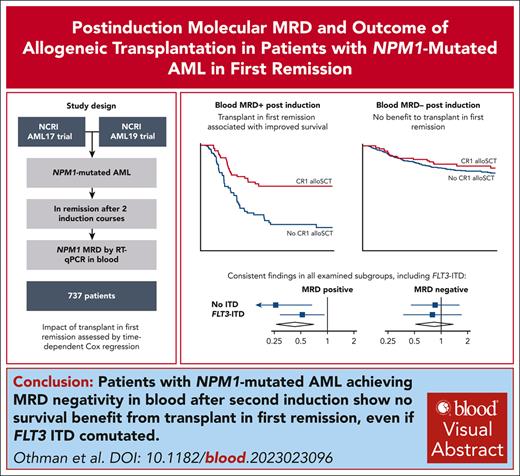

Molecular MRD after induction chemotherapy identifies patients with NPM1 AML who benefit from allogeneic transplant in first remission.

Patients achieving MRD negativity in blood after second induction show no survival benefit from CR1 transplant, even if FLT3-ITD comutated.

Visual Abstract

Selection of patients with NPM1-mutated acute myeloid leukemia (AML) for allogeneic transplant in first complete remission (CR1-allo) remains controversial because of a lack of robust data. Consequently, some centers consider baseline FLT3–internal tandem duplication (ITD) an indication for transplant, and others rely on measurable residual disease (MRD) status. Using prospective data from the United Kingdom National Cancer Research Institute AML17 and AML19 studies, we examined the impact of CR1-allo according to peripheral blood NPM1 MRD status measured by quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction after 2 courses of induction chemotherapy. Of 737 patients achieving remission, MRD was positive in 19%. CR1-allo was performed in 46% of MRD+ and 17% of MRD− patients. We observed significant heterogeneity of overall survival (OS) benefit from CR1-allo according to MRD status, with substantial OS advantage for MRD+ patients (3-year OS with CR1-allo vs without: 61% vs 24%; hazard ratio [HR], 0.39; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.24-0.64; P < .001) but no benefit for MRD− patients (3-year OS with CR1-allo vs without: 79% vs 82%; HR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.50-1.33; P = .4). Restricting analysis to patients with coexisting FLT3-ITD, again CR1-allo only improved OS for MRD+ patients (3-year OS, 45% vs 18%; compared with 83% vs 76% if MRD-); no interaction with FLT3 allelic ratio was observed. Postinduction molecular MRD reliably identifies those patients who benefit from allogeneic transplant in first remission. The AML17 and AML19 trials were registered at www.isrctn.com as #ISRCTN55675535 and #ISRCTN78449203, respectively.

Introduction

For patients with NPM1-mutated (NPM1mut) acute myeloid leukemia (AML) treated with curative intent, whether to perform allogeneic transplantation in first complete remission (CR1-allo) remains controversial, with significant variation internationally. Early studies indicated that CR1-allo only improved overall survival (OS) for patients with coexisting FLT3 internal tandem duplication (ITD), in particular with allelic ratio (AR) >0.5.1-5 These studies were performed before the development of sensitive molecular measurable residual disease (MRD) techniques, which have been shown to be strong predictors of outcome in NPM1mut AML.6-9 Nonrandomized data from the Acute Leukemia French Association (ALFA)-0702 suggested that of NPM1mut patients with FLT3-ITD, only those with poor early MRD response had improved OS with CR1-allo.7 This finding was supported by data from the Dutch-Belgian Hemato-Oncology Cooperative Group and the Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research (HOVON-SAKK)-132, where CR1-allo overcame the poor prognosis of MRD positivity.10,11 Nevertheless, many still consider the presence of FLT3-ITD to be an indication for CR1-allo in NPM1mut AML regardless of MRD.12,13

The current European LeukemiaNet (ELN) classification considers patients with NPM1mut and FLT3-ITD as intermediate risk regardless of AR, and suggests that MRD status may be used to inform CR1-allo selection, highlighting the need to more clearly define which patients benefit from transplant.14 Furthermore, there is a lack of robust evidence regarding the effect of CR1-allo in patients with ELN favorable-risk NPM1mut AML (ie, without FLT3-ITD) but with poor MRD response.

To clarify these issues, we performed a combined analysis of patients with NPM1mut AML in the United Kingdom National Cancer Research Institute AML17 and AML19 trials. These studies differed regarding patient selection for CR1-allo: in AML17, it was based largely on baseline risk factors; and in AML19, it was guided by MRD. Here, we analyze the effect of CR1-allo according to baseline clinical and molecular features and MRD status.

Study design

National Cancer Research Institute AML17 (ISRCTN55675535; April 2009 to December 2014) and AML19 (ISRCTN78449203; November 2015 to November 2020) were sequential prospective randomized trials of intensive chemotherapy for younger adults with newly diagnosed AML and high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome. Both mainly enrolled patients aged <60 years (including children in AML17 only), although older patients could enter if deemed fit. All patients underwent centralized testing for NPM1 and FLT3 mutations. Cytogenetic risk was assigned using Medical Research Council criteria.15

There were several therapeutic randomizations within each study (supplemental Methods, available on the Blood website). In AML17, patients with an FLT3 mutation could enter a randomization of the FLT3 inhibitor lestaurtinib; however, no benefit was seen.16 A randomization between MRD monitoring vs no monitoring was performed between June 2012 and January 2018.17

In AML17, NPM1mut patients were selected for CR1-allo using a validated risk score incorporating baseline factors and response to induction.18 Before June 2012, clinicians were not informed of MRD results, so that its prognostic value could be assessed. Thereafter, MRD results were reported directly to clinicians. In AML19, all NPM1mut patients underwent MRD testing after the first 2 chemotherapy cycles, and only patients testing MRD+ in peripheral blood (PB) post course 2 (PC2) were recommended for CR1-allo, regardless of baseline risk, based on findings from AML17.6

NPM1 MRD was performed by quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction at a central reference laboratory (supplemental Methods).6,19 Samples were requested after each chemotherapy course, then quarterly for 2 years from the end of treatment or transplant. Repeat samples were requested when results were concerning for molecular failure or technically suboptimal. After the initial phase of AML17, intervention was recommended for molecular relapse. Both trials were performed before the availability of midostaurin and FLT3-ITD MRD assays. Clinical and molecular data of patients with NPM1mut AML achieving complete remission (CR) or CR with incomplete hematological recovery from both trials were combined. Statistical methods are detailed in the supplemental Appendix.

Results and discussion

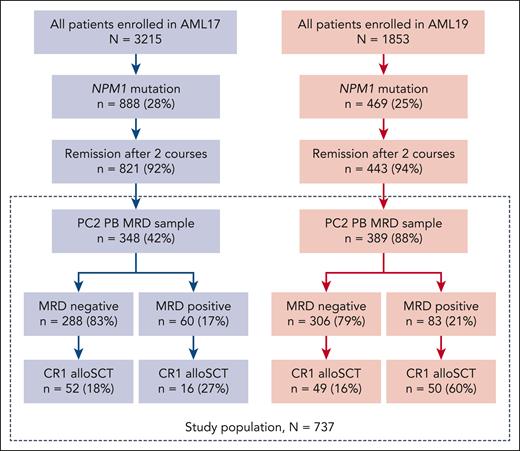

A total of 737 patients with NPM1mut AML who achieved CR/CR with incomplete hematological recovery and had a valid PC2 PB MRD result were included (Figure 1). Median age was 52 (range, 6-71) years, karyotype was normal in 87%, and 39% had FLT3-ITD (Table 1). PB PC2 MRD was positive in 143 of 737 patients (19%), including 60 of 348 patients (17%) in AML17 and 83 of 389 patients (21%) in AML19.

Flow diagram of patients included in the study from AML17 and AML19. CR1 alloSCT, allogeneic stem cell transplantation in first complete remission.

Flow diagram of patients included in the study from AML17 and AML19. CR1 alloSCT, allogeneic stem cell transplantation in first complete remission.

Characteristics of patients in the analysis, overall and by trial

| Characteristic . | Overall (N = 737) . | AML17 (N = 348) . | AML19 (N = 389) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (range), y | 52 (6-71) | 52 (6-70) | 52 (18-71) |

| Aged >60 y | 121 (16) | 70 (20) | 51 (13) |

| Female sex | 406 (55) | 187 (54) | 219 (56) |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL), median (IQR) | 9.00 (7.70-10.40) | 9.10 (7.90-10.30) | 8.80 (7.60-10.50) |

| White blood cell count (×109/L), median (IQR) | 22 (6-53) | 23 (9-49) | 20 (6-56) |

| Platelet count (×109/L), median (IQR) | 66 (39-110) | 66 (39-110) | 66 (39-111) |

| Bone marrow blast, median (IQR), % | 67 (40-85) | 70 (44-89) | 61 (38-80) |

| Prior myeloid malignancy | 30 (4.1) | 19 (5.5) | 11 (2.8) |

| Previous chemotherapy/radiotherapy | 11 (1.5) | 5 (1.4) | 6 (1.5) |

| Cytogenetic risk | |||

| Normal | 639 (87) | 304 (87) | 335 (86) |

| Intermediate | 71 (9.6) | 31 (8.9) | 40 (10) |

| Adverse | 9 (1.2) | 4 (1.1) | 5 (1.3) |

| Failed | 18 (2.4) | 9 (2.6) | 9 (2.3) |

| FLT3-ITD | 286 (39) | 139 (40) | 147 (38) |

| Low allelic ratio | 174 (61) | 75 (54) | 99 (68) |

| High allelic ratio | 111 (39) | 64 (46) | 47 (32) |

| FLT3 TKD | 121 (17) | 53 (15) | 68 (17) |

| Induction regimen | |||

| ADE | 99 (14) | 99 (30) | 0 (0) |

| CPX-351 | 2 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.5) |

| DA | 434 (60) | 236 (70) | 198 (51) |

| FLAG-Ida | 188 (26) | 0 (0) | 188 (48) |

| Gemtuzumab with induction | 378 (52) | 116 (34) | 262 (67) |

| Allogeneic transplant | |||

| Transplant in CR1 | 167 (23) | 68 (20) | 99 (25) |

| Transplant at other stage | 131 (18) | 72 (21) | 59 (15) |

| No transplant | 439 (60) | 208 (60) | 231 (59) |

| Characteristic . | Overall (N = 737) . | AML17 (N = 348) . | AML19 (N = 389) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (range), y | 52 (6-71) | 52 (6-70) | 52 (18-71) |

| Aged >60 y | 121 (16) | 70 (20) | 51 (13) |

| Female sex | 406 (55) | 187 (54) | 219 (56) |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL), median (IQR) | 9.00 (7.70-10.40) | 9.10 (7.90-10.30) | 8.80 (7.60-10.50) |

| White blood cell count (×109/L), median (IQR) | 22 (6-53) | 23 (9-49) | 20 (6-56) |

| Platelet count (×109/L), median (IQR) | 66 (39-110) | 66 (39-110) | 66 (39-111) |

| Bone marrow blast, median (IQR), % | 67 (40-85) | 70 (44-89) | 61 (38-80) |

| Prior myeloid malignancy | 30 (4.1) | 19 (5.5) | 11 (2.8) |

| Previous chemotherapy/radiotherapy | 11 (1.5) | 5 (1.4) | 6 (1.5) |

| Cytogenetic risk | |||

| Normal | 639 (87) | 304 (87) | 335 (86) |

| Intermediate | 71 (9.6) | 31 (8.9) | 40 (10) |

| Adverse | 9 (1.2) | 4 (1.1) | 5 (1.3) |

| Failed | 18 (2.4) | 9 (2.6) | 9 (2.3) |

| FLT3-ITD | 286 (39) | 139 (40) | 147 (38) |

| Low allelic ratio | 174 (61) | 75 (54) | 99 (68) |

| High allelic ratio | 111 (39) | 64 (46) | 47 (32) |

| FLT3 TKD | 121 (17) | 53 (15) | 68 (17) |

| Induction regimen | |||

| ADE | 99 (14) | 99 (30) | 0 (0) |

| CPX-351 | 2 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.5) |

| DA | 434 (60) | 236 (70) | 198 (51) |

| FLAG-Ida | 188 (26) | 0 (0) | 188 (48) |

| Gemtuzumab with induction | 378 (52) | 116 (34) | 262 (67) |

| Allogeneic transplant | |||

| Transplant in CR1 | 167 (23) | 68 (20) | 99 (25) |

| Transplant at other stage | 131 (18) | 72 (21) | 59 (15) |

| No transplant | 439 (60) | 208 (60) | 231 (59) |

Data are given as number (percentage) unless otherwise indicated.

ADE, cytarabine, daunorubicin, and etoposide; CR1, first complete remission; DA, daunorubicin and cytarabine; FLAG-Ida, fludarabine, cytarabine, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, and idarubucin; IQR, interquartile range; TKD, tyrosine kinase domain.

CR1-allo was performed in 167 of 737 patients (23%), 68 of 348 (20%) in AML17 and 99 of 389 (25%) in AML19. Of MRD+ patients, 16 of 60 (27%) received CR1-allo in AML17 compared with 50 of 83 (60%) in AML19 (where this was recommended). A total of 18% and 16% of MRD− patients in AML17 and AML19, respectively, received CR1-allo (Figure 1). Supplemental Table 1 shows patient characteristics by MRD, trial, and CR1-allo.

In AML17, patients who were MRD+ had poor outcomes, with 3-year cumulative incidence of relapse (CIR) of 84% (95% confidence interval [CI], 72%-92%) and OS of 25% (95% CI, 16%-39%).6 These outcomes improved in AML19, with 3-year CIR of 50% (95% CI, 38%-61%) and OS of 51% (95% CI, 41%-65%) (supplemental Figure 1). MRD− patients had excellent outcomes in both trials (3-year CIR, 33% [95% CI, 28%-39%] and 24% [95% CI, 20%-30%]; and OS, 75% [95% CI, 70%-80%] and 83% [95% CI, 79%-88%], in AML17 and AML19, respectively).

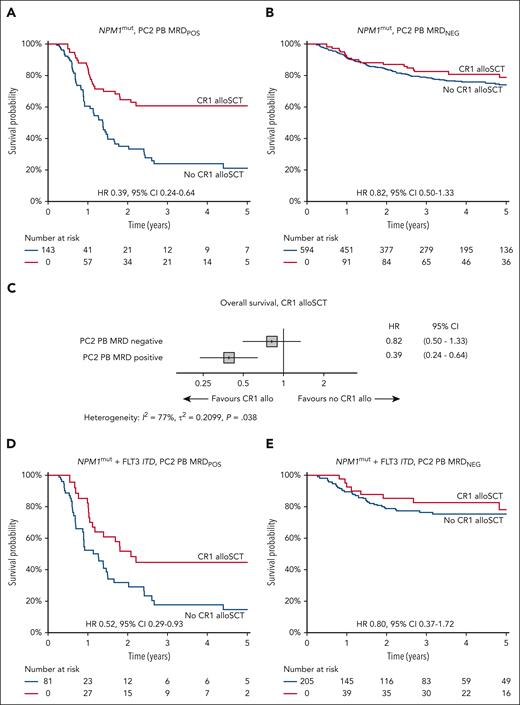

Combining both trials, for MRD− patients, we observed no difference in OS between patients who did or did not receive CR1-allo (3-year OS, 79% vs 82%; hazard ratio [HR], 0.82; 95% CI, 0.50-1.33; P = .4). In contrast, for MRD+ patients, OS was significantly improved in patients receiving CR1-allo (3-year OS, 61% vs 24%; HR, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.24-0.64; P < .001). Tests for heterogeneity of OS benefit for transplant according to MRD status were significant (I2 = 78%; P = .038) (Figure 2A-C). Overall, and for MRD− patients, there was no between-trial heterogeneity; however, the CR1-allo benefit for MRD+ appeared limited to AML19 (supplemental Figure 2). Characteristics of MRD+ patients receiving CR1-allo differed between trials (supplemental Table 1).

Overall survival based on receipt of CR1-allo. HRs represent the hazard of death associated with CR1-allo, from time-dependent Cox regression. (A) All NPM1 mutant AML, MRD positive (POS), in PB after 2 induction courses. Simon-Makuch plot of OS based on CR1-allo. (B) All NPM1 mutant AML, MRD negative (NEG), in PB after 2 induction courses. Simon-Makuch plot of OS based on CR1-allo. (C) Forest plot showing HR for death from CR1-allo (time-dependent Cox regression) within MRD subgroups, for all NPM1 mutant AML. (D) NPM1 mutant with FLT3-ITD AML, MRD POS, in PB after 2 induction courses. Simon-Makuch plot of OS based on CR1-allo. (E) NPM1 mutant with FLT3-ITD AML, MRD NEG, in PB after 2 induction courses. Simon-Makuch plot of OS based on CR1-allo. CR1 alloSCT, allogeneic stem cell transplantation in first complete remission.

Overall survival based on receipt of CR1-allo. HRs represent the hazard of death associated with CR1-allo, from time-dependent Cox regression. (A) All NPM1 mutant AML, MRD positive (POS), in PB after 2 induction courses. Simon-Makuch plot of OS based on CR1-allo. (B) All NPM1 mutant AML, MRD negative (NEG), in PB after 2 induction courses. Simon-Makuch plot of OS based on CR1-allo. (C) Forest plot showing HR for death from CR1-allo (time-dependent Cox regression) within MRD subgroups, for all NPM1 mutant AML. (D) NPM1 mutant with FLT3-ITD AML, MRD POS, in PB after 2 induction courses. Simon-Makuch plot of OS based on CR1-allo. (E) NPM1 mutant with FLT3-ITD AML, MRD NEG, in PB after 2 induction courses. Simon-Makuch plot of OS based on CR1-allo. CR1 alloSCT, allogeneic stem cell transplantation in first complete remission.

CR1-allo was associated with decreased relapse and improved relapse-free survival (RFS) in both MRD+ (3-year RFS, 50% vs 13%) and MRD− groups (3-year RFS, 76% vs 62%) (supplemental Figure 3). The 3-year transplant-related mortality was 12% in AML17 and 9% in AML19 (supplemental Figure 4). The discrepancy between RFS and OS in the MRD− group could be explained by a high rate of transplant after relapse (103 of 169 relapsed patients) in those without CR1-allo, resulting in 3-year postrelapse OS of 50% (supplemental Figure 3).

Of 286 patients with NPM1mutFLT3-ITD+ AML, 81 (28%) were PB PC2 MRD+, of whom 32 of 81 (40%) received CR1-allo (28% in AML17, 49% in AML19). Outcomes were improved in AML19, with 3-year CIR of 68% (95% CI, 52%-80%) vs 91% (95% CI, 73%-97%) and OS of 31% (95% CI, 19%-51%) vs 22% (95% CI, 12%-41%) for AML19 and AML17, respectively (supplemental Figure 1). Those who received CR1-allo had significantly better survival (3-year OS, 45% vs 18%; HR, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.29-0.93; P = .03) (Figure 2D) and reduced CIR (supplemental Figure 5). A total of 205 NPM1mutFLT3-ITD patients (70%) were PB PC2 MRD− and had favorable outcomes in both AML17 (3-year CIR, 37% [95% CI, 28%-46%]; OS, 75% [95% CI, 67%-84%]) and AML19 (3-year CIR, 27% [95% CI, 19%-37%]; OS, 80% [95% CI, 72%-89%]) (supplemental Figure 1). CR1-allo was performed in 20% (19% in AML17, 21% in AML19), with no survival benefit for transplant (3-year OS, 83% vs 76%; HR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.37-1.71; P = .6) (Figure 2E). There remained no benefit when restricted to those with high (>0.5) FLT3-ITD AR (HR, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.16-1.88; P = .30), and there was no heterogeneity between CR1-allo and AR (dichotomized at 0.5; P = .45) (supplemental Figure 3) or interaction with AR (as continuous variable; P > .9). There was no interaction between receipt of lestaurtinib, MRD status, and CR1-allo (supplemental Figure 6).

We could not identify any subgroups with OS benefit for transplant in MRD− patients, including patients with DNMT3A mutation and FLT3-ITD (supplemental Figure 7). There was no difference in OS between myeloablative and reduced-intensity conditioning for either MRD group (supplemental Figure 8). Posttransplant survival was higher for PC2 MRD− patients. PC2 MRD+ patients who became MRD− before CR1-allo had improved outcomes (supplemental Figure 9), with a higher proportion achieving this in AML19 (supplemental Table 1).

In this large cohort of patients with NPM1mut AML, we demonstrate that molecular MRD can be used to stratify decision-making concerning CR1-allo. Patients who achieved MRD negativity in the PB after induction course 2 had a low relapse risk; although CR1-allo was associated with improved RFS, we detected no OS benefit, including in patients with FLT3-ITD (regardless of AR). In contrast, for MRD+ patients, CR1-allo provided a significant survival benefit, particularly in AML19, where MRD was used to select patients for CR1-allo.

Our observations in the MRD− group are reminiscent of a recently reported randomized study of CR1-allo in intermediate-risk AML, where transplant improved RFS but not OS.20 Similar to that study, most MRD− patients in our cohort who relapsed subsequently received a transplant, offsetting the advantage of CR1-allo.

We highlight the lack of effective front-line FLT3 inhibitor use in both trials. However, it is likely that FLT3 inhibition would deepen MRD responses,21,22 further supporting the approach of deferring transplant in MRD− patients. Indeed, in the RATIFY study, even without MRD guidance, patients in the midostaurin arm who had NPM1 comutation did not appear to benefit from CR1-allo.23 Another limitation of our study is the lack of availability of FLT3-ITD MRD assays. Finally, these results cannot be extrapolated to flow cytometric MRD, and the low numbers of patients aged >60 years limits generalizability to this group.

To our knowledge, this is the largest study to examine the role of CR1-allo in NPM1mut AML, demonstrating that postinduction molecular MRD reliably identifies those patients who benefit from allogeneic transplant in first remission.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the clinicians, research nurses, and laboratory scientists who enrolled patients and provided samples for the AML17 and AML19 trials. The authors acknowledge and thank all the patients and families for their participation in, and support of, both trials.

AML17 (CRUK/08/025, A29806) and AML19 (C26822, A16484) received research support from Cancer Research UK, and AML19 received a research grant from Jazz Pharmaceuticals. J.O. was supported by fellowship grants from the Haematology Society of Australia and New Zealand and the RCPA Foundation.

Authorship

Contribution: J.O. coordinated the project, curated data, and performed statistical analysis; N.P., A.I., J.J., M.R., and S.D.F. coordinated and performed minimal residual disease analyses; I.T., S.J., and J. Canham provided trial coordination; A.G. undertook molecular analyses and coordinated patient samples; C.W.-B. performed statistical analysis and data curation; J. Cavenagh, P.K., C.A., H.B.O., U.M.O., M.D., A.B., R.D., and N.H.R. enrolled patients into the studies; N.H.R. and A.B. designed and were chief investigators of the clinical trials; M.D. was clinical coordinator and then cochief investigator of the clinical trials; and J.O., R.D., and N.H.R. drafted the manuscript, which was revised and approved by all authors.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: S.D.F. declares research funding from Jazz and Bristol Myers Squibb; and is on the speaker’s bureau of Jazz, Pfizer, and Novartis. U.M.O. declares honoraria from Pfizer, AbbVie, and Astellas. H.B.O. declares research funding from Jazz. R.D. declares research funding from AbbVie and Amgen; and consultancy for Astellas, Pfizer, Novartis, Jazz, Beigene, Shattuck, and AvenCell. N.H.R. declares research funding from Jazz and Pfizer; and honoraria from Pfizer, Servier, and Astellas. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Richard Dillon, Department of Medical and Molecular Genetics, Kings College London, Floor 8 Tower Wing, Guy’s Hospital, London SE1 9RT, United Kingdom; email: richard.dillon@kcl.ac.uk.

References

Author notes

J.O., N.P., R.D., and N.H.R. contributed equally to this study.

Access to deidentified data, and supporting documentation, is available via formal application to Cardiff University via the corresponding author.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal