Abstract

The NOTCH signaling pathway is implicated in a broad range of developmental processes, including cell fate decisions. However, the molecular basis for its role at the different steps of stem cell lineage commitment is unclear. We recently identified the NOTCH signaling pathway as a positive regulator of megakaryocyte lineage specification during hematopoiesis, but the developmental pathways that allow hematopoietic stem cell differentiation into the erythro-megakaryocytic lineages remain controversial. Here, we investigated the role of downstream mediators of NOTCH during megakaryopoiesis and report crosstalk between the NOTCH and PI3K/AKT pathways. We demonstrate the inhibitory role of phosphatase with tensin homolog and Forkhead Box class O factors on megakaryopoiesis in vivo. Finally, our data annotate developmental mechanisms in the hematopoietic system that enable a decision to be made either at the hematopoietic stem cell or the committed progenitor level to commit to the megakaryocyte lineage, supporting the existence of 2 distinct developmental pathways.

Introduction

Developmental pathways are generally viewed as a series of binary decisions with few opportunities for pleiotropy. However, this may limit adaptive decisions for development in adult tissues in response to environmental stressors.

In the hematopoietic hierarchy, the various lymphoid and myeloid blood cell lineages originate from HSCs through successive cell fate decisions.1,2 Purification of different progenitor populations that are based on multiple cellular markers and clonal analyses has yielded several potential models for hematopoietic development.3-7 In particular, the origin of megakaryocyte-erythrocyte progenitors (MEPs) is unclear. Several lines of evidence indicate that MEPs develop from committed myeloid progenitors,5,7,8 whereas others have suggested that MEPs may arise directly from HSCs before their commitment to lymphoid/myeloid lineages.3,4,6 Of note, a number of genes involved in megakaryocyte-erythrocyte development, including Runx1, Tal1, or c-Myb, also play important roles in HSC biology.9 The molecular basis for cell fate decisions made by HSCs for lineage commitment are not well understood. However, it is plausible that there are opportunities for MEP lineage commitment at more than 1 branch point in the hematopoietic developmental hierarchy. A precise understanding of the roadmap of hematopoietic development of MEPs may be of value both for the treatment of hematopoietic malignancies involving this lineage and in developing strategies to enhance regenerative platelet production.

The NOTCH signaling pathway is highly conserved among multicellular organisms and has been shown to participate in a broad range of developmental processes in part through the regulation of cell fate decisions.10 Several observations highlight the importance of tight regulation of NOTCH pathway activity during hematopoietic development. These include the causal role of Notch1-activating mutations in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL), and the specific association of infant acute megakaryoblastic leukemia with expression of the one twenty-two–megakaryoblastic acute leukemia fusion oncogene that aberrantly activates recombination signal-binding protein 1 for J-κ (RBPJ)–mediated transcription in hematopoietic progenitors.11,12 The role of the NOTCH signaling pathway during normal hematopoiesis has been extensively studied in the context of T-cell development. We recently demonstrated that the NOTCH pathway also specifies megakaryocyte development from hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells.13 In addition, in vitro stimulation of human cord blood CD34+ cells with the NOTCH ligand Delta-like1 (DL1) promoted the generation of precursors that repopulate the megakaryocytic lineage in vivo.14 However, little is known about the mediators of NOTCH signaling in target cells and how NOTCH stimulation might specify different cell fate decisions during HSC differentiation.

The phosphatidylinositol 3-OH kinase (PI3K) and the serine-threonine kinase AKT are key intermediates of a signaling pathway activated by several cell-extrinsic signals that are involved in cell growth and survival.15,16 Class IA PI3K proteins are composed of heterodimers of an adaptor/regulatory subunit (p85, p55, or p50) and a catalytic subunit (p110). On activation of growth factor receptors, PI3K interacts with phosphotyrosine residues on the receptor and phosphorylates phosphoinositides, leading to an increase in phosphatidylinositol-triphosphate levels. Phosphatidylinositol-triphosphate is a phospholipid that then serves as an anchor point for pleckstrin-homology domain–containing molecules, such as AKT. When recruited to the membrane, AKT undergoes a conformational change that allows its phosphorylation by 3-phosphoinositide-dependent kinases 1 and 2. Activated AKT, in turn, leads to phosphorylation of an array of cytoplasmic and nuclear signaling molecules, including S6 kinase, Forkhead Box class O (FOXO) family members, and mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1), that influence diverse biologic processes that include cell proliferation, survival, and metabolism, among others.15-18 The lipid phosphatase with tensin homolog (PTEN) is a negative regulator of the PI3K/AKT pathway and acts by inhibiting the activation of AKT.15,19-22 Of interest, the PI3K/AKT pathway has been shown to play a role downstream of MPL, the receptor for thrombopoietin, during megakaryopoiesis.23-25 In addition, several reports indicate that the NOTCH and PI3K signaling pathways interact at several levels and in various cellular contexts.26-34 During T-cell differentiation, as well as in mesothelioma cell survival, it has been proposed that activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway by NOTCH signaling is mediated by the down-regulation of PTEN.27

In this report, we investigated the molecular effectors of NOTCH signaling during megakaryopoiesis and observed that AKT signaling is activated during this process. Interestingly, the requirement for AKT-activated pathways downstream of NOTCH signaling depends on the population of hematopoietic progenitors from which megakaryocyte development is initiated. These data support the hypothesis that megakaryocyte development can occur at 2 distinct developmental branch points during hematopoiesis.

Methods

Coculture of sorted progenitors and stromal cells

OP9-GFP (green fluorescent protein) and OP9-DL1 stromal cells (a kind gift from Dr Carlos Zúñiga-Pflücker, University of Toronto) were cultured as described previously.13 For coculture, 1 × 103 to 2 × 104 sorted progenitors were plated onto the stromal cells in OP9 media, and one-half of the media was changed every 3 days. γ-Secretase activity was inhibited by adding 1μM γ-Secretase inhibitor [GSI; γ-Secretase inhibitor XXI: (S,S)-2-[2-(3,5-Difluorophenyl)-acetylamino]-N-(1-methyl-2-oxo-5-phenyl-2,3-dihydro-1H-benzo[e] [1,4]diazepin-3-yl)-propionamide; Calbiochem]. Mock-treated cultures were exposed to the same volume of vehicle only (DMSO). For analysis, hematopoietic cells were harvested from the supernatant of the cultures and filtered through a 70-μm cell strainer. For quantitative PCR analysis, cells harvested from the coculture were incubated for 1 hour in OP9-media on tissue culture–treated plates, and only supernatants were collected to remove any residual stromal cells before RNA extraction.

Flow cytometric analysis and cell sorting

Antibodies were obtained from BD PharMingen, and staining procedures were performed in PBS/2% FBS. Purification of Lineage−Sca1+cKit+ (LSK) and common myeloid progenitor (CMP) cells by flow cytometry was performed with the use of a FACSAria (BD Biosciences). Analyses were gated on forward/side scatter profile and CD45+ or CD45+GFP+ cells. All gates were set on cells stained with isotype controls. Data were analyzed with FlowJo (TreeStar). For phospho-flow analysis, BM harvested from transgenic NOTCH reporter (TNR) mice35 or murine stem cell virus–internal ribosomal entry site–green fluorescent protein (MIG)–intracellular NOTCH4 (ICN4) transplant recipients was sorted for lineage-negative propidium iodide–negative cells. These cells were then stained for p-AKT, p-RPS6 (ribosomal protein S6), and p-FOXO (Cell Signaling Technology).

RNA extraction and real-time RT-PCR

RNA was isolated with the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) and quantified by spectrophotometry (Beckman Coulter). The expression levels of Gata-1, Hes-1, Nrarp, and Pten were assessed by quantitative RT-PCR (EZ RT-PCR Core Reagents; Applied Biosystems), following the manufacturer's recommendations. Expression levels of Gata-1 (Mm00484678_m1 assay), Hes-1 (Mm00468601_m1 assay), Nrarp (Mm00482529_s1), and Pten (Mm00477210_m1) were normalized to Gapdh (4352932E).

Viral infection, BM transplantation, and polyinosine-polycytidylic acid injection

Viral supernatants were obtained from MSCV-DN-MAML1-GFP (kind gift from Dr James D. Griffin, Harvard University), MSCV-IRES-GFP, MIG-ICN4, MSCV-IRES-myrAKT, and MSCV-IRES-KD-AKT (kind gift of Dr David Fruman, University of California) constructs as described previously.12 Similar viral titers were used for each retroviral construct, and transduction efficiencies in primary cells were confirmed for the various constructs by flow cytometric analysis of GFP content. For transduction, 2 × 104 sorted LSK or CMP cells were directly spin-infected for 60 minutes at 2000 rpm with viral supernatant in IMDM containing 20% FBS, 20 ng/mL mIL-6 (R & D Systems), 10 ng/mL mSCF (PeproTech), 10 ng/mL mIL-11 (PeproTech), 5 μg/mL Polybrene (American Bioanalytical), and 7.5mM HEPES buffer (Gibco-Invitrogen). Cells were further incubated overnight in the same media and plated in OP9 media on stroma for 6 days before flow cytometric analysis. For BM transplantation, 8- to 10-week-old Rag1−/−C57BL/6 (The Jackson Laboratory) donor mice were injected with 5-fluorouracil (150 mg/kg) 5 days before BM collection from femurs and tibiae. After an overnight incubation in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS, 10 ng/mL mIL-3, 20 ng/mL mIL-6, and 10ng/mL mSCF, cells were spin-infected with either MSCV-IRES-GFP or MIG-ICN4 viral supernatants 2 times on days 1 and 2, and 1 × 106 were injected into the tail vein of lethally irradiated wild-type C57BL/6 recipient mice as described previously. Animals were analyzed 4 weeks after transplantation. Pten conditional knock-out mice (stock no. 004597; The Jackson Laboratory) or FoxO1/3/4 conditional knockout mice36 were crossed with Mx1-Cre transgenic animals (The Jackson Laboratory); cKO-Mx1-Cre+ and cKO-Mx1-Cre− progeny were induced at 6 weeks of age with 3 bi-daily intraperitoneal injections of polyinosine-polycytidylic acid ([poly(I:C)]; Amersham [GE]) and analyzed 2-3 weeks later. Approval for the use of animals in this study was granted by the Children's Hospital Boston and the Institut Gustave Roussy Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees.

In vitro cultures and colony-forming assays

For megakaryocyte colony assays, 2.2 × 105 BM or spleen cells were mixed with MegaCult-C supplemented with 50 ng/mL murine thrombopoietin, 50 ng/mL mIL-11, 10 ng/mL mIL-3, and 20 ng/mL mIL-6 (StemCell Technologies) and plated onto double-chamber culture slides in duplicates for 7 days, following the manufacturer's recommendations. Slides were stained for acetylcholinesterase, and colonies were enumerated as previously described.12 For methylcellulose colony-forming assays, 5 × 104 BM cells were mixed with M3434 media (StemCell Technologies) supplemented with 50 ng/mL murine thrombopoietin and plated onto 35-mm cell culture dishes. Colonies were scored 7 days later.

Staining, immunohistochemistry, and immunofluorescence

von Willebrand factor (VWF; DakoCytomation) Ab was used to perform immunohistochemistry on paraffin-embedded tissue sections at the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center Specialized Histopathology Services Core facility. Briefly, tissues were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin and infiltrated with paraffin on an automated processor (Leica). Tissue sections (4-μm thick) were placed on charged slides, deparaffinized in xylene, rehydrated through graded alcohol solutions, and stained with the anti-VWF Ab. Images were obtained at room temperature (22°C) using a Nikon Eclipse E400 microscope and a SPOT RT color digital camera (model 2.1.1; Diagnostic Instruments). The microscope was equipped with a 10×/22 NA ocular lens. Low-power images (magnification ×100) were obtained with a 10×/0.25 objective lens, intermediate-power images (magnification ×400 and ×600) with a 40×/1.3 NA and 60×/1.4 objective lenses with oil, high-power images (×1000) with a 100×/1.4 objective lens with oil (Trak 300; Richard Allan Scientific).

For immunofluorescence, CD41 was detected by 2-step immunofluorescence with the use of a rat anti–mouse CD41 Ab (BD Biosciences) followed by an anti–rat Ab Alexa 488–conjugated Ab (Invitrogen; dilution 1:750). GFP was detected by 3-step immunofluorescence with the use of a rabbit anti-GFP Ab (Abcam; dilution 1:100) followed by an anti–rabbit HRP-conjugated Ab (DAKO; dilution 1:750) followed by a Tyramide Alexa 488–conjugated Ab (Perkin Elmer; dilution 1:50). Briefly, unfixed non-decalcified frozen sections were thawed to room temperature for 30 minutes and rehydrated in PBS; nonspecific signal was blocked by incubation with PBS/10% FACS. All Abs and streptavidin were diluted in PBS/10% FACS. Primary Abs were incubated for 1 hour, secondary and tertiary Abs were incubated for 30 minutes. After Ab incubation, 3 washes were performed with PBS/0.1% Tween20. Nuclear counterstaining was obtained by incubating the sections with DAPI (1 μg/mL) in PBS for 10 minutes. Stained sections were mounted with Vectashield and observed with a Nikon Eclipse 80i epifluorescence microscope equipped with a Qimaging Micropublisher digital CCD color camera and iPLab (Biovision Technologies). All images were processed for size, contrast, and luminosity with Adobe Photoshop 6.0 (Adobe Systems).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

ChIP of wild-type, FoxO1/3/4cKO-Mx1Cre+, or FoxO3a-overexpressing Lin− BM cells was performed as described previously.37 Abs included anti-Histone H3 (Abcam), anti-FOXO1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and anti-FOXO3a (Cell Signaling Technology). Primer sequences for the Hes1 and Nrarp promoter region, as well as Hes1 3′-untranslated region are available on request.

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance of differences between the different conditions was assessed with a 2-tailed unpaired t test.

Results

NOTCH signaling correlates with activation of PI3K/AKT pathway during megakaryopoiesis

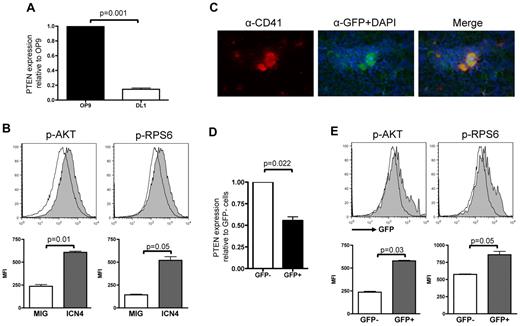

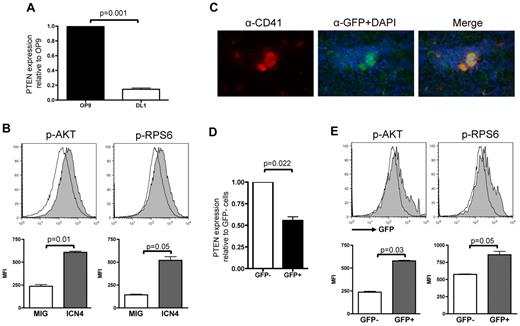

We first assessed whether NOTCH signaling activates the PI3K/AKT pathway during megakaryocyte differentiation through regulation of key components of the PI3K pathway. We audited Pten expression by quantitative RT-PCR analysis of RNA derived from flow-sorted hematopoietic wild-type LSK cells plated on stromal cells expressing the NOTCH ligand DL1 (OP9-DL1) in an in vitro megakaryocyte differentiation system.13 Compared with cells plated on OP9 control stroma for 3 days, cells stimulated with DL1 showed lower Pten expression (Figure 1A).

NOTCH activation correlates with Pten down-regulation and increased activation of PI3K/AKT pathway. (A) RNA from sorted wild-type LSK cells cocultured with OP9-GFP or OP9-DL1 for 3 days was used to perform analysis of Pten expression normalized to Gapdh and are shown relative to LSK cells grown on OP9-GFP. Mean ± SEM of triplicate experiments is represented. (B) Flow-sorted Lineage− cells infected with either MSCV-IRES-GFP or MIG-ICN4 were fixed/permeabilized and prepared for phospho-flow analyses. Histograms show a representative of 3 independent animals from each group, and bar graphs indicate mean ± SEM. (C) Immunofluorescence on fresh frozen TNR BM sections probed with an anti-CD41 and an anti-GFP Ab and counterstained with DAPI shows that megakaryocytes are GFP+. (D) RNA was extracted from flow-sorted Lineage−cKit+GFP− and Lineage−cKit+GFP+ cells of TNR animals, and quantitative RT-PCR analysis for PTEN expression was performed. Mean ± SEM of duplicate analysis is shown. (E) Flow-sorted Lineage− cKit+ cells from TNR animals were fixed/permeabilized and stained for phospho-AKT or phospho-RPS6. Phosphorylation levels in GFP+ (active NOTCH signaling) and GFP− (inactive NOTCH signaling) cells were assessed by flow cytometry. Histograms show a representative of 6 independent animals tested, and bar graphs indicate mean ± SEM.

NOTCH activation correlates with Pten down-regulation and increased activation of PI3K/AKT pathway. (A) RNA from sorted wild-type LSK cells cocultured with OP9-GFP or OP9-DL1 for 3 days was used to perform analysis of Pten expression normalized to Gapdh and are shown relative to LSK cells grown on OP9-GFP. Mean ± SEM of triplicate experiments is represented. (B) Flow-sorted Lineage− cells infected with either MSCV-IRES-GFP or MIG-ICN4 were fixed/permeabilized and prepared for phospho-flow analyses. Histograms show a representative of 3 independent animals from each group, and bar graphs indicate mean ± SEM. (C) Immunofluorescence on fresh frozen TNR BM sections probed with an anti-CD41 and an anti-GFP Ab and counterstained with DAPI shows that megakaryocytes are GFP+. (D) RNA was extracted from flow-sorted Lineage−cKit+GFP− and Lineage−cKit+GFP+ cells of TNR animals, and quantitative RT-PCR analysis for PTEN expression was performed. Mean ± SEM of duplicate analysis is shown. (E) Flow-sorted Lineage− cKit+ cells from TNR animals were fixed/permeabilized and stained for phospho-AKT or phospho-RPS6. Phosphorylation levels in GFP+ (active NOTCH signaling) and GFP− (inactive NOTCH signaling) cells were assessed by flow cytometry. Histograms show a representative of 6 independent animals tested, and bar graphs indicate mean ± SEM.

Next, we performed phosphoflow analyses of BM cells derived from animals transplanted with intracellular NOTCH ICN4-expressing cells that were previously shown to give rise to a higher number of megakaryocytes.13 To preclude confounding results because of development of T-ALL in this model, we used Rag1−/− donor BM cells.38,39 We observed that ICN4-expressing Lin−c-Kit+ cells exhibited increased levels of phosphorylation of both AKT and RPS6, a downstream target of AKT signaling, compared with control cells (Figure 1B and supplemental Figure 1A, respectively, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

To confirm these results in cells presenting physiologic activation of the NOTCH pathway, we used a TNR mouse35,40,41 in which expression of the GFP is controlled by binding of the RBPJ/ICN/Mastermind-like (MAML) transcription factor complex to RBPJ-binding elements (supplemental Figure 1B). In these transgenic animals, NOTCH pathway activation induces GFP expression. Megakaryocytes and megakaryocyte progenitors from TNR mice express GFP, as assessed by immunofluorescence, flow cytometric, and in vitro colony assays (Figure 1C; supplemental Figure 1). Expression analysis in flow-sorted Lin−c-Kit+ cells from TNR mice showed significantly lower PTEN expression in GFP+ than in GFP− cells (Figure 1D). In addition, phosphoflow cytometry analysis of Lin−c-Kit+ cells also showed a significantly higher level of phosphorylation of both AKT and RPS6 in GFP+ than in GFP− cells (Figure 1E). Taken together, these data indicate that NOTCH signaling activation correlates with low Pten expression and high levels of phosphorylation of several components of the PI3K/AKT pathway during megakaryocyte development.

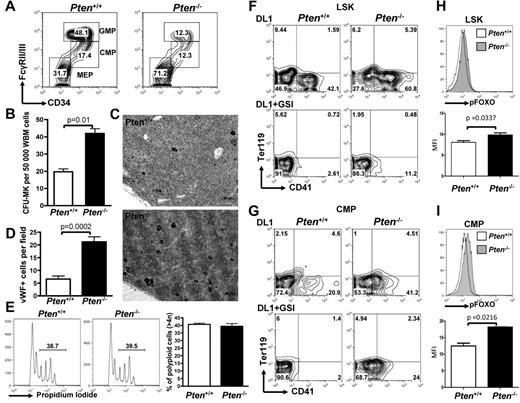

Pten inhibits megakaryocyte development in vivo and ex vivo

To understand the physiologic relevance of Pten down-regulation in megakaryocyte development, we used a system enabling conditional deletion of Pten in the hematopoietic system. Mice transgenic for the Mx1-Cre allele and homozygous for a conditional Pten loss of function allele (Mx1-Cre PtenFlox/Flox animals) were treated with poly-dI-poly-dC (pIpC) that results in Pten excision in the entire hematopoietic system (hereafter designated Pten−/−). For controls, Mx1-Cre-negative PtenFlox/Flox mice were treated with the same protocol (hereafter designated Pten+/+). Flow cytometric analyses of myeloid progenitor populations revealed that Pten−/− animals show a significant increase in the number of megakaryocyte-erythrocyte progenitors (MEPs) at the expense of CMPs and granulocyte-macrophage progenitors (GMPs; Figure 2A; supplemental Figure 2A). This is similar to the effect of ICN4 expression in a BM transplantation assay.13 Furthermore, BM cells from Pten−/− mice have a significantly increased megakaryocyte CFU (CFU-MK) potential compared with control animals (Figure 2B; supplemental Figure 2B). Finally, immunohistochemistry for the megakaryocyte-specific marker, VWF, showed significantly increased numbers of mature megakaryocytes in Pten-deficient animals than in control animals (Figure 2C-D). Of note, megakaryocyte ploidy and platelet counts were similar to controls, suggesting that terminal differentiation is unaffected (Figure 2E; supplemental Figure 2C). These data show the inhibitory role of Pten on early megakaryopoiesis in vivo and suggest that down-regulation of Pten may participate in the phenotypic effects of NOTCH signaling on megakaryocyte specification.

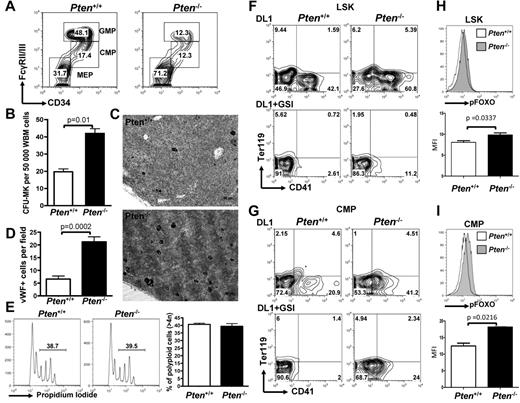

Pten deficiency enhances megakaryopoiesis in vivo and differentially affects NOTCH-induced megakaryopoiesis from LSK versus CMP cells. (A) Flow cytometric analysis of myeloid progenitors within the Lineage−cKit+Sca1− population of PtenFlox/Flox-Mx1Cre− (Pten+/+) or PtenFlox/Flox-Mx1Cre+ (Pten−/−) animals 2 weeks after pIpC. A representative of 5 independent animals is shown for each group. (B) Whole BM cells from Pten+/+ and Pten−/− mice were plated in MegaCult for assessment of CFU-MK potential. Mean ± SEM of quadruplicate experiments is represented. (C) Immunohistochemical analysis for the VWF highlights megakaryocytes (black). (D) Bar graphs are a representation of the analysis performed in panel C. The mean ± SEM number of megakaryocytes per microscope field in 25 independent fields is shown. (E) Megakaryocytes from Pten+/+ and Pten−/− mice were analyzed for ploidy content with the use of propidium iodide. Left and middle panels: a representative analysis is shown. Percentages of polyploid cells (> 4n) are indicated. Right panel: Bar graphs are representation of 4 independent analyses. (F) LSK cells from Pten+/+ and Pten−/− mice were flow-sorted 2 weeks after pIpC treatment and were cultured on OP9-DL1 stroma in the presence or absence of 1μM GSI. After 6 days of cocultures, cells were analyzed by flow cytometry for the development of CD41+ cells within the CD45+ gate. (G) CMP cells from Pten+/+ and Pten−/− mice were flow-sorted 2 weeks after pIpC treatment and analyzed as in panel F. (H) LSK cells from Pten+/+ and Pten−/− were cultured on OP9-DL1 stroma for 4 days and analyzed for phospho-FOXO by flow cytometry. Top panel: a representative analysis gated on CD45+ hematopoietic cells is shown. Bottom panel: bar graphs indicate the mean ± SEM of 2 independent experiments. (I) CMP cells from Pten+/+ and Pten−/− were analyzed as in panel H.

Pten deficiency enhances megakaryopoiesis in vivo and differentially affects NOTCH-induced megakaryopoiesis from LSK versus CMP cells. (A) Flow cytometric analysis of myeloid progenitors within the Lineage−cKit+Sca1− population of PtenFlox/Flox-Mx1Cre− (Pten+/+) or PtenFlox/Flox-Mx1Cre+ (Pten−/−) animals 2 weeks after pIpC. A representative of 5 independent animals is shown for each group. (B) Whole BM cells from Pten+/+ and Pten−/− mice were plated in MegaCult for assessment of CFU-MK potential. Mean ± SEM of quadruplicate experiments is represented. (C) Immunohistochemical analysis for the VWF highlights megakaryocytes (black). (D) Bar graphs are a representation of the analysis performed in panel C. The mean ± SEM number of megakaryocytes per microscope field in 25 independent fields is shown. (E) Megakaryocytes from Pten+/+ and Pten−/− mice were analyzed for ploidy content with the use of propidium iodide. Left and middle panels: a representative analysis is shown. Percentages of polyploid cells (> 4n) are indicated. Right panel: Bar graphs are representation of 4 independent analyses. (F) LSK cells from Pten+/+ and Pten−/− mice were flow-sorted 2 weeks after pIpC treatment and were cultured on OP9-DL1 stroma in the presence or absence of 1μM GSI. After 6 days of cocultures, cells were analyzed by flow cytometry for the development of CD41+ cells within the CD45+ gate. (G) CMP cells from Pten+/+ and Pten−/− mice were flow-sorted 2 weeks after pIpC treatment and analyzed as in panel F. (H) LSK cells from Pten+/+ and Pten−/− were cultured on OP9-DL1 stroma for 4 days and analyzed for phospho-FOXO by flow cytometry. Top panel: a representative analysis gated on CD45+ hematopoietic cells is shown. Bottom panel: bar graphs indicate the mean ± SEM of 2 independent experiments. (I) CMP cells from Pten+/+ and Pten−/− were analyzed as in panel H.

To further dissect the role of Pten inactivation downstream of NOTCH signaling at different stages of megakaryocyte lineage development from hematopoietic stem cells, we purified 2 well-characterized hematopoietic populations, LSK cells, enriched in HSCs, and CMPs, representing committed progenitors, from Pten−/− or Pten+/+ animals and plated them on OP9-DL1 stromal cells. Pten deficiency resulted in enhanced development of CD41+ cells on OP9-DL1 stroma from both LSK (Figure 2F) and CMP cells (Figure 2G). This observation indicates that PTEN antagonizes NOTCH signaling during normal megakaryocyte development from hematopoietic progenitors. Of note, the addition of GSI to the cocultures showed that Pten deficiency could not substitute for NOTCH pathway activation in LSK cells (Figure 2F). In contrast, there was only a modest effect on megakaryocyte development in this assay system when Pten−/− CMPs were plated in the presence of GSI (Figure 2G; supplemental Figure 2D). PTEN inhibits AKT activation and phosphorylation of downstream targets, including FOXO transcription factors, important negative regulators that are excluded from the nucleus on phosphorylation.42,43 We show that FOXOs are significantly more phosphorylated in Pten-deficient cells on NOTCH stimulation of LSK cells or CMPs, confirming that FOXOs are downstream of PTEN in this cellular context as well (Figure 2H-I). Together, these data show the role of PTEN as a negative regulator of megakaryocyte development in vitro and in vivo. They suggest that PTEN inactivation and AKT pathway activation are sufficient to induce megakaryocyte development from CMPs independently of NOTCH activation, whereas NOTCH signaling is required for LSK cell differentiation toward the megakaryocyte lineage.

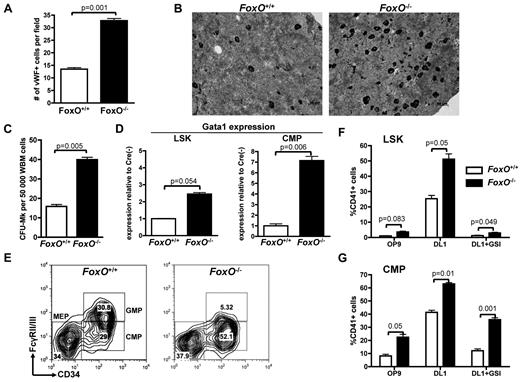

FOXO factors inhibit megakaryopoiesis in vivo and antagonize NOTCH-induced megakaryocyte development

FOXO family members were reported to interact with the NOTCH signaling pathway in muscle cells.44 FOXO1, FOXO3, and FOXO4 are expressed in the hematopoietic system and have redundant function.17,36 To test their involvement in megakaryocyte development, we used a triple FoxO1/3/4 conditional knockout model45,46 in which FoxO1/3/4Flox/Flox-Mx1-Cre or FoxO1/3/4Flox/Flox animals are injected with pIpC (respectively designated FoxO−/− and FoxO+/+) to inactivate all 3 FoxO genes. We first observed that BM sections derived from FoxO−/− had significantly more megakaryocytes than FoxO+/+ controls (Figure 3A-B). Furthermore, FoxO-deficient BM cells had a higher CFU-MK potential, in semisolid conditions colony assays than did their control counterparts (Figure 3C; supplemental Figure 3). Hematopoietic progenitors from FoxO−/− animals also showed an increased expression of the megakaryocytic transcription factor Gata1 (Figure 3D). Of note, FoxO−/− mice had a significant decrease in the GMP population, with a concomitant increase in the CMP population compared with control animals but no significant variation in the percentage of MEPs (Figure 3E).

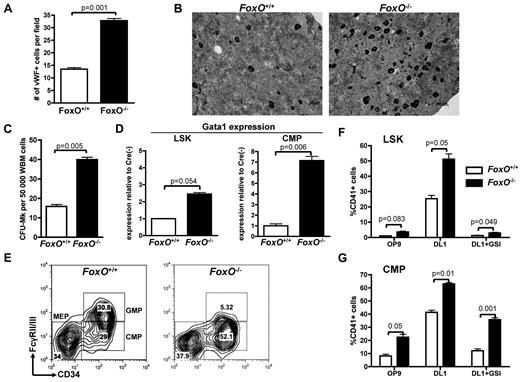

Absence of FOXO factors increases megakaryocytic potential of LSK cells and CMPs in vivo. (A) Immunohistochemical analysis of BM sections was performed against the VWF to highlight the megakaryocytes in FoxO1/3/4Flox/Flox-Mx1Cre− (FoxO+/+) versus FoxO1/3/4Flox/Flox-Mx1Cre+ (FoxO−/−) animals. Bar graphs represent the mean ± SEM number of megakaryocytes per microscope field in 25 independent fields. (B) Representative images of analysis performed in panel A. Megakaryocytes are in black. (C) Whole BM cells from FoxO+/+ or FoxO−/− animals were plated in MegaCult for assessment of CFU-MK potential. Mean ± SEM of quadruplicate experiments is represented. (D) Quantitative expression analysis of Gata-1 in flow-sorted LSK cells and CMPs from FoxO−/− or FoxO+/+ animals. All signals were normalized to Gapdh and are shown relative to FoxO+/+ RNA. Bar graphs represent the mean ± SEM of triplicate experiments. (E) Flow cytometric analysis of myeloid progenitors within the Lineage−cKit+Sca1− population of FoxO+/+ or FoxO−/− animals 3 weeks after pIpC. A representative analysis is shown. (F) LSK cells from FoxO+/+ or FoxO−/− mice were flow-sorted 3 weeks after pIpC treatment and cultured on OP9-GFP or OP9-DL1 stroma in the presence or absence of 1μM GSI. After 6 days of coculture, cells were analyzed by flow cytometry for the development of CD41+ cells within the CD45+ gate. Bar graphs indicate the mean ± SEM of 4 independent experiments. (G) CMP cells from FoxO+/+ or FoxO−/− mice were purified and analyzed as in panel F. Bar graphs indicate the mean ± SEM of 4 independent experiments.

Absence of FOXO factors increases megakaryocytic potential of LSK cells and CMPs in vivo. (A) Immunohistochemical analysis of BM sections was performed against the VWF to highlight the megakaryocytes in FoxO1/3/4Flox/Flox-Mx1Cre− (FoxO+/+) versus FoxO1/3/4Flox/Flox-Mx1Cre+ (FoxO−/−) animals. Bar graphs represent the mean ± SEM number of megakaryocytes per microscope field in 25 independent fields. (B) Representative images of analysis performed in panel A. Megakaryocytes are in black. (C) Whole BM cells from FoxO+/+ or FoxO−/− animals were plated in MegaCult for assessment of CFU-MK potential. Mean ± SEM of quadruplicate experiments is represented. (D) Quantitative expression analysis of Gata-1 in flow-sorted LSK cells and CMPs from FoxO−/− or FoxO+/+ animals. All signals were normalized to Gapdh and are shown relative to FoxO+/+ RNA. Bar graphs represent the mean ± SEM of triplicate experiments. (E) Flow cytometric analysis of myeloid progenitors within the Lineage−cKit+Sca1− population of FoxO+/+ or FoxO−/− animals 3 weeks after pIpC. A representative analysis is shown. (F) LSK cells from FoxO+/+ or FoxO−/− mice were flow-sorted 3 weeks after pIpC treatment and cultured on OP9-GFP or OP9-DL1 stroma in the presence or absence of 1μM GSI. After 6 days of coculture, cells were analyzed by flow cytometry for the development of CD41+ cells within the CD45+ gate. Bar graphs indicate the mean ± SEM of 4 independent experiments. (G) CMP cells from FoxO+/+ or FoxO−/− mice were purified and analyzed as in panel F. Bar graphs indicate the mean ± SEM of 4 independent experiments.

Plating of LSK and CMP cells from FoxO−/− or control FoxO+/+ animals on OP9-GFP versus OP9-DL1 stroma showed that FOXO inactivation gives rise to an increased number of megakaryocytes on NOTCH stimulation (Figure 3F-G; supplemental Figure 3). Deficiency in FoxO1/3/4 did not rescue megakaryocyte development of LSK cells cocultured with OP9-DL1 in the presence of GSI (Figure 3F). In contrast, there was efficient production of megakaryocytes from FoxO−/− CMPs in the absence of DL1 stimulation, both on OP9-GFP or on OP9-DL1 stroma treated with GSI (Figure 3G). Together, these results confirm that FOXOs are negative regulators of megakaryopoiesis in vivo47 and further show that they play an inhibitory role on NOTCH signaling.

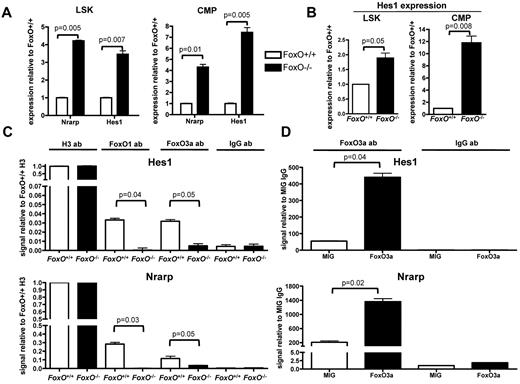

FOXO factors repress NOTCH targets

To better understand the molecular mechanism of interaction between FOXO and the NOTCH signaling pathway in hematopoietic cells, we assessed the expression levels of canonical NOTCH targets by quantitative RT-PCR analysis on RNA extracted from flow-sorted LSK cells and CMPs from FoxO−/− or FoxO+/+ animals. We observed that expression of both Nrarp and Hes1 was higher in FoxO−/− progenitors than in FoxO+/+ progenitors in vivo (Figure 4A). Hes1 expression was also up-regulated in FoxO−/− LSK cells or CMPs compared with FoxO+/+ cells on NOTCH activation in vitro (Figure 4B).

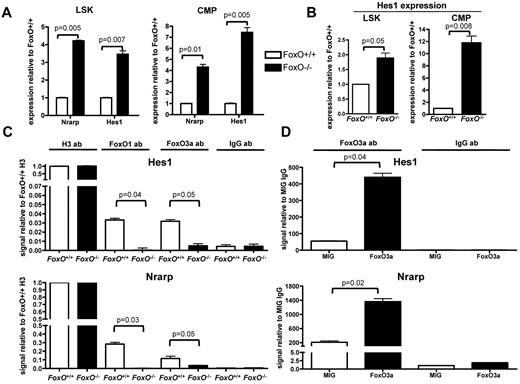

FOXO proteins bind to the Hes1 promoter region and antagonize NOTCH target genes transcription. (A) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of Nrarp and Hes1 in flow-sorted LSK cells and CMPs from FoxO−/− or FoxO+/+ animals. All signals were normalized to Gapdh and are shown relative to FoxO+/+ RNA. Bar graphs represent the mean ± SEM of triplicate experiments. (B) RNAs from flow-sorted FoxO−/− or FoxO+/+ LSK cells and CMPs were extracted after 3 days of coculture with OP9-DL1 stroma and analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR as in panel A. Bar graphs represent the mean ± SEM expression normalized to Gapdh and shown relative to FoxO+/+ cells grown on OP9-DL1 (n = 3). (C) ChIP of FoxO+/+ or FoxO−/− Lin− cells with the use of an anti-FOXO1 or an anti-FOXO3a Ab. Anti-Histone H3 and anti-IgG Abs were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. Bar graphs represent the mean ± SEM of triplicate experiments, and all Hes1 or Nrarp promoter region signals are normalized to FoxO+/+ sample pulled down with anti-Histone H3 Ab. (D) ChIP analysis of Lin− cells infected with an empty MIG vector or with a wild-type FoxO3a construct and pulled down with an anti-FOXO3a Ab. All signals are normalized to MIG cells pulled down with an anti-IgG Ab, and bar graphs represent the mean ± SEM of triplicate experiments.

FOXO proteins bind to the Hes1 promoter region and antagonize NOTCH target genes transcription. (A) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of Nrarp and Hes1 in flow-sorted LSK cells and CMPs from FoxO−/− or FoxO+/+ animals. All signals were normalized to Gapdh and are shown relative to FoxO+/+ RNA. Bar graphs represent the mean ± SEM of triplicate experiments. (B) RNAs from flow-sorted FoxO−/− or FoxO+/+ LSK cells and CMPs were extracted after 3 days of coculture with OP9-DL1 stroma and analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR as in panel A. Bar graphs represent the mean ± SEM expression normalized to Gapdh and shown relative to FoxO+/+ cells grown on OP9-DL1 (n = 3). (C) ChIP of FoxO+/+ or FoxO−/− Lin− cells with the use of an anti-FOXO1 or an anti-FOXO3a Ab. Anti-Histone H3 and anti-IgG Abs were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. Bar graphs represent the mean ± SEM of triplicate experiments, and all Hes1 or Nrarp promoter region signals are normalized to FoxO+/+ sample pulled down with anti-Histone H3 Ab. (D) ChIP analysis of Lin− cells infected with an empty MIG vector or with a wild-type FoxO3a construct and pulled down with an anti-FOXO3a Ab. All signals are normalized to MIG cells pulled down with an anti-IgG Ab, and bar graphs represent the mean ± SEM of triplicate experiments.

We then assessed whether FOXO factors directly bind the promoters of these genes. We sorted wild-type or FoxO−/− hematopoietic progenitors and performed ChIP assays with FOXO-specific Abs. We then used quantitative PCR to detect the Hes1 or Nrarp promoter region containing the RBPJ binding site. We observed that both FOXO1 and FOXO3 are present at these promoters in FoxO+/+ but not in FoxO−/− cells (Figure 4C). To confirm these findings, we performed similar ChIP analyses with extract from wild-type Lin− hematopoietic progenitors transduced with FoxO3 or control retrovirus. We observed that immunoprecipitation with the FOXO3a Ab enriched these promoters, specifically in FoxO3-transduced cells (Figure 4D). In contrast, neither FOXO1- nor FOXO3a-specific Abs immunoprecipitated the 3′-untranslated region of the Hes1 gene (supplemental Figure 3D-E), indicating that FOXOs specifically assemble at the promoters. Together, these results indicate that FOXOs antagonize NOTCH signaling during megakaryocyte development through direct inhibition of the transcription of canonical NOTCH targets. Because loss of FOXOs cannot substitute for NOTCH signaling in megakaryocyte development from LSK cells, these results also suggest that full transcriptional activation of NOTCH targets through combined inhibition of repressors (ie, FOXO) and recruitment of coactivators (ie, ICN/MAML complex) to RBPJ is required for megakaryocyte specification from LSK cells.

Differential dependence on the PI3K/AKT pathway for NOTCH-induced megakaryopoiesis from LSK cells versus CMPs

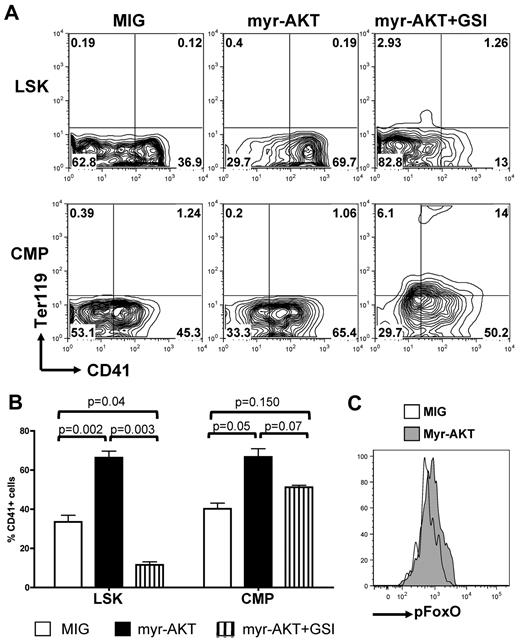

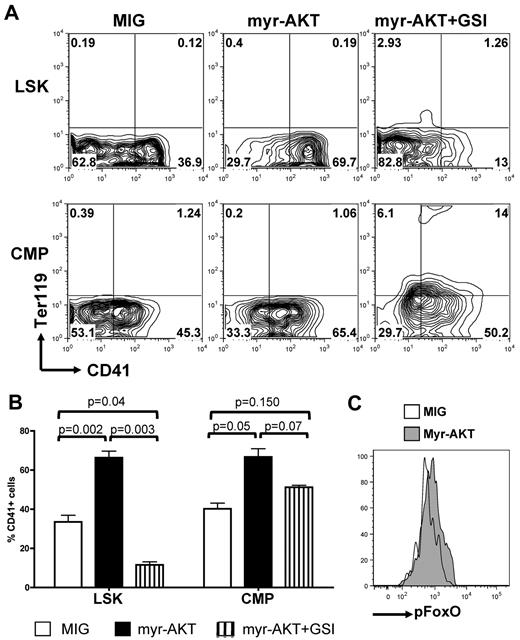

To confirm the role of AKT signaling in these observations and to ascertain that these results were not because of altered differentiation properties of Pten-deficient and FoxO1/3/4-deficient LSK and CMP cells, we acutely altered the PI3K/AKT pathway in wild-type LSK and CMP cells by expression of AKT mutants. We first assessed whether AKT activation could synergize or substitute for NOTCH signaling during megakaryocyte development. Transduction of LSK or CMP cells with a constitutively activated myristoylated AKT (myrAKT) mutant, followed by plating on OP9-DL1 stroma, showed that concomitant DL1 stimulation and myrAKT expression enhanced megakaryocyte development, compared with DL1 stimulation alone, from either LSK or CMP cells (Figure 5A-B). MyrAKT-expressing LSK cells did not efficiently give rise to CD41+ cells in the presence of GSI, whereas myrAKT-expressing CMPs showed partial rescue of the development of megakaryocytes in the presence of GSI and present increased phosphorylation of FOXOs compared with controls (Figure 5C).

Constitutive activation of AKT synergizes with NOTCH during in vitro megakaryopoiesis. (A) Sorted wild-type LSK cells and CMPs were transduced with retroviruses encoding either MIG or myr-AKT and subsequently plated on OP9-DL1 stroma in the presence or absence of GSI. Contour plots show a representative of 5 independent experiments. (B) Bar graphs represent mean ± SEM from 5 independent experiments described in panel A. (C) Wild-type CMPs were infected with an empty control (MIG) or myr-AKT vector, plated on OP9-DL1 stroma for 4 days, and analyzed for phospho-FOXO by flow cytometry. A representative analysis gated on CD45+ hematopoietic cells is shown.

Constitutive activation of AKT synergizes with NOTCH during in vitro megakaryopoiesis. (A) Sorted wild-type LSK cells and CMPs were transduced with retroviruses encoding either MIG or myr-AKT and subsequently plated on OP9-DL1 stroma in the presence or absence of GSI. Contour plots show a representative of 5 independent experiments. (B) Bar graphs represent mean ± SEM from 5 independent experiments described in panel A. (C) Wild-type CMPs were infected with an empty control (MIG) or myr-AKT vector, plated on OP9-DL1 stroma for 4 days, and analyzed for phospho-FOXO by flow cytometry. A representative analysis gated on CD45+ hematopoietic cells is shown.

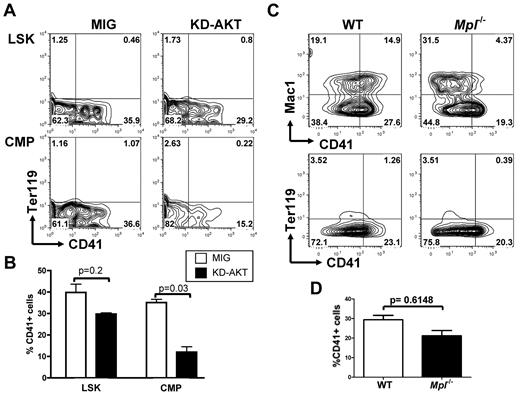

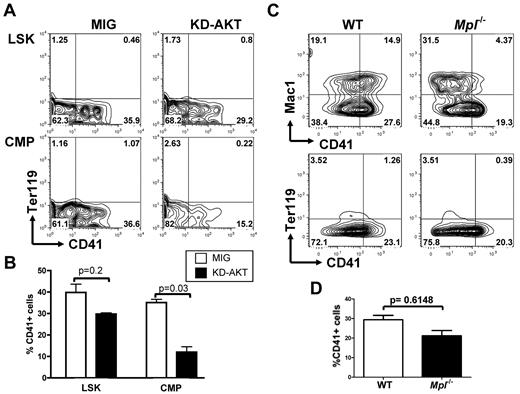

Reciprocally, we then tested whether AKT is an essential effector downstream of NOTCH by overexpressing a kinase-inactive AKT mutant (KD-AKT) that cannot activate signaling pathways downstream of AKT before plating LSK and CMP cells on OP9-DL1 stroma. Expression of this mutant resulted in a pronounced reduction in megakaryocyte development from CMPs but had only a modest effect on LSK differentiation (Figure 6A-B).

AKT activity is important for NOTCH-induced megakaryopoiesis from CMPs but not from LSK cells. (A) Flow cytometric analysis of purified wild-type LSK cells or CMPs infected with an empty control vector (MIG) or an inactive KD-AKT allele and plated on OP9-DL1 stroma for 6 days. Contour plots obtained from FACS analysis show a representative of 4 independent experiments. (B) Bar graphs represent mean ± SEM from 4 independent experiments described in panel A. (C) LSK cells from Mpl−/− and wild-type control animals were flow-sorted and cocultured with OP9-DL1 stroma for 6 days. A representative analysis, gated on CD45+ hematopoietic cells, is shown. (D) Bar graphs represent mean ± SEM from 2 independent experiments described in panel C.

AKT activity is important for NOTCH-induced megakaryopoiesis from CMPs but not from LSK cells. (A) Flow cytometric analysis of purified wild-type LSK cells or CMPs infected with an empty control vector (MIG) or an inactive KD-AKT allele and plated on OP9-DL1 stroma for 6 days. Contour plots obtained from FACS analysis show a representative of 4 independent experiments. (B) Bar graphs represent mean ± SEM from 4 independent experiments described in panel A. (C) LSK cells from Mpl−/− and wild-type control animals were flow-sorted and cocultured with OP9-DL1 stroma for 6 days. A representative analysis, gated on CD45+ hematopoietic cells, is shown. (D) Bar graphs represent mean ± SEM from 2 independent experiments described in panel C.

MPL is the master cytokine receptor regulating megakaryopoiesis both in vitro and in vivo and has been shown to activate the PI3K/AKT pathway during normal megakaryopoiesis. Mpl-deficient animals have a strong reduction in the number of megakaryocytes and platelets, but megakaryocytes can still be generated. On the basis of our results indicating that the PI3K/AKT pathway is not essential for NOTCH-induced megakaryopoiesis from LSK cells, we tested whether LSK cells from Mpl-deficient animals could engage megakaryocyte differentiation on NOTCH stimulation. We observed that purified LSK cells from Mpl−/− animals could readily develop into CD41+Mac1− cells on OP9-DL1 stroma (Figure 6C-D).

Together, these findings indicate that concomitant activation of the AKT and the NOTCH pathways enhances megakaryocyte development from both LSK and CMP cells. However, although PI3K/AKT activation can substitute for NOTCH stimulation in CMPs, NOTCH-induced megakaryopoiesis from LSK cells is largely independent of the status of the MPL/PI3K/AKT pathway in this model.

Discussion

In this study, we characterized a molecular circuitry responsible for the positive effect of NOTCH signaling on megakaryocytic fate specification. Combined analyses at the molecular, cellular, and organismal level show that the PI3K/AKT pathway is activated on NOTCH stimulation during megakaryocyte development and that further activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway enhances NOTCH-induced megakaryopoiesis. In addition, in vivo inactivation of PTEN and FOXOs, 2 negative regulators of the PI3K/AKT axis, shows their inhibitory roles during megakaryopoiesis. These data highlight a complex cross-regulation between the NOTCH and PI3K/AKT pathways. Finally, these results indicate that PI3K/AKT signaling is necessary and sufficient to induce megakaryocyte development from committed myeloid progenitors but not from LSK cells, supporting the existence of 2 independent pathways for megakaryocyte development. Together, we annotated the molecular basis of developmental decisions in the hematopoietic system which enables a decision to be made either at the hematopoietic stem cell or the committed progenitor level to commit to the megakaryocyte lineage.

Our results show that AKT lies at a nexus that integrates NOTCH and PI3K/AKT pathways during megakaryopoiesis. As reported in the context of acute lymphoblastic T-cell leukemia or mesothelioma cell survival, whereby the RBPJ target Hes1 negatively regulates transcription of PTEN,27,30 we observed that NOTCH activation during megakaryopoiesis results in down-regulation of Pten expression. In vivo inactivation of PTEN leads to an increased number of phenotypic MEPs and functional megakaryocyte progenitors, showing the important negative role of PTEN on normal megakaryocyte development. Of interest, PTEN inactivation phenocopies ICN4 expression in myeloid progenitors,13 suggesting that AKT pathway activation favors MEP over GMP cell fate and might be the main mediator of NOTCH-induced effect on CMPs. The effect of PTEN inactivation may result from the inhibition of pathways downstream of AKT, including FOXO factors, through phosphorylation by AKT leading to their nuclear exclusion.

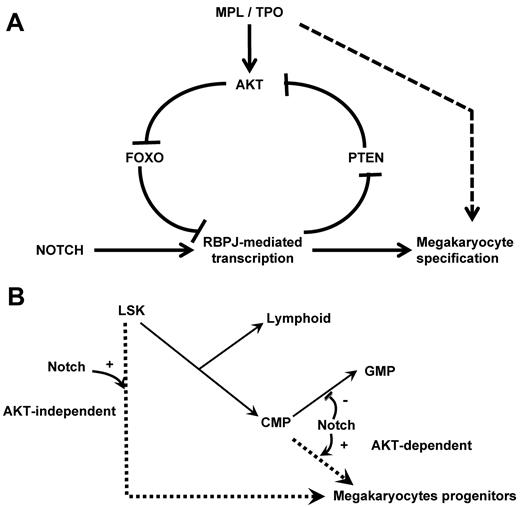

Reciprocally, we observe a regulation of NOTCH signaling by the PI3K/AKT pathway during megakaryopoiesis. Indeed, FOXOs are present at the promoter of the NOTCH targets Hes1 and Nrarp in primary hematopoietic progenitors. In addition, FoxO-deficient animals show an increased expression of RBPJ targets and an increased number of megakaryocytes in vivo. These results indicate that FOXOs repress transcription of RBPJ target genes and inhibit megakaryocyte development in vivo. Of note, the difference in RBPJ-mediated transcriptional regulation by FOXOs44 is consistent with the previously reported role of FOXOs as transcriptional activators or repressors and probably depends on the promoter and cell contexts.48 Together our data suggest the presence of a positive feedback loop during megakaryopoiesis, involving NOTCH-induced activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway, which in turn suppresses the inhibitory role of FOXO factors (Figure 7A). This feed-forward regulatory loop may thereby enable a threshold level of RBPJ-mediated transcription required for megakaryocyte specification from HSCs.

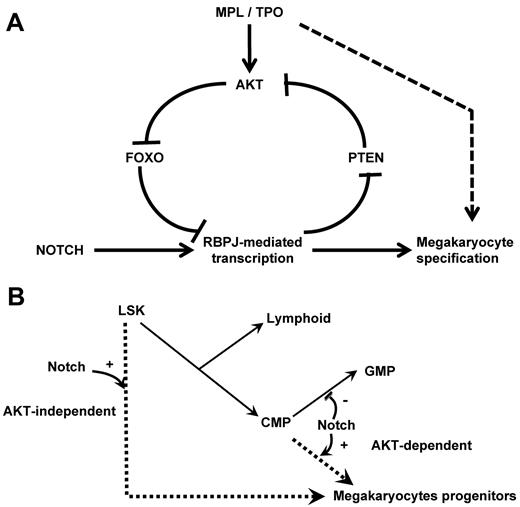

Schematic representation of the crosstalk between the NOTCH and AKT pathways at the molecular and cellular levels. (A) Scheme of the molecular pathways. NOTCH pathway activation inhibits PTEN expression leading to AKT activation, FOXO phosphorylation, and enhanced RBPJ-mediated transcription. We hypothesize that this regulatory loop links cytokine receptor signaling and RBPJ-mediated transcription. (B) Scheme of the megakaryocyte lineage development pathways. Our results support the hypothesis that megakaryocyte can develop from immature hematopoietic cells through a NOTCH-induced AKT-independent pathway. Megakaryocyte can also develop from committed myeloid progenitor through an AKT-dependent pathway that is activated by cytokine receptor activation (eg, MPL) and may also be stimulated by the NOTCH signaling.

Schematic representation of the crosstalk between the NOTCH and AKT pathways at the molecular and cellular levels. (A) Scheme of the molecular pathways. NOTCH pathway activation inhibits PTEN expression leading to AKT activation, FOXO phosphorylation, and enhanced RBPJ-mediated transcription. We hypothesize that this regulatory loop links cytokine receptor signaling and RBPJ-mediated transcription. (B) Scheme of the megakaryocyte lineage development pathways. Our results support the hypothesis that megakaryocyte can develop from immature hematopoietic cells through a NOTCH-induced AKT-independent pathway. Megakaryocyte can also develop from committed myeloid progenitor through an AKT-dependent pathway that is activated by cytokine receptor activation (eg, MPL) and may also be stimulated by the NOTCH signaling.

Interestingly, we observed that both Pten−/− and FoxO1/3/4−/− mice have an increased megakaryocyte potential and a reduced number of GMPs. Although Pten−/− mice have a concomitant increase in MEPs, FoxO1/3/4−/− mice show increased CMPs with no significant effect on MEPs. PTEN deficiency is predicted to result in the activation of all pathways activated by AKT, whereas FOXO deficiency affects only the FOXO branch of the AKT-activated pathways. Therefore, it might be anticipated that PTEN deficiency has an effect on NOTCH signaling and megakaryocyte development through activation of other AKT pathways. This hypothesis is supported by the recent observation that PI3K/AKT pathway blockage with the LY294002 inhibitor leads to a decrease of intracellular NOTCH (ICN) levels.44 In addition, we cannot exclude that compensatory mechanisms participate in these phenotypes. Indeed, it is important to note the absence of thrombocytosis in either Pten- or FoxO-deficient animals. This observation supports the idea of an uncoupling between megakaryocyte lineage commitment and megakaryocyte and platelet production observed in other models.49 It is also possible that in vivo homeostatic mechanisms, including reduced TPO serum levels, compensate for the increase in megakaryocyte and megakaryocyte progenitors in these animals. Here, we used knockout models in which efficient inactivation of Pten and FoxOs is observed in all hematopoietic progenitors to assess commitment of immature progenitors to the megakaryocyte lineage. Further investigation of this dichotomy may benefit from the use of lineage-specific inactivation models.

Our data also indicate a differential requirement of stem or committed progenitor cells for the AKT pathway downstream of NOTCH signaling during megakaryocyte development. We show that activation of the AKT pathway is essential for normal megakaryocyte differentiation of CMPs. Indeed, similar to what is observed at the β-selection checkpoint during T-cell differentiation,34 active AKT was sufficient to overcome the requirement for NOTCH signal during CMP differentiation. These observations indicate that megakaryocyte development from CMP primarily relies on AKT pathway activation, which may result either from stimulation of the TPO/MPL axis or indirectly from activation of the NOTCH pathway. In contrast, LSK cells can differentiate toward megakaryocytes in a NOTCH-dependent, AKT-independent manner, indicating that different molecular mechanisms can specify this lineage fate from an LSK cell or a committed progenitor. These results also support the hypothesis of 2 distinct megakaryocyte differentiation pathways: one pathway involving a CMP intermediate that depends strongly on PI3K/AKT signaling and another pathway that involves a more direct route from LSK cells to megakaryocytes that depends on NOTCH signaling without a necessary requirement for AKT signaling (Figure 7B). In vivo, it is also probable that LSK cells instructed to initiate megakaryocyte commitment by a NOTCH signal then become responsive to other proliferative signals, such as AKT signaling, to amplify megakaryopoiesis. In contrast, CMPs might only require AKT signaling, because they may have already been primed during prior developmental stages. This hypothesis is supported by our observation that TPO/MPL signaling interacts with the NOTCH pathway in this model. Indeed, we have already reported that MPL stimulation by TPO cooperates with NOTCH signaling during megakaryocyte development from CMPs but not from LSK cells.13 Accordingly, megakaryocytes can still develop in Mpl-deficient animals and from Mpl-deficient LSK cells on NOTCH stimulation in vitro, albeit at reduced levels. Together, these data warrant further assessment of the role of NOTCH signaling on Mpl-deficient megakaryocyte development in vivo.

In toto, this study proposes a complex molecular intertwining of the NOTCH and AKT pathways during megakaryocyte development and suggests that the combinatorial modulation of NOTCH and AKT may be useful to improve megakaryocyte development in vitro or in vivo or in the context of human megakaryocyte disorders. We have recently reported that coexpression of the one twenty-two–megakaryocytic acute leukemia fusion oncogene, which aberrantly activates RBPJ-mediated transcription, and a constitutively active MPL mutant results in leukemic transformation of the megakaryocytic lineage.12 In the context of the recent findings of PTEN mutations in T-ALL, it is therefore plausible that constitutive activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway plays a role in megakaryocyte malignancies.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Kira Gristman for the gift of the myr-AKT mutant, Dr Michael G. Kharas and Dr Dimitrios Kalaitzidis for providing reagents and helpful comments, Dr David A. Fruman for the generous gift of the KD-AKT mutant, Dr Jean-Luc Villeval for the generous gift of the Mpl−/− animals, and Dr Olivier Bernard for helpful support and discussions.

This work was supported in part by the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society (D.G.G.) and by Ligue National Contre le Cancer, Agence Nationale de la Recherche, and Fondation Gustave Roussy grants, a Leukemia & Lymphoma Society Special Fellowship, and an EHA-José Carreras Young Investigator fellowship (T.M.).

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: M.G.C. designed and performed research, analyzed data, and wrote a draft of the manuscript; S.M.S., C.L.C., and V.M. performed research, analyzed data, and revised the manuscript; T.K., C.K.L., P.R.-M., and P.R. performed research; Z.T. contributed vital reagents; J.C.A., R.A.D., and D.T.S. contributed vital reagents and revised the manuscript; D.G.G. designed and funded research, and revised the manuscript; and T.M. designed, funded, and performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: During the course of this work, one of the authors (D.G.G.) became a full-time employee of Merck and Co. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Thomas Mercher, Inserm U985, Institut Gustave Roussy, Pavillon de recherche 1, 39 rue Camille Desmoulins, 94800 Villejuif, France; e-mail: thomas.mercher@inserm.fr.

References

Author notes

MG.C., V.M., and S.M.S. contributed equally to this study.