Abstract

Abciximab is a new antiplatelet therapeutic in ischemic cardiovascular disease. The drug, chimeric Fab fragments of a murine monoclonal antibody (MoAb) (c7E3), blocks GP IIb-IIIa function. However, its capacity to reach all receptor pools in platelets is unknown. Electron microscopy and immunogold labeling were used to localize abciximab in platelets of patients receiving the drug for up to 24 hours. Studies on frozen-thin sections showed that c7E3 Fab, in addition to the surface pool, also labeled the surface-connected canalicular system (SCCS) and -granules. Analysis of gold particle distribution showed that intraplatelet labeling was not accumulative and in equilibrium with the surface pool. After short-term incubations of platelets with c7E3 Fab in vitro, gold particles were often seen in lines within thin elements of the SCCS, some of which appeared in contact with -granules. Little labeling was associated with Glanzmann’s thrombasthenia platelets, confirming that the channels contained bound and not free c7E3 Fab. Endocytosis of abciximab in clathrin-containing vesicles was visualized by double staining and constitutes an alternative mechanism of transport. The remaining free pool of GP IIb-IIIa was evaluated with the MoAb AP-2; flow cytometry showed it to be about 9% on the surface of nonstimulated platelets but 33% on thrombin-activated platelets. The ability of drugs to block all pools of GP IIb-IIIa and then to be associated with secretion-dependent residual aggregation must be considered when evaluating their efficiency in a clinical context.

GP IIb-IIIa COMPLEXES (INTEGRIN αIIbβ3), are not only constituents of the surface membrane of platelets, they are also widely present in internal membrane compartments, including those of the surface-connected canalicular system (SCCS) and the α-granules.1-4 The complexes mediate platelet aggregation through the linking of adjacent platelets by adhesive proteins.5 Some soluble agonists such as adenosine diphosphate (ADP) initiate aggregation without directly inducing the secretory mechanism of platelets. In contrast, strong agonists such as thrombin additionally promote expression of the internal pool of GP IIb-IIIa at the platelet surface.6 New-generation antiplatelet drugs based on the concept of blocking the final common step of platelet aggregation inhibit the binding of adhesive proteins to the GP IIb-IIIa complex.7 These drugs include monoclonal antibodies (MoAbs) such as abciximab, RGD, or KGD-containing peptides such as integrilin, peptidomimetics, and orally available inhibitors.7-11 Abciximab is the generic name for the humanized form of Fab fragments of the murine MoAb, 7E3 (c7E3). It is used in ischemic cardiovascular disease to prevent arterial thrombosis, in particular in patients with a high thrombotic risk undergoing percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA). It is the most commonly used anti–GP IIb-IIIa therapy at the current time.11 It is also the first anti-integrin therapy to be used on a large scale.7

The first major trial using abciximab was the EPIC study, which showed that it can reduce by 35% the major complications of PTCA at the primary end point of 30 days.12 These results were obtained using a regimen in which a bolus of 0.25 μg/kg was followed by an infusion of 10 μg/min for 12 hours. In the EPIC study, platelet aggregation induced by ADP was totally inhibited during the perfusion. The lack of platelet aggregation in patients receiving abciximab can be compared with that observed in the inherited disorder, Glanzmann’s thrombasthenia.13 Nevertheless, if there are similarities in the response of platelets to ADP, the response to thrombin is different. Whereas in thrombasthenia the platelets do not aggregate to thrombin, Kleimann et al14 showed that following administration of a bolus of c7E3, platelets of patients with ischemic coronary disease continue to show a residual aggregation response to thrombin, thereby implying the continued presence of unblocked receptors. Recently, we reported similar results for platelets of patients receiving a bolus of c7E3 Fab followed by an infusion.15 An apparently internal pool of GP IIb-IIIa free of abciximab was detected using a competitive MoAb, AP-2, and the surface expression of this pool was shown after thrombin stimulation.15

Our current study investigated the mechanisms whereby abciximab gains access to the different pools of GP IIb-IIIa in platelets. To do this, we first used electron microscopy (EM) and immunogold labeling to detect c7E3 Fab on frozen ultrathin sections of platelets isolated from patients undergoing antithrombotic therapy. The patients in question received abciximab for 18 to 24 hours before prescheduled PTCA under the conditions defined in the CAPTURE protocol.15,16 Using a previously characterized rabbit antibody monospecific for c7E3 Fab fragments,17 18 we observed that abciximab not only labeled the surface membrane but also penetrated within the SCCS and was detected on the membranes of some α-granules. Significantly, a time-dependent loss was observed from all pools in the days following the perfusion. Short-term incubation of platelets with abciximab, in vitro, led to the visualization of many thin SCCS channels lined with the gold particles representing receptor-bound c7E3 Fab. These sometimes juxtaposed with the α-granules of unstimulated platelets, raising the question of a direct exchange of GP IIb-IIIa between them. An occasional presence of vesicles containing both c7E3 and clathrin also showed that endocytosis was occurring. Thus, monovalent c7E3 Fab fragments are an interesting tool for following the trafficking of GP IIb-IIIa complexes in platelets. At the same time, our results underline that under current conditions of abciximab therapy, unblocked GP IIb-IIIa complexes in platelets are able to mediate a residual secretion-dependent aggregation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and the Abciximab Infusion Protocol

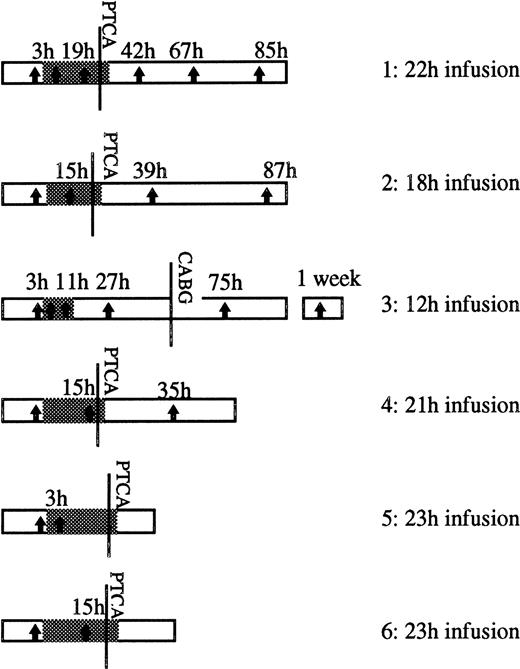

Our report covers studies on 6 patients treated with abciximab in the Cardiology Department of our hospital. All of the patients suffered from ischemic coronary disease and were diagnosed as having refractory unstable angina. The patients received 0.25 mg/kg body weight of abciximab as a bolus followed by a perfusion of 10 μg/min over a period of 12 to 24 hours. The details for each patient are shown in Fig 1. With the exception of patient 3, PTCA was performed and the abciximab infusion continued for 1 hour as in the CAPTURE study.16 Each patient received intravenous heparin and aspirin as described elsewhere.15 Bleeding complications were not seen in this group, and none of the patients developed thrombocytopenia during the period of study. For patient 3, lesions were present in three coronary vessels, and a late decision was taken for coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG). This was performed when platelet aggregation with ADP had returned to values higher than 50%. Approval from the local Ethics Committee was obtained before the onset of the study.

Schema showing the duration of the abciximab infusion (grey section) following the bolus in each of the patients studied. The moment at which PTCA was performed is indicated, as is the time at which patient 3 underwent CABG. The vertical arrows show the times (h) at which samples were taken for EM and platelet function testing. The point at which abciximab therapy started is considered as time zero.

Schema showing the duration of the abciximab infusion (grey section) following the bolus in each of the patients studied. The moment at which PTCA was performed is indicated, as is the time at which patient 3 underwent CABG. The vertical arrows show the times (h) at which samples were taken for EM and platelet function testing. The point at which abciximab therapy started is considered as time zero.

Platelet Preparations

Figure 1 shows the times at which samples were taken for EM and platelet function testing. During the infusion of abciximab and during the following 24 hours, samples were obtained from a vascular sheath. After removal of the catheter, peripheral blood was obtained by clean venipuncture.15 The initial 3 mL of blood was always discarded. Blood was collected into acid-citrate-dextrose NIH formula A (ACD-A) (1 vol of anticoagulant:6 vol of blood) or into 3.8% (wt/vol) sodium citrate (1 vol:9 vol) (see below). Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) was prepared by centrifugation at 120g for 10 minutes at room temperature. To prepare washed platelets, prostaglandin E1 (100 nmol/L; Sigma, St Louis, MO), 25 μg/mL apyrase (Sigma), and ACD-A (1 vol:9 vol, PRP) were added immediately to PRP obtained from blood anticoagulated with ACD-A. Platelets were sedimented by centrifugation at 1,200g for 15 minutes and washed as previously described.19 The platelets were resuspended at 2 × 108/mL in 137 mmol/L NaCl, 2 mmol/L KCl, 12 mmol/L NaHCO3, 0.3 mmol/L NaH2PO4, 1 mmol/L MgCl2, 5.5 mmol/L glucose, 5 mmol/L HEPES, 0.1% (wt/vol) bovine serum albumin (BSA), pH 7.4 (HEPES buffer–modified tyrode [HBMT]).

Platelet Aggregation

The platelet response during the abciximab infusion was tested using citrated PRP in a platelet aggregometer (PAP-4 model; Biodata Corporation, Wellcome, Paris) with stirring.20 ADP (8 μmol/L; Sigma) or thrombin receptor activating peptide (TRAP)-14 mer (25 μmol/L; Neosystem, Strasbourg, France) were used as agonists. The platelet count did not vary significantly before and after the infusion of abciximab for the patients tested, so the PRP contained approximately the same number of platelets for each patient. Results are given as the maximal intensity of aggregation measured as the light transmission change after three minutes when the plateau had been reached (expressed as a percentage). The inhibition of platelet aggregation by abciximab was calculated as a function of the response measured for the same patient before the abciximab bolus injection.

Short-Duration Incubations of Abciximab With Platelets In Vitro

Blood from normal subjects or from a patient with type I Glanzmann’s thrombasthenia (see George et al,21patient no. 9) with a homozygous mutation 1063G′A in exon 12 of the gene coding for GP IIb giving rise to a E355K mutation22 was taken into ACD-A anticoagulant and washed platelets prepared as described above. The platelets suspended at 250,000/μL in HBMT were incubated with abciximab (ReoPro; Centocor, Malvern, PA) at 10 μg/mL for times ranging between 1 and 60 minutes. Platelets were then fixed directly.

Electron Microscopy

Sample preparation.

Washed platelets from patients receiving abciximab or platelets from subjects incubated with abciximab in vitro were fixed in the presence of a mixture of 1% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde (PFA; Sigma) and 0.1% (wt/vol) glutaraldehyde (Fluka AG, Buchs, Switzerland) or with 1.25% (wt/vol) glutaraldehyde in 0.1 mol/L phosphate buffer, pH 7.2, for 30 minutes at room temperature. Fixed platelets were washed 3× in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.2.23 The pellet was subdivided into small blocks that were cryoprotected with 2.3 mol/L sucrose before being frozen in liquid propane using the Reichert KF 80 freezing system (Leica, Vienna, Austria).

Preparation of ultrathin sections and immunogold staining.

Procedures were basically as previously described by us.23,24 In brief, ultrathin sections of platelets were cut with a Reichert-Jung Ultracut E ultramicrotome equipped with a FC 4E cryokit attachment (Reichert-Jung, Vienna, Austria) and placed on collodion-coated nickel grids. In subsequent steps, the grids were transferred onto drops containing antibodies or washing buffer as described below. Rabbit antibody prepared against c7E3 was used at a dilution of 1/100 of affinity-purified IgG (a gift from Centocor).17,18 Anti-clathrin heavy-chain MoAb (mouse IgG1 purchased from MedGene Science, Pantin, France) was used at 5 μg/mL. All dilutions were in PBS, pH 7.2, containing 0.1% (wt/vol) BSA (Sigma). The grids were kept floating on the antibody-containing solution for 1 hour at room temperature. After 3 washes, bound antibody was revealed by incubating for 1 hour with gold-labeled anti-rabbit or anti-mouse IgG (1/100 dilution of Auroprobe EM GAR or GAM G5 or G10 [Amersham, Les Ulis, France]). After 3 more washes, the cryosections were stained by uranyl acetate and embedded in a thin film of methylcellulose before being observed at 80 kV in a Jeol JEM-1010 transmission electron microscope (Jeol, Croissy-sur-Seine, France).24 In the double-labeling experiments, sections were serially incubated with rabbit anti-c7E3, GAR G5, murine anti-clathrin MoAb and GAM G10 with three washings between the addition of each new antibody. Controls involved the substitution of primary antibodies with nonimmune rabbit or mouse IgG during the labeling of the sections. Preliminary experiments established that GAM G10 failed to detect bound abciximab and did not cross-react with rabbit IgG. In studies on platelets from the patients, control sections were also prepared from platelets taken from each patient before their receiving abciximab. Sections of platelets from the patient with Glanzmann’s thrombasthenia were tested with the anti-c7E3 antibody only.

Computer analysis.

The distribution of gold particles revealing bound abciximab was evaluated for patients 1, 2, and 3 on platelet sections photographed using a Sony XC 077C camera (Sony, France, Paris) digitalized in 640 × 480 pixels coded in 256 levels of gray. Image analysis was performed using a program constructed by C. Allasia (Faculté de Médecine, Université de la Mediterranée, Marseille, France) and installed on an IBM PC Pentium 166 computer equipped with Image Series 640 cards (Matrox France, Paris) driven by the IPS program (Unilog, Grenoble, France). Gold particles located on the surface membrane or within the internal compartment of platelets (SCCS + α-granules) were counted separately. A minimum of 10 sections were evaluated for each time point. The density of gold particles on the surface membrane was calculated by relating the number of gold particles to the perimeter length. The latest time for which the quantitation was performed was 7 days after the infusion of abciximab for patient 3.

Flow Cytometry

Platelets of patients receiving c7E3.

Samples of washed platelets (108/mL) were fixed with 2% (vol/vol) PFA for 30 minutes at room temperature. The samples were washed 3× in PBS, pH 7.2, containing 0.1% (wt/vol) BSA and then incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature with 100 μL of fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated F(ab′)2fragments of a goat antibody monospecific for human IgG F(ab′)2 (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) diluted 1/100 in HBMT. Preliminary studies had confirmed that the murine sequences were largely inaccessible to the anti-mouse IgG antibodies in flow cytometry when c7E3 Fab was bound to platelets.15,19 Control measurements were made using FITC-labeled F(ab′)2 fragments of a goat antibody monospecific for the human IgG Fc fragment (Jackson ImmunoResearch). The platelet suspension was then diluted with 750 μL HBMT before analysis using a Becton Dickinson FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Le Pont de Claix, France). The fluorescence intensity was determined for the platelet population identified by gating on light scattering parameters (forward scatter versus side scatter).20 23 Ten thousand cells were analyzed for each sample and the data were registered as log fluorescence. Mean fluorescence intensities (MFI) as a measure of antibody binding were expressed using the LYSYS II conversion software in an arithmetic mode.

Short-duration incubations of abciximab with platelets in vitro.

Unblocked GP IIb-IIIa complexes were located using AP-2 (a gift from Dr Thomas Kunicki, Scripp’s Research Institute, La Jolla, CA), a murine monoclonal antibody that we have shown to be competitive with c7E3 Fab for GP IIb-IIIa.15 19 Isolated platelets were incubated or not with 10 μg/mL c7E3 Fab for 30 minutes as described above. After being washed twice, samples were then incubated in the presence or absence of 0.5 U/mL thrombin for 10 minutes. Samples were immediately fixed with PFA as described above. Aliquots of fixed platelets (10 μL at a concentration of 100,000/μL) were added to polystyrene tubes containing 100 μL HBMT and 7 μg/mL AP-2. Controls were performed in the absence of primary antibody or in the presence of purified myeloma mouse IgG (Sigma). All samples were incubated for 15 minutes at room temperature without stirring. Then 10 μL of a predetermined optimal concentration of FITC-conjugated affinity-purified F(ab′)2 fragments of sheep antibody to mouse IgG (Silenus, Eurobio, Les Ulis, France) were added. The tubes were left in the dark at room temperature for an additional 15 minutes before analysis with the FACScan as described above.

Statistical analysis.

Data were analyzed using the Student’s t-test for unpaired data. A value of P < .05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Studies on Platelets Obtained From Patients Receiving Abciximab

Platelet function testing.

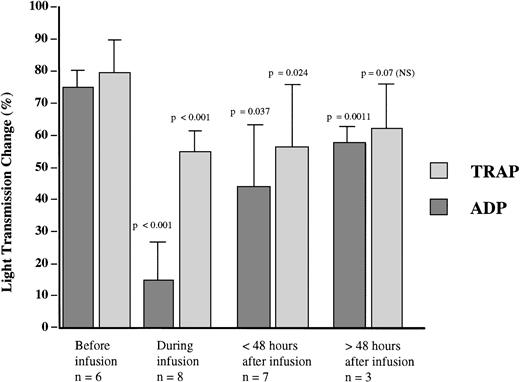

The effects of abciximab on platelet aggregation induced by ADP and by TRAP-14 mer were studied for each patient at the sampling times shown in Fig 1. A greater than 80% inhibition of ADP-induced platelet aggregation was obtained for each patient during the infusion and was seen as early as 3 hours after the onset of therapy for the three patients tested at this time point. This consistency allowed us to group the results for the patients together (Fig 2). The recovery of the aggregation response had begun within 24 hours after the infusion was stopped, and was extensive after 48 hours, although the difference remained statistically significant compared with the pretreatment value. With TRAP-14 mer, which mimics thrombin and induces a secretion-dependent aggregation in platelet-rich plasma, the inhibition was more modest during the infusion, and residual aggregation of at least 50% of initial levels was observed for each patient. The aggregation response to TRAP-14 mer was no longer statistically lower 48 hours after the infusion had ended. The results with TRAP-14 mer were compatible with the presence of a pool of GP IIb-IIIa complexes inaccessible to abciximab even after a combined therapy of bolus and infusion.

Platelet aggregation induced by ADP (8 μmol/L) or 25 μmol/L TRAP-14 mer peptide in citrated PRP prepared from patients receiving abciximab and tested at the sample times shown in Fig 1. Results are expressed as percent light transmission at 3 minutes of aggregation (maximal values) and are grouped together for samples taken during the infusion, and at periods less than 48 hours and greater than 48 hours after the drug administration ended. The P values for the observed inhibition were calculated with respect to the aggregation intensity before the onset of abciximab.

Platelet aggregation induced by ADP (8 μmol/L) or 25 μmol/L TRAP-14 mer peptide in citrated PRP prepared from patients receiving abciximab and tested at the sample times shown in Fig 1. Results are expressed as percent light transmission at 3 minutes of aggregation (maximal values) and are grouped together for samples taken during the infusion, and at periods less than 48 hours and greater than 48 hours after the drug administration ended. The P values for the observed inhibition were calculated with respect to the aggregation intensity before the onset of abciximab.

Localization of abciximab on platelet sections by immunoelectron microscopy.

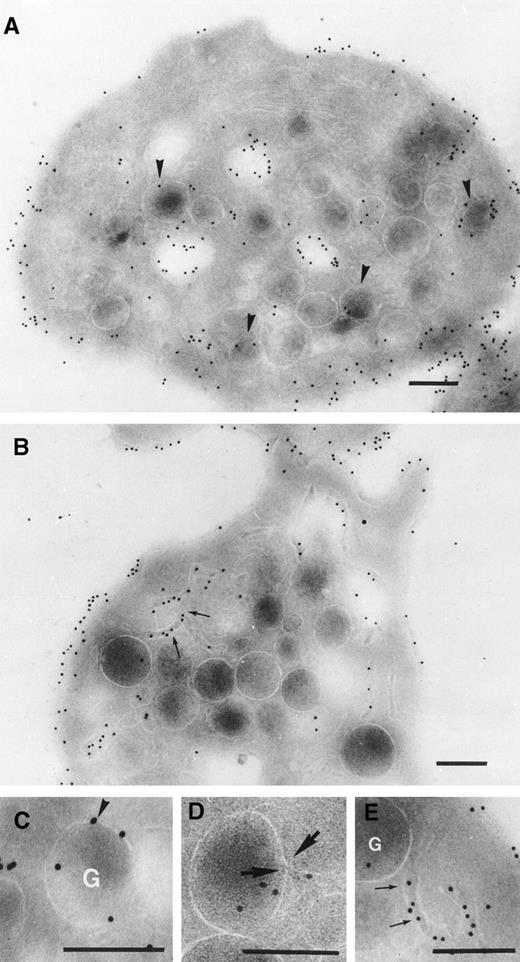

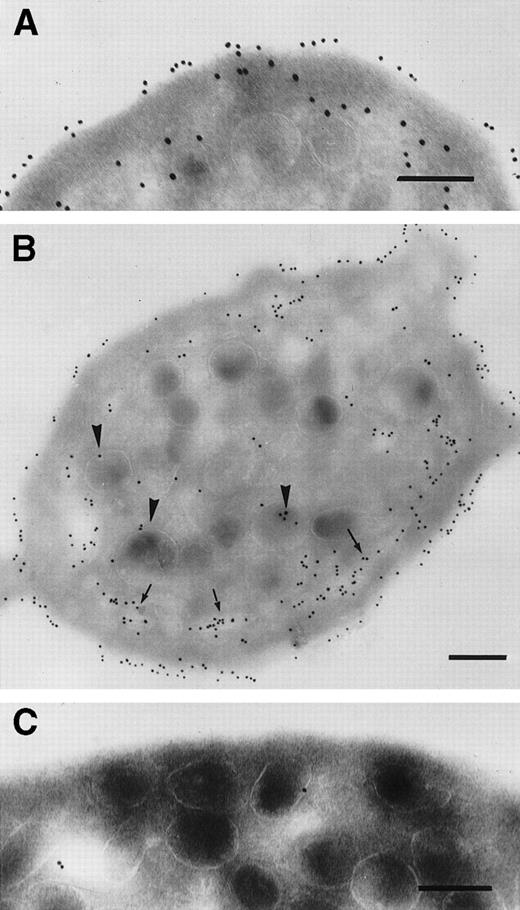

Initial controls performed using platelets isolated from each patient before therapy showed that the rabbit anti-c7E3 antibody did not label the cryosections in the absence of abciximab (data not shown). For platelets taken from the patients during the abcximab infusion, we observed a regular labeling of the platelet surface, which was often dense (Fig 3). In Fig 3A, the sample was taken 3 hours after the onset of the infusion to patient 1. The illustration is typical of the results obtained for each of the three patients tested at this early time point. Significantly, labeling can already be seen inside the platelet, where it was localized both to the SCCS and to the luminal surface of the membranes of some but not all α-granules. Figure 3B through E illustrates platelets taken 19 hours after the start of abciximab infusion to patient 1. The results resembled those seen at 3 hours with a maximum labeling of the surface membrane and also staining inside the platelets. Figure 3C shows a high-power section of an α-granule with several membrane-associated gold particles. We have previously shown similar labeling for P-selectin, a known α-granule protein.6 Figure 3D shows a thin channel arriving inside an α-granule; a thin opening can be seen in the membrane of the α-granule. Figure 3E is a high-power section from Fig 3B and highlights the thin SCCS channels interwinding within the platelet and decorated by gold particles. The labeling of SCCS and α-granules during the infusion was a consistent finding for the platelets of all patients. Nevertheless, the extent of the labeling of α-granules varied considerably from one platelet to another.

Detection of abciximab by immunogold labeling using an affinity-purified rabbit antibody specific for c7E3. Examined were frozen ultrathin sections of platelets taken from patient 1 (A) 3 hours or 19 hours (B through E) into the infusion. High-power magnifications of a labeled -granule and of thin tortuous channels of the SCCS are shown in (C) and (E), respectively. In (D) a very thin aperture in the membrane of -granule at a point of junction of a thin channel is shown and indicated between two arrows. Bars = 0.2 μm.

Detection of abciximab by immunogold labeling using an affinity-purified rabbit antibody specific for c7E3. Examined were frozen ultrathin sections of platelets taken from patient 1 (A) 3 hours or 19 hours (B through E) into the infusion. High-power magnifications of a labeled -granule and of thin tortuous channels of the SCCS are shown in (C) and (E), respectively. In (D) a very thin aperture in the membrane of -granule at a point of junction of a thin channel is shown and indicated between two arrows. Bars = 0.2 μm.

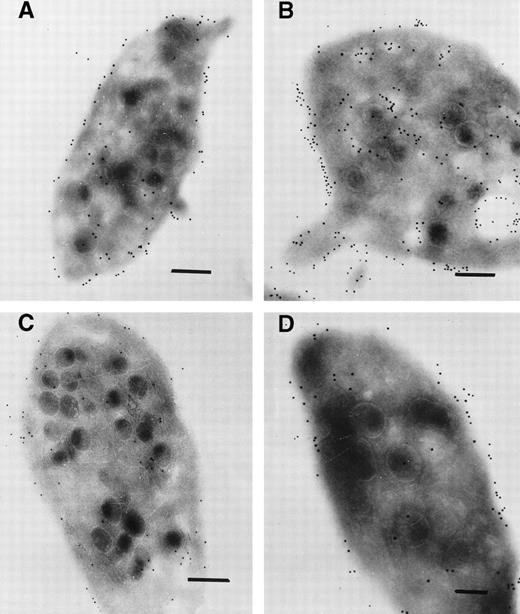

The distribution of gold particles during the 48 hours after the infusion was stopped and closely resembled that seen on platelets taken during the therapy. Abciximab was detected on the platelet surface and inside the platelets; labeling again concerned both the SCCS and the membranes of some but not all α-granules. In Fig 4A, it is the surface membrane that is primarily labeled; in Fig 4B there is considerable labeling of the internal pool. Such types of image were seen for all patients and underline the heterogeneity observed in the platelet response to this drug. For the illustrated final samplings, taken for patient 1 after 85 hours (Fig 4C) and patient 3 after 1 week (Fig 4D), labeling both at the platelet surface and in the interior was generally much more sparse. Although a considerable number of new platelets would have been released into the circulation since the stopping of therapy, most of the platelets continued to show some labeling (not illustrated).

Immunogold labeling for abciximab on ultrathin sections of platelets taken (A) 20 hours after the end of the abciximab infusion (patient 1), (B) 15 hours after the end of the infusion (patient 3), (C) 67 hours after the end of the infusion (patient 1), (D) 1 week after the end of the infusion (patient 3). There is a notable decrease in the labeling at the longer time points. Bars = 0.2 μm.

Immunogold labeling for abciximab on ultrathin sections of platelets taken (A) 20 hours after the end of the abciximab infusion (patient 1), (B) 15 hours after the end of the infusion (patient 3), (C) 67 hours after the end of the infusion (patient 1), (D) 1 week after the end of the infusion (patient 3). There is a notable decrease in the labeling at the longer time points. Bars = 0.2 μm.

Computer analysis.

The number of gold particles was quantified on sections of a minimum of 10 platelets for each sample taken during and after abciximab infusion for patients 1, 2, and 3 (Table 1). A computer program also compared the distribution of gold particles between the surface and internal membrane systems. During the infusion, the mean gold particle density on the surface of platelets of each patient was consistently high. Particles associated with internal membrane systems represented 24%, 28%, and 31% of the total number counted for each patient. These values changed little in the 48 hours that followed the end of the infusion, although there was slightly more intersubject variation. After 48 hours, labeling both at the surface and within the platelet had decreased, and although the percentage of gold particles inside the platelet was marginally greater, these measurements confirmed that there was not a progressive and unidirectional accumulation of abciximab within the platelets.

Computer Analysis of Gold Particle Density on Platelet Sections

| Localization of c7E3 . | During Infusion . | <48 h After Infusion . | >48 h After Infusion . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Particles per Section . | Linear Density . | No. of Particles per Section . | Linear Density . | No. of Particles per Section . | Linear Density . | |

| At the platelet surface | 75.10 ± 10.48 | 8.85 ± 0.32 | 61.49 ± 16.85 | 8.84 ± 2.85 | 33.87 ± 5.52 | 4.88 ± 1.81 |

| NS | (P < .001) | |||||

| Inside the platelet | 24.64 ± 7.58 | 24.38 ± 9.47 | 17.16 ± 10.95 | |||

| NS | NS | |||||

| Total | 99.74 ± 15.7 | 85.87 ± 23.53 | 51.03 ± 14.99 | |||

| NS | (P < .051) | |||||

| Percentage inside the platelets | 24.26 ± 4.94 | 28.21 ± 6.24 | 31.33 ± 11.06 | |||

| NS | NS | |||||

| Localization of c7E3 . | During Infusion . | <48 h After Infusion . | >48 h After Infusion . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Particles per Section . | Linear Density . | No. of Particles per Section . | Linear Density . | No. of Particles per Section . | Linear Density . | |

| At the platelet surface | 75.10 ± 10.48 | 8.85 ± 0.32 | 61.49 ± 16.85 | 8.84 ± 2.85 | 33.87 ± 5.52 | 4.88 ± 1.81 |

| NS | (P < .001) | |||||

| Inside the platelet | 24.64 ± 7.58 | 24.38 ± 9.47 | 17.16 ± 10.95 | |||

| NS | NS | |||||

| Total | 99.74 ± 15.7 | 85.87 ± 23.53 | 51.03 ± 14.99 | |||

| NS | (P < .051) | |||||

| Percentage inside the platelets | 24.26 ± 4.94 | 28.21 ± 6.24 | 31.33 ± 11.06 | |||

| NS | NS | |||||

Mean values are for a minimum of 10 sections for patients 1, 2, and 3 at each time point (see Fig 1) counted as described in Materials and Methods. Results are grouped as shown. The decrease in the number of gold particles at the platelet surface was not significant during the first 48 hours after the end of the c7E3 infusion, but after 48 hours it was significant. Findings were similar for the total number of gold particles, and the tendency was the same for gold particles present inside the platelets although the difference after 48 hours was not significant due to the greater heterogeneity between platelets.

Abbreviation: NS, not significant.

Flow cytometry.

As a supplement to the EM studies, we used flow cytometry to evaluate the levels of c7E3 Fab bound to the platelet surface. A rapid and large increase in the MFI was observed during the infusion of abciximab. The grouped MFI values during the infusion (266.4 ± 74.3; n = 7) were the maximum obtained; levels remained high at 48 hours (218.3 ± 90.8, P = .031; n = 6) but fell progressively at time points greater than 48 hours (162 ± 20.8, P = .024; n = 4). Interestingly, a single peak of fluorescence was always observed on the histograms, showing that new platelets produced after the end of the abciximab infusion possessed c7E3 Fab, seemingly confirming an exchange between platelets via the plasma pool as suggested by Christopoulos et al.17 18 The positivity was not related to the binding of plasma immunoglobulins, either to prebound c7E3 or to exposed platelet neoantigens, as the binding of FITC-labeled anti-human Fc fragments antibody remained negative.

Short-Duration Incubations of Platelets With Abciximab In Vitro

Immunogold staining for abciximab.

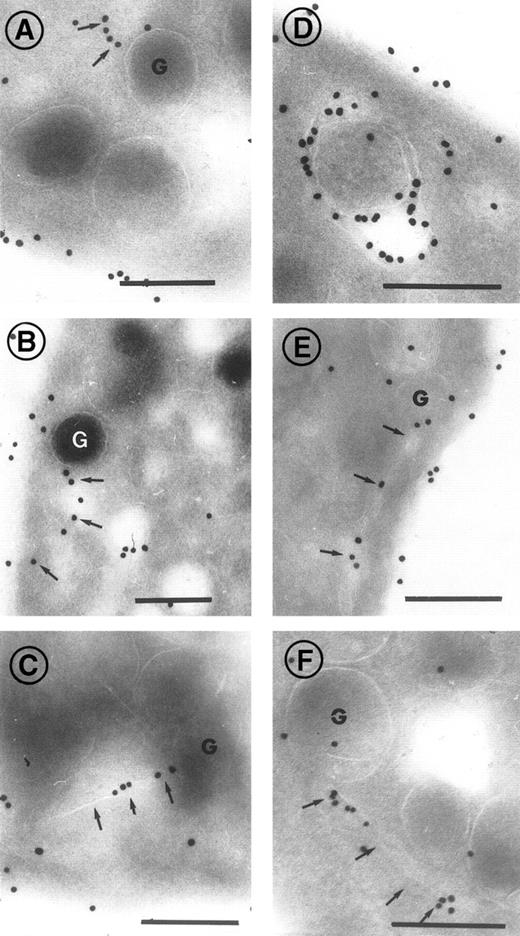

Platelets from normal subjects were incubated with 10 μg/mL c7E3 Fab for periods of 1 minute, 5 minutes, or 1 hour. The results showed that some abciximab was already seen inside the cell after a 1-minute incubation but that labeling was greater after 1 hour. Figure 5A illustrates a platelet incubated for 1 minute with c7E3 Fab. In Fig 5B, normal platelets have been incubated for 1 hour with c7E3; a long, thin channel of SCCS located parallel to the plasma membrane is strongly labeled; and gold beads were associated with some α-granules. As was found for platelets from patients receiving abciximab, not all the membranes located inside the platelets were labeled. Figure 5C illustrates the labeling of platelets from a patient with Glanzmann’s thrombasthenia incubated for 1 hour with 10 μg/mL of c7E3. In the absence of GP IIb-IIIa complexes, little or no staining was present on the platelet surface at all time points tested and only rare gold particles were present inside the platelets. This result confirms that we were not locating free c7E3 that had simply diffused within the channels.

Incubation of platelets from a control donor (A and B) and a patient with Glanzmann’s thrombasthenia (C) with abciximab in vitro. Platelets were fixed after 1-minute (A) or 1-hour staining (B and C). Arrows highlight the presence of gold particles within the thin channels of the SCCS, arrow heads indicate gold particles associated with -granules. In (C) almost no labeling was seen. Bars = 0.2 μm.

Incubation of platelets from a control donor (A and B) and a patient with Glanzmann’s thrombasthenia (C) with abciximab in vitro. Platelets were fixed after 1-minute (A) or 1-hour staining (B and C). Arrows highlight the presence of gold particles within the thin channels of the SCCS, arrow heads indicate gold particles associated with -granules. In (C) almost no labeling was seen. Bars = 0.2 μm.

In Fig 6, a series of high-power insets illustrate the presence of gold beads associated with α-granules and the thin tortuous channels of the SCCS. Examples have been chosen where the channels arrive in close proximity to the α-granules. Most of the labeling of the α-granules was associated with the membrane. However, intense labeling of the entire α-granule membrane was rare. The channels sometimes are directed toward the α-granule and, on occasion, appear to be in contact with them (see Fig 6B and C).

High-power magnifications showing the incorporation of abciximab into control platelets in vitro. Incubation periods with abciximab before fixation were 1 minute (A, B, and C), 5 minutes (D), 30 minutes (E), and 1 hour (F). Thin channels in close association and apparently directed toward -granules are labeled with arrows. Bars = 0.2 μm.

High-power magnifications showing the incorporation of abciximab into control platelets in vitro. Incubation periods with abciximab before fixation were 1 minute (A, B, and C), 5 minutes (D), 30 minutes (E), and 1 hour (F). Thin channels in close association and apparently directed toward -granules are labeled with arrows. Bars = 0.2 μm.

Colocalization with clathrin.

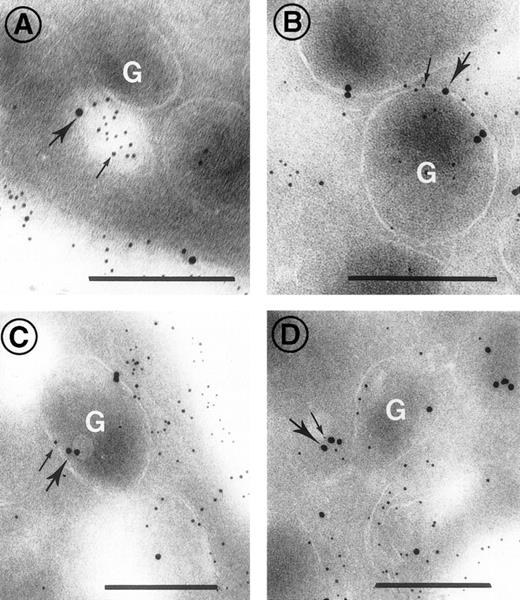

Because translocation of bound ligands from the surface to the internal compartment is classically believed to involve the formation of endocytic vesicles containing clathrin, we performed double staining of sections with the rabbit anti-c7E3 antibody and a murine MoAb to clathrin. As shown in Fig 7, colocalization was observed (A) in vesicular structures within the platelets and (B and C) within α-granules. Colocalization was not observed in the SCCS. In Fig 7D a vesicle appears to be fusing with an α-granule. These results show for the first time that internalization of abciximab can occur through the formation of endocytic vesicles, although it remains to be shown what proportion of abciximab is incorporated in this way.

Double-staining for c7E3 and clathrin on platelet sections after the incubation of platelets with abciximab for 5 minutes in vitro. Clathrin was detected with a mouse MoAb, in turn localized with goat anti-mouse IgG adsorbed to 10 nm gold particles (heavy arrows). Abciximab was detected using rabbit antibody itself detected using anti-rabbit IgG adsorbed onto 5 nm gold particles (thin arrows). In (A) a vesicle in close proximity to a granule contains both abciximab and clathrin, in (B and C) clathrin and abciximab are both associated with the membrane of -granules, and in (D) a small vesicle containing clathrin and abciximab appears to be fusing with an -granule. Bars = 0.2 μm.

Double-staining for c7E3 and clathrin on platelet sections after the incubation of platelets with abciximab for 5 minutes in vitro. Clathrin was detected with a mouse MoAb, in turn localized with goat anti-mouse IgG adsorbed to 10 nm gold particles (heavy arrows). Abciximab was detected using rabbit antibody itself detected using anti-rabbit IgG adsorbed onto 5 nm gold particles (thin arrows). In (A) a vesicle in close proximity to a granule contains both abciximab and clathrin, in (B and C) clathrin and abciximab are both associated with the membrane of -granules, and in (D) a small vesicle containing clathrin and abciximab appears to be fusing with an -granule. Bars = 0.2 μm.

Flow cytometry.

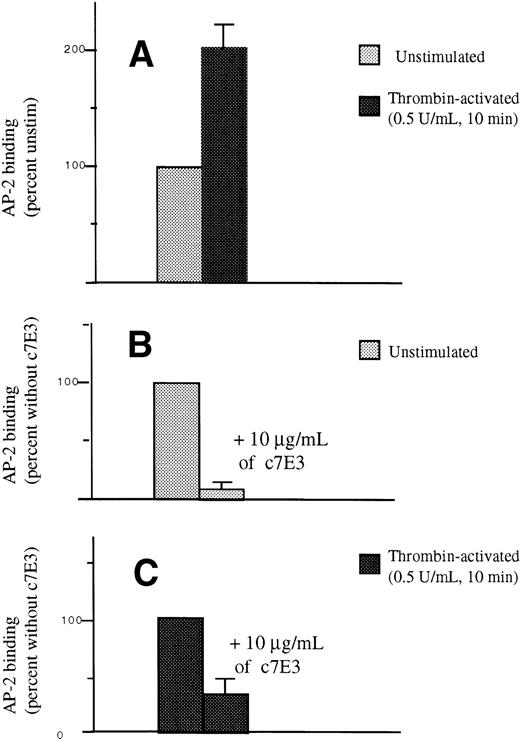

To analyze the free pool of GP IIb-IIIa, we have used AP-2, a murine MoAb that is competitive for c7E3 as described previously.15 19 Incubation of normal platelets for 30 minutes with 10 μg/mL of c7E3 Fab in vitro resulted in a severe reduction in the binding of AP-2 to the surface of unstimulated platelets. We found that the MFI after incubation was 9.20 ± 4.3% of the initial values. After stimulation of untreated platelets with thrombin 0.5 U/mL for 10 minutes, the MFI for AP-2 binding was 202 ± 20.48% (n = 5) of that seen for unstimulated platelets. After incubation with c7E3, the MFI after thrombin treatment was 33.80 ± 10.91% (n = 5) of the value obtained in the absence of drug. The results, illustrated in Fig 8, therefore confirm that an appreciable pool of unblocked GP IIb-IIIa appeared on the platelet surface after thrombin stimulation and c7E3 incubation. The conclusion from these experiments is that only part of the internal pool, which can represent about half of the total pool of GP IIb-IIIa, was in contact with abciximab at any one time. Quantitatively, the values obtained in flow cytometry in the in vitro experiments were very close to the results found for patients receiving c7E3 and where antibody distribution was assessed by computer analysis of labeled electron micrographs.

Detection by flow cytometry of AP-2 binding to platelets after their incubation with abciximab for 30 minutes in vitro. In (A), AP-2 binding to untreated and unstimulated platelets was considered as 100%. This value increased twofold after incubation of the platelets with 0.5 U/mL thrombin for 10 minutes. In (B), AP-2 binding to unstimulated platelets was again considered as 100%. AP-2 binding was severely decreased after a 30-minute preincubation with 10 μg/mL of abciximab. In (C), AP-2 binding to untreated thrombin-stimulated platelets was now taken as 100%; when platelets were incubated with c7E3 Fab before stimulation with thrombin, AP-2 binding was 33.8 ± 10.9% of that obtained in the absence of drug. Tests were performed on platelets from five donors.

Detection by flow cytometry of AP-2 binding to platelets after their incubation with abciximab for 30 minutes in vitro. In (A), AP-2 binding to untreated and unstimulated platelets was considered as 100%. This value increased twofold after incubation of the platelets with 0.5 U/mL thrombin for 10 minutes. In (B), AP-2 binding to unstimulated platelets was again considered as 100%. AP-2 binding was severely decreased after a 30-minute preincubation with 10 μg/mL of abciximab. In (C), AP-2 binding to untreated thrombin-stimulated platelets was now taken as 100%; when platelets were incubated with c7E3 Fab before stimulation with thrombin, AP-2 binding was 33.8 ± 10.9% of that obtained in the absence of drug. Tests were performed on platelets from five donors.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have localized c7E3 Fab fragments within the different membrane compartments of platelets using two model systems: (1) platelets from patients receiving abciximab for ∼24 hours during antithrombotic therapy and (2) control platelets given a short-duration challenge with abciximab in vitro. In view of their small size, monovalent nature, and therapeutic use, c7E3 Fab are interesting probes for following GP IIb-IIIa movements in platelets. The initial detection of c7E3 Fab within the SCCS and on the membrane of some α-granules within 3 hours of the start of the infusion implied rapid trafficking toward the internal membrane systems, and this was confirmed when control platelets were incubated for shorter times with abciximab in vitro.

The labeling of the SCCS channels and α-granule membranes in the in vitro studies where uptake was seen as early as 1 minute after the addition of abciximab suggested a rapid diffusion of c7E3 into the internal platelet compartments. Zucker-Franklin in a pioneering study nicely showed that the channels of the SCCS were sites of entry for exogenous substances.25 When platelets from a patient with type I Glanzmann’s thrombasthenia were incubated with c7E3, only occasional gold particles were associated with platelets when ultracryosections were incubated with the anti-c7E3. The absence of labeling within the SCCS proves that we were detecting bound rather than free abciximab in the studies on platelets of normal subjects. The rare gold particles seen on the membrane of α-granules of the patient’s platelets may correspond to the labeling of the vitronectin receptor. This receptor has been found to be present at low density in the α-granule membrane.24 The patient studied has a homozygous mutation in the αIIbgene,22 thus allowing the vitronectin receptor to be present.

In our studies on platelets of patients receiving an abciximab infusion or with platelets incubated with abciximab in vitro, we repeatedly observed the presence of thin channels labeled for abciximab in close proximity to the α-granules. Although the opening of the SCCS into the external medium has been previously shown,25,26 a direct interaction between these channels and the membrane of α-granules in unstimulated platelets is unknown. The apparent presence on rare sections of a gap in the membrane of an α-granule with a channel present in this position lends weight to the hypothesis that the thin channels may provide a facilitated route for transport from the exterior to the granules. The existence of a direct interaction between granules and the SCCS was hypothesized by Zucker-Franklin,25 who underlined that modest secretion from platelets can sometimes occur without detectable morphological evidence of granule fusion or exocytosis. Recently, “worm-like structures” containing MoAbs prebound to platelets were visualized after platelet activation with ADP.27 Such structures may correspond to the thin SCCS seen here and represent routes between the surface and the platelet interior.

Performing immunogold labeling on ultrathin cryosections without dehydration, as in the current study, allows an improved preservation of platelet ultrastructure, whereas the highlighting of the thin channels by the gold particles lining them may also help to explain why we see such structures where others using standard EM have failed. Fusion of α-granule membranes with the intraplatelet channels after platelet secretion has been deduced from the observed presence of granule-proteins within the SCCS.28,29 In the cited studies, the SCCS channels were dilated helping their visualization. Just as the juxtaposition of the SCCS with granules can facilitate secretion, it can also help to explain how plasma proteins are able to rapidly find their way to the granules. The abundance of the SCCS network spreading through the cytoplasm26 can also be a factor in this regard. Whereas specific proteins such as gap junction proteins30 or docking proteins31 are known to be involved in secretory-dependent fusion processes and endocytosis in other cells, their involvement in the uptake of ligands through the SCCS and the formation of points of contact with the granules will be a matter for further study. Visualization of c7E3 inside the SCCS must be distinguished from the previously described activation-dependent translocation of GP IIb-IIIa–bound fibrinogen conjugated to gold particles or to biotin.32 33 In this situation, fibrinogen is progressively cleared from the platelet surface to dilated elements of the SCCS. These processes differ from the uptake described here for unactivated platelets. The speed at which labeling of the thin channels occurred would suggest that diffusion or flow of c7E3 fab fragments into them was followed by binding. The fact that the surface remains covered with gold particles is not in favor of an unidirectional translocation of complex-bound c7E3 Fab from the platelet surface.

During in vitro incubations, we observed vesicles containing both abciximab and clathrin in the intracytoplasmic compartment and sometimes in close association with α-granules. Thus c7E3 may also reach the membrane of α-granules by the endocytic pathway. The formation of coated pits containing ligand-bound receptors followed by the formation of endocytic vesicles is a classic pathway for the internalization of ligands. Behnke first visualized coated vesicles fusing with α-granules when platelets were incubated with either colloidal thorium dioxide or a colloidal gold suspension.34Clathrin-coated endocytic vesicles containing adhesive proteins including fibrinogen have since been identified in platelets.35,36 Their association with Src-related tyrosine kinases further suggests that they constitute part of an active uptake process.37 Endocytosis has been previously invoked to explain the accumulation of immunoglobulin G inside platelets, the IgG being stored together with fibrinogen and other proteins in the α-granules, although it is unknown whether IgG uptake is receptor linked.38 Intact murine or human antibodies that bind to GP IIb-IIIa are known to be internalized by platelets.27,39,40In one study, where an anti–GP IIb-IIIa MoAb was coupled directly to gold particles, the latter reached the membranes of α-granules although no explanation was provided concerning the mechanism responsible for the internalization.40

Notwithstanding, little evidence was found in our study for unidirectional transport leading to an eventual surface clearance of the Fab fragments accompanied by the accumulation of c7E3 in the α-granules either during or after the infusion. A quantitative analysis showed that only about 25% of the gold particles were associated with internal pools during the infusion of abciximab to the patients and that the labeling of all pools decreased in parallel after the infusion was stopped. One interpretation of this finding is that the monovalent Fab fragments predominantly accompany the natural movements of GP IIb-IIIa complexes to and from the surface. Two small snake venom peptides, kristin and applagin, have both been shown to reach the internal compartment of platelets after binding to GP IIb-IIIa,41,42 and the pool of applagin inside the platelets was estimated to be 17% of the total platelet-associated peptide.42 Kristin, like c7E3 Fab, inhibits the uptake and storage of fibrinogen by platelets when administered in vivo.41,43 The fact that the surface content of GP IIb-IIIa was maintained despite the transport of applagin to the α-granules led Wencel Drake et al42 to propose that GP IIb-IIIa complexes recycle to the platelet surface. Continual exchange of glycoproteins between external and internal membrane systems in cells is a well-known phenomenon44 and would explain our findings. In a recent study, Mascelli et al45 also showed that the surface distribution of c7E3 was homogeneous for the whole platelet population not only during the infusion but also during the next 15 days. This is also in favor of a lack of unidirectional uptake of abciximab into platelets.

Another aspect of our work deserves mention. Abciximab binding was associated with a greater than 80% inhibition of ADP-induced platelet aggregation during the infusion, results that were comparable to those reported in other studies.8,15,46 Nevertheless, despite the clinical success of abciximab,43,47 our study confirms that it is difficult to completely inhibit all of the GP IIb-IIIa complexes in platelets, and residual aggregation was observed after stimulation of platelets in PRP with TRAP-14 mer peptide. This confirms another study by us15 for TRAP-14 mer and thrombin and the previous results of Kleimann et al.14 A twofold increase in the binding of radiolabeled MoAbs to GP IIb-IIIa after thrombin-induced activation of platelets48,49 is strong evidence that about half of the total population of GP IIb-IIIa complexes are innaccessible to intact IgG in unstimulated platelets. Our current flow cytometry studies with AP-2 strongly agree with this finding. Using radiolabeled 7E3 Fab fragments in direct binding studies, Wagner et al found 92,900 ± 13,100 binding sites on unstimulated platelet.50 This is much larger than the 35,000 to 50,000 sites as reported in studies with intact MoAbs,50 a result that can be explained by the fact that each intact antibody in fact binds to two adjacent molecules of GP IIb-IIIa, although a facilitated diffusion of the smaller Fab fragments into the SCCS may also in part account for this high number. Using AP-2, we have shown elsewhere by immunogold labeling and standard transmission EM that platelets from patients receiving abciximab express unblocked GP IIb-IIIa at their surface when stimulated by thrombin.15 Here, we have shown that following the incubation of platelets in vitro with 10 μg/mL of c7E3, thrombin stimulation significantly increased the amounts of AP-2 which bound, showing that about 33% of the total pool of GP IIb-IIIa was innaccessible to c7E3. Globally, our results obtained in both in vitro and in vivo studies show that despite the rapid trafficking of abciximab into the platelets, not all GP IIb-IIIa complexes participate in this process and that, at any one time, an appreciable subpopulation of GP IIb-IIIa is not occupied by c7E3 Fab. As shown by Tcheng et al8 during studies on the pharmacodynamics of the inhibition of platelet aggregation by abciximab, the frontier between a normal and an impaired aggregation response is close and a critical number of GP IIb-IIIa complexes is needed for platelet aggregation to occur. Thus, during treatment with abciximab, it is only when more than 80% of the surface pool of GP IIb-IIIa complexes are blocked that ADP-induced aggregation is inhibited. Our studies imply that with thrombin, this threshold may be difficult to reach in vivo in the time scale of the aggregation response. In this situation, the internal pools of GP IIb-IIIa conserve their own characteristics and are capable of supporting at least a partial aggregation.This residual response to thrombin might explain the absence of hemorrhagic syndromes for patients receiving abciximab when using a patient-adapted dose of heparin.51 With the development of a range of new compounds to GP IIb-IIIa, including orally bioavailable prodrugs,52their access or not to the different intracellular pools of receptors may well have an important bearing on their efficacity.

Supported by the CNRS, Université de Bordeaux II (DRED), the Ministère de l’Enseignement Supérieur et de la Recherche (ACC-SV No. 9), and Lilly-France. C.P. received doctoral grants from the GEHT (Synthelabo) and the Société Française d’Hématologie.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Address reprint requests to Paquita Nurden, MD, UMR 5533 CNRS, Hôpital Cardiologique, 33604 Pessac, France; e-mail:Paquita.Nurden@cnrshl.u-bordeaux2.fr.