Key Points

Whole exome sequencing reveals novel mutations in ARAF that activate the kinase and are inhibitable by vemurafenib in a patient with LCH.

Requiring the presence of BRAF V600E in LCH to qualify for rat fibrosarcoma inhibitor treatment may be overly exclusionary.

Abstract

The extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) signaling pathway is activated in Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) histiocytes, but only 60% of cases carry somatic activating mutations of BRAF. To identify other genetic causes of ERK pathway activation, we performed whole exome sequencing on purified LCH cells in 3 cases. One patient with wild-type BRAF alleles in his histiocytes had compound mutations in the kinase domain of ARAF. Unlike wild-type ARAF, this mutant was a highly active mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase in vitro and was capable of transforming mouse embryo fibroblasts. Mutant ARAF activity was inhibited by vemurafenib, a BRAF inhibitor, indicating the importance of fully evaluating ERK pathway abnormalities in selecting LCH patients for targeted inhibitor therapy.

Introduction

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is characterized by the inappropriate accumulation of cells that share phenotypic characteristics with Langerhans cells, the primary antigen-presenting cells of skin and mucosa.1-3 The disease has a broad spectrum of clinical behaviors, from a mild self-limited version to an aggressive form associated with a 20% mortality. Treatment has generally been empiric. Mild disease responds to intralesional steroids or systemic therapy with vinblastine plus steroids. Combination antineoplastic therapies have been used with some success against more aggressive forms, but they are associated with substantial toxicity and some patients are refractory.4

The discovery of somatic activating BRAF mutations—in particular, but not exclusively, BRAF V600E—in 50% to 60% of patients with LCH has brought the promise of targeted therapeutics to these patients.5-8 A recent report describes clinical responses to vemurafenib, a BRAF inhibitor, in patients with a mixture of LCH and Erdheim-Chester disease,9 another disorder associated with BRAF V600E,10 suggesting that BRAF V600E is a driver mutation in LCH. However, the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) signaling pathway is activated in pathologic histiocytes of all LCH patients including those with wild-type BRAF alleles.5 To discover other genetically driven mechanisms for activating ERK signaling in LCH, we performed whole exome sequencing on DNA from purified lesional CD1a+ LCH cells and normal cells from 3 LCH patients.

Study design

Patients and samples

LCH patients whose materials were analyzed by whole exome sequencing were enrolled at Willem Alexander Children’s Hospital/Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden (patients 1 and 2) or the Emma Children’s Hospital/Academic Medical Center, Amsterdam (patient 3). Clinical characteristics are described in supplemental Materials available on the Blood Web site. Snap frozen LCH-affected tissue biopsies were obtained either at diagnosis (patients 1 and 2) or after LCH reactivation (patient 3). CD1a-positive cells were isolated by fluorescence-activated cell sorter. Buccal swabs (patients 1 and 2) or peripheral blood cells (patient 3) were collected in parallel as a source of germ-line DNA. All LCH patients, or their parents in the case of patients <12 years of age, provided written informed consent for the study, which was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Leiden University Medical Center. An additional 52 LCH samples for targeted analysis of ARAF and BRAF abnormalities were obtained from the Departments of Pathology at Brigham & Women’s Hospital and Boston Children’s Hospital (discarded specimens) or Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, and Academic Medical Center, Amsterdam. The latter samples were handled according to the Dutch code of proper secondary use of human material as accorded by the Dutch Society of Pathology (www.federa.org). The samples were handled in a coded (pseudonymized) fashion according to the procedures as accorded by the Leiden University Medical Center ethical board. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Exome sequencing and analysis

Sequencing libraries were synthesized from 50 ng of fragmented genomic DNA using an Illumina Truseq Library kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA). Two libraries were pooled at equimolar concentrations for exome enrichment using the Agilent SureSelect all exon v 2.0 hybrid capture kit. Enriched pools were combined and sequenced in 3 lanes to a total lane equivalent of 0.5 lane per exome on a HiSequation 2000 (Illumina) in a 2 × 100-bp pair-end mode. Pooled sample reads were de-convoluted (de-multiplexed) using PICARD tools (http://picard.sourceforge.net/command-line-overview.shtml), aligned to the Human Genome Reference sequence (b37 edition) using bwa (http://bio-bwa.sourceforge.net/bwa.shtml), filtered for duplicate reads, and analyzed for quality using Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK) (http://www.broadinstitute.org/gsa/wiki/index.php/Base_quality_score_recalibration) and PICARD tools. Variant analysis was performed using cancer-specific variant discovery tools (GATK),11 including MuTect12 for somatic base substitutions and indelocator for short insertions and deletions (http://www.broadinstitute.org/cancer/cga/indelocator). Lane performance criteria are described in supplementas Materials.

Validation assays

Additional samples were analyzed for the presence of mutations in ARAF and BRAF using either Sequenom allelotyping as described previously5 or a custom-designed Illumina-based targeted sequencing panel described in supplemental Methods.

ARAF and BRAF vectors and mutagenesis

Human ARAF variants were created by restriction site-directed or primer extension mutagenesis and then cloned into pCMV6-Entry containing a C-terminal DDK (FLAG) epitope tag (Origene, Rockville, MD).

In vitro kinase assays

ARAF- and BRAF-containing expression vectors were transfected into HEK293T cells using FuGENE HD Transfection Reagent (Promega, Madison, WI). To maximize rat fibrosarcoma (RAF) kinase activation, cells were cotransfected with activated mutant Harvey rat sarcoma oncogene (H-Ras) (pcDNA3-H-Ras-V12; Addgene, Cambridge, MA) and activated cellular Rous sarcoma virus oncogene (c-Src) Y527F (pcSrc527; Addgene).13 Forty-eight hours later, lysates were subjected to immune precipitation. Inactive glutathione S-transferase–mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MEK)1 protein (Millipore, Bedford, MA) or inactive glutathione S-transferase-mitogen-activated protein kinase 2/Erk2 protein (Millipore) were added to immunoprecipitated ARAF or BRAF along with ATP, and kinase reactions were allowed to proceed for 30 minutes. Phosphorylated products were identified by immunoblot. For inhibition studies, vemurafenib (Selleckchem, Houston, TX) in dimethylsulfoxide was added directly to the kinase mixture.

Soft agar assay

Balb/c 3T3 cells (clone A31) were transfected with the indicated expression vectors. G418-resistant cells were suspended in top agar (0.33% Select Agar; Life Technologies) and plated over base agar (0.5%). Colonies were counted using a dissecting microscope after 22 days of culture.

Results and discussion

To identify possible genetic drivers of LCH, we sequenced exomes from purified CD1a-positive lesional cells and normal leukocytes or buccal cells of 3 patients. All 6 samples met quality standards for paired-end library synthesis, and 80% of all targets were covered to a depth of at least 30×; mean target coverage was 196× (range, 178-227×). Massively parallel sequencing revealed 18 nonsynonymous base changes in the 3 LCH samples that were not present in matched germ-line DNA (supplemental Table 1). BRAF V600E was identified in the lesional DNA of patient 2 with an allelic fraction of 45%. BRAF exons were wild type in the lesional DNA of patients 1 and 3. No other obviously relevant variants were observed in the DNA from patient 3. However, the LCH cells from patient 1 contained a somatic single nucleotide variant in ARAF with an allele frequency of 63%: g.47426808C>G [NM_001654.2(ARAF_v001):c1053C>G], which is predicted to result in a substitution of leucine for phenylalanine at amino acid position 351 (F351L). This sample also showed a 6 nucleotide deletion at position 47 426 794 [NM_001654.4(ARAF_v001):c.1044_1049del], which is predicted to result in an in-frame loss of amino acids 347 and 348 (Q347_A348del). Neither alteration appears in any human sequence database. Informatics analysis indicated that the single nucleotide variant and the deletion were only observed on the same chromosome, indicating that both abnormalities occurred in the same allele. This inference is consistent with the fact that ARAF maps to the X chromosome and that patient 1 was male. Both abnormalities were validated using an orthogonal allelotyping technology, namely Sequenom.14 The ARAF abnormalities were not detected by Sequenom genotyping or Illumina sequencing in an additional 44 LCH samples, of which 23 were wild type for BRAF (supplemental Methods).

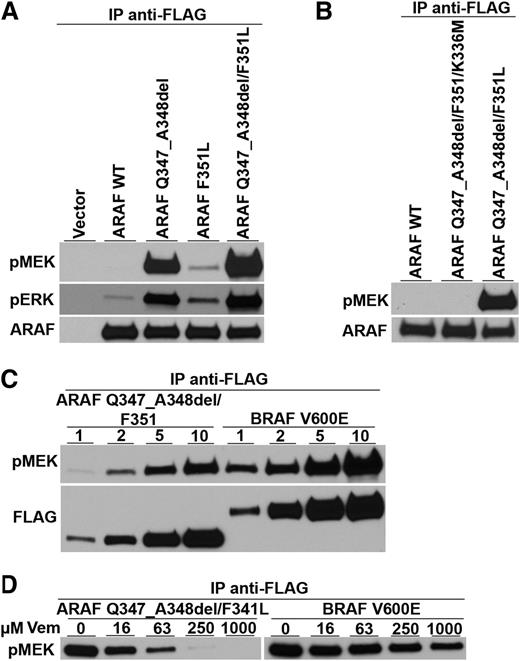

Because nearly all LCH samples show activation of the ERK signaling pathway regardless of BRAF mutational status, the results from patient 1 suggest that mutant ARAF might be involved in ERK pathway activation. However, even though ARAF mutations have been described in cancer,15,16 none have been reported to enhance its kinase activity. In fact, other ARAF mutations found in cancer inactivate the kinase,17,18 and structural studies suggest that, in contrast to BRAF, mutations in ARAF cannot easily activate its kinase.19,20 Therefore, to determine the likelihood that the ARAF variant found in patient 1 could be a pathogenetic driver of LCH, we tested its MEK kinase activity. ARAF-encoding cDNAs were prepared with the F351L substitution and the deletion of amino acids 347 and 348 both separately and together. After transfection into HEK293T cells, immune precipitates containing ARAF were tested for their ability to phosphorylate a synthetic MEK substrate in vitro. The double ARAF mutant (containing both F351L and Q347_A3438del) had substantial MEK kinase activity, whereas wild-type ARAF’s activity was nearly undetectable (Figure 1A). ARAF containing only the deletion mutant had approximately half the kinase activity of the double mutant and the F351L mutant had low but detectable activity.

Kinase activity and vemurafenib sensitivity of an ARAF variant discovered in a LCH patient with wild-type BRAF alleles. (A) Expression vectors encoding wild-type ARAF (ARAF WT), the 6 nucleotide deletion mutation encoding Q347_A348del, the single nucleotide variant encoding the single amino acid substitution F351L, and both ARAF mutations (as discovered in the patient sample) were transfected into HEK293 cells along with activated Src and H-Ras to maximize ARAF activation.13 All proteins were tagged with the FLAG epitope. Anti-FLAG immune precipitates were tested for their ability to phosphorylate an artificial MEK substrate in vitro and for activated MEK to phosphorylate artificial ERK. Immunoblots show the presence of phospho-MEK (pMEK), phospho-ERK (pERK), and total ARAF protein (ARAF) and demonstrate the ability of the mutated versions of ARAF to phosphorylate MEK. (B) Substitution of methionine for lysine at position 336 in the ARAF mutant (ARAF Q347_A348del/F351L/K336M), which is known to destroy ARAF kinase activity, prevents the mutant from phosphorylating MEK. (C) Comparison of mutant ARAF kinase activity to BRAF V600E kinase activity shows that ARAF kinase activity is only a little lower than that of BRAF V600E. (Note that lower amounts of ARAF were loaded on this gel compared with BRAF.) (D) Increasing amounts of the kinase reaction mixture (1, 2, 5, and 10 µL) were analyzed by immunoblot for phospho-MEK (pMEK) and total ARAF or BRAF as detected by FLAG immunoblotting. Adding increasing amounts of vemurafenib (Vem) (final concentrations of 0, 16, 63, 250, and 1000 µM) inhibited both the mutant ARAF and BRAF V600E kinase activities.

Kinase activity and vemurafenib sensitivity of an ARAF variant discovered in a LCH patient with wild-type BRAF alleles. (A) Expression vectors encoding wild-type ARAF (ARAF WT), the 6 nucleotide deletion mutation encoding Q347_A348del, the single nucleotide variant encoding the single amino acid substitution F351L, and both ARAF mutations (as discovered in the patient sample) were transfected into HEK293 cells along with activated Src and H-Ras to maximize ARAF activation.13 All proteins were tagged with the FLAG epitope. Anti-FLAG immune precipitates were tested for their ability to phosphorylate an artificial MEK substrate in vitro and for activated MEK to phosphorylate artificial ERK. Immunoblots show the presence of phospho-MEK (pMEK), phospho-ERK (pERK), and total ARAF protein (ARAF) and demonstrate the ability of the mutated versions of ARAF to phosphorylate MEK. (B) Substitution of methionine for lysine at position 336 in the ARAF mutant (ARAF Q347_A348del/F351L/K336M), which is known to destroy ARAF kinase activity, prevents the mutant from phosphorylating MEK. (C) Comparison of mutant ARAF kinase activity to BRAF V600E kinase activity shows that ARAF kinase activity is only a little lower than that of BRAF V600E. (Note that lower amounts of ARAF were loaded on this gel compared with BRAF.) (D) Increasing amounts of the kinase reaction mixture (1, 2, 5, and 10 µL) were analyzed by immunoblot for phospho-MEK (pMEK) and total ARAF or BRAF as detected by FLAG immunoblotting. Adding increasing amounts of vemurafenib (Vem) (final concentrations of 0, 16, 63, 250, and 1000 µM) inhibited both the mutant ARAF and BRAF V600E kinase activities.

RAF family members form homo- and heterodimers with each other and can influence the kinase of activities of their bound partners.18,21,22 Although we did not detect BRAF in ARAF immune precipitates, we nonetheless confirmed that the double mutant’s enhanced MEK kinase activity was an inherent property of the mutant ARAF protein by engineering a “kinase-dead” version of the double mutant (K336M).18 This protein had no detectable MEK kinase activity, suggesting that the 2 mutations directly enhance ARAF kinase activity (Figure 1B). The MEK kinase activity of the double ARAF mutant appears to be slightly less than that of BRAF V600E (Figure 1C). However, like BRAF V600E, the double ARAF mutant’s MEK kinase activity is inhibited by vemurafenib, a drug approved for the treatment of BRAF V600E-positive melanoma (Figure 1D).23

Finally, we tested the neoplastic transforming activity of the double ARAF mutant. Because no Langerhans cell lines exist, we could not test transforming activity in the most relevant cell type. Instead, we used Balb/c 3T3 mouse fibroblasts (clone A31), which are tightly growth regulated and unable to grow in soft agar. Transfecting these cells with an expression vector encoding the double ARAF mutant induced these cells to grow in suspension, indicating that the ARAF mutant has transforming activity (Table 1).

Soft agar colony formation

| Colonies/4 cm2 (mean ± standard deviation) . | |

|---|---|

| Wild-type ARAF | ARAF Q347_A348del/F351L |

| 0 ± 0 | 102.5 ± 8.5 |

| Colonies/4 cm2 (mean ± standard deviation) . | |

|---|---|

| Wild-type ARAF | ARAF Q347_A348del/F351L |

| 0 ± 0 | 102.5 ± 8.5 |

Balb/c 3T3 cells (clone A31) were transfected with expression vectors encoding wild-type ARAF or ARAF containing the Q347_A348 deletion and the F351L substitution. Cells were seeded in 0.33% agar in complete growth medium. After 22 d in culture, the number of colonies with diameter >0.2 mm was counted over a 4-cm2 area using a dissecting microscope. Means and standard deviations based on 2 wells are shown.

Although the full picture of molecular events that lead to LCH remains unclear, there appears to be significant selective pressure for activating the ERK signaling pathway. More than 60% of LCH samples achieve this through somatic activating mutations of BRAF.5 The vast majority involves the thymine to adenine transversion at nucleotide position 1799, which produces BRAF V600E. Two additional somatic BRAF mutations have been observed in LCH that also activate the kinase: BRAF 600DLAT (an insertional mutant)7 and V600D, which occurs in melanoma.6 The ARAF mutations in the sample from patient 1 provide an unexpected and novel mechanism for ERK pathway activation.

These findings sound a note of caution for the selection of patients to receive targeted therapies. Most trials of BRAF inhibitors for LCH require somatic BRAF V600E for enrollment, and most practitioners would not treat LCH patients with Food and Drug Administration-approved BRAF inhibitors in the absence of this mutation. Although it is difficult to predict clinical behavior based on in vitro analyses, our results suggest that the ARAF variant we describe might be a driver of LCH in patient 1 and that its activity might be inhibited by vemurafenib. However, this patient’s wild-type BRAF alleles would have precluded his treatment with BRAF antagonists. This highlights the importance of finding a way to incorporate broadly based screening in the management of patients who might benefit from molecularly targeted therapies.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is an Inside Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the insights and ideas of Dr Mark D. Fleming and technical support provided by Inge Briaire and Sarah Ouahoud.

The authors acknowledge support from the Histiocytosis Association, Team Ippolittle/Deloitte of the Boston Marathon Jimmy Fund Walk, Stichting 1000 Kaarsjes voor Juultje, the Say Yes to Education foundation, and Mr George Weiss.

Authorship

Contribution: D.S.N. constructed ARAF mutant cDNAs, designed and performed in vitro kinase assays, and designed and performed soft agar transformation assay; W.Q. purified patient cellular material and extracted genomic DNA; G.B.-V. assisted in optimization of DNA extraction from patient material in the original sequencing set and extracted DNA from patient material in the validation set; A.G.S.v.H. identified patients and oversaw collection and purification of patient material; C.v.d.B. identified patients and provided patient material; J.V.M.G.B. provided archived tissues and marked CD1a-rich areas in these biopsies; S.Y.T. provided technical assistance for the in vitro kinase assays; P.V.H. performed whole exome sequencing and prepared the sequencing report; M.D. performed informatics analysis on sequencing results; LE.M. oversaw and contributed to sequencing performance and analysis; R.M.E. oversaw and developed capabilities for LCH patient identification and tissue acquisition and storage; and B.J.R. conceived and designed the project.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Barrett J. Rollins, Department of Medical Oncology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, 450 Brookline Ave, Boston, MA 02215; e-mail: barrett_rollins@dfci.harvard.edu.

References

Author notes

R.M.E. and B.J.R. contributed equally to this work.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal