Comment on Zhang et al, page 73

An elegant genetic study clarifies the role of the erythropoietin receptor in the pathogenesis of erythroblastosis and polycythemia induced by Friend virus.

In 1957, Charlotte Friend described erythroleukemia in mice that was transmissible by a cell-free filtrate.1 The retrovirus and disease that bear her name have proven to be a powerful model system for studying erythropoiesis, erythropoietin signaling, leukemogenesis, and retroviral pathogenesis.2 Friend virus, a complex of replication-competent helper virus and replication-defective spleen focus-forming virus (SFFV), induces disease in susceptible mice in 2 distinct stages. The initial premalignant phase is characterized by splenomegaly due to polyclonal expansion of nontransformed erythroblasts. Two different variants of SFFV (SFFVP and SFFVA) cause either polycythemia or anemia, respectively, during this period. Subsequently, clonal erythroleukemia emerges with loss of p53 and frequent activation of the Ets family transcription factor PU.1 through proviral insertion. The genetic basis of the first stage of Friend disease was clarified by 2 important observations. The first was the discovery by Li, D'Andrea, and coworkers3 that the envelope glycoprotein of SFFVP, gp55P, interacted with and activated the erythropoietin receptor (EpoR). The related envelope protein from SFFVA does not activate EpoR, although both forms of SFFV can induce erythroid burst-forming units (BFU-Es) in the absence of Epo. The second finding was the positional cloning by Ney and Correll's group of the Friend disease susceptibility locus Fv2,a mouse gene that encodes a naturally occurring truncated form of the receptor tyrosine kinase STK (sf-STK).4 Mice lacking sf-STK do not develop either erythroblastosis or erythroleukemia after Friend virus infection.

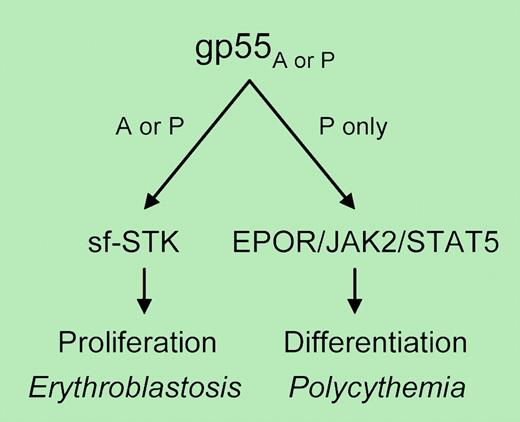

How these 3 transmembrane proteins might function in erythroid progenitors is a mystery. In one model, gp55 mediates a functional interaction between EpoR and sf-STK, analogous to that demonstrated for EpoR and another receptor tyrosine kinase, c-Kit.5 In the current issue of Blood, however, Zhang and colleagues use a genetic approach to demonstrate that gp55 must interact separately with Epo-R and sf-STK. Balb/c mice (sensitive, expressing sf-STK) engineered to express a murine EpoR mutant lacking cytoplasmic tyrosines required for Stat5 activation were nonetheless susceptible to Friend virus-induced erythroblastosis and splenomegaly, as were mice lacking both Stat5a and 5b. Friend virus induced small splenic foci of erythroblasts but not overt erythroblastosis after infection of Balb/c fetal liver cells lacking EpoR, whereas erythroblastosis and splenomegaly were restored by transgenic expression of human EpoR, which is not activated by gp55, at least in cell lines.6 By contrast, polycythemia induced by SFFVP did require EpoR and Stat5. These studies, together with recent observations that gp55 can also bind and activate sf-STK,7 suggest a model where gp55 from either SFFV strain can activate sf-STK and induce erythroblastosis, whereas gp55P causes Epo-independent terminal erythroid differentiation and polycythemia through EpoR and Stat5 (see figure). These results do not exclude possible indirect interactions between sf-STK and EpoR (for example, through JAK2). The reported resistance of human EpoR to activation by gp55P also deserves a second look, particularly in primary cells. Surprises will no doubt continue to emerge from the rich pathobiology of Friend virus. ▪

Model of erythroblastosis and polycythemia induced by Friend virus. The envelope glycoprotein (gp55) of both the anemia (A)- and polycythemia (P)-inducing strains of SFFV induces erythroblastosis and splenomegaly that requires sf-STK. Only gp55P induces Epo-independent terminal erythroid differentiation, through EpoR and Stat5. For details, see the complete figure in the article beginning on page 73.

Model of erythroblastosis and polycythemia induced by Friend virus. The envelope glycoprotein (gp55) of both the anemia (A)- and polycythemia (P)-inducing strains of SFFV induces erythroblastosis and splenomegaly that requires sf-STK. Only gp55P induces Epo-independent terminal erythroid differentiation, through EpoR and Stat5. For details, see the complete figure in the article beginning on page 73.