Key Points

Mutations in ARID1A and CSF1R are recurrently gained at relapse in AML and represent novel therapeutic options for patients with relapsed AML.

Recurrent somatic mutations in H3F3A and UBTF are age specific in relapsed AML, detected solely in adult and pediatric AML, respectively.

Abstract

Relapse is the leading cause of death of adult and pediatric patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Numerous studies have helped to elucidate the complex mutational landscape at diagnosis of AML, leading to improved risk stratification and new therapeutic options. However, multi–whole-genome studies of adult and pediatric AML at relapse are necessary for further advances. To this end, we performed whole-genome and whole-exome sequencing analyses of longitudinal diagnosis, relapse, and/or primary resistant specimens from 48 adult and 25 pediatric patients with AML. We identified mutations recurrently gained at relapse in ARID1A and CSF1R, both of which represent potentially actionable therapeutic alternatives. Further, we report specific differences in the mutational spectrum between adult vs pediatric relapsed AML, with MGA and H3F3A p.Lys28Met mutations recurrently found at relapse in adults, whereas internal tandem duplications in UBTF were identified solely in children. Finally, our study revealed recurrent mutations in IKZF1, KANSL1, and NIPBL at relapse. All of the mentioned genes have either never been reported at diagnosis in de novo AML or have been reported at low frequency, suggesting important roles for these alterations predominantly in disease progression and/or resistance to therapy. Our findings shed further light on the complexity of relapsed AML and identified previously unappreciated alterations that may lead to improved outcomes through personalized medicine.

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) arises from malignant transformation of myeloid progenitor cells, overgrowing functional blood cells in the bone marrow (BM) before infiltrating peripheral blood and possibly other organs. AML is primarily a disease of elderly people, with an average age at onset of 68 years,1 but the disease also occurs in children. Most patients achieve complete remission after intensive chemotherapy, sometimes followed by allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. However, 40% to 60% of adults and 35% of children relapse within 3 years,2-5 with most of the relapse patients not responding to conventional treatment, resulting in a 5-year overall survival of 28% and 65%, respectively.1,6

During the past decade, the AML inter- and intratumor heterogeneity have been investigated, resulting in improved classification2 and novel treatment alternatives.7-9 Further, age-specific characteristics indicate differences in the landscape and tumorigenesis of adult vs pediatric AML.10 Mutational studies of AML relapses have mainly been performed with gene panels11-13 or whole-exome sequencing (WES),14-16 whereas the largest published longitudinal whole-genome sequencing (WGS) study to date interrogated only 8 AML diagnosis-relapse pairs.17 More recently, a gene panel–based, single-cell DNA-sequencing study including AML cells from relapsed patients was published, but comprised relapse/refractory specimens from only 25 patients.18 Thus, a further increased understanding of the biological characteristics of the disease and genomic alterations occurring in relapsed and primary resistant (R/PR) AML is needed to improve personalized treatment and patient survival.

In this study, we performed WGS and WES of R/PR samples from 73 cases of AML, including 52 patient-matched diagnosis samples. We report specific mutational differences between our R/PR AML cohort and newly diagnosed cases in previous studies, but also in comparison with former non–WGS-based relapse studies. Finally, we identify unreported differences in the mutational landscape of adult vs pediatric relapsed AML.

Patients and methods

Cohort

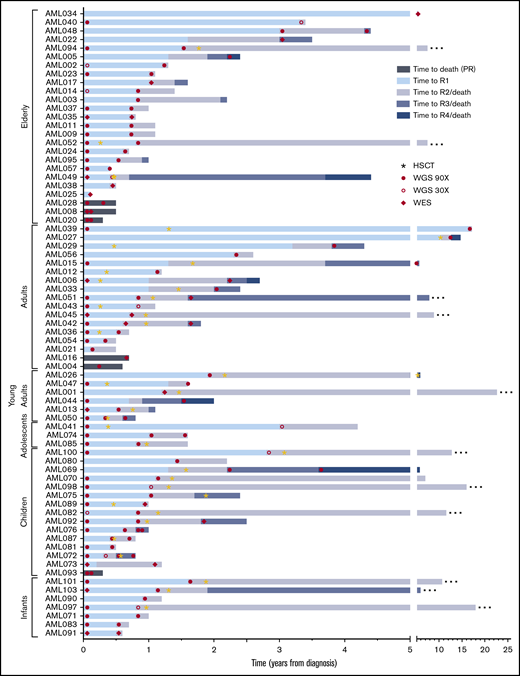

Included in the study were primary sequential specimens from 48 adult and 25 pediatric patients with AML from the Nordic countries, all of whom had relapsed or PR disease. All patients were diagnosed according to World Health Organization criteria.19 Only cases with relapse or PR specimens of sufficient quality and yield available via the Uppsala Biobank or Karolinska Institute Biobank, collected from 1995 through 2016, were included. Cases of the clinically distinct acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) subtype were excluded. Sixty-six patients had de novo AML, whereas the remaining 7 had a prior diagnosis of a myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) or other malignancy. Associated clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1, Figure 1, supplemental Tables 1-3, and supplemental Figures 1 and 2. Informed consent was obtained according to the Declaration of Helsinki, and study approval was acquired from the Uppsala Ethical Review Board (Sweden) and the Regional Ethics Committee South-East (Norway).

Patient cohort

| . | Data . |

|---|---|

| Patients | 73 (100) |

| Adult cases | 48 (65.8) |

| Elderly (≥60 y) | 25 (34.2) |

| Adult (40-59 y) | 17 (23.3) |

| Young adult (19-39 y) | 6 (8.2) |

| Pediatric cases | 25 (34.2) |

| Adolescent (15-18 y) | 3 (4.1) |

| Child (3-14 y) | 15 (20.5) |

| Infant (<3 y) | 7 (9.6) |

| Sex, female | 38 (52.1) |

| Background | |

| De novo AML | 66 (90.4) |

| Potential t-AML | 3 (4.0) |

| MDS-AML | 2 (2.7) |

| t-MDS-AML | 2 (2.7) |

| Tumor samples | 138 (100) |

| Diagnosis samples | 52 (37.7) |

| Relapse samples | 80 (58.0) |

| R1 and R1-P | 60 (43.5) |

| R2 and R2-P | 16 (11.6) |

| R3 | 4 (2.9) |

| Primary resistant samples | 6 (4.3) |

| Matched normal controls | 61 (100) |

| BMS cells | 43 (70.5) |

| Complete remission samples | 17 (27.9) |

| BMS/complete remission cell combination | 1 (1.6) |

| Average age at onset, y | |

| Adult cases | 59.3 (range, 20.5-83.1; median, 61.7) |

| Pediatric cases | 8.2 (range, 0.4-18.2; median, 7.7) |

| Average length of EFS, d (D>R1) | |

| Adult relapse cases | 624 (range, 34-5958; median, 306) |

| Pediatric relapse cases | 365 (range, 69-1110; median, 312.5) |

| Average WBC | |

| Adult cases* | 100 (range, 1-395; median, 80) |

| Pediatric cases | 104 (range, 11-232; median, 50) |

| NK-AML | |

| Adult cases† | 21 (46.7) |

| Pediatric cases | 7 (28.0) |

| Sample purity | 86% (>80% tumor cells; range, 41-100) |

| Cell viability‡ | 61% (≥75% viable cells; range, 6-94) |

| Sampling duration | 1995 through 2016 |

| . | Data . |

|---|---|

| Patients | 73 (100) |

| Adult cases | 48 (65.8) |

| Elderly (≥60 y) | 25 (34.2) |

| Adult (40-59 y) | 17 (23.3) |

| Young adult (19-39 y) | 6 (8.2) |

| Pediatric cases | 25 (34.2) |

| Adolescent (15-18 y) | 3 (4.1) |

| Child (3-14 y) | 15 (20.5) |

| Infant (<3 y) | 7 (9.6) |

| Sex, female | 38 (52.1) |

| Background | |

| De novo AML | 66 (90.4) |

| Potential t-AML | 3 (4.0) |

| MDS-AML | 2 (2.7) |

| t-MDS-AML | 2 (2.7) |

| Tumor samples | 138 (100) |

| Diagnosis samples | 52 (37.7) |

| Relapse samples | 80 (58.0) |

| R1 and R1-P | 60 (43.5) |

| R2 and R2-P | 16 (11.6) |

| R3 | 4 (2.9) |

| Primary resistant samples | 6 (4.3) |

| Matched normal controls | 61 (100) |

| BMS cells | 43 (70.5) |

| Complete remission samples | 17 (27.9) |

| BMS/complete remission cell combination | 1 (1.6) |

| Average age at onset, y | |

| Adult cases | 59.3 (range, 20.5-83.1; median, 61.7) |

| Pediatric cases | 8.2 (range, 0.4-18.2; median, 7.7) |

| Average length of EFS, d (D>R1) | |

| Adult relapse cases | 624 (range, 34-5958; median, 306) |

| Pediatric relapse cases | 365 (range, 69-1110; median, 312.5) |

| Average WBC | |

| Adult cases* | 100 (range, 1-395; median, 80) |

| Pediatric cases | 104 (range, 11-232; median, 50) |

| NK-AML | |

| Adult cases† | 21 (46.7) |

| Pediatric cases | 7 (28.0) |

| Sample purity | 86% (>80% tumor cells; range, 41-100) |

| Cell viability‡ | 61% (≥75% viable cells; range, 6-94) |

| Sampling duration | 1995 through 2016 |

Data are number of patients (% of total group), unless otherwise stated. Detailed biological and clinical data for each patient/sample are presented in supplemental Tables 2 and 3.

BMS, bone marrow–derived stromal cells; D, diagnosis; NK-AML, normal karyotype AML at diagnosis; R1/2/3, sequential relapses; R1/2-P, persistent relapse specimen; t-AML, treatment related AML; WBC, white blood cell count (at diagnosis).

Information lacking for 6 adults.

Information lacking for 3 adults.

Accounts only for cryopreserved cells.

Event timeline of the study cohort. The time from diagnosis to longitudinal events for each patient is shown. Cases are depicted from top to bottom, grouped based on age at onset. Stars indicate occurrence of an allogeneic HSCT. Samples included in the current study as well as the next-generation sequencing method applied are indicated by filled circles (WGS, 90×), open circles (WGS, 30×), and diamonds (WES). Patients in remission at the latest follow-up are indicated with an ellipsis at the end of the respective bar. R1/2/3/4, sequential relapses; HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

Event timeline of the study cohort. The time from diagnosis to longitudinal events for each patient is shown. Cases are depicted from top to bottom, grouped based on age at onset. Stars indicate occurrence of an allogeneic HSCT. Samples included in the current study as well as the next-generation sequencing method applied are indicated by filled circles (WGS, 90×), open circles (WGS, 30×), and diamonds (WES). Patients in remission at the latest follow-up are indicated with an ellipsis at the end of the respective bar. R1/2/3/4, sequential relapses; HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

Sample preparation

Mononuclear cells were enriched through Ficoll gradient centrifugation and cryopreserved or stored as frozen pellets until they were used. Cryopreserved AML specimens with leukemia cell content <80% were, if applicable, purified by immune-based depletion of nontumor cells (supplemental Table 4). Normal BM-derived stromal cells were cultivated from leukemic BM according to a published method20 as a source of germline DNA. Genomic DNA was obtained with Qiagen extraction kits.

NGS

Library preparation and next-generation sequencing (NGS; WGS: HiSeq X, Illumina [San Diego, CA]; WES: Ion Proton, Thermo Fisher Scientific [Waltham, MA]) were performed at the Science for Life Laboratory (SciLifeLab), National Genomics Infrastructure (Uppsala, Sweden). Detailed information, including variant calling, filtering, and validation, is provided in supplemental Methods.

Statistics

Kaplan-Mayer curves and associated statistical tests were generated in GraphPad Prism 7.02. Other statistical tests were performed in R,21 as detailed in supplemental Methods.

Results

We studied diagnosis (n = 52), relapse (n = 80), and PR specimens (n = 6) from 48 adult and 25 pediatric patients with R/PR AML, including 52 diagnosis-R/PR pairs (Table 1; Figure 1; supplemental Tables 1-3).

WGS of 111 leukemia samples from 60 of the patients (37 adults; 23 children) reached a mean coverage of 114× (n = 99; aim, ≥ 90×), and 39× (n = 12; aim, ≥30×), whereas WGS of patient-matched normal DNA from those patients reached 38× (aim, ≥30×; supplemental Table 5). An average of 2063 somatic single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) and small insertion/deletion mutations (indels) were detected per sample, with higher mutational frequencies in adults than in children at both diagnosis and relapse (supplemental Figure 3), correlating with previous findings.10,17,22 Investigation of substitutional patterns in adults revealed a significant increase of transversions over the course of the disease (P = 2.1 × 10−5; supplemental Table 6; supplemental Figure 4), concordant with former studies.14,17 Children had a significantly higher fraction of transversions at diagnosis than did adults (P = 4.1 × 10−3), underlining accumulation of transition mutations with age,23 leading up to diagnosis. Relapse-specific mutations, however, were dominated by transversions independent of age, strengthening the assertion that chemotherapy affects the mutational landscape at relapse.14,17,24

WES was performed for an additional 27 leukemia samples from 20 patients with a mean coverage of 131× (supplemental Tables 1 and 7).

Copy number alterations and structural variants in R/PR AML

The presence of somatic DNA copy number alterations (CNAs) and copy-neutral loss-of-heterozygosity (CN-LOH) was investigated in all samples. The most common aberrations were trisomy 8 (n = 11 cases; 15.1%), and gains, losses, and CN-LOH involving chromosome 17 (n = 10; 13.7%; supplemental Table 8). Monosomy 5 or 7 or del7q were found at relapse in 2 adult cases and in 2 adult PR cases (8.3% of adults), but were not seen in children.

Various types of structural variants (SVs) can be detected by WGS, whereas they are often impossible to identify by WES. In the 60 cases of AML that were subjected to WGS, we identified an average of 2.0 somatic SVs per sample, including translocations leading to the gene fusion RUNX1-RUNX1T1 (8 of 60; 13.3%) and NUP98 fusions (4 of 60; 6.7%; supplemental Tables 9 and 10). In addition, various translocations rendering dysfunctional ETV6 transcripts were found in 5 cases (8.3%). Of note is that common AML-associated gene fusions were overrepresented in pediatric AML (11 of 23; 47.8%), compared with adult AML (7 of 37; 18.9%). SVs and CNAs were mainly stable or gained during progression of leukemia (Figure 2).

The mutational landscape of R/PR AML. Recurrently altered genes/functional gene groups in all 48 adult and 25 pediatric R/PR AML cases, including evolutional patterns in patient-matched diagnosis and R/PR samples (30 adult and 22 pediatric pairs). Included are recurrent nonsynonymous SNVs and small indels, translocations involving genes commonly altered in AML, and CNAs of whole chromosomes/chromosomal arms detected by WGS and WES. The cases were categorized into risk groups (adverse, intermediate, and favorable) based on the European LeukemiaNet–risk classification2 for adult AML and the NOPHO-DBH AML 2012 Protocol (study registered at EudraCT as #2012-002934-35) for pediatric AML. A short EFS was <0.5 years for adults and <1.0 years for pediatric patients. +, copy number amplification; ¤, copy number deletion; *, CN-LOH; EFS, event-free survival; NGS, next-generation sequencing; D, diagnosis; R, relapse; LOY, loss of chromosome Y. Digits within individual boxes refer to the number of alterations within the gene or the number of altered genes within a functional group at D/R or D/PR; DS, Down syndrome; AB, ABCA12; AR, ARHGAP31; DN, DNAH3; FA, FAT3; NI, NIPBL; NR, NRXN3; RA, RAD21; SF, SF3B3; SM, SMC1A/3; SR, SRSF1/2/6; ST, STAG1/2; SY, SYNE1; U2, U2AF1; ZN, ZNF91; and ZR, ZRSR2. See supplemental Table 12D for details regarding samples included in this figure.

The mutational landscape of R/PR AML. Recurrently altered genes/functional gene groups in all 48 adult and 25 pediatric R/PR AML cases, including evolutional patterns in patient-matched diagnosis and R/PR samples (30 adult and 22 pediatric pairs). Included are recurrent nonsynonymous SNVs and small indels, translocations involving genes commonly altered in AML, and CNAs of whole chromosomes/chromosomal arms detected by WGS and WES. The cases were categorized into risk groups (adverse, intermediate, and favorable) based on the European LeukemiaNet–risk classification2 for adult AML and the NOPHO-DBH AML 2012 Protocol (study registered at EudraCT as #2012-002934-35) for pediatric AML. A short EFS was <0.5 years for adults and <1.0 years for pediatric patients. +, copy number amplification; ¤, copy number deletion; *, CN-LOH; EFS, event-free survival; NGS, next-generation sequencing; D, diagnosis; R, relapse; LOY, loss of chromosome Y. Digits within individual boxes refer to the number of alterations within the gene or the number of altered genes within a functional group at D/R or D/PR; DS, Down syndrome; AB, ABCA12; AR, ARHGAP31; DN, DNAH3; FA, FAT3; NI, NIPBL; NR, NRXN3; RA, RAD21; SF, SF3B3; SM, SMC1A/3; SR, SRSF1/2/6; ST, STAG1/2; SY, SYNE1; U2, U2AF1; ZN, ZNF91; and ZR, ZRSR2. See supplemental Table 12D for details regarding samples included in this figure.

Overview of recurrent protein coding mutations in R/PR AML

Next, we mined our NGS data for somatic nonsynonymous SNVs and indels, identifying mutations in 1205 different genes. Of these, 41 genes were mutated at diagnosis and/or in R/PR specimens in at least 3 cases (supplemental Table 11). We found differences in mutational patterns between adult and pediatric cases (Figure 3A-B) and in a comparison of (patient-matched) diagnosis and R/PR specimens (Figures 2 and 4).

Variant frequencies in R/PR AML. (A) Recurrent SNVs and small indels discovered in the R/PR AML cohort. Displayed are the frequencies of recurrent gene mutations at diagnosis and R/PR stages among all adult (n = 48) and pediatric (n = 25) cases. (B) Mutational frequencies of indicated functional gene groups at diagnosis and R/PR stages in adult and pediatric AML. (C) Variants lost and gained during leukemic progression. Shown are the proportions of protein coding SNVs and small indels identified in the 27 adult and 20 pediatric AML cases (total n = 47) for which patient-matched diagnostic and relapse specimens were available, according to their presence at diagnosis and/or relapse. Total variants, n = 843 (adult, n = 519; pediatric, n = 324). Detailed information regarding samples used for generating this figure is present in supplemental Table 12E-F. D, diagnosis.

Variant frequencies in R/PR AML. (A) Recurrent SNVs and small indels discovered in the R/PR AML cohort. Displayed are the frequencies of recurrent gene mutations at diagnosis and R/PR stages among all adult (n = 48) and pediatric (n = 25) cases. (B) Mutational frequencies of indicated functional gene groups at diagnosis and R/PR stages in adult and pediatric AML. (C) Variants lost and gained during leukemic progression. Shown are the proportions of protein coding SNVs and small indels identified in the 27 adult and 20 pediatric AML cases (total n = 47) for which patient-matched diagnostic and relapse specimens were available, according to their presence at diagnosis and/or relapse. Total variants, n = 843 (adult, n = 519; pediatric, n = 324). Detailed information regarding samples used for generating this figure is present in supplemental Table 12E-F. D, diagnosis.

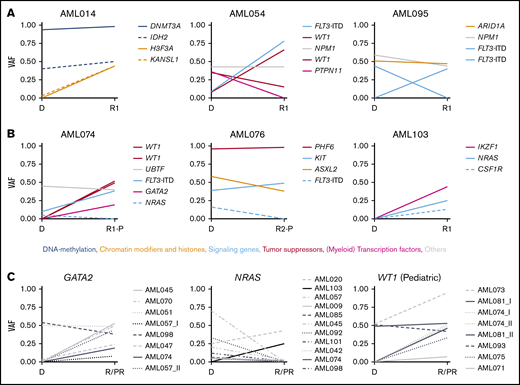

Changes in VAF in longitudinal patient-matched AML samples. (A-B): Distribution of nonsynonymous SNVs and small indels among representative patient-matched longitudinal AML samples from 3 adult (A) and 3 pediatric (B) cases. (C) Changes in VAF between patient-matched diagnosis and R/PR samples for GATA2, NRAS, and WT1. Detailed information regarding samples used for generating this figure is present in supplemental Table 12G. Additional graphs with recurrently altered genes as well as all adult and pediatric patient-matched longitudinal diagnostic and R/PR samples are presented in supplemental Figures 6-8. D, diagnosis; VAF, variant allele frequency.

Changes in VAF in longitudinal patient-matched AML samples. (A-B): Distribution of nonsynonymous SNVs and small indels among representative patient-matched longitudinal AML samples from 3 adult (A) and 3 pediatric (B) cases. (C) Changes in VAF between patient-matched diagnosis and R/PR samples for GATA2, NRAS, and WT1. Detailed information regarding samples used for generating this figure is present in supplemental Table 12G. Additional graphs with recurrently altered genes as well as all adult and pediatric patient-matched longitudinal diagnostic and R/PR samples are presented in supplemental Figures 6-8. D, diagnosis; VAF, variant allele frequency.

In cases with available patient-matched diagnosis and relapse samples (27 adults; 20 children; supplemental Table 12), 843 SNVs and indels were found at diagnosis or relapse (supplemental Table 11). Of those, 109 (12.9%) were present only at diagnosis, whereas 283 (33.6%) were gained at relapse (Figure 3C), emphasizing the importance of plasticity within leukemogenesis. Highly similar findings were seen when adult and pediatric cases were examined separately.

Recurrent UBTF-ITDs identified in pediatric relapsing AML

We found heterozygous in-frame internal tandem duplications (ITDs) in UBTF at diagnosis and relapse in 3 of 25 pediatric cases (12.0%; Figure 2; supplemental Table 10), whereas no UBTF alterations were identified in the adults. UBTF encodes upstream binding transcription factor, which has an essential role in facilitating ribosomal RNA transcription.25 All UBTF-ITDs involved exon 13, encoding 1 of 6 DNA-binding domains in UBTF. Reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction on UBTF-ITD+ samples showed expression of both the mutated and wild-type (WT) UBTF allele (supplemental Figure 5).

Loss-of-function mutations in MGA in adult relapsing AML

Loss-of-function mutations in MGA were identified at relapse in 4 of 48 adult cases and at diagnosis in 1 adult (subclonal), but were lost at relapse in this adult case (10.4%; Figure 2). MGA encodes a transcription factor that suppresses binding of MYC to its target sites.26 It has been found to be recurrently inactivated in 5% of cases of AML that have partial tandem duplications (PTDs) in KMT2A.27 However, none of our cases with MGA mutations had KMT2A-PTDs, suggesting overrepresentation of MGA mutations at relapse in adult KMT2A-PTD− AML.

H3F3A p.Lys28Met mutations and alterations in genes encoding chromatin modifiers

We discovered clonal p.Lys28Met mutations in H3F3A, encoding histone H3.3, at relapse in 3 adult cases (6.3%), whereas alterations of this gene were not seen at diagnosis in adults or at any disease stage in children (Figure 2; supplemental Table 10).

Further, we found mutations in various genes involved in chromatin modification at diagnosis and/or R/PR in 16 adult (33.3%) and 5 pediatric (20.0%) cases, with 14 of the patients being >60 years of age at diagnosis (56.0% of 25 elderly cases), consistent with previous findings28-30 (Figure 2; supplemental Table 10). These included ARID1A (3 adults [6.3%]), ASXL1/2 (5 adults [10.4%]; 3 children [12.0%]), BCOR/BCORL1 (6 adults [12.5%]), KANSL1 (2 adults [4.2%]) and KMT2A (4 adults [8.3%]; 2 children [8.0%]; Figure 3A-B). These mutations were mainly mutually exclusive. Further, all KMT2A-PTD+ cases had sequence mutations in RUNX1 and altered FLT3 (Figures 2 and 5). KANSL1 encodes a histone acetylation complex member.31 The KANSL1 mutations were either missing or subclonal at diagnosis, but were clonal at relapse. In addition, 2 of 3 mutations in ARID1A appeared at relapse (Figure 2; supplemental Figures 6 and 7). Of note is that half of our PR cases had mutations in chromatin modification–associated genes, altogether leaving an overrepresentation of alterations in these genes in R/PR specimens.

Co-occurrence and mutual exclusion of mutations in recurrently altered genes in relapsing AML. Co-occurrence and mutual exclusion of mutations in adults at diagnosis (A) and relapse (B), and in children at diagnosis (C) and relapse (D). Significance was calculated using a pairwise Fisher’s exact test. •P < .1; *P < .05. The odds ratio (OR) gives directionality, with OR >1 indicating co-occurrence (green) and OR <1 indicating mutual exclusion (brown). The number of mutated cases for each gene is shown in brackets. Detailed information regarding samples used for generating this figure is presented in supplemental Table 12H.

Co-occurrence and mutual exclusion of mutations in recurrently altered genes in relapsing AML. Co-occurrence and mutual exclusion of mutations in adults at diagnosis (A) and relapse (B), and in children at diagnosis (C) and relapse (D). Significance was calculated using a pairwise Fisher’s exact test. •P < .1; *P < .05. The odds ratio (OR) gives directionality, with OR >1 indicating co-occurrence (green) and OR <1 indicating mutual exclusion (brown). The number of mutated cases for each gene is shown in brackets. Detailed information regarding samples used for generating this figure is presented in supplemental Table 12H.

RTK-associated mutations are recurrently gained at relapse, whereas RAS signaling-related mutations commonly are lost

Recurrent somatic mutations were identified in receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) or RAS signaling-related genes at diagnosis and/or at R/PR in 31 adults (64.6%) and 18 children (72.0%; Figure 3A-B; supplemental Table 10). Among those, ITDs and SNVs were identified in FLT3 (13q12.2) in 18 adults (37.5%) and 8 children (32.0%). Half of the cases with FLT3 mutation co-occurred with amplification or CN-LOH on 13q, leading to biallelic FLT3 alterations. In at least 5 of the cases with aberrant 13q (38.5%), the CN-LOH appeared at relapse (Figure 2).

KRAS and NRAS were mutated in adult (n = 4 [8.3%] and n = 7 [14.6%], respectively) and pediatric (n = 4 [16.0%] and n = 9 [36.0%], respectively) cases of AML. These mutations frequently were subclonal, and commonly co-occurred within the same patient (Figure 5A). In 10 of 19 cases with KRAS and/or NRAS mutations, the mutation disappeared during progression of leukemia (Figure 4C; supplemental Figures 6-8).

We identified inactivating alterations in NF1 in 3 adult cases (6.3%; including 1 PR patient) and 2 pediatric cases (8.0%). A recent study32 reported NF1 alterations in 5.1% of adult cases, with an association with poor outcome, correlating with our findings for adult R/PR AML.

One-fifth of pediatric cases (n = 5 [20.0%]) had KIT mutations, compared with 8.3% of adults (n = 4). With 1 exception, these mutations were stable during progression of the leukemia (supplemental Figures 6-8). Furthermore, 6 of 9 KIT-mutated cases (66.7%) co-occurred with RUNX1-RUNX1T1.

CSF1R and CSF3R encode transmembrane RTKs for CSF1 and CSF3, respectively, which are cytokines that control production, differentiation, and function of macrophages and granulocytes, respectively.33,34 CSF3R frameshift mutations were found in 1 adult PR case, and in 1 infant. For CSF1R, 1 in-frame deletion in the juxtamembrane domain and a missense mutation in the activation loop appeared at relapse in 1 adult and 1 infant, respectively.

Recurrent gain of mutations that affect transcription regulation

We identified recurrent somatic mutations in genes encoding (myeloid) transcription regulators at diagnosis and/or R/PR in 16 adults (33.3%) and 12 children (48.0%; Figure 3A-B; supplemental Table 10). Missense, frameshift, and nonsense mutations in RUNX1 were found in 8 adult (16.7%) and 3 pediatric (12.0%) cases, with 4 of the 11 patients (36.4%) having PR AML.

Mutations in GATA2 were identified in 5 adult cases (10.4%). The mutation was subclonal at diagnosis in 2 of these, whereas it was clonal at relapse and appeared at relapse in at least 1 case (Figures 2 and 4C). In pediatric AML, mutually exclusive mutations were found in GATA1 (n = 2; 8.0%) and GATA2 (n = 3; 12.0%; appearing at a refractory relapse in 1 case). In previous studies of diagnostic and/or relapse specimens, 1% to 15% of adult and only 4% of pediatric cases of non-APL AML had GATA1/2 mutations,10,14,16,22,35,36 implying an overrepresentation of mutations within these genes in our pediatric cohort with relapsing AML.

IKZF1 (7p12.2) was mutated in 2 adult (4.2%) and 2 pediatric (8.0%) cases, with 2 of these mutations appearing at relapse. IKZF1 encodes an important transcription factor in leukocyte differentiation.37 This gene is rarely found to be mutated in AML (eg, 0.5%-2.7% of pediatric cases10,38 ), whereas loss of 1 IKZF1 allele occurs as part of monosomy 7. Further, focal deletion of IKZF1 occurs infrequently in pediatric AML.39 In our cohort, 1 pediatric case had a 7p14.2-p11.2 deletion involving IKZF1. Further, 2 adult PR cases had monosomy 7, resepectively focal IKZF1 deletion, whereas monosomy 7 appeared at relapse in another adult case, leaving the IKZF1 alteration frequency at 10.4% and 12.0% in R/PR adult and pediatric AML, respectively (Figure 2; supplemental Table 10).

Alterations of tumor suppressor genes are commonly gained at relapse

Various tumor suppressor genes were mutated at diagnosis and/or R/PR in 18 adults (37.5%) and 12 (48.0%) children. These mutations were frequently gained or showed an increase in variant allele frequency at relapse, but were never lost (Figures 2, 3A-B, and 4; supplemental Figures 6-8). Among these, truncating mutations were found in PHF6 (adults, n = 2 [4.2%]; children, n = 3 [12.0%]), with the mutation appearing at relapse in 1 child, whereas another child had it in PR AML. Further, mutually exclusive alterations were identified in TP53 (adults, n = 6 [12.5%]; children, n = 3 [12.0%]) and WT1 (adults, n = 11 [22.9%]; children n = 7 [28.0%]). For at least 4 of 11 (36.4%) WT1-mutated adult cases and 3 of 7 (42.9%) WT1-mutated pediatric cases, the mutation appeared during progression of the leukemia (Figure 4C). Of note is that 75% of the mutations in WT1 co-occurred with FLT3 alterations (Figure 5).

TP53 alterations have been linked to chromothripsis40 and aneuploidy.41 No severe aneuploidy was found in our AML samples with TP53 mutations. However, leukemia cells with TP53 mutations from 4 patients had complex interchromosomal translocations, indicative of chromothripsis (supplemental Table 10). For at least 2 of these events, the rearrangements appeared at relapse, with the TP53 alteration acquired during progression of leukemia in one of them.

Mutations in cohesin-associated genes recurrently appear during the progression of leukemia

We identified mutations in several genes encoding proteins associated with the cohesin complex, which regulates the separation of sister chromatids during cell division.42 Five adult (10.4%) and 5 pediatric (20.0%) cases had mutually exclusive mutations in 1 of these genes at diagnosis and/or R/PR (NIPBL [1 adult, 2.1%, and 1 child, 4.0%], RAD21 [3 children; 12.0%], SMC1A [2 adults; 4.2%], SMC3 [1 child; 4.0%], and STAG2 [2 adults; 4.2%]; Figures 2 and 3A-B; supplemental Table 10). In at least 4 of these 10 cases (40%), the mutation appeared during disease progression, and 2 had PR AML (supplemental Figures 6-8).

Alterations in spliceosome-related genes in relapsing AML

Seven adult (14.6%) and 2 pediatric (8.0%) cases had somatic mutations at diagnosis and/or R/PR in at least 1 spliceosome-related gene (SF3B1/3, SRSF1/2/6, U2AF1, and ZRSR2; Figures 2 and 3A-B; supplemental Table 10). Most common were missense- and in-frame indel mutations in SRSF2, found at relapse in 4 adults (8.3%), all lacking diagnostic specimens. However, missense mutations were shown to appear at relapse in SRSF1 and U2AF1 in 1 adult case each. Previous studies of adult AML report mutations in spliceosome-related genes in ∼22% of relapsed AML,14,15,35 whereas they are less frequent in pediatric AML (2% to 5%).10,22

Highly recurrent mutated genes in adult R/PR AML

The most frequent alteration found in adult R/PR AML was a frameshift mutation in NPM1 in 41.7% of cases (n = 20), consistent with a previous relapse study,14 whereas 30% to 35% were seen in former studies of diagnostic cohorts, irrespective of outcome32,36 (Figures 2 and 3A). These mutations were stable during progression of leukemia (supplemental Figure 6). Surprisingly, no NPM1 mutations were found in our pediatric cases, whereas previous pediatric AML studies, including relapsed cases, reported NPM1 mutations at 11% to 24%.10,12

Another striking difference between adult and pediatric AML involved a high frequency of mutations in DNA methylation-related genes in adult AML (60.4%), with complete absence of these in our pediatric cases, correlating with previous studies10,36 (Figure 3A-B). The mutated genes included DNMT3A (n = 16; 33.3%), IDH1 (n = 8; 16.7%), IDH2 (n = 6; 12.5%), and TET2 (n = 8; 16.7%). These mutations were stable during progression to relapse (supplemental Figure 6).

Very late relapses in adult AML are associated with H3F3A p.Lys28Met mutations

Two adult patients (AML027 and AML039) had their first relapse at 10.5 respectively 16 years after presentation (supplemental Tables 2 and 10). All alterations described in the clinical information at diagnosis for AML027 (FLT3-SNV; t(2;9)(q?21;q?22); +4) remained at a second relapse, with, for instance, an H3F3A p.Lys28Met mutation also found at this stage. For AML039, identical somatic mutations in IDH1, PHF6, and SMC1A and trisomy 8 were identified at diagnosis and relapse, whereas clonal mutations in, for instance, H3F3A, IKZF1, NF1, and TP53, were gained at relapse. These cases indicate the silent survival of diagnostic clones for more than a decade.

Discussion

We report the first multigenome sequencing study of longitudinal diagnosis, relapse, and/or PR specimens from adult and pediatric patients with AML (n = 73 cases), comprising 52 patient-matched diagnosis-R/PR pairs. By exploiting changes in variant composition in patient-matched diagnostic and relapse samples, we found that 53.5% of the mutations were present at both stages, suggesting clones that evade chemotherapeutic treatment (Figure 3C). The remaining variants were either lost or gained during progression of leukemia, implying that some variants are necessary for formation of leukemia but not for maintaining the leukemia clone(s), whereas others are advantageous during progression of leukemia and/or resistance of treatment.

UBTF-ITDs/indels are recurrent in pediatric R/PR AML. These were found in 12.0% of our pediatric cases (Figure 3A), as well as in 2 former studies43,44 that also identified the mutation solely in pediatric patients who eventually relapsed or had PR disease. The ITDs have a length known to be problematic for most current NGS-variant callers to detect (∼40-150 bp). One of our UBTF-ITDs was identified through manual review of the NGS reads. Further, some of the previously identified UBTF-ITDs were not found in the original analysis of the cohort,10 but after reanalysis by other scientists.43 Finally, most gene panels exclude this gene. Altogether, these difficulties in identification imply that UBTF-ITDs may be a previously unappreciated lesion in pediatric AML that is associated with progression of the disease and/or resistance of treatment. All ITDs were heterozygous, and that UBTF interacts with DNA as a dimer25 suggests that these mutations are either gain-of-function mutations or have a dominant negative function. Further studies are needed to elucidate the role of UBTF-ITDs in leukemogenesis.

One-third of mutations in genes encoding chromatin-modifying proteins were gained at relapse or were subclonal at diagnosis and emerged as clonal at relapse, pointing toward a central role for disturbed gene regulation via aberrant chromatin modification in progressing disease (supplemental Figure 6). For instance, 2 of 3 mutations in ARID1A appeared at relapse in adult AML. ARID1A mutations have been reported to be enriched in APL and in 1 study of FLT3-ITD+ AML (5% in both studies),24,45 but are otherwise rare in AML (<1% of cases10,16,36 ). Our cohort, however, excluded cases of APL, and both cases that gained an ARID1A mutation at relapse were FLT3-WT, suggesting enrichment of ARID1A mutations at relapse in adults with other AML subtypes. Further, truncating mutations in KANSL1 have been described in acute megakaryoblastic leukemia (AMKL),46 but sequence mutations have not been found in non-AMKL AML. In our KANSL1-mutated cases (4.2% of adults, non-AMKL subtype), the mutations emerged as clonal at relapse.

To our knowledge, there are no previously identified somatic, nonsynonymous CSF1R mutations in de novo AML, whereas we identified recurrent CSF1R alterations appearing at relapse (supplemental Table 10). Based on their structure and locality, these mutations are thought to cause aberrant activation of CSF1R,47 suggesting an important role for this receptor at relapse. Moreover, CSF1R inhibition has been proposed as an alternative treatment approach for AML.48

Very late relapse, defined as relapse after more than 5 years of remission, occurs in 1% to 3% of patients.49,50 Two adults in our cohort relapsed after 10.5 and 16 years, both with a subset of identical genomic lesions at relapse, as identified in their respective founder clone (supplemental Table 10). Of note is that both of these patients had p.Lys28Met mutations in H3F3A at relapse. The same mutation also emerged at relapse in a third adult case. An identical mutation has been found in MDS,51 in 1 patient with secondary AML,52 and in 1 patient with relapsed de novo AML.16 That it has not been reported at diagnosis in de novo AML suggests an important role for this mutation at AML relapse. Two of our H3F3A-mutated patients had de novo AML, whereas the third had suspected MDS-AML. In this latter case, however, the mutation appeared at relapse and is thus not expected to be associated with the initial onset of a potential secondary AML. The p.Lys28 amino acid is the target of (tri)methylation and acetylation associated with transcription repression and activation, respectively, of targeted genes,53,54 which suggests that more dramatic alterations to the chromatin state may aid in resistance to chemotherapy.

The mutational frequency in tumor suppressor genes, including PHF6, TP53, and WT1, was substantially higher in our R/PR cohort (adults, 37.5%; children, 48.0%) than previously reported in diagnosis-only cohorts (15% to 16%),10,36 as well as in various non–WGS-based R/PR AML studies (adult, 18%-27%; pediatric, 8% to 39%),14,15,22,24,35,38,44 with a frequent gain of variants in those genes during disease progression (Figures 2 and 3A-B). In line with former studies,14,15 mutations in WT1 commonly appeared at relapse, with remarkably high frequencies of 22.9% and 28.0% in adult and pediatric R/PR cases, respectively, but was reported at only 6.1% and 13.8% in adult and pediatric non-APL AML, respectively, in diagnostic cohorts.10,36 Furthermore, TP53 and PHF6 alterations, which have been reported in only 1.1% to 7.1%10,44 and 1.9% to 7.1%44,55 of children, respectively, were both seen in 12.0% of our pediatric cases, with no survivors among the patients, corroborating the association between TP53 alterations and poor outcome.2

Studies of pediatric AML have reported mutations in cohesin-associated genes in 0% to 8.3% of cases.10,22,38 Our pediatric R/PR cases, however, had a substantially higher mutational frequency, with 20.0% of cases with mutated NIPBL, RAD21, or SMC3 (Figures 2 and 3A-B). Our findings for adult AML, though, correlated with those in other studies of adult AML.14,15,35 The protein encoded by NIPBL is an important cohesin-loading factor.56 Mutations in this gene in AML are rare (0.6% in adults36 ; none reported in children), whereas recurrent mutations have been found in colorectal cancer.57 Low NIPBL expression has been associated with NPM1 mutations in AML,58 but our NIPBL-mutated cases were WT for NPM1. The majority of mutations in cohesin-associated genes appeared during disease progression or were found in PR AML. All of those patients died, highlighting a putative role for altered cohesin regulation in chemotherapy resistance in AML.

In summary, this investigation further elucidated the mutational landscape of R/PR AML. We identified the emergence at relapse of recurrent mutations in genes not previously reported in de novo AML (CSF1R) or identified at low frequency (eg, ARID1A, IKZF1, KANSL1, and NIPBL). Further, our results indicated specific differences in genes mutated in adult vs pediatric R/PR AML, exemplified by recurrent UBTF-ITDs exclusively in pediatric AML and H3F3A and MGA mutations only in adult AML. Our findings, showing great plasticity during progression of leukemia, support previous studies investigating relapsing AML, which mainly used WES and/or gene panels.11,14,15,17,18,22,24,35,38,45 The current study points out the limitations of gene panels when attempting to investigate the repertoire of relapse specific mutations, as many of the herein identified recurrently mutated genes commonly are excluded (eg, ARID1A, CSF1R/3R, H3F3A, MGA, and UBTF). Further, structural variants usually cannot be detected by WES and/or gene panels. Together, this highlights the importance of applying WGS in mutational studies of relapsed AML.

Although the frequency of several of the potentially actionable mutations identified in our study is relatively low, their identification is of great importance in the setting of personalized medicine. For instance, RTK inhibitors could be used for CSF1R-mutated cases,48 and bromodomain and extraterminal domain inhibitors have been suggested as a therapeutic option for ARID1A-mutated tumors.59 To fully understand this complex disease, however, more studies incorporating various multiomics analyses are necessary.

Custom codes and genomic data are available from the authors upon request, respectively via doi.org/10.17044/scilifelab.12292778.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Maria Lindström (Clinical Pathology, Uppsala University Hospital), Miha Purg (Department of Cell and Molecular Biology, Uppsala University), Clinical Genomics Uppsala (Science for Life Laboratory), and BioVis (Department of Immunology, Genetics and Pathology, Uppsala University) for technical support; U-CAN (Uppsala-Umeå Comprehensive Cancer Consortium), Clinical Pathology and Clinical Genetics (Uppsala University Hospital), and Nordic Society of Paediatric Haematology and Oncology (NOPHO) for providing patient specimens; and the SNP&SEQ Technology Platform in Uppsala, part of the National Genomics Infrastructure (NGI) Sweden and Science for Life Laboratory for WGS.

This work was supported by grants from the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation (KAW 2013-0159), The Swedish Research Council (2013-03486), The Swedish Childhood Cancer Foundation (PR2013-0070 and TJ2013-0045), The Swedish Cancer Society (CAN2013/489), and The Kjell and Märta Beijer Foundation (L.H.); by a grant from the Polish National Science Centre (DEC-2015/16/W/NZ2/00314); and by the eSSence program (J.K.) and Uppsala University (K.S.). The SNP&SEQ Platform is supported by the Swedish Research Council and the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation. WES was performed at the Uppsala Genome Center, part of NGI Sweden, which is supported by the Swedish Council for Research Infrastructures and Uppsala University and is hosted by Science for Life Laboratory. The computations were performed on resources provided by the Swedish National Infrastructure for Computing (SNIC) through the Uppsala Multidisciplinary Center for Advanced Computational Science (UPPMAX), partially funded by the Swedish Research Council through grant 2018-05973, under Project SNIC sens2017148 and sens2018102. Computational assistance was provided by Science for Life Laboratory (SciLifeLab)-Wallenberg Advanced Bioinformatics Infrastructure (WABI) Bioinformatics at Uppsala University.

Authorship

Contribution: S.S. performed experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper; S.A.Y. performed statistical analyses and analyzed the data; M.M., N.N., A.S., and J.S analyzed the next-generation sequencing data; K.S. performed the funMotif analysis; J.K. contributed the funMotif analysis method and supervised the funMotif analysis; M.K.H., C.S., A.E., M.H., J.P., J.A., K.J., M.C.M-K., B.Z., K.P.T., and L.C. contributed clinical samples and/or data; L.H. designed the study, performed the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper; and all authors read and contributed to the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Linda Holmfeldt, Rudbeck Laboratory, Department of Immunology, Genetics and Pathology, Uppsala University, SE-751 85 Uppsala, Sweden; e-mail: linda.holmfeldt@igp.uu.se.

References

Author notes

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.