Abstract

Stem cell factor (SCF) has an important role in the proliferation, differentiation, survival, and migration of hematopoietic cells. SCF exerts its effects by binding to cKit, a receptor with intrinsic tyrosine kinase activity. Activation of phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase (PI3-K) by cKit was previously shown to contribute to many SCF-induced cellular responses. Therefore, PI3-K-dependent signaling pathways activated by SCF were investigated. The PI3-K-dependent activation and phosphorylation of the tyrosine kinase Tec and the adapter molecule p62Dok-1 are reported. The study shows that Tec and Dok-1 form a stable complex with Lyn and 2 unidentified phosphoproteins of 56 and 140 kd. Both the Tec homology and the SH2 domain of Tec were identified as being required for the interaction with Dok-1, whereas 2 domains in Dok-1 appeared to mediate the association with Tec. In addition, Tec and Lyn were shown to phosphorylate Dok-1, whereas phosphorylated Dok-1 was demonstrated to bind to the SH2 domains of several signaling molecules activated by SCF, including Abl, CrkL, SHIP, and PLCγ-1, but not those of Vav and Shc. These findings suggest that p62Dok-1 may function as an important scaffold molecule in cKit-mediated signaling.

Introduction

Stem cell factor (SCF; also called steel factor, mast cell growth factor, or Kit ligand) is an important growth factor for multiple cell types, including hematopoietic progenitor cells. SCF exerts its effects by binding to the product of the cKitproto-oncogene.1 cKit is a receptor with intrinsic tyrosine kinase activity, structurally related to Flt3 and the receptors for colony-stimulating factor-1 and platelet-derived growth factor.2 Loss-of-function mutations in the loci for murine cKit, White Spotting (W), or SCF,Steel,3-6 lead to macrocytic anemia and to mast cell deficiency, as well as to a series of nonhematological defects.1,7,8 Conversely, mutations that render cKit constitutively active have been found in mastocytoma and myeloproliferative disease.9 10

Within the hematopoietic compartment, SCF can support the survival and renewal of the earliest multilineage progenitors and regulates proliferation and differentiation of mast cell precursors. In combination with lineage-restricted cytokines, SCF delays differentiation and enhances the expansion of already committed progenitors of all lineages.1 This phenomenon is particularly apparent in erythropoiesis in which the cooperation of cKit with the erythropoietin receptor (EpoR) is crucial for the proliferation of erythroblasts.11,12 It has been shown that cKit and EpoR are closely associated in erythroid cells,13 but the molecular basis for the synergy between cKit and EpoR or other cytokine receptors has not been resolved.

The profound effects of SCF on proliferation and survival of different progenitor cell types has raised considerable interest in the identification of critical signal transduction pathways activated by cKit. SCF binding to cKit results in dimerization/oligomerization and subsequent transient tyrosine phosphorylation of the receptor.14 As a result, proteins of the p21Ras-MAPK pathway, the phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase (PI3-K), the tyrosine kinases Src/Fyn/Lyn and Tec, phospholipase Cγ-1 (PLCγ-1), Vav, Cbl, and p62Dok-1 are recruited to the cKit-signaling complex and are subsequently activated or phosphorylated.15-22 However, the mechanism by which these molecules are recruited and activated has remained largely unresolved. Although human and murine cKit contain 20 intracellular tyrosine residues, only a few were described as docking sites for signaling molecules when phosphorylated. Tyrosines 703 and 936 in human cKit bind the adapter molecules Grb2 and Grb7, whereas Src kinases bind to tyrosines 567 and 569 in the membrane proximal region, and p85 binds to tyrosine 719 in the kinase-insert domain of murine cKit.16,23,24 A concerted action of Src kinases and PI3-K appears to be required for the (indirect) activation of the small G-protein Rac and the protein kinase JNK, which is an important step in mast cell proliferation.24

In vitro studies have shown that activation of PI3-K contributes to survival, mitogenesis, chemokinesis, and differentiation induced by SCF.16,24-26 Introduction of cKit mutants unable to activate PI3-K into cKit-deficient mast cells does not restore SCF-induced cell adhesion and only partially restores SCF-induced proliferation.16 Furthermore, we recently observed that the PI3-K inhibitor LY294002 suppressed the biological effect of SCF on erythroid progenitors (manuscript in preparation). PI3-K yields PIP3 in the cell membrane, thereby creating binding sites for pleckstrin homology (PH) domain containing signaling molecules.27 The tyrosine kinase Tec is one such PH domain that contains protein activated by cKit.18 Tec is also the founding member of a family of tyrosine kinases that includes Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK), Bmx, Itk/Tsk/Emt, and Rlk/Txk.28,29 These kinases are characterized by a PH and a Tec homology (TH) domain in their amino-terminus, followed by SH3, SH2, and kinase domains.30 In contrast to Src kinases, they are devoid of a membrane-targeting myristylation site, and yet they are rapidly recruited to the plasma membrane after stimulation of various cytokine receptors, the T- and B-cell receptors, and CD28.31-35 The interaction between PIP3 and the PH domain of BTK is critical for this translocation.36 In the plasma membrane, Tec members are thought to be activated by Lyn or other members of the Src family.37,38 Other studies have shown that the TH domain of Tec is not only essential for the (in)direct interaction with cKit but also for its association with Lyn and Vav.33 39

In this study, we show that Tec is activated by SCF in erythroid and megakaryocytic cell lines and that, when activated, it forms a stable complex with various proteins, including the recently cloned docking protein p62Dok-1. We found that both the activation of Tec and the phosphorylation of Dok-1 require PI3-K activity. We show that the TH and SH2 domains of Tec mediate the interaction with Dok-1, whereas 2 separate domains in Dok-1 are involved in the interaction with Tec. We further show that Tec, and also Lyn, can phosphorylate Dok-1. Dok-1 contains 15 tyrosine residues, suggesting an important role for Dok-1 in recruiting SH2 domain-containing proteins to the cKit-signaling complex. In support of this hypothesis, we provide evidence that phosphorylated Dok-1 binds the SH2 domains of multiple signaling molecules.

Materials and methods

Cells, plasmids, and oligonucleotides

The human erythroleukemia cell lines F36P and TF-1 as well as the megakaryocytic cell line Mo7e were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium (Life Technologies, Breda, The Netherlands) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS; Life Technologies) and recombinant human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF; 5 ng/mL; Immunex; Seattle, WA). COS, 293, and amphotropic Phoenix cells were cultured in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM; Life Technologies) supplemented with 10% FCS.

The complete complementary DNAs (cDNAs) of murine Tec, human cKit, and human Dok-1 (a kind gift of N. Carpino, St Jude Children's Hospital, Memphis, TN) were cloned in the expression vector pSG5 (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) and the retroviral vector pBabe.40 The expression vectors encoding Tec mutants and Δp85 have been described previously.41 42 Constructs DokΔY1 and DokΔY5 were generated by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with the use of the oligonucleotides Dok-F (5′-CGGAATTCCCGGGGGCCATGGACGGA-3′), Dok-ΔY1 (5′-AAAACTGCAGGTTAACGGCTCTACAAGGAGTTCTCCAGC-3′), and Dok-ΔY5 (5′-AAAACTGCAGGTTAACCAGCCTACAGGGCTGGGGGACTG-3′) and the Expand High Fidelity PCR System (Roche; Basel, Switzerland). Fragments were cloned in the EcoRI/PstI sites of a modified pSG5. Constructs tagged with the hemagglutinin (HA) epitope, HA-Dok, HA-DokΔY5, and HA-DokΔY1, respectively, were generated by subcloning PCR products into pMT2SM-HA vector. The PstI fragment of pMT2HA-Dok was subcloned into pBABE to generate pBHA-Dok.

Transient transfection and viral transduction

For transfection experiments, COS cells were cultured in 6-well dishes (Costar; Corning, NY), and 293 cells were cultured in 20-cm2 dishes (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ). After 24 hours, the cells were transfected with 6 to 12 μg of supercoiled plasmid DNA as described previously.43 Sixteen to 20 hours after transfection, medium was refreshed, and cells were harvested 24 hours later.

For viral transduction experiments, amphotropic Phoenix cells were cultured in 6-well dishes and, 3 hours later, the cells were transfected with the use of calcium phosphate. After 48 hours, cells were treated with mitomycin C (10 μg/mL) for 1 hour, washed 3 times, and washed 3 more times 4 hours later. F36P cells (2 × 105/mL) were added and co-cultured for 20 to 24 hours in RPMI/DMEM medium (50%/50%). F36P cells were removed carefully from the Phoenix cells and cultured in RPMI 1640 medium. To select for stable transfected cells, puromycin (2 μg/mL) was added 48 hours later.

Immunoprecipitations, Western blotting, and antibodies

After serum starvation for 16 hours, F36P, Mo7e, and TF-1 cells (30 × 106/mL) were stimulated with SCF (100 ng/mL; a generous gift of Amgen, Thousand Oaks, CA), EPO (5 U/mL; a generous gift of Janssen-Cilag, Tilburg, The Netherlands), or GM-CSF (50 ng/mL), or left unstimulated for 5 minutes (SCF) or 10 minutes (EPO and GM-CSF) at 37°C. Reactions were stopped by adding ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Cells were lysed in lysis buffer (1% NP-40, 20 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 137 mmol/L NaCl, 10 mmol/L EDTA, and 10% glycerol), supplemented with Complete protease inhibitor mix [Roche], Pefablock [Merck, Darmstadt, Germany], and 1 mmol/L orthovanadate) on ice for 15 minutes and centrifuged at 4°C for 10 minutes at 15 000 rpm. Lysates of 15 × 106 cells were precleared with protein G beads (Sigma; St Louis, MO), incubated with the appropriate antibody (1 μg) for 90 minutes at 4°C, and protein G beads were added for an additional hour. Precipitates were washed 3 times with lysis buffer, subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and electrotransferred to nitrocellulose membrane (Schleicher & Schuell; Dassel, Germany). Membranes were blocked in 0.6% bovine serum albumin (BSA), incubated with appropriate antibodies, and developed with the use of enhanced chemoluminescence (ECL; NEN, Boston, MA).

The following antibodies were used in this study: anti-Tec (06-561; Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY), anti-TecSH3,31anti-Dok-1 (M19; Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA), antiphosphotyrosine (PY99; Santa Cruz), anti-HA (F-7; Santa Cruz), anti-Lyn (Transduction Laboratories, Lexington, KY), antiphospho-PKB (Ser473; New England BioLabs, Beverly, MA), anti-PKB (New England BioLabs), antiphospho-ERK1,2 (Thr202/Tyr204; E10; New England BioLabs), and anti-ERK1,2 (K-23; Santa Cruz).

Glutathione S-transferase (GST)-pull down experiments

For SH2 domain-inducing studies, SCF-stimulated Mo7e cells were lysed in immunoprecipitation buffer. Cleared lysates were incubated for 90 minutes with beads coupled to 10 μg of GST-SH2 fusion protein or to GST alone. Beads were washed 3 times with lysis buffer and resuspended in sample buffer. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and blotted with antiphosphotyrosine antibody. The GST fusions with SH2 domains of the following proteins were used in this study: cAbl, CrkL, Fgr, Fps, GAP (both N- and C-terminal SH2 domains [N+C]), Grb14, Hck, Lyn, p85 subunit of PI3-K (SH2 N+C), PLCγ-1 (SH2 N+C), Shc, SHIP, Src, Syk (SH2 N+C), Vav, and Yes.

Results

Tec is activated in erythroid cells and complexes with various proteins after SCF addition

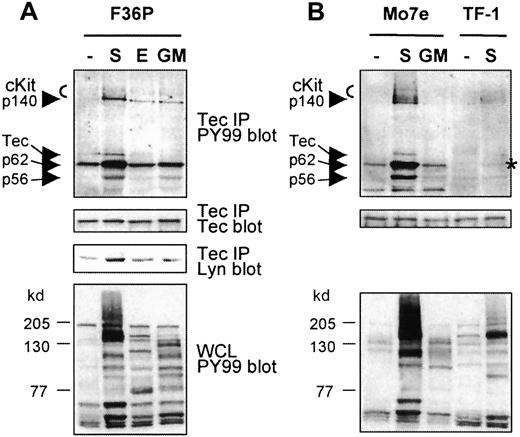

Tec has previously been shown to be activated by SCF in the human megakaryocytic cell line Mo7e.18 To investigate whether Tec is specifically activated on cKit activation and to identify associating proteins, Tec was immunoprecipitated from the human erythroid progenitor cell line F36P and was stimulated with SCF, EPO, or GM-CSF, from Mo7e cells stimulated with SCF or GM-CSF, and from human erythroleukemic TF-1 cells stimulated with SCF. Subsequently, Tec and coprecipitating proteins were immunoblotted with antiphosphotyrosine antibody (PY99). As shown in Figure1A, phosphorylation of Tec in F36P cells is only detected after SCF stimulation but not after incubation of the cells with EPO or GM-CSF, even though these cytokines induced tyrosine phosphorylation of multiple proteins (Figure 1A, lower panel). An in vitro kinase assay confirmed that the tyrosine phosphorylation of Tec correlated with enhanced kinase activity of Tec (not shown). Interestingly, a prominent phosphorylated protein of 62 kd as well as proteins of 145 to 150, 140, and 56 kd were precipitated with Tec after SCF induction. The proteins of 145 to 150 kd were identified as cKit by Western blot analysis (not shown). Because p56Lyn is known to associate with Tec,39 we tested whether the coprecipitating phosphoprotein of 56 kd was Lyn. Although the lower panel indeed shows that SCF treatment results in enhanced Tec-Lyn association, Lyn had a slightly faster mobility than p56. Therefore, the identities of p56 and p140 remain unknown.

Tec is activated in erythroid cells and complexes with various proteins following SCF addition.

(A, B) Tec was immunoprecipitated from F36P, Mo7e, and TF-1 cells incubated with SCF (S; 5 minutes), EPO, or GM-CSF (E, GM; 10 minutes) at 37°C. The immunoprecipitates (15 × 106 cells each) were analyzed by Western blotting with antiphosphotyrosine (PY99; top panels) and anti-Tec (middle panels). Tec precipitates from F36P cells were also analyzed with anti-Lyn (middle panel). As a control, whole cell lysates were analyzed with antiphosphotyrosine (lower panels). Tec is specifically phosphorylated by SCF and complexes with cKit and proteins of 56, 62, and 140 kd, following SCF addition (indicated by arrows). Co-precipitating p62 in SCF-stimulated TF-1 cells is marked with an asterisk.

Tec is activated in erythroid cells and complexes with various proteins following SCF addition.

(A, B) Tec was immunoprecipitated from F36P, Mo7e, and TF-1 cells incubated with SCF (S; 5 minutes), EPO, or GM-CSF (E, GM; 10 minutes) at 37°C. The immunoprecipitates (15 × 106 cells each) were analyzed by Western blotting with antiphosphotyrosine (PY99; top panels) and anti-Tec (middle panels). Tec precipitates from F36P cells were also analyzed with anti-Lyn (middle panel). As a control, whole cell lysates were analyzed with antiphosphotyrosine (lower panels). Tec is specifically phosphorylated by SCF and complexes with cKit and proteins of 56, 62, and 140 kd, following SCF addition (indicated by arrows). Co-precipitating p62 in SCF-stimulated TF-1 cells is marked with an asterisk.

Tec is also selectively phosphorylated by SCF in Mo7e cells (Figure1B). In these cells, a similar pattern of coprecipitating proteins is observed, indicating that the same signaling complex is formed after cKit activation in F36P and Mo7e cells. Although less clear, cKit and p62 (marked with an asterisk) were also detected in the Tec precipitates of SCF-stimulated TF-1 cells. The signal in these cells is less intensive, most likely due to the lower level of activated cKit when compared with F36P and Mo7e, as is apparent from the whole cell lysate controls.

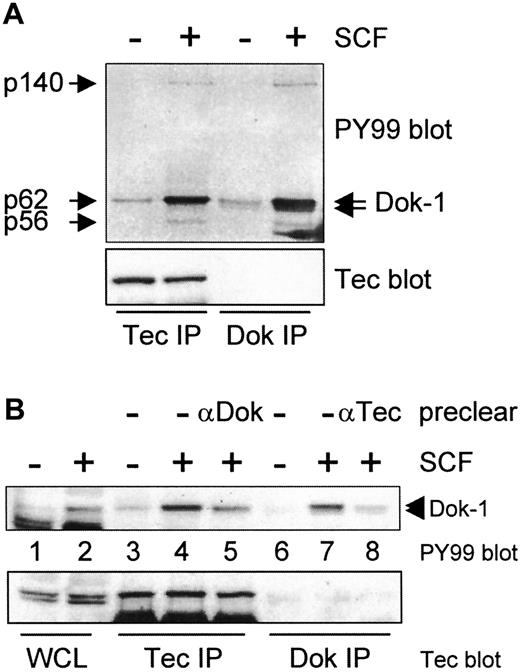

The p62 coprecipitating with Tec is p62Dok-1

The most prominent tyrosine phosphorylated protein in Tec precipitates is a protein of 62 kd. Recently, Dok-1, a docking protein of 62 kd, was cloned from chronic myelogenous leukemia progenitor cells and from v-Abl-transformed B cells.22 44 In these cells, Dok-1 is constitutively phosphorylated. To examine whether Tec-associated p62 is identical to Dok-1, both Tec and Dok-1 were precipitated from SCF-stimulated F36P cells, blotted, and incubated with PY99. Figure 2A shows that p62 exactly comigrates with the slower migrating species of Dok-1. Strikingly, proteins of 140 and 56 kd coprecipitate with Dok-1, similar to what is observed when Tec is immunoprecipitated. These results suggest that (partially) identical complexes are precipitated with anti-Tec and anti-Dok sera. Reprobing of the blot with anti-Tec serum showed that Tec was present in the Tec immunoprecipitations (Figure 2A, lower panel). However, Tec was never detected in Dok-1 precipitations, possibly due to sterical hindrance of the antibody. Therefore, we assume that the coprecipitating p56 and p140 associate with Dok-1 rather than with Tec.

The p62 coprecipitating with Tec is p62Dok-1.

(A) Tec and Dok-1 were immunoprecipitated from whole cell lysates of nonstimulated and SCF-incubated F36P cells and analyzed by Western blotting with antiphosphotyrosine (PY99; top panel) and anti-Tec (lower panel). Two species of Dok-1 are phosphorylated by SCF (indicated by arrows), of which the upper one comigrates with Tec-associated p62. Proteins of 56 and 140 kd are observed in both Tec and Dok-1 precipitates of SCF-treated cells (indicated by arrows). (B) Lysates of SCF-stimulated F36P cells were precleared with anti-Dok-1, followed by Tec immunoprecipitation, or vice versa. The lysates were analyzed by Western blotting with antiphosphotyrosine (top panel) and anti-Tec (lower panel). Pretreatment of the lysates reduces the amount of phosphorylated p62/Dok-1, indicating that p62 is identical to the slower migrating species of Dok-1.

The p62 coprecipitating with Tec is p62Dok-1.

(A) Tec and Dok-1 were immunoprecipitated from whole cell lysates of nonstimulated and SCF-incubated F36P cells and analyzed by Western blotting with antiphosphotyrosine (PY99; top panel) and anti-Tec (lower panel). Two species of Dok-1 are phosphorylated by SCF (indicated by arrows), of which the upper one comigrates with Tec-associated p62. Proteins of 56 and 140 kd are observed in both Tec and Dok-1 precipitates of SCF-treated cells (indicated by arrows). (B) Lysates of SCF-stimulated F36P cells were precleared with anti-Dok-1, followed by Tec immunoprecipitation, or vice versa. The lysates were analyzed by Western blotting with antiphosphotyrosine (top panel) and anti-Tec (lower panel). Pretreatment of the lysates reduces the amount of phosphorylated p62/Dok-1, indicating that p62 is identical to the slower migrating species of Dok-1.

The anti-Dok-1 antibody could not be used in Western blot analysis but worked well in immunoprecipitations. To demonstrate that p62 is indeed Dok-1, lysates of SCF-stimulated F36P cells were first cleared with anti-Dok-1, followed by a Tec precipitation, and vice versa. If Tec and Dok-1 associate, the signal of p62/Dok-1 should be decreased in Tec- and Dok-1-precleared precipitates. In fact, significantly less p62 coprecipitates with Tec in lysates precleared from Dok-1 (Figure 2B, lanes 4 and 5), whereas there is almost no p62Dok remaining in a Dok-1 precipitate after the lysate was precleared with anti-Tec (Figure 2B, lanes 7 and 8). Together, these data are consistent with the notion that the Tec-interacting protein of 62 kd is identical to Dok-1.

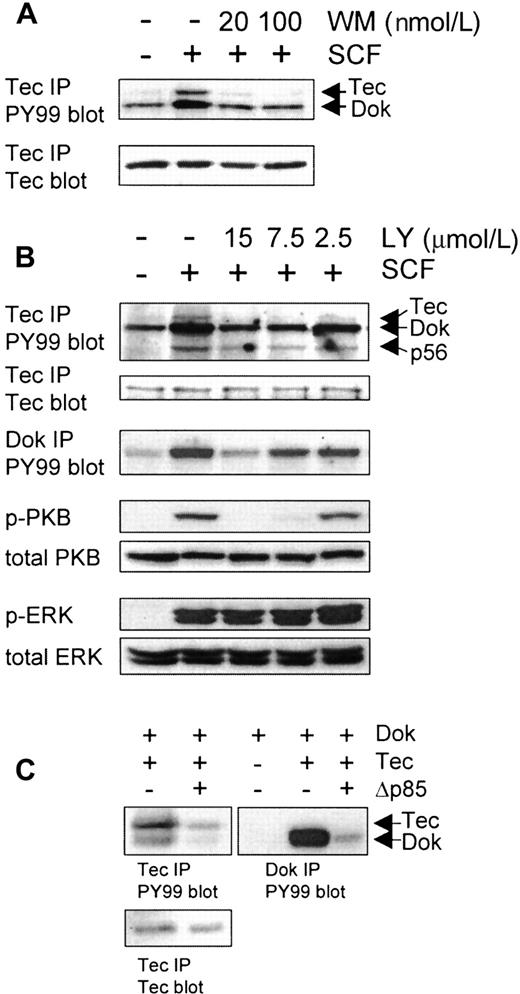

Tec and Dok phosphorylation depends on PI3-K activity

Like Tec, Dok-1 also contains a PH domain at its N-terminus, suggesting that recruitment of both proteins to the cKit-signaling complex could depend on PI3-K activation. To inhibit PI3-K activity, both the fungal metabolite wortmannin (WM) and the synthetic inhibitor LY294002 (LY) were employed. Pretreatment of the cells with 20 nmol/L WM (20 minutes) or 15 μmol/L LY (60 minutes) was sufficient to almost completely block the SCF-induced phosphorylation of Tec and the coprecipitating Dok-1 (Figure3A-B). As controls, phosphorylation of the classical PI3-K target, protein kinase B (PKB), and ERK were assessed. At 15 μmol/L LY, phosphorylation of PKB was completely blocked as determined with specific antibodies against phospho-PKB (Ser473; Figure 3B) and phospho-PKB (Thr308; not shown). In contrast, this concentration of LY had no effect on the SCF-induced activation of ERK1/2 (lower panel). These results demonstrate the specificity of the PI3-K inhibitors and suggest that PI3-K activation has to precede Tec/Dok phosphorylation, most likely to recruit these proteins to the signaling complex. In addition, because ERK1/2 phosphorylation is not affected by LY, it appears that SCF-induced activation of the Ras-MAP kinase pathway is independent of Dok-1 phosphorylation.

Tec and Dok phosphorylation depends on PI3-K activity.

F36P cells were incubated with different concentrations of the PI3-K inhibitors wortmannin (WM; 20 minutes; A) or LY294002 (LY; 60 minutes; B) at 37°C, after which the cells were incubated with SCF for 5 minutes. (A) Tec immunoprecipitates were analyzed by Western blotting with antiphosphotyrosine (top panel) and anti-Tec (lower panel). WM clearly inhibits Tec and Dok-1 phosphorylation. (B) Lysates were incubated with anti-Tec and anti-Dok-1. Tec immunoprecipitates were analyzed by Western blotting with antiphosphotyrosine and anti-Tec; Dok precipitates were analyzed with antiphosphotyrosine. LY clearly inhibits Tec and Dok-1 phosphorylation. Whole cell lysates (1 × 106 cells) were also analyzed with antiphospho-PKB and antiphospho-ERK as control for the specificity of LY. LY inhibits PKB phosphorylation but not ERK phosphorylation. (C) The 293 cells were transfected with expression vectors encoding Tec, Dok-1, or Δp85, or with empty vector (−). Tec and Dok-1 immunoprecipitates were analyzed by Western blotting with antiphosphotyrosine (top panels) and anti-Tec (lower left panel). Tyrosine phosphorylation of Tec and Dok-1 can be blocked by coexpression of dominant negative PI3-K (Δp85).

Tec and Dok phosphorylation depends on PI3-K activity.

F36P cells were incubated with different concentrations of the PI3-K inhibitors wortmannin (WM; 20 minutes; A) or LY294002 (LY; 60 minutes; B) at 37°C, after which the cells were incubated with SCF for 5 minutes. (A) Tec immunoprecipitates were analyzed by Western blotting with antiphosphotyrosine (top panel) and anti-Tec (lower panel). WM clearly inhibits Tec and Dok-1 phosphorylation. (B) Lysates were incubated with anti-Tec and anti-Dok-1. Tec immunoprecipitates were analyzed by Western blotting with antiphosphotyrosine and anti-Tec; Dok precipitates were analyzed with antiphosphotyrosine. LY clearly inhibits Tec and Dok-1 phosphorylation. Whole cell lysates (1 × 106 cells) were also analyzed with antiphospho-PKB and antiphospho-ERK as control for the specificity of LY. LY inhibits PKB phosphorylation but not ERK phosphorylation. (C) The 293 cells were transfected with expression vectors encoding Tec, Dok-1, or Δp85, or with empty vector (−). Tec and Dok-1 immunoprecipitates were analyzed by Western blotting with antiphosphotyrosine (top panels) and anti-Tec (lower left panel). Tyrosine phosphorylation of Tec and Dok-1 can be blocked by coexpression of dominant negative PI3-K (Δp85).

In addition to pharmacological inhibitors, a dominant negative PI3-K construct (Δp85) was used to determine the role of PI3-K in the phosphorylation of Tec and Dok-1. Tec, Dok-1, and Δp85 were transiently coexpressed in various combinations in 293 cells. Figure 3C shows that both Tec and Dok-1 are heavily phosphorylated on tyrosine residues when coexpressed. Interestingly, the phosphorylation of both Tec and coprecipitated Dok-1 is reduced when Δp85 is also transfected (lanes 1 and 2). Furthermore, immunoprecipitation of Dok-1 shows that the phosphorylation of Dok can also be blocked by cotransfection of Δp85 (lanes 4 and 5). This finding indicates that PI3-K activity is required for the phosphorylation of Tec and Dok-1 in 293 cells.

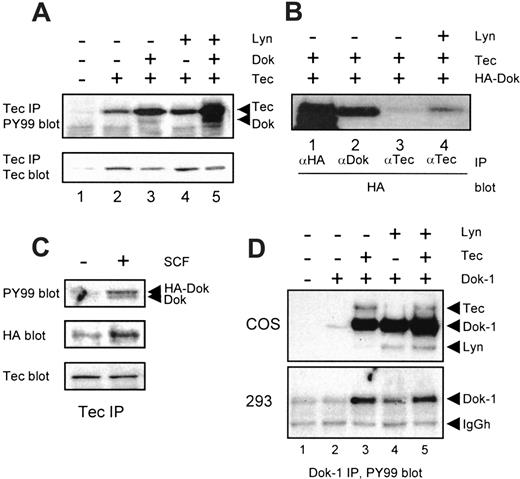

Dok-1 is a substrate of Tec and Lyn in 293 cells

To study the interaction of Tec and Dok-1, transient transfection experiments were performed in 293 cells as well as in COS cells. As shown in Figure 4A, immunoprecipitation of Tec from transfected cells results in the detection of a single phosphorylated protein, corresponding to Tec (lane 2). When Dok-1 is coexpressed (lane 3), a 62 kd phosphoprotein is coprecipitated, indicating that Tec and Dok-1 can form a complex in an overexpression system. However, relatively little phosphorylated Dok-1 is precipitated with Tec in this system when compared with F36P and Mo7e cells. Notably, coexpression of Dok-1 reproducibly enhanced the phosphotyrosine content of Tec (compare lanes 2 and 3), suggesting that Dok-1 enhances the auto- or cross-phosphorylation of Tec, or recruits an endogenous kinase that can phosphorylate Tec. The tyrosine kinase Lyn has been shown to phosphorylate Tec,37 and it was detected in a complex of Tec and Dok-1 in F36P cells (Figure 1A). Therefore, Lyn was coexpressed with Tec and Dok-1 in 293 cells. Lyn increased Tec phosphorylation (Figure 4A, compare lanes 2 and 4) and enhanced the intensity of Dok-1 detected by antiphosphotyrosine antibodies in a Tec immunoprecipitation (compare lanes 3 and 5). The latter may be due to Lyn-induced increased Dok-1 phosphorylation and/or increased stability of the Tec/Dok-1 complex. To examine an effect of Lyn on the Tec/Dok-1 interaction, Tec was coexpressed with a Dok-1 tagged at the N-terminus with the HA epitope, which allowed detection of total Dok-1 on Western blots. More HA-Dok was coprecipitated with Tec when Lyn was cotransfected (Figure 4B, lanes 3 and 4), suggesting that Lyn stabilizes the Tec/Dok-1 interaction. To analyze whether the association of Tec and Dok-1 is similarly enhanced through SCF-signaling, Tec was immunoprecipitated from F36P cells stably transfected with HA-Dok. Activation of cKit indeed increased the association of Dok-1 and Tec (Figure 4C). These data suggest that Lyn plays an important role in SCF-induced Tec/Dok-1 complex formation, which could be due to phosphorylation of Dok-1 that allows interaction of the Tec SH2 domain with the phoshotyrosines of Dok-1.

Dok-1 is a substrate of Tec and Lyn in 293 cells.

(A) The 293 cells were transfected with expression vectors encoding Tec, Lyn, or Dok-1, or with empty vector (−). Tec immunoprecipitates were analyzed by Western blotting with antiphosphotyrosine (top panel) and anti-Tec (lower panel). Dok-1 coprecipitates with Tec, especially in the presence of Lyn. (B) The 293 cells were cotransfected with HA-tagged Dok-1 and Tec, together with (+) or without (−) Lyn. Lysates were incubated with anti-HA, anti-Dok-1, or anti-Tec, after which the precipitates were analyzed with anti-HA. Lyn stabilizes the interaction between Tec and HA-Dok-1. (C) F36P cells were stably transfected with HA-Dok-1. Tec was precipitated from lysates of nonstimulated (−) or SCF-treated (+) cells, after which the precipitates were analyzed with antiphosphotyrosine (upper panel), anti-HA (middle panel), and anti-Tec (lower panel). More HA-tagged Dok-1 is precipitated after SCF stimulation, indicating that the association of Tec and Dok-1 is stabilized within the cKit-signaling complex. (D) COS cells (upper panel) and 293 cells (lower panel) were transfected with empty vector (−) or a Dok-1 expression plasmid (+), or cotransfected with Tec and/or Lyn. Dok-1 immunoprecipitates were analyzed by Western blotting with antiphosphotyrosine (top panel). In COS cells, both Tec and Lyn can phosphorylate Dok-1, whereas in 293 cells Dok-1 is a better substrate for Tec than for Lyn.

Dok-1 is a substrate of Tec and Lyn in 293 cells.

(A) The 293 cells were transfected with expression vectors encoding Tec, Lyn, or Dok-1, or with empty vector (−). Tec immunoprecipitates were analyzed by Western blotting with antiphosphotyrosine (top panel) and anti-Tec (lower panel). Dok-1 coprecipitates with Tec, especially in the presence of Lyn. (B) The 293 cells were cotransfected with HA-tagged Dok-1 and Tec, together with (+) or without (−) Lyn. Lysates were incubated with anti-HA, anti-Dok-1, or anti-Tec, after which the precipitates were analyzed with anti-HA. Lyn stabilizes the interaction between Tec and HA-Dok-1. (C) F36P cells were stably transfected with HA-Dok-1. Tec was precipitated from lysates of nonstimulated (−) or SCF-treated (+) cells, after which the precipitates were analyzed with antiphosphotyrosine (upper panel), anti-HA (middle panel), and anti-Tec (lower panel). More HA-tagged Dok-1 is precipitated after SCF stimulation, indicating that the association of Tec and Dok-1 is stabilized within the cKit-signaling complex. (D) COS cells (upper panel) and 293 cells (lower panel) were transfected with empty vector (−) or a Dok-1 expression plasmid (+), or cotransfected with Tec and/or Lyn. Dok-1 immunoprecipitates were analyzed by Western blotting with antiphosphotyrosine (top panel). In COS cells, both Tec and Lyn can phosphorylate Dok-1, whereas in 293 cells Dok-1 is a better substrate for Tec than for Lyn.

To examine whether Lyn is able to phosphorylate Dok-1 directly, Lyn and Tec were coexpressed with Dok-1 in COS and 293 cells. In COS cells, both Tec and Lyn induced massive Dok-1 phosphorylation, whereas they had an additive effect when cotransfected (Figure 4D, upper panel). Under these conditions, both Tec and Lyn coprecipitated with Dok-1 (indicated with arrows). In 293 cells, the SV40-driven promoter on the pSG5 plasmid is less active, resulting in a more modest expression of Tec and Lyn. In these cells, Dok-1 is a better substrate for Tec than for Lyn (Figure 4D, lower panel, lanes 3 and 4). Moreover, Lyn had no additive effect on Tec-mediated Dok phosphorylation (lane 5). Thus, although Lyn can phosphorylate Dok-1, its tyrosine phosphorylation appears to depend mainly on Tec activity.

In conclusion, activation of cKit stabilizes the interaction between Tec and Dok-1, possibly by Lyn-mediated Dok-1 phosphorylation. Subsequently, Tec phosphorylates Dok-1 to yield highly tyrosine-phosphorylated Dok-1.

Domains involved in Tec/Dok association

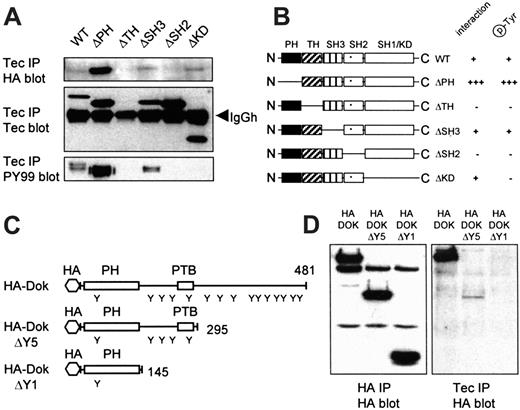

Given the interaction observed between Tec and Dok-1, we next examined which domains were involved. Wild-type (wt) Tec and Tec deletion constructs (see Figure 5B for a schematic representation) were coexpressed with HA-Dok-1 in 293 cells. Subsequently, Tec precipitates were blotted and probed with anti-HA- and antiphosphotyrosine antibodies. Wt Tec, TecΔSH3, and TecΔKD bind equal amounts of HA-Dok-1 (Figure 5A, upper panel). In contrast, TecΔPH is much more powerful in HA-Dok-1 binding, whereas no HA-Dok-1 is precipitated with TecΔTH and TecΔSH2. Similar results are obtained when the blot is probed with PY99, ie, an equal Dok-1 phosphorylation by wt Tec and TecΔSH3, enhanced phosphorylation with TecΔPH, and no phosphorylation with TecΔTH, TecΔSH2. The only difference concerned TecΔKD (no kinase activity), which failed in Dok-1 phosphorylation even though it precipitated HA-Dok-1, showing that indeed Tec kinase activity is responsible for the phosphorylation of HA-Dok-1. The detection of high levels of phosphorylated Dok-1 by TecΔPH is most likely due to enhanced Dok-1 binding (upper panel). Expression of Tec constructs was controlled with an antibody against the TH domain, therefore, TecΔTH could not be detected (Figure 5A). Staining the blot with an antibody against the SH3 domain of Tec showed that TecΔTH was expressed comparable to wt Tec (not shown). These data show that 2 independent domains of Tec, the TH domain and the SH2 domain, interact with Dok-1.

Domains involved in Tec/Dok association.

(A) The 293 cells were cotransfected with HA-Dok-1 and different Tec mutants. Tec immunoprecipitates were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-HA (top panel), anti-Tec (middle panel), and antiphosphotyrosine (lower panel). The TH and SH2 domains of Tec are crucial for the direct interaction with HA-Dok-1. (B) Schematic representation of the Tec mutants used and their Dok-1 interaction and phosphorylation properties. (C) Schematic representation of full-length HA-Dok-1, HA-DokΔY5, and HA-DokΔY1. Tyrosine residues (Y), the PH and PTB domains and total number of amino acids are indicated. (D) The 293 cells were cotransfected with Tec and different HA-Dok-1 deletion constructs. Lysates were incubated with anti-HA for expression control and with anti-Tec. Precipitates were analyzed with anti-HA. Although the HA-Dok deletion constructs are equally expressed (left panel), only full-length HA-Dok and a reduced amount of HA-DokΔY5 are detected in Tec precipitates (right panel), indicating that 2 domains in Dok-1 are involved in the binding to Tec.

Domains involved in Tec/Dok association.

(A) The 293 cells were cotransfected with HA-Dok-1 and different Tec mutants. Tec immunoprecipitates were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-HA (top panel), anti-Tec (middle panel), and antiphosphotyrosine (lower panel). The TH and SH2 domains of Tec are crucial for the direct interaction with HA-Dok-1. (B) Schematic representation of the Tec mutants used and their Dok-1 interaction and phosphorylation properties. (C) Schematic representation of full-length HA-Dok-1, HA-DokΔY5, and HA-DokΔY1. Tyrosine residues (Y), the PH and PTB domains and total number of amino acids are indicated. (D) The 293 cells were cotransfected with Tec and different HA-Dok-1 deletion constructs. Lysates were incubated with anti-HA for expression control and with anti-Tec. Precipitates were analyzed with anti-HA. Although the HA-Dok deletion constructs are equally expressed (left panel), only full-length HA-Dok and a reduced amount of HA-DokΔY5 are detected in Tec precipitates (right panel), indicating that 2 domains in Dok-1 are involved in the binding to Tec.

Dok-1 is a docking protein that contains a PH domain, a phosphotyrosine-binding (PTB) domain, 15 tyrosine residues, and 10 proline (PXXP) motifs. The phosphorylated tyrosines can act as SH2-binding sites, whereas the PXXP motifs mediate binding to SH3 domains. To roughly map the region(s) of Dok-1 that associate with Tec, 2 progressive deletion constructs were created (Figure 5C). In HA-DokΔY5, 193 amino acids were deleted at the C-terminus, which removes 10 tyrosine residues and 5 PXXP motifs. HA-DokΔY1 consists of only the PH domain, 1 tyrosine, and 2 PXXP motifs. The HA-Dok constructs were cotransfected with Tec in 293 cells. Lysates were incubated with anti-HA antibody as control (Figure 5D, left panel) and with anti-Tec to detect the Tec/Dok interaction (right panel). The interaction of Tec with full-length Dok-1 is easily detected, whereas no HA-DokΔY1 is observed in Tec precipitates. HA-DokΔY5 also associates with Tec, although at a low level, suggesting that 2 domains in Dok-1 cooperate in binding to Tec. Alternatively, multiple phosphotyrosines of Dok-1 are able to bind the SH2 domain of Tec.

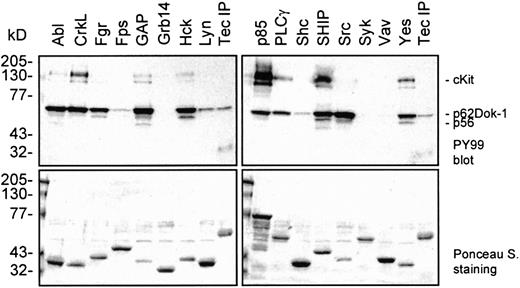

SH2 domains of distinct signaling molecules bind to phosphorylated Dok-1

We demonstrated that SCF induces the complex formation of Dok-1 with Tec and Lyn and that Dok-1 is subsequently phosphorylated on tyrosine residues. Phosphorylated tyrosines act as binding sites for SH2-containing proteins. To determine which signaling intermediates could bind to phosphorylated Dok-1, GST fusion proteins that contained the SH2 domains from a range of signaling molecules were incubated with lysate from SCF-stimulated Mo7e cells. The SH2 domains of the Src family members Src, Fgr, Hck, and Yes; the tyrosine kinase cAbl; the adapter CrkL; rasGAP (SH2 N+C); the p85 subunit of PI3-K (SH2 N+C); PLCγ (SH2 N+C); and SHIP bind efficiently to phospho-Dok-1 (Figure6). However, the SH2 domains of Fps, Grb14, Shc, Syk (SH2 N+C), and Vav show little or no association with Dok-1, illustrating a high level of substrate specificity. Precipitates that contain Dok-1 also include proteins of 145 to 150, 140, and 56 kd, although with different ratios. It cannot be excluded that some of the GST-SH2 fusion proteins directly bind to cKit and thereby indirectly precipitate Dok-1. However, these results strongly suggest that Dok-1 can recruit a variety of signaling proteins and, therefore, that Dok-1 may play an important role in SCF-mediated signaling.

SH2 domains of distinct signaling molecules bind to phosphorylated Dok-1.

GST-fusion proteins containing the SH2 domains of several signaling molecules were incubated with lysates of SCF-induced Mo7e cells. As a reference for p62Dok-1, a Tec immunoprecipitate was included. The precipitates were analyzed by Western blot analysis with an antiphosphotyrosine antibody (upper panels). The blots were stained with Ponceau S as a control for the amount of added GST-fusion protein (lower panels). Phosphorylated Dok-1 binds to the SH2 domains of various signaling intermediates.

SH2 domains of distinct signaling molecules bind to phosphorylated Dok-1.

GST-fusion proteins containing the SH2 domains of several signaling molecules were incubated with lysates of SCF-induced Mo7e cells. As a reference for p62Dok-1, a Tec immunoprecipitate was included. The precipitates were analyzed by Western blot analysis with an antiphosphotyrosine antibody (upper panels). The blots were stained with Ponceau S as a control for the amount of added GST-fusion protein (lower panels). Phosphorylated Dok-1 binds to the SH2 domains of various signaling intermediates.

Discussion

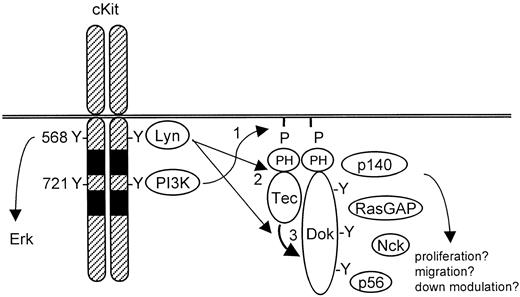

Various studies have shown that SCF-mediated proliferation, survival, adhesion, migration, and differentiation depend on PI3-K activity.16,24-26 PI3-K yields PIP3 in the cell membrane, which can subsequently recruit PH domain-containing signaling molecules.27 One such protein activated by SCF is the tyrosine kinase Tec. We found that activation of cKit induces both Tec activation and the formation of a complex of Tec with cKit, Lyn, p62Dok-1, and 2 unidentified proteins of 56 and 140 kd, respectively. By using pharmacological inhibitors and overexpression of Δp85, a dominant negative PI3-K construct, we determined that both complex formation and phosphorylation require PI3-K activity. The Δp85 transfection was done in a transient assay, because we failed to generate cell lines that stably expressed Δp85 or cKitY721F, a cKit mutant unable to activate PI3-K. We propose a model for Dok-1 in SCF signaling as shown in Figure 7. This model involves the activation of PI-3K and Src family members (eg, Lyn) following cKit stimulation. The PH domain-containing proteins Tec and Dok-1 are recruited to the plasma membrane where they colocalize with activated Lyn. Lyn associates with Tec and promotes its kinase activity. Subsequently, Tec and/or Lyn phosphorylate Dok-1, creating binding sites for SH2-containing proteins. It is possible that such Dok-1-interacting proteins are phosphorylated by Tec and/or Lyn as well.

Model for Tec/Dok-1 phosphorylation in SCF-induced signaling.

See “Discussion” section for details.

Model for Tec/Dok-1 phosphorylation in SCF-induced signaling.

See “Discussion” section for details.

Tec and Dok-1 are partially associated in nonstimulated serum-starved F36P and Mo7e cells (Figure 1), indicating that the interaction is relatively stable in vivo. In cotransfection studies, however, the Tec/Dok-1 association is rather weak, although Dok-1 is heavily phosphorylated by Tec when coexpressed (Figure 4A and 4D, respectively). With the use of an HA-tagged Dok-1 construct, it was shown that cKit stimulation stabilizes the association between Tec and Dok (Figure 4C). This implies that additional proteins are necessary to allow the formation of a stable complex. Our results suggest that Lyn is such a protein (Figure 4B). Furthermore, Lyn also phosphorylates Dok-1 (Figure 4D), whereas the SH2 domain of Tec is crucial for its association with Dok-1 (Figure 5A). One possible mechanism to explain these results is that Lyn phosphorylates a subset of tyrosines in Dok-1, including the one(s) that mediate(s) the interaction with Tec. In turn, Tec may phosphorylate another subset of tyrosines of Dok-1. To further clarify the role of Tec in the phosphorylation of Dok-1 in vivo, we tried to stably transfect F36P cells with a Tec construct that lacked its kinase domain. However, in all clones obtained the expression level of this mutant was too low to act as a dominant negative. It can, therefore, not be excluded that Src family members fully account for the phosphorylation of Dok-1 in vivo. During our studies, Tec was identified as a possible kinase for CD28-mediated Dok-1 phosphorylation, whereas a Dok-related protein (Dok-R or p56Dok-2) has been reported as a direct target of Lyn.35 45 These data are consistent with the conclusion that Dok-1 and Dok-related proteins are substrates for both the Tec and Src families of tyrosine kinases.

Dok-1 was first identified as a tyrosine-phosphorylated protein of 62 kd associated with p120-RasGAP in fibroblasts transfected with v-Src.46 In BCR-Abl-transformed cells, Dok-1 also binds to RasGAP in a tyrosine phosphorylation-dependent manner. However, RasGAP was not detected in Tec and Dok-1 precipitates, although RasGAP was detectable in RasGAP precipitates and in whole cell lysate controls (data not shown). In contrast, we detected a tyrosine-phosphorylated protein of 140 kd in Tec or Dok-1 precipitates of SCF-stimulated cells. Interestingly, a protein of about the same size was shown to bind to Dok-R in epidermal growth factor–stimulated cells.45 A protein that is activated by SCF and has a molecular weight of 150 kd is the inositol phosphatase SHIP-1. Therefore, we are currently investigating the role of this protein in the Dok-1 complex. In addition, the identity of p56 remains to be defined. Both p56Lyn and p52Shc are known to bind to Tec but have another electrophoretic mobility than Dok-bound p56 (data not shown).

Still little is known about the physiological role of Dok-1. Dok-1 is directly associated with v-Abl and constitutively phosphorylated in chronic myelogenous leukemia cells.44,47 Furthermore, the extent of tyrosine phosphorylation of Dok-1 has been shown to correlate with the transforming capacities of a number of different oncogenes, including v-Src, v-Fps, v-Fms, and v-Abl.46 Because of the frequently noted correlation between constitutive tyrosine phosphorylation of Dok-1 and cellular transformation, it has been suggested that Dok-1 plays an important role in mitogenic signaling. This idea is in agreement with the observations that Dok-1 is phosphorylated in response to SCF and that SCF primarily serves as a potent proliferation factor in hematopoietic progenitor cells. The results of other studies have suggested that Dok-1 may also play a role in cellular migration responses. Recently, Noguchi et al48showed that overexpression of wt Dok-1 enhanced insulin-induced migration, but this was not observed with DokY361F, a Dok-1 mutant unable to bind Nck. Nck is an adapter molecule that links receptors to p21cdc42/Rac-activated kinase and the Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein-interacting protein complex, all of which contribute to changes in the actin cytoskeleton.49,50 Furthermore, Rac has been shown to be activated by cKit via a Src- and PI3-K-dependent mechanism and plays an important role in SCF-induced proliferation of bone marrow-derived mast cells.24 One may speculate that the Tec/Dok-1 complex recruits and activates the components that regulate the (de)polymerization of actin filaments, thereby regulating cell migration.

Dok-1 contains a PTB domain, 15 tyrosine residues, and 10 PXXP motifs and has an overall structure related to the insulin-receptor substrates 1 to 4 and GAB, all of which serve as docking molecules.51By recruiting subsets of signaling molecules into an activated receptor complex, docking molecules play a key role in the coordination of the cellular response. Others22,48 have shown that p120RasGAP and Nck directly bind to Dok-1, whereas our results indicate that Tec as well as at least 2 unidentified proteins associate to Dok-1. We further showed that many SH2 domains of proteins functioning in different signaling routes form a complex with Dok-1. These include the SH2 domains of Abl, CrkL, PLCγ-1, SHIP as well as the p85 subunit of PI3-K, all proteins known to be activated by SCF.16,19,21,52 Because CrkL is a direct target of BCR-Abl,53 it is possible that Dok-1 plays a role in the recruitment of kinases (Tec, Lyn, Abl) and their substrates. With the notion that the pleiotropic effects of SCF largely depend on PI3-K, as is the phosphorylation of Dok-1, we postulate that Dok-1 (and its phosphorylation control) is an important regulator of SCF-induced signal transduction.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Nick Carpino, Paul Coffer, and Rolf de Groot for the kind gift of materials and plasmids, and Ivo Touw and Alister Ward for critically reading the manuscript and for useful discussions.

Supported by a grant from the Dutch Cancer Society (EUR 95-1021) and by a fellowship of the Dutch Academy for Arts and Sciences (KNAW) to M.v.L.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Thamar van Dijk, Institute of Hematology, Erasmus University Rotterdam, PO Box 1738, 3000 DR Rotterdam, The Netherlands; e-mail: vandijk@hema.fgg.eur.nl.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal