Abstract

PR1 (VLQELNVTV) is a human leukocyte antigen-A2 (HLA-A2)–restricted leukemia-associated peptide from proteinase 3 (P3) and neutrophil elastase (NE) that is recognized by PR1-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes that contribute to cytogenetic remission of acute myeloid leukemia (AML). We report a novel T-cell receptor (TCR)–like immunoglobulin G2a (IgG2a) antibody (8F4) with high specific binding affinity (dissociation constant [KD] = 9.9nM) for a combined epitope of the PR1/HLA-A2 complex. Flow cytometry and confocal microscopy of 8F4-labeled cells showed significantly higher PR1/HLA-A2 expression on AML blasts compared with normal leukocytes (P = .046). 8F4 mediated complement-dependent cytolysis of AML blasts and Lin−CD34+CD38− leukemia stem cells (LSCs) but not normal leukocytes (P < .005). Although PR1 expression was similar on LSCs and hematopoietic stem cells, 8F4 inhibited AML progenitor cell growth, but not normal colony-forming units from healthy donors (P < .05). This study shows that 8F4, a novel TCR-like antibody, binds to a conformational epitope of the PR1/HLA-A2 complex on the cell surface and mediates specific lysis of AML, including LSCs. Therefore, this antibody warrants further study as a novel approach to targeting leukemia-initiating cells in patients with AML.

Introduction

CD8 T cells specific for the human leukocyte antigen-A2 (HLA-A2)–restricted peptides WT1 and PR1, which are derived from the endogenous leukemia-associated antigens Wilms' tumor antigen1-3 and proteinase 3 (P3), respectively, mediate cytotoxicity against acute myeloid leukemia (AML). PR1-specific T cells also contribute to cytogenetic remission of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) in patients treated with interferon,4,5 and vaccination with WT1 and PR16,7 can induce specific CD8 immunity in patients with myeloid malignancies. These results validate endogenous self-peptides as targets for immunotherapy, including vaccination, adoptive cell therapy, or antibodies that bind peptide/MHC. Such T-cell receptor (TCR)–like monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) may have selective activity against leukemia if target peptide/MHC complexes are aberrantly expressed on leukemia. Furthermore, mAbs are easy to administer and can be dosed frequently, which may increase their effectiveness against high leukemia burdens.

Eliciting TCR-like mAbs has been technically challenging,8 primarily because of the high immunogenicity of HLA molecules in mice. Phage-display libraries,9 peptide/MHC immunization,10,11 and the combination of both strategies8,12 have been used to produce TCR-like mAbs targeting peptides derived from solid-tumor antigens (eg, MAGE, β-HCG, TARP, and NY-ESO-1) in the context of HLA-A1 or HLA-A2.9-11,13,14 Although antibody activity against primary tumors has not been well studied, complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC) against tumor cell lines has been reported.11 Some toxin-conjugated antibodies also show activity against tumor cells.14-16 However, to eradicate cancer, these antibodies must be active against cancer-initiating cells, and TCR-like mAb–induced cytolysis of cancer stem cells has not been reported. Nevertheless, because PR1-specific CTLs suppress leukemia progenitor cells in vitro17 and because Lin−CD34+CD38− cells are enriched for leukemia stem cells (LSCs)18 and can be easily studied, we hypothesized that if an anti–PR1/HLA-A2 antibody could be produced, it may be active against blasts and LSCs from HLA-A2+ AML patients.

We report the discovery of 8F4, a novel mAb that binds with high affinity to a conformational epitope of PR1/HLA-A2 and induces dose-dependent cytolysis of myeloid leukemia cells but not normal hematopoietic cells. 8F4 mediates CDC against Lin−CD34+CD38− LSCs and preferentially inhibits the growth of leukemia progenitor cells. These results justify further study of TCR-like antibodies to verify the differential effects against normal stem cells and LSCs. Biologically significant differences may justify further study of a humanized form of 8F4 as a novel treatment for leukemia.

Methods

Patients and donors

Samples were collected after informed written consent was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki under protocols approved by The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC) institutional review board. Cord blood from units rejected for clinical use because of low cell numbers was used. Mononuclear cells were separated by gradient density centrifugation, frozen, and preserved in liquid nitrogen.19 Cells were thawed, washed, and recovered by overnight incubation in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (complete medium; Sigma-Aldrich).

Generation of mouse anti–PR1/HLA-A2 mAbs

PR1 (VLQELNVTV) was refolded with recombinant HLA-A2 and β2-microglobulin. Two 6-week-old mice were injected subcutaneously or intraperitoneally with a 300-μL suspension composed of 20 μg of purified PR1/HLA-A2 monomer mixed with either 12 μg of AbISCO-100 adjuvant (Isconova AB)20 or complete Freund adjuvant (Fisher Scientific) in the MDACC Monoclonal Antibody care facility. The mice were immunized at 2-week intervals for a total of 4 times by intraperitoneal injection of antigen plus adjuvant, followed by an intraperitoneal injection of antigen alone 3 days before harvest of splenocytes. Three days before the final boost, serum was tested for polyclonal immune response using ELISA. Clones (n = 950) were isolated by limiting dilution. After screening with parallel ELISA, selected clones were transferred to 24-well plates and grown in DMEM containing 4mM l-glutamine, 20% fetal bovine serum, and 10% hybridoma cloning factor (Fisher Scientific). Mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. Animal care and use was approved by the MDACC Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Cell cultures

T2 cells were purchased from ATCC and maintained in complete medium. For peptide loading, cells were washed twice and resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium at 106 cells/mL. After adding 20 μL of PR1 (1-50μg) or control peptides, cells were incubated for 4 hours at 37°C, washed with PBS, and used for flow cytometry or cellular assays.

ELISA and surface plasmon resonance

The HLA-A2–restricted peptides PR1, WT1126 (RMFPNAPYL), cytomegalovirus-derived pp65 (NLVPMVATV), and influenza matrix protein–derived Flu (GILGFVFTL) were synthesized at the MDACC facility to a minimum 95% purity. MHC-peptide monomers were synthesized as described previously.21 PR1 analogs with Ala substitutions (ALA1-ALA9), minor histocompatibility antigen peptide HA-2 (YIGEVLVSV), and corresponding monomers were provided by M. G. D. Kester and Dr J. H. F. Falkenburg (Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, The Netherlands). For hybridoma screening, 96-well Maxisorb Immunoplates (Nunc) were coated with recombinant streptavidin (1 μg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich), blocked with blocking buffer (BB) containing 2% BSA in PBS, and incubated with biotinylated complex peptide/HLA-A2 in BB. After washing, plates were incubated with supernatant or antibody for 1 hour at room temperature. Bound antibodies were detected by incubation with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated goat anti–mouse antibodies (1:4000; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories), following by 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine substrate (Becton Dickinson). Supernatant from the BB7.2 hybridoma was used as a positive control. Parallel ELISAs with PR1 and pp65 were used to increase the PR1 specificity of screening. Clones with > 50% higher signal with PR1/HLA-A2 compared with pp65/HLA-A2 were further investigated. For 8F4-specificity assays, plates were coated with control antigens and then processed, as described in this paragraph.

Kinetics and affinities of the PR1/HLA-A2 binding to 3 antibodies (8F4, control BB7.2, and anti–keyhole limpet hemocyanin [KLH] immunoglobulin G2a [IgG2a]) was measured by surface plasmon resonance using a Biacore 3000 at the Center for Biomolecular Interaction Analysis (University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT). Binding studies were performed at 25°C using a running buffer containing PBS, 0.005% Tween-20, and 0.1 mg/mL of BSA (pH 7.4). Antibodies were captured on anti–mouse surfaces at densities of 95-240 RU (response units). The PR1/HLA-A2 analyte was diluted to 100nM and tested in duplicate in a 3-fold dilution series for binding to the antibody surfaces.

Flow cytometry and confocal imaging

8F4 mAb was affinity purified from hybridoma supernatant using protein A Sepharose and conjugated to the fluorochromes Alexa Fluor 488, Alexa Fluor 647, and PE (Invitrogen). Cells were costained with 8F4 and anti–HLA-A2 mAb BB7.2 to confirm colocalization. Flow cytometry data were collected with a FACSCantoII (Becton Dickinson), a CyAn ADP (Cytomation), and a Cytek-modified 5-color FACScan (Becton Dickinson) in the MDACC-SC FACS core facility and analyzed with FlowJo V.9.1 software (TreeStar). For confocal imaging, cells were fixed and stained with Alexa Fluor 647-8F4 and Alexa Fluor 488–BB7.2 (Serotec). ProLong Gold Antifade with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, dihydrochloride (DAPI; Invitrogen) was applied to the cells before mounting on glass slides. Imaging was performed using a Leica Microsystems SP2 SE confocal microscope at the MDACC confocal core facility.

Cytotoxicity assays

CDC and antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) were performed as described previously.22 For CDC, 2.5 μg of antibody and 106 target cells were mixed, 20 μL of ice-cold rabbit complement (Cedarlane Laboratories) was added, and the mixture was incubated at 37°C for 1 hour. For ADCC, PBMCs from normal donors were incubated with IL-2 (200 U/mL) for 5 days to generate effectors11 before the addition of T2 target cells with or without 8F4 for 16 hours at an effector-to-target cell ratio (E:T) of 40:1. Mouse anti–KLH IgG2a (R&D Systems) and BB7.2 were used as controls in cytotoxicity experiments.

Method A (Figure 3): Cytotoxicity was measured with the Cyto Tox-Glo Cytotoxicity Assay (Promega) based on cleavage of luminogenic substrate by proteases released by dead cells. Luminescence was measured with an FLX800 microplate fluorescence reader (BioTek Instruments) and KC Junior v.1.41.5.0 software (BioTek Instruments). Antibody-specific lysis was calculated as SL% = 100 × (Lcomplement + antibody − Lcomplement) / (Lmaximum − Lspontaneous), where Lspontaneous and Lmaximum are luminescence measured before and after the addition of the cytotoxic agent digitonin, respectively.

Method B (Figure 4): Subset-specific cytotoxicity was measured by calculating the absolute cell numbers in treated and untreated CDC samples by flow cytometry. After CDC, cells were stained with lineage Ab cocktail (CD3, CD4, CD8, CD19, CD20, CD14, and CD16), CD34, CD38, 8F4, and Live/DeadFixableAqua, washed, fixed, mixed with Caltag Counting Beads (Invitrogen), and analyzed by flow cytometry. Frequencies of gated Live/DeadFixableAqua− and Lin−CD34+CD38− events were used to calculate the absolute number (N) of live and stem cells, respectively, and specific lysis was calculated as SL% = 100 × (Nuntreated − Ntreated)/Nuntreated.

CFU assay

Viable nucleated cells at 2 × 105cells/mL in IMDM with 2% fetal bovine serum were incubated with PBS alone, 8F4, or isotype control antibody at 2.5 μg/mL for 30 minutes before plating in 35-mm wells with Methocult GF H4044 (StemCell Technologies) for 10-14 days. We measured CFUs of leukocytes (CFU-L), erythrocytes (CFU-E), granulocyte-macrophages (CFU-GM), granulocyte-erythroid-myeloid-megakaryocytes (CFU-GEMM), and erythrocyte blast-forming units (BFU-E) in triplicate cultures.

Statistical analysis

The unpaired t test was used to compare specific lysis in AML patients and normal donors. P< .05 was considered significant. Prism 5 for Mac OSX v.5d software (GraphPad) was used for data analysis.

Results

Immunization and antibody screening

We used 2 strategies to immunize Balb/c mice. In the first approach, PR1-pulsed, TAP-deficient T2 cells were injected into footpads, and then draining lymph nodes were collected and the B cells used to produce hybridomas with the P3X63 mouse myeloma fusion partner. Of 1600 hybridoma-derived clones screened by ELISA and flow cytometry, none showed specific binding to PR1/HLA-A2 (data not shown).

In the second approach, PR1 refolded with rHLA-A*0201 plus β2-microglobulin was injected every 2 weeks (n = 4 injections) with immunostimulating complexes and IFA. Sera were screened by ELISA and flow cytometry for polyclonal antibody expression. Hybridomas were produced from the spleens of animals with reactivity to PR1 in sera. A total of 2850 clones from 2 mice were tested by parallel screening for binding to PR1/HLA-A2 but not to pp65/HLA-A2, an irrelevant CMV control peptide.23,24 Clones that showed at least 2-fold higher ELISA signal with PR1/HLA-A2 compared with pp65/HLA-A2 were subcloned to test single-cell–derived colonies. Mice that received immunostimulating complexes yielded 10 clones that bound PR1/HLA-A2 but not pp65/HLA-A2 by ELISA. Antibody from only one clone was confirmed by flow cytometry to bind to T2 cells loaded with PR1, but not to T2 cells loaded with pp65 (data not shown). This clone was designated 8F4 and was identified with isotype-specific antibodies as an IgG2a antibody subclass by ELISA (data not shown)

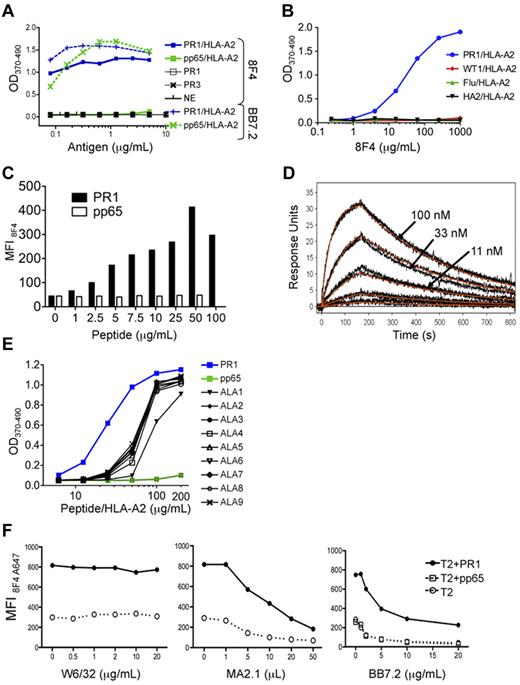

Specificity and affinity of 8F4 binding

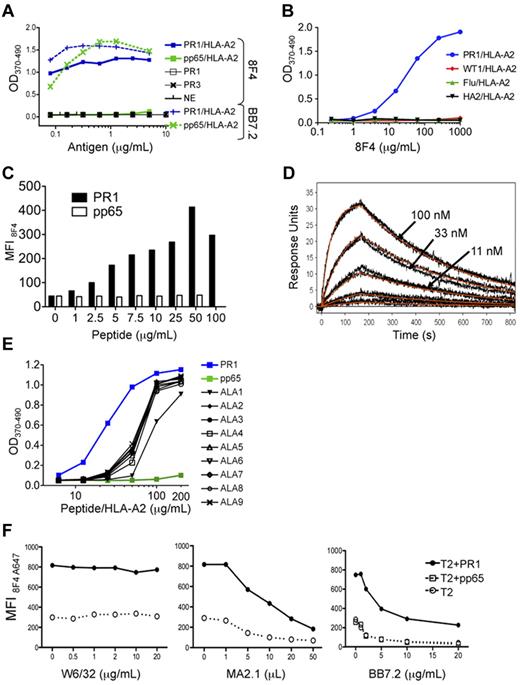

To confirm 8F4 specificity, we used an ELISA to show that 8F4 bound to the PR1/HLA-A2 monomer (Figure 1A-B), but not to monomers constructed with other peptides that bind tightly to HLA-A2, such as pp65/HLA-A2 (Figure 1A), WT1/HLA-A2, Flu/HLA-A2,25 and HA-2/HLA-A226 (Figure 1B). In contrast, the HLA-A2–specific control antibody BB7.2 bound to all HLA-A2 monomers (supplemental Figure 1A, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). Furthermore, 8F4 did not bind PR1 peptide alone, nor to neutrophil elastase (NE) or P3, the parent proteins of PR1 (Figure 1A). 8F4 binding was also dependent on the concentration of PR1/HLA-A2 and of 8F4 (Figure 1A-B). These data show that 8F4 binds with specificity to PR1/HLA-A2.

8F4 binding to PR1 in the peptide-binding cleft of HLA-A2. Binding was determined by ELISA (A, B, E), flow cytometry (C,F), and surface plasmon resonance (D). (A) 8F4 binding to PR1/HLA-A2 monomer in ELISA depends on PR1/HLA-A2 monomer concentration (blue squares). 8F4 does not bind to control pp65/HLA-A2 monomer, (green squares), PR1 peptide alone (open squares), P3 (black X), or NE (black vertical dashes). In contrast, the BB7.2 antibody, which binds to defined residues of the HLA-A0201 molecule but not to specific peptides within the peptide-binding cleft, binds to both PR1/HLA-A2 (blue vertical dashes) and pp65/HLA-A2 (green X marks). (B) 8F4 binding to PR1/HLA-A2 monomer (blue circles) depends on the 8F4 concentration. 8F4 does not bind to peptide/HLA-A2 monomers containing control peptides WT1 (RMFPNAPYL; red diamonds), Flu (GILGFVFTL; green triangles), or HA-2 (YIGEVLVSV; black triangles). (C) 8F4 binding is dependent on PR1 occupancy of cell-surface HLA-A2 molecules. T2 cells were loaded with increasing concentrations of PR1 (filled bars) or pp65 control peptide (empty bars). Peptide-loaded cells were labeled with 8F4 followed by FITC goat anti–mouse IgG secondary antibody, and fluorescence was measured with FACS. Bars show MFI. (D) Kinetics and affinity of 8F4 mAb binding to the PR1/HLA-A2 complex measured by SPR. PR1/HLA-A2 monomer binds to 8F4 captured on anti–mouse surfaces with a calculated KD = 9.9nM. Measured response units (black and orange lines) show results from a 1:1 interaction model that was used to calculate KD. (E) Sensitivity of 8F4 binding to PR1 and peptide analogs synthesized with Ala substitutions at P1-P9 (ALA1-ALA9). Peptide/HLA-A2 monomers were tested for binding to 8F4 with ELISA. ALA substitution at P1 (ALA1) abrogated 8F4 binding at 50 μg/mL. (F) Epitope mapping shows 8F4 binding to a helical domain of HLA-A2 molecules. T2 cells were loaded with 20 μg/mL of peptide (PR1 or control pp65 peptide) and incubated with A647-conjugated 8F4 in the presence of increasing concentrations of the HLA-A2–specific mAbs W6/32 (left), MA2.1 (center), and BB7.2 (right).

8F4 binding to PR1 in the peptide-binding cleft of HLA-A2. Binding was determined by ELISA (A, B, E), flow cytometry (C,F), and surface plasmon resonance (D). (A) 8F4 binding to PR1/HLA-A2 monomer in ELISA depends on PR1/HLA-A2 monomer concentration (blue squares). 8F4 does not bind to control pp65/HLA-A2 monomer, (green squares), PR1 peptide alone (open squares), P3 (black X), or NE (black vertical dashes). In contrast, the BB7.2 antibody, which binds to defined residues of the HLA-A0201 molecule but not to specific peptides within the peptide-binding cleft, binds to both PR1/HLA-A2 (blue vertical dashes) and pp65/HLA-A2 (green X marks). (B) 8F4 binding to PR1/HLA-A2 monomer (blue circles) depends on the 8F4 concentration. 8F4 does not bind to peptide/HLA-A2 monomers containing control peptides WT1 (RMFPNAPYL; red diamonds), Flu (GILGFVFTL; green triangles), or HA-2 (YIGEVLVSV; black triangles). (C) 8F4 binding is dependent on PR1 occupancy of cell-surface HLA-A2 molecules. T2 cells were loaded with increasing concentrations of PR1 (filled bars) or pp65 control peptide (empty bars). Peptide-loaded cells were labeled with 8F4 followed by FITC goat anti–mouse IgG secondary antibody, and fluorescence was measured with FACS. Bars show MFI. (D) Kinetics and affinity of 8F4 mAb binding to the PR1/HLA-A2 complex measured by SPR. PR1/HLA-A2 monomer binds to 8F4 captured on anti–mouse surfaces with a calculated KD = 9.9nM. Measured response units (black and orange lines) show results from a 1:1 interaction model that was used to calculate KD. (E) Sensitivity of 8F4 binding to PR1 and peptide analogs synthesized with Ala substitutions at P1-P9 (ALA1-ALA9). Peptide/HLA-A2 monomers were tested for binding to 8F4 with ELISA. ALA substitution at P1 (ALA1) abrogated 8F4 binding at 50 μg/mL. (F) Epitope mapping shows 8F4 binding to a helical domain of HLA-A2 molecules. T2 cells were loaded with 20 μg/mL of peptide (PR1 or control pp65 peptide) and incubated with A647-conjugated 8F4 in the presence of increasing concentrations of the HLA-A2–specific mAbs W6/32 (left), MA2.1 (center), and BB7.2 (right).

To determine whether 8F4 binds PR1/HLA-A2 on the cell surface, we used flow cytometry to study T2 cells loaded with PR1 or pp65.23 8F4 showed concentration-dependent binding to PR1-pulsed T2 cells but not to pp65-pulsed cells (Figure 1C), whereas BB7.2 antibody bound to T2 cells loaded with either peptide (data not shown), confirming that 8F4 binds cell-surface PR1/HLA-A2. The 8F4 antibody enabled a specific signal to be detected on T2 cells loaded with at least 1 mg/mL (0.99mM) of PR1. Based on the dissociation constant of PR1, we previously estimated that 1μM PR1 correlated with 10 000 complexes per T2 cell,23 which is similar to results obtained with a TCR-like mAb against MAGE3 peptide.10

We used surface plasmon resonance to measure 8F4-binding affinity. 8F4 bound with high affinity to soluble PR1/HLA-A2 monomer, largely because of its slow dissociation rate constant (Koff), with a dissociation constant (KD) = 9.9nM (Figure 1D), compared with KD = 162nM for BB7.2 anti–HLA-A2 antibody (data not shown). 8F4 affinity is high compared with other TCR-like mAb to peptides such as NY-ESO-1 (KD = 47nM)27 and gp100 (KD = 249nM),15 which may be an important determinant of antitumor function.

Epitope mapping was investigated with 2 methods. First, ELISA was used to measure 8F4 binding to various peptide/HLA-A2 monomers constructed with peptides modified with Ala substitutions at each position in PR1 (Figure 1E). Successful folding of the peptide/HLA-A2 monomers was verified by peptide binding to HLA-A219 and by recovery of purified monomer. The integrity of the peptide/HLA-A2 complex was confirmed by ELISA with BB7.2 (supplemental Figure 1B). Ala substitutions at P2-P9 of the PR1 reduced 8F4 binding to the peptide/HLA-A2 monomers equally compared with native PR1/HLA-A2 (Figure 1E). In contrast, an Ala substitution at P1 resulted in significant impairment of binding to 8F4, but not to BB7.2 (supplemental Figure 1B). Peptide binding to HLA-A2 did not correlate with 8F4 binding to the respective monomers. For example, ALA1-PR1 bound with higher affinity to HLA-A2 (EC50 = 1.45nM) compared with PR1 (EC50 = 1.8nM) and ALA9-PR1 (EC50 = 3.11nM; data not shown). Therefore, the data suggest that P1 of PR1 contributes to optimal 8F4 binding.

To study the contribution of HLA-A2 to 8F4 binding, mAbs that bound to HLA-A2 at defined epitopes were used to block 8F4 binding to PR1- and pp65-pulsed T2 cells. Binding of 8F4 to PR1-pulsed T2 cells was partially blocked by MA2.1 and BB7.2, but not by W6/32, suggesting that 8F4 contacts HLA-A2 residues that are common to MA2.1 and BB7.2 recognition (Figure 1F). Although this could have been due to simple physical hindrance, we hypothesized that a common region on HLA-A2 could connect these results, and this was easily tested. A common recognition region on HLA-A2 containing residues recognized by BB7.2 at position 169 and by MA2.1 at position 170 is near the terminal end of the α2 domain.28-30 The likelihood that these are contact residues for 8F4 binding is consistent with the importance of P1 of the peptide for optimal 8F4 binding, because the A pocket of HLA-A2, which accommodates P1, is bounded by amino acids 7, 59, and 159, and an adjacent residue at 171.31,32 In contrast, W6/32 binds a discontinuous epitope on the α2 domain of HLA-A2 and β2m and did not block 8F4 binding, consistent with 8F4 contact residues located near the α2 domain and the A pocket of the peptide-binding cleft.28 The PR1 peptide analog-binding data and anti–HLA-A2 antibody-binding data interpreted together show that 8F4 binds to a combined epitope of the PR1/HLA-A2 complex.

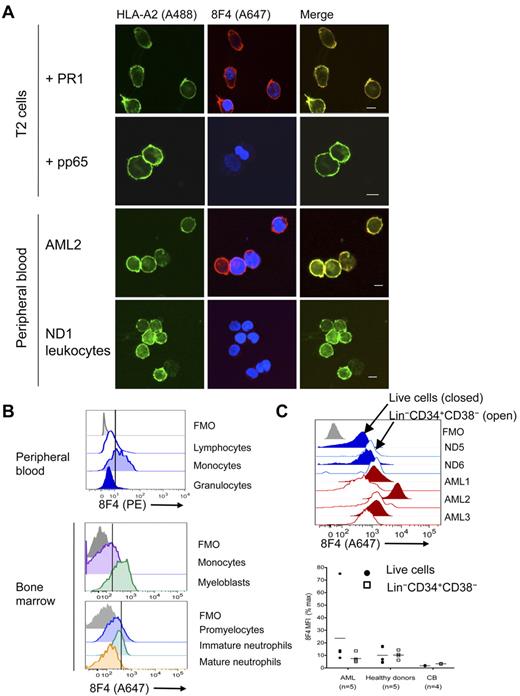

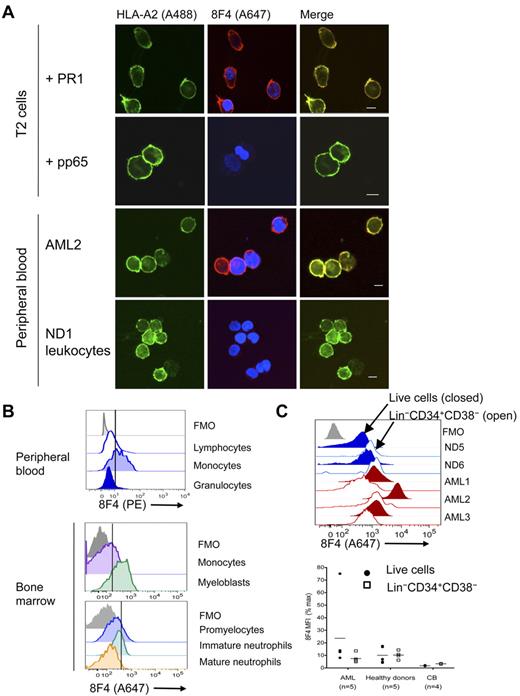

8F4 antibody identifies high expression of PR1/HLA-A2 on myeloid leukemia

Preferential lysis of myeloid leukemia over normal hematopoietic cells by PR1-CTL is correlated with the amount of intracellular P3.23 Furthermore, T2 cells loaded with a high concentration of PR1 and leukemia cells that overexpress P3 but not normal hematopoietic cells induce apoptosis of high-avidity PR1-CTLs.33 This suggests higher PR1 expression on leukemia compared with normal hematopoietic cells. We investigated this possibility using 2 methods. Immunofluorescent confocal imaging revealed colocalization of 8F4 and HLA-A2 on PR1-pulsed T2 cells (Figure 2A), but not on pp65-pulsed or nonpulsed T2 cells (data not shown). 8F4 and HLA-A2 colocalize on HLA-A2–transfected U937 leukemia cells (data not shown) that also express NE and P3.34 Next, we compared PR1/HLA-A2 expression on primary AML from patients with high circulating blasts against leukocytes from healthy donors (Table 1). 8F4 revealed bright surface expression of PR1/HLA-A2 on blasts from AML2, but only faint expression on normal leukocytes (Figure 2A). In addition, PR1/HLA-A2 expression was heterogeneous on blasts from different patients and on different blasts from the same patient (supplemental Figure 2A-D).

PR1/HLA-A2 visualization on normal and leukemia cells. Visualization was with fluorochrome-conjugated 8F4 in confocal microscopy (A) and flow cytometry (B-C). (A) From top to bottom: T2 cells loaded with PR1, T2 cells loaded with pp65, leukocytes from patient AML2, and leukocytes (PBMCs and granulocytes) from normal donor ND1. Cells were costained with Alexa Fluor 488 (A488)–conjugated anti–HLA-A2 (green; left panels) and Alexa Fluor 647 (A647)–conjugated 8F4 (red) and DAPI (blue; middle panels). Images were viewed with a Leica Microsystems SP2 SE confocal microscope with 10×/25 air, 63×/1.4 oil objectives and Leica Type F immersion oil. Leica LCS software (Version 2.61) was used for image analysis. Scale bar on merged images = 10 μm. (B) PR1 peptide is presented on HLA-A2+ PBMCs from normal donor ND2. Fresh peripheral blood was purified from red cells by lysis, stained with PE-conjugated 8F4 and the phenotype markers CD14, CD3, CD19, CD16, and Live/Dead Aqua viability indicator, and analyzed by flow cytometry (top panel). Scatter profiles and lineage markers identified the indicated cell types. CD14+ monocytes from HLA-A2+ NDs consistently expressed more PR1/HLA-A2 than lymphocytes and granulocytes. Healthy donor ND10 bone marrow cells were labeled with Live/Dead Fixable Aqua, 8F4, HLA-A2, CD34, CD33, CD13, CD14, and a lineage “dump” cocktail composed of Pacific Blue–conjugated CD3, CD7, CD10, CD19, and CD20 (middle panel). Myeloblasts were identified as viable Lin−CD33+CD34+; monocytes were CD14+. Healthy donor ND10 bone marrow cells were labeled with CD45, CD33, CD11b, CD16, and HLA-A2, and 8F4 (bottom panel). Granulocytes were identified based on scatter characteristics and then examined for expression of CD11b and CD16. Promyelocytes were identified as CD11blo/CD16lo; immature granulocytes were CD11bhi/CD16lo; mature granulocytes stained brightly for both markers CD11b and CD16. (C) Histograms show representative labeling of AML samples (red) and fresh bone marrow cells (blue) with 8F4, mAb directed to lineage markers (the Lin cocktail was CD3, CD4, CD7, CD8, CD10, CD14, CD16, CD19, and CD20, all in Pacific Blue or V450 conjugates), CD38, CD34, and Live/Dead Fixable Aqua (Invitrogen; top panel). For each sample, filled histograms show live cells, and open histograms show Lin−CD34+CD38− stem cells. Normal Lin−CD34+CD38− cells show slightly higher 8F4 MFI than total Lin− cells; in contrast, LSCs show lower PR1 expression compared with total blasts. Bottom panel combines 8F4 data from 3 different experiments. Each point represents one patient and is the mean value from 1 to 3 independent experiments. MFI for each sample was normalized and presented as a percentage of the MFI of the positive peak of Simply Cellular compensation beads labeled with 8F4. (B-C) The vertical line through the histograms represents background fluorescence established in the fluorescence-minus-one (FMO; gray) labeling control.

PR1/HLA-A2 visualization on normal and leukemia cells. Visualization was with fluorochrome-conjugated 8F4 in confocal microscopy (A) and flow cytometry (B-C). (A) From top to bottom: T2 cells loaded with PR1, T2 cells loaded with pp65, leukocytes from patient AML2, and leukocytes (PBMCs and granulocytes) from normal donor ND1. Cells were costained with Alexa Fluor 488 (A488)–conjugated anti–HLA-A2 (green; left panels) and Alexa Fluor 647 (A647)–conjugated 8F4 (red) and DAPI (blue; middle panels). Images were viewed with a Leica Microsystems SP2 SE confocal microscope with 10×/25 air, 63×/1.4 oil objectives and Leica Type F immersion oil. Leica LCS software (Version 2.61) was used for image analysis. Scale bar on merged images = 10 μm. (B) PR1 peptide is presented on HLA-A2+ PBMCs from normal donor ND2. Fresh peripheral blood was purified from red cells by lysis, stained with PE-conjugated 8F4 and the phenotype markers CD14, CD3, CD19, CD16, and Live/Dead Aqua viability indicator, and analyzed by flow cytometry (top panel). Scatter profiles and lineage markers identified the indicated cell types. CD14+ monocytes from HLA-A2+ NDs consistently expressed more PR1/HLA-A2 than lymphocytes and granulocytes. Healthy donor ND10 bone marrow cells were labeled with Live/Dead Fixable Aqua, 8F4, HLA-A2, CD34, CD33, CD13, CD14, and a lineage “dump” cocktail composed of Pacific Blue–conjugated CD3, CD7, CD10, CD19, and CD20 (middle panel). Myeloblasts were identified as viable Lin−CD33+CD34+; monocytes were CD14+. Healthy donor ND10 bone marrow cells were labeled with CD45, CD33, CD11b, CD16, and HLA-A2, and 8F4 (bottom panel). Granulocytes were identified based on scatter characteristics and then examined for expression of CD11b and CD16. Promyelocytes were identified as CD11blo/CD16lo; immature granulocytes were CD11bhi/CD16lo; mature granulocytes stained brightly for both markers CD11b and CD16. (C) Histograms show representative labeling of AML samples (red) and fresh bone marrow cells (blue) with 8F4, mAb directed to lineage markers (the Lin cocktail was CD3, CD4, CD7, CD8, CD10, CD14, CD16, CD19, and CD20, all in Pacific Blue or V450 conjugates), CD38, CD34, and Live/Dead Fixable Aqua (Invitrogen; top panel). For each sample, filled histograms show live cells, and open histograms show Lin−CD34+CD38− stem cells. Normal Lin−CD34+CD38− cells show slightly higher 8F4 MFI than total Lin− cells; in contrast, LSCs show lower PR1 expression compared with total blasts. Bottom panel combines 8F4 data from 3 different experiments. Each point represents one patient and is the mean value from 1 to 3 independent experiments. MFI for each sample was normalized and presented as a percentage of the MFI of the positive peak of Simply Cellular compensation beads labeled with 8F4. (B-C) The vertical line through the histograms represents background fluorescence established in the fluorescence-minus-one (FMO; gray) labeling control.

To quantify the amount of PR1/HLA-A2 expression, we used flow cytometry to measure 8F4 fluorescence on normal hematopoietic cells and on AML blasts (Table 1). PR1/HLA-A2 was expressed on normal peripheral blood monocytes but not on lymphocytes or mature granulocytes (Figure 2B). On bone marrow cells from healthy donors, P3, NE, and PR1/HLA-A2 were coexpressed on myeloblasts (Figure 2B and supplemental Figure 3A-B).35 Low PR1/HLA-A2 expression was also observed on promyelocytes but not on maturing granulocytes, including metamyelocytes and band forms, despite high expression of P3 and NE (Figure 2B and supplemental Figure 3). Because proteases are mostly localized in primary granules of mature granulocytes,36 which limits MHC-I processing, and because transcription of P3 and NE is down-regulated in pro-myelocytes,34,37 it is likely that MHC-I processing of newly synthesized P3 and NE proteins also decreases during maturation, preventing PR1 expression on mature granulocytes.38

8F4 fluorescence (mean fluorescence intensity [MFI] ± SEM) was higher on blasts from 5 AML patients (23.7 ± 5.18) compared with leukocytes from 3 healthy donors (13.6 ± 0.23; P = .046) and compared with blasts from an HLA-A2- patient, AML6 (4.0 ± 2.42; Figure 2C), although there was wide variability of expression on AML cells. Although 8F4 (PR1) expression was correlated with HLA-A2 expression on AML cells (P = .02), there was no difference in overall HLA-A2 expression between AML and healthy donor bone marrow cells (P = .07), suggesting that the fraction of HLA-A2 molecules bound to PR1 was higher in AML compared with normal bone marrow. Compared with T2 cells, the amount of 8F4 fluorescence suggested that the number of PR1/HLA-A2 complexes on the surface of AML was < 10 000, but precise measurements were not performed. PR1/HLA-A2 expression was more heterogeneous on AML blasts compared with normal leukocytes. Surprisingly, PR1/HLA-A2 expression was similar on the Lin−CD34+CD38− stem cell–containing population from AML patients and healthy donors (P = .8). Although PR1-CTLs preferentially lyse myeloid leukemia and suppress leukemia colony formation of CML bone marrow cells but not normal hematopoietic cells, differential lysis of Lin−CD34+CD38− cells by PR1-CTLs has not been directly studied. Similar PR1 expression on these cells suggests that PR1-CTLs may recognize PR1 on leukemia and normal stem cells, but differences related to PR1-CTL effector function or target cell susceptibility contribute to differences in outcome. In summary, these results confirm higher expression of PR1/HLA-A2 on AML blasts compared with normal myeloblasts, monocytes, and granulocytes, although PR1 expression was similar on stem cells from AML patients and healthy donors, including cord blood cells.

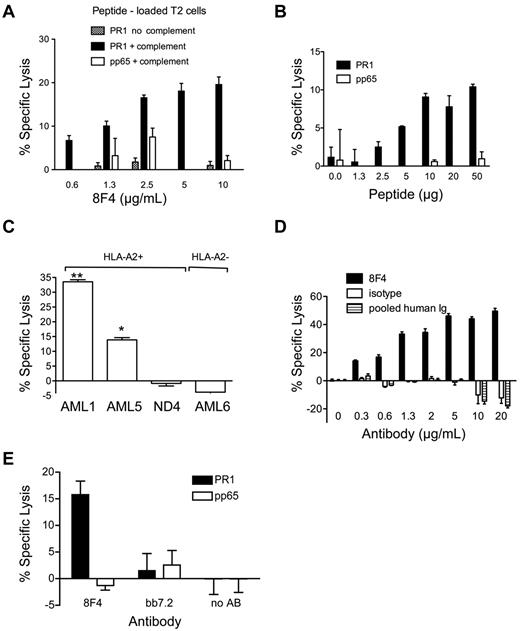

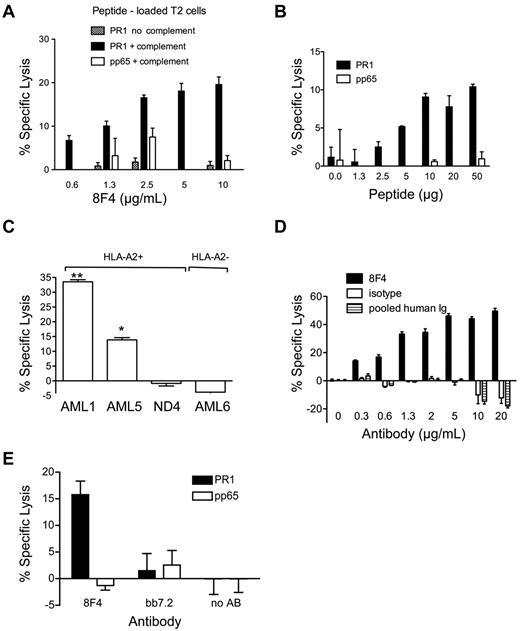

8F4 induces complement-dependent cytotoxicity against AML

Because PR1-CTLs induce cytolysis of leukemia,17,23 we sought to determine whether 8F4 similarly induced cytolysis of cells expressing PR1/HLA-A2. 8F4 induced dose-dependent lysis of T2 cells pulsed with PR1 but not pp65 control peptide (Figure 3A) in the presence of rabbit complement,11 demonstrating the CDC function of 8F4.

8F4 induces cytotoxicity in PR1-presenting cells. (A-D) For CDC,22 5 × 104 target cells (A-B: T2 cells loaded with PR1 or control peptide; C-D: primary AML or ND cells) in 10-RPMI/HEPES (N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid) were incubated with 8F4 or control antibody in the presence of complement at 37°C for 90 minutes. Cytotoxicity was assessed with the Cyto Tox-Glo Cytotoxicity Assay (Promega). (A) 8F4-mediated lysis of T2 cells is PR1 specific, requires the presence of complement, and depends on 8F4 antibody concentration. (B) At a constant 8F4 concentration (10 μg/mL), CDC depends on the PR1 concentration. T2 cells were loaded with increasing amounts of PR1 or pp65 control peptide. (C) 8F4 induces CDC of HLA-A2+ cells from AML1 and AML5, but not HLA-A2- cells from AML6 or PBMCs from an HLA-A2+ normal donor (ND4). *P = .0019 AML5 compared with ND4; **P < .0001 AML1 compared with ND4. (D) CDC of leukemia cells from AML1 depends on 8F4 concentration. Mouse IgG2a (isotype control) and pooled human intravenous immunoglobulin were compared at the same concentration as 8F4. (E) 8F4 induces lysis of PR1-loaded T2 cells by ADCC. Target T2 cells were loaded with PR1 or control peptide. Fresh PBMCs from a healthy donor were activated with IL-2 (200 IU/mL) for 2 days and used as effector cells at an E:T ratio of 40:1. Cells were mixed and incubated for 15 hours at 37°C with or without 8F4 or control antibody BB7.2 (50 μg/mL). (A-E) Specific lysis from representative experiments is shown as mean ± SEM from 3 replicates. The negative values for specific lysis are due to background luminescence of cells in the presence of complement likely caused by the enzymatic cleavage of substrate by complement in the absence of an antibody-coated target.11

8F4 induces cytotoxicity in PR1-presenting cells. (A-D) For CDC,22 5 × 104 target cells (A-B: T2 cells loaded with PR1 or control peptide; C-D: primary AML or ND cells) in 10-RPMI/HEPES (N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid) were incubated with 8F4 or control antibody in the presence of complement at 37°C for 90 minutes. Cytotoxicity was assessed with the Cyto Tox-Glo Cytotoxicity Assay (Promega). (A) 8F4-mediated lysis of T2 cells is PR1 specific, requires the presence of complement, and depends on 8F4 antibody concentration. (B) At a constant 8F4 concentration (10 μg/mL), CDC depends on the PR1 concentration. T2 cells were loaded with increasing amounts of PR1 or pp65 control peptide. (C) 8F4 induces CDC of HLA-A2+ cells from AML1 and AML5, but not HLA-A2- cells from AML6 or PBMCs from an HLA-A2+ normal donor (ND4). *P = .0019 AML5 compared with ND4; **P < .0001 AML1 compared with ND4. (D) CDC of leukemia cells from AML1 depends on 8F4 concentration. Mouse IgG2a (isotype control) and pooled human intravenous immunoglobulin were compared at the same concentration as 8F4. (E) 8F4 induces lysis of PR1-loaded T2 cells by ADCC. Target T2 cells were loaded with PR1 or control peptide. Fresh PBMCs from a healthy donor were activated with IL-2 (200 IU/mL) for 2 days and used as effector cells at an E:T ratio of 40:1. Cells were mixed and incubated for 15 hours at 37°C with or without 8F4 or control antibody BB7.2 (50 μg/mL). (A-E) Specific lysis from representative experiments is shown as mean ± SEM from 3 replicates. The negative values for specific lysis are due to background luminescence of cells in the presence of complement likely caused by the enzymatic cleavage of substrate by complement in the absence of an antibody-coated target.11

To test the dependence of CDC on the cell-surface peptide concentration, we added 10 μg/mL of 8F4 to T2 cells pulsed with increasing concentrations of PR1 or control pp65 peptide in the presence of complement. 8F4-mediated CDC was dependent on PR1 at concentrations between 1.3 and 10 μg/mL; no lysis of pp65-pulsed T2 cells was observed (Figure 3B). Because total HLA-A2 expression was equivalent on T2 cells pulsed with PR1 or pp65 peptide at 1.3-50 μg/mL, as measured with BB7.2 (data not shown), these results confirm that 8F4 induces specific CDC of cells that express the PR1/HLA-A2 complex.

Because PR1/HLA-A2 expression is higher on AML compared with normal hematopoietic cells, we sought to determine whether 8F4 mediated differential killing of AML versus normal leukocytes. 8F4 induced 33.5 ± 1.2% and 13.9 ± 1.3% CDC-mediated lysis, respectively, of PR1/HLA-A2–expressing blasts from AML1 and AML5 (Figure 3C), but no lysis of HLA-A2- blasts from patient AML6 or HLA-A2+ peripheral blood leukocytes (> 70% neutrophils) from a healthy donor, ND4 (P < .005). Furthermore, CDC lysis of AML was 8F4 concentration dependent, whereas no CDC lysis was observed with isotype control antibody (specific for KLH) or pooled human intravenous immunoglobulin (Figure 3D). Therefore, 8F4 at 0.3 mg/mL, a concentration achieved with therapeutic antibodies in clinical use,39,40 induces CDC of PR1/HLA-A2–expressing primary AML blasts but not healthy leukocytes.

We also investigated whether 8F4 induces ADCC, which is mediated by FcγR+ natural killer cells and other phagocytes. T2 cells pulsed with PR1 or control pp65 peptide were incubated with 8F4 or control antibody, and combined for 4-16 hours with PBMCs stimulated with IL-2.22 The observed ADCC killing was dependent on the E:T ratio, with maximum killing of 15.8 ± 2.0% at an E:T ratio of 40:1 (Figure 3E). Finally, we also looked for evidence of direct apoptosis. In the absence of complement or effector cells, escalating doses of 8F4 did not induce cytolysis or apoptosis of U937 cells or primary AML blasts, as measured by annexin V labeling (supplemental Figure 4). Therefore, 8F4 mediates modest ADCC (type II lysis) compared with CDC-mediated lysis of PR1/HLA-A2–expressing target cells.

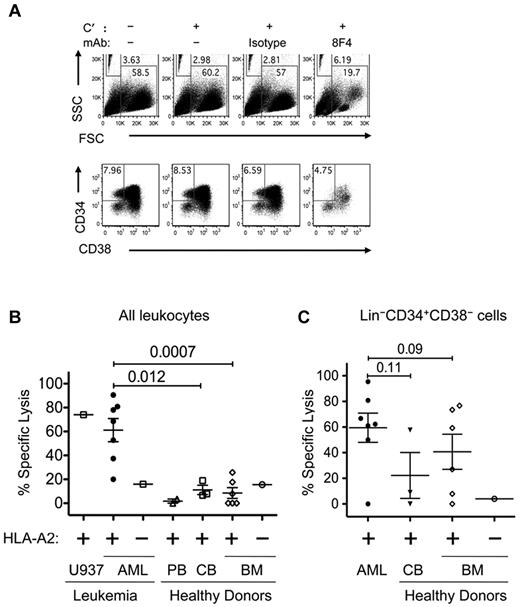

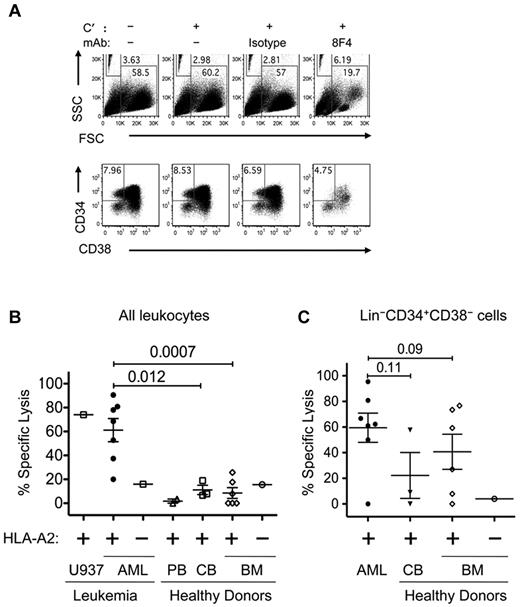

8F4 induces CDC-mediated lysis of AML blasts and LSCs

Leukemia is morphologically and phenotypically heterogeneous, and a cellular hierarchy can be observed that resembles normal ontogeny.41 According to the cancer stem–cell hypothesis, leukemia blasts are maintained by infrequent self-renewing LSCs that are resistant to conventional therapies.42 Consequently, effective treatment of AML must eliminate LSCs to result in a cure. Whereas there is controversy about whether LSCs have a unique phenotype that distinguishes them from normal hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), it has been shown that the Lin−CD34+CD38− population of hematopoietic cells is highly enriched for both types of stem cells.18 Because we found similar PR1/HLA-A2 expression on both types of stem cells, we sought to determine whether 8F4 was similarly active against both Lin−CD34+CD38− cells.

We used flow cytometry to study 8F4-induced CDC in HSC and LSC subpopulations. In this approach, microbeads were used to determine the absolute number of Lin−CD34+CD38− cells in samples after CDC (Figure 4A). In the presence of complement, 8F4 induced a 67% reduction of blasts from AML2, compared with 5.3% for isotype control (P < .005). Moreover, 8F4 induced 44% CDC-mediated lysis of Lin−CD34+CD38− LSCs compared with 23% lysis by the isotype control antibody (P = .01). This result shows that in addition to inducing cytolysis of the overall AML blast population, 8F4 also induces specific CDC-mediated lysis of LSCs. To examine the potential of 8F4 as an antileukemia agent, we compared the CDC effects of 8F4 against total cells, LSCs, and HSCs from HLA-A2+ AML patients (Table 1), healthy donors, cord blood cells, and HLA-A2–transfected U937 cells that express PR1, P3, and NE.34 The amount of lysis was determined by comparing the absolute number of treated total cells or stem cells to the number of untreated cells. To calculate 8F4-specific lysis, nonspecific lysis of isotype-treated cells was subtracted.

8F4 mediated CDC of both AML blasts and AML stem cells. AML or ND bone marrow cells were incubated with no rabbit complement (C′), C′ only, isotype control antibody, or 8F4 (2.5 μg/mL) for 1 hour at 37°C. Cells were then washed, labeled with lineage-specific mAbs (Lin cocktail was CD3, CD4, CD7, CD8, CD10, CD14, CD16, CD19, and CD20), CD38, CD34, and Live/Dead Fixable Aqua for 30 minutes on ice, and resuspended in 200 μL of 1% PFA in PBS. Before analysis, 50 μL of Caltag Counting Beads was added to each sample for single-platform determination of absolute cell numbers. (A) Representative flow cytometric plots showing scatter distribution and counting beads (top panels) and phenotypes (bottom panels) of AML2 from CDC assay. Beads (FSClo/SSChi gate) were counted, and debris was excluded using the FSChi/SSClo gate. Gates for viable and Lin− cells are not shown. LSCs were identified as viable Lin−CD34+CD38− cells, as shown in the bottom panels. The cytotoxicity of 8F4 increased the bead-to-cell ratio, and CD34+/CD38− LSCs constituted a reduced fraction of the few remaining viable cells in the 8F4-treated samples. (B) 8F4 mediates CDC of HLA-A2+ patient-derived AML blasts (●). Normal HLA-A2+ PBMCs (▵) and bone marrow cells (◊) were not affected (P = .0007). Leukemia cell line U937–transfected HLA-A2 was used as a positive control. Cells from an HLA-A2− AML patient (□) and bone marrow cells from an HLA-A2− normal donor (○) were used as negative controls. (C) Flow cytometric analysis of the same samples gated on live Lin−CD34+CD38− cells shows preferential CDC of LSCs. HSCs from 3 of 6 healthy donors are also affected by 8F4-mediated CDC. (B-C) CDC assay for each sample and enumeration of cell populations was performed as shown in panel A. For each sample, isotype-mediated background lysis was subtracted from the measured value. Each point is the calculated mean value from 1-3 independent experiments (based on available cells) from individual patients. Error bars show SEM for each group.

8F4 mediated CDC of both AML blasts and AML stem cells. AML or ND bone marrow cells were incubated with no rabbit complement (C′), C′ only, isotype control antibody, or 8F4 (2.5 μg/mL) for 1 hour at 37°C. Cells were then washed, labeled with lineage-specific mAbs (Lin cocktail was CD3, CD4, CD7, CD8, CD10, CD14, CD16, CD19, and CD20), CD38, CD34, and Live/Dead Fixable Aqua for 30 minutes on ice, and resuspended in 200 μL of 1% PFA in PBS. Before analysis, 50 μL of Caltag Counting Beads was added to each sample for single-platform determination of absolute cell numbers. (A) Representative flow cytometric plots showing scatter distribution and counting beads (top panels) and phenotypes (bottom panels) of AML2 from CDC assay. Beads (FSClo/SSChi gate) were counted, and debris was excluded using the FSChi/SSClo gate. Gates for viable and Lin− cells are not shown. LSCs were identified as viable Lin−CD34+CD38− cells, as shown in the bottom panels. The cytotoxicity of 8F4 increased the bead-to-cell ratio, and CD34+/CD38− LSCs constituted a reduced fraction of the few remaining viable cells in the 8F4-treated samples. (B) 8F4 mediates CDC of HLA-A2+ patient-derived AML blasts (●). Normal HLA-A2+ PBMCs (▵) and bone marrow cells (◊) were not affected (P = .0007). Leukemia cell line U937–transfected HLA-A2 was used as a positive control. Cells from an HLA-A2− AML patient (□) and bone marrow cells from an HLA-A2− normal donor (○) were used as negative controls. (C) Flow cytometric analysis of the same samples gated on live Lin−CD34+CD38− cells shows preferential CDC of LSCs. HSCs from 3 of 6 healthy donors are also affected by 8F4-mediated CDC. (B-C) CDC assay for each sample and enumeration of cell populations was performed as shown in panel A. For each sample, isotype-mediated background lysis was subtracted from the measured value. Each point is the calculated mean value from 1-3 independent experiments (based on available cells) from individual patients. Error bars show SEM for each group.

As shown in Figure 4B, 8F4 induced CDC-mediated specific lysis of blasts from 7 AML patients, but not bone marrow cells from 6 healthy donors (61.2 ± 10.0% vs 8.54.5%; P = .0007), which is consistent with results from the luminescence-based CDC assay in Figure 3. Furthermore, 8F4-induced CDC against AML blasts was directly correlated with PR1/HLA-A2 surface expression (R2 = 0.76; P = .05) as determined by 8F4 MFI in Figure 2C. Low-level CDC (< 20%) of both HLA-A2–positive and HLA-A2–negative bone marrow and peripheral blood cells from healthy donors and of HLA-A2–positive cord blood cells was observed with the bead-based flow cytometric assay, which showed little variation, suggestive of background lysis reflecting increased sensitivity of the assay.

We next compared the effect of 8F4 on Lin−CD34+CD38− stem cells (Figure 4C). 8F4 induced more CDC in LSCs from AML patients (n = 7; 59.5 ± 11.4%) compared with HSCs from healthy bone marrow (n = 6; 41.0 ± 13.7%; P = .09). 8F4 induced only background CDC (≤ 20%) against blasts and LSCs from patient AML8, indicating that not all HLA-A2+ AML cells are sensitive to 8F4. The modest difference of 8F4-mediated CDC of LSCs over HSCs compared with CDC of AML blasts over normal bone marrow cells may have been due to overlapping PR1 surface expression on LSCs and HSCs (Figure 2C) and heterogeneous PR1 expression on HSCs. However, the high background and high variability of the lysis measurements of HSCs in particular, likely because of the lower frequency of HSCs compared with LSCs in each sample, may obscure true differences of 8F4 lysis. Whereas HLA-A2 expression was 2-fold higher on HSCs compared with LSCs (MFI 3537 vs 1834; P = .02), there was no difference in overall PR1 expression (MFI 464 vs 335; P = .8). This is consistent with a higher fractional occupancy of HLA-A2 molecules by PR1 on LSCs, which may increase the efficiency of CDC lysis on LSCs, because higher ligand density amplifies complement activation by antibody cross-linking.43,44 Nevertheless, a more accurate determination of potential differences in activity may require a more precise method and increased sample sizes.

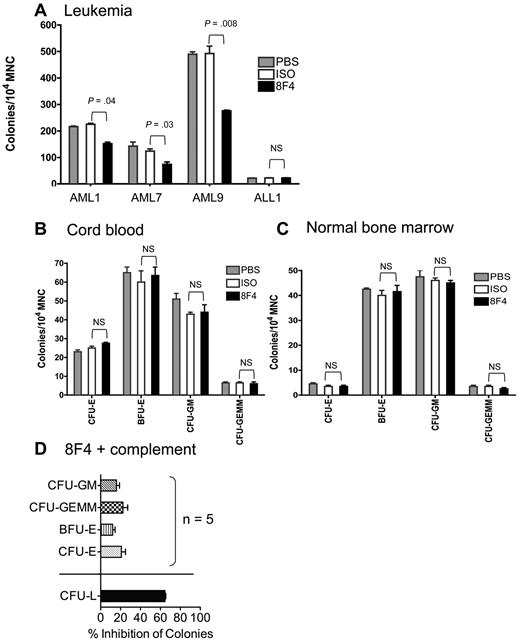

8F4 inhibits the growth of leukemia progenitor cells but not normal progenitor cells

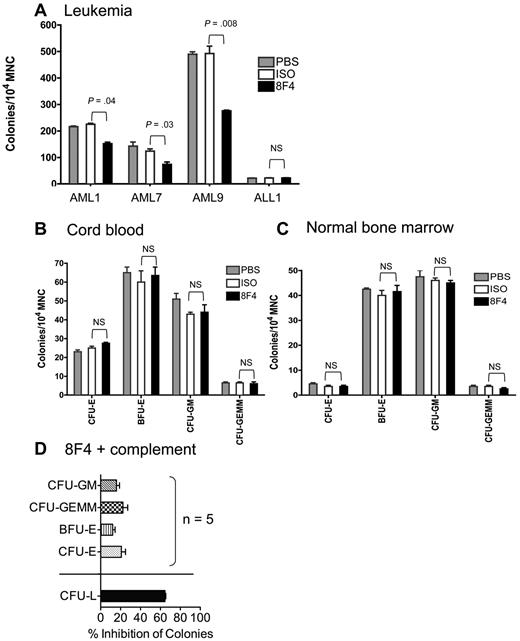

Because 8F4 shows lytic potential against LSCs and HSCs, we looked for differential activity against leukemia and normal progenitor cells with a more established assay. We measured CFU-GM, CFU-GEMM, CFU-E, and BFU-E from healthy donor bone marrow and cord blood and leukemia-forming units (LFUs) from AML patients who were treated with 8F4 or control antibody before plating in semisolid agar. Colonies per 105 mononuclear cells were counted 10-14 days later. 8F4 significantly inhibited leukemia progenitors from patients AML1 (P = .04), AML7 (P = .03), and AML9 (P = .008; Figure 5A), but not progenitors from a patient with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL1), which lacked expression of P3, NE, and PR1 (data not shown). There was no statistically significant effect of 8F4 against ALL1 despite low colony numbers. In contrast, 8F4 showed no inhibitory activity against progenitor cells from cord blood units or from normal bone marrow (Figure 5B-C). In the presence of complement, 8F4 inhibited LFUs from patient AML1 by 65%, compared with 20%-33% inhibition of normal progenitor cells (BFU-E and CFU-GEMM, respectively) from 5 healthy donors (P < .0001; Figure 5D). These results show that 8F4 preferentially inhibits leukemia progenitors over normal hematopoietic progenitors despite similar surface expression of PR1/HLA-A2 on Lin−CD34+CD38− progenitor cells. Furthermore, the leukemia-specific activity of 8F4 in the presence and absence of complement suggests an alternative mechanism of growth inhibition in addition to CDC.

8F4 inhibits CFU-L from AML patients, but does not inhibit CFU-L from ALL patients or CFU-E, BFU-E, CFU-GM, and CFU-GEMM from umbilical cord blood and normal bone marrow. (A) CFU-L inhibition by 8F4 from patients AML1, AML7, AML9 (see patient characteristics in Table 1). 8F4 inhibited day-10 CFU-L from AML1 (AML-M1) by 33% compared with the isotype control (P = .004). Similarly, 8F4 inhibited day 10 CFU-L from AML7 (AML-M7) by 44% (P = .03) and AML9 (AML-M1) by 41% (P = .008), respectively. 8F4 did not inhibit CFU-L from patient ALL1. (B) 8F4 had no effect on CFU-E, BFU-E, CFU-GM, or CFU-GEMM from HLA-A2+ umbilical cord blood units. The day-14 CFU-E count was not significantly different between 8F4- and isotype-treated mononuclear cells; results were similar for BFU-E, CFU-GM, and CFU-GEMM. A representative experiment of 3 performed with independent cord blood units is shown. (C) 8F4 had no effect on CFU-E, BFU-E, CFU-GM, or CFU-GEMM from fresh HLA-A2+ normal bone marrow. The day-14 CFU-E count was not significantly different between 8F4- and isotype-treated mononuclear cells; results were similar for BFU-E, CFU-GM, and CFU-GEMM. (A-C) Data represent mean colony counts ± SEM. (D) 8F4 inhibits CFU-L from AML1, but not normal progenitors from HLA-A2+ individual cord blood units (n = 5) in the presence of added rabbit complement. Data represent mean percent colony inhibition calculated for 5 individual cord blood units ± SEM. (A-D) Assays were performed in duplicate.

8F4 inhibits CFU-L from AML patients, but does not inhibit CFU-L from ALL patients or CFU-E, BFU-E, CFU-GM, and CFU-GEMM from umbilical cord blood and normal bone marrow. (A) CFU-L inhibition by 8F4 from patients AML1, AML7, AML9 (see patient characteristics in Table 1). 8F4 inhibited day-10 CFU-L from AML1 (AML-M1) by 33% compared with the isotype control (P = .004). Similarly, 8F4 inhibited day 10 CFU-L from AML7 (AML-M7) by 44% (P = .03) and AML9 (AML-M1) by 41% (P = .008), respectively. 8F4 did not inhibit CFU-L from patient ALL1. (B) 8F4 had no effect on CFU-E, BFU-E, CFU-GM, or CFU-GEMM from HLA-A2+ umbilical cord blood units. The day-14 CFU-E count was not significantly different between 8F4- and isotype-treated mononuclear cells; results were similar for BFU-E, CFU-GM, and CFU-GEMM. A representative experiment of 3 performed with independent cord blood units is shown. (C) 8F4 had no effect on CFU-E, BFU-E, CFU-GM, or CFU-GEMM from fresh HLA-A2+ normal bone marrow. The day-14 CFU-E count was not significantly different between 8F4- and isotype-treated mononuclear cells; results were similar for BFU-E, CFU-GM, and CFU-GEMM. (A-C) Data represent mean colony counts ± SEM. (D) 8F4 inhibits CFU-L from AML1, but not normal progenitors from HLA-A2+ individual cord blood units (n = 5) in the presence of added rabbit complement. Data represent mean percent colony inhibition calculated for 5 individual cord blood units ± SEM. (A-D) Assays were performed in duplicate.

Discussion

We report the discovery of 8F4, a novel TCR-like IgG2a that is the first mAb against an endogenous leukemia–associated antigen overexpressed on the cell surface of myeloid leukemia. We showed that 8F4 binds with high affinity (KD = 9.9nM) to a conformational epitope of PR1/HLA-A2, with contact residues near P1 of the PR1 peptide and the N-terminus of the α2-helical domain of HLA-A2. Confocal microscopy and flow cytometry experiments showed that PR1/HLA-A2 expression was high but heterogeneous on AML blasts compared with normal leukocytes, and low expression was observed on Lin−CD34+CD38− LSCs. Interestingly, low PR1/HLA-A2 expression was seen on HSCs and early myeloid progenitors including myeloblasts and promyelocytes, but not on differentiated myeloid cells or mature granulocytes. Although 8F4 showed weak ADCC, 8F4 mediated dose-dependent CDC against AML blasts that was correlated with PR1/HLA-A2 expression and CDC against LSCs, but not against normal leukocytes from bone marrow or cord blood. Although 8F4 mediated modest CDC against normal HSCs, CFU assays showed that 8F4 preferentially inhibited leukemia progenitor cells but not normal hematopoietic progenitor cells, despite similar PR1/HLA-A2 expression on LSCs and HSCs.

TCR-like mAbs have been produced against a range of tumor antigens, including HLA-A2- and HLA-A1–restricted peptides derived from NY-ESO-1,13 β-HCG,11 and MART-1.15 TCR-like mAbs show mostly CDC activity, although ADCC and direct type II cytotoxic apoptosis induction have also been observed.11 However, most studies with unconjugated, TCR-like mAbs show activity against tumor cell lines and against cell line–derived tumors in xenogeneic mouse models rather than against primary tumors.11,16 These and similar antibodies have been used to study MHC antigen presentation, to localize and quantify APCs displaying a T-cell epitope, to specifically mask an autoimmune T-cell epitope, and to induce lysis of epitope-expressing solid tumor cell lines in in vitro and in vivo models. TCR-like mAbs have been produced from conventional hybridoma approaches and from phage-display libraries. Those mAbs selected from Fab or scFv antibody phage-display libraries have relatively low affinities (50-250nM),14,15,27 and may potentially cross-react with other peptide/MHC complexes. In contrast, 8F4 was generated by direct immunization and as a result has a high affinity for PR1/HLA-A2 (KD = 10nM), similar to the binding affinity reported for Fab T1 (KD = 2-4nM), a TCR-like mAb that was selected by affinity maturation from a peptide-focused, second-generation Fab library,27 and is considered to have high binding affinity.

Whereas our study was not an exhaustive search for multiple epitope-specific antibodies, 78% of colonies recognized HLA-A2 after immunization and only a single anti–PR1/HLA-A2 antibody was isolated, which may reflect that only one such specificity exists or that other specificities were not generated during the murine immune response. Alternatively, weakly binding clones could have been lost during the selection procedure, resulting in the isolation of a single, strongly binding clone. TCR-like mAbs produced by xenogeneic immunization have also resulted in mAbs with potential cross-reactivity to other self-peptides. Therefore, whereas there was no evidence of cross-reactivity in our study, additional studies should explore potential cross-reactivity of 8F4. More patients must be studied to understand the range of PR1/HLA-A2 expression and the relationship of AML, CML, MDS, and LSCs to 8F4-mediated lysis. This study also suggests that TCR-like antibodies might be developed against other leukemia-associated and leukemia-specific peptide/HLA complexes to broaden the therapeutic potential of this approach.

Interestingly, 8F4-mediated CDC of leukemia blasts was correlated with PR1/HLA-A2 expression, but CDC of LSCs was only modestly higher than CDC of normal HSCs and was not correlated with PR1/HLA-A2 expression. There are many potential reasons that we did not observe a greater effect on LSCs versus HSCs. Because of the low frequency of LSCs and HSCs in all of the patient and donor samples, measurement errors of CDC lysis were amplified because of the low event rate. This reduces the precision of each measurement and decreases the ability to discern statistical differences between the LSC and HSC groups. This is supported by the larger SEM in lysis measurements on stem cells (Figure 4C) compared with the corresponding SEM of measurements on the more frequent blast and normal leukocyte populations (Figure 4B). Second, because PR1 expression was low on all stem cell populations, potential cross-reactivity of 8F4 may have resulted in some lysis of HSCs. Third, CDC is unlikely to be the only mechanism of 8F4 activity, as suggested by the preferential inhibition of leukemia progenitors by 8F4 in the absence of complement (Figure 5). For example, 8F4 may induce direct effects on cell growth or survival,44,45 and potentially significant differences of 8F4-induced apoptosis of LSCs and HSCs might not be evident because of the high nonspecific apoptosis of control-treated cells (supplemental Figure 4A-B). Fourth, the observed difference of CDC on LSCs and HSCs, while not statistically significant (P = .07), might still be biologically significant. For example, whereas the overall expression of PR1/HLA-A2 was similar on LSCs and normal myeloblasts, promyelocytes, and HSCs, a higher surface density of PR1/HLA-A2 complexes on LSCs would support more lysis because of amplified complement activation from antibody cross-linking.43 In addition, myeloid malignancies may be more susceptible to CDC because of variable expression of CD55 and CD59,46-48 which are critical proteins for preventing complement activation.

Specific lysis of myeloid leukemia by PR1-CTLs and specific inhibition of CML progenitor cells in standard CFU assays correlate with aberrant expression of P3 in target cells.17,23 However, high PR1 surface expression, likely the result of high intracellular P3, induces selective apoptosis of PR1-CTLs with high-avidity TCR, more potent effector cells compared with low-avidity PR1-CTLs, which are not killed by high PR1–expressing target cells.33 This implies that the relative high PR1 surface expression on leukemia causes deletion of PR1-CTL, which permits leukemia outgrowth. Conversely, a narrow range of low PR1 surface expression on HSCs and immature myeloid cells may function normally to permit the small number of PR1-CTLs to be maintained during T-cell homeostasis.49,50 Moreover, because low PR1 expression is similar on normal HSCs and LSCs, we speculate that this would allow LSCs, like HSCs under physiologic conditions, to escape immune recognition by low avidity PR1-CTLs because PR1 expression is insufficient to reach the activation threshold. Whereas high-avidity PR1-CTLs are more likely to recognize LSCs, they are much less frequent (1/800 000 CD8+ cells)19,33 and are therefore less likely to encounter low-frequency LSCs. In contrast, the higher PR1 expression on leukemia blasts compared with LSCs might be sufficient to cause recognition by low-avidity PR1-CTLs, although the latter are less-effective killers. 8F4 will be helpful in determining the role of PR1 expression on differential recognition of LSCs, blasts, and HSCs by high- and low-avidity PR1-CTLs.

Because 8F4 induced lysis of AML blasts and LSCs and inhibited leukemia progenitor cell growth, anti–PR1/HLA-A2 antibodies may have therapeutic potential. Because PR1 expression is similar on LSCs and HSCs, it will be important to further define potential on-target toxicity against HSCs, which could be studied in a xenogeneic mouse model. Nevertheless, because AML is often a fatal disease and 8F4 is highly active against blasts and LSCs, which are ordinarily resistant to cytotoxic agents, further study of 8F4 is justified.

An Inside Blood analysis of this article appears at the front of this issue.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

Presented in abstract form at the 51st annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, New Orleans, LA, December 6, 2009.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

HLA-A2–transduced U937 cells were kindly provided by T. Rodriguez Cruz and Dr G. Lizee (Department of Melanoma Medical Oncology, M. D. Anderson Cancer Center).

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (grants CA100632 and CA049639 to J.J.M. and M. D. Anderson Cancer Center support grant CA016672) and in part by the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society (grants Leuk6031-07 and 7262-08 to J.J.M.).

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: A.S. designed and performed experiments, analyzed and interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript; G.A. performed experiments, analyzed and interpreted data, and critically reviewed the manuscript; H.H. performed experiments and analyzed and interpreted data; K.R. performed FACS-based assays and sorting experiments; S.L. provided reagents and critically reviewed the manuscript; J.W. performed experiments and interpreted data; B.W.M. analyzed and interpreted data; Q.M. analyzed and interpreted data and critically reviewed the manuscript. D.L. analyzed and interpreted data; L.S. performed experiments and analyzed and interpreted data; K.C.-D. assisted with FACS-based assays and sorting, data analysis, and critical review of the manuscript; and J.J.M. designed experiments, interpreted data, wrote the manuscript, and supervised the work.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Jeffrey J. Molldrem, Section of Transplantation Immunology, Department of Stem Cell Transplantation & Cellular Therapy, The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center, 1515 Holcombe Blvd, Unit 900, Houston, TX 77030, e-mail: jmolldre@mdanderson.org.