Abstract

Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia/thrombosis (HIT/HITT) is a severe, life-threatening complication that occurs in 1% to 3% of patients exposed to heparin. Interactions between heparin, human platelet factor 4 (hPF4), antibodies to the hPF4/heparin complex, and the platelet Fc receptor (FcR) for immunoglobulin G, FcγRIIA, are the proposed primary determinants of the disease on the basis of in vitro studies. The goal of this study was to create a mouse model that recapitulates the disease process in humans in order to understand the factors that predispose some patients to develop thrombocytopenia and thrombosis and to investigate new therapeutic approaches. Mice that express both human platelet FcγRIIA and hPF4 were generated. The FcγRIIA/hPF4 mice and controls, transgenic for either FcγRIIA or hPF4, were injected with KKO, a mouse monoclonal antibody specific for hPF4/heparin complexes, and then received heparin (20 U/d). Nadir platelet counts for KKO/heparin–treated FcγRIIA/hPF4 mice were 80% below baseline values, significantly different (P < .001) from similarly treated controls. FcγRIIA/hPF4 mice injected with KKO and 50 U/d heparin developed shock and showed fibrin-rich thrombi in multiple organs, including thrombosis in the pulmonary vasculature. This is the first mouse model of HIT to recapitulate the salient features of the human disease and demonstrates that FcγRIIA and hPF4 are both necessary and sufficient to replicate HIT/HITT in an animal model. This model should facilitate the identification of factors that modulate disease expression and the testing of novel therapeutic interventions.

Introduction

Heparin is one of the most widely used anticoagulants during invasive vascular procedures and to treat thromboembolic diseases. Among patients who receive therapeutic courses of heparin, 1% to 3% will develop an antibody-mediated thrombocytopenia,1-3 and 30% to 70% of these patients will develop potentially life-threatening thrombosis. There is abundant evidence that more than 95% of patients with heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) alone and those with thrombocytopenia and thrombosis (HITT) develop antibodies that recognize complexes between platelet factor 4 (PF4) and heparin.4-7 PF4, a major component of platelet α-granules, is released when platelets are activated.8,9 It is currently believed that complexes between PF4 and heparin form on the surface of activated platelets, where they are positioned to be recognized by anti-PF4/heparin antibodies.10-12 Antibodies to the PF4/heparin complex have been shown to activate human platelets in vitro via the platelet Fc receptor (FcR) for immunoglobuin (Ig)–G, FcγRIIA.13-16 The binding of HIT antibodies to activated platelets probably promotes microparticle release as well as platelet-platelet and platelet–vessel wall interactions, predisposing to thrombosis.15 17

However, the mechanism by which HIT antibodies activate platelets and promote thrombosis is uncertain. It has been proposed that HIT antibodies bind to cell-surface–associated PF4/heparin complexes via the Fab end of the molecule, providing an opportunity to transduce platelet-activating signals through the interaction between the Fc portion of the bound IgG and FcγRIIA.12,13 FcγRIIA, the sole Fcγ receptor expressed on platelets,18 has been shown to transduce signals without the requirement for another transmembrane partner.19 A monoclonal antibody to FcγRIIA blocks platelet aggregation and secretion induced by HIT antibodies.12,13 Although increased FcγRIIA expression on the platelets of HIT patients has been reported,20there is as yet no definitive proof that activation through FcγRIIA occurs in vivo in HIT or participates in the development of thrombosis. It is also unproved that anti-PF4/heparin antibodies, though prevalent,21-23 actually cause thrombocytopenia or thrombosis in patients with HIT/HITT. There is a need for more careful delineation of these processes in vivo.

We have previously shown that mice immunized with HIT antibodies isolated from human sera ultimately developed mouse antibodies to the human anti-PF4/heparin antibodies and developed thrombocytopenia after injection of heparin.24,25 However, the severity of the resultant thrombocytopenia was only modest; thrombosis was not detected; and the contribution of other autoantibodies that the mice developed during the course of epitope spread was unclear.25

A mouse model of HIT/HITT that recapitulates the disease process in humans would help clarify the factors that predispose some patients to develop thrombocytopenia or thrombosis and to investigate novel therapeutic approaches. Previously described mouse models have 2 intrinsic limitations that restrict their applicability in an examination of the role of the FcγRIIA receptor in the pathogenesis of HIT/HITT. First, human HIT antibodies rarely recognize complexes of heparin and mouse PF4.26 Second, mouse platelets do not express an analog of the human FcγRIIA receptor that is capable of signal transduction upon occupation and cross-linking.27 28

To address both limitations and to simulate the expression of these 2 critical components in HIT/HITT, we employed a transgenic approach to create a mouse model of this disorder and its treatment. We previously generated and characterized transgenic mice in which human FcγRIIA is expressed on mouse platelets and macrophages at levels equivalent to those in human cells.29 Using this model, we have demonstrated a critical role for FcγRIIA expression in antibody-induced thrombocytopenia in vivo using a nonactivating antibody. More recently, we have shown, for the first time, that an activating antiplatelet antibody induces not only thrombocytopenia, but also thrombosis and shock, effects that are exacerbated by reduced splenic clearance.30 We have also created transgenic mice that express human PF4 (hPF4) in their platelets.31 By crossing the lines that express human FcγRIIA and hPF4, we have developed a mouse model in which the contribution of platelet activation by antibodies to hPF4/heparin complexes through FcγRIIA to the pathogenesis of thrombocytopenia and thrombosis in HITT can be evaluated.

Materials and methods

Generation of double-transgenic FcγRIIA/hPF4 mice

We have previously reported the generation and characterization of FcγRIIA transgenic mice and antiplatelet antibody–induced thrombocytopenia and thrombosis.29,30 These mice express the R131 isoform of human FcγRIIA, demonstrated to bind mouse IgG1- and mouse IgG2-containing immune complexes.32

Mice transgenic for hPF4 were generated by standard methods by means of a 10-kilobase Eco RI genomic fragment containing the hPF4 gene.31 Transgene expression was tissue specific, because hPF4 RNA expression was found, as expected, in spleen, bone marrow, and platelets, but not in other tissues (liver, brain, lung, heart, kidney, adrenal, and muscle).

Platelets from mice with 10 copies of the transgene and highest relative RNA message level were examined for expression of hPF4 protein by immunoblotting. Whole blood, collected by cardiac puncture into 3.8% sodium citrate (1:10 vol/vol) to prevent coagulation, from 5 wild-type mice or 5 hPF4 transgenic mice was spun at 100g in a Sorvall RT6000B (Newtown, CT) to isolate platelet-rich plasma. Platelets were then pelleted at 1900g, resuspended in 25 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 140 mM NaCl, pH 7.25, containing phenylmethyl sulfonyl fluoride (0.1 mg/mL). The platelet pellets were lysed by freeze-thawing, and the protein concentration of each lysate was determined by the Pierce BCA Protein Assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Aliquots of platelet lysates, each 20 μg total protein, from wild-type mice, transgenic hPF4 mice, and a human control were electrophoresed on a 10% Nu-PAGE (Novex, San Diego, CA) gel under reducing conditions. As a known control, 100 ng recombinant hPF47 was added to a wild-type sample and run separately. Separated proteins were transferred to a polyvinylidine difluoride (PVDF) membrane (Novex) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The PVDF membrane was blocked with 5% nonfat milk–phosphate buffered saline (PBS)–0.1% Tween, washed with PBS–0.1% Tween, and incubated with a 1:10 000 dilution of RTO, a mouse anti-hPF4 monoclonal antibody.33 The membrane was washed in PBS–0.1% Tween, incubated with a rabbit anti–mouse immunoglobulin secondary antibody (NA 931) (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ) for 1 hour at room temperature, and washed again in PBS–0.1% Tween. The protein bands were detected by ECL + Plus (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech), and quantified with a Storm imager (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA).

FcγRIIA transgenic mice were crossed with hPF4 transgenic mice, and the resulting progeny were screened for the presence of both transgenes by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Individual transgenic lines were maintained on a B6SJL background. The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of the A. I. duPont Hospital for Children and Thomas Jefferson University approved all studies.

Monoclonal antibodies

KKO is a mouse monoclonal IgG2bκ that specifically binds hPF4/heparin complexes at similar molar ratios demonstrated for HIT antibodies.30 KKO activates platelets via the FcγRIIA receptor in the presence of heparin as demonstrated by14C-serotonin release.33 RTO, a mouse monoclonal antibody, has antigenic specificity for hPF4 but not the PF4/heparin complex.33 Neither antibody reacts with mouse PF4, whether or not the protein is complexed with heparin.

Experimental protocol

The experimental groups included mice transgenic for both FcγRIIA and hPF4, for FcγRIIA only, and for hPF4 only. Both male and female mice, 2 to 6 months old and weighing an average of 33 g, were used in this study. On day 0, each mouse was injected intraperitoneally (IP) with 400 μg KKO or isotype control antibody.33 All mice then received daily subcutaneous injections of unfractionated porcine heparin (Elkins-Sinn, Cherry Hill, NJ) for 5 days. We chose a daily heparin dose of 20 U per mouse, which for the mice used is 600 U/kg/d, well within the human therapeutic dose range. Platelet counts (number per microliter) for all mice were measured 3 days prior to antibody injection, for baseline values, and on days 1, 2, 3, 4, and 7 following antibody injection as described.29

Since the mice examined express endogenous mouse PF4, which does not interact with KKO by itself or when complexed with heparin,33 we hypothesized that a higher heparin dose may be required to simulate conditions in humans. Therefore, FcγRIIA/hPF4 (No. = 4) and hPF4 only (No. = 3) mice were injected with the KKO or isotype control (400 μg per mouse, IP) and a higher dose of heparin (50 U per mouse per day).

Histopathology

Representative FcγRIIA/hPF4 mice injected with KKO (or isotype) followed by heparin (50 U/d) or saline were examined histopathologically. One mouse injected with both KKO and heparin died just prior to collection of tissue specimens; others were euthanized by CO2 inhalation. The brain, lungs, heart, liver, kidneys, and spleen were removed from each mouse and fixed in 10% formalin, processed through paraffin, and sectioned at approximately 5 μm. Sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin were evaluated microscopically by a veterinary pathologist blinded to the experimental protocol (Pathology Associates International, Frederick, MD). Additionally, the formalin-fixed sections were examined for the presence of hPF4 by staining with RTO (20 μg/mL) or an isotype control, both of which had been directly biotinylated. Sections were sequentially blocked with H2O2 in CH3OH (to inhibit endogenous peroxidase activity) and 10% mouse serum prior to staining with the biotinylated antibodies. Bound antibody was detected by incubating biotinylated horseradish peroxidase plus avidin followed by staining with diaminobenzidine. Sections were then lightly counterstained with hematoxylin and examined by light microscopy.

Statistical analysis

Differences between nadir platelet counts among mice of differing genotypes were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Values of P < .05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Generation and analysis of the FcγRIIA/hPF4 mouse model

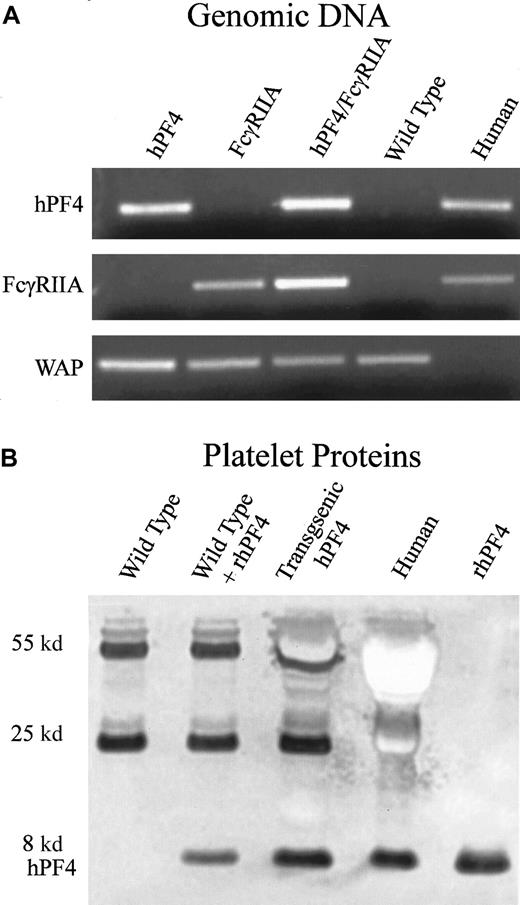

Platelets obtained from transgenic hPF4 mice were analyzed for expression of hPF4 protein by immunoblotting with RTO, an antibody that recognizes human but not mouse PF4,33 as described in “Materials and methods.” Expression levels of hPF4 protein were comparable to the hPF4 content of human platelets (Figure1B).

Generation and characterization of transgenic FcγRIIA/hPF4 mice.

(A) PCR detection of transgenic mice by means of human-specific primers for hPF4 and FcγRIIA, and control mouse-specific primers for whey acidic protein (WAP). Lane 1, transgenic hPF4; lane 2, transgenic FcγRIIA; lane 3, double-transgenic progeny; lane 4, wild-type mice; lane 5, human genomic DNA. (B) Western blot of platelet proteins separated on a 10% Nu-PAGE gel, transferred to PVDF, and immunostained with RTO, a human PF4-specific mouse monoclonal antibody, shows an intensely stained band at approximately 8 kd, consistent with the molecular weight of PF4. Lane 1, wild-type mice; lane 2, wild-type plus added recombinant hPF4; lane 3, transgenic hPF4 mice; lane 4, human platelet proteins; lane 5, recombinant hPF4. The lane with wild-type mouse platelet proteins does not show staining in the 8-kd region. The other stained bands at molecular weights of 55 and 25 kd represent immunostaining of immunoglobin heavy and light chains that react with the anti–mouse immunoglobulin secondary antibody.

Generation and characterization of transgenic FcγRIIA/hPF4 mice.

(A) PCR detection of transgenic mice by means of human-specific primers for hPF4 and FcγRIIA, and control mouse-specific primers for whey acidic protein (WAP). Lane 1, transgenic hPF4; lane 2, transgenic FcγRIIA; lane 3, double-transgenic progeny; lane 4, wild-type mice; lane 5, human genomic DNA. (B) Western blot of platelet proteins separated on a 10% Nu-PAGE gel, transferred to PVDF, and immunostained with RTO, a human PF4-specific mouse monoclonal antibody, shows an intensely stained band at approximately 8 kd, consistent with the molecular weight of PF4. Lane 1, wild-type mice; lane 2, wild-type plus added recombinant hPF4; lane 3, transgenic hPF4 mice; lane 4, human platelet proteins; lane 5, recombinant hPF4. The lane with wild-type mouse platelet proteins does not show staining in the 8-kd region. The other stained bands at molecular weights of 55 and 25 kd represent immunostaining of immunoglobin heavy and light chains that react with the anti–mouse immunoglobulin secondary antibody.

Mice lack an endogenous platelet Fcγ receptor; therefore, the transgenic hPF4 mice were mated with transgenic mice expressing the human FcγRIIA to create the double-transgenic mice used to establish the HIT model. We have previously shown that hemizygous FcγRIIA mice have an Fcγ receptor density within the normal range of that found on human platelets and that the receptor binds mouse IgG ligands to activate mouse platelets.29 Mice lack an endogenous platelet Fcγ receptor. The F1 progeny hemizygous for both hPF4 and FcγRIIA (Figure 1A) were chosen to determine the effects of a monoclonal HIT-like antibody, KKO, and heparin.

Studies of antibody-induced thrombocytopenia and thrombosis

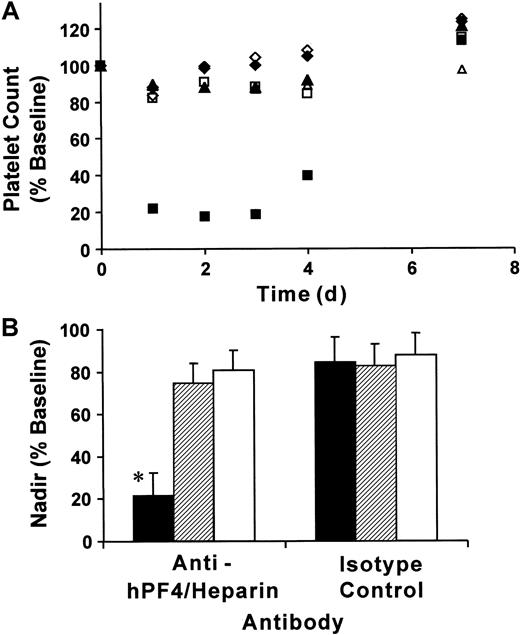

To determine whether our double-transgenic mice modeled the thrombocytopenia observed in patients with HIT, we injected mice with KKO or isotype control monoclonal antibodies (400 μg per mouse, IP) followed by subcutaneous injections of heparin (20 U per mouse, equivalent to a human dose of 600 U/kg/d) for 5 days. As controls, we used littermates that were transgenic for FcγRIIA only or mice transgenic for hPF4 only. Platelet counts were determined prior to antibody injection, then daily following the start of heparin exposure. Platelet counts for FcγRIIA/hPF4 transgenic mice injected with KKO fell by approximately 80% by day 1, remained low on days 2 and 3, and began to rebound by day 4 (Figure 2A). Similarly treated groups of control mice, FcγRIIA only and hPF4 only, experienced drops in platelet counts of approximately 15% over the same time course. Injection of isotype control antibody and heparin also resulted in a 15% drop in platelet counts in each of the transgenic lines examined (Figure 2A). By day 7, all mice had platelet counts that were approximately 20% higher than baseline, a rebound thrombocytosis described in other studies of antibody-mediated thrombocytopenia.29 34

Immune thrombocytopenia following injection of anti-hPF4/heparin antibody and heparin.

(A) Mice transgenic for both FcγRIIA and hPF4 (▪, ■), transgenic for FcγRIIA only (♦, ⋄), and transgenic for hPF4 only (▴, ▵) were injected with 400 μg antibody IP followed by daily subcutaneous injections of heparin (20 U per mouse). Platelet counts, obtained at the time points indicated, are shown as a percentage of baseline values for transgenic mice treated with anti-hPF4/heparin (▪, ♦, ▴) or isotype control (■, ⋄, ▵) antibodies. Only the transgenic FcγRIIA/hPF4 mice injected with anti-hPF4/heparin antibody and heparin developed severe thrombocytopenia, as shown by an 80% drop in the platelet count. (B) Nadir platelet counts following antibody and heparin injections. The graph shows the mean nadir platelet counts as the percentage ± one SD of baseline for mice transgenic for both FcγRIIA and hPF4 (▪), transgenic for FcγRIIA only (▨), and transgenic for hPF4 only (■) treated with anti-hPF4/heparin or isotype control antibodies prior to heparin injections. The nadir for the double-transgenic mice treated with anti-hPF4/heparin antibody and heparin was 78.6% ± 10.8% below baseline platelet counts, which was significantly different from the control subjects (*P < .001, ANOVA). The nadir counts for the transgenic lines treated with isotype control antibody were not significantly different.

Immune thrombocytopenia following injection of anti-hPF4/heparin antibody and heparin.

(A) Mice transgenic for both FcγRIIA and hPF4 (▪, ■), transgenic for FcγRIIA only (♦, ⋄), and transgenic for hPF4 only (▴, ▵) were injected with 400 μg antibody IP followed by daily subcutaneous injections of heparin (20 U per mouse). Platelet counts, obtained at the time points indicated, are shown as a percentage of baseline values for transgenic mice treated with anti-hPF4/heparin (▪, ♦, ▴) or isotype control (■, ⋄, ▵) antibodies. Only the transgenic FcγRIIA/hPF4 mice injected with anti-hPF4/heparin antibody and heparin developed severe thrombocytopenia, as shown by an 80% drop in the platelet count. (B) Nadir platelet counts following antibody and heparin injections. The graph shows the mean nadir platelet counts as the percentage ± one SD of baseline for mice transgenic for both FcγRIIA and hPF4 (▪), transgenic for FcγRIIA only (▨), and transgenic for hPF4 only (■) treated with anti-hPF4/heparin or isotype control antibodies prior to heparin injections. The nadir for the double-transgenic mice treated with anti-hPF4/heparin antibody and heparin was 78.6% ± 10.8% below baseline platelet counts, which was significantly different from the control subjects (*P < .001, ANOVA). The nadir counts for the transgenic lines treated with isotype control antibody were not significantly different.

The nadir, presented as a percentage of baseline platelet counts, from mice of each genotype treated with heparin and KKO or isotype control is shown in Figure 2B. Platelet counts for double-transgenic mice exposed to both KKO and heparin reached nadir values on days 1 to 3 after initiation of heparin exposure. The FcγRIIA/hPF4 transgenic mice (No. = 9) became severely thrombocytopenic, reaching nadir counts of 0.21 ± 0.13 × 106, which represented a drop of 78.6% ± 10.8% from the baseline platelet count. In contrast, exposure of mice transgenic for FcγRIIA only (No. = 6) or hPF4 only (No. = 6) to KKO and heparin resulted in nadir counts of 0.73 ± 0.19 × 106/μL and 0.76 ± 0.08 × 106/μL, a much smaller fall from their respective baseline values. All of the transgenic lines examined (No. = 4 for each group) had similar nadir counts (12% to 18% below baseline platelet counts) when injected with isotype control antibody and heparin. The differences between the nadir counts in double-transgenic mice injected with KKO and heparin and similarly treated mice transgenic for FcγRIIA only or for hPF4 only (No. = 4 for each group) were statistically significant (P < .001, ANOVA). There was no statistically significant difference in nadir counts among the mouse genotypes injected with isotype control antibody and heparin (P = .95, ANOVA).

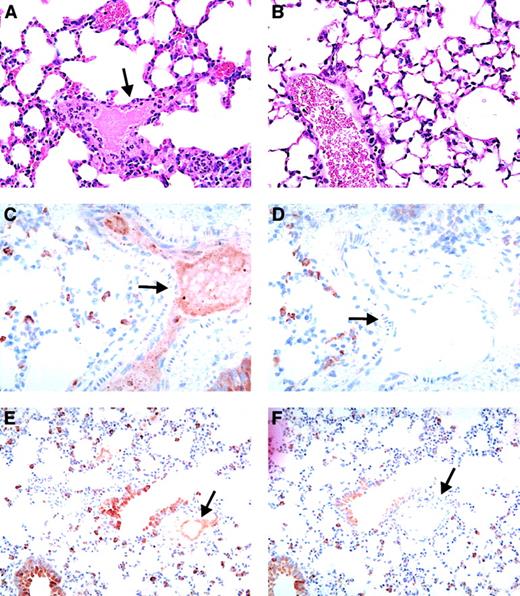

In double-transgenic mice, circulating heparin may bind to both endogenous mouse PF4 and hPF4, which may affect the amount of hPF4/heparin complex that is available to interact with the KKO antibody. Since the mouse PF4/heparin complex does not interact with KKO,33 we hypothesized that a higher heparin dose may be required to simulate conditions in humans. Therefore, we injected a separate cohort of FcγRIIA/hPF4 with KKO or isotype control (400 μg per mouse, IP) and a higher dose of heparin (50 U per mouse per d; No. = 4) or saline as a control (No. = 1). To control for the possibility that the higher heparin dose alone could cause shock and thrombosis, we injected hPF4-only mice with KKO (400 μg per mouse, IP; No. = 3) or isotype antibody (400 μg per mouse, IP; No. = 3) and heparin (50 U per mouse per day). FcγRIIA/hPF4 mice injected with KKO showed a dramatic shock phenotype following the fourth daily injection of the higher heparin dose as evidenced by greatly reduced physical activity, rapid shallow breathing, a hunched posture, and marked tactile hypothermia. Platelet counts revealed severe thrombocytopenia, with a drop in platelet count of 83% by day 4. One mouse died just prior to collection of tissues for histology; 1 was euthanized; and 2 recovered. None of the control mice (FcγRIIA/hPF4 injected with KKO and saline; FcγRIIA/hPF4 injected with isotype antibody and heparin; and hPF4 only injected with KKO or isotype and heparin) became thrombocytopenic or showed any signs of shock or other physical distress. Histologic analysis of FcγRIIA/hPF4 mice demonstrating the shock phenotype revealed fibrin thrombi in the arterioles and capillaries in the heart, liver, and kidneys, as well as platelet/fibrin thrombi in the pulmonary vasculature (Figure3A); no thrombi were seen in control mice (Figure 3B). The presence of hPF4 was demonstrated, by immunostaining with RTO, in thrombi in the lungs (Figure 3C,E; arterial and venous, respectively), while staining with an isotype control antibody was negative (Figure 3D,F; arterial and venous, respectively). Similar results were observed in multiple organs including the heart (coronary arteries), brain (meningeal vessels), and liver (in sinusoids) (data not shown). Fibrin in the urinary space of the glomerulus (hematoxylin and eosin staining) did not stain for PF4, presumably because it is probably due to leakage of fibrin/fibrinogen secondary to shock and not thrombosis (data not shown).

Vascular pathology in FcγRIIA/hPF4 mice injected with anti-hPF4/heparin antibody and heparin.

Hematoxylin/eosin–stained lung sections from KKO/heparin–treated FcγRIIA/hPF4 mice show intravascular fibrin precipitation and thrombus formation in arterioles and capillaries, as indicated by arrows (panel A, 100 ×), while lung sections from FcγRIIA/hPF4 mice injected with KKO/saline (panel B, 100 ×) show no evidence of thrombus formation. Thrombi in the lungs (panel C, 40 ×; panel E, 20 ×; arterial and venous, respectively) were rich in hPF4, as shown by immunostaining with RTO, a monoclonal antibody specific for hPF4, while staining with an isotype control antibody was negative (panel D, 40 ×; panel F, 20 ×; arterial and venous, respectively).

Vascular pathology in FcγRIIA/hPF4 mice injected with anti-hPF4/heparin antibody and heparin.

Hematoxylin/eosin–stained lung sections from KKO/heparin–treated FcγRIIA/hPF4 mice show intravascular fibrin precipitation and thrombus formation in arterioles and capillaries, as indicated by arrows (panel A, 100 ×), while lung sections from FcγRIIA/hPF4 mice injected with KKO/saline (panel B, 100 ×) show no evidence of thrombus formation. Thrombi in the lungs (panel C, 40 ×; panel E, 20 ×; arterial and venous, respectively) were rich in hPF4, as shown by immunostaining with RTO, a monoclonal antibody specific for hPF4, while staining with an isotype control antibody was negative (panel D, 40 ×; panel F, 20 ×; arterial and venous, respectively).

Discussion

FcγRIIA has been implicated in the pathogenesis of HIT/HITT on the basis of in vitro studies. We have now studied the role of this receptor in vivo through the use of transgenic mice expressing FcγRIIA, for which there is no mouse counterpart.28 To simulate the pathogenesis of HIT/HITT, we developed single- and double-transgenic mice expressing hPF4 and/or FcγRIIA. We injected these mice with KKO, a mouse monoclonal antibody that recognizes hPF4/heparin complexes; competes with a subset of human HIT/HITT antibodies for binding the complex; activates human platelets in vitro in a PF4-, heparin-, and FcγRIIA-dependent manner; and, like most human HIT sera, does not bind mouse PF4 whether or not it is in complex with heparin.33

Our data demonstrate that the anti-PF4/heparin antibody causes profound thrombocytopenia (mean 80% drop in platelet count) only in the presence of both endogenously expressed hPF4 and FcγRIIA in mice exposed to heparin. Thrombocytopenia was transient despite the continued administration of heparin, with the time course of recovery consistent with the clearance of antibody and a compensatory increase in platelet production. Mice expressing comparable amounts of hPF4 in the absence of FcγRIIA did not develop thrombocytopenia. Thus, these data establish unequivocally that the expression of FcγRIIA markedly exacerbates thrombocytopenia mediated by an HIT-like antibody.

Although every double-transgenic mouse developed severe thrombocytopenia when exposed to heparin at 20 U/d, none developed clinical evidence of thrombosis. We reasoned that the expression of endogenous mouse PF4, which is not recognized by this mouse monoclonal antibody (KKO), whether or not it is complexed with heparin,33 may have been released when platelets were activated by antibody and competed with the human transgene product for complex formation. We are currently pursuing an approach to eliminate the possible confounding influence of endogenous mouse PF4, as FcγRIIA/hPF4 transgenic mice will be bred to a line in which the mouse PF4 gene has been knocked out (unpublished observations, 2000). To increase the probability of forming hPF4/heparin complexes in the presence of endogenous mouse PF4, mice were given monoclonal anti-PF4/heparin antibody and a higher amount of heparin (50 U/d). FcγRIIA/hPF4 mice subjected to higher heparin dose developed shock, which was not seen at the lower dose. Similarly treated mice transgenic only for hPF4 did not become thrombocytopenic and showed no evidence of shock. Histologic analysis showed extensive thrombotic occlusion of the microvasculature in multiple organs. Immunostaining with hPF4-specific monoclonal antibodies demonstrated the presence of hPF4 in the thrombi found in the lungs, coronary arteries, brain, and other organs. Additional studies will be required to elucidate the contribution of platelet incorporation into microthrombi as well as Fcγ receptor–mediated clearance to the pathogenesis of thrombocytopenia and thrombosis.30

We have previously shown that mice transgenic for human FcγRIIA develop a more rapid and severe thrombocytopenia when exposed to platelet-activating antibodies than when exposed to comparable amounts of nonactivating antibodies.30 Further, reduction of splenic clearance in FcγRIIA mice injected with platelet-activating antibodes resulted in shock and thrombosis. We have now extended these observations to the pathogenesis of HIT/HITT and have established the role of anti-PF4/heparin antibodies and FcγRIIA in the pathogenesis of thrombocytopenia and thrombosis in vivo. We anticipate that this FcγRIIA/hPF4 model will facilitate the analysis of the contribution of antibody specificity, platelet Fcγ receptor density, splenic clearance, inflammation, and endogenous vascular disease to the propensity to develop thrombosis. It is also likely that a better appreciation of the pathogenesis of thrombosis in this double-transgenic model will facilitate the investigation into alternative strategies for intervention in this life-threatening iatrogenic disease. Finally, the FcγRIIA/hPF4 transgenic mouse model may offer insights into other diseases that exhibit immune-mediated thrombocytopenia and thrombosis, such as the antiphospholipid syndromes, systemic lupus erythematosus, and disseminated intravascular coagulation associated with sepsis.

We thank Drs Diana Cassel, Zheng Cui, Joseph Tuckosh, and Michael Feldman for their help, and Dr Jean Richa and the staff at the Transgenic Mouse Core Facility at the University of Pennsylvania.

Supported in part by National Institutes of Health grants R01 HL61865, P01 Hl-40387, P50 H-54500, and HL04009-02 (K08); the University of New Mexico Cancer Research and Treatment Center; and the Nemours Foundation.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Steven E. McKenzie, Cardeza Foundation for Hematologic Research, Department of Medicine, Jefferson Medical College, 1015 Walnut St, Philadelphia, PA 19107; e-mail:steven.mckenzie@mail.tju.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal