Key Points

A single-cell and clonal resolution map of chromatin accessibility reveals aberrant epigenetic kinetics from diagnosis to relapse in pAML.

Innate immune signatures indicative of chemotherapy responses, and gene features in primary malignant cells relevant to relapse.

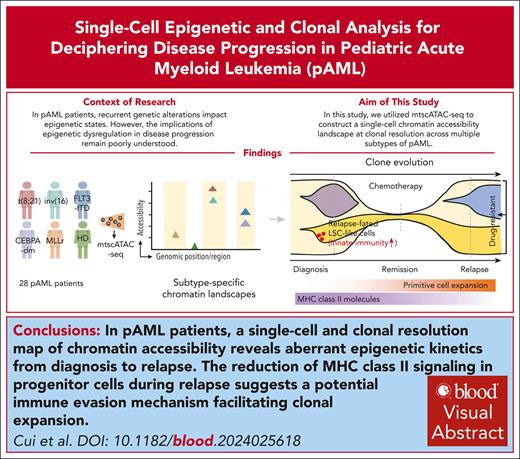

Visual Abstract

Pediatric acute myeloid leukemia (pAML) is a clonal disease with recurrent genetic alterations that affect epigenetic states. However, the implications of epigenetic dysregulation in disease progression remain unclear. Here, we interrogated single-cell and clonal level chromatin accessibility of bone marrow samples from 28 patients with pAML representing multiple subtypes using mitochondrial single-cell assay for transposase-accessible chromatin with sequencing, which revealed distinct differentiation hierarchies and abnormal chromatin accessibility in a subtype-specific manner. Innate immune signaling was commonly enhanced across subtypes and related to improved advantage of clonal competition and unfavorable prognosis, with further reinforcement in a relapse-associated leukemia stem cell–like population. We identified a panel of 31 innate immunity–related genes to improve the risk classification of patients with pAML. By comparing paired diagnosis and postchemotherapy relapse samples, we showed that primitive cells significantly reduced major histocompatibility complex class II signaling, suggesting an immune evasion mechanism to facilitate their expansion at relapse. Key regulators orchestrating cell cycle dysregulation were identified to contribute to pAML relapse in drug-resistant clones. Our work establishes the single-cell chromatin accessibility landscape at clonal resolution and reveals the critical involvement of epigenetic disruption, offering insights into classification and targeted therapies of patients with pAML.

Introduction

Pediatric acute myeloid leukemia (pAML) accounts for 20% of childhood leukemia and often has a poor prognosis with various molecular subtypes.1-3 Chemotherapy is the standard treatment but is often accompanied by drug resistance because of the resistant leukemia stem cells (LSCs), which may contribute to relapse.4,5 Although the genomic mutation spectrum in pAML has been well characterized, the epigenetic mechanisms underlying disease pathogenesis and relapse remain elusive.6-8 Previous studies have revealed that chromatin accessibility, an important epigenetic layer, regulates the function of hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) and subsequent lineage differentiation. Aberrant accessibility states have been implicated in the pathogenesis of hematological malignancies, including adult acute myeloid leukemia (AML).9-11 Although several pAML subtypes have recently been dissected to reveal the cellular diversity in peripheral blood cells and after transition after therapy,12,13 such information is currently unavailable for the bone marrow although this is where the disease initiates as well as relapses after chemotherapy.

AML is characterized by clonal evolution, with highly competitive clones propelling disease progression.14 Posttreatment relapse stems from drug-resistant clones. Thus, investigating clonal dynamics is crucial for understanding the mechanisms of pathogenesis and drug resistance.15 Single-cell analyses have recently unraveled the clonal diversity and evolution patterns of adult AML, however, understanding of the epigenetic mechanisms remains limited.16,17 Mitochondrial single-cell assay for transposase-accessible chromatin with sequencing (mtscATAC-seq) enables the parallel tracking of clonal relationships and nuclear chromatin accessibility at single-cell resolution,18,19 offering insights into the intricacies of clonal evolution and epigenetic dysregulation in hematological malignancies.

In this study, we established a chromatin accessibility landscape at single-cell and clonal resolution by performing mtscATAC-seq on a cohort of 28 patients with pAML and offered a web portal for open access (http://www.pzhulab.com/app/Pediatric_AML_mtscATAC). We identified subtype-specific chromatin alterations and common epigenetic dysregulation, implicating increased innate immune signaling at diagnosis, reduction of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II molecules, and key regulatory factors involved in postchemotherapy relapse. Importantly, epigenetic abnormalities provided prognostic power independent of currently used scoring systems, thus emphasizing the significance of epigenetic disruption underlying pAML evolution and providing insights for targeted therapies.

Materials and methods

Clinical samples

Bone marrow samples were obtained from 28 pediatric patients with AML across 5 distinct molecular subtypes. Aspirates were collected at diagnosis for 28 patients and at relapse for 8 patients. All patients underwent standard induction chemotherapy. Nonrelapse patients achieved remission for at least 5 years, and relapse was defined as bone marrow blasts of ≥5% or reappearance of blasts in the blood after complete remission. Bone marrow samples from 8 healthy pediatric donors were included as controls. All samples were obtained from the Blood Diseases Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences. Informed consent was obtained before sample collection.

Chromatin accessibility data analysis

The raw sequencing reads were demultiplexed using CellRanger-ATAC (version 2.0.0) “mkfastq” and subsequently aligned to the GRCh38 reference genome. Aligned data were then processed using the ArchR (version 1.0.1) pipeline20 for downstream analysis.

Statistics and reproducibility

Statistical analyses were conducted using R (version 3.6.1). Detailed information on specific statistical tests is provided in the supplemental Data (available on the Blood website) and figure legends for clarity.

Results

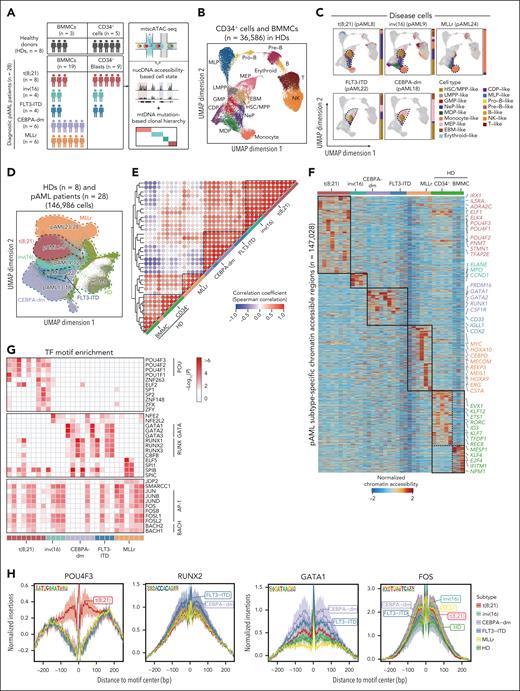

Single-cell chromatin accessibility profiling of multiple pediatric AML subtypes

To investigate the epigenetic basis of pAML at the single-cell clonal level, we used mtscATAC-seq to simultaneously profile nuclear chromatin accessibility and mitochondrial DNA sequences of bone marrow mononuclear cells (BMMCs) or CD34+ cells derived from 28 diagnostic patients with pAML and 8 pediatric healthy donors (HDs) (Figure 1A; supplemental Figure 1A-C; supplemental Tables 1 and 2). The patient cohort contained 5 molecular subtypes with specific mutations and varying clinical risk profiles including t(8;21) (RUNX1::RUNX1T1, n = 8), inv(16) (CBFβ-MYH11, n = 4), CEBPA-dm (CEBPA double mutation, n = 6), MLLr (MLL rearrangements, n = 6), and FLT3-ITD (FLT3 internal tandem duplication, n = 4). A total of 359 830 cells from patients with pAML and 36 586 cells from HDs were analyzed (supplemental Figure 1D-E). We reconstructed an epigenetic reference map of the hematopoietic hierarchy at homeostasis, which was represented by 16 distinct cell clusters (Figure 1B; supplemental Figure 2A-B).

Single-cell chromatin accessibility profiling reveals pAML subtype-specific epigenetic features. (A) Schematic overview of the experimental workflow. Bone marrow mononuclear cells (BMMCs) and CD34+ cells were isolated from patients with pAML including 5 molecular subtypes at diagnosis (n = 28) and healthy donors (HDs; n = 8) and subjected to mitochondrial single-cell assay for transposase-accessible chromatin with sequencing (mtscATAC-seq). (B) Uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) display of chromatin accessibility profiles of 36 586 single cells from HDs (BMMCs, n = 5; CD34+ HSPCs, n = 3). Dots represent individual cells, and colors indicate cluster identity. (C) Projection of disease cells onto the hematopoietic reference map in panel B. Gray dots denote cells from HDs, whereas colored dots represent cluster identities of malignant cells from patients. Bar plot showing the proportion of defined cell types in each patient with pAML. The dotted line highlights cell types significantly enriched in distinct subtypes, with a representative patient displayed for each subtype. (D) UMAP visualization of scATAC-seq data from all pAML samples (n = 28) and healthy individuals (n = 8) at single-cell level, with cells color-coded by molecular subtype. (E) Unsupervised hierarchical clustering of chromatin accessibility profiles across all patients including HD and pAML samples. (F) Heat map illustrating differentially accessible regions (n = 147 028) in each pAML subtype and HDs. The color represents normalized chromatin accessibility. Representative genes relevant to each subtype are displayed. (G) Enriched TF motifs based on differentially accessible regions in pAML. Top 5 motifs for each patient were displayed. Color represents significance of motif enrichment. (H) Footprints of subtype-specific TFs including POU4F3, RUNX2, GATA1, and FOS. Lines are colored by pAML subtypes. CDP, common dendritic cell progenitor; EBM, eosinophil/basophil/mast cell; GMP, granulocyte/macrophage progenitor; LMPP, lymphoid-primed multipotential progenitor; MDP, monocyte-dendritic cell progenitor; MEP, megakaryocyte/erythroid progenitor; MLP, multilymphoid progenitor; NeP, neutrophil progenitor; NK, natural killer cell; Pre-B, precursor B cell; Pro-B, progenitor B cell.

Single-cell chromatin accessibility profiling reveals pAML subtype-specific epigenetic features. (A) Schematic overview of the experimental workflow. Bone marrow mononuclear cells (BMMCs) and CD34+ cells were isolated from patients with pAML including 5 molecular subtypes at diagnosis (n = 28) and healthy donors (HDs; n = 8) and subjected to mitochondrial single-cell assay for transposase-accessible chromatin with sequencing (mtscATAC-seq). (B) Uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) display of chromatin accessibility profiles of 36 586 single cells from HDs (BMMCs, n = 5; CD34+ HSPCs, n = 3). Dots represent individual cells, and colors indicate cluster identity. (C) Projection of disease cells onto the hematopoietic reference map in panel B. Gray dots denote cells from HDs, whereas colored dots represent cluster identities of malignant cells from patients. Bar plot showing the proportion of defined cell types in each patient with pAML. The dotted line highlights cell types significantly enriched in distinct subtypes, with a representative patient displayed for each subtype. (D) UMAP visualization of scATAC-seq data from all pAML samples (n = 28) and healthy individuals (n = 8) at single-cell level, with cells color-coded by molecular subtype. (E) Unsupervised hierarchical clustering of chromatin accessibility profiles across all patients including HD and pAML samples. (F) Heat map illustrating differentially accessible regions (n = 147 028) in each pAML subtype and HDs. The color represents normalized chromatin accessibility. Representative genes relevant to each subtype are displayed. (G) Enriched TF motifs based on differentially accessible regions in pAML. Top 5 motifs for each patient were displayed. Color represents significance of motif enrichment. (H) Footprints of subtype-specific TFs including POU4F3, RUNX2, GATA1, and FOS. Lines are colored by pAML subtypes. CDP, common dendritic cell progenitor; EBM, eosinophil/basophil/mast cell; GMP, granulocyte/macrophage progenitor; LMPP, lymphoid-primed multipotential progenitor; MDP, monocyte-dendritic cell progenitor; MEP, megakaryocyte/erythroid progenitor; MLP, multilymphoid progenitor; NeP, neutrophil progenitor; NK, natural killer cell; Pre-B, precursor B cell; Pro-B, progenitor B cell.

To focus on the disease-specific epigenetic landscape, we first distinguished malignant cells from healthy-like cells in patients with pAML by integrating chromatin accessibility profiles from both patients and HDs (supplemental Figure 2C). To validate this classification, we identified ground-truth genomic variations in single cells, which were exclusively present in clusters composed of malignant cells (supplemental Figure 2D). Meanwhile, malignant cells showed chromosome copy number deletion and abnormal chromatin accessibility of leukemia-related genes (supplemental Figure 2E-H). Additionally, the proportion of classified malignant cells showed a significant positive correlation with the percentage of blast cells estimated by flow cytometry (supplemental Figure 2I). Together, these results supported our identification of AML malignant cells.

To determine the cellular compositions of disease cells across various pAML subtypes, we generated and explored a single-cell epigenome landscape representation (supplemental Figures 2C and 3A-B). We found that patients with t(8;21) and inv(16) exhibited comparable cellular components, both showing a significant enrichment of primitive cells and myeloid progenitor cells. In contrast, the MLLr subtype was primarily composed of monocyte-like cells, consistent with the M4 or M5 phenotype of patients with MLLr in the French-American-British (FAB) classification.21 Notably, unlike the findings in adult AML,22FLT3-ITD and CEBPA-dm subtypes with distinct chemotherapy responses showed similar cellular compositions.23,24 This was characterized by a higher proportion of primitive cells and erythroid progenitor-like cells, indicating shared lineage differentiation blockage but potentially divergent regulatory mechanisms underlying treatment response (Figure 1C; supplemental Figure 3A-B). Together, we profiled chromatin accessibility of single cells from various pAML subtypes and distinguished malignant cells, revealing diverse cellular compositions in patients with pAML.

pAML subtype-specific epigenetic patterns

Next, we examined the epigenetic heterogeneity among different pAML subtypes. Initial dimensionality reduction revealed subtype-specific clustering of patient-derived cells, indicative of distinct epigenetic profiles for each subtype (Figure 1D). This was further confirmed by individual-level uniform manifold approximation and projection visualization and correlation analysis (Figure 1E; supplemental Figure 3C). Specifically, patients with t(8;21) and inv(16) showed a similar epigenetic landscape that may contribute to a shared cellular differentiation hierarchy. This correspondence between epigenetic aberrations and cellular composition was also observed in CEBPA-dm and FLT3-ITD subtypes. Conversely, patients with MLLr exhibited a uniquely altered epigenome that was unrelated to any other subtypes.

We then identified differentially accessible features among distinct pAML subtypes and annotated these to subtype-specific genes (supplemental Table 3). For instance, the t(8;21) subtype showed unique chromatin accessibility for POU4F1 and POU4F3. Patients with t(8;21) and inv(16) shared features, such as increased accessibility of TFAP2E. Members of the AP-1 family, such as FOSL2, showed significantly elevated chromatin accessibility across all subtypes compared with HDs. Conversely, MEIS1 exhibited reduced chromatin accessibility in most subtypes, except for patients with MLLr and HDs. Additionally, patients with FLT3-ITD and CEBPA-dm mutations exhibited similar accessibility patterns with increased accessibility of GATA2, RUNX1, and PRDM16 (Figure 1F; supplemental Figure 3D). These accessibility features were consistent across various cell types, including HSC/multipotent progenitor cells (HSC/MPP)-like, lymphoid-primed multipotential progenitor–like, and megakaryocyte/erythroid progenitor–like cells (Figure 3E). The variations in chromatin accessibility align with previously reported gene expression patterns specific to certain AML subtypes,11,25,26 indicating that dysregulation is likely driven by abnormal epigenetic signals.

Transcription factors (TFs) are important regulators of intrinsic cellular processes during leukemogenesis.27,28 Therefore, we conducted TF binding motif enrichment analysis based on unique differentially accessible regions in pAML subtypes compared with HDs, which revealed subtype-specific enriched patterns. We observed significant enrichment of POU family binding motif, such as POU4F1, POU4F3, and POU1F1, in patients with t(8;21), particularly in HSC/MPP-like and neutrophil progenitor–like cells (Figure 1G; supplemental Figure 3F). Moreover, a common enrichment of AP-1 and BACH family motifs was observed across all subtypes. The AP-1 family might contribute to pAML and adult AML pathogenesis by altering immune regulation, cell proliferation, and apoptosis.11,29 Notably, patients with FLT3-ITD or CEBPA-dm mutations shared enrichment of RUNX and GATA motifs across multiple cell types (Figure 1G; supplemental Figure 3F). This enrichment, coupled with heightened chromatin accessibility of GATA2, likely played a role in biased differentiation toward the erythroid lineage in these 2 pAML subtypes. Footprinting analysis further confirmed the subtype-specific TF motif enrichment (Figure 1H). Overall, we reconstructed chromatin landscapes for different molecular subtypes of pAML, revealing subtype-specific epigenetic regulatory characteristics.

Activation of innate immune signaling in primitive cells promotes advantage of clonal competition

To understand the impact of epigenetic alterations on pAML pathogenesis, we performed Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of differentially accessible regions in patients. The GO pathways enriched for more accessible regions in pAML subtypes were mainly associated with innate immune processes, including neutrophil degranulation and myeloid leukocyte–mediated immunity (supplemental Figure 4A). Notably, innate immune signaling was exclusively elevated in pAML disease cells, whereas patient-derived healthy-like cells maintained normal levels (supplemental Figure 4B). Moreover, these aberrations were mainly observed in primitive cells, such as HSC/MPP-like and lymphoid-primed multipotential progenitor–like populations (Figure 2A; supplemental Figure 4A). We further evaluated the activity score of 334 genes related to innate immune signaling in primitive cells (supplemental Table 4) and observed a statistically significant increase across all subtypes compared with HDs (Figure 2B). Furthermore, the Toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling pathway, a crucial mediator for the induction of innate immunity,30,31 was activated within primitive cells (supplemental Figure 4C-D). These results suggest the involvement of leukemic primitive cells in innate immune response to extracellular stimulation in pAML, consistent with the recognized role of hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells (HSPCs) in inflammatory adaption.32,33

Innate immune signaling in primitive cells promotes advantage of clonal competition and predicts poor prognosis at diagnosis. (A) Box plot showing gene score of innate immune gene set (n = 334) in patients with pAML vs HDs among each cell type. N.S., not significant; ∗∗∗P < .001, Wilcoxon rank-sum test. (B) Violin plot (top) and heat map (bottom) showing gene score of innate immune gene set (n = 334) in primitive cells across distinct pAML subtypes and HDs. ∗∗∗P < .001, Wilcoxon rank-sum test. (C) Scatter plot showing the Spearman correlation (with a 95% confidence interval for the regression line) between the gene score of innate immune gene set (n = 334) and the clone size in pAML2 at diagnosis. The upper left corner displays the Spearman correlation coefficient (R) and the P value. (D) Gene score of innate immune gene set (n = 334) in each cell type compared between relapse and nonrelapse groups in different pAML subtypes. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01, Wilcoxon rank-sum test. (E) Forest plot showing significant prognostic value of inScore genes (n = 31) by analyzing RNA-sequencing data from TARGET pediatric AML cohort. Lines represent confidence intervals (95%). The dotted vertical line indicates hazard ratio of 1. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001, Wilcoxon rank-sum test. (F) Kaplan-Meier analysis of overall survival for pediatric patients with AML in the TARGET cohort based on the inScore signature (high inScore, n = 224; low inScore, n = 225). Log-rank test. (G) inScore of patients with pAML estimated by using microarray data from the TARGET cohort according to clinical risk categories: low risk (n = 99), intermediate risk (n = 144), and high risk (n = 52). ∗∗∗P < .001, Wilcoxon rank-sum test. (H) inScore in distinct pAML molecular subtypes estimated using microarray data from the TARGET cohort. (I) Forest plot showing hazard ratios from multivariate Cox regression analysis assessing the prognostic significance of the inScore as an independent metric for overall survival in the pediatric AML TARGET cohort. The median value of the inScore was used to define high and low groups. Hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals are presented. CDP, common dendritic cell progenitor; COG, children's oncology group; EBM, eosinophil/basophil/mast cell; FCGR, Fc gamma receptor; GMP, granulocyte/macrophage progenitor; LMPP, lymphoid-primed multipotential progenitor; MDP, monocyte-dendritic cell progenitor; MEP, megakaryocyte/erythroid progenitor; MLP, multilymphoid progenitor; NeP, neutrophil progenitor; NK, natural killer cell; NLR, NOD-like receptors; Pre-B, precursor B cell; Pro-B, progenitor B cell; RNA-seq, RNA sequencing; RNS, reactive nitrogen species; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

Innate immune signaling in primitive cells promotes advantage of clonal competition and predicts poor prognosis at diagnosis. (A) Box plot showing gene score of innate immune gene set (n = 334) in patients with pAML vs HDs among each cell type. N.S., not significant; ∗∗∗P < .001, Wilcoxon rank-sum test. (B) Violin plot (top) and heat map (bottom) showing gene score of innate immune gene set (n = 334) in primitive cells across distinct pAML subtypes and HDs. ∗∗∗P < .001, Wilcoxon rank-sum test. (C) Scatter plot showing the Spearman correlation (with a 95% confidence interval for the regression line) between the gene score of innate immune gene set (n = 334) and the clone size in pAML2 at diagnosis. The upper left corner displays the Spearman correlation coefficient (R) and the P value. (D) Gene score of innate immune gene set (n = 334) in each cell type compared between relapse and nonrelapse groups in different pAML subtypes. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01, Wilcoxon rank-sum test. (E) Forest plot showing significant prognostic value of inScore genes (n = 31) by analyzing RNA-sequencing data from TARGET pediatric AML cohort. Lines represent confidence intervals (95%). The dotted vertical line indicates hazard ratio of 1. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001, Wilcoxon rank-sum test. (F) Kaplan-Meier analysis of overall survival for pediatric patients with AML in the TARGET cohort based on the inScore signature (high inScore, n = 224; low inScore, n = 225). Log-rank test. (G) inScore of patients with pAML estimated by using microarray data from the TARGET cohort according to clinical risk categories: low risk (n = 99), intermediate risk (n = 144), and high risk (n = 52). ∗∗∗P < .001, Wilcoxon rank-sum test. (H) inScore in distinct pAML molecular subtypes estimated using microarray data from the TARGET cohort. (I) Forest plot showing hazard ratios from multivariate Cox regression analysis assessing the prognostic significance of the inScore as an independent metric for overall survival in the pediatric AML TARGET cohort. The median value of the inScore was used to define high and low groups. Hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals are presented. CDP, common dendritic cell progenitor; COG, children's oncology group; EBM, eosinophil/basophil/mast cell; FCGR, Fc gamma receptor; GMP, granulocyte/macrophage progenitor; LMPP, lymphoid-primed multipotential progenitor; MDP, monocyte-dendritic cell progenitor; MEP, megakaryocyte/erythroid progenitor; MLP, multilymphoid progenitor; NeP, neutrophil progenitor; NK, natural killer cell; NLR, NOD-like receptors; Pre-B, precursor B cell; Pro-B, progenitor B cell; RNA-seq, RNA sequencing; RNS, reactive nitrogen species; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

Next, we evaluated the impact of aberrant innate immune signaling at single-cell clonal level by performing mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) mutation–based clonal reconstruction (supplemental Figure 4E-F). Notably, confident mtDNA mutations were detected in all except 3 patients, with an average of 9 mtDNA mutations per patient used to define subclones (supplemental Table 2). These mtDNA mutations showed no correlation with the number of sequenced cells, and exhibited minimal recurrence (supplemental Figure 4G-H). Additionally, no definitive evidence linked these mutations to the etiology of pAML or any functional role, thus enabling an impartial examination of clonal evolution in pAML. We found that the accessibility of innate immunity–related genes gradually decreased as subclones reduced in size (Figure 2C; supplemental Figure 4I; supplemental Table 5). Consistent with previous reports in myelodysplastic syndrome,34,35 these findings suggest a significant contribution of dysregulated innate immunity in conferring a competitive advantage on malignant clones, leading to the development of hematological malignancies.

Elevated innate immune signaling predicts poor prognosis

To explore the association between innate immune signaling and prognosis, diagnostic patients with pAML were divided into relapse and nonrelapse groups based on chemotherapy responses (supplemental Figure 4J). The relapse group had significantly higher activity scores of innate immune genes at diagnosis across nearly all cell types (Figure 2D; supplemental Figure 4K). To independently verify this in a larger patient cohort, we analyzed pAML RNA sequencing data from the Therapeutically Applicable Research to Generate Effective Treatments (TARGET) database. We identified 52 genes, which comprised 18.5% of the innate immune gene set, showing a significant negative correlation with the overall survival of patients (supplemental Table 6). These results suggest that the elevated innate immune signaling is associated with an inferior outcome, highlighting its potential as a prognostic marker in patients with pAML.

We further defined an innate immune-associated gene activity score called the “inScore,” which comprises 31 genes with superior prognostic value (Figure 2E; supplemental Figure 4L; supplemental Table 7). Among these genes, CPB2 participates in the complement cascade, a fundamental aspect of the innate immune system.36CARD9 is required for the TLR signaling pathway and has been reported to promote lung cancer progression via interleukin-1β (IL-1β) mediation.37,38 Using Kaplan-Meier survival analysis, we observed that a higher inScore was correlated with reduced overall survival in the TARGET cohort (Figure 2F) and another independent pAML cohort (supplemental Figure 4M). Although higher clinical risk levels and adverse-risk alterations, such as FLT3-ITD and MLLr, were associated with higher inScore values (Figure 2G-H), multivariate analysis demonstrated a significant prognostic value of inScore, independent from the clinicopathological Children's Oncology Group (COG) risk stratification (Figure 2I). These results highlight the newly defined inScore, representing innate immune dysregulation, as a potential prognostic predictor for pAML.

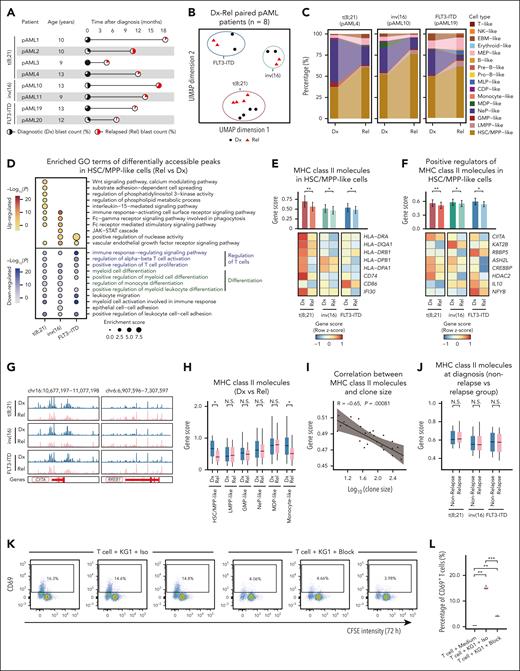

Reduced MHC-II gene activity facilitates immune evasion at postchemotherapy relapse

Postchemotherapy relapse presents a severe challenge in pAML therapy,39 yet the underlying regulatory mechanism remains incompletely understood. Given the association of innate immune signaling with outcomes, we first examined its correlation with relapse. We found that increased innate immune signaling at diagnosis was sustained at relapse, indicating this aberration was not a newly acquired feature responsible for relapse (supplemental Figure 5A). To determine the epigenetic features of pAML relapse after chemotherapy, we analyzed paired diagnosis and relapse samples across distinct subtypes (Figure 3A). Dimensionality reduction analysis revealed distinct epigenetic profiles between diagnosis and relapse in a subtype-specific manner (Figure 3B; supplemental Figure 5B). Furthermore, the expansion of primitive malignant cells at relapse, specifically for HSC/MPP-like cells, suggests a differentiation block at early stem/progenitor stages (Figure 3C; supplemental Figure 5C-D). This finding is consistent with recent reports in both pediatric and adult AML.13,15 Indeed, the differentially inaccessible regions in HSC/MPP-like cells during relapse were significantly enriched in cell differentiation pathways, indicating hindered differentiation. Additionally, these regions were enriched in pathways related to T-cell regulation, suggesting a potential weakening of adaptive immunity mediated by primitive malignant cells during relapse (Figure 3D). Moreover, the more accessible regions were enriched in pathways such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and wingless-related integration site (Wnt) signaling that had implications for therapeutic targeting and relapse prediction in patients with AML.40,41

MHC class II signaling downregulation mediated immune evasion at postchemotherapy relapse. (A) Overview of paired diagnostic-relapse (Dx-Rel) patients with pAML in distinct subtypes. Pie charts indicate clinical blast count, and the time of sample collections relative to diagnosis. (B) UMAP display of 8 paired diagnostic and relapse pAML samples across distinct subtypes based on top 25 000 variable peaks. Shape and color represent relapse state. (C) Bar plot illustrating the shift of cellular composition from diagnosis to relapse in distinct subtypes. (D) Top 10 enriched GO terms of differentially accessible regions in HSC/MPP-like cells between paired diagnostic and relapse samples. Color indicates the significance of enrichment. (E) Gene score of MHC class II molecules in HSC/MPP-like cells between diagnostic and relapse samples across distinct subtypes. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01, Wilcoxon rank-sum test. (F) Gene score of the positive regulators of MHC class II genes in HSC/MPP-like cells between diagnostic and relapse samples across distinct subtypes. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01, Wilcoxon rank-sum test. (G) Genome browser tracks illustrating chromatin accessibility for CIITA (a positive regulator for MHC class II genes) and RREB1 (a negative regulator for MHC class II genes) in diagnostic and relapse samples across distinct pAML subtypes. Each track shows merged pseudo-bulk ATAC-seq signal. (H) Gene score of MHC class II genes across various cell types between relapse and diagnosis samples. ∗P < .05, Wilcoxon rank-sum test. (I) Scatter plot showing the Spearman correlation (with a 95% confidence interval for the regression line) between the gene score of MHC class II genes and the clone size in pAML2 at relapse. The upper left corner displays the Spearman correlation coefficient (R) and the P value. (J) Gene score of MHC class II genes compared between relapse and nonrelapse groups in different pAML subtypes. Wilcoxon rank-sum test. (K) Flow cytometry was used to assess T-cell activation by measuring the percentage of CD4+ T cells positive for activation marker CD69. CD4+ T cells were cocultured with KG-1 cells for 72 hours, which had been preincubated with either anti–HLA-DR, -DP, -DQ blocking antibodies (KG1 + T cell + block) or an isotype control antibody (KG1 + T cell + Iso). Data are gated on live CD4+ T cells. Three independent experiments are performed. (L) Box plot showing percentage of CD69+ T cells in CD4+ T-cell population across different experimental conditions. CD4+ T cells were either cultured in medium alone (T cell + Medium) or coculturing with KG-1 cells (KG1 + T cell + Iso, KG1 + T cell + Block) for 72 hours. ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001, Wilcoxon rank-sum test. CDP, common dendritic cell progenitor; CFSE, carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester; Dx, diagnostic; EBM, eosinophil/basophil/mast cell; GMP, granulocyte/macrophage progenitor; LMPP, lymphoid-primed multipotential progenitor; MDP, monocyte-dendritic cell progenitor; MEP, megakaryocyte/erythroid progenitor; MLP, multilymphoid progenitor; NeP, neutrophil progenitor; NK, natural killer cell; Pre-B, precursor B cell; Pro-B, progenitor B cell; Rel, relapse.

MHC class II signaling downregulation mediated immune evasion at postchemotherapy relapse. (A) Overview of paired diagnostic-relapse (Dx-Rel) patients with pAML in distinct subtypes. Pie charts indicate clinical blast count, and the time of sample collections relative to diagnosis. (B) UMAP display of 8 paired diagnostic and relapse pAML samples across distinct subtypes based on top 25 000 variable peaks. Shape and color represent relapse state. (C) Bar plot illustrating the shift of cellular composition from diagnosis to relapse in distinct subtypes. (D) Top 10 enriched GO terms of differentially accessible regions in HSC/MPP-like cells between paired diagnostic and relapse samples. Color indicates the significance of enrichment. (E) Gene score of MHC class II molecules in HSC/MPP-like cells between diagnostic and relapse samples across distinct subtypes. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01, Wilcoxon rank-sum test. (F) Gene score of the positive regulators of MHC class II genes in HSC/MPP-like cells between diagnostic and relapse samples across distinct subtypes. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01, Wilcoxon rank-sum test. (G) Genome browser tracks illustrating chromatin accessibility for CIITA (a positive regulator for MHC class II genes) and RREB1 (a negative regulator for MHC class II genes) in diagnostic and relapse samples across distinct pAML subtypes. Each track shows merged pseudo-bulk ATAC-seq signal. (H) Gene score of MHC class II genes across various cell types between relapse and diagnosis samples. ∗P < .05, Wilcoxon rank-sum test. (I) Scatter plot showing the Spearman correlation (with a 95% confidence interval for the regression line) between the gene score of MHC class II genes and the clone size in pAML2 at relapse. The upper left corner displays the Spearman correlation coefficient (R) and the P value. (J) Gene score of MHC class II genes compared between relapse and nonrelapse groups in different pAML subtypes. Wilcoxon rank-sum test. (K) Flow cytometry was used to assess T-cell activation by measuring the percentage of CD4+ T cells positive for activation marker CD69. CD4+ T cells were cocultured with KG-1 cells for 72 hours, which had been preincubated with either anti–HLA-DR, -DP, -DQ blocking antibodies (KG1 + T cell + block) or an isotype control antibody (KG1 + T cell + Iso). Data are gated on live CD4+ T cells. Three independent experiments are performed. (L) Box plot showing percentage of CD69+ T cells in CD4+ T-cell population across different experimental conditions. CD4+ T cells were either cultured in medium alone (T cell + Medium) or coculturing with KG-1 cells (KG1 + T cell + Iso, KG1 + T cell + Block) for 72 hours. ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001, Wilcoxon rank-sum test. CDP, common dendritic cell progenitor; CFSE, carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester; Dx, diagnostic; EBM, eosinophil/basophil/mast cell; GMP, granulocyte/macrophage progenitor; LMPP, lymphoid-primed multipotential progenitor; MDP, monocyte-dendritic cell progenitor; MEP, megakaryocyte/erythroid progenitor; MLP, multilymphoid progenitor; NeP, neutrophil progenitor; NK, natural killer cell; Pre-B, precursor B cell; Pro-B, progenitor B cell; Rel, relapse.

HSPCs constitutively present antigens via MHC class II molecules, inducing T-cell responses for immune surveillance against transformed HSPCs.42 Remarkably, HSC/MPP-like cells showed a significant overall reduction in chromatin accessibility of MHC class II molecules (such as HLA-DPA1, HLA-DPB1, and HLA-DQA1) across various pAML subtypes during relapse (Figure 3E; supplemental Figure 5E). Moreover, the chromatin accessibility of positive and negative regulators governing MHC class II molecules43,44 showed a decrease and increase, respectively, in relapse HSC/MPP-like cells (Figure 3F-G; supplemental Figure 5F-G). This is suggestive of the epigenetic downregulation of the MHC class II genes. Specifically, HSC/MPP-like cells and a minor fraction of monocyte-like cells displayed a significant reduction in MHC class II molecule gene activity (Figure 3H). We further validated this finding using a recently published pAML single-cell RNA-sequencing data set,13 which included 22 paired diagnosis-relapse samples. Of these, 16 samples showed downregulation of MHC class II genes in primitive cells at relapse (supplemental Figure 5H). Additionally, flow cytometry analysis of HLA-DR protein expression in primitive cells from our cohort revealed a significant reduction at relapse in 4 of 6 patients for whom immunophenotyping data were available (eg, pAML1 and pAML20; supplemental Figure 5I). These results suggest that downregulation of MHC class II molecules promotes T-cell immune evasion in primitive cells, leading to their expansion after chemotherapy relapse. This mechanism parallels adult AML relapse after transplantation,43,45 indicating a common survival strategy for malignant cells in hematologic diseases.

Further analysis reveals a gradual decline in the gene activity of MHC class II molecule with the increase in clone size (Figure 3I), suggesting the potential contribution of reduced MHC class II gene activity to the ongoing expansion of malignant cells in pAML relapse after chemotherapy. To further confirm this, 14 patients with pAML with varying clone sizes were initially considered to distinguish dominant and nondominant clones (supplemental Figure 6A). For example, in relapse pAML2, clone no. 0 was designated as the dominant clone, whereas clones no. 19, 20, and 21 were classified as nondominant clones (supplemental Figure 6B-C). Dominant clones exhibited a significant decrease in gene activity of MHC class II molecules compared with nondominant clones (supplemental Figure 6D), with pathways associated with T-cell regulation and cytokine response signaling being enriched in less accessible features in dominant clones (supplemental Figure 6E). However, we observed no difference in the activity scores of MHC class II genes between the relapse and nonrelapse group at diagnosis across various subtypes (Figure 3J), indicating that alterations in MHC class II molecules are likely acquired during relapse after chemotherapy.

Next, we performed in vitro coculture experiments using AML cell lines and primary T cells to validate the role of MHC class II in modulating T-cell responses. Blocking MHC class II molecules on AML cells with neutralizing monoclonal antibody led to a significant reduction in T-cell activation and proliferation (Figure 3K-L; supplemental Figure 6F-G). Collectively, these results indicate that the downregulation of immunoregulatory MHC class II molecules impairs T-cell activation and proliferation. This impairment weakens the antileukemic immune response, and facilitates clonal competition and pAML relapse.

Identification of key regulators in drug-resistant clones

At diagnosis, a subset of clones is sensitive to chemotherapy and disappears after initial treatment, whereas residual clones may contribute to relapse.46 Discriminating drug-resistant and sensitive clones can improve our understanding of the mechanisms underlying relapse. To achieve this, we reconstructed the clonal kinetics at single-cell resolution in paired diagnosis-relapse pAML samples and explicitly identified clones with diverse drug responses (Figure 4A-B; supplemental Figure 7A). Clones at diagnosis eliminated by chemotherapy were identified as drug sensitive, whereas those repopulated at relapse were categorized as drug resistant (Figure 4C).

Identification of key regulators related to cell cycle dysregulation in drug-resistant clones. (A) Inference of clonal structure from somatic mtDNA mutations for pAML1 at diagnosis (left) and relapse (right). Each column represents a cell, and rows display detected mtDNA mutations. Color indicates heteroplasmy (% allele frequency). (B) Fish plot depicts the trajectory of clonal evolution inferred from mean heteroplasmy of mtDNA mutations from diagnosis to relapse for pAML1. (C) Diagram showing the discrimination of drug-resistant and drug-sensitive clones. (D) Top 10 enriched GO terms of differentially accessible regions in drug-resistant clones as compared with drug-sensitive clones. Color indicates the significance of enrichment. (E) Gene score of T-cell regulatory genes (n = 100) compared between drug-sensitive and drug-resistant clones. ∗P < .05, paired t test. (F) Heat map presenting the changes of gene score for MHC class II genes and their regulators in drug-resistant clones as compared with drug-sensitive clones. ∗P < .05, Wilcoxon rank-sum test. (G) Gene set enrichment analysis of cell cycle signaling in drug-resistant clones as compared with drug-sensitive clones. (H) Enriched motifs in drug-resistant clones compared with drug-sensitive clones. The commonly enriched regulatory factors are highlighted. Color represents enrichment significance, with the top 5 motifs selected for each patient. (I) Interaction network of key regulators in drug-resistant clones. Each node represents a regulator, and edges indicate interaction. The node size corresponds to the frequency of interaction, whereas the line thickness indicates the strength of the interaction. (J) Footprints of resistant clone-specific enriched motifs including SP1, DNMT1, and EGR1. Lines are color-coded for drug-resistant and drug-sensitive clones. (K) Heat map displaying the relative gene score of DNMT1-p15 pathway (top) and EGR1-ID1 pathway (bottom) in drug-resistant clones as compared with drug-sensitive clones. ∗P < .05, Wilcoxon rank-sum test. GTPase, guanosine triphosphate; ncRNA, non-coding RNA; NES, normalized enrichment score.

Identification of key regulators related to cell cycle dysregulation in drug-resistant clones. (A) Inference of clonal structure from somatic mtDNA mutations for pAML1 at diagnosis (left) and relapse (right). Each column represents a cell, and rows display detected mtDNA mutations. Color indicates heteroplasmy (% allele frequency). (B) Fish plot depicts the trajectory of clonal evolution inferred from mean heteroplasmy of mtDNA mutations from diagnosis to relapse for pAML1. (C) Diagram showing the discrimination of drug-resistant and drug-sensitive clones. (D) Top 10 enriched GO terms of differentially accessible regions in drug-resistant clones as compared with drug-sensitive clones. Color indicates the significance of enrichment. (E) Gene score of T-cell regulatory genes (n = 100) compared between drug-sensitive and drug-resistant clones. ∗P < .05, paired t test. (F) Heat map presenting the changes of gene score for MHC class II genes and their regulators in drug-resistant clones as compared with drug-sensitive clones. ∗P < .05, Wilcoxon rank-sum test. (G) Gene set enrichment analysis of cell cycle signaling in drug-resistant clones as compared with drug-sensitive clones. (H) Enriched motifs in drug-resistant clones compared with drug-sensitive clones. The commonly enriched regulatory factors are highlighted. Color represents enrichment significance, with the top 5 motifs selected for each patient. (I) Interaction network of key regulators in drug-resistant clones. Each node represents a regulator, and edges indicate interaction. The node size corresponds to the frequency of interaction, whereas the line thickness indicates the strength of the interaction. (J) Footprints of resistant clone-specific enriched motifs including SP1, DNMT1, and EGR1. Lines are color-coded for drug-resistant and drug-sensitive clones. (K) Heat map displaying the relative gene score of DNMT1-p15 pathway (top) and EGR1-ID1 pathway (bottom) in drug-resistant clones as compared with drug-sensitive clones. ∗P < .05, Wilcoxon rank-sum test. GTPase, guanosine triphosphate; ncRNA, non-coding RNA; NES, normalized enrichment score.

To unravel epigenetic alterations relevant to drug resistance, we determined differentially accessible regions between drug-resistant and drug-sensitive clones and performed GO enrichment analysis. We found that drug-resistant clones attenuated the T-cell–related regulatory pathway (Figure 4D-E), further supported by the decrease of MHC class II gene score (Figure 4F; supplemental Figure 7B). The regulators that govern MHC class II molecules exhibited an enhanced suppressive role, highlighting the immune evasion mediated by epigenetically silenced MHC class II signaling in drug-resistant clones (Figure 4F). Of note, drug-resistant clones exhibited higher levels of cell proliferation and cell cycle gene activity, but lower levels of metabolic processes and apoptotic signaling pathways (Figure 4D; supplemental Figure 7C-D). This is consistent with the role of abnormal cell cycle and metabolism in drug resistance.47,48 The gene set enrichment analysis also confirmed the presence of abnormal cell cycle signaling in drug-resistant clones (Figure 4G). These results collectively showed immune evasion and intensive cell cycle and altered metabolism pathways governed by epigenetic dysregulation in drug-resistant clones at relapse.

Next, we conducted motif enrichment analysis to identify the key regulatory factors responsible for drug resistance in each patient. Notably, 15 regulators were commonly enriched in all 7 patients from different pAML subtypes, representing a shared mechanism for resistance to chemotherapy among these subtypes (Figure 4H). SP1 and WT1 have been reported to be involved in drug resistance,49,50 supporting the accuracy of our clone-based strategy in capturing resistance-related epigenetic features. Additionally, we identified DNA methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1) and early growth response 1 (EGR1) as novel regulators that potentially contribute to drug resistance through protein–protein interactions (Figure 4I). This was further confirmed by analyzing interactions between these regulators and AML chemotherapeutic agents using the ingenuity pathway analysis (IPA) database (supplemental Figure 7E). Footprinting analysis verified the significant enrichment of these key regulators in drug-resistant clones (Figure 4J). To explore the impact of these regulators on drug-resistant clones, we assessed the chromatin accessibility of their downstream signaling molecules. We observed a significant reduction in gene activity of CDKN2B (p15) and CDKN2A (p16) in drug-resistant clones, indicating the involvement of the DNMT1-p15 axis in promoting cell proliferation in pAML. Furthermore, EGR1 can regulate cell cycle progression and affect cellular senescence by positively enhancing the gene activity of ID1 and ID3.51,52 We noticed a significant increase in the activity of genes related to the ID1 pathway, such as ID1, CCND1, CDK4, and STMN3, in drug-resistant clones (Figure 4K). Thus, the key regulators EGR1 and DNMT1 may promote the aberrant enhancement of proliferative capacity of these resistant clones, therefore, contributing to relapse.

Relapse-fated LSC-like subpopulation with increased innate immune signaling

It is known that a higher abundance of primitive cells is associated with worse outcomes in adult AML.53 To investigate whether preexisting primitive populations are related to subsequent pAML relapse at the clonal level, we categorized clones in diagnostic samples into relapse-associated and other clones (Dx-specific clone). We observed no significant differences in the distribution of HSC/MPP-like cells between these 2 types of clones at diagnosis (supplemental Figure 8A). Thus, we attempted to further cluster HSC/MPP-like cells into 8 distinct subpopulations (C1-C8) and reexamined their relevance to relapse (Figure 5A; supplemental Figure 8B-C). Notably, cluster C1 was significantly enriched in the relapse group compared with the nonrelapse group across diverse pAML subtypes (supplemental Figure 4J; Figure 5B; supplemental Figure 8D). Moreover, only C1 cells exhibited a specific clonal distribution pattern, being predominantly enriched in clones that were primarily responsible for relapse (Figure 5C; supplemental Figure 8E). These results imply that the C1 subpopulation plays a crucial role in driving relapse after chemotherapy.

Identification of relapse-fated subpopulation with elevated innate immune signaling. (A) UMAP plot illustrating the clustering of HSC/MPP-like cells (n = 77 945) from all patients with pAML at diagnosis. (B) Radar plot depicting the ratio of relative proportions of HSC/MPP-like subsets (C1 to C8) between relapse and nonrelapse groups across various pAML subtypes. (C) Bubble plot showing the ratio of observed to expected (Ro/e) values of C1 cluster in each clone type among patients with pAML (n = 7). Dot size represents the value of Ro/e, and the dot color represents logarithmic transformed adjusted P values (Benjamini-Hochberg correction). The symbol “/” indicates data not available. (D) EpiTrace age of HSC/MPP-like subsets from C1 to C8. (E) UMAP showing chromatin accessibility for SELL gene in HSC/MPP-like subsets. (F) LSC6 gene score in HSC/MPP-like subsets from C1 to C8. (G) Subset-specific accessible peaks (n = 26 437) from C1 to C8 with representative associated genes displayed (left). Zoom-in genome tracks display the chromatin accessibility of IL18R1 and the Notch signal gene NOTCH2NLA in HSC/MPP-like subsets (right). (H) UMAP showing chromatin accessibility for innate immunity–related gene CCL15 in HSC/MPP-like subsets. (I) Gene score of innate immune gene set (n = 334) within HSC/MPP-like subsets. GPCR, G-protein coupled receptor; LSC6, 6-gene leukemia stem cell signature.

Identification of relapse-fated subpopulation with elevated innate immune signaling. (A) UMAP plot illustrating the clustering of HSC/MPP-like cells (n = 77 945) from all patients with pAML at diagnosis. (B) Radar plot depicting the ratio of relative proportions of HSC/MPP-like subsets (C1 to C8) between relapse and nonrelapse groups across various pAML subtypes. (C) Bubble plot showing the ratio of observed to expected (Ro/e) values of C1 cluster in each clone type among patients with pAML (n = 7). Dot size represents the value of Ro/e, and the dot color represents logarithmic transformed adjusted P values (Benjamini-Hochberg correction). The symbol “/” indicates data not available. (D) EpiTrace age of HSC/MPP-like subsets from C1 to C8. (E) UMAP showing chromatin accessibility for SELL gene in HSC/MPP-like subsets. (F) LSC6 gene score in HSC/MPP-like subsets from C1 to C8. (G) Subset-specific accessible peaks (n = 26 437) from C1 to C8 with representative associated genes displayed (left). Zoom-in genome tracks display the chromatin accessibility of IL18R1 and the Notch signal gene NOTCH2NLA in HSC/MPP-like subsets (right). (H) UMAP showing chromatin accessibility for innate immunity–related gene CCL15 in HSC/MPP-like subsets. (I) Gene score of innate immune gene set (n = 334) within HSC/MPP-like subsets. GPCR, G-protein coupled receptor; LSC6, 6-gene leukemia stem cell signature.

Furthermore, we used EpiTrace,54 which quantifies the fraction of open clock-like loci from scATAC-seq data, to reconstruct the developmental trajectory of HSC/MPP-like subsets. The analysis revealed a differentiation trajectory from C1 to C8, with a progressive increase in EpiTrace age, suggesting that C1 represents the most primitive population (Figure 5D). This finding was further supported by a gradual loss of stemness features and a decrease in LSC6 score from C1 to C8, along with a significant negative correlation between EpiTrace age and LSC6 score55 (Figure 5E-F; supplemental Figure 8F-G), indicating an LSC-like state for C1. Additionally, we observed that C1 exhibited an activated Notch signaling pathway that is crucial for regulating stem cells and LSC self-renewal56,57 (Figure 5G). Notably, increased chromatin accessibility in genes associated with innate immune responses, such as IL18R1, S100A12, and GPR33, was observed within the C1 subpopulation (Figure 5G). The gene activity of innate immunity related genes, represented by CCL15 and CD44, showed the highest gene scores in C1, with a subsequent gradual decrease to C8 (Figure 5H-I; supplemental Figure 8H). Additionally, specific chromatin accessible regions of C1 significantly enriched in key hematopoietic-related TF motifs, including the RUNX family, GATA family, SPIB, and SPI1 (supplemental Figure 8I). Dysregulation of certain TFs such as RUNX2, GATA2, and SPI1 has been linked to the onset of AML and abnormal immune signals.58-61 Collectively, the pronounced LSC features and overactivated innate immune signaling in the relapse-fated C1 subpopulation provide potential targets for eradicating LSCs and preventing pAML relapse.

Discussion

Pediatric AML displays epigenetic dysregulation and subtype heterogeneity.13,62 The significant incidence of relapse after chemotherapy underscores the imperative to comprehend the underlying mechanisms to improve outcomes.63 By delineating the epigenetic landscapes and tracing clonal evolution across various pAML subtypes, we identified specific and common chromatin accessibility changes in distinct subtypes, clone levels, and disease stages. Our findings highlight epigenetic dysregulation in innate immune signaling, MHC class II molecules, and key regulatory factors, revealing important epigenetic characteristics in patients with pAML.

Dysregulation of innate immune signaling, an early hallmark in tumor pathogenesis,64,65 was commonly observed in diverse pAML molecular subtypes in this study. These abnormal signaling events potentially shape the interplay between malignant cells and the AML immune microenvironment, conferring a competitive advantage and fostering substantial proliferation of malignant clones.35,66 The overactivated innate immunity and inflammation have been previously reported in myelodysplastic syndrome,34 indicating a pervasive phenomenon in hematologic malignancies. Notably, our findings present, to our knowledge, the first evidence of epigenetic basis that such aberrant innate immune signaling is more prominent in malignant clones and primitive cells, particularly within the relapse-associated LSC-like subpopulation, suggesting a potential role for aberrant innate immune signaling in facilitating leukemia repopulation. Furthermore, our single-cell epigenomic data set allowed us to develop a new inScore with potential to improve the clinical classification of patients with pAML, guiding therapy for those currently classified as low risk. Therefore, targeting AP-1 TFs and TLR pathways holds promise in effectively reducing abnormal innate immune signaling. This therapeutic approach may eradicate malignant primitive cells, including LSC-like population, thereby preventing relapse and improving clinical outcomes.

MHC-II molecules play a crucial role in the adaptive immune response and are known to prevent the onset of HSC-derived leukemia by presenting tumor antigens.42,43 Primitive cells are enriched at relapse, potentially because of epigenetic downregulation of MHC-II molecules to mediate immune evasion after chemotherapy in pAML. A reduction of MHC-II signals from leukemia blasts has also been observed in relapse AML after allogeneic transplantation.45 This suggests a common route for immune evasion of malignant cells by dramatically narrowing the antigenic repertoire presented to T cells, thus facilitating the survival of malignant cells in relapse AML. We observed significant decrease in MHC class II gene activity in HSC/MPP-like cells, dominant clones, and drug-resistant clones, highlighting the cell-type- and clone-specific nature of immune evasion in pAML postchemotherapy relapse. It has been demonstrated that IL-1β inhibits CIITA transcription, thereby impeding interferon-γ–induced MHC-II expression.67 The activation of immune-related IL-1 signaling in primitive cells might hinder the expression of MHC-II molecules, thereby evading T-cell–mediated immune attack. Therefore, the sustained dysregulation of innate immune signaling from diagnosis to relapse may contribute to the immune evasion of primitive cells mediated by MHC-II molecules.

In summary, our work provides a comprehensive analysis of epigenetic and clonal evolution at single-cell resolution in a cohort of 28 patients with pAML across various subtypes. This enables to elucidate the intricate chromatin accessibility landscapes underlying disease progression. Importantly, we uncover the overactivation of innate immune signaling and downregulation of MHC-II molecules, revealing their clinical significance and providing new insights into the pathogenesis and relapse of pAML.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Qianfei Wang, Pengxu Qian, Haojian Zhang, Meng Zhao, and Hui Cheng for helpful discussions and suggestions.

P.Z. and B.G. were supported by the Newton Advanced Fellowship from the United Kingdom Academy of Medical Sciences and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82131430173). P.Z. was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2021YFA1102800), distinguished Young Scholars of Tianjin (21JCJQJC00070), the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences Initiative for Innovative Medicine (2023-12M-2-007, 2021-I2M-1-040), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82370119, 92374205).

Authorship

Contribution: B.C., L.A., and M.L. performed the experiments and analyzed the data; C.T., X.L., C.Z., and T.I. helped with data analysis; Y.Z., J.Z., Y.D., and X.Z. helped with sample preparation and interpretation of results; M.L., L.A., and Y.D. performed the validation experiments; B.C., L.A., M.L., Y.G., B.G., and P.Z. wrote the manuscript; W.Y., B.G., and P.Z. jointly conceived the project; and all authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Review statement: Berthold Göttgens is an Associate Editor of Blood. As an author of this article, he was recused by journal policy from any involvement in its peer review and he had no access to information regarding the peer review process.

The current affiliation for B.C. is Department of Medical Technology, Anhui Medical College, Hefei, Anhui, China.

Correspondence: Wenyu Yang, State Key Laboratory of Experimental Hematology, Institute of Hematology and Blood Diseases Hospital, 288 Nanjing Rd, Heping District, Tianjin 300020, China; email: yangwenyu@ihcams.ac.cn; Berthold Göttgens, Department of Hematology, Wellcome-MRC Cambridge Stem Cell Institute, University of Cambridge, Cambridge Biomedical Campus, Puddicombe Way, Cambridge CB2 0AW, United Kingdom; email: bg200@cam.ac.uk; and Ping Zhu, State Key Laboratory of Experimental Hematology, Institute of Hematology and Blood Diseases Hospital, 288 Nanjing Rd, Heping District, Tianjin 300020, China; email: zhuping@ihcams.ac.cn.

References

Author notes

B.C., L.A., M.L., and Y.D. contributed equally to this study.

The mtscATAC-seq data from healthy controls and patients with pAML have been deposited with the China National Genomics Data Center (accession number HRA006415).

Additional information will be provided on reasonable request to the corresponding authors, Wenyu Yang (yangwenyu@ihcams.ac.cn), Berthold Göttgens (bg200@cam.ac.uk), and Ping Zhu (zhuping@ihcams.ac.cn).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal