the integrin β3 tail in transfected cell lines,11 Abtahian et al12 found that the SH2 domains of Syk were required for platelets to spread efficiently on immobilized fibrinogen. The finding by Boylan et al13 that the ITAM-bearing transmembrane adaptor molecule FcγRIIa efficiently recruits Syk to the nascent αIIbβ3 signaling complex—resulting in robust functional coupling between ligand binding and downstream events like platelet spreading and αIIbβ3–mediated clot retraction—added an important component to the outside-in signaling circuit. The present work extends these observations by demonstrating the physiological advantage imparted by FcγRIIa to platelet function under conditions of flow, both in vitro and in vivo.

The signaling circuit in platelets defined by ligand binding to αIIbβ3→integrin-associated SFKs→FcγRIIa ITAM phosphorylation→Syk recruitment and activation represents only one of a growing number of examples in which a cell-surface integrin enlists an ITAM-bearing protein to serve as a conduit for signal transduction into the cell. Though ITAM-containing adaptors have been known for many years to coordinate assembly and localization of macromolecular complexes following ligation of immunoreceptors in B cells, T cells, natural killer cells, and mast cells,36 there were hints of cross-talk between integrin and ITAM signaling as early as 1996, when it was shown that the ITAMs of the FcRγ chain become phosphorylated when platelets adhere to collagen.18 That integrins might as a rule, rather than as an exception, cooperate with ITAM-bearing proteins to transmit adhesion-initiated signals into the cell, however, was not appreciated until 7 years ago, when Abtahian et al12 found that intact SH2-domains of Syk were required for murine platelets to be able to spread efficiently on immobilized fibrinogen, followed by the report of Mócsai et al17 that β2 integrins on mouse neutrophils and macrophages use the FcRγ chain and/or the related ITAM-bearing adaptor molecule, DAP-12 for outside-in signaling. Other examples of integrin/ITAM connections continue to accumulate, including a report by Zou et al37 that αvβ3 in murine osteoclasts use the FcRγ-chain and DAP-12 to regulate bone resorption, and a more recent report by March et al38 that the integrin, αLβ2 (LFA-1) on natural killer cells enlists the T-cell receptor ξ-chain to effect granule polarization and degranulation. The entirety of integrin receptors that use ITAMs to co-opt Syk for outside-in signal transduction remains to be defined.

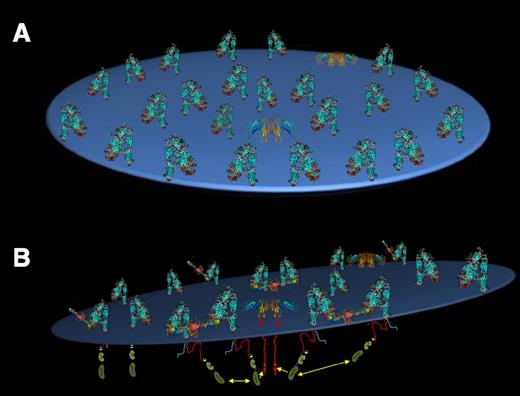

The spatial relationship between the FcγRIIa and the αIIbβ3 integrin complex that allows for their functional coupling (Figure 6) remains obscure. Despite there being only 2000 to 4000 FcγRIIa molecules on the surface of a platelet, FcγRIIa has been reported to be proximal to αIIbβ3,39 the GPIb complex,40 and PECAM-1.41 Were it to be highly mobile, FcγRIIa might be able to subserve so many different, and differently abundant, cell-surface receptors. Alternatively, subpopulations of FcγRIIa,21,42 GPIb,42 and PECAM-143 have all been reported to be enriched in lipid rafts. There is no evidence, however, that αIIbβ3 ever becomes raft localized. They are likely to need to be proximal to each other at some point for signal amplification to occur. However, the FcγRIIa-mediated amplification of Syk phosphorylation that occurs when platelets encounter immobilized fibrinogen (Figure 1) does not occur when fibrinogen binds in such a way as to minimize multivalent ligand-binding–induced transactivation of integrin-associated SFKs: that is, when fibrinogen binds to activated platelets in the absence of stirring (supplemental Figure 2). Whether FcγRIIa becomes physically associated with αIIbβ3 to amplify αIIbβ3 outside-in signaling and the nature of their physical association, if any, is unknown.

Schematic model of αIIbβ3/FcγRIIa signaling in platelets. (A) Top view. (B) Side view. The integrin, which outnumbers FcγRIIa by more than 20:1, is shown in its bent, inactive conformation, which is still capable of binding immobilized, multivalent fibrinogen molecules. Ligand-binding–induced cross-linking of adjacent integrins leads to trans-activation of integrin β-subunit cytoplasmic domain-associated Src family kinases, a subset of which happen to be proximal to the cytoplasmic domain of FcγRIIa ITAM tyrosine residues. Their phosphorylation creates a docking site for the tyrosine kinase Syk, thereby completing transmission of the activation signals initiated by fibrinogen binding to the extracellular domain of αIIbβ3.

Schematic model of αIIbβ3/FcγRIIa signaling in platelets. (A) Top view. (B) Side view. The integrin, which outnumbers FcγRIIa by more than 20:1, is shown in its bent, inactive conformation, which is still capable of binding immobilized, multivalent fibrinogen molecules. Ligand-binding–induced cross-linking of adjacent integrins leads to trans-activation of integrin β-subunit cytoplasmic domain-associated Src family kinases, a subset of which happen to be proximal to the cytoplasmic domain of FcγRIIa ITAM tyrosine residues. Their phosphorylation creates a docking site for the tyrosine kinase Syk, thereby completing transmission of the activation signals initiated by fibrinogen binding to the extracellular domain of αIIbβ3.

In addition to the functional coupling between αIIbβ3 and FcγRIIa described herein, focal adhesion kinase (FAK) pp125FAK has also been shown to play a key role in mediating outside-in signaling downstream of integrin engagement. A 125-kDa nonreceptor protein-tyrosine kinase that was first described in 1992, FAK has been shown in platelets to play a prominent role in integrin-mediated signaling and thrombus stability,44 functions that have been ascribed (at least in part) to its ability to interact with the Arp2/3 complex and orchestrate actin assembly during the process of filopodial and lamellipodial protrusion.45 Ligand binding to αIIbβ3 triggers autophosphorylation of FAK Y39733 in a reaction that some investigators find dependent on costimulation with other agonist receptors. FAK Y397, in turn, is able to recruit and activate nearby Src-family kinases, which in turn phosphorylate the kinase domain of FAK, further activating it.46 Curiously, the inability of platelets missing components of the integrin/ITAM signaling pathway to spread on fibrinogen is phenocopied in FAK-deficient murine platelets.44 Whether the integrin/ITAM and integrin/FAK pathways intersect to mediate outside-in signaling events leading to platelet spreading and thrombus stability, however, is not yet known.

Finally, while the development of effective fibrinogen receptor antagonists has been a major advance in the management of coronary artery diseases,47 these agents have been shown to increase the incidence of clinically significant thrombocytopenia and bleeding48 and a few reports suggest that thrombosis might also be an additional rare complication of eptifibatide therapy.49 Improved understanding of the molecular components that mediate αIIbβ3 outside-in signaling has the potential to lead to identification of new therapeutic targets like FcγRIIa, the intervention of which might be effective in inhibiting the later stages of thrombus formation (ie, recruitment of resting platelets to fibrinogen-coated platelets) without affecting initial platelet adhesion or repair at sites of vascular damage.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is an Inside Blood commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Jimmy Crockett for development of the microfluidic system during the early stages of this investigation, and Dr Demin Wang for helpful discussions and for providing the µMT mice.

This work was supported by grants HL-44612 (P.J.N.) and P01HL110860 (M.P.) from the Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health.

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: H.Z. designed and performed research, analyzed results, and wrote the manuscript; L.R., V.H., C.G., B.B., and B.C.C. performed research and analyzed results; D.K.N. analyzed results; S.E.M. contributed transgenic mice lines and analyzed results; M.P. designed research and analyzed results; and P.J.N. designed research, analyzed results, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: P.J.N. is a member of the scientific advisory boards of the New York Blood Center, the Puget Sound Blood Center, and Children’s Hospital of Boston. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Peter J. Newman, PhD, BloodCenter of Wisconsin, Blood Research Institute, 638 North 18th St, Milwaukee, WI 53201; e-mail: peter.newman@bcw.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal