Key Points

Nuclear PKM2 is upregulated in neutrophils after the onset of ischemic stroke and promotes neutrophil hyperactivation.

PKM2 deficiency in myeloid cells improves short- and long-term stroke outcome by limiting postischemic cerebral thrombo-inflammation.

Abstract

There is a critical need for cerebro-protective interventions to improve the suboptimal outcomes of patients with ischemic stroke who have been treated with reperfusion strategies. We found that nuclear pyruvate kinase muscle 2 (PKM2), a modulator of systemic inflammation, was upregulated in neutrophils after the onset of ischemic stroke in both humans and mice. Therefore, we determined the role of PKM2 in stroke pathogenesis by using murine models with preexisting comorbidities. We generated novel myeloid cell–specific PKM2−/− mice on wild-type (PKM2fl/flLysMCre+) and hyperlipidemic background (PKM2fl/flLysMCre+Apoe−/−). Controls were littermate PKM2fl/flLysMCre– or PKM2fl/flLysMCre–Apoe−/− mice. Genetic deletion of PKM2 in myeloid cells limited inflammatory response in peripheral neutrophils and reduced neutrophil extracellular traps after cerebral ischemia and reperfusion, suggesting that PKM2 promotes neutrophil hyperactivation in the setting of stroke. In the filament and autologous clot and recombinant tissue plasminogen activator stroke models, irrespective of sex, deletion of PKM2 in myeloid cells in either wild-type or hyperlipidemic mice reduced infarcts and enhanced long-term sensorimotor recovery. Laser speckle imaging revealed improved regional cerebral blood flow in myeloid cell–specific PKM2-deficient mice that was concomitant with reduced post-ischemic cerebral thrombo-inflammation (intracerebral fibrinogen, platelet [CD41+] deposition, neutrophil infiltration, and inflammatory cytokines). Mechanistically, PKM2 regulates post-ischemic inflammation in peripheral neutrophils by promoting STAT3 phosphorylation. To enhance the translational significance, we inhibited PKM2 nuclear translocation using a small molecule and found significantly reduced neutrophil hyperactivation and improved short-term and long-term functional outcomes after stroke. Collectively, these findings identify PKM2 as a novel therapeutic target to improve brain salvage and recovery after reperfusion.

Introduction

At present, an acute ischemic stroke is managed by intravenous thrombolysis with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rtPA) and/or mechanical thrombectomy. Although both of these approaches are effective, they have limitations. For example, early arterial reocclusion and the more unsatisfactory long-term outcome were observed in nearly 17% to 34% of patients with stroke after administration of rtPA,1,2 suggesting modest efficacy of intravenous thrombolysis. Although mechanical thrombectomy is much more efficacious, ∼50% of patients who were treated for acute stroke and who had large-vessel occlusion have suboptimal outcomes.3 Altogether, these limitations highlight the critical need for novel ancillary treatment that effectively enhances the limited success of stroke reperfusion therapies.

Because ischemic brain injury is aggravated by both thrombosis and inflammation (thromboinflammation),4,5 an ideal target for improving stroke outcome should be one that inhibits thrombo-inflammatory responses without a significant risk of bleeding complications. Recently, the glycolytic enzyme pyruvate kinase muscle 2 (PKM2) has been implicated not only as a critical regulator of aerobic glycolysis but also as an activator of transcription of pro-inflammatory mediators, including interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and IL-6.6-8 Pyruvate kinase (PK) exists in 4 different isoforms (PKR, PKL, PKM1, PKM2) and is encoded by 2 distinct genes, PKLR and PKM, in mammals. PKR is expressed in erythrocytes, PKL in liver and kidney, and PKM1 is expressed in differentiated adult tissues with high adenosine triphosphate requirement such as heart, brain, and muscle. PKM2 is expressed in many tissues including spleen, lung, and all cancer cell lines.9 During the past few years, PKM2 has generated significant interest because of its upregulation in activated immune cells, smooth muscle cells, and platelets.10-13 Unlike other isoforms of PK that exist and function as tetramers, PKM2 exists in tetrameric and dimeric forms composed of identical monomers but with different biological activities. In addition to its role in glycolysis, PKM2 also possesses protein kinase activity.14,15 Upon stimulation, dimeric PKM2 translocates to the nucleus where PKM2 catalyzes the transfer of phosphate from phosphoenolpyruvate to serine, threonine, or tyrosine residues on target substrates.15-18 The dimeric PKM2 is known to promote inflammatory macrophage activation,12,19 autoimmune encephalomyelitis,20 and allergic airways disease.7 Neutrophils, the most abundant white blood cells, are among the first cells in the blood to respond to an acute ischemic insult, and they play a key role in stroke exacerbation.21-27 However, whether PKM2 promotes neutrophil hyperactivation upon acute ischemic stroke and thereby mediates ischemic brain injury remains unclear. In this study, we elucidated the role of PKM2 in the pathogenesis of ischemic stroke. To enhance the translational significance of this study, we specifically measured the effect of sex, preexisting comorbidities, and the 2 forms of reperfusion (filament mechanical occlusion and autologous clot and rtPA).

Materials and methods

Detailed information on materials and methods is available in the supplemental data (available on the Blood Web site).

Human participants

The study involving human participants was previously approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Iowa, and informed consent was obtained from patients or their surrogates.

Mice

The PKM2fl/fl mouse strain was initially provided by Matthew G. Vander Heiden (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Boston, MA).28 To generate myeloid cell–specific PKM2-deficient mice (PKM2fl/flLysMCre+/−), PKM2fl/fl mice were crossed with LysMCre+/+ mice (supplemental Figure 1A). To generate myeloid cell–specific PKM2−/− mice on a hyperlipidemic apolipoprotein E-deficient (Apoe−/−) background (PKM2fl/fl LysMCre+/−Apoe−/−), PKM2fl/fl Apoe−/− mice were crossed with LysMCre+/−Apoe−/− mice. Littermate PKM2fl/flLysMCre−/− and PKM2fl/flLysMCre−/−Apoe−/− mice were used as controls.

Filament and embolic stroke models

Mice were anesthetized with 1% to 1.5% isoflurane mixed with medical air. After a midline incision, the right common carotid artery was temporarily clamped, and a silicon monofilament (702245PK5re Doccol) or a single homologous embolus (∼15 mm) was inserted via the external carotid artery into the internal carotid artery up to the origin of the middle cerebral artery. Reperfusion was achieved by removing the filament after 60 or 30 minutes and opening the common carotid artery (for the filament model) or by infusion of rtPA (10 mg/kg, 10% volume by bolus and remaining slow infusion for 30 minutes) for embolic model. Laser Doppler flowmetry was used for each mouse to confirm the successful induction of ischemia and reperfusion.

Results

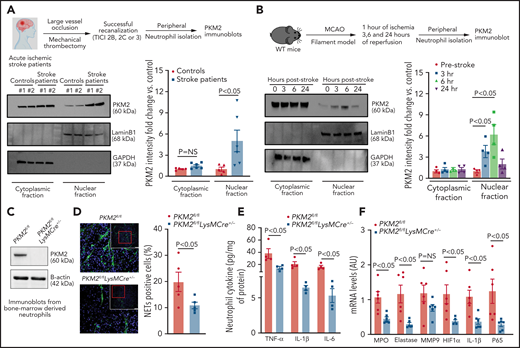

Human and mouse circulating neutrophils exhibit increased PKM2 nuclear translocation after acute ischemic stroke

Evidence suggests increased PKM2 nuclear translocation in cancer cells and in the activated immune cells when they are stimulated with agonists.6,12,16,19 We determined whether PKM2 nuclear translocation increases in neutrophils in the setting of ischemic stroke. Western blot analysis revealed an ∼threefold increase in nuclear PKM2 levels in peripheral neutrophils of patients with ischemic stroke treated with mechanical thrombectomy compared with healthy controls (Figure 1A). The baseline characteristics of the patients and recanalization status are provided in supplemental Table 1. Similarly, a time-dependent increase (up to 6 hours) in nuclear PKM2 expression was observed in peripheral neutrophils isolated from the wild-type (WT) mice that underwent 60 minutes of cerebral ischemia followed by 3, 6, or 23 hours of reperfusion (Figure 1B). Conversely, peripheral monocytes did not exhibit increased nuclear PKM2 levels after stroke in mice (supplemental Figure 2).

Nuclear PKM2 is elevated in peripheral neutrophils after a stroke in humans and in WT mice and regulates neutrophil hyperactivation. (A) Top: schematic of experimental design. Bottom: western blot analysis of PKM2 in the cytosolic and nuclear fraction from the peripheral neutrophils isolated from the patients with acute ischemic stroke who underwent successful mechanical thrombectomy. The quantitative data for cytosolic and nuclear PKM2 intensity (normalized to the intensity of lamin-B1/glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) are shown on the right. (B) Top: schematic of experimental design. Bottom: western blot analysis of PKM2 in the cytosolic and nuclear fraction from the peripheral neutrophils of male WT mice. The quantitative data for cytosolic and nuclear PKM2 intensity (normalized to the intensity of lamin-B1/GAPDH at each time point) are shown on the right. (C) Western blot analysis of PKM2 from neutrophils derived from the bone marrow of male mice. (D) Immunofluorescence analysis of NETs from peripheral neutrophils isolated 6 hours after reperfusion. Neutrophils were stimulated with a suboptimal concentration of PMA (10 ng/mL), and NETs were visualized by using SYTOX Green stain. Scale bars, 100 µm. Quantification is shown on the right. (E) Inflammatory cytokines in peripheral neutrophils isolated 6 hours after reperfusion from each group as analyzed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). (F) Gene expression analysis for the neutrophils isolated 6 hours after reperfusion as analyzed by reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction. Data are from 2-way repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) (Kruskal-Wallis test) followed by Fisher’s least significant difference (LSD) test; panels (A-B); or an unpaired Student t test (D-F). Data are mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM); n = 4-6 (A-B); n = 4-5 (D-E); n = 6 (F). AU, arbitrary units; HIF1-α, hypoxia-inducible factor 1-α; MCAO, middle cerebral artery occlusion; MMP9, matrix metallopeptidase 9; mRNA, messenger RNA; NS, not significant; TICI, thrombolysis in cerebral infarction.

Nuclear PKM2 is elevated in peripheral neutrophils after a stroke in humans and in WT mice and regulates neutrophil hyperactivation. (A) Top: schematic of experimental design. Bottom: western blot analysis of PKM2 in the cytosolic and nuclear fraction from the peripheral neutrophils isolated from the patients with acute ischemic stroke who underwent successful mechanical thrombectomy. The quantitative data for cytosolic and nuclear PKM2 intensity (normalized to the intensity of lamin-B1/glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) are shown on the right. (B) Top: schematic of experimental design. Bottom: western blot analysis of PKM2 in the cytosolic and nuclear fraction from the peripheral neutrophils of male WT mice. The quantitative data for cytosolic and nuclear PKM2 intensity (normalized to the intensity of lamin-B1/GAPDH at each time point) are shown on the right. (C) Western blot analysis of PKM2 from neutrophils derived from the bone marrow of male mice. (D) Immunofluorescence analysis of NETs from peripheral neutrophils isolated 6 hours after reperfusion. Neutrophils were stimulated with a suboptimal concentration of PMA (10 ng/mL), and NETs were visualized by using SYTOX Green stain. Scale bars, 100 µm. Quantification is shown on the right. (E) Inflammatory cytokines in peripheral neutrophils isolated 6 hours after reperfusion from each group as analyzed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). (F) Gene expression analysis for the neutrophils isolated 6 hours after reperfusion as analyzed by reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction. Data are from 2-way repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) (Kruskal-Wallis test) followed by Fisher’s least significant difference (LSD) test; panels (A-B); or an unpaired Student t test (D-F). Data are mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM); n = 4-6 (A-B); n = 4-5 (D-E); n = 6 (F). AU, arbitrary units; HIF1-α, hypoxia-inducible factor 1-α; MCAO, middle cerebral artery occlusion; MMP9, matrix metallopeptidase 9; mRNA, messenger RNA; NS, not significant; TICI, thrombolysis in cerebral infarction.

PKM2 promotes neutrophil hyperactivation after ischemic stroke in mice

We evaluated inflammatory status in the peripheral monocytes and neutrophils of WT mice at an early time point (6 hours) after reperfusion. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay revealed increased levels of inflammatory cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), IL-1β, and IL-6 in both monocytes and neutrophils (P < .05 vs sham; supplemental Figure 3). Notably, a marked increase in TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 levels was observed in neutrophils when compared with monocytes after stroke (Figure 3). We focused on neutrophils because nuclear PKM2 was upregulated in peripheral neutrophils but not in monocytes at 6 hours after stroke (Figure 1; supplemental Figure 2). Increased pro-inflammatory cytokine status was associated with increased neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) (supplemental Figure 4A) and expression of several pro-inflammatory genes, including MPO (myeloperoxidase), elastase, HIF1α, and P65 (supplemental Figure 4B), suggesting that cerebral ischemia and reperfusion promote neutrophil hyperactivation. To confirm a definitive role for PKM2 in neutrophil hyperactivation in the context of ischemic stroke, we generated novel myeloid cell–specific PKM2-deficient mice (PKM2fl/flLysMCre+/−; supplemental Figure 1A). Genomic polymerase chain reaction confirmed the presence of LysMCre gene in PKM2fl/fl mice (supplemental Figure 1B). By using western blotting, we confirmed the absence of PKM2 in neutrophils from PKM2fl/fl LysMCre+/− mice (Figure 1C). To simplify, from this point onward, littermate PKM2fl/fl LysMCre−/− mice will be referred as PKM2fl/fl mice. Next, we subjected PKM2fl/flLysMCre+/− and littermate control PKM2fl/fl mice to 1 hour of cerebral ischemia and 6 hours of reperfusion. Because upregulated pro-inflammatory cytokine status was associated with increased NETosis in the setting of ischemic stroke, we determined whether PKM2 modulates NETosis by aggravating pro-inflammatory response. Peripheral neutrophils isolated 6 hours after reperfusion were stimulated with a suboptimal concentration of phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA;10 ng/mL). The percentage of NET-positive cells was reduced in PKM2fl/fl LysMCre+/− mice (P < .05 vs PKM2fl/fl mice; Figure 1D). Furthermore, we found significantly reduced levels of inflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 and a reduction in the expression of pro-inflammatory genes, including MPO, elastase, HIF1α, IL-1β, and p65 in peripheral neutrophils after 6 hours of reperfusion in PKM2fl/flLysMCre+/− mice (P < .05 vs PKM2fl/fl mice; Figure 1E-F). Together, these results suggest that PKM2 potentiates neutrophil hyperactivation after ischemic stroke.

Myeloid cell–specific PKM2−/− mice exhibit reduced infarct area and improved long-term sensorimotor outcome

To evaluate the role of PKM2 in stroke outcomes, PKM2fl/fl LysMCre+/− and littermate PKM2fl/fl male and female mice were subjected to 1 hour of ischemia and 23 hours of reperfusion in the filament model. Both male and female PKM2fl/flLysMCre+/− mice exhibited smaller infarcts and better neurologic outcomes on day 1 when compared with littermate controls (supplemental Figure 5). Infarcts and neurologic scores were comparable between PKM2+/+LysMCre+ and PKM2fl/fl mice (supplemental Figure 6), ruling out nonspecific effects of LysM-Cre recombinase expression on stroke outcome.

Current Stroke Therapy Academic Industry Roundtable (STAIR) guidelines for preclinical assessment of novel therapeutic targets for stroke recommend evaluating underlying mechanisms for stroke progression, with an assessment of response to treatment in at least 2 different stroke models in both sexes with preexisting comorbidities that adequately mimic the human physiology.29,30 Following STAIR recommendations, we generated PKM2fl/fl LysMCre+/− mice and littermate control PKM2fl/fl LysMCre−/− mice on the hyperlipidemic Apoe−/− background. We chose the preexisting comorbid condition of hyperlipidemia because it is known to exacerbate ischemic damage and worsen the sensorimotor deficit by promoting endothelial dysfunction, inflammation, oxidative stress, and neuronal death,31 and thereby enhancing stroke sensitivity. All the mice were fed a regular chow diet after weaning until age 8 to 10 weeks, an age at which no significant vascular lesions are found (data not shown) to minimize the potential confounding effects of advanced atherosclerotic lesions that can impair collateral flow and indirectly influence the stroke outcome. Body weight, plasma cholesterol, triglycerides, and complete blood counts were comparable between these groups (supplemental Tables 2 and 3).

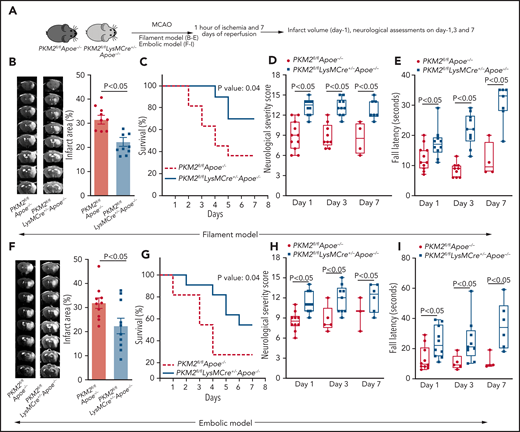

Using the filament stroke model, susceptibility to cerebral ischemia and reperfusion injury were evaluated after 1, 3, and 7 days of reperfusion (Figure 2A). We observed significantly reduced infarct area in PKM2fl/flLysMCre+/−Apoe−/− mice at day 1 (P < .05 vs PKM2fl/flApoe−/− mice; Figure 2B). Consistent with these results, at day 7, PKM2fl/flLysMCre+/−Apoe−/− mice exhibited a better survival rate (∼70%) compared with PKM2fl/flApoe−/− mice (Figure 2C). Next, using the same set of mice, we evaluated the modified neurologic severity score (mNSS) based on spontaneous activity, symmetry in limb movement, forepaw outstretching, climbing, body proprioception, responses to vibrissae touch (on the scale of 3 to 18; higher score indicates a better outcome), and motor function using an accelerated rota-rod test. We observed that PKM2fl/flLysMCre+/−Apoe−/− mice exhibited improved neurologic outcome and motor function on days 1, 3, and 7 compared with PKM2fl/flApoe−/− mice (Figure 2D-E). Laser Doppler flow measurements (supplemental Table 4) and physiological parameters (supplemental Table 5) were similar among groups before, during, and after ischemia. No gross differences in cerebrovascular anatomy were observed between groups (supplemental Figure 7). To determine whether the observed phenotype is reproducible in another model, we used an autologous clot model treated with rtPA (embolic model). Consistent with the filament stroke model, PKM2fl/flLysMCre+/− Apoe−/− mice exhibited improved stroke outcome in the embolic model (Figure 2F-I).

Deletion of PKM2 in myeloid cells improves stroke outcome in the filament and embolic models in a preexisting comorbid condition of hyperlipidemia. (A) Schematic of experimental design. (B-E) Filament model; n = 10-11 male mice. (B) Left: representative magnetic resonance imaging from 1 mouse of each genotype on day 1. White is the infarct area. Right: corrected mean infarct area of each genotype. (C) Survival rate between day 0 and day 7 after 60 minutes of transient ischemia. (D) mNSS in the same mice at days 1, 3, and 7 based on spontaneous activity, symmetry in the movement of 4 limbs, forepaw outstretching, climbing, body proprioception, and responses to vibrissae touch (higher score indicates a better outcome). (E) Fall latency in the accelerated rota-rod test. (F-I) Embolic model; n = 10 male mice. (F) Infarction (%), (G) survival rate, (H) mNSS, and (I) fall latency. (F) Left: representative magnetic resonance imaging from 1 mouse of each genotype on day 1. White is the infarct area. Right: corrected mean infarct area of each genotype. The animals that successfully completed the particular neurologic test were included in the analysis (see exclusion/inclusion criteria in “Methods”). Data are from an unpaired Student t test, mean ± SEM (B-F) or median ± range (D-E,H-I). Comparison of survival curves was evaluated by log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test (C,G) or by repeated measures ANOVA (Kruskal-Wallis test) followed by Fisher’s LSD test (D-E,H-I).

Deletion of PKM2 in myeloid cells improves stroke outcome in the filament and embolic models in a preexisting comorbid condition of hyperlipidemia. (A) Schematic of experimental design. (B-E) Filament model; n = 10-11 male mice. (B) Left: representative magnetic resonance imaging from 1 mouse of each genotype on day 1. White is the infarct area. Right: corrected mean infarct area of each genotype. (C) Survival rate between day 0 and day 7 after 60 minutes of transient ischemia. (D) mNSS in the same mice at days 1, 3, and 7 based on spontaneous activity, symmetry in the movement of 4 limbs, forepaw outstretching, climbing, body proprioception, and responses to vibrissae touch (higher score indicates a better outcome). (E) Fall latency in the accelerated rota-rod test. (F-I) Embolic model; n = 10 male mice. (F) Infarction (%), (G) survival rate, (H) mNSS, and (I) fall latency. (F) Left: representative magnetic resonance imaging from 1 mouse of each genotype on day 1. White is the infarct area. Right: corrected mean infarct area of each genotype. The animals that successfully completed the particular neurologic test were included in the analysis (see exclusion/inclusion criteria in “Methods”). Data are from an unpaired Student t test, mean ± SEM (B-F) or median ± range (D-E,H-I). Comparison of survival curves was evaluated by log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test (C,G) or by repeated measures ANOVA (Kruskal-Wallis test) followed by Fisher’s LSD test (D-E,H-I).

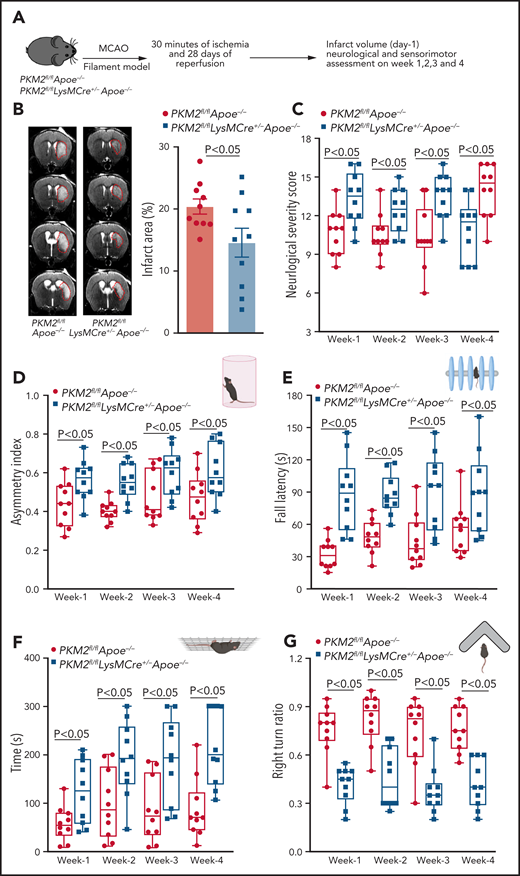

Because higher mortality was observed in hyperlipidemic mice after 1 hour of ischemia, we could not determine long-term outcomes up to 4 weeks. Therefore, we reduced ischemia time from 60 minutes to 30 minutes and evaluated sensorimotor recovery up to 4 weeks (Figure 3A). Consistent with the results of 60 minutes ischemia, PKM2fl/flLysMCre+/−Apoe−/− mice exhibited reduced infarct area and improved neurologic outcome (mNSS) from 1 week up to 4 weeks (P < .05 vs PKM2fl/fl Apoe−/−; Figure 3B-C). Next, we performed a cylinder test, a sensorimotor test to assess asymmetry in forelimb use during vertical exploratory behavior inside a glass cylinder. We found significantly enhanced sensorimotor recovery up to 4 weeks in PKM2fl/fl LysMCre+/−Apoe−/− mice (P < .05 vs PKM2fl/flApoe−/−; Figure 3D). Furthermore, PKM2fl/flLysMCre+/−Apoe−/− mice exhibited improved motor function and improved motor strength up to 4 weeks (P < .05 vs PKM2fl/flApoe−/−; Figure 3E-F). Next, we performed a corner test, which is a combined postural, sensory, and motor function test. PKM2fl/flLysMCre+/−Apoe−/− mice exhibited reduced functional deficits (P < .05 vs PKM2fl/fl Apoe−/−; Figure 3G). Together, these results suggest that deletion of PKM2 in myeloid cells enhances the poststroke long-term sensorimotor recovery.

Myeloid cell–specific PKM2−/− mice exhibit improved long-term sensorimotor recovery up to day 28. (A) Schematic of experimental design. (B) Left: representative magnetic resonance imaging from 1 mouse of each genotype on day 1 in filament model. White is the infarct area. Right: corrected mean infarct area of each genotype. (C) mNSS in the same mice at weeks 1, 2, 3, and 4 based on spontaneous activity, symmetry in the movement of 4 limbs, forepaw outstretching, climbing, body proprioception, and responses to vibrissae touch (higher score indicates a better outcome). Sensorimotor recovery in the same mice as analyzed by asymmetry index in cylinder test (D), fall latency in accelerated rota-rod test (E), motor strength in hanging-wire test (F), and right turn ratio in corner test (G). The data in panels C-G are in box plots and the horizontal bars indicate median value. The animals that successfully completed the particular neurologic test were included in the analysis (see exclusion/inclusion criteria in “Methods”). Data are mean ± SEM (B) or median ± range (C,G); n = 10 male mice (B,G). Data are from an unpaired Student t test (B) or 2-way repeated measures ANOVA (Kruskal-Wallis test) followed by Fisher’s LSD test (D,G).

Myeloid cell–specific PKM2−/− mice exhibit improved long-term sensorimotor recovery up to day 28. (A) Schematic of experimental design. (B) Left: representative magnetic resonance imaging from 1 mouse of each genotype on day 1 in filament model. White is the infarct area. Right: corrected mean infarct area of each genotype. (C) mNSS in the same mice at weeks 1, 2, 3, and 4 based on spontaneous activity, symmetry in the movement of 4 limbs, forepaw outstretching, climbing, body proprioception, and responses to vibrissae touch (higher score indicates a better outcome). Sensorimotor recovery in the same mice as analyzed by asymmetry index in cylinder test (D), fall latency in accelerated rota-rod test (E), motor strength in hanging-wire test (F), and right turn ratio in corner test (G). The data in panels C-G are in box plots and the horizontal bars indicate median value. The animals that successfully completed the particular neurologic test were included in the analysis (see exclusion/inclusion criteria in “Methods”). Data are mean ± SEM (B) or median ± range (C,G); n = 10 male mice (B,G). Data are from an unpaired Student t test (B) or 2-way repeated measures ANOVA (Kruskal-Wallis test) followed by Fisher’s LSD test (D,G).

Apoe deficiency in mice promotes blood-brain barrier breakdown and neuronal death, disrupts cerebrovascular reflexes, and worsens ischemic perfusion defect.31,32 To rule out the role of Apoe deficiency in PKM2-dependent worsening of stroke outcome, we evaluated stroke outcome in another hyperlipidemic model: low-density lipoprotein receptor–deficient (Ldlr−/−) mice using a bone marrow transplantation approach (supplemental Figure 8A). Complete blood counts did not differ between the groups (supplemental Table 6). We observed significantly improved stroke outcome in Ldlr−/− mice that were transplanted with bone marrow cells of PKM2fl/flLysMCre+/− mice when compared with Ldlr−/− mice that were transplanted with bone marrow cells of control PKM2fl/fl mice (supplemental Figure 8B-C).

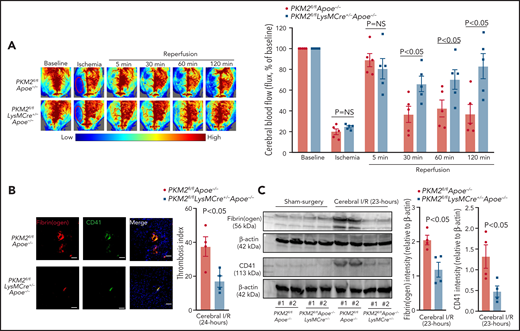

Myeloid cell–specific PKM2−/− mice exhibited improved local cerebral blood flow and reduced postischemia and postreperfusion thromboinflammation

To determine whether improved stroke outcome in the PKM2fl/fl LysMCre+/−Apoe−/− mice was associated with reduced post-ischemia and reperfusion, cerebral thrombosis, and improved local cerebral blood flow, laser speckle imaging was performed at different time points. We found that regional cerebral blood flow was improved at 30, 60, and 120 minutes after reperfusion in PKM2fl/flLysMCre+/−Apoe−/− mice (P < .05 vs PKM2fl/fl Apoe−/− mice; Figure 4A). Consistent with these results, we observed significantly reduced intracerebral fibrinogen, platelet (CD41+) deposition, and reduced thrombotic index in the PKM2fl/flLysMCre+/− Apoe−/− mice (Figure 4B-C). To evaluate poststroke inflammation, we quantified MPO levels, neutrophil elastase levels, NF-κB activity, and cerebral neutrophil influx and cytokines. Peripheral neutrophils of PKM2fl/flLysMCre+/−Apoe−/− mice exhibited significantly reduced MPO and elastase levels, decreased NF-κB activity, and reduced neutrophil infiltration and cytokine levels in the infarcted and peri-infarct regions (P < .05 vs PKM2fl/flApoe−/− mice; Figure 5A-C; supplemental Figure 9A-B). Human studies and experimental stroke models suggest that monocytes are recruited into the ischemic area of brain, most abundantly at days 3 to 7 after stroke, so we analyzed brain monocyte and macrophage content at day 3 after stroke. By using immunohistochemistry, we found reduced macrophage content (CD68+ cells) in infarcted regions of PKM2fl/flLysMCre+/−Apoe−/− when compared with control PKM2fl/flLysMCre+/− mice (supplemental Figure 10).

Myeloid cell–specific PKM2−/− mice exhibited improved local cerebral blood flow and reduced poststroke cerebral thrombosis. (A) Left: representative images were taken by using laser speckle imaging of regional cerebral blood flow in the cortical region. Right: quantification at different time points (5 to 120 minutes). (B) Left: representative immunostaining images for platelets (CD41+, green; fibrinogen, red). Scale bar, 100 μm. Right: thrombotic index as defined by the ratio of occluded brain vessels to the total brain vessels in the ipsilateral hemisphere. (C) Brain homogenates from the infarcted and peri-infarcted area after 1 hour of ischemia and 23 hours of reperfusion were processed for western blotting: representative western blots and densitometric analysis of fibrinogen and platelets (CD4+). β-actin was used as a loading control. All data are from male mice and are mean ± SEM; n = 5 (A); n = 4 (B-C). Data are from 2-way repeated measures ANOVA (Kruskal-Wallis test) followed by Fisher’s LSD test (A), or an unpaired Student t test (B-C). I/R, ischemia and reperfusion.

Myeloid cell–specific PKM2−/− mice exhibited improved local cerebral blood flow and reduced poststroke cerebral thrombosis. (A) Left: representative images were taken by using laser speckle imaging of regional cerebral blood flow in the cortical region. Right: quantification at different time points (5 to 120 minutes). (B) Left: representative immunostaining images for platelets (CD41+, green; fibrinogen, red). Scale bar, 100 μm. Right: thrombotic index as defined by the ratio of occluded brain vessels to the total brain vessels in the ipsilateral hemisphere. (C) Brain homogenates from the infarcted and peri-infarcted area after 1 hour of ischemia and 23 hours of reperfusion were processed for western blotting: representative western blots and densitometric analysis of fibrinogen and platelets (CD4+). β-actin was used as a loading control. All data are from male mice and are mean ± SEM; n = 5 (A); n = 4 (B-C). Data are from 2-way repeated measures ANOVA (Kruskal-Wallis test) followed by Fisher’s LSD test (A), or an unpaired Student t test (B-C). I/R, ischemia and reperfusion.

PKM2 mediates poststroke inflammation by promoting phosphorylation of STAT3 in neutrophils. (A) Left: representative image of flow cytometric analysis for MPO from each group. Right: quantification of MPO expression levels in peripheral neutrophils isolated 6 hours post-reperfusion in mice with stroke. Neutrophils were stimulated with a suboptimal concentration of PMA (10 ng/mL). (B) Elastase levels as determined by ELISA from the cell extracts of peripheral neutrophils, isolated 6 hours post-reperfusion in mice with sham-surgery or stroke. (C) Left: representative immunostained images for neutrophils (brown Ly6B.2-positive cells indicated by red arrows) in infarcted brain regions. Inset in the boxed region is magnified and shown in microphotograph. Scale bar, 100 μm. Right: quantification. (D) Peripheral neutrophils were isolated 6 hours postreperfusion in mice with stroke, and cell extracts were IP with PKM2 antibody or control IgG and immunoblotted for PKM2 and STAT3. (E) Western blot analysis of PKM2 cell extracts from the peripheral neutrophils isolated 6 hours post-reperfusion in mice with stroke. The quantitative phospho STAT3 and phospho NF-κβ intensity (normalized to the total STAT3 and NF-κβ, respectively) are shown on the right. Data are from female mice and are mean ± SEM. n = 5 (A); n = 3-4 (B-C,E). Data are from 2-way repeated measures ANOVA (Kruskal-Wallis test) followed by Fisher’s LSD test (A-B) and unpaired Student t-tests (C,E). FSC, forward scatter; IgG, immunoglobulin G; IP, immunoprecipitated; MPO, myeloperoxidase; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity.

PKM2 mediates poststroke inflammation by promoting phosphorylation of STAT3 in neutrophils. (A) Left: representative image of flow cytometric analysis for MPO from each group. Right: quantification of MPO expression levels in peripheral neutrophils isolated 6 hours post-reperfusion in mice with stroke. Neutrophils were stimulated with a suboptimal concentration of PMA (10 ng/mL). (B) Elastase levels as determined by ELISA from the cell extracts of peripheral neutrophils, isolated 6 hours post-reperfusion in mice with sham-surgery or stroke. (C) Left: representative immunostained images for neutrophils (brown Ly6B.2-positive cells indicated by red arrows) in infarcted brain regions. Inset in the boxed region is magnified and shown in microphotograph. Scale bar, 100 μm. Right: quantification. (D) Peripheral neutrophils were isolated 6 hours postreperfusion in mice with stroke, and cell extracts were IP with PKM2 antibody or control IgG and immunoblotted for PKM2 and STAT3. (E) Western blot analysis of PKM2 cell extracts from the peripheral neutrophils isolated 6 hours post-reperfusion in mice with stroke. The quantitative phospho STAT3 and phospho NF-κβ intensity (normalized to the total STAT3 and NF-κβ, respectively) are shown on the right. Data are from female mice and are mean ± SEM. n = 5 (A); n = 3-4 (B-C,E). Data are from 2-way repeated measures ANOVA (Kruskal-Wallis test) followed by Fisher’s LSD test (A-B) and unpaired Student t-tests (C,E). FSC, forward scatter; IgG, immunoglobulin G; IP, immunoprecipitated; MPO, myeloperoxidase; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity.

PKM2 is known to phosphorylate STAT3 and regulate the expression of several pro-inflammatory genes.6,10 We determined PKM2 interaction with STAT3 in neutrophils. Immunoprecipitation showed that PKM2 interacts with STAT3 (Figure 5D). Immunoblot analysis revealed increased STAT3 phosphorylation in neutrophils isolated from control PKM2fl/flApoe−/− mice with stroke compared with mice with sham control (Figure 5E, after 6 hours of reperfusion). Conversely, we observed significantly reduced STAT3 phosphorylation in neutrophils isolated from PKM2fl/flLysMCre+/−Apoe−/− mice compared with PKM2fl/fl Apoe−/− mice (Figure 5E). Because activated STAT3 is known to maintain constitutive NF-κB activity by prolonging NF-κB nuclear retention,33 we analyzed NF-κB phosphorylation. We found that NF-κB phosphorylation significantly increased in neutrophils isolated from control PKM2fl/flApoe−/− mice with stroke compared with mice with sham surgery. PKM2fl/flLysMCre+/− Apoe−/− mice exhibited reduced NF-κB phosphorylation in neutrophils compared with PKM2fl/fl Apoe−/− mice in the setting of stroke (Figure 5E). Together, these results suggest that PKM2 regulates postischemic inflammation by promoting STAT3 phosphorylation in neutrophils. Next, we determined the effect of PKM2 deletion on glycolytic proton efflux rate (glycoPER) in neutrophils by using a Seahorse extracellular flux analyzer. We observed that neutrophils from the myeloid cell–specific PKM2-deficient mice exhibit reduced glycoPER at baseline and when stimulated with PMA (100 nM) (supplemental Figure 11).

ML265 treatment significantly reduces PKM2 nuclear translocation and neutrophil activation after acute ischemic stroke

To evaluate the therapeutic significance of targeting PKM2 in improving stroke outcome after reperfusion, we used ML265, a small molecule that inhibits PKM2 nuclear translocation by inducing PKM2 tetramerization.34 We first determined the in vivo dose of ML265 that was required to significantly inhibit PKM2 nuclear translocation in neutrophils after stroke. ML265 was administered at 10, 25, or 50 mg/kg 5 minutes after reperfusion, and neutrophils were isolated 6 hours after reperfusion (Figure 6A). We found that ML265 at 25 or 50 mg/kg significantly inhibited PKM2 nuclear translocation in neutrophils (Figure 6B). We therefore selected a minimal dose of 25 mg/kg for further study and evaluated inflammatory status in the peripheral neutrophils at 6 hours of reperfusion. We observed significantly reduced levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 and reduced NETosis (P < .05 vs vehicle; Figure 6C-D). Next, we determined whether ML265 inhibits glycolytic rate in neutrophils from the WT mice. We found ML265 (at 10 µM or 50 µM) did not reduce glycoPER in PMA (100 ng)–activated neutrophils (supplemental Figure 12), suggesting that improved stroke outcome after ML265 treatment is most likely mediated because of the reduced thromboinflammation rather than decreased glycolytic rate in neutrophils.

ML265 treatment significantly reduces PKM2 nuclear translocation and neutrophil hyperactivation after acute ischemic stroke. (A) Schematic of experimental design. (B) Western blot analysis of PKM2 in the cytosolic and nuclear fraction from the peripheral neutrophils isolated 6 hours after reperfusion in mice treated with ML265 at the indicated doses. The quantitative data of cytosolic and nuclear PKM2 intensity (normalized to the intensity of lamin-B1 or GAPDH at each time point) are shown on the right. (C) TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 levels in neutrophils isolated 6 hours after reperfusion from each group as analyzed by ELISA. (D) Immunofluorescence analysis of NETs from the neutrophils isolated 6 hours after reperfusion. Neutrophils were stimulated with the suboptimal concentration of PMA (10 ng/mL), and NETs were visualized by using SYTOX Green stain. Scale bars, 100 µm. Quantification is shown on the right. Data are from male WT mice and are mean ± SEM; n = 3 (B); n = 4 (C); n = 5 (D). Data are from 2-way repeated measures ANOVA (Kruskal-Wallis test) followed by Fisher’s LSD test (B), or an unpaired Student t test (C,D).

ML265 treatment significantly reduces PKM2 nuclear translocation and neutrophil hyperactivation after acute ischemic stroke. (A) Schematic of experimental design. (B) Western blot analysis of PKM2 in the cytosolic and nuclear fraction from the peripheral neutrophils isolated 6 hours after reperfusion in mice treated with ML265 at the indicated doses. The quantitative data of cytosolic and nuclear PKM2 intensity (normalized to the intensity of lamin-B1 or GAPDH at each time point) are shown on the right. (C) TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 levels in neutrophils isolated 6 hours after reperfusion from each group as analyzed by ELISA. (D) Immunofluorescence analysis of NETs from the neutrophils isolated 6 hours after reperfusion. Neutrophils were stimulated with the suboptimal concentration of PMA (10 ng/mL), and NETs were visualized by using SYTOX Green stain. Scale bars, 100 µm. Quantification is shown on the right. Data are from male WT mice and are mean ± SEM; n = 3 (B); n = 4 (C); n = 5 (D). Data are from 2-way repeated measures ANOVA (Kruskal-Wallis test) followed by Fisher’s LSD test (B), or an unpaired Student t test (C,D).

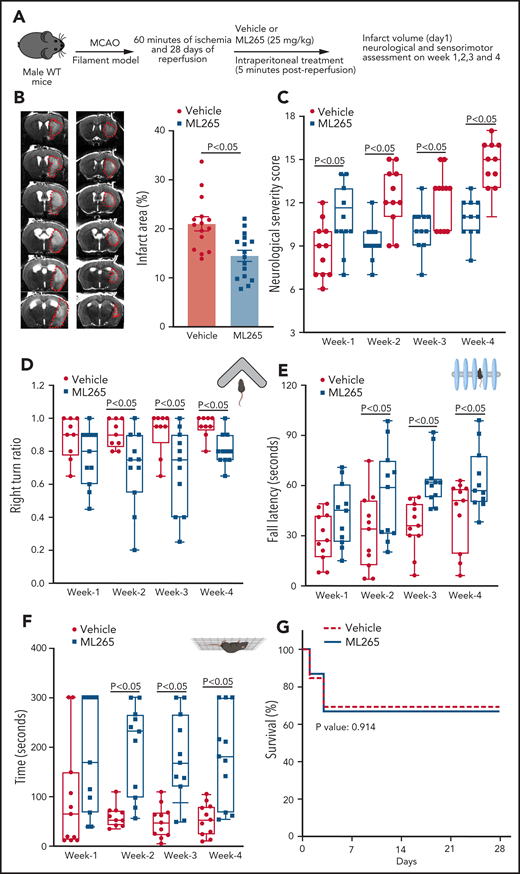

ML265-treated mice exhibited improved long-term sensorimotor outcomes

We assessed stroke outcomes in ML265-treated mice. Male 10- to 12-week-old WT mice were randomly assigned to receive either ML265 (25 mg/kg) or vehicle, and susceptibility to ischemia or reperfusion injury was evaluated after 60 minutes of ischemia and up to 4 weeks of reperfusion in the filament model (Figure 7A). The schematic of the study design is shown in supplemental Figure 13. Treatments were performed 5 minutes after reperfusion; the individuals who performed the surgery and monitored behavioral outcomes were blinded to the treatments. A significant reduction in infarct area (∼31%) was observed in ML265-treated mice compared with control-treated mice (Figure 7B). Next, using the same cohort of mice, we evaluated neurological outcome (mNSS) for up to 4 weeks. We found that the ML265-treated group exhibited significantly improved mNSS compared with the vehicle-treated group (Figure 7C). To evaluate the long-term sensorimotor outcome, we performed corner test, rota-rod test, and hanging wire tests. We found that the ML265-treated group exhibited significantly improved long-term sensorimotor outcome compared with the vehicle-treated group (Figure 7D-F), whereas the mortality rate did not differ between the groups (Figure 7G). Next, we evaluated the effect of targeting PKM2 treatment on stroke outcome in the preexisting comorbid condition of hyperlipidemia. Male mice 8 to 10 weeks old were randomly assigned to receive either ML265 (25 mg/kg) or vehicle, and stroke outcomes were evaluated. We found that ML265 treatment significantly reduced infarct area and improved neurologic score in PKM2fl/flApoe−/− mice but not in PKM2fl/flLysMCre+/−Apoe−/− mice (supplemental Figure 14). Comparable stroke outcome in ML265-treated PKM2fl/fl LysMCre+/−Apoe−/− mice and vehicle-treated PKM2fl/fl LysMCre+/−Apoe−/− suggests that ML265 most likely improves stroke outcomes by inhibiting nuclear PKM2 translocation in myeloid cells.

ML265-treated male WT mice exhibited significantly reduced infarct area and improved long-term sensorimotor outcomes. (A) Schematic of experimental design. (B) Left: representative magnetic resonance imaging from one mouse of each group on day 1 in filament model. White is the infarct area. Right: corrected mean infarct area of each genotype. (C) mNSS in the same mice at weeks 1, 2, 3, and 4 based on spontaneous activity, symmetry in the movement of 4 limbs, forepaw outstretching, climbing, body proprioception, and responses to vibrissae touch (higher score indicates a better outcome). Sensorimotor recovery in the same mice as analyzed by right turn ratio in corner test (D), fall latency in accelerated rota-rod test (E), and motor strength in hanging-wire test (F). The data in panels C-F are in box plots and the horizontal bars indicate median value. (G) Survival rate between day 0 and day 28. Data are mean ± SEM (B) and median ± range (C,F); n = 15-16 mice. Data are from an unpaired Student t test (B), or 2-way repeated measures ANOVA (Kruskal-Wallis test) followed by Fisher’s LSD test (C,F). Comparison of survival curves was evaluated by log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test (G).

ML265-treated male WT mice exhibited significantly reduced infarct area and improved long-term sensorimotor outcomes. (A) Schematic of experimental design. (B) Left: representative magnetic resonance imaging from one mouse of each group on day 1 in filament model. White is the infarct area. Right: corrected mean infarct area of each genotype. (C) mNSS in the same mice at weeks 1, 2, 3, and 4 based on spontaneous activity, symmetry in the movement of 4 limbs, forepaw outstretching, climbing, body proprioception, and responses to vibrissae touch (higher score indicates a better outcome). Sensorimotor recovery in the same mice as analyzed by right turn ratio in corner test (D), fall latency in accelerated rota-rod test (E), and motor strength in hanging-wire test (F). The data in panels C-F are in box plots and the horizontal bars indicate median value. (G) Survival rate between day 0 and day 28. Data are mean ± SEM (B) and median ± range (C,F); n = 15-16 mice. Data are from an unpaired Student t test (B), or 2-way repeated measures ANOVA (Kruskal-Wallis test) followed by Fisher’s LSD test (C,F). Comparison of survival curves was evaluated by log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test (G).

Discussion

In the past, several strategies have been used to improve stroke outcomes after reperfusion, including neuroprotective, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory agents.35 However, most of the strategies have failed in large clinical trials, mainly because of the complexity of human stroke, lack of rigor with the preclinical assessment of these agents, and the design and implementation of the clinical trials.36 Notably, several preclinical studies used young, healthy mice without preexisting comorbidities. Moreover, with the notable exception of the ESCAPE-1 trial,37 no phase 3 trial was designed to determine whether neuroprotection could ameliorate the consequences of reperfusion by salvaging penumbras.38 In this study, we implemented several STAIR/RIGOR recommendations to overcome methodologic shortcomings, and we demonstrated a mechanistic role for nuclear PKM2 in ischemic stroke pathogenesis. We believe that these findings are novel and may have clinical significance for several reasons. First, nuclear PKM2 was upregulated in peripheral neutrophils after ischemic stroke in humans and mice, which contributes to neutrophil hyperactivation. Second, using novel myeloid cell–specific PKM2-deficient mice and filament and embolic models of stroke, we provide in vivo evidence that PKM2 modulates cerebral ischemia and reperfusion injury in both healthy participants and in patients with preexisting comorbid conditions by regulating thromboinflammation. Third, as a translational potential, we demonstrated that therapeutic inhibition of nuclear PKM2 translocation improves stroke outcome and enhances long-term sensorimotor recovery in mice. Our findings provide the until now unidentified role of neutrophil PKM2 in regulating neutrophil hyperactivation and poststroke thromboinflammation.

Inflammation predisposes to ischemic stroke and can trigger several pathogenic aspects that are detrimental to brain salvage and recovery after reperfusion. Gene expression profile changes rapidly in blood after stroke in humans and occurs predominantly in neutrophils.39 These homeostasis changes in neutrophils, associated with stroke severity, may play an instrumental role by contributing to systemic inflammation. Neutrophils increase stroke severity by several mechanisms, including triggering capillary sludging, generating free radicals, secreting inflammatory mediators, and enhancing thrombosis via the formation of neutrophil-platelet aggregates and NETs.27,40,41 Herein, we demonstrated that genetic deletion of PKM2 in myeloid cells reduced inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6) and downregulated several proinflammatory genes (MPO, elastase, HIF1α, and IL-1β) within neutrophils after cerebral ischemia or reperfusion. Importantly, we demonstrated that either deletion of PKM2 in myeloid cells or inhibition of nuclear PKM2 translocation with small-molecule ML265 improved short- and long-term functional outcome. IL-6 in stroke patients is known to be associated with poor clinical outcomes.42 TNF-α and IL-1β are known to enhance leukocyte migration to the ischemic region, promote necrosis, increase endothelial dysfunction, disrupt the blood-brain barrier and increase edema formation after stroke.43 Together, these observations suggest that nuclear PKM2 in neutrophils drives post-ischemic inflammatory response by upregulating several pro-inflammatory genes and thereby exacerbates stroke outcome.

After a stroke, the ischemic core undergoes permanent necrotic cell death while the salvageable penumbral tissue is prone to further neuronal cell death as a result of multiple mechanisms that include excitotoxicity, oxidative stress, ionic imbalance, and inflammation.44 Although intravenous thrombolysis and mechanical thrombectomy are the pillars of acute stroke care, they do not target the mechanisms that can cause secondary brain damage in the penumbral tissue. Moreover, the no-reflow phenomenon, which is characterized by secondary microvascular cerebral thrombosis (primarily platelets and neutrophils), and penumbral tissue damage despite successful recanalization are still unique problems. Herein, we observed that PKM2 regulates the formation of NETs in the setting of ischemic stroke and myeloid cell–specific deficiency of PKM2 improved regional cerebral blood flow after reperfusion. Collectively, these observations suggest that PKM2 may potentiate post-ischemic secondary thrombosis, by promoting NET formation, in addition to inflammation. NETs, which are composed of chromatin and antimicrobial proteins (histones, myeloperoxidase, and elastase), are known to contribute to stroke pathogenesis.25,27,45 Indeed, we found reduced expression of MPO and elastase in peripheral neutrophils of myeloid cell–specific PKM2-deficient mice after stroke. The precise mechanism by which PKM2 potentiates formation of NETs remains unclear and is still an area needing investigation. However, we speculate that nuclear PKM2 may promote NETosis by aggravating the proinflammatory environment.

We also investigated the molecular mechanism by which myeloid cell–specific PKM2 promotes stroke exacerbation. Unlike other isoforms of PK that exist and function as stable tetramers, PKM2 subunits form tetramers and dimers composed of the same monomers but with different biological activities. Evidence suggests that only dimeric PKM2 can enter the nucleus to exert protein kinase activity. Nuclear PKM2 interacts with STAT3, enhances its phosphorylation at Y705, and is known to contribute to cell proliferation in cancer cells15 and inflammatory cytokine production in macrophages.19 Although it is known that PKM2 interacts with STAT3 in other cell types, the role of PKM2 in STAT3 phosphorylation in peripheral neutrophils in the context of stroke is not defined. In this study, we observed that similar to other cell types, PKM2 interacts with STAT3 in neutrophils. Genetic deletion of PKM2 significantly reduced phosphorylation of STAT3 levels in peripheral neutrophils after stroke. STAT3 regulates granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF)–dependent accumulation of immature bone marrow neutrophils and acute G-CSF–induced neutrophil mobilization,46 indicating the key role of STAT3 in neutrophil function during a pro-inflammatory environment. In addition, STAT3-deficient neutrophils have a cell-autonomous defect in migration toward ligands for CXCR2, as well as defective secretion of MPO.47 We found reduced MPO and elastase levels after stroke in PKM2-deficient neutrophils in line with these observations. Crosstalk between STAT3 and NF-κB has been reported by several studies, including activation of STAT3 by NF-κB–regulated factors such as IL-6.33,48 Recently, it was shown that activated STAT3 maintains constitutive NF-κB activity by prolonging NF-κB nuclear retention.33 Consistent with these observations, we found that PKM2 deficiency in peripheral neutrophils results in reduced NF-κB phosphorylation, reduced NF-κB activity, and decreased proinflammatory cytokine production after ischemic stroke. Although neutrophils from myeloid cell–specific PKM2-deficient mice exhibited reduced glycolytic rate, neutrophils after ML265 treatment did not exhibit reduced glycolysis, suggesting that most likely the PKM2/STAT3/NF-κB axis regulates neutrophil hyperactivation after cerebral ischemia and thereby contributes to stroke severity.

The strength of this study is that we determined the role of PKM2 by using both genetic and pharmacologic approaches in 2 different stroke models, in both sexes and in mice with comorbidities. Despite its strengths, our study has limitations. First, PKM2 is expressed by other cell types, including endothelial cells, monocytes, macrophages, T cells, and platelets. The possibility of potential unexpected and adverse physiological adverse effects of blocking nuclear PKM2 in other cell types cannot be ruled out. Nevertheless, we speculate that such a scenario is unlikely because of the acute nature (single-dose) of the ML265 treatment. Second, previous studies by other groups have suggested an important role of macrophages49 and T cells in stroke pathogenesis.50 Thus, the possibility of macrophage or T-cell–derived PKM2 in mediating stroke outcome cannot be completely ruled out. Extending these studies to other species (eg, hypertensive rats) may further validate the therapeutic potential of these novel findings. In summary, we have demonstrated a mechanistic role of PKM2 in regulating neutrophil hyperactivation and acute ischemic stroke.

Acknowledgments

This study (the AKC laboratory) was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R35HL139926), the NIH, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (R01NS109910, U01NS113388) and an American Heart Association Established Investigator Award (18EIA33900009). N.D. is supported by the American Society of Hematology (ASH) Scholar Award and ASH Restart Award, and by a Career Development Award (20CDA35260123) from the American Heart Association.

Authorship

Contribution: N.D. and A.K.C. conceptualized and designed the experiments and wrote, reviewed, and edited the manuscript; N.D., R.B.P., P.D., M.G., G.D.F., M.J., and M.K. performed the experiments; D.T. acquired magnetic resonance imaging scans; H.O. collected informed consent and samples from stroke patients; E.C.L. provided intellectual input and reviewed and edited the manuscript; N.D. and A.K.C. acquired funding for the research; and A.K.C. supervised the study.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Anil K. Chauhan, Department of Internal Medicine, 3120 Medical Laboratories, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA 52242; e-mail: anil-chauhan@uiowa.edu.

The data that support the findings of this study are available by sending an email request to Anil K. Chauhan at anil-chauhan@uiowa.edu.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal