Key Points

Pirfenidone ameliorates cGVHD in murine models with distinct pathophysiology.

The efficacy of pirfenidone is associated with inhibition of macrophage infiltration and TGF-β production.

Abstract

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation is hampered by chronic graft-versus-host disease (cGVHD), resulting in multiorgan fibrosis and diminished function. Fibrosis in lung and skin leads to progressive bronchiolitis obliterans (BO) and scleroderma, respectively, for which new treatments are needed. We evaluated pirfenidone, a Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved drug for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, for its therapeutic effect in cGVHD mouse models with distinct pathophysiology. In a full major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-mismatched, multiorgan system model with BO, donor T-cell responses that support pathogenic antibody production are required for cGVHD development. Pirfenidone treatment beginning one month post-transplant restored pulmonary function and reversed lung fibrosis, which was associated with reduced macrophage infiltration and transforming growth factor-β production. Pirfenidone dampened splenic germinal center B-cell and T-follicular helper cell frequencies that collaborate to produce antibody. In both a minor histocompatibility antigen–mismatched as well as a MHC-haploidentical model of sclerodermatous cGVHD, pirfenidone significantly reduced macrophages in the skin, although clinical improvement of scleroderma was only seen in one model. In vitro chemotaxis assays demonstrated that pirfenidone impaired macrophage migration to monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) as well as IL-17A, which has been linked to cGVHD generation. Taken together, our data suggest that pirfenidone is a potential therapeutic agent to ameliorate fibrosis in cGVHD.

Introduction

Chronic graft-versus-host disease (cGVHD) is a significant barrier of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT) because of its high incidence and severity. Fibrosis affecting skin and internal organs is the predominant clinical feature of cGVHD. Bronchiolitis obliterans (BO) and scleroderma, with their respective fibrotic bronchiolar and cutaneous changes,1 are two of the most devastating outcomes. Systemic immune suppression is the recommended treatment, although such treatment is not always effective in controlling disease and does not alleviate established fibrosis.2 In addition, systemic immune suppression can be associated with high infection and relapse rates.3 New therapies that reverse fibrosis without compromising immune function are urgently needed. Several preclinical models have been developed to study cGVHD pathogenesis and test potential interventions.4-8 For example, we have developed a murine model that uses full major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-mismatched donors and recipients (B6→B10.BR) and incorporates a clinically relevant pretransplantation conditioning regimen of high-dose cyclophosphamide and total body irradiation (TBI), leading to the development of systemic fibrosis affecting the lung, liver, and gastrointestinal tract, but not the skin. Studies from this model pointed to autoimmunity as the key of cGVHD pathogenesis, where induced germinal center (GC) reactions support the production of autoantibodies that are deposited in target organs causing fibrosis.9-11 Two lethal irradiation models (B10.D2→BALB/c12 and B6 parent→B6D2F111 ), using minor histocompatibility antigen-mismatched or MHC-haploidentical donors and recipients, develop scleroderma as the main cGVHD manifestation, which is dependent on tissue F4/80+ macrophage infiltration.

Pirfenidone (5-methyl-1-phenyl-2- (1H)-pyridone) is a small molecule known for its antifibrosis properties. In bleomycin-induced lung injury and lung allotransplant models, pirfenidone decreased hydroxyproline, fibrosis, procollagen I and II, platelet-derived growth factor isoforms, transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β), fibroblast growth factor, and IL-13.13-21 Moreover, pirfenidone increases scavenger of reactive oxygen species22 and decreases inflammation pathways that initiate fibrosis, such as nitrites, IL-623 and tumor necrosis factor-α.24 Recently, pirfenidone has been Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved as treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis treatment, reducing disease progression and increasing lung function, exercise tolerance, and progression-free survival.25 Pirfenidone showed efficacy in treating localized scleroderma in a phase 2 study.26

In this study, we explored the efficacy of pirfenidone in multiple murine cGVHD models and found that pirfenidone reversed lung disease in the BO model. cGVHD patients with BO have high morbidity and mortality, and therapeutic options for advanced BO are limited.27 We show that pirfenidone treatment of mice with active cGVHD was associated with a reduction of macrophage infiltration, TGF-β production, and the GC reaction. Importantly, pirfenidone administration had long-lasting effects and could reverse later-stage lung disease. In the sclerodermatous cGVHD models, pirfenidone diminished macrophage infiltration in both models, although the clinical benefit was variable with significant attenuation of clinical and pathologic changes evident only in the B10.D2→BALB/c model.

Materials and methods

Mice

For the BO model, C57Bl/6 (B6, H2b) mice were purchased from the National Cancer Institute. B10.BR (H2k) mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory. For the BALB/c (H2d)→B10.D2 (H2d) model, mice were propagated in the animal facility at the Johns Hopkins University Cancer Research Building I. For the B6 parent→B6D2F1(H2b/d) model, mice were purchased from ARC (Perth, Australia) and used between 8 and 13 weeks of age. CSFR−/+ mice were provided by Richard E. Stanley (Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York, New York). Mice were housed in a specific-pathogen–free facility and used with the approval of each institution’s animal care committee.

Bone marrow transplantation

For the BO model, B10.BR mice were conditioned with Cytoxan (Sigma, 120 mg/kg/day, intraperitoneally, day-3 and -2) and TBI (8.3 Gy, day-1), followed by infusion of 10×106 B6 T cell–depleted bone marrow (TCD-BM) only as healthy control, or plus 75 000 purified splenic T cells to induce cGVHD (day 0).9,10 For the B10.D2 to BALB/c scleroderma model, BALB/c mice were conditioned with TBI (7.75 Gy, day 0), followed by infusion of 10 × 106 B10.D2 TCD-BM only or plus 1.8 × 106 CD4 and 0.9 × 106 CD8 T cells (day 0).12 For the B6 to B6D2F1 scleroderma model, B6D2F1 mice were conditioned with TBI (11Gy split into 2 doses, day-1) followed by infusion of 5 × 106 B6 TCD-BM only or plus 1 × 106 purified T cells (day 0).11 Mice were monitored daily, and examined twice per week for clinical signs of cGVHD. Assessment of cutaneous GVHD in the B10.D2 to BALB/c scleroderma model was done as previously described.28 For graft-versus-leukemia (GVL) study, 0.1 × 106 MLL-AF9-GFP leukemia cells were infused on day 0 into lethally irradiated recipients of B6 BM (5 × 106) from either wild-type or CSF1R−/− fetal liver only or plus 106 purified T cells on day 0.29 Tumor was detected in peripheral blood by GFP staining.

Pirfenidone treatment

Pirfenidone was manufactured to Good Manufacturing Practice grade at SAFC Pharma (St. Louis, MO) under contract with the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Disease. The crystalline drug compound was certified to be pure (≥97% area by high-performance liquid chromatography) at the University of Minnesota using a process supplied by SAFC Natick. The drug has been used successfully in nonhuman primate models of fibrosis.30 In this study, pirfenidone crystals were ground down into fine powder using mortar and pestle and then suspended in 0.4% methylcellulose. Mice were given pirfenidone (400 mg/kg) by oral gavage from days 28 to 56 or days 56 to 84 (BO model), days 21 to 55 (B10.D2 to BALB/c model) or days 14 to 27 or 14 to 41 (B6 to B6D2F1 model). Mice in the vehicle control group were treated with the same volume of 0.4% methylcellulose.

Pulmonary function tests

Pulmonary function tests were performed as described previously.31 Briefly, Nembutal-anesthetized mice were intubated and ventilated using the Flexivent system (Scireq). Pulmonary resistance, elastance, and compliance were recorded and analyzed using the Flexivent software version 5.1.

Hydroxyproline assay

Mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation. Lungs were removed and homogenized in 200 μL deionized water. 100 μL aliquot of the homogenate was hydrolyzed in 100 μL concentrated hydrogen chloride (Sigma 320331) for 3 hours in 120°C. After centrifugation, 5 to 10 μL of supernatant was carefully removed to a 96-well plate and incubated in a 56°C oven until dry. The amount of hydroxyproline in the lung homogenate aliquots was measured by Hydroxyproline Assay Kit (Sigma MAK008). The result was adjusted to reflect content in the whole sample.

Histopathology and immunostaining

Lung and spleen were embedded in Optimal Cutting Temperature compound, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C. Lungs were inflated by 75% optimal cutting temperature before harvest. For trichrome staining, 8-µm cryosections were fixed for overnight in Bouin’s solution and stained with the Masson’s trichrome staining kit (Sigma HT15). Collagen deposition was quantified as a ratio of blue area to total area using ImageJ.

For immunostaining, acetone-fixed 8-µm cryosections were stained with indicated markers. For GC detection, frozen sections of spleens were stained with rhodamine-peanut agglutinin and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Vector Laboratories). For macrophage and TGF-β staining, frozen sections of lung or skin were stained with anti–CD68-ef660 (FA-11, eBioscience 50-0681) or rabbit anti-mouse F4/80/TGF-β (Abcam ab66043/ab100790) followed by anti-rabbit HRP-DAB staining Kit (R&D CTS005). For immunoglobulin deposition, sections of lung were stained with goat anti-mouse Ig (BD 55401). Confocal images were acquired on an Olympus FluoView500 Confocal Laser Scanning Microscope at 200X, analyzed using FluoView3.2 software (Olympus) and quantified by ImageJ.

Macrophage migration assay

J774 cells were cultured with vehicle, 0.25 or 0.5 mg/mL pirfenidone for 24 hours. IL-17A (100 ng/mL; eBioscience) or MCP-1/CCL2 (100 ng/mL; Gibco) was added to the lower chamber as chemoattractant, and J774 cells were plated in the upper chamber of 96 transwell plates (Corning 3374). Cells were allowed to migrate through the insert membrane for 4 hours at 37°C under a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Calcein AM solution (Molecular Probes) was added to each well of the receiver plate. Plates were incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator for 60 minutes. The plate was read by SpectraMax i3X from Molecular Devices at 485/530.32

Intravascular staining and lung single-cell suspension preparation

Mice were injected with 4 μg of CD45-FITC antibody (CD45 iv) (eBioscience) through a tail vein and rested for 5 minutes before being sacrificed by cervical dislocation. Lungs were removed, dissociated by gentleMACS dissociator (Miltenyi Biotec), and digested in collagenase D (2 mg/mL) for 30 minutes in a 37°C incubator. The digested lungs were filtered through 40-μm cell straining to create the single-cell suspension.

Flow cytometry

For T-follicular helper (Tfh) and GC B cells, single-cell suspension of spleens was obtained and stained with fixable viability dye, fluorochrome-labeled anti-CD4 (RM4-5, BD), anti-CXCR5 (SPRCL5, eBioscience), anti-PD-1 (J43, eBioscience), anti-CD19 (eBio1D3, eBioscience), anti-GL7 (GL-7, eBioscience), and anti-Fas (J02, BD). GC B cells were defined as Fas and GL7 double-positive CD19 B cells. Tfh cells were defined as PD1 and CXCR5 high CD4 T cells. Cells were analyzed on BD LSRFortessa. For flow analysis of lung macrophages, single-cell suspension of lung was stained with anti-CD45-PE (CD45 ex vivo, 30-F11, eBioscience), anti-CD11c (3.9, eBioscience), anti-F4/80 (BM8, eBioscience), and antilatency-associated peptide (LAP; TW7-16B4, eBioscience). For cytokine production and regulatory T cells (Treg), cells were fixed and stained with anti-IL-17a, anti-IFN-γ and anti-Foxp3.

Treg suppression assay

Tregs, conventional CD4 T cells (Tcon), and antigen-presenting cells (APC) were isolated from naïve B6 mice. Tcons were labeled with carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester and stimulated with anti-CD3. Treg and Tcons were mixed at the indicated ratio. APCs were added to the system. Pirfenidone (0.1 or 0.25 mg/mL) or vehicle was either added to the culture media or used to pretreat Treg for 1 hour before washing and adding to Tcon and APCs. Carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester dilution was analyzed by flow cytometry on day 3.

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism 6 was used to conduct the statistical analysis. Groupwise comparisons were made by unpaired Student t test. Error bars indicated means ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Significance: *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001; ****P < .0001.

Results

Therapeutic administration of pirfenidone reverses fibrosis in a cGVHD BO model

To examine the efficacy of pirfenidone to reverse lung fibrosis caused by cGVHD, BO models were treated with pirfenidone from days 28 to 56 post-transplantation. In this model, pulmonary function loss and fibrotic change in the lung can be detected as early as day 28, and progresses to day 56.9 The loss of lung function is detected using the FlexiVent (SCIREQ) system for forced oscillations measurements including resistance (increase of airway pressure per volume increase when the lung expands), elastance (reduction of airway pressure per volume reduction when the lung recoils), and compliance (increase of lung volume per pressure increase when the lung expands).33 On day 56, cGVHD mice that received BM and T cells displayed fibrotic lung disease with higher resistance and elastance, and lower compliance compared with the BM only mice. Pirfenidone treatment from day 28 to day 56 significantly reduced lung fibrosis (P < .01) to comparable lung function with BM-only mice (Figure 1A).

Therapeutic administration of pirfenidone reverses fibrosis in cGVHD BO model. B10.BR mice were conditioned with cytoxan (120 mg/kg/day, intraperitoneally [IP], day-3 and day-2) and TBI (8.3 Gy, day-1), followed by infusion of 107 B6 T cell–depleted bone marrow only as healthy control, or plus 75 000 purified splenic T cells to induce cGVHD (day 0). In the treatment group, cGVHD mice received pirfenidone (400 mg/kg) from day 28 to day 56. (A) Pulmonary function tests on day 56 post-transplantation showed that pirfenidone restored lung function of cGVHD mice. Data are representative of 3 experiments with similar results. (B) Hydroxyproline assay of the right lungs harvested on day 56 indicated that pirfenidone significantly reduced hydroxyproline content. Five to 6 mice from each group were analyzed. Data are representative of 2 experiments with similar results. (C) Representative images of Masson’s trichrome staining images of lung (upper) and liver (lower). Collagen (blue stain) was quantified in (D) and (E). (F-G) Representative lung immunoglobulin deposition images and quantification. Data are representative of 2 experiments with similar results. *P ≤ .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001; data are shown as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

Therapeutic administration of pirfenidone reverses fibrosis in cGVHD BO model. B10.BR mice were conditioned with cytoxan (120 mg/kg/day, intraperitoneally [IP], day-3 and day-2) and TBI (8.3 Gy, day-1), followed by infusion of 107 B6 T cell–depleted bone marrow only as healthy control, or plus 75 000 purified splenic T cells to induce cGVHD (day 0). In the treatment group, cGVHD mice received pirfenidone (400 mg/kg) from day 28 to day 56. (A) Pulmonary function tests on day 56 post-transplantation showed that pirfenidone restored lung function of cGVHD mice. Data are representative of 3 experiments with similar results. (B) Hydroxyproline assay of the right lungs harvested on day 56 indicated that pirfenidone significantly reduced hydroxyproline content. Five to 6 mice from each group were analyzed. Data are representative of 2 experiments with similar results. (C) Representative images of Masson’s trichrome staining images of lung (upper) and liver (lower). Collagen (blue stain) was quantified in (D) and (E). (F-G) Representative lung immunoglobulin deposition images and quantification. Data are representative of 2 experiments with similar results. *P ≤ .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001; data are shown as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

To document pirfenidone’s effect on lung fibrosis, we measured hydroxyproline levels in the lung, which correlates with the amount of collagen—a major component of fibrotic tissue. The hydroxyproline level in cGVHD group lungs is ∼twofold higher than the non-cGVHD group, and pirfenidone treatment significantly reduced lung hydroxyproline content (P < .01) (Figure 1B), consistent with pulmonary function tests. In addition, Masson’s trichrome staining that identifies collagen by blue staining in tissue section was performed. Mice in the cGVHD group showed increased collagen deposition in the peribronchial and perivascular areas of lung and liver compared with the BM-only group; pirfenidone treatment significantly reduced collagen deposition in lung (P < .01) and liver (P < .05) (Figure 1C, quantified in D-E). Immunoglobulin deposition, which occurs in cGVHD was reduced by pirfenidone (Figure 1F, quantified in G). Taken together, these results showed that pirfenidone reversed lung fibrosis caused by cGVHD.

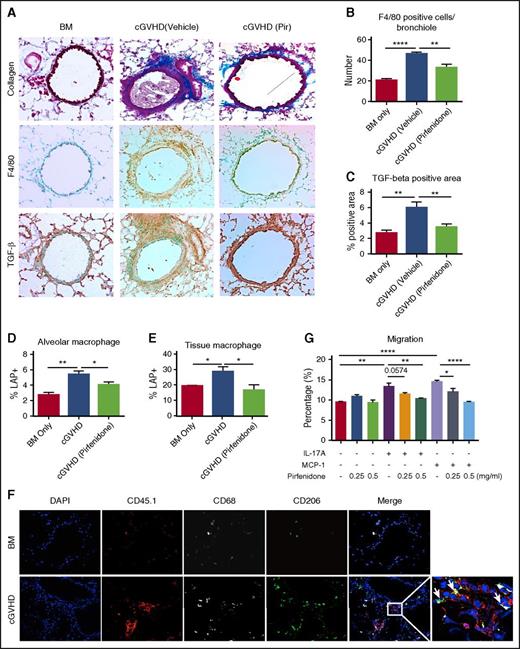

Pirfenidone reduces F4/80+ macrophage accumulation and TGF-β deposition in lung

Pirfenidone inhibits TGF-β signaling pathway19,20,23,34 that contribute to tissue fibrosis.35 TGF-β is preferentially produced from mononuclear cells following stem cell transplantation,36 including macrophages, that are potent TGF-β producers and required to induce cutaneous cGVHD model.11 TGF-β recruits circulating fibrocytes and inflammatory cells to the sites of tissue damage and induces the expression of fibrogenic cytokines (eg, PDGF and IL-13), as well as transcriptionally activates the collagen gene. In a B10.D2→BALB/c scleroderma model, TGF-β neutralization from day14 after allo-HSCT attenuated histologic abnormalities.36 Depleting tissue macrophages by antibody reversed pulmonary fibrosis in the BO model.11

To evaluate whether pirfenidone reduces macrophage infiltration and TGF-β production, serially sectioned slides of lung were stained with Masson’s trichrome stain, anti-F4/80 antibody, and anti-TGF-β antibody (Figure 2A). Macrophage and TGF-β were significantly increased in the cGVHD lungs (Figure 2B-C). The peribronchial and perivascular areas stained strongest and these are also the areas where extensive collagen deposition occurred, suggesting macrophages and TGF-β are mediators in cGVHD pathogenesis. Pirfenidone significantly reduces both macrophage and TGF-β in the lung.

Pirfendone reduces F4/80+macrophage accumulation and TGF-β deposition in lung. (A-C) Serial sections of lungs harvested on day 56 post-transplantation were stained with trichrome staining (A, top panels), anti-F4/80 antibody (A, middle panels), and anti–TGF-β antibody (A, bottom panels). F4/80-positive cell number and TGF-β staining area were quantified in (B) and (C). Pirfenidone reduced macrophages infiltration and TGF-β production in lung. (D-E) Mice were transplanted as described in Figure 1. cGVHD mice were treated by pirfenidone for a week from days 28 to 35. On day 35, LAP expression in alveolar macrophages (D) and tissue macrophages (E) were analyzed by flow cytometry. Pirfenidone significantly reduced LAP expression in both alveolar and tissue macrophages. (F) Donor B6 mice are CD45.1 and B10.BR CD45.2 recipient mice were used. Lung sections were fixed and stained with anti-CD45.1 (donor marker, red), CD68 (gray), and CD206 (green). Arrows pointed at cells that are CD45.1+CD68+CD206+. This result suggests that infiltrating macrophages in the lung are donor-derived M2 macrophages. (G) Macrophage migration was assessed in a transwell assay. IL-17A or MCP-1was used as a chemoattractant to induce migration. Pirfenidone (0.25 or 0.5 mg/mL) or vehicle was added to cell culture medium and migration medium. Pirfenidone inhibited IL-17A and MCP-1 induced J774 migration. Five to 8 mice were analyzed for each group in each assay. Results are representative of at least 2 experiments with similar results. Migration assay result is representative of 3 experiments with similar results. *P ≤ .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001; data are shown as the mean ± SEM.

Pirfendone reduces F4/80+macrophage accumulation and TGF-β deposition in lung. (A-C) Serial sections of lungs harvested on day 56 post-transplantation were stained with trichrome staining (A, top panels), anti-F4/80 antibody (A, middle panels), and anti–TGF-β antibody (A, bottom panels). F4/80-positive cell number and TGF-β staining area were quantified in (B) and (C). Pirfenidone reduced macrophages infiltration and TGF-β production in lung. (D-E) Mice were transplanted as described in Figure 1. cGVHD mice were treated by pirfenidone for a week from days 28 to 35. On day 35, LAP expression in alveolar macrophages (D) and tissue macrophages (E) were analyzed by flow cytometry. Pirfenidone significantly reduced LAP expression in both alveolar and tissue macrophages. (F) Donor B6 mice are CD45.1 and B10.BR CD45.2 recipient mice were used. Lung sections were fixed and stained with anti-CD45.1 (donor marker, red), CD68 (gray), and CD206 (green). Arrows pointed at cells that are CD45.1+CD68+CD206+. This result suggests that infiltrating macrophages in the lung are donor-derived M2 macrophages. (G) Macrophage migration was assessed in a transwell assay. IL-17A or MCP-1was used as a chemoattractant to induce migration. Pirfenidone (0.25 or 0.5 mg/mL) or vehicle was added to cell culture medium and migration medium. Pirfenidone inhibited IL-17A and MCP-1 induced J774 migration. Five to 8 mice were analyzed for each group in each assay. Results are representative of at least 2 experiments with similar results. Migration assay result is representative of 3 experiments with similar results. *P ≤ .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001; data are shown as the mean ± SEM.

To understand whether pirfenidone inhibits TGF-β production from macrophage, cGVHD mice were treated with pirfenidone from day 28 to day 35, and lung cells were analyzed by flow on day 36. Because of the failure of lung perfusion to completely remove blood cells from vasculature,37 thus causing difficulties in discriminating tissue and blood-borne macrophages, we injected CD45 antibody (CD45) IV to label blood-borne macrophages.38 Tissue macrophages are defined as F4/80+CD11c–CD45iv– cells and alveolar macrophages are defined as F4/80+CD11c+ cells39 (supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood Web site). LAP, a protein that is contained in TGF-β precursor at the N-terminus, was quantified for assessment of TGF-β surface expression.40 LAP expression in both alveolar and tissue macrophages was increased significantly in the cGVHD mice, consistent with immunohistochemistry staining as mentioned before, and pirfenidone reduced LAP expression on both alveolar and tissue macrophages (Figure 2D-E). These results suggest that the reduced TGF-β production in lung by pirfenidone was the result of a combined effect of reduced macrophage number and reduced TGF-β–producing capacity of macrophages.

Activated macrophages are generally categorized into classically (M1) and alternatively (M2) activated phenotypes. M2 macrophages are crucial for wound healing, fibrosis, and anti-inflammatory effects, whereas M1 macrophages are more important for pro-inflammatory effects. To determine the phenotype and origin of the infiltrating macrophages in the lung, we used CD45.1 B6 donors and stained the lungs of cGVHD mice with donor marker (CD45.1) and the M2 marker CD206, together with the macrophage marker CD68. Immunofluorescence staining showed that the majority of CD68+ cells are also CD45.1+ and CD206+ (Figure 2F), suggesting that infiltrating macrophages in cGVHD are donor BM–derived M2 phenotype.

Because pirfenidone reduces macrophage infiltration in nephrectomized rats,41 inhibits monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1/CCL2) in a bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis model,23 and reduces macrophage infiltration into the lungs of cGVHD mice, we sought to further evaluate pirfenidone’s effect on macrophage migration. For this purpose, a transwell assay was used. IL-17A and MCP-1 were chosen as chemoattractants42 based on their implications in cGVHD pathogenesis in this43 and other transplant settings.31,44-49 Pirfenidone significantly inhibited both IL-17A and MCP-1–induced J774 macrophages migration in vitro (Figure 2G). Taken together, these results suggest that cGVHD lung disease is mediated by donor M2 macrophage infiltration and excessive TGF-β production, and that pirfenidone not only inhibits IL-17A facilitated macrophage infiltration, but also macrophage TGF-β production. Pirfenidone’s effect on macrophage function and migration is unlikely to affect the GVL response, because recipients of CSF1R−/− grafts that are macrophage-deficient had similar GVL response to recipients of wild-type grafts (supplemental Figure 2).

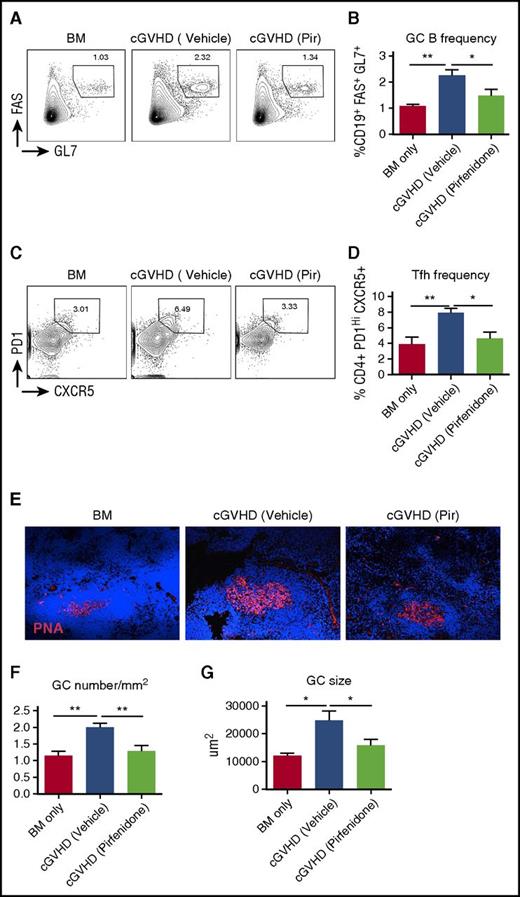

Pirfendone reduces the GC reaction in cGVHD mice

cGVHD pathogenesis in the BO model requires auto/allo antibodies production driven by elevated GC reaction.9,10 Previously, we showed that cGVHD mice develop a spontaneous GC reaction, and disrupting the GC reaction can ameliorate cGVHD in this model.10 To examine whether pirfenidone interferes with this pathologic process, we evaluated the effect of pirfenidone on the GC reaction. Although GCs were significantly upregulated in cGVHD mice, as indicated by GC B-cell (Figure 3A-B) and Tfh cell (Figure 3C-D) frequencies, as well as by GC size (Figure 3E-F) and number (Figure 3G), pirfenidone treatment significantly impaired these immunologic effects. These results suggest that pirfenidone inhibits a known driving force of cGVHD pathogenesis.

Pirfendone reduces the GC reaction in cGVHD mice. Spleens were harvested on day 56 post-transplantation. Splenocytes were stained with fluorochrome-labeled antibodies against CD4, CD19, FAS, GL4, CXCR5, and PD1. Fixed spleen sections were stained with GC B-cell marker rhodamine-peanut agglutinin and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. (A-D) Representative flow cytometry plots of GC B cells (FAS+GL7+) (A) and Tfh cells (PD1hiCXCR5+) (C) in splenocytes. Cells were gated on live CD19 cells and CD4 cells, respectively. Quantification of GC B cell and Tfh cell frequency were showed in (B) and (D). Results were pooled from 2 independent experiments with 5 to 8 mice per group. (E) Representative GC immunofluorescence staining images of the spleens. (F) Size of GCs in the spleen. Five to 6 GCs from each mouse were photographed and size was measured. Five to 6 mice from each group were analyzed. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments with similar results. (G) Frequency of GC in the spleen. The number of GCs in each spleen was divided by the size of the spleen section. Five to 6 mice from each group were analyzed. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments with similar results. *P ≤ .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001; data are shown as the mean ± SEM.

Pirfendone reduces the GC reaction in cGVHD mice. Spleens were harvested on day 56 post-transplantation. Splenocytes were stained with fluorochrome-labeled antibodies against CD4, CD19, FAS, GL4, CXCR5, and PD1. Fixed spleen sections were stained with GC B-cell marker rhodamine-peanut agglutinin and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. (A-D) Representative flow cytometry plots of GC B cells (FAS+GL7+) (A) and Tfh cells (PD1hiCXCR5+) (C) in splenocytes. Cells were gated on live CD19 cells and CD4 cells, respectively. Quantification of GC B cell and Tfh cell frequency were showed in (B) and (D). Results were pooled from 2 independent experiments with 5 to 8 mice per group. (E) Representative GC immunofluorescence staining images of the spleens. (F) Size of GCs in the spleen. Five to 6 GCs from each mouse were photographed and size was measured. Five to 6 mice from each group were analyzed. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments with similar results. (G) Frequency of GC in the spleen. The number of GCs in each spleen was divided by the size of the spleen section. Five to 6 mice from each group were analyzed. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments with similar results. *P ≤ .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001; data are shown as the mean ± SEM.

To assess whether pirfenidone could directly affect the GC reaction in a non-cGVHD setting, we used a sheep red blood cell (SRBC) immunization model. Mice were immunized with SRBC to induce GC reactions on day 0. In the pirfenidone treatment group, mice were treated with pirfenidone from day-1 to day 6. On day 7, spleens and serum were harvested for GC reaction evaluation and SRBC antibody detection. Interestingly, pirfenidone did not affect the magnitude of the SRBC-induced GC reaction, as indicated by comparable frequencies of GC B cells, Tfhs, and antibody response in pirfenidone-treated and vehicle-treated groups (supplemental Figure 3). These results suggest that pirfenidone interferes with cGVHD-specific antigen responses or the amplification of such responses that lead to the GC reaction rather than by globally suppressing GC formation in response to a potent GC-inducing stimulus such as SRBCs.

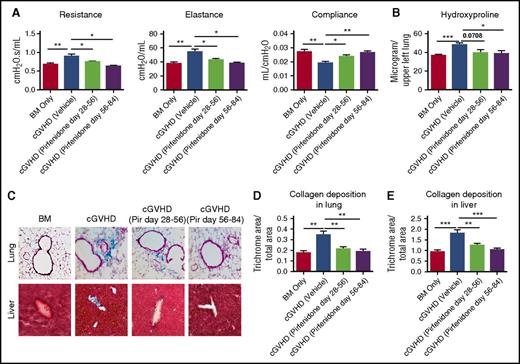

Pirfenidone treatment has a long-lasting effect and is capable of reducing later stage disease

To determine whether pirfenidone inhibition of pulmonary fibrosis was transient, transplanted mice were treated with pirfenidone days 28 to 56 after transplantation and were left untreated for 28 days before pulmonary function tests were performed. Pulmonary function of treated mice on day 84 was still significantly better than mice that never received treatment, although not reaching the levels of BM-only mice (Figure 4A). Thus, pirfenidone has a long-lasting effect on cGVHD fibrosis.

Pirfenidone treatment results in long-lasting effects and is able to reduce later-stage disease. Mice were transplanted as in Figure 1. Mice were untreated or treated, as indicated, with pirfenidone from days 28 to 56 or days 56 to 84. All mice were evaluated on day 84. (A) Pulmonary function tests on day 84 showed that pirfenidone effects were significant even 4 weeks after treatment cessation. In addition, pirfenidone treatment was effective even when treatment started at late stage (day 56) of the disease. (B) Hydroxyproline assay correlated with pulmonary function test result. (C) Masson’s trichrome staining of lung and liver. (D-E) Quantification of trichrome staining area in the lung and liver. Five to 8 mice were analyzed for each assay. *P ≤ .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001; data are shown as the mean ± SEM.

Pirfenidone treatment results in long-lasting effects and is able to reduce later-stage disease. Mice were transplanted as in Figure 1. Mice were untreated or treated, as indicated, with pirfenidone from days 28 to 56 or days 56 to 84. All mice were evaluated on day 84. (A) Pulmonary function tests on day 84 showed that pirfenidone effects were significant even 4 weeks after treatment cessation. In addition, pirfenidone treatment was effective even when treatment started at late stage (day 56) of the disease. (B) Hydroxyproline assay correlated with pulmonary function test result. (C) Masson’s trichrome staining of lung and liver. (D-E) Quantification of trichrome staining area in the lung and liver. Five to 8 mice were analyzed for each assay. *P ≤ .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001; data are shown as the mean ± SEM.

To evaluate the efficacy of pirfenidone in a late stage of cGVHD, transplanted mice were treated from day 56 to day 84 after transplantation. Day 84 pulmonary function tests indicated that pirfenidone reduced lung disease even at this later stage of the disease process (Figure 4A). Hydroxyproline assay (Figure 4B) and trichrome staining (Figure 4C-E) correlated with pulmonary function test results. Taken together, these results provide a foundation for consideration of the future testing of pirfenidone treatment in cGVHD patient.

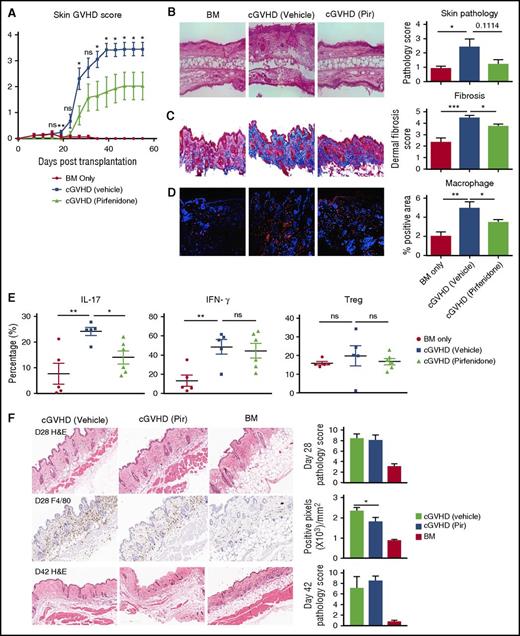

Pirfenidone treatment has variable efficacy in the scleroderma models

To examine whether pirfenidone can also attenuate skin fibrosis, we used 2 different skin cGVHD models. In the minor histocompatibility antigen-mismatched B10.D2 to BALB/c model, dermal fibrosis is dependent on both Th1 and Th17 CD4+ T cells12 and preceded by infiltration of donor-derived CD11b+ cells consisting of monocytes and activated macrophages.50 Clinical skin disease in this model develops on about day 20 after transplantation,28 thus pirfenidone treatment was started on day 21 when clinical disease is already established in the majority of animals. Pirfenidone reduced skin lesions (Figure 5A-B). Although the profoundness of pirfenidone’s effects on the skin scores varied between the experiments, the drug effect on the reduction of collagen deposition and macrophage infiltration in cGVHD mice was consistently observed (Figure 5C-D). In addition, pirfenidone significantly reduced the percentage of IL-17a-producing CD4+ T cells but did not alter percentage of IFN-γ producing cells. Pirfenidone also did not affect the percentage of Tregs in the spleen (Figure 5E). In addition, studies in which pirfenidone was used to pretreat Tregs in an in vitro suppression assay showed that pirfenidone did not alter Treg suppressive function (supplemental Figure 4). In the B6 to B6D2F1 haploidentical transplant model, CSF-1–dependent donor BM-derived M2 macrophage infiltrate the dermis by day 21 post-transplantation. Pirfenidone treatment from days14 to 28 marginally but significantly decreased day 28 macrophage infiltration but this was insufficient to translate to reductions in cutaneous pathology (Figure 5F).

Pirfenidone treatment shows variable efficacy in the scleroderma models. (A-D) BALB/c mice were conditioned with TBI (7 Gy, day 0), followed by infusion of 107 B10.D2 BM only or plus 1.8 × 106 CD4 and 0.9 × 106 CD8 T cells (day 0). In the treatment group, mice were treated with pirfenidone from day 21 to 55. (A) Skin clinical score based on the area of skin lesion. (B) Hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining of the skin (left) and pathology score (right). Pirfenidone reduced both clinical score and pathology score. (C) Trichrome staining of skin. Collagen was stained blue. Fibrosis was scored on a 1 to 5 scale based on the intensity of blue staining. Pirfenidone significantly reduced collagen deposition in skin. (D) Immunofluorescence staining of macrophage in skin samples. CD68 (red) identified macrophages. Pirfenidone significantly reduced macrophage infiltration in skin. (E) Flow cytometry analysis cytokine production and Treg percentage of splenocytes from transplanted mice. (F) B6D2F1 mice were conditioned with TBI (11 Gy split into 2 doses, day 1) followed by infusion of 5 × 106 B6 BM only or plus 1 × 106 purified T cells (day 0). Where indicated, mice were treated with pirfenidone from days14 to 28 or days 14 to 41. HE staining on days 28 (top) and 42 (bottom) and day28 F4/80 staining (middle) indicating that pirfenidone alleviated macrophage infiltration but failed to significantly improve pathologic changes. In each experiment, 5 to 10 mice from each group were tested. *P ≤ .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001; data are shown as the mean ± SEM.

Pirfenidone treatment shows variable efficacy in the scleroderma models. (A-D) BALB/c mice were conditioned with TBI (7 Gy, day 0), followed by infusion of 107 B10.D2 BM only or plus 1.8 × 106 CD4 and 0.9 × 106 CD8 T cells (day 0). In the treatment group, mice were treated with pirfenidone from day 21 to 55. (A) Skin clinical score based on the area of skin lesion. (B) Hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining of the skin (left) and pathology score (right). Pirfenidone reduced both clinical score and pathology score. (C) Trichrome staining of skin. Collagen was stained blue. Fibrosis was scored on a 1 to 5 scale based on the intensity of blue staining. Pirfenidone significantly reduced collagen deposition in skin. (D) Immunofluorescence staining of macrophage in skin samples. CD68 (red) identified macrophages. Pirfenidone significantly reduced macrophage infiltration in skin. (E) Flow cytometry analysis cytokine production and Treg percentage of splenocytes from transplanted mice. (F) B6D2F1 mice were conditioned with TBI (11 Gy split into 2 doses, day 1) followed by infusion of 5 × 106 B6 BM only or plus 1 × 106 purified T cells (day 0). Where indicated, mice were treated with pirfenidone from days14 to 28 or days 14 to 41. HE staining on days 28 (top) and 42 (bottom) and day28 F4/80 staining (middle) indicating that pirfenidone alleviated macrophage infiltration but failed to significantly improve pathologic changes. In each experiment, 5 to 10 mice from each group were tested. *P ≤ .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001; data are shown as the mean ± SEM.

Discussion

cGVHD patients have manifestations that are similar to fibrotic diseases such as systemic sclerosis and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.51 Thus, antifibrosis treatments may offer a novel therapeutic approach for cGVHD patients. However, there is no antifibrosis drug available for cGVHD patients. Here, we demonstrated the efficacy of pirfenidone, an FDA-approved drug for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, in reversing fibrosis in the multiorgan system, a BO cGVHD model previously demonstrated to mimic several aspects of human cGVHD, with the exception of sclerodermatous cGVHD.9 Pulmonary function and pathologic changes in the cGVHD lung were normalized by pirfenidone when treatment was begun at 1 month post-transplant, while improving but not completing reversing disease when delayed an additional month to day 56 post-transplant. These results extend other studies showing that pirfenidone can reduce lung fibrosis in bleomycin and lung allograft rodent models.20,21,23,52 The protective effect of pirfenidone is associated with a decrease of infiltrating macrophages surrounding the bronchioles and a decrease of TGF-β production by these macrophages. Because BO is also a major problem in lung transplantation, the current finding in the BO cGVHD model may also shed light on the management of lung transplantation complications.

Pirfenidone is a small molecule that is rapidly absorbed and metabolized into 5-carboxy-pirfenidone, whose antifibrotic effect is weaker than that of pirfenidone.53 Pirfenidone’s pharmacokinetics and metabolism profile have be characterized by Buckpitt et al,54 showing that after administration, the peak level of pirfenidone in tissues correlates with the degree of tissue penetration. Whereas pirfenidone alleviated skin fibrosis in 2 clinical trials for localized scleroderma and burn injury,26,55 in both scleroderma models tested here, pirfenidone had a variable and modest effect under the conditions tested, although a significant reduction in macrophage infiltration was observed in both models. We hypothesize that the relative modest or absence of effect of pirfenidone on skin manifestations is because that skin is not perfused as well as other organs where pirfenidone has a more evident effect such as lung and liver. In addition, rapid onset of skin scarring may further limit the access of pirfenidone to its target sites. Thus, topical treatment that may increase tissue penetration in scleroderma cGVHD models warrants testing in the future.

The cGVHD BO model depends on antigen-activated GC reactions that result in antibody deposition in multiple organs including lung and liver that trigger profibrotic responses. This feature of the BO model mimic human cGVHD, because autoreactive antibodies have been identified in cGVHD patients.56 In addition, antibodies against Y-chromosome–encoded antigens have been identified in male patients transplanted with BM from female donors.57 Although as discussed before, pirfenidone is well known for its antifibrosis ability, pirfenidone also has been reported to suppress allo-responses.58 By using a cGVHD independent SRBC immunization model, we showed that pirfenidone does not directly regulate GC reactions because pirfenidone-treated mice still developed strong GC responses against SRBC immunization. Rather than a direct effect of pirfenidone on the GC reaction, pirfenidone may be influencing the GC response via macrophages that are known to be required for cGVHD in the BO cGVHD model.11 These data pointed to the capacity of pirfenidone to modify the particular antigen-driven response for cGVHD generation and maintenance. Wilkes and colleagues have shown that IL-17–dependent immune responses against collagen V contribute to BO in preclinical and clinical lung transplant settings.59-61 In rheumatoid arthritis, immune responses against collagen also may contribute to disease. Because collagen content is significantly increased in cGVHD mice and reduced by pirfenidone treatment, we hypothesize that pirfenidone may be ameliorating disease by reducing IL-17A–facilitated macrophage infiltration, macrophage TGF-β production, and hence, collagen production,42 especially based on its implication in cGVHD pathogenesis in this43 and other cGVHD settings.45-49 Consistent with this hypothesis, we directly demonstrate that pirfenidone impedes macrophage migration to IL-17A in vitro and lung macrophage infiltration in a cGVHD system that depends on IL-17A for disease generation.43 Pirfenidone also impaired macrophage migration to MCP-1/CCL2. Although in sclerodermatous cGVHD, some studies have shown MCP-1 to be upregulated62 with biological responses to pravastatin treatment associated with MCP-1 downregulation,63 in another model [B6 parent→B6D2F11 ], MCP-1 affected neither the development nor the inflammatory response. Interestingly, the latter model did not have a robust clinical effect in response to pirfenidone treatment. In contrast, high MCP-1 levels have been associated with the pathogenesis of BO,64 and in the BO cGVHD model here, pirfenidone was highly effective in treating disease, which was associated with reduced macrophage infiltration in the lung. B cells in cGVHD patients are in a more active state given the increased B cell–activating factor/B-cell ratio after transplantation.1 In this scenario, excessive collagen can be recognized by hyper-responsive B cells, resulting in the production of autoantigen that then triggers the GC response in cGVHD recipients. Thus, the reversal of GVHD observed with pirfenidone treatment may also be attributed to the reduction of collagen as an autoantigen. Understanding the mechanism of action for this effect requires further experimentation.

In conclusion, we identify here the utility of pirfenidone in treating BO cGVHD in a mouse model by reducing macrophage infiltration and TGF-β in cGVHD target organs, including the lung and the skin. Our studies add to the existing evidences of pirfenidone’s antifibrosis efficacy and provide a rationale for the consideration of future clinical trials for pirfenidone as cGVHD therapy in patients, particularly those that have BO, a devastating complication of allo-HSCT.27

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Steven W. Lane for generating the GVL model.

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute grants P01 CA142106-06A1, R01CA122779, and 5P01-CA047741-20; National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grants R01 HL126530 and K08HL107756; National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases grants P01 AI 056299, R01 AI 091627, and T32 AI 007313; and Leukemia and Lymphoma Society translational research grants 6458-15 and 6462-15.

Authorship

Contribution: J.D. designed experiments, performed experiments, and wrote the paper; K.P., R.F., A.V., T.M.R., K.E.L., K.A.A., J.M., and M.L. designed and performed experiments; A.P.-M. performed histologic analyses, discussed experimental design, and edited the paper; G.R.H., J.S.S., I.M., D.M., J.K., C.S.C., J.H.A., and J.R. designed experiments and edited the paper; T.W.S. provided reagents, discussed experiments, and edited the paper; and S.R., K.P.M., L.L., and B.R.B. designed experiments and edited the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Bruce R. Blazar, MMC 109, University of Minnesota, 420 Delaware St SE, Minneapolis, MN 55455; e-mail: blaza001@umn.edu.

![Figure 1. Therapeutic administration of pirfenidone reverses fibrosis in cGVHD BO model. B10.BR mice were conditioned with cytoxan (120 mg/kg/day, intraperitoneally [IP], day-3 and day-2) and TBI (8.3 Gy, day-1), followed by infusion of 107 B6 T cell–depleted bone marrow only as healthy control, or plus 75 000 purified splenic T cells to induce cGVHD (day 0). In the treatment group, cGVHD mice received pirfenidone (400 mg/kg) from day 28 to day 56. (A) Pulmonary function tests on day 56 post-transplantation showed that pirfenidone restored lung function of cGVHD mice. Data are representative of 3 experiments with similar results. (B) Hydroxyproline assay of the right lungs harvested on day 56 indicated that pirfenidone significantly reduced hydroxyproline content. Five to 6 mice from each group were analyzed. Data are representative of 2 experiments with similar results. (C) Representative images of Masson’s trichrome staining images of lung (upper) and liver (lower). Collagen (blue stain) was quantified in (D) and (E). (F-G) Representative lung immunoglobulin deposition images and quantification. Data are representative of 2 experiments with similar results. *P ≤ .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001; data are shown as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/129/18/10.1182_blood-2017-01-758854/7/m_blood758854f1.jpeg?Expires=1771046448&Signature=LSmRutyk7zqn6zdAhYYr6~0zoD2votqowwYDjRUZzGecsJCV8ZZG9DNQIROTBFvlk-3QW0xm~QQ3eRTcHlhtveU4XoagqvO8ul5XrqEkR6aQqJWcoU2ptGgq9agUdrucZRwgDeVco2sDtG9LDXsaQK5oaD1HjBuWRrAVh-dz~bONdAEHCqnH2mgUWQOXjtm0yiaJBKYYu~EZwi-fJCTv2SscjE6Ot4imnYGg-1yz61YjLg7OzSF8AnqSY3TkJCiTWnzt06pmy-srvw3Yzj1QpsqVf00MWqIngfu~QSi-VcnRTXMK3aLO1cHxpNtKgk2EVUy4PocerK7XlkneyNqNXQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal