Abstract

The glycoprotein (Gp) IIb/IIIa integrin, also called CD41, is the platelet receptor for fibrinogen and several other extracellular matrix molecules. Recent evidence suggests that its expression is much wider in the hematopoietic system than was previously thought. To investigate the precise expression of the CD41 antigen during megakaryocyte (MK) differentiation, CD34+ cells from cord blood and mobilized blood cells from adults were grown for 6 days in the presence of stem cell factor and thrombopoietin. Two different pathways of differentiation were observed: one in the adult and one in the neonate cells. In the neonate samples, early MK differentiation proceeded from CD34+CD41− through a CD34−CD41+CD42− stage of differentiation to more mature cells. In contrast, in the adult samples, CD41 and CD42 were co-expressed on a CD34+ cell. The rare CD34+CD41+CD42− cell subset in neonates was not committed to MK differentiation but contained cells with all myeloid and lymphoid potentialities along with long-term culture initiating cells (LTC-ICs) and nonobese diabetic/severe combined immune-deficient repopulating cells. In the adult samples, the CD34+CD41+CD42−subset was enriched in MK progenitors, but also contained erythroid progenitors, rare myeloid progenitors, and some LTC-ICs. All together, these results demonstrate that the CD41 antigen is expressed at a low level on primitive hematopoietic cells with a myeloid and lymphoid potential and that its expression is ontogenically regulated, leading to marked differences in the surface antigenic properties of differentiating megakaryocytic cells from neonates and adults.

Introduction

Hematopoietic stem cells are a heterogeneous population of cells defined by both their multilineage potential and their hematopoietic reconstitution capacities after transplantation.1,2 In mice, biological assays have been developed to evaluate the repopulating capacity of a cell population and consequently its content in stem cells.3 Several in vitro assays have been designed in parallel to better characterize the hierarchy of hematopoietic primitive cells, which include true stem cells and early multipotential progenitors. One of these is the long-term culture initiating cell (LTC-IC) assay, which defines a population of primitive progenitors close to true hematopoietic stem cells.4-7 More recently, xenograft assays have been developed to test the engrafting capacities of human cells although the precise relationship between nonobese diabetic/severe combined immune-deficient (NOD-SCID) repopulating cells and long-term reconstituting human stem cells is still unknown.8-12

Definition of the hematopoietic hierarchy has been facilitated by the identification of differentiation antigens.13-16 It has been generally considered that primitive hematopoietic cells lack lineage markers, assuming that they appear after commitment or during late stages of differentiation. The glycoprotein (Gp) IIb integrin (αIIb, CD41b) associates with GpIIIa (β3, CD61) to form a complex (GpIIb/IIIa, CD41a) that functions as the fibrinogen receptor in platelets.17 For several years, CD41 has been considered a specific marker for the megakaryocyte (MK) lineage.18,19However, increasing evidence has suggested that CD41 may be expressed early during hematopoiesis. By means of cell sorting, cytoxicity, or immunolabeling of hematopoietic colonies, it has been shown in both the human and the mouse (1) that CD41 is expressed on a fraction of MK progenitors,20,21 (2) that CD41 may be present on multipotent progenitors (colony-forming unit [CFU]–GEMM or CFU-mix),22-24 and (3) that the progeny of burst-forming units–erythroid (BFU-E) could transiently express CD41.25,26 In order to study the expression of CD41, the team of Marguerie has chosen an original approach: the creation of transgenic mice with the thymidine kinase gene under the transcriptional control of the αIIb promoter.27-29 The depletion in progenitors obtained after ganciclovir treatment suggests that the αIIb promoter is transcriptionally active in pluripotent myeloid progenitors, in early stages of erythropoiesis, and all along the megakaryocytic differentiation as well as, to a lesser extent, in the early stages of myelo-monocytic differentiation and the late stages of erythropoiesis.28 Recently, it has been shown in chickens that GpIIb/IIIa is associated with intra-embryonic hematopoiesis and is expressed on all types of myeloid progenitors as well as on T-cell progenitors.30 This result suggests that in avians, GpIIb/IIIa expression is not restricted to myeloid lineages but is also present on lymphoid lineages.

In this study, we have shown that CD41 antigen is expressed on a fraction of LTC-ICs and NOD-SCID reconstituting cells as well as on cells with a B-, T-, and natural killer (NK)–lymphoid potential derived from cord blood cells. In adults, CD41 expression is more restricted and is essentially present on erythroid and MK progenitors, although the CD41+ cell population may include some LTC-ICs. CD42 (GpIbIX), which is considered to be a later marker of the megakaryocytic differentiation than CD41, is also detected on non-MK progenitors from cord blood.

Materials and methods

Antibodies

The following were used for either cell sorting or cytometry analysis: directly conjugated R-phycoerythrin (PE) anti-CD34 (HPCA-2) (Becton Dickinson; Mountain View, CA); R-PE-cyanin 5 (Cy5) anti-CD34 (Immunotech; Lumigny, France), R-PE anti-CD41b (anti-GPIIb/IIIa) (Pharmingen; San Diego, CA); fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) anti-CD42a (GPIX) (Becton Dickinson); R-PE anti-CD19 (Becton Dickinson), R-PE-Cy5 anti-CD56 (Immunotech, Glostrup, Denmark); peridinin chlorophyll protein (PerCP) anti-CD61 (Becton Dickinson); R-PE-anti-glycophorin A (GPA) (CLB-eryt 1 clone) (Caltag Laboratories, Burlingame, CA); FITC anti-CD45 (Immunotech); R-PE anti-CD11b (Immunotech); and FITC anti-CD15 (Lewisx, Dako) monoclonal antibodies (mAbs). FITC-, R-PE– and R-PE-Cy5–conjugated immunoglobulin G1 mAb (obtained from Becton Dickinson and Dako) were used as isotype controls.

Unconjugated Tab mAb (anti-CD41) was a generous gift from R. Mac Ever (Oklahoma City, OK). Alkaline-phosphatase–coupled polyclonal goat antibody against mouse immunoglobulin (Caltag) was purchased from Tebu (Le Perray-en-Yvelines, France).

Purification of CD34+ cells

After informed consent was given, an aliquot of leukapheresis was obtained from adult patients after mobilization for research purposes. Umbilical human blood cells were obtained from full-term deliveries under guidelines established by the institute ethical committee. Precursor cells were separated over a Ficoll-metrizoate gradient (Lymphoprep) (Nycomed Pharma, Oslo, Norway) to obtain an enriched fraction of mononuclear cells. CD34+cells were then isolated by means of the Miltenyi (Paris, France) immunomagnetic bead technique according to the manufacturer's protocol. The purity was about 90% after 2 passages through the column as estimated by flow cytometry.

In vitro liquid cultures of MKs from CD34+cells

CD34+ cells were grown for 6 days in serum-free Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium (Gibco, Paisley, Scotland), prepared as previously reported.31 The medium was supplemented with a combination of pegylated recombinant human MK growth and development factor (PEG-rHuMGDF 10 ng/mL; a generous gift from Kirin, Tokyo, Japan) and 50 ng/mL recombinant human stem cell factor (SCF) (a generous gift from Amgen, Thousand Oaks, CA).

Cell sorting of different CD41 subsets

MKs at different stages of differentiation were obtained after 6 days of culture. Cells were incubated with a mixture of a FITC anti-CD42a, R-PE anti-CD41a, and R-PE-Cy5 anti-CD34 mAbs for 30 minutes at 4°C in their culture medium. Cells were washed in culture medium and sorted according to their immunophenotype into 6 different populations as follows: CD34+CD41a−CD42a−, CD34+CD41a+CD42a−, CD34+CD41a+CD42a+, CD34−CD41a−CD42a−, CD34−CD41a+CD42a−, and CD34−CD41a+CD42a+, by means of a FACS Vantage cytometer (Becton Dickinson) equipped with an argon laser (Coherent Radiation, Palo Alto, CA) and a 100-μm nozzle. Each cell fraction was resorted in order to get a purity of greater than 97%.

Quantification of clonogenic progenitors in semisolid cultures

Serum-free fibrin clot assays.

Cultures were performed in serum-free fibrin clot assays in the presence of cytokines. Ingredients for serum-free cultures were similar to those of liquid cultures in which were added bovine plasma fibrinogen (1 mg/mL) (Sigma, St Louis, MO), 0.01 M ε amino caproic acid, and horse thrombin (6 × 10−3 U/mL) (Stago, Asnières, France). Cells were plated in triplicate at 300 cells per milliliter in the presence of PEG-rHuMGDF (10 ng/mL); SCF (50 ng/mL); interleukin (IL)–6 (100 U/mL), a generous gift from Dr S. Burstein (Oklahoma City, OK); granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) (2 ng/mL) (Amgen-Roche, Paris, France); and erythropoietin (Epo) (1 U/mL) from Janssen-Cilag (Issy les Moulineaux, France). Cultures were scored after 10 to 12 days. MK colonies were enumerated by an indirect immuno-alkaline phosphatase labeling technique using an anti-GpIIb mAb (Tab).21

Methylcellulose assays.

Erythroid (BFU-E) and granulocytic (CFU–granulo-monocytic [GM]) progenitors were quantified by means of previously described methylcellulose assays.32 Cultures were stimulated by addition of recombinant human (rHu) growth factors: PEG-rHuMGDF (10 ng/mL), SCF (50 ng/mL), G-CSF (20 ng/mL), IL-6 (100 U/mL), IL-3 (100 U/mL), and human Epo (1 U/mL). Hematopoietic progenitors were scored on day 12 by means of an inverted microscope.

Detection of LTC-ICs in the sorted fractions

The presence of LTC-ICs was assessed by culturing the sorted fractions on the murine MS-5 stromal cells as previously described.33 Cultures were initiated at limiting dilutions by plating 10 to 100 cells per well (96-well plates). Wells were maintained at 33°C, 5% CO2, and fed weekly by half medium change. The content in clonogenic progenitors of each well was assessed after 6 weeks in culture by plating nonadherent and adherent cells (recovered by trypsinization) in methylcellulose assay (see above) supplemented with IL-3, Epo, SCF, and G-CSF. We tested 20 wells per cell concentration of different cell fractions. A positive well was defined as a well that contained at least one clonogenic progenitor cell after 6 weeks in culture.

Simultaneous assessment of erythroid, MK, and granulo-monocytic differentiation

Cells from the different cell fractions were sorted individually by means of the automatic cloning design of the flow cytometer into 96-well tissue-culture plates. The medium was serum-free and contained a combination of 6 cytokines (SCF, IL-3, Epo, G-CSF, IL-6, and PEG-rHuMGDF).34 Plates were examined at days 11 to 13 and days 18 to 20 after incubation at 37°C in an air atmosphere supplemented with 5% CO2. Individual clones were analyzed by flow cytometry.

Simultaneous assessment of B, NK, and granulo-monocytic differentiation

The different cell fractions were incubated in 24- and 96-well plates precoated with confluent murine MS-5 cells in RPMI supplemented with 10% human serum, 5% fetal calf serum (FCS), and a combination of 7 cytokines (10 ng/mL IL-3; 50 ng/mL SCF; 50 ng/mL fetal liver tyrosine kinase–3 ligand [FLT3-L], a generous gift from Immunex; 10 ng/mL PEG-rHuMGDF; 5 ng/mL IL-2; 10 ng/mL IL-15; and 20 ng/mL IL-7) (the last 3 cytokines were from Diaclone). Wells with significant cell proliferation were collected after 4 to 6 weeks, and cell phenotype was determined by flow cytometry.35

Assessment of T-cell potential in fetal thymus organ culture (FTOC)

Isolation of murine embryonic NOD-SCID thymic lobes, incubation with human cells by means of the hanging drop procedure, and organotypic cultures were performed following standard procedures initially described to analyze mouse T-lymphoid differentiation and adapted to the identification of human T-cell potential.36The standard technique has been slightly modified by adding a combination of cytokines (5 ng/mL IL-2; 20 ng/mL IL-7; and 50 ng/mL SCF) during the hanging drop procedure.35 Cells recovered from the thymic lobes after about 30 days were studied by immunofluorescence and analyzed by flow cytometry.35

Assessment of the ability of hematopoietic cells to engraft NOD-SCID

NOD/LtSz-scid /scid mice were irradiated with a single dose of 300 cGy from an x-ray source (Philips, Eindhoven, The Netherlands) before transplantation. Mice were anesthesized shortly thereafter with ether, and cultured cells of different phenotypes were injected in the retro-orbital vein. Long bones from the recipient mice were analyzed after 5 to 8 weeks by flow cytometry. A mouse was considered positive if at least 0.1% human cells (CD45+) were detected in comparison with the isotype control.

Immunolabeling for flow cytometric analysis

Individual clones were simultaneously labeled with a PerCP anti-CD61, R-PE anti-GPA, and FITC anti-CD15 mAbs to estimate erythroid, MK, and granulo-monocytic differentiation; Cy5/R-PE anti-CD56, R-PE anti-CD19, and FITC anti-CD15 mAbs for evaluation of B, NK, and granulo-monocytic differentiation; and R-PE anti–human CD4 and FITC anti–human CD8 in FTOC assays. These 2 antibodies recognized exclusively human cells.

The presence of human cells in NOD/SCID mouse bone marrow was studied after labeling with a FITC–anti-human CD45 mAb. To determine the precise phenotype of human cells, double or triple staining was performed by means of the FITC anti-CD45 mAb, FITC anti-CD15, an R-PE-Cy5 anti-CD34 mAb, and an R-PE anti-CD19, anti-CD11b, or anti-CD41 mAb. The phenotype was determined in a gate that was the intersection of a morphological (scatter properties) and a CD45+ gate.

Cell samples were analyzed on a FACSort (Becton Dickinson). Cells were analyzed with the Cellquest software package (Becton Dickinson).

Results

Immunophenotypic characterization of CD41+ cells deriving from adult and cord blood CD34+ cells

CD34+ cells from cord blood or leukapheresis were cultured in the presence of SCF plus PEG-rHuMGDF. As previously demonstrated,37 38 a high percentage of CD41+cells were present after 6 days of culture with a wide diversity in its expression. Triple staining with anti-CD34, anti-CD41, and anti-CD42 antibodies was performed as illustrated in Figure1A-C. A direct linear relationship between expression of CD41 and CD42 was observed (Figure 1A). Thus, only cells expressing a low level of CD41 (CD41+) were devoid of CD42 (see gate R2). In contrast, intermediate or high expression of CD41 (CD41++) correlated with the presence of CD42 (see gate R3). These results were obtained with both neonate and adult cells. The CD41+CD42− cells include both CD34+ and CD34− cells. CD34+ cells co-expressing both CD41 and CD42 (CD34+CD41++CD42+) were also detected. Striking differences were observed between adult and neonate cultures because at day 6 the great majority of CD41+ cells were CD34+ in the adult culture (Figure 1B, gates R2 + R3) and CD34− in the neonate culture (Figure 1A, gates R2 + R3). This suggests that differentiation may proceed along different pathways in the adult and the neonate.

Flow cytometric analysis of CD34+ cells from cord blood or mobilized adult blood after different days of culture in the presence of SCF and PEG-rHuMGDF.

(A) Triple staining of cultured adult and neonate CD34+cells at day 6 after stimulation by SCF and PEG-rHuMGDF. Gate R2 in yellow corresponds to CD41+CD42− cells, and R3 in pink to CD41+CD42+ cells. In the 2 last panels (gates R2 + R3), the expression of CD34 and CD42 in the CD41+ cells is compared in neonates and adults. (B) Cord blood (neonate) or mobilized (adult) CD34+ cells were labeled after purification (D0) or daily from day 2 to day 5 with antibodies against CD34 and CD41. The CD41 antigen on fresh cord blood CD34+ cells partly corresponds to platelet fragments and diminishes after neuraminidase or elastase treatment. In the CD34-CD41 plot, 9.74% and 6.8% correspond to the CD34+CD41+CD42− cell population. (C) Schematic pathways for acquisition of CD41 and CD42 surface antigens from CD34+ cells in neonates and adults.

Flow cytometric analysis of CD34+ cells from cord blood or mobilized adult blood after different days of culture in the presence of SCF and PEG-rHuMGDF.

(A) Triple staining of cultured adult and neonate CD34+cells at day 6 after stimulation by SCF and PEG-rHuMGDF. Gate R2 in yellow corresponds to CD41+CD42− cells, and R3 in pink to CD41+CD42+ cells. In the 2 last panels (gates R2 + R3), the expression of CD34 and CD42 in the CD41+ cells is compared in neonates and adults. (B) Cord blood (neonate) or mobilized (adult) CD34+ cells were labeled after purification (D0) or daily from day 2 to day 5 with antibodies against CD34 and CD41. The CD41 antigen on fresh cord blood CD34+ cells partly corresponds to platelet fragments and diminishes after neuraminidase or elastase treatment. In the CD34-CD41 plot, 9.74% and 6.8% correspond to the CD34+CD41+CD42− cell population. (C) Schematic pathways for acquisition of CD41 and CD42 surface antigens from CD34+ cells in neonates and adults.

To demonstrate this hypothesis, kinetics were performed, and cells were labeled every day starting on the day of purification to day 6 (Figure1B). On freshly purified cells, the precise percentage of CD34+CD41+ cells was sometimes difficult to determine owing to platelet fragment binding, which could not be totally eliminated either by neuraminidase or elastase treatment. From day 2 to day 3, the percentage of CD41+ cells derived from cord blood was low (up to 10%) and was present on CD34+cells with an intermediate level of antigen. At day 4, the CD41+ cells switched to a CD34− phenotype. At days 5 and 6 (Figure 1A), some of them increased their expression of CD41 and began to exhibit the CD42 antigen. In contrast, in adult culture, the CD41+ cells expressed a high level of CD34 until day 6, and the CD42 antigen appeared on CD34highCD41++ cells.

Thus, different pathways of early megakaryocytic differentiation occurred in the adult and the neonate cultures, as illustrated schematically in Figure 1C, and leads to a common mature phenotype (CD34−CD41++CD42++).

The percentage of cells expressing the different antigenic combinations at day 6 varied from one experiment to another, but differences between adult and neonate cultures were constantly observed, as shown in Figure 1A (n = 15). In cord blood cultures, the percentage of CD34+CD41+CD42−ranged from 1% to 3% and was decreased in comparison with adult cell cultures (10% to 25%). In contrast, CD34−CD41+CD42− was much more abundant in cord blood than in adult cultures (10% to 20% vs 0.5% to 2%); the same was true for CD34−CD41− cells. Later in culture (days 7 to 9), the number of cells with a mature MK phenotype (CD34−CD41++CD42+ or CD34−CD41++CD42++) greatly increased.

To precisely determine the properties of those cells, the different cell fractions were sorted at day 6 of culture and studied by biological assays.

Expression of the CD41 antigen on hematopoietic clonogenic progenitors

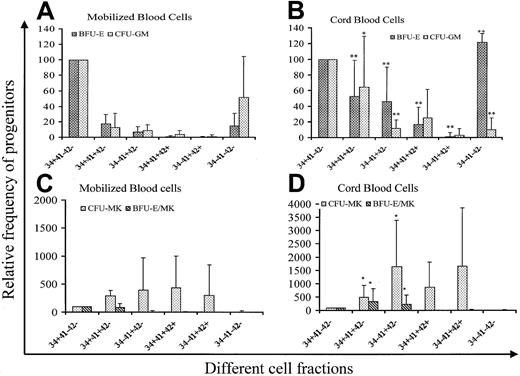

Cells were sorted according to the expression of CD34, CD41, and CD42 into 6 cell fractions (CD34+CD41a−CD42a−, CD34+CD41a+CD42a−, CD34−CD41a−CD42a−, CD34−CD41a+CD42a−, CD34+CD41a++CD42a+, and CD34−CD41a++CD42a++) at day 6 of culture and grown in methylcellulose in the presence of 5 cytokines to reveal their erythroid and myeloid potential and in plasma clot to reveal their erythro-MK potential. Results of 10 experiments performed from both mobilized adult blood and cord blood cells are summarized in Figure 2. Cloning efficiency of CFU-GM, BFU-E, CFU-MK, and BFU-E/MK was quite similar in the CD34+CD41−CD42− cell fractions from adult and cord blood samples (219.4/103, 112.7/103, 45.4/103, and 26.3/103for BFU-E, CFU-GM, CFU-MK and BFU-E/MK for leukapheresis vs 184.4/103, 107/103, 34.7/103, and 15.6/103 for cord blood). Thus, cloning efficiency in each fraction was referred to the cloning efficiency of this cell fraction. In the adult blood, non-MK progenitors were essentially found in the CD34+CD41−CD42− cell population. However, some BFU-E and CFU-GM (less than 20% of the CD34+CD41−CD42− cell cloning efficiency) were found in the 2 cell fractions expressing CD41 but not CD42, irrespective of CD34 expression. Surprisingly, progenitors were also present in the CD34−CD41−CD42− cell fraction, especially CFU-GM (50% of the CD34+CD41−CD42− cell cloning efficiency). In cord blood, non-MK progenitors have a higher cloning efficiency in all the CD41+ cell fractions except the CD34−CD41+CD42+ cell fractions than in the adult blood. Furthermore, non-MK progenitors, essentially erythroid progenitors, were present in cell fractions expressing CD42. All these differences were statistically significant, and cloning efficiency of the CD34+CD41+CD42−cell population for BFU-E and CFU-GM was about 60% that found in the CD34+CD41−CD42− cell fraction. In contrast to the adult blood cells, BFU-E were enriched in the cultured CD34−CD41−CD42− cell fraction. Differences were also observed for MK progenitors. Indeed, MK progenitors and the erythro/MK progenitor (BFU-E/MK) were significantly enriched in the CD34+CD41+CD42+ and CD34−CD41+CD42− cell fractions in comparison with the adult blood cells. In both the adult and neonate blood cells, MK colonies derived from the fractions expressing CD42 were composed of very few cells.

Analysis of the progenitor content in different cell fractions purified on the expression of CD34, CD41, and CD42.

CD34+ cells were purified from cord blood and adult mobilized blood and cultured for 6 days in serum-free medium in the presence of SCF (50 ng/mL) and PEG-rHuMGDF (10 ng/mL) and sorted on 6 fractions according to the CD34, CD41, and CD42 expression. Cells were grown in methylcellulose in the presence of PEG-rHuMGDF, SCF, G-CSF, IL-6, IL-3, and Epo for CFU-GM and BFU-E assays, and in fibrin clot in the presence of PEG-rHuMGDF, SCF, IL-6, G-CSF, and Epo for CFU-MK and BFU-E/MK assays. Experiments were performed in triplicate. Results presented are derived from 10 different samples. Cloning efficiency of the CD34+CD41−CD42− cell fraction was quite similar in samples from cord blood and adult blood (219.4/103, 112.7/103, 45.4/103, and 26.3/103 for BFU-E, CFU-GM, CFU-MK, and BFU-E/MK for leukapheresis vs 184.4/103, 107/103, 34.7/103, and 15.6/103 for cord blood). Thus, cloning efficiency in each fraction was referred to that observed in the CD34+CD41−CD42− cell fraction and expressed as a percentage. P was calculated by the student t test: *.01 < P < .05; **P < .01.

Analysis of the progenitor content in different cell fractions purified on the expression of CD34, CD41, and CD42.

CD34+ cells were purified from cord blood and adult mobilized blood and cultured for 6 days in serum-free medium in the presence of SCF (50 ng/mL) and PEG-rHuMGDF (10 ng/mL) and sorted on 6 fractions according to the CD34, CD41, and CD42 expression. Cells were grown in methylcellulose in the presence of PEG-rHuMGDF, SCF, G-CSF, IL-6, IL-3, and Epo for CFU-GM and BFU-E assays, and in fibrin clot in the presence of PEG-rHuMGDF, SCF, IL-6, G-CSF, and Epo for CFU-MK and BFU-E/MK assays. Experiments were performed in triplicate. Results presented are derived from 10 different samples. Cloning efficiency of the CD34+CD41−CD42− cell fraction was quite similar in samples from cord blood and adult blood (219.4/103, 112.7/103, 45.4/103, and 26.3/103 for BFU-E, CFU-GM, CFU-MK, and BFU-E/MK for leukapheresis vs 184.4/103, 107/103, 34.7/103, and 15.6/103 for cord blood). Thus, cloning efficiency in each fraction was referred to that observed in the CD34+CD41−CD42− cell fraction and expressed as a percentage. P was calculated by the student t test: *.01 < P < .05; **P < .01.

To determine the myeloid potential of these CD41+ cells in more detail, limiting dilution experiments were performed with cord blood or adult cells.

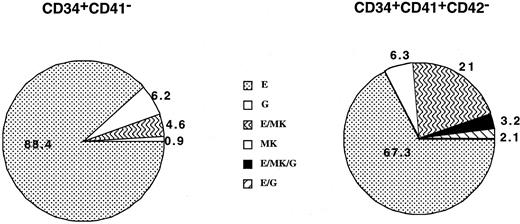

Expression of CD41 antigen on pluripotent myeloid progenitors

Cells from the CD34+CD41− and CD34+CD41+CD42− cell fractions were deposited at one cell per well by means of the automated cell deposition unit of the flow cytometer and cultured from 10 to 13 days. Each well, which comprises more than 200 cells, was immunophenotyped by triple staining. This procedure enabled us to define precisely the MK (CD61high cells with high FCS and SSC), erythroid (GPA), and granulo-monocytic (CD15) potential of each clone. Results of cord blood cultures obtained from 4 separate experiments and derived from 112 and 95 wells are illustrated in Figure3. Cloning efficiency was slightly lower in the CD34+CD41+CD42− cell population than in the CD34+CD41− (35% vs 28%). All potentialities could be found in the CD34+CD41+ cells, including progenitors with a erythro/granulo-monocytic/MK potential. It must be emphasized that in these experiments the frequency of MK progenitors was greatly underestimated owing to the number of cells required for the flow cytometric analysis (more than 200 cells). In contrast, in the adult, almost all clones derived from CD34+CD41+CD42− and containing more than 200 cells were purely erythroid or mixed erythro/MK. The cloning efficiency was low (about 5%) in the CD34+CD41+CD42− cell population as compared with the CD34+CD41− (32%) (data not shown).

Analysis of the cell composition of individual clones derived from the CD34+CD41− and CD34+CD41+CD42− cells derived from cord blood at day 11 of culture.

The results presented are those obtained from 4 independent experiments that have been pooled, representing analysis of 112 and 95 clones, respectively. Culture conditions were serum-free plus a combination of cytokines (PEG-rHuMGDF, SCF, Epo, G-CSF, IL-3, and IL-6). Only clones having more than 200 cells were analyzed on the expression of CD15, CD41, and GPA in triple-staining experiments by means of flow cytometry. Each cell type was identified on the basis of phenotypic and scatter properties.

Analysis of the cell composition of individual clones derived from the CD34+CD41− and CD34+CD41+CD42− cells derived from cord blood at day 11 of culture.

The results presented are those obtained from 4 independent experiments that have been pooled, representing analysis of 112 and 95 clones, respectively. Culture conditions were serum-free plus a combination of cytokines (PEG-rHuMGDF, SCF, Epo, G-CSF, IL-3, and IL-6). Only clones having more than 200 cells were analyzed on the expression of CD15, CD41, and GPA in triple-staining experiments by means of flow cytometry. Each cell type was identified on the basis of phenotypic and scatter properties.

Expression of CD41 antigen on primitive hematopoietic cells (LTC-ICs and NOD-SCID repopulating cells)

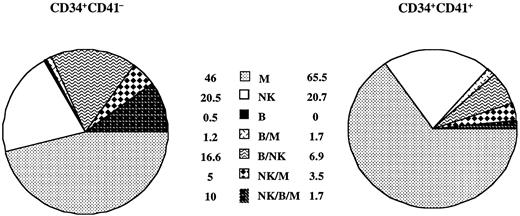

Consequently, we investigated whether the CD41 antigen was expressed on primitive hematopoietic cells revealed by the LTC-IC assay. LTC-ICs were detected in the CD34+CD41−CD42− and CD34+CD41+CD42− cell fractions but not in the CD34−CD41+CD42−cell subset in samples from cultured cord blood and adult mobilized CD34+ cells. The LTC-IC frequency was reduced about 4- and 2-fold in the CD34+CD41+CD42− cell fraction in comparison with the CD34+CD41− cell fraction from the adult and neonate samples, respectively (1/38 vs 1/138; 1/30 vs 1/65) (Figure4A). In absolute number, when the frequency of each cell fraction was taken into account, the LTC-ICs contained in the adult or neonate CD34+CD41+CD42− cell subset in comparison with those contained in the CD34+CD41− cell fraction was in the same order of magnitude (8.9% in the neonate and 8.5% in the adult cells).

Presence of primitive hematopoietic cells among CD41+ cells.

(A) LTC-IC assay. Proportion of negative wells in the LTC-IC assays at week 6. The frequency of LTC-ICs from cultured cord blood and adult mobilized CD34+ cells was calculated in the CD34+CD41−, CD34+CD41+CD42−, and CD34−CD41+CD42− cell fractions. (B) Phenotypic analysis of the human cells present in NOD-SCID cells 6 weeks after reconstitution with CD34+CD41− and CD34+CD41+ cells derived from cultured cord blood CD34+ cells. A triple staining was performed between a FITC anti-CD45 mAb, an R-PE-Cy5 anti-CD34 mAb, and R-PE anti-CD19, or CD11b or CD41 mAb. All these antibodies were human specific. The phenotype of human cells could be determined by gating cells on both their scatter properties and CD45 expression.

Presence of primitive hematopoietic cells among CD41+ cells.

(A) LTC-IC assay. Proportion of negative wells in the LTC-IC assays at week 6. The frequency of LTC-ICs from cultured cord blood and adult mobilized CD34+ cells was calculated in the CD34+CD41−, CD34+CD41+CD42−, and CD34−CD41+CD42− cell fractions. (B) Phenotypic analysis of the human cells present in NOD-SCID cells 6 weeks after reconstitution with CD34+CD41− and CD34+CD41+ cells derived from cultured cord blood CD34+ cells. A triple staining was performed between a FITC anti-CD45 mAb, an R-PE-Cy5 anti-CD34 mAb, and R-PE anti-CD19, or CD11b or CD41 mAb. All these antibodies were human specific. The phenotype of human cells could be determined by gating cells on both their scatter properties and CD45 expression.

In order to determine if the cells bearing the CD41 antigen may be transplantable in vivo, 3 cord blood cell fractions (CD34+CD41−CD42−, CD34+CD41+CD42−, and CD34−CD41+CD42− cells) were injected in NOD-SCID mice (80 000 to 150 000 cells per mouse) in 4 separate experiments. No human cells could be detected when the CD34−CD41+CD42− cells were transplanted whereas the 2 other cell fractions had reconstituting capabilities. Nonetheless, the percentage of positive mice and the percentage of human hematopoietic cells in the mice were slightly lower after injection of CD34+CD41+CD42−cells than with the CD34+CD41− cells. Indeed, 9 out of 10 and 6 out of 10 mice were positive for human cells after injection of CD34+CD41−CD42− or CD34+CD41+CD42− cells, respectively. The level of reconstitution varied greatly, from low at the threshold of detection (0.2%) for both cell fractions, to high (75% for CD34+CD41− cells and 55% for CD34+CD41+CD42− cells).

Phenotypic analysis of the human hematopoietic cells reconstituted with these 2 cell fractions was not markedly different, and CD19+ cells were the predominant cell population in the mice (Figure 4B). This clearly suggests that CD34+CD41+ cells also have a B-lymphoid potential.

NOD-SCID repopulating experiments were performed with mobilized blood CD34+ in 2 experiments. The level of reconstitution was low at the threshold of detection (0.8%) with both cell fractions (CD34+CD41− and CD34+CD41+CD42− cells). This may be due to the high number of cells necessary for such assays using adult cells.39

B-cell and NK-cell differentiation potential of CD41+ cells

To more precisely ascertain that CD41 antigen may be expressed on lymphoid progenitors, cord blood CD34+CD41−and CD34+CD41+CD42− cells were grown on the murine stromal cell line MS-5 in the presence of a combination of 7 cytokines (SCF, IL-3, FLT3-L, PEG-2HumGDF, IL-15, IL-7, and IL-2) for 4 to 6 weeks. Experiments were performed at one cell per well, comparing the CD34+CD41− and the entire CD34+CD41+ cell fractions. Frequency of proliferating cells (more than 200 cells) was 3-fold less in the CD34+CD41+ cell fraction than in the CD34+CD41− cell fraction (58 of 1080 vs 180 of 1068) at 4 or 6 weeks. These proliferating clones were immunophenotyped. All types of potentialities except pure B cells were found in the CD34+CD41+ cell fractions, including cells with the 3 potentialities (NK/M/B) (Figure5). In the adult cells, similar experiments were performed. However, the cloning efficiency of CD34+CD41+CD42− cells in lympho-myeloid conditions was extremely low (about 0.3% on 2000 clones studied), and wells contained only myeloid cells (CD15high).

Analysis of the progeny of single CD34+CD41− and CD34+CD41+ cell subpopulation from cultured blood cord cells.

Proportions were calculated as the percentage of clones containing 1, 2, or 3 lineages per total number of clones analyzed by triple staining in flow cytometry. Myeloid cells correspond to CD15+ cells, B cells to CD19+ cells, and NK cells to CD56+cells. The results are the sum of 2 independent experiments analyzed by flow cytometry representing 180 positive clones in 1068 plated wells for CD34+CD41− cells and 58 positive clones in 1080 plated wells for CD34+CD41+ cells.

Analysis of the progeny of single CD34+CD41− and CD34+CD41+ cell subpopulation from cultured blood cord cells.

Proportions were calculated as the percentage of clones containing 1, 2, or 3 lineages per total number of clones analyzed by triple staining in flow cytometry. Myeloid cells correspond to CD15+ cells, B cells to CD19+ cells, and NK cells to CD56+cells. The results are the sum of 2 independent experiments analyzed by flow cytometry representing 180 positive clones in 1068 plated wells for CD34+CD41− cells and 58 positive clones in 1080 plated wells for CD34+CD41+ cells.

T-lymphoid potential of CD41+ cells

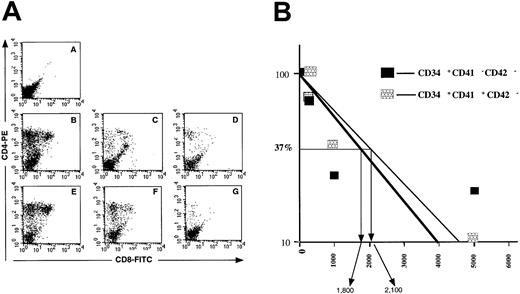

These experiments demonstrated that the CD41 antigen is present on cord blood cells with a lymphoid potential (B and NK). However, it remained to be determined if the CD34+CD41+also had a T-cell potential. NOD-SCID embryonic thymus can be used to reveal the T-cell potential of human CD34+cells.35 40 Using this strategy, we investigated the T-cell potential of the CD34+CD41−, CD34+CD41+CD42−, and CD34−CD41+CD42− cord blood cells. First, 25 000 cells were used in the hanging drop procedure; cells were recovered after 4 weeks of culture and characterized with antibodies against human CD4 and CD8. In these conditions, CD34+CD41−CD42− and CD34+CD41+CD42− cells generated T cells (CD4+ and double-positive CD4+/CD8+ cells) in all thymic lobes whereas the CD34−CD41+CD42− cell fraction did not have this potential (Figure 6A). Limiting dilution experiments were then performed with the 2 first fractions and revealed that the frequency of cells with a T-cell potential was quite similar in the CD34+CD41−CD42− and CD34+CD41+CD42− cells (Figure 6B). These experiments were not performed with adult cells.

Assessment of the T-cell potential of CD34+CD41−, CD34+CD41+CD42−, and CD34−CD41+CD42− cells from cord blood–cultured CD34+ cells.

(A) Cells extracted from each thymic lobe were labeled by R-PE anti–human CD4 and FITC anti–human CD8 mAbs and analyzed by flow cytometry after 30 days of culture. A: CD34−CD41+CD42− cells. B/C/D: CD34+CD41− cells. E/F/G: CD34+CD41+CD42− cells. A: 20 000 cells per lobe. B/E: 5000 cells per lobe. C/F: 1000 cells per lobe. D/G: 200 cells per lobe. (B) Proportion of negative lobes in the FTOC assays. Limiting dilution analysis of the results shown in Figure 6 are illustrated. They are derived from the analysis of 6 NOD-SCID lobes by cell concentration after 30 days of organotypic cultures. Cells recovered from the thymic lobes were analyzed by flow cytometry after labeling with anti-CD4 and CD8 antibodies. The concentration of cells ranged from 5000 to 200 cells with 6 thymic lobes by cell concentration.

Assessment of the T-cell potential of CD34+CD41−, CD34+CD41+CD42−, and CD34−CD41+CD42− cells from cord blood–cultured CD34+ cells.

(A) Cells extracted from each thymic lobe were labeled by R-PE anti–human CD4 and FITC anti–human CD8 mAbs and analyzed by flow cytometry after 30 days of culture. A: CD34−CD41+CD42− cells. B/C/D: CD34+CD41− cells. E/F/G: CD34+CD41+CD42− cells. A: 20 000 cells per lobe. B/E: 5000 cells per lobe. C/F: 1000 cells per lobe. D/G: 200 cells per lobe. (B) Proportion of negative lobes in the FTOC assays. Limiting dilution analysis of the results shown in Figure 6 are illustrated. They are derived from the analysis of 6 NOD-SCID lobes by cell concentration after 30 days of organotypic cultures. Cells recovered from the thymic lobes were analyzed by flow cytometry after labeling with anti-CD4 and CD8 antibodies. The concentration of cells ranged from 5000 to 200 cells with 6 thymic lobes by cell concentration.

Discussion

Hematopoietic stem cells are a heterogeneous population of cells that are able to reconstitute hematopoiesis. Numerous differentiation membrane antigens have been defined to better identify this cell population. Among them, CD34 is the most widely used antigen to characterize hematopoietic stem cells and progenitors. However, a fraction of stem cells that are considered extremely primitive are CD34−.41-44

Expression of CD41 in the hematopoietic system is controversial.21,22,24,27-30,45-47 It is well accepted that CD41 is detected during MK differentiation at a stage of a late MK progenitor.21,45,47 The presence of CD41 on multipotent progenitors and some non–MK-committed progenitors is still a matter of debate.22-24,48 This controversy might be due to the level of the CD41 antigen expressed on different cell types. A very high expression is present during late MK differentiation whereas a low amount of the protein might be present on other lineages as suggested by the work of Tropel et al.28

To obtain a high number of CD41+ cells, we have cultured purified CD34+ cells in the presence of a combination of SCF and PEG-rHuMGDF, a condition that induced both MK differentiation and expansion of hematopoietic primitive cells.31,49Previously, Basch et al48 have shown that TPO could induce CD41 expression on adult CD34+ cells after a 24-hour incubation. In some cell lines, it has been also shown that TPO increases synthesis of CD41.50 However, in normal cells, induction of the CD41 antigen on CD34+ cells is not a restricted effect of TPO because IL-3 or a combination of several cytokines had the same effects.37,48 Furthermore, there is evidence that cells with induced CD41 antigen have the same properties as freshly isolated cells.48 There remain several advantages to culturing CD34+ cells for studying CD41 expression: (1) the development of a large number of CD41+cells; (2) the possibility of analyzing rare CD41+phenotypes; and (3) minimizing contamination by platelet fragments stuck to CD34+ cells during cell purification.

When cultured cells were stained with antibodies against CD42 and CD41, a linear relationship between expression of these 2 antigens was observed. Only cells expressing low levels of CD41 were CD42−. Marked phenotypic differences were observed between cord blood and adult cells when expression of CD34 was studied in these CD41+ cells. Indeed, at day 6 of culture, the great majority of CD41+ cells are CD34+ in the adult culture, whereas they are CD34− in the neonate. This is not due to an acceleration of the differentiation in neonate cells, because the majority of CD34−CD41+ cells in the cord blood express a low level of CD41 and are negative for CD42 antigen, a cell phenotype that is nearly absent from cultured adult cells whatever the CD34+ cell origin (normal blood or marrow; data not shown). These results suggest that induction of CD41 and MK differentiation in the neonate proceeds through different pathways (Figure 1C).

These immunophenotypic differences correlate with different ontogenic biological properties of the CD41+ cells. In cord blood, the CD34+CD41+CD42− cells had a broad differentiation potential because they were able to give rise in vitro both to myeloid (granulocytic, erythroid, MK) and lymphoid (B-cell, T-cell, and NK-cell) lineages. This suggests that expression of CD41 is not related to a precise stage of differentiation, but that at different stages of differentiation, a fraction of progenitors expresses this antigen. The CD34+CD41+CD42− cell subset may also contain true hematopoietic stem cells because LTC-ICs and NOD-SCID reconstituting cells were present in this cell fraction. In contrast, CD34+CD41+CD42− cells from adults have a much more restricted potential. This cell subset was essentially enriched in MK and erythroid progenitors as previously reported.21,48,51 Nevertheless, very primitive progenitors such as LTC-ICs were detected in this fraction in adult samples. However, we were unable to demonstrate that in vitro, the adult CD34+CD41+CD42− cells had a lymphoid potential. Thus, it remains possible that CD41 is also expressed on some true hematopoietic stem cells in the adult but that its expression is quickly lost during lymphoid and myeloid differentiation and persists only in the erythroid and MK development. Such ontogenic differences in the expression of CD41 have not yet been reported. However, it must be emphasized that the non-MK potential of CD34+CD41+ cells has been essentially reported with fetal and neonate cells.23,24,26,52 53 In the mouse, we have recently demonstrated that all hematopoietic progenitors from yolk sac or derived from the in vitro differentiation of ES cells express CD41 (Mitjavila et al, unpublished data, 2000).

Surprisingly, these ontogenic changes may also involve the CD42 antigen. In neonate culture, expression of CD42 on CD34+CD41+ cells did not indicate MK commitment since erythroid and myeloid progenitors were detected in this cell fraction, as previously suggested.54

The present study further emphasizes the ontogenic changes occurring in the hematopoietic stem cell compartment and during MK differentiation. We observed 2 different pathways of MK differentiation with respect to surface markers in the adult and neonate samples (Figure 1C). This difference involves mainly CD34 expression. MK commitment occurs in a CD34− cell in the neonate and in a CD34+ cell in the adult. In addition, in neonate cells, all types of progenitors and also some pluripotent stem cells may have the CD34+CD41+ surface phenotype. These changes involving surface markers might be the reflection of more profound changes in MK development, such as polyploidization, which is defective in neonate cultures.55 These profound differences may explain the correction of the thrombocytopenia from the thrombocytopenia with absent radius (TAR) syndrome during the first year of life or adulthood.56 In this disease, we have recently shown the presence of a partial blockage in differentiation at the CD34−CD41+CD42−stage,37 a phenotype that corresponds to a neonate pathway of MK differentiation. The occurrence of a different pathway in the adult may thereafter permit the bypassing of this step. Identification of the molecular mechanisms that are responsible for these developmental changes will be essential for understanding the regulation of MK differentiation and for delineating the molecular basis of some congenital thrombocytopenia.

The authors thank P. Ardouin and A. Rouchez for breeding and care of the NOD-SCID mice, Aline Massé for technical assistance in handling and phenotyping the NOD-SCID mice and Drs Catherine Bocaccio and Françine Norol for providing leukapheresis samples.

Supported by grants from the Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, Association pour la Recherche sur le cancer (ND grant 9728), and the Institut Gustave Roussy.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Najet Debili, INSERM U 362, Institut Gustave Roussy, Villejuif 94805, Cedex, France; e-mail: verpre@igr.fr.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal