Key Points

Loss of Ku70 results in loss of HSC quiescence, which correlates with loss of HSC maintenance.

Bcl2 overexpression rescues HSC defects in Ku70−/− mice by restoring quiescence, without restoration of DNA repair capacity.

DNA repair is essential for hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) maintenance. Ku70 is a key component of the nonhomologous end-joining pathway, which is the major pathway for DNA double-strand break repair. We find that HSCs from Ku70-deficient mice are severely defective in self-renewal, competitive repopulation, and bone marrow (BM) hematopoietic niche occupancy and that loss of quiescence results in a dramatic defect in the maintenance of Ku70-deficient HSCs. Interestingly, although overexpression of Bcl2 does not rescue the severe combined immunodeficiency phenotype in Ku70-deficient mice, overexpression of Bcl2 in Ku70-deficient HSCs almost completely rescued the impaired HSC quiescence, repopulation, and BM hematopoietic niche occupancy capacities. Together, our data indicate that the HSC maintenance defect of Ku70-deficient mice is due to the loss of HSC quiescent populations, whereas overexpression of Bcl2 rescues the HSC defect in Ku70-deficient mice by restoration of quiescence. Our study uncovers a novel role of Bcl2 in HSC quiescence regulation.

Introduction

Genomic integrity is essential for organism development and longevity and has recently been recognized as critical for the maintenance of stem cell populations.1,,,-5 Eukaryotic cells maintain genomic integrity by utilizing multiple DNA repair pathways,6 and emerging evidence supports the hypothesis that DNA repair is also crucial for maintaining hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) function.7

HSC function is closely coupled to the cells’ unique cell-cycle kinetics, in which adult HSCs are predominantly quiescent, undergoing proliferation in response to stress. Increased proliferation or loss of quiescence in HSCs correlates with loss of HSC function.8,,-11 Although a variety of molecules regulate HSC quiescence,12,-14 DNA-repair pathways have not been implicated in HSC quiescence regulation directly.

DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) are perhaps the most harmful type of DNA damage. DSBs can be induced by ionizing radiation, the byproducts of cellular metabolism (reactive oxygen species), or during V(D)J recombination in T and B lymphocytes.15 Mammalian cells employ 2 major mechanisms for DSB repair: homologous recombination (HR) and nonhomologous end-joining (NHEJ).16,17 HR can be error-free and is only operative in the S/G2 phases of the cell cycle when a sister chromatid is available. NHEJ is error-prone and functions in all phases of the cell cycle. When a DSB occurs, the broken ends are held in close proximity by the Ku70-Ku80 heterodimer and DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit (DNA-PKcs), forming the DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNA-PK) complex. The kinase activity of the DNA-PK complex is activated by Artemis nuclease and the repair process is completed by XRCC4–DNA ligase IV–mediated DNA ligation.18 Defects in NHEJ result in marked sensitivity to ionizing radiation and immunodeficiency. In humans, 15% of severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) cases are associated with inherited defects in NHEJ.19 Mice deficient in NHEJ components are viable and hypersensitive to irradiation and show a SCID phenotype.20,,,-24

NHEJ is the preferential repair mechanism in resting HSCs in response to DSBs.25 NHEJ components are also required for HSC maintenance. Ku80-deficient HSCs have attenuated self-renewal and ultimately stem cell functional exhaustion.26 Mice with a hypomorphic mutation in DNA ligase IV have diminished DSB repair activity and progressively lose HSCs during aging. In addition, HSCs with the hypomorphic Lig4Y288C mutation display increased proliferation and impaired maintenance.22 However, the mechanism by which the NHEJ pathway regulates HSC function is not clear.

Bcl2 is a prototypical oncogene. It was discovered at the t(14;18) translocation breakpoint in human B-cell follicular lymphomas and overexpression of Bcl2 is one of the major oncogenic driver mechanisms in lymphomas and leukemias.27,-29 The antiapoptotic function of Bcl2 has been well established,30,31 and the antiapoptotic function of Bcl2 in HSCs has also been demonstrated in Bcl2 transgenic mice, which have increased HSC pools and are resistant to irradiation.32,33

Overexpression of Bcl2 has also shown significant impact on proliferation. Overexpression of Bcl2 delays G0/1-S transition in T cells, and Bcl2-deficient T cells demonstrate accelerated cell-cycle progression.34 In FDC-P1 cells following interleukin-3 withdrawal, Bcl-2–expressing cells rapidly arrested in the G1/0 phase and were refractory to restimulation with interleukin-3.35 Similarly, in NIH3T3 fibroblasts, Bcl2 overexpression accelerates withdrawal into G0 after growth factor deprivation and delays S-phase entry after restimulation with growth factors.36 These findings suggest that Bcl-2 overexpression regulates cellular proliferation by controlling the G0 to G1 transition.37 However, the antiproliferation function of Bcl2 in HSCs has not been examined.

Here, we use Ku70-deficient mice as a model to examine the role of NHEJ in HSC quiescence, maintenance, and function and demonstrate that lack of Ku70 results in loss of HSC quiescence. More interestingly, overexpression of Bcl2 promotes HSC quiescence and rescues the HSC defects in Ku70-deficient mice.

Methods

Mice

The C57BL/6 (CD45.2), congenic strain B6.SJL-PtprcaPep3b/BoyJ (BoyJ, CD45.1), and transgenic green fluorescent protein (GFP) mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. Ku70+/− mice were kindly provided by Dr Alt,21 and transgenic Bcl2 mice under H2-K promoter have been described previously.33 All mice were housed in a specific-pathogen–free facility. Unless otherwise stated, all mice were studied between 8 and 16 weeks of age. All mouse studies were approved by the institutional animal care and use committee at Case Western Reserve University (Cleveland, OH).

Hematology

Peripheral blood (PB) was obtained from the retro-orbital sinus using microcapillary tubes. For blood cell counts, the Coulter counter Z2 (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA) was used. Bone marrow (BM) was harvested from both hindlimbs (tibias and femurs) of mice, and total nucleated cell numbers were counted using a hemacytometer.

Flow cytometry and cell sorting

Flow cytometry was performed on a BD LSRI or LSRII (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), and data were analyzed using FlowJo software (TreeStar, Ashland, OR). Antibodies included CD45.2, CD45.1, Ly-6G (Gr-1), CD11b (Mac-1), CD45R/B220, CD4 (L3T4), CD8 (Ly2), Ter119/Ly76, Sca1 (Ly-6A/E), c-Kit (CD117), CD34, Flk2, CD48 (BD Bioscience), and CD150 (Biolegend).

BD Aria was used for cell sorting. BM cells were lineage depleted using a lineage-depletion kit (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA) and labeled with phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated lineage antibodies, fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated Sca-1, and allophycocyanin (APC)-conjugated c-Kit, and LSK cells were sorted.

Transplantation assay

For noncompetitive transplantation, 2 × 106 whole BM cells from test mice were injected into lethally irradiated (11 Gy) BoyJ mice through the lateral tail vein. Then 16 to 24 weeks posttransplantation, recipients were used as donors for the subsequent transplantation cycle. For competitive transplantation, 2 × 106 BM cells from mice with each genotype were mixed with the same number of wild-type (WT) competitor BM cells and transplanted into lethally irradiated BoyJ recipients. For nonmyeloablative transplantation, 5 × 106 BM cells were infused into unconditioned recipients.

Analysis of HSC cell cycle and proliferation

A total of 5 × 106 BM cells were incubated in Iscove modified Dulbecco medium in the presence of 5 μg/mL Hoechst 33342 at 37°C for 45 minutes and 1 μg/mL pyronin Y for an additional 45 minutes. DNA and RNA contents within LSK and SLAM-LSK fractions were analyzed to determine the cell-cycle status.

Mice were treated through intraperitoneal injection of 1 mg 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU; Sigma-Aldrich) per 10 g body weight and 1 mg/mL BrdU was added to the drinking water for 30 hours. BrdU incorporation within gated LSK cells was evaluated using a BrdU staining kit (BD Biosciences).

Apoptosis analysis and γH2AX analysis

BM cells were stained with PE-labeled lineage antibodies, APC–c-Kit, PE-Cy7–Sca-1, or APC-Cy7–labeled lineage and CD48 antibodies, APC-c-Kit, PE-Cy7-Sca1, and PE-CD150. Apoptosis rates within LSK or SLAM-LSK were determined by staining with FITC–annexin V (BD Biosciences) and 4′,6′-diamino-2′-phenylindole (DAPI; Invitrogen).

γH2AX flow analysis were performed following the methods described previously.38 BM cells were stained with APC-Cy7–labeled lineage and CD48 antibodies, APC-c-Kit, PE-Cy7-Sca1, and PE-CD150 and fixed and permeabilized before they were stained with γH2AX antibody (Millipore).

Quantitative PCR

RNA was isolated from sorted LSK cells using the PicoPure Kit (Invitrogen), and cDNA was prepared using the SuperScript III First Strand Synthesis system (Invitrogen) and analyzed in triplicate with FastStart Universal SYBR Green Master (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). Real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed using the 7500 FAST real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Specificity of products was confirmed by melting curve analysis and assessing band size in 2.5% agarose gels. Data were analyzed with 7500 Fast System Sequence Detection software (version 1.3.1).

Statistical analysis

Where not otherwise stated, the Student t test was used to determine significance.

Results

Deficiency in Ku70 affects BM immunophenotypic HSC population at steady state

Ku70−/− mice were obtained through a Ku70 heterozygous cross. The yield of Ku70−/− mice was <5% at weaning age (our unpublished results), indicating a growth and development disadvantage. At steady state, no difference was observed in hematocrit or red cell counts in PB, whereas Ku70−/− mice showed decreased white blood cell counts due to the lack of T and B lymphocytes (supplemental Table 1, available on the Blood Web site) and the calculated absolute cell numbers of myeloid cells (Mac1+) were compatible with those from WT mice (supplemental Figure 1A). Ku70−/− mice also showed reduced BM cellularity, probably due to significantly reduced body size (supplemental Figure 1B).21,39

The effects of Ku70 on the HSC/progenitor pool at steady state were also examined. The frequencies of LSK and LT-HSC were not significantly different (Figure 1A-B), whereas the frequency of SLAM-LSK was decreased significantly in Ku70−/− mice (Figure 1C). Numerically, the total numbers of LSK, LT-HSC, and SLAM-LSK were significantly decreased in Ku70−/− mice (Figure 1).

Phenotypic characterization of HSC and progenitor compartment in Ku70−/−mice. BM cells from 3-month-old Ku70−/− mice and WT littermates were assayed by multiparameter fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) for proportion of HSC and progenitor populations. At least 6 mice per genotype were compared. Representative FACS pregated profiles of live, lineage-negative cells and frequencies of each indicated population are shown, and the absolute numbers of each population were calculated by multiplying the BM cell numbers with frequency. (A) Hematopoietic progenitors (lin−, Sca1+, c-Kit+ [LSK]), (B) long-term HSCs (LT-HSCs) (LSK, CD34−, Flk2−), and (C) signaling lymphocyte activating molecule (SLAM)-LSK. Significance was determined by a 2-tailed Student t test. Error bars indicate the standard deviation (SD). *P < .05.

Phenotypic characterization of HSC and progenitor compartment in Ku70−/−mice. BM cells from 3-month-old Ku70−/− mice and WT littermates were assayed by multiparameter fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) for proportion of HSC and progenitor populations. At least 6 mice per genotype were compared. Representative FACS pregated profiles of live, lineage-negative cells and frequencies of each indicated population are shown, and the absolute numbers of each population were calculated by multiplying the BM cell numbers with frequency. (A) Hematopoietic progenitors (lin−, Sca1+, c-Kit+ [LSK]), (B) long-term HSCs (LT-HSCs) (LSK, CD34−, Flk2−), and (C) signaling lymphocyte activating molecule (SLAM)-LSK. Significance was determined by a 2-tailed Student t test. Error bars indicate the standard deviation (SD). *P < .05.

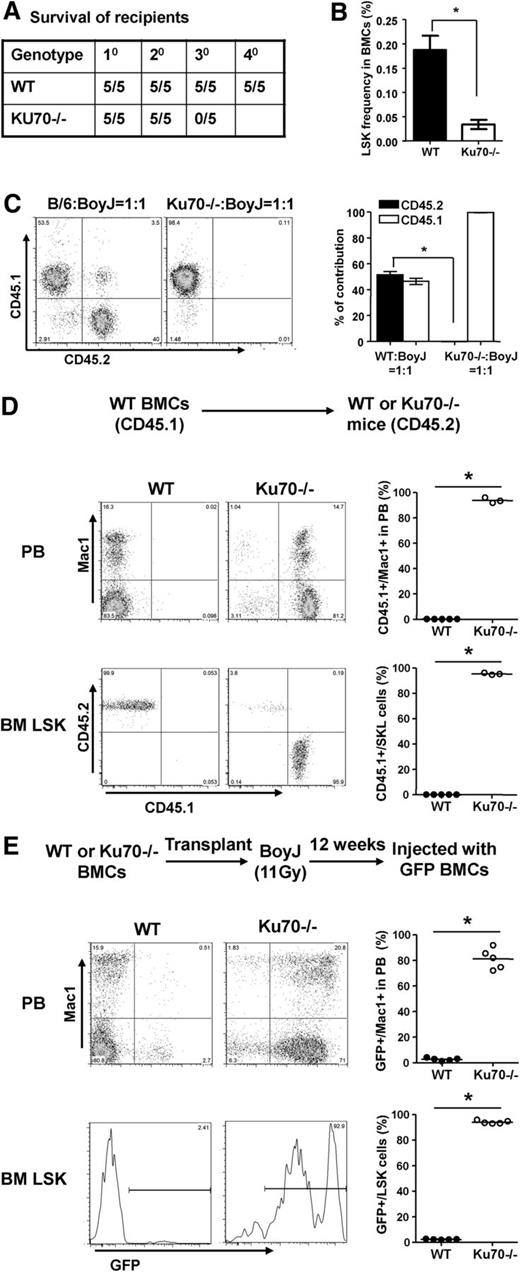

Ku70-deficient HSCs have repopulating defects

To assess the self-renewal activity of Ku70−/− HSCs in vivo, noncompetitive serial transplantation was performed. Following 2 rounds of transplantation, each after 16 weeks of reconstitution, Ku70−/− HSCs were not able to rescue the tertiary recipients, whereas WT HSCs were able to support tertiary and quaternary recipients under the same conditions (Figure 2A). Consistent with the loss of reconstitution, a significant reduction in the frequency of LSK cells was also detected in the BM of Ku70−/− secondary recipients (Figure 2B).

Functional assessment of HSCs from Ku70−/−mice. (A) Noncompetitive serial transplants were initiated by transplanting 2 × 106 whole BM pooled from 3-month-old WT (n = 3) or Ku70−/− (n = 2) donor mice (CD45.2) into irradiated recipients (CD45.1, n = 5 per group). Secondary and tertiary transplants were performed after 16 to 24 weeks of engraftment by pooling BM from 3 to 4 reconstituted recipients to transplant 2 × 106 whole BM into new groups of irradiated CD45.1 recipients. Survival of recipient mice was monitored. Shown is a representative result of 2 independent experiments. (B) Prior to transplant into tertiary recipients, BM from 5 secondary recipients of both genotypes was assayed by FACS for the frequency of LSK. Error bars indicated SD of the mean, and significance was determined by a 2-tailed Student t test. *P < .01. (C) BM from 3-month-old WT and Ku70−/− mice (CD45.2) was harvested and mixed with WT BM (CD45.1) at a 1:1 ratio and transplanted into lethally irradiated WT mice (CD45.1, n = 5 per group). Then 16 weeks after transplantation, donor chimerism in the PB was analyzed and quantitated. Similar results were obtained in 3 independent experiments. Error bars indicate the SD, and significance was determined by a 2-tailed Student t test. *P < .005. (D) Three-month-old recipient mice (CD45.2) were transplanted with WT (CD45.1) BM cells without any ablative conditioning. Donor-derived Mac1+ cells in the PB were analyzed 16 weeks after transplantation from 2 separate injections (WT, n = 5; Ku70−/−, n = 3). Then 16 to 24 weeks after transplantation, BM cells were isolated from recipient mice and chimerism of LSK population in each recipient mouse was analyzed. (E) A total of 5 × 106 BM cells from WT, Ku70−/− (CD45.2) donors were transplanted into lethally irradiated WT (CD45.1, n = 5 per group) recipients. Then 12 weeks later, the transplanted BM chimeras were challenged with 5 × 106 GFP-transgenic BM cells. The percentage of donor-derived GFP+ Mac1+ cells in each mouse was determined by FACS 16 weeks later. Then 16 to 24 weeks after transplantation, chimerism of LSK population in the recipient BM was analyzed. Shown is representative result of 2 independent experiments. For Student t tests relative to WT, *P < .001. BMC, bone marrow cells.

Functional assessment of HSCs from Ku70−/−mice. (A) Noncompetitive serial transplants were initiated by transplanting 2 × 106 whole BM pooled from 3-month-old WT (n = 3) or Ku70−/− (n = 2) donor mice (CD45.2) into irradiated recipients (CD45.1, n = 5 per group). Secondary and tertiary transplants were performed after 16 to 24 weeks of engraftment by pooling BM from 3 to 4 reconstituted recipients to transplant 2 × 106 whole BM into new groups of irradiated CD45.1 recipients. Survival of recipient mice was monitored. Shown is a representative result of 2 independent experiments. (B) Prior to transplant into tertiary recipients, BM from 5 secondary recipients of both genotypes was assayed by FACS for the frequency of LSK. Error bars indicated SD of the mean, and significance was determined by a 2-tailed Student t test. *P < .01. (C) BM from 3-month-old WT and Ku70−/− mice (CD45.2) was harvested and mixed with WT BM (CD45.1) at a 1:1 ratio and transplanted into lethally irradiated WT mice (CD45.1, n = 5 per group). Then 16 weeks after transplantation, donor chimerism in the PB was analyzed and quantitated. Similar results were obtained in 3 independent experiments. Error bars indicate the SD, and significance was determined by a 2-tailed Student t test. *P < .005. (D) Three-month-old recipient mice (CD45.2) were transplanted with WT (CD45.1) BM cells without any ablative conditioning. Donor-derived Mac1+ cells in the PB were analyzed 16 weeks after transplantation from 2 separate injections (WT, n = 5; Ku70−/−, n = 3). Then 16 to 24 weeks after transplantation, BM cells were isolated from recipient mice and chimerism of LSK population in each recipient mouse was analyzed. (E) A total of 5 × 106 BM cells from WT, Ku70−/− (CD45.2) donors were transplanted into lethally irradiated WT (CD45.1, n = 5 per group) recipients. Then 12 weeks later, the transplanted BM chimeras were challenged with 5 × 106 GFP-transgenic BM cells. The percentage of donor-derived GFP+ Mac1+ cells in each mouse was determined by FACS 16 weeks later. Then 16 to 24 weeks after transplantation, chimerism of LSK population in the recipient BM was analyzed. Shown is representative result of 2 independent experiments. For Student t tests relative to WT, *P < .001. BMC, bone marrow cells.

Competitive repopulation assay was also performed. When mixed with WT at 1:1 ratio, Ku70−/− BM showed a significant competitive repopulation disadvantage, resulting in no detectable contribution to PB leukocyte chimerism even at 8 weeks posttransplantation (Figure 2C). Ku70−/− LSKs were not detected in the recipient BM (data not shown). Together, these results demonstrate that Ku70−/− HSCs have a severely impaired capacity for self-renewal.

Lack of Ku70 impairs HSCs BM hematopoietic niche occupancy

BM hematopoietic niche occupancy is an important characteristic of HSCs, which generate long-term hematopoiesis.40,,,-44 To examine the BM hematopoietic niche occupancy ability of Ku70−/− HSCs, 5 × 106 congenic WT BM cells were transplanted into unconditioned WT or Ku70−/− mice. As expected, little if any measurable HSC engraftment occurred in WT recipients. In contrast, WT HSCs made a long-term multilineage contribution to hematopoiesis in Ku70−/− recipients. By 16 weeks after transplantation, more than 80% of LSK cells in the BM and 80% of Mac1+ cells in the PB were WT donor derived (Figure 2D). In addition, donor-derived lymphoid cells, both T and B cells, are present in the PB of Ku70−/− recipients (supplemental Figure 2), indicating that the BM microenvironment in Ku70−/− mice was capable of supporting normal HSC differentiation and lymphoid development.

To exclude the possible effects of the Ku70−/− BM microenvironment on HSCs, Ku70−/− or WT BM were transplanted into lethally irradiated WT recipients to generate BM chimeras. A total of 5 × 106 GFP transgenic BM were then transplanted into these BM chimeras without additional treatment. GFP BM underwent little engraftment (<2%) in WT recipients, whereas GFP BM established long-term engraftment in Ku70−/− recipients; 16 weeks after GFP BM transplantation, more than 90% of the BM LSK cells and 75% of the Mac1+ cells in the PB were GFP+ (Figure 2E). These results indicate that the functional BM niche occupancy defect of Ku70−/− HSCs is cell autonomous rather than mediated by the Ku70−/− BM microenvironment.

Ku70−/− HSCs are less quiescent

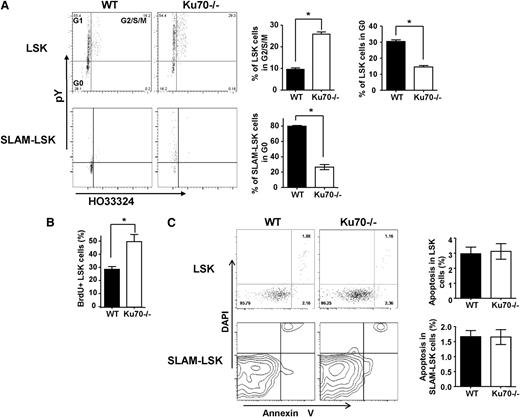

We next set out to determine whether the cell-cycle or quiescence status of HSCs was altered by the lack of Ku70. Using Hoechst 33324 (Ho) and pyronin Y staining, we identified that 26.4% ± 4.2% of LSK cells from Ku70−/− mice are in the G2/S/M phase compared with 11.5% ± 3.2% of LSK cells from WT mice (Figure 3A). Only 14.6% ± 3.8% of Ku70−/− LSK cells were in G0 phase, compared with 28.3% ± 6.2% of WT control LSK cells (Figure 3A). Furthermore, 26.4% ± 2.3% of Ku70−/− SLAM-LSK cells were in G0, compared with 79.6% ± 1.6% of WT cells (Figure 3A). A BrdU incorporation experiment was performed to determine the proliferation of HSCs in Ku70−/− mice. We found that 38.6% ± 4.8% of LSK cells from Ku70−/− mice are BrdU positive, whereas 28.4% ± 3.2% of LSK cells from WT mice are BrdU positive (Figure 3B). Ku70 BM was more sensitive to fluorouracil (5-FU) treatment in vivo compared with WT BM (supplemental Figure 3), and the increased sensitivity to 5-FU of Ku70−/− HSCs is likely due to the loss of HSC in the quiescent state, because cells deficient in Ku70 or the NHEJ pathway were not specifically sensitive to 5-FU.45 These results showed that loss of Ku70 in HSCs led to a loss of quiescence and active proliferation.

Proliferation and apoptosis of Ku70−/−HSCs/progenitors. (A) BM cells were isolated from 3-month-old Ku70−/− and WT mice and subjected to FACS analysis after treatment with Hoechst 33342 and Pyronin Y and staining with surface markers. Three separate experiments were performed with 3 to 5 mice per genotype compared. LSK and SLAM-LSK cells were analyzed by Ho33342 contents and pyronin Y intensity, and the proportion of cells in G2/S/M or G0/G1 phase was quantitated. Error bars indicate the SD, and significance was determined by a 2-tailed Student t test. *P < .05. (B) BrdU incorporation. WT (n = 5) and Ku70−/− (n = 3) mice were injected and fed with BrdU for 30 hours. BM cells were isolated and BrdU+ proportion within LSK fraction was analyzed. (C) BM cells from Ku70−/− and WT mice were isolated and subjected to FACS analysis after staining with surface markers along with annexin V and DAPI. The proportion of annexin V–positive (DAPI-negative) cells within the LSK and SLAM-LSK fraction is quantitated. Error bars indicate SD, and significance was determined by a 2-tailed Student t test.

Proliferation and apoptosis of Ku70−/−HSCs/progenitors. (A) BM cells were isolated from 3-month-old Ku70−/− and WT mice and subjected to FACS analysis after treatment with Hoechst 33342 and Pyronin Y and staining with surface markers. Three separate experiments were performed with 3 to 5 mice per genotype compared. LSK and SLAM-LSK cells were analyzed by Ho33342 contents and pyronin Y intensity, and the proportion of cells in G2/S/M or G0/G1 phase was quantitated. Error bars indicate the SD, and significance was determined by a 2-tailed Student t test. *P < .05. (B) BrdU incorporation. WT (n = 5) and Ku70−/− (n = 3) mice were injected and fed with BrdU for 30 hours. BM cells were isolated and BrdU+ proportion within LSK fraction was analyzed. (C) BM cells from Ku70−/− and WT mice were isolated and subjected to FACS analysis after staining with surface markers along with annexin V and DAPI. The proportion of annexin V–positive (DAPI-negative) cells within the LSK and SLAM-LSK fraction is quantitated. Error bars indicate SD, and significance was determined by a 2-tailed Student t test.

The effect of Ku70 on HSC apoptosis at steady state was also examined. Low levels of apoptosis were observed in the LSK and SLAM-LSK fractions from both WT and Ku70−/− mice (Figure 3C), indicating that Ku70−/− HSCs/progenitors are not prone to spontaneous apoptosis at steady state.

We also examined the growth and apoptosis of Ku70−/− HSCs/progenitors in vitro. Ku70−/− LSK cells display similar expansion rates to those of WT cells (supplemental Figure 4), and Ku70−/− LSK cells showed a similar spontaneous apoptosis rate to that of WT cells (supplemental Figure 4).

Together, these results indicate that apoptosis is not the primary cause of the defect in Ku70−/− HSCs. Instead, a loss of quiescence contributes to the loss of HSC function in Ku70−/− mice.

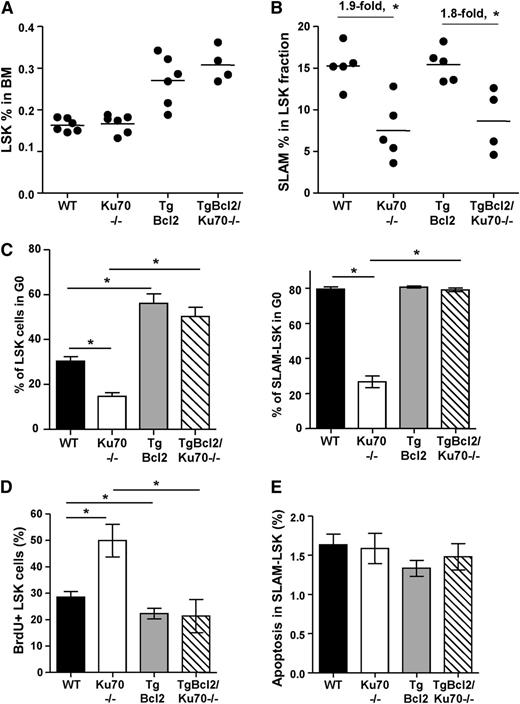

Overexpression of Bcl2 restores HSC quiescence in Ku70-deficient mice

Bcl2 inhibits cell proliferation, and the BM Lin− fraction from TgBcl2 mice showed less active proliferation.32 We hypothesized that Bcl2 overexpression will inhibit HSC proliferation, enhance HSC quiescence, and restore quiescence in Ku70-deficient HSCs. To test this hypothesis, TgBcl2/Ku70−/− mice were generated. TgBcl2/Ku70−/− mice showed slightly higher BM cellularity and white blood cell counts in PB compared with Ku70−/− mice (supplemental Figure 5A-B) and a similar SCID phenotype (with no mature T and B cells) (supplemental Figure 5C), indicating that overexpression of Bcl2 does not rescue V(D)J recombination defect of Ku70−/− mice.

The HSC/progenitor pools were analyzed. LSK frequency in the BM of TgBcl2/Ku70−/− mice increased by 1.8-fold, compared with Ku70−/− mice (Figure 4A), similar with the fold increase in the BM of TgBcl2 mice compared with WT mice (Figure 4A). Interestingly, within the LSK fraction, frequencies of SLAM-LSK cells were not affected by Bcl2 overexpression in WT or Ku70−/− mice (Figure 4B). The reduction of LSK and SLAM-LSK numbers in Ku70−/− mice was not significantly different on WT and TgBcl2 backgrounds (supplemental Figure 5D). Similarly, Bcl2 overexpression in Tpo−/− mice or c-KitW41 mice did not restore the primitive HSC pools.46,47 These results suggest that Bcl2 overexpression did not restore the LT-HSC pool, although it did increase the LSK fraction.

Overexpression of Bcl2 partially increased HSC/progenitor pools and restored HSC quiescence in Ku70−/−mice. (A) BM cells from age-matched WT (n = 6), Ku70−/− (n = 6), TgBcl2 (n = 5), and TgBcl2/Ku70−/− (n = 4) mice were assayed by multiparameter FACS for proportion of HSC/progenitor populations. Frequency of LSK cells was analyzed. (B) Within the LSK fraction, frequency of SLAM-LSK cells was quantitated. (C) BM cells were isolated from age-matched mice with different genotypes and staining with surface markers after treatment with Hoechst 33342 and pyronin Y. LSK and SLAM-LSK cells were analyzed by HO33342 contents and pyronin Y intensity, and proportion of cells in G0 phase was quantitated. Three separate experiments were performed with 3 to 5 mice per genotype compared. (D) BrdU incorporation. WT (n = 5), Ku70−/− (n = 3), TgBcl2 (n = 5), and TgBcl2/Ku70−/− (n = 3) mice were injected and fed with BrdU for 30 hours. BM cells were isolated and BrdU+ proportion within LSK fraction was analyzed. Error bars indicate the SD, and significance was determined by a 2-tailed Student t test. *P < .05. (E) BM cells from WT, Ku70−/−, TgBcl2, and TgBcl2/Ku70−/− mice were isolated and subjected to FACS analysis after staining with surface markers along with annexin V and DAPI. The proportion of annexin V–positive (DAPI-negative) cells within the SLAM-LSK fraction is quantitated.

Overexpression of Bcl2 partially increased HSC/progenitor pools and restored HSC quiescence in Ku70−/−mice. (A) BM cells from age-matched WT (n = 6), Ku70−/− (n = 6), TgBcl2 (n = 5), and TgBcl2/Ku70−/− (n = 4) mice were assayed by multiparameter FACS for proportion of HSC/progenitor populations. Frequency of LSK cells was analyzed. (B) Within the LSK fraction, frequency of SLAM-LSK cells was quantitated. (C) BM cells were isolated from age-matched mice with different genotypes and staining with surface markers after treatment with Hoechst 33342 and pyronin Y. LSK and SLAM-LSK cells were analyzed by HO33342 contents and pyronin Y intensity, and proportion of cells in G0 phase was quantitated. Three separate experiments were performed with 3 to 5 mice per genotype compared. (D) BrdU incorporation. WT (n = 5), Ku70−/− (n = 3), TgBcl2 (n = 5), and TgBcl2/Ku70−/− (n = 3) mice were injected and fed with BrdU for 30 hours. BM cells were isolated and BrdU+ proportion within LSK fraction was analyzed. Error bars indicate the SD, and significance was determined by a 2-tailed Student t test. *P < .05. (E) BM cells from WT, Ku70−/−, TgBcl2, and TgBcl2/Ku70−/− mice were isolated and subjected to FACS analysis after staining with surface markers along with annexin V and DAPI. The proportion of annexin V–positive (DAPI-negative) cells within the SLAM-LSK fraction is quantitated.

We next analyzed the cell-cycle status/quiescence states and apoptosis of HSCs in mice overexpressing Bcl2. Interestingly, the proportion of LSK cells at G0 was significantly increased in TgBcl2 compared with WT mice (60.4% ± 3.6% vs 28.3% ± 6.2%) and, more strikingly, the proportion of LSK in G0 was also significantly improved in TgBcl2/Ku70−/− mice compared with Ku70−/− mice (59.7% ± 4.6% vs 14.6% ± 3.8%) (Figure 4C). Within the SLAM-LSK fraction, Bcl2 overexpression restored the G0 proportion in Ku70−/− mice (79.1% ± 1.1% vs 26.4% ± 2.3%), though it did not further increase the G0 proportion in WT mice (80.7% ± 0.6% vs 79.6% ± 1.6%) (Figure 4C). BrdU incorporation experiments showed that TgBcl2 mice displayed less BrdU incorporation in BM LSK cells compared with WT mice (22.6% ± 4.4% vs 28.4% ± 3.2%), whereas TgBcl2/Ku70−/− mice showed fewer cycling LSK cells compared with Ku70−/− mice (23.2% ± 3.2% vs 38.6% ± 4.8%) (Figure 4D). Additionally, spontaneous apoptosis within SLAM-LSK was not significantly altered by Bcl2 overexpression (Figure 4E). These results indicate that overexpression of Bcl2 enhances HSC/progenitor quiescence and restores quiescence in Ku70−/− HSCs.

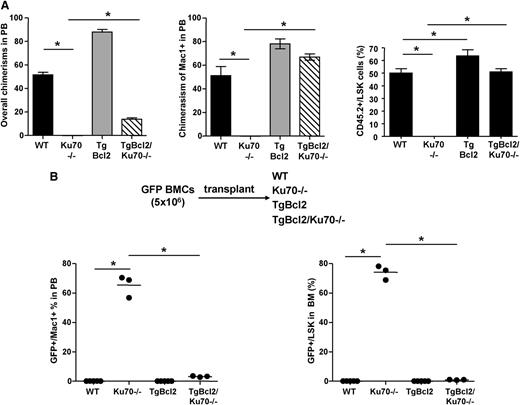

Overexpression of Bcl2 rescues the HSC defects in Ku70−/− mice

To determine whether overexpression of Bcl2 would rescue the repopulation defect of Ku70−/− HSCs, competitive repopulation assays were performed. When mixed with WT competitor BM at a 1:1 ratio, TgBcl2 BM cells contributed to ∼90% of the overall chimerism and ∼80% of Mac1+ chimerism in the PB. TgBcl2/Ku70−/− BM cells contributed to ∼70% of the Mac1+ chimerism in the PB. TgBcl2 BM made a significantly higher contribution to BM LSK compared with WT BM (63.46% ± 6.21% vs 50.13% ± 4.33%), and the contribution from TgBcl2/Ku70−/− BM increased dramatically compared with Ku70−/− BM (51% ± 2.86% vs 0%) (Figure 5A). These results indicate that overexpression of Bcl2 enhances HSC repopulation activity and can rescue the competitive repopulation defect of Ku70−/− HSCs. The even greater advantage of TgBcl2 in the PB than in the BM LSK suggests that these cells are actively contributing to hematopoiesis and may also benefit from Bcl2 by prolonging the survival of mature blood cells.

Overexpression of Bcl2 rescued HSC defects of Ku70−/−mice. (A) Competitive repopulation assay. BM from 3-month-old WT, Ku70−/− and TgBcl2, TgBcl2/Ku70−/− mice (CD45.2) was isolated and mixed with WT BM (CD45.1) at a 1:1 ratio and transplanted into lethally irradiated WT mice (CD45.1, n = 5 per group). Then 16 weeks posttransplantation, donor chimerisms in the PB and BM LSK cells were analyzed. Similar results were obtained in 2 independent experiments. (B) BM from TgGFP mice was transplanted into 3-month-old mice with different genotypes without any preconditioning. Then 16 weeks posttransplantation, donor chimerisms (GFP+) in the PB and BM LSK cells were quantitated. The number of recipients were WT (n = 5), Ku70−/− (n = 3), TgBcl2 (n = 5), and TgBcl2/Ku70−/− (n = 3). Error bars indicate the SD, and significance was determined by a 2-tailed Student t test. *P < .005.

Overexpression of Bcl2 rescued HSC defects of Ku70−/−mice. (A) Competitive repopulation assay. BM from 3-month-old WT, Ku70−/− and TgBcl2, TgBcl2/Ku70−/− mice (CD45.2) was isolated and mixed with WT BM (CD45.1) at a 1:1 ratio and transplanted into lethally irradiated WT mice (CD45.1, n = 5 per group). Then 16 weeks posttransplantation, donor chimerisms in the PB and BM LSK cells were analyzed. Similar results were obtained in 2 independent experiments. (B) BM from TgGFP mice was transplanted into 3-month-old mice with different genotypes without any preconditioning. Then 16 weeks posttransplantation, donor chimerisms (GFP+) in the PB and BM LSK cells were quantitated. The number of recipients were WT (n = 5), Ku70−/− (n = 3), TgBcl2 (n = 5), and TgBcl2/Ku70−/− (n = 3). Error bars indicate the SD, and significance was determined by a 2-tailed Student t test. *P < .005.

To determine whether overexpression of Bcl2 would rescue the BM hematopoietic niche occupancy defect observed in Ku70−/− HSCs (Figure 2), 5 × 106 BM cells from TgGFP mice were transplanted into each genotype without any conditioning. Similar to the engraftment noted in WT mice, little of any donor engraftment can be detected in TgBcl2 recipient mice. In sharp contrast, whereas donor GFP BM could make significant long-term engraftment in Ku70−/− mice and contribute to multilineage hematopoiesis, the engraftment of donor WT BM in TgBcl2/Ku70−/− recipient mice was significantly reduced. By 16 weeks after transplantation, only about 3% of the Mac1+ cells in the PB and <2% of BM LSK cells in the TgBcl2/Ku70−/− recipients are GFP+ (Figure 5B). This result indicates that Bcl2 overexpression rescues the BM hematopoietic niche occupancy defect of Ku70−/− HSCs.

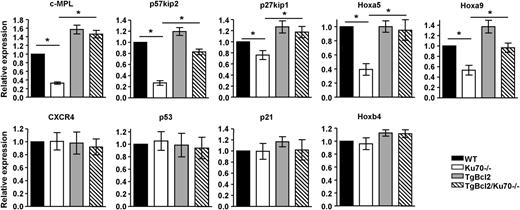

Our results demonstrate that Bcl2 overexpression rescued the HSC maintenance defects in Ku70−/− mice mainly by restoration of HSC quiescence, in addition to the enhanced survival. To investigate the mechanisms by which Ku70 and Bcl2 regulate HSC quiescence, expression of several HSC function- or quiescence-related genes were examined in sorted BM LSK cells by real-time reverse-transcription PCR. We found that in the Ku70−/− LSK cells, expression of c-MPL, p57kip2 was downregulated by about 3-fold and that expression of p27, Hoxa5, Hoxa9 was also downregulated (Figure 6). Consistent with the biological activity noted, overexpression of Bcl2 restores the expression of c-MPL, p57 to the level of WT LSK cells and also that of p27, Hoxa5, Hoxa9 (Figure 6). The expression of p53, p21, Hoxb4, CXCR4 was not significantly altered among each genotype, suggesting that changes in these functions are not critical to the observed defect of Bcl2 effect. Our results suggest that multiple pathways are involved in the loss of HSC quiescence in Ku70−/− mice. Bcl2 rescue of the Ku70−/− HSC quiescence defect is enough to compensate for many of these pathway changes.

Expression of quiescence-associated genes in Ku70−/−HSCs. BM was isolated from 3 independent groups of WT, Ku70−/−, and TgBcl2, TgBcl2/Ku70−/− mice, and LSK cells were sorted before messenger RNA isolation. The relative messenger RNA expression levels of c-Mpl, p57, p27, p53, p21, Hoxa5, Hoxa9, Hoxb4, and CXCR4 were evaluated by quantitative real-time reverse-transcription PCR with endogenous control GAPDH in triplicate. Means from 3 or 4 independent experiments are shown. Error bars indicate SD, and significance was determined by a 2-tailed Student t test. *P < .05.

Expression of quiescence-associated genes in Ku70−/−HSCs. BM was isolated from 3 independent groups of WT, Ku70−/−, and TgBcl2, TgBcl2/Ku70−/− mice, and LSK cells were sorted before messenger RNA isolation. The relative messenger RNA expression levels of c-Mpl, p57, p27, p53, p21, Hoxa5, Hoxa9, Hoxb4, and CXCR4 were evaluated by quantitative real-time reverse-transcription PCR with endogenous control GAPDH in triplicate. Means from 3 or 4 independent experiments are shown. Error bars indicate SD, and significance was determined by a 2-tailed Student t test. *P < .05.

Overexpression of Bcl2 does not restore the DNA-repair defect of Ku70−/− HSCs

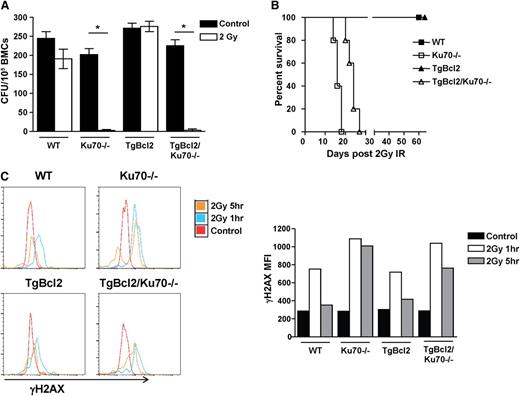

Our results have demonstrated that overexpression of Bcl2 restored HSC maintenance in Ku70−/− mice and that Ku70 is essential for DNA repair. However, it is important to examine whether overexpression of Bcl2 would restore DNA repair capacity in Ku70−/− HSCs. In response to 2 Gy radiation, Ku70−/− BM cells failed to grow and form colonies in a colony-forming unit assay and Bcl2 overexpression increased the resistance to radiation in TgBcl2 BM, but not TgBcl2/Ku70−/− BM (Figure 7A). Radiosensitivity of HSCs was also examined in primary recipients reconstituted with different-genotype BM. Although WT and TgBcl2 BM recipient mice survived 2 Gy radiation well beyond 2 months, all Ku70−/− BM and TgBcl2/Ku70−/− BM recipient mice died within 1 month (Figure 7B).

Overexpression of Bcl2 did not restore DNA repair capacity in Ku70−/−HSCs. (A) Three-month-old WT, Ku70−/−, TgBcl2, and TgBcl2/Ku70−/− mice were irradiated with 2 Gy. BM cells were isolated and plated in methylcellulose in the presence of interleukin-3, interleukin-6, and stem cell factor. Colony-forming units were counted 14 days later. Shown is the representative result of 2 independent experiments. Error bars indicate SD, and significance was determined by a 2-tailed Student t test. *P < .001. (B) BM cells from 3-month-old WT, Ku70−/−, TgBcl2 and TgBcl2/Ku70−/− mice were transplanted into lethally irradiated BoyJ recipients. Then 12 weeks posttransplantation, the recipients were irradiated with 2 Gy radiation and survival of the recipients was monitored (n = 5 per group). (C) Three-month-old WT, Ku70−/−, TgBcl2, and TgBcl2/Ku70−/− mice were irradiated with 2 Gy and at each time point BM cells were isolated and analyzed by FACS to assess the levels of γH2AX in the SLAM-LSK fraction. Shown is the representative result of 2 independent experiments. CFU, colony-forming units; IR, irradiation.

Overexpression of Bcl2 did not restore DNA repair capacity in Ku70−/−HSCs. (A) Three-month-old WT, Ku70−/−, TgBcl2, and TgBcl2/Ku70−/− mice were irradiated with 2 Gy. BM cells were isolated and plated in methylcellulose in the presence of interleukin-3, interleukin-6, and stem cell factor. Colony-forming units were counted 14 days later. Shown is the representative result of 2 independent experiments. Error bars indicate SD, and significance was determined by a 2-tailed Student t test. *P < .001. (B) BM cells from 3-month-old WT, Ku70−/−, TgBcl2 and TgBcl2/Ku70−/− mice were transplanted into lethally irradiated BoyJ recipients. Then 12 weeks posttransplantation, the recipients were irradiated with 2 Gy radiation and survival of the recipients was monitored (n = 5 per group). (C) Three-month-old WT, Ku70−/−, TgBcl2, and TgBcl2/Ku70−/− mice were irradiated with 2 Gy and at each time point BM cells were isolated and analyzed by FACS to assess the levels of γH2AX in the SLAM-LSK fraction. Shown is the representative result of 2 independent experiments. CFU, colony-forming units; IR, irradiation.

Next, we examined γH2AX levels in the SLAM-LSK fraction of mice after 2 Gy radiation. At steady state, γH2AX levels in HSCs with 4 genotypes were similar. In response to 2 Gy radiation, γH2AX levels increased in WT HSCs at 1 hour and resolved by 5 hours, whereas higher levels of γH2AX were observed in Ku70−/− HSCs at 1 hour and persisted at 5 hours. Bcl2 overexpression did not impact the γH2AX levels in TgBcl2 or TgBcl2/Ku70−/− HSCs (Figure 7C). In addition, HSCs diminished in the BM of Ku70−/− mice 24 hours after 2Gy radiation (supplemental Figure 6). These results indicated that Ku70−/− HSCs are hypersensitive to radiation and that overexpression of Bcl2 did not restore DNA repair capacity and protect Ku70−/− HSCs from radiation.

Discussion

Our studies demonstrate that Ku70 is essential for HSC maintenance. Lack of Ku70 results in loss of HSC quiescence and HSC maintenance, including self-renewal, competitive repopulation, and BM hematopoietic niche occupancy activities. Furthermore, overexpression of Bcl2 in HSCs promotes quiescence, restores quiescence in Ku70−/− HSCs, and rescues the HSC maintenance defects in Ku70−/− mice.

HSC apoptosis and proliferation in Ku70−/− mice

Apoptosis, proliferation, and interaction with BM niche are important factors for HSC maintenance. Ku70−/− HSCs/progenitors display comparable apoptosis rates with WT control at steady state (Figure 3) and after in vitro culture (our unpublished results), indicating that Ku70−/− HSCs are not prone to spontaneous apoptosis. HSCs deficient in caspase-3 are resistant to apoptosis but defective in maintenance, suggesting that apoptosis is not the primary cause of HSC defects.48 Although we cannot definitely rule out the possible apoptosis differences in vivo, we conclude that HSC defects of Ku70−/− mice are not primarily due to apoptosis.

Instead, we found that Ku70−/− HSC/progenitors lose quiescence (Figure 3) and Lig4Y288C LSKs also showed increased BrdU incorporation.22 These results together suggested that deficiency of NHEJ in HSCs leads to increased proliferation. However, mouse embryonic fibroblasts deficient in Ku70 or Lig4 display decreased proliferation.21,22 It is likely that the HSC response to proliferative signals in the absence of DNA repair may be regulated by both hematopoietic and quiescence signals.

Although some cell-cycle regulators have been shown to be directly involved in G0 maintenance, the cooperation of several cell-cycle regulators may also be required for quiescence regulation.49,-51 We observed decreased expression of p27 and p57, but not p53 and p21, in Ku70−/− HSCs/progenitors (Figure 6). Several cell-cell interaction signaling pathways have also been implicated in the maintenance of HSC quiescence.47,52,53 Here, the expression of c-Mpl and its target gene p57 was downregulated in Ku70−/− HSCs, suggesting that the c-Mpl signaling pathway may mediate the quiescence regulation by Ku70 in HSCs. However, it is not clear whether decreased c-Mpl signaling is a direct target of Ku70 loss or a concurrent phenotype of loss of HSC quiescence. More likely, Ku70 or NHEJ regulates quiescence and these mediators act downstream. Tpo can enhance DNA repair in HSCs by stimulating DNA PKcs in response to radiation,54 and in Ku70−/− HSC/progenitors, the decreased expression of Tpo receptor (c-Mpl), the absence of Ku70, and the reduced DNA PKcs activity may synergistically lead to hypersensitivity to radiation (Figure 7; supplemental Figure 6).

The role of Bcl2 in HSC maintenance

Previous results indicate that Bcl2 enhances HSC function by protecting HSCs against apoptosis.33,55 However, human CD34+ cord blood cells overexpressing Bcl2 displayed better transplantability compared with cells overexpressing a mutant p53, which is also defective in inducing apoptosis.56 In addition, when the impact of p53 loss and Bcl2 overexpression on a NUP98-HOXD13 (NHD13)-induced myelodysplastic syndrome mouse model was examined, overexpression of Bcl2 delayed AML transition, whereas deletion of p53 accelerated AML transition.57,58 These findings suggest Bcl2 may have more activity in HSCs beyond simply antiapoptosis. Our results showed that overexpression of Bcl2 results in increased HSC quiescence and decreased proliferation (Figure 4). Strikingly, overexpression of Bcl2 rescues the Ku70−/− HSC maintenance defects, including competitive repopulation and BM hematopoietic niche occupancy (Figure 5). Ku70−/− HSCs are not prone to spontaneous apoptosis but lose quiescence at steady state (Figure 3). Overexpression of Bcl2 restores the quiescence in Ku70−/− HSCs, and in so doing, Bcl2 plays an essential role in the rescue of Ku70−/− HSC maintenance defects.

DNA-repair pathways and HSC maintenance

DNA-repair activity in HSCs has not been well studied. Although endogenous DNA damage may exist in the HSC compartment in DNA-repair–deficient mice, whether this damage directly impairs HSC function is not clear. In Ku70−/− HSCs, the endogenous levels of DNA damage, determined by γH2Ax, was not significantly different from WT cells (Figure 7C). Our results also showed that overexpression of Bcl2 in Ku70−/− HSCs can rescue the HSC defects in Ku70−/− mice (Figure 5), whereas it did not restore DNA-repair capacity in Ku70−/− HSCs (Figure 7; supplemental Figure 5C). In human tumor cell lines, overexpression of Bcl2 negatively regulates DNA-repair pathways, including NHEJ.59 These results suggest that overexpression of Bcl2 can override the defects caused by DNA-repair deficiency in restoring HSC function. It is tempting to speculate that the endogenous DNA damage in Ku70−/− cells may not impair HSC function directly but rather impairs HSCs indirectly by reducing quiescence. This is reinforced by the finding that HSC quiescence is restored by overexpression of Bcl2, restoring HSC function without regaining NHEJ DNA-repair capacity. Although we further hypothesize that HSCs, in the absence of NHEJ, enter the cell cycle to repair DSBs by homologous recombination as at least one explanation of loss of quiescence, more studies are required to investigate the mechanisms by which loss of the NHEJ pathway results in loss of HSC quiescence.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Cytometry and Imaging Microscopy Core Facility of the Case Comprehensive Cancer Center (P30 CA43703) and by National Institutes of Health (National Cancer Institute) grant R01CA063193.

Authorship

Contribution: Y.Q. designed and performed the experiments and prepared the manuscript; Z.W. designed and performed the experiments; K.D.B. designed the experiments and interpreted the results; and S.L.G. designed the experiments, interpreted the results, and prepared the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

The current affiliation for Z.W. and K.D.B. is Department of Pediatrics, Aflac Cancer and Blood Disorders Center, Emory University School of Medicine.

Correspondence: Stanton L. Gerson, Case Comprehensive Cancer Center, National Center for Regenerative Medicine, Seidman Cancer Center, University Hospitals Case Medical Center and Case Western Reserve University, 11100 Euclid Ave, Wearn Room 151, Cleveland, OH 44106-5065; e-mail: slg5@case.edu.

![Figure 1. Phenotypic characterization of HSC and progenitor compartment in Ku70−/− mice. BM cells from 3-month-old Ku70−/− mice and WT littermates were assayed by multiparameter fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) for proportion of HSC and progenitor populations. At least 6 mice per genotype were compared. Representative FACS pregated profiles of live, lineage-negative cells and frequencies of each indicated population are shown, and the absolute numbers of each population were calculated by multiplying the BM cell numbers with frequency. (A) Hematopoietic progenitors (lin−, Sca1+, c-Kit+ [LSK]), (B) long-term HSCs (LT-HSCs) (LSK, CD34−, Flk2−), and (C) signaling lymphocyte activating molecule (SLAM)-LSK. Significance was determined by a 2-tailed Student t test. Error bars indicate the standard deviation (SD). *P < .05.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/123/7/10.1182_blood-2013-08-521716/2/m_1002f1.jpeg?Expires=1769130021&Signature=li9GHa77nDaekuVyUj-Vx0XVjAsI~m8zLUaN~6PagcMJ6NkuEeoMskCSshYrwNoF3EOHsTwCDQaknK9XV4ZbK0kP~bMZCAxwWEGN1ePwtDfkQ5M1SQNtFgiqxY15go22sSw3vkQTwltEOfSq~j72u6h0suU91VIlxhJjUSJBRaGLwrk-RXc8d7c9l65xWpxIdaOISN0UB8HdmA5VxvvMG~D5mn0-fiYvV6HzNLAlgBttgv-elbyIEy5CKuCGbp7fr5apfpGLH2LFdXnv0Et~f2unMnd8ZNf3wz0biv9fqIAvPD96OEq5c7vcFqoZ03q~XrIt~0~maDot7DZcx-C-fg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal