Abstract

The specific retention of intravenously administered hemopoietic cells within bone marrow is a complex multistep process. Despite recent insights, the molecular mechanics governing this process remain largely undefined. This study explored the influence of β2-integrins on the homing to bone marrow and repopulation kinetics of progenitor cells. Both antifunctional antibodies and genetically deficient cells were used. In addition, triple selectin-deficient mice were used as recipients of either deficient (selectin or β2) or normal cells in homing experiments. The homing patterns of either β2 null or selectin null cells into normal or selectin-deficient recipients were similar to those of normal cells given to normal recipients. Furthermore, spleen colony-forming units and the early bone marrow repopulating activity for the first 2 weeks after transplantation were not significantly different from those of control cells. These data are in contrast to the importance of β2-integrin and selectins in the adhesion/migration cascade of mature leukocytes. The special bone marrow flow hemodynamics may account for these differences. Although early deaths after transplantation can be seen in recipients deficient in CD18 and selectin, these are attributed to septic complications rather than homing defects. However, when β2- or selectin-null donor cells are treated with anti-α4 antibodies before their transplantation to normal or selectin-deficient recipients, a dramatic inhibition of homing (>90%) was found. The data suggest that the α4β1/vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 pathway alone is capable of providing effective capture of cells within the bone marrow, but if its function is compromised, the synergistic contribution of other pathways, that is, β2-integrins or selectins, is uncovered.

Introduction

Restriction of the developing hemopoietic cells to certain anatomic sites within the body, that is, the extravascular spaces of the bone marrow (BM), signifies a unique microenvironment capable of providing not only anchorage to hemopoietic cells, but of transmitting signals enabling their proliferation and differentiation. The relationship of hemopoietic cells with their microenvironment is a highly dynamic one allowing further expansion on demand and, depending on the stimuli, the movement of cells in and out of their microenvironment. The ability of intravenously administered cells to re-establish connections within the BM environment is a clinically exploited example of that flexibility. As the sinusoidal endothelial cells separate the extravascular space from the circulation, intravenously administered cells need first to tether to the sinusoidal endothelium, then to firmly anchor themselves within the extravascular space through reversible adhesion and transmigration steps. Although several insights regarding the molecular pathways that guide these processes have been obtained, our knowledge of this complex process remains incomplete. Early reports suggest that galactose- and mannose-specific lectins (present on hemopoietic cells) interacting with counterreceptors in the marrow environment is important for successful engraftment.1 Subsequent reports demonstrate that homing could be inhibited by several different molecular pathways using in vivo homing assays.2-6 For example, E- and P-endothelial selectins, which are absent in the E- and P-deficient mice, were found to be important for early stages of homing, providing tethering and rolling of the cells on the BM microvessels.4,5 Although a parallel contribution in homing by the very late activation antigen-4/vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VLA-4/VCAM-1) pathway was noted in these animals, which confirmed earlier studies on the function of the VLA-4/VCAM-1 pathway on homing,3 it was felt that this pathway could not operate in the absence of endothelial selectins. In addition to endothelial selectins, the presence of CXCR-4 on hemopoietic cells interacting with its ligand stromal cell-derived factor-1 (SDF-1) present on BM stroma and endothelial cells was deemed important in the homing and engraftment of human hemopoietic cells in xenogeneic hosts.6 Although the influence of SDF-1 on the maintenance of hemopoiesis within BM and its chemotactic effects on hemopoietic progenitor cells are undisputed,7-12 the impact of this pathway in the early stages of homing has been called into question, at least for murine cells.13-16 Follow-up studies by 2 groups in the homing of fetal liver CXCR4− cells showed no differences in the early period of hemopoietic reconstitution, although at later times abnormalities were seen.13,14 Other studies using antifunctional antibodies suggested involvement of the CD44/HA pathway in homing.16-18 However, CD44-deficient animals have no hemopoietic abnormalities, and CD44 null cells display no homing defect when given to normal or CD44 null recipients.19 Finally, the presence of β1-integrins was deemed essential in the migration and colonization of hemopoietic cells during development,20and β1−/− cells failed to contribute to hemopoiesis in chimeras.21 Whether the above studies suggest the contribution of different molecular pathways at discrete or overlapping stages of homing and engraftment, or whether they implicate functional redundancy of some pathways, or a convergence of several pathways to a common one, remains to be defined.

As previous homing studies with selectin-deficient recipients suggested,4,5 the homing of hemopoietic cells to BM could follow the paradigm of mature leukocytes migrating to inflammatory tissues.22 Because β2-integrins are instrumental for the firm adhesion and transmigration of neutrophils to inflammatory sites, we examined the influence of β2-integrin deficiency in homing. Their essential participation in neutrophil migration is illustrated in patients with leukocyte adhesion deficiency (LAD), in which the β chains are abnormal or deficient, resulting in a virtual absence of the CD11/CD18 complex on the surface of leukocytes.23 The availability of mice deficient in β2-integrins24,25 or in all selectins26 allows us to probe the molecular pathways involved in homing. In contrast to previously published data, we provide evidence that deficiencies in all selectins or in β2-integrins do not have a major impact on homing and short-term repopulation kinetics, even when β2-deficient cells are given to selectin-deficient recipients. Early deaths after transplantation are due to septic complications rather than defective homing. However, when an α4 functional blockade is superimposed in these mutations, homing is inhibited by over 90%, in contrast to about 40% inhibition seen in the anti-α4alone or documented in VCAM-1 hypomorphic animals. These results suggest that the role of β2-integrins or selectins in early stages of homing is synergistic with that of α4/β1-integrin and synergy is uncovered when α4 function is compromised.

Materials and methods

Mice

Heterozygous CD18+/− mice were kindly provided by Dr Arthur Beaudet (Baylor College, Houston, TX), and bred in our laboratory to generate homozygous CD18−/− mice. Characterization of these mice has been described previously.25 Genotyping for these mice was done at 3 weeks of age, as described previously,27 using tail DNA samples. Presence of the wild-type allele was detected by the primers 5′-CTGGACTGTTCTTCCTGG-GATC-3′ (forward) and 5′-CTACTTGGTGCATTCCTGGGAC-3′ (reverse), whereas presence of the targeted allele was detected by the primers 5′-CTGGACTGTTCTTCCTGGGATC-3′ (forward) and 5′-CTCGATGCGATGTTTCGGTTGGTG-3′ (reverse). Amplifications were performed on a Stratagene Robocycler (La Jolla, CA) for 35 cycles with an oligonucleotide annealing temperature of 54°C. Of the 123 animals tested in this manner, 16% were CD18−/−, a frequency consistent with previous reports. Genotypes of the knockout mice were routinely confirmed by fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis of peripheral blood samples with an anti-CD18 antibody, as described.27 CD18+/+ or CD18+/−littermates were used as controls in each experiment. EPL−/− mice were also kindly provided by Dr A. Beaudet and subsequently bred in our laboratory. EP−/− (B6; 129S-Seletm1Hyn, Selptm1Hyn), ICAM-1−/− (B6.129S7-Icam1tm1Bay), and hypomorphic CD18 (B6.129S7-Itgβ) mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). Hypomorphic VCAM-1–deficient mice with domain 4 deletion (D4D) were generated from heterozygous pairs provided by Dr M. Cybulsky (Toronto, ON).28 Progeny of D4D+/− mice were genotyped at 4 weeks of age by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of tail DNA samples. Presence of the wild-type allele was detected by the primers MV17C-FP1 (5′-ATACATTGGGTATGGTGTGATATG-3′) and MV17C-RP1 (5′-AACTTAAAATCCATGTTTTCATAGG-3′), whereas presence of the hypomorphic allele was detected by MV17C-RP1 and the primer PGK3′-FP3 (5′-CAAGCAAAACCAAATTAAGGG-3′). Approximately 5% of the generated mice were homozygotes for D4D. The degree of VCAM-1 expression was assessed in Northern blots from RNA purified from different tissues. Other control mice were B6.129 or BDF1s. All mice were housed in an accredited specific pathogen-free facility at our institution and mice of 6 to 8 weeks of age were used for experiments. Sentinel animals were checked regularly according to health monitoring standards. Early on, CD18−/− breeding mice developed skin infections and they were placed under intermittent antibiotic therapy (Baytril). CD18−/− mice with skin infections were not used for experiments. Irradiated mice, normal or deficient, used as recipients of deficient cells, were treated with antibiotics (Septra, [trimethoprin and sulfamethoxazole]) up to 30 days after transplantation. In our later experiments when donor bone marrow cells from CD18−/− or EPL−/− mice were used, the animals were treated for at least 1 week with antibiotics before harvesting their BM.

Antibodies

The following monoclonal rat antimouse antibodies were used in this study: anti–VLA-4 (clone PS/2 low endotoxin, azide-free was kindly provided by Dr Roy Lobb of Biogen, Cambridge, MA); anti–VCAM-1 antibody (clone M/K-2) was purchased from Southern Biotech (Birmingham, AL); anti–LFA-1 (CD11a, clone 17/4) and anti–P-selectin (RB40.34) were purchased from BD Pharmingen (San Diego, CA); anti–β2-integrin (CD18, clone 2E6) antibody was provided by Dr R. Winn (University of Washington, Seattle). All antibodies for in vivo treatments were low-endotoxin and azide-free. Conjugated antibodies were purchased from BD Pharmingen except for labeled anti–VCAM-1, which was purchased from Southern Biotech.

Homing assays

For homing studies, single-cell suspensions of BM donor cells prepared from the femurs/tibias of donor animals were washed, counted, and plated in quadruplicate in semisolid media to assess the number of clonogenic progenitors. A chosen inoculum of BM nucleated cells was injected via tail vein into lethally irradiated (1000-1200 R) recipients within 1 to 3 hours after irradiation. At various times after injection of donor cells (3 hours, 24 hours, 48 hours, 72 hours, 8 days, or 12 days), the animals were killed under anesthesia and circulating blood and selected tissues were obtained. Single-cell suspensions were prepared and counted to determine total cell numbers per organ, and an inoculum was cultured to determine the number of clonogenic donor cells present in each tissue. For calculating total BM, one femur was estimated to represent 6.7% of total BM, according to previous studies29 and values are expressed ± SEM. Cell suspensions from peripheral blood or other tissues were plated in duplicate or quadruplicate plates. In some experiments, nucleated donor cells were fluorescently labeled with carboxymethylfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE, Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR), and in these experiments fluorescent cells were assessed at various times after transplantation (3 hours, 24 hours), using a FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA) for analysis. A minimum of 1 × 105 nucleated cells was analyzed and calculations of total fluorescent cells recovered per organ were done, as stated above for culture colony-forming units (CFU-Cs).

Assay for spleen colony-forming units, day 12

Primary recipient mice were irradiated with 1000 to 1200 cGy from a cesium source (at the dose rate of >100 cGy/min) and then injected intravenously with washed nucleated BM cells by tail vein. Mice were killed 12 to 14 days later, their spleens placed in Bouin fixative, transferred to 10% neutral buffered formalin, and the number of macroscopically visible spleen colonies counted under a dissecting microscope.

CFU-C assays

The presence of clonogenic progenitors (CFU-Cs) in donor BM cells or cells retrieved from the BM, peripheral blood, or spleen of irradiated recipients was determined by plating appropriate aliquots of test cells in methylcellulose in Iscoves modified Dulbecco medium supplemented with the following: 10% murine interleukin-3 (IL-3), (Collaborative Biomedical Products, Bedford, MA), 100 ng/mL murine stem cell factor (SCF; Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ), 5 U/mL human erythropoietin (Amgen, Thousand Oaks, CA), 5% pokeweed mitogen spleen cell conditioned medium, 10−4 M 2-mercaptoethanol, 30% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Hyclone, Logan, UT), and 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Intergen, Purchase, NY). Donor BM cells used for transplantation were cultured at 1 × 105/mL, whereas recipient BM cells early after transplantation (3 hours, 24 hours) were cultured at 10 to 20 × 105/mL. After 7 to 9 days of incubation at 37°C, 5% C02, and high humidity, erythroid, granulocytic, or multilineage colonies were scored under a dissecting microscope on the basis of their characteristic appearance and color.

Immunofluorescent assays

Single-cell suspensions from BM cells were lysed with hypotonic buffer and labeled with CFSE (Molecular Probes) at a final concentration of 0.5 μM (50 mM stock solution was prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide). Cells were incubated at 37°C for 10 minutes and the uptake of CFSE was terminated by adding cold Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS) containing 5% FBS. The cells were subsequently washed twice in HBSS plus 5% FBS and resuspended in suitable concentrations for analysis or for injection. Recipient mice were injected with 20 × 106 cells to test the presence of CFSE-labeled donor cells lodged in BM or spleen, or present in peripheral blood of recipient animals. Cell suspensions from these tissues obtained 3 to 24 hours later were lysed to remove red cells, washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) plus 5% FBS, and analyzed for the presence of fluorescent cells on a Becton Dickinson FACSCalibur, equipped with an argon ion laser set to 488 nm. Between 20 000 and 100 000 ungated events were collected to obtain a measure of the proportion of cells positive for CFSE. The total number of CFSE+ cells in any given organ from which the sample was taken was calculated by multiplying the proportion of CFSE+cells by the total number of nucleated cells recovered per organ. At the same time, an aliquot of cells was cultured to enumerate CFU-Cs present within the BM cell suspension. In certain experiments the proportion of CD18+, or that of L-selectin-positive cells was determined in recipient animals. For this purpose, either whole blood or cell suspensions from the BM or cells retrieved from in vitro colonies were labeled with the fluorescent-conjugated antibody (1 μg/106 cells for 40 minutes at 4°C), washed, and subsequently analyzed on the FACSCalibur.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using Student ttest as found in Microsoft Excel software, using 2-tailed analysis assuming unequal sample variance.

Results

CD18−/− BM donor cells home normally into CD18+/+ littermate recipients

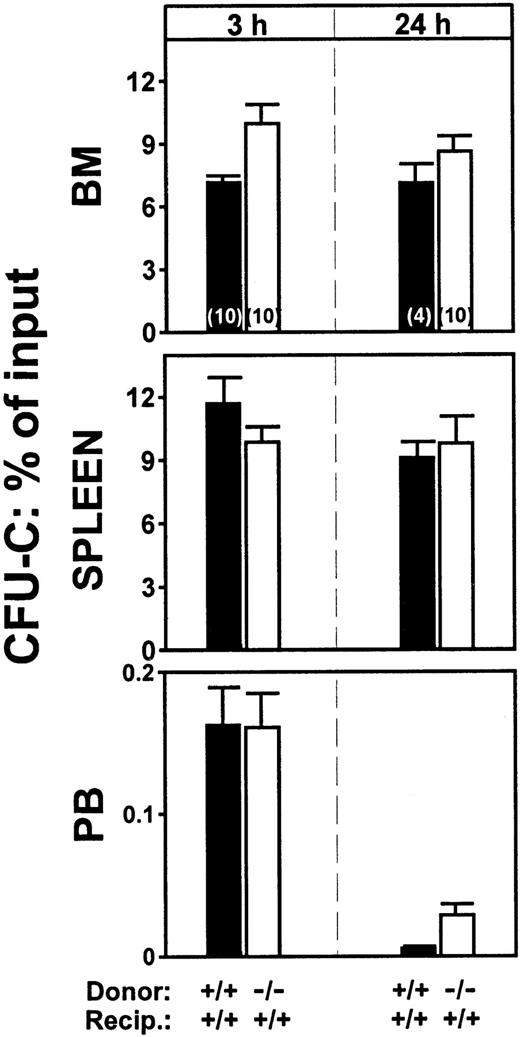

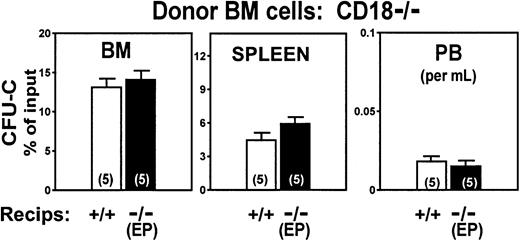

To study the role of β2-integrins in homing we initiated our experiments using cells treated with antifunctional antibodies. Cells treated with either anti-CD18 (clone 2E6) or anti-CD11a (LFA-1) (clone 17/4) antibodies did not differ from untreated control cells in terms of their ability to lodge to BM or spleen. Lodgment in the BM at 3 hours of anti-CD18–treated cells was at 120% ± 11.0% of control levels (P = .133), whereas lodgment of anti-CD11a–treated cells was at 77% ± 17.0% (P = .181). Inhibition of homing with antibodies used in vitro has not always been confirmed with gene-targeted mice (eg, studies with anti-CD44),19 so when CD18-deficient animals became available, we tested CD18-deficient cells in homing. In 2 separate experiments, no differences were found in the homing patterns at 3 hours between normal (CD18+/+) BM cells and CD18−/− cells, both given to normal (CD18+/+) littermate recipients (Figure 1). To explore whether the kinetics of homing were different between CD18−/− and CD18+/+ cells, we also determined homing values at 24 hours. Again, as seen in Figure 1, the patterns of normal and deficient cells were not statistically different. A small tendency for more CD18−/− CFU-Cs to be present in peripheral blood was seen, but the differences were not statistically significant (P ≥ .05). In addition to CD18 null mice we also tested intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1)–deficient mice as recipients. (ICAM-1 is the major endothelial ligand of leukocyte function-associated antigen [LFA-1].) Whether CD18+/+cells or CD18−/− cells were given in these animals, there were no homing defects. (BM seeding of double-positive cells to double-positive recipients: 10.09% ± 1.48%; to ICAM-1−/− recipients: 9.64% ± 0.87%. ICAM-1−/− recipients given CD18−/− cells: 17.5% ± 1.8%. There were 5 animals in each group.)

Homing patterns of CD18−/− or of double-positive BM cells transplanted into double-positive irradiated recipient animals.

The CFU-Cs lodged in BM or spleen or present in peripheral blood at 3 and 24 hours after injection are plotted as percent of the injected CFU-C inoculum. (P ≥ .05, for all combinations.) The total number of mice used for each value is indicated by a number within each column and the results of 2 independent experiments are pooled.

Homing patterns of CD18−/− or of double-positive BM cells transplanted into double-positive irradiated recipient animals.

The CFU-Cs lodged in BM or spleen or present in peripheral blood at 3 and 24 hours after injection are plotted as percent of the injected CFU-C inoculum. (P ≥ .05, for all combinations.) The total number of mice used for each value is indicated by a number within each column and the results of 2 independent experiments are pooled.

CD18−/− cells are radioprotective and have normal short-term repopulation activity

The BM proliferative activity of transplanted BM cells begins to rise between 24 and 48 hours from transplantation and continues thereafter.19 To test whether the homed CD18−/− cells proliferated to the same extent as control CD18+/+ cells, we measured the CFU-C content of BM at 8, 14, or 43 days after transplantation. As seen in Table1, reconstitution of hemopoiesis, using BM or peripheral blood values, was comparable to controls. To confirm that reconstitution did occur with CD18−/− cells, BM cells from these recipients, as well as colony-derived cells from cultured BM samples were labeled with anti-CD18. As seen in Figure2, the great majority of cells repopulating these recipients were CD18−/− negative. It is of note that in the earlier experiments (8-day data in Table 1) we encountered problems with sick animals or contaminated cultures. Because of this, all subsequent experiments were carried out with antibiotic-pretreated CD18−/− donors.

Short-term engraftment using normal (+/+) or CD18−/− donor cells

| Donor cells . | Donors . | Recipients . | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. BM cells × 103 injected . | No. CFU-Cs injected . | n . | Femur . | PB . | Spleen . | Femur CFU-C amplification* . | |||||

| Cells × 103 . | CFU-C . | WBC . | Hct . | CD18+ . | CFU-S . | GR-1+ . | |||||

| 8 days after transplantation† | |||||||||||

| +/+ | 1 500 | 3 940 | 5 | 1 970 ± 232 | 965 ± 271 | 49× | |||||

| −/−* | 1 500 | 3 520 | 5 | 1 930 ± 227 | 212 ± 113 | 12×1-153 | |||||

| +/+ | 6 760 | 10 440 | 5 | 9 890 ± 1 231 | 6 241 ± 1 108 | 120× | |||||

| −/− | 6 720 | 13 860 | 5 | 14 100 ± 928 | 9 236 ± 387 | 133× | |||||

| 14 days after transplantation‡ | |||||||||||

| +/+ | 500 | 1 240 | 5 | 8 863 ± 629 | 4 327 ± 2 100 | 5 077 ± 379 | 42.1% ± 1.4 | 6.5 | 698× | ||

| −/− | 500 | 1 395 | 6 | 9 230 ± 1 033 | 4 627 ± 1 155 | 7 544 ± 897 | 43.9% ± 0.5 | 6.8 | 663× | ||

| 43 days after transplantation | |||||||||||

| +/+ | 100 | 4 327 | 7 | 7 713 ± 822 | 54.2% ± 6 | 19.3% ± 5 | |||||

| −/− | 100 | 4 627 | 6 | 14 760 ± 2 520 | 19.1 ± 4 | 22.3% ± 5 | |||||

| Donor cells . | Donors . | Recipients . | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. BM cells × 103 injected . | No. CFU-Cs injected . | n . | Femur . | PB . | Spleen . | Femur CFU-C amplification* . | |||||

| Cells × 103 . | CFU-C . | WBC . | Hct . | CD18+ . | CFU-S . | GR-1+ . | |||||

| 8 days after transplantation† | |||||||||||

| +/+ | 1 500 | 3 940 | 5 | 1 970 ± 232 | 965 ± 271 | 49× | |||||

| −/−* | 1 500 | 3 520 | 5 | 1 930 ± 227 | 212 ± 113 | 12×1-153 | |||||

| +/+ | 6 760 | 10 440 | 5 | 9 890 ± 1 231 | 6 241 ± 1 108 | 120× | |||||

| −/− | 6 720 | 13 860 | 5 | 14 100 ± 928 | 9 236 ± 387 | 133× | |||||

| 14 days after transplantation‡ | |||||||||||

| +/+ | 500 | 1 240 | 5 | 8 863 ± 629 | 4 327 ± 2 100 | 5 077 ± 379 | 42.1% ± 1.4 | 6.5 | 698× | ||

| −/− | 500 | 1 395 | 6 | 9 230 ± 1 033 | 4 627 ± 1 155 | 7 544 ± 897 | 43.9% ± 0.5 | 6.8 | 663× | ||

| 43 days after transplantation | |||||||||||

| +/+ | 100 | 4 327 | 7 | 7 713 ± 822 | 54.2% ± 6 | 19.3% ± 5 | |||||

| −/− | 100 | 4 627 | 6 | 14 760 ± 2 520 | 19.1 ± 4 | 22.3% ± 5 | |||||

WBC indicates white blood cell; hct, hematocrit; and PB, peripheral blood.

Amplification factor was calculated by comparing the initial (at 3 hours) value of CFU-Cs per femur (based on homing of 0.5% of injected CFU-Cs) and the CFU-C/femur measured at 8 or 14 days later.

Two independent experiments are shown and none of the donor animals were pretreated with antibiotics. Each group had 5 mice.

Recipients of 5 × 105 BM cells were sacrificed at 14 days, whereas recipients of 1 × 105BM cells (from the same BM pool) were bled at 43 days after transplant to assess engraftment.

P = .0674.

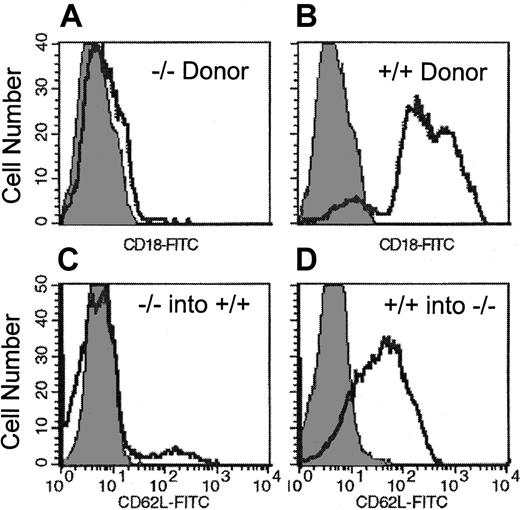

FACS histograms from recipients of CD18

null and selectin null donor cells. (A,B) FACS histogram of single-cell suspensions prepared from colony-derived cells (granulocyte-macrophage, erythroid burst-forming units, CFU-Mix) after culturing BM of recipients of CD18−/− cells (A) 2 weeks after transplantation. Note that in contrast to colonies derived from double-positive cells (B), all colonies from the CD18−/− double-positive recipients were contributed by CD18−/− cells. (C,D) Peripheral blood white blood cells at 30 days after transplantation in double-positive recipients of EPL−/− BM cells (C) and EPL−/− recipients of double-positive BM cells (D).

FACS histograms from recipients of CD18

null and selectin null donor cells. (A,B) FACS histogram of single-cell suspensions prepared from colony-derived cells (granulocyte-macrophage, erythroid burst-forming units, CFU-Mix) after culturing BM of recipients of CD18−/− cells (A) 2 weeks after transplantation. Note that in contrast to colonies derived from double-positive cells (B), all colonies from the CD18−/− double-positive recipients were contributed by CD18−/− cells. (C,D) Peripheral blood white blood cells at 30 days after transplantation in double-positive recipients of EPL−/− BM cells (C) and EPL−/− recipients of double-positive BM cells (D).

The above data appear to be in stark contrast to the prominent defects seen in mature leukocyte adhesion in mice with β2-integrin deficiency.30 One could argue that what was detected at 3 hours after intravenous infusion of β2-deficient cells in our assays is the cumulative presence of cells sequestered within the BM without transmigration, and of the ones that have already transmigrated to extravascular sites. However, if cells had failed to establish themselves within the BM, they would not have been expected to participate at 8, 14, or 43 days later in a repopulation activity that was similar to control (wild-type) donor cells (Table 1) even when limited numbers of donor cells (100 × 103) were used for transplantation. Recent data showing normal survival in animals that received transplants of β2-deficient fetal liver cells are consistent with our conclusions.31 It is of interest that chronic inflammatory state with leukocytosis and increased myelopoiesis prevails in these mice, and this pattern was also established in recipient animals in the present studies (Table 1, 43 days) and those of Horwitz and coworkers.31 Taken together, our data on normal homing of β2-deficient cells are also consistent with the absence of direct abnormalities in hemopoiesis detected in β2-deficient mice37 and suggest that the impact of β2-deficiency is manifested primarily on the function of mature cells and infectious complications resulting from it.

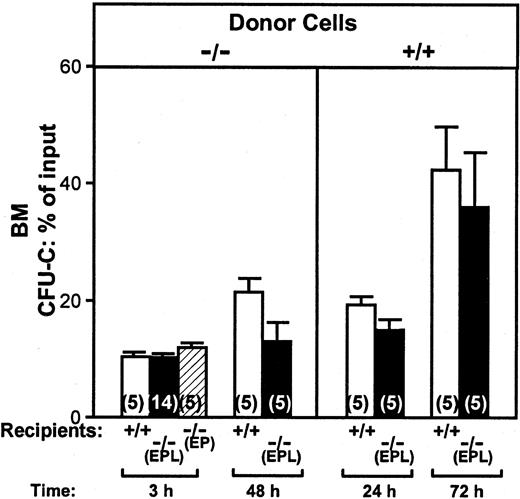

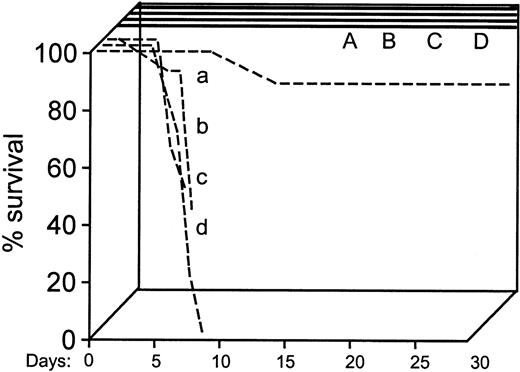

Homing in triple selectin-deficient recipients (EPL−/−)

It was previously reported that normal cells transplanted into EP double selectin-deficient animals failed to home normally.4,5 We were wondering whether homing of selectin-deficient cells transplanted into triple selectin-deficient recipient animals was further compromised. For this purpose, we transplanted BM cells from EPL−/− animals into irradiated EPL−/− recipients or double-positive recipient animals (B6.129) and compared results to recipient animals of either kind given double-positive cells. Data from all the above donor/recipient combinations are illustrated in Figure 3. BM homing at 3 hours measured as percent of clonogenic cells injected was similar when double-negative cells were used in double-positive, EPL−/−, or EP−/− recipients (Figure 3). Homing was also evaluated at 24 and 72 hours when double-positive cells were given to EPL−/− recipients or at 48 hours when double-negative cells (from EPL−/− mice) were given to EPL−/− recipients (Figure 3). Again, we failed to detect statistically significant differences in all combinations. In view of the divergence of our results to those published before,5we tested the survival of EPL−/− mice that received transplants of double-positive cells, as it was done previously. As seen in Figure 4, all EPL−/− animals that received transplants of 5 × 104 cells died, in contrast to controls, thus confirming the prior data.5 However, it was noted that animals that died in the prior study5 had 10 times more neutrophils in their blood compared to controls that survived. It was suspected that these animals may have succumbed to infectious complications rather than to graft failure. This speculation was reinforced by the fact that we were confronted with many contaminated cultures. For this reason, in all subsequent experiments, selectin-deficient animals used as recipients were treated with antibiotics for at least a week prior to their irradiation. When spleen colony-forming units (CFU-Ss) were evaluated in the spleens of recipient animals 2 weeks after transplantation and their BM proliferative activity was assessed, we found that the BM cellularity was higher in EPL−/− recipients, but the total contents of CFU-Cs in BM or CFU-Ss in spleen were similar to controls (Table2). To test whether the proliferative activity was derived from selectin-deficient cells, we labeled BM cells with anti–L-selectin antibodies and compared the percent positivity in recipients of double-positive or double-negative cells. As seen in Figure 2, virtually all repopulation activity in double-positive recipients of EPL−/− donor cells was by the double-negative donor cells up to 30 days after transplantation.

CFU-Cs in BM.

Figure shows the proportion of injected CFU-Cs that lodged in BM (total BM calculated as described in “Materials and methods”) when donor BM cells from EPL−/− or double-positive mice were given to either double-positive or EPL−/− or EP−/− irradiated recipients. Ten double-positive mice and 10 EPL−/− mice were given cells from EPL−/−donors and half were killed at 3 hours, the other half at 48 hours after infusion (left panel). At 3 hours an additional group of 9 recipient EPL−/− animals (5 + 9 = 14) and 5 EP−/− recipient animals were evaluated in separate experiments and are included in this figure. Another group of 20 animals, 10 double-positive recipients and 10 EPL−/−recipients were given double-positive cells from the same BM pool; half were killed at 24 hours and the rest at 72 hours (right panel). None of the differences between control (double-positive) cells or selectin-deficient (double-negative) cells given to double-positive or double-negative recipients were statistically significant (P ≥ .05).

CFU-Cs in BM.

Figure shows the proportion of injected CFU-Cs that lodged in BM (total BM calculated as described in “Materials and methods”) when donor BM cells from EPL−/− or double-positive mice were given to either double-positive or EPL−/− or EP−/− irradiated recipients. Ten double-positive mice and 10 EPL−/− mice were given cells from EPL−/−donors and half were killed at 3 hours, the other half at 48 hours after infusion (left panel). At 3 hours an additional group of 9 recipient EPL−/− animals (5 + 9 = 14) and 5 EP−/− recipient animals were evaluated in separate experiments and are included in this figure. Another group of 20 animals, 10 double-positive recipients and 10 EPL−/−recipients were given double-positive cells from the same BM pool; half were killed at 24 hours and the rest at 72 hours (right panel). None of the differences between control (double-positive) cells or selectin-deficient (double-negative) cells given to double-positive or double-negative recipients were statistically significant (P ≥ .05).

Survival data of double-positive or selectin double-negative recipients given double-positive or double-negative donor cells.

The first 4 groups of animals (dashed lines: a, b, c, d) received transplants of 5 × 104 BM cells/mouse. Of these, only the group of double-positive animals given double-positive donor cells (group a) survived at the 89% level. The remaining 3 groups of selectin double-negative recipients, 2 receiving either double-positive and one receiving double-negative donor cells died early. An additional 4 groups of animals (A, B, C, D; 5 mice each) received transplants later with 2 × 105 BM cells/mouse. These 4 groups survived beyond 30 days. The following combinations were used: A and a: double-positive cells to double-positive recipients; B and b: double-negative cells to double-positive recipients; C and c: double-positive cells to double-negative recipients; and D and d: double-negative cells to double-negative recipients.

Survival data of double-positive or selectin double-negative recipients given double-positive or double-negative donor cells.

The first 4 groups of animals (dashed lines: a, b, c, d) received transplants of 5 × 104 BM cells/mouse. Of these, only the group of double-positive animals given double-positive donor cells (group a) survived at the 89% level. The remaining 3 groups of selectin double-negative recipients, 2 receiving either double-positive and one receiving double-negative donor cells died early. An additional 4 groups of animals (A, B, C, D; 5 mice each) received transplants later with 2 × 105 BM cells/mouse. These 4 groups survived beyond 30 days. The following combinations were used: A and a: double-positive cells to double-positive recipients; B and b: double-negative cells to double-positive recipients; C and c: double-positive cells to double-negative recipients; and D and d: double-negative cells to double-negative recipients.

CFU-S and short-term repopulation of EPL−/−cells transplanted into EPL−/− recipients and comparisons with double-positive cells

| Donor . | Recipient . | Femur . | PB . | Spleen . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cells × 106 . | CFU-C . | WBC × 103 . | Percent 62L(−)* . | Percent Hct . | CFU-S . | ||

| 14 days after transplantation | |||||||

| +/+ | +/+ | 3.18 ± 0.44 | 772 ± 495 | 1.57 ± 0.21 | 31 ± 5 | 12.7 ± 0.33 | |

| −/− | +/+ | 3.04 ± 0.54 | 1643 ± 1567 | 1.45 ± 0.80 | 90 ± 4 | 16.7 ± 0.33 | |

| +/+ | −/− | 7.52 ± 0.07 | 1334 ± 467 | 1.36 ± 0.81 | 28 ± 6 | 18.5 ± 0.5 | |

| −/− | −/− | 4.99 ± 0.53 | 4122 ± 2151 | 2.59 ± 0.75 | 83 ± 10 | 15.3 ± 0.33 | |

| 30 days after transplantation† | |||||||

| +/+ | +/+ | 25.0 (pooled) | |||||

| −/− | +/+ | 7.23 ± 0.74 | 89.1 ± 2.0 | 52.1 (pooled) | |||

| +/+ | −/− | 14.41 ± 2.96 | 62.2 ± 7.0 | 44.5 (pooled) | |||

| −/− | −/− | 26.20 ± 4.82 | 96.7 (pooled) | 46.7 ± 1.85 | |||

| Donor . | Recipient . | Femur . | PB . | Spleen . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cells × 106 . | CFU-C . | WBC × 103 . | Percent 62L(−)* . | Percent Hct . | CFU-S . | ||

| 14 days after transplantation | |||||||

| +/+ | +/+ | 3.18 ± 0.44 | 772 ± 495 | 1.57 ± 0.21 | 31 ± 5 | 12.7 ± 0.33 | |

| −/− | +/+ | 3.04 ± 0.54 | 1643 ± 1567 | 1.45 ± 0.80 | 90 ± 4 | 16.7 ± 0.33 | |

| +/+ | −/− | 7.52 ± 0.07 | 1334 ± 467 | 1.36 ± 0.81 | 28 ± 6 | 18.5 ± 0.5 | |

| −/− | −/− | 4.99 ± 0.53 | 4122 ± 2151 | 2.59 ± 0.75 | 83 ± 10 | 15.3 ± 0.33 | |

| 30 days after transplantation† | |||||||

| +/+ | +/+ | 25.0 (pooled) | |||||

| −/− | +/+ | 7.23 ± 0.74 | 89.1 ± 2.0 | 52.1 (pooled) | |||

| +/+ | −/− | 14.41 ± 2.96 | 62.2 ± 7.0 | 44.5 (pooled) | |||

| −/− | −/− | 26.20 ± 4.82 | 96.7 (pooled) | 46.7 ± 1.85 | |||

For abbreviations, see Table 1.

Percent is among total GR-1(+) cells.

Mice analyzed 30 days after transplantation were part of the original group shown at 14 days after (ie, they were transplanted with 2 × 105 cells for each from the same BM pool. There were 5-6 mice in each group.). Note the tendency for leukocytosis in selectin-deficient recipients.

Taken together, our data with EP−/− or EPL−/− recipients of either double-positive or even double-negative cells are at variance with conclusions reached previously.4,5 According to the latter data, endothelial E- and P-selectins alone appear to provide essential contribution to homing and early deaths in EP−/−-deficient recipients were attributed to homing failure.5 Decreased rolling in calvarium BM microvessels was seen with these recipient mice and thought to be consistent with homing defects,4 although the consequences of the partially decreased rolling in the subsequent hemopoietic repopulation of these mice were not assessed.4,5 Our data do not argue against the fact that decreased rolling can be observed when EP−/− or triple selectin (EPL−/−) mice are used as recipients. They do suggest, however, that the impact of the decreased rolling in the subsequent repopulation observed is not significant. Whether the decreased rolling observed in the absence of selectins was exacerbated under the nonphysiologic experimental conditions used previously (ie, decreased hematocrit, low cell concentration, etc) is not clear. It is of note, however, that in the absence of any selectins the investigators noted that “significant” rolling did occur in these animals and it was virtually abrogated when α4/VCAM-1 function was inhibited.4 We have reproduced (Figure 4) the previous findings on the early demise of PE−/− recipient animals after transplantation.5 However, we attribute these deaths to infectious complications, rather than to failure of hemopoietic reconstitution. At the time of their deaths in the prior study,5 the mice had 10 times the normal number of neutrophils than controls, and approximately 30% of injected cells had lodged to the BM within 24 hours,5 an estimate that equals or exceeds normal BM seeding in many published studies.3 32-40 Our EPL−/− mice that received transplants of hemopoietic cells from donors treated with antibiotics survived and allowed us to assess their BM and blood hemopoietic reconstitution.

Homing patterns of CD18−/− cells into selectin-deficient recipients

Because CD18−/− cells showed indistinguishable patterns from normal cells in their homing at 3, 24, and 48 hours, we wondered whether the same could be true when selectin-deficient animals were used as recipients, or that the combination of β2- integrin–deficient cells given to selectin-deficient recipients could have a compounding homing defect. For this reason, CD18−/− BM cells were injected into irradiated EP−/− recipients. The results of these experiments are shown in Figure 5. No differences between CD18−/− cells given to normal recipients versus EP−/− recipients were uncovered.

Homing patterns of CD18−/− cells transplanted into irradiated double-positive recipients compared to those transplanted into PE−/− recipients assessed at 24 hours after injection.

Values are expressed as CFU-Cs recovered from each tissue as percent of injected CFU-C inoculum. Distribution in BM and peripheral blood do not show significant differences between the 2 types of recipients (P ≥ .05). Splenic uptake tends to be slightly higher in PE−/− recipient animals.

Homing patterns of CD18−/− cells transplanted into irradiated double-positive recipients compared to those transplanted into PE−/− recipients assessed at 24 hours after injection.

Values are expressed as CFU-Cs recovered from each tissue as percent of injected CFU-C inoculum. Distribution in BM and peripheral blood do not show significant differences between the 2 types of recipients (P ≥ .05). Splenic uptake tends to be slightly higher in PE−/− recipient animals.

The combination of β2-integrin and selectin deficiency would have been expected to lead to measurable defects, like the ones emphasized in the mature cells of doubly deficient animals (CD18 and E-selectin).30 However, EP−/− mice that received transplants of CD18−/− cells survived for several weeks after transplantation and normal reconstitution by CD18−/− cells was documented at 4 weeks and 6 months later.30 Although the homing patterns were not tested in this earlier study, and a high number of cells were transplanted, their data are both relevant and consistent with our conclusions. Despite their good repopulation ability, CD18/EP-deficient mice died later in the setting of widespread inflammatory findings in several tissues and in the presence of significant leukocytosis and myeloid hyperplasia, likely stimulated by granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) circulating in these mice. It is of interest that 2 of 6 recipients of CD18−/− cells died at about 90 days after transplantation, whereas 7 control animals all survived (data not shown).

When mature cells were examined in vitro, the compound CD18 and E-selectin deficiency provided the most severe defect on their rolling and adhesion in all assays tested.30 In view of these defects of mature cells, several possibilities can be considered to explain our data with normal homing of doubly deficient stem/progenitor cells. It has been previously stated that rolling, even in mature cells, should be affected by over 90% to influence adhesion.41 Thus, in the special hemodynamics of BM vasculature, either firm adhesion and transmigration phenomena are not measurably affected by decreased rolling, or the latter can be substituted by alternate adhesion pathways. The picture is reminiscent of the selectin-independent accumulation of neutrophils in lung or liver vasculature23 and our results with superimposed abrogation of α4/β1-integrin function suggest that the likely alternate pathway is α4β1 dependent.

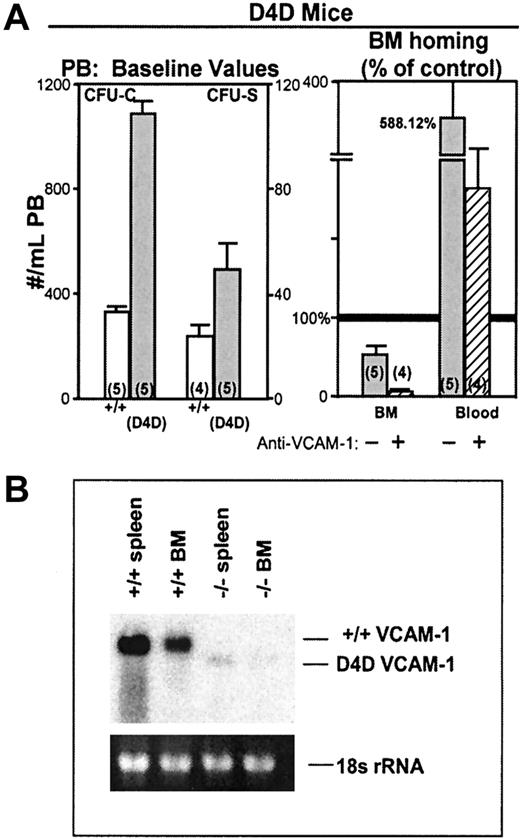

Observations in hypomorphic (D4D) VCAM-1 mice

We have previously shown that the specific retention of intravenously administered BM cells to the BM is mediated partly by the VLA-4/VCAM-1 pathway.3 This conclusion was based on the use of antifunctional antibodies, either against VLA-4 or VCAM-1. Subsequent studies have confirmed this observation4,17using the same or different approaches. Observations in gene-targeting mice have conclusively shown the importance of β1-integrins in colonization of hemopoietic sites in development and in postnatal life (fetal liver, BM, spleen). However, the specific partnership of α4 with β1 in this effect has not been confirmed,21 despite the demonstrated importance of α4 in the maintenance of normal hematopoiesis.42,43 To expand on these observations, we have used hypomorphic VCAM-1 mice with D4D and low expression (about 5%) of VCAM-1 (Figure6B). The α4-integrin binds to the homologous domains 1 and 4 of VCAM-1. Domain 1 appears to be primarily responsible for α4/VCAM-1–dependent primary capture of mature cells under flow, but both domain 1 and domain 4 can be used for adhesion under static conditions.44-46Therefore, D4D mice with low total expression of domain 1 containing protein provide an opportunity, albeit imperfect, to test the physiologic relevance of observations with antibodies. We have generated a small number of animals by breeding heterozygote pairs. We noted that in these animals, both the baseline presence of CFU-Cs and CFU-Ss in the blood is higher than the controls (Figure 6). Also, when these mice were used as recipients for homing experiments, reduction in homing was seen and was virtually abrogated when the animals were treated with MK2 antibody (which binds to domain 1 of VCAM-132) and were given anti-CD11a–treated cells (Figure6). These observations appear to be consistent with a role of VCAM-1 in the trafficking and homing of hemopoietic progenitors.

Hypomorphic VCAM-1 D4D mice.

(A) D4D mice have an increased number of circulating CFU-Cs and CFU-Ss compared to controls (P = <.05) and when used as recipients in homing assays, display decreased lodgment to BM compared to controls, and increased numbers of circulating CFU-Cs at 3 hours after injection (upper right panel). The homing is virtually abolished when these mice were injected with anti–VCAM-1 (MK/2; 2 mg/kg ×2, 12 hours apart) and given anti-CD11a–treated BM cells (striped column). (B) Constitutive expression of VCAM-1 in wild-type spleen and BM (total RNA 40 μg) is approximately 20-fold greater than that observed in the spleen and BM of D4D littermates.

Hypomorphic VCAM-1 D4D mice.

(A) D4D mice have an increased number of circulating CFU-Cs and CFU-Ss compared to controls (P = <.05) and when used as recipients in homing assays, display decreased lodgment to BM compared to controls, and increased numbers of circulating CFU-Cs at 3 hours after injection (upper right panel). The homing is virtually abolished when these mice were injected with anti–VCAM-1 (MK/2; 2 mg/kg ×2, 12 hours apart) and given anti-CD11a–treated BM cells (striped column). (B) Constitutive expression of VCAM-1 in wild-type spleen and BM (total RNA 40 μg) is approximately 20-fold greater than that observed in the spleen and BM of D4D littermates.

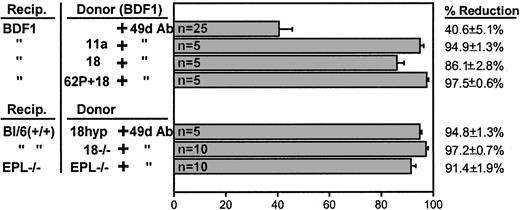

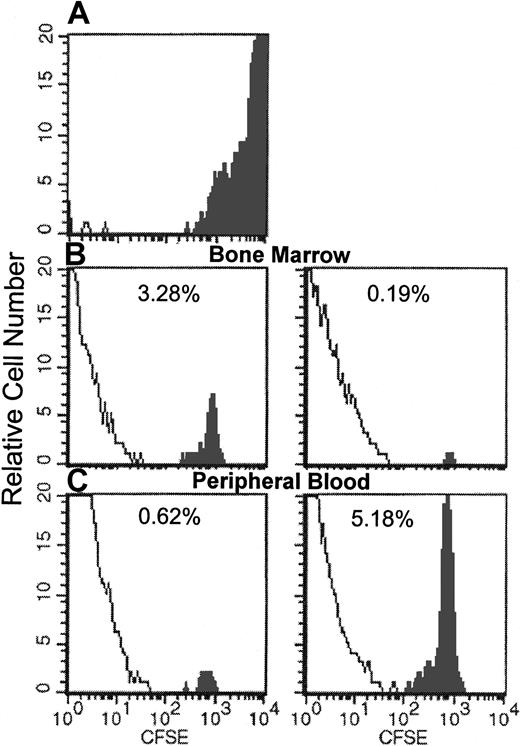

Combined antibody treatments or combination of deficiencies

Because the inhibition of homing by anti–VLA-4 is partial, we wanted to test to what extent the combination of anti-α4and anti–β2-integrin antibodies or the injection of anti-α4–treated cells into selectin-deficient animals could compound homing defects. It is of interest that single treatment with antibodies to β2-integrins (anti-CD18 or anti-CD11a, data presented herein) or antibodies against L-selectin4,17did not inhibit homing. However, addition of anti-α4 to other antibody treatments elicits an inhibition that was over 90% to that of untreated or single antibody-treated cells (Figure7). The same magnitude of inhibition was also seen with 3 antibodies (to 62L + 18 + 49d) or with a combination of anti–VCAM-1 treatment of recipients and anti–LFA-1 treatment of donor cells in D4D mice (Figure 6). We then treated CD18-deficient (CD18 hypomorphic or CD18−/−) or selectin-deficient cells with anti-α4 and assessed their homing, either in EPL−/− recipients as compared to double-positive recipients. As seen in Figure 7, the results of synergistic inhibition of homing obtained with combined antibody treatments were largely confirmed when cells from CD18-deficient animals were treated with anti-α4 antibody. For complementary evidence we ascertained the homing patterns of CD18−/− cells using both the CFSE- labeling approach used previously,19 32 a direct approach not dependent on proliferative potential, and our CFU-C approach within the same experiment. CFSE-stained CD18−/− BMs were injected (untreated or treated with anti-α4 antibody) into normal recipients, which were killed for analysis at 24 and 72 hours. Figure8 shows the recovery of CFSE-labeled cells analyzed by FACS from the BM and peripheral blood of recipients. The same samples were also assessed for CFU-C recovery by clonogenic assays. Homing to BM by the functional CFU-C assay at 24 hours was 6.0% ± 0.85%, well within the range previously observed (Figure 1) and with anti-α4–treated cells was 0.2% ± 0.096%. Respective values for CFSE-labeled cells were 16.04% ± 0.87% without anti-α4 and 0.98% ± 0.36% with anti-α4treatment. At 72 hours, BM CFU-C recovery was 22.7% ± 1.58% of injected and 0.37% ± 0.067% for anti-α4–treated cells. CFSE evaluation at 72 hours showed values well below the 24-hour ones for both sets of transplanted CFSE cells (data not shown). The above data and data with anti-α4–treated cells from EPL−/− animals given to EPL−/− recipients (Figure 7), collectively point to a dominant effect of α4with a synergistic contribution by β2-integrins and selectins in the initial capture of cells in BM whenever function of α4 is compromised.

Reduction in BM lodgment of donor cells treated with single or combination antibody treatments.

Percent reduction is calculated from values obtained with no antibody-treated cells. (This value was not significantly different from data using a single antibody other than anti-α4antibody.) When gene-deficient cells were used (CD18−/−or EPL−/−, bottom panel), the percent reduction is calculated from the value obtained with no antibody treatment. (Numbers within each column indicate numbers of mice used.)

Reduction in BM lodgment of donor cells treated with single or combination antibody treatments.

Percent reduction is calculated from values obtained with no antibody-treated cells. (This value was not significantly different from data using a single antibody other than anti-α4antibody.) When gene-deficient cells were used (CD18−/−or EPL−/−, bottom panel), the percent reduction is calculated from the value obtained with no antibody treatment. (Numbers within each column indicate numbers of mice used.)

Flow cytometric analysis of BM or peripheral blood cells of recipients of CFSE-labeled CD18

null cells 24 hours after their infusion. Solid profile: CFSE fluorescent cells. (A) Input donor CFSE-labeled BM cells. (B) Recovery of CFSE+/CD18 null cells in BM without (left) and with (right) anti-α4. (C) Circulating CFSE+/CD18 null cells in peripheral blood without (left) and with (right) anti-α4. (Pooled samples from femurs or the blood of 5 mice were used for FACS analysis.)

Flow cytometric analysis of BM or peripheral blood cells of recipients of CFSE-labeled CD18

null cells 24 hours after their infusion. Solid profile: CFSE fluorescent cells. (A) Input donor CFSE-labeled BM cells. (B) Recovery of CFSE+/CD18 null cells in BM without (left) and with (right) anti-α4. (C) Circulating CFSE+/CD18 null cells in peripheral blood without (left) and with (right) anti-α4. (Pooled samples from femurs or the blood of 5 mice were used for FACS analysis.)

Discussion

According to earlier descriptions of the adhesion cascade governing the migration of mature leukocytes to inflammatory sites, integrins did not participate in the first stages of rolling and tethering to the activated endothelium.22 Multiple recent examples have shown that α4/ligand interactions can contribute not only to firm adhesion and migration of mature leukocytes, but also to their tethering/rolling.47-54Thus, an additional function of α4, which has been overlooked previously, is projected in recent studies, showing α4-mediated tethering and/or rolling of leukocytes both in vitro and in vivo. Our previous data3 showing decreased homing of normal donor cells treated with anti-α4 did not directly address the particular stage of involvement (initial capture, firm adhesion/migration) of α4-integrin in progenitor cell homing. However, the normal homing patterns and normal short-term repopulation kinetics of β2-integrin or selectin-deficient recipients (see “Results”) uncovered herein provide an insight. An alternative pathway must be responsible for the capture and subsequent migration of these deficient cells. If they are treated with anti-α4 antibody, their homing is inhibited by more than 90%. Hence, our data assign an essential function of α4-integrin and its ligand in the initial capture of progenitor cells in homing, providing selectin-independent tethering/rolling, as observed previously,4 and at the same time uncover the redundant function of β2-integrins and selectins with β1-integrins in the setting of ablation of α4 function. The data are reminiscent of those uncovering the role of α4β1/VCAM-1 function only when the dominant function of LFA-1 in homing to peripheral lymph nodes was absent in LFA-1–deficient mice.55 Also, migration of neutrophils to the inflamed peritoneum of rabbits was CD18 independent and inhibition required both anti-CD18 and anti-α4 antibody treatment.

There are several reasons to suggest that the α4-integrin can provide tethering/rolling function for progenitor cells within the BM environment. Alpha-4 is more widely expressed in all progenitors and stem cells than either L-selectin or β2-integrin56-58; α4 in later cells is normally inactive unless several stimuli are applied, whereas in stem/progenitor cells several observations suggest that it is constitutively active and it may have higher affinity.59,60 Considering these attributes as well as the constitutive expression of VCAM-1 both on BM stromal cells and endothelial cells61,62 and the special hemodynamics of the BM tissue, it is likely that β2-integrins and selectins, in contrast to their effect on mature cells, are not primary or equal participants in homing, but could be called into action when the dominant α4β1/VCAM-1 pathway is compromised. It could be argued that neither the fluorescent assay of BM mononuclear cells nor the CFU-C assay used in selectin and β2 null studies reflect the homing patterns of long-term repopulating cells. However, when the latter were stringently purified,37,39 their calculated BM lodgment efficiency was very similar to the one calculated when labeled unpurified cells19,32 or CFU-Cs, or other surrogate in vitro assays were used.3,36 40 These results support the view that in vitro surrogate assays can be used to reflect the homing patterns of long-term repopulating cells and re-emphasize the long-held view that hemopoietic cells given intravenously are not preferentially attracted to BM.

All versatile functions of α4-integrin are likely accomplished through interaction with VCAM-1, its primary ligand. However, other ligands cannot be excluded. Several VCAM-1–independent functions of α4β1 have emerged in the literature.44,63,64 In these studies, as well as in studies using β1-deficient cells,21 novel (VCAM-1–independent) ligands for α4 function were entertained, but none as yet shown experimentally. Our limited data with hypomorphic D4D mice are consistent with the involvement of α4β1/VCAM-1 pathway in both the trafficking and homing of hemopoietic progenitors (Figure 6). Constitutive expression of VCAM-1 in endothelial cells and stromal cells within the BM, as well as data using anti–VCAM-1 antibodies in vitro or in vivo, support this view. Furthermore, recent data using VCAM-1 conditional ablation in mice65,66 have uncovered an essential but previously unappreciated contribution of VCAM-1 in the orderly trafficking of B cells between BM and periphery. However, in contrast to α4-integrins affecting both B- and T-cell development postnatally,30,31 B and T cells develop in the absence of VCAM-1.65,66 Therefore, other α4ligands67,68 may have additional functions during lymphopoiesis. It is of note that both our conclusions with D4D mice and those using VCAM-1 conditionally ablated mice65,66diverge from conclusions reached previously using a small number of D4D animals.28 We speculate that problems with “leakiness” in total VCAM-1 expression in D4D mice or reliance only on in vitro data may account for the differences.

Of interest, the VCAM-1–dependent retention of B cells in BM65,66 resembles data with CXCR4/SDF-1 mice69and CD24-deficient mice.70 It is tempting to speculate that VCAM-1 may serve as a common mechanistic pathway mediating the action of other pathways in homing, such as SDF-1/CXCR4.69,71,72 Recent data73 showing that, in the absence of selectins, immobilized SDF-1 promoted VLA-4–mediated tethering and firm adhesion of human CD34+cells to VCAM-1 under shear flow in vitro, provide an additional scenario reinforcing views presented herein about the mechanics of homing.

We are indebted to Drs A. Beaudet and M. Cybulsky for the generous supply of their mice, and Drs Roy Lobb and R. Winn for the supply of antibodies. We thank Domino Hawks for her expert secretarial assistance.

Supported by National Institutes of Health grants HL58734 and AI32177.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Thalia Papayannopoulou, Division of Hematology, University of Washington, Box 357710, Seattle, WA 98195-7710; e-mail: thalp@u.washington.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal