Key Points

Coagulation fVIII binds to a protein complex, including fibrin, on stimulated platelets rather than to membrane PS.

Anti-fVIII antibodies inhibit function on platelets differently than on phospholipid vesicles used in clinical assays.

Abstract

Thrombin-stimulated platelets expose very little phosphatidylserine (PS) but express binding sites for factor VIII (fVIII), casting doubt on the role of exposed PS as the determinant of binding sites. We previously reported that fVIII binding sites are increased three- to sixfold when soluble fibrin (SF) binds the αIIbβ3 integrin. This study focuses on the hypothesis that platelet-bound SF is the major source of fVIII binding sites. Less than 10% of fVIII was displaced from thrombin-stimulated platelets by lactadherin, a PS-binding protein, and an fVIII mutant defective in PS-dependent binding retained platelet affinity. Therefore, PS is not the determinant of most binding sites. FVIII bound immobilized SF and paralleled platelet binding in affinity, dependence on separation from von Willebrand factor, and mediation by the C2 domain. SF also enhanced activity of fVIII in the factor Xase complex by two- to fourfold. Monoclonal antibody (mAb) ESH8, against the fVIII C2 domain, inhibited binding of fVIII to SF and platelets but not to PS-containing vesicles. Similarly, mAb ESH4 against the C2 domain, inhibited >90% of platelet-dependent fVIII activity vs 35% of vesicle-supported activity. These results imply that platelet-bound SF is a component of functional fVIII binding sites.

Introduction

Factor VIII (fVIII) binds to platelet membranes where it serves as a cofactor for the enzyme, factor IXa, in the intrinsic factor Xase complex,1,2 converting the zymogen factor X to factor Xa.3,4 The importance of the factor Xase complex is illustrated by the disease hemophilia, in which deficiency of fVIII (hemophilia A) or factor IX (hemophilia B) leads to life-threatening bleeding. In spite of the central importance of the platelet membrane, the platelet fVIII binding sites have been only partially characterized.

fVIII circulates in plasma in a noncovalent complex with von Willebrand factor (VWF). Binding to VWF is mediated by the same motifs that bind platelet and phospholipid membranes.5,6 After dissociation from VWF, fVIII binds specifically to membranes containing phosphatidylserine (PS), which is exposed on the platelet membrane in response to stimulation by several agonists.1,6 The residual uncertainty about the identity of platelet binding sites relates to the quantity of PS exposed following stimulation by physiologic agonists and the availability of specific reagents to block the exposed PS. Thrombin stimulates platelets to expose limited PS, resulting in an outer membrane composition of 1% to 4% PS.7,8 This amount of PS may remain below the threshold to support the observed expression of 200 to 1600 binding sites per platelet.9,10 In contrast, the combination of thrombin and collagen, or higher concentrations of the calcium ionophore, A23187, lead to complete PS exposure with membrane composition estimated at 12% to 15% PS.7,8 Under these conditions, PS is thought to be a critical component of most of the >10 000 fVIII binding sites exposed per platelet.11,12 It has been conceptually attractive to attribute most fVIII activity to platelets with maximal PS exposure. However, in vivo studies have not identified platelets with high levels of PS exposure at sites of hemostasis or thrombosis.13 Thus, determining the characteristics of the binding sites on thrombin-stimulated platelets appears essential to understanding the function of fVIII.

fVIII has a domain structure of A1-a1-A2-a2-B-a3-A3-C1-C2, where a1, a2, and a3 are spacer regions.14 The C1 and C2 domains mediate membrane binding.15-19 The fVIII C domains share similar sequence and structure with the C domains of factor V20-22 and lactadherin,23 a milk fat globule membrane protein. Like fVIII, both factor V and lactadherin bind to PS-containing membranes.24,25 The membrane-binding role of the protruding hydrophobic amino acids of the fVIII,18 factor V,26,27 and lactadherin28 C2 domains has been confirmed by site-directed mutagenesis. An fVIII mutant, fVIII-4Ala, with hydrophobic spike amino acids changed (M2199A/F2200A, L2251A/L2252A) has less than 1% residual binding to and activity on synthetic, PS-containing membranes.18 This fVIII mutant has been used in the present study to test the hypothesis that platelets have binding sites not determined by membrane phospholipid.

We previously reported that binding of soluble fibrin (SF) to the αIIbβ3 integrin on thrombin-stimulated platelets increases the number of fVIII binding sites by three- to eightfold.10 However, fVIII did not bind to fibrin adsorbed to polystyrene beads, leading us to conclude that the platelet binding sites were not on platelet-bound fibrin. In the present study, we re-evaluated the possibility that fVIII(a) may bind directly to fibrin and that platelet-bound fibrin may be a component of the platelet binding sites for fVIII.

Hemophilia A is treated by infusing purified plasma fVIII into deficient patients. However, such treatment can result in the production of antibodies against fVIII that impair function.29 Several epitopes recognized by inhibitory antibodies are within the C2 domain and many neutralizing antibodies interfere with binding to phospholipid membranes and VWF. Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) directed against the C2 domain mimic clinical inhibitory antibodies.30 ESH4 and ESH8 are two prototype anti-C2 antibodies with nonoverlapping epitopes.31 ESH4 partially blocks binding to PS-containing membranes and binding to VWF.30,32 ESH8 does not inhibit fVIII activity supported by phospholipid vesicles (PLVs),32,33 but slows the dissociation of activated fVIII from VWF.33 In this study, we have evaluated the effect of ESH4 and ESH8 on fVIII binding to fibrin and platelets, and the extent to which the inhibitory effect on platelet-based fVIII activity differs from PLV-based activity.

Materials and methods

See supplemental Materials, available on the Blood Web site.

Proteins

Lipid-free bovine lactadherin was purified as described.25 fVIII-4Ala was produced as described18 with modifications as noted in supplemental Materials. The fVIII C2 (fVIII-C2) domain was produced, purified, and stored as described.19 fVIII was labeled with fluorescein maleimide as described.11 The ratio of fluorescein/fVIII ranged from 0.6/1 to 1.2/1 for studies in this report. GMA8021 was labeled with fluorescein isothiocyanate using a standard protocol.

fVIII binding to platelets

Platelets from human volunteers, with blood drawn under an Institutional Review Board-approved protocol, were purified as described10 and diluted in Tyrode’s buffer (138 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 3.3 mM NaH2PO4, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.1% dextrose, 0.2% bovine serum albumin [BSA], and 15 mM N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid, pH 7.4). Binding of fluorescein-labeled fVIII was measured by flow cytometry as previously described10 using a Becton Dickinson LSRFortessa flow cytometer.

fVIII binding to fibrin

Polyclonal anti-fibrinogen and mAb 59D8 were covalently coupled to batches of cyanogen bromide-activated Superose beads with an antibody/Superose ratio of 1.25 mg/mL as described.34 Fibrinogen (10 µg/mL) was incubated with the Superose beads for 20 minutes at 22°C with 1 u/mL thrombin. Hirudin (3 u/mL) was added and excess fibrin was removed by sedimenting the Superose beads 500 g for 30 seconds into 50 mM Tris pH 7.85, 150 mM NaCl, 0.01% Tween 80, and 0.1% BSA in a 2:1 ratio with OptiPrep. Fibrin-Superose beads were resuspended in 50 mM Tris pH 7.85, 150 mM NaCl, 0.01% Tween 80, and 0.1% BSA, and incubated with fVIII-fluor and competitors or inhibitors as indicated. Sedimentation was prevented during incubation by swirling approximately once per minute. In some experiments, fVIII-fluor was mixed with mAbs ESH4 or ESH8, VWF, or fVIII-C2 prior to mixing with fibrin-Superose beads, as indicated. Bound fVIII-fluor was evaluated by flow cytometry on an LSRFortessa flow cytometer. Data were analyzed as the geometric mean fluorescence of the dominant population (typically >90% of events) and corrected for background fluorescence attributable to beads and fVIII-fluor in the absence of fibrin(ogen).

fVIII activity

Activity in the factor Xase complex was measured with 2-step amidolytic substrate assays.16 PLVs were prepared by high-pressure extrusion through two stacked polycarbonate membranes with laser-etched pores as described.35 Added fibrinogen was activated with thrombin concurrently with the fVIII. One and two-stage fVIII activity was measured in an activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) assay (aPTT-SA reagent; Helena Labs) and in a 2-stage chromogenic assay (DiaPharma). aPTT assays were performed, according to package instructions, with the BBL fibrometer. The chromogenic assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions on a VersaMax microplate reader in kinetic mode.

Activated platelet time clotting assay

Purified platelets10 were mixed with fVIII-deficient plasma supplemented with 25 μg/mL corn trypsin inhibitor to give a composition of 1 × 108 platelets/mL. Various concentrations of fVIII were mixed with 10% fVIII-deficient plasma with inhibitory antibodies as indicated in Tyrode’s buffer lacking phosphate, and incubated for 1 hour at 22°C. For the activated platelet time assay, 100 µL of reconstituted platelet-rich plasma was mixed with 100 µL of fVIII ± inhibitory antibody for 1 minute at 37°C. The clotting reaction was started by adding 100 µL of a mixture containing factor XIa (200 pM), thrombin receptor activating peptide–protease-activated receptor 1 (PAR1) (30 µM), thrombin receptor activating peptide-PAR4 (300 µM), and CaCl2 (15 mM) in phosphate-free Tyrode’s albumin buffer. Fibrin strand formation was measured, in triplicate, with a BBL fibrometer in 300 µL sample cups.

Results

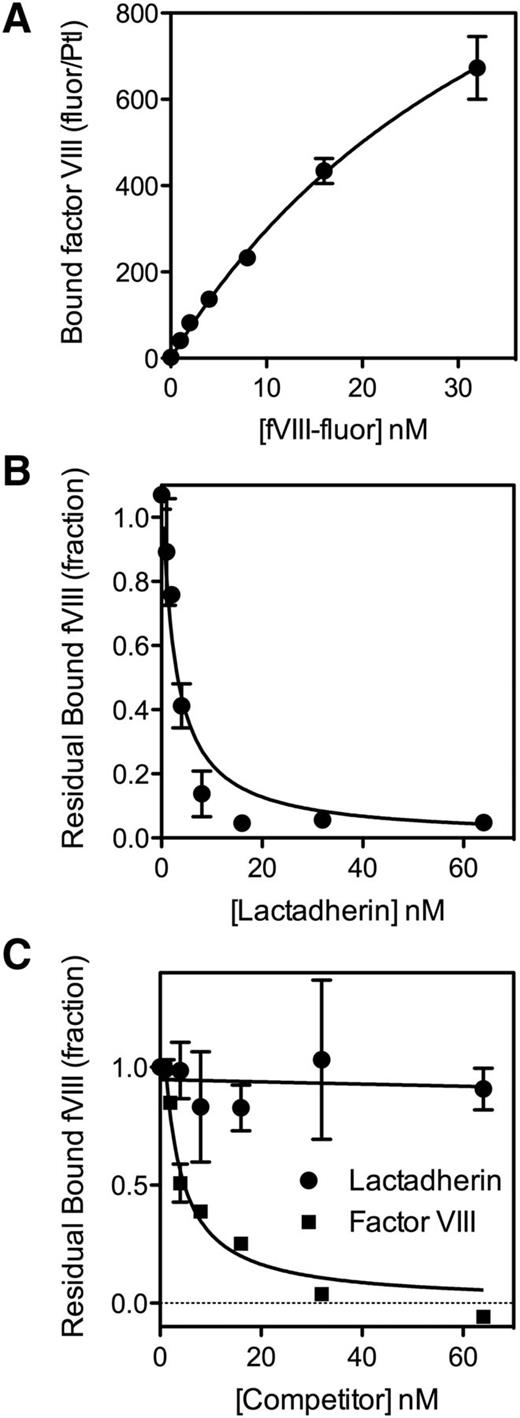

To test the hypothesis that platelets have nonphospholipid binding sites or receptors for fVIII,9,36 we evaluated competition by lactadherin for fVIII binding sites (Figure 1). fVIII-fluor bound to many binding sites on platelets stimulated by A23187 and thrombin (Figure 1A), consistent with the large number of binding sites predicted from extensive PS exposure. The number of binding sites was >100-fold more than on platelets stimulated by thrombin alone (Figure 2A).10 The addition of lactadherin, at increasing concentrations, blocked 98% of fVIII binding to stimulated platelets stimulated by A23187 and thrombin (Figure 1B). Half-maximal inhibition was similar to inhibitory concentrations on synthetic phospholipid membranes.35

Binding of fVIII to platelets and competition for fVIII binding sites. (A) fVIII-fluor, at various concentrations was mixed with platelets (1 × 108/mL) stimulated with 10 µM A23187 + 1 u/mL thrombin for 10 minutes. The sample was diluted 10-fold and fVIII-fluor was added for 10 minutes. Samples were further diluted to 1 × 106 platelets/mL and bound fVIII-fluor evaluated by flow cytometry. fVIII-fluor binding increased in a saturable manner. (B) fVIII-fluor (4 nM) was mixed with various concentrations of lactadherin prior to mixing with platelets stimulated by A23187 and thrombin. Lactadherin competed for at least 98% of binding sites indicating that PS is a critical determinant of most sites. (C) Platelets were stimulated with 1 u/mL thrombin alone for 1 minute prior to the addition of 3 u/mL hirudin. fVIII-fluor (4 nM) mixed with unlabeled fVIII or lactadherin at the indicated concentration was added to the platelets for 10 minutes prior to dilution and reading. Unlabeled fVIII competed for >95% of binding sites whereas lactadherin did not compete significantly. The fluorescence signal was corrected for the signal of unstimulated platelets with fVIII-fluor (supplemental Figure 2). Results are mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) from 2 experiments for each panel.

Binding of fVIII to platelets and competition for fVIII binding sites. (A) fVIII-fluor, at various concentrations was mixed with platelets (1 × 108/mL) stimulated with 10 µM A23187 + 1 u/mL thrombin for 10 minutes. The sample was diluted 10-fold and fVIII-fluor was added for 10 minutes. Samples were further diluted to 1 × 106 platelets/mL and bound fVIII-fluor evaluated by flow cytometry. fVIII-fluor binding increased in a saturable manner. (B) fVIII-fluor (4 nM) was mixed with various concentrations of lactadherin prior to mixing with platelets stimulated by A23187 and thrombin. Lactadherin competed for at least 98% of binding sites indicating that PS is a critical determinant of most sites. (C) Platelets were stimulated with 1 u/mL thrombin alone for 1 minute prior to the addition of 3 u/mL hirudin. fVIII-fluor (4 nM) mixed with unlabeled fVIII or lactadherin at the indicated concentration was added to the platelets for 10 minutes prior to dilution and reading. Unlabeled fVIII competed for >95% of binding sites whereas lactadherin did not compete significantly. The fluorescence signal was corrected for the signal of unstimulated platelets with fVIII-fluor (supplemental Figure 2). Results are mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) from 2 experiments for each panel.

Binding of fVIII-4Ala, with defective phospholipid affinity, to platelets. (A) fVIII-4Ala in complex with GMA8021-fluor were mixed with platelets stimulated as in Figure 1A. fVIII-4Ala had a 99% reduction in binding for A23187 + thrombin-stimulated platelets but a 55% reduction in binding to thrombin-stimulated platelets (B). Efficacy of fVIII or fVIII-4Ala in the factor Xase activity was evaluated in the presence of platelets stimulated with A23187 and thrombin (A23187) or by thrombin or PLVs with 4% or 20% PS content. The fVIII or fVIII-4Ala concentrations were 0.1 nM (A23187, 20% PS) or 1 nM (thrombin, 4% PS) mixed with factor IXa, 0.5 nM and factor X, 150 nM. Stimulated platelets, 1 × 108/mL, or 20 μM PLVs (4:20:76 PS:PE:PC or 20:20:60 PS:PE:PC, extruded) were added with the simultaneous addition of 0.2 u/mL thrombin and 1.5 mM Ca++. The reaction was stopped after 5 minutes by the addition of EDTA, and factor Xa was measured with chromogenic substrate S-2765. fVIII-4Ala supported ∼5% of the activity on A23187 + thrombin-stimulated platelets and ∼12% residual activity on thrombin-stimulated platelets. In contrast, fVIII-4Ala supported <1% residual activity on PLVs and activity was not significantly above background. Results in (A) are mean ± standard deviation (SD) for 4 measurements with the same fVIII-4Ala or fVIII concentrations between 1 to 8 nM and for (B) are mean ± SD from 2 experiments (A23187) or 3 experiments (thrombin, 4% PS and 20% PS) each performed in duplicate. PC, phosphatidylcholine; PE, phosphatidylethanolamine.

Binding of fVIII-4Ala, with defective phospholipid affinity, to platelets. (A) fVIII-4Ala in complex with GMA8021-fluor were mixed with platelets stimulated as in Figure 1A. fVIII-4Ala had a 99% reduction in binding for A23187 + thrombin-stimulated platelets but a 55% reduction in binding to thrombin-stimulated platelets (B). Efficacy of fVIII or fVIII-4Ala in the factor Xase activity was evaluated in the presence of platelets stimulated with A23187 and thrombin (A23187) or by thrombin or PLVs with 4% or 20% PS content. The fVIII or fVIII-4Ala concentrations were 0.1 nM (A23187, 20% PS) or 1 nM (thrombin, 4% PS) mixed with factor IXa, 0.5 nM and factor X, 150 nM. Stimulated platelets, 1 × 108/mL, or 20 μM PLVs (4:20:76 PS:PE:PC or 20:20:60 PS:PE:PC, extruded) were added with the simultaneous addition of 0.2 u/mL thrombin and 1.5 mM Ca++. The reaction was stopped after 5 minutes by the addition of EDTA, and factor Xa was measured with chromogenic substrate S-2765. fVIII-4Ala supported ∼5% of the activity on A23187 + thrombin-stimulated platelets and ∼12% residual activity on thrombin-stimulated platelets. In contrast, fVIII-4Ala supported <1% residual activity on PLVs and activity was not significantly above background. Results in (A) are mean ± standard deviation (SD) for 4 measurements with the same fVIII-4Ala or fVIII concentrations between 1 to 8 nM and for (B) are mean ± SD from 2 experiments (A23187) or 3 experiments (thrombin, 4% PS and 20% PS) each performed in duplicate. PC, phosphatidylcholine; PE, phosphatidylethanolamine.

Thrombin, without A23187, stimulated expression of 450 to 1800 binding sites, as previously reported.10 Lactadherin competed for <10% of these binding sites (Figure 1C) indicating that PS is not a critical component of most of these binding sites, consistent with the previously reported limited PS exposure.7,8,13,37 In contrast to lactadherin, unlabeled fVIII competed for >90% of these fVIII binding sites. Without thrombin inactivation by hirudin, the degree of competition by lactadherin reached 10% to 20% (supplemental Figure 1), suggesting that prolonged thrombin activation might increase PS exposure. We interpret the data to indicate that the majority of sites on thrombin-stimulated platelets are specific for fVIII and not defined by exposed PS.

We evaluated an fVIII mutant with defective phospholipid binding. Our prior work indicates that fVIII-4Ala (M2199A/F2200A, L2251A/L2252A) has <1% residual phospholipid membrane affinity and <1% fVIII activity18 (Figure 2). Binding of fVIII-4Ala was reduced ∼99% on platelets stimulated with A23187 and thrombin (Figure 2A). In contrast, fVIII-4Ala binding was ∼45% of fVIII binding on platelets stimulated by thrombin (Figure 2A). We note that residual binding to platelets stimulated by A23187 + thrombin was greater than on platelets stimulated by thrombin alone. This raises the possibility that platelets stimulated by A23187 and thrombin have at least as many non-PS fVIII binding sites as those stimulated by thrombin alone.

We also evaluated the function of fVIII-4Ala in the factor Xase complex supported by platelets vs PLVs (Figure 2B). Platelets stimulated with A23187 and thrombin supported 5% of the factor Xase activity of fVIII-4Ala compared with wild-type fVIII. Platelets stimulated by thrombin supported 12% residual activity of fVIII-4Ala. In contrast, PLVs supported <1% residual fVIII-4Ala activity. These results confirm that the phospholipid-binding motif of the fVIII-C2 domain is critical for most binding sites on A23187 + thrombin-stimulated platelets but not for most of the sites on thrombin-stimulated platelets. Residual activity of fVIII-4Ala on platelets indicates that the non-PS binding sites support function of fVIII.

We previously reported that binding of SF to the αIIbβ3 integrin results in a three- to sixfold increase in fVIII binding sites on thrombin-stimulated platelets.10 We asked whether SF bound to a platelet might serve as a binding site (Figure 3). Accordingly, we prepared SF38 in the presence of antifibrinogen antibodies coupled to Superose. Immobilization of fibrin was verified with a fluorescein-labeled antifibrinogen/antifibrin antibody. fVIII-fluor bound to fibrin-Superose with half-maximal binding at 1 to 2 nM (Figure 3A). fVIII-fluor bound to fibrin with similar affinity when fibrin was immobilized on Superose-59D8, an antibody against the amino terminus of the fibrin β chain,39 confirming that fibrin binds fVIII. fVIII-4Ala also bound to immobilized fibrin (supplemental Figure 3). The quantity bound was ∼30% of wild-type fVIII at 4 nM. These data indicate that fVIII binds to fibrin and that some of the fibrin-interactive residues differ from those that are critical for binding to PS-containing membranes.

Binding of fVIII to fibrin. (A) Various concentrations of fVIII-fluor were incubated with SF immobilized on antifibrinogen Superose beads. After 10 minutes, bound fVIII was evaluated by flow cytometry. Displayed results represent mean ± range of duplicates. Saturable binding of fVIII-fluor was observed. (B) Various concentrations of VWF were incubated with 4 nM fVIII-fluor for 15 minutes prior to mixing with immobilized fibrin–anti-fibrinogen Superose beads. VWF inhibited fVIII binding to fibrin. (C) Various concentrations of fVIII-C2 were incubated with fVIII-fluor prior to mixing with fibrin–antifibrinogen Superose beads. Experiments were performed in tris-buffered saline containing 0.02 M NaCl. fVIII-C2 competed with fVIII-fluor for binding to immobilized fibrin. Displayed data are corrected for measured background fluorescence with control beads lacking fibrin. Displayed results are mean ± SEM for 3 such experiments; also representative of 6 additional experiments with slightly different conditions (A), 2 experiments (B), and 2 experiments (C).

Binding of fVIII to fibrin. (A) Various concentrations of fVIII-fluor were incubated with SF immobilized on antifibrinogen Superose beads. After 10 minutes, bound fVIII was evaluated by flow cytometry. Displayed results represent mean ± range of duplicates. Saturable binding of fVIII-fluor was observed. (B) Various concentrations of VWF were incubated with 4 nM fVIII-fluor for 15 minutes prior to mixing with immobilized fibrin–anti-fibrinogen Superose beads. VWF inhibited fVIII binding to fibrin. (C) Various concentrations of fVIII-C2 were incubated with fVIII-fluor prior to mixing with fibrin–antifibrinogen Superose beads. Experiments were performed in tris-buffered saline containing 0.02 M NaCl. fVIII-C2 competed with fVIII-fluor for binding to immobilized fibrin. Displayed data are corrected for measured background fluorescence with control beads lacking fibrin. Displayed results are mean ± SEM for 3 such experiments; also representative of 6 additional experiments with slightly different conditions (A), 2 experiments (B), and 2 experiments (C).

VWF prevented binding of fVIII to immobilized fibrin, similar to the inhibition of fVIII binding to thrombin-stimulated platelets (Figure 3B).5 Because fVIII binding to platelets and to VWF is mediated in part by the C2 domain, we asked whether the isolated C2 domain (fVIII-C2) competes with fVIII for binding to fibrin (Figure 3C). fVIII-C2 competed with fVIII for binding to fibrin with 50% competition at ∼0.2 µM fVIII-C2. We note that the competition studies with fVIII-C2 were performed in a low-salt buffer, similar to buffer conditions required for fVIII-C2 to bind phospholipid membranes.19 These results indicate that fVIII binding to fibrin is similar to binding to platelets with regard to affinity, prevention by VWF, and participation of the C2 domain.

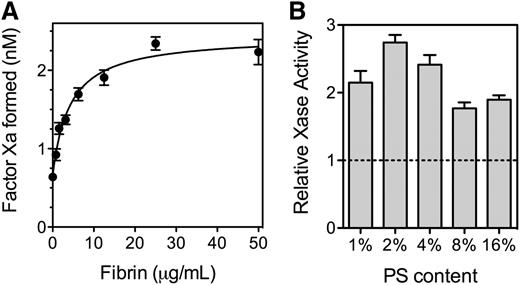

Because fVIII binds to SF, we asked what effect fibrin has on the activity of fVIII (Figure 4). SF increased activity of the factor Xase complex ∼2.7-fold with a half-maximal increase at 5 to 10 µg/mL fibrin (Figure 4A). At fibrin concentrations exceeding 200 µg/mL, factor Xase activity decreased (not shown) reaching baseline at ∼500 µg/mL. The size of the fibrin enhancement varied with the PS content of the PLVs supporting the reaction (Figure 4B). The degree of enhancement was more than twofold with 2% to 4% PS and 1.8-fold or less with 8% and 16% PS. These results indicate that SF increases factor Xase activity on PLV with PS content similar to thrombin-stimulated platelets.

Effect of fibrin on function of fVIII. (A) Various concentrations of fibrinogen were mixed with fVIII (0.5 nM), factor IXa (0.5 nM), factor X (150 nM), and PLVs (50 μM) (4:20:76 PS:PE:PC, extruded) prior to the simultaneous addition of 0.2 u/mL thrombin and 1.5 mM Ca++. The reaction was stopped after 5 minutes by the addition of EDTA, and factor Xa was measured with chromogenic substrate S-2765. Fibrin increased activity ∼3.5-fold and the half-maximal effect was observed at ∼5 µg/mL. The smooth line represents a nonlinear least squares curve fit assuming a single, saturable fibrin-binding site (B). The experiment in (A) was repeated with PLVs of various PS content and 0.5 nM fVIII. All vesicles were extruded and had 20% PE with the balance as PC. Activity is displayed as the Vmax / V0 ratio with increasing fibrin from the respective curve fits (as in Figure 4A). Phospholipid concentrations were 1% PS (200 µM), 2% PS (100 µM), 4% PS (50 µM), and 8% and 16% PS (10 µM). Results are mean ± SD from 6 experiments (A) and from 2 experiments performed in duplicate for each vesicle type (B).

Effect of fibrin on function of fVIII. (A) Various concentrations of fibrinogen were mixed with fVIII (0.5 nM), factor IXa (0.5 nM), factor X (150 nM), and PLVs (50 μM) (4:20:76 PS:PE:PC, extruded) prior to the simultaneous addition of 0.2 u/mL thrombin and 1.5 mM Ca++. The reaction was stopped after 5 minutes by the addition of EDTA, and factor Xa was measured with chromogenic substrate S-2765. Fibrin increased activity ∼3.5-fold and the half-maximal effect was observed at ∼5 µg/mL. The smooth line represents a nonlinear least squares curve fit assuming a single, saturable fibrin-binding site (B). The experiment in (A) was repeated with PLVs of various PS content and 0.5 nM fVIII. All vesicles were extruded and had 20% PE with the balance as PC. Activity is displayed as the Vmax / V0 ratio with increasing fibrin from the respective curve fits (as in Figure 4A). Phospholipid concentrations were 1% PS (200 µM), 2% PS (100 µM), 4% PS (50 µM), and 8% and 16% PS (10 µM). Results are mean ± SD from 6 experiments (A) and from 2 experiments performed in duplicate for each vesicle type (B).

The constituents of the factor Xase complex were varied systematically to determine which steady state kinetic parameters of the factor Xase complex were altered (Table 1). The results indicated that SF increases the apparent affinity of fVIIIa for factor IXa by about fourfold. In addition, the Vmax increased by 50% and the KM decreased by about 50%. Thus, the largest effect on parameters of steady state kinetics is on the apparent affinity of fVIIIa for factor IXa.

Effect of fibrin on parameters of factor Xase complex

| . | KM (fX) nM . | VMax (fXa formed) nM/5 min . | KD apparent fVIIIa < − > fIXa nM . | KD apparent (phospholipid*) µM . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 57 ± 10 | 2.5 ± 0.1 | 19 ± 2 | 37 ± 4 |

| + fibrin | 32 ± 5 | 3.7 ± 0.2 | 5 ± 1 | 32 ± 6 |

| . | KM (fX) nM . | VMax (fXa formed) nM/5 min . | KD apparent fVIIIa < − > fIXa nM . | KD apparent (phospholipid*) µM . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 57 ± 10 | 2.5 ± 0.1 | 19 ± 2 | 37 ± 4 |

| + fibrin | 32 ± 5 | 3.7 ± 0.2 | 5 ± 1 | 32 ± 6 |

Parameters were evaluated in the presence or absence of 20 µg/mL fibrin. Fibrinogen was exposed to 0.1 u/mL thrombin for 2 minutes prior to the addition of 0.3 u/mL hirudin. Concentrations of each component were varied to evaluate the KM, VMax, and apparent dissociation constants. Baseline concentrations were as per Figure 4 description.

Extruded PLVs had composition of PS:PE:PC (4:20:76).

Our data suggest that SF has relatively few binding sites that increase fVIII activity. Maximal enhancement of fVIII activity occurs with a fibrin monomer/fVIII ratio of ∼30/1 (Figure 4A). Modifying the experimental protocol to increase or decrease the size of SF units by two- to sixfold did not affect the effective concentration (data not shown). Thus, it appears that the ratio of fibrin monomer/fVIII activity enhancing site is determined by a unique property of a small fraction of fibrinogen molecules.

We evaluated fibrin prepared from fibrinogen of various types (Table 2). The results appear to exclude γ’ fibrin as the species that enhances fVIII activity and indicate that plasminogen/plasmin, VWF, or fibronectin associated with fibrin are not likely to be components of the complex that increases activity. Further, we evaluated a polyclonal antibody against fibrin fragment E and two different polyclonal antibodies against fibrinogen, as well as polyclonal antibodies to plasminogen, fibronectin, and VWF. None of these antibodies inhibited binding of fVIII to immobilized fibrin or inhibited the fibrin-mediated increase in Xase activity. Thus, these data imply that the fVIII binding site on SF is comprised of subunits that are not dominant epitopes and are a minor component of the total fibrin.

Effect of fibrin preparation on enhancement of fVIII activity

| Fibrinogen source . | EC50 (Fibrin) μg/mL . | FVIII activity enhancement VMax/V0 . | Comment . |

|---|---|---|---|

| HT HCI-0150R | 5 ± 2 | 2.4 ± 0.2 | Research-grade |

| ERL HFG 852 | 5 ± 2 | 3.2 ± 0.2 | Research-grade |

| ERL FIB2 | 2.4 ± 0.8 | 1.88 ± 0.07 | Plasminogen and VWF-depleted |

| ERL FIB3 | 1.7 ± 0.8 | 2.4 ± 0.2 | Plasminogen, VWF, and fibronectin-depleted |

| ERL P1 FIB | 0.5 ± 0.4 | 1.61 ± 0.07 | γ′ Fibrinogen-depleted |

| ERL P2 FIB | 0.6 ± 0.3 | 1.51 ± 0.04 | γ′ Fibrinogen-enriched |

| γA/γA | 3 ± 1 | 1.45 ± 0.05 | Recombinant (from CHO cells) |

| Fibrinogen source . | EC50 (Fibrin) μg/mL . | FVIII activity enhancement VMax/V0 . | Comment . |

|---|---|---|---|

| HT HCI-0150R | 5 ± 2 | 2.4 ± 0.2 | Research-grade |

| ERL HFG 852 | 5 ± 2 | 3.2 ± 0.2 | Research-grade |

| ERL FIB2 | 2.4 ± 0.8 | 1.88 ± 0.07 | Plasminogen and VWF-depleted |

| ERL FIB3 | 1.7 ± 0.8 | 2.4 ± 0.2 | Plasminogen, VWF, and fibronectin-depleted |

| ERL P1 FIB | 0.5 ± 0.4 | 1.61 ± 0.07 | γ′ Fibrinogen-depleted |

| ERL P2 FIB | 0.6 ± 0.3 | 1.51 ± 0.04 | γ′ Fibrinogen-enriched |

| γA/γA | 3 ± 1 | 1.45 ± 0.05 | Recombinant (from CHO cells) |

Parameters were evaluated in the presence of 0.5 nM fVIII, 0.5 nM factor IXa, 150 nM factor X, 20 μM extruded PS:PE:PC (4:20:76) vesicles, 0.2 unit/mL thrombin, and varying fibrin concentrations. Parameters were calculated from a curve fit of averaged data from 2 to 6 experiments each performed in duplicate.

CHO, Chinese hamster ovary.

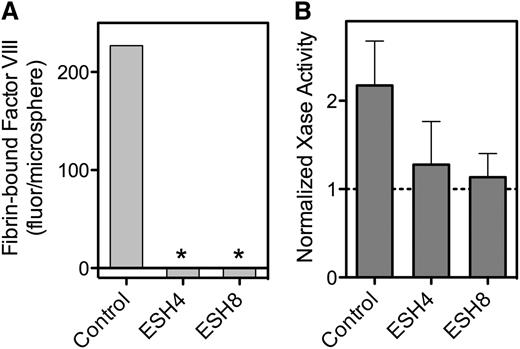

Because our data implicate the C2 domain in binding to fibrin, we asked whether mAbs against the C2 domain inhibit this interaction (Figure 5). Murine antibodies ESH4 and ESH8 define two of three major epitopes on the C2 domain.30 We found that both antibodies inhibit fVIII binding to fibrin (Figure 5A). We then tested whether the antibodies blocked the fibrin-mediated increase in factor Xase activity. ESH4 decreased but did not entirely prevent activity supported by PLV, as previously observed.16 However, the residual activity in the presence of ESH4 was not enhanced by the addition of SF (Figure 5B). As previously reported, ESH8 did not inhibit fVIII activity in the absence of fibrin33 but did prevent the increase mediated by fibrin (Figure 5B).

Effect of anti-fVIII mAbs on fVIII binding to fibrin. (A) fVIII-fluor, 4 nM, was incubated with 0.75 µg/mL ESH4 or 0.75 µg/mL ESH8 for 1 hour prior to mixing with fibrin–antifibrin–Superose or control beads lacking fibrin. ESH4 and ESH8 decreased binding to below control levels (*), observed when fVIII-fluor was incubated with control Superose beads. (B) fVIII was incubated with 10 μg/mL ESH4 or ESH8 for 1 hour at 23°C prior to the addition of factor IXa, factor X, thrombin, PLV, and Ca++ as noted in Figure 4A description. In the absence of antibodies, the addition of 10 µg/mL fibrin increased Xase activity about twofold. Fibrin did not increase activity in the presence of ESH4 or ESH8 above the levels observed in the absence of fibrin. Results are from a single experiment representative of 4 experiments (A) and are mean ± SD for 4 experiments (B).

Effect of anti-fVIII mAbs on fVIII binding to fibrin. (A) fVIII-fluor, 4 nM, was incubated with 0.75 µg/mL ESH4 or 0.75 µg/mL ESH8 for 1 hour prior to mixing with fibrin–antifibrin–Superose or control beads lacking fibrin. ESH4 and ESH8 decreased binding to below control levels (*), observed when fVIII-fluor was incubated with control Superose beads. (B) fVIII was incubated with 10 μg/mL ESH4 or ESH8 for 1 hour at 23°C prior to the addition of factor IXa, factor X, thrombin, PLV, and Ca++ as noted in Figure 4A description. In the absence of antibodies, the addition of 10 µg/mL fibrin increased Xase activity about twofold. Fibrin did not increase activity in the presence of ESH4 or ESH8 above the levels observed in the absence of fibrin. Results are from a single experiment representative of 4 experiments (A) and are mean ± SD for 4 experiments (B).

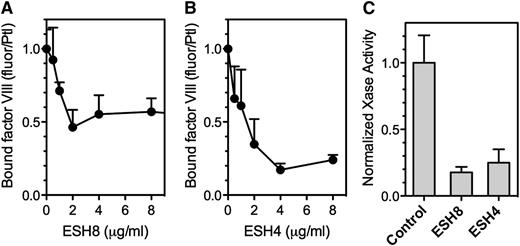

ESH8 decreased fVIII binding to thrombin-stimulated platelets by ∼50% (Figure 6A), whereas ESH4 inhibited fVIII binding by ∼80% (Figure 6B). Platelet-dependent factor Xase activity was inhibited 80% by ESH8 and 70% to 85% by ESH4 (Figure 6C). Thus, ESH8 and ESH4 inhibit both the binding of fVIII to thrombin-stimulated platelets and platelet-supported factor Xase activity. However, the inhibition of platelet-based activity by ESH8 is in marked contrast with its lack of inhibition of fVIII activity supported by PS-containing membranes.33

Effect of ESH4 and ESH8 on fVIII binding to thrombin-stimulated platelets. (A) fVIII-fluor was incubated with ESH8 for 1 hour on ice prior to mixing with platelets stimulated by thrombin as noted in Figure 1C description. The fVIII-fluor/antibody mix was added at a final fVIII concentration of 8 nM and allowed to bind for 10 minutes prior to dilution and reading. ESH8 decreased bound fVIII by ∼50%. (B) The same procedure was followed using ESH4. ESH4 inhibited ∼80% of fVIII binding. (C) ESH8 or ESH4, 10 µg/mL, was mixed with fVIII for 60 minutes prior to mixing with platelets (1 × 108/mL), factor IXa, factor X, Ca++, and thrombin. ESH8 inhibited 84% and ESH4 inhibited 78% of activity, respectively. To obtain average aggregate values, factor Xase activity was normalized to the value in the absence of ESH4 or ESH8 for each experiment. All data are corrected for the signal obtained from unstimulated platelets and normalized to facilitate comparison. Results are mean ± SEM for 3 experiments (A) and 4 experiments (B). (C) Mean ± SEM from 4 experiments, each performed in duplicate.

Effect of ESH4 and ESH8 on fVIII binding to thrombin-stimulated platelets. (A) fVIII-fluor was incubated with ESH8 for 1 hour on ice prior to mixing with platelets stimulated by thrombin as noted in Figure 1C description. The fVIII-fluor/antibody mix was added at a final fVIII concentration of 8 nM and allowed to bind for 10 minutes prior to dilution and reading. ESH8 decreased bound fVIII by ∼50%. (B) The same procedure was followed using ESH4. ESH4 inhibited ∼80% of fVIII binding. (C) ESH8 or ESH4, 10 µg/mL, was mixed with fVIII for 60 minutes prior to mixing with platelets (1 × 108/mL), factor IXa, factor X, Ca++, and thrombin. ESH8 inhibited 84% and ESH4 inhibited 78% of activity, respectively. To obtain average aggregate values, factor Xase activity was normalized to the value in the absence of ESH4 or ESH8 for each experiment. All data are corrected for the signal obtained from unstimulated platelets and normalized to facilitate comparison. Results are mean ± SEM for 3 experiments (A) and 4 experiments (B). (C) Mean ± SEM from 4 experiments, each performed in duplicate.

To evaluate the importance of inhibition by ESH4 and ESH8 in a more physiologic system, we developed an activated platelet clotting time (Figure 7). Purified platelets were reconstituted with fVIII-deficient plasma supplemented with various concentrations of fVIII. The reaction was initiated by simultaneous addition of factor XIa, thrombin receptor activation peptides for PAR1 and PAR4, and Ca++. The results indicated a log-linear relationship between fVIII concentration and time to fibrin strand formation over a wide fVIII concentration range (Figure 7A). When ESH4 was preincubated with 1 u/mL fVIII, the antibody inhibited 99% of fVIII activity (Figure 7A). In contrast, the degree of inhibition ranged from 30% to 40% in commercial aPTT and chromogenic assays (Figure 7B). When ESH4 was incubated with fVIII in VWF-deficient plasma, the degree of inhibition was increased to 60% in the aPTT assay and 99.7% in the activated platelet time. This result may be rationalized by recognizing that ESH4 and VWF compete for overlapping epitopes on fVIII, and VWF likely protected a fraction of fVIII from interacting with ESH4.

Effect of ESH4 and ESH8 on platelet-supported activity of fVIII. (A) Inhibition of 1 unit/mL fVIII activity by ESH4 and ESH8 was evaluated against an fVIII concentration curve in reconstituted platelet-rich plasma. Clotting was initiated by the simultaneous addition of factor XIa, thrombin receptor activation peptides, and Ca++. A log-linear plot demonstrates sensitivity to fVIII. ESH4 or ESH8 was incubated with fVIII in the presence of 10% fVIII-deficient plasma for 1 hour prior to mixing with additional fVIII-deficient plasma and initiation of clotting. ESH4 inhibited activity to a greater extent than ESH8. Results are mean ± SEM for triplicates, representative of 3 experiments performed in full and 5 performed with fewer fVIII concentrations. (B) Bar graph comparing residual fVIII activity in various plasma-based activities. aPTT and chromogenic assay results represents mean ± SEM using commercial aPTT and chromogenic reagents. Inhibition was also evaluated in reconstituted plasma and platelet-rich plasma lacking VWF (aPTT [-VWF]), (act platelet [-VWF]). Results are from 4 experiments (aPTT, chromogenic); activated platelets mean ± SD for 3 experiments, activated platelets without VWF (1 experiment). (C) Bar graph comparing residual fVIII activity in the presence of 10 µg/mL ESH8. aPTT without VWF (aPTT [-VWF]).32 Values on activated platelets are mean ± SEM for 2 experiments and 1 experiment for plasma lacking VWF.

Effect of ESH4 and ESH8 on platelet-supported activity of fVIII. (A) Inhibition of 1 unit/mL fVIII activity by ESH4 and ESH8 was evaluated against an fVIII concentration curve in reconstituted platelet-rich plasma. Clotting was initiated by the simultaneous addition of factor XIa, thrombin receptor activation peptides, and Ca++. A log-linear plot demonstrates sensitivity to fVIII. ESH4 or ESH8 was incubated with fVIII in the presence of 10% fVIII-deficient plasma for 1 hour prior to mixing with additional fVIII-deficient plasma and initiation of clotting. ESH4 inhibited activity to a greater extent than ESH8. Results are mean ± SEM for triplicates, representative of 3 experiments performed in full and 5 performed with fewer fVIII concentrations. (B) Bar graph comparing residual fVIII activity in various plasma-based activities. aPTT and chromogenic assay results represents mean ± SEM using commercial aPTT and chromogenic reagents. Inhibition was also evaluated in reconstituted plasma and platelet-rich plasma lacking VWF (aPTT [-VWF]), (act platelet [-VWF]). Results are from 4 experiments (aPTT, chromogenic); activated platelets mean ± SD for 3 experiments, activated platelets without VWF (1 experiment). (C) Bar graph comparing residual fVIII activity in the presence of 10 µg/mL ESH8. aPTT without VWF (aPTT [-VWF]).32 Values on activated platelets are mean ± SEM for 2 experiments and 1 experiment for plasma lacking VWF.

When ESH8 was incubated with 1 u/mL fVIII, the delay in fibrin strand formation was consistent with a 97% reduction in fVIII activity (Figure 7A,C). Because ESH8 inhibits release of fVIIIa from VWF,33 experiments with ESH8 were also performed with VWF-deficient plasma. ESH8 inhibited 93% of fVIII activity in the absence of plasma VWF. This contrasts with the degree of inhibition by ESH8 in standard aPTT and chromogenic fVIII activity assays (Figure 7C), where there is less inhibition in the presence of VWF and no inhibition in the absence of VWF. Overall, the results indicate that the degree of inhibition in a platelet and plasma-based system is better predicted by fVIII binding to platelets and to fibrin than to PLVs.

Discussion

Our results confirm the hypothesis articulated by Nesheim et al9,36 that thrombin-stimulated platelets have fVIII(a) binding sites that are distinct from membrane PS. They expand on the observation that most platelet binding sites are dependent upon SF bound to αIIbβ3 integrins. We find that fVIII binds to SF and that the binding characteristics of that interaction parallel the interaction with the non-PS binding sites of platelets. Notably, fVIII has similar affinity for fibrin and binding is blocked by VWF in a similar manner. Further, the inhibition of fVIII binding to fibrin predicts the inhibitory activity of two mAbs to fVIII in platelet-based assays. Thus, they support a hypothesis that platelet-bound fibrin is a component of non-PS platelet binding sites.

These results are in agreement with several prior reports. Nesheim et al reported that thrombin-stimulated platelets express fVIII binding sites and that factor Va did not compete for these platelet sites.5,9,36 Prior reports indicate that the C2 domain of fVIII participates in binding to platelets and this study confirms participation of the C2 domain in binding platelets and SF.15,40 Our results extend beyond the prior results in showing that lactadherin, a PS-binding protein that competes for >99% of sites on PS-containing vesicles recognized by fVIII,35 does not compete for most sites on thrombin-stimulated platelets. Further, we have shown that a fVIII mutant with severely impaired phospholipid affinity18 retains binding to thrombin-stimulated platelets, thus confirming the participation of the fVIII-C2 domain in binding to platelet sites that are not determined by membrane PS.

This report identifies a role of the fVIII-C2 domain in mediating binding to non-PS sites on platelets. However, it doesn’t indicate that the C2 domain is entirely responsible for platelet binding or that membrane PS is not required for full activity of fVIII. Although lactadherin did not compete for a class of fVIII binding sites, it did diminish activity by >99%, as previously reported.13 Further work will be required to indicate whether the residual PS is needed for factor IXa binding or activity, or whether PS that is below the threshold required for fVIII binding,1 may still interact with fVIII and effect some change required for full activity. Additional work will also be required to indicate whether the C1 domain15-17 or A3 domain41 also contribute to binding the fibrin-dependent platelet sites.

Our data build on our prior report indicating that SF binding to the αIIbβ3 integrin of platelets increases binding sites for fVIIIa.10 In our prior report, fibrin adsorbed to polystyrene beads had no detectible binding to fVIII. In this study, we found that SF bound to an antibody on a porous Superose matrix does bind fVIII. This difference suggests that surface binding of SF can block the fVIII binding site or lead to a conformational change that alters the site. The results in this study make it plausible that SF bound to the αIIbβ3 integrin may function as the major fVIII binding site.

In the absence of VWF, ESH8 doesn’t inhibit activity of fVIII on PS-containing membranes.33 Thus, ESH8 inhibition of fVIII binding to fibrin (Figure 5), inhibition of fVIII binding to platelets (Figure 6), and inhibition of platelet-based procoagulant activity (Figure 7) appear to identify a new function of the ESH8 epitope or a surface that is sterically hindered by ESH8.

The importance of the ESH4 epitope for membrane binding is modest when the PS content of vesicles is above 15% and excess vesicles are present.16 Thus, it is not surprising that ESH4 causes only modest inhibition of fVIII activity in the commercial aPTT and chromogenic fVIII activity assays (Figure 7B). In contrast to limited inhibition in the clinical fVIII assays, ESH4 blocked binding to fibrin and >80% of binding to thrombin-stimulated platelets. This correlated to an 85% reduction of platelet factor Xase activity (Figure 6C) and 99% reduction of platelet-supported procoagulant activity (Figure 7B). In VWF-deficient plasma, the inhibition of platelet procoagulant activity was greater. This suggests that the nonphospholipid fVIII binding sites are dominant in the clotting of platelet-rich plasma.

Our data appear to exclude the possibility that the most common fibrinogen-binding proteins of plasma, or the γ’ splice variant determine the fVIII activity enhancement (Table 2). Thus, there appear to be 3 possible explanations for the relative scarcity of sites that enhance fVIII activity. First, the active site may be a conformation-sensitive domain of fibrin, possibly affected by assembly of fibrin molecules or ligation to the αIIbβ3 integrin. Second, the fibrin may act in concert with an unidentified fibrin(ogen) binding protein that is present to greater degrees in some fibrinogen preparations. Third, the fVIII-binding site may include a motif of fibrin subject to an infrequent posttranslational modification, such as prolyl hydroxylation of α fibrinogen.42 We are currently investigating these possibilities.

The activated platelet time assay we used differs from a prior platelet-based coagulation assay in that platelets were activated at the outset by peptides that stimulate PAR1 and PAR4.43 The results with our assay contrast with results from reported fVIII assays. First, the range over which fibrin strand formation had a log-linear relationship of fVIII concentration to coagulation time is 0.0003 to 0.3 units/mL. In contrast, established fVIII assays have an fVIII time-log linear range of 0.01 to 0.3 units/mL.44 Thus, a coagulation assay based on the activated platelet membrane rather than PLVs may have potential as the basis of a clinical assay with a broader range. In addition, the sensitivity of the assay to fVIII inhibition by ESH4 and ESH8 differed by >10-fold compared with commercially available 1-stage and chromogenic assays. These data suggest that an assay in which fVIII activity is supported by the activated platelet membrane may provide supplementary clinical information for patients who have developed inhibitor antibodies.

In conclusion, our results demonstrate that platelets have non-PS binding sites for fVIII. SF is required to constitute these sites and fibrin binds fVIII with properties that suggests that fibrin or a complex of fibrin with another molecule is the best candidate for the nonphospholipid site. Activity of fVIII on the non-PS platelet sites has qualitatively different susceptibility to anti-fVIII antibodies in a platelet-based coagulation assay. Thus, these data provide motivation for studies to identify the platelet fVIII-binding site, clarify the contribution of these sites to fVIII function, and development of an assay to evaluate the clinical importance of fVIII binding to the non-PS platelet sites.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is an Inside Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Alisa Wolberg for helpful discussions about fibrin(ogen) and providing recombinant γA/γA fibrinogen.

This study was supported by a Department of Veterans Affairs grant to G.E.G. and a research grant from Baxter Healthcare. The authors are indebted to James Morrissey, Stephanie Smith, John (Pete) Lollar, and Shannon Meeks for helpful discussions and sharing reagents early in the course of these studies.

Authorship

Contribution: G.E.G., J.S., and V.A.N. planned experiments in consultation with S.W.P.; V.A.N. and J.S. performed experiments; J.R. provided a critical reagent; G.E.G. drafted the manuscript and all authors revised the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: G.E.G., J.S., and V.A.N. have applied for a patent related to measuring fVIII activity, based on the results in this manuscript. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Gary E. Gilbert, VA Boston Healthcare System, 1400 VFW Parkway, West Roxbury, MA 02132; e-mail: gary_gilbert@hms.harvard.edu.

![Figure 7. Effect of ESH4 and ESH8 on platelet-supported activity of fVIII. (A) Inhibition of 1 unit/mL fVIII activity by ESH4 and ESH8 was evaluated against an fVIII concentration curve in reconstituted platelet-rich plasma. Clotting was initiated by the simultaneous addition of factor XIa, thrombin receptor activation peptides, and Ca++. A log-linear plot demonstrates sensitivity to fVIII. ESH4 or ESH8 was incubated with fVIII in the presence of 10% fVIII-deficient plasma for 1 hour prior to mixing with additional fVIII-deficient plasma and initiation of clotting. ESH4 inhibited activity to a greater extent than ESH8. Results are mean ± SEM for triplicates, representative of 3 experiments performed in full and 5 performed with fewer fVIII concentrations. (B) Bar graph comparing residual fVIII activity in various plasma-based activities. aPTT and chromogenic assay results represents mean ± SEM using commercial aPTT and chromogenic reagents. Inhibition was also evaluated in reconstituted plasma and platelet-rich plasma lacking VWF (aPTT [-VWF]), (act platelet [-VWF]). Results are from 4 experiments (aPTT, chromogenic); activated platelets mean ± SD for 3 experiments, activated platelets without VWF (1 experiment). (C) Bar graph comparing residual fVIII activity in the presence of 10 µg/mL ESH8. aPTT without VWF (aPTT [-VWF]).32 Values on activated platelets are mean ± SEM for 2 experiments and 1 experiment for plasma lacking VWF.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/126/10/10.1182_blood-2015-01-620245/4/m_1237f7.jpeg?Expires=1765894456&Signature=YEK8Er8BvrwYHgWKaAOm4IE9BZcpRv12DhW~~YkJ6WBSPkJhv6lT423D74hp9OfEWlq~qxw563nT1Oz-j0T8quw2lrkS7goigYFqc5MWlOHtkr9zkdww8Um-VE9k~Fx20GXsYVBcAYUcTw2XaTl9Mv8wUnLzSPwZT10~zLRhqjWpiCdIcRcuPwlbT8aSsTBtSQu2DYXXoKR~SKWrMjGp0DQUX2Q3knioxWwy00WbbWv-4ItQeYAXPpXU1OO16KR4MOnV~m-HNY6eDcOK601oxIQKA7bn6vtreSlsLdsy2xBhATO5bK76t1SQ30L8H6TcGAmvFC7VS2vOJH~ucGUAOg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)