In this issue of Blood, Cui et al dissect the single-cell and clonally resolved chromatin accessibility landscape of pediatric acute myeloid leukemia (pAML) and demonstrate the critical role of epigenetic dysregulation in these blood cancers.1

Myeloid malignancies are characterized by the clonal outgrowth of transformed healthy hematopoietic cells following the acquisition of various genetic alterations. Recent efforts have refined and improved our understanding of the genomic landscape and molecular categories of pAML, which are strongly associated with clinical outcomes.2 Overall, the prognosis for pAML remains poor as standard chemotherapy treatment is often accompanied by drug resistance of leukemic stem cells (LSCs) that retain long-term self-renewal capacity and ultimately fuel relapse.3 Understanding the molecular features of this resistance will thus be key to improving patient outcomes.

Over the last decade, single-cell genomics has been instrumental in showing the extent of heterogeneity within the same and across tumors.4 Much of our attention has focused on transcriptomic analysis, but upstream alterations of epigenetic features such as chromatin accessibility have been less intensively investigated. Although aberrant chromatin accessibility states have been reported in adult AML,5 little is known about chromatin accessibility states in pAML, particularly in the bone marrow where the disease initiates and relapses. Here, Cui et al report novel insights about the aberrant epigenetic kinetics of pAML by leveraging the mitochondrial single-cell assay for transposase-accessible chromatin with sequencing (mtscATAC-seq).6 In addition to chromatin accessibility profiling, mtscATAC-seq captures somatic mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) mutations,7 which the authors used as barcodes to resolve the clonal architecture and to track the cellular states and evolution of drug-resistant clones in pAML.

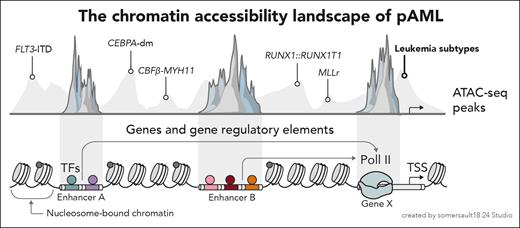

In their work, the authors performed mtscATAC-seq to characterize bone marrow mononuclear cells or CD34+ cells at diagnosis of a cohort of 28 pAML patients including 5 molecular subtypes. For 8 patients, samples at relapse made possible a paired longitudinal analysis. Leveraging the chromatin accessibility data, Cui et al described both subtype-specific epigenetic patterns and cellular compositions across the leukemic differentiation hierarchy (see figure). For example, the t(8;21) (RUNX1::RUNX1T1) and inv(16) (CBFβ-MYH11) subtypes showed significant enrichment of primitive and myeloid progenitor cells, with a similar epigenetic landscape likely explaining the shared cellular differentiation hierarchy. A similar correspondence was observed for the CEBPA-dm (CEBPA double mutation) and FLT3-ITD (FLT3 internal tandem duplication) subtypes, consistent with the notion that cellular identity is hardwired within a leukemia’s epigenetic profile.

Cui et al dissect the chromatin accessibility landscape across the molecular subtypes of pAML. TF, transcription factor; TSS, transcription start site.

Cui et al dissect the chromatin accessibility landscape across the molecular subtypes of pAML. TF, transcription factor; TSS, transcription start site.

Notably, in comparison with healthy donor cells, a prominent upregulation of innate immune signaling pathways (eg, neutrophil degranulation and myeloid leukocyte-mediated immunity) was commonly observed in malignant cells, in particular in more primitive populations, such as hematopoietic stem cell-like and multipotent progenitor-like (HSC/MPP-like) cells. To delineate the crucial clonal dimension, the authors leveraged evolutionary neutral somatic mtDNA mutations and identified that larger clones, likely due to having the best fitness, had higher innate immune activity scores. Importantly, innate immune activity scores were generally higher at relapse, suggesting a significant contribution of dysregulated innate immune signaling in conferring a competitive advantage. Based on these findings, the authors propose an innate immunity-based signature score (inScore), which was highly correlated with overall survival, and suggest that inScore may be a potential prognostic predictor for pAML.

Analysis of sample pairs at diagnosis vs postchemotherapy relapse further confirmed the clonal expansion of primitive HSC/MPP-like cells. This was associated with the dysregulation of key processes such as differentiation, vascular endothelial growth factor, and Wnt signaling pathways, which likely contribute to a differentiation block at the early stem or progenitor stages. More importantly, a significant reduction in chromatin accessibility across major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II genes, along with the respective increase or decrease of their negative or positive regulators across various pAML subtypes, was identified at relapse. This was again most pronounced in primitive cells, where MHC class II downregulation was highly correlated with increased clone size at relapse. Interestingly, the decrease in MHC class II molecule expression was only detected following chemotherapy treatment, strongly suggesting that immune escape mechanisms fuel clonal expansion leading to leukemia relapse.

To further explore the molecular features of drug resistance, the authors reconstructed the clonal kinetics in paired diagnosis-relapse samples by explicitly categorizing clones with different drug responses. For example, clones at diagnosis that were eliminated following chemotherapy were considered drugsensitive, and those repopulating the relapse were drug resistant. Differential chromatin accessibility and gene signature enrichment analysis showed the repression of T-cell regulation and MHC class II molecules, supporting the role of immune evasion in resistance. Drug-resistant clones displayed higher cell cycle gene activity, as well as signs of reduced metabolism and apoptotic signaling. Via a transcription factor motif analysis, the authors found 15 regulatory factors that were commonly enriched across different molecular subtypes, suggesting a shared resistance mechanism. In addition to SP1 and WT1, previously reported to be involved in drug resistance, the analysis identified EGR1 and DNMT1 as 2 novel regulators. This was supported by respective changes in chromatin accessibility of their target genes. For instance, EGR1 is a known regulator of ID1 expression, impacting cell cycle and senescence, and drug-resistant clones demonstrated increased accessibility of ID1 pathway genes (ie, CCND1, CDK4, STMN3) that likely promoted abnormal proliferation. Finally, Cui et al identified a subpopulation of HSC/MPP-like cells at diagnosis that was strongly associated with AML relapse, displayed a strong stemness phenotype, and activated Notch signaling, thereby indicating an LSC-like phenotype.

Overall, the study by Cui et al elegantly illustrates the integrative power of cell state and clonal analysis to explore disease evolution, which complements recent reports using single-cell techniques in pAML.8 The inScore showed prognostic power independent of currently used clinical scoring systems and may prove clinically valuable in the future. Additional work will be required to assess the role of the identified pathways in AML relapse. At a technical level, somatic mtDNA mutations provide an attractive means to resolve clonality, but it remains challenging to confidently cocapture nuclear DNA alterations that may be important drivers of disease progression and relapse.9 Further technological innovations will be key,10 together with the comprehensive integration of genomic landscapes2 with large-scale single-cell state analysis,4 to improve the prediction of features of disease progression, aid patient stratification, and identify novel treatment avenues.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The Broad Institute has filed for patents relating to the use of technologies to sequence mitochondrial DNA mutations in single cells, where L.S.L. is a named inventor (US patent applications 17/251,451 and 17/928,696). A.M.G. declares no competing financial interests.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal