Abstract

The canonical role of the hemostatic and fibrinolytic systems is to maintain vascular integrity. Perturbations in either system can prompt primary pathological end points of hemorrhage or thrombosis with vessel occlusion. However, fibrin(ogen) and proteases controlling its deposition and clearance, including (pro)thrombin and plasmin(ogen), have powerful roles in driving acute and reparative inflammatory pathways that affect the spectrum of tissue injury, remodeling, and repair. Indeed, fibrin(ogen) deposits are a near-universal feature of tissue injury, regardless of the nature of the inciting event, including injuries driven by mechanical insult, infection, or immunological derangements. Fibrin can modify multiple aspects of inflammatory cell function by engaging leukocytes through a variety of cellular receptors and mechanisms. Studies on the role of coagulation system activation and fibrin(ogen) deposition in models of inflammatory disease and tissue injury have revealed points of commonality, as well as context-dependent contributions of coagulation and fibrinolytic factors. However, there remains a critical need to define the precise temporal and spatial mechanisms by which fibrinogen-directed inflammatory events may dictate the severity of tissue injury and coordinate the remodeling and repair events essential to restore normal organ function. Current research trends suggest that future studies will give way to the identification of novel hemostatic factor-targeted therapies for a range of tissue injuries and disease.

Introduction

Fibrin deposition mediated through hemostasis and fibrinolysis has been extensively studied within and around vessels (eg, intravascular clot formation and dissolution); however, work over the past 20 years has highlighted critical roles for coagulation system components beyond simply maintenance of and pathologies linked to vascular integrity. It has become clear that a wide range of physiological and pathological responses to injury are influenced by coagulation factors in the extravascular milieu.

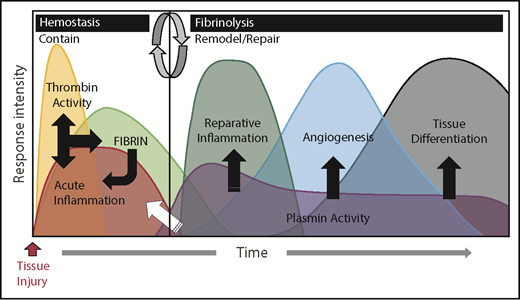

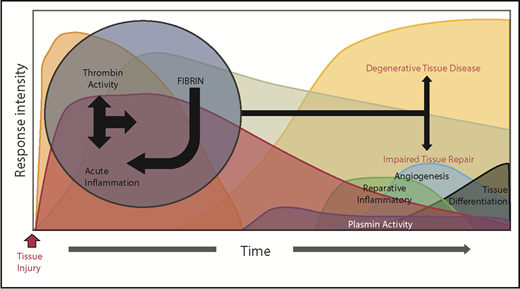

Fibrinogen and other coagulation factors are now understood to play key roles in the acute phase response caused by tissue injury. The acute phase response can be divided into 2 distinct biological phases that serve to resolve pathology caused by tissue injury. The first phase is dominated by thrombin cleavage of fibrinogen integrated with an acute inflammatory response that functions to contain tissue damage, stop the loss of blood, and prevent microbial infection. The second phase is dominated by plasmin dissolution of fibrin and other matrix proteins integrated with reparative inflammatory cells working to remodel and repair damaged tissue. In normal circumstances, the acute phase response follows a predictable and quantifiable time course with minimal risk of either complications during the convalescence of tissue injury or failed tissue repair (Figure 1). Whereas coagulation is essential for a normal acute phase response, a dysregulated acute phase response secondary to inappropriate coagulation-mediated activation of inflammation can be detrimental to tissue repair and homeostasis and even to surviving an injury (Figure 2). Indeed, genetic, pharmacologic or environmental alteration of the initial phase of the acute phase response leading to either exuberant or diminutive fibrin deposition may result in early complications of convalescence such as bleeding, thrombosis, systemic inflammatory response syndrome, or infection. Additionally, a failure of the second phase from compromised removal of fibrin results in a perpetual activation of unwanted biological activities, failed tissue repair, and tissue degeneration. Thus, following any tissue injury, it is essential that fibrin deposition and degradation occur in a precisely coordinated temporal and spatial manner to prevent bleeding and infection, control inflammation, and subsequently promote tissue repair.

Coagulation and fibrinolytic systems in the acute phase response. The biological systems activated during the acute phase response rapidly change and can be generally divided into 2 biologically distinct phases: “contain” and “remodel/repair.” Following injury, exposure of activating cell surfaces and/or matrices activates coagulation and acute inflammation, which work together and lead to thrombin activation and conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin. Together, acute inflammation, thrombin activity, and fibrin serve to contain ruptured compartments (eg, bleeding) and prevent or mitigate invasion by pathogens. Once containment is achieved, the acute phase response transitions to remodel/repair (circular arrows). Importantly, although inflammatory cells are crucial in both phases of the acute phase response, their phenotype and biological role is different in their respective phases. Plasmin promotes remodeling/repair because it is used by reparative inflammatory cells to degrade and remove damaged tissues and fibrin to promote angiogenesis and tissue differentiation/reconstruction. Collectively, in cases of a normal reparative response to injury, coagulation and fibrinolytic components work in concert to promote the transition of inflammatory cells to a reparative (tissue remodeling) phenotype as well as other mechanisms, culminating in timely tissue regeneration.

Coagulation and fibrinolytic systems in the acute phase response. The biological systems activated during the acute phase response rapidly change and can be generally divided into 2 biologically distinct phases: “contain” and “remodel/repair.” Following injury, exposure of activating cell surfaces and/or matrices activates coagulation and acute inflammation, which work together and lead to thrombin activation and conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin. Together, acute inflammation, thrombin activity, and fibrin serve to contain ruptured compartments (eg, bleeding) and prevent or mitigate invasion by pathogens. Once containment is achieved, the acute phase response transitions to remodel/repair (circular arrows). Importantly, although inflammatory cells are crucial in both phases of the acute phase response, their phenotype and biological role is different in their respective phases. Plasmin promotes remodeling/repair because it is used by reparative inflammatory cells to degrade and remove damaged tissues and fibrin to promote angiogenesis and tissue differentiation/reconstruction. Collectively, in cases of a normal reparative response to injury, coagulation and fibrinolytic components work in concert to promote the transition of inflammatory cells to a reparative (tissue remodeling) phenotype as well as other mechanisms, culminating in timely tissue regeneration.

A dysregulated acute phase response leads to destructive inflammation and impaired tissue remodeling. Genetic or environmental dysregulation of coagulation can provoke degenerative tissue disease and impair tissue repair through a multitude of mechanisms. Reciprocally, extreme and prolonged liberation of inflammatory cytokines leads to not only local, but also systemic activation of cellular inflammatory pathways, prolonging thrombin activation. Alternatively, impaired fibrinolysis (plasmin activity) prolongs the presence of fibrin, delaying the resolution of its inflammatory properties. Regardless of the mechanism, the prolonged acute inflammatory response interferes with transition to reparative inflammatory processes, evoking impaired tissue repair and degenerative tissue disease.

A dysregulated acute phase response leads to destructive inflammation and impaired tissue remodeling. Genetic or environmental dysregulation of coagulation can provoke degenerative tissue disease and impair tissue repair through a multitude of mechanisms. Reciprocally, extreme and prolonged liberation of inflammatory cytokines leads to not only local, but also systemic activation of cellular inflammatory pathways, prolonging thrombin activation. Alternatively, impaired fibrinolysis (plasmin activity) prolongs the presence of fibrin, delaying the resolution of its inflammatory properties. Regardless of the mechanism, the prolonged acute inflammatory response interferes with transition to reparative inflammatory processes, evoking impaired tissue repair and degenerative tissue disease.

The thrombin-fibrin(ogen) axis: a key pathway mediating inflammatory cell activity

Virtually all forms of tissue damage, regardless of the inciting source or severity of the injury, are associated with local activation of the coagulation system. Extravascular fibrin deposits are a near-universal feature within and around the damaged zones of tissue. Studies have highlighted that coagulation system activity and extravascular fibrin deposits associated with tissue injury are not simply a response to the injury to gain hemostasis, but rather are key functional factors in mediating the resulting inflammatory response. Here, we highlight key functional mechanisms of downstream coagulation and fibrinolytic factors in inflammation.

Inflammation-driven coagulation activity and coagulation-driven inflammation

Inflammation as a regulator of coagulation and fibrinolytic system activity is well recognized.1-4 Acute inflammation is known to shift the hemostatic balance toward a prothrombotic and antifibrinolytic state in which there is an increase in circulating levels of several key procoagulant and antifibrinolytic mediators. Activation of the coagulation and fibrinolytic systems following acute inflammatory events can lead to potentially devastating consumptive coagulopathy and disseminated intravascular coagulation5-7 ; however, a reciprocal pathway also exists whereby hemostatic factors affect inflammatory processes.3,4,8-14

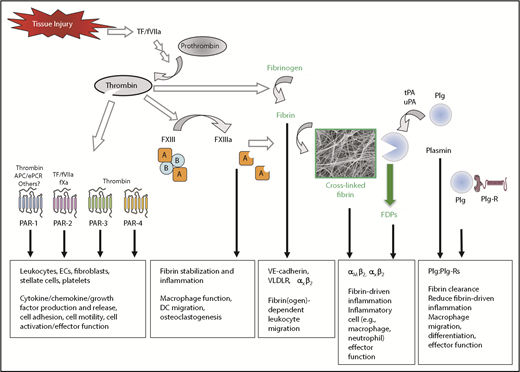

Thrombin has numerous downstream proteolytic targets that impact inflammatory processes (Figure 3). G-protein–coupled protease-activated receptors (PARs) have been shown to control the expression of a large number of cytokines and chemokines (eg, interleukin 1 [IL-1], IL-6, IL-8, migration inhibitory factor, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, and monocyte chemotactic protein MCP-1) in different cell types, including endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, fibroblasts, epithelial cells, and mononuclear cells.15-21 Furthermore, the activation of platelets by thrombin and other agonists is known to result in the release of a cocktail of chemokines and cytokines stored in platelet granules (eg, platelet factor-4, IL-8, macrophage inflammatory protein-1a, RANTES, monocyte chemotactic protein-3, CCL17, CCXL1, CXCL5, and serotonin) and expression of platelet surface adhesion molecules (eg, P-selectin, CD40 ligand) that control leukocyte trafficking and activity.22-26 When bound to thrombomodulin, thrombin generation of activated protein C appears to modulate the inflammatory response by limiting thrombin-coupled events and by directly altering inflammatory regulatory pathways. Activated protein C binding to monocytic cells has been shown to alter NF-κB–mediated gene expression and induce the production of antiapoptotic gene products.1,2,10 Recent studies have shown that activated protein C in complex with the endothelial cell protein C receptor regulates a number of cell functions critical to inflammatory pathways, in part through a unique PAR-1 activation pathway.27 Thus, thrombin-mediated signaling can affect inflammation through both primary and secondary pathways.

Coagulation and fibrinolytic system components in inflammation. Summary of mechanisms by which fibrinogen, thrombin, and fibrinolytic proteins contribute to inflammatory mechanisms. Boxed A indicates FXIII A subunit; circled B indicates FXIII B subunit. APC, activated protein C; EC, endothelial cell; ePCR, endothelial cell protein C receptor; FDP, fibrin degradation product; Plg, plasminogen; Plg-R, plasminogen receptor; TF, tissue factor; tPA, tissue-type plasminogen activator; uPA, urokinase-type plasminogen activator.

Coagulation and fibrinolytic system components in inflammation. Summary of mechanisms by which fibrinogen, thrombin, and fibrinolytic proteins contribute to inflammatory mechanisms. Boxed A indicates FXIII A subunit; circled B indicates FXIII B subunit. APC, activated protein C; EC, endothelial cell; ePCR, endothelial cell protein C receptor; FDP, fibrin degradation product; Plg, plasminogen; Plg-R, plasminogen receptor; TF, tissue factor; tPA, tissue-type plasminogen activator; uPA, urokinase-type plasminogen activator.

Although thrombin can clearly influence inflammatory events through PAR signaling pathways, fibrinogen as a downstream target of thrombin is one of the most potent contributors among all coagulation system proteins to the inflammatory response. Fibrinogen is a classic acute phase reactant in that inflammatory insults result in substantially increased hepatic expression and increased circulating protein.28,29 The potency of fibrinogen as an inflammatory mediator is linked to an ability to influence multiple aspects of leukocyte biology through direct and indirect mechanisms (Figure 3). Fibrin(ogen) can both facilitate leukocyte transmigration out of the vasculature and induce leukocyte effector functions by serving as a local, spatially defined cue within damaged tissue. Fibrin(ogen) can exert such wide-ranging effects by functioning as a ligand for a host of cell surface receptors including VE-cadherin, ICAM-1, αIIbβ3, α5β1, αVβ3, αMβ2, and αXβ230-37 expressed by cell types including leukocytes, endothelial cells, platelets, fibroblasts, and smooth muscle cells.35,38-45 Thus, the complexity of fibrinogen as an inflammatory mediator is dictated by the specific location or microenvironment of interactions and the engagement of specific binding partners.

Fibrinogen and leukocyte migration

The identification of fibrin(ogen) as a ligand for various cell surface receptors drove the hypothesis that fibrin(ogen) could serve as a bridging molecule to facilitate cell-to-cell adhesion between leukocytes and the endothelium. Several mechanisms of fibrinogen-dependent inflammatory cell migration have been proposed. An initial hypothesis focused on a pathway involving αMβ2 (Mac-1) on leukocytes, circulating fibrinogen, and ICAM-1 on endothelial cells.46 However, such a mechanism is largely not supported by studies of recombinant fibrinogen or fibrinogen domains, analyses of knockout mice, and the fact that soluble fibrinogen is a poor ligand of αMβ2.32,47,48 A second proposed pathway is that fibrin or specific fibrin degradation products support a bridging mechanism through leukocyte αXβ2 and endothelial cell VE-cadherin (Figure 3). This mechanism is supported by in vitro studies showing that the fibrin-derived N-disulfide knot fragment can simultaneously engage αXβ2 and VE-cadherin and promote leukocyte transmigration across endothelial monolayers.30,33,49,50 A third potential mechanism is that fibrin or fibrin degradation products (but not fibrinogen) anchored to the endothelial surface through very-low-density lipoprotein receptor (VLDLR) promotes leukocyte transmigration (Figure 3).51,52 The identification of multiple mechanisms with multiple binding partners may be indicative of fibrin(ogen) mediating leukocyte migration through different pathways depending on the inflammatory stimulus or tissue/vessel microenvironment.

An intriguing point of commonality between the proposed mechanisms implicating VE-cadherin and VLDLR is that fibrinogen residue Bβ15-42 appears to be required. Indeed, studies focusing on VE-cadherin or VLDLR documented that the isolated Bβ15-42 peptide is a potent inhibitor of leukocyte transmigration and thus can suppress inflammation. In separate studies, the pharmacological administration of Bβ15-42 was shown to be protective in terms of reduced inflammation and vascular leak in the context of animal models of acute and chronic myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury, kidney ischemia-reperfusion, and liver ischemia-reperfusion.49,53-56 Further, the Bβ15-42 peptide was shown to preserve organ function in animal models of polymicrobial sepsis, shock, and acute lung injury.57,58 Although additional study is required to further define mechanisms and rigorously test potential clinical utility, these collective findings highlight important contributions of fibrinogen to leukocyte/inflammatory cell function.

Fibrinogen and leukocyte effector function

Extravascular fibrin(ogen) deposits within and around inflammatory foci suggest that fibrin may directly influence inflammatory cell activities locally. Indeed, in vitro analyses44,59-61 have shown that fibrin(ogen) can alter leukocyte function, leading to changes in cell movement, phagocytosis, NF-κB–mediated transcription, production of chemokines and cytokines, degranulation, and other processes.44,59,60,62,63 As noted previously, fibrinogen can engage several leukocyte receptors that could mediate such potent effects; however, fibrinogen engagement of β2 integrins has emerged as a prominent pathway. Among the β2 integrin subfamily, αMβ2 (Mac-1, CD11b/CD18, and CR3) and αXβ2 (p150,95 and CD11c/CD18) have been identified as fibrin(ogen) receptors (Figure 3).34,47 The central role of this integrin family in leukocyte function is highlighted by the fact that a genetic deficiency in the common β2 subunit results in leukocyte adhesion deficiency type 1, characterized by profound defects in leukocyte activities and recurring chronic infections in affected patients.64 Two separate research groups initially identified αMβ2 as the cell surface receptor on monocytes and polymorphonuclear cells that supported leukocyte interaction with fibrinogen.45,65 Biochemical characterization revealed that the interaction of αMβ2 with fibrin(ogen) is mediated predominantly by the I-domain within the αM subunit66-69 and residues 377 through 395 of the fibrinogen γ chain (termed the P2 site).70 Subsequent analyses revealed that a peptide corresponding to residues γ 383 through 395 (termed P2-C) was sufficient for high-affinity binding and that mutation of γ 390 through 396 within an intact fibrinogen molecule eliminated αMβ2 binding.47,71 Similarly, αXβ2 engages fibrin(ogen) via the I-domain of αX.72 Multiple putative fibrinogen binding sites have been identified for αXβ2, including the P2 site of the γ chain as well as the central E-domain of fibrinogen.34,73

A key mechanistic element of fibrin(ogen) engagement of αMβ2 as a driver of inflammatory cell function is that the fibrinogen binding motif is cryptic, such that it is not available when fibrinogen is in the form of a soluble monomer.32 Only when fibrinogen becomes immobilized on a surface (such as the surface of damaged tissue) or is converted into a polymer does the binding motif become a high-affinity receptor for fibrinogen. This key property allows plasma fibrinogen to remain “invisible” to circulating leukocytes, but perfectly positions fibrin(ogen) in the role of rapid target recognition for leukocytes once it is released from circulation and deposits at sites of tissue damage/injury.

The role of fibrinogen in models of tissue injury and inflammation

Tissue injury and the resulting inflammatory response may be broken down into several general categories based on the initiating insult. Here, we summarize various contributions of fibrinogen and factors that contribute to fibrin formation and dissolution in distinct settings, including examples of inflammatory/immunological disease, infection, chemical injury, and mechanical injury. Animal model studies have confirmed that activation of the coagulation system and subsequent fibrin deposition is a feature of the response in each of these injury etiologies. Although there are points of commonality regarding the role of coagulation and fibrinogen, a central message from a multitude of studies is that the contribution of fibrin(ogen) is often context-dependent with features specific to the type of injury and tissue(s) affected.

Inflammatory disease

To differentiate the contribution of fibrinogen as a ligand to αMβ2-dependent leukocyte function from other ligands, Fibγ390-396A mice were generated that carry a mutation in the γ chain that eliminates αMβ2 engagement without altering circulating fibrinogen levels or polymer formation. Fibγ390-396A mice have been profoundly instructive in revealing the seminal role of fibrin(ogen) in driving inflammation and as well as identifying mechanisms by which fibrin(ogen) controls leukocyte function. Initial studies of Fibγ390-396A mice demonstrated that these animals have compromised antimicrobial host defense function.71 Subsequent analyses have illustrated that engagement of extravascular fibrin deposits by αMβ2-expressing cells (eg, neutrophils, macrophages, Kupffer cells, microglial cells) is a potent driver of local inflammation and downstream tissue damage. Indeed, Fibγ390-396A mice are significantly protected in models of inflammatory arthritis, colitis, neuroinflammatory disease, and musculoskeletal disease.74-78 The sufficiency of fibrinogen-αMβ2 interactions in driving destructive inflammation was shown in studies in which direct injection of wild-type fibrinogen into the central nervous system resulted in robust inflammatory demyelination, whereas the response was significantly less following fibrinogen γ390-396A injection.79

In addition to intense and destructive tissue inflammation, fibrin(ogen) appears to be a driver of chronic low-grade inflammation. Indeed, diet-induced obesity is a clinically common setting of low-grade chronic inflammation, and recent studies revealed that after a high-fat diet challenge, Fibγ390-396A mice gain substantially less weight, develop comparatively less adipose tissue inflammation, and are protected from obesity sequelae compared with similarly challenged wild-type mice.80 In the same study, thrombin inhibition with dabigatran etexilate also protected against obesity development, suggesting that fibrin polymerization may be a key mechanistic element in dictating the proinflammatory capacity of fibrinogen. The suggested hypothesis is that the conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin to crosslinked fibrin would increase fibrin(ogen)-driven inflammation implicating the molecular form of the molecule as a “rheostat” for leukocyte effector function.

Given the central role fibrinogen plays as a disease modifier in the context of inflammatory disease, a natural hypothesis is that factors that influence fibrin stability would also be inflammatory modifiers. Factor XIII (FXIII) is a thrombin-activated transglutaminase that catalyzes the formation of covalent ε-N-(γ-glutamyl)-lysine crosslinks between residues of target proteins.81 The primary function of FXIII is to stabilize fibrin clots through crosslinking of fibrin polymers to increase stiffness, reduce stretch, and limit plasmin-mediated proteolysis.82,83 Stable fibrin matrices appear to support increased inflammatory cell adhesion, migration, and cytokine production relative to monomeric fibrinogen,71,84 and studies of inflammatory arthritis in mice further support this concept.74 FXIII is also present in a cellular form (cFXIII) that is highly expressed in monocytes, certain macrophage subsets, and dendritic cells (DCs).85-87 The presence of cFXIIIA in the myeloid lineage appears to be functionally important. Monocytes isolated from FXIIIA-deficient patients have impaired Fcγ- and complement receptor-mediated phagocytic abilities.88 FXIIIA-deficient DCs have reduced chemotactic responses to CCL19, which is required for DC maturation.87 Crosslinking of AT1 receptors by cFXIIIA in human monocytes results in elevated adhesiveness to endothelial cells.89 Finally, FXIII has been to shown to support osteoclast differentiation and promote downstream bone destruction90,91 ; thus, FXIII can influence inflammation through fibrin(ogen)-dependent and fibrin(ogen)-independent functions.

Bacterial infection

Similar to inflammatory disease, fibrin deposits are routinely associated with bacterial foci within infected organ systems. Accordingly, studies in mouse models have identified multiple bacterial species sensitive to host fibrin(ogen). For example, a reduction of thrombin generation or the elimination of fibrinogen itself resulted in exacerbated pathogen spread and increased host mortality following subcutaneous infection with Group A streptococci.92 The clearance of purulent Yersinia pestis foci in the liver of infected hosts by neutrophils and macrophages was shown to be driven by fibrin deposits in and around the lesions.93 Fibrinogen-deficient mice also display significantly compromised pathogen clearance following peritoneal infection with Staphylococcus aureus.94,95 Fibγ390-396A mice displayed a similar reduction in S aureus clearance from the peritoneal cavity, suggesting a failure of fibrin(ogen)-driven αMβ2 innate immune cell function.71 Furthermore, genetically modified mice carrying normal levels of a mutant form of fibrinogen “locked” in monomer form (termed FibAEK) displayed a failure of S aureus clearance identical to that of fibrinogen-deficient mice.95 Thus, polymer formation can be tied to both the ability of fibrinogen to support hemostatic function as well as to immune effector function and antimicrobial host defense.

The ultimate contribution of fibrinogen to bacterial infection is complicated by the fact that numerous bacterial species have countered the potential of host fibrin(ogen) to limit infection and dissemination within infected hosts by evolving and maintaining virulence factors that target clotting system proteins. Indeed, pathogens have evolved factors that directly bind fibrinogen, promote fibrin formation by activating prothrombin, or that promote fibrin dissolution by activating plasminogen. For example, streptokinase produced by Group A streptococci and Pla enzyme produced by Y pestis each activate plasminogen and substantially increase the virulence of the respective pathogens through mechanisms linked to fibrin clearance.96-99 Fibrin clearance by the pathogen has the dual benefit of eliminating a barrier to dissemination and subverting fibrin-mediated host antimicrobial function. S aureus infection is a prime example of the contrasting and context-dependent role fibrinogen can play in bacterial infection. In opposition to findings in the S aureus peritonitis model, fibrinogen deficiency promoted host survival in the context of bacteremia in mice.100 The molecular basis of this finding was linked to direct binding of the bacterium to fibrinogen through the bacterial fibrinogen receptor, clumping factor A (ClfA). FibγΔ5 mice that express a mutant form of fibrinogen lacking the ClfA binding motif encoded by the final 5 amino acids of the γ chain exhibited a significant survival advantage over wild-type mice following intravenous S aureus challenge. The survival advantage of FibγΔ5 mice was characterized by reduced bacterial burdens in the tissues, a blunted proinflammatory cytokine response, and diminished tissue and organ damage.100 S aureus also express the virulence factor Efb to generate a “fibrinogen shield” that suppresses platelet activation and phagocytosis activity of innate immune cells.101,102 Similarly, S aureus expresses several additional fibrinogen binding proteins (eg, FnbpA, FnbpB) that function, in part, to support biofilm formation, which further serves to shield bacterial colonies from the host immune system.103,104 Collectively, these findings highlight how fibrinogen can have multiple and even opposing contributions to bacterial infection dictated by the pathogen itself, expression of bacterial virulence factors, and the path of infection.

Chemical liver injury

Thrombin has been implicated in acute liver injury produced by a laundry list of toxicants (eg, monocrotaline, endotoxin, carbon tetrachloride, thioacetamide, α-naphthylisothiocyanate), including those with omnipresent human exposure (eg, acetaminophen, alcohol), and other settings relevant to diverse disease states (eg, hepatic ischemia-reperfusion, bile duct ligation).105-108 Fibrin(ogen) deposition in the liver after acute and chronic challenge is commonly reported and is often considered an index of intrahepatic coagulation activity. However, limited evidence exists supporting a functional, pathological role for fibrin(ogen) in acute and chronic liver injury models.109 For example, fibrin-rich microthrombi are considered pathologic in liver fibrosis, but little experimental evidence supports a mechanistic connection. Fibrinogen deficiency was examined in chronic carbon tetrachloride–induced liver fibrosis in mice, but an absence of altered gross liver histology was the only reported result.110 Illustrating the context-dependent role of fibrin(ogen) in mouse models, in experimental biliary fibrosis, fibrin(ogen) deficiency worsened liver damage and fibrosis.111 In this model, fibrin(ogen)-β2 integrin interactions conferred protection with diminished bile duct hyperplasia.112,113

Fibrinogen was also once assumed to contribute to acute liver injury caused by acetaminophen (APAP) overdose but this hypothesis has since been overturned. Fibrinogen deficiency had no effect on acute APAP hepatotoxicity114 ; rather, the absence of fibrin(ogen) deposits in the injured liver dramatically inhibited liver repair.115 Additional studies documented that fibrin(ogen) engagement of β2 integrins, the same nonhemostatic function critical for driving inflammation, was central to driving repair of the liver by macrophages. Specifically, Fibγ390-396A mice developed modestly worsened initial injury and displayed decreased liver repair following APAP challenge.115 The precise mechanisms underlying this pathway are the subject of ongoing study, but what seems clear is that in the case of liver injury, fibrin(ogen) deposits appear to be a rapid response to injury necessary for hemostasis and for initiating leukocyte-directed repair of the damaged liver. This discovery raises numerous fascinating questions, particularly because it appears that 2 different thrombin targets exert dichotomous effects at different times during the course of APAP-induced liver injury, because PARs have been shown to drive necrosis early, whereas fibrin(ogen) stimulates subsequent repair.116-120

In patients, collecting definitive data as to whether fibrin(ogen)-deposits are present in the livers of patients is a challenge. Important considerations for such analyses include the potential of ex vivo clotting confounding interpretations and mechanisms for differentiating between fibrin polymer and immobilized fibrinogen monomer within injured and necrotic hepatic zones. Recent published and ongoing clinical studies have sought to define the effect of anticoagulation in patients with liver disease (reviewed elsewhere121-126 ). Whether any potential benefits or adverse reactions to anticoagulants in liver are mediated by fibrin(ogen) will be difficult to establish in patients; thus, studies of mouse models of chemically induced liver injury have served as an important link into the possible functional contribution of fibrinogen in this frequently encountered pathological setting.

Osteoporosis and fracture repair

Given that fibrin deposits drive inflammation, it is anticipated that persistent fibrin deposits would exacerbate inflammatory pathologies. Accordingly, fibrin clearance by plasmin activity would reduce fibrin-driven inflammation, and compromised plasminogen activation (or the elimination of plasminogen) would increase inflammation. In line with this concept, plasminogen-deficient mice suffer from a wasting disease characterized by inflamed mucosal lesions that are corrected by imposing fibrinogen deficiency.127,128 Further, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 increases in acute and chronic inflammatory states. Elimination of tissue- or urokinase-plasminogen activator can result in increased inflammation, at least in certain contexts.129-132

Bone homeostasis and bone fracture repair are particularly sensitive to accumulations of persistent fibrin deposits. Osteoporosis is an inflammatory disease highlighted by low bone mass and increased bone fragility.133,134 Plasminogen-deficient mice uniformly develop severe osteoporosis at a young age, as characterized by reduced cortical bone and trabecular thickness, loss of bone fractional volume resulting in diminished biomechanical properties, and spinal kyphosis.78 Fibrin deposits are observed within the regions of bone loss in plasminogen-deficient mice. Fibrin as the driver of inflammation and bone loss in osteoporosis was supported by findings indicating that each of the bone pathologies (and corresponding inflammatory markers) were reduced in plasminogen-deficient mice by crossing these animals to fibrinogen-deficient or, more notably, Fibγ390-396A mice.78 Indeed, in vitro studies indicated that immobilized fibrinogen can potentiate the differentiation of monocytes into osteoclasts, a specialized inflammatory cell that mediates bone resorption, mediated by RANK/RANKL.78 It is noteworthy that the same set of conditions in patients in which osteoporosis is most common, including obesity, diabetes, smoking, and menopause,135-138 are each associated with suppression of fibrinolysis. Thus, the studies performed in plasminogen-deficient mice provide a likely molecular mechanism for the exacerbation of osteoporosis observed in humans.

Bone fracture is a traumatic tissue injury in which significant fibrin deposits are located in and around the injury site.139 A long-held belief was that fibrin was essential for proper bone healing by enhancing reparative inflammatory and mesenchymal progenitor cell egress into the zone of injury. Contrary to this dogma, recent findings demonstrated that fibrinogen-deficient mice show no temporal or quantitative differences in the development or subsequent remodeling of a complete femur fracture.140 This demonstrates that fibrin, although required to limit hemorrhage, is unnecessary for efficient fracture repair. In stark contrast, the inhibition of fibrin clearance in the fracture field in plasminogen-deficient mice severely impaired fracture vascularization and precluded bone union. Further, the failure of fracture repair in plasminogen-deficient mice resulted in a severe pathology of adjacent soft-tissue (muscle) mineralization, termed dystrophic calcification, which ultimately progressed to heterotopic ossification (HO).140 Notably, the elimination of fibrinogen in plasminogen-deficient mice significantly restored normal fracture repair and reduced HO. Follow-up studies highlighted how plasminogen deficiency can promote HO in the context of traumatic soft-tissue muscle injury via a mechanism independent of fibrinogen.141 Similar to osteoporosis, impaired fibrinolysis is a feature common to comorbidities (eg, obesity, diabetes, smoking, advanced age)142-145 associated with impaired fracture repair. Thus, studies in plasminogen-deficient mice suggest that persistent fibrin deposits may be at the core of impaired fracture repair in patients and that suppression of plasmin activity may be a key a molecular feature of muscle pathologies secondary to significant bone trauma.

The role of plasminogen extends beyond simply clearing proinflammatory fibrin matrices. Plasminogen is a major driver of leukocyte migration (eg, macrophages) in part from the expression of plasminogen receptors that serve to promote leukocyte migration.146,147 Plasminogen receptor-KT is a key contributor in this regard because its genetic elimination or pharmacological blockade has been shown to significantly reduce macrophage migration both in vitro and in vivo.148,149 Beyond just migration, plasminogen has been shown to promote macrophage phagocytosis, gene expression, phenotype (eg, M1/M2), and differentiation (eg, foam cell formation).150,151 Indeed, plasminogen as a driver of inflammation is supported by studies in plasminogen-deficient mice that display protection from arthritis, inflammatory demyelinating disease, colitis, obesity, and chemically induced liver injury.114,152-154 Thus, plasminogen appears to influence inflammation through fibrinogen-dependent and fibrinogen-independent functions.

Conclusion

Collective studies over the past 2 decades have underscored a preeminent role for fibrinogen and factors that promote fibrin formation and dissolution in tissue inflammation and remodeling. Several take-home messages have emerged from these provocative studies. Fibrin(ogen), thrombin, and plasmin exert pleiotropic effects through multiple targets, substrates, and mechanisms. There are points of commonality, including the universal presence of fibrin within inflammatory foci and that extravascular fibrin deposits exacerbate inflammation across a spectrum of disease models. However, fibrin(ogen) in many circumstances exerts context-dependent effects in settings of both tissue inflammation and repair. Indeed, determinants such as cell and tissue type, etiology of the injury, and unique elements of the injured microenvironment can each modify the overall contribution of soluble fibrinogen and fibrin deposits. Nevertheless, thrombin, fibrinogen, FXIII, and plasmin appear to be viable and attractive therapeutic targets that may be modified without substantially compromising hemostasis. As highlighted here, studies of Fibγ390-396A mice strongly suggest that targeting the γ390-396 motif will offer protection from inflammation and downstream organ/tissue destruction without negatively affecting hemostasis. Similarly, recent studies have shown that FXIII may be reduced to levels that offer protection from thrombosis without increasing bleeding.155 Whether similar reductions in FXIII also offer protection in the context of inflammatory diseases remains to be established. Studies over the next several decades will likely give way to novel coagulation and fibrinolytic factor–targeted therapies for a range of tissue injuries and disease.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Anna Kopec for her assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (R01DK105099) (J.P.L.), National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (R01ES017537) (J.P.L.), National Cancer Institute (R01CA211098) (M.J.F.), and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (U01HL143403) (M.J.F.); the Department of Orthopaedics and Rehabilitation–Vanderbilt University Medical Center (J.G.S.); and The Caitlin Lovejoy Fund (J.G.S.).

Authorship

Contribution: J.P.L., J.G.S., and M.J.F. contributed to writing and editing the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Matthew J. Flick, Division of Experimental Hematology and Cancer Biology, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, 3333 Burnet Ave, Cincinnati, OH 45229-3039; e-mail: matthew.flick@cchmc.org.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal