Key Points

Compared with other SCID entities, patients with RD have an earlier presentation with bacterial rather than opportunistic infections.

Myeloablative agents before transplantation support reliable myeloid engraftment and long-term cure in patients with RD.

Abstract

Reticular dysgenesis (RD) is a rare congenital disorder defined clinically by the combination of severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID), agranulocytosis, and sensorineural deafness. Mutations in the gene encoding adenylate kinase 2 were identified to cause the disorder. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is the only option to cure this otherwise fatal disease. Retrospective data on clinical presentation, genetics, and outcome of HSCT were collected from centers in Europe, Asia, and North America for a total of 32 patients born between 1982 and 2011. Age at presentation was <4 weeks in 30 of 32 patients (94%). Grafts originated from mismatched family donors in 17 patients (55%), from matched family donors in 6 patients (19%), and from unrelated marrow or umbilical cord blood donors in 8 patients (26%). Thirteen patients received secondary or tertiary transplants. After transplantation, 21 of 31 patients were reported alive at a mean follow-up of 7.9 years (range: 0.6-23.6 years). All patients who died beyond 6 months after HSCT had persistent or recurrent agranulocytosis due to failure of donor myeloid engraftment. In the absence of conditioning, HSCT was ineffective to overcome agranulocytosis, and inclusion of myeloablative components in the conditioning regimens was required to achieve stable lymphomyeloid engraftment. In comparison with other SCID entities, considerable differences were noted regarding age at presentation, onset, and type of infectious complications, as well as the requirement of conditioning prior to HSCT. Although long-term survival is possible in the presence of mixed chimerism, high-level donor myeloid engraftment should be targeted to avoid posttransplant neutropenia.

Introduction

In 1959, De Vaal and Seynhaeve1 suggested the term “reticular dysgenesia” (RD) for a condition that they observed in newborn boy twins who had neither lymphocytes nor granulocytes in the peripheral blood and who both died within the first week of life from suspected bacterial infections. Lymph nodes, spleen, and thymus were devoid of lymphocytes, and the bone marrow showed a failure of myeloid maturation with a developmental arrest at the promyelocytic stage. With reticular cells being abundantly present in these tissues, the authors hypothesized that the disease originated from a failure of a “multipotent primitive reticular cell” to “develop into the mother cells of the myeloid series, or into lymphocytes and monocytes.” With a proportion of <2%, RD is a very rare SCID entity, and since its first description, ∼20 patients have been reported in small series or in single case reports.2 Besides the typical combination of T–B–NK– SCID and agranulocytosis, patients with RD were noted to suffer from a profound sensorineural hearing deficit.3 Early hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) was described as the only curative therapeutic option for this condition.3-6 In 2009, mutations in the gene encoding adenylate kinase 2 (AK2) were identified as the molecular basis of the disease by 2 independent groups.7,8 Adenylate kinases are phosphotransferases that are involved in intracellular energy transport by providing a shuttle system for high-energy phosphorylated adenine nucleotides. AK2 is a protein involved in the energy transfer in the mitochondrial intermembrane space that catalyzes the reaction ATP (adenosine triphosphate) + AMP (adenosine monophosphate) ⇌ 2ADP (adenosine diphosphate).

Patients with RD develop life-threatening infections very early in life, usually within the first days after birth. Immediate diagnosis and decisive therapeutic interventions are mandatory to offer a curative option in this otherwise fatal disease.

This survey was performed to comprehensively collect data on clinical presentation, transplantation, and outcome to create an objective basis for therapeutic decisions in this very rare disease.

Patients and methods

Patient data were collected in an international survey between November 2010 and November 2015. Participating centers were recruited from repeat presentations of the project in annual meetings of the Inborn Errors Working Party of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation as well as the biannual meetings of the European Society for Immunodeficiency. In addition, major transplant centers in North America were contacted directly. Criteria to be included in the study were diagnostic findings consistent with severe combined immunodeficiency in combination with primary agranulocytosis. A questionnaire was completed by participating centers. Furthermore, if not already done, sequencing of AK2 was offered at the Institute for Clinical Transfusion Medicine and Immunogenetics Ulm (Ulm, Germany). Written informed consent was obtained from all families according to the regulations of local review boards.

Graft failure was defined as a situation in which neutrophil counts remained <500/µL after transplantation (primary) or fell below this threshold after initial recovery (secondary) irrespective of donor T-cell engraftment. Retransplantation included either an additional transplant procedure with conditioning or a change in the donor. A stem cell transfusion from the same donor and without chemotherapy was not defined as a repeat transplantation, but as a boost.

Chimerism analysis included phenotypic (HLA flow cytometry, red blood cell flow cytometry, and XY-FISH analysis) and genetic (STR-analysis of full blood or sorted subpopulations) methods.

Statistical analysis of overall survival was performed with a Kaplan-Meier survival analysis with 95% pointwise confidence intervals. Statistical significance of differences in survival of defined groups was tested with a log-rank test. The significance level was set at 5%.

Results

Clinical presentation before HSCT

We received complete data sets of 32 patients originating from 29 independent families who were treated in 15 centers in 11 countries in Europe, Asia, and North America (Table 1). The ratio of boys to girls was 17:15. Premature birth was reported in more than one-third of patients with neonatal data available (11 of 29; 38%) and almost two-thirds of patients (18 of 29; 62%) were found to be small for gestational age.

Clinical presentation of 32 patients with RD

| Patient No. . | Year of birth . | Sex . | Gestational age, wk . | Weight at birth, g . | Percentile . | Age at presentation, d . | Infection/problem at presentation . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2006 | F | 31 | 930 | 3-10 | 1 | Neonatal sepsis (Calbicans), died before HSCT |

| 2 | 1988 | F | 33 | 1150 | <3 | 1 | Neonatal sepsis |

| 3 | 2011 | F | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. | 4 | Diarrhea |

| 4 | 2008 | M | 27 | 1135 | 75-90 | 1 | Neonatal sepsis (S epidermidis) |

| 5 | 2008 | M | 37 | 2270 | <3 | 19 | Neonatal sepsis (S aureus) |

| 6 | 2010 | M | 40 | 3000 | 10-25 | 53 | Chronic otomastoiditis (K pneumoniae, S aureus) |

| 7 | 2011 | M | 39 | 2470 | <3 | 3 | Neonatal sepsis |

| 8 | 2005 | F | 36 | 2515 | 25-50 | 16 | Fever, weight loss |

| 9 | 2005 | F | 37 | 2400 | 3-10 | 1 | Neonatal sepsis (S agalactiae) |

| 10 | 2003 | M | 36 | 1910 | <3 | 2 | Mild respiratory distress, abdominal distension |

| 11 | 2004 | F | 33 | 1100 | <3 | 7 | Neonatal sepsis |

| 12 | 2006 | M | 39 | 2616 | <3 | 7 | Neonatal sepsis |

| 13 | 2007 | F | 39 | 2900 | 10-25 | 5 | Omphalitis, pneumatosis intestinalis |

| 14 | 2009 | F | 37 | 2000 | <3 | 75 | Whooping cough (B pertussis) |

| 15 | 2011 | M | 39 | 2430 | <3 | 1* | Neonatal sepsis, Omenn syndrome (8 wk) |

| 16 | 1982 | M | 38 | 2400 | <3 | 11 | Neonatal sepsis |

| 17 | 1987 | M | 42 | 2550 | <3 | 1 | Neonatal sepsis, diarrhea, failure to thrive |

| 18 | 1987 | F | 40 | 3684 | 50-75 | 1 | Neonatal sepsis (S viridans), UTI (C albicans) |

| 19 | 1993 | M | 31 | 1870 | 75-90 | 1 | Ascites, hepato/splenomegaly, cholestatic liver disease |

| 20 | 1998 | F | 36 | 2300 | 10-25 | 7 | Neonatal sepsis (E coli), pneumonitis, omphalitis |

| 21 | 1993 | F | 38 | 1310 | <3 | 19 | Neonatal sepsis, omphalitis |

| 22 | 2009 | F | 36 | 2000 | 3-10 | 1* | Neonatal sepsis |

| 23 | 1986 | M | 40 | 2850 | 3-10 | 1 | Neonatal sepsis |

| 24 | 1991 | M | 37 | 2100 | <3 | 1* | No clinical signs or symptoms |

| 25 | 1995 | M | 37 | 1920 | <3 | 1 | Prenatal anemia, neonatal sepsis (P aeruginosa) |

| 26 | 1997 | F | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. | 18 | n.r. |

| 27 | 1999 | M | 36 | 3000 | 50-75 | 7 | Neonatal sepsis (S aureus), omphalitis |

| 28 | 2000 | M | 31 | 1500 | 25-50 | 1 | Ileus due to intestinal dilatation (terminal ileum) of unknown origin |

| 29 | 2000 | F | 37 | 1750 | <3 | 3 | Neonatal sepsis (S aureus) |

| 30 | 2001 | F | 37 | 2770 | 25-50 | 14 | Prenatal anemia |

| 31 | 2002 | M | n.r. | 3350 | n.r. | 7 | Petechiae/thrombocytopenia |

| 32 | 2003 | M | 40 | 3165 | 10-25 | 8 | Omphalitis |

| Patient No. . | Year of birth . | Sex . | Gestational age, wk . | Weight at birth, g . | Percentile . | Age at presentation, d . | Infection/problem at presentation . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2006 | F | 31 | 930 | 3-10 | 1 | Neonatal sepsis (Calbicans), died before HSCT |

| 2 | 1988 | F | 33 | 1150 | <3 | 1 | Neonatal sepsis |

| 3 | 2011 | F | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. | 4 | Diarrhea |

| 4 | 2008 | M | 27 | 1135 | 75-90 | 1 | Neonatal sepsis (S epidermidis) |

| 5 | 2008 | M | 37 | 2270 | <3 | 19 | Neonatal sepsis (S aureus) |

| 6 | 2010 | M | 40 | 3000 | 10-25 | 53 | Chronic otomastoiditis (K pneumoniae, S aureus) |

| 7 | 2011 | M | 39 | 2470 | <3 | 3 | Neonatal sepsis |

| 8 | 2005 | F | 36 | 2515 | 25-50 | 16 | Fever, weight loss |

| 9 | 2005 | F | 37 | 2400 | 3-10 | 1 | Neonatal sepsis (S agalactiae) |

| 10 | 2003 | M | 36 | 1910 | <3 | 2 | Mild respiratory distress, abdominal distension |

| 11 | 2004 | F | 33 | 1100 | <3 | 7 | Neonatal sepsis |

| 12 | 2006 | M | 39 | 2616 | <3 | 7 | Neonatal sepsis |

| 13 | 2007 | F | 39 | 2900 | 10-25 | 5 | Omphalitis, pneumatosis intestinalis |

| 14 | 2009 | F | 37 | 2000 | <3 | 75 | Whooping cough (B pertussis) |

| 15 | 2011 | M | 39 | 2430 | <3 | 1* | Neonatal sepsis, Omenn syndrome (8 wk) |

| 16 | 1982 | M | 38 | 2400 | <3 | 11 | Neonatal sepsis |

| 17 | 1987 | M | 42 | 2550 | <3 | 1 | Neonatal sepsis, diarrhea, failure to thrive |

| 18 | 1987 | F | 40 | 3684 | 50-75 | 1 | Neonatal sepsis (S viridans), UTI (C albicans) |

| 19 | 1993 | M | 31 | 1870 | 75-90 | 1 | Ascites, hepato/splenomegaly, cholestatic liver disease |

| 20 | 1998 | F | 36 | 2300 | 10-25 | 7 | Neonatal sepsis (E coli), pneumonitis, omphalitis |

| 21 | 1993 | F | 38 | 1310 | <3 | 19 | Neonatal sepsis, omphalitis |

| 22 | 2009 | F | 36 | 2000 | 3-10 | 1* | Neonatal sepsis |

| 23 | 1986 | M | 40 | 2850 | 3-10 | 1 | Neonatal sepsis |

| 24 | 1991 | M | 37 | 2100 | <3 | 1* | No clinical signs or symptoms |

| 25 | 1995 | M | 37 | 1920 | <3 | 1 | Prenatal anemia, neonatal sepsis (P aeruginosa) |

| 26 | 1997 | F | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. | 18 | n.r. |

| 27 | 1999 | M | 36 | 3000 | 50-75 | 7 | Neonatal sepsis (S aureus), omphalitis |

| 28 | 2000 | M | 31 | 1500 | 25-50 | 1 | Ileus due to intestinal dilatation (terminal ileum) of unknown origin |

| 29 | 2000 | F | 37 | 1750 | <3 | 3 | Neonatal sepsis (S aureus) |

| 30 | 2001 | F | 37 | 2770 | 25-50 | 14 | Prenatal anemia |

| 31 | 2002 | M | n.r. | 3350 | n.r. | 7 | Petechiae/thrombocytopenia |

| 32 | 2003 | M | 40 | 3165 | 10-25 | 8 | Omphalitis |

F, female; M, male; n.r., not reported; perc., percentile; UTI, urinary tract infection.

Positive family history with diagnosis immediately after birth.

Three patients with a positive family history of RD were identified with lymphopenia and agranulocytosis at birth. Two of these 3 patients developed bacterial sepsis despite the early diagnosis. Bacterial sepsis was the most frequent infectious complication and developed in 17 of the remaining 29 patients (59%), followed by omphalitis (5/29; 17%). The infections present at diagnosis in the remaining patients are given in Table 1. One patient (patient 15) developed the typical features of Omenn syndrome (ie, generalized erythrodermia, lymphadenopathy, and diarrhea) and lymphocytosis due to an oligoclonal expansion of T cells at the age of 8 weeks.9

Infectious agents were isolated from blood cultures in 9 of 19 patients presenting with clinical signs of sepsis and included Staphylococcus aureus in 3 patients and group B Streptococci, Staphylococcus epidermidis, Escherichia coli, Streptococcus viridans, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Candida albicans in 1 patient, respectively. Noninvasive candidiasis was reported in 2 infants. The age at presentation was within the first month in 27 of 29 patients (93%), and in 20 of these 27 cases it was within the first week of life. The 2 late-presenting patients (patients 6 and 14) were diagnosed at the age of 2.5 months with whooping cough and positive polymerase chain reaction for Bordetella pertussis in the nasopharyngeal aspirate, the other at the age of 1.8 months with a history of recurrent otitis (Klebsiella pneumoniae and S aureus).

Laboratory findings at presentation

All patients presented with lymphopenia and with persistent agranulocytosis (Table 2; supplemental Figures 1-8, available on the Blood Web site). T-cell numbers were below normal limits in all patients.10 Maternal T cells were detected in 13 of 23 patients tested (57%), and an exanthema consistent with an alloreaction was present in 4 of those 13 patients (31%). Natural killer (NK)-cell and B-cell numbers were within the normal range in just 2 of 24 and 4 of 25 patients tested, respectively.11

Blood count, immunophenotype, geographic origin, consanguinity, and genotype of 32 patients with RD

| Patient No. . | Age at blood analysis, d . | Hemoglobin, g/dL . | Platelet count (×109/mL) . | Neutrophils/µL . | Monocytes/µL . | Lymphocytes/µL . | MFT . | Exanthema . | T cells/ µL . | B cells/ µL . | NK cells/ µL . | Geographic origin . | Parental consanguinity . | Mutation AK2 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 3.7 | 43 | 0 | 40 | 60 | + | – | 50 | 6 | 6 | Turkish | + | c.[498+1G>A];[498+1G>A]; p.[?];[?] |

| 2 | 10 | 11.5 | 101 | 0 | 15 | 0 | – | – | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | Turkish | + | c.[453delC];[453delC]; p.[Tyr152Thrfs*12];[Tyr152Thrfs*12] |

| 3 | 4 | 13.1 | 82 | 0 | 0 | 200 | n.r. | – | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | Japanese | n.r. | c.[409C>T];[307C>T]; p.[Arg137*];[Arg103Trp] |

| 4 | 120 | 10.7 | 410 | 60 | 40 | 480 | + | + | 150 | 280 | 60 | Arabic | – | c.[524G>C];[524G>C]; p.[Arg175Pro];[Arg175Pro] |

| 5 | 21 | 15.6 | 62 | 6 | 30 | 564 | – | – | 59 | 255 | 288 | Italian | n.r. | c.[94-?_219+?del];[94-?_219+?del]; p.[?];[?] |

| 6 | 53 | 9.6 | 806 | 70 | 0 | 900 | + | – | 233 | 1842 | 204 | Arabic | + | c.[524G>A];[524G>A]; p.[Arg175Gln];[Arg175Gln] |

| 7 | 2 | 11.6 | 425 | 0 | 20 | 100 | + | – | 25 | 54 | 3 | Turkish | + | c.[453del];[453del]; p.[Tyr152Thrfs*12];[Tyr152Thrfs*12] |

| 8 | 39 | 11.0 | 1201 | 40 | 7 | 440 | – | – | 10 | 221 | 69 | Italian | n.r. | c.[229G>A];?; p.[Gly100Asp];? |

| 9 | 133 | 8.8 | 38 | 0 | 200 | 80 | n.r. | – | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | Arabic | + | c.[524G>A];[524G>A]; p.[Arg175Gln];[Arg175Gln] |

| 10 | 2 | 13.6 | 150 | 30 | 110 | 390 | n.r. | – | 19 | 175 | 36 | Caucasian | – | c.[636_*2601del];[636_*2601del]; p.[Ser213Aspfs*21];[Ser213Aspfs*21] |

| 11 | 32 | 10.8 | 112 | 40 | 10 | 30 | – | – | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | Caucasian | – | c.[633del5kb];[633del5kb]; p.[Lys233*];[Lys233*] |

| 12 | 1 | 15.8 | 304 | 6 | 92 | 102 | n.r. | – | 13 | 114 | 19 | Japanese | n.r. | c.[139G>C];[ 409C>T]; p.[Gly47Arg];[Arg137*] |

| 13 | 5 | 14.6 | 200 | 13 | 34 | 323 | + | + | 22 | 310 | 35 | United States, Hispanic | + | c.[25G>T];[25G>T]; p.[Glu9*];[Glu9*] |

| 14 | 75 | 8.5 | 1069 | 443 | 65 | 2790 | – | – | 404 | 2495 | 58 | Caucasian | + | c.[1A>T];[1A>T]; p.[?];[?] |

| 15 | 48 | 8.0 | 1111 | 0 | 34 | 3160 | – | + | 1918 | 703 | 36 | Arabic | + | c.[524G>A];[524G>A]; p.[Arg175Gln];[Arg175Gln] |

| 16 | 11 | 18.1 | 204 | 30 | 10 | 200 | + | + | 200 | 0 | 0 | German | – | n.d. |

| 17 | 2 | 17.3 | 30 | 42 | 300 | 1850 | + | – | 255 | 13 | 0 | German | – | c.[636_*2601del];[636_*2601del]; p.[Ser213Aspfs*21];[Ser213Aspfs*21] |

| 18 | 36 | 14.9 | 101 | 0 | 0 | 0 | n.r. | – | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. | USA, Hispanic | n.r. | n.d. |

| 19 | 1 | 8.7 | 28 | 0 | 10 | 190 | + | – | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | German | – | c.[118delT];[1A>G]; p.[Cys40Valfs*5];[Met1Val] |

| 20 | 199 | 9 | 23 | 150 | 400 | 700 | – | – | 100 | 500 | 50 | Portugese | – | c.[307C>T];[307C>T]; p.[Arg103Trp];[Arg103Trp] |

| 21 | 19 | 8.6 | 330 | 30 | 10 | 40 | n.r. | – | 0 | n.d. | n.d. | United States (white/ non-Hispanic) | n.r. | c.[614-615del];[614-615del]; p.[Gly205Aspfs*92];[Gly205Aspfs*92] |

| 22 | 1 | 5.8 | 41 | 0 | 0 | 100 | + | – | 100 | 0 | 0 | Turkish | + | c.[498+1G>A];[498+1G>A]; p.[?];[?] |

| 23 | 1 | 16.4 | 104 | 0 | 0 | 500 | + | + | 100 | 60 | 100 | German | – | c.[94-2287_219+542del2956];[94-2287_219+542del2956]; p.[Ala32_Leu73del];[Ala32_Leu73del] |

| 24 | 2 | 18.3 | 126 | 0 | 12 | 150 | + | – | 5 | 15 | 8 | Turkish | + | c.[453delC];[453delC]; p.[Tyr152Thrfs*12];[Tyr152Thrfs*12] |

| 25 | 1 | 8 | n.d. | 0 | 200 | 300 | n.r. | – | 270 | 0 | 17 | Cape Verde | + | c.[494A>G];[494A>G]; p.[Asp165Gly];[Asp165Gly] |

| 26 | 17 | 15 | 442 | 150 | 550 | 900 | – | – | 90 | 0 | 90 | French | – | c.[556C>T];[94_219del]; p.[Arg186Cys];[Ala32_Leu73del] |

| 27 | 15 | 14.9 | 296 | 76 | 45 | 207 | – | – | 4 | 14 | 33 | Italian | + | c.[556C>T];[556C>T]; p.[Arg186Cys];[Arg186Cys] |

| 28 | 1 | 15.2 | 460 | 85 | 12 | 940 | + | + | 30 | 22 | 5 | German | + | c.[331-1G>A];[331-1G>A]; p.[?];[?] |

| 29 | 3 | 7.5 | 16 | 0 | 400 | 0 | + | – | 0 | 0 | 0 | Caucasian | – | c.[400-401del];[614-615del]; p.[Leu134Alafs*32];[Gly205Aspfs*29] |

| 30 | 14 | 10 | 100 | 0 | 150 | 260 | – | n.r. | 10 | 165 | 8 | Turkish | + | c.[473del];[473del]; p.[Pro158Leufs*6];[Pro158Leufs*6] |

| 31 | 103 | 15 | 62 | 30 | 555 | 670 | n.r. | n.r. | 70 | 556 | 53 | Cape Verde | + | c.[494A>G];[494A>G]; p.[Asp165Gly];[Asp165Gly] |

| 32 | 8 | 14.3 | 293 | 100 | 200 | 300 | n.r. | – | 2 | 60 | n.d. | Palestinian | + | c.[307C>T];[307C>T]; p.[Arg103Trp];[Arg103Trp] |

| Patient No. . | Age at blood analysis, d . | Hemoglobin, g/dL . | Platelet count (×109/mL) . | Neutrophils/µL . | Monocytes/µL . | Lymphocytes/µL . | MFT . | Exanthema . | T cells/ µL . | B cells/ µL . | NK cells/ µL . | Geographic origin . | Parental consanguinity . | Mutation AK2 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 3.7 | 43 | 0 | 40 | 60 | + | – | 50 | 6 | 6 | Turkish | + | c.[498+1G>A];[498+1G>A]; p.[?];[?] |

| 2 | 10 | 11.5 | 101 | 0 | 15 | 0 | – | – | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | Turkish | + | c.[453delC];[453delC]; p.[Tyr152Thrfs*12];[Tyr152Thrfs*12] |

| 3 | 4 | 13.1 | 82 | 0 | 0 | 200 | n.r. | – | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | Japanese | n.r. | c.[409C>T];[307C>T]; p.[Arg137*];[Arg103Trp] |

| 4 | 120 | 10.7 | 410 | 60 | 40 | 480 | + | + | 150 | 280 | 60 | Arabic | – | c.[524G>C];[524G>C]; p.[Arg175Pro];[Arg175Pro] |

| 5 | 21 | 15.6 | 62 | 6 | 30 | 564 | – | – | 59 | 255 | 288 | Italian | n.r. | c.[94-?_219+?del];[94-?_219+?del]; p.[?];[?] |

| 6 | 53 | 9.6 | 806 | 70 | 0 | 900 | + | – | 233 | 1842 | 204 | Arabic | + | c.[524G>A];[524G>A]; p.[Arg175Gln];[Arg175Gln] |

| 7 | 2 | 11.6 | 425 | 0 | 20 | 100 | + | – | 25 | 54 | 3 | Turkish | + | c.[453del];[453del]; p.[Tyr152Thrfs*12];[Tyr152Thrfs*12] |

| 8 | 39 | 11.0 | 1201 | 40 | 7 | 440 | – | – | 10 | 221 | 69 | Italian | n.r. | c.[229G>A];?; p.[Gly100Asp];? |

| 9 | 133 | 8.8 | 38 | 0 | 200 | 80 | n.r. | – | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | Arabic | + | c.[524G>A];[524G>A]; p.[Arg175Gln];[Arg175Gln] |

| 10 | 2 | 13.6 | 150 | 30 | 110 | 390 | n.r. | – | 19 | 175 | 36 | Caucasian | – | c.[636_*2601del];[636_*2601del]; p.[Ser213Aspfs*21];[Ser213Aspfs*21] |

| 11 | 32 | 10.8 | 112 | 40 | 10 | 30 | – | – | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | Caucasian | – | c.[633del5kb];[633del5kb]; p.[Lys233*];[Lys233*] |

| 12 | 1 | 15.8 | 304 | 6 | 92 | 102 | n.r. | – | 13 | 114 | 19 | Japanese | n.r. | c.[139G>C];[ 409C>T]; p.[Gly47Arg];[Arg137*] |

| 13 | 5 | 14.6 | 200 | 13 | 34 | 323 | + | + | 22 | 310 | 35 | United States, Hispanic | + | c.[25G>T];[25G>T]; p.[Glu9*];[Glu9*] |

| 14 | 75 | 8.5 | 1069 | 443 | 65 | 2790 | – | – | 404 | 2495 | 58 | Caucasian | + | c.[1A>T];[1A>T]; p.[?];[?] |

| 15 | 48 | 8.0 | 1111 | 0 | 34 | 3160 | – | + | 1918 | 703 | 36 | Arabic | + | c.[524G>A];[524G>A]; p.[Arg175Gln];[Arg175Gln] |

| 16 | 11 | 18.1 | 204 | 30 | 10 | 200 | + | + | 200 | 0 | 0 | German | – | n.d. |

| 17 | 2 | 17.3 | 30 | 42 | 300 | 1850 | + | – | 255 | 13 | 0 | German | – | c.[636_*2601del];[636_*2601del]; p.[Ser213Aspfs*21];[Ser213Aspfs*21] |

| 18 | 36 | 14.9 | 101 | 0 | 0 | 0 | n.r. | – | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. | USA, Hispanic | n.r. | n.d. |

| 19 | 1 | 8.7 | 28 | 0 | 10 | 190 | + | – | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | German | – | c.[118delT];[1A>G]; p.[Cys40Valfs*5];[Met1Val] |

| 20 | 199 | 9 | 23 | 150 | 400 | 700 | – | – | 100 | 500 | 50 | Portugese | – | c.[307C>T];[307C>T]; p.[Arg103Trp];[Arg103Trp] |

| 21 | 19 | 8.6 | 330 | 30 | 10 | 40 | n.r. | – | 0 | n.d. | n.d. | United States (white/ non-Hispanic) | n.r. | c.[614-615del];[614-615del]; p.[Gly205Aspfs*92];[Gly205Aspfs*92] |

| 22 | 1 | 5.8 | 41 | 0 | 0 | 100 | + | – | 100 | 0 | 0 | Turkish | + | c.[498+1G>A];[498+1G>A]; p.[?];[?] |

| 23 | 1 | 16.4 | 104 | 0 | 0 | 500 | + | + | 100 | 60 | 100 | German | – | c.[94-2287_219+542del2956];[94-2287_219+542del2956]; p.[Ala32_Leu73del];[Ala32_Leu73del] |

| 24 | 2 | 18.3 | 126 | 0 | 12 | 150 | + | – | 5 | 15 | 8 | Turkish | + | c.[453delC];[453delC]; p.[Tyr152Thrfs*12];[Tyr152Thrfs*12] |

| 25 | 1 | 8 | n.d. | 0 | 200 | 300 | n.r. | – | 270 | 0 | 17 | Cape Verde | + | c.[494A>G];[494A>G]; p.[Asp165Gly];[Asp165Gly] |

| 26 | 17 | 15 | 442 | 150 | 550 | 900 | – | – | 90 | 0 | 90 | French | – | c.[556C>T];[94_219del]; p.[Arg186Cys];[Ala32_Leu73del] |

| 27 | 15 | 14.9 | 296 | 76 | 45 | 207 | – | – | 4 | 14 | 33 | Italian | + | c.[556C>T];[556C>T]; p.[Arg186Cys];[Arg186Cys] |

| 28 | 1 | 15.2 | 460 | 85 | 12 | 940 | + | + | 30 | 22 | 5 | German | + | c.[331-1G>A];[331-1G>A]; p.[?];[?] |

| 29 | 3 | 7.5 | 16 | 0 | 400 | 0 | + | – | 0 | 0 | 0 | Caucasian | – | c.[400-401del];[614-615del]; p.[Leu134Alafs*32];[Gly205Aspfs*29] |

| 30 | 14 | 10 | 100 | 0 | 150 | 260 | – | n.r. | 10 | 165 | 8 | Turkish | + | c.[473del];[473del]; p.[Pro158Leufs*6];[Pro158Leufs*6] |

| 31 | 103 | 15 | 62 | 30 | 555 | 670 | n.r. | n.r. | 70 | 556 | 53 | Cape Verde | + | c.[494A>G];[494A>G]; p.[Asp165Gly];[Asp165Gly] |

| 32 | 8 | 14.3 | 293 | 100 | 200 | 300 | n.r. | – | 2 | 60 | n.d. | Palestinian | + | c.[307C>T];[307C>T]; p.[Arg103Trp];[Arg103Trp] |

Mutations are indicated according to GenBank reference sequences NM_013411.4 for AK2 complementary DNA (isoform B) and NP_037543 for AK2 protein.

MFT, maternofetal transfusion; n.d., not determined; n.r., not reported.

In addition to lymphopenia and agranulocytosis, almost half of the patients exhibited other hematological abnormalities. Hemoglobin levels were below the normal range in 14 of 32 patients (44%).12 In 1 patient (patient 22) an umbilical blood sample was taken for prenatal diagnosis, which revealed a hemoglobin level of 5.8 g/dL and a platelet count of 48 000/µL without clinical signs of anemia. Thrombocytopenia was observed in 14 of 31 (45%) patients.13

Bone marrow aspirates were reported in 26 of 32 patients and revealed hypoplasia in 9 and hyperplasia in 5 of those 26 patients. The most common finding reported in 22 of the 26 patients was an arrest of myeloid differentiation at the promyelocytic stage (Figure 1; supplemental Table 1). In 9 of 26 aspirates, dysmorphic lymphopoiesis was described, which was difficult to distinguish from malignant disease in some cases (Figure 1).

May-Grunwald-Giemsa stain of a bone marrow aspirate from a patient with RD (original magnification ×1000, immersion oil, Zeiss Axio Imager M1, AxioCam MRc [Carl Zeiss Microscopy, Jena, Germany]) showing immature lymphoid cells (hematogones) with slim cytoplasm as well as myeloblasts and a dysplastic promyelocyte with nuclear and cytoplasmic vacuoles. In the work-up of the bone marrow with immunostaining and flow cytometry, immature lymphocytes were identified as polyclonal B-cell precursors (flow cytometry of the bone marrow revealed a population of 46% with markers of pre–B cells CD10+/CD19+/cyIgM+/TdT+/CD34–; clonality was tested in a multiplex polymerase chain reaction for the rearranged B-cell receptor heavy chains [data not shown]).

May-Grunwald-Giemsa stain of a bone marrow aspirate from a patient with RD (original magnification ×1000, immersion oil, Zeiss Axio Imager M1, AxioCam MRc [Carl Zeiss Microscopy, Jena, Germany]) showing immature lymphoid cells (hematogones) with slim cytoplasm as well as myeloblasts and a dysplastic promyelocyte with nuclear and cytoplasmic vacuoles. In the work-up of the bone marrow with immunostaining and flow cytometry, immature lymphocytes were identified as polyclonal B-cell precursors (flow cytometry of the bone marrow revealed a population of 46% with markers of pre–B cells CD10+/CD19+/cyIgM+/TdT+/CD34–; clonality was tested in a multiplex polymerase chain reaction for the rearranged B-cell receptor heavy chains [data not shown]).

AK2 mutations

For 30 patients originating from 27 independent families, 22 different mutations in AK2 were reported. In 2 patients, no material was available to perform retrospective genetic analysis. Mutations in 14 patients (Figure 2 and Table 2) have been previously described.7-9 Deletions (1-5000 nucleotides), missense, nonsense and splice-site mutations were detected in AK2 sequences, leading to in silico predictions of single amino acid missense mutations or premature stop codons with truncated proteins.

Genomic map of AK2 isoform B with mutations identified in 29 patients. GenBank reference sequence NM_013411.4 for AK2 complementary DNA, isoform B. The numbers in brackets indicate the frequency of the mutations and whether they were identified as part of a homozygous mutation (*) or a compound heterozygous mutation (#).

Genomic map of AK2 isoform B with mutations identified in 29 patients. GenBank reference sequence NM_013411.4 for AK2 complementary DNA, isoform B. The numbers in brackets indicate the frequency of the mutations and whether they were identified as part of a homozygous mutation (*) or a compound heterozygous mutation (#).

Of the 23 patients with homozygous mutations, 16 reported a consanguineous background whereas 7 did not. As expected, identical homozygous mutations were found in 3 pairs of siblings (patients 2 and 24, patients 1 and 22, and patients 9 and 15). Common mutations were detected in patients originating from the same (patients 25 and 31 from Cape Verde; patients 2, 24, and 7 from Turkey; and patients 6, 9, and 15 from the Arabic peninsula) as well as from different geographical areas (patients 10 and 17; and patients 20 and 32).

Transplantation

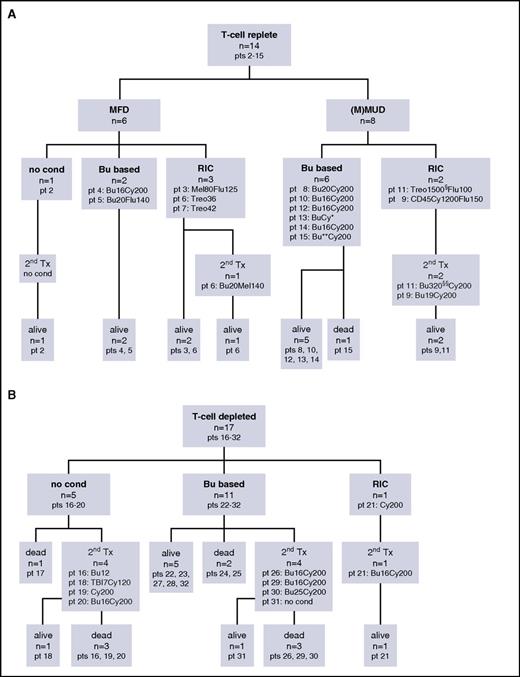

With the exception of 1 patient (patient 1), who died before transplantation from Candida sepsis, the other 31 patients underwent HSCT and received a total of 47 transplantations. The mean age at first HSCT was 3.5 months (range: 0.5-11.1 months; median: 2.4 months). Thirteen patients required a second HSCT either because of engraftment failure without any donor cells detectable (patients 2, 18, 20, 21, and 29) or because of persistence or recurrence of agranulocytosis (patients 6, 9, 11, 16, 19, 26, 30, and 31). Secondary transplants were performed more frequently for patients who received nonmyeloablative conditioning regimens or for those who were transplanted with a T-cell–depleted graft (Figure 3A-B; supplemental Table 2).

Tree diagrams for patient transplantations. (A) Tree diagram for 14 patients transplanted with T-cell–replete grafts. (B) Tree diagram for 17 patients transplanted with T-cell–depleted grafts. ** indicates dosage not reported; *** indicates targeted Bu 800-1200 µmol/min per L; § indicates treosulfan dosage given in mg/kg; §§ indicates busulfan dosage given in mg/m2. Bu, busulfan dosage given in mg/kg; Bu based, conditioning regimen contains busulfan; CD45, anti-CD45 antibody; Cy: cyclophosphamide dosage given in mg/kg; Flu, fludarabine dosage given in mg/m2; Mel, melphalan dose given in mg/m2; MFD, matched family donor; MMUD, mismatched unrelated donor; MUD, matched unrelated donor; no cond, no conditioning; pt, patient; RIC, reduced intensity conditioning; TBI, total body irradiation dosage given in Gy; 2nd Tx, second transplant; Treo, treosulfan dosage given in g/m2.

Tree diagrams for patient transplantations. (A) Tree diagram for 14 patients transplanted with T-cell–replete grafts. (B) Tree diagram for 17 patients transplanted with T-cell–depleted grafts. ** indicates dosage not reported; *** indicates targeted Bu 800-1200 µmol/min per L; § indicates treosulfan dosage given in mg/kg; §§ indicates busulfan dosage given in mg/m2. Bu, busulfan dosage given in mg/kg; Bu based, conditioning regimen contains busulfan; CD45, anti-CD45 antibody; Cy: cyclophosphamide dosage given in mg/kg; Flu, fludarabine dosage given in mg/m2; Mel, melphalan dose given in mg/m2; MFD, matched family donor; MMUD, mismatched unrelated donor; MUD, matched unrelated donor; no cond, no conditioning; pt, patient; RIC, reduced intensity conditioning; TBI, total body irradiation dosage given in Gy; 2nd Tx, second transplant; Treo, treosulfan dosage given in g/m2.

Overall survival (OS) after HSCT was 68% (21 of 31 patients). Seven deaths occurred within the first 6 months after transplantation (patients 15, 16, 17, 20, 24, 25, and 29) and were either related to infections (eg, encephalitis, respiratory infection of unknown origin, pulmonary aspergillosis, and systemic adenovirus infection) or, in 1 patient, severe acute graft-versus-host disease (GvHD) in combination with veno-occlusive disease. Three late deaths at >6 months after transplantation occurred in patients (patients 19, 26, and 30) for whom permanent myeloid engraftment had failed despite the presence of donor lymphocytes (Figure 4; supplemental Table 2).

Kaplan-Meier survival estimation with 95% pointwise confidence intervals. Comparison of the survival probability of patients after HSCT with T-cell replete and T-cell depleted grafts.

Kaplan-Meier survival estimation with 95% pointwise confidence intervals. Comparison of the survival probability of patients after HSCT with T-cell replete and T-cell depleted grafts.

Patients transplanted with T-cell–replete grafts

OS in patients transplanted with T-cell–replete grafts donated from HLA-identical and HLA-mismatched donors was 93% (13 of 14 patients) (Figures 3A and 4; supplemental Table 2).

Six patients had an HLA-identical family donor available, and all of these patients survived. One of these patients achieved long-term cure after 2 transplant attempts without conditioning. In the other 5 patients, conditioning was used. Busulfan-based conditioning was successful in 2 of 2 patients (patients 4 and 5). Alternative regimens used in 3 patients (patients 3, 6, and 7) were sufficient to allow long-term engraftment in 2 of these patients. Patient 7 developed mixed chimerism after conditioning with treosulfan only, but had normal neutrophil counts 2 years after transplantation. Patient 6, in contrast, experienced a gradual recurrence of neutropenia and required a second transplant, which was successful.

Transplants from unrelated donors were used in 8 patients. Overall survival in this group was 88% (7 of 8 patients). In 6 of these 8 patients, unrelated cord blood grafts with variable numbers of mismatches were used (supplemental Table 2). Busulfan-based conditioning was given to 4 of these patients with successful long-term engraftment in all of them (patients 10, 12, 13, and 14). Two patients received alternative conditioning (patients 9 and 11) without long-term myeloid engraftment. Both of these patients developed secondary neutropenia and were successfully retransplanted, receiving a busulfan-based regimen after 2.9 years and 7 months, respectively.

Two patients were transplanted with bone marrow grafts from unrelated adult donors (patients 8 and 15). Both received busulfan-based conditioning. One died of veno-occlusive disease and multiorgan failure,9 whereas the other is alive and well.

Patients transplanted with T-cell–depleted grafts from HLA-haploidentical donors

Seventeen patients (55%) were transplanted with T-cell–depleted grafts from HLA-haplo-identical donors (patients 16-32). OS in this group was 8 out of 17 patients (47%). In 5 patients (patients16-20), the initial HSCT was performed without conditioning and resulted in primary graft failure in all of them. One patient died after the first transplant, and 4 patients received repeat transplants after conditioning 1.2 to 8.4 months after the first HSCT. Among them, only 1 patient (patient 18) survived (Figure 3B; supplemental Table 2).

In 12 of 17 patients, conditioning was used prior to the initial haploidentical HSCT (patients 21-32). In 11 patients, conditioning was based on busulfan, either alone (patient 22) or in combination with cyclophosphamide (patients 23-31) or fludarabine (patient 32). These regimens were successful and led to engraftment and permanent cure in 6 of 11 patients. Two patients died following this procedure, 1 of GvHD (patient 24) and the other of interstitial pneumonia (patient 25). Three patients required a second transplant because of primary (patient 29) or secondary (patients 26 and 30) graft failure. All 3 patients died of adenovirus infection or myelodysplastic syndrome, as detailed elsewhere.14

Conditioning with cyclophosphamide alone in 1 patient (patient 21) was not successful, but engraftment was achieved with retransplantation following conditioning with busulfan and cyclophosphamide 6 weeks later.

GvHD

If GvHD prophylaxis was given, either cyclosporin A (CSA) or tacrolimus was included in all cases (supplemental Table 2). Steroids, methotrexate, or mycophenolate mofetil were given as additional components. Serotherapy prior to HSCT with either antithymocyte globulin or alemtuzumab was used in 16 of 31 first transplants. Following haploidentical T-cell–depleted HSCT, CSA was given to a minority of 4 out of 17 patients (patients19, 28, 29, and 32). The overall incidence of GvHD was 52% (16 of 31 patients), developed de novo after transplantation in 11 of 31 patients (35%), and was preexisting due to engraftment of maternal T cells in 4 of 31 patients (13%). Only 5 patients (16%) developed GvHD of grade III or IV. GvHD was the cause of death in only 1 patient (patient 24).

Lymphohematopoietic reconstitution and long-term follow-up

Twenty-one (66%) of the 31 patients are alive after HSCT (Table 3; supplemental Table 2) with a mean follow-up of 7.9 years (range: 6 months to 23.6 years). No serious or life-threatening infectious problems were reported after HSCT. Regarding growth and development, 10 of 17 patients with data available remained <10th percentile with their body weight, 7 of 16 patients remained <10th percentile with their height, and 4 of 16 patients were reported to have learning disabilities (supplemental Table 3). In a cohort with a high incidence of premature birth, infections, and repetitive exposure to chemotherapy and with the majority (12 of 16 patients) reported to have normal development, it is difficult to characterize developmental delay as a component of RD.

Chimerism and immunological reconstitution in 21 survivors after HSCT

| . | . | Chimerism . | Immunological reconstitution . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient No. . | Follow-up, y . | Full blood, % donor . | T cells, % donor . | Other leukocyte subpopulations, % donor . | Neutrophils/µL . | T cells/µL . | B cells/µL . | NK cells/µL . | Naïve T cells, % . | IVIG . | Specific antibodies . |

| 2 | 23.6 | mixed | 100 | Non–T cells: >90, PMN: >95; CD34+: <10; red blood cells: 6 | 1148 | 1270 | 109 | 109 | 34 | No | Tet/Diph/HiB/Pneu |

| 3 | 7.9 | n.d. | 100 | B cells: 100 | 4100 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | No | n.d. |

| 4 | 3.0 | 100 | n.d. | CD34+: 100 | 1760 | 5350 | 1110 | 490 | 58 | No | Tet/Diph/HiB/MMR |

| 5 | 8.0 | n.d. | 100 | B cells: 90, PMN: 90 | 2410 | 1553 | 263 | 174 | 66 | No | Tet/Diph/HiB/Pneu/MMR |

| 6 | 2.7 | 100 | 100 | PMN: 100 | 1600 | 3620 | 860 | 240 | 54 | No | Tet/Diph/HiB/Pneu |

| 7 | 2.1 | 87 | n.d. | n.d. | 400 | 1138 | 121 | 67 | n.d. | No | n.d. |

| 8 | 11.0 | 100 | 100 | B cells: 100, PMN: 100 | 1780 | 2487 | 324 | 367 | 68 | No | Tet/Diph/HiB/Pneu/MMR |

| 9 | 4.1 | 100 | n.d. | n.d. | 1530 | 1060 | 620 | 70 | 70 | No | Tet/Diph/HiB/Pneu |

| 10 | 7.4 | 100 | 100 | PMN: 99 | 2260 | 3290 | 870 | 786 | 52 | No | Tet/Diph/HiB/Pneu/MMR |

| 11 | 6.5 | 100 | n.d. | n.d. | 2400 | 3000 | 1300 | 807 | n.d. | No | Tet/Diph/HiB/Pneu/MMR |

| 12 | 5.0 | 100 | 100 | B cells: 100; NK cells: 100, PMN: 100 | 1776 | 1520 | 830 | 200 | n.d. | No | MMR |

| 13 | 3.1 | 100 | n.d. | n.d. | 4563 | 2084 | 322 | 275 | 66 | Yes | unknown |

| 14 | 3.4 | n.d. | 96 | B cells: 33, PMN: 75 | 2170 | 1262 | 177 | 397 | n.d. | Yes | n.d. |

| 18 | 1.1 | 100 | n.d. | n.d. | 3000 | 1580 | 200 | 360 | n.d. | Unknown | n.d. |

| 21 | 16.6 | 100 | n.d. | n.d. | 3700 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | No | Tet/Diph |

| 22 | 4.4 | 100 | 100 | n.d. | 2110 | 3410 | 810 | 270 | 51 | No | Tet/Diph/HiB/Pneu |

| 23 | 17.1 | 100 | 100 | red blood cells: 14 | 2960 | 1930 | 210 | 115 | 39 | No | Tet/Diph/HiB/Pneu |

| 27 | 17.0 | n.d. | 100 | B cells: 95, PMN: 100 | 900 | 461 | 77 | 13 | 65 | No | Tet/Diph/HiB/Pneu/MMR |

| 28 | 12.9 | mixed | 100 | CD34+: 80, non–T cells: >95, PMN: 100; red blood cells: 50 | 1672 | 1315 | 307 | 68 | 49 | No | Tet/Diph/HiB/Pneu |

| 31 | 0.6 | 100 | n.d. | n.d. | 3946 | 480 | 70 | 50 | 0 | Yes | n.d. |

| 32 | 9.1 | 100 | n.d. | n.d. | 3400 | 2870 | 350 | 140 | n.d. | No | VZV |

| . | . | Chimerism . | Immunological reconstitution . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient No. . | Follow-up, y . | Full blood, % donor . | T cells, % donor . | Other leukocyte subpopulations, % donor . | Neutrophils/µL . | T cells/µL . | B cells/µL . | NK cells/µL . | Naïve T cells, % . | IVIG . | Specific antibodies . |

| 2 | 23.6 | mixed | 100 | Non–T cells: >90, PMN: >95; CD34+: <10; red blood cells: 6 | 1148 | 1270 | 109 | 109 | 34 | No | Tet/Diph/HiB/Pneu |

| 3 | 7.9 | n.d. | 100 | B cells: 100 | 4100 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | No | n.d. |

| 4 | 3.0 | 100 | n.d. | CD34+: 100 | 1760 | 5350 | 1110 | 490 | 58 | No | Tet/Diph/HiB/MMR |

| 5 | 8.0 | n.d. | 100 | B cells: 90, PMN: 90 | 2410 | 1553 | 263 | 174 | 66 | No | Tet/Diph/HiB/Pneu/MMR |

| 6 | 2.7 | 100 | 100 | PMN: 100 | 1600 | 3620 | 860 | 240 | 54 | No | Tet/Diph/HiB/Pneu |

| 7 | 2.1 | 87 | n.d. | n.d. | 400 | 1138 | 121 | 67 | n.d. | No | n.d. |

| 8 | 11.0 | 100 | 100 | B cells: 100, PMN: 100 | 1780 | 2487 | 324 | 367 | 68 | No | Tet/Diph/HiB/Pneu/MMR |

| 9 | 4.1 | 100 | n.d. | n.d. | 1530 | 1060 | 620 | 70 | 70 | No | Tet/Diph/HiB/Pneu |

| 10 | 7.4 | 100 | 100 | PMN: 99 | 2260 | 3290 | 870 | 786 | 52 | No | Tet/Diph/HiB/Pneu/MMR |

| 11 | 6.5 | 100 | n.d. | n.d. | 2400 | 3000 | 1300 | 807 | n.d. | No | Tet/Diph/HiB/Pneu/MMR |

| 12 | 5.0 | 100 | 100 | B cells: 100; NK cells: 100, PMN: 100 | 1776 | 1520 | 830 | 200 | n.d. | No | MMR |

| 13 | 3.1 | 100 | n.d. | n.d. | 4563 | 2084 | 322 | 275 | 66 | Yes | unknown |

| 14 | 3.4 | n.d. | 96 | B cells: 33, PMN: 75 | 2170 | 1262 | 177 | 397 | n.d. | Yes | n.d. |

| 18 | 1.1 | 100 | n.d. | n.d. | 3000 | 1580 | 200 | 360 | n.d. | Unknown | n.d. |

| 21 | 16.6 | 100 | n.d. | n.d. | 3700 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | No | Tet/Diph |

| 22 | 4.4 | 100 | 100 | n.d. | 2110 | 3410 | 810 | 270 | 51 | No | Tet/Diph/HiB/Pneu |

| 23 | 17.1 | 100 | 100 | red blood cells: 14 | 2960 | 1930 | 210 | 115 | 39 | No | Tet/Diph/HiB/Pneu |

| 27 | 17.0 | n.d. | 100 | B cells: 95, PMN: 100 | 900 | 461 | 77 | 13 | 65 | No | Tet/Diph/HiB/Pneu/MMR |

| 28 | 12.9 | mixed | 100 | CD34+: 80, non–T cells: >95, PMN: 100; red blood cells: 50 | 1672 | 1315 | 307 | 68 | 49 | No | Tet/Diph/HiB/Pneu |

| 31 | 0.6 | 100 | n.d. | n.d. | 3946 | 480 | 70 | 50 | 0 | Yes | n.d. |

| 32 | 9.1 | 100 | n.d. | n.d. | 3400 | 2870 | 350 | 140 | n.d. | No | VZV |

HiB, Haemophilus influenzae type B; Diph, diphtheria; IVIG: IV substitution of immunoglobulins; MMR: measles, mumps, and rubella; n.d., not determined; PMN, polymorphonuclear cell; Pneu, S pneumoniae; Tet, tetanus; VZV, varicella zoster virus.

Mixed chimerism was found in 7 patients (patients 2, 5, 7, 14, 23, 27, and 28). Variable proportions of autologous cells were detected in the lymphoid, erythroid, and/ or myeloid compartment. T cells were of complete donor origin in all but 1 patient (patient 14 with 4% of autologous T cells). For neutrophils, complete donor chimerism was reported in all but 2 patients (patients 5 and 14). Chimerism for B cells was selectively tested in 5 patients (patients 3, 5, 7, 14, and 27) and was found mixed in 3 patients with autologous proportions ranging from 5% to 67%. Chimerism of CD34+ cells was investigated in 3 patients. Autologous CD34+ cells were detected in 2 of 3 patients tested with an autologous proportion of 90% (patient 2) and 20% (patient 28) (Table 4). Red blood cell chimerism was found mixed in 3 patients with an autologous proportion of 50% to 94%.

Diagnostic and therapeutic recommendations for patients with RD

| Diagnosis . | Therapy . |

|---|---|

| Consider RD in any newborn with unexplained neutropenia | Myeloid engraftment is crucial for permanent cure |

| Confirmation by | Myeloid engraftment is supported by |

| Immunophenotyping | Conditioning with myeloablative agents |

| Hearing test | Transplantation with T-cell replete transplants |

| Bone marrow morphology | In case of primary or secondary graft failure, early retransplantation is recommended |

| Genetic analysis of AK2 |

| Diagnosis . | Therapy . |

|---|---|

| Consider RD in any newborn with unexplained neutropenia | Myeloid engraftment is crucial for permanent cure |

| Confirmation by | Myeloid engraftment is supported by |

| Immunophenotyping | Conditioning with myeloablative agents |

| Hearing test | Transplantation with T-cell replete transplants |

| Bone marrow morphology | In case of primary or secondary graft failure, early retransplantation is recommended |

| Genetic analysis of AK2 |

Absolute neutrophil counts <1500/µL were found only in patients with mixed chimerism (patients 2, 7, and 27). T-cell counts were >1000/µL in all patients except 2 (patients 27 and 31), which is explained by a history of GvHD in 1 patient and a short follow-up of 0.5 years in the other. The percentage of naive T cells (here, defined as CD45RA+) was >30% in 12 of 13 analyzed cases, indicating good thymic function and capacity of de novo T-cell formation. Three patients remained on immunoglobulin substitution. All patients tested had positive antibody responses to vaccinations.

Nineteen out of the 21 long-term survivors were reported to suffer from persistent hearing deficiencies and were supported by either conventional hearing aids (n = 10) or cochlear implants (n = 9). For the remaining 2 patients, this information was not available.

Discussion

In this retrospective international study on patients with RD, we have identified a number of particular features with regard to the clinical presentation as well as the therapeutic requirements of the disorder, which are distinct from other variants of SCID.

In contrast to other SCID patients who usually do not develop serious infections before 2 months of age,15 patients with RD present much earlier with a predominance of invasive bacterial infections due to the associated agranulocytosis. Opportunistic infections, such as respiratory failure due to Pneumocystis jirovecii or systemic infections with cytomegalovirus, which are typical for other SCID entities, were not observed in this series of patients.

Another unique observation in this cohort is the high proportion of patients who were born prematurely and and/or small for gestational age. Because AK2 is a ubiquitously expressed protein involved in the basic mechanisms of cellular energy supply, this finding suggests that its deficiency may cause fetal stress, leading to premature birth.

Moreover, about half of the patients presented with additional hematological abnormalities affecting erythropoiesis and thrombopoiesis. Because these were also present in the absence of systemic infection or before birth, primary involvement can be suspected (supplemental Figures 1 and 2). These findings indicate that the enzyme deficiency may have a broader, although variable, effect on hematopoiesis not previously recognized.

One could suspect that AK2 deficiency remains unrecognized in a proportion of patients dying from severe fulminant bacterial infections in early infancy. RD should be considered and ruled out in any neonate with unexplained leukopenia. Absent hearing or the typical abnormalities in a bone marrow aspirate, as described above, can provide helpful additional clues. However, both are difficult to perform and potentially misleading in a seriously sick newborn. Finally, sequencing of AK2 will confirm the diagnosis. Newborn screening for SCID, which at present is routinely performed in the majority of states in the United States,16 will most likely identify these patients easily due to the absence of T cells and therefore low to absent T-cell receptor excision circle levels. Some children, however, might experience their first life-threatening infection before these results are available and the benefit for this group in comparison with other SCID entities might therefore be lower.

We were able to identify genetic defects in AK2 in all patients in whom this gene was sequenced (30 of 32 patients). The mutations included missense, nonsense, and splice-site mutations and large and small deletions and affected each of the 7 coding exons. The missense mutation c.524G>A was the most frequently detected genetic change and affected 3 independent families originating from the Arabic peninsula, which could indicate a higher frequency of this allele and possibly a common founder. In 2 of these patients, the mutation was associated with a leaky phenotype of SCID. One patient (patient 15) presented with an Omenn phenotype and a T-cell count of almost 2000/µL. The second patient (patient 6) with the same mutation presented with a high B-cell number (1850/µL) and abundant B-cell precursors in the marrow. This finding was initially misinterpreted as B-cell leukemia, but polyclonality was demonstrated (data not shown). The third patient (patient 9) with this same homozygous mutation had “classical” aleukocytosis (350/µL), which indicates that there is no reliable genotype-phenotype correlation.

In contrast to other SCID patients, permanent cure in patients with RD requires the correction of the myeloid lineage in addition to lymphoid reconstitution. According to the experience presented in this study, stable engraftment of hematopoietic stem cells is a crucial prerequisite to achieve normal myeloid function in patients with RD. Conditioning and alloreactive donor T cells are important factors that promote stem cell engraftment. Thus, in T-cell–depleted haploidentical transplantation, donor cell engraftment is dependent on the conditioning regimen. Accordingly, reduced intensity conditioning regimens without a myeloablative agent (n = 1, patient 16) or HSCT without any conditioning (n = 5; patients 17-21) were not successful in T-cell–depleted transplants. Even after conditioning with busulfan, only 6 of 11 patients (55%) engrafted, and 4 of the remaining patients experienced primary or secondary graft failure. In contrast, no graft failure was reported with T-cell–replete grafts after conditioning with busulfan. In this latter group, engraftment was not reliably achieved with less intense conditioning regimens: 3 out of 4 patients needed a second transplant because of either primary or secondary graft failure. Without any conditioning, T-cell–replete transplantation led to stable engraftment in a single patient after 2 attempts with a matched sibling graft. The assessment of the effectiveness of busulfan for myeloablation in this study is based on the combination with cyclophosphamide. Whether the combination with fludarabine, which was administered to 1 patient only, is equally effective in this disease remains unclear. The same applies for busulfan alone without additional components.

Without any previous experience, the necessity for conditioning was unknown in the early patients reported in this study, who were mostly transplanted from haploidentical donors. This fact at least partially contributes to the inferior results of T-cell–depleted transplantations, as depicted in Figure 3. Due to the limited number of patients per group, survival data should be interpreted very cautiously. In principle haploidentical T-cell–depleted transplantation makes sense for patients with RD if no well-matched donors are available, particularly utilizing newer haploidentical approaches. None of the patients in this cohort suffered from viral infections before transplant. Other SCID entities most frequently present with T-cell–dependent viral or opportunistic infections. For them, rapid T-cell reconstitution is clearly beneficial to clear these infections, and delayed T-cell reconstitution after haploidentical transplantation is a major disadvantage. RD patients, who most frequently present with bacterial infections, need rapid neutrophil engraftment to overcome their infections. Neutrophil reconstitution is not delayed after haploidentical transplantation, and haploidentical parental donors are readily available for the vast majority of patients.

Complete donor chimerism prevents secondary autologous reconstitution, which, in some patients, causes posttransplant neutropenia. Prolonged stimulation with granulocyte-colony stimulating factor may lead to the development of myelodysplastic syndrome as reported for 2 patients.14 In the case of a loss of myeloid engraftment and posttransplant neutropenia, retransplantation seems inevitable and should be considered early. Why neutropenia develops in some but not all patients with partial autologous reconstitution remains unclear.

In recent publications, new insight was gained into the molecular pathophysiology of AK2 deficiency.17 In a zebrafish model, Rissone et al18 were able to demonstrate that AK2 deficiency equally affects the myeloid lineage as well as hematopoietic stem and precursor cells. In an in vitro model for proliferation and differentiation of human bone marrow cells, Six et al19 demonstrate that lineage-negative CD34+ stem cells reside in hypoxic bone marrow niches and are not affected by AK2 deficiency because their energy needs are covered by anaerobic glycolysis.20 With proliferation and differentiation, cells switch to aerobic metabolism and become dependent on mitochondrial function and AK2.

The clinical data from our cohort are mostly in accordance with data generated in the zebrafish model and the in vitro assays on human bone marrow. Long-term survivors with stable mixed chimerism in their CD34+ compartment demonstrate that donor cells do not have any selective advantage in the competition with AK2-deficient lineage-negative cells. However, these autologous CD34+ cells do not contribute to granulopoiesis, as shown for patients 2 and 28 in Table 4.

There is some conflicting data regarding hematopoiesis. Rissone et al18 demonstrate in their zebrafish model that AK2 deficiency affects proliferation and maturation of red blood cell precursors. This is confirmed by the same group in a human in vitro differentiation model with induced pluripotent stem cells originating from a patient with AK2 deficiency, as the capacity of these cells to differentiate to erythroid cells is severely compromised.18 Although almost half of the patients reported in our cohort (44%) suffered from anemia at presentation (suggesting that AK2 deficiency negatively affects red blood cell maturation), autologous CD34+ cells seem to significantly contribute to the peripheral red blood cell pool in long-term survivors with stable mixed chimerism. These conflicting results from animal models, in vitro assays, and patient data cannot be explained. Functional assays on mutated AK2 proteins might be helpful to better explain the initial phenotype as well as posttransplant chimerism. Residual function of AK2 in autologous cells or even somatic mosaicism due to genetic reversions in hematopoietic lineages could contribute to “leaky” phenotypes. These factors are not considered in current models.

From a clinical point of view, sensorineural hearing disability has a strong impact on the development of these children after successful HSCT. The molecular pathology leading to this nonhematological manifestation of RD is unclear, and animal models have been unable to clarify the mechanism. An AK2-deficient mouse model is not yet established, because a complete knockout of AK2 seems to be lethal in early embryonic development (K.S., unpublished data). Cochlear implants are chosen by the majority of patients diagnosed and treated in recent years to correct the hearing disability. Older patients get along with conventional noninvasive hearing aids, which indicates some residual hearing capacity.

In summary, this international initiative has put together clinical and genetic data on the largest cohort of patients with RD so far. We have demonstrated the necessity for early diagnosis, rapid and decisive therapeutic measures, the superiority of T-cell–replete grafts, and the need for conditioning to reliably achieve myeloid engraftment (Table 4).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Beate Einsiedler and Rainer Muche from the Institute for Epidemiology and Medical Biometry (University of Ulm) for statistical support. The authors also thank Lueder Hinrich Meyer for immunophenotyping of bone marrow cells.

This work was supported by a grant 01GM1517B from the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (M.H. and K.S.), grants U54 AI 082973 and R13 AI 094943 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and Office of Rare Diseases, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health (M.J.C., L.D.N., and S-Y.P.), and by the Great Ormond Street Hospital Children´s Charity and the Great Ormond Street Hospital/University College London National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre (H.B.G.).

Authorship

Contribution: M.H., U.P., K.S., and W.F. designed and performed the study and prepared the initial draft of the manuscript in close cooperation with C.L.-P. and M.C.; M.H., C. L.-P., U.P., L.D.N., F.P., A.R.G., M.S., M.J.C., P.S., H.A.-M., D.A.-Z., S.-Y.P., W.A.H., H.B.G., P.V., K.O., K.I., H.Y., L.M.N., N.M.W., P.S.-P., K.-W.S., H.M., M.A.H., K.-M.D., C.S., D.M., E.-M.J., A.S.S., K.S., A.F., W.F., and M.C. were responsible for patient care and/or provided clinical, genetic, or laboratory data; and all authors contributed to the discussion and the preparation of the draft and have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

A complete list of the members of the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation Inborn Errors Working Party appears in the online appendix.

Correspondence: Manfred Hoenig, Department of Pediatrics, University Medical Center Ulm, Eythstrasse 24, 89075 Ulm, Germany; e-mail: manfred.hoenig@uniklinik-ulm.de.

![Figure 1. May-Grunwald-Giemsa stain of a bone marrow aspirate from a patient with RD (original magnification ×1000, immersion oil, Zeiss Axio Imager M1, AxioCam MRc [Carl Zeiss Microscopy, Jena, Germany]) showing immature lymphoid cells (hematogones) with slim cytoplasm as well as myeloblasts and a dysplastic promyelocyte with nuclear and cytoplasmic vacuoles. In the work-up of the bone marrow with immunostaining and flow cytometry, immature lymphocytes were identified as polyclonal B-cell precursors (flow cytometry of the bone marrow revealed a population of 46% with markers of pre–B cells CD10+/CD19+/cyIgM+/TdT+/CD34–; clonality was tested in a multiplex polymerase chain reaction for the rearranged B-cell receptor heavy chains [data not shown]).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/129/21/10.1182_blood-2016-11-745638/4/m_blood745638f1.jpeg?Expires=1769122772&Signature=kufKaLlRQ0xEG1qu6GDTMuUNo~XBwSdBMBiR8RZYUZPm0M2gs-F12I4-2tkthFqG4QQF7~16ONl2IJENqUx9wAQkJeeozPqMj5VBlaQWxAN1Y8sK9oqzhiuiv1vh783Qb2MZ~IsDZ-WO1EjtNmnSWy85~bWECqCU9M9fRML766HvI9ZybI8mlfkKHW8NWEWAonf5iayuOQPddG3TQ6tMmTUAUxe3O4rj13c~DjFmaVJPgL1~3eGUoFe~1ZMtRwGDaQBWY6iGjum2JB-gF8uRrc0R0nvPbydMom2ToWnqLPFidQGarL5EFrFbVke-QS7zn3EXQ3vMNGLWiyTNYNxCOg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal