Key Points

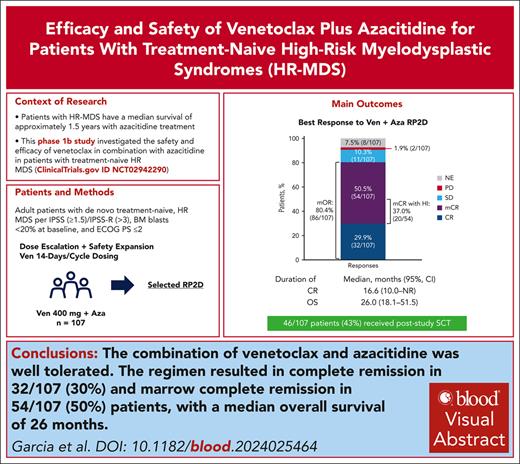

Venetoclax (14 days) + azacitidine regimen was well tolerated in patients with treatment-naive HR MDS, with no unexpected safety findings.

The regimen produced CR in 29.9% of patients, marrow CR in 50.5%, and 26-month median OS.

Visual Abstract

Outcomes are poor in patients with higher-risk myelodysplastic syndromes (HR MDS) and frontline treatment options are limited. This phase 1b study investigated safety and efficacy of venetoclax, a selective B-cell lymphoma 2 inhibitor, at the recommended phase 2 dose (RP2D; 400 mg for 14 days per 28-day cycle), in combination with azacitidine (75 mg/m2 for 7 days per 28-day cycle) for treatment-naive HR MDS. Safety was the primary outcome, and complete remission (CR) rate was the primary efficacy outcome. Secondary outcomes included rates of modified overall response (mOR), hematologic improvement (HI), overall survival (OS), and time to next treatment (TTNT). As of May 2023, 107 patients received venetoclax and azacitidine combination at the RP2D. Best response of CR or marrow CR was observed in 29.9% and 50.5% (mOR, 80.4%), respectively. Median OS was 26.0 months, with 1- and 2-year survival estimates of 71.2% and 51.3%, respectively. Among 59 patients with baseline red blood cell and/or platelet transfusion–dependence, 24 (40.7%) achieved transfusion independence on study, including 11 (18.6%) in CR. Fifty-one (49.0%) of 104 evaluable patients achieved HI. Median TTNT excluding transplantation was 13.4 months. Adverse events reflected known safety profiles for venetoclax and azacitidine, including constipation (53.3%), nausea (49.5%), neutropenia (48.6%), thrombocytopenia (44.9%), febrile neutropenia (42.1%), and diarrhea (41.1%). Overall, venetoclax plus azacitidine at the RP2D was well tolerated and had favorable outcomes. A phase 3 study (NCT04401748) is ongoing to confirm survival benefit of this combination. This trial was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as #NCT02942290.

Introduction

Myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) are a heterogeneous group of disorders in blood cell generation with an increased likelihood of transforming into acute myeloid leukemia (AML), especially in patients with higher-risk (HR) disease.1,2 Almost half (43%) of patients with MDS present with HR MDS.3 These patients have a median survival of approximately 1.5 years with standard-of-care treatment with the hypomethylating agent azacitidine.4 The majority of patients with MDS also present with ≥1 mutations, which affects the risk of progression to AML or death.1,5,6

The only curative treatment option for MDS is hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (SCT), but a minority of patients is eligible for this treatment.1,6 Eligibility for SCT depends on disease status, donor availability, and patient fitness, including performance status and comorbidities.7-9 Lower-intensity therapies, such as hypomethylating agents, may provide a path to SCT in patients with HR MDS.7,8 The AZA-001 phase 3 study demonstrated that azacitidine prolonged survival of patients with HR MDS ineligible for SCT to 24.5 vs 15 months with low-intensity conventional chemotherapy and best supportive care regimens.10 Azacitidine is currently the standard first-line treatment for patients with HR MDS.6 However, it has been challenging to reproduce the survival data observed in AZA-001, with subsequent meta-analyses as well as recent randomized HR MDS studies demonstrating a median overall survival (mOS) of 13 to 19 months with azacitidine.4,11-14

Combination strategies with an azacitidine backbone are a major focus of clinical research in HR MDS, with goals of prolonging remission duration, delaying time to progression, and improving survival.8,15 The combination of venetoclax, a selective BCL-2 inhibitor, with azacitidine is approved for adult patients with treatment-naive AML who are ineligible for intensive induction therapy because of age (≥75 years) or comorbidities.16 Preclinical data suggest synergy between venetoclax and azacitidine in the treatment of HR MDS.17

This ongoing open-label, multicenter, phase 1b study investigates the safety of combining venetoclax with azacitidine in patients with treatment-naive HR MDS. Under the original study protocol, patients in the treatment arms were to receive 400 or 800 mg venetoclax daily during 28-day cycles in combination with 75 mg/m2 azacitidine for 7 days per cycle. Of 10 patients exposed to the venetoclax and azacitidine combination, 2 developed fatal sepsis, resulting in a study redesign with the dose escalation portion consisting of a shorter duration of venetoclax (14 days per 28-day cycle) to improve safety and determine a recommended phase 2 dose (RP2D; supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood website). Here, in this first publication of results from a prospective clinical trial evaluating the combination of venetoclax and azacitidine in HR MDS, we report clinical data from patients treated with venetoclax for 14 daily doses per 28-day cycle and focus on safety and efficacy at the RP2D of 400 mg venetoclax with 75 mg/m2 azacitidine.

Methods

Patients and study design

Eligible patients were aged ≥18 years with no prior treatment for MDS, an International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS) score of ≥1.5 or revised IPSS (IPSS-R) score of >3, <20% bone marrow (BM) blasts at baseline per BM aspirate or biopsy, and an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS) score of ≤2. The phase 1b study consisted of successive enrollment of patients treated with 100 mg (dose escalation cohort 1), 200 mg (dose escalation cohort 2), or RP2D of 400 mg (dose escalation cohort 3 and safety expansion cohorts) oral venetoclax on days 1 to 14 of each planned 28-day cycle in combination with intravenous or subcutaneous azacitidine at 75 mg/m2 on days 1 to 7, or days 1 to 5, 8, and 9 of each cycle. The dose escalation portion of the study followed a Bayesian optimal interval design, and dose escalation rules were based on the cumulative number of patients who experienced a dose-limiting toxicity at a given dose level of venetoclax in combination with azacitidine. All patients who received ≥1 dose of study drug at the RP2D were included in the safety and efficacy analyses. Nadir blood counts with neutropenia or thrombocytopenia without clinical significance do not require an intracycle dose interruption or reduction because these are expected. However, at investigator’s discretion, treatment may be interrupted within a cycle for grade 4 febrile neutropenia or grade 4 platelet count decrease in conjunction with life-threatening hemorrhage. The protocol allowed for a delay in the initiation of next cycle and dose modification in case of hematologic toxicity (supplemental Tables 1 and 2). Venetoclax modifications included delay between cycles, or interruption within/between cycles, or duration reduction.

Prophylactic anti-infectives were required for all patients in the first cycle and strongly recommended for patients with grade ≥3 neutropenia thereafter. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor was allowed for the management of febrile neutropenia or neutropenic sepsis after blast clearance at the discretion of the investigator. Strong and moderate CYP3A inhibitors required venetoclax dose modifications and were excluded until the last venetoclax dose in cycle 1. During this period, patients were allowed to receive other antibiotics and antifungals that were not CYP3A inhibitors. Venetoclax dose modifications for coadministration with CYP3A inhibitors after completion of dose-limiting toxicity evaluation are shown in supplemental Table 3.

Patients were administered study treatment as long as they continued to benefit, or until unacceptable toxicity, physician decision, or withdrawal of consent, or if discontinuation was clinically indicated. Patients were then followed-up to record survival and subsequent anticancer therapies. Dosing after achieving complete remission (CR) was not evaluated. The study protocol and amendments, informed consent form, and other relevant study-related documents were reviewed and approved by a local institutional review board or independent ethics committee for each site before participation in the study. This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles founded by the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients or their legal representatives before enrollment.

End points and assessments

This study determined the RP2D and assessed the efficacy and safety of venetoclax in combination with azacitidine. The primary efficacy end point of the study was CR rate per modified International Working Group (IWG) 2006 criteria (see supplemental Methods).18 Key secondary end points included rates of marrow CR (mCR), modified overall response (mOR), hematologic improvement (HI), postbaseline red blood cell (RBC) and platelet transfusion independence, overall survival (OS), time to CR response, duration of CR, time to next treatment (TTNT), rate of transformation to AML, and time to AML transformation.

Disease response was assessed by investigators according to modified IWG 2006 criteria. Duration of CR was defined as days from achievement of CR to the earliest documentation of progressive disease, clinical disease progression during posttreatment follow-up, or death, whichever occurred first. The mOR rate was the proportion of patients with mOR (CR + partial remission [PR] + mCR) with best response at any time point during the study before poststudy treatment, regardless of HI status. Because no cases of PR were observed, mOR was based only on CR and mCR. OS was defined as the number of days from the date of first dose of study drug to the date of death from any cause; for patients who had not died, survival data were censored at the last known date the patient was alive before the data cutoff date.

Per protocol, transformation to AML was defined as ≥20% blasts18 in either the peripheral blood or BM after treatment initiation. TTNT was calculated as days from first dose of study drug to the start date of any new non–protocol-specified anticancer therapy or death from any cause, whichever occurred earlier. SCT immediately after study treatment was not considered a new non–protocol-specified anticancer therapy and was censored in the TTNT analysis.

The overall HI response rate was programmatically derived (not assessed by investigator) and defined as improvement in erythroid response, platelet response, or neutrophil response per modified IWG 2006 criteria among patients with baseline transfusion dependence (transfusion dependent during the 8 weeks before treatment initiation) or low baseline hemoglobin (<11 g/dL), platelet (<100 × 109/L), or absolute neutrophil counts (<1 × 109/L), respectively (see supplemental Methods). Postbaseline transfusion independence (TI) was defined as a period of ≥56 days during the evaluation period in which no RBC and/or platelet transfusion occurred. The evaluation period spanned from the date of first study drug dose to last dose of study drug +30 days, or 1 day before the date of progressive disease, 1 day before death, or 1 day before the initiation of poststudy treatment.

Presence of somatic mutations common to MDS was tested using Archer VARIANTPlex Core Myeloid Panel with 37 genes (see supplemental Methods).

Safety outcomes were monitored throughout treatment and were summarized for patients who received ≥1 dose of study treatment and up to 30 days after last dose of study treatment. Adverse events (AEs) were defined per National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 4.03 criteria.

Statistical analysis

A total of 100 patients were planned to be enrolled and dosed at the RP2D, providing 89% power to detect a 13% difference in CR rate relative to an historical azacitidine CR rate of 17%,4 with an α level of .05. Analysis of efficacy and safety was conducted among all patients who received ≥1 dose of study treatment at the RP2D.

Baseline characteristics represent the last value obtained for a given variable before first dose of study drug. Demographic data (eg, age) were summarized using descriptive statistics: mean, standard deviation, minimum, maximum, and range. Frequencies and percentages were computed for categorical data (eg, baseline ECOG PS).

End points for categorical variables were reported as a proportion of total patients with a response over the total number of evaluable patients, with a 95% confidence interval (CI) based on a binomial distribution (Clopper-Pearson exact method). Continuous variables (eg, time to AML transformation) were reported using descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, minimum, maximum, and range). Time-to-event analyses were conducted by Kaplan-Meier methodology and reported as median (95% CI).

Results

Patients

In the dose escalation part of the study, no dose-limiting toxicities were observed among patients treated with venetoclax 100 mg (n = 8), 200 mg (n = 9), and 400 mg (n = 8), therefore, venetoclax 400 mg for 14 days in combination with azacitidine was chosen as the RP2D for the safety expansion cohorts (Table 1).

Summary of TEAEs

| TEAE, n (%) . | Dose escalation cohort 1: venetoclax 100 mg (14 d/cycle) + azacitidine 75 mg/m2 (7 d/cycle) n = 8 . | Dose escalation cohort 2: venetoclax 200 mg (14 d/cycle) + azacitidine 75 mg/m2 (7 d/cycle) n = 9 . | Dose escalation cohort 3: venetoclax 400 mg (14 d/cycle) + azacitidine 75 mg/m2 (7 d/cycle) n = 8 . | All patients treated at RP2D (dose escalation + expansion cohorts): venetoclax 400 mg (14 d/cycle) + azacitidine 75 mg/m2 (7 d/cycle) N = 107 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any TEAE | 8 (100) | 9 (100) | 8 (100) | 107 (100) |

| Any grade 3/4 TEAE | 8 (100) | 9 (100) | 8 (100) | 101 (94.4) |

| TEAE possibly related to venetoclax | 8 (100) | 8 (88.9) | 6 (75.0) | 101 (94.4) |

| TEAE possibly related to azacitidine | 8 (100) | 9 (100) | 6 (75.0) | 99 (92.5) |

| TEAE leading to dose-limiting toxicities | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Any serious AE | 5 (62.5) | 7 (77.8) | 8 (100) | 73 (68.2) |

| Death | 6 (75.0) | 8 (88.9) | 3 (37.5) | 59 (55.1)∗ |

| TEAEs occurring in ≥20% of patients | ||||

| Constipation | 6 (75.0) | 8 (88.9) | 3 (37.5) | 57 (53.3) |

| Nausea | 3 (37.5) | 4 (44.4) | 4 (50.0) | 53 (49.5) |

| Neutropenia | 5 (62.5) | 4 (44.4) | 1 (12.5) | 52 (48.6) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 4 (50.0) | 7 (77.8) | 0 | 48 (44.9) |

| Febrile neutropenia | 2 (25.0) | 3 (33.3) | 5 (62.5) | 45 (42.1) |

| Diarrhea | 5 (62.5) | 5 (55.6) | 3 (37.5) | 44 (41.1) |

| Anemia | 3 (37.5) | 2 (22.2) | 2 (25.0) | 42 (39.3) |

| Vomiting | 2 (25.0) | 3 (33.3) | 3 (37.5) | 39 (36.4) |

| Hypokalemia | 3 (37.5) | 1 (11.1) | 3 (37.5) | 28 (26.2) |

| Fatigue | 1 (12.5) | 3 (33.3) | 1 (12.5) | 23 (21.5) |

| Grade 3/4 TEAEs occurring in ≥10% of patients | ||||

| Anemia | 2 (25.0) | 2 (22.2) | 2 (25.0) | 37 (34.6) |

| Febrile neutropenia | 2 (25.0) | 3 (33.3) | 5 (62.5) | 45 (42.1)† |

| Leukopenia | 1 (12.5) | 2 (22.2) | 0 | 20 (18.7) |

| Neutropenia | 5 (62.5) | 4 (44.4) | 1 (12.5) | 52 (48.6)† |

| Thrombocytopenia | 2 (25.0) | 7 (77.8) | 0 | 46 (43.0) |

| Pneumonia | 0 | 1 (11.1) | 1 (12.5) | 12 (11.2) |

| Neutrophil count decreased | 3 (37.5) | 1 (11.1) | 3 (37.5) | 16 (15.0)† |

| Platelet count decreased | 1 (12.5) | 1 (11.1) | 0 | 12 (11.2) |

| White blood cell count decreased | 1 (12.5) | 2 (22.2) | 2 (25.0) | 18 (16.8) |

| Serious AEs occurring in ≥5% of patients | ||||

| Febrile neutropenia | 2 (25.0) | 3 (33.3) | 5 (62.5) | 39 (36.4) |

| Pneumonia | 0 | 1 (11.1) | 1 (12.5) | 7 (6.5) |

| Cellulitis | 0 | 1 (11.1) | 0 | 6 (5.6) |

| Diverticulitis | 0 | 1 (11.1) | 0 | 6 (5.6) |

| Sepsis | 0 | 1 (11.1) | 0 | 6 (5.6) |

| TEAE, n (%) . | Dose escalation cohort 1: venetoclax 100 mg (14 d/cycle) + azacitidine 75 mg/m2 (7 d/cycle) n = 8 . | Dose escalation cohort 2: venetoclax 200 mg (14 d/cycle) + azacitidine 75 mg/m2 (7 d/cycle) n = 9 . | Dose escalation cohort 3: venetoclax 400 mg (14 d/cycle) + azacitidine 75 mg/m2 (7 d/cycle) n = 8 . | All patients treated at RP2D (dose escalation + expansion cohorts): venetoclax 400 mg (14 d/cycle) + azacitidine 75 mg/m2 (7 d/cycle) N = 107 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any TEAE | 8 (100) | 9 (100) | 8 (100) | 107 (100) |

| Any grade 3/4 TEAE | 8 (100) | 9 (100) | 8 (100) | 101 (94.4) |

| TEAE possibly related to venetoclax | 8 (100) | 8 (88.9) | 6 (75.0) | 101 (94.4) |

| TEAE possibly related to azacitidine | 8 (100) | 9 (100) | 6 (75.0) | 99 (92.5) |

| TEAE leading to dose-limiting toxicities | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Any serious AE | 5 (62.5) | 7 (77.8) | 8 (100) | 73 (68.2) |

| Death | 6 (75.0) | 8 (88.9) | 3 (37.5) | 59 (55.1)∗ |

| TEAEs occurring in ≥20% of patients | ||||

| Constipation | 6 (75.0) | 8 (88.9) | 3 (37.5) | 57 (53.3) |

| Nausea | 3 (37.5) | 4 (44.4) | 4 (50.0) | 53 (49.5) |

| Neutropenia | 5 (62.5) | 4 (44.4) | 1 (12.5) | 52 (48.6) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 4 (50.0) | 7 (77.8) | 0 | 48 (44.9) |

| Febrile neutropenia | 2 (25.0) | 3 (33.3) | 5 (62.5) | 45 (42.1) |

| Diarrhea | 5 (62.5) | 5 (55.6) | 3 (37.5) | 44 (41.1) |

| Anemia | 3 (37.5) | 2 (22.2) | 2 (25.0) | 42 (39.3) |

| Vomiting | 2 (25.0) | 3 (33.3) | 3 (37.5) | 39 (36.4) |

| Hypokalemia | 3 (37.5) | 1 (11.1) | 3 (37.5) | 28 (26.2) |

| Fatigue | 1 (12.5) | 3 (33.3) | 1 (12.5) | 23 (21.5) |

| Grade 3/4 TEAEs occurring in ≥10% of patients | ||||

| Anemia | 2 (25.0) | 2 (22.2) | 2 (25.0) | 37 (34.6) |

| Febrile neutropenia | 2 (25.0) | 3 (33.3) | 5 (62.5) | 45 (42.1)† |

| Leukopenia | 1 (12.5) | 2 (22.2) | 0 | 20 (18.7) |

| Neutropenia | 5 (62.5) | 4 (44.4) | 1 (12.5) | 52 (48.6)† |

| Thrombocytopenia | 2 (25.0) | 7 (77.8) | 0 | 46 (43.0) |

| Pneumonia | 0 | 1 (11.1) | 1 (12.5) | 12 (11.2) |

| Neutrophil count decreased | 3 (37.5) | 1 (11.1) | 3 (37.5) | 16 (15.0)† |

| Platelet count decreased | 1 (12.5) | 1 (11.1) | 0 | 12 (11.2) |

| White blood cell count decreased | 1 (12.5) | 2 (22.2) | 2 (25.0) | 18 (16.8) |

| Serious AEs occurring in ≥5% of patients | ||||

| Febrile neutropenia | 2 (25.0) | 3 (33.3) | 5 (62.5) | 39 (36.4) |

| Pneumonia | 0 | 1 (11.1) | 1 (12.5) | 7 (6.5) |

| Cellulitis | 0 | 1 (11.1) | 0 | 6 (5.6) |

| Diverticulitis | 0 | 1 (11.1) | 0 | 6 (5.6) |

| Sepsis | 0 | 1 (11.1) | 0 | 6 (5.6) |

Seven patients in survival follow-up experienced AEs resulting in death, including 1 patient with neutropenic sepsis leading to death that was possibly related to venetoclax, and 2 patients with neutropenic sepsis and death (1 patient each) that were possibly related to azacitidine treatment.

Eighty-three of 107 of patients (77.6%) at the RP2D experienced a grade 3/4 neutropenic event including any of the following: neutropenia, neutrophil count decreased, febrile neutropenia, and neutropenic sepsis.

As of the 31 May 2023 data cutoff, 107 patients received a median of 4 (range, 1-57) cycles of venetoclax plus azacitidine at the RP2D. The median follow-up was 31.9 months (range, 0.1-56.2 months). Patients were primarily male (n = 74, 69.2%) and White (n = 98, 92.5%), with a median age of 68 years (range, 26-87; Table 2). Most patients (n = 92, 86.0%) had high or very high risk by IPSS-R score, intermediate-2 or high IPSS score (n = 95/106, 89.6%; supplemental Table 4), and 63.6% of patients (n = 68) had intermediate, poor, or very poor IPSS-R cytogenetic risk. Sufficient Molecular International Prognosis Scoring System (IPSS-M) data are not available for this trial alone but will be presented in future pooled analyses. Most patients (n = 96, 89.7%) had >5% BM blasts, with a median of 11% (range, 1.0%-19.5%). Mutations identified in >10% of patients were in ASXL1, TP53, SRSF2, RUNX1, and TET2.

Patient demographics and disease characteristics

| Characteristic . | Venetoclax 400 mg (14 d/cycle) + azacitidine 75 mg/m2 (7 d/cycle) N = 107 . |

|---|---|

| Age, median (range), y | 68 (26-87) |

| <65, n (%) | 35 (32.7) |

| ≥65, n (%) | 72 (67.3) |

| ≥75, n (%) | 27 (25.2) |

| Male, n (%) | 74 (69.2) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| White | 98 (92.5) |

| Black or African American | 1 (0.9) |

| Asian | 7 (6.6) |

| Missing | 1 (0.9) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 4 (3.8) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 102 (96.2) |

| Missing | 1 (0.9) |

| ECOG PS, n (%) | |

| 0 | 56 (52.8) |

| 1 | 43 (40.6) |

| 2 | 7 (6.6) |

| Missing | 1 (0.9) |

| Time to treatment from MDS diagnosis, median (range), d | 61 (−3 to 2682)∗ |

| IPSS-R prognostic score, n (%)† | |

| Low | 1 (0.9) |

| Intermediate | 14 (13.1) |

| High | 40 (37.4) |

| Very high | 52 (48.6) |

| BM blast category, n (%) | |

| ≤5% | 11 (10.3) |

| >5 to ≤10% | 32 (29.9) |

| >10% | 64 (59.8) |

| BM blast count, median (range), % | 11.0 (1-19.5) |

| Baseline transfusion dependence, n (%) | |

| RBC | 56 (52.3) |

| Platelet | 18 (16.8) |

| RBC or platelet | 59 (55.1) |

| Eligible for SCT at study entry according to treating investigator, n (%) | 34 (31.8) |

| IPSS-R cytogenetic risk, n (%) | |

| Very good | 1 (0.9) |

| Good | 38 (35.5) |

| Intermediate | 35 (32.7) |

| Poor | 7 (6.5) |

| Very poor | 26 (24.3) |

| Baseline mutations, n (%)‡ | |

| No mutations detected | 21 (25.3) |

| ASXL1 | 29 (34.5) |

| TP53 | 20 (23.8) |

| SRSF2 | 19 (22.6) |

| RUNX1 | 18 (21.4) |

| TET2 | 15 (17.9) |

| Characteristic . | Venetoclax 400 mg (14 d/cycle) + azacitidine 75 mg/m2 (7 d/cycle) N = 107 . |

|---|---|

| Age, median (range), y | 68 (26-87) |

| <65, n (%) | 35 (32.7) |

| ≥65, n (%) | 72 (67.3) |

| ≥75, n (%) | 27 (25.2) |

| Male, n (%) | 74 (69.2) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| White | 98 (92.5) |

| Black or African American | 1 (0.9) |

| Asian | 7 (6.6) |

| Missing | 1 (0.9) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 4 (3.8) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 102 (96.2) |

| Missing | 1 (0.9) |

| ECOG PS, n (%) | |

| 0 | 56 (52.8) |

| 1 | 43 (40.6) |

| 2 | 7 (6.6) |

| Missing | 1 (0.9) |

| Time to treatment from MDS diagnosis, median (range), d | 61 (−3 to 2682)∗ |

| IPSS-R prognostic score, n (%)† | |

| Low | 1 (0.9) |

| Intermediate | 14 (13.1) |

| High | 40 (37.4) |

| Very high | 52 (48.6) |

| BM blast category, n (%) | |

| ≤5% | 11 (10.3) |

| >5 to ≤10% | 32 (29.9) |

| >10% | 64 (59.8) |

| BM blast count, median (range), % | 11.0 (1-19.5) |

| Baseline transfusion dependence, n (%) | |

| RBC | 56 (52.3) |

| Platelet | 18 (16.8) |

| RBC or platelet | 59 (55.1) |

| Eligible for SCT at study entry according to treating investigator, n (%) | 34 (31.8) |

| IPSS-R cytogenetic risk, n (%) | |

| Very good | 1 (0.9) |

| Good | 38 (35.5) |

| Intermediate | 35 (32.7) |

| Poor | 7 (6.5) |

| Very poor | 26 (24.3) |

| Baseline mutations, n (%)‡ | |

| No mutations detected | 21 (25.3) |

| ASXL1 | 29 (34.5) |

| TP53 | 20 (23.8) |

| SRSF2 | 19 (22.6) |

| RUNX1 | 18 (21.4) |

| TET2 | 15 (17.9) |

A protocol deviation resulted in enrollment of 1 patient without a documented diagnosis of MDS. A diagnosis was documented 3 days after treatment initiation.

IPSS-R risk groups overall score is calculated as the blast score + cytogenetics score + hemoglobin score + platelet score + absolute neutrophil count score. Overall risk score for low is >1.5 to 3.0, intermediate is >3.0 to 4.5, high is >4.5 to 6.0, and very high is >6.0.

Samples with sufficient material to be analyzed for mutations were available from 84 patients and were tested using a panel of 37 genes. Additional detected mutations included SF3B1 (9.5%), DNMT3A (8.3%), EZH2 (7.1%), IDH2 (6.0%), IDH1 (3.6%), and BCORL1 (1.2%).

As of the data cutoff, 101 of 107 patients (94.4%) treated at the RP2D had discontinued study treatment; the most common reasons for discontinuation were transplantation (n = 40, 37.4%), progressive disease (n = 26, 24.3%), and physician decision (n = 14, 13.1%; Table 3). Only 10 (9.3%) patients discontinued treatment because of an AE. Growth factor support was administered with filgrastim (36/107, 33.6%), lenograstim (5/107, 4.7%), and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (4/107, 3.7%).

Patient disposition

| . | Venetoclax 400 mg (14 d/cycle) + azacitidine 75 mg/m2 (7 d/cycle) N = 107 . |

|---|---|

| Remain on study treatment, n (%) | 6 (5.6) |

| Discontinued treatment, n (%) | 101 (94.4) |

| Primary reason for discontinuation, n (%) | |

| Transplant | 40 (37.4) |

| Progressive disease | 26 (24.3) |

| Physician decision | 14 (13.1) |

| AEs | 10 (9.3) |

| Withdrawal of consent | 5 (4.7) |

| Death | 3 (2.8) |

| Other | 3 (2.8) |

| . | Venetoclax 400 mg (14 d/cycle) + azacitidine 75 mg/m2 (7 d/cycle) N = 107 . |

|---|---|

| Remain on study treatment, n (%) | 6 (5.6) |

| Discontinued treatment, n (%) | 101 (94.4) |

| Primary reason for discontinuation, n (%) | |

| Transplant | 40 (37.4) |

| Progressive disease | 26 (24.3) |

| Physician decision | 14 (13.1) |

| AEs | 10 (9.3) |

| Withdrawal of consent | 5 (4.7) |

| Death | 3 (2.8) |

| Other | 3 (2.8) |

Responses to study treatment

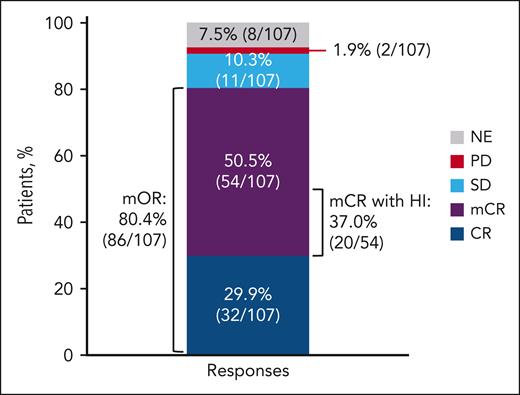

Among 107 patients treated with venetoclax plus azacitidine at the RP2D, 29.9% (n = 32; 95% CI, 21.4-39.5) achieved a best response of CR, and 50.5% (n = 54; 95% CI, 40.6-60.3) achieved a best response of mCR (Figure 1). Univariate and multivariate analyses for CR were not performed because of the number of patients with CR being too small to draw any meaningful conclusions from the results. Rate of mOR was 80.4% (n = 86; 95% CI, 71.6-87.4). No patients achieved a PR. Among 54 patients with a best response of mCR, 37.0% (20/54; 95% CI, 24.3-51.3) also achieved HI. The combined number of patients with response of CR or response of mCR with HI was 52 (48.6%). Two of 107 patients (1.9%; 95% CI, 0.2-6.6) had progressive disease as their best response.

Best response to treatment with venetoclax 400 mg + azacitidine. mOR = CR + mCR + PR. HI responders = 51 patients (28 patients with CR, 20 patients with mCR, and 3 patients with HI response only). No PR were reported. PD, progressive disease; SD, stable disease.

Best response to treatment with venetoclax 400 mg + azacitidine. mOR = CR + mCR + PR. HI responders = 51 patients (28 patients with CR, 20 patients with mCR, and 3 patients with HI response only). No PR were reported. PD, progressive disease; SD, stable disease.

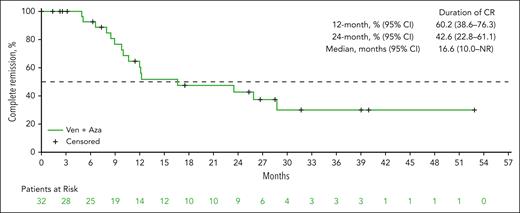

Median time to CR was 2.8 (range, 1.0-16.1) months. Among 75 patients who achieved mCR as their first response, 21 (28.0%; 95% CI, 18.2-39.6) eventually converted to CR, with a median time of 2.4 (range, 0.3-3.9) months. Median duration of CR was 16.6 months (95% CI, 10.0 to not reached [NR]; Figure 2). Responses were seen across all high-risk MDS (supplemental Figure 2). Of 20 patients with TP53 mutation, 5 achieved CR (25%; 95% CI, 8.7-49.1). Transformation to AML was reported in 13 of 106 evaluable patients (12.3%; 95% CI, 6.7-20.1), with a median time to transformation of 6.0 months (range, 0.7-29.3). When considering change in blasts from the baseline in addition to the blast level threshold for the AML transformation, 10 patients (9.4%; 95% CI, 4.6-16.7) had blast level of ≥20% blasts and a 50% relative increase from the baseline blast percentage.

Duration of CR. Duration of CR is defined as the number of days from the date of CR to the earliest documentation of progressive disease, clinical disease progression during posttreatment follow-up, or death of any cause, whichever occurred earlier. AZA, azacitidine; VEN, venetoclax.

Duration of CR. Duration of CR is defined as the number of days from the date of CR to the earliest documentation of progressive disease, clinical disease progression during posttreatment follow-up, or death of any cause, whichever occurred earlier. AZA, azacitidine; VEN, venetoclax.

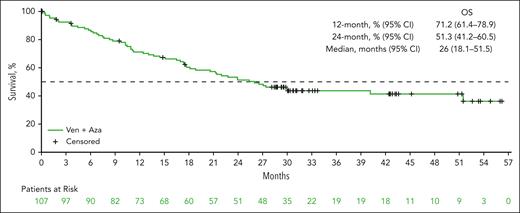

OS

The mOS was 26.0 months (95% CI, 18.1-51.5; Figure 3). The 12-month and 24-month survival estimates were 71.2% (95% CI, 61.4-78.9) and 51.3% (95% CI, 41.2-60.5), respectively. mOS was NR among patients who achieved a CR (95% CI, 24.0 to NR; supplemental Figure 3). Among patients who achieved an mCR with HI, mOS was 27.2 months (95% CI, 12.4 to NR). mOS of patients with TP53 mutation (11.2 months, 95% CI, 5.7-18.1; supplemental Figure 4A) was numerically shorter than in the overall patient population. Subgroups of patients with lower IPSS-R score and with higher percentage of BM blast at the baseline tended to have numerically longer mOS (supplemental Figure 4B-C). Both univariate and multivariate analyses of OS indicated that ECOG PS and baseline BM blast category may influence OS, although the interpretation of these results should be cautioned because of small sample size.

OS. OS was defined as the number of months from the date of the first dose of study drug to the date of death of any cause. If a patient had not died, the data were censored at the date the patient was last known to be alive on or before the cutoff date. AZA, azacitidine; VEN, venetoclax.

OS. OS was defined as the number of months from the date of the first dose of study drug to the date of death of any cause. If a patient had not died, the data were censored at the date the patient was last known to be alive on or before the cutoff date. AZA, azacitidine; VEN, venetoclax.

TI and HI

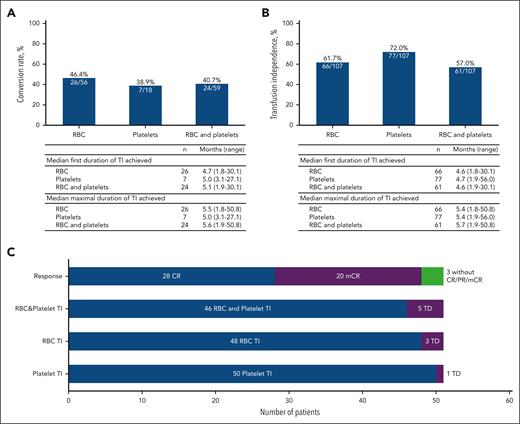

Among 59 of 107 patients who were RBC and/or platelet transfusion dependent at baseline, 24 (40.7%; 95% CI, 28.1-54.3) converted to TI on study treatment, including 11 (18.6%; 95% CI, 9.7-30.9) who also achieved CR (Figure 4). Among 48 patients with TI at baseline, 37 (77.1%; 95% CI, 62.7-88.0) remained independent after baseline. The median maximum duration of postbaseline TI among 24 patients who converted to RBC and platelet TI during treatment was 5.6 months (range, 1.9-50.8). Among 104 patients evaluable for HI, 51 (49%; 95% CI, 39.1-59.0) patients achieved overall HI, including 28 of 51 (54.9%; 95% CI, 40.3-68.9) who achieved CR, 20 of 51 (39.2%; 95% CI, 25.8-53.9) patients with mCR, and 3 of 51 (5.9%; 95% CI, 1.2-16.2) patients with HI response only. Among 51 patients with HI, 46 (90.2%; 95% CI, 78.6-96.7) patients also achieved both RBC and platelet postbaseline TI, 48 (94.1%; 95% CI, 83.8-98.8) patients achieved only RBC TI, and 50 (98.0%; 95% CI, 89.6-100) patients achieved only platelet TI, regardless of transfusion status at baseline.

TI and HI. (A) TD-to-TI conversion rate. (B) Postbaseline TI (includes 24 patients who converted to TI from baseline TD, and 37 patients who remained TI from baseline). (C) Postbaseline HI and response (n = 51). TD, transfusion dependence.

TI and HI. (A) TD-to-TI conversion rate. (B) Postbaseline TI (includes 24 patients who converted to TI from baseline TD, and 37 patients who remained TI from baseline). (C) Postbaseline HI and response (n = 51). TD, transfusion dependence.

Subsequent treatment

Of 107 patients, 62 received subsequent treatment after discontinuing study treatment. The immediate next treatment included SCT in 42 (39.3%; 95% CI, 30.0-49.2) patients after a median of 4.8 months (range, 1.4-16.8). Among the 42 patients who had SCT as the immediate next treatment, best responses to study treatment before SCT included CR in 16 (38.1%; 95% CI, 23.6-54.4) patients, mCR in 22 (52.4%; 95% CI, 36.4-68.0) patients, and stable disease in 4 patients (9.5%; 95% CI, 2.7-22.6). Thirty-five percent of patients (7/20) who achieved mCR with HI and 44.1% (15/34) of patients with mCR without HI underwent SCT. The median TTNT excluding SCT was 13.4 months (95% CI, 9.7-17.7). Four (3.7%; 95% CI, 1.0-9.3) other patients received additional nonprotocol treatment after study treatment, followed by SCT. Sixteen (15.0%; 95% CI, 8.8-23.1) patients received other nonprotocol treatment without SCT. For patients who had additional nonprotocol treatment before SCT (n = 4), best response to venetoclax plus azacitidine was CR in 1 patient and stable disease in 3. mOS was NR for patients who underwent SCT (supplemental Figure 4D) and subgroups of patients who received this curative treatment after achieving CR or mCR during the study (supplemental Table 5). Twenty patients whom investigators considered ineligible for SCT at time of enrollment underwent SCT during the study, including 17 who received SCT immediately after study treatment. For all 46 patients (43%; 95% CI, 33.5-52.9) who underwent SCT, median number of cycles of venetoclax and azacitidine received before SCT was 3 (range, 1-22). For patients who did not undergo SCT (61/107; 57%; 95% CI, 47.1-66.5), median cycles of study treatment was 5 (range, 1-57).

Overall, 29 patients received additional MDS-directed therapies after study treatment (reasons included: n = 4 before SCT, n = 9 after SCT, and n = 16 for lack of response or discontinuation from study treatment and without SCT). Subsequent treatments that were administered to >1 patient, excluding transplant conditioning regimens, included azacitidine (n = 13, 12.1%), decitabine (n = 5, 4.7%), and venetoclax (n = 3, 2.8%).

Safety

All patients treated at the RP2D (N = 107) experienced ≥1 treatment-emergent AE (TEAE) during treatment, and 94.4% of patients experienced ≥1 grade 3/4 TEAE (Table 1). The most common TEAEs of any grade were constipation (n = 57, 53.3%), nausea (n = 53, 49.5%), neutropenia (n = 52, 48.6%), thrombocytopenia (n = 48, 44.9%), febrile neutropenia (n = 45, 42.1%), and diarrhea (n = 44, 41.1%). A similar proportion of patients experienced TEAEs possibly related to venetoclax (94.4%) and azacitidine (92.5%). Venetoclax dose reductions for any reason occurred in 56 (52.3%) patients, and the median dose intensity was 76.9%. Seventy-two patients (67.3%) experienced ≥1 TEAE leading to venetoclax dose interruption. Dose interruptions within a cycle and/or between cycles occurred in 96 patients (89.7%), with >2 interruptions occurring in 51 patients (47.7%).

Grade 3/4 TEAEs were primarily hematologic. At baseline, grade ≥3 neutropenia or thrombocytopenia was reported in 59.8% (n = 64) and 38.3% (n = 41) of patients, respectively. Grade 3/4 TEAEs reported in ≥10% of patients included neutropenia (n = 52, 48.6%), thrombocytopenia (n = 46, 43.0%), febrile neutropenia (n = 45, 42.1%), anemia (n = 37, 34.6%), leukopenia (n = 20, 18.7%), white blood cell count decreased (n = 18, 16.8%), neutrophil count decreased (n = 16, 15.0%), platelet count decreased and pneumonia (n = 12 each, 11.2% for each), and lymphocyte count decreased (n = 11, 10.3%). Less than 20% of patients experienced grade 3/4 gastrointestinal TEAEs, the most common of which were colitis, diarrhea, and gastrointestinal hemorrhage in 2 patients each.

Seventy-three patients (68.2%) experienced ≥1 serious AE (SAE). The most common SAEs were febrile neutropenia (n = 39, 36.4%); pneumonia (n = 7, 6.5%); and cellulitis, diverticulitis, and sepsis (n = 6 each, 5.6% each). Infections (including the above) were reported in 43 patients (40.2%). Forty-six patients (43.0%) experienced SAEs considered to possibly be related to venetoclax or azacitidine.

Fifty-nine patients (55.1%) died during the study. Cause of death was disease progression in 23 patients (21.5%) and was reported as other reasons in 36 patients (33.6%). Only 1 death (0.9%) was considered to be because of a TEAE possibly related to venetoclax, and 2 deaths (1.9%) because of TEAEs possibly related to azacitidine. The 30-day mortality and 60-day mortality rates after the first dose were 3.7% and 6.5%, respectively.

Mean hemoglobin levels improved on study treatment, whereas platelet counts and neutrophil counts for patients treated at the RP2D demonstrated cyclical changes in relation to the timing of the study treatment (supplemental Figures 5-7).

Discussion

This phase 1b study of venetoclax plus azacitidine in patients with HR MDS identified 400 mg venetoclax for 14 days per 28-day cycle in combination with azacitidine at 75 mg/m2 for 7 days per cycle as the RP2D. Patients treated at the RP2D achieved an mOR rate of 80%, with responses across a broad patient population, including those with high or very high-risk MDS and poor/very poor cytogenetic risk. The mOS of 26 months and a CR duration of 16.6 months appear more favorable than the historical outcomes observed with azacitidine monotherapy, including mOS of 24.5 months in the AZA-001 study and 13 to 19 months in recent, randomized studies of HR MDS.4,10-12,14 Although OS remains the standard measure of clinical benefit among the efficacy outcomes in HR MDS, CR has previously been shown to be correlated with OS.4 The apparent synergism of azacitidine with venetoclax may be related to downregulation of myeloid cell leukemia 1 or upregulation of the proapoptotic protein NOXA by azacitidine,19 priming malignant myeloid cells for apoptosis induction by venetoclax.20

Currently, SCT is the only potentially curative treatment available for MDS and is recommended as front-line therapy for those eligible with excess BM blasts (especially if >10%) and with a suitable donor7,21; cytoreduction before SCT is generally considered useful.7 However, many patients are ineligible for SCT. Use of SCT has increased among patients aged ≥60 years,22 but patient age remains a barrier to receipt of SCT,23 despite evidence that comorbidities, disease status, and performance status are better predictive of outcomes.23,24 In the current study, 43% of patients who were treated with venetoclax and azacitidine combination at the RP2D proceeded to SCT, which is higher than other reported SCT rates.21 Among 54 patients in this study who achieved mCR on study drug, 22 patients underwent SCT. Standard-of-care therapies have demonstrated no clear outcome benefit with mCR in absence of HI, leading to removal of this response criteria from the IWG 2023. However, the clinical impact of mCR in the absence of HI after modern therapy such as venetoclax and azacitidine combination therapy may still warrant some consideration, as this study demonstrated a reduction of disease burden, and 44.1% (15/34) of patients with mCR without HI enabled bridging to a treatment (SCT) with curative intent.

Delaying disease progression and death are primary treatment goals in HR MDS. The current study had a relatively low rate of MDS-to-AML transformation of 12%, compared with the historical rate of 40% for patients with HR MDS.25 HI and associated TI are also critical quality-of-life goals for patients.26,27 In this study, 57% of patients (61/107) were transfusion independent after baseline, including 24 of 59 patients (41%) who were transfusion dependent at baseline, whereas HI was achieved in 49% of evaluable patients (51/104). These results are consistent with those of previous reports26 and support a role for venetoclax and azacitidine treatment in enabling TI and corresponding improvements in quality of life.

The safety profiles of both venetoclax and azacitidine are well established.16,28 No dose-limiting toxicities were observed during the dose escalation phase of this study in patients with HR MDS, and no unexpected TEAEs were reported for patients treated at the RP2D of 400 mg venetoclax for 14 days per cycle in combination with azacitidine. The most common TEAEs were hematologic and gastrointestinal (the latter predominantly low grades). Any-grade neutropenia was reported in 49% of patients, and serious AEs included infections in 40% of patients. These events were manageable following per-protocol dose modifications, specified prophylaxis (anti-infectives were required for all patients in the first treatment cycles, and recommended thereafter for patients with grade ≥3 neutropenia), and standard interventions.

In this phase 1b trial, we lacked a control group, limiting conclusions of efficacy. Furthermore, sample size limitations restricted more comprehensive investigations of efficacy in patient subgroups with historically poor prognosis, such as patients with poor or very poor cytogenetic risk. Additional research is warranted to determine whether the findings from this analysis hold in a broader population.

In conclusion, the results from this phase 1b study provide evidence of tolerability and efficacy of venetoclax plus azacitidine treatment at the RP2D for patients with treatment-naive HR MDS. The phase 3 trial VERONA (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04401748) is ongoing to investigate the survival benefit of this treatment regimen for patients with newly diagnosed HR MDS.

Acknowledgments

Medical writing assistance for this manuscript was provided by Rohina Rubicz of Bio Connections LLC, and funded by AbbVie. Venetoclax is being developed in collaboration between AbbVie and Genentech.

This study was funded by AbbVie and Genentech.

AbbVie and Genentech participated in the design, study conduct, analysis, and interpretation of data, as well as the writing, review, and approval of the publication. No honoraria or payments were made for authorship.

Authorship

Contribution: J.S.G., U.P., O.O., S.F., C.Y.F, U.B., M.A.J., D.N., M.R.B., P.P., B.C., J.P., and G.G-M. were responsible for the conception and design of the study; J.S.G., U.P., O.O., S.F., C.Y.F, U.B., M.A.J., D.N., M.R.B., P.P., and G.G-M. were responsible for trial management; J.S.G., U.P., O.O., S.F., C.Y.F, U.B., M.A.J., D.N., M.R.B., P.P., and G.G-M. were responsible for recruitment and treatment of patients. All authors had access to study data and contributed to data interpretation, manuscript editing, and critical review of the manuscript, and approved the final draft of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: J.S.G. serves in an advisory role for AbbVie, Astellas, Bristol Myers Squibb, Genentech, and Servier, and also received institutional funding from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Genentech, New Wave, Prelude, and Pfizer. U.P. serves as member of board of directors or advisory committee for Bristol Myers Squibb and MDS Foundation; and received honoraria, consultancy, and research funding from Bristol Myers Squibb, Novartis, Jazz, Syros, Servier, Silence Therapeutics, and Takeda; consultancy and research funding from Curis, Geron, and Janssen Biotech; research funding from Bristol Myers Squibb, BeiGene, FibroGen, Roche, and Merk; reports consultancy with AbbVie; and reports honoraria from Celgene. O.O. served on the advisory board for Bristol Myers Squibb/Celgene, DSMB-Kymera Therapeutics, Novartis, Rigel, Servier, and Taiho; received research funding from AbbVie and AstraZeneca; and received institutional research support from Agios, Aprea, Astex, Bristol Myers Squibb/Celgene, CTI, Daiichi Sankyo, Incyte, Janssen, Kartos, Novartis, NS-Pharma, and Oncotherapy Sciences. S.F. served on the board of directors or advisory committees for AbbVie, Astellas, Amgen, Ariad, Bristol Myers Squibb/Celgene, Pfizer; and received research funding from Bristol Myers Squibb, Pfizer and Amgen and honoraria from AbbVie, Pfizer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Gilead/Kite and Amgen. C.Y.F. has received honoraria from AbbVie, Amgen, BeiGene, Bristol Myers Squibb, Jazz, Novartis, Pfizer, and Servier; has acted as a consultant/adviser for AbbVie, Amgen, Astellas Pharma, Bristol Myers Squibb, Jazz, Novartis, Pfizer, and Servier; and has received research funding from Amgen, Astellas, and Jazz. U.B. served on advisory board for Bristol Myers Squibb, AbbVie, Incyte, Rigel, Servier, Vincerx, Immunogen, and Sumitomo; received research support from AbbVie, Incyte, Jazz, and Novartis; and served on the independent data monitoring committee for Takeda. M.A.J. received honoraria from Gilead and research support from Jazz. D.N. received research funding from Affimed and Pharmaxis, and honoraria from Bristol Myers Squibb. M.R.B. received institutional research support from AbbVie; Ascentage; Astellas, Kite (a Gilead company), Kura, and Takeda. P.P. served on advisory board for Bristol Myers Squibb/Celgene, Servier, and AbbVie; received honoraria from Jaxx and Astellas; and received research support from AbbVie, Jazz, and Astellas. G.K. is an employee with Genentech and may hold stock or other options in Roche. G.G.-M. received research support from AbbVie and Genentech. B.C., H.W., D.H., J.P. are employees with AbbVie and may hold stock or other options.

Correspondence: Jacqueline S. Garcia, Department of Medical Oncology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Harvard Medical School, 450 Brookline Ave, Boston, MA 02215; email: jacqueline_garcia@dfci.harvard.edu.

References

Author notes

AbbVie is committed to responsible data sharing regarding the clinical trials we sponsor. This includes access to anonymized, individual, and trial-level data (analysis data sets), as well as other information (eg, protocols, clinical study reports, or analysis plans), as long as the trials are not part of an ongoing or planned regulatory submission. This includes requests for clinical trial data for unlicensed products and indications. These clinical trial data can be requested by any qualified researchers who engage in rigorous, independent, scientific research and will be provided after review and approval of a research proposal, statistical analysis plan, and execution of a data sharing agreement. Data requests can be submitted at any time after approval in the United States and Europe and after acceptance of this manuscript for publication. The data will be accessible for 12 months, with possible extensions considered. For more information on the process or to submit a request, visit the following link: https://vivli.org/ourmember/abbvie/, then select “Home.”

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal